94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Pediatr. , 14 February 2020

Sec. Pediatric Immunology

Volume 8 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00009

Zobaida Alsum1

Zobaida Alsum1 Mofareh S. AlZahrani2

Mofareh S. AlZahrani2 Hamoud Al-Mousa3

Hamoud Al-Mousa3 Nouf Alkhamis1

Nouf Alkhamis1 Abdulkareem A. Alsalemi4

Abdulkareem A. Alsalemi4 Hanan E. Shamseldin5

Hanan E. Shamseldin5 Fowzan S. Alkuraya5,6,7

Fowzan S. Alkuraya5,6,7 Abdullah A. Alangari8*

Abdullah A. Alangari8*Background: Inhibitor of kappa kinase 2 (IKK2) deficiency is a recently described combined immunodeficiency. It undermines the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation pathway.

Methods: The clinical and immunological data of four patients diagnosed with combined immunodeficiency (CID) from two related Saudi families were collected. Autozygosity mapping of all available members and whole exome sequencing of the index case were performed to define the genetic etiology.

Results: The patients had early onset (2–4 months of age) severe infections caused by viruses, bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi. They all had hypogammaglobulinemia and low absolute lymphocyte count. Their lymphocytes failed to respond to PHA mitogen stimulation. A novel homozygous non-sense mutation in the IKBKB gene, c.850C>T (p. Arg284*) was identified in the index patient and segregated with the disease in the rest of the family. He underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from a fully matched sibling with no conditioning. The other three patients succumbed to their disease. Interestingly, all patients had delayed umbilical cord separation.

Conclusion: IKK2 deficiency causes CID with high mortality. Immune reconstitution with HSCT should be considered as early as possible. Delayed umbilical cord separation in CID patients may be a clue to IKK2 deficiency.

Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) is a transcription factor that plays a major role in various biological processes including the immune system development, activation, and regulation. This transcription factor complex is held inactive in the cytoplasm by the inhibitor of NF-kB (IκB). The classical activation pathway of NF-kB is triggered by a large number of extracellular stimuli through different receptors, which result in the phosphorylation of IκB by IκB kinase (IKK complex; IKKα, IKKβ/IKK2, and IKKγ/NEMO) and the subsequent release of NF-kB complex so it can translocate into the nucleus and drive target gene expression (1).

Different primary immunodeficiency disorders result from genetic defects that involve components linked to the NF-kB activation pathway (2). IKK2 deficiency is a recently described combined immunodeficiency disease that leads to impairment of NF-kB signaling (3). Affected patients develop early severe and recurrent infections caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, and mycobacterial organisms. Unlike patients with IKKα and IKKγ mutations, IKK2-deficient patients do not typically have ectodermal dysplasia. Indeed, out of 22 patients with IKK2 deficiency described in the literature, only one patient has ectodermal dysplasia in the form of conical teeth (3–7).

Herein, we describe the clinical manifestations and the immunologic features of four Saudi patients from two related families with a diagnosis of combined immunodeficiency due to novel homozygous non-sense mutation in IKBKB.

The medical records of four Saudi patients from two related families with a diagnosis of combined immunodeficiency were reviewed. The clinical and immunological data were collected. Autozygosity mapping of all available members and whole exome sequencing of the index member were performed as previously described (8). Written consent was obtained from the parents. The study was approved by the Research Advisory Council at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (RAC# 2121053).

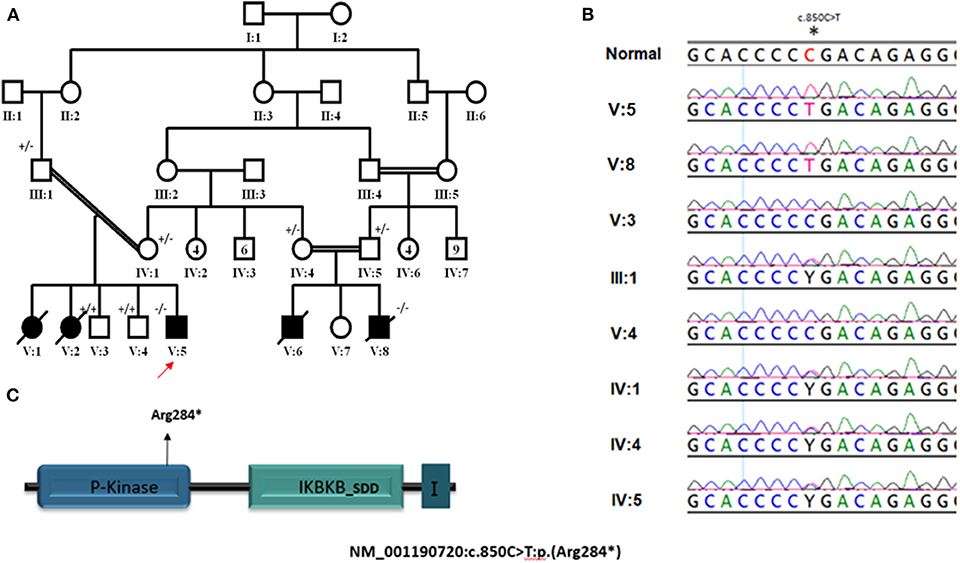

Our patients (V:1, V:2, V:5, and V:8) belong to two related Saudi families (Figure 1A). They had early onset (2–4 months of age) severe infections caused by viruses, bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi. The organisms include Klebsiella pneumonuia, Candida albicans, CMV, and BCG (Table 1), which were associated with different clinical manifestations (Table 1). Interestingly, all four patients had delayed umbilical cord separation at 2 months. They all displayed hypogammaglobulinemia. Where data is available, they had low absolute lymphocyte count (420–2,680 cells/mm3), and their lymphocytes failed to respond to PHA mitogen (Table 1). A novel homozygous non-sense mutation in the IKBKB gene, c.850C>T (p. Arg284*) (Figures 1B,C) was identified in patient V:5 within the candidate autozygome, and Sanger sequencing confirmed its segregation with the disease in the remaining living siblings and parents (Figures 1A,B). Three patients (V:1, V:2, and V:8) succumbed to their disease's infectious complications before commencing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Figure 1. (A) Pedigree of study family. ± represent segregation status of different individuals. (B) Segregation of NM_001190720: c.850C>T mutation in parents and recruited unaffected siblings. (C) Cartoons for IKBKB transcript and protein domains; arrows point to the position of mutated base. I in last protein's domain stand for I-kappa-kinase-beta NEMO binding domain. *Indicates nonsense mutation resulting in termination of translation (truncated protein).

Patient V:5 underwent HSCT from a fully matched sibling (10/10) at 19 months of age. To save his life and because of the disseminated BCGitis, he received no conditioning and no GVHD prophylaxis. The CD34 dose was 9.2 × 106/kg. He had persistent lymphoid engraftment ranging from 7 to 40% (2 weeks to 2.5 years after HSCT) but no myeloid engraftment. He developed acute gut graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) 2 months after HSCT that responded to cyclosporine A and steroid treatment. Six months later, he developed chronic gut GVHD that was controlled by the same medications. Although his lymphocyte subsets [CD3 2,409/mm3 (79%), CD4 1,211/mm3 (40%), CD8 1,183/mm3 (39%), CD19 296/mm3 (10%), CD16/56 307/mm3 (10%)] and their proliferation response to PHA (relative ratio 127%) showed good recovery, clinically, he did not show good immune reconstitution. He continued to suffer from disseminated BCGitis with bony involvement requiring frequent surgical interventions for faciozygomatic osteomyelitis. More than 4 years after the transplant, he was still on anti-mycobacterial medications (cycloserine, clarithromycin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin), monthly IVIG, and pentamidine prophylaxis. The last chimerism test was done at 4.5 years post-transplantation and showed 23% lymphoid engraftment and no myeloid engraftment. The severe disseminated BCGitis and history of GVHD precluded another trial of transplantation.

This is the largest cohort of IKK2 deficiency reported in the Saudi population. In general, the clinical features of our patients were not different from previously reported cases. Susceptibility to a wide range of infections caused by opportunistic and non-opportunistic organisms were commonality. The generalized maculopapular rash, hepatosplenomegaly, chorioretinitis, and CNS complications in our patients are probably related to the chronic CMV and disseminated BCG infections. All reported patients succumbed to their disease during infancy unless they had successful HSCT (Table 2). On average, the degree of lymphopenia was more profound in our patients (420–2,680/mm3) compared to others (1,520–11,850/mm3) (7). Interestingly, all our patients had delayed umbilical cord separation [normal separation occurs in 1–2 weeks (8)] Patient V:6, who died in infancy from a febrile illness before diagnosis and the identification of the genetic defect in the family, was also reported to have had delayed separation of the umbilical cord. None of the reported patients with IKK2 deficiency had delayed cord separation except one from Saudi Arabia, but with a different mutation (3–7). No neutrophil chemotaxis or adhesion assay was done for the patients. Delayed cord separation was reported in conditions that affect neutrophil number and/or compromise their function including leukocyte adhesion defects as well as MyD88 and IRAK4 deficiency, which are upstream to the NF-κB activation pathway (9–12). This feature may be a clue to IKK2 deficiency in patients with combined immunodeficiency. The mechanism by which IKBKB mutation may predispose to delayed cord separation is not clear. It has been reported that neutrophil infiltration was prominent during the cord separation process in healthy babies, and a defect in neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion was illustrated in cases of leukocyte adhesion deficiency (13). Since all IKK2 deficiency patients in the literature did not exhibit delayed cord separation except one Saudi patient with a different mutation, it is likely that this feature is a result of a complex interaction between the IKBKB defect and other modifier genes.

On the other hand, a gain-of-function (GOF) mutation in IKBKB leads to a relatively mild form of combined immunodeficiency, ectodermal dysplasia, and immune dysregulation, where affected patients may live to their fourth decade. Although both diseases result in hypogammaglobulinemia and lymphopenia, patients with IKBKB GOF mutation have lower number of naïve T lymphocytes with overactivated memory cells (14).

In our index patient, his unstable clinical condition and the disseminated BCGitis dictated the decision of non-conditioned HSCT. The fact that he had a sustained lymphoid engraftment without conditioning is likely due to the severe T-cell dysfunction in this type of immunodeficiency. We do not have a clear explanation why our index case did not clear the disseminated BCGitis inspite of the recovered in vitro lymphoproliferative response to PHA. One possibility is that the donor cells are anergic to BCG, but we could not test for that. So far, 13 out of 27 patients with IKK2 deficiency including our cohort had undergone HSCT. Only five were alive at the time of reporting, while those who did not receive HSCT succumbed to their disease in their infancy or early childhood. All survivors received myeloablative conditioning except our patient, while the remaining eight patients received non-myeloablative conditioning (n = 5), reduced intensity conditioning (n = 1), or no conditioning (n = 2) (14). Although it is difficult to draw a conclusion from such limited number of reported patients, it seems that no conditioning or reduced intensity conditioning are not sufficient to cure the disease, and myeloablative protocol is needed to establish a good immune reconstitution.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Research Advisory Council (RAC) at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (RAC# 2121053). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

ZA acquired data and wrote the manuscript. FA and HS designed and conducted the genetic study. HA-M contributed to writing the transplantation and post transplantation part of the manuscript. MA, NA, and AAls substantially contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the clinical data for the work. AAla acquired data, supervised, critically revised and edited the work for intellectual content. All authors provided approval for publication of the content and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research for funding the study through the research Group Project No. RGP-190.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer SP declared a past co-authorship with the author HA-M to the handling editor.

An abstract of this manuscript was presented in the European Society of Immunodeficiency (ESID) 2017 conference. They kindly granted permission to publish this manuscript.

1. Pires BRB, Silva RCMC, Ferreira GM, Abdelhay E. NF-kappaB: two sides of the same coin. Genes. (2018) 9:24. doi: 10.3390/genes9010024

2. Paciolla M, Pescatore A, Conte MI, Esposito E, Incoronato M, Lioi MB, et al. Rare mendelian primary immunodeficiency diseases associated with impaired NF-κB signaling. Genes and Immun. (2015) 16:239–46. doi: 10.1038/gene.2015.3

3. Pannicke U, Baumann B, Fuchs S, Henneke P, Rensing-Ehl A, Rizzi M, et al. Deficiency of innate and acquired immunity caused by an IKBKB mutation. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:2504–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309199

4. Burns SO, Plagnol V, Gutierrez BM, Alzahrani D, Curtis J. Immunodeficiency and disseminated mycobacterial infection associated with homozygous nonsense mutation of IKKβ. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 134:215–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1093

5. Nielsen C, Jakobsen MA, Larsen MJ, Müller AC, Hansen S, Lillevang ST, et al. Immunodeficiency associated with a nonsense mutation of IKBKB. J Clin Immunol. (2014) 34:916–21. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0097-1

6. Mousallem T, Yang J, Urban TJ, Wang H, Adeli M, Parrott RE, et al. A nonsense mutation in IKBKB causes combined immunodeficiency. Blood. (2014) 124:2046–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571265

7. Cuvelier GDE, Rubin TS, Junker A, Sinha R, Rosenburg AM, Wall DA, et al. Clinical presentation, immunologic features, and hematopoietic stem celltransplant outcomes for IKBKB immune deficiency. Clin Immunol. (2018). 205:138-147. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.10.019

8. Alkuraya FS. The application of next-generation sequencing in the autozygosity mapping of human recessive diseases. Hum Genet. (2013) 132:1197–211. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1344-x

9. Oudesluys-Murphy AM, Eilers GAM, Groot CG. The time of separation of the umbilical cord. Eur J Pediatr. (1987) 146:387–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00444944

10. Nielsen C, Agergaard CN, Jakobsen MA, Møller MB, Fisker N, Barington T. Infantile hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a case of chediak-higashi syndrome caused by a mutation in the LYST/CHS1 gene presenting with delayed umbilical cord detachment and diarrhea. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2015) 37:e73–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000300

11. Picard C, Casanova JL, Puel A. Infectious diseases in patients with IRAK-4, MyD88, NEMO, or IκBα deficiency. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2011) 24:490–7. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-11

12. Plat CD, Zaman F, Wallace JG, Seleman M, Chou J, Alsukaiti N, et al. A novel truncating mutation in MYD88 in a patient with BCG adenitis, neutropenia and delayed umbilical cord separation. Clin Immunol. (2019) 207:40–2. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2019.07.004

13. Takada H, Ishimura M, Takimoto T, Kohagura T, Yoshikawa H, Imaizumi M, et al. Invasive bacterial infection in patients with interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 deficiency. Medicine. (2016) 95:e2437. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002437

Keywords: inhibitor of kappa kinase beta/inhibitor of kappa kinase 2, IKBKB, combined immunodeficiency, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, delayed separation of the umbilical cord

Citation: Alsum Z, AlZahrani MS, Al-Mousa H, Alkhamis N, Alsalemi AA, Shamseldin HE, Alkuraya FS and Alangari AA (2020) Multiple Family Members With Delayed Cord Separtion and Combined Immunodeficiency With Novel Mutation in IKBKB. Front. Pediatr. 8:9. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00009

Received: 14 October 2019; Accepted: 09 January 2020;

Published: 14 February 2020.

Edited by:

Claudio Pignata, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyReviewed by:

Michel J. Massaad, American University of Beirut Medical Center, LebanonCopyright © 2020 Alsum, AlZahrani, Al-Mousa, Alkhamis, Alsalemi, Shamseldin, Alkuraya and Alangari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdullah A. Alangari, YWFuZ2FyaUBrc3UuZWR1LnNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.