- Department of Maternal and Child Health, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Objective: To examine the birth and health outcomes of children migrating with parents internationally and domestically, and to identify whether the healthy migration effect exist in migrant children.

Methods: Five electronic databases were searched for cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies published from January 1, 2000 to January 30, 2021and written by English language, reporting the risk of health outcomes of migrant children (e.g., birth outcome, nutrition, physical health, mental health, death, and substance use) We excluded studies in which participants' age more than 18 years, or participants were forced migration due to armed conflict or disasters, or when the comparators were not native-born residents. Pooled odd ratio (OR) was calculated using random-effects models.

Results: Our research identified 10,404 records, of which 98 studies were retrained for analysis. The majority of the included studies (89, 91%) focused on international migration and 9 (9%) on migration within country. Compared with native children, migrant children had increased risks of malnutrition [OR 1.26 (95% CI 1.11–1.44)], poor physical health [OR 1.34 (95% CI 1.11–1.61)], mental disorder [OR 1.24 (95% CI 1.00–1.52)], and death [OR 1.11 (95% CI 1.01–1.21)], while had a lower risk of adverse birth outcome [OR 0.92 (95% CI 0.87–0.97)]. The difference of substance use risk was not found between the two groups.

Conclusion: Migrant children had increased risk of adverse health outcomes. No obvious evidence was observed regarding healthy migration effect among migrant children. Actions are required to address the health inequity among these populations.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#myprospero, identifier: CRD42021214115.

Introduction

Migration is a global phenomenon with nearly one in seven individuals being a migrant (1). The majority are labor migrants who relocate to more developed areas, seeking employment opportunities, either internationally or domestically. Others are forced migrants because of wars, conflicts, or natural disasters. A growing number of children are compelled to migrate with their parents. According to the International Organization for Migration, the number of children migrating with their families beyond a country's border reached 37.9 million in 2019 (1). Similarly, the number of children migrating within a country (e.g., from rural to urban) is also spiking. In China, about 20.8% of the migrant population in 2010 were children younger than 14 years old (2).

Migrants are usually at a relatively lower socioeconomic ladder and have less access to public welfare, such as healthcare services and education (3). However, migrant adults present similar or better health outcomes compared to native populations in multiple health indices, including pregnancy outcomes, self-reported health, and adult mortality (4, 5). This phenomenon, known as the “migrant paradox” or “healthy migrant effect,” has been much debated (6). Evidence regarding the impacts of migration on migrant children's health status is inconsistent. Some migrant children experienced overall better health outcomes than the native-born children. In Portugal, children who migrated from other counties have a lower risk of being low birth weight (LBW) and small for gestational age (SGA) than native children (5). In contrast, the migratory process can generate unfavorable social and medical care conditions, placing the health of migrant children at risk. International migrant children in European and American countries have worse physical health (7), more mental health problems (8), and increased risks of fetal and infant mortality (9). These inconsistent observations may be related to population origins, migration types, and health indices used in the studies (10–12). Therefore, it is important to systematically examine the health status of migrant children and to understand the extent the health of these children is affected by migration and how the impacts may vary in regard to various health outcomes at birth and in later life.

No comprehensive assessment is available regarding the health status of migrant children across all the key areas of health. To address this study gap, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of migration on major health indicators, including children's birth outcome, nutrition, physical health, mental health, death, and substance use. We also examined whether the migration type (international or internal) differentially influences the health of these children. This is in response to the debate regarding the migrant paradox among children populations.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched five electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, and Scopus from January 1, 2000 to January 30, 2021. The full search strategy is provided in the Appendix. Based on literature review, we decided to investigate six categories of health outcomes: birth outcomes, nutrition, physical health, mental health, death, and substance use. We searched observational studies (e.g., cohort, case-control, or cross-section) reporting the risk of health outcomes that included migrant children aged 0–18 years. Both internal and international migrations were included. We defined international migrant children as those with at least one foreign-born parent, irrespective of the child's birth place, including first-generation and second-generation immigrants (13). Internal migrant children refer to children who have lived in the host city for more than 6 months while holding a non-local household residency, such as rural-to-urban migration (14). The comparator group consisted of native-born children (e.g., children and both parents without migration background) (15). We excluded the studies on refugee children who migrated due to armed conflict, disasters, or political, religious or ethnic persecution. Those with a comparator group of non-natives were also excluded. The initial literature search and screening to assess eligibility was done by two reviewers (HQ and Y). Any discrepancies about study inclusion were resolved through discussion with RX. Data were extracted by two reviewers (RX and CN) and checked by two others (HQ and Y). Studies that reported results as odds ratios (ORs) or included data that enable the calculation of ORs were retained for analysis. This study is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (16) (Appendix).

We summarized the health outcomes from all the included studies as follows. Birth outcomes included low birth weight (LBW), high birth weight (HBW), and preterm birth. Nutritional outcomes were overweight/obesity, underweight, and iron deficiency anemia. Physical health included oral, gastrointestinal, respiratory, allergic, and congenital diseases. Mental health covered depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autistic spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, suicide attempt. Deaths referred to fetal, perinatal, neonatal, post-neonatal, and infant deaths. Substance use included tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis (Appendix).

Data Analysis

The quality assessment for all included studies was done independently by two reviewers (RX and HQ) using an adapted version of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (Appendix). Studies with a high or unclear risk of bias across five or more domains were assessed as having high risk of bias. For each article ultimately included, we extracted data on the name of authors, publishing year, study country, study design, age of participants, sample size, and health outcomes using self-designed data extraction sheets. We also extracted ORs or recalculated pertinent ORs using available data.

We estimated pooled OR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the risk of health outcomes using a random-effects model. The I2 statistic was used to estimate the proportion of total variation among the pooled studies due to heterogeneity. We performed subgroup analyses of study region (e.g., Europe vs. non-Europe) to assess the source of heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were also conducted per migration type if possible, and the risk of each health outcome was assessed by host countries (the countries with at least two studies in each selected health outcome). We explored the potential risk of publication bias using Begg's and Egger's tests. We used forest plots to show the OR and 95% CIs for each study and the pooled estimates. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of our conclusions by excluding studies with quality score less than five. We used meta-regression to assess the effect of sample size (continuous), study design (cross-section vs. non- cross-section), publish year (<2010 vs. ≥2010), and participant's age (continuous) on health outcomes. All statistical analyses were done using Stata (version 12.0). The study was registered with PROSPERO (number: CRD42021214115).

Results

Characteristics of the Included Studies

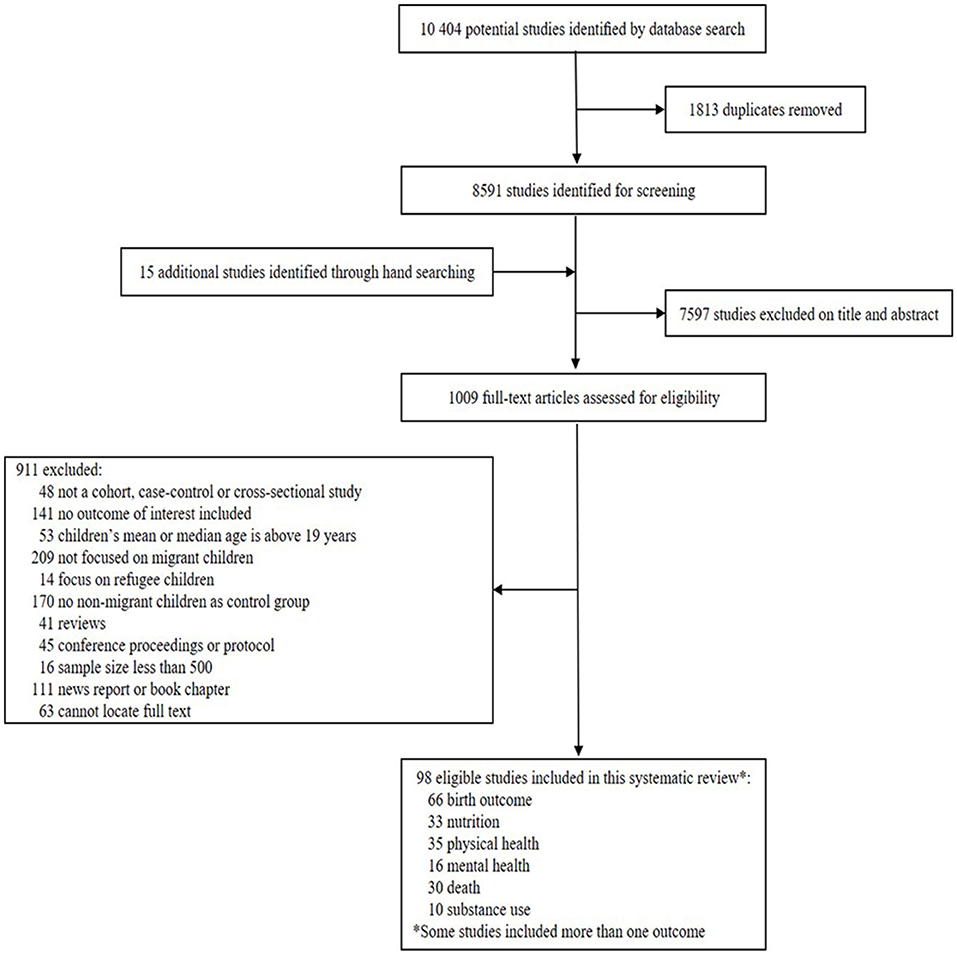

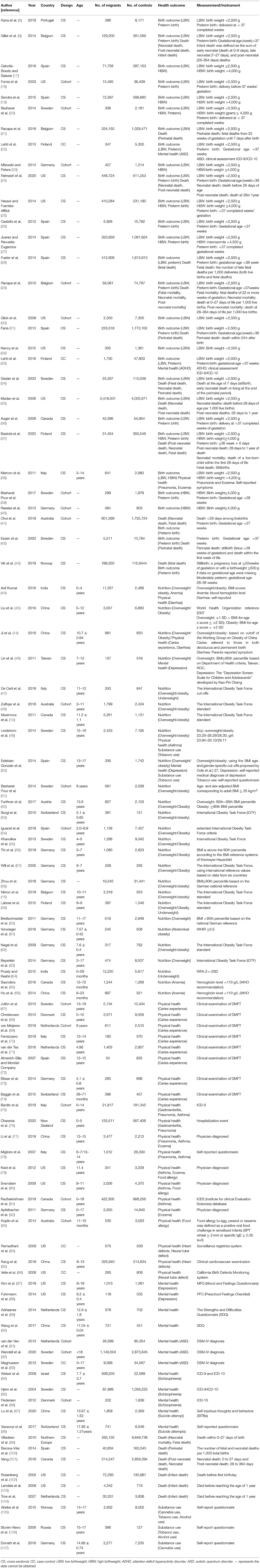

Among 10,404 references identified through the literature search, full-text copies of 1,009 articles were retrieved and screened, with 98 articles selected for analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram and study characteristics were shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Among the 98 included articles, 90.8% (89) involved international migration, 66.3% (65) studies were conducted in European countries, and 75.5% (74) were cross-sectional studies. Overall, 79.6% (78) of studies included children <10 years of age. The quality of the included studies varied, with 24.5% (24) studies bearing high or unclear risk of bias (Appendix). Birth outcomes were most commonly examined (n = 55), followed by physical health status (n = 34), nutrition status (n = 29), death (n = 28), mental health status (n = 16), and substance use (n = 8) (Appendix).

Birth Outcomes

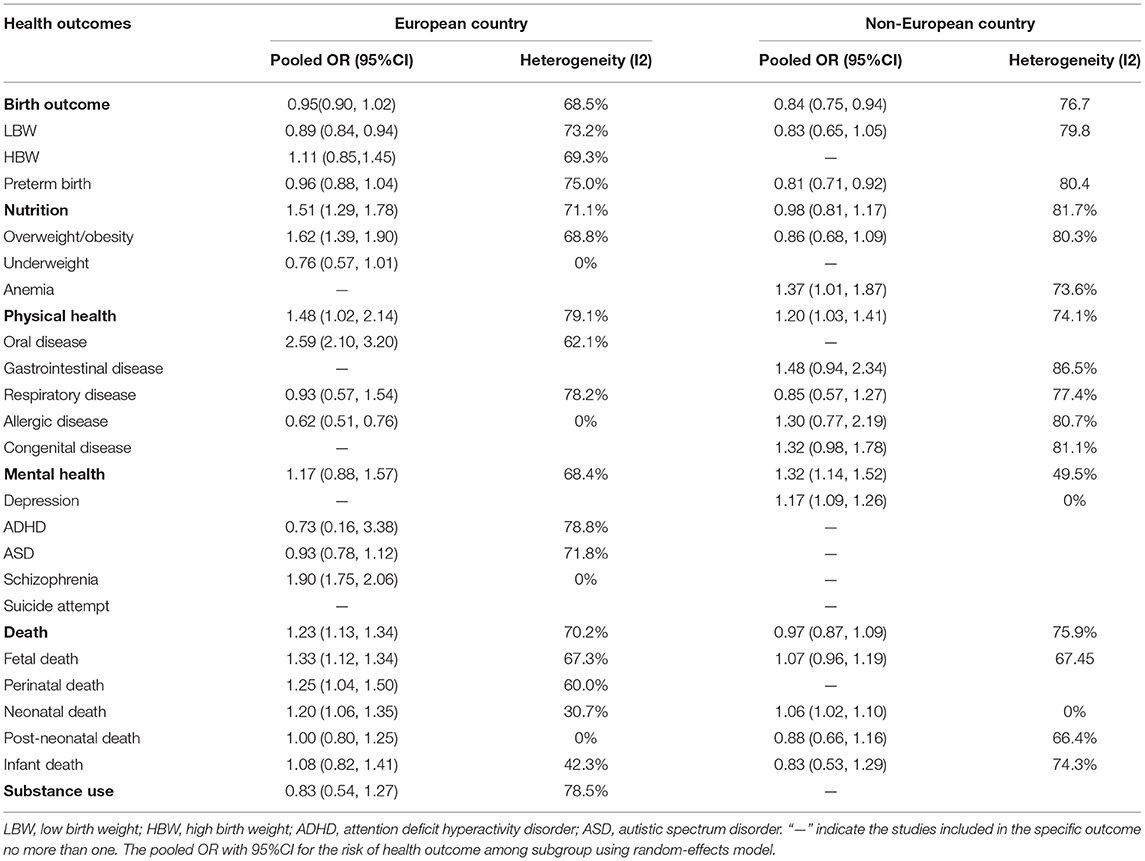

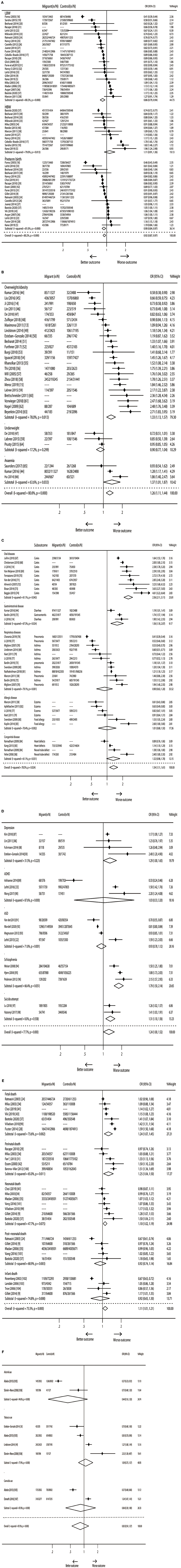

Migrant children had a lower risk of adverse birth outcome [OR 0.92 (95% CI 0.87–0.97)] than non-migrant children, including lower risk of LBW [OR 0.86 (95% CI 0.79–0.94)] and preterm birth [OR 0.90 (95% CI 0.84–0.97)] (Figure 2A). Although high statistical heterogeneity across birth outcomes was observed, it was reduced after subgroup and sensitivity analysis. In the subgroup analyses by region (Table 2), although no significant difference of overall adverse birth outcomes was found between migrant children and native ones in European countries [OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.90–1.02)], a lower risk of low birthweight was identified. In non-European countries, migrant children had a lower risk of overall adverse birth outcome [OR 0.84 (95% CI 0.75–0.94)] and preterm birth [OR 0.81 (95% CI 0.71–0.92)]. All the studies targeting birth outcomes were performed among international migrant children and the effect of domestic migration on birth outcomes cannot be unexplored. Sensitivity analysis of excluding studies with quality score less than five did not alter the above results (Appendix).

Figure 2. Forest plot of ORs for health outcomes. (A) Birth outcome. (B) Nutrition. (C) Physical health. (D) Mental health. (E) Death. (F) Substance use.

Nutrition

Migrant children had an increased risk of malnutrition [OR 1.26 (95% CI 1.11–1.44)], including higher risk of overweight/obesity [OR 1.33 (95% CI 1.13–1.57)] and iron-deficiency anemia [OR 1.37 (95% CI 1.01–1.87)]; while no difference was identified regarding underweight [OR 0.90 (95% CI 0.77–1.04)] between migrant and non-migrant children (Figure 2B). Heterogeneity between the estimates was low for underweight and high for overweight/obesity. Subgroup analyses by region (Table 2) revealed that migrant children in European countries had a significantly increased risk of malnutrition [OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.29–1.78)] such as overweight/obesity [OR 1.62 (95% CI 1.39–1.90)], while no significant differences were found between migrant children and native ones in the non-European countries. We also explored the effect of migration way on children's nutrition, which showed that international migrant children had an increased risk of overweight/obesity than non-migrant children [OR 1.47 (95% CI 1.28–1.68)], but the result was opposite for internal migrant children [OR 0.67 (95% CI 0.60–0.74)]. When the studies with quality score less than five were excluded, the risk of malnutrition was not altered (Appendix).

Physical Health

Migrant children had a significantly increased risk of poor physical health [OR 1.34 (95% CI 1.11–1.61)] compared with non-migrant children, including higher risk of oral disease [OR 2.56 (95% CI 2.11–3.11)] and gastrointestinal disease [OR 1.56 (95% CI 1.18–2.07)] (Figure 2C). Although high statistical heterogeneity was identified across the selected physical health outcomes, a reduction trend was found by using subgroup and sensitivity analysis. Subgroup analyses by region (Table 2) suggested that migrant children had poorer physical health than non-migrant children both in the European countries [OR 1.48 (95% CI 1.02–2.14)] and non-European countries [OR 1.20 (95% CI 1.03–1.41)]. The insufficient number of studies did not allow for analyses of the risk of physical health outcomes among internal migrant children. Sensitivity analyses by excluding studies of quality score less than five did not change the results related to physical health outcomes (Appendix).

Mental Health

Migrant children had a marginally higher risk of psychological problems [OR 1.24 (95% CI 1.00–1.52)] than the controls, including higher risk of depression [OR 1.29 (95% CI 1.00–1.65)], schizophrenia [OR 1.79 (95% CI 1.50–2.14)], and suicide attempt [OR 1.31 (95% CI 1.10–1.56)] (Figure 2D). Statistical heterogeneity across the mental health outcomes was moderate between estimates. Subgroup analyses by region (Table 2) showed that migrant children in European had an increased risk of schizophrenia; while in non-European countries had higher risk of depression. Given the limited number of studies on internal migrant children, we did not assess the effect of migration way on the risk of mental health outcomes. Sensitivity analyses by excluding studies with quality score less than five did not change the mental health outcomes (Appendix).

Deaths

All the studies on mortality focused on international migrant children. Migrant children were at a higher risk of death than the controls [OR 1.11 (95% CI 1.01–1.21)], including fetal death [OR 1.24 (95% CI 1.07–1.45)], perinatal death [OR 1.25 (95% CI 1.04–1.50)], and neonatal death [OR 1.10 (95% CI 1.02–1.19)] (Figure 2E). Statistical heterogeneity between estimates varied substantially across death outcomes, with the exception of neonatal death. Subgroup analyses by region (Table 2) on fetal death [OR 1.33 (95% CI 1.12–1.34)], perinatal death [OR 1.25 (95% CI 1.04–1.50)], and neonatal death [OR 1.20 (95% CI 1.06–1.35)] indicated a higher risk for migrant children in European countries than for non-migrant children, but not in the non-European countries, with the exception of neonatal death. The insufficient number of studies did not allow for analyses of the risk of death among internal migrant children. Sensitivity analyses did not change the above results (Appendix).

Substance Use

No significant differences were found in the risk of substance use [OR 0.83 (95% CI 0.54–1.27)], including alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use among migrant children compared with non-migrant children (Figure 2F). The above results did not change after sensitivity analyses (Appendix). Given the studies included in substance use were all conducted in the European countries, subgroup analyses by region did not performed. Also, the effect of migration type on substance use did not conducted due to the limited available studies.

The Begg's and Egger's tests indicated no significant publication bias among the included studies in six health outcomes (all P Begg′sTest >0.05 and P Egger′sTest >0.05).

Meta-regression analyses showed that the sample size, study design, publish year, and study region had effects on physical health outcome (β = 0.557, SE = 0.254, P = 0.043; β = 0.821, SE = 0.281, P = 0.010; β = 0.430, SE = 0.159, P = 0.015; β = 0.498, SE = 0.157, P = 0.006; respectively), while had no effects on birth outcome and physical health outcome (all P > 0.05). Additionally, the effect of study region on nutrition outcome (β = 0.597, SE = 0.209, P = 0.008) and publish year on mental health outcome (β = −0.557, SE = 0.228, P = 0.027) were also observed.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrated that migrant children tend to have overall worse health outcomes than non-migrant children. Compared with the controls, migrant children had an increased risk of malnutrition (e.g., overweight/obesity and anemia), poor physical health (oral diseases and gastrointestinal diseases), mental disorder (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, and suicide attempt), and death (fetal death, perinatal death, and neonatal death). The beneficial health effects were observed in birth outcomes such as lower risk of LBW and preterm birth.

The Healthy Migration Effect Does Not Necessarily Exist in Migrant Children Although Superior Birth Outcome Was Observed

“The immigrant paradox” has been reported in studies targeting the adult migration population. Despite the average lower socio-economic status of migrants and their inferior access to healthcare, adult migrants in advanced societies are generally healthier than the natives in the host country (17). The healthy immigrant effect was also reported in some health outcomes in children upon their birth or arrival. A review on international migrants in Spain suggested that children with migrant mothers have superior birth outcomes, such as a lower incidence of LBW and preterm birth than the natives (108), which is consistent with the finding of our meta-analysis. Specific factors such as mother's healthier migrant lifestyles and the cultural heritages of the migrant countries (e.g., lower rates of smoking and alcohol consumption) may partially explain the phenomenon (109). Another explanation is the selective migration hypothesis that healthier and/or wealthier women may choose to migrate to richer countries where they can have better birth outcomes (31). However, the notion that the health effect does not apply to all migrants is a subject of debate. Due to the limited generalizability, the immigrant paradox may be better conceptualized as outcome-specific with consideration of such relevant factors as immigrants' ethnicity, length of residence (10), nativity, and age at arrival (110). This meta-analysis suggests that the immigrant paradox does not necessarily exist among children in multiple outcomes. Migrant children have an overall poorer health status, especially in overweight/obesity, mental disorder, poorly physical health, and mortality.

Migrant Children Have Higher Risk of Developing Malnutrition, Especially Being Overweight/Obesity

As reported, migrant children adhered poorly to health diet recommendations for vegetable consumption and more likely to consume sweet and soft drinks than did the native residents, which is a driver factor for obesity (111). Our meta-analysis indicated an increased risk of overweight/obesity in migrant children, especially in those who migrated to European countries with high incomes, which were consistent with the concept that migration to developed countries may develop to be overweight and obesity (112). The increased risk of obesity among migrant children can be caused by alterations in dietary intake and adopting “unhealthier” practices of the host nations (113), including increased saturated fat and carbohydrate consumption. Eating disorder among migrants may be associated with stress during acculturation compounded by pressure to adapt to new cultural body shape norms (114). Additionally, children within lower income migrant families may easily exposed to more processed and energy-dense foods because they are cheaper and quicker to prepare (111). Moreover, alterations in physical activity, a more sedentary way of life, and lower sleep duration among migrant children (115), are also important drivers for overweight and obesity (116). Our study also suggested that international migrant children had a higher risk of overweight/obesity, but the opposite result was observed among children migrating within the country. As we known, international migrants from low-middle income countries to high income countries were more likely to adopt the above-mentioned westernized lifestyle and unhealthy dietary habits (e.g., high energy, sugar, and fat intake) which were the key risk of overweight/obesity. While the rural-to-urban migrant children in India and China usually live in lower socioeconomic families and may less likely to access to more other foods compared to urban children. Yet, the prevalence of overweight/obesity of rural-to-urban migrant children is increasing gradually in recent year, which need to be of concern.

Psychological Wellbeing Is Also One of Concerns in the Broader Population of Migrant Children

Our study found that migrant children have poorer mental health than their indigenous peers, including higher risk of depression, suicide attempt, and schizophrenia. In general, stress, anxiety and depression in migrant children are strongly influenced by psychological adaption within the host country (117). Acculturation stress which refers to the potential challenges migrants face when they negotiate differences between their home and host cultures (118) increases the risks of various mental health problems among immigrant adolescents, including withdrawn, somatic, and anxious/depressed symptoms (119). Such stress arises from multiple aspects of the acculturation process, including learning new and sometimes confusing cultural rules and expectations, dealing with prejudice and discrimination, and managing the overarching conflict between maintaining elements of the old culture while incorporating those of the new (120). By the way, the publication year of the included studies had effect on migrant children's mental health in our meta-regression analysis, this may be connected with the phenomenon that increasing number of researches focused on mental health were appeared in a decade year with the progress of globalization.

Poorly Experience of Health Is Not Uncommon Among Migrant Children

As reported that migrant children have high levels of ill health and unmet healthcare needs (121). In our study, migrant children have increased risk of mortality such as fetal death, perinatal death, and neonatal death, as well as worse physical health such as oral diseases and gastrointestinal diseases including diarrhea. The limited access to health service and insurance are the most challenging barriers for this situations (122). Experiences of health services are often unsatisfactory for migrant children, such as difficulties and delay in registering with the General medical Practitioners, difficulties securing medical appointments and missed follow-up appointments (121). Studies suggests that migrant children are four times as likely to be uninsured as native children (7). Moreover, access to health care may also be limited by their parents' knowledge and healthcare awareness, and language and cultural barriers (123–125). Additionally, the effects of poverty on access to health insurance and healthcare appear to be the strongest (7). Children from a migrant household are more likely to live in poverty than children from a non-migrant household. For US migrant families, children in poorer families were nearly twice as likely to have not visited a dentist and to lack a usual source of sick care, and 50% were more likely not to have visited a doctor in the previous year (7).

Actions Are Required to Address the Health Inequity Among These Populations

To date, monitoring migrant health is among the key priorities of the International Organization for Migration, and a set of actions have been taken to monitor migrants' health-seeking behaviors, access to and utilization of health services, and to increase the collection of data related to health status and outcomes of migrants (1). However, strategies specially designed to improve the birth and health status of migrant children remain insufficient. Through the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, countries worldwide have pledged to take actions to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 3 of good health and wellbeing and Goal 10 of reduced inequalities. Yet, the health inequalities are still prevalent. Poor health outcomes are secondary to system (e.g., long wait times between making appointments and seeing health professionals, and the long wait times at health facilities), financial, and language and cultural barriers (126). Addressing those barriers should be prioritized if the health status of migrants is to be improved. First, developing migrant-sensitive health systems and ensuring that health services are delivered to migrant children in a culturally and linguistically appropriate way, and enforce laws and regulations that prohibit discrimination. Second, adopting measures to improve the ability of health systems to deliver migrant inclusive services and programmes in a comprehensive, coordinated and financially sustainable way. Third, identifying good practices in monitoring migrant children's health and mapping policy models that facilitate equitable access to health care (1).

Strength and Limitations

The comprehensive scope of this meta-analysis is a strength since evidence across multiple health outcomes and with low publication bias. However, our study has several limitations. First, our original systematic search included literature published up to January 30, 2021, and thus newer studies may draw different conclusions. Second, statistical heterogeneity was moderate high in this meta-analysis, which did not significantly decrease after subgroup-analyses. Yet, meta-regression indicated that the sample size, study design, publish year, or study region had effects on multiple health outcomes, which may partly explain the source of high heterogeneity. Similarly, high heterogeneity was identified in a systematic review and meta-analyses of the health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children (127). Third, most of the included studies in our meta-analysis were from European countries, focused on international migration and were cross-sectional, which means temporal causal inference is limited and might not generalized. Fourth, the studies with forced migrant and unaccompanied children were excluded, which might have underestimated the health status of the migrant children. Fifth, we only included studies published in English language, the non-English studies with internal migrant children especially in Chinese publications might have been excluded. Last but not the least, we were unable to explore the effect of socioeconomic status, origin country, migrant generation (e.g., the first-generation and second-generation migration) and length of residence in the host country on the health outcomes of migrant children due to the unavailability of this information, which might contribute to the migration paradox.

Conclusion

Children migrating with parents have higher risk of poor health outcomes such as malnutrition, physical diseases, mental disorder, and death than the host populations. The healthy migrant paradox does not necessary exist among children in multiple outcomes. Interventions that support migrants are urgently needed to prevent long-term negative effects on their health and development.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

RC developed the study and oversaw its implementation, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. RC, CL, HQ, and YZ did review activities, consisting of searches, study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. JZ conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated, supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the study findings, read, and approved the final version before submission.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (HUST: 2020WKZDJC012) and by the Research and Publicity Department of China Association for Science and Technology (20200608CG111312).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.810150/full#supplementary-material

References

1. International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report. (2020). Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

2. Department of floating population service and management of national population and family planning commission of China. Current living situation of migrant population in China. Popul Res. (2010) 34:53–9.

3. Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Hatcher Roberts J, Torres S, DesMeules M. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ. (2011) 183:E952–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090287

4. Mehta NK, Elo IT. Migrant selection and the health of US immigrants from the former. Sov Union Demography. (2012) 49:425–47. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0099-7

5. Kana MA, Correia S, Barros H. Adverse pregnancy outcomes: a comparison of risk factors and prevalence in native and migrant mothers of portuguese generation XXI birth cohort. J Immigr Minor Health. (2019) 21:307–14. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0761-2

6. Bostean G. Does selective migration explain the Hispanic paradox? a comparative analysis of Mexicans in the US and Mexico. J Immigr Minor Health. (2013) 15:624–35. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9646-y

7. Huang ZJ, Yu SM, Ledsky R. Health status and health service access and use among children in US immigrant families. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:634–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049791

8. Belhadj Kouider E, Koglin U. Petermann F. Emotional and behavioral problems in migrant children and adolescents in Europe: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2014) 23:373–91. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0485-8

9. Gillet E, Saerens B, Martens G, Cammu H. Fetal and infant health outcomes among immigrant mothers in Flanders, Belgium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2014) 124:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.031

10. Urquia ML, O'Campo PJ. Heaman MI. Revisiting the immigrant paradox in reproductive health: the roles of duration of residence and ethnicity. Soc Sci Med. (2012) 74:1610–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.013

11. Simó C. Méndez S. Testing the effect of the epidemiologic paradox: birth weight of newborns of immigrant and non-immigrant mothers in the region of Valencia, Spain. J Biosoc Sci. (2014) 46:635–50. doi: 10.1017/S0021932013000539

12. Norredam M, Agyemang C, Hoejbjerg Hansen OK, Petersen JH, Byberg S, Krasnik A, et al. Duration of residence and disease occurrence among refugees and family reunited immigrants: test of the ‘healthy migrant effect' hypothesis. Trop Med Int Health. (2014) 19:958–67. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12340

13. Maximova K, O'Loughlin J. Gray-Donald K. Healthy weight advantage lost in one generation among immigrant elementary schoolchildren in multi-ethnic, disadvantaged, inner-city neighborhoods in Montreal, Canada. Ann Epidemiol. (2011) 21:238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.01.002

14. Ji Y, Wang Y, Sun L, Zhang Y, Chang C. The migrant paradox in children and the role of schools in reducing health disparities: a cross-sectional study of migrant and native children in Beijing, China. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0160025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160025

15. Méroc E, Moreau N, Lebacq T, Dujeu M, Pedroni C, Godin I, et al. Immigration and adolescent health: the case of a multicultural population. Public Health. (2019) 175:120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.001

16. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. (2015) 4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

17. Cebolla-Boado H, Salazar L. Differences in perinatal health between immigrant and native-origin children: evidence from differentials in birth weight in Spain. Demogr Res. (2016) 35:67–200. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.7

18. Forna F, Jamieson DJ, Sanders D, Lindsay MK. Pregnancy outcomes in foreign-born and US-born women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2003) 83:257–65. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00307-2

19. Restrepo-Mesa SL, Estrada-Restrepo A, González-Zapata LI, Agudelo-Suárez AA. Newborn birth weights and related factors of native and immigrant residents of Spain. J Immigr Minor Health. (2015) 17:339–48. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0089-5

20. Besharat Pour M, Bergström A, Bottai M, Magnusson J, Kull I, Wickman M. Body mass index development from birth to early adolescence; effect of perinatal characteristics and maternal migration background in a Swedish cohort. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e109519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109519

21. Racape J, Schoenborn C, Sow M, Alexander S. De Spiegelaere M. Are all immigrant mothers really at risk of low birth weight and perinatal mortality? The crucial role of socio-economic status. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:75. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0860-9

22. Lehti V, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, Cheslack-Postava K, Gissler M, Brown AS, Sourander A. The risk of childhood autism among second-generation migrants in Finland: a case-control study. BMC Pediatr. (2013) 13:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-171

23. Milewski N, Peters F. Too low or too high? on birthweight differentials of immigrants in Germany. Comp Popul Stud. (2014) 75: 289–303. doi: 10.12765/CPoS-2014-02

24. Ratnasiri AWG, Lakshminrusimha S, Dieckmann RA, Lee HC, Gould JB, Parry SS. Maternal and infant predictors of infant mortality in California, 2007-2015. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0236877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236877

25. Hessol NA, Fuentes-Afflick E. The impact of migration on pregnancy outcomes among Mexican-origin women. J Immigr Minor Health. (2014) 16:377–84. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9760-x

26. Castelló A, Río I, Martinez E, Rebagliato M, Barona C, Llácer A, et al. Differences in preterm and low birth weight deliveries between spanish and immigrant women: influence of the prenatal care received. Ann Epidemiol. (2012) 22:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.12.005

27. Juárez SP, Revuelta-Eugercios BA. Too heavy, too late: investigating perinatal health outcomes in immigrants residing in Spain. A cross-sectional study (2009-2011). J Epidemiol Community Health. (2014) 68:863–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202917

28. Fuster V, Zuluaga P, Román-Busto J. Stillbirth incidence in Spain: a comparison of native and recent immigrant mothers. Demogr Res. (2014). 12: 471–83. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.29

29. Racape J, De Spiegelaere M, Alexander S, Dramaix M, Buekens P, Haelterman E. High perinatal mortality rate among immigrants in Brussels. Eur J Public Health. (2010) 20:536–42. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq060

30. Glick JE, Bates L, Yabiku ST. Mother's age at arrival in the United States and early cognitive development. Early Child Res Q. (2009) 24:367–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.01.001

31. Farre L. New evidence on the healthy immigrant effect. Iza Discussion Papers. (2013) 29:365–94. doi: 10.1007/s00148-015-0578-4

32. Nancy S. Landale R, Oropesa S, Bridget K. Gorman migration and infant death: assimilation or selective migration among puerto ricans? Am Sociol Association. (2015) 65:888–909. doi: 10.2307/2657518

33. Lehti V, Chudal R, Suominen A, Gissler M, Sourander A. Association between immigrant background and ADHD: a nationwide population-based case-control study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2016) 57:967–75. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12570

34. Gissler M, Pakkanen M. Olausson PO. Fertility and perinatal health among Finnish immigrants in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. (2003) 57:1443–54. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00402-1

35. Madan A, Palaniappan L, Urizar G, Wang Y, Fortmann SP, Gould JB. Sociocultural factors that affect pregnancy outcomes in two dissimilar immigrant groups in the United States. J Pediatr. (2006) 148:341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.028

36. Auger N, Luo ZC, Platt RW, Daniel M. Do mother's education and foreign-born status interact to influence birth outcomes? Clarifying the epidemiological paradox and the healthy migrant effect. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2008) 62:402–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064535

37. Bastola K, Koponen P, Gissler M, Kinnunen TI. Differences in caesarean delivery and neonatal outcomes among women of migrant origin in Finland: a population-based study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. (2020) 34:12–20. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12611

38. Marcon A, Cazzoletti L, Rava M, Gisondi P, Pironi V, Ricci P, et al. Incidence of respiratory and allergic symptoms in Italian and immigrant children. Respir Med. (2011) 105:204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.009

39. Besharat Pour M, Bergström A, Bottai M, Magnusson J, Kull I, Moradi T. Age at adiposity rebound and body mass index trajectory from early childhood to adolescence; differences by breastfeeding and maternal immigration background. Pediatr Obes. (2017) 12:75–84. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12111

40. Reeske A, Spallek J, Bammann K, Eiben G, De Henauw S, Kourides Y, et al. Migrant background and weight gain in early infancy: results from the German study sample of the IDEFICS study. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e60648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060648

41. Choi SKY, Henry A, Hilder L, Gordon A, Jorm L, Chambers GM. Adverse perinatal outcomes in immigrants: a ten-year population-based observational study and assessment of growth charts. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. (2019) 33:421–32. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12583

42. Essén B, Hanson BS, Ostergren PO, Lindquist PG, Gudmundsson S. Increased perinatal mortality among sub-Saharan immigrants in a city-population in Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2000) 79:737–43. doi: 10.1080/00016340009169187

43. Vik ES, Aasheim V, Schytt E, Small R, Moster D, Nilsen RM. Stillbirth in relation to maternal country of birth and other migration related factors: a population-based study in Norway. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:5. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2140-3

44. Anil Kumar K. Effect of women's migration on urban children's health in India. Int J Migr Health Soc Care. (2016) 12:133–45. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-04-2014-0015

45. Liu W, Liu W, Lin R, Li B, Pallan M, Cheng KK, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of childhood obesity among primary school children in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:482. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3171-1

46. Lin FG, Tung HJ, Hsieh YH, Lin JD. Interactive influences of family and school ecologies on the depression status among children in marital immigrant families. Res Dev Disabil. (2011) 32:2027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.009

47. De Carli L, Spada E, Milani S, Ganzit GP, Ghizzoni L, Raia M, et al. Prevalence of obesity in Italian adolescents: does the use of different growth charts make the difference? World J Pediatr. (2018) 14:168–75. doi: 10.1007/s12519-018-0131-0

48. Zulfiqar T, Strazdins L, Banwell C, Dinh H, D'Este C. Growing up in Australia: paradox of overweight/obesity in children of immigrants from low-and-middle -income countries. Obes Sci Pract. (2018) 4:178–87. doi: 10.1002/osp4.160

49. Lindström M, Modén B, Rosvall M. Country of birth, parental background and self-rated health among adolescents: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health. (2014) 42:743–50. doi: 10.1177/1403494814545104

50. Esteban-Gonzalo L, Veiga OL, Gómez-Martínez S, Veses AM, Regidor E, Martínez D, et al. Length of residence and risk of eating disorders in immigrant adolescents living in madrid. Nutr Hosp. (2014) 29:1047–53.

51. Besharat Pour M, Bergström A. Bottai M. Effect of parental migration background on childhood nutrition, physical activity, and body mass index. J Obes. (2014) 2014:406529. doi: 10.1155/2014/406529

52. Furthner D, Ehrenmüller M, Biebl A, Lanzersdorfer R, Halmerbauer G, Auer-Hackenberg L, et al. Gender differences and the role of parental education, school types and migration on the body mass index of 2930 Austrian school children: a cross-sectional study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. (2017) 129:786–92. doi: 10.1007/s00508-017-1247-2

53. Bürgi F, Meyer U, Niederer I, Ebenegger V, Marques-Vidal P, Granacher U, et al. Socio-cultural determinants of adiposity and physical activity in preschool children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2010) 10:733. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-733

54. Iguacel I, Fernández-Alvira JM, Ahrens W, Bammann K, Gwozdz W, Lissner L, et al. Prospective associations between social vulnerabilities and children's weight status. Int J Obes. (2018) 42:1691–703. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0199-6

55. Khanolkar AR, Sovio U, Bartlett JW. Socioeconomic and early-life factors and risk of being overweight or obese in children of Swedish- and foreign-born parents. Pediatr Res. (2013) 74:356–63. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.108

56. Thi TGL, Heißenhuber A, Schneider T. The impact of migration background on the health outcomes of preschool children: linking a cross-sectional survey to the school entrance health examination database in Bavaria, Germany. Gesundheitswesen. (2019) 81:e34–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-119081

57. Will B, Zeeb H, Baune BT. Overweight and obesity at school entry among migrant and German children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2005) 5:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-45

58. Zhou Y, von Lengerke T, Walter U, Dreier M. Migration background and childhood overweight in the Hannover Region in 2010-2014: a population-based secondary data analysis of school entry examinations. Eur J Pediatr. (2018) 177:753–63. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3118-x

59. Labree W, van de Mheen D, Rutten F. Differences in overweight and obesity among children from migrant and native origin: the role of physical activity, dietary intake, and sleep duration. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0123672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123672

60. Brettschneider AK, Rosario AS, Ellert U. Validity and predictors of BMI derived from self-reported height and weight among 11- to 17-year-old German adolescents from the KiGGS study. BMC Res Notes. (2011) 4:414. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-414

61. Vorwieger E, Kelso A, Steinacker JM. Kesztyüs D. Cardio-metabolic and socio-environmental correlates of waist-to-height ratio in German primary schoolchildren: a cross-sectional exploration. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:280. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5174-6

62. Nagel G, Wabitsch M, Galm C, Berg S, Brandstetter S, Fritz M, et al. Determinants of obesity in the Ulm research on metabolism, exercise and lifestyle in children. Eur J Pediatr. (2009) 168:1259–67. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1016-y

63. Beyerlein A, Kusian D, Ziegler AG, Schaffrath-Rosario A, von Kries R. Classification tree analyses reveal limited potential for early targeted prevention against childhood overweight. Obesity. (2014) 22:512–7. doi: 10.1002/oby.20628

64. Prusty RK, Keshri K. Differentials in child nutrition and immunization among migrants and non-migrants in Urban India. Int J Migr Health Soc Care. (2015) 11:194–205. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-02-2014-0006

65. Saunders NR, Parkin PC, Birken CS. Iron status of young children from immigrant families. Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101:1130–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309398

66. Hu S, Tan H, Peng A, Jiang H, Wu J, Guo S, et al. Disparity of anemia prevalence and associated factors among rural to urban migrant and the local children under two years old: a population based cross-sectional study in Pinghu, China. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-601

67. Julihn A, Ekbom A, Modéer T. Migration background: a risk factor for caries development during adolescence. Eur J Oral Sci. (2010) 118:618–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00774.x

68. Christensen LB, Twetman S, Sundby A. Oral health in children and adolescents with different socio-cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Acta Odontol Scand. (2010) 68:34–42. doi: 10.3109/00016350903301712

69. van Meijeren-van Lunteren AW, Wolvius EB, Raat H. Ethnic background and children's oral health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. (2019) 28:1783–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02159-z

70. Ferrazzano GF, Cantile T, Sangianantoni G. Oral health status and Unmet Restorative Treatment Needs (UTN) in disadvantaged migrant and not migrant children in Italy. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2019) 20:10–4.

71. van der Tas JT, Kragt L, Veerkamp JJ, Jaddoe VW, Moll HA, Ongkosuwito EM, et al. Ethnic disparities in dental caries among six-year-old children in the Netherlands. Caries Res. (2016) 50:489–97. doi: 10.1159/000448663

72. Almerich-Silla JM, Montiel-Company JM. Influence of immigration and other factors on caries in 12- and 15-yr-old children. Eur J Oral Sci. (2007) 115:378–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00471.x

73. Bissar A, Schiller P, Wolff A, Niekusch U, Schulte AG. Factors contributing to severe early childhood caries in south-west Germany. Clin Oral Investig. (2014) 8:1411–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1116-y

74. Baggio S, Abarca M, Bodenmann P. Early childhood caries in Switzerland: a marker of social inequalities. BMC Oral Health. (2015) 15:82. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0066-y

75. Bardin A, Dalla Zuanna T, Favarato S, Simonato L, Zanier L, Comoretto RI et al. The role of maternal citizenship on pediatric avoidable hospitalization: a birth cohort study in North-East Italy. Indian J Pediatr. (2019) 86:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2826-6

76. Charania NA, Paynter J, Lee AC. Vaccine-preventable disease-associated hospitalisations among migrant and non-migrant children in New Zealand. J Immigr Minor Health. (2020) 22:223–31. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00888-4

77. Li L, Spengler JD, Cao SJ, Adamkiewicz G. Prevalence of asthma and allergic symptoms in Suzhou, China: trends by domestic migrant status. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. (2019) 29:531–8. doi: 10.1038/s41370-017-0007-8

78. Migliore E, Pearce N, Bugiani M, Galletti G, Biggeri A, Bisanti L, et al. Prevalence of respiratory symptoms in migrant children to Italy: the results of SIDRIA-2 study. Allergy. (2007) 62:293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01238.x

79. Keet CA, Wood RA, Matsui EC. Personal and parental nativity as risk factors for food sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2012) 129:169–75. e755. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.002

80. Svendsen ER, Gonzales M. Ross M. Variability in childhood allergy and asthma across ethnicity, language, and residency duration in El Paso, Texas: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. (2009) 8:55. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-55

81. Radhakrishnan D, Guttmann A, To T, Reisman JJ, Knight BD. Mojaverian N, et al. Generational patterns of asthma incidence among Immigrants to Canada over two decades a population-based cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2019) 16:248–57. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201803-187OC

82. Apfelbacher CJ, Diepgen TL. Schmitt J. Determinants of eczema: population-based cross-sectional study in Germany. Allergy. (2011) 66:206–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02464.x

83. Koplin JJ, Peters RL, Ponsonby AL, Gurrin LC, Hill D. Tang ML, et al. Increased risk of peanut allergy in infants of Asian-born parents compared to those of Australian-born parents. Allergy. (2014) 69:1639–47. doi: 10.1111/all.12487

84. Ramadhani T, Short V, Canfield MA. Are birth defects among Hispanics related to maternal nativity or number of years lived in the United States? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. (2009) 85:755–63. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20584

85. Kang G, Xiao J, Wang J, Chen J, Li W, Wang Y, et al. Congenital heart disease in local and migrant elementary schoolchildren in Dongguan, China. Am J Cardiol. (2016) 117:461–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.061

86. Velie EM, Shaw GM, Malcoe LH, Schaffer DM, Samuels SJ, Todoroff K et al. Understanding the increased risk of neural tube defect-affected pregnancies among Mexico-born women in California: immigration and anthropometric factors. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. (2006) 20:219–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00722.x

87. Kim J, Nicodimos S, Kushner SE, Rhew IC, McCauley E, Vander Stoep A. Comparing mental health of US children of immigrants and non-immigrants in 4 racial/ethnic groups. J Sch Health. (2018) 88:167–75. doi: 10.1111/josh.12586

88. Fuhrmann P, Equit M, Schmidt K, von Gontard A. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated developmental disorders in preschool children: a population-based study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2014) 23:219–24. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0452-4

89. Adriaanse M, Veling W, Doreleijers T, van Domburgh L. The link between ethnicity, social disadvantage and mental health problems in a school-based multiethnic sample of children in The Netherlands. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2014) 23:1103–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0564-5

90. Wang J, Liu K, Zheng J. Prevalence of mental health problems and associated risk factors among rural-to-urban migrant children in Guangzhou, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:1385. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111385

91. van der Ven E, Termorshuizen F, Laan W, Breetvelt EJ, van Os J, Selten JP. An incidence study of diagnosed autism-spectrum disorders among immigrants to the Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2013) 128:54–60. doi: 10.1111/acps.12054

92. Wändell P, Fredrikson S. Carlsson AC. Epilepsy in second-generation immigrants: a cohort study of all children up to 18 years of age in Sweden. Eur J Neurol. (2020) 27:152–9. doi: 10.1111/ene.14049

93. Magnusson C, Rai D, Goodman A. Migration and autism spectrum disorder: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. (2012) 201:109–15. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095125

94. Weiser M, Werbeloff N, Vishna T, Yoffe R, Lubin G, Shmushkevitch M, Davidson M. Elaboration on immigration and risk for schizophrenia. Psychol Med. (2008) 38:1113–9. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700205X

95. Hjern A, Wicks S, Dalman C. Social adversity contributes to high morbidity in psychoses in immigrants–a national cohort study in two generations of Swedish residents. Psychol Med. (2004) 34:1025–33. doi: 10.1017/S003329170300148X

96. Pedersen CB, Demontis D, Pedersen MS, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Børglum AD, et al. Risk of schizophrenia in relation to parental origin and genome-wide divergence. Psychol Med. (2012) 42:1515–21. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002376

97. Lu J, Wang F, Chai P, Wang D, Li L, Zhou X. Mental health status, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors of migrant children in eastern coastal China in comparison to urban children: a cross-sectional survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2020) 14:4. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-0311-2

98. Vazsonyi AT, Mikuška J, Gaššová Z. Revisiting the immigrant paradox: suicidal ideations and suicide attempts among immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents. J Adolesc. (2017) 59:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.05.008

99. Villadsen SF, Sievers E, Andersen AM, Arntzen A, Audard-Mariller M. Martens G, et al. Cross-country variation in stillbirth and neonatal mortality in offspring of Turkish migrants in Northern Europe. Eur J Public Health. (2010) 20:530–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq004

100. Barona-Vilar C, López-Maside A, Bosch-Sánchez S. Inequalities in perinatal mortality rates among immigrant and native population in Spain, 2005-2008. J Immigr Minor Health. (2014) 16:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9730-3

101. Vang ZM. Infant mortality among the Canadian-born offspring of immigrants and non-immigrants in Canada: a population-based study. Popul Health Metr. (2016), 14:32. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0101-5

102. Rosenberg KD, Desai RA, Kan J. Why do foreign-born blacks have lower infant mortality than native-born blacks? new directions in African-American infant mortality research. J Natl Med Assoc. (2002) 94:770–8.

103. Landale NS, Gorman BK. Oropesa RS. Selective migration and infant mortality among Puerto Ricans. Matern Child Health J. (2006) 10:351–60. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0072-4

104. Troe EJ, Kunst AE, Bos V, Deerenberg IM, Joung IM, Mackenbach JP. The effect of age at immigration and generational status of the mother on infant mortality in ethnic minority populations in The Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. (2007) 17:134–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl108

105. Abebe DS, Hafstad GS, Brunborg GS, Kumar BN, Lien L. Binge Drinking, Cannabis and tobacco use among ethnic norwegian and ethnic minority adolescents in Oslo, Norway. J Immigr Minor Health. (2015) 17:992–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0077-9

106. Slonim-Nevo V, Sharaga Y, Mirsky J, Petrovsky V, Borodenko M. Ethnicity versus migration: two hypotheses about the psychosocial adjustment of immigrant adolescents. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2006) 52:41–53. doi: 10.1177/0020764006061247

107. Donath C, Baier D, Graessel E, Hillemacher T. Substance consumption in adolescents with and without an immigration background: a representative study-What part of an immigration background is protective against binge drinking? BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:1157. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3796-0

108. Juárez SP, Ortiz-Barreda G, Agudelo-Suárez AA. Ronda-Pérez E. Revisiting the healthy migrant paradox in perinatal health outcomes through a scoping review in a recent host country. J Immigr Minor Health. (2017) 19:205–14. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0317-7

109. Flores ME, Simonsen SE, Manuck TA, Dyer JM, Turok DK. The “Latina epidemiologic paradox”: contrasting patterns of adverse birth outcomes in U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinas. Womens Health Issues. (2012) 22: e501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.07.005

110. Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Clark TT, Terzis LD. Córdova D. Substance use disorders among first- and second-generation immigrant adults in the United States: evidence of an immigrant paradox? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2014) 75:958–67. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.958

111. Esteban-Gonzalo L, Veiga OL, Gómez-Martínez S, Regidor E, Martínez D, Marcos A, et al. Adherence to dietary recommendations among Spanish and immigrant adolescents living in Spain; the AFINOS study. Nutricion Hospitalaria. (2013) 28:1926–36.

112. Renzaho AM, Mellor D, Boulton K, Swinburn B. Effectiveness of prevention programmes for obesity and chronic diseases among immigrants to developed countries - a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. (2010) 13:438–50. doi: 10.1017/S136898000999111X

113. Méjean C, Traissac P, Eymard-Duvernay S, Delpeuch F, Maire B. Influence of acculturation among Tunisian migrants in France and their past/present exposure to the home country on diet and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. (2009) 12:832–41. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003285

114. Esteban-Gonzalo L, Veiga ÓL, Regidor E, Martínez D, Marcos A, Calle ME, et al. Immigrant status, acculturation and risk of overweight and obesity in adolescents living in Madrid (Spain): the AFINOS study. J Immigr Minor Health. (2015) 17:367–74. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9933-2

115. Toselli S, Zaccagni L, Celenza F, Albertini A, Gualdi-Russo E. Risk factors of overweight and obesity among preschool children with different ethnic background. Endocrine. (2014) 49:717–25. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0479-4

116. Knutson KL. Does inadequate sleep play a role in vulnerability to obesity? Am J Hum Biol. (2012) 24:361–71. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22219

117. Stevens GW, Walsh SD, Huijts T, Maes M, Madsen KR, Cavallo F, Molcho M. An internationally comparative study of immigration and adolescent emotional and behavioral problems: effects of generation and gender. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 57:587–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.001

118. Sam DL, Vedder P, Ward C, Horenczyk G. Immigrant youth in cultural transition: acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Zeitschrift Fur Padagogik. (2006) 55:303–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x

119. Sirin SR, Ryce P, Gupta T, Rogers-Sirin L. The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol. (2013) 49:736–48. doi: 10.1037/a0028398

120. Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl Psychol. (2010) 46:5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

121. Lorek A, Ehntholt K, Nesbitt A, Wey E, Githinji C, Rossor E, et al. The mental and physical health difficulties of children held within a British immigration detention center: a pilot study. Child Abuse Negl. (2009) 33:573–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.005

122. Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Singh GK. Health status and health services utilization among US Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, and other Asian/Pacific Islander children. Pediatrics. (2004) 113:101–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.101

123. Yu SM, Nyman RM, Kogan MD, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH. Parent's language of interview and access to care for children with special health care needs. Ambul Pediatr. (2004) 4:181–7. doi: 10.1367/A03-094R.1

124. Pourat N, Lessard G, Lulejian A. Demographics, Health, Access to Care of Immigrant Children in California: Identifying Barriers to Staying Healthy. Los Angeles, CA: Center for Health Policy Research (2003). Available online at: http://www.healthpolicy.ucla.edu/pubs/files/NILC_FS_032003.pdf

125. Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH, Kogan MD. Parental awareness of health and community resources among immigrant families. Matern Child Health J. (2005) 9:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-2547-0

126. Salami B, Mason A, Salma J, Yohani S, Amin M, Okeke-Ihejirika P, et al. Access to healthcare for immigrant children in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3320. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093320

Keywords: migrant children, health outcomes, meta-analysis, healthy migration effect, birth outcomes

Citation: Chang R, Li C, Qi H, Zhang Y and Zhang J (2022) Birth and Health Outcomes of Children Migrating With Parents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 10:810150. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.810150

Received: 06 November 2021; Accepted: 23 May 2022;

Published: 13 July 2022.

Edited by:

Cecilia Lai Wan Chan, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Lorena Elena Melit, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureş, RomaniaYingpu Sun, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China

Margaret Xi Can YIIN, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2022 Chang, Li, Qi, Zhang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianduan Zhang, amRfemhAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Ruixia Chang

Ruixia Chang Chunan Li

Chunan Li Jianduan Zhang

Jianduan Zhang