94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 24 February 2025

Sec. Gastrointestinal Cancers: Hepato Pancreatic Biliary Cancers

Volume 15 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1547054

This article is part of the Research Topic Liver Cancer Awareness Month 2024: Current Progress and Future Prospects on Advances in Primary Liver Cancer Investigation and Treatment View all 17 articles

Background: The optimal treatment strategy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (rHCC) remains unclear. This study is based on cases of rHCC after liver resection, aiming to evaluate the influence of preoperative risk factors on the long-term prognosis of patients with rHCC by comparing patients who underwent salvage liver transplantation (SLT) with those who underwent repeat hepatectomy (RH).

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 401 consecutive patients with rHCC who underwent SLT or RH between March 2015 and December 2022. Next, we performed propensity score matching, subgroup analyses, and both univariate and multivariate analyses. In addition, Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate the overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) after recurrence.

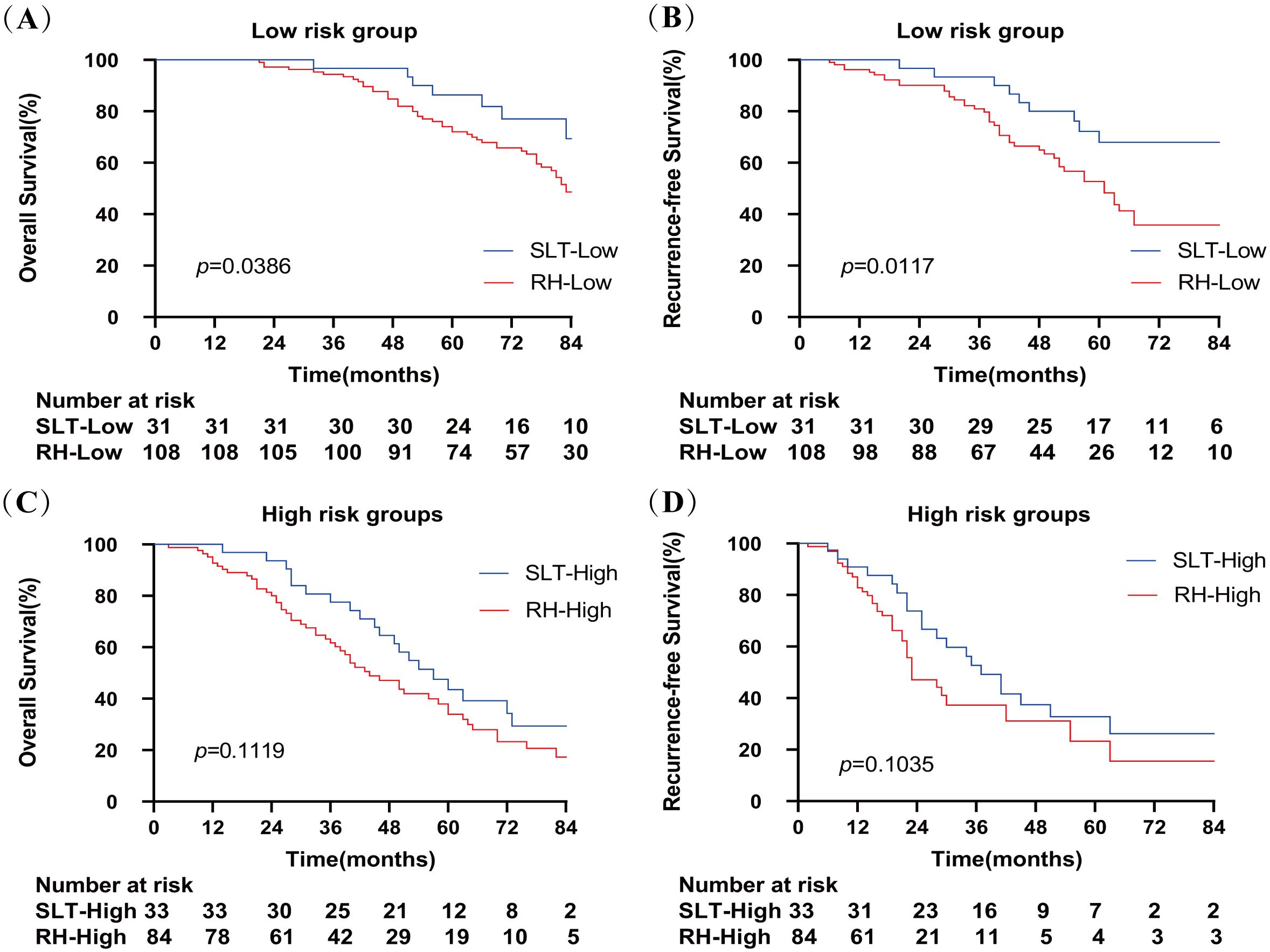

Results: The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and RFS rates in the SLT group were significantly higher than those in the RH group (p=0.0131 and p=0.0010, respectively), and similar results were observed after propensity score matching. In the presence of zero or one risk factors, the OS and RFS in the SLT group were significantly better than those in the RH group (p=0.0386 and p=0.0117, respectively). However, in the presence of two to four risk factors, no significant differences in OS or RFS were detected between the two groups (p=0.1119 and p=0.1035, respectively).

Conclusion: Our analysis identified a number of risk factors that were strongly correlated with a long term prognosis for patients with rHCC who underwent SLT and RH: multiple tumors, a maximum tumor diameter ≥5 cm, microvascular invasion, and a recurrence time ≤2 years. Our findings provide important reference guidelines for organ allocation and clinical decision-making.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies, accounting for 90% of all primary liver cancers and representing the predominant pathological type (1, 2). Globally, HCC is the third leading cause of all cancer-related deaths and primarily affects patients with chronic liver disease; furthermore, the incidence of HCC is increasing on an annual basis (2, 3). Liver transplantation (LT) and liver resection (LR) are the primary curative treatment options for HCC. Theoretically, LT represents the optimal treatment for HCC as it removes both the tumor and underlying liver disease, yielding a 5-year postoperative survival rate of 75% and a recurrence rate of 20% (4, 5). However, owing to donor shortages and the risk of tumor progression, LR is more commonly performed and has become the mainstay treatment for HCC, particularly for patients with early stage disease who meet specific criteria (6, 7). LR can significantly extend survival in patients with early stage HCC, with a 5-year survival rate of 50% but a high recurrence rate of 70% (8–10). The application of LR is also increasing in patients with advanced HCC, localized lesions, and preserved liver function (11). Nevertheless, owing to the chronic liver disease and cirrhotic background of patients with HCC, approximately 80% of cases experience intrahepatic recurrence following surgery, with typically smaller recurrent tumors than primary tumors (7, 12, 13).

The treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (rHCC) is crucial because of the high recurrence rate following LR. The current primary curative treatments for rHCC include salvage liver transplantation (SLT), repeat hepatectomy (RH), and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). SLT has been proposed as a strategy to conserve liver resources and mitigate the risks of transplantation. SLT refers to the treatment strategy of LT when liver cancer relapses or liver failure occurs after hepatectomy, which may alleviate the shortage of donors and expand the treatment opportunities for patients on the waiting list (14). However, significant variations in the long-term survival outcomes of patients following SLT have been observed among patients meeting the Milan criteria across regions such as Asia and Europe; furthermore, these variations have been recorded in subgroups based on the timing of tumor recurrence, the levels of alpha-fetoprotein, and the status of liver injury (15–17). While RH is frequently used to treat rHCC, this technique is limited by a range of factors, including a small residual liver volume, an inadequate reserve of liver functionality, multiple recurrences, and abdominal adhesions (18, 19). RFA, as a localized form of treatment, offers a level of efficacy similar to that of RH, while preserving liver function (20).

Currently, there are no standardized guidelines for the application of SLT, and survival outcomes vary significantly across different research centers, resulting in the usage of donor livers. In the present study, we aimed to identify the prognostic risk factors that influence survival in patients undergoing SLT based on the initial surgical approach and the specific clinicopathological features of rHCC recurrence, evaluate the suitability of SLT as a clinical procedure, and provide clinical guidance for optimizing liver allocation policies.

This retrospective study included patients with rHCC who underwent SLT or RH at the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Transplant Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, between March 2015 and December 2022.All participants were over 18 years old and had a pathological diagnosis of HCC, meeting the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) criteria: a single tumor with a maximum diameter of ≤6.5 cm; ≤3 tumors, each with a diameter of ≤4.5 cm, and a total diameter ≤8 cm; no major vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis. Before RH, the patient did not receive anti-tumor therapy; during the waiting period for SLT, some patients received interventional embolization, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. After RH and SLT, some patients received interventional embolization, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Exclusion criteria included significant comorbidities at the time of recurrence (such as heart, lung, or liver/kidney failure) or loss of surgical opportunity due to tumor progression. All SLT were from cadaveric donors. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and cirrhosis etiology. Tumor characteristics, including size, number, major vascular invasion, and distant metastasis, were assessed preoperatively by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), whereas hepatic blood flow was evaluated by ultrasonography. Tumor histological type, grade, and invasion depth were assessed by pathological examination. Liver function was evaluated by the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, Child-Pugh score, serological tests, and the indocyanine green (ICG) test. Patients with severe diseases of the heart, lungs, brain, or kidneys, as well as those with extrahepatic tumor metastasis, were excluded. Patients classified as Child-Pugh grade A, or those restored to grade A following treatment, were eligible for RH if the 15-minute ICG test results were normal and the predicted residual liver volume exceeded 30%. SLT was selected for patients who met the UCSF criteria and had been evaluated by the MELD score (MELD >18: high risk; 15–18: medium risk; ≤14: low risk).

The clinical diagnosis of HCC, both at the initial and recurrent stages, was considered to be reliable if a given patient met the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases criteria, was confirmed by histopathology, and the diagnosis aligned with CT and MRI findings. Suspected lesions were biopsied under ultrasonographic guidance. Overall survival (OS) is defined as the time from the RH or SLT to the patient’s death or the end of the follow-up period. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from treatment for rHCC to the date of recurrence.

Owing to the high recurrence rate of HCC following LR, patients were followed-up every 3 months during the first year after discharge, bi-weekly from 3–6 months, and monthly thereafter. Follow-up assessments included blood tests, liver and kidney function evaluations, tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein and abnormal prothrombin levels), and ultrasound examinations. CT and MRI scans were conducted every 3 months during the first year and subsequently every 3–6 months. Patients were readmitted for tumor recurrence, liver dysfunction, or other emergencies, as required. The study endpoint was defined as loss to follow-up, death, or by the final date of the study (December 31, 2022).

Continuous variables are expressed as median (range), while categorical variables are presented as percentages. The significance of differences between continuous variables was determined using Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, while categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The 5-year OS was the primary endpoint, and the 5-year RFS was the secondary endpoint. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to generate survival estimates, and the log-rank test was applied for comparisons. Univariate Cox regression analysis identified relevant factors, and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Multivariate analysis included variables that were significant in univariate analysis (p < 0.05). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data analysis was performed using SPSS (version 26.0) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.5).To minimize confounding biases between the SLT and RH groups (including age, gender, hepatitis background, liver function index, platelet count, international normalized ratio, Child-Pugh classification, etc.), propensity score matching (PSM, caliper value 0.02) was performed using a 1:3 matching ratio with R software (version 4.41). The standardized mean differences (SMD) before and afterPSM were calculated to measure balance between groups.

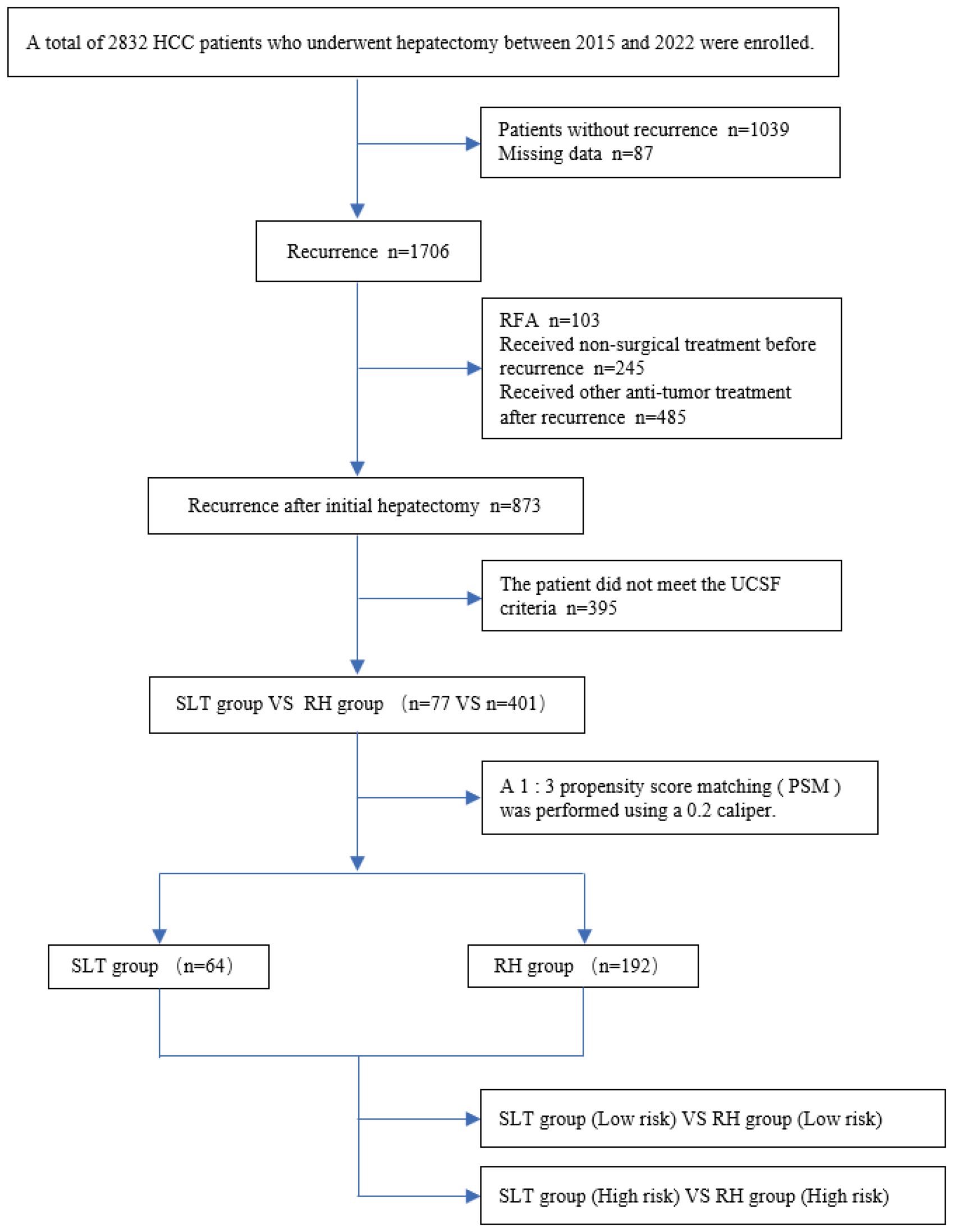

Figure 1 presents a flowchart describing this study. Between 2015 and 2022, a total of 2,832 patients with HCC underwent liver resection at the West China Hospital. During follow-up, 1,039 patients (36.7%) did not experience tumor recurrence, 36 (3.1%) were lost to follow-up, and 1,706 (60.2%) experienced recurrence. Of the patients experiencing recurrence, 103 underwent RFA, 245 received non-surgical treatment prior to recurrence, and 485 received other antitumor therapies post-recurrence. We excluded 395 patients who did not meet the UCSF criteria. Therefore, a total of 478 patients were included in our final analysis, and 1:3 PSM (with a caliper of 0.2) was conducted, yielding 256 eligible patients.

Figure 1. Flow chart depicting the study. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SLT, salvage liver transplantation; RH, repeated hepatectomy.

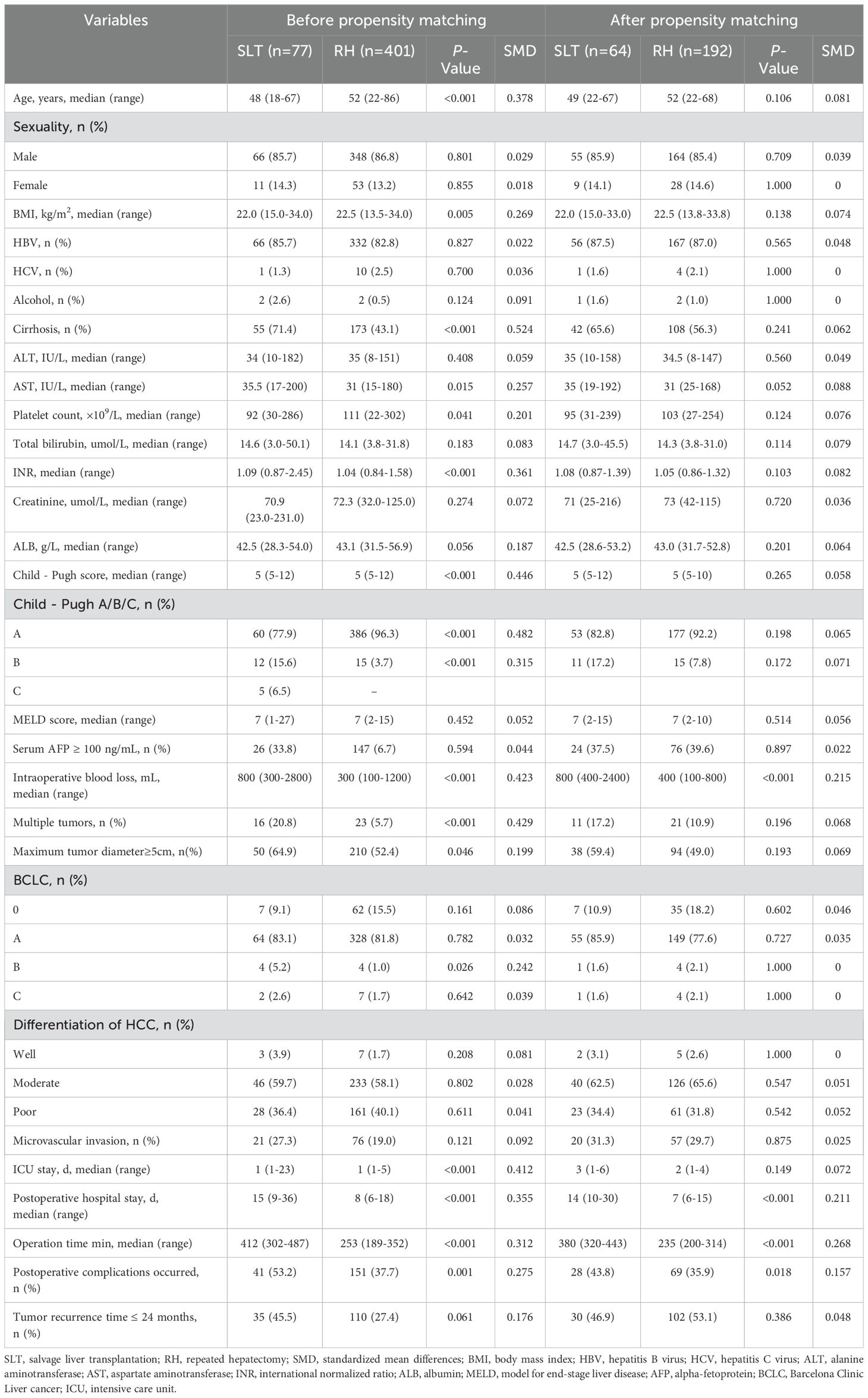

Table 1 summarizes the basic demographic characteristics of the patients, laboratory parameters, and the histological and gross features of the tumors before and after PSM. Prior to PSM, the SLT group featured 77 patients (85.7% male, 14.3% female) with a median age of 48 years (range 18–67 years) and a median BMI of 22.0 kg/m² (range 15.0–34.0), The waiting time of the SLT group was 1-53 months, with an average waiting time of 30 months. The RH group featured 401 patients (86.8% male, 13.2% female) with a median age of 52 years (range 22–86 years) and a median BMI of 22.5 kg/m² (range 13.5–34.0). Significant differences were identified between the two groups in terms of hepatitis background, liver function parameters, platelet count, international normalized ratio, Child-Pugh classification, tumor number, and maximum tumor diameter (p <0.05). The SMD of the variables in the PSM is reduced to below 0.1, indicating that there is a good balance between the two groups. Following PSM, no significant differences were detected between the two groups, thereby enhancing data comparability. Compared with the RH group, the SLT group had more intraoperative blood loss, longer postoperative hospital stay, longer operation time, and more postoperative complications.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and clinicopathological features of patients before and after propensity score matching.

There were no significant differences between the SLT and RH groups in terms of hepatitis background, serum AFP levels (≥100 ng/mL), Child-Pugh classification, Barcelona Clinic Liver cancer (BCLC) staging, differentiation grade, microvascular invasion, tumor number, or maximum tumor diameter (p >0.05; Table 2). This indicated comparable postoperative outcomes between the two groups.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics and clinicopathological features of patients at the time of initial resection.

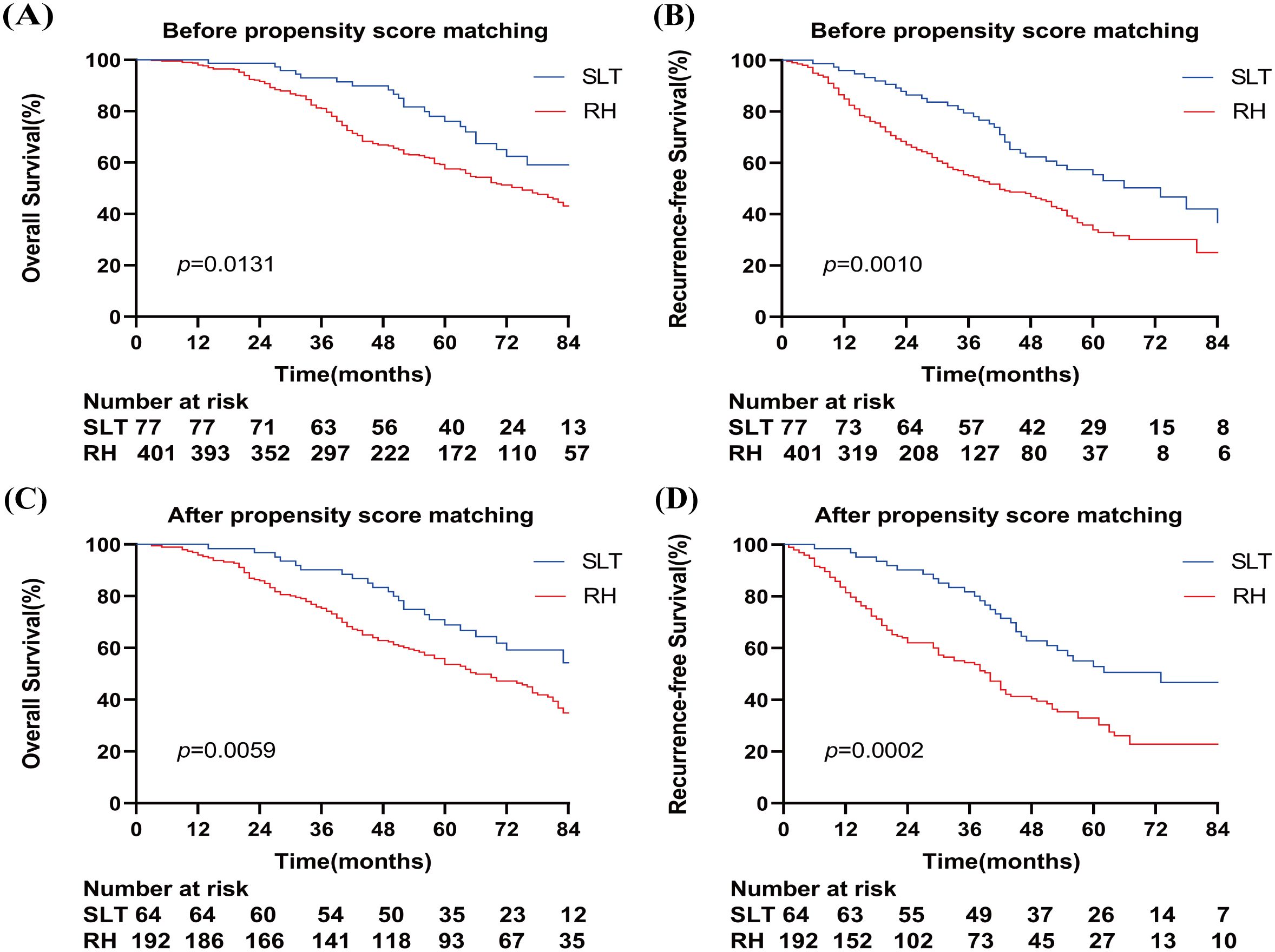

The median survival time after recurrence in patients who underwent SLT and RH was 94 and 75 months, respectively. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates in the SLT group were 100%, 93.0%, and 76.1%, respectively, compared with 98.0%, 81.0%, and 57.6% in the RH group, respectively (p = 0.0131) (Figure 2A). The median recurrence time was 73 and 42 months in the SLT and RH groups, respectively. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates were 96.0%, 79.4%, and 55.4% in the SLT group and 84.9%, 54.9%, and 33.9% in the RH group, respectively (p = 0.0010; Figure 2B), indicating significant differences between the two groups in terms of OS and RFS.

Figure 2. Overall survival (A) and relapse-free survival (B) of patients who received SLT or RH prior to propensity score matching. Overall survival (C) and recurrence-free survival (D) of patients who received SLT or RH after propensity score matching. SLT, salvage liver transplantation; RH, repeated hepatectomy.

After PSM, the median survival times in the SLT and RH groups were 86 and 66 months, respectively. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates in the SLT group were 100%, 90.2%, and 68.9%, respectively, compared with 95.8%, 75.3%, and 53.6% in the RH group, respectively (p = 0.0059) (Figure 2C). The median recurrence time was 73 months for SLT and 40 months for RH, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates of 98.4%, 81.7%, and 53.9% in the SLT group, and 81.4%, 54.4%, and 30.3% in the RH group, respectively (p = 0.0002) (Figure 2D). These results indicate significant differences between the two groups in terms of OS and RFS.

Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that cirrhosis(HR: 1.785, 95% CI: 1.254-2.541, p=0.001), Child-Pugh grade B/C(HR: 2.496, 95% CI: 1.619-3.851, p<0.001), serum AFP levels ≥100 ng/mL(HR: 1.484, 95% CI: 1.049-2.099, p=0.026), multiple tumors(HR: 1.942, 95% CI: 1.249-3.018, p=0.003), maximum tumor diameter ≥5 cm(HR: 1.659, 95% CI: 1.188-2.318, p=0.003), BCLC stage B/C(HR: 1.962, 95% CI: 2.180-16.308, p=0.001), Poor differentiation of HCC(HR: 1.941, 95% CI: 1.380-2.730, p<0.001), microvascular invasion(HR: 3.828, 95% CI: 2.709-5.407, p<0.001), Tumor recurrence time ≤ 24 months(HR:3.571, 95% CI: 2.520-5.060, p<0.001), and Operative method (RH)(HR: 2.034, 95% CI: 1.512-2.738, p=0.006) were significantly linked to a poor prognosis (p <0.05; Table 3). Multivariate analysis identified multiple tumors (HR: 1.745, 95% CI: 1.054–2.891, p=0.031), maximum tumor diameter ≥5 cm (HR: 1.520, 95% CI: 1.050–2.200, p=0.027), microvascular invasion (HR: 2.697, 95% CI: 1.785–4.073, p <0.001), Tumor recurrence time ≤ 24 months (HR: 2.311, 95% CI: 1.532–3.485, p <0.001), and Operative method (RH) (HR: 1.611, 95% CI: 1.281–2.233, p=0.034) as independent risk factors. Using patients who did not undergo repeat liver resection as a reference, undergoing repeat liver resection was identified as an independent risk factor.

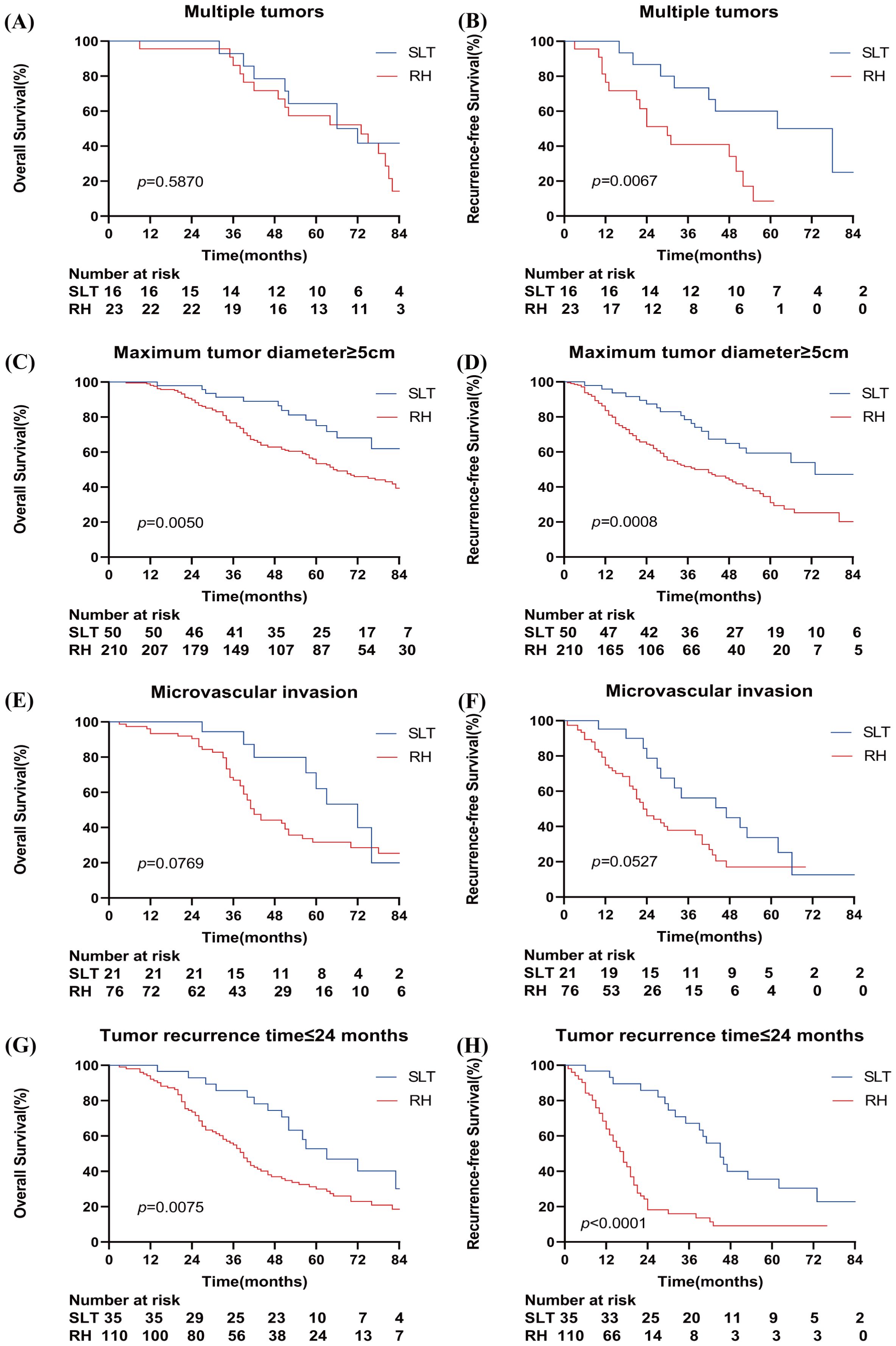

Subgroup analysis revealed that there were no significant differences in the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates between the SLT and RH groups in patients with multiple tumors (100%, 92.9%, and 64.3% vs. 95.7%, 86.1%, and 57.4%, respectively; p=0.5870) (Figure 3A). In patients with a maximum tumor diameter ≥5 cm, the SLT group demonstrated significantly higher OS rates than the RH group (100%, 91.4%, and 75.1% vs. 98.1%, 76.7%, and 53.4%, respectively; p=0.0050) (Figure 3C). No significant differences were observed in terms of OS rates between the SLT and RH groups for patients with microvascular invasion (100%, 94.4%, and 62.2% vs. 93.4%, 66.7%, and 31.7%, respectively; p=0.0769) (Figure 3E). In patients with a recurrence time ≤2 years, the SLT group had significantly higher OS rates than the RH group (100%, 85.7%, and 52.8% vs 92.2%, 55.0%, and 30.0%; p=0.0075) (Figure 3G).

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival and recurrence-free survival in the study cohort when stratified by multiple tumors (A, B), a total tumor length ≥5 cm (C, D), microvascular invasion (E, F), and a tumor recurrence time ≤24 months (G, H). SLT, salvage liver transplantation; RH, repeated hepatectomy.

When considering patients with multiple tumors, the SLT group exhibited significantly higher RFS rates than the RH group (100%, 73.3%, and 60.0% vs. 76.5%, 41.0%, and 8.6%, respectively; p=0.0067) (Figure 3B). The SLT group had significantly higher RFS rates than the RH group in patients with a maximum tumor diameter ≥5 cm (95.9%, 78.5%, and 59.4% vs 83.6%, 51.6%, and 31.1%; p=0.0008) (Figure 3D). No significant differences in RFS rates were detected between the SLT and RH groups in patients with microvascular invasion (95.2%, 56.2%, and 33.7% vs. 74.8%, 37.9%, and 17.1%, respectively; p=0.0527) (Figure 3F). In patients with a recurrence time ≤2 years, the SLT group demonstrated significantly higher RFS rates than the RH group (96.7%, 67.1%, and 35.5% vs 64.0%, 15.9%, and 9.1%; p<0.0001) (Figure 3H).

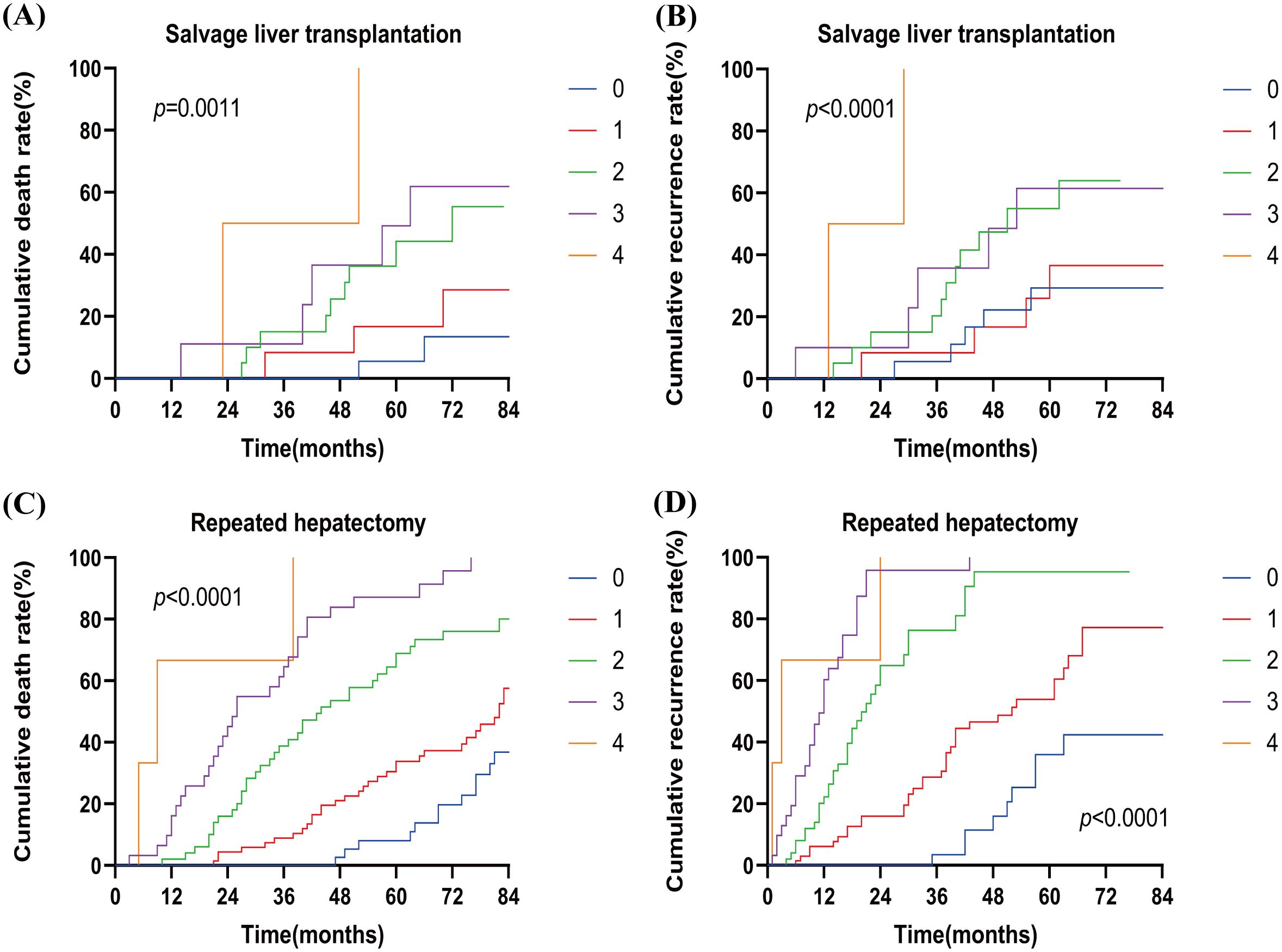

As shown in Figure 4, in the SLT group, the cumulative mortality and recurrence rates were significantly higher when two risk factors (n=2) were present compared to one risk factor (n=1). However, there was no significant increase in cumulative mortality and recurrence rates between 0 and 1 risk factors (n=0, n=1). Similarly, no significant increase in cumulative mortality and recurrence rates was observed between 2 and 4 risk factors (n=2, n=3, n=4).In the RH group, cumulative mortality and recurrence rates increased progressively with the number of risk factors.

Figure 4. Cumulative death rate (A) and cumulative recurrence rate (B) of patients with different numbers of risk factors in SLT. Cumulative death rate (C) and cumulative recurrence rate (D) for patients with different numbers of risk factors in RH. SLT, salvage liver transplantation; RH, repeated hepatectomy; 0–4, the number of risk factors.

Next, we defined zero and one risk factor as a low-risk group and two to four risk factors as a high-risk group. Figure 5 shows that SLT patients had significantly higher OS rates than RH patients in the low-risk group (100%, 96.7%, and 86.4% vs. 100%, 94.4%, and 72.0%, respectively; p=0.0386). In the high-risk group, OS rates were comparable between the SLT and RH groups (100%, 77.5%, and 43.5% vs. 92.7%, 61.7%, and 33.9%, respectively; p=0.1119). In the low-risk group, patients with SLT exhibited significantly higher RFS rates than RH patients (100%, 83.6%, and 40.3% vs. 89.5%, 53.7%, and 16.1%, respectively; p=0.0117). In the high-risk group, RFS rates were comparable between the SLT and RH groups (90.9%, 52.7%, and 32.8% vs. 82.8%, 37.3%, and 23.3%, respectively; p =0.1035).

Figure 5. Overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) of patients receiving SLT or RH in the low-risk group. Overall survival (C) and recurrence-free survival (D) of patients receiving SLT or RH in the high-risk group. SLT, salvage liver transplantation; RH, repeated hepatectomy.

SLT and RH are currently considered as effective treatments for patients with rHCC (21–23). While SLT provides longer survival and lower recurrence rates when compared to RH, its clinical application is constrained by donor shortages, the risk of tumor progression resulting in dropout from waiting lists, and strict transplant criteria (7, 15). To optimize donor resource utilization and prevent unnecessary wastage, the choice between SLT and RH for rHCC should consider patient demographic characteristics, laboratory parameters, and tumor pathological staging prior to recurrence.

When considering patients with rHCC who met the UCSF criteria, we found that the SLT group had a 5-year OS of 76.1%, a 5-year RFS of 55.4%, a median survival of 94 months, and a median recurrence interval of 73 months. In comparison, the RH group had a 5-year OS of 57.6%, a 5-year RFS of 33.9%, a median survival of 75 months, and a median recurrence interval of 42 months (Figure 2A). Thus, the SLT group exhibited longer survival and lower recurrence rates; these findings were consistent with those reported by Fang et al. (5-year OS, 77.1%; RFS, 81.2% in the SLT group; 5-year OS, 55.6%; and RFS, 36.9% in the RH group) (24). Similarly, previous studies confirmed that SLT outperformed RH (15, 16, 25, 26). These previous studies primarily involved patients with rHCC who met the Milan criteria and initially underwent LR or RFA. Our present study extended these findings to the UCSF criteria, thus broadening transplantation opportunities for a wider range of patients.

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis further identified tumor number, maximum tumor diameter, microvascular invasion, and recurrence time, as independent risk factors for survival and recurrence. Multiple nodules and large tumors are frequently associated with highly invasive biological behaviors and an elevated risk of tumor progression in HCC (11). RFA is known to achieve favorable survival outcomes when the number of tumors is ≤3, the maximum tumor diameter is < 5 cm, and there is no microvascular invasion (20). Research has shown that in liver cancer patients, when the tumor diameter exceeds 5 cm, the degree of tumor invasion, survival time, and risk of recurrence significantly increase, and the likelihood of metastasis is also higher (27). In a previous study, Tsilimigras et al. demonstrated that the Tumor Burden Score (TBS, defined as the combination of tumor number and maximum tumor diameter) was able to predict the prognosis of patients with HCC undergoing LR, both within and beyond the Milan criteria (28). In another study, Moris et al. confirmed that the TBS could predict the prognosis of patients with HCC undergoing LT beyond the Milan criteria (29). Our present study utilized the UCSF criteria and yielded similar results, thus demonstrating the significant impact of tumor number and maximum tumor diameter on prognosis.

Microvascular invasion is known to exert a significant impact on both survival and recurrence in patients with HCC (30, 31). Previously, Lei et al. demonstrated that tumor number and maximum diameter represent key predictors for the risk of microvascular invasion (32). Similarly, in the present study, we found that patients with rHCC with microvascular invasion had a poorer prognosis, and that both tumor number and maximum diameter represented significant prognostic factors.

Choi et al. demonstrated that the timing of HCC recurrence after surgery significantly influenced survival, with early recurrence linked to poorer outcomes (33). Studies by Hu et al. and Lee et al. further support this conclusion (34, 35). In the present study, we identified a median recurrence time of 26 months (for the SLT group) and 23 months (for the RH group), with two years as a cut-off value, thus indicating a poor prognosis for patients who experience recurrence within two years. This finding aligns with previous studies that defined early recurrence as occurring within 2 years (36). Therefore, treatment strategies for the early recurrence of HCC should be carefully evaluated.

Based on Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, we stratified patients into low-risk (zero to one risk factor) and high-risk (two to four risk factors) groups. Low-risk patients who underwent SLT exhibited significantly higher OS and RFS rates than those who underwent RH (Figure 5). In contrast, when considering the high-risk patients, there was no significant difference in OS or RFS between those who underwent SLT and those who underwent RH. Thus, we recommend RH as the preferred option when two or more risk factors are present, and SLT for patients with zero to one risk factors to optimize donor use. At the same time, the difficulty of the SLT procedure and its impact on postoperative prognosis should also be taken into account.

The MELD score is widely used to evaluate the severity of liver disease and guide the allocation of organs. Furthermore, the MELD score possesses significant clinical value for predicting patient outcomes following organ transplantation. However, the MELD score has certain limitations (37). In that it benefits patients with more severe conditions but can increase early post-transplant mortality, potentially leading to organ wastage. Therefore, developing an organ allocation system based on more comprehensive evidence could enable stricter outcome evaluation and reduce unnecessary organ waste (38). In addition, several studies reported that factors such as time to recurrence after LR, as well as tumor size and number, could exert significant effects on patient prognosis (39–41). These findings are consistent with those of the present study. When considering patients with rHCC who met the UCSF criteria and underwent SLT after recurrence, we observed that those with multiple high-risk factors had similar outcomes regardless of whether they received SLT or RH. Therefore, we recommend that clinicians should consider these specific risk factors for organ allocation in patients with rHCC awaiting transplantation.

This study had certain limitations. First, as a retrospective study based in a single-center, there was potential for selection bias. Furthermore, the study population, consisting entirely of Chinese patients, may have introduced geographical variability. Second, as a non-randomized controlled study, and despite the use of PSM to reduce inter-group bias, some differences may have remained in the data when comparing between surgical options. Third, this study may have overlooked certain confounding factors related to prognosis. Finally, we did not statistically analyze postoperative treatment plans, potentially affecting our final results.

In conclusion, when performing SLT for rHCC, factors such as the number of tumors, maximum tumor diameter, microvascular invasion, and time to recurrence should be considered as risk factors. For patients with 0-1 risk factors, SLT is likely to yield better therapeutic outcomes compared to RH. However, for patients with 2-4 risk factors, RH may provide similar treatment outcomes to SLT. This conclusion could be beneficial for optimizing donor organ allocation.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the West China Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

LY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DD: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. JL: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LX: Writing – review & editing. PY: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82300737).

The authors would like to acknowledge TCGA, GSEA, and GEPIA2 databases, which were used free of charge. They would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ganesan P, Kulik LM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: new developments. Clinics liver disease. (2023) 27:85–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2022.08.004

2. Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J hepatol. (2006) 45:529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013

3. Kokudo N, Takemura N, Hasegawa K, Takayama T, Kubo S, Shimada M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma: The Japan Society of Hepatology 2017 (4th JSH-HCC guidelines) 2019 update. Hepatol Res. (2019) 49:1109–13. doi: 10.1111/hepr.v49.10

4. Ekpanyapong S, Philips N, Loza BL, Abt P, Furth EE, Tondon R, et al. Predictors, presentation, and treatment outcomes of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: A large single center experience. J Clin Exp Hepatol. (2020) 10:304–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.11.003

5. Sutcliffe R, Maguire D, Portmann B, Rela M, Heaton N. Selection of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma for liver transplantation. Br J surgery. (2006) 93:11–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5198

6. Yang YQ, Wen ZY, Liu XY, Ma ZH, Liu YE, Cao XY, et al. Current status and prospect of treatments for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. (2023) 15:129–50. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i2.129

7. Bednarsch J, Czigany Z, Heij LR, Amygdalos I, Heise D, Bruners P, et al. The role of re-resection in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. (2022) 407:2381–91. doi: 10.1007/s00423-022-02545-1

8. Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, Del Gaudio M, Gardini A, Cescon M, et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence. Ann Surg. (2003) 237:536–43. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000059988.22416.F2

9. Cen F, Sun X, Pan Z, Yan Q. Efficacy and prognostic factors of repeated hepatectomy for postoperative intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing initial hepatectomy. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1127122. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1127122

10. Yoh T, Seo S, Taura K, Iguchi K, Ogiso S, Fukumitsu K, et al. Surgery for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: achieving long-term survival. Ann Surg. (2021) 273:792–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003358

11. Li YC, Chen PH, Yeh JH, Hsiao P, Lo GH, Tan T, et al. Clinical outcomes of surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation in very-early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC gastroenterol. (2021) 21:418. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01995-z

12. Zhang X, Li C, Wen T, Peng W, Yan L, Yang J. Outcomes of salvage liver transplantation and re-resection/radiofrequency ablation for intrahepatic recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: A new surgical strategy based on recurrence pattern. Digestive Dis Sci. (2018) 63:502–14. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4861-y

13. Liu J, Zhao J, Gu HAO, Zhu Z. Repeat hepatic resection VS radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. (2022) 31:332–41. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2020.1839775

14. Majno PE, Sarasin FP, Mentha G, Hadengue A. Primary liver resection and salvage transplantation or primary liver transplantation in patients with single, small hepatocellular carcinoma and preserved liver function: an outcome-oriented decision analysis. Hepatol (Baltimore Md). (2000) 31:899–906. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5763

15. Yamashita Y, Yoshida Y, Kurihara T, Itoh S, Harimoto N, Ikegami T, et al. Surgical results for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy: Repeat hepatectomy versus salvage living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. (2015) 21:961–8. doi: 10.1002/lt.24111

16. Zhang X, Li C, Wen T, Peng W, Yan L, Yang J. Treatment for intrahepatic recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: Salvage liver transplantation or re-resection/radiofrequency ablation? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Surg (London England). (2017) 46:178–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.09.001

17. Lim C, Shinkawa H, Hasegawa K, Bhangui P, Salloum C, Gomez Gavara C, et al. Salvage liver transplantation or repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: An intent-to-treat analysis. Liver Transpl. (2017) 23:1553–63. doi: 10.1002/lt.24952

18. Feng Y, Wu H, Huang DQ, Xu C, Zheng H, Maeda M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus repeat resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (≤ 5 cm) after initial curative resection. Eur Radiol. (2020) 30:6357–68. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06990-8

19. Machairas N, Papaconstantinou D, Dorovinis P, Tsilimigras DI, Keramida MD, Kykalos S, et al. Meta-analysis of repeat hepatectomy versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14(21):5398. doi: 10.3390/cancers14215398

20. Peng Z, Wei M, Chen S, Lin M, Jiang C, Mei J, et al. Combined transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation versus hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after initial surgery: a propensity score matching study. Eur Radiol. (2018) 28:3522–31. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5166-4

21. Shimada M, Takenaka K, Taguchi K, Fujiwara Y, Gion T, Kajiyama K, et al. Prognostic factors after repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. (1998) 227:80–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00012

22. Guerrini GP, Gerunda GE, Montalti R, Ballarin R, Cautero N, De Ruvo N, et al. Results of salvage liver transplantation. Liver Int. (2014) 34:e96–e104. doi: 10.1111/liv.2014.34.issue-6

23. Hwang S, Lee SG, Moon DB, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Lee YJ, et al. Salvage living donor liver transplantation after prior liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. (2007) 13:741–6. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1527-6473

24. Fang JZ, Xiang L, Hu YK, Yang Y, Zhu HD, Lu CD. Options for the treatment of intrahepatic recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: Salvage liver transplantation or rehepatectomy? Clin Transplant. (2020) 34:e13831. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13831

25. Yoon YI, Song GW, Lee S, Moon D, Hwang S, Kang WH, et al. Salvage living donor liver transplantation versus repeat liver resection for patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh class A liver cirrhosis: A propensity score-matched comparison. Am J Transplant. (2022) 22:165–76. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16790

26. Chan AC, Chan SC, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Chiu DW, Poon RT, et al. Treatment strategy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: salvage transplantation, repeated resection, or radiofrequency ablation? Liver Transpl. (2013) 19:411–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.23605

27. Liu C, Sun L, Xu J, Zhao Y. Clinical efficacy of postoperative adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization on hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. (2016) 14:100. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0855-z

28. Tsilimigras DI, Moris D, Hyer JM, Bagante F, Sahara K, Moro A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma tumour burden score to stratify prognosis after resection. Br J surgery. (2020) 107:854–64. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11464

29. Moris D, Shaw BI, McElroy L, Barbas AS. Using hepatocellular carcinoma tumor burden score to stratify prognosis after liver transplantation. Cancers (Basel). (2020) 12(11):3372. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113372

30. Toso C, Mentha G, Majno P. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: five steps to prevent recurrence. Am J Transplant. (2011) 11:2031–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03689.x

31. Zhang EL, Cheng Q, Huang ZY, Dong W. Revisiting surgical strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:691354. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.691354

32. Lei Z, Li J, Wu D, Xia Y, Wang Q, Si A, et al. Nomogram for preoperative estimation of microvascular invasion risk in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma within the milan criteria. JAMA surgery. (2016) 151:356–63. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4257

33. Choi GH, Kim DH, Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ, et al. Prognostic factors and optimal treatment strategy for intrahepatic nodular recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. (2008) 15:618–29. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9671-6

34. Hu Z, Zhou J, Li Z, Xiang J, Qian Z, Wu J, et al. Time interval to recurrence as a predictor of overall survival in salvage liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B virus. Surgery. (2015) 157:239–48. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.09.018

35. Lee S, Hyuck David Kwon C, Man Kim J, Joh JW, Woon Paik S, Kim BW, et al. Time of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver resection and alpha-fetoprotein are important prognostic factors for salvage liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. (2014) 20:1057–63. doi: 10.1002/lt.23919

36. Huang Y, Xu L, Huang M, Jiang L, Xu M. Repeat hepatic resection combined with intraoperative radiofrequency ablation versus repeat hepatic resection alone for recurrent and multiple hepatocellular carcinoma patients meeting the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage A: A propensity score-matched analysis. Cancer Med. (2023) 12:9213–27. doi: 10.1002/cam4.v12.8

37. Brown RS Jr., Lake JR. The survival impact of liver transplantation in the MELD era, and the future for organ allocation and distribution. Am J Transplant. (2005) 5:203–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00769.x

38. Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. (2003) 124:91–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50016

39. Shah SA, Cleary SP, Wei AC, Yang I, Taylor BR, Hemming AW, et al. Recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Surgery. (2007) 141:330–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.028

40. Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, Schwartz M, Roayaie S. Recurrence of hepatocellular cancer after resection: patterns, treatments, and prognosis. Ann Surg. (2015) 261:947–55. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000710

Keywords: recurrent hepatocellular, salvage liver transplantation, repeat hepatectomy, survival outcome, prognostic index

Citation: Yang L, Huang Y, Deng D, Liu J, Xu L and Yi P (2025) Efficacy and prognostic impact of preoperative risk factors for salvage liver transplantation and repeat hepatectomy in patients with early-stage recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score-matched analysis. Front. Oncol. 15:1547054. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1547054

Received: 17 December 2024; Accepted: 10 February 2025;

Published: 24 February 2025.

Edited by:

Francisco Tustumi, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Alejandro Serrablo, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, SpainCopyright © 2025 Yang, Huang, Deng, Liu, Xu and Yi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liangliang Xu, cGVybGlnaHQxNDVAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Pengsheng Yi, MTUyMDgyMDcwNzlAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.