94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pediatr., 21 March 2022

Sec. Pediatric Neurology

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.782104

Background: With current medical advancements, more adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders are transitioning from child- to adult-centred health care services. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for transitional services to help navigate this transition. Health care transitions can be further complicated by mental health challenges prevalent among individuals with cerebral palsy (CP), spina bifida (SB), and childhood onset acquired brain injury (ABI). Offering evidence-based psychological interventions for these populations may improve overall outcomes during transition period(s) and beyond. The objective of this scoping review is to identify key characteristics of psychological interventions being used to treat the mental health challenges of adolescents and adults with CP, SB, and childhood onset ABI.

Methods: Methodological frameworks by Arksey and O'Malley, and Levac and colleagues were used to explore studies published between 2009 and 2019. Included studies were required to be written in English and report on a psychological intervention(s) administered to individuals at least 12 years of age with a diagnosis of CP, SB, or childhood onset ABI. All study designs were included.

Results: A total of 11 studies were identified. Of these, eight reported psychological interventions for childhood onset ABI, while three reported on CP. No studies reporting on SB were identified. Commonly used interventions included acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), psychotherapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Conclusions: There are a limited number of studies investigating psychological interventions for individuals with childhood onset ABI and CP, and none for individuals with SB. Further research into effective psychological interventions for these populations will improve mental health outcomes and transitional services.

Neurodevelopmental disorders, including cerebral palsy (CP), spina bifida (SB), and childhood onset acquired brain injury (ABI) are complex medical conditions that may impact multiple aspects of a child's life, including his/her physical and psychological wellbeing (1, 2). Individuals with these conditions often require life-long health care management to reach occupational goals and their fullest potential (3, 4). In the past, children with neurodevelopmental disorders were often not expected to survive into adulthood; however, with current medical advancements, more than 75% will live to adulthood (2, 3, 5). This increase in longevity has subsequently led to an increase in the number of children transitioning from child- to adult-centered health care (6).

The transition from child- to adult-centered health care services is a complex and difficult process (7–9). Numerous studies have reported many transitional services are not coordinated to meet both physical and psychosocial needs (5, 10–13). Indeed, the transition process can further be complicated by psychological difficulties individuals with CP, SB, and childhood onset ABI may experience. Mental health difficulties such as anxiety, depression, and lower self-esteem have been found to be more common among young adults with neurodevelopmental disorders (10, 14, 15). For example, individuals with CP are more likely to experience poorer mental health compared to those without CP (16, 17). It has also been reported that 41–48% of young adults (14–21) with a diagnosis of SB experience depression compared to 10.9% of their typically developing peers (18). Furthermore, individuals with mild to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) are at a significantly higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or depression, compared to their same aged peers (19). Adults with childhood onset conditions are also more likely to experience a lack of community involvement, decreased social skills, peer rejection, and social stigma in comparison to others (2, 20, 21). These psychosocial difficulties can further complicate one's experience of navigating the health care system and managing chronic health conditions.

Psychological interventions may be one option to address these significant concerns (22, 23). Commonly used effective psychological interventions for the general population include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (24, 25), psychotherapy (25), and mindfulness or other relaxation techniques (26, 27). Although many studies have been published investigating the effectiveness of psychological interventions for the general population, literature summarizing psychological interventions and its effectiveness for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders is lacking (22, 23) (i.e., lack of recognition of the “emotional life” of adults with neurodevelopmental disorders), despite the population's increasing psychological difficulties.

Further exploration of the various psychological interventions for individuals with CP, SB, and childhood onset ABI is essential to improve transitional health care services. By examining the extent of published literature on psychological interventions, gaps within this area of research will be identified and provide insight into potential treatments for mental illnesses these populations experience (22, 23). Thus, the purpose of this scoping review is to (1) determine what psychological interventions have been reported in the literature/evaluated to treat mental health difficulties experienced by individuals with CP, SB, and childhood onset ABI; and (2) identify the key characteristics of these interventions for these populations and their effectiveness.

The current scoping review used the methodological frameworks proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (28) and Levac et al. (29) The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (30) was used to inform the processes and reporting of this review.

To be eligible for inclusion, studies must have investigated the implementation of psychological interventions with individuals with CP, SB, and childhood onset ABI. Psychological interventions were defined as treatments focused on reducing psychological distress through counseling, support, interaction or instruction, with an aim to increase adaptive behavior (31). Examples of psychological interventions include CBT, mindfulness-based stress reduction, or psychotherapy. These interventions can be delivered face-to-face or online (e.g., video conferencing, social media), and be delivered one-on-one or in a group setting by any health care provider or health care provider trainee (i.e., we excluded those interventions that were delivered by a peer mentor). To ensure literature was relevant to the current health care system, only studies published within the last 10 years (e.g., from January 2009 to July 2019) were included. All study designs were included. Furthermore, only studies published in English were included.

The literature search strategy was developed by the research team in collaboration with a Librarian (LP) with expertise in systematic and scoping review methods. The search included medical subject headings and text words related to adults with childhood onset disabilities (e.g., CP, SB, or ABI), and psychological interventions (e.g., CBT or mindfulness). Relevant literature was collected from: MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, and PsycINFO, to ensure literature was collected from a diverse range of disciplines. Appropriate wildcards were used to account for plurals and variations in spelling. The search strategy for MEDLINE can be found in an additional file (see Supplementary File 1). Reference lists from reviews were hand-searched to ensure literature saturation.

All study screening and selection occurred in Covidence (covidence.org), an online literature review tool. Titles and abstracts of studies identified were screened (i.e., level one screening). Full-text screening of potentially relevant articles (i.e., level two screening) was completed to determine final article inclusion. Both level one and level two screening were done independently by two reviewers (MJ and TP). Conflicts between reviewers were resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

Data abstracted included authors, year of publication, country of study, recruitment setting, mean age/age range, sample size, type of condition, key intervention characteristics, and the associated outcomes and their impact. Intervention characteristics reported were based on the Template of Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework (32).

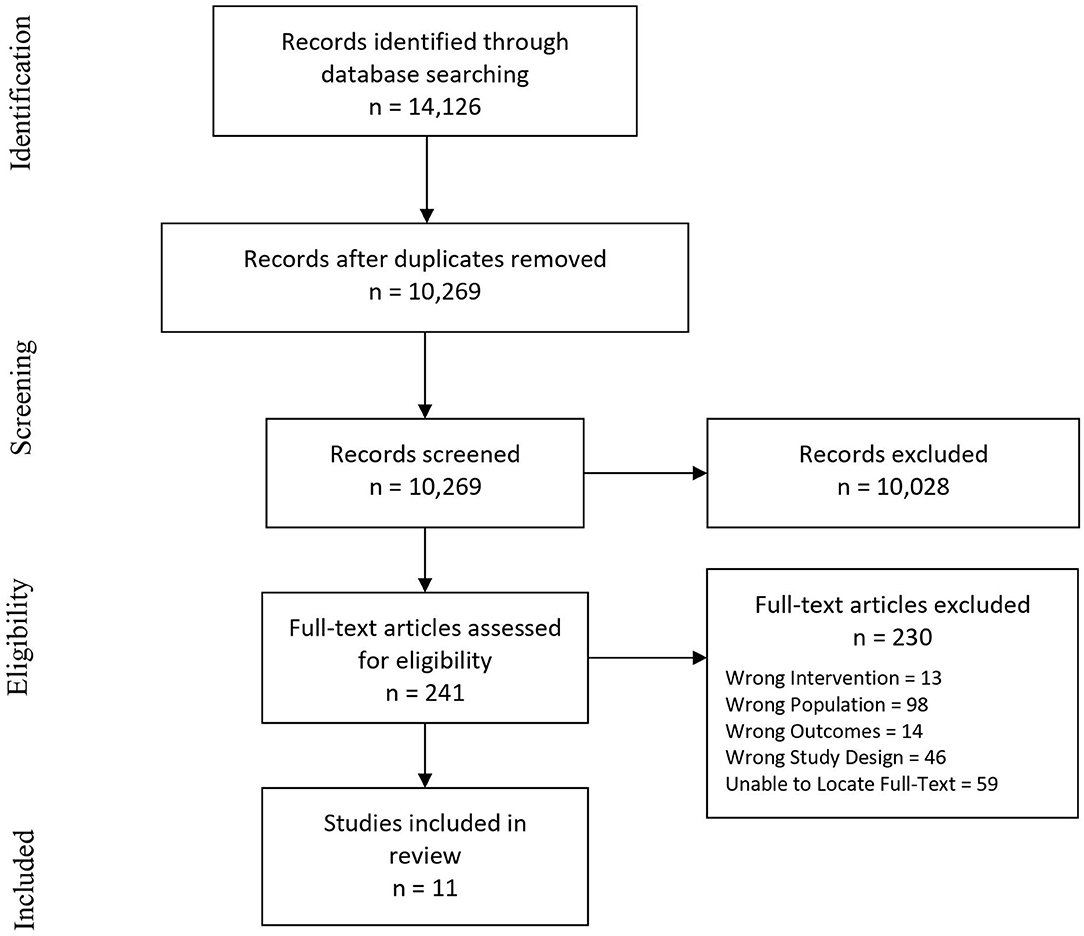

The literature search yielded 14,126 records. EMBASE, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO retrieved 2,293, 3,242, 3,092, and 2,199, respectively. Following duplication removal, 10,269 records remained. In level two screening, 241 full-text articles were assessed, with 230 articles being excluded. Reasons for exclusion included wrong interventions (e.g., not psychological interventions), wrong population (e.g., adult onset ABI), wrong outcomes (e.g., not mental health outcomes), wrong study design (e.g., review articles or editorials), and inability to locate full-text articles. For conference abstracts, attempts were made to contact authors for full-texts.

Following screening, 11 studies remained for final inclusion. Studies were summarized with a focus on key intervention characteristics by using the TIDieR framework. Figure 1 outlines the review process using the PRISMA-ScR.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram adapted from Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & the PRISMA group (2009).

Included studies were conducted in the United States (33–37), United Kingdom (38, 39), Australia (40), Greece (41), Poland (42), and Italy (43). Studies were published between 2010 and 2018. Participant recruitment settings included community clinics, hospitals, universities, medical centres, and rehabilitation centres. Study sample sizes ranged from one to 49, with mean ages ranging from 6.87 to 15.9 years. Conditions studied included CP (36, 39, 41) and childhood onset ABI (33–35, 37, 40, 42, 43), consisting of TBI, with only one study having a variety of ABI conditions (40). No studies reported on interventions for SB. Detailed information of the included studies, including the intervention characteristics using the TIDieR framework and effectiveness/impact, can be found in Tables 1–3.

Commonly identified psychological interventions used with individuals with childhood onset ABI and CP were acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (34, 37, 38, 40), psychotherapy (39, 41), and CBT (33, 35, 36, 42, 43), in combination with components of family therapy (34), psychoeducation (33, 36, 43), and Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP) (40). Studies reporting on ACT were limited to individuals with childhood onset ABI, while studies investigating the use of psychotherapy only included individuals with CP. In contrast, the studies evaluating CBT included individuals with both childhood onset ABI (33, 35, 42, 43) and CP (36). Intervention characteristics of each included study can be found in Tables 1, 2.

ACT interventions focused on increasing awareness of symptoms of distress, accepting them, and noticing when one was trying to avoid the associated thoughts, feelings and/or sensations. Mindfulness and cognitive defusion were key techniques used. Interventions involved group therapy sessions (37, 38, 40), with one study involving individual sessions (34). Groups ranged from two to six people. ACT interventions were also used in combination with family therapy with parents and children with ABI (34), and in combination with Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP), a parenting program aimed at preventing child behavioral and emotional difficulties (40). ACT interventions all occurred in person.

Psychotherapy interventions involved revisiting an individual's past experiences to determine how they may be affecting daily life in the present. Interventions also aimed to extract meaning and break down feelings associated with one's disability. Interventions were delivered during individual sessions with parental supervision (41), or during couple's therapy sessions (39). The two included studies occurred in person and utilized initial sessions to build a therapeutic relationship with the clients. For instance, Barnes and Summers (39) used the activity of drawing genograms to represent family relationships. Florou et al. (41) used systemic and psychodynamic approaches, which consider the problem to belong within a whole system (e.g., the person and all the people in his/her life), while also considering the client's feelings and wishes regarding relationships in his/her life.

CBT interventions involved cognitive restructuring by identifying automatic thoughts and replacing them with more positive thinking. Clients participated in activity scheduling, sleep scheduling, and relaxation techniques. CBT interventions were delivered face-to-face. Peterman et al. (36) conducted sessions with clients and their mothers, while McNally et al. (33) delivered CBT interventions individually or with both the client and his/her parents. Pastore et al. (43) engaged clients in CBT techniques such as cognitive meditation, positive and negative reinforcement, contingent reinforcement and shaping, while Peterman et al. (36) utilized CBT as exposure therapy. Aspects of psychoeducation were also integrated into sessions for both clients and their parents (33, 36, 43). Intervention settings included hospitals (35, 43) and university clinics (36).

Individual sessions ranged from 45 min to 1.5 h, with many studies not indicating session duration (33, 38–40, 43). The majority of sessions occurred weekly (33, 37, 38, 41); however, some were twice or three times a week (42, 43). In the study by Peterman et al. (36), the frequency of sessions were tapered, starting with weekly sessions and progressing toward monthly sessions. Whiting et al. (38) provided clients with a 1-month break before the last session for relapse prevention. Interventions typically ranged from seven to 12 weeks (36–38, 40). In the study conducted by Pastore et al. (43), treatment duration ranged from 4 to 8 months, as treatment length was determined based on the participants' individualized needs. The longest treatment duration lasted 1 year (41, 42).

Individuals providing psychological interventions were labeled under the broad term of “therapist.” In the study by Barnes and Summers (39), the therapist was completing an educational placement under the supervision of a therapist. In three of the 11 studies, psychologists facilitated sessions (33, 40, 42), while McCarty et al. (35) had psychologists and licensed therapists facilitate sessions. McNally et al. (33) identified a licensed clinical psychologist specializing in neuropsychology, or doctoral and postdoctoral-level neuropsychology “trainees” under supervision providing interventions. In terms of additional training to therapists providing interventions, one study indicated that training was provided in order to conduct SSTP (40).

The majority of ACT, CBT, and psychotherapy interventions were reported to be effective for the treatment of mental health symptoms in individuals with CP and ABI. Intervention outcome measures and findings can be found in Table 3.

ACT interventions were reported to significantly decrease anxiety in individuals with post TBI mental health difficulties (34), decrease psychological distress in individuals with severe TBI (38), and decrease avoidance of thoughts and emotions, leading to greater life activity participation (37). When used with SSTP, ACT interventions were found to decrease problem behaviors, and significantly decrease emotional symptoms in individuals with ABI, compared to individuals receiving usual care (40).

Psychotherapy intervention impact was reported in terms of the therapists' opinions on patient progress, rather than the use of outcome measures (39, 41). For example, in the study by Florou et al. (41), the therapist stated psychotherapy was successful as the participant was better able to discuss anxieties and worries and process past traumas.

CBT interventions were effective in reducing depressive symptoms (35, 42, 43), improving emotional function as per parent reports (33), reducing anxiety levels (36, 42, 43), and decreasing behavioral and psychological problems (43). However, when investigating the maintenance of treatment effects post-intervention, mixed findings were reported. Individuals who received ACT and SSTP returned to baseline emotional symptoms after 6-months (40), while individuals receiving CBT continued to decrease in anxiety levels 1-month post-treatment (36).

In addition to the effectiveness of the interventions, two studies considered moderating/mediating variables of the main outcomes. For example, Golinska and Bidzan (42) considered participants' levels of engagement during interventions and its influence. With this, intervention success was affected by client engagement levels (42); with increased engagement associated with increased psychological resources and decreased depressive symptoms (42). Additionally, McNally et al. (33) examined whether length of time since ABI would influence participants' successful outcomes with a given intervention; however, it was found to have no effect.

The purpose of this scoping review was to: (1) determine what psychological interventions have been reported in the literature/evaluated to treat mental health difficulties experienced by individuals with CP, SB, and childhood onset ABI; and (2) identify the key characteristics of these interventions and their effectiveness. A total of 11 studies were included. The psychological interventions identified were ACT, CBT, and psychotherapy, in combination with family therapy, psychoeducation, and SSTP. No studies included individuals with SB. Included studies investigating childhood onset ABI mainly focused on concussions (e.g., mTBI), and TBI, which may limit the generalizability to all individuals with childhood onset ABI. The absence of studies on SB and a variety of ABI conditions, reveals the need for future research in these populations. The low yield of studies available for data abstraction highlights the need for further evidence and psychological support for these populations.

The most commonly reported psychological interventions leading to improved psychological outcomes, included CBT, ACT, and psychotherapy. Included studies provided evidence that CBT interventions decreased behavioral and psychological problems in children and adolescents with mild to moderate TBI (33, 35, 43), stroke (42), and CP (36). These results are similar to other literature investigating the effectiveness of CBT for reducing mental health symptoms amongst individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (44–46) and amongst individuals with epilepsy (47, 48). In a meta-analysis by Perihan et al. (44), findings from 23 studies suggested CBT interventions produced moderate changes in anxiety levels in children with ASD. Additionally, in a study by Carbone et al. (47), adolescents with epilepsy reported improved mental health and social functioning after completing a six module-based CBT intervention.

ACT intervention protocols were shown to improve mood and psychological outcomes in children and adults with childhood onset mild to severe TBI (34, 37, 38) and pediatric ABI (40). These findings are similar to results reported in a study by Pahnke et al. (49), looking at ACT-based skills training groups for adolescents and young adults with high-functioning ASD. The 6-week intervention was aimed at teaching participants acceptance and mindfulness skills to better deal with difficult thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations (49). Positive outcomes were reported from both self- and teacher-reports in regard to decreased stress, hyperactivity, prosocial behavior and emotional symptoms (49).

Lastly, psychotherapy interventions were subjectively reported to improve mental health outcomes in individuals with CP (39, 41). Similar findings were found in individuals with ASD receiving psychotherapy interventions (50, 51). In a study by El-Ghoroury and Krackow (51), psychotherapy interventions resulted in decreased emotional outbursts with a client with ASD.

The findings from this review revealed heterogeneity in terms of key characteristics of intervention protocols across studies. Therefore, it is difficult to determine which intervention characteristics are associated with improved outcomes. Furthermore, some items of the TIDieR framework were also not described in the included studies, making it difficult to comprehensively describe the psychological interventions.

For many of the included studies, study protocols were tailored to the particular client in regard to length of treatment (33, 35), aspects of the intervention the client required (e.g., individualized treatment plans) (41, 43), and how material was presented (39). For example, the Modular Approach to Therapy for children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma and Conduct problems (MATCH-ADTC), uses individualized treatment through the use of treatment modules (52). Modules can be repeated, or additional modules can be added, depending on the patient's response to treatment. This flexible and tailored treatment intervention has been reported to outperform usual care in youth with depression, anxiety, and conduct problems (53). Personalized interventions should utilize evidence-based methods to successfully tailor mental health treatment to clients (54). Evidence-based methods facilitate individualized mental health treatment planning and tailoring by assisting clinicians in determining what order to target problems, and what treatments to combine (53, 54). However, even when utilizing personalized interventions, not all intervention protocols may be feasible or beneficial for all clients with CP, SB, or childhood onset ABI. Future studies should seek to determine and understand how and why interventions are beneficial to certain individuals (54).

We acknowledge several strengths of this scoping review. This review benefitted from an extensive literature search conducted by an experienced informational specialist. The screening and extraction process were completed by two researchers independently. This review was also guided by two well-known frameworks, including PRISMA and TIDieR, ensuring both quality and transparency of studies included.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of this review. First, the literature search was limited to the last 10 years (e.g., 2009–2019), potentially excluding relevant studies published prior to 2009. Second, non-English studies were excluded, potentially creating a bias for English-speaking countries. Third, studies were excluded if they reported on non-traditional interventions such as music therapy or art therapy. Therefore, included studies may not encompass all interventions available. Fourth, the review is limited by a small number of available publications. Many articles did not include participant ages, therefore relevant studies may have been excluded. Relatedly, we included studies involving any participants age 12 and older (i.e., provided the studies met the other inclusion criteria). This meant including some studies with much younger children (e.g., 43, 46). While our original intent was to only include those studies with ≥50% of the sample age 12 and older, upon reviewing these studies, it was not possible to determine the proportion of the sample over the age of 12. Thus, we included these studies as a conservative measure given the relatively low yield of included studies for data abstraction. In the case of the studies involving psychotherapy interventions, impact was reported in terms of the therapists' opinions on patient progress, rather than the use of outcome measures. Lastly, the majority of the studies included small sample sizes, primarily being case studies. Case studies can be considered one of the least rigorous designs, with limited generalizability (55).

This scoping review aimed to synthesize information regarding psychological interventions being evaluated for individuals with childhood onset ABI, CP and SB. CBT, psychotherapy and ACT were found to be effective interventions by decreasing mental health symptoms. Upon completing CBT, psychotherapy, or ACT, individuals with CP and childhood onset ABI, mainly TBI, experienced decreased anxiety, depressive symptoms, and psychological distress. The lack of literature pertaining to interventions for individuals with SB and different types of ABIs (e.g., tumors), in particular, highlights a need for future research within these populations. With modifications and personalization for these individuals, psychological intervention/treatment hold the potential to improve mental health outcomes and transitional care services.

LP ran the search strategy in the various databases. MJ and TP screened articles and abstracted data. All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors developed the search strategy and read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.782104/full#supplementary-material

1. Ramachandra P, Palazzi KL, Skalsky AJ, Marietti S, Chiang G. Shunted hydrocephalus has a significant impact on quality of life in children with spina bifida. PM R. (2013) 5:825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.05.011

2. Young N, McCormick A, Mills W, Barden W, Boydell K, Law M, et al. The transition study: a look at youth and adults with cerebral palsy, spina bifida and acquired brain injury. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (2006) 26:25–45. doi: 10.1080/J006v26n04_03

3. Mukherjee S, Pasulka J. Care for adults with spina bifida: current state and future directions. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. (2017) 23:155–67. doi: 10.1310/sci2302-155

4. Beresford B. On the road to nowhere? Young disabled people and transition. Child Care Health Dev. (2004) 30:581–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00469.x

5. Peter NG, Forke CM, Ginsburg KR, Schwarz DF. Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists' perspectives. Pediatrics. (2009) 123:417–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0740

6. Mudge S, Rosie J, Stott S, Taylor D, Signal N, McPherson K. Ageing with cerebral palsy; what are the health experiences of adults with cerebral palsy? A qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e012551. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012551

7. van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J, Latour JM. Crossing the transition chasm: experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child Care Health Dev. (2011) 37:821–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01261.x

8. Racine E, Bell E, Yan A, Andrew G, Bell LE, Clarke M, et al. Ethics challenges of transition from paediatric to adult health care services for young adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Paediatr Child Health. (2014) 19:65–8. doi: 10.1093/pch/19.2.65

9. Sonneveld HM, Strating MMH, van Staa AL, Nieboer AP. Gaps in transitional care: what are the perceptions of adolescents, parents and providers? Child Care Health Dev. (2013) 39:69–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01354.x

10. Colver A. Transition of young people with disability. Paediatr Child Health. (2018) 28:374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2018.06.003

11. Wright AE, Robb J, Shearer MC. Transition from paediatric to adult health services in scotland for young people with cerebral palsy. J Child Health Care. (2016) 20:205–13. doi: 10.1177/1367493514564632

12. Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. (2011) 96:548–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.202473

13. Burke SL, Wagner E, Marolda H, Quintana JE, Maddux M. Gap analysis of service needs for adults with neurodevelopmental disorders. J Intellect Disabil. (2019) 23:97–116. doi: 10.1177/1744629517726209

14. Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. (2011) 36:375–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq104

15. Erickson JD, Patterson JM, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Risk behaviors and emotional well-being in youth with chronic health conditions. null. (2005) 34:181–92. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc3403_2

16. Sienko SE. An exploratory study investigating the multidimensional factors impacting the health and well-being of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. (2018) 40:660–6. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1274340

17. Bjorgaas HM, Elgen I, Boe T, Hysing M. Mental health in children with cerebral palsy: does screening capture the complexity? Sci World J. (2013) 2013:468402. doi: 10.1155/2013/468402

18. Dicianno BE, Kinback N, Bellin MH, Chaikind L, Buhari AM, Holmbeck GN, et al. Depressive symptoms in adults with spina bifida. Rehabil Psychol. (2015) 60:246–53. doi: 10.1037/rep0000044

19. Max JE, Wilde EA, Bigler ED, MacLeod M, Vasquez AC, Schmidt AT, et al. Psychiatric disorders after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a prospective, longitudinal, controlled study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2012) 24:427–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12060149

20. Stewart M, Barnfather A, Magill-Evans J, Ray L, Letourneau N. Brief report: an online support intervention: perceptions of adolescents with physical disabilities. J Adolesc. (2011) 34:795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.007

21. Warschausky S, Argento AG, Hurvitz E, Berg M. Neuropsychological status and social problem solving in children with congenital or acquired brain dysfunction. Rehabil Psychol. (2003) 48:250–4. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.48.4.250

22. Bennett S, Shafran R, Coughtrey A, Walker S, Heyman I. Psychological interventions for mental health disorders in children with chronic physical illness: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. (2015) 100:308–16. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307474

23. Parkes J, McCusker C. Common psychological problems in cerebral palsy. Paediatrics and Child Health. (2008) 18:427–31. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2008.05.012

24. Kirsh B. Chapter 12: Processes of thought and occupation. In: Krupa T, Kirsh B, Pitts D, Fossey E, editors. Bruce and Borg's Psychosocial Frames of Reference: Theories, Models, and Approaches for Occupation-Based Practice. 4th ed. New Jersey: SLACK Incorporated (2016). p. 191–210.

25. Mayo-Wilson E, Dias S, Mavranezouli I, Kew K, Clark DM, Ades AE, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1:368–76. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3

26. Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2010) 78:169–83. doi: 10.1037/a0018555

27. Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Practice. (2003) 10:125–43. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

28. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Practice. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

29. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implem Sci. (2010) 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

30. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

31. Parrish R, Oppenheimer S. Chapter 8: treatment and management. In: Wolraich M, Dworkin P, Drotar D, Perrin E, editors. Developmental-Behavioural Pediatrics: Evidence and Practice E-book. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier (2008). p. 203–80.

32. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. (2014) 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

33. McNally KA, Patrick KE, LaFleur JE, Dykstra JB, Monahan K, Hoskinson KR. Brief cognitive behavioral intervention for children and adolescents with persistent post-concussive symptoms: a pilot study. Child Neuropsychol. (2018) 24:396–412. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2017.1280143

34. Ashish D, Stickel A, Kaszniak A, Shisslak C. A multipronged intervention for treatment of psychotic symptoms from post-football traumatic brain injury in an adolescent male: a case report. Cur Res. (2017) 4:e32–e37. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606579

35. McCarty CA, Zatzick D, Stein E, Wang J, Hilt R, Rivara FP. Collaborative care for adolescents with persistent postconcussive symptoms: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. (2016) 138:1–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0459

36. Peterman JS, Hoff AL, Gosch E, Kendall PC. Cognitive-Behavioral therapy for anxious youth with a physical disability: a case study. Clin Case Studies. (2015) 14:210–26. doi: 10.1177/1534650114552556

37. Sylvester M. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Improving Adaptive Functioning in Persons With a History of Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury [Doctoral dissertation]. Reno: University of Nevada (2011).

38. Whiting DL, Deane FP, Simpson GK, Ciarrochi J, Mcleod HJ. Acceptance and commitment therapy delivered in a dyad after a severe traumatic brain injury: a feasibility study. Null. (2018) 22:230–40. doi: 10.1111/cp.12118

39. Barnes JC, Summers SJ. Using systemic and psychodynamic psychotherapy with a couple in a community learning disabilities context: a case study. Brit J Learn Disabil. (2012) 40:259–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2011.00704.x

40. Brown FL, Whittingham K, Boyd RN, McKinlay L, Sofronoff K. Improving child and parenting outcomes following paediatric acquired brain injury: a randomised controlled trial of stepping stones triple p plus acceptance and commitment therapy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2014) 55:1172–83. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12227

41. Florou A, Widdershoven M-A, Giannakopoulos G, Christogiorgos S. Working through physical disability in psychoanalytic psychotherapy with an adolescent boy. null. (2016) 23:119–29. doi: 10.1080/15228878.2016.1160834

42. Golinska P, Bidzan M. Neuropsychological rehabilitation of an adolescent patient after intracranial embolization of AVM - a case study. Acta Neuropsychologica. (2018) 16:405–415. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.8040

43. Pastore V, Colombo K, Liscio M, Galbiati S, Adduci A, Villa F, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents with traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. (2011) 33:675–83. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.506239

44. Perihan C, Burke M, Bowman-Perrott L, Bicer A, Gallup J, Thompson J, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for reducing anxiety in children with high functioning ASD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50:1958–72. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03949-7

45. Walters S, Loades M, Russell A. A systematic review of effective modifications to cognitive behavioural therapy for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Rev J Autism Dev Dis. (2016) 3:137–53. doi: 10.1007/s40489-016-0072-2

46. Ooi YP, Lam CM, Sung M, Tan WTS, Goh TJ, Fung DSS, et al. Effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy on anxiety for children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Singapore Med J. (2008) 49:215–20.

47. Carbone L, Plegue M, Barnes A, Shellhaas R. Improving the mental health of adolescents with epilepsy through a group cognitive behavioral therapy program. Epilepsy Behav. (2014) 39:130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.07.024

48. Mehndiratta P, Sajatovic M. Treatments for patients with comorbid epilepsy and depression: a systematic literature review. Epilepsy Behav. (2013) 28:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.03.029

49. Pahnke J, Lundgren T, Hursti T, Hirvikoski T. Outcomes of an acceptance and commitment therapy-based skills training group for students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: a quasi-experimental pilot study. Autism. (2014) 18:953–64. doi: 10.1177/1362361313501091

50. Freitag CM, Jensen K, Elsuni L, Sachse M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Schulte-Rüther M, et al. Group-based cognitive behavioural psychotherapy for children and adolescents with ASD: the randomized, multicentre, controlled SOSTA-net trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2016) 57:596–605. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12509

51. El-Ghoroury NH, Krackow E. A developmental–behavioral approach to outpatient psychotherapy with children with autism spectrum disorders. J Contemp Psychotherapy. (2011) 41:11–7. doi: 10.1007/s10879-010-9155-z

52. Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. Modular Approach to Therapy for Children With Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADTC). Satellite Beach, FL: PracticeWise LLC (2009).

53. Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, et al. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: a randomized effectiveness trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2012) 69:274–82. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147

54. Ng MY, Weisz JR. Annual research review: building a science of personalized intervention for youth mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2016) 57:216–36. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12470

Keywords: psychological intervention, transitions, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, acquired brain injury, scoping review

Citation: Jefferies M, Peart T, Perrier L, Lauzon A and Munce S (2022) Psychological Interventions for Individuals With Acquired Brain Injury, Cerebral Palsy, and Spina Bifida: A Scoping Review. Front. Pediatr. 10:782104. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.782104

Received: 23 September 2021; Accepted: 10 February 2022;

Published: 21 March 2022.

Edited by:

Carl E. Stafstrom, Johns Hopkins Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Jill Edith Cadwgan, Evelina London Children's Hospital, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Jefferies, Peart, Perrier, Lauzon and Munce. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Munce, c2FyYWgubXVuY2VAdWhuLmNh

†These authors share first authorship

‡Senior author

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.