- 1Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

- 2Center for Biomedical Ethics and Society, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

Objective: To describe United States (US) pediatric oncologists’ experiences with treatment refusal or abandonment, exploring types and frequency of decision-making conflicts, and their impact.

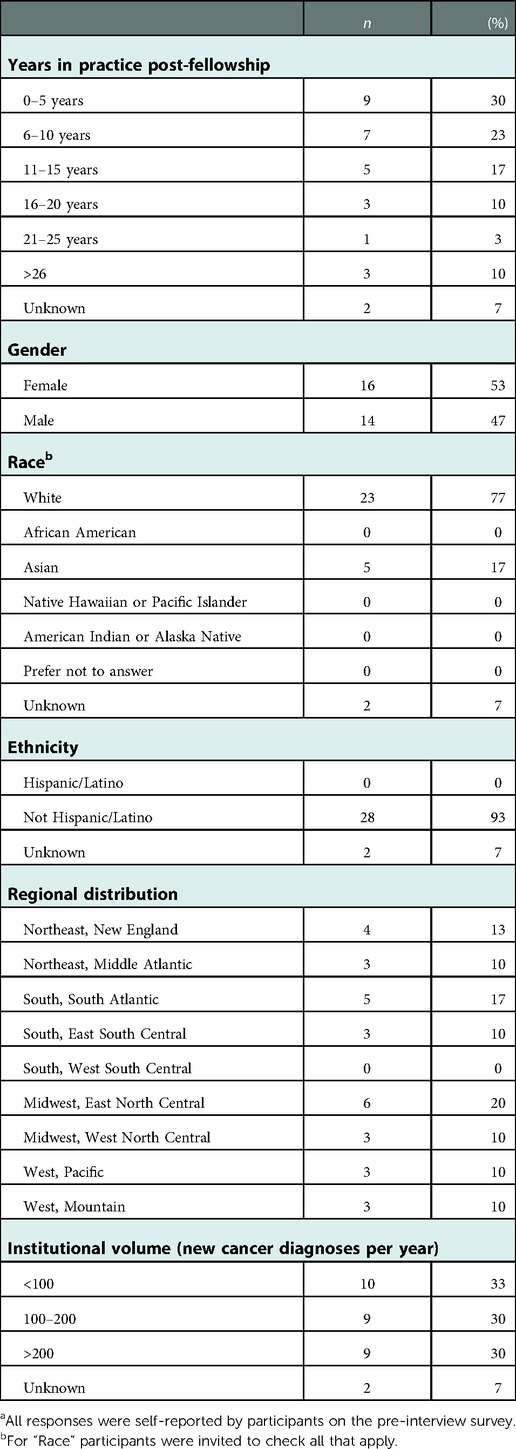

Study design: We conducted exploratory qualitative interviews of pediatric oncologists (n = 30) with experience caring for a pediatric patient who refused or abandoned curative treatment. Interviewees were recruited using convenience and nominated expert sampling, soliciting experiences from diverse geographic locations and institution sizes across the US. We analyzed transcripts using applied thematic analysis to identify and refine meaningful domains.

Results: Many oncologists reported multiple experiences with refusal and abandonment. Most anticipated case frequency would increase due to misinformation, particularly on the internet. Interviewees described cases of treatment refusal and abandonment, but also a wider variety of cases than previously described in existing publications, including cases involving: non-adherence; negotiations for different treatments; negotiations for complementary and alternative medicine; delayed treatment initiation; and refusal of a component of recommended therapy. Cases often involved multiple stages or types of conflicts. Recurring patient/family behaviors emerged: clear opposition to treatment from the outset; hesitancy about treatment despite initiating therapy; and psychosocial circumstances becoming an obstacle to treatment completion. Oncologists revealed substantial professional and personal repercussions of these cases.

Conclusion: Oncologist interviews highlight a broad range of conflicts, yielding a taxonomy of treatment refusal, non-adherence and abandonment (TRNA) that accounts for the heterogeneity of situations described. Cases’ complexity and interrelatedness points to a functional model of TRNA that includes families’ behaviors. This preliminary taxonomy and model warrant further research and examination to refine the model and generate strategies to prevent and mitigate TRNA.

1. Introduction

In high-income countries like the United States (US), cases of children whose families refuse treatment for favorable-prognosis cancers often garner significant media attention (1–8). For example, a highly publicized 2015 case involved a 17-year-old who was involuntarily hospitalized for longer than 4 months to complete treatment because she was regarded as a significant flight risk, and her prognosis deemed too good to forgo treatment (7). The 2006 case of a 15-year-old whose parents were charged with medical neglect for refusing treatment of a highly curable cancer (9, 10), and the attention it attracted, prompted Virginia to pass “Abraham’s Law” (11), granting children at least 14 years old the right to refuse life-saving treatment under certain conditions.

To date, scholarly publications about such cases predominantly consist of single case descriptions and ethical commentaries (10, 12–17), as well as a systematic review (18) that described patterns in published cases and highlighted important gaps in the literature. The only empirical publications are those focusing on pediatric cancer treatment abandonment in low- and middle-income countries (8, 19–25); a survey of German pediatric oncology programs soliciting the number and details of refusal cases (26); and two quantitative surveys of US pediatricians and pediatric oncologists using hypothetical cases, which asked whether they would pursue court-ordered treatment (27) or support the patient’s refusal (28).

Given significant gaps in the literature, a broader conceptual framework [such as has been developed in other areas of medicine (29)] is needed to help: (1) Define and organize types of conflicts between pediatric oncologists and patient/families; (2) Identify factors that mediate and moderate treatment refusal and abandonment; and (3) Examine interventions to address treatment refusal and abandonment (30). To inform such a framework, we conducted exploratory qualitative interviews with pediatric oncologists who reported personal experiences with such cases. In this analysis, we report their experiences with an emphasis on the first two goals; subsequent analyses will describe management strategies and outcomes of reported cases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

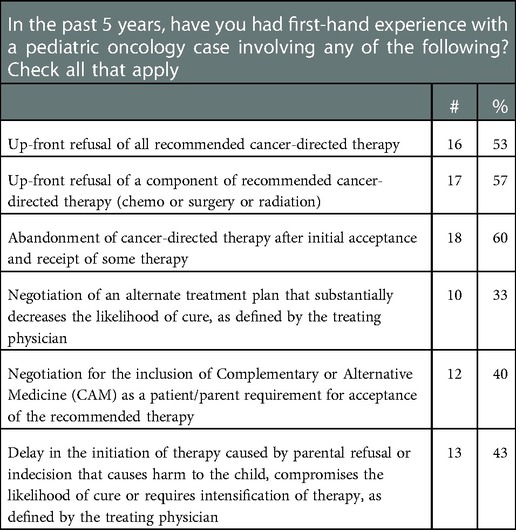

We conducted in-depth interviews with pediatric oncologists in the US. Prospective interviewees were identified through the first author’s professional networks and relationships, as well as nominated expert sampling (31). We endeavored to maximize diversity with respect to gender, race/ethnicity, years of practice, and geographic location. To confirm eligibility, we developed a brief survey eliciting experience with treatment refusal (Table 1).

2.2. Instrument development

We developed a semi-structured interview guide focusing on types of conflicts encountered; factors and strategies considered in response; effects of treatment refusal cases, personally and professionally; the role of ethical frameworks and legal requirements; and the resources needed to manage treatment refusal and abandonment cases. After refinements based on pilot testing, the final instrument (available upon request) comprised 14 questions.

The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board deemed this research exempt under 45 C.F.R. §§46.104(d)(2)(ii).

2.3. Procedures

Interviews were conducted by telephone between May and September 2019 by two experienced team members. At the beginning of each interview, we reviewed a study information sheet and obtained the participant’s verbal agreement to participate and permission for audio recording. Interviews averaged approximately 45 min in length. Participants were offered $100 compensation for their time.

2.4. Data analysis

We uploaded professionally transcribed interviews into qualitative research software NVivo 12 for coding and analysis using standard iterative processes (32, 33). A subset of the data are presented here, with further analyses planned for future manuscripts.

See Appendix 1 for further methodologic details (34).

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

We interviewed 30 pediatric oncologists representing a range of perspectives based on institutional volume, practice location, and time in practice (Table 2). Further, in the pre-interview survey, participants reported a range of experiences with different types of cases (Table 1).

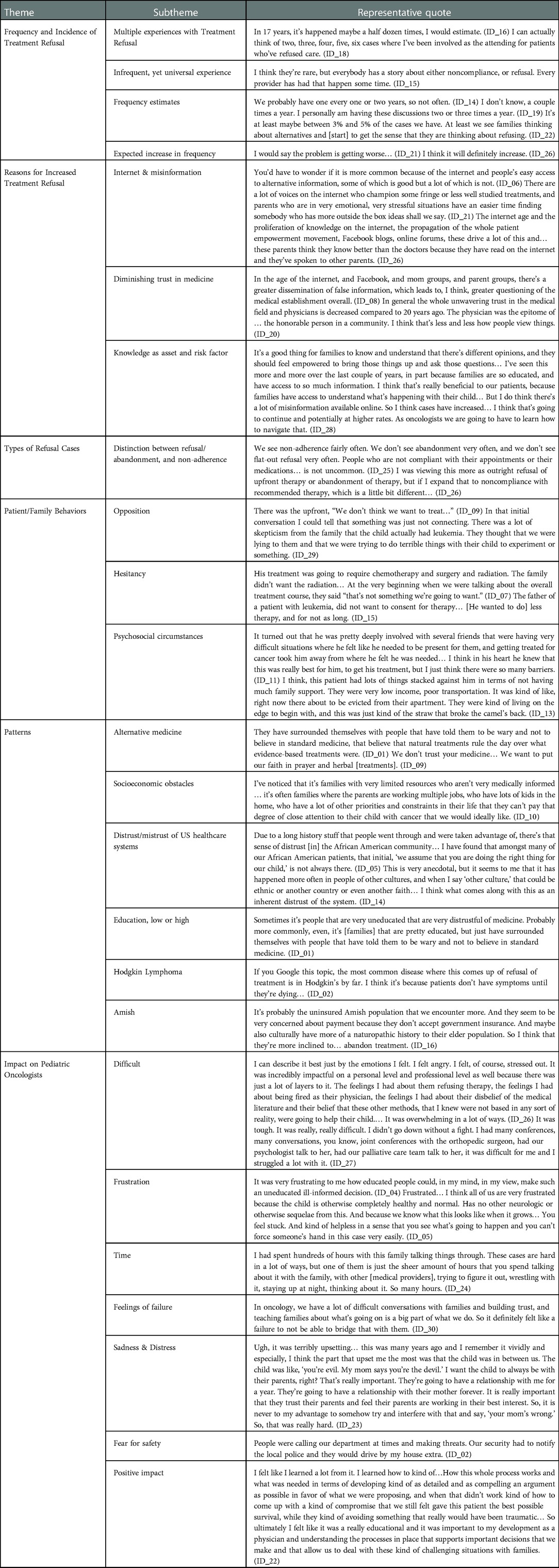

Narrative segments presented here (with participant IDs) are exemplary of frequently mentioned ideas, with additional illustrative quotations in Table 3.

3.2. Frequency of treatment refusal cases

Although we asked interviewees to describe a single treatment refusal case, many noted they had encountered multiple cases over their careers. Most used general terms to describe the incidence of treatment refusal, but some offered numerical estimates such as: “not often… probably one every one to two years” (ID_14), “two to five times a year” (ID_26), and “between three to five percent of cases” (ID_22). Most interviewees observed that, while these cases are relatively uncommon, they expected most oncologists would encounter them at some point.

When asked whether they anticipated changes in the frequency of treatment refusal cases, most thought it would increase. Many cited the internet and “misinformation available online” (ID_28) as reasons, while others described a societal trend of diminishing trust in medicine and “greater questioning of the medical establishment overall” (ID_08).

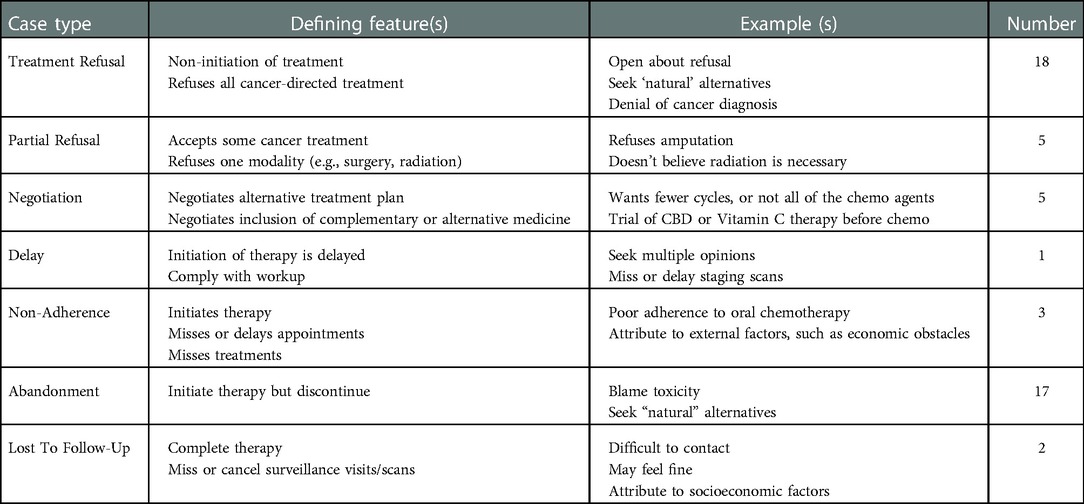

3.3. Types of treatment refusal cases

When asked to describe a specific case of treatment refusal, interviewees described 37 distinct cases. Their narratives highlighted the complexity of these cases, with each following a unique path from diagnosis to conclusion, and many involving multiple stages of conflict. We grouped the cases into 7 categories (Table 4), including upfront refusal of all recommended therapy, upfront refusal of a component of recommended therapy, non-adherence, abandonment, negotiation of an alternative to recommended therapy, negotiation for inclusion of complementary and alternative medicine along with recommended therapy, and delays in the initiation of treatment. Some interviewees also described patients who completed treatment but missed visits to monitor for recurrence.

As conveyed by these categories, many interviewees distinguished between cases of non-adherence and treatment refusal or abandonment:

I haven’t had a lot of patients completely abandon ship, especially once they’ve started, and treatment refusal I think is pretty rare for all of us. We maybe have one or two patients a year who completely refuse chemo… The treatment non-adherence, like not completely taking therapy that’s prescribed, I encounter that every day. (ID_10)

3.4. Recognizing the problem

Interviewees revealed the varied circumstances by which they became aware their patients were unwilling or unable to complete recommended treatment. Some families made their opposition to treatment clear upon receiving the diagnosis and treatment plan. Interviewees described “skepticism from the family that the child actually had [cancer]” (ID_29), families that “really did not trust doctors” (ID_14), and others who “worried about side effects” (ID_09) and preferred to try alternative treatments.

Other interviewees described families who initiated therapy but expressed hesitancy about whether it was necessary, or whether the entirety of the proposed treatment was appropriate. Some opposed one component of multimodal treatment saying it was “not something [they] were going to want” (ID_07), while others negotiated for “less therapy, for not as long” (ID_15). Many families asked about “alternative approaches” (ID_17), and whether alternative medicine “could be used instead of traditional chemotherapy to cure [the cancer]” (ID_08).

I think they were already a little bit skeptical… a little bit on the fence from the outset about giving him chemotherapy. They very much viewed it as a toxin, and just believed there were natural means that could cure him… They agreed to go forward with the chemo on, I think, a hesitant basis and then once he had this side effect, this toxicity, it pushed it over the edge and I think confirmed their misgivings that they had from the beginning. (ID_26)

Finally, some families never questioned the necessity or appropriateness of treatment; instead, psychosocial obstacles eventually proved to be insurmountable for the patient to complete intended treatment. This included families who were “living on the edge to begin with, [and cancer] was the straw that broke the camel’s back” (ID_13). Some interviewees highlighted socioeconomic obstacles that impact families’ “compliance and wanting to stop [treatment]” (ID_17). They cited families with “low income”, “poor transportation” (ID_13), “single parents without money who need to work” (ID_11), and “parents [who] are working multiple jobs” (ID_10) as being at risk.

3.5. Patterns of patient and family behaviors

When asked to describe patterns or predictors that helped identify those at risk for treatment refusal and abandonment, many interviewees described families “asking to integrate… alternative medicine practices into their oncology care” or even “requesting complementary and alternative approaches instead of standard oncology care” (ID_07). Proposed alternatives included “holistic and naturopathic medicine” (ID_07), ranging from “high-dose Vitamin-C” (ID_29) and “herbal treatments” (ID_09) to “CBD oil or medicinal marijuana” (ID_08). Other common proposals included faith-based healing, reflecting beliefs that “God was going to cure” (ID_23) their child through “prayer” (ID_09) and “holy water” (ID_20).

Many cited distrust/mistrust of US healthcare systems as a common thread. Several described general trends of declining trust in “the medical establishment” (ID_01) and increasing “distrust of authority in our culture” (ID_29). Others referenced “inherent distrust of the [healthcare] system” (ID_14) from members of minority and marginalized populations, meaning the “initial, ‘we assume that you are doing the right thing for our child’, is not always there” (ID_05).

Some interviewees reported opposition from families at the extremes of educational backgrounds, with “people that are very uneducated” (ID_01), as well as “very educated families that do all of the research” (ID_05) frequently pushing back against recommendations. Interviewees commonly described families having more access to medical information (vis-à-vis the internet) as both an asset and a risk factor for treatment refusal.

It’s a good thing for families to know and understand that there’s different opinions, and they should feel empowered to bring those things up and ask those questions… I’ve seen this more and more, in part because families are so educated, and have access to so much information… That’s really beneficial, because families understand what’s happening with their child… But there’s a lot of misinformation available online. As oncologists we are going to have to learn how to navigate that. (ID_28)

A few surmised that children with Hodgkin Lymphoma are a higher risk of treatment refusal because most “feel pretty good when they’re diagnosed” (ID_04) and “don’t have symptoms until they’re dying” (ID_02), making it difficult to convince the family that the side effects of chemotherapy are justified.

Finally, multiple interviewees reported that Amish families seemed more likely to abandon treatment, either because of “concerns about payment” or because of cultural interest in “more of a naturopathic” approach (ID_16).

3.6. Impact of treatment refusal cases on pediatric oncologists

Many interviewees reported they had “struggled a lot” (ID_27) with these cases that “kept [them] up at night” (ID_03), describing how difficult and “overwhelming” (ID_26) it was at the time.

They frequently described feelings of frustration, including bringing “that frustration home” (ID_10). For some, the frustration was that such “educated people could… make such an uneducated, ill-informed decision (ID_04). Other frustrations were at not being able “to get through [to them] and help” (ID_06).

Many emphasized the “inordinate amount of time” (ID_4) and resources dedicated to these cases. One interviewee spent “hundreds of hours with [the] family talking things through,” in addition to “so many hours” spent “talking with other medical providers… and staying up at night thinking about it” (ID_24).

Some referenced feelings of failure or “self-doubt” (ID_3) at not being able to “build trust” (ID_30) and convince a family to agree to treatment. Because oncologists “have a lot of difficult conversations with families and building trust and teaching families… is a big part of what [oncologists] do” (ID_30), a “broken relationship is a failure… to figure out how to partner with that family” (ID_07).

Some interviewees were “obviously very sad for the high likelihood of losing the patient” (ID_20), and also distressed about the impact on the family unit, such as having parents divided about the child’s treatment, or that the disagreement suggested to the child that their parents might not be “working in their best interest” (ID_23).

In rare cases, interviewees described fear for the safety of the medical team: “People were calling our department at times and making threats. Our security had to notify the local police and they would drive by my house” (ID_02). One recounted a parent encounter involving immediate physical danger:

He kind of blocked the door, [saying] something along the lines of, ‘How do you sleep at night? How do you look in the mirror? I hope you're proud of yourself’, sort of this, ‘you won and at what cost, you’re a terrible person.’ Then he, kind of blocking the door, stood up and advanced on me. I remember literally thinking only, ‘How do I get out of this room?’ I remember feeling so afraid for my own safety. (ID_07)

4. Discussion

The majority of US children diagnosed with cancer will be cured of their disease (35). Unfortunately, not all patients complete optimal treatment due to treatment refusal or abandonment. Anecdotally, treatment refusal has long been discussed between colleagues, with cases only rarely published in the medical literature. A systematic review emphasized the significant gaps and publication bias, and highlighted the need to report and study effective strategies and solutions to these conflicts (18).

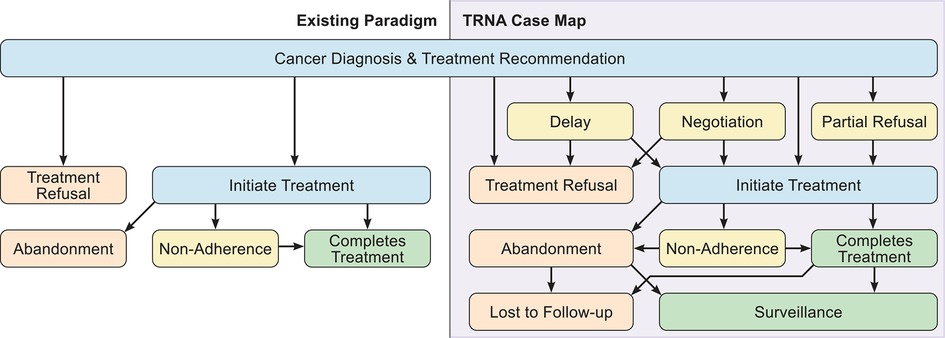

This exploratory study sought to begin addressing this need by eliciting US pediatric oncologists’ experiences managing treatment refusal cases. One major goal was to examine the types of cases experienced, to help generate a taxonomy. Multiple publications emphasize the importance of adopting consistent and precise terminology to identify and document cases of incomplete treatment, ascertain underlying causes, and devise solutions (30, 36, 37). Referencing “semantic chaos”, Weaver et al. propose an algorithm to distinguish categories of treatment incompletion across chronic conditions (including cancer), noting the need for “disease- and context-specific” refinement (30). Most US cases in the literature are either upfront refusal of treatment (Refusal) or discontinuation of treatment (Abandonment). Some of our interviewees viewed non-adherence as a separate, unconnected problem from refusal and abandonment. However, the complexity of cases we learned about suggests that while non-adherence is a distinct concept [and there are diverse causes or subcategories that warrant different interventions (30)], it is not disconnected from refusal and abandonment. Multiple cases where non-adherence preceded abandonment indicates that they must coexist in a comprehensive functional model, and that a taxonomy based on a false separation between non-adherence and refusal and abandonment would result in an over-simplified model. Our data suggest that these conflicts may be more accurately termed treatment refusal, non-adherence, or abandonment (TRNA).

Further, our interviewees described complicated, multifaceted experiences that require a nuanced model to account for the full range of conflicts that may preclude receipt of recommended treatment. Many cases included multiple conflicts during the arc of the patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment. Some patients refused treatment upfront, eventually initiated therapy, only to ultimately abandon treatment. Other patients were non-adherent to treatment, before eventually abandoning therapy altogether. The TRNA case map derived from our interviewees’ cases (Figure 1) depicts this complexity and interconnectedness. This taxonomy should provide for more accurate classification of conflicts, an important precursor to examining interventions that might mitigate or overcome TRNA (30, 36).

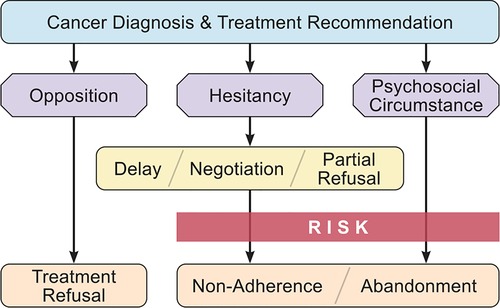

A functional model of TRNA would ideally identify patients at risk for non-completion of treatment, and direct oncologists to a set of interventions targeted to their particular circumstance (30). Across our interviewees, three main patterns common to TRNA cases emerged in our analysis. The first involved families with immediate and persistent opposition to cancer treatment. Some denied the child had cancer, while others were opposed to conventional treatments (e.g., radiation, chemotherapy). These cases of Treatment Opposition were apparent from the beginning of the relationship with the patient, akin to parents with firm opposition to childhood vaccination (38). A second pattern involved families hesitant about the recommended treatment. Some initially opposed it or questioned the length or necessity for all components, yet ultimately initiated (if hesitancy was apparent upfront) or continued treatment (if hesitancy was expressed mid-treatment). These Treatment Hesitant parents may be similar to vaccine hesitant parents who require effective communication strategies to agree to childhood immunizations (38, 39). The third pattern involved families who had Psychosocial Circumstances that became significant impediments to completing treatment, resulting in either non-adherence or abandonment. Naturally these circumstances may co-exist within a case where a family opposes or hesitates about treatment, however in some cases they appeared to be the sole factor in treatment non-adherence or abandonment. These three patterns overlap significantly with core issues that have been described as occurring in difficult relationships between pediatric oncologists and parents of children with cancer: problems of connection and understanding, confrontational parental advocacy, mental health issues, and structural challenges to care (40). We combined these patterns with the taxonomy of conflicts to create a functional model for future study and guidance for pediatric oncologists (Figure 2).

A second major goal of our study was to describe the frequency and impact of these cases. While treatment refusal is generally considered to be rare, our interviewees commonly reported multiple experiences with TRNA and the considerable impact it had on them. Some cases demanded substantial professional resources and time, and many burdened oncologists with feelings of distress, failure, and even fear of physical safety.

Our study was exploratory and descriptive in nature, and utilized a purposive recruitment strategy intended to gather a range of experiences reflecting the diversity of pediatric oncology practices in the US. Our findings may be specific to the US context (and possibly other high-income countries) and not fully applicable to pediatric oncology care and treatment incompletion in other settings. Further, given time and resource constraints, our interviews with thirty pediatric oncologists focused in depth on one case they had experienced; our results do not encompass every TRNA case they had encountered or that other oncologists may encounter. While participants were diverse with respect to geography, gender, and practice experience, most self-reported their race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic white or Asian. It is possible that pediatric oncologists from historically marginalized communities might have different experiences and viewpoints on some cases of TRNA, and exploring their perspectives is an important area for future study. Even so, because this study constitutes the only systematic examination of unpublished cases, our taxonomy and functional model provide an important step toward better understanding TRNA.

We carried out these interviews in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite changes in the socio-political environment during these years, we believe our results reflect a taxonomy of cases that endures across time. While the pandemic has led to delays in pediatric cancer diagnoses (41–44), to our knowledge no studies describe changes in attitudes toward pediatric cancer treatment. If anything, the seemingly widespread embrace of unproven, unscientific COVID-19 treatments likely reflects increasing skepticism of science, which we anticipate could result in more frequent TRNA cases. Furthermore, the socioeconomic stressors of the pandemic, such as virtual schooling and lost jobs, may exacerbate the psychosocial conditions that increase the risk of non-adherence and abandonment. Further research will be needed to explore any shifts in trends over time.

5. Conclusion

In the analysis presented here, we characterized the landscape of TRNA cases experienced by our interviewees. Our findings suggest that pediatric oncologists will need to navigate TRNA multiple times during their professional careers, and to cope with potentially profound personal and professional impact. We hope the proposed taxonomy and functional model serves as a foundation for ongoing conceptual and empirical work to understand and address TRNA. Future examination and analyses of our data are expected to shed light on some of the compromises, solutions, and strategies interviewees employed to overcome hesitancy, and the factors that went into their decisions about whether and when to involve the judicial system.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality considerations, but are available upon reasonable request from qualified researchers conducting IRB approved studies that fall within the scope of the study purpose and data use described to interviewees at the time of participation. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Daniel Benedetti,ZGFuaWVsLmJlbmVkZXR0aUB2dW1jLm9yZw==.

Author contributions

DB and LB conceptualized and designed the study. DB, LB and CH-A designed the interview guide. DB and CD recruited participants. CH-A interviewed participants. DB and LB supervised data collection, and CD coordinated data collection. LB supervised data coding and analyses. DB, CH-A and CD coded transcripts. DB led data analyses, and CH-A assisted with data analyses. DB drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version, and agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Society at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, as well as the Pediatric Oncology Population Sciences Program at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.1049661/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Kondro W. Boy refuses cancer treatment in favour of prayer. Lancet. (1999) 353(9158):1078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76446-1

2. Blumenthal R. Hodgkin's returns to girl whose parents fought state: standoff ends as court hears test results. N Y Times Web. (2005) 11:A8.15966116

3. The Associated Press. Texas Judge orders treatment for a 13-year-old with cancer. N Y Times Web (2005) 10:A15.

4. Nealon P. Runaway teenager calls family in Norwell; youth left home over cancer treatments. The Boston Globe (1994).

5. Associated Press. Judge rules family can’t refuse chemo for boy: parents of 13-year-old sought to treat his cancer with alternative medicine (2009). Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/judge-rules-family-cant-refuse-chemo-boy-flna1c9453606 (Accessed August 31, 2022).

6. Perez A, Jaffe M. Amish girl with leukemia, family flee us to avoid chemotherapy (2013). Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/US/amish-girl-leukemia-family-flees-us-avoid-chemotherapy/story?id=21040115 (Accessed August 31, 2022).

7. Briggs B. Connecticut teen with curable cancer must continue chemo: court (2015). Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/health/cancer/connecticut-teen-curable-cancer-must-continue-chemo-court-n282421 (Accessed August 31, 2022).

8. Lam C, Curco N, Ribeiro R. Global snapshots of treatment abandonment in children and adolescents with cancer: social factors, implications and priorities. J Healthcare Sci Hum. (2012) 2(1):81–110.

9. Caplan AL. Challenging teenagers’ right to refuse treatment. Virtual Mentor. (2007) 9(1):56–61. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2007.9.1.oped1-0701

10. Mercurio MR. An adolescent's refusal of medical treatment: implications of the abraham cheerix case. Pediatrics. (2007) 120(6):1357–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1458

12. Ackerman TF. Parental refusal of treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. (1994) 11(1):31–3. doi: 10.1177/104345429401100108

13. Alessandri AJ. Parents know best: or do they? Treatment refusals in paediatric oncology. J Paediatr Child Health. (2011) 47(9):628–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02170.x

14. Holder AR. Parents, courts, and refusal of treatment. J Pediatr. (1983) 103(4):515–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(83)80575-7

15. Hord JD, Rehman W, Hannon P, Anderson-Shaw L, Schmidt ML. Do parents have the right to refuse standard treatment for their child with favorable-prognosis cancer? Ethical and legal concerns. J Clin Oncol. (2006) 24(34):5454–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4709

16. Lansky SB, Vats T, Cairns NU. Refusal of treatment: a new dilemma for oncologists. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (1979) 1(3):277–82. doi: 10.1097/00043426-197923000-00012

17. Lyren A, Boozang KM. The abuse of alternative medicine? Hastings Cent Rep (2003) 33(5):13. doi: 10.2307/3528630

18. Caruso Brown AE, Slutzky AR. Refusal of treatment of childhood cancer: a systematic review. Pediatrics. (2017) 140(6):1–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1951

19. Bonilla M, Rossell N, Salaverria C, Gupta S, Barr R, Sala A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of abandonment of therapy among children with cancer in El Salvador. Int J Cancer. (2009) 125(9):2144–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24534

20. Njuguna F, Mostert S, Slot A, Langat S, Skiles J, Sitaresmi MN, et al. Abandonment of childhood cancer treatment in western Kenya. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. (2014) 99:609. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305052

21. Mostert S, Sitaresmi MN, Gundy CM, Sutaryo , Veerman AJ. Influence of socioeconomic status on childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment in Indonesia. Pediatrics. (2006) 118(6):e1600–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3015

22. Naderi M, Esmaeili Reykande S, Tabibian S, Alizadeh S, Dorgalaleh A, Shamsizadeh M. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: refusal and abandonment of treatment in the southeast of Iran. Turk J Med Sci. (2016) 46(3):706. doi: 10.3906/sag-1412-42

23. Slone JS, Chunda-Liyoka C, Perez M, Mutalima N, Newton R, Chintu C, et al. Pediatric malignancies, treatment outcomes and abandonment of pediatric cancer treatment in Zambia. PLoS One. (2014) 9(2):e89102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089102

24. Friedrich P, Lam CG, Itriago E, Perez R, Ribeiro RC, Arora RS. Magnitude of treatment abandonment in childhood cancer. PLoS One. (2015) 10(9):e0135230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135230

25. Friedrich P, Lam CG, Kaur G, Itriago E, Ribeiro RC, Arora RS. Determinants of treatment abandonment in childhood cancer: results from a global survey. PLoS One. (2016) 11(10):1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163090

26. Zuzak TJ, Kameda G, Schutze T, Kaatsch P, Seifert G, Bailey R, et al. Contributing factors and outcomes of treatment refusal in pediatric oncology in Germany. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2016) 63(10):1800–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26111

27. Talati ED, Lang CW, Ross LF. Reactions of pediatricians to refusals of medical treatment for minors. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 47(2):126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.004

28. Nassin ML, Mueller EL, Ginder C, Kent PM. Family refusal of chemotherapy for pediatric cancer patients: a national survey of oncologists. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2015) 37(5):351–5. doi: 10.1097/mph.0000000000000269

29. Lowe D, Ryan R, Santesso N, Hill S. Development of a taxonomy of interventions to organise the evidence on consumers’ medicines use. Patient Educ Couns. (2011) 85(2):e101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.024

30. Weaver MS, Arora RS, Howard SC, Salaverria CE, Liu YL, Ribeiro RC, et al. A practical approach to reporting treatment abandonment in pediatric chronic conditions. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2015) 62(4):565–70. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25403

31. Namey EE, Trotter RT. Qualitative research methods. In: Guest G, Namey EE, editors. Public health research methods. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2015). p. 442–82.

32. Bernard H, Ryan G. Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc (2010).

33. Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. (2012).

34. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (coreq): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19(6):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

35. Seer cancer statistics review, 1975-2016. National Cancer Institute (2018). Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/

36. Mostert S, Arora RS, Arreola M, Bagai P, Friedrich P, Gupta S, et al. Abandonment of treatment for childhood cancer: position statement of a siop podc working group. Lancet Oncol. (2011) 12(8):719–20. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70128-0

37. Weaver MS, Howard SC, Lam CG. Defining and distinguishing treatment abandonment in patients with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2015) 37(4):252–6. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000319

38. Dube E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2013) 9(8):1763–73. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657

39. MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. (2015) 33(34):4161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

40. Mack JW, Ilowite M, Taddei S. Difficult relationships between parents and physicians of children with cancer: a qualitative study of parent and physician perspectives. Cancer. (2017) 123(4):675–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30395

41. Ding YY, Ramakrishna S, Long AH, Phillips CA, Montiel-Esparza R, Diorio CJ, et al. Delayed cancer diagnoses and high mortality in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67(9):e28427. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28427

42. O'Neill AF, Wall CB, Roy-Bornstein C, Diller L. Timely pediatric cancer diagnoses: an unexpected casualty of the COVID-19 surge. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67(12):e28729. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28729

43. Carai A, Locatelli F, Mastronuzzi A. Delayed referral of pediatric brain tumors during COVID-19 pandemic. Neuro Oncol. (2020) 22(12):1884–6. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa159

Keywords: bioethics, childhood cancer, abandonment, non-adherence, pediatric oncology, ethics

Citation: Benedetti DJ, Hammack-Aviran CM, Diehl C and Beskow LM (2023) Landscape of pediatric cancer treatment refusal and abandonment in the US: A qualitative study. Front. Pediatr. 10:1049661. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.1049661

Received: 18 October 2022; Accepted: 20 December 2022;

Published: 9 January 2023.

Edited by:

Amos Hong Pheng Loh, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, SingaporeReviewed by:

Chetan Anil Dhamne, National University of Singapore, SingaporeAlix Eden Seif, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, United States

© 2023 Benedetti, Hammack-Aviran, Diehl and Beskow. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel J. Benedetti ZGFuaWVsLmJlbmVkZXR0aUB2dW1jLm9yZw==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Pediatric Oncology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics

Daniel J. Benedetti

Daniel J. Benedetti Catherine M. Hammack-Aviran2

Catherine M. Hammack-Aviran2