- 1Neuromodulation Center and Center for Clinical Research Learning, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, Unidad de Investigación para la Generación y Síntesis de Evidencias en Salud, Lima, Peru

- 3Instituto de Ciencias Biologicas, Departamento de Imunologia Basica e Aplicada, Manaus, Brazil

- 4MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, MA, United States

- 5Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 6Pain and Palliative Care Service at Clinical Hospital of Porto Alegre (HCPA), Surgery Department, Federal University of Rio Grande Do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Introduction: Fibromyalgia (FM) is associated with dysfunctional pain modulation mechanisms, including central sensitization. Experimental pain measurements, such as temporal summation (TS), could serve as markers of central sensitization and have been previously studied in these patients, with conflicting results. Our objective in this study was to explore the relationships between two different protocols of TS (phasic and tonic) and test the associations between these measures and other clinical variables.

Materials and Methods: In this cross-sectional analysis of a randomized clinical trial, patients were instructed to determine their pain-60 test temperature, then received one train of 15 repetitive heat stimuli and rated their pain after the 1st and 15th stimuli: TSPS-phasic was calculated as the difference between those. We also administered a tonic heat test stimulus at the same temperature continuously for 30 s and asked them to rate their pain levels after 10 s and 30 s, calculating TSPS-tonic as the difference between them. We also collected baseline demographic data and behavioral questionnaires assessing pain, depression, fatigue, anxiety, sleepiness, and quality of life. We performed univariable analyses of the relationship between TSPS-phasic and TSPS-tonic, and between each of those measures and the demographic and clinical variables collected at baseline. We then built multivariable linear regression models to find predictors for TSPS-phasic and TSPS-tonic, while including potential confounders and avoiding collinearity.

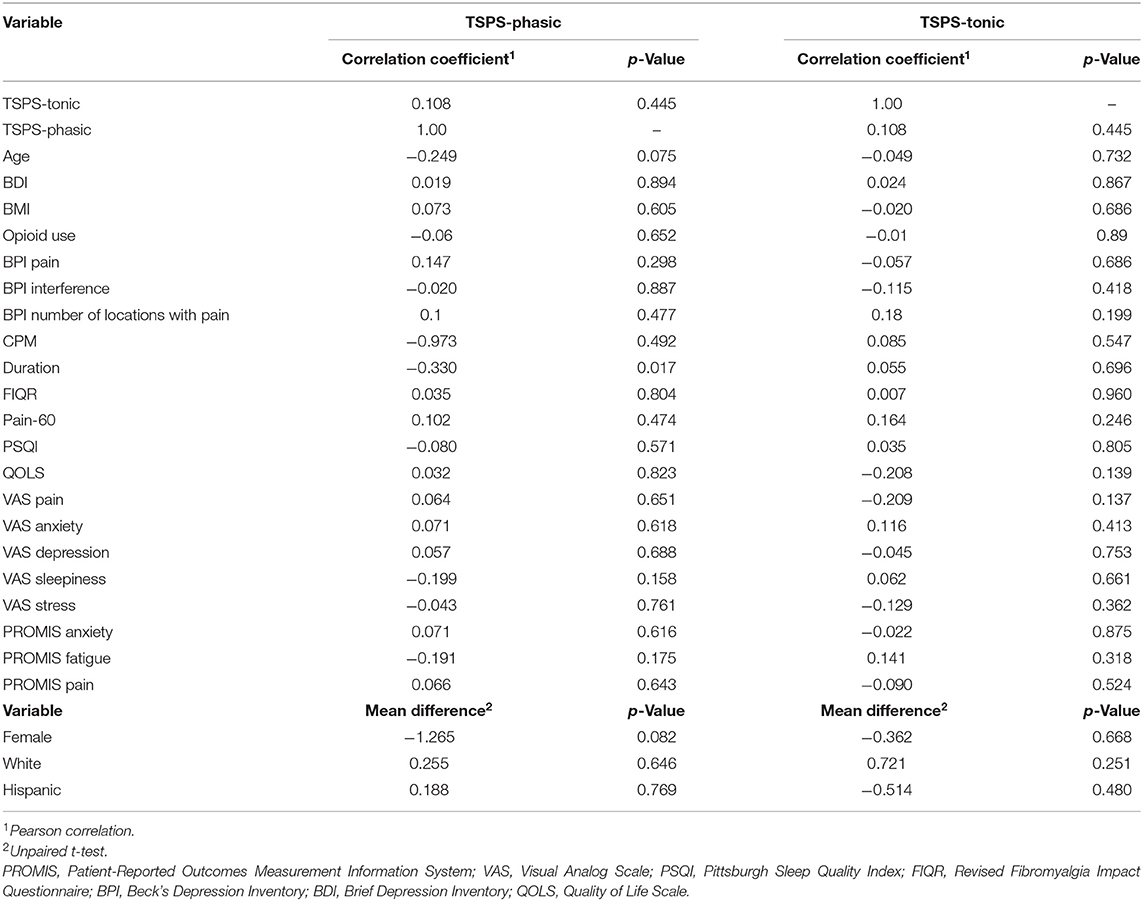

Results: Fifty-two FM patients were analyzed. 28.85% developed summation during the TSPS-phasic protocol while 21.15% developed summation during the TSPS-tonic protocol. There were no variables associated TSPS phasic or tonic in the univariable analyses and both measures were not correlated. On the multivariate model for the TSPS-phasic protocol, we found a weak association with pain variables. BPI-pain subscale was associated with more temporal summation in the phasic protocol (ß = 0.38, p = 0.029), while VAS for pain was associated with less summation in the TSPS-tonic protocol (ß = −0.5, p = 0.009).

Conclusion: Our results suggest that, using heat stimuli with pain-60 temperatures, a TSPS-phasic protocol and a TSPS-tonic protocol are not correlated and could index different neural responses in FM subjects. Further studies with larger sample sizes would be needed to elucidate whether such responses could help differentiating subjects with FM into specific phenotypes.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a chronic disease characterized by generalized musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and cognitive symptoms (1). Despite an unknown etiology (2), research has shown evidence of central nervous system (CNS) involvement, supporting central sensitization and a defective endogenous pain modulation (3, 4). Experimental pai n measurements, such as temporal summation (TS) or Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM), could contribute to further understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease and its connection to the CNS.

Conditioned Pain Modulation, which is based on the “pain inhibits pain” paradigm (5), consists of the application of two noxious stimuli, and the inhibition of pain from the first noxious stimuli by the second stimuli applied in a different area of the body. CPM measures would thus represent the activity of descending inhibitory pathways.

Temporal summation, on the other hand, is believed to be related to endogenous excitatory pain mechanisms and it consists of repeated or continuous administration of noxious stimuli resulting in the amplification of pain perception despite the same intensity of the stimuli (5, 6). Central sensitization is an abnormal state of increased responsiveness of the spinal and supraspinal neurons leading to low-threshold hypersensitivity (7). It may occur in different areas of the nervous system such as the dorsal horn neurons, which are a crucial part of the pain pathways, after repeated tonic stimulation of C-fibers. This stimulus eventually leads to short- and long-lasting impulse discharges in a wide dynamic range and also in the dorsal horn neurons that increase the excitability of the nociceptive system and enhance the sensation of a second pain stimulus (7, 8), this is known as “wind-up” (8). TS is a method that resembles the “wind up” process by applying a painful frequency (>3 Hz) and stimulating the unmyelinated C fibers (3, 9), and provides information regarding the low pain threshold in fibromyalgia patients and its connection to the CNS (8). TS, therefore, is believed to act as a marker of central sensitization mechanisms.

Temporal summation protocols can be elicited through continuous (tonic), or repetitive (phasic) painful stimuli (10). The evidence regarding the agreement of these two different types of stimuli in individuals with fibromyalgia is scarce, with only a few randomized controlled trials available (10–12). Moreover, the results of these RCTs are conflicting and do not completely identify the TS profile of these individuals (10, 12). It is particularly important to identify which TS paradigms better contribute to the understanding of the central mechanisms behind fibromyalgia pain, considering how important these CNS modulation systems impact the pain felt by fibromyalgia patients (11). Moreover, TS can be evoked by different mechanical, heat, or electrical stimuli (13). Thus, several stimuli can be used in TS protocols to test said phenomenon, creating heterogeneous methodologies of application (14–17). This methodological variety regarding the type of stimuli, number of pulses, and duration can yield distinct results and lead to ambiguous conclusions regarding the TS phenomenon in individuals with chronic pain, especially fibromyalgia (3). A recent, inconclusive systematic review on TS as an endogenous pain modulation marker in individuals with fibromyalgia, attributed its inconclusive results to the flexible and heterogeneous protocols present in the fibromyalgia studies (3). Therefore, this variability in the methodology supports the need for standardized processes to measure TS in chronic pain conditions.

In this study we collected baseline data from fibromyalgia patients including experimental pain measurements including two paradigms of temporal summation: phasic and tonic. In this study, we aimed to explore (i) the relationships between the two protocols of Temporal Summation measures (phasic and tonic) collected and (ii) the associations between these measures and the other clinical variables collected at baseline.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

This study is a cross-sectional analysis of our ongoing randomized, double-blind clinical trial NCT03371225. Data for this study were collected from May 13, 2019 to January 22, 2022 from the baseline visits, before the intervention period. This study obeys the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mass General Brigham's ethics committee under protocol number 2017P002524. All participants have given their written informed consent. A detailed description of the protocol is published elsewhere (18).

Patients between 18 and 65 years old were eligible to participate if they met the diagnosis of fibromyalgia pain according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2010 criteria and widespread pain for more than 6 months with an average of at least 4 on a 0–10 Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scale without another comorbid chronic pain diagnosis; also patients had to be pain resistant to common analgesics. The exclusion criteria were: the presence of any clinically significant or unstable medical or psychiatric disorder; history of substance abuse within the past 6 months; previous significant neurological history resulting in neurological deficits; severe depression, pregnancy or current opiate use in large doses (more than 30 mg of oxycodone/hydrocodone or equivalent).

Temporal Summation Paradigms and Questionnaires

Temporal Slow Pain Summation (TSPS-phasic)

We first trained subjects to determine the pain-60 test temperature [the temperature inducing pain sensation at a magnitude of 60 on a 0–100 numerical pain scale (NPS)] by applying a Peltier thermode (Medoc Advanced Medical Systems, Ramat Yishai, Israel) on the right forearm using a 30 mm ×30 mm embedded heat pain (HP) thermode. We delivered three short heat stimuli (43, 44, and 45°C), each lasting 7 s. They were asked to report their subjective levels of pain intensity using the visual analog scale for pain (VAS) on a scale ranging from 0, denoting “no pain,” to 100, denoting “the worst pain imaginable.” If the first temperature of 43°C was considered too painful (>60/100), we stopped the series and provided additional stimuli at lower temperatures of 41°C and 42°C. If the three temperatures (43, 44, and 45°C) were unable to achieve the pain-60, we delivered additional stimuli at 46, 47, and 48°C until reaching the desired pain level of 60/100; in the unlikely event that none of those temperatures elicited pain-60, we considered it to be 48°C. We then delivered pulses with rise/fall of 1–2 s, with a rate of change of 8 degrees per second and a delta of 7 degrees, from adapting temperatures to peak temperatures (pain-60), with a plateau of 0.7 s. They received one train of 15 repetitive heat stimuli at 0.4 Hz and pain ratings were asked after the 1st and 15th stimuli: TSPS-phasic was calculated as the difference between those ratings (after the 15th minus after the 1st).

Tonic Heat Test Stimulus- (TSPS-tonic)

In addition to the Temporal Summation resulting from the short repetitive stimuli described above, we also calculated the pain summation resulting from the tonic heat test stimulus performed during our Conditioned Pain Modulation paradigm. Ten minutes after the TSPS protocol, we administered the tonic heat test stimulus at the pain-60 temperature continuously for 30 s, and we asked the subjects to rate their pain levels using the visual analog scale for pain (VAS) on a scale ranging from 0, denoting “no pain,” to 100, denoting “the worst pain” imaginable after 10, 20 and 30 s. TSPS-tonic was calculated as the difference between the ratings after 30 s minus the ratings after 10 s.

Questionnaires

We collected baseline demographic data and questionnaires including: pain intensities, self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, and sleepiness levels with the visual analog scale-−0–10 point scale [VAS pain (19), VAS depression (20), VAS anxiety (21), VAS stress (20), and VAS sleepiness (19), respectively]; Modified Brief Pain Inventory-BPI (with subscales of average pain ratings and ratings of pain interference in daily living (BPI-pain and BPI-interference, respectively), as well as number of locations in the body with pain (BPI- Number of locations): this scale provides information on various dimensions of pain including how pain developed, the types of pain a patient experiences, time of day pain is experienced, as well as current ways of alleviating pain and the distribution of pain (19, 22); Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR) (19), this is a 21-item (0–100 points), multiple-choice questionnaire that assess function, overall impact and symptoms (23); quality of life assessed by Quality of Life Scale (QOL), this is a 16-item (16–112 points), multi-purpose questionnaire that yields a profile of functional health and wellbeing scores (24); Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System for anxiety, fatigue and pain (PROMIS anxiety, PROMIS fatigue, and PROMIS pain, 0–5 points respectively) (19); Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (25), this questionnaire assesses seven components of sleep quality: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction over the last month and a total sum of “5” or greater indicates a “poor” sleeper; and Beck Depression Inventory (0–63 points) (26).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, i.e., mean, frequencies, and percentages, were analyzed to describe the demographical, social, and clinical characteristics of the study participants. We initially performed univariable analyses of the relationship between TSPS-phasic and TSPS-tonic (Pearson correlation), and subsequently between each of those measures and the demographic and clinical variables collected at baseline (univariable linear regressions). We then built multivariable linear regression models with the objective of finding variables associated with TSPS-phasic and TSPS-tonic, while including potential confounders and avoiding collinearity. Model-building followed a purposeful selection procedure (27): we initially included variables with p < 0.25 (from the univariable analysis), and tested the other variables by including them in the model one-by-one and, if they became significant in the multivariable model, or if they changed the Beta-coefficients by more than 20%, we kept them in the final model. We also included, based on prior knowledge, the variables age and sex in our models and tested them the same way we tested the other variables: if the variables, once inserted in the multivariable model, became not significant and did not change the Beta-coefficients by more than 20%, they were removed from the model. All statistical analyses and graphical outputs for this paper were generated using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

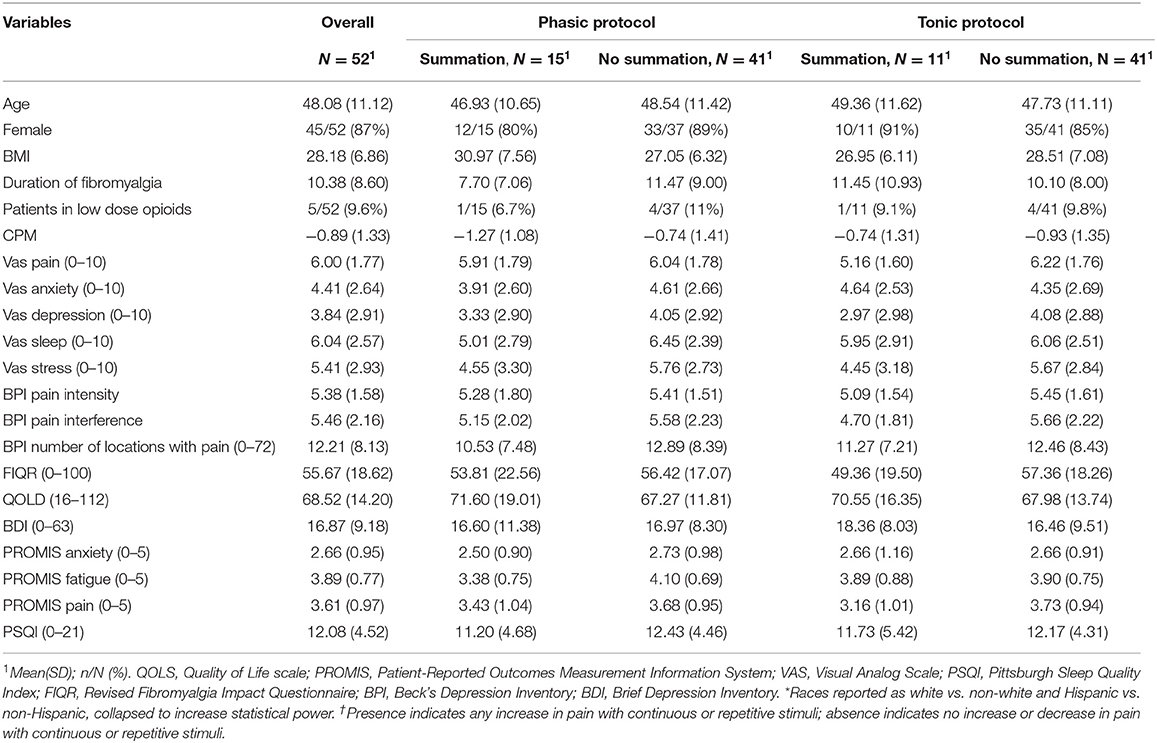

We included 52 fibromyalgia patients, 86.5% of them female, with a mean of 48.1 years (SD 11.1) in our analysis. The average of VAS pain was 6 (SD 1.77) and a mean of 10 years of fibromyalgia pain (SD 8.6) (Table 1).

TSPS – Phasic Protocol

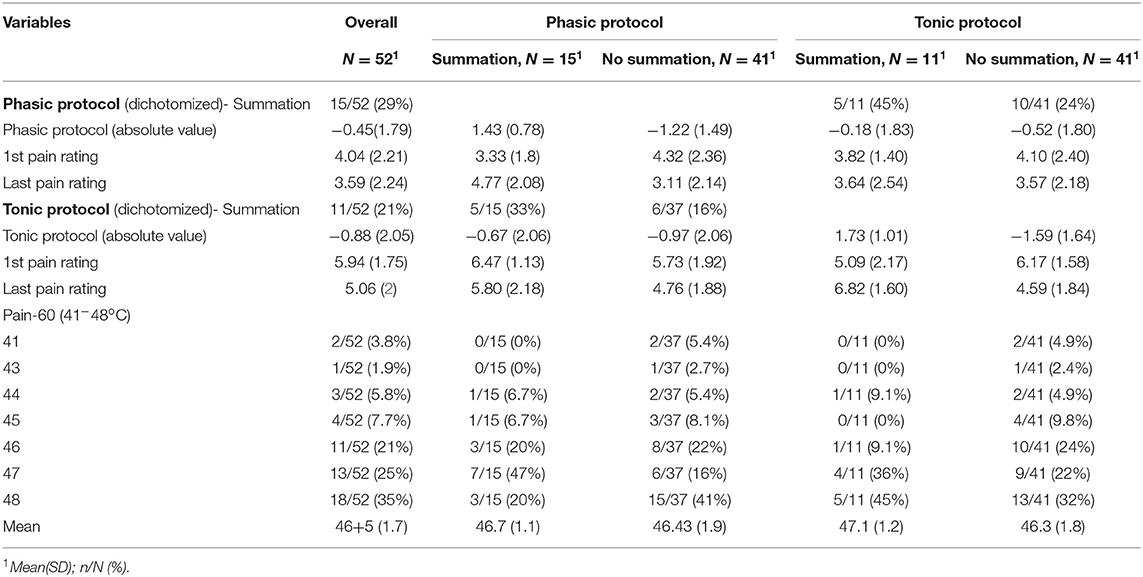

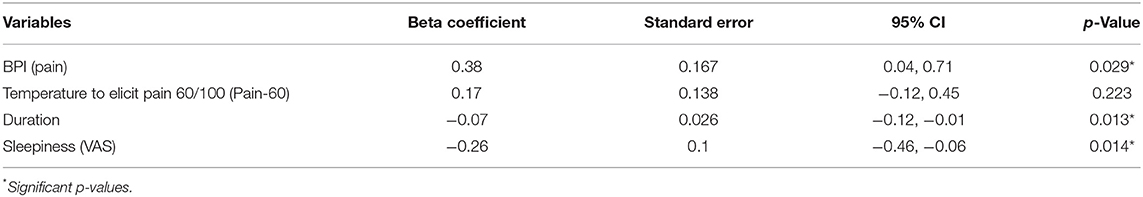

28.85% developed summation during the TSPS-phasic protocol (pain ratings at the end higher than pain ratings at the beginning of the test), 32.69% had no changes during the TSPS-phasic protocol and 38.46% decreased their pain ratings (Table 2). From the univariate models, there were no significantly associated variables with an increase in temporal summation (higher VAS after the stimulus) at a 0.05 significance level (Table 3, Figure S1). Following our multivariable building process, we first included the variables female, age, duration of disease, sleepiness measured by VAS, and PROMIS for fatigue in our model, resulting in an adjusted R-square of 0.11. For the next step, we removed the variables with a p < 0.1 and that did not change the beta-coefficients of the other variables by more than 20%, resulting in a model with duration of disease and sleepiness measured by VAS and an adjusted R-square of 0.12. We then included, one by one, the other variables, keeping them if they fulfilled the previous criteria, resulting in a final multivariate model for the TSPS-phasic protocol, where the BPI-pain subscale was associated with more temporal summation (ß = 0.38, p = 0.029), adjusted by pain-60, the duration of fibromyalgia and VAS sleepiness, with an R-square of 0.18 (Table 4).

Table 3. Univariable analysis of the association between TSPS-phasic and TSPS-tonic with other baseline characteristics.

TSPS – Tonic Protocol

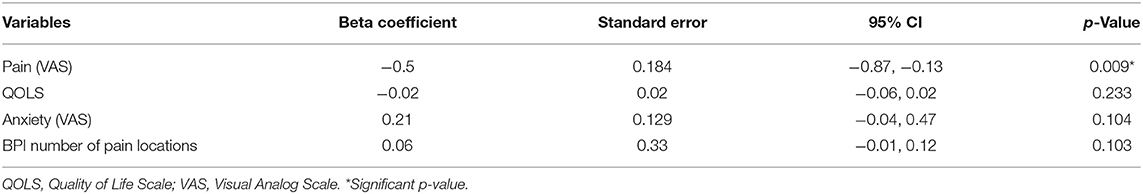

21.15% developed summation during the TSPS-tonic protocol. 25% had no changes in the TSPS-tonic protocol and 53.85% decreased their pain ratings (Table 2). From the univariate models, there was no significantly associated variables with an increase in temporal summation (higher VAS after the stimulus) at a 0.05 significance level (Table 3, Figure S1). Following our multivariable building process, we first included the variables female, age, pain measured by VAS, QOLs, pain 60, and number of locations with pain in our model, resulting in an adjusted R-square of 0.07. For the next step, we removed the variables with a p < 0.1 and that did not change the beta-coefficients of the other variables by more than 20%, resulting in a model with pain measured by VAS, QOLs and number of locations with pain and an adjusted R-square of 0.10. We then included, one by one, the other variables, keeping them if they fulfilled the previous criteria, resulting in a final multivariate model for the TSPS-tonic protocol with VAS pain was associated with less temporal summation (ß = −0.45, p = 0.019), adjusted by QOL, number of locations in the body with pain from the BPI, and VAS anxiety, with an adjusted R-square of 0.13 (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study aimed to explore the phenomenon of temporal summation in fibromyalgia patients. We explored the agreement between phasic and tonic temporal summation protocols, as well as the relationship with patients' characteristics. Temporal summation of pain happened in only a minority of our sample and both protocols did not correlate. In our exploratory analysis using multivariable linear regression modeling, we found that the relationship between baseline covariates and heat temporal summation could be different for the two protocols.

Fibromyalgia is a complex and heterogeneous syndrome. In fact, this challenging diagnosis has been a matter of debate for decades, relying solely on symptom evaluation (18), although researchers have attempted to identify biomarkers and surrogates to support it (28). The frequently replicated but still contradictory finding of enhanced temporal summation of pain in FM has been quite persuasive and has led to an increase of research on the central sensitization paradigm in FM. In our study, only a minority of our FM sample in fact showed increased temporal summation, regardless of the protocol (tonic or phasic), a result that comes to add to other similar ones in the literature (10). The differences found in our results could be the consequence of the characteristics of the clinical condition and also our study sample, as it has contrasts in some features from the overall fibromyalgia population. Given our protocol, FM patients included should have been willing and be capable to perform 30 min of aerobic exercise, have less than mild to moderate depression levels (BDI <30) and be able to commit to multiple in-person visits throughout our parent RCT [see our published protocol for a detailed description of the study visits (29)]. There is evidence of exercise improving chronic pain including pain thresholds but is still contradictory if an exercise program can induce changes in central sensitization in chronic pain patients (30, 31). Also, different studies have shown prominent prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder diagnosis and moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms in FM (32–34), which have been linked to the severity of the disease (35); Uhl et al. (36) found a positive correlation of patients with major depression with an increase pain perception after frequent noxious stimuli in a temporal summation protocol. Depression is a key factor for the epidemiology and pathophysiology of FM, while they might even share similar genetic pathways (37). Depression is a factor that might moderately modify pain-related negative affect, therefore creating variance in pain intensity within the population (38). There are similar changes in neuroplasticity between patients with chronic pain and depression (39, 40). Therefore, our sample of patients who were capable and willing to do exercise and were not depressed, could have less summation than other samples of FM patients.

Our study did not find a correlation between the phasic and the tonic TSPS protocols. There is heterogeneity in the description of protocols for temporal summation in the literature. O'Brien et al. (3) published a review of TS in fibromyalgia patients. They assessed 23 studies (n = 648) and found a large variability regarding population, methodology and parameters of stimulations (type of stimuli, number of stimuli, duration, and location): the most common stimuli used was thermal, followed by mechanical and electrical. Staud et al. (41) found significant differences in the pain ratings of the fifth stimulus in FM patients, but no difference between the 1st and last stimulus between groups: they studied 14 FM patients and 19 healthy controls using a phasic TS protocol over the palmar surface of the hands with a heat stimuli. Moreover, Potvin et al. (10) included 72 fibromyalgia patients and 39 healthy women and tested tonic heat temporal summation over the left arm: there was no significant difference between healthy controls and fibromyalgia patients, but they found that patients with a temperature of ≥45°C as pain-50 had an increased summation of pain after the stimulus compared to patients with pain-50 <45°C temperature. The phasic protocol for temporal summation is the most reported in the literature (9, 15, 42–46). For example, Granot et al. (15) compared the phasic and tonic protocols of temporal summation in healthy subjects and found a significant correlation, suggesting that both represent similar neurophysiological processes. Also, Granot et al. (47) aimed to measure the psychophysics of the phasic and tonic phases in healthy volunteers with a different protocol and found a correlation between the tonic and phasic protocols, but no differences in the pain scores. However, most of the research describing the difference between protocols are in healthy subjects.

Given the differences between the tonic and phasic TSPS we found in our results, which may rely on several aspects, we believe that these two types of temporal summation measures could be, in fact, representing different phenomena in chronic pain patients. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the two paradigms in our study could be that the pain-60 used might have been too high, in particular for the tonic paradigm, curtailing the subject's ability to discern differences in pain ratings. The average pain rating after the first stimulus in the phasic protocol was, on a scale from 0 to 10, 4.04 (SD 2.21) and after the last stimulus 3.59 (SD 2.24). These measures were higher during the tonic paradigm, with average pain rating after the first recorded measure of 5.94 (SD 1.75) and after the last measure 5.06 (SD 2.00). This fact can also explain why only 28.9% of our subjects developed summation during the phasic protocol and 21.2% during the tonic protocol. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that in the subgroup with pain-60 at 48 degrees Celsius (who possibly did not feel the same pain levels as the other patients, since 48 degrees was our maximum temperature), the incidence of temporal summation with the phasic protocol was less than the overall, 16.7%, and with the tonic protocol it was more than the overall, 27.8%.

The mechanisms underlying the temporal summation phenomenon present in some FM patients are still not well understood. It is believed that temporal summation of pain happens in C-fibers located at the spinal dorsal-horn neurons, mediated by glutaminergic excitatory synapses and thus NMDA receptors, since the blockade of NMDA receptors has been associated with decrease in temporal summation to nociceptive stimuli (48, 49). Staud et al. (50) found that, although FM subjects did have more temporal summation than healthy controls at first, they did not respond differently to external NMDA-blockage. This suggests that differences in responsiveness in these pathways could not explain entirely the maladaptive pain processing in FM. Instead, alternative pain modulation mechanisms, including disruptions in inhibitory descendent control and emotional-cognitive circuitry, can play equally important roles in different subsets of FM patients. One of the possible explanations would be that temporal summation of pain is a “trait” of a subset of patients rather than a “state” in FM. It is worth mentioning that phasic temporal summation protocols could also be testing phenomena known as offset analgesia (OA) and onset hyperalgesia (OH). The paradigms for testing OA and OH require transient increases or decreases in thermal noxious stimuli, and are believed to be related to time-dependent anticipation of pain relief with a decreasing temperature or anticipation of pain worsening with increasing temperature. These responses to expectation/anticipation would be thus associated with central, rather than peripheral, nociceptive pathways (51).

Central sensitization phenotypes, as measured by temporal summation, are not homogenous across different strata of FM patients. The attempt to find FM subsamples, sharing similar syndromic and pathological mosaics, has been suggested before and is potentially the future fostering multi-modal and individually-tailored treatment in FM (1). This seems likely to be an adequate pathway to better understand the complexity of biomarkers, prognosis, and treatment response in FM, considering the complexity of this widespread pain entity. Since our sample of patients who developed summation in the phasic and tonic protocols do not overlap (only five subjects developed summation in both protocols), the use of different paradigms could also help in identifying these subsamples who would potentially respond differently to therapies.

In our exploratory analysis with multivariate models, which were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, pain scales measured with the BPI-pain subscale and VAS were found to be associated with the phasic-TSPS and tonic-TSPS, respectively. Interestingly, age and sex were not associated with temporal summation in any of the final multivariable models (52, 53). In the phasic-TSPS protocol, more pain in the BPI scale was associated with higher temporal summation, when adjusted for the duration of fibromyalgia, pain-60 levels, and sleepiness measured by VAS. In accordance, in different chronic pain populations, more temporal summation has been associated with a poorer prognosis of pain progression (54), worse disease severity (55–57), and higher experimental and clinical pain (56–59). In contrast, the relationship between tonic TSPS and pain levels was inverse, with higher pain being associated with less summation, when adjusted for QOLs, number of locations of the body with pain, and anxiety measured by VAS. This result was unexpected, but at the same time, very interesting. It is worth mentioning that this relationship, albeit maintaining the same directionality as in the univariable analysis, only became significant after the inclusion of the other variables in the model. We speculate that one possible explanantion could be that higher pain levels in the VAS could be related to more activation of emotional affective circuits, as seen in previous studies (60–64). Thus, one plausible explanation for the unexpected finding of an inverse relationship between pain levels and tonic pain summation is an overactivation of emotional circuits in subjects with higher baseline VAS, leading to worse anticipation of pain and leading to higher ratings of pain at the initial of the tonic protocol that attenuates in the second and third trials. This is supported by the fact that the average first pain rating during the tonic protocol for individuals that developed summation was 5.09 (SD 2.17) and for those who did not develop summation was 6.17 (SD 1.58) (Table 2).

In addition, regarding the tonic summation protocol, the number of locations in the body with pain, a variable that is possibly related to pain distribution, confounded the relationship between pain measured with VAS and TSPS tonic. When the variable with the number of locations was introduced in the multivariable model, the effect of VAS-pain in TSPS was even more negative, that is, the higher the VAS-pain, the less tonic summation. Interestingly, the associations between tonic-TSPS and pain distribution, and tonic-TSPS and anxiety were positive, meaning that the higher the number of pain locations and the higher the anxiety scores (measured by VAS) resulted in higher tonic-TSPS. These relationships should be interpreted with caution given our relatively small sample size and the fact that they were not signitificant at a significance level of 0.05.

One of the limitations of our study is that we did not measure pain catastrophizing. Pain catastrophizing has been overly associated with other pain-related outcomes in fibromyalgia, even as an independent agent in pain processing mechanisms (65). Kim et al. (66) showed a significant moderate correlation between tonic temporal summation and scores on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) in fibromyalgia patients (r = 0.53, p < 0.05). In the same way, catastrophizing has also shown positive correlations to temporal summation in healthy samples (15, 67, 68) and in other chronic pain populations (69–71). Hasset et al. (72) also found a strong correlation (0.71) between pain catastrophizing and depression and since we excluded from our sample individuals with BDI >30, we might have introduced selection bias, thus excluding individuals with high levels of pain catastrophizing who would be more prone to develop pain summation. Indeed, VAS scale may reflect more the emotional aspects of pain severity than central sensitization.

In addition to the association found between the BPI-pain assessments and phasic-TSPS, the duration of fibromyalgia and sleepiness were considered confounders in the multivariate model. These variables were inversely related to the outcome; patients with longer disease duration and more significant VAS sleepiness showed less phasic pain summation. Again, one possible explanation could be that the association between these variables and other mechanisms related to pain perception, such as attention and coping strategies, could contribute to this finding. In a prospective cohort (73), patients with a more substantial period since diagnosis develop ameliorated emotional coping strategies than individuals recently diagnosed. Regarding the negative correlation between the phasic temporal summation of pain and sleepiness, attentional circuitry of pain processing and basal autonomic activity were likely involved, as these supraspinal networks are intrinsically related to the magnitude of pain perception (74). Sleepiness is related to an individual's intrinsic attention (75). Adams et al. suggest that the degree to which an individual perceives pain is associated with their level of awareness (75). Moreover, increased sleepiness could signify a greater overall emotional relaxation of the patient, considering that when sleeping, the parasympathetic nervous system is dominant compared to the sympathetic nervous system (76). Since increased sympathetic nervous system activity is associated with increased pain perception (77), it is also possible that a decreased arousal in our sample with higher VAS sleepiness scores could be affecting the neurobiological circuitry involved in the summation of pain in these individuals. Temporal summation is dependent on biological processes that involve glutamatergic excitatory receptors in the central nervous system (3); therefore, this decrease in the excitatory arousal could be lowering the activity of this circuitry, decreasing phasic TSPS scores.

Another limitation in our study was the fact we did not ask our subjects the maximum pain levels felt during our summation paradigms. Therefore, they might have developed summation during our tests but we were not able to capture it at the pre-defined timepoints because the pain levels decreased afterwards. Another limitation is the fact that, although the surface temperature of the skin was measured by the thermode, and we know that such superficial temperature behaved as we planned, the same is not necessarily true for the temperature in the subcutaneous tissue. This might be problematic in particular for the tonic stimulus, when the dynamics of tissue perfusion and heat dissipation could have played a role in the absence of tonic summation observed in most of our subjects. Another limitation is the fact that both our protocols for summation involved response to heat, therefore, our findings could be different if other stimuli, i.e., pressure, were used (78). Finally, due to the exploratory nature of our analyses, no corrections for multiple comparisons were made. Thus, the results from our univariable and, in particular, our multivariable models should be interpreted as hypothesis- generating and, by no means, confirmatory. Further studies with larger sample sizes would be needed to elucidate the relationship between clinical variables and different temporal summation protocols in chronic pain patients.

Conclusion

Temporal summation is believed to be a tool for the measurement of central sensitization by applying continuous or intermittent noxious stimulus and measuring the pain perception. From the 52 fibromyalgia patients included in our study less than 30% presented temporal summation with heat stimuli based on pain-60 temperatures. Heat phasic and tonic TSPS were also not correlated, and could potentially be used as markers differentiating FM into specific phenotypes. However, future studies are needed to standardize the tonic and phasic temporal summation protocols, and larger sample sizes could undercover the differences between these temporal summation protocols and their relationship to clinical variables in FM and other chronic pain patients.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Mass General Brigham. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

LC-B and AC-R contributed to the design of the study, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafted the paper. WC, GR, KM, and FF contributed to design of the study and revised the paper critically for important intellectual content. IR-S, KP-B, PG-M, PM, PT, PC, JP, AM, and KV-A, contributed to data acquisition and interpretation and drafted the paper. All authors approved final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH under grant (1R01AT009491-01A1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpain.2022.881543/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, Atzeni F. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2020) 16:645–60. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00506-w

3. O'Brien AT, Deitos A, Triñanes Pego Y, Fregni F. Carrillo-de-la-Peña MT. Defective endogenous pain modulation in fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis of temporal summation and conditioned pain modulation paradigms. J Pain. (2018) 19:819–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.01.010

4. Cagnie B, Coppieters I, Denecker S, Six J, Danneels L, Meeus M. Central sensitization in fibromyalgia? A systematic review on structural and functional brain MRI. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2014) 44:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.01.001

5. Youssef AM, Macefield VG, Henderson LA. Pain inhibits pain; human brainstem mechanisms. NeuroImage. (2016) 124(Pt A):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.060

6. Arendt-Nielsen L, Brennum J, Sindrup S, Bak P. Electrophysiological and psychophysical quantification of temporal summation in the human nociceptive system. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. (1994) 68:266–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00376776

7. Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. (2009) 10:895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012

8. Staud R, Vierck CJ, Cannon RL, Mauderli AP, Price DD. Abnormal sensitization and temporal summation of second pain (wind-up) in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain. (2001) 91:165–75. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00432-2

9. Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L. The importance of stimulus configuration for temporal summation of first and second pain to repeated heat stimuli. Eur J Pain. (1998) 2:329–41. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(98)90031-3

10. Potvin S, Paul-Savoie E, Morin M, Bourgault P, Marchand S. Temporal summation of pain is not amplified in a large proportion of fibromyalgia patients. Pain Res Treat. (2012) 2012:938595. doi: 10.1155/2012/938595

11. Potvin S, Marchand S. Pain facilitation and pain inhibition during conditioned pain modulation in fibromyalgia and in healthy controls. Pain. (2016) 157:1704–10. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000573

12. Price DD, Staud R, Robinson ME, Mauderli AP, Cannon R, Vierck CJ. Enhanced temporal summation of second pain and its central modulation in fibromyalgia patients. Pain. (2002) 99:49–59. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00053-2

13. Suzan E, Aviram J, Treister R, Eisenberg E, Pud D. Individually based measurement of temporal summation evoked by a noxious tonic heat paradigm. J Pain Res. (2015) 8:409–15. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S83352

14. Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Effects of age on temporal summation and habituation of thermal pain: clinical relevance in healthy older and younger adults. J Pain. (2001) 2:307–17. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.25525

15. Granot M, Granovsky Y, Sprecher E, Nir RR, Yarnitsky D. Contact heat-evoked temporal summation: tonic versus repetitive-phasic stimulation. Pain. (2006) 122:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.003

16. Nie H, Arendt-Nielsen L, Madeleine P, Graven-Nielsen T. Enhanced temporal summation of pressure pain in the trapezius muscle after delayed onset muscle soreness. Exp Brain Res. (2006) 170:182–90. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0196-6

17. Sarlani E, Greenspan JD. Gender differences in temporal summation of mechanically evoked pain. Pain. (2002) 97:163–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00015-5

18. Uygur-Kucukseymen E, Castelo-Branco L, Pacheco-Barrios K, Luna-Cuadros MA, Cardenas-Rojas A, Giannoni-Luza S, et al. Decreased neural inhibitory state in fibromyalgia pain: a cross-sectional study. Neurophysiol Clin. (2020) 50:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2020.06.002

19. Williams DA, Arnold LM. Measures of fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale, and Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire (MASQ). Arthritis Care Res. (2011) 63:S86–97. doi: 10.1002/acr.20531

20. Boomershine CS, Emir B, Wang Y, Zlateva G. Simplifying fibromyalgia assessment: the VASFIQ brief symptom scale. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. (2011) 3:215–26. doi: 10.1177/1759720X11416863

21. Williams VSL, Morlock RJ, Feltner D. Psychometric evaluation of a visual analog scale for the assessment of anxiety. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2010) 8:57. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-57

22. Cleeland C, Ryan K. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. (1994) 23:129–38.

23. Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, Ward R, Han BK, Ross RL. The revised fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther. (2009) 11:1–14. doi: 10.1186/ar2830

24. Burckhardt CS, Anderson KL. The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): reliability, validity, and utilization. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2003) 1:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-60

25. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

26. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. (1988) 8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

27. Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. (2008) 3:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17

28. Hackshaw KV. The search for biomarkers in fibromyalgia. Diagnostics. (2021) 11:156. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11020156

29. Castelo-Branco L, Uygur Kucukseymen E, Duarte D, El-Hagrassy MM, Bonin Pinto C, Gunduz ME, et al. Optimised transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for fibromyalgia-targeting the endogenous pain control system: a randomised, double-blind, factorial clinical trial protocol. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e032710. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032710

30. Hall M, Dobson F, Plinsinga M, Mailloux C, Starkey S, Smits E, et al. Effect of exercise on pain processing and motor output in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2020) 28:1501–13. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.07.009

31. Pacheco-Barrios K, Carolyna Gianlorenço A, Machado R, Queiroga M, Zeng H, Shaikh E, et al. Exercise-induced pain threshold modulation in healthy subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Princ Pract Clin Res. (2020) 6:11–28. doi: 10.21801/ppcrj.2020.63.2

32. Arnold LM, Leon T, Whalen E, Barrett J. Relationships among pain and depressive and anxiety symptoms in clinical trials of pregabalin in fibromyalgia. Psychosomatics. (2010) 51:489–97. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(10)70741-6

33. Aguglia A, Salvi V, Maina G, Rossetto I, Aguglia E. Fibromyalgia syndrome and depressive symptoms: comorbidity and clinical correlates. J Affect Disord. (2011) 128:262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.004

34. Palomo-López P. Becerro-de-Bengoa-Vallejo R, Elena-Losa-Iglesias M, López-López D, Rodríguez-Sanz D, Cáceres-León M, et al. Relationship of depression scores and ranges in women who suffer from fibromyalgia by age distribution: a case-control study. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. (2019) 16:211–20. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12358

35. Alok R, Das SK, Agarwal GG, Salwahan L, Srivastava R. Relationship of severity of depression, anxiety and stress with severity of fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2011) 29(6 Suppl 69):S70–2.

36. Uhl I, Krumova EK, Regeniter S, Bär KJ, Norra C, Richter H, et al. Association between wind-up ratio and central serotonergic function in healthy subjects and depressed patients. Neurosci Lett. (2011) 504:176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.09.033

37. Gracely RH, Ceko M, Bushnell MC. Fibromyalgia and depression. Pain Res Treat. (2012) 2012:486590. doi: 10.1155/2012/486590

38. Staud R, Price DD, Robinson ME, Vierck CJ Jr. Body pain area and pain-related negative affect predict clinical pain intensity in patients with fibromyalgia. J Pain. (2004) 5:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.05.007

39. Yang S, Chang MC. Chronic pain: structural and functional changes in brain structures and associated negative affective states. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:3130. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133130

40. Baliki MN, Apkarian AV. Nociception, pain, negative moods, and behavior selection. Neuron. (2015) 87:474–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.005

41. Staud R, Weyl EE, Riley JL III, Fillingim RB. Slow temporal summation of pain for assessment of central pain sensitivity and clinical pain of fibromyalgia patients. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e89086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089086

42. Price DD, Hu JW, Dubner R, Gracely RH. Peripheral suppression of first pain and central summation of second pain evoked by noxious heat pulses. Pain. (1977) 3:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90035-5

43. Lautenbacher S, Roscher S, Strian F. Tonic pain evoked by pulsating heat: temporal summation mechanisms and perceptual qualities. Somatosens Mot Res. (1995) 12:59–70. doi: 10.3109/08990229509063142

44. Vierck CJ Jr, Cannon RL, Fry G, Maixner W, Whitsel BL. Characteristics of temporal summation of second pain sensations elicited by brief contact of glabrous skin by a preheated thermode. J Neurophysiol. (1997) 78:992–1002. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.992

45. Weissman-Fogel I, Sprecher E, Granovsky Y, Yarnitsky D. Repeated noxious stimulation of the skin enhances cutaneous pain perception of migraine patients in-between attacks: clinical evidence for continuous sub-threshold increase in membrane excitability of central trigeminovascular neurons. Pain. (2003) 104:693–700. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00159-3

46. Staud R, Price DD, Robinson ME, Mauderli AP, Vierck CJ. Maintenance of windup of second pain requires less frequent stimulation in fibromyalgia patients compared to normal controls. Pain. (2004) 110:689–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.009

47. Granot M, Sprecher E, Yarnitsky D. Psychophysics of phasic and tonic heat pain stimuli by quantitative sensory testing in healthy subjects. Eur J Pain. (2003) 7:139–43. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00087-3

48. Guirimand F, Dupont X, Brasseur L, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. The effects of ketamine on the temporal summation (wind-up) of the R(III) nociceptive flexion reflex and pain in humans. Anesth Analg. (2000) 90:408–14. doi: 10.1213/00000539-200002000-00031

49. Arendt-Nielsen L, Petersen-Felix S, Fischer M, Bak P, Bjerring P, Zbinden AM. The effect of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist (ketamine) on single and repeated nociceptive stimuli: a placebo-controlled experimental human study. Anesth Analg. (1995) 81:63–8. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199507000-00013

50. Staud R, Vierck CJ, Robinson ME, Price DD. Effects of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dextromethorphan on temporal summation of pain are similar in fibromyalgia patients and normal control subjects. J Pain. (2005) 6:323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.357

51. Alter BJ, Aung MS, Strigo IA, Fields HL. Onset hyperalgesia and offset analgesia: Transient increases or decreases of noxious thermal stimulus intensity robustly modulate subsequent perceived pain intensity. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0231124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231124

52. Sarlani E, Grace EG, Reynolds MA, Greenspan JD. Sex differences in temporal summation of pain and aftersensations following repetitive noxious mechanical stimulation. Pain. (2004) 109:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.019

53. Lautenbacher S, Kunz M, Strate P, Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L. Age effects on pain thresholds, temporal summation and spatial summation of heat and pressure pain. Pain. (2005) 115:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.025

54. Petersen KK, Jensen MB, Graven-Nielsen T, Hauerslev LV, Arendt-Nielsen L, Rathleff MS. Pain catastrophizing, self-reported disability, and temporal summation of pain predict self-reported pain in low back pain patients 12 weeks after general practitioner consultation: a Prospective Cohort Study. Clin J Pain. (2020) 36:757–63. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000865

55. Lee YC, Bingham CO 3rd, Edwards RR, Marder W, Phillips K, Bolster MB, et al. Association between pain sensitization and disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res. (2018) 70:197–204. doi: 10.1002/acr.23266

56. Owens MA, Bulls HW, Trost Z, Terry SC, Gossett EW, Wesson-Sides KM, et al. An examination of pain catastrophizing and endogenous pain modulatory processes in adults with chronic low back pain. Pain Med. (2016) 17:1452–64. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv074

57. Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, et al. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain. (2010) 149:573–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003

58. Owens MA, Parker R, Rainey RL, Gonzalez CE, White DM, Ata AE, et al. Enhanced facilitation and diminished inhibition characterizes the pronociceptive endogenous pain modulatory balance of persons living with HIV and chronic pain. J Neurovirol. (2019) 25:57–71. doi: 10.1007/s13365-018-0686-5

59. Overstreet DS, Michl AN, Penn TM, Rumble DD, Aroke EN, Sims AM, et al. Temporal summation of mechanical pain prospectively predicts movement-evoked pain severity in adults with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2021) 22:429. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04306-5

60. Vidor LP, Torres IL, Medeiros LF, Dussán-Sarria JA. Dall'agnol L, Deitos A, et al. Association of anxiety with intracortical inhibition and descending pain modulation in chronic myofascial pain syndrome. BMC Neurosci. (2014) 15:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-42

61. Teixeira PEP, Zehry HI, Chaudhari S, Dipietro L, Fregni F. Pain perception in chronic knee osteoarthritis with varying levels of pain inhibitory control: an exploratory study. Scand J Pain. (2020) 20:651–61. doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2020-0016

62. Tavares DRB, Moça Trevisani VF, Frazao Okazaki JE, Valéria de Andrade Santana M, Pereira Nunes Pinto AC, Tutiya KK, et al. Risk factors of pain, physical function, and health-related quality of life in elderly people with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Heliyon. (2020) 6:e05723. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05723

63. Teixeira PEP, Pacheco-Barrios K, Uygur-Kucukseymen E, Machado RM, Balbuena-Pareja A, Giannoni-Luza S, et al. Electroencephalography signatures for conditioned pain modulation and pain perception in nonspecific chronic low back pain—an exploratory study. Pain Med. (2022) 23:558–70. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab293

64. Simis M, Imamura M, Pacheco-Barrios K, Marduy A, de Melo PS, Mendes AJ, et al. EEG theta and beta bands as brain oscillations for different knee osteoarthritis phenotypes according to disease severity. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:1480. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-04957-x

65. Gracely RH, Geisser ME, Giesecke T, Grant MA, Petzke F, Williams DA, et al. Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain. (2004) 127(Pt 4):835–43. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh098

66. Kim J, Loggia ML, Cahalan CM, Harris RE, Beissner FDPN, Garcia RG, et al. The somatosensory link in fibromyalgia: functional connectivity of the primary somatosensory cortex is altered by sustained pain and is associated with clinical/autonomic dysfunction. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2015) 67:1395–405. doi: 10.1002/art.39043

67. Rhudy JL, Martin SL, Terry EL, France CR, Bartley EJ, DelVentura JL, et al. Pain catastrophizing is related to temporal summation of pain but not temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex. Pain. (2011) 152:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.041

68. Edwards RR, Smith MT, Stonerock G, Haythornthwaite JA. Pain-related catastrophizing in healthy women is associated with greater temporal summation of and reduced habituation to thermal pain. Clin J Pain. (2006) 22:730–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210914.72794.bc

69. Carriere JS, Martel MO, Meints SM, Cornelius MC, Edwards RR. What do you expect? C atastrophizing mediates associations between expectancies and pain-facilitatory processes. Eur J Pain. (2019) 23:800–11. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1348

70. Goodin BR, Glover TL, Sotolongo A, King CD, Sibille KT, Herbert MS, et al. The association of greater dispositional optimism with less endogenous pain facilitation is indirectly transmitted through lower levels of pain catastrophizing. J Pain. (2013) 14:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.007

71. George SZ, Wittmer VT, Fillingim RB, Robinson ME. Sex and pain-related psychological variables are associated with thermal pain sensitivity for patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain. (2007) 8:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.05.009

72. Hassett AL, Cone JD, Patella SJ, Sigal LH. The role of catastrophizing in the pain and depression of women with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. (2000) 43:2493–10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11 <2493::AID-ANR17>3.0.CO;2-W

73. Baumgartner E, Finckh A, Cedraschi C, Vischer TL. A six year prospective study of a cohort of patients with fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. (2002) 61:644–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.7.644

74. Villemure C, Schweinhardt P. Supraspinal pain processing: distinct roles of emotion and attention. Neuroscientist. (2010) 16:276–84. doi: 10.1177/1073858409359200

75. Adams G, Harrison R, Gandhi W, van Reekum CM, Salomons TV. Intrinsic attention to pain is associated with a pronociceptive phenotype. Pain Rep. (2021) 6:e934. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000934

76. Zoccoli G, Amici R. Sleep and autonomic nervous system. Curr Opin Physiol. (2020) 15:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2020.01.002

77. Kyle BN, McNeil DW. Autonomic arousal and experimentally induced pain: a critical review of the literature. Pain Res Manag. (2014) 19:159–67. doi: 10.1155/2014/536859

Keywords: temporal summation, TSPS, tonic, phasic, fibromyalgia, central sensitization, quantitative sensory testing, QST

Citation: Castelo-Branco L, Cardenas-Rojas A, Rebello-Sanchez I, Pacheco-Barrios K, de Melo PS, Gonzalez-Mego P, Marduy A, Vasquez-Avila K, Costa Cortez P, Parente J, Teixeira PEP, Rosa G, McInnis K, Caumo W and Fregni F (2022) Temporal Summation in Fibromyalgia Patients: Comparing Phasic and Tonic Paradigms. Front. Pain Res. 3:881543. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2022.881543

Received: 22 February 2022; Accepted: 16 May 2022;

Published: 22 June 2022.

Edited by:

Ryan Patel, King's College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Laura Frey-Law, The University of Iowa, United StatesBenedict Alter, University of Pittsburgh, United States

Copyright © 2022 Castelo-Branco, Cardenas-Rojas, Rebello-Sanchez, Pacheco-Barrios, de Melo, Gonzalez-Mego, Marduy, Vasquez-Avila, Costa Cortez, Parente, Teixeira, Rosa, McInnis, Caumo and Fregni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felipe Fregni, ZnJlZ25pLmZlbGlwZUBtZ2guaGFydmFyZC5lZHU=

Luis Castelo-Branco

Luis Castelo-Branco Alejandra Cardenas-Rojas

Alejandra Cardenas-Rojas Ingrid Rebello-Sanchez1

Ingrid Rebello-Sanchez1 Kevin Pacheco-Barrios

Kevin Pacheco-Barrios Paulo S. de Melo

Paulo S. de Melo Paola Gonzalez-Mego

Paola Gonzalez-Mego Karen Vasquez-Avila

Karen Vasquez-Avila Wolnei Caumo

Wolnei Caumo Felipe Fregni

Felipe Fregni