94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Pain Res., 12 September 2022

Sec. Pediatric Pain

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2022.1001028

This article is part of the Research TopicWomen in Science: Pediatric PainView all 7 articles

Megan Greenough1*

Megan Greenough1* Tracey Bucknall2

Tracey Bucknall2 Lindsay Jibb3

Lindsay Jibb3 Krystina Lewis4

Krystina Lewis4 Christine Lamontagne5

Christine Lamontagne5 Janet Elaine Squires6

Janet Elaine Squires6

Objective: Pediatric primary chronic pain disorders come with diagnostic uncertainty, which may obscure diagnostic expectations for referring providers and the decision to accept or re-direct patients into interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs based on diagnostic completeness. We aimed to attain expert consensus on diagnostic expectations for patients who are referred to interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs with six common primary chronic pain diagnoses.

Method: We conducted a modified Delphi study with pediatric chronic pain physicians, nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists to determine degree of importance on significant clinical indicators and diagnostic items relevant to each of the six primary chronic pain diagnoses. Items were identified through point of care databases and complimentary literature and were rated by participants on a 5-point Likert scale. Our consensus threshold was set at 70%.

Results: Amongst 22 experts across 14 interdisciplinary programs in round one and 16 experts across 12 interdisciplinary programs in round two, consensus was reached on 84% of diagnostic items, where the highest degree of agreement was with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), Type 1 (100%) and the lowest with chronic pelvic pain (67%).

Conclusion: This study demonstrated a general agreement amongst pediatric chronic pain experts regarding diagnostic expectations of patients referred to interdisciplinary chronic pain programs with primary chronic pain diagnoses. Study findings may help to clarify referral expectations and the decision to accept or re-direct patients into such programs based on diagnostic completeness while reducing the occurrence of unnecessary diagnostic tests and subsequent delays in accessing specialized care.

Chronic pain in children and adolescents is prevalent and should be recognized as a major health concern in pediatrics internationally (1). The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) developed a classification of chronic pain diagnoses that distinguishes chronic primary pain and chronic secondary pain syndromes (2). Different from chronic secondary pain syndromes that are linked to an underlying condition (2), chronic primary pain cannot be explained by organic pathology (3). The most common pediatric primary chronic pain diagnoses include chronic headaches, chronic abdominal pain, chronic musculoskeletal and/or joint pain, and chronic back pain (1). Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, Type 1 (CRPS type 1) is also frequently seen in pediatric chronic pain clinics (4) and can have a significant biopsychosocial impact on children and youth (5). Chronic pelvic pain is also thought to be common in adolescent females, however the exact prevalence is unknown (6).

Chronic pain disorders are under-diagnosed in children and adolescents (4), causing significant delays in receiving specialized treatment (7, 8). Such delays are often due to diagnostic uncertainty in the chronic pain population since there is minimal evidence to support the diagnosis of “medically unexplained” pain in children (9). Pediatricians may especially experience diagnostic uncertainty in this population and there has been low agreement among pediatricians regarding chronic pain etiology and diagnostic approaches (10). Diagnostic uncertainty may be related to the tendency to complicate the diagnostic process in the chronic pain population (11) and likely increases the occurrence of unnecessary diagnostic tests. Conversely, misdiagnosing secondary pain syndromes as primary chronic pain can be harmful. Understanding pain etiology is considered the most important criterion when accepting and triaging patients to chronic pain programs (12), which highlights the need to enhance the diagnostic process for patients with primary chronic pain diagnoses. The general diagnostic process is thought to be iterative, with the goal of reducing diagnostic uncertainty, narrowing down diagnostic possibilities, and developing a more precise and complete understanding of a patient’s health problem (13). By adequately addressing the diagnostic process for pediatric primary chronic pain diagnoses, diagnostic expectations may be clarified which may reduce the occurrence of unnecessary diagnostic tests, streamline the referral process and facilitate the decision to accept or redirect patients into interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs based on diagnostic completeness.

The purpose of this study was to outline diagnostic expectations for common primary chronic pain diagnoses in the pediatric population from the perspectives of specialized pediatric chronic pain providers. Our primary objectives were to attain expert consensus on important significant clinical indicators (i.e., red flags/signs of organic pathology) that are important to assess for in patients referred to interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs, as well as to identify what diagnostic investigations are important to complete for patients who do not have significant clinical indicators, prior to acceptance into interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs. For this study, diagnoses were limited to (1) Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, Type 1 (CRPS type 1), (2) Chronic Headaches, (3) Chronic Musculoskeletal and/or Joint Pain, (4) Chronic Back Pain, (5) Chronic Abdominal Pain and (6) Chronic Pelvic Pain. Our secondary objectives were to identify common courses of action that chronic pain providers take when patients are referred to them with significant clinical indicators/red flags (e.g., re-directing the referral, denying the referral, etc.), as well as utilization of Clinical Decision Support (CDS) tools and Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) that inform the decision to accept patients based on appropriateness.

We conducted a modified Delphi study, a well-recognized method for assessing expert opinion (14, 15), with pediatric chronic pain physicians, nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. Our methodology was not considered a “classical Delphi”, which usually starts with an open-ended set of questions from participants (14). This approach has been critiqued to produce large amounts of questions that may not be well phrased which challenges the reliability and validity of the data and risks significant participant withdrawal (14). Instead, we conducted a literature search of relevant diagnostics and significant clinical indicators for each pain diagnosis lending to a more streamlined and evidence-based set of questions. We administered two-rounds of online surveys to develop consensus on the items that should be evaluated in the diagnostic investigation for the six pediatric primary chronic pain diagnoses listed above. Items included: (1) significant clinical indicators (i.e., red flags/signs of organic pathology); and in the absence of significant clinical indicators/ red flags: (2) necessary laboratory investigations; (3) necessary diagnostic imaging investigations; and (4) necessary diagnostic procedure investigations. We also assessed experts’ course of action if patients were referred with significant clinical indicators, as well as any CDS tools and PROMS they use in clarifying diagnoses and/ or facilitating their decision to accept patients into their programs.

Participants were eligible based on their role (pediatric chronic pain physicians, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists) and experience working in an interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain program (current or past). It is suggested that the quality of information obtained by the Delphi technique is improved with numbers up to 13 participants (16). Therefore, the recruitment goal for this study was to have a minimum of 20 experts participate in the first round to account for attrition.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards at both the University of Ottawa (REB #H-11-19-5122) and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (REB #2020058). Our procedures, analysis and reporting of results was guided by The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research Handbook (14) and align with the Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) recommendations (17). Pediatric chronic pain experts were invited to participate in this study through the Pediatric Pain List Serve, which is an international internet forum maintained by Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Recruitment included snowball sampling as many interested participants shared the survey invitation with eligible colleagues. Interested participants were asked to contact the Principal Investigator to confirm their interest and ensure eligibility. Confirmed and eligible participants were then sent an online link (via RedCap) to complete the first Delphi survey. Informed consent was obtained after participants read through the study’s Letter of Information, which stated “consent will be assumed upon completion of the questionnaire”. Therefore, for both Delphi rounds, consent was assumed following completion of both questionnaires. Following analysis of the first-round survey, respondents were contacted individually via email to invite them to participate in the second-round survey. For both rounds, reminder emails were sent to non-responders weekly for up to three weeks. Please see Figure 1 for an outline of our Delphi process.

Both surveys were organized based on the objectives listed above. Items were generated largely on available diagnostic literature of the six chosen pediatric primary chronic pain diagnoses, which was searched primarily through two point of care databases (DynaMed Plus and RxTx), that update clinical information frequently. Some diagnoses were not listed in either database, therefore supplemental articles were used to capture diagnostic information for the surveys. For purposes of clinical validity, the first-round survey was piloted with two pediatric chronic pain physicians and one pediatric pain nurse practitioner, which resulted in additional items added based on their recommendations. Individuals who participated in the pilot survey were not study participants and their results were not included in our analysis. The first-round survey included a total of 148 diagnostic items across the six pain diagnoses (CRPS type 1, n = 14; Chronic Headaches, n = 23; Chronic Musculoskeletal and/or Joint Pain, n = 30; Chronic Back Pain, n = 21; Chronic Abdominal Pain, n = 34; Chronic Pelvic Pain, n = 26). The second-round survey involved 85 diagnostic items involving the original items that did not reach consensus in round-one, as well as “other” items considered important by participants (CRPS type 1, n = 6; Chronic Headaches, n = 14; Chronic Musculoskeletal and/or Joint Pain, n = 20; Chronic Back Pain, n = 10; Chronic Abdominal Pain, n = 26; Chronic Pelvic Pain, n = 9). Questions regarding course of action for patients referred with significant clinical indicators were formatted as multiple choice and were not included in consensus. Participants also listed utilized CDS tools and PROMS and added additional feedback and comments as open-ended free text. The first-round and second-round surveys can be found in Supplementary Files S1, S2, respectively.

Participants were asked to rate their perceived degree of importance of significant clinical indicators/red flags and diagnostic items in the diagnostic investigation for each of the six chronic pain diagnoses on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (extremely important). Since there is no standard threshold for defining consensus (i.e., recommendations have been found to be between 51% to 80%) (16), our analysis strategy was modeled after a Delphi study that evaluated expert consensus with the goal of developing a classification system for patients with low back pain (18). Responses with a rating of three or greater were considered important, while those with a rating of one or two were considered not important. To achieve group consensus in deeming an item important to consider or include in a referred patient, 70% or more of participants rated the item as important-extremely important. To achieve group consensus in deeming an item as not important to consider or include in a referred patient, 70% or more of participants rated the item as not at all important to somewhat important. Participants were also invited to offer “other” items they believed were important to include. The second-round survey involved the items that had not reached consensus in the first round, as well as the “other” items offered by participants. Participants were able to change their responses from the first-round survey based on the outlined results and were blinded to the identity of other participants to reduce response bias. A third round was not conducted since the overall degree of consensus met in Round 2 was high at 84%. Descriptive statistics including frequencies, percentages and medians and were used to describe responses across all participants, since the median is considered the optimal statistic for describing group agreement (15). Qualitative data was captured through additional feedback offered by participants and were analyzed by thematic analysis using an inductive approach (19). Data was coded by one author and all analytical decisions were validated by all other authors. There was general agreement from all authors.

The first-round survey included a total of 22 pediatric chronic pain experts from 14 different interdisciplinary teams and 4 different countries. Two participants indicated that they previously worked in an interdisciplinary team, however both had 10–20 years of working experience with the pediatric chronic pain population and were therefore still included in the study. Sixteen (72%) of those participants, from 12 different interdisciplinary teams and 4 different countries participated in the second-round survey. Reasons for withdrawal were not provided by participants. A summary of participant demographics can be found in Table 1.

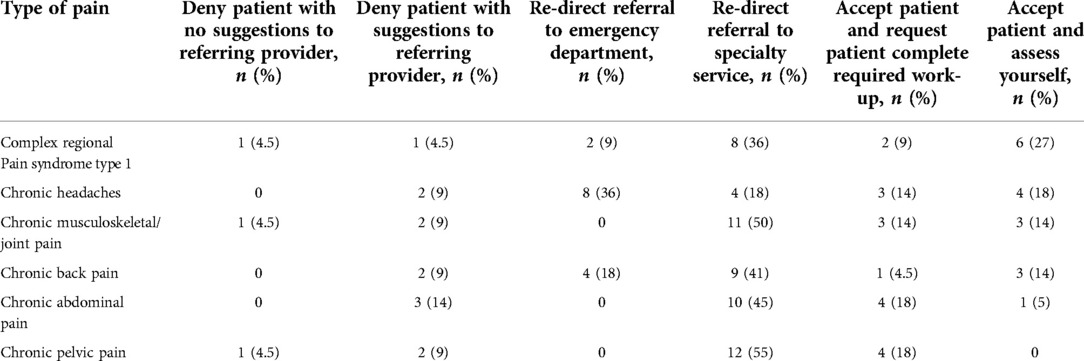

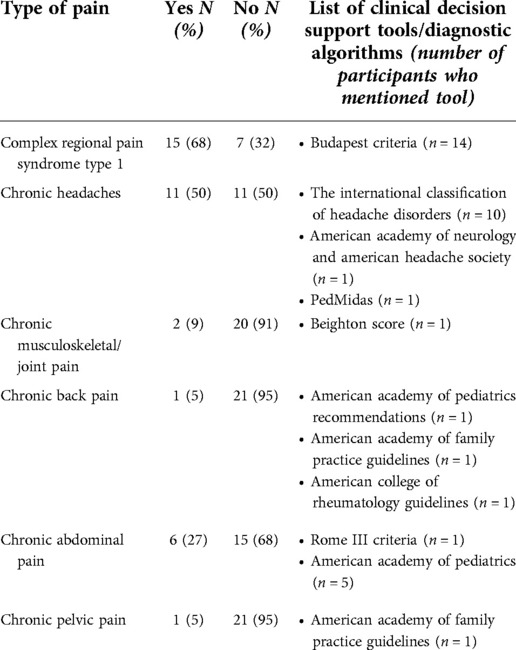

Across both rounds, 84% (157/187) of both original and “other” diagnostic items reached consensus. The highest level of overall agreement was with CRPS type 1, followed by chronic headaches, chronic musculoskeletal and/or joint pain, chronic back pain, chronic abdominal pain, and chronic pelvic pain. Included in Table 2 lists the degree of consensus reached per pain location/diagnosis and domain, as well as the items that reached consensus and their deemed importance. Items that did not reach consensus are also listed in Table 2. Course of action participants take for referred patients with significant clinical indicators/red flags are listed in Table 3 and CDS tools used by participants to inform diagnoses are listed in Table 4.

Table 3. Course of action if patient has significant clinical indicators (Red flags) prior to acceptance into interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain program.

Table 4. Use of clinical decision support tools in accepting patients to interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs.

CRPS type 1 was the only diagnosis that met 100% consensus within all domains. All significant clinical indicators/red flags were deemed important to assess for, while all diagnostic investigations were considered not important to complete prior to referral for patients without significant clinical indicators/red flags. Some participants (n = 8, 36%) indicated that for patients referred with significant clinical indicators/red flags, they would re-direct the referral to a specialty service, while 27% (n = 6) would accept the patient and assess themselves. CDS use was reported to be the highest with CRPS type 1, with 15 of 22 participates reporting that they use a CDS tool, 14 of whom specified that they follow the Budapest Criteria (20).

Consensus was reached on 91% (n = 32) of chronic headache diagnostic items, where most significant clinical indicators/red flags were deemed important (n = 17, 94%) to consider in referred patients. Most laboratory items (n = 9, 90%) were considered not important to conduct prior to referral in patients without significant clinical indicators/red flags, followed by 80% (n = 4) of diagnostic procedures and 100% (n = 2) of diagnostic imaging investigations. Some participants (n = 8, 36%) indicated that for patients referred with significant clinical indicators/red flags, they would re-direct them to an emergency department (n = 8, 36%). Half of the sample (n = 11, 50%) indicated that they use a CDS tool for chronic headache referrals, ten of whom specifically mentioned the International Classification of Headache Disorders (21).

Consensus was reached on 90% (n = 35) of chronic musculoskeletal and/or joint pain diagnostic items, where 85% (n = 11) of significant clinical indicators/red flags were deemed important to consider in referred patients. In terms of diagnostics, 95% (n = 18) of laboratory, 75% (n = 3) of diagnostic imaging investigations and all diagnostic procedure investigations (n = 3, 100%) were considered not important to conduct prior to referral in patients without significant clinical indicators/red flags. Half of participants (n = 11, 50%) indicated that they would redirect referred patients with significant clinical indicators/red flags to a speciality service. Few participants (n = 2) reported using a CDS tool, one of whom mentioned the Beighton criteria (22).

Consensus was reached on 79% (n = 19) of chronic back pain diagnostic items, with 86% (n = 5) of significant clinical indicators/red flags deemed important to consider in referred patients. Most laboratory (n = 5, 83%) and half of diagnostic imaging (n = 2, 50%) investigations were considered not important to conduct prior to referral in patients without significant clinical indicators/red flags. A selection of participants (n = 9, 41%) specified that they would re-direct referred patients with significant clinical indicator/red flags to a specialty service, while only one participant reported using CDS tools for chronic back pain referrals, referencing the American Academy of Pediatrics (23), the American Academy of Family Physicians (24) and the American College of Rheumatology (25).

Consensus was reached on 79% of chronic abdominal pain items, with 93% (n = 13) of significant clinical indicators/red flags deemed important to consider in referred patients. All diagnostic imaging (n = 4, 100%) and diagnostic procedure (n = 5, 100%) investigations were considered not important to conduct prior to referral in patients without significant clinical indicators/red flags. A portion of laboratory investigations (n = 12, 60%) met consensus and were also considered not important. Nearly half of participants (n = 10, 45%) indicated that they would re-direct patients referred with significant clinical indicators/red flags to a specialty service, while six participants reported using a CDS tool for chronic abdominal pain referrals, five of whom referenced the American Academy of Pediatrics (23) and one reported following the Rome III criteria (26).

Consensus was reached on 68% (n = 19) of chronic pelvic pain items, with 86% (n = 12) of significant clinical indicators/red flags deemed important to consider for referred patients. All four diagnostic procedure investigations and three of five (60%) diagnostic imaging investigations were considered not important to conduct prior to referral in patients without significant clinical indicators/red flags. Consensus was not reached on any of the five laboratory investigations. Some participants (n = 12, 55%) specified that they would re-direct patients with significant clinical indicators/red flags to a speciality service and one participant reported using a CDS tool for chronic pelvic pain referrals, referencing the American Academy of Family Physicians (24).

The most frequently utilized PROMs that experts reported they prefer to have completed prior to referral are the: Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (27) (n = 7/22 participants; 16/14 teams), Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) (28) (n = 7/22 participants; 5/14 teams), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (29) (n = 6/22 participants; 4/14 teams), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) (30) (n = 4/22 participants; 3/14 teams), Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) (31) (n = 2/22 participants; 2/14 teams), Faces Pain Scale Revised (FPS, R) (32) (n = 2/22 participants; 2/14 teams), Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI) (33) (n = 2/22 participants; 2/14 teams). Only single participants from different teams mentioned each of the following PROMs: Self Determination Scale (34), Insomnia Severity Index (35), Pain Related Cognition Questionnaire for Children (PRCQ-C) (36), Childhood Sleep Habits Questionnaire (37), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (38), CRAFT Substance Use Screening Tool (39), Symptom Severity Score (40), Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) (41), Body Map (42), BATH Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (43) and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (44).

Participant feedback related to the contextual influences that impact their decision to accept or re-direct referred patients based on diagnostic completeness was grouped into four categories: (1) chronic pain program contexts, (2) diagnostic role, (3) quality of referral data, and (4) evidence-informed decision making. This data highlights that although there is variation in chronic pain models and philosophies, diagnostic completeness is considered important before accepting patients into chronic pain programs. Furthermore, the quality and quantity of referral data impacts how triage decisions are made after patients are accepted (i.e., how they are prioritized). It was also noted across this group of experts that it is typically not their role to complete diagnostic investigations, but rather to collaborate with referring providers and other speciality services who take responsibility for selecting and conducting diagnostic investigations. The lack of evidence-based guidance to inform the diagnostic process with pediatric chronic pain patients was highlighted, and there is participant interest in using CDS tools and PROMS to support the decision to accept or re-direct patients based on their diagnostic completeness and appropriateness. A summary of details and exemplar quotes can be found in Table 5.

This study identified 72 significant clinical indicators/red flags that were deemed important to assess for in the diagnostic investigation of six pediatric primary chronic pain diagnoses, as well as 85 diagnostic investigations that were considered not important to complete prior to chronic pain referral in the absence of significant clinical indicators/red flags. Although classification of these items may help to reduce diagnostic uncertainty and clarify diagnostic expectations from the perspectives of specialized pediatric chronic pain providers, it is prudent to recognize that additional research is needed to attain further consensus amongst common referring providers and other specialty services.

There was good consensus to support a general recommendation to not conduct diagnostic investigations in the absence of significant clinical indicators/red flags prior to referral. This is in line with the general recommendations included in the CDS tools reported by participants. Despite this, there remains a delay between the onset of pain and the time that specialized care is received (7, 8). A recent prospective study investigating wait times for youth referred to interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs found the average wait time to be 197.5 days, which caused increased anxiety and frustration for patients and families (44). Although reasons for long wait times were not examined, authors from that study emphasized the need to investigate referral practices of pediatric interdisciplinary chronic pain programs (44). One possible factor that increases wait times may be the prolonged extent of diagnostic investigations conducted on chronic pain patients prior to referral. A recent systematic review examining the magnitude and nature of inappropriately used clinical practices in Canada in all health sectors revealed that approximately 47% of diagnostic tests are over-used (45). Many practitioners order numerous diagnostic tests with chronic pain patients in fear of missing an organic cause to patients’ pain, and in hopes of providing reassurance to patients and families (46). Interestingly, a qualitative study exploring the perception of diagnostic uncertainty in youth with chronic pain demonstrated that even if diagnostic tests were negative, they did not provide relief to families (47). It is possible that many unnecessary diagnostic tests are being ordered due to the range of ambiguous symptomatology reported by parents of children with chronic pain (48, 49), which may cloud the diagnostic picture and lead to treatment delays. A recent qualitative study investigating the diagnostic uncertainty of pediatricians evaluating chronic pain patients suggests that the decision to stop diagnostic testing on patients with unexplained chronic pain is ambiguous, complicated, and determined by many patient and physician factors (50). Further complicating this decision includes patient and family readiness to accept their chronic pain diagnosis, since 40% of parents of youth referred to pediatric chronic pain programs do not (51). Instead, these families are described as “relentlessly” searching for an alternative diagnosis they believe has been missed by their physician (51). This creates a unique circumstance for the referring provider who is attempting to juggle resource utilization and patient expectations, all the while ensuring secondary causes for pain have been ruled out.

Qualitative findings from this study highlight that many chronic pain providers do not assume a diagnostic role and that the quantity and quality of referral data is generally lacking. This presents a noteworthy gap between the expectations of referring providers and chronic pain providers who accept patients into chronic pain programs. Such challenges have potential to lead to inconsistent and complicated diagnostic processes that can influence referral practices and the decision to accept or re-direct a patient from a chronic pain program, which further worsens wait time to receiving specialized care.

The identified list of significant clinical indicators/red flags and diagnostic investigations that are required prior to referral to interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs will be helpful to include in the development of a series of CDS tools aimed to clarify diagnostic expectations and guide the decision to accept or re-direct patients with primary chronic pain diagnoses into interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs based on diagnostic completeness. Our next cumulative steps will be to: (1) conduct a qualitative study exploring the decision-making practices of pediatric chronic pain nurses who accept and triage patients into their programs, and then (2) implement a user-centered design study with a team of referring providers and pediatric chronic pain providers to identify relevant items and acceptable processes that will expand to the development of clinically useful CDS triage tools for primary chronic pain diagnoses. Although it was not an objective of this study, future exploration should consider the influence that mental health symptoms have on chronic primary pain diagnoses from the perspectives of psychologists and other mental health providers, since it is considered a significant co-morbidity (52). We hope our study can be expanded in the future to include more participants from countries outside of North America to capture a more global view of diagnostic expectations for interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs across the world.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to attain expert consensus on a large list of significant clinical indicators/red flags and required diagnostic investigations for six common pediatric primary chronic pain diagnoses from the perspectives of pediatric chronic pain experts. The diversity of respondents who were willing to participate in this study highlights an international and inter-role interest in the topic of diagnostic clarity for children and adolescents with primary chronic pain disorders. Justification for this study was qualitatively validated by participants, which highlights its relevancy to the population and community of chronic pain providers.

It is important to acknowledge the influence of bias on the validity and reliability of the Delphi method. Because this method relies on judgements, variances of results can be influenced by situation and personal bias (13, 16). Only 16 of the 22 experts participated in the second-round survey, challenging the generalizability of results. Further to this, most participants were from North America and thus findings are not geographically diverse. There is an element of selection bias, since only those subscribed to the Pain List Serve were recruited. Furthermore, this study was limited to two rounds. Although a high degree of overall consensus was met, conducting a third round may have influenced overarching results, particularly regarding chronic pelvic pain which demonstrated lowest degree of consensus. It is important to mention that the additional feedback offered by participants, identified as qualitative data, was not guided by traditional qualitative methodology, and therefore results should be interpreted with caution.

There is general agreement amongst pediatric chronic pain experts in this study regarding diagnostic expectations for patients referred to interdisciplinary chronic pain programs for six common primary chronic pain diagnoses. There is also a universal consensus not to require diagnostic tests prior to acceptance into such programs for patients without significant clinical indicators or red flags. Despite this, the literature points to significant delays in receiving specialized treatment, which amongst many other potential factors such as capacity and resource limitations, may be related to conducting unnecessary diagnostic tests and over complicating the diagnostic process. Items that met consensus in this study may help to clarify diagnostic expectations for patients with primary chronic pain diagnoses referred to interdisciplinary chronic pain programs. As a next step, it will be crucial to include the perspectives of referring providers and other relevant speciality services since they commonly assume the diagnostic role. Findings from this study, combined with our planned future work, will result in the development of a series of user-centered, evidence-based, and clinically useful CDS triage tools for interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs. We believe this has potential to ease the diagnostic process for referring providers, enhance the decision to accept or re-direct referred patients based on their diagnostic completeness and streamline the pathway to accessing specialized chronic pain evaluation and treatment. We hope this can ultimately reduce the burden of chronic pain on patients, their families, and the healthcare system.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Boards at both the University of Ottawa (REB #H-11-19-5122) and the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario (REB #2020058). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

MG, TB, LJ, KL and JES contributed to the study design, methods and REB applications. MG lead the project recruitment, data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and offered significant feedback to several manuscript drafts. CL contributed to the clinical relevancy of the topic under study and facilitated participant recruitment. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We acknowledge the Pediatric Pain List-Serve maintained by Dalhousie University for being our platform to recruit participants. We also acknowledge the pediatric chronic pain experts that participated in our study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpain.2022.1001028/full#supplementary-material.

1. King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. (2011) 152:2729–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016

2. Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennet MI, Benoliel R, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. (2015) 160:1003–7. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160

3. Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, et al. The IASP taskforce for the classification of chronic pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. (2019) 160:28–37. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001390

4. Friedrichsdorf SJ, Giordano J, Desai DK, Warmuth A, Daughtry C, Schulz CA. Chronic pain in children and adolescents: diagnosis and treatment of primary pain disorders in head, abdomen, muscles and joints. Children. (2016) 3:1–26. doi: 10.3390/children3040042

5. Abu-Arafeh H, Abu-Arafeh I. Complex regional pain syndrome in children: incidence and clinical characteristics. Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101:719–23. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310233

6. Ahangari A. Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: an updated review. Pain Physician. (2014) 17:E141–7. doi: 10.36076/ppj.2014/17/E141

7. Zernikow B, Wagner J, Hechler T, Hasan C, Rohr U, Dobe M, et al. Characteristics of highly impaired children with severe chronic pain: a 5-year retrospective study on 2249 paediatric pain patients. BMC Pediatric. (2012) 12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-54

8. Peng P, Stinson JN, Choiniere M, Dion D, Intrater H, LeFort S, et al. Dedicated multidisciplinary pain management centers for children in Canada: the current status. Can J Anesth. (2007) 54:985–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03016632

9. Konijnenberg AY, de Graeff-Meeder ER, van der Hoven J, Kimpen JLL, Buitelaar JK, Uiterwaal CSPM, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in children with medically unexplained chronic pain: diagnosis from the pediatrician’s perspective. Pediatrics. (2006) 117:889–97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0109

10. Konijnenberg AY, De Graeff-Meeder ER, Kimpen JL, van der Hoven J, Buitelar JK, Uiterwaal CS, et al. Children with unexplained chronic pain: do pediatricians agree regarding the diagnostic approach and presumed primary cause? Pediatrics. (2004) 114:1220–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0355

11. Henriques AA, Dussan-Sarria JA, Botelho LM, Caumo Q. Multidimensional approach to classifying chronic pain conditions – less is more. J Pain. (2014) 15:1119–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.08.008

12. Page MG, Ziemianski D, Shir Y. Triage processes at multidisciplinary chronic pain clinics: an international review of current procedures. Can J Pain. (2017) 1:94–105. doi: 10.1080/24740527.2017.1331115

13. Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR. Improving diagnosis in health care. National Academies: Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. (2015).

14. Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell (2011).

15. Couper MR. The Delphi technique: characteristics and sequence model. Adv Nurs Sci. (1984) 7:72–7. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198410000-00008

16. Milholland AV, Wheeler SG, Hejech JJ. Medical assessment by a Delphi group opinion technic. N Engl J Med. (1973) 288(24):1272–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306142882405

17. Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbrunch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. (2017) 31(8):684–706. doi: 10.1177/0269216317690685

18. Binkley J, Finch E, Hall J, Black T, Gowland C, DeRosa CP. Diagnostic classification of patients with low back pain: report on a survey of physical therapy experts. Phys Ther. (1993) 73:138–55. doi: 10.1093/ptj/73.3.138

19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

20. Harden RN, Bruel S, Perez RSGM, Birklein F, Marinus J, Maihofner C, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain. (2010) 150:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.030

21. International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalgia. (2018) 38:1–211.

22. Smits-Engelsman B, Klerks M, Kirby A. Beighton score: a valid measure for generalized hypermobility in children. J Pediatr. (2011) 158:119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.021

23. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Home Page. United States of America (2022). Available from: https://www.aap.org./home.html (Accessed January 3, 2022).

24. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Home Page. United States of America (2022). Available from: https://www.aafp.org/home.html (Accessed January 3, 2022).

25. American College of Rheumatology. Home Page. United States of America (2022). Available from: https://rheumatology.org (Accessed January 3, 2022).

26. Rasquin A, di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. (2006) 130:1527–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063

27. Mara CA, Kashikar-Zuck S, Cunningham N, Goldschneider KR, Huang B, Dampier C, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS pediatric pain intensity measure in children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain. (2021) 22:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2020.04.001

28. Walker LS, Greene JW. The functional disability inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J Pediatr Psychol. (1991) 16:39–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39

29. Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain severity: a comparison of six methods. Pain. (1986) 27:117–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9

30. Vervoort T, Goubert L, Eccleston C, Vandenhendle M, Claeys O, Clarke J, et al. Expressive dimensions of pain catastrophizing: an observational study in adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. (2009) 146:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.021

31. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL™ 4.0: reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life Inventory™ version 4.0 generic core scales n healthy patient populations. Med Care. (2001) 39:800–12. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006

32. Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, Addicoat L, Ziegler JB. The Faces Pain Scale for the assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. (1990) 41:139–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90018-9

33. Palermo TM, Witherspoon D, Valenzuela D, Drotar DD. Development and validation of the Child Activity Limitations Interview: a measurement of pain-related functional impairment in school-age children and adolescents. Pain. (2004) 109:461–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.023

34. Branding D, Bates P, Miner C. Perceptions of self-determination by special education and rehabilitation practitioners based on viewing a self-directed IEP versus an external-direct IEP meeting. Res Dev Disabil. (2009) 30:755–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.10.006

36. Hermann C, Hohmeister J, Zohsel K, Ebinger F, Flor H. The assessment of pain coping and pain-related cognitions in children and adolescents: current methods and further development. J Pain. (2007) 8:802–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.05.010

37. Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. (2000) 23:1–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/23.8.1d

38. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

39. Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (1999) 153:591–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591

40. Levine DW, Simmons BP, Koris MJ, Daltroy LH, Hohl GG, Fossel AH, et al. A self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Jt Surg. (1993) 75A:1585–92. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199311000-00002

41. Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatr. (1981) 45:305–15. 10.10371100788-000

42. Brummett CM, Bakshhi RR, Goesling J, Leung D, Moser SE, Zollars JW, et al. Preliminary validation of the Michigan Body Map. Pain. (2016) 157:1205–12. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000506

43. Eccleston C, Jordan A, McCracken LM, Sleed M, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ): development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. Pain. (2005) 118:263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.025

44. Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. (1983) 17:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4

45. Palermo TM, Slack M, Zhou C, Aaron R, Fisher E, Rodriquez S. Waiting for a pediatric chronic pain clinic evaluation: a prospective study characterizing waiting times and symptom trajectories. Am Pain Soc. (2019) 20:339–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.09.009

46. Squires JE, Cho-Young D, Aloisio LD, Bell R, Bornstein S, Brien SE, et al. Inappropriate use of clinical practices in Canada: a systematic review. CMAJ. (2022) 194(8):E279–96. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211416

47. DiLorenzo C, Colletti RB, Lehmann HP, Boyle JT, Gerson WT, Hyams JS, et al. Chronic abdominal pain in children: a clinical report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2005) 40:245–8. doi: 10.1097/01.MPG.0000155367.44628.21

48. Neville A, Jordan A, Pincus A, Nania C, Schulte F, Yeates KP, et al. Diagnostic uncertainty in pediatric chronic pain: nature, prevalence and consequences. Pain. (2020) 5(6):e871, 1–5. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000871

49. Heathcote LC, Williams SE, Smith AM, Sieberg CB, Simmons LE. Parent attributions of ambiguous symptoms in their children: a preliminary measure validation in parents of children with chronic pain. Children. (2018) 5:1–12. doi: 10.3390/children5060076

50. Robbins JM, Kirmayer LJ. Attributions of common somatic symptoms. Psychol Med. (1991) 21:1029–45. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700030026

51. Neville A, Noel M, Clinch J, Pincus T, Jordan A. “Drawing a line in the sand”: physician diagnostic uncertainty in pediatric chronic pain. Eur J Pain. (2020) 25:430–41. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1682

Keywords: chronic pain, interdisciplinary chronic pain program, referral practices, pediatric, diagnostic investigations, significant clinical indicators, red flags

Citation: Greenough M, Bucknall T, Jibb L, Lewis K, Lamontagne C and Squires JE (2022) Attaining expert consensus on diagnostic expectations of primary chronic pain diagnoses for patients referred to interdisciplinary pediatric chronic pain programs: A delphi study with pediatric chronic pain physicians and advanced practice nurses. Front. Pain Res. 3:1001028. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2022.1001028

Received: 22 July 2022; Accepted: 24 August 2022;

Published: 12 September 2022.

Edited by:

Tiina Jaaniste, Sydney Children’s Hospital, AustraliaReviewed by:

Rui Li, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, United States© 2022 Greenough, Bucknall, Jibb, Lewis, Lamontagne and Squires. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Megan Greenough TUdyZWVub3VnaEBjaGVvLm9uLmNh, bWdyZWUwNDhAdW90dGF3YS5jYQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Pediatric Pain, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pain Research

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.