95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Pediatr. , 12 December 2018

Sec. Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00367

This article is part of the Research Topic Pediatric Obesity: A Focus on Treatment Options View all 13 articles

Omoye E. Imoisili1,2*

Omoye E. Imoisili1,2* Alyson B. Goodman2

Alyson B. Goodman2 Carrie A. Dooyema2

Carrie A. Dooyema2 Sohyun Park2

Sohyun Park2 Megan Harrison2

Megan Harrison2 Elizabeth A. Lundeen2

Elizabeth A. Lundeen2 Heidi Blanck2

Heidi Blanck2Background: Childhood obesity care management options can be delivered in community-, clinic-, and hospital-settings. The referral practices of clinicians to these various settings have not previously been characterized beyond the local level. This study describes the management strategies and referral practices of clinicians caring for pediatric patients with obesity and associated clinician characteristics in a geographically diverse sample.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used data from the DocStyles 2017 panel-based survey of 891 clinicians who see pediatric patients. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate associations between the demographic and practice characteristics of clinicians and types of referrals for the purposes of pediatric weight management.

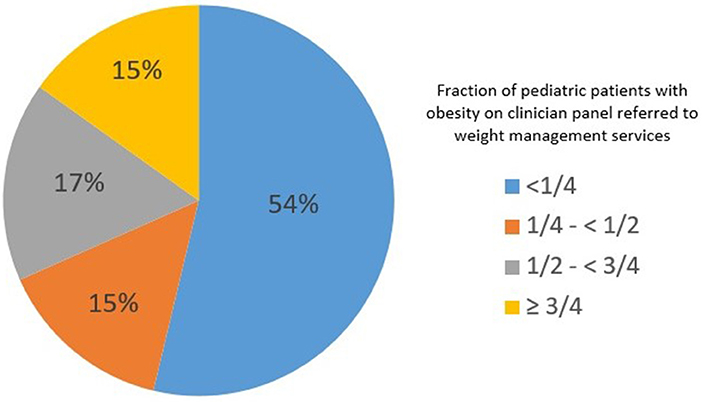

Results: About half of surveyed clinicians (54%) referred <25% of their pediatric patients with obesity for the purposes of weight management. Only 15% referred most (≥75%) of their pediatric patients with obesity for weight management. Referral types included clinical referrals, behavioral referrals, and weight management program (WMP) referrals. Within these categories, the percentage referrals ranged from 19% for behavioral/mental health professionals to 72% for registered dieticians. Among the significant associations, female clinicians had higher odds of referral to community and clinical WMP; practices in the Northeast had higher odds of referral to subspecialists, dieticians, mental health professionals, and clinical WMP; and clinics having ≥15 well child visits per week were associated with higher odds of referral to subspecialists, mental health professionals, and health educators. Not having an affiliation with teaching hospitals and serving low-income patients were associated with lower odds of referral to mental health professionals, and community and clinical WMP. Compared to pediatricians, family practitioners, internists, and nurse practitioners had higher odds of providing referrals to mental health professionals and to health educators.

Conclusion: This study helps characterize the current landscape of referral practices and management strategies of clinicians who care for pediatric patients with obesity. Our data provide insight into the clinician, clinical practice, and reported patient characteristics associated with childhood obesity referral types. Understanding referral patterns and management strategies may help improve care for children with obesity and their families.

Childhood obesity is a serious health problem associated with both physical and psychological consequences, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, asthma, weight stigma, and bullying, among others (1–6). Approximately 18.5% of children ages 2–19 in the United States have obesity (body mass index [BMI] kg/m2 ≥95th percentile for age and sex) (7), and childhood obesity tracks into adulthood (8). Among children with obesity, reductions of BMI in childhood might decrease the risk of developing insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension (9, 10), as well as have positive benefits for psychological well-being (11). To treat childhood obesity, coordinated action is needed in the places where children live, learn, and play. With 13.7 million U.S. children aged 2–19 already living with obesity (7), weight management services can help children achieve and maintain a healthy weight, and promote behavior change (12). A collective, multidisciplinary approach will likely require childhood obesity treatment and care management options delivered in community venues, clinics, and hospital-based settings, and involve different types of healthcare providers (13–16).

Clinical guidelines and recommendations exist to support childhood obesity prevention and management by healthcare providers, including the 2007 Expert Committee Recommendations Regarding the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity (17), the 2017 Screening for Obesity in Children and Adolescents United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement (18), and the 2017 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on Pediatric Obesity—Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention (19). Commonalities of these recommendations are that children be screened for obesity using BMI, and that children with obesity be referred to programs or services for the purpose of weight management. The Expert Committee recommendations promote staged prevention and treatment pathways, and the Endocrine Society also delineates clinical steps for management, whereas the USPSTF provides sufficient evidence to recommend children with obesity be referred to comprehensive behavioral interventions with moderate to high intensity, in order to promote a healthy weight status.

The implementation of these recommendations in practice likely vary, depending on factors, such as patient sociodemographics, intervention setting, payer type, and other key factors (13, 20–24). For example, referrals for pediatric weight management may include primary care providers, subspecialty providers, registered dietitians, physical or exercise therapists, health educators, behavioral counselors, mental health professionals, comprehensive, multidisciplinary pediatric weight management programs, and others. Such professionals are recognized as potential healthcare providers for children with obesity in the aforementioned recommendations. Children might also be referred to clinical subspecialists for management of comorbidities associated with obesity (25), such as those requiring management by endocrinologists or gastroenterologists due to comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or gastroesophageal reflux disease (19, 26). Due to a lack of data beyond the local level, the current landscape of referral practices and management strategies for childhood obesity in the United States is not well understood. Exploring data that have more geographic diversity may be helpful in understanding the uptake of evidence-based practices regarding the management of childhood obesity across the nation. This paper aims to describe the management strategies and referral practices of clinicians who care for pediatric patients with obesity. We also explore clinician characteristics associated with these referrals.

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2017 DocStyles survey, a web-based panel survey of U.S. clinicians designed to further understand healthcare provider practices. DocStyles survey is administered by Porter Novelli Public Services, a public relations and social marketing firm.

Respondents were sampled from the SERMO Global Medical Panel—a global market research provider (27). From the SERMO panel, which included 51,000 primary care providers (PCPs, including internists), 12,700 Pediatricians, and 2,400 Nurse Practitioners, Porter Novelli set sample size quotas that included 1,000 primary care physicians (including family practitioners and internists), 250 pediatricians, 250 obstetrician/gynecologists, 250 nurse practitioners, 250 oncologists, 150 retail pharmacists, and 100 hospital pharmacists. When comparing physician respondents from DocStyles survey 2017 to physicians in the American Medical Association Physician Master File, survey respondents were more male (69.6 vs. 58.0%), slightly older (48.1 vs. 47.0 years), and practiced for a shorter duration (17.6 vs. 19.3 years). From June 8th to August 9th, 2017, responses were obtained (28). Panelists were verified via a double opt-in sign up process with telephone confirmation at their place of work. An honorarium of $23–$85 was paid to respondents for completing the survey, and was determined by the number of questions they were asked to complete.

Eligibility criteria for DocStyles survey 2017 included clinicians within the United States who have actively seen patients for at least 3 years in an individual, group, or hospital practice. There were 2,260 clinicians who completed the survey (Figure 1). For this particular analysis, questions were only asked of pediatricians, internists, family practitioners and nurse practitioners (n = 1,509). Furthermore, use of skip patterns narrowed the respondents to clinicians who reported caring for pediatric patients (age ≤ 17 years; n = 1,023). The final analytic sample consisted of 891 respondents, as 132 clinicians (12.9%) had missing data on referral to weight management programs for childhood obesity. These clinicians who were excluded from this study due to missing data did not differ by demographics, but differed by specialty [higher proportion of internists (27 vs. 13%) and nurse practitioners (27 vs. 15%)] and work setting [higher proportion of inpatient clinicians (23 vs. 5%)]. The CDC licensed the results of the DocStyles 2017 survey post-collection from Porter Novelli. Since personal identifiers were not included in the data files, IRB approval was not needed for this project because CDC was not engaged in human subjects research.

The primary outcomes for this analysis were clinician referrals to clinical specialists, behavioral specialists, and Weight Management Programs. The questions to clinicians were presented as follows: “The next few questions are about your referral practices for children with obesity (i.e., BMI ≥95th percentile). Among your patients aged 6–18 years with obesity, approximately what percentage do you refer to services or programs for the purpose of weight management?” Respondents provided a numeric value from 0 to 100. Subsequently, clinicians were asked: “What action(s) do you typically take for children with obesity (i.e., BMI ≥95th percentile) for the purpose of weight management?” Respondents could select all relevant options, which were not mutually exclusive. Response choices included: (1) Schedule a follow-up visit for obesity, or referral to (2) a subspecialty, such as endocrinology or gastroenterology; (3) a registered dietitian; (4) a behavioral/mental health profession; (5) a health educator/coach (6) a community-based weight management program/organization (e.g., YMCA, Weight Watchers); and (7) a clinic- or hospital-based weight management program/organization. Based on the response options, the main outcome variables for the analysis were the percentage of patients with obesity referred for services, and the types of referrals that clinicians typically made for children with obesity. Scheduling for a follow-up visit was considered a management strategy, while the other options were considered to be referrals.

Covariates for these analyses were grouped into clinician, clinical practice, and reported patient characteristics. Clinician characteristics included clinician age (<45 or ≥45 years), gender (male and female), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Asian, and other). Age categories were determined by prior studies (29, 30) and respondent distribution. Clinical practice characteristics were comprised of practice location Census region (Northeast, South, Midwest, West), medical specialty (family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, nurse practitioner), primary work setting (inpatient, individual outpatient, or group outpatient), teaching hospital privileges (yes or no), and number of well-child visits per week (<5, 5–14, or ≥15 visits, reported as a continuous variable, and categories were determined by distribution of the data). Clinicians reported on two characteristics of their patient population: income and weight status. They were asked to select the income category that best described the approximate household income of the majority of their patients. These responses were subsequently grouped into three categories based on distribution of the sample, and included low-income (<$50,000), middle-income ($50,000– <$100,000), and high-income (≥$100,000). Respondents also reported what percentage of their pediatric patients had obesity; these were categorized as <10, 10– <20, 20– <40, and ≥40% based on the data distribution.

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used to perform statistical analyses. Crude associations between reported referral and personal, clinical practice, and patient characteristics were assessed by chi-squared tests; the criterion for statistical significance was p < 0.05. A multivariable logistic regression model estimated the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for characteristics associated with referral. All covariates (i.e., clinician, clinical practice, and reported patient characteristics) were included in one model after a diagnostic assessment did not reveal significant collinearity between variables.

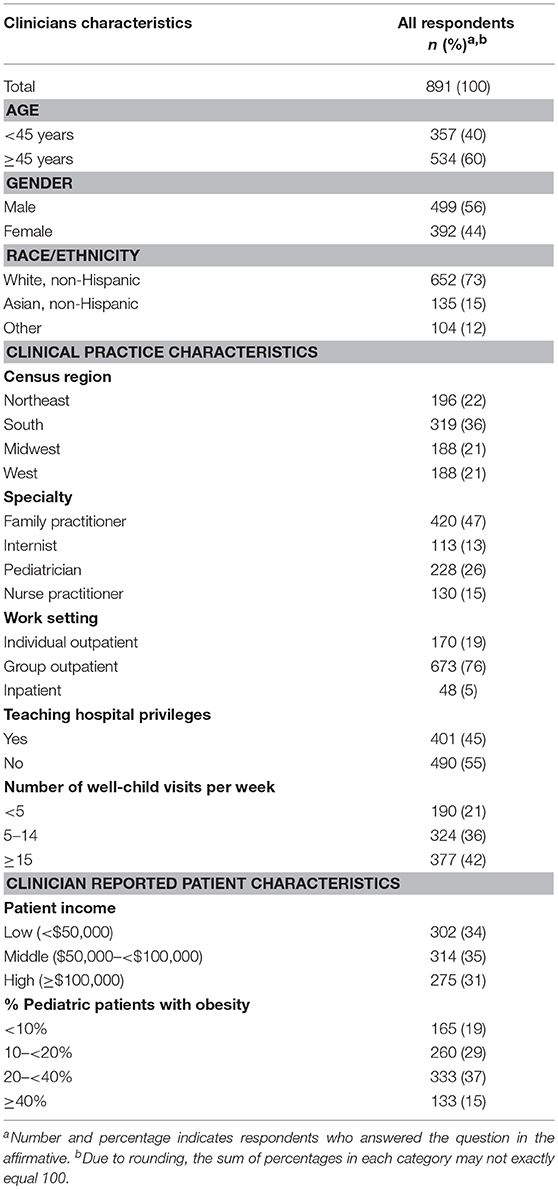

Table 1 shows the clinician, clinical practice, and patient characteristics of the 891 clinicians in the analytic sample. The majority of respondent clinicians were white non-Hispanic (73%) and worked in a group outpatient setting (76%). Just over half of clinicians (54%) reported referring less than a quarter of their pediatric patients with obesity for the purposes of weight management (Figure 2). Additionally, 15% reported referring 25– <50% of their pediatric patients with obesity, and 17% referred 50– <75% of their pediatric patients. Only 15% referred ≥75% of their pediatric patients with obesity for weight management.

Table 1. Characteristics of clinicians who see children, clinical practice, and patients, DocStyles survey 2017 (N = 891).

Figure 2. Percentage of clinicians who refer pediatric patients with obesity for weight management services, DocStyles survey 2017 (N = 891).

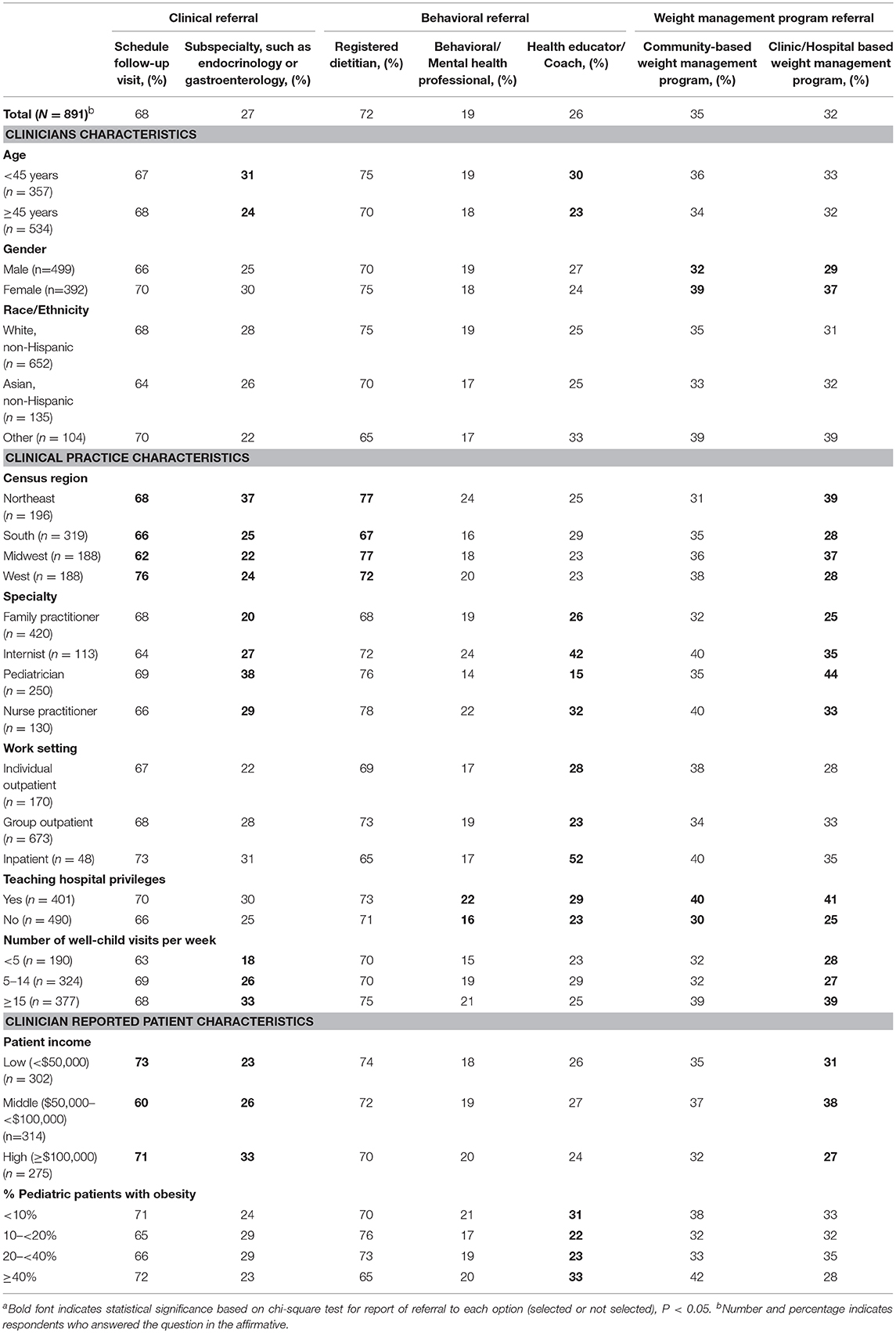

Over two-thirds of clinicians (68%) scheduled pediatric patients for follow-up visits (Table 2). The most common clinical referral reported was to a registered dietitian (72%), followed by referral to a subspecialist (27%). The most common behavioral health referral was to a health educator/coach (26%) followed by behavioral/mental health professional (19%). Finally, approximately one-third of clinicians referred their pediatric patients with obesity to weight management programs, whether community-based (35%) or hospital/clinic-based (32%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of clinicians, clinical practice, and patients associated with referral practices, DocStyles survey 2017 (N = 891)a.

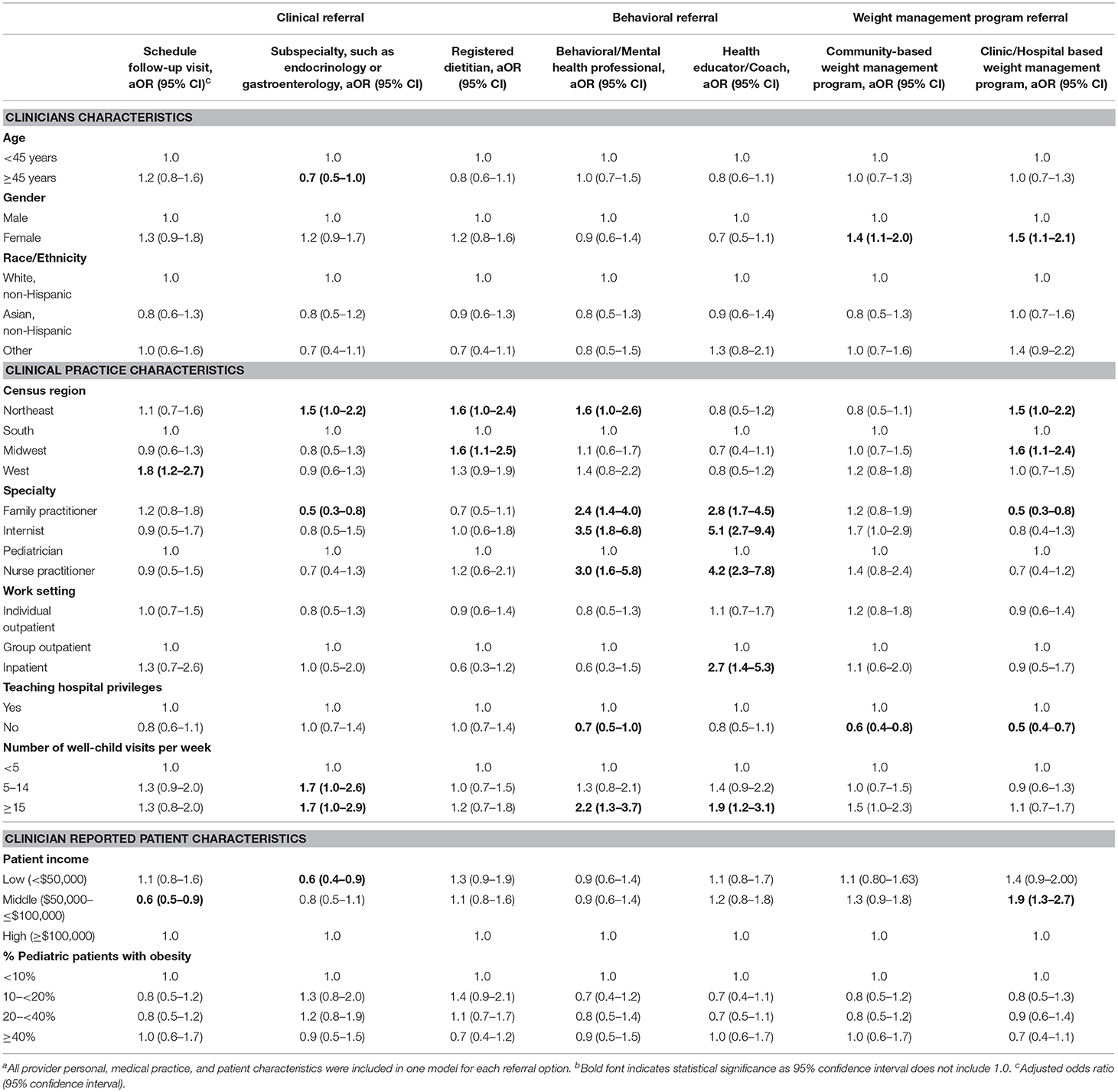

When we examined clinician characteristics, odds of clinical referrals to subspecialists were lower among clinicians ≥45 years of age (aOR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.5–1.0) compared to clinicians < 45 years (Table 3). Female clinicians had higher odds of referral to both community- and clinic/hospital-based weight management programs (aOR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.0–2.0, and aOR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.1–2.1, respectively).

Table 3. Adjusted Odds Ratiosa of pediatric obesity referral practices by characteristics of clinicians, clinical practice, and patients, DocStyles survey 2017 (N = 891)b.

Among the clinical practice characteristics, we found significant differences in referral practices by Census region and clinical subspecialty. Clinicians based in the West had higher adjusted odds of scheduling a follow-up visit vs. clinicians in the South (aOR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.2–2.7). Odds of a clinical referral to a dietitian were higher in the Northeast and the Midwest vs. the South (aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.0–2.4; aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.1–2.5, respectively). Odds of referrals to a behavioral/mental health professional were higher in the Northeast compared to the South (aOR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.0–2.6). Odds of referral to a hospital or clinic based weight management program were higher in in the Northeast and the Midwest vs. the South (aOR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.0–2.2 and aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.1–2.4, respectively). Clinical practice specialty was also associated with clinical referrals; family practitioners were less likely to refer to subspecialists compared to pediatricians (aOR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.3–0.8). For behavioral referrals, all other specialties (family practitioners, internists, and nurse practitioners) had significantly higher odds of referrals to mental health professionals (aOR range: 2.4–3.5) or health educators (aOR range: 2.8–5.1) compared to pediatricians. Clinicians who primarily work in inpatient settings had higher odds of referral to health educators/coaches (aOR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.4–5.3) compared to clinicians in group outpatient settings. Clinicians without teaching hospital privileges had lower odds of referring to a mental health professional (aOR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.5–1.00) vs. clinicians with privileges. Finally, clinicians in practices that perform ≥5 well child visits per week had significantly higher odds of referral to subspecialists compared to those in practices that perform less than five per week (aOR: 1.7). Additionally, clinicians in practices that perform ≥15 well child visits per week had approximately twice the odds of a behavioral health referral (aOR range: 1.9–2.2) compared to those in practices that performed less than five per week.

Referral patterns also differed by clinician reported patient characteristics. When compared with clinicians serving high-income patient populations, clinicians serving low-income patient populations had lower odds of referral to a subspecialist (aOR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.4–0.9). In addition, clinicians serving patients with middle-income populations had lower odds of scheduling a follow-up visit (aOR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.5–0.9), but had higher odds of referral to a clinic/hospital-based weight management program (aOR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.3–2.7). Odds of specific types of referrals did not differ based on the estimated percentage of children in the clinician's practice who had obesity.

Overall, about two-thirds of clinicians in this study reported scheduling patients for follow-up appointments as a management strategy for pediatric obesity. Approximately half of respondents reported referring less than one-quarter of their pediatric patients with obesity to services or programs for the purposes of weight management, and only 15% reported referring most (≥75%) of their pediatric patients with obesity.

The most common referral made among survey respondents was to registered dietitians, with almost three-quarters of clinicians reporting referral of children with obesity to this profession. Dietitians are specifically trained in nutrition and can be key members of multidisciplinary obesity management teams. A recent review found that for adults with type 2 diabetes, individual nutrition therapy conducted by dietitians resulted in better health outcomes, including a lower BMI, than care by other providers, such as physicians and nurses (31).

Approximately one-quarter of respondents reported referral to clinical subspecialists; similarly about one-quarter of surveyed clinicians also reported referral to health educators/coaches. However, we found that less than one in five reported referring pediatric patients with obesity to behavioral/mental health professionals. About one-third of clinicians referred pediatric patients with obesity to either a community-based or a clinic/hospital-based weight management programs. All of the aforementioned referral practices are potential referral options presented within the Expert Committee and USPSTF recommendations for childhood obesity. This study is the first to examine the frequency with which these referrals are made using data beyond one geographic location within the country. We also found that these referral practices differed based on clinician, clinical practice, and reported patient characteristics.

Older clinicians had lower odds of subspecialty referral compared to younger physicians in our study. A previous study of referral practices among primary care physicians found that years in practice, which likely correlates with physician age, was associated with lower subspecialist referral (32). Female clinicians in this study had higher odds of referral to both types of weight management programs. Women have been shown to be more likely to engage in preventive care, and more likely to make referrals to weight loss programs for adult patients with obesity to weight loss programs (33, 34). Our results are consistent with these findings, but demonstrated this association within a pediatric patient population with obesity.

Respondents in the Northeast had higher odds of referrals to subspecialties, registered dietitians, behavioral/mental health professionals, and clinic/hospital-based weight management programs vs. those in the South. The Northeast region generally has a higher concentration of urban areas compared to other regions in the United States (35). Therefore, within this region resources for patients with obesity might be more attainable, with fewer geographic barriers, such as distance prohibiting access to weight management programs (36). Professionals, such as dietitians are more concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest (37). These factors could possibly contribute to the higher odds of referral to dietitians and clinic based weight management programs in the Midwest vs. the South.

Clinician specialty was also associated with some referrals, with all surveyed non-pediatric specialties having higher odds of behavioral referrals for childhood obesity, compared to pediatricians. Pediatricians are trained specifically to care for children and might have been taught about pediatric weight management while in training (38, 39). While self-efficacy for weight management holds value, evidence suggests non-traditional healthcare providers, such as health coaches (40) might be beneficial in pediatric weight management. In addition, inter-professional collaborations (i.e., between dietitians, exercise therapists, and others) are beneficial for childhood obesity management (17, 23). Family practitioners had lower odds of referral to clinical subspecialists, and to clinic/hospital-based weight management programs, compared to pediatricians. This is consistent with a prior study that also documented significant differences between the approaches of family practitioners and pediatricians in the treatment of children, with family physicians in that study having significantly lower odds of referral of pediatric patients for further evaluation and management for weight related care (41).

Work setting and teaching hospital privileges were also associated with respondents' likelihood of behavioral referrals. Clinicians who practice inpatient had higher odds of referring to a health educator/coach in our study. These clinicians might be able to take advantage of inpatient health educators during patient admissions (42). Respondents without teaching hospital privileges had lower odds of referral to a behavioral/mental health professional and to clinic/hospital based weight management programs in the present study. It is possible that privileges with a teaching hospital could mean belonging to a referral network that facilitates patient access to such resources. For instance, a higher percentage of teaching hospitals offer psychiatric outpatient services compared to non-teaching hospitals (43).

In our study, the number of well-child visits per week per practice was associated with increased odds of referrals to clinical subspecialties and behavioral referrals. A greater number of well child visits per week might be indicative of a larger or more pediatric focused practice. In a study among primarily family practitioners, clinicians in solo or small group practice were less likely to make referrals compared to physicians in larger practices (32). Having larger patient volumes might mean less time per patient (44), and potentially more referrals.

In the present study, clinicians working with middle-income patients were less likely to schedule patients for a follow-up visit; however, they also had higher odds of referring their patients externally to clinic/hospital-based weight management programs. A previous study demonstrated that attending a pediatric weight management program after referral is associated with socioeconomic status and insurance status (45). However, data have not formally shown whether perceived likelihood of patient attendance affects clinician odds of referral. In addition, clinicians who reported caring for low-income patients had a lower odds of referrals to clinical subspecialists. It might be more difficult for patients with lower incomes to find subspecialists who will take their insurance, such as Medicaid (46–48).

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the DocStyles survey is a panel survey based on quota sampling, resulting in a sample that is not necessarily representative of the population, and thus the findings might not be generalizable to clinicians nationwide. In addition, survey respondents may differ compared to those who did not participate in the survey. However, this study uses a sample with more geographic diversity than previous samples rather than a limited local sample. Second, DocStyles data are based on the report of clinicians both about their personal practices and perceptions about their patient population; no objective measures were obtained. Thus, their responses are subject to reporting biases. Nevertheless, querying clinicians directly can provide insight into what influences their referral practices. Finally, the possibility exists that there are factors that confound or modify the association between clinician, clinical practice, or clinician reported patient characteristics and referral type that might not have been accounted for; for example, location in an urban or rural environment. Despite these limitations, this study adds valuable information to the literature by describing current practice and characteristics that may influence childhood obesity referral practices of clinicians in the United States.

In this study, clinicians caring for children with obesity referred patients to a wide range of providers and services for the purposes of weight management; although half of clinicians referred less than one-quarter of their pediatric patients with obesity for these interventions. Most respondents referred pediatric patients with obesity to dietitians, and the majority scheduled follow-up appointments, which is a recommended practice. Clinicians also referred to clinic-based weight management programs, clinical subspecialists, health educators, and behavioral/mental health professionals with varying frequencies, ranging from 19% for behavioral/mental health professionals to 72% for registered dieticians. Referrals were generally consistent with recommendations from the AAP or USPSTF to address the complex nature of childhood obesity management. Our findings contribute to understanding the current landscape of referral practices and management strategies of clinicians who care for pediatric patients with obesity. Our data also provide insight into the clinician, clinical practice, and reported patient characteristics associated with childhood obesity referral types. Understanding referral patterns and management strategies can help inform strategies to improve the uptake of current recommended care.

OI, AG, CD, SP, MH, EL, and HB wrote and contributed in the preparation of this manuscript. AG, CD, MH, and HB formulated research questions explored in this study, and contributed subject matter expertise. OI, SP, and EL engaged in statistical analysis of the survey data.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are appreciative for the contributions of Dr. Brook Belay toward the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Akinbami LJ, Rossen LM, Fakhouri THI, Fryar CD. Asthma prevalence trends by weight status among US children aged 2–19 years, 1988–2014. Pediatr Obes. (2017) 13:393–6. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12246

2. Bocca G, Ongering EC, Stolk RP, Sauer PJJ. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors in 3- to 5-year-old overweight or obese children. Horm Res Paediatr. (2013) 80:201–6. doi: 10.1159/000354662

3. Mazor-Aronovitch K, Lotan D, Modan-Moses D, Fradkin A, Pinhas-Hamiel O. Blood pressure in obese and overweight children and adolescents. Isr Med Assoc J. (2014) 16:157–61.

4. Pont SJ, Puhl R, Cook SR, Slusser W, Section on Obesity, Obesity Society. Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics (2017) 140:e20173034. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3034

5. Sikorski C, Luppa M, Luck T, Riedel-Heller SG. Weight stigma “gets under the skin”-evidence for an adapted psychological mediation framework: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring) (2015) 23:266–76. doi: 10.1002/oby.20952

6. Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Moss LA, Skelton JA. Cardiometabolic risks and severity of obesity in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. (2015) 373:1307–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502821

7. Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007–2008 to 2015–2016. JAMA (2018) 319:1723–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060

8. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2016) 17:95–107. doi: 10.1111/obr.12334

9. Kirk S, Zeller M, Claytor R, Santangelo M, Khoury PR, Daniels SR. The relationship of health outcomes to improvement in BMI in children and adolescents. Obes Res. (2005) 13:876–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.101

10. O'Connor EA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Walsh ES, Eder M, Lozano P. Screening for obesity and intervention for weight management in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA (2017) 317:2427–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0332

11. Lloyd-Richardson EE, Jelalian E, Sato AF, Hart CN, Mehlenbeck R, Wing RR. Two-year follow-up of an adolescent behavioral weight control intervention. Pediatrics (2012) 130:e281–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3283

12. Wilfley DE, Staiano AE, Altman M, Lindros J, Lima A, Hassink SG, et al. Improving access and systems of care for evidence-based childhood obesity treatment: conference key findings and next steps. Obesity (Silver Spring) (2017) 25:16–29. doi: 10.1002/oby.21712

13. Brown CL, Perrin EM. Obesity prevention and treatment in primary care. Acad Pediatr. (2018) 18:736–45. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.05.004

14. Katzmarzyk PT, Barlow S, Bouchard C, Catalano PM, Hsia DS, Inge TH, et al. An evolving scientific basis for the prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). (2014) 38:887–905. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.49

15. Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O, et al. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2015) 16:547–65. doi: 10.1111/obr.12277

16. Wu Y, Lau BD, Bleich S, Cheskin L, Boult C, Segal JB, et al. AHRQ future research needs papers. In: Future Research Needs for Childhood Obesity Prevention Programs: Identification of Future Research Needs From Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 115. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) (2013).

17. Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics (2007) 120 Suppl. 4:S164–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C

18. Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA (2017) 317:2417–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6803

19. Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, et al. Pediatric obesity-assessment, treatment, and prevention: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2017) 102:709–57. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2573

20. Bhuyan SS, Chandak A, Smith P, Carlton EL, Duncan K, Gentry D. Integration of public health and primary care: a systematic review of the current literature in primary care physician mediated childhood obesity interventions. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2015) 9:539–52. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.07.005

21. Lederer AM, King MH, Sovinski D, Seo DC, Kim N. The relationship between school-level characteristics and implementation fidelity of a coordinated school health childhood obesity prevention intervention. J Sch Health (2015) 85:8–16. doi: 10.1111/josh.12221

22. Simpson LA, Cooper J. Paying for obesity: a changing landscape. Pediatrics (2009) 123 Suppl. 5:S301–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2780I

23. Rhee KE, Kessl S, Lindback S, Littman M, El-Kareh RE. Provider views on childhood obesity management in primary care settings: a mixed methods analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:55. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2870-y

24. Rausch JC, Perito ER, Hametz P. Obesity prevention, screening, and treatment: practices of pediatric providers since the 2007 expert committee recommendations. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2011) 50:434–41. doi: 10.1177/0009922810394833

25. Estrada E, Eneli I, Hampl S, Mietus-Snyder M, Mirza N, Rhodes E, et al. Children's Hospital Association consensus statements for comorbidities of childhood obesity. Child Obes. (2014) 10:304–17. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0120

26. Huang JS, Barlow SE, Quiros-Tejeira RE, Scheimann A, Skelton J, Suskind D, et al. Childhood obesity for pediatric gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2013) 56:99–109. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826d3c62

27. SERMO. What is SERMO? (2018). Available online at: http://www.sermo.com/what-is-sermo/overview

28. Porter Novelli Public Services. DocStyles 2017 Methodology. Washington, DC: Deanne Weber (2017).

29. VanFrank BK, Park S, Foltz JL, McGuire LC, Harris DM. Physician characteristics associated with sugar-sweetened beverage counseling practices. Am J Health Promot. (2016) 32:1365–74. doi: 10.1177/0890117116680472

30. Quader ZS, Cogswell ME, Fang J, Coleman King SM, Merritt RK. Changes in primary healthcare providers' attitudes and counseling behaviors related to dietary sodium reduction, DocStyles 2010 and 2015. PLoS ONE (2017) 12:e0177693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177693

31. Moller G, Andersen HK, Snorgaard O. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nutrition therapy compared with dietary advice in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. (2017) 106:1394–400. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.139626

32. Forrest CB, Nutting PA, von Schrader S, Rohde C, Starfield B. Primary care physician specialty referral decision making: patient, physician, and health care system determinants. Med Decis Making (2006) 26:76–85. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05284110

33. Henderson JT, Weisman CS. Physician gender effects on preventive screening and counseling: an analysis of male and female patients' health care experiences. Med Care (2001) 39:1281–92.

34. Dutton GR, Herman KG, Tan F, Goble M, Dancer-Brown M, Van Vessem N, et al. Patient and physician characteristics associated with the provision of weight loss counseling in primary care. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2014) 8:e123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2012.12.004

35. Bureau USC. Metropolitan Micropolitan Areas of the United States Puerto Rico. (2009). Available online at: https://www2.census.gov/geo/maps/metroarea/us_wall/Dec_2009/cbsa_us_1209_large.gif

36. Ambler KA, Hagedorn DW, Ball GD. Referrals for pediatric weight management: the importance of proximity. BMC Health Serv Res. (2010) 10:302. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-302

37. Bureau of Labor Statistics USDoL. 29-1031 Dietitians and Nutritionists. Occupational Employment and Wage (2017). Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291031.htm

38. Jacobson D, Gance-Cleveland B. A systematic review of primary healthcare provider education and training using the Chronic Care Model for childhood obesity. Obes Rev. (2011) 12:e244–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00789.x

39. Perrin EM, Vann JC, Lazorick S, Ammerman A, Teplin S, Flower K, et al. Bolstering confidence in obesity prevention and treatment counseling for resident and community pediatricians. Patient Educ Couns. (2008) 73:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.025

40. Rice KG, Jumamil RB, Jabour SM, Cheng JK. Role of health coaches in pediatric weight management. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2017) 56:162–70. doi: 10.1177/0009922816645515

41. Huang TT, Borowski LA, Liu B, Galuska DA, Ballard-Barbash R, Yanovski SZ, et al. Pediatricians' and family physicians' weight-related care of children in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. (2011) 41:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.01

42. Bureau of Labor Statistics USDoL. Health Educators and Community Health Workers. Occupational Outlook Handbook (2016). Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/OOH/community-and-social-service/health-educators.htm#tab-3

43. Grover A, Slavin PL, Willson P. The economics of academic medical centers. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370:2360–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1403609

44. Kikano GE, Zyzanski SJ, Gotler RS, Stange KC. High-volume practice: are there trade-offs? Fam Pract Manag. (2000) 7:63–4.

45. Shaffer LA, Brothers KB, Burkhead TA, Yeager R, Myers JA, Sweeney B. Factors associated with attendance after referral to a pediatric weight management program. J Pediatr. (2016) 172:35–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.011

46. Cook NL, Hicks LS, O'Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood) (2007) 26:1459–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459

47. Forrest CB, Shadmi E, Nutting PA, Starfield B. Specialty referral completion among primary care patients: results from the ASPN Referral Study. Ann Fam Med. (2007) 5:361–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.703

48. Office USGA. Most Physicians Serve Covered Children but Have Difficulty Referring Them for Specialty Care. Medicaid CHIP (2011). Available online at: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-11-624

Keywords: pediatric obesity, obesity management, weight management programs, clinician referrals, clinician characteristics

Citation: Imoisili OE, Goodman AB, Dooyema CA, Park S, Harrison M, Lundeen EA and Blanck H (2018) Referrals and Management Strategies for Pediatric Obesity—DocStyles Survey 2017. Front. Pediatr. 6:367. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00367

Received: 06 September 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018;

Published: 12 December 2018.

Edited by:

Fatima Cody Stanford, Harvard Medical School, United StatesReviewed by:

Hellas Cena, University of Pavia, ItalyCopyright © 2018 Imoisili, Goodman, Dooyema, Park, Harrison, Lundeen and Blanck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Omoye E. Imoisili, b2ltb2lzaWxpQGNkYy5nb3Y=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.