- 1Primary Care Pediatrician, Italian National Health System (INHS), ASL Rm1, Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Division of Medicine, St. Mary's Hospital - Imperial College NHS Healthcare Trust, London, United Kingdom

- 3Section of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4Centre for Pediatrics and Child Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

- 5European Society of Emergency Paediatrics, European Society of Emergency Medicine, Brussels, Belgium

- 6European Academy of Paediatrics (EAP), Brussels, Belgium

- 7Medical School, European University Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

- 8Department of Paediatrics, Larnaca General Hospital, Larnaca, Cyprus

- 9ChildCare WorldWide—CCWWItalia OdV, Padova, Italy

- 10Primary Care Pediatrician, Italian National Health System (INHS), ASL Rm 6, Rome, Italy

- 11Primary Care Pediatrician, Italian National Health System (INHS), ASL Rm 3, Rome, Italy

- 12Patient Safety Department, Meuhedet Health Services, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 13Dana Dwek Children's Hospital, Tamsc, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 14Department of Pediatrics, Adelson School of Medicine, Ariel University Pediatrics, Ariel, Israel

- 15Department of Pediatrics, Maccabi Health Care Services Pediatrics, Tel Aviv, Israel

COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent rigid social distancing measures implemented, including school closures, have heavily impacted children's and adolescents' psychosocial wellbeing, and their mental health problems significantly increased. However, child and adolescent mental health were already a serious problem before the Pandemic all over the world. COVID-19 is not just a pandemic, it is a syndemic and mentally or socially disadvantaged children and adolescents are the most affected. Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) and previous mental health issues are an additional worsening condition. Even though many countries have responded with decisive efforts to scale-up mental health services, a more integrated and community-based approach to mental health is required. EAP and ECPCP makes recommendations to all the stakeholders to take action to promote, protect and care for the mental health of a generation.

The pandemic

The World Health Organization (WHO) declaration on March 11, 2020 that the disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was an ongoing global pandemic and it forced almost all countries in Europe, and all over the world, to implement rigid social distancing measures, including strict lockdowns and school closures, to limit the transmission of the infection in the community. These measures heavily impacted children and adolescents' psychosocial wellbeing and, as a result, the incidence of sleep disturbances, anxiety, mood disorders, depression, eating problems, mental health problems and suicide (ideation, attempts or deaths) has significantly increased almost globally (1–9).

Leading experts on child health, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, declared a national state of emergency in child and adolescent mental health in October 2021 (10).

This crisis falls upon an already serious problem, that began emerging way before the Pandemic broke, of rising child and adolescent mental issues. In fact, in 2019 the estimated prevalence of mental disorders for boys and girls aged 10–19, was 16.3 per cent, while the global figure for the same age group was 13.2 per cent in the same year. This means that more than 9 million adolescents aged 10–19 in Europe lived with a mental disorder (11).

The cost of mental disorders in Europe

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, poor mental health related issues costed the EU 4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in lost productivity and social expenses (12). We need to utilize effective strategies to strengthen families to respond, care, and protect a future for their children (11) and to promote a comprehensive and strong mental health system policy response (11) for adults and an increasing prevalence of mental conditions in young people (10–24 years) has been observed across several European countries between 1990 and 2019 (13), at the present, this situation has worsened (11). If the problem is not urgently addressed, through cost-effective interventions (14), this pandemic may have long term adverse consequences on children's and adolescents' mental health (15), as well as on the world economy, because these children grow into adults affected by mental health issues (16). In 2022 mental disorders account for at least 18% of global disease burden, and the associated annual global costs are projected to be US$ 6 trillion by 2030 (17). Hence, identifying cost-effective interventions is important for effective mental health care allocation, while is also essential that the intervention strategies are effective in reducing the burden of disease within the constraints of the allocated resources (18).

A syndemic

Moreover, COVID-19 is not just a pandemic, it is a syndemic, defined as: “Two categories of disease interacting within specific populations—infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and an array of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The syndemic nature of the threat we face means that a more nuanced approach is needed if we are to protect the health of our communities” (19). Most of the studies reported that the stress that children and adolescents have been subjected to, due to school closures and social distancing during the pandemic, impacted their mental health producing negative and different side effects (20–23), depending on their age, gender, ethnicity, family circumstances, socioeconomic situation (22, 24). Greater negative effects on any pre-existing mental health problem (25) and heavier mental health outcomes were found in those who already had poor mental health before the COVID-19 pandemic (26, 27). Furthermore, countries' health outcomes were influenced by local political decisions and media intervention, following public reactions, allowing for a major difference in morbidity and mortality within and between countries.

The mental health impacts on children and adolescent of differing policies may have different impacts. German children and adolescents presented more mental health and quality of life problems after the COVID-19 pandemic (24), even though the incidence and mortality rates in Germany were low when compared to countries such as Spain, Italy or China, or Portugal and their lockdown measures were less severe than in these countries (24, 28).

Therefore, our approach should be to analyze and intervene on this pandemic as “individual countries syndemics”, to emphasize local influences that determined better or worse outcomes, when comparing with other countries (29).

Children and adolescent response to the pandemic is linked to their parents' support and the mentally or socially disadvantaged ones are the most affected

Beyond morbidity, pandemics carry secondary impacts, such as children orphaned or bereft of their caregivers. Such children often face adverse consequences, including poverty, abuse, and institutionalization (30).

Children's psychological response to the outbreak is strongly related to how their parents experienced the events (31) during the pandemic, especially if exacerbated by financial and material hardship (32). On the other hand, caregivers' coping and caregiver–child relationships are strongly related to children's and adolescents' emotional and behavioral functioning (33, 34).

Overall, stress levels in caregivers decreased over time, but stress specifically related to caregiving responsibilities worryingly continued to increase (35). Altogether, a close caregiver–child relationship was protective (36) and conducive for strengthening family relationships (37, 38); whereas, conversely, a strained caregiver–child relationship led to high-conflict interactions owing to increased exposure to stress, maltreatment, and depression within families (39–41). Therefore, if depression or anxiety in a child or adolescent are suspected, family and caregivers' roles and wellbeing are crucial (6, 7, 42, 43).

Mental health problems worsened especially in children and adolescents who already had a disorganized attachment or were affected by pre-existing behavioral problems like autism and Attention Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), not only immediately after stress exposure but even later. Adolescents, particularly, were more likely to experience high rates of depression, stress, and anxiety during and after pandemic, with increased substance abuse, suicide, relationship problems and school problems (44, 45). Moreover, robust evidence shows that high levels of stress (toxic stress) can influence the psychophysical development of children and adolescents, and the highest levels of stress (toxic stress) typically occur in low-income families (15).

Preexisting suffering from Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs), as diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, or neurodevelopmental issues proved to be an additional worsening condition (46, 47). NCDs are a massive contributor to COVID-19 mortality and severe illness across all age groups. The response to coronavirus has constrained children and adolescents with NCDs and severely disrupted their access to essential services, furthermore they are more likely to live in more financially stressed families and may have been more vulnerable to additional financial stress as a result of the pandemic (47).

How the educational services answered to the children and adolescents needs during pandemic

Despite the attempt to maintain educational services through online tools, mental health support for young people was substantially discontinued. However, schools are not just places where students develop and progress their academic skills (48, 49): the daily routine and social interactions that they experience there can help them maintain good mental health. Moreover, the role of the school, in some countries as United States (50), or France (51) is even wider, covering not only primary needs but also representing a preventive reference point as well to identify conditions of maltreatment and neglect. Closing the schools determined a twofold negative effect, firstly, it prevented the identification of prolonged abuse and neglect, secondly, it lenghthen the exposure to these conditions. Thus, school closures have substantially contributed to the weakening of protective factors (52–54), particularly for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds (26, 55) and not all young people have been comfortable using digitally enabled services for support (56). Moreover, schools and universities can offer additional opportunities to modify NCD risk factors, favoring primary prevention across the life-course and improving knowledge of NCDs impact, promoting healthy behaviors and policies related to correct nutrition and physical activity, with the aim of thwarting obesity and diabetes, and control tobacco and alcohol use (57). Therefore, school closure and rigid social distancing measures for a long time should be avoided (1–3, 6, 45–47, 53).

The way forwards

National and regional health policies should be based on evidence-based, effective strategies, tailored to children and young people's specific needs shared with local researchers and experts in the field (7, 11, 53, 57, 58). Even though many countries have responded with decisive efforts to scale-up mental health services, a more integrated and community-based approach to mental health is required (11, 59). The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) recommended to implement professional guidelines into practice and harmonize psychiatric clinical practice across Europe to monitor the treatment outcomes of patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing mental disorders; to keep psychiatric services active by using all available options (for example telepsychiatry); to increase communication and cooperation between different health care providers. Anyway, significant differences between countries emerged in service delivery and often traditional face-to-face visits were replaced by online remote consultations (60).

The unpredictability and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic would have required a more sustainable and flexible adaptations of delivery systems for mental health care, even specifically designed to mitigate disparities in health-care provision (61).

Pediatric providers are not always at the forefront of policy negotiations, but they are most certainly on the frontline of the child and family behavioral health crisis. Therefore, pediatric providers can be a powerful influencing policy, with their on the-ground experience caring for families whose well-being has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic (62).

What works according to the evidence

1. The following interventions have been shown to be effective in decreasing mental health problems in children and adolescents (2, 3, 45, 46, 52, 63):

– community based social support services specifically addressed to mental health problems in children and adolescents with primary care working in partnership with multidisciplinary mental health staff

– clinician-led mental health and psychosocial services of support in schools and universities

– positive coping skills, parent-child discussions mediating, art-based programs.

Recommendations from EAP and ECPCP

The EAP and the ECPCP strongly believe that action is necessary to reduce the negative effects of the pandemic on children's and adolescents' mental health and to advocate for an improved, integrated, and family-focused behavioral health system (11, 42, 58, 62).

Recommendations to the authorities

– promoting families' supportive interventions and resources in addressing mental health problems in children and young people should be implemented, especially in primary care (11, 15, 53, 59, 62, 63), scaling up the existing mental health support in education and healthcare systems, in close connection with multidisciplinary networks (11, 53, 59, 62)

– adequate funding should be made available for increasing service capacities for the resources we are directing families to contact

– adequate funding should be made available to scientific research on positive and negative long-term effects of COVID-19 pandemic and prolonged social distancing measures on the mental health of children and young people, as well the influence of specific risk factors evolving over time, to guiding future public health policies (59, 62–64)

– information for children and young people and their parents outlining warning signs of mental health problems, how to recognize them and how to find help, should be published (11)

Recommendations to educational services for children and adolescents

– students support to remain in school and in education should be a priority especially for young people at risk of early school leaving, for comorbidities, low income and/or ethnic minority backgrounds, previous mental health issues or substance use disorders, to avoid disruptions in learning (53, 59)

– mental health support services and information dissemination in schools and universities, with easier access to in-person services, should be urgently resumed (11, 53, 54)

– mental health hotlines by phone or online services providing emergency support to young people should be maintained and adequately funded, whilst further evidence on their effectiveness is being collected (11, 53, 54)

– school administrators should be aware of the resources available for children and young people and their parents outlining warning signs of mental health problems, how to recognize them and how to find help and they should signpost these resources to all of them (11, 52, 53, 59).

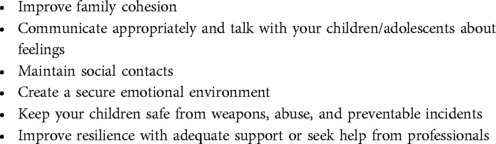

Recommendations to all parents and caregivers

– they should ask for support from primary care professionals to intercept early signals of stress, to improve family well-being and decrease the psychological impact of SARS CoV-2 Pandemic on their children (58, 65, 66), see Table 1

Several open access parenting resources are freely accessible, also on non-smartphones devices, as the Internet of Good Things_IoGT (67).

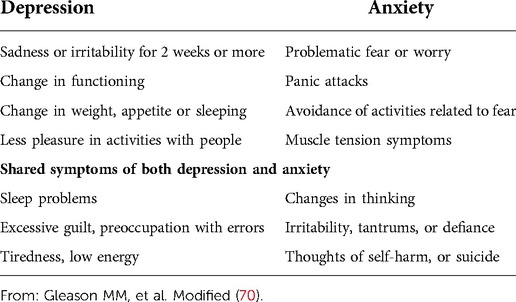

– they should be aware about the signs or symptoms of anxiety or depression in their children and adolescent (68–70), to look out for and to timely recognize them and seek for professional support. Primary care pediatricians can discuss signs and indicators of mental health concerns with parents and caregivers to increase identification of mental health needs. Guidelines for these discussions are presented in Table 2.

Recommendations to pediatricians

• working together with all the other health care professional with expertise in the field, pediatricians:

– should actively participate in multidisciplinary networks, including psychologists and psychiatrists, to support parents, children, and adolescents at risk (53, 58, 59)

– should produce guidelines necessary to policy makers to alleviate the negative effects of Pandemic (11, 53, 59)

– should continue to work in a holistic and family-oriented manner, exploring both issues related to the physical health and issues related to the psychosocial context (11, 53, 58, 59)

• working together with parents/caregivers and educators, pediatricians:

– should be aware of the specific resources available for children, adolescents, and their parents, and should also signpost these to them, outlining warning signs (11)

– should work together with parents and teachers to monitor children's and adolescents' suspect signs of depression and anxiety with specific screening questionnaires, during health care visits in primary care, and treat them with targeted and shared treatment plans, or refer when needed (48, 49, 54, 55, 62)

– should talk properly with children and adolescents about depression and anxiety issues (11, 70)

– should monitor over time the duration, evolution, and outcomes of children and adolescents needs and mental health problems (11, 45, 62)

• working together with politicians, pediatricians

– should campaign to policy makers to create a tailored and integrated net between health and social services, according to resources and prevalence of mental health problems in each European country (11, 42, 45–47, 53, 59)

– should promote investment policies for enhancing well-being (11, 42, 45–47, 53, 59, 62), improved integration of social and health services in families, in schools or at the community level, especially for high-risk populations (low-income families, comorbidities, previous mental health diseases) (11, 53, 57–59)

– must inform politicians about the available strategies and treatments needed to help children and adolescents to thwart the pandemic adverse effects (53, 59)

– must require a specific multiprofessional and integrated medical education on mental health problems management, as well as adequate allocation of funds targeted for this purpose (11, 42, 53, 56, 59).

Conclusions

While exacerbating negative consequences for mental health, the pandemic also offers us an opportunity to rethink our approach and to build back better by investing in a comprehensive approach to mental health that is fit for the future, as proposed by UNICEF World's Children Report 2021. COVID-19 is not the first microorganism to threaten humanity, and probably will not be the last. We need to utilize effective strategies to strengthen families to respond, care, and protect a future for their children (11) and to promote a comprehensive and strong mental health system policy response (11, 58). This means increasing access to mental health services, expanding, and developing a family-focused mental health workforce, also promoting the integration of mental health in pediatric primary care and improving school's services (62).

All children and adolescents, regardless of their social and health conditions, need and have the rights to safe, secure, inclusive homes, schools, and social environments in which to develop and thrive (11) according to the principles of social justice mentioned in the ISSOP statement (71), following the pediatric integrated care models (72, 73), for mental health also (74, 75), and the Nurturing Care Framework principles (76).

We have a historic chance to commit, communicate and take action to promote, protect and care for the mental health of a generation (11).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

LR conceived the work and wrote the manuscript, NRG substantially contributed to the work revision and interpretation of data for the work, HA revising it critically for important intellectual content, DTS contributed to the work revision, CP and RI contributed to the acquisition, and analysis of the data, KM and BS contributed to the work revision and added important intellectual content, GZ gave substantial contributions to the design of the work and interpretation of data for the work, giving also important intellectual content. All the authors gave the final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bhopal SS, Bagaria J, Bhopal R. Risks to children during the COVID-19 pandemic: some essential epidemiology. Br Med J. (2020) 369:m2290. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2290

2. Saulle R, Minozzi S, Amato L, Davoli M. Impact of social distancing for COVID-19 on youths’ physical health: a systematic review of the literature. Recenti Prog Med. (2021) 112(5):347–59. doi: 10.1701/3608.35872

3. Minozzi S, Saulle R, Amato L, Davoli M. Impact of social distancing for COVID-19 on the psychological well-being of youths: a systematic review of the literature. Recenti Prog Med. (2021) 112(5):360–70. doi: 10.1701/3608.35873

4. Nearchou F, Flinn C, Niland R, Subramaniam SS, Hennessy E. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17(22):8479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228479

5. Ma L, Mazidi M, Li K, Li Y, Chen S, Kirwan R, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Affect Disord. (2021) 293:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.021

6. Araújo LA, Veloso CF, Souza MC, Azevedo JMC, Tarro G. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). (2021) 97(4):369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008

7. Berger E, Jamshidi N, Reupert A, Jobson L, Miko A. Review: the mental health implications for children and adolescents impacted by infectious outbreaks—a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2021) 26(2):157–66. doi: 10.1111/camh.12453

8. Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, Saxena J, Saxena K, Williams L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. (2021) 147:e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280

9. Bartek N, Peck JL, Garzon D, VanCleve S. Addressing the clinical impact of COVID-19 on pediatric mental health. J Pediatr Health Care. (2021) 35:377–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.03.006

10. AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. http://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mentaldevelopment/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescentmental-health/

11. The State of the World's Children (2021). https://www.unicef.org/eu/reports/state-worlds-children-2021

12. Mental health problems costing Europe heavily—OECD https://www.oecd.org/health/mental-health-problems-costing-europe-heavily.htm

13. Castelpietra G, Knudsen AKS, Agardh EE, Armocida B, Beghi M, Iburg KM, et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2022) 16:100341. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100341

14. Schmidt M, Werbrouck A, Verhaeghe N, Putman K, Simoens S, Annemans L. Universal mental health interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review of health economic evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2020) 18(2):155–75. doi: 10.1007/s40258-019-00524-0

15. Nelson CA, Scott RD, Bhutta ZA, Harris NB, Danese A, Samara M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. Br Med J. (2020) 371:m3048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3048

16. McGorry PD, Mei C, Chanen A, Hodges C, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Killackey E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry. (2022) 21(1):61–76. doi: 10.1002/wps.20938

17. Campion J, Javed A, Lund C, Sartorius N, Saxena S, Marmot M, et al. Public mental health: required actions to address implementation failure in the context of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. (2022) 9(2):169–82. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00199-1

18. Kularatna S, Hettiarachchi R, Senanayake S, Murphy C, Donovan C, March S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of paediatric mental health interventions: a systematic review of model-based economic evaluations. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22:542. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07939-x

19. Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet. (2020) 396(10255):874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6

20. Viner R, Russell S, Saulle R, Croker H, Stansfield C, Packer J, et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176(4):400–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5840

21. de Figueiredo CS, Sandre PC, Portugal LCL, Mázala-de-Oliveira T, da Silva Chagas L, Raony Í, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 106:110171. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

22. Kauhanen L, Wan Mohd Yunus WMA, Lempinen L, Peltonen K, Gyllenberg D, Mishina K, et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2022) Aug 12:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02060-0

23. Rajmil L, Hjern A, Boran P, Gunnlaugsson G, Kraus de Camargo O, Raman S, et al. Impact of lockdown and school closure on children's Health and well-being during the first wave of COVID-19: a narrative review. BMJ Paediatr Open. (2021) 5(1):e001043. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001043

24. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2022) 31(6):879–89. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5

25. Rogers AA, Ha T, Ockey S. Adolescents’ perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: results from a U.S.-based mixed-methods study. J Adolesc Health. (2021) 68(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039

26. Samji H, Wu J, Ladak A, Vossen C, Stewart E, Dove N, et al. Review: mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2022) 27(2):173–89. doi: 10.1111/camh.12501

27. Du N, Ouyang Y, Xiao Y, Li Y. Psychosocial factors associated with increased adolescent non-suicidal self-injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:743526. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.743526

28. Pizarro-Ruiz JP, Ordóñez-Camblor N. Effects of COVID-19 confinement on the mental health of children and adolescents in Spain. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:11713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91299-9

29. Courtin E, Vineis P. COVID-19 as a syndemic. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:763830. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.763830

30. Hillis SD, Unwin HJT, Chen Y, Cluver L, Sherr L, Goldman PS, et al. Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: a modelling study. Lancet. (2021) 398(10298):391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01253-8

31. Rudolph CW, Zacher H. Family demands and satisfaction with family life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Couple Fam Psychol Res Pract. (2021) 10:249–59. doi: 10.1037/cfp0000170

32. Center for Translational Neuroscience A hardship chain reaction: financial difficulties are stressing families’ and young children's wellbeing during the pandemic, and it could get a lot worse. Medium. (July 30, 2020). https://medium.com/rapid-ec-project/a-hardship-chain-reaction-3c3f3577b30

33. Cooper K, Hards E, Moltrecht B, Reynolds S, Shum A, McElroy E, et al. Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. (2021) 289:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.016

34. Li X, Zhou S. Parental worry, family-based disaster education and children's Internalizing and externalizing problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. (2021) 13:486–95. doi: 10.1037/tra0000932

35. Adams EL, Smith D, Caccavale LJ, Bean MK. Parents are stressed! patterns of parent stress across COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:626456. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626456

36. Penner F, Hernandez Ortiz J, Sharp C. Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority hispanic/latinx US sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 60(4):513–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027

37. Cornell S, Nickel B, Cvejic E, Bonner C, McCaffery KJ, Ayre J, et al. Positive outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Health Promot J Austr. (2022) 33(2):311–9. doi: 10.1002/hpja.494

38. Egan SM, Pope J, Moloney M, Hoyne C, Beatty C. Missing early education and care during the pandemic: the socio-emotional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young children. Early Child Educ J. (2021) 49:925–34. doi: 10.1007/s10643-021-01193-2

39. Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2020) 51:671–82. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x

40. Lawson M, Piel MH, Simon M. Child maltreatment during the COVID- 19 pandemic: consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 110(Pt 2):104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709

41. Wolf JP, Freisthler B, Chadwick C. Stress, alcohol use, and punitive parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. (2021) 117:105090. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105090

42. Panchal U, Salazar de Pablo G, Franco M, Moreno C, Parellada M, Arango C, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) Aug 18:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w

43. Fong VC, Iarocci G. Child and family outcomes following pandemics: a systematic review and recommendations on COVID-19 policies. J PediatrPsychol. (2020) 45:1124–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa092

44. Panda PK, Gupta J, Chowdhury SR, Kumar R, Meena AK, Madaan P, et al. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Pediatr. (2021) 67(1):fmaa122. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmaa122

45. Meherali S, Punjani N, Louie-Poon S, Abdul Rahim K, Das JK, Salam RA, et al. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: a rapid systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(7):3432. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073432

46. Jones EAK, Mitra AK, Bhuiyan AR. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(5):2470. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052470

47. Bhutta ZA, Hauerslev M, Farmer M, Lewis-Watts L. COVID-19, children and noncommunicable diseases: translating evidence into action. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106(2):141–2. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319923

48. Kern L, Mathur SR, Albrecht SF, Poland S, Rozalski M, Skiba R. The need for school-based mental health services and recommendations for implementation. School Ment Health. (2017) 9:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12310-017-9216-5

49. Weist MD, Flaherty L, Lever N, Stephan S, Van Eck K, Bode A. The history and future of school mental health. In: Harrison J, Schultz B, Evans S, editors. School mental health services for adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press (2017). p. 3–23.

50. Nguyen LH. Calculating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on child abuse and neglect in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. (2021) 118:105136. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105136

51. Massiot L, Launay E, Fleury J, Poullaouec C, Lemesle M, Guen CG, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on child abuse and neglect: a cross-sectional study in a French child advocacy center. Child Abuse Negl. (2022) 130(Pt 1):105443. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105443

52. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education: international evidence from the Responses to Educational. Disruption Survey (REDS) https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380398

53. Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy. OECD Legal Instruments. https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0420

54. Considerations for School-Related Public Health Measures in the Context of COVID-19. By WHO, UNICEF and UNESCO. https://www.unicef.org/documents/considerations-school-relatedpublic-health-measures-context-covid-19

55. Knowles G, Gayer-Anderson C, Turner A, Dorn L, Lam J, Davis S, et al. COVID-19, social restrictions, and mental distress among young people: a UK longitudinal, population-based study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2022) 63(Nov; 11):1392–404. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13586

56. Remote learning and digital connectivity. UNICEF. https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/remote-learning-and-digital-connectivity/

57. Bay JL, Hipkins R, Siddiqi K, Huque R, Dixon R, Shirley D, et al. School-based primary NCD risk reduction: education and public health perspectives. Health Promot Int. (2017) 32(2):369–79. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daw096

58. Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma G, Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113429. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429

59. Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response. ©OECD 2021. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/supportingyoung-people-s-mental-health-through-the-covid-19-crisis-84e143e5/#boxsection-d1e1

60. Rojnic Kuzman M, Vahip S, Fiorillo A, Beezhold J, Pinto da Costa M, Skugarevsky O, et al. Mental health services during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: results from the EPA ambassadors survey and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. (2021) 64(1):e41. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2215

61. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, Jones N, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7(9):813–24. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2; Erratum in: Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8(7):e16.32682460

62. Long M, Coates E, Price OA, Hoffman SB. Mitigating the impact of coronavirus disease-2019 on child and family behavioral health: suggested policy approaches. J Pediatr. (2022) 245:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.02.009

63. Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Pastore M, Fasolo M. Parents’ stress and Children's psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713

64. Bussières EL, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Meilleur A, Mastine T, Hérault E, Chadi N, et al. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on Children's mental health: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:691659. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.691659

65. Education: From disruption to recovery. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

66. Stassart C, Wagener A, Etienne A-M. Parents’ perceived impact of the societal lockdown of COVID-19 on family well being and on the emotional and behavioral state of walloon Belgian children aged 4 to 13 years: an exploratory study. Psychol Belg. (2021) 61(1):186–99. doi: 10.5334/pb.1059

67. Talking about Covid-19.IoGT. https://www.internetofgoodthings.org/en/sections/parentscaregivers/covid-19-parenting/talking-about-covid-19/

68. Cluver L, Lachman JM, Sherr L, Wessels I, Krug E, Rakotomalala S, et al. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395(10231):e64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4; Erratum in: Lancet. (2020) 395(10231):1194.32220657

69. Mental illness in children: Know the signs. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthylifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/mental-illness-in-children/art-20046577

70. Gleason MM, Thompson LA. Depression and anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176(5):532. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0052

71. Spencer N, Raman S, O'Hare B, Tamburlini G. Addressing inequities in child health and development: towards social justice. BMJ Paediatrics Open. (2019) 3:e000503. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000503

72. Wolfe I, Lemer C, Cass H. Integrated care: a solution for improving children's Health? Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101(11):992–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304442

73. Burkhart K, Asogwa K, Muzaffar N, Gabriel M. Pediatric integrated care models: a systematic review. Clin Pediatr. (2020) 59(2):148–53. doi: 10.1177/0009922819890004

74. Yonek J, Lee CM, Harrison A, Mangurian C, Tolou-Shams M. Key components of effective pediatric integrated mental health care models: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174(5):487–98. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0023

75. White K, Stetson L, Hussain K. Integrated behavioral health role in helping pediatricians FindLong term mental health interventions with the use of assessments. Pediatr Clin North Am. (2021) 68(3):685–705. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2021.02.006

76. Nurturing Care for Early Child Development. https://nurturing-care.org/

Keywords: anxiety, depression, lockdown, pandemic, stress, SARS-CoV-2, psychological impact, syndemic

Citation: Reali L, Nijman RG, Hadjipanayis A, Del Torso S, Calamita P, Rafele I, Katz M, Barak S and Grossman Z (2022) Repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health: A matter of concern—A joint statement from EAP and ECPCP. Front. Pediatr. 10:1006596. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.1006596

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 24 October 2022;

Published: 28 November 2022.

Edited by:

Paolo Biban, Integrated University Hospital Verona, ItalyReviewed by:

Genevieve Graaf, University of Texas at Arlington, United States© 2022 Reali, Nijman, Hadjipanayis, Del Torso, Calamita, Rafele, Katz, Barak and Grossman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: L. Reali ZWxsZXJlYWxpQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ== Z. Grossman emdyb3NtYW5AbmV0dmlzaW9uLm5ldC5pbA==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Children and Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pediatrics

L. Reali

L. Reali R. G. Nijman

R. G. Nijman A. Hadjipanayis

A. Hadjipanayis S. Del Torso

S. Del Torso P. Calamita

P. Calamita I. Rafele

I. Rafele M. Katz

M. Katz S. Barak

S. Barak Z. Grossman

Z. Grossman