94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 10 March 2025

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 15 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1385304

Background and aims: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) has been combined with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-based systemic therapies for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) with promising efficacy. However, whether the addition of TACE to the combination of ICI and tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) (ICI+TKI+TACE) is superior to ICI+TKI combination therapy is still not clear. Thus, this study compares the efficacy of ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy and ICI+TKI doublet therapy in patients with uHCC.

Methods: uHCC patients treated with either ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy or ICI+TKI doublet therapy were retrospectively recruited between January 2016 and December 2021 at Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital. The patients from ICI+TKI+TACE group and ICI+TKI group were further subjected to propensity score matching (PSM). The primary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and objective response rate (ORR). Post-progression survival (PPS) as well as treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were also assessed.

Results: A total of 120 patients were matched. The median PFS was 8.4 months in ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy group versus 6.6 months in ICI+TKI doublet therapy group (HR 0.72, 95%CI 0.48-1.08; p=0.115). Similar results were obtained in term of OS (26.9 versus 24.2 months, HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.51-1.52; p=0.670). The ORR in the triple therapy group was comparable with that in the doublet therapy group (16.6% versus 21.6%, p=0.487). Further subgroup analysis for PFS illustrated that patients without previous locoregional treatment (preLRT) (10.5 versus 3.7 months, HR 0.35 [0.16-0.76]; p=0.009), without previous treatment (10.5 versus 3.5 months, HR 0.34 [0.14-0.81]; p=0.015) or treated with lenvatinib (14.8 versus 6.9 months, HR 0.52 [0.31-0.87]; p=0.013) can significantly benefit from triple therapy compared with doublet therapy. A remarkable interaction between treatment and preLRT (p=0.049) or TKIs-combined (p=0.005) was also detected in term of PFS. Post progression treatment significantly improved PPS in both groups. The incidence of TRAEs was comparable between two groups.

Conclusions: The addition of TACE to ICI+TKI combination therapy did not result in a substantial improvement in efficacy and prognosis of patients. However, in selected uHCC patients (without preLRT or treated with lenvatinib as combination), ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy may remarkably improve PFS.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer globally and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality (1). Surgical resection is potentially curative for patients with early-stage HCC, but about 50-70% of HCC patients are unfit for surgical resection due to advanced tumor stage (2). For patients with advanced HCC, multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sorafenib and lenvatinib used to be the first line treatment, but the efficacy was modest and only conferred limited survival benefits. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) including anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) monoclonal antibodies have shown encouraging results in multiple cancers (3, 4). The IMbrave150 trial demonstrated a better tumor response and survival with the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab versus sorafenib (5), resulting in the accelerated approval of this combination for advanced HCC, which also started a new tide of clinical studies leading by ICI-based combination therapy in HCC. Among these, the combination of TKI and ICI was also investigated and promising efficacy was reported in the KEYNOTE 524 trial with a median progression‐free survival (PFS) of 9.3 months and a median overall survival (OS) of 22 months for patients treated with pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib (6). But subsequent phase III study LEAP-002 which compared pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib with lenvatinib failed to meet its primary endpoint (7). However, TKIs and their combination with ICIs are still important treatment options for advanced HCC.

On the other hand, although atezolizumab plus bevacizumab is now the preferred first-line therapy for advanced HCC, more than 50% of patients still do not respond to treatment. To further increase the objective response rate (ORR) and improve patient survival, loco-regional treatments (LRTs) including transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiotherapy (RT) and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) have been combined with ICI-based systemic therapies for unresectable HCC (uHCC) (8, 9). TACE, which is the first therapeutic modality to provide survival benefits for patients with uHCC (10), is the standard treatment for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B HCC in western countries (11) and BCLC stage B/C HCC in Asia‐Pacific (12). The results of LAUNCH and TACTICS trial showed that TACE combined with TKI significantly prolonged the survival of HCC patients (13, 14). Mechanistically, the upregulated expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) by TACE (15) could be effectively inhibited by TKIs (16), leading to better clinical outcomes in patients treated with TACE plus TKIs (17). In addition, the potential benefit of TACE plus PD‐1 inhibitor has also been revealed. A retrospective study has reported that TACE can be safely integrated with PD-1 inhibitor and lead to significant delay in tumor progression and disease downstaging in selected patients (18). Meanwhile, TACE with or without lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab is under investigation for intermediate-stage HCC not amenable to curative treatment in phase 3 LEAP-012 study (19). However, currently, whether the addition of TACE to the combination of TKIs and PD-1 inhibitor (ICI+TKI+TACE) is superior to ICI+TKI combination therapy is still not clear. This study leverages a retrospective cohort of HCC patients treated with ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy or ICI+TKI doublet therapy to examine the differences of efficacy and patient outcome between the two regimens.

This retrospective study was conducted on adult patients diagnosed with uHCC at Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Shanghai, China, from January 2016 to December 2021. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital and conducted in strict accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As patient identities were anonymized, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committees.

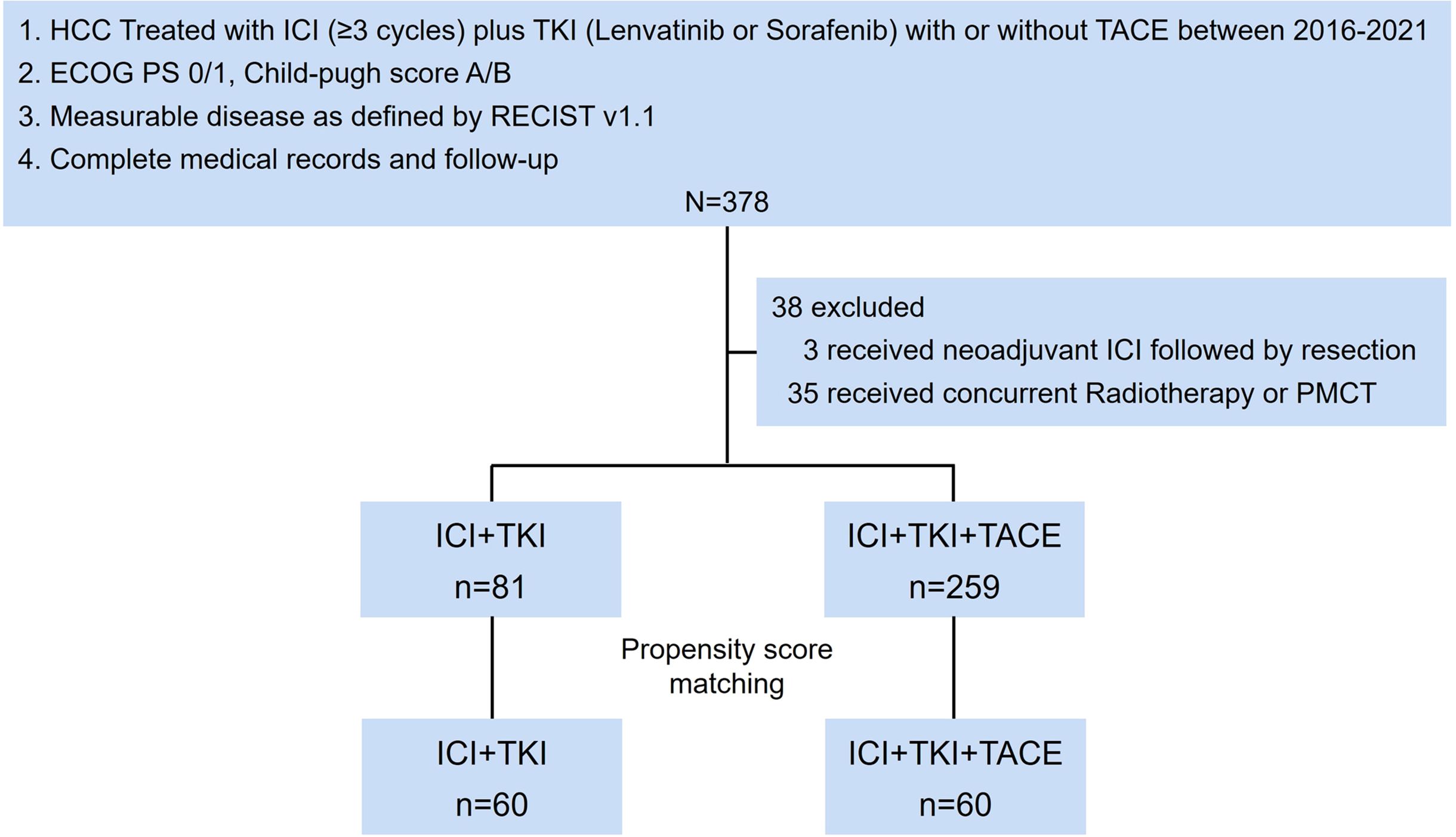

The main inclusion criteria of patients were as follows: (1) Patients with unresectable or metastatic, histologically, or radiographically diagnosed HCC. Patients were classified as unresectable if R0 resection is impossible, or remnant liver volume is below 30% in non-cirrhotic patients or 40% in cirrhotic patients, or tumor stage is BCLC stage B and up-to-seven criteria out (20), or stage C; (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 or 1; (3) preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A or B); (4) measurable disease as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1); (5) complete medical records and follow-up; (6) patients were treated with ICI (anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, ≥3 cycles) plus TKIs (lenvatinib or sorafenib) (ICI+TKI) with or without TACE (Figure 1). TACE was performed within 30 days before or after the start of ICI+TKI, with 15 patients received simultaneous TACE and systemic therapy, 37 patients initiated TACE before systemic therapy (median interval: -5 days, range: -1 to -23 days; 95% CI: -22, -2) and 8 patients started TACE after systemic therapy (median interval: +7.5 days, range: +1 to +16 days; 95% CI: +1, +16). The overall median interval from TACE to systemic therapy was +3 days (TACE was performed 3 days post systemic therapy) (range: -23 to +16 days, 95% CI: -18.5, +9 days). A total of 378 patients were screened for eligibility, and 38 patients were excluded (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Of the 340 patients included, 259 patients received ICI+TKI+TACE triple treatment and 81 received ICI+TKI doublet treatment. Their detailed clinicopathologic features are described in Supplementary Table S1. Propensity score (PS) matching was further performed to match patients from triple treatment and doublet treatment group. The diagram with the flow of patients was shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flowchart. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TKIs, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PMCT, percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy.

The vascular catheter was inserted through a femoral artery using the Seldinger technique to the hepatic artery, then tumor-feeding arteries were identified by angiography, and lipiodol emulsion mixed with doxorubicin hydrochloride or pirarubicin was administered into the tumor-feeding vessels. Subsequently, embolization was performed with the injection of polyvinyl alcohol particles and absorbable gelatin sponge particles until complete arterial flow stasis was observed. The amounts of anticancer agent and lipiodol were adjusted according to the body surface area of the patient and liver function. According to physicians’ assessment, TACE was conducted repeatedly on demand, mainly based on the proportion of active area tumors and status of hepatic function.

The primary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS). The PFS was defined as the time interval between the initiation of TACE or systemic therapy, whichever comes first, and disease progression or death from any cause. The secondary outcomes included overall survival (OS) and objective response rate (ORR). The OS was defined as the time from the initiation of TACE or systemic therapy whichever comes first to death from any cause. The ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete/partial response (CR/PR) as best overall response (BOR) according to RECIST v1.1. Post progression treatments were also recorded. PPS was defined as the time from first progression upon ICI+TKI or ICI+TKI+TACE therapy to death from any cause. Treatment-related adverse events were extracted and reviewed by two physicians from the medical records.

All clinical data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software. Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. The PSM method was applied to balance the patients from triple treatment and doublet treatment group (Supplementary Table S1) using SPSS software PS Matching procedure. The balancing caliper was set at 0.2. Balancing covariates included age, gender, HBV, HCV, ECOG PS, Child-pugh score, previous loco-regional treatment (preLRT), previous TKI treatment (preTKI), First-line treatment, previously untreated, macrovascular invasion (MVI), extrahepatic metastasis, BCLC stage, TKIs-combined, DCP and AFP levels at baseline. After PS matching, 60 of 259 patients treated with ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy were matched to 60 patients who had received ICI+TKI doublet therapy by PSs (Table 1). Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to identify potential risk factors associated with survival. All p values were 2 sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between January 2016 and December 2021, 378 patients with HCC at the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital were screened for eligibility, and 38 patients were excluded (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). A total of 81 patients have received ICI+TKI doublet therapy and 259 patients have received ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy. The baseline characteristics of included patients were listed in Supplementary Table S1. The included patients from ICI+TKI group and ICI+TKI+TACE group were further subjected to PS matching based on the baseline characteristics. Sixty patients from ICI+TKI+TACE group were matched to 60 patients from ICI+TKI group and the baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Table 1). As of December 30, 2021, the median duration of follow-up was 23.9 months (24.2 months for ICI+TKI+TACE group, 23.9 months for ICI+TKI group).

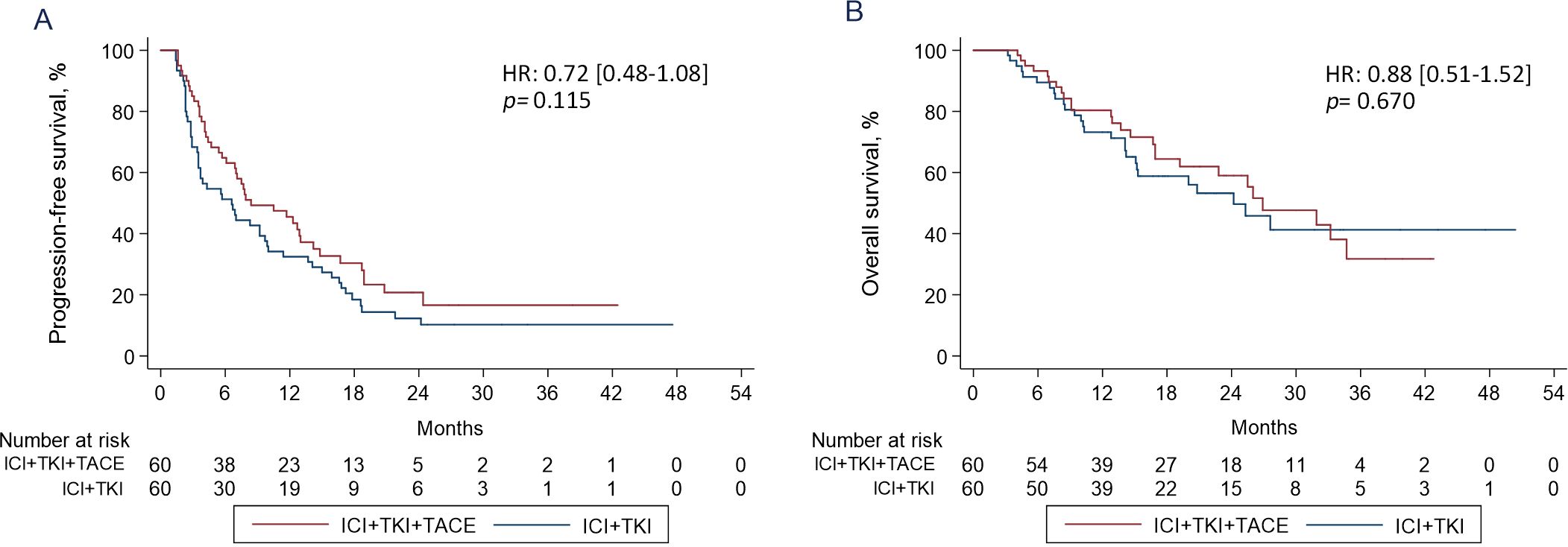

After PSM, the median PFS of patients in ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy group was 8.4 months (95% CI 6.1-13) versus 6.6 months (95% CI 3.5-9.7) in ICI+TKI doublet therapy group (HR 0.72 [0.48-1.08]; p=0.115) (Figure 2A). The median OS of patients in the triple therapy group was also comparable with that in the doublet therapy group (26.9 versus 24.2 months, HR 0.88 [0.51-1.52]; p=0.670); (Figure 2B). Prior to PSM, the PFS (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61-1.09, p=0.185) and OS (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.65-1.22, p=0.453) were comparable between ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy group and ICI+TKI doublet therapy group, which were consistent with the outcomes after PSM (Supplementary Figure S1). Univariate analyses revealed that Child-Pugh score (B versus A, HR 2.18 [1.21-3.91]; p=0.009), macroscopic vascular invasion (MVI) (present versus absent, HR 1.55 [1.01-2.35]; p=0.041), TKIs-combined (lenvatinib versus sorafenib, HR 0.47 [0.30-0.72]; p=0.001) and des-gamma‐carboxy prothrombin (DCP) levels (>400 versus ≤400 mAU/mL, HR 1.71 [1.13-2.57]; p=0.010) were significantly associated with PFS (Supplementary Table S2). Multivariate analysis showed that Child-Pugh score (B versus A, HR 1.84 [1.01-3.37]; p=0.046) and TKIs-combined (lenvatinib versus sorafenib, HR 0.53 [0.34-0.82]; p=0.005) were identified as independent prognostic factors for PFS (Supplementary Table S2). Univariate analysis showed that Child-Pugh score (B versus A, HR 3.68 [1.85-7.31]; p=0.000), MVI (present versus absent, HR 2.85 [1.64-4.94]; p=0.000) and DCP (>400 versus ≤400 mAU/mL, HR 2.12 [1.19-3.78]; p=0.011) were significantly associated with OS (Supplementary Table S3). Child-Pugh score (B versus A, HR 3.11 [1.56-6.22]; p=0.001), MVI (present versus absent, HR 2.54 [1.46-4.43]; p=0.001) and DCP (>400 versus ≤400 mAU/mL, HR 1.90 [1.06-3.40]; p=0.029) were also identified as independent prognostic factors for OS (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS (A) and OS (B) curves in HCC patients treated with ICI+TKI+TACE or ICI+TKI therapy.

The BOR was shown in Supplementary Table S4. Ten (16.6%) patients in ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy group and 13 (21.6%) patients in ICI+TKI doublet therapy group achieved CR/PR. Twenty (33.3%) and 31 (51.6%) patients achieved SD (stable disease) in triple therapy group and doublet therapy group, respectively. The ORR in the triple therapy group was comparable with that in the doublet therapy group (21.6% versus16.6%, p=0.487).

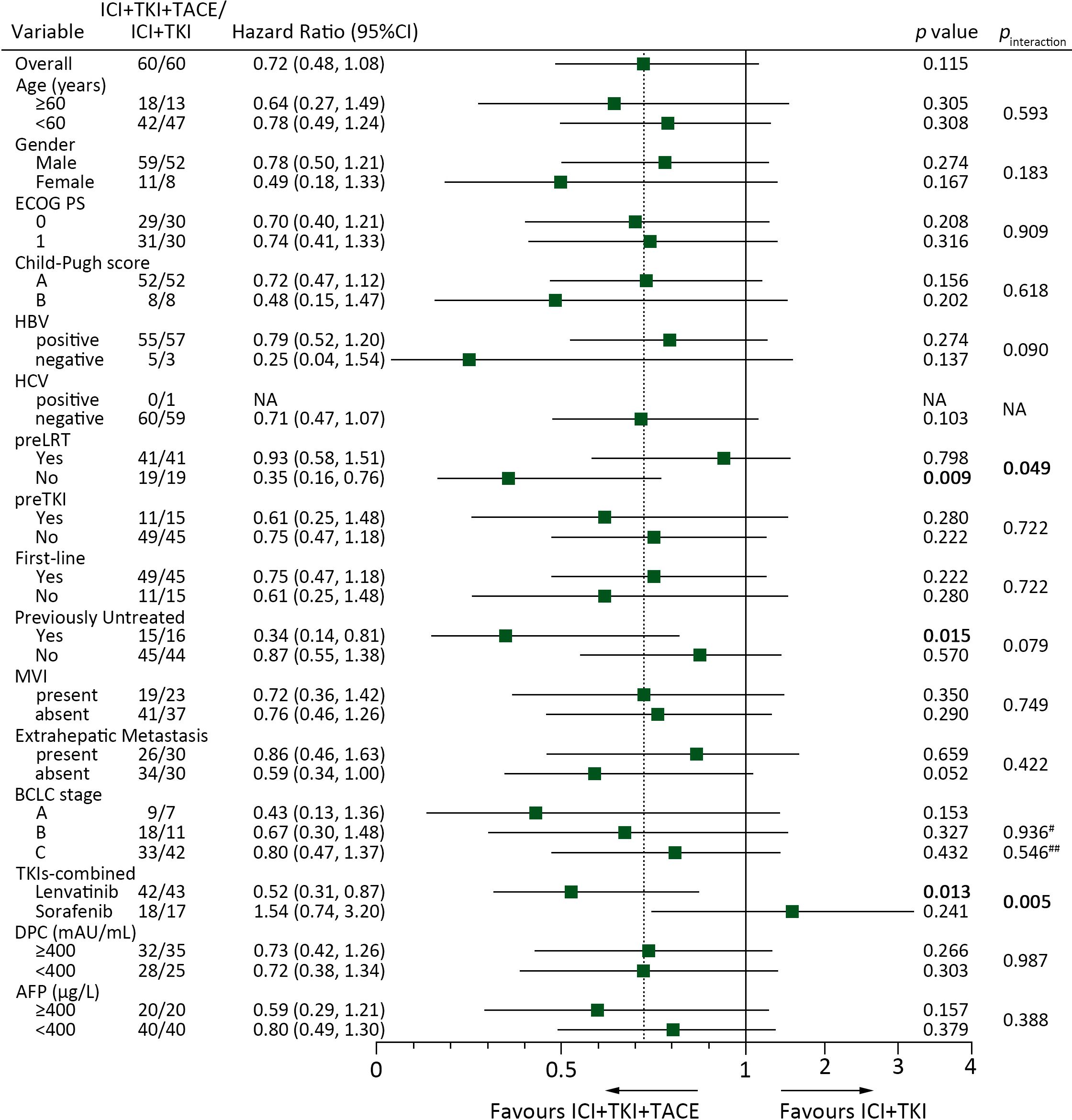

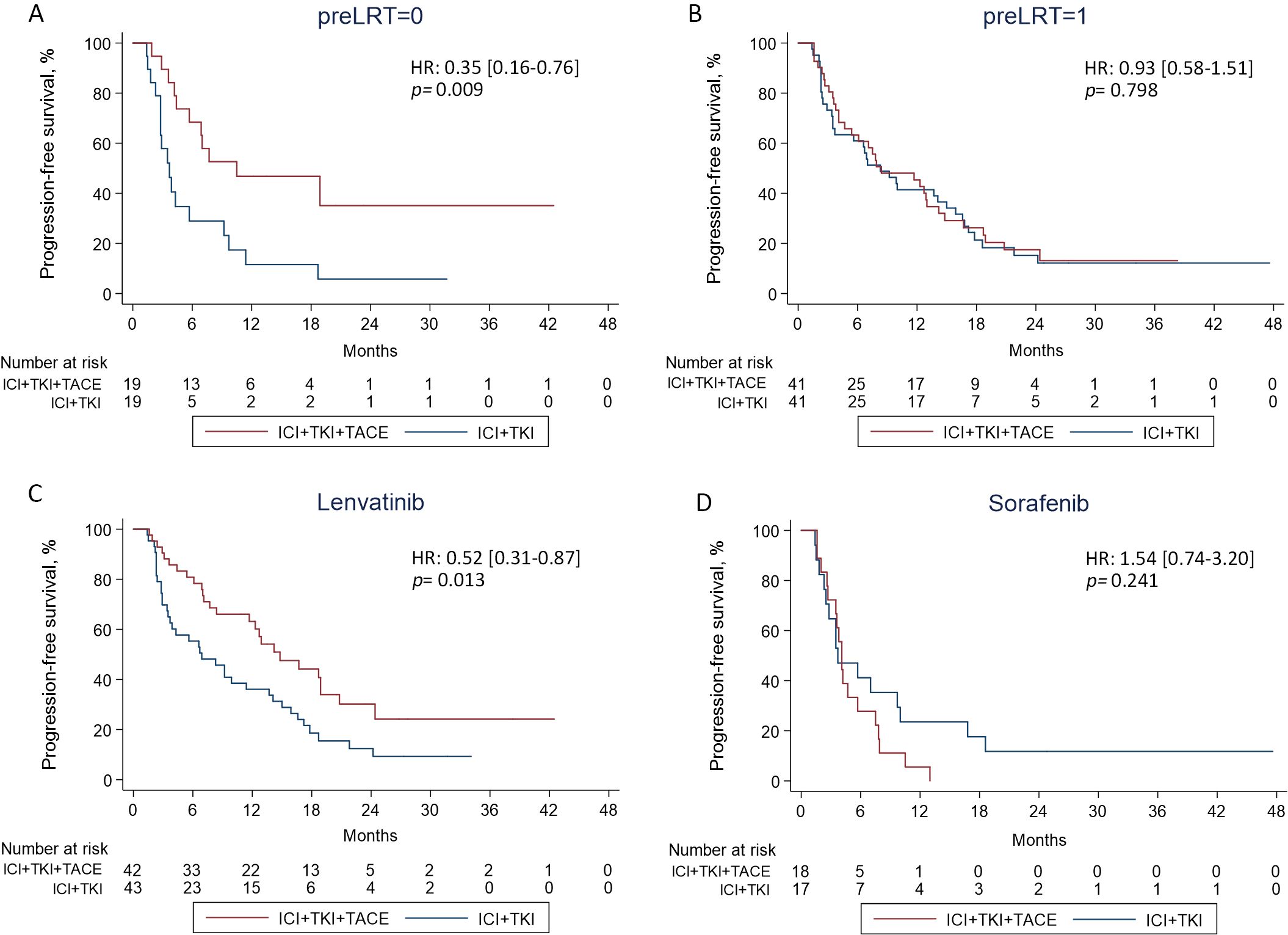

To determine potential factors affecting patients’ response to ICI+TKI+TACE or ICI+TKI therapy, subgroup analysis was further performed. Subgroup analysis for PFS illustrated that patients with no preLRT (10.5 versus 3.7 months, HR 0.35 [0.16-0.76]; p=0.009), with no previous treatment (10.5 versus 3.5 months, HR 0.34 [0.14-0.81]; p=0.015) or treated with lenvatinib (14.8 versus 6.9 months, HR 0.52 [0.31-0.87]; p=0.013) can significantly benefit from triple therapy compared with doublet therapy (Figure 3). In addition, a remarkable interaction between treatment and preLRT (p=0.049) or TKIs-combined (p=0.005) was also detected (Figure 3). Kaplan-Meier analysis also observed that patients without preLRT or treated with lenvatinib displayed notable improved PFS upon ICI+TKI+TACE therapy versus ICI+TKI therapy (Figures 4A, C), while in patients with preLRT or treated with sorafenib, the PFS was comparable between ICI+TKI+TACE and ICI+TKI group (Figures 4B, D). Subgroup analysis for OS illustrated that only patients without preLRT favored triple therapy compared with doublet therapy (26.0 versus 15.1 months, HR 0.36 [0.13-0.96]; p=0.043) (Supplementary Figure S2). However, the interaction analysis didn’t detect significant interactions between treatment and patient baseline characteristics for OS. In addition, the efficacy of different therapeutic regimens across BCLC stages was also compared. The results showed that in patients with BCLC stage A/B, patients treated with ICI+lenvatinib+TACE exhibited significantly prolonged PFS compared to those treated with ICI+lenvatinib (p= 0.023), while their OS was not significantly improved (Supplementary Figure S3). Furthermore, in patients with BCLC stage C, no difference of PFS and OS was observed between triple therapy and doublet therapy in lenvatinib or sorafenib subgroup (Supplementary Figure S3). Moreover, a total of 12 patients have subsequently undergone conversion surgery, with 7 (40.0%) patients in the triple therapy group and 5 (45.0%) patients in the doublet therapy group (Supplementary Table S5). The number of patients underwent conversion surgery was comparable between the two groups (p=0.762). In addition, the PFS was significantly superior in patients who underwent conversion surgery compared to those who did not (HR 0.39 [0.19-0.90]; p=0.027). However, OS was not improved (HR 0.32 [0.07-1.33]; p=0.118). There were no significant differences in PFS or OS between patients who underwent conversion surgery in ICI+TKI+TACE group and ICI+TKI group (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 3. Subgroup COX proportional hazards regression model analysis of PFS according to the baseline characteristics and different treatment groups. #, BCLC stage B versus A; ##, BCLC stage C versus A.

Figure 4. (A, B) The PFS was compared between the double and triple therapy groups in patients with or without preLRT. (C, D) The PFS was compared between the triple and doublet therapy groups in patients treated with lenvatinib or sorafenib.

Seventy-eight point eight (41/52) patients in the triple therapy group and 72.7% (32/44) patients in the doublet therapy group have received subsequent treatments post progression. Kaplan-Meier analysis of PPS revealed that patients with post progression treatment (PPTx) displayed significantly improved survival compared with those without in both ICI+TKI+TACE and ICI+TKI groups (Supplementary Figure S5).

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were reported in 40% (24/60) and 45% (27/60) of patients in ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy group and ICI+TKI doublet therapy group, respectively. The incidence of TRAEs between two groups was not significant (Supplementary Table S6). The most frequent TRAEs of any grade in the triple therapy group were rash (n=5, 8.3%) and mucosal inflammation (n=4, 6.6%). In the doublet therapy group, the most frequently reported TRAEs were rash (n=7, 11.6%), diarrhea (n=5, 8.3%), and hypothyroidism (n=5, 8.3%). Grade 3 events occurred in 5 patients (8.3%) in the triple therapy group and in 2 patients (3.3%) in the doublet therapy group. The incidence of TRAEs were summarized in Supplementary Table S7. TRAEs were evaluated according to Common Terminology Criteria for version 5.0 (National Cancer Institute) (21).

The success of IMbrave150 trial has launched a new era of ICI-based combination therapies in HCC. So far, the ORR was 29.8% with the combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in the IMbrave 150 study (5), and the highest ORR of systemic therapies for HCC was reported as 36% with pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib in the Keynote 524 study (6). Currently, the efficacy improvement with ICI-based systemic therapies has clearly hit a plateau for HCC. In addition to systemic therapies, LRTs including TACE were also utilized in combination with ICIs to further increase the efficacy (8, 9). Except the conventional role of inducing tumor necrosis, TACE was also found to promote T-cell activation via abscopal effects (22). The tumor necrosis caused by TACE increased the release of tumor-associated antigens (23, 24), which has been proven to recruit DCs and increase AFP-specific CD4+T-cell response (25), thus synergizing with ICIs to increase cytotoxic T lymphocytes and decrease tumor-infiltrating Treg cells (26). Lenvatinib was reported to effectively inhibit the angiogenic growth factors triggered by the extensive ischemic necrosis in preclinical (27) or clinical studies (17), which was also an important factor associated with T-cell activation. Recently, several studies have investigated the efficacy of TKI plus ICI in combination with TACE and demonstrated an ORR of 46.7%-69.3% (28–35). The LEAP-012 trial demonstrated a significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS for patients with unresectable HCC compared to TACE plus placebo. Similarly, the combination of durvalumab, bevacizumab, and TACE in the EMERALD-1 study also showed potential to establish a new standard of care (36, 37). Nonetheless, the studies comparing the efficacy of ICI+TKI+TACE with ICI+TKI were still limited. Herein, we leveraged a retrospective cohort of HCC patients treated with triple therapy or doublet therapy and firstly revealed that the outcomes were not significantly improved after the addition of TACE to ICI plus TKI combination therapy.

The efficacy of TKI or ICI monotherapy was limited in clinical studies, with an ORR of 6.5% with sorafenib (3), 15-17% with PD-1 inhibitors (4), and 18.8% with lenvatinib (3). The anti-angiogenesis function of TKIs including lenvatinib was involved in several steps of T-cell activation, including the restoration of antigen presentation, the priming and activation of T-cell responses, and the modulation of the tumor immune microenvironment (38, 39). Furthermore, lenvatinib was also found to regulate pathways modulating antitumor immunity, including the reduction of tumor PD-L1 expression levels and Treg differentiation by blocking Fibroblast growth factor receptor-4 (FGFR4) (40) and reducing the Treg proportion via TGF-b pathway inhibition (41). Indeed, the combination therapy of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab initially displayed encouraging efficacy for HCC (6). However, subsequent phase III study LEAP-002 only achieved an ORR of 26.1% and failed to meet its primary endpoint on OS and PFS (7). Similar negative results were also observed in the Cosmic-312 study (42). However, subgroup analysis of LEAP-002 revealed that patients with higher AFP levels, extrahepatic spread or MVI may significantly benefit from lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab, indicating the efficacy of this combination in selected patients (7). Likewise, our data also showed that the outcomes of patients treated with ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy were not significantly improved versus ICI+TKI doublet therapy. But subgroup and interaction analysis of PFS identified that patients with no preLRT or treated with lenvatinib as combination are more likely to benefit from triple therapy, further highlighting the importance of patient selection in the combination therapy for HCC, which indeed merits further investigation.

LRTs are common regimens to treat patients with uHCC (22). The combinations of LRTs and ICI-based systemic therapies are promising therapeutic strategies and are currently under investigation in HCC (8). Mechanistically, other than tumor elimination, LRT can promote antigenic or immunogenic cell death, thereby augmenting tumor immunogenicity and synergizing with ICIs (8, 43). However, the optimal patient population which is suited for combined locoregional treatments is still not clear. With the recent overwhelming trend of ICI-based combinational therapy in HCC, the triple therapy of ICI+TKI+TACE has increasingly been utilized in clinical practice. However, our real-world data revealed no significant improvement in PFS and OS with triple therapy compared to doublet therapy, suggesting that the addition of TACE to the ICI+TKI combination therapy did not necessarily improve outcomes in the overall population, thereby challenging the notion that “more is better” in HCC combination therapy. Furthermore, the benefit of triple therapy was only observed in selected patients (without preLRT or treated with lenvatinib as combination), emphasizing the importance of tumor heterogeneity and personalized therapy in HCC.

The REFLECT trial and subsequent re-analysis of data showed non-inferiority of lenvatinib versus sorafenib in terms of OS, as well as statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS, time to progression, and ORR (3). Lenvatinib is a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor analogous to sorafenib, with unique high selectivity for FGF receptor 1-4 (FGFR1-4) (3). Of the receptors, FGFR4 is considered a potent target of lenvatinib in the treatment of HCC (44), providing a mechanistic rationale for that lenvatinib resulted in a statistically significant improvement in ORR compared with sorafenib in REFLECT trial. Likewise, Yang et al. have reported TACE plus lenvatinib was significantly superior to TACE plus sorafenib with respect to OS, PFS, and ORR (45). In addition, lenvatinib was also found to target FGFR4 to enhance antitumor response of ICI in HCC (40). Consistently, our data showed that patients treated with ICI+lenvatinib displayed superior PFS versus ICI+sorafenib (Supplementary Table S2). Importantly, we further revealed that in the patients treated with ICI+lenvatinib, the addition of TACE can remarkably improve PFS in comparison with those treated with ICI+sorafenib, suggesting the synergistic effect between TACE and ICI+lenvatinib.

In the ICI+TKI group, the point of treatment initiation was defined as the initiation of systemic therapy, while in the ICI+TKI+TACE group, it was defined as the initiation of TACE or systemic therapy, whichever comes first. Notably, treatment sequences in landmark trials vary. In LEAP-012 trial, TACE was initiated 2-4 weeks after systemic therapy, while in EMERALD-1 study, durvalumab with or without bevacizumab was administered 7 days post-TACE (36, 37). Moreover, current guidelines also lack consensus on optimal sequencing of TACE and systemic therapy. Due to the nature of real-world studies, the point of treatment initiation was inconsistent between the two groups in our study. Nonetheless, the interval between TACE and systemic therapy was within an acceptable range, and patients in triple therapy group could be considered to have received concurrent TACE and ICI+TKI therapy, and the impact of this inconsistency on the results was largely limited.

In clinical trials, post-progression therapy or treatment crossover after progression increases the fragility of overall survival as an endpoint (46). The COSMIC-312 study (42) only observed an improved PFS in HCC patients treated with cabozantinib plus atezolizumab versus sorafenib but not OS. Similarly, our data also didn’t detect significant interactions between preLRT or TKIs-combined with treatment via interaction analysis of OS, which was probably due to that almost 3/4 progressed patients in both triple therapy and doublet therapy groups had received subsequent post-progression therapies.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a single center retrospective study and almost all patients had an etiology of HBV infection, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Second, the portion of patients with ECOG PS 1 or Child-pugh score B was significantly higher in ICI+TKI doublet therapy group than that in triple therapy group before PS matching (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that patients with relatively good performance or preserved liver functions tended to receive ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy. This bias is probably because, currently, as a potent means of LRT, TACE is preferred to be combined with ICI plus TKI therapy for uHCC when patient conditions permit in the real world. Although PS matching balanced the differences of baseline characteristics between the two groups, our findings still should be confirmed in prospective randomized studies. Third, unlike the LEAP-012 trial (19), in which TACE was limited to 2 treatments per tumor, repeated TACE was allowed in this study, which was also in accordance with the situation in the real world.

In conclusion, compared with ICI+TKI doublet therapy, ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy showed minimal difference in the efficacy for uHCC. However, patients with no preLRT or treated with lenvatinib can significantly benefit from ICI+TKI+TACE triple therapy in terms of PFS, providing a rationale for conducting prospective studies to assess the efficacy of adding TACE to ICI plus TKI combination therapy in selected patients with uHCC.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by The Institutional Ethics Committee of Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because As patient identities were anonymized, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committees.

HP: Writing – original draft. MR: Writing – original draft. RJ: Writing – original draft. JZ: Writing – original draft. YL: Writing – original draft. DW: Writing – original draft. LZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. WS: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. RW: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 81972777, 82373300 and 81972810, Clinical Research Plan of Shanghai Hospital Development Center (SHDC2020CR4040), Program of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (21Y11912600).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1385304/full#supplementary-material

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

3. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2018) 391:1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1

4. Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Mathurin P, Edeline J, et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00604-5

5. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. (2022) 76:862–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030

6. Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, et al. Phase ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:2960–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00808

7. Llovet JM, Kudo M, Merle P, Meyer T, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-002): a randomised, doubleblind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2023) 24(12):1399–410.

8. Greten TF, Mauda-Havakuk M, Heinrich B, Korangy F, Wood BJ. Combined locoregional-immunotherapy for liver cancer. J Hepatol. (2019) 70:999–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.027

9. Singh P, Toom S, Avula A, Kumar V, Rahma OE. The immune modulation effect of locoregional therapies and its potential synergy with immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2020) 7:11–7. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S187121

10. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2002) 359:1734–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X

11. Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. (2018) 391:1301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2

12. Omata M, Cheng AL, Kokudo N, Kudo M, Lee JM, Jia J, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol Int. (2017) 11:317–70. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9

13. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, Torimura T, Tanabe N, Aikata H, et al. Randomised, multicentre prospective trial of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial. Gut. (2020) 69:1492–501. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318934

14. Peng Z, Fan W, Zhu B, Wang G, Sun J, Xiao C, et al. Lenvatinib combined with transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III, randomized clinical trial (LAUNCH). J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:117–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00392

15. Sergio A, Cristofori C, Cardin R, Pivetta G, Ragazzi R, Baldan A, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): the role of angiogenesis and invasiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. (2008) 103:914–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01712.x

16. Ogasawara S, Mihara Y, Kondo R, Kusano H, Akiba J, Yano H. Antiproliferative effect of lenvatinib on human liver cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Anticancer Res. (2019) 39:5973–82. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13802

17. Fu Z, Li X, Zhong J, Chen X, Cao K, Ding N, et al. Lenvatinib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): a retrospective controlled study. Hepatol Int. (2021) 15:663–75. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10184-9

18. Marinelli B, Kim E, D’Alessio A, Cedillo M, Sinha I, Debnath N, et al. Integrated use of PD-1 inhibition and transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation of safety and efficacy in a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. J Immunother Cancer. (2022) 10. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004205

19. Llovet JM, Vogel A, Madoff DC, Finn RS, Ogasawara S, Ren Z, et al. Randomized phase 3 LEAP-012 study: transarterial chemoembolization with or without lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma not amenable to curative treatment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. (2022) 45:405–12. doi: 10.1007/s00270-021-03031-9

20. Kudo M, Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Sakurai T, Kitano M, Nishida N. Subclassification of BCLC B stage hepatocellular carcinoma and treatment strategies: proposal of modified bolondi’s subclassification (Kinki criteria). Dig Dis. (2015) 33:751–8. doi: 10.1159/000439290

21. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v5.0. Available online at: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm (Accessed November 27, 2017).

22. Lencioni R. Loco-regional treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. (2010) 52:762–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.23725

23. Khan KA, Kerbel RS. Improving immunotherapy outcomes with anti-angiogenic treatments and vice versa. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:310–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.9

24. den Brok MH, Sutmuller RP, Nierkens S, Bennink EJ, Frielink C, Toonen LW, et al. Efficient loading of dendritic cells following cryo and radiofrequency ablation in combination with immune modulation induces anti-tumour immunity. Br J Cancer. (2006) 95:896–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603341

25. Ayaru L, Pereira SP, Alisa A, Pathan AA, Williams R, Davidson B, et al. Unmasking of alpha-fetoprotein-specific CD4(+) T cell responses in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing embolization. J Immunol. (2007) 178:1914–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1914

26. Rahma OE, Hodi FS. The intersection between tumor angiogenesis and immune suppression. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 25:5449–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1543

27. Jin H, Shi Y, Lv Y, Yuan S, Ramirez CFA, Lieftink C, et al. EGFR activation limits the response of liver cancer to lenvatinib. Nature. (2021) 595:730–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03741-7

28. Cai M, Huang W, Huang J, Shi W, Guo Y, Liang L, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:848387. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.848387

29. Cao F, Yang Y, Si T, Luo J, Zeng H, Zhang Z, et al. The efficacy of TACE combined with lenvatinib plus sintilimab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:783480. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.783480

30. Guo P, Pi X, Gao F, Li Q, Li D, Feng W, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization plus lenvatinib with or without programmed death-1 inhibitors for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score matching study. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:945915. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.945915

31. Li X, Fu Z, Chen X, Cao K, Zhong J, Liu L, et al. Efficacy and safety of lenvatinib combined with PD-1 inhibitors plus TACE for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients in China real-world. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:950266. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.950266

32. Qu WF, Ding ZB, Qu XD, Tang Z, Zhu GQ, Fu XT, et al. Conversion therapy for initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using a combination of toripalimab, lenvatinib plus TACE: real-world study. BJS Open. (2022) 6. doi: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrac114

33. Teng Y, Ding X, Li W, Sun W, Chen J. A retrospective study on therapeutic efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors plus lenvatinib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. (2022) 21:15330338221075174. doi: 10.1177/15330338221075174

34. Xiang YJ, Wang K, Yu HM, Li XW, Cheng YQ, Wang WJ, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization plus a PD-1 inhibitor with or without lenvatinib for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. (2022) 52:721–9. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13773

35. Qu S, Zhang X, Wu Y, Meng Y, Pan H, Fang Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of TACE combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors compared with TACE alone for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A prospective cohort study. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:874473. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.874473

36. Kudo M, Ren Z, Guo Y, Han G, Lin H, Zheng J, et al. Transarterial chemoembolisation combined with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus dual placebo for unresectable, non-metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-012): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. (2025) 405:203–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02575-3

37. Sangro B, Kudo M, Erinjeri JP, Qin S, Ren Z, Chan SL, et al. Durvalumab with or without bevacizumab with transarterial chemoembolisation in hepatocellular carcinoma (EMERALD-1): a multiregional, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. (2025) 405:216–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02551-0

38. Huang Y, Goel S, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Vascular normalization as an emerging strategy to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:2943–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4354

39. Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:325–40. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29

40. Yi C, Chen L, Lin Z, Liu L, Shao W, Zhang R, et al. Lenvatinib targets FGF receptor 4 to enhance antitumor immune response of anti-programmed cell death-1 in HCC. Hepatology. (2021) 74:2544–60. doi: 10.1002/hep.31921

41. Torrens L, Montironi C, Puigvehi M, Mesropian A, Leslie J, Haber PK, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of lenvatinib plus anti-programmed cell death protein 1 in mice and rationale for patient enrichment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. (2021) 74:2652–69. doi: 10.1002/hep.32023

42. Kelley RK, Rimassa L, Cheng AL, Kaseb A, Qin S, Zhu AX, et al. Cabozantinib plus atezolizumab versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (COSMIC-312): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00326-6

43. Greten TF, Duffy AG, Korangy F. Hepatocellular carcinoma from an immunologic perspective. Clin Cancer Res. (2013) 19:6678–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1721

44. Kanzaki H, Chiba T, Ao J, Koroki K, Kanayama K, Maruta S, et al. The impact of FGF19/FGFR4 signaling inhibition in antitumor activity of multi-kinase inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:5303. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84117-9

45. Yang B, Jie L, Yang T, Chen M, Gao Y, Zhang T, et al. TACE plus lenvatinib versus TACE plus sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: A prospective cohort study. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:821599. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.821599

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, immune checkpoint inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, combination therapy

Citation: Pan H, Ruan M, Jin R, Zhang J, Li Y, Wu D, Zhang L, Sun W and Wang R (2025) Immune checkpoint inhibitor plus tyrosine kinase inhibitor with or without transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 15:1385304. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1385304

Received: 13 March 2024; Accepted: 11 February 2025;

Published: 10 March 2025.

Edited by:

Simona Kranjc Brezar, Department of Experimental Oncology, SloveniaReviewed by:

Renguo Guan, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Pan, Ruan, Jin, Zhang, Li, Wu, Zhang, Sun and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruoyu Wang, d2FuZ3J1b3l1MTIxM0AxMjYuY29t; Wen Sun, c3Vud2VuX3N3QGFsaXl1bi5jb20=; Lijie Zhang, amVsbHl6aGFuZy5va0AxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.