94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Oncol. , 06 February 2025

Sec. Thoracic Oncology

Volume 15 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1470387

This article is part of the Research Topic Genetic and Immunological Insights in Solid Tumors: Comprehensive Approaches to Treatment View all 5 articles

Introduction: Approximately 1−2% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) are positive for rearranged during transfection (RET) gene fusions. The aim of this real-world multi-national study was to describe clinical characteristics, biomarker testing, and treatment patterns of patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC.

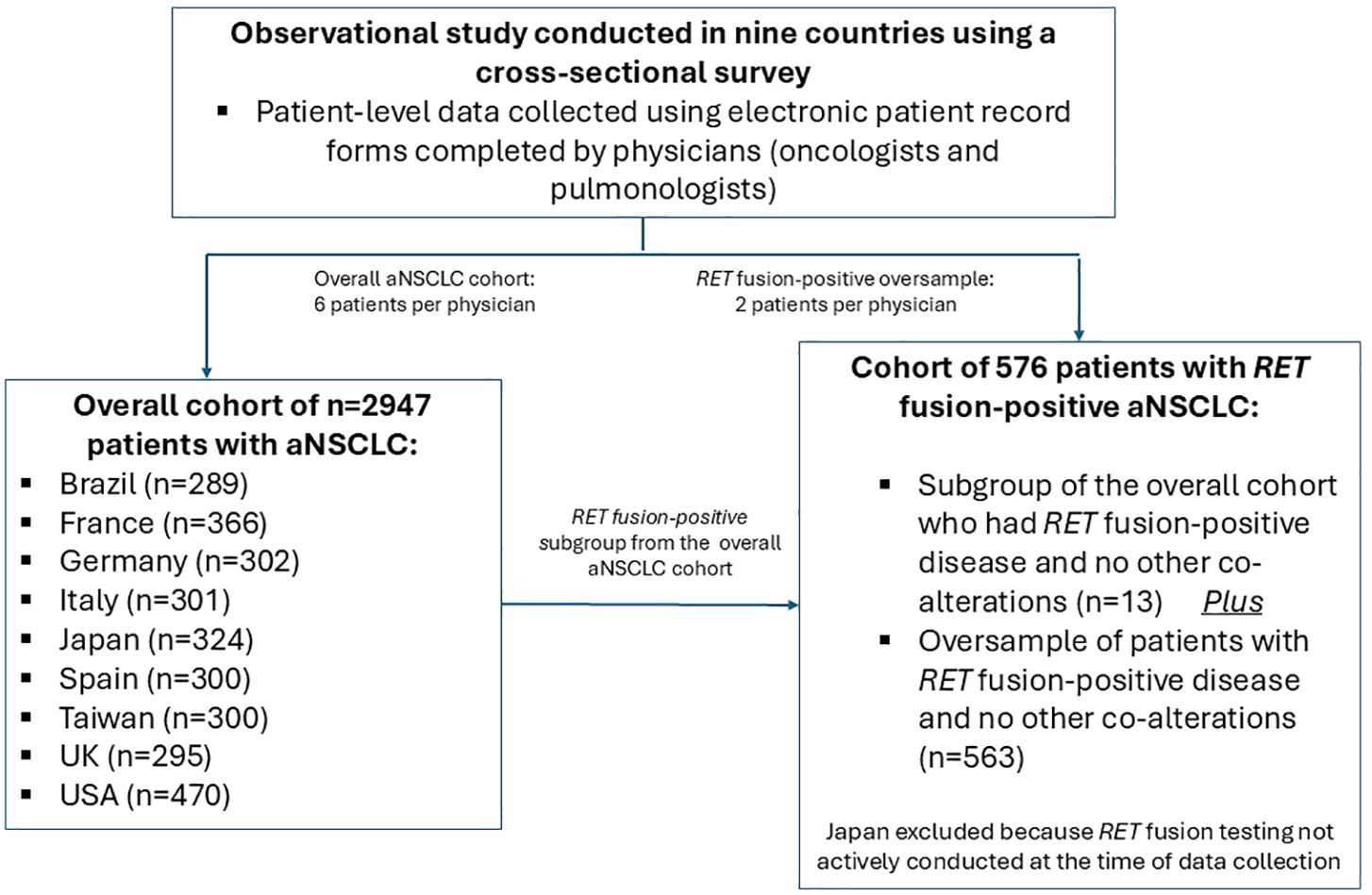

Methods: This observational study was conducted in 2020 in nine countries using electronic patient record forms, following Adelphi Disease Specific Programme (DSP™) methodology. Patients with advanced NSCLC (aNSCLC) were included in the overall cohort. A smaller RET fusion-positive cohort comprised patients from the overall aNSCLC cohort who had RET fusion-positive disease and no other co-alterations, plus an oversample of patients with RET fusion-positive disease and no other co-alterations.

Results: Patient characteristics were generally similar between the overall aNSCLC cohort (n=2947) and the RET fusion-positive cohort (n=576), aside from higher proportions of White/Caucasian patients, never smokers, and adenocarcinoma among the RET fusion-positive cohort. For the overall aNSCLC cohort, 899 (31%) were tested for RET fusions; 84% of RET test results were available prior to initiation of aNSCLC treatment. Comparisons between the two cohorts showed similar proportions of patients treated with chemotherapy (± immunotherapy), but less use of immunotherapy only or targeted therapy in the RET fusion-positive cohort.

Conclusions: Results of this real-world study provide insights into clinical characteristics, biomarker testing, and treatment patterns of patients with RET fusion-positive aNSCLC and highlight the need for awareness and education to increase RET testing with the intent to treat with selective RET inhibitors when appropriate to optimize outcomes for patients.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents approximately 80−90% of all lung cancers (1, 2). Recently, treatment options for patients with advanced NSCLC (aNSCLC) have greatly expanded with the identification of targetable oncogenic driver alterations and the regulatory approval of several targeted therapies. One of these biomarkers is rearranged during transfection (RET) (3). Approximately 1−2% of all NSCLCs are positive for RET gene fusions (4, 5). Targeted treatments for RET fusion-positive aNSCLC include the selective RET kinase inhibitors selpercatinib and pralsetinib (6, 7).

Understanding real-world patient characteristics and treatment patterns, alongside more comprehensive information on biomarker testing, can provide important context for the rapidly evolving landscape of aNSCLC therapy and aid the generalizability of clinical trial data to routine clinical practice. The aim of this real-world multi-national study was to describe the clinical characteristics, biomarker testing, and treatment patterns of patients with RET fusion-positive aNSCLC.

This observational study was conducted from July to December 2020 in nine countries (Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, Taiwan, the UK, and the USA) following Adelphi DSP™ methodology, which involves large, multinational, cross-sectional surveys that collect real-world data from physicians and patients (8). Here, we report on patient-level data using electronic patient record forms (ePRFs) completed by physicians.

Oncologists and pulmonologists (and respiratory surgeons in Japan) were identified using publicly available lists of clinicians in each country. Eligible specialists were responsible for managing patients with aNSCLC and saw at least three patients with a diagnosis of aNSCLC per month. A sample was then randomly selected from willing clinicians meeting the inclusion criteria.

Clinicians completed an online anonymized ePRF based on prior medical records for six consulting eligible patients with aNSCLC who were included in a pseudorandom sample (hereafter referred to as the overall aNSCLC cohort). An additional two patients were part of an oversample of patients with RET fusion-positive aNSCLC and no other co-alterations (hereafter referred to as the RET fusion-positive cohort). This latter cohort also included patients from the overall aNSCLC cohort whose disease was RET fusion-positive with no other co-alterations (Figure 1). Japanese patients were excluded from the RET fusion-positive cohort because RET fusion testing was not actively conducted in Japan at the time. Eligible patients were ≥18 years old, not participating in a clinical trial, and had a diagnosis of aNSCLC.

Figure 1. Schematic flow chart showing study design. aNSCLC, advanced non-small cell lung cancer; RET, rearranged during transfection.

Physicians provided information on patient demographics, clinical characteristics, biomarker testing, and first-line treatment. In particular, the ePRFs captured individual patient data on RET testing, including whether RET testing was conducted, results of RET testing, and whether next-generation sequencing (NGS) was used.

Descriptive statistics are provided for demographics and disease characteristics, using median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and the frequency and percentage within each category for categorical variables. Missing data were excluded from the analysis and no imputation was conducted.

Data collection was in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines (9). Study materials and protocol were reviewed and exempted by the Western Institutional Review Board (study protocol number AG8757) and were in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection (10, 11).

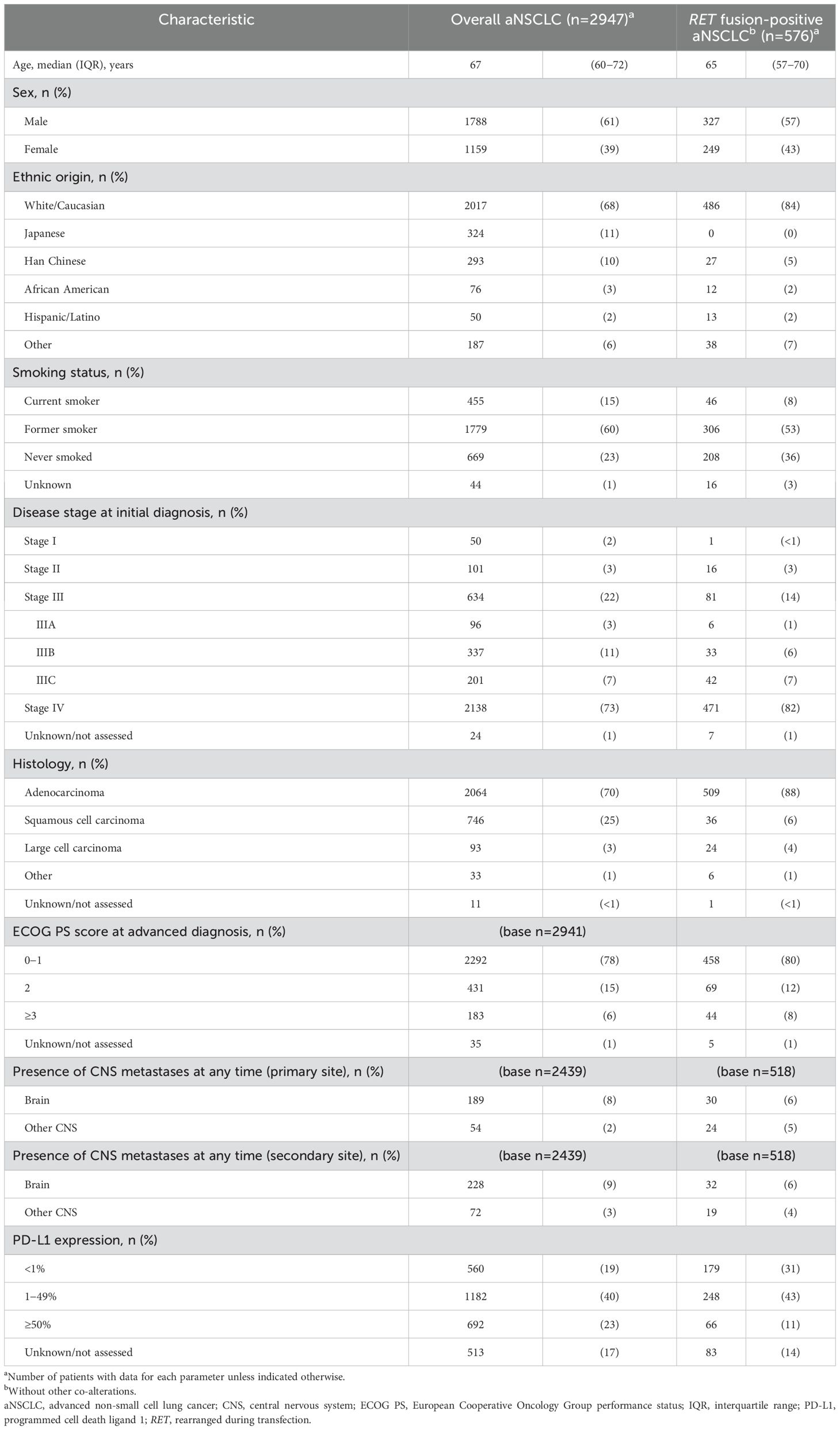

Demographic and clinical characteristic data were available for 2947 patients in the overall aNSCLC cohort and 576 patients in the RET fusion-positive cohort (Table 1). Characteristics were generally similar between these cohorts for most parameters, including median age (67 [IQR 60−72] years vs. 65 [IQR 57−70] years), presence of central nervous system metastases, and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, and with most patients in each cohort being male, having stage IV disease and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0−1 (Table 1). Median age for the overall aNSCLC cohort was similar across the nine countries (data not shown).

Table 1. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics in the overall aNSCLC population and in patients with RET fusion-positive aNSCLC and no other co-alterations.

Although statistical comparisons were not made, there were notable numerical differences between the overall aNSCLC cohort and the RET fusion-positive cohort for some parameters, including higher proportions of White/Caucasian patients (68% vs. 84%), never smokers (23% vs. 36%), and histology of adenocarcinoma (70% vs. 88%), and lower proportion of squamous cell carcinoma (25% vs. 6%), in the RET fusion-positive cohort. All comparisons between cohorts came with a caveat that the RET fusion-positive cohort excluded Japanese patients and included a small number of patients from the overall cohort. In the RET fusion-positive cohort, there was wide variation in the proportion of never smokers across countries, ranging from 24% and 31% in France and the USA, respectively, to 70% in Taiwan (data not shown).

The testing rate for RET gene fusions at diagnosis of advanced disease was 31% (899 of 2947 patients) in the overall aNSCLC cohort, but varied widely across countries, from 8% in Taiwan to 67% in the USA (Table 2). Testing for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations was more consistent across countries, ranging from 73% in Brazil to 90% in Taiwan. In general, the USA had the highest rates of testing across all biomarkers (Table 2). For patients in the overall aNSCLC cohort with available results (n=820), the prevalence of RET gene fusions was 4.8%, but was as high as 26.8% in Brazil. Most patients (77%) had been tested using NGS, and 84% had test results available prior to initiation of treatment for advanced disease (Table 2).

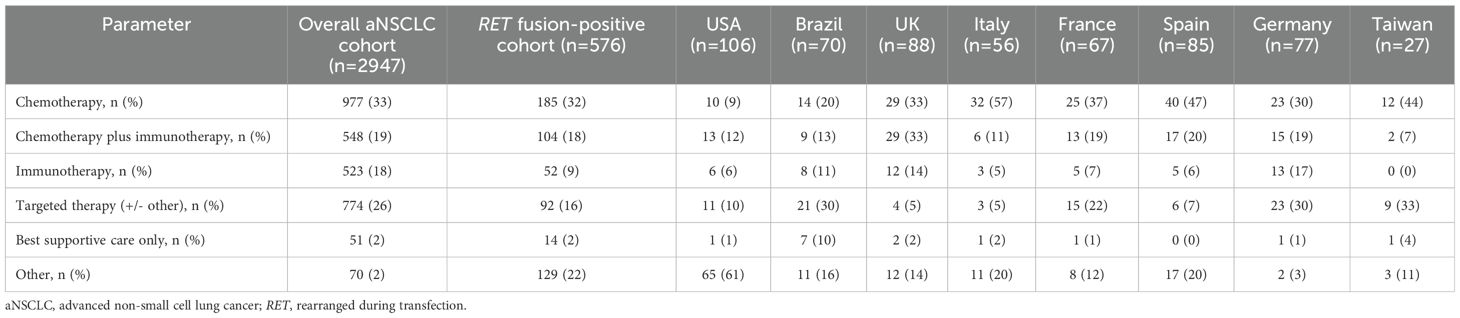

The percentage of patients receiving chemotherapy (33% vs. 32%) or chemotherapy plus immunotherapy (19% vs. 18%) as first-line treatment was very similar between the overall aNSCLC cohort and the RET fusion-positive cohort (Table 3). In the RET fusion-positive cohort, across the eight countries evaluated, chemotherapy was prescribed for 9−57%, and chemotherapy plus immunotherapy for 7−33%, in the first-line setting (Table 3). Compared to the overall aNSCLC cohort, the percentage of patients treated with immunotherapy only (18% vs. 9%) or with targeted therapy (26% vs. 16%) was numerically lower in the RET fusion-positive cohort.

Table 3. First-line drug treatment class among the overall aNSCLC cohort and RET fusion-positive cohort and by country for the RET fusion-positive cohort.

This observational study provides real-world data from nine countries on the clinical characteristics, biomarker testing, and treatment patterns of patients with aNSCLC, focusing on data from patients with RET fusion-positive aNSCLC and no other co-alterations. Demographic and clinical characteristics, such as median age (65 years; IQR 57−70), advanced disease stage at diagnosis, predominantly adenocarcinoma histology, and a relatively high proportion of never smokers among the RET fusion-positive cohort were generally as expected for this patient population (3, 6). However, other studies have reported a preponderance of female patients (12), whereas in our RET fusion-positive cohort, 43% were female.

The RET testing rate of 31% across the nine countries in this study is much lower than those for EGFR and ALK (≈80%), the more established biomarkers for NSCLC. This has various clinical implications. First, RET is an emerging biomarker (13); selective RET inhibitors have been available only for the last 4 years but at the time of writing are still not widely available or reimbursed across all lines of therapy among the countries in this study, including Brazil and Taiwan (no access across any line of therapy) and France and Italy (no access for first-line therapy). As access to selective RET inhibitors expands, we expect testing rates to increase. Second, education and awareness for RET as an actionable biomarker needs to be pursued, as evidence clearly suggests that patients derive benefit when tested for RET and treated, if appropriate, with a selective RET inhibitor in the first-line setting (14). Third, as more actionable biomarkers emerge for NSCLC, broad testing with NGS should become the norm and this will help increase testing rates across the spectrum for all biomarkers. The 4.8% positivity rate for RET fusions in the overall aNSCLC cohort who were tested was somewhat higher than the expected rate of ≈1−2% for RET fusion-positive aNSCLC (4, 5), although the positivity rate was reduced to 2.7% after excluding data from Brazil, which had a positivity rate much higher than any other country (26.8%). The exact reason for this difference is not known.

The proportion of patients treated with first-line chemotherapy or chemotherapy plus immunotherapy was almost the same in both cohorts. However, the use of targeted treatment was numerically lower in the RET fusion-positive cohort than in the overall aNSCLC cohort, possibly because selective RET inhibitors were just becoming available at the time of the study. The use of immunotherapy was also numerically lower in the RET fusion-positive cohort, which appears to be consistent with the lower rate of PD-L1 expression ≥50% in this cohort.

Limitations of this study include its observational design, making it subject to potential biases inherent in non-randomized research, such as selection bias and confounding factors that could influence treatment choices and outcomes. For example, selection of consecutive patients may have resulted in over-representation of patients who consult more frequently. In addition, there may have been potential biases in selecting the RET fusion-positive cohort. This cohort included both a subgroup of patients with RET fusion-positive disease and no other co-alterations from the overall aNSCLC cohort and an oversample of those with RET fusion-positive disease and no other co-alterations, which may not accurately reflect the broader population of RET fusion-positive aNSCLC patients with varying molecular profiles. The retrospective study design using electronic patient records may have provided incomplete or inconsistent data across different sites, potentially affecting the accuracy of clinical information. The study was conducted across nine countries, which may have led to variability in treatment patterns and access to biomarker testing due to differences in healthcare systems, guidelines, and resources. Although 31% of patients in the overall aNSCLC cohort were tested for RET fusions, this may not represent the full patient population, and the availability of RET testing could be limited in some regions or settings, leading to underreporting of RET fusion-positive cases. It is also noteworthy that the study mainly focused on descriptive analysis of clinical characteristics and treatment patterns, rather than directly evaluating the effectiveness of different treatments in the RET fusion-positive cohort. This study was conducted almost 4 years ago and, while we believe the findings are still relevant, a repeat study should be performed to assess the impact of the advancements in diagnostic and treatment paradigms (e.g., availability of selective RET inhibitors) over these years.

In conclusion, this study provides insights into the clinical characteristics, biomarker testing, and treatment patterns of patients with RET fusion-positive aNSCLC and highlights the need for increased RET testing rates, preferably with NGS, with the option to treat with selective RET inhibitors in the event of RET fusion-positive disease.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Study materials and protocol were reviewed and exempted by the Western Institutional Review Board (study protocol number AG8757) and were in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

UK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GS: Writing – review & editing. HB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CF: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. TP: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

The authors would like to acknowledge Greg Plosker and Caroline Spencer (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) and Alan Ó Céilleachair (Global Scientific Communications Associate, Cork, Ireland) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of this manuscript, funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

UK, GS, and TP are all employees of, and minor shareholders in, Eli Lilly and Company. HB and CF are employees of Adelphi Real World, who conducted the survey.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Eli Lilly and Company. The funder was involved in the study design, analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Cancer.org. Key statistics for lung cancer. Available online at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (Accessed November 3, 2023).

2. Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, Novello S, Smit EF, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2018) 29:iv192–237. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy275

3. Choudhury NJ, Drilon A. Decade in review: a new era for RET-rearranged lung cancers. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2020) 9:2571–80. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-346

4. Kohno T, Nakaoku T, Tsuta K, Tsuchihara K, Matsumoto S, Yoh K, et al. Beyond ALK-RET, ROS1 and other oncogene fusions in lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2015) 4:156–64. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.11.11

5. Hess LM, Han Y, Zhu YE, Bhandar NR, Sireci A. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with RET-fusion positive non-small lung cancer in real-world practice in the United States. BMC Cancer. (2021) 21:28. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07714-3

6. Drilon A, Oxnard GR, Tan DSW, Loong HHF, Johnson M, Gainor J, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:813–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005653

7. Griesinger F, Curigliano G, Thomas M, Subbiah V, Baik CS, Dan TSW, et al. Safety and efficacy of pralsetinib in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer including as first-line therapy: update from the ARROW trial. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33:1168–78. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.08.002

8. Anderson P, Higgins V, Courcy J, Doslikova K, Davis VA, Karavali A, et al. Real-world evidence generation from patients, their caregivers and physicians supporting clinical, regulatory and guideline decisions: an update on Disease Specific Programmes. Curr Med Res Opin. (2023) 39:1707–15. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2023.2279679

9. European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association. European pharmaceutical market research association (EphMRA) code of conduct (2019). Available online at: https://www.ephmra.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/EPHMRA%202022%20Code%20of%20Conduct.pdf (Accessed November 3, 2023).

10. US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule (2003). Available online at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf (Accessed November 3, 2023).

11. Health Information Technology. Health information technology act (2009). Available online at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf (Accessed November 3, 2023).

12. Qiu Z, Ye B, Wang K, Zhou P, Zhao S, Li W, et al. Unique genetic characteristics and clinical prognosis of female patients with lung cancer harboring RET fusion gene. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10387. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66883-0

13. de Jager VD, Timens W, Bayle A, Botling J, Brcic L, Büttner R, et al. Developments in predictive biomarker testing and targeted therapy in advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer and their application across European countries. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2024) 38:100838. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100838

Keywords: clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, biomarker testing, RET fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer, real-world data

Citation: Kiiskinen U, Segall G, Bailey H, Forshaw C and Puri T (2025) Characteristics, treatment patterns, and biomarker testing of patients with advanced RET fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer in a real-world multi-country observational study: a brief report. Front. Oncol. 15:1470387. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1470387

Received: 25 July 2024; Accepted: 16 January 2025;

Published: 06 February 2025.

Edited by:

Lin Zhou, Capital Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Eswari Dodagatta-Marri, University of California, San Francisco, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Kiiskinen, Segall, Bailey, Forshaw and Puri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Urpo Kiiskinen, a2lpc2tpbmVuX3VycG9AbGlsbHkuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.