94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Pediatr. , 08 April 2021

Sec. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.653230

This article is part of the Research Topic Molecular and Genetic Mechanisms in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: From Bench to Bedside View all 10 articles

To improve care for the estimated 17.1 million children with psychiatric disorders in the United States (1), it is critical to explore all possible connections to better understand these disorders' origins. The onset of neurodevelopmental/psychiatric disorders varies person-to-person. However, even for disorders diagnosed after infancy, there is a growing appreciation that the origins of these disorders are at the earliest stages of brain development—prenatally. Furthermore, not only is it crucial to understand what is unusual during development, but also why this occurs.

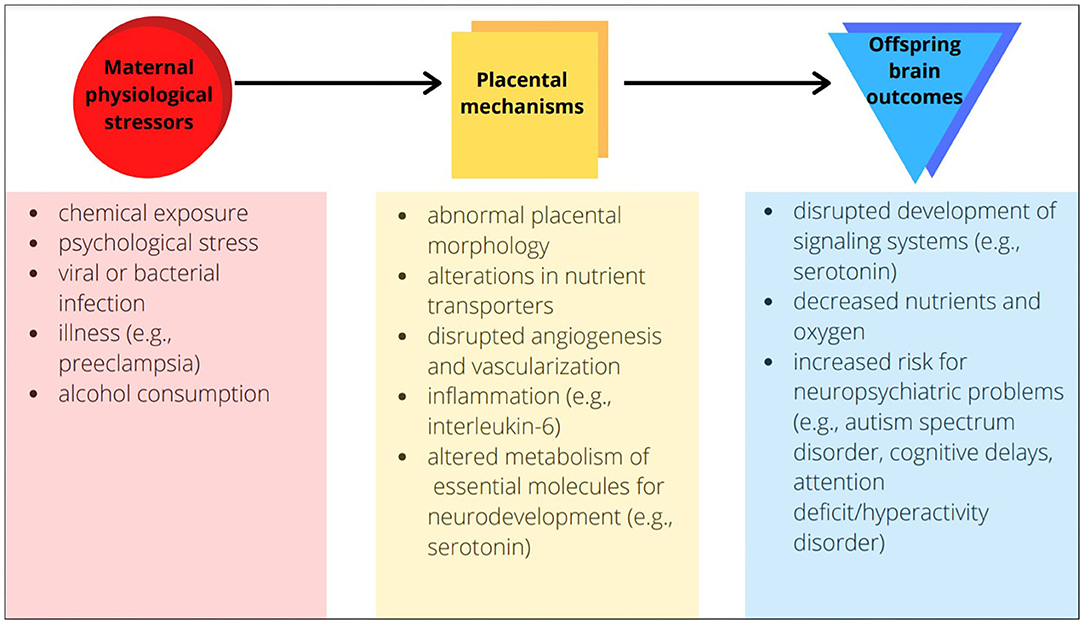

A significant contributor to abnormal prenatal brain development is physiological stress during pregnancy (2–6). Physiological stress induces a significant shift from homeostasis, and may arise from chemical exposures, psychological stress, infections, and illnesses such as preeclampsia or gestational diabetes. Epidemiological studies link maternal stress with offspring neurodevelopmental impairments (2), and animal studies have demonstrated causality of this relationship. For example, preeclampsia—a disorder with disrupted maternal vascular and immune biology—increases risk of neuropsychiatric problems among children (3). Evidence has come from human and non-human preeclampsia studies implicating what in the offspring brain has changed: its morphology, white matter, and vasculature. When we ask the further question of why these changes occur with preeclampsia or any maternal stress, it is critical to consider the biology of not only mother and offspring but also their link—the placenta. Changes in placenta may be a critical factor for offspring neurodevelopment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of placental mechanisms as the link between maternal physiological stressors and offspring brain outcomes.

The placenta forms after conception and is delivered along with the offspring. During gestation, placenta serves as the mediator between mother and fetus, supplying nutrients and oxygen to the fetus and removing waste and CO2. The role of the placenta has been emphasized previously, and continues to warrant attention when examining disorders with developmental origins (7). Many cultures bury the placenta after birth, out of respect for its role as a “guide” through pregnancy or its link to the child's future (8). The level of respect for the placenta these cultures offer seems fitting, as growing evidence suggests its importance in long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The nutrient and waste exchange of the placenta that supports fetal development is just part of its critical role. The placenta also produces critical hormones, growth factors, proteins for metabolizing endogenous molecules (e.g., 11βHSD2 breakdown of elevated cortisol in normal pregnancy to limit fetal exposure) or transporting exogenous factors (e.g., efflux transporters for xenobiotic chemicals), and other molecular substrates (e.g., such as serotonin which is directly supplied to the fetal brain (9–11). All of these factors impact fetal development and regulate communication between the separate but linked biological domains of the mother and fetus. These processes of normal pregnancy are dependent on proper placental structural formation and its function throughout gestation (12). Maternal physiological factors may influence the structure and function of the placenta's unique connection between mother and baby. To better understand the placenta, it is important to understand general periods of placental development:

Beginning of Gestation: Placental villi are multi-layered folds of tissue in which fetal and maternal blood vessels come in close contact (13). Villous and extravillous structures form as a result of the proliferation and differentiation of trophoblast cells, which arise during the earliest divisions of cells in the embryo. The villous and extravillous structures physically anchor the placenta into the uterus and allow gas and nutrient exchange and other functions.

First Half of Gestation: Trophoblasts undergo the most changes. For example, some trophoblasts replace endothelial cells that make up the uterine spiral arteries to ensure adequate fetal blood supply. This mechanism also serves to protect the placenta from potentially harmful fluctuations in oxygen levels (14).

Second Half of Gestation: Extensive angiogenesis and vascularization occurs. The formation of new blood vessels allows blood to enter the trophoblast cell-lined sinuses in the uterus and continue to meet the nutritional and other physiological needs of the growing offspring (15).

Abnormal placental morphology and function have significant impacts on fetal outcome. For example, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has been linked to offspring risk for metabolic, cardiovascular, and neuropsychiatric problems including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ADHD, depression, anxiety, and cognitive delay (16). Maternal diabetic abnormalities may have direct impacts on fetal metabolism, changing levels of specific nutrients and hormones. However, studies have also found in GDM models that maternal hyperglycemia leads to decreased placental glucose transporters (17). This in turn may lead to decreased fetal glucose, further leading to delays, as glucose is a critical nutrient (13). GDM also induces altered metabolism and placental development and function at early stages which may be responsible for excessive fetal growth (13). Specifically, inflammatory and cellular stress pathways in placental cells such as NF-κB signaling or ER stress likely play a role in GDM (18). Evidence suggests that abnormal maternal metabolism stimulates both adipose and placental cells, increasing production of inflammatory cytokines that then may influence the fetus in multiple ways (19).

Other maternal factors, including bacterial or viral infections such as influenza, can elicit increased inflammatory cytokines which may alter placental function. Maternal immune activation (MIA) during pregnancy has been linked with an increased risk for neuropsychiatric risk in offspring, including ASD (20).

Animal models show that influenza infection during pregnancy alters the placenta in multiple ways. After maternal influenza, overall placental growth is reduced (21), as well as reduced labyrinth zone thickness, suggesting that disrupted vascular development of the placenta occurs and then likely reduces nutrient and oxygen exchange (22). Maternal influenza also alters the expression of a significant number of placental genes, mainly implicating inflammatory, immune, and hypoxia pathways but also overlapping with risk genes for neuropsychiatric disorders (23). In these studies, placentas also showed cellular abnormalities including thrombi and elevated immune cell number. Offspring brain showed persistent changes in some key neuronal genes many weeks after this maternal exposure (23). At the same time, no viral genes were found in placenta or offspring brain, suggesting indirect pathways for brain alterations such as placental morphological and functional changes.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) affects up to 1.5 of every 1,000 births in the United States (24). FASD includes low body weight, poor coordination, and cardiovascular complications. Children with FASD experience neurodevelopmental challenges such as hyperactive behavior, poor memory, and speech and language delays. As with other maternal physiological disruptions, the role of the placenta may be critical for impacts of gestational alcohol exposure.

Disruptions to placental vascular structure and function may be a mechanism involved in the origins of FASD. Increased glucocorticoid levels with alcohol consumption (25) may play a role in reduced blood flow, given known impacts of cortisol on placental angiogenesis (26). In human placentae from pregnancies in which women were prospectively assessed to have used alcohol, levels of two angiogenic proteins vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and annexin-A4 (ANX-A4), were reduced (27). VEGFR2 and ANX-A4 both enhance proliferation, migration, and survival of the endothelial cells critical for placental blood vessels, suggesting that maternal and/or fetal blood flow that underlies many other placental functions may be dysregulated A trend increase of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNFα, in placenta after alcohol exposure also suggests that placental processes sensitive to inflammation, such as serotonin production, may be affected. This study reveals different aspects of placental abnormality than other assessments showing a higher rate of placenta accreta with gestational alcohol exposure (28). Placenta accreta occurs when trophoblast cells invade the uterine wall abnormally, which suggests altered initial placentation due to alcohol exposure. Placenta accreta can lead to complications during delivery and may be managed by pre-term cesarean delivery, both of which are linked to increased neurodevelopmental risk for children (29).

The aforementioned studies demonstrate examples of common maternal conditions with placental abnormalities that have also been linked to neurodevelopmental abnormalities of offspring. There are many other factors that can influence placental changes and therefore development of offspring; for example, regardless of maternal physiology, infant neurodevelopment has also been correlated with placental epigenetic variation (30). What is apparent from these studies is that the placenta's role is more than a waystation for the fetal brain to be exposed to molecules from maternal circulation. The impact of placenta nutrient transport, serotonin production, and hormone regulation are significant, as general development of the fetus has been found to be negatively influenced when these functions are abnormal (31). Additionally, a range of maternal physiological stresses impact placenta function (gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal infection). These forms of maternal stress and others may have overlapping neurodevelopmental impacts on offspring because of overlapping placental abnormalities.

In the examples discussed above, maternal conditions during pregnancy are linked both with improper function of the placenta as well as with increased likelihood of neurodevelopmental problems in offspring. The critical nature of the placenta for neurodevelopmental changes is hypothesized from such descriptive studies, but few studies have been able to causally connect placental abnormalities directly to altered brain development.

The impact of alcohol on placental growth factor (PLGF) has been explored for its mechanistic role in disruptions of fetal brain vasculature in mice. With CRISPR-Cas9 mediated over-expression of the PLGF gene in placenta, the reduced proportion of cerebrocortical radial vessels with maternal alcohol consumption is corrected to normal levels (32).

Maternal immune activation (MIA), a risk factor for ASD, involves elevation of maternal IL-6, a proinflammatory cytokine responsive to infections. Sophisticated work has shown that the impact of IL-6 on the placenta is the critical mediator of MIA effects on offspring neurodevelopment (20). A specific transgenic removal of placental IL-6 receptor, through the CYP19Cre driver (a transgene under the control of the aromatase cytochrome P450 19), resulted in offspring protected from the impacts of MIA in brain and behavior. Other findings from this work suggest that IL-6 signaling may play this critical role because it impacts placental angiogenesis and vascular permeability, hormone production, or further inflammatory signaling cascades in fetal circulation.

Another study has implicated the placenta's adaptation to nutrient deprivation (i.e., maternal starvation) as a way to protect offspring hypothalamus neurodevelopment—a critical brain region for hormonal regulation. During mouse gestation, expression of the gene Peg3 is coordinated in the fetal hypothalamus and placenta, coordinating multiple other genes that regulate both placental and hypothalamic development (33). Following food deprivation, this pattern is uncoupled, with Peg3 expression increased in fetal hypothalamus and decreased in placenta. This study demonstrates also that this maternal starvation stress advances hypothalamic cell growth, despite the reduction in nutrients due to breakdown of placental cells from decreased Peg3 expression. Poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in the setting of maternal starvation may represent failure of this protective mechanism.

Maternal inflammation can be linked through the placenta to disrupted serotonin development in the fetal brain, particularly in the forebrain where serotonin plays a role in emotional regulation circuits. Specifically, MIA disrupts placental tryptophan metabolism, including altered expression of genes that synthesize serotonin [tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1]. Interestingly, controlled investigations of isolated placental and brain tissue after MIA also shows that TPH1 activity is increased only in placenta, but serotonin levels increase in fetal brain. Ultimately this increase in serotonin delivered to fetal brain suppresses normal outgrowth of fetal serotonin axons (34).

The placenta has a temporary role in development during gestation—despite its time-limited presence, impacts of its function are clear well into adulthood. The impact of maternal illness or exposures during pregnancy on neuropsychiatric functioning of the next generation may well be heavily influenced by the health and performance of the placenta. If prenatal brain developmental changes from maternal physiological stresses that contribute to ASD, cognitive delays, or other neuropsychiatric problems originate in the placenta, finding ways to protect its structure and function are critical. Moreover, the placenta is a much more accessible biological target than the developing fetal brain for such interventions. Therefore, understanding mechanisms by which it influences the fetal brain, such as inflammatory signaling and serotonin production, will allow for more protective measures to be developed for healthy brain development in children.

SK and HS conceived the manuscript. SK, HS, and SM wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Work on this manuscript was supported by NIH R01 MH122485 (HS), the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates Fellowship (SK), and Iowa Neuroscience Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship (SM), University of Iowa Environmental Health Science Research Center NIH P30 ES005605 (HS), and the University of Iowa Center for Health Effects of Environmental Contaminants (HS).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. Adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2010) 49:980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

2. Fine R, Zhang J, Stevens HE. Prenatal stress and inhibitory neuron systems: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. (2014) 19:641–51. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.35

3. Gumusoglu SB, Chilukuri ASS, Santillan DA, Santillan MK, Stevens HE. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of prenatal preeclampsia exposure. Trends Neurosci. (2020) 43:253–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.02.003

4. Gumusoglu SB, Stevens HE. Maternal inflammation and neurodevelopmental programming: a review of preclinical outcomes and implications for translational psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 85:107–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.08.008

5. Perna R, Loughan AR, Le J, Tyson K. Gestational diabetes: long-term central nervous system developmental and cognitive sequelae. Appl Neuropsychol Child. (2015) 4:217–20. doi: 10.1080/21622965.2013.874951

6. Thompson BL, Levitt P, Stanwood GD. Prenatal exposure to drugs: effects on brain development and implications for policy and education. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2009) 10:303–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn2598

7. Hsiao EY, Patterson PH. Placental regulation of maternal-fetal interactions and brain development. Dev Neurobiol. (2012) 72:1317–26. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22045

8. Young SM, Benyshek DC. In search of human placentophagy: a cross-cultural survey of human placenta consumption, disposal practices, and cultural beliefs. Ecol Food Nutr. (2010) 49:467–84. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2010.524106

9. Rosenfeld CS. Placental serotonin signaling, pregnancy outcomes, and regulation of fetal brain development. Biol Reprod. (2020) 102:532–8. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioz204

10. Cottrell EC, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult disease. Front Behav Neurosci. (2009) 3:19. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.019.2009

11. Ni Z, Mao Q. ATP-binding cassette efflux transporters in human placenta. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. (2011) 12:674–85. doi: 10.2174/138920111795164057

12. Burton GJ, Fowden AL. The placenta: a multifaceted, transient organ. Phil Trans R Soc B. (2015) 370:20140066. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0066

13. Desoye G, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. The human placenta in gestational diabetes mellitus: the insulin and cytokine network. Diabetes Care. (2007) 30(Suppl. 2):S120–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s203

14. Trophoblast Development. (2020). Available online at: https://chem.libretexts.org/@go/page/8271 (accessed January 11, 2020).

15. Cross JC, Hemberger M, Lu Y, Nozaki T, Whiteley K, Masutani M, et al. Trophoblast functions, angiogenesis and remodeling of the maternal vasculature in the placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2002) 187:207–12. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00703-1

16. Sheiner E. Gestational diabetes mellitus: long-term consequences for the mother and child grand challenge: how to move on towards secondary prevention? Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. (2020) 1:1. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3985-5

17. Castillo-Castrejon M, Powell TL. Placental nutrient transport in gestational diabetic pregnancies. Front Endocrinol. (2017) 8:306. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00306

18. Nguyen-Ngo C, Jayabalan N, Salomon C, Lappas M. Molecular pathways disrupted by gestational diabetes mellitus. J Mol Endocrinol. (2019) 63:R51–72. doi: 10.1530/JME-18-0274

19. Hauguel-de Mouzon S, Guerre-Millo M. The placenta cytokine network and inflammatory signals. Placenta. (2006) 27:794–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.08.009

20. Wu W-L, Hsiao EY, Yan Z, Mazmanian SK, Patterson PH. The placental interleukin-6 signaling controls fetal brain development and behavior. Brain Behav Immun. (2017) 62:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.11.007

21. Liong S, Oseghale O, To EE, Brassington K, Erlich JR, Luong R, et al. Influenza A virus causes maternal and fetal pathology via innate and adaptive vascular inflammation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:24964–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006905117

22. Van Campen H, Bishop JV, Abrahams VM, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Mathiason CK, Bouma GJ, et al. Maternal influenza a virus infection restricts fetal and placental growth and adversely affects the fetal thymic transcriptome. Viruses. (2020) 12:1003. doi: 10.3390/v12091003

23. Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Rooney RJ, Mori S, Kornfield TE, Reutiman TJ, et al. The viral theory of schizophrenia revisited: abnormal placental gene expression and structural changes with lack of evidence for H1N1 viral presence in placentae of infected mice or brains of exposed offspring. Neuropharmacology. (2012) 62:1290–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.011

24. Fetal alcohol syndrome–Alaska Arizona Colorado and New York 1995-1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2002) 51:433–5.

25. Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, Licht CM, Vreeburg SA, Smit JH, van den Brink W, et al. Heavy alcohol use, rather than alcohol dependence, is associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011) 116:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.006

26. Ozmen A, Unek G, Korgun ET. Effect of glucocorticoids on mechanisms of placental angiogenesis. Placenta. (2017) 52:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.02.015

27. Holbrook BD, Davies S, Cano S, Shrestha S, Jantzie LL, Rayburn WF, et al. The association between prenatal alcohol exposure and protein expression in human placenta. Birth Defects Res. (2019) 111:749–59. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1488

28. Ohira S, Motoki N, Shibazaki T, Misawa Y, Inaba Y, Kanai M, et al. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk of placental abnormality: the japan environment and children's study. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:10259. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46760-1

29. Slaoui A, Talib S, Nah A, El Moussaoui K, Benzina I, Zeraidi N, et al. Placenta accreta in the department of gynaecology and obstetrics in Rabat, Morocco: case series and review of the literature. Pan Afr Med J. (2019) 33:86. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.33.86.17700

30. Lester BM, Marsit CJ. Epigenetic mechanisms in the placenta related to infant neurodevelopment. Epigenomics. (2018) 10:321–33. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0171

31. Lager S, Powell TL. Regulation of nutrient transport across the placenta. J Pregnancy. (2012) 2012:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2012/179827

32. Lecuyer M, Laquerrière A, Bekri S, Lesueur C, Ramdani Y, Jégou S, et al. PLGF, a placental marker of fetal brain defects after in utero alcohol exposure. Acta Neuropathol Commun. (2017) 5:44. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0444-6

33. Broad KD, Keverne EB. Placental protection of the fetal brain during short-term food deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:15237–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106022108

Keywords: placenta, neurodevelopmental disorders, pregnancy, brain development, prenatal programming

Citation: Kundu S, Maurer SV and Stevens HE (2021) Future Horizons for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Placental Mechanisms. Front. Pediatr. 9:653230. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.653230

Received: 14 January 2021; Accepted: 08 March 2021;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Sara Calderoni, Fondazione Stella Maris (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

A. Gulhan Ercan-Sencicek, Masonic Medical Research Institute (MMRI), United StatesCopyright © 2021 Kundu, Maurer and Stevens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanna E. Stevens, aGFubmEtc3RldmVuc0B1aW93YS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.