- 1Department of Global Pediatric Medicine, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, United States

- 2University of Child Health Sciences, Children’s Hospital Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

- 3Department of Oncology, Indus Hospital and Health Network, Karachi, Pakistan

- 4Department of Oncology, Dana Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Background: Communication is an essential aspect of high-quality patient- and family-centered care. A model for pediatric cancer communication developed in the United States defined eight communication functions. The purpose of this study was to explore the relevance of these functions in Pakistan as part of an effort to understand the role of culture in communication.

Materials and methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 clinicians and 18 caregivers of children with cancer at two major cancer centers. Interviews were conducted in Urdu or English and transcribed and translated as necessary. Two independent coders used a priori codes related to the communication model as well as novel codes derived inductively. Thematic analysis focused on operationalization of the functional communication model.

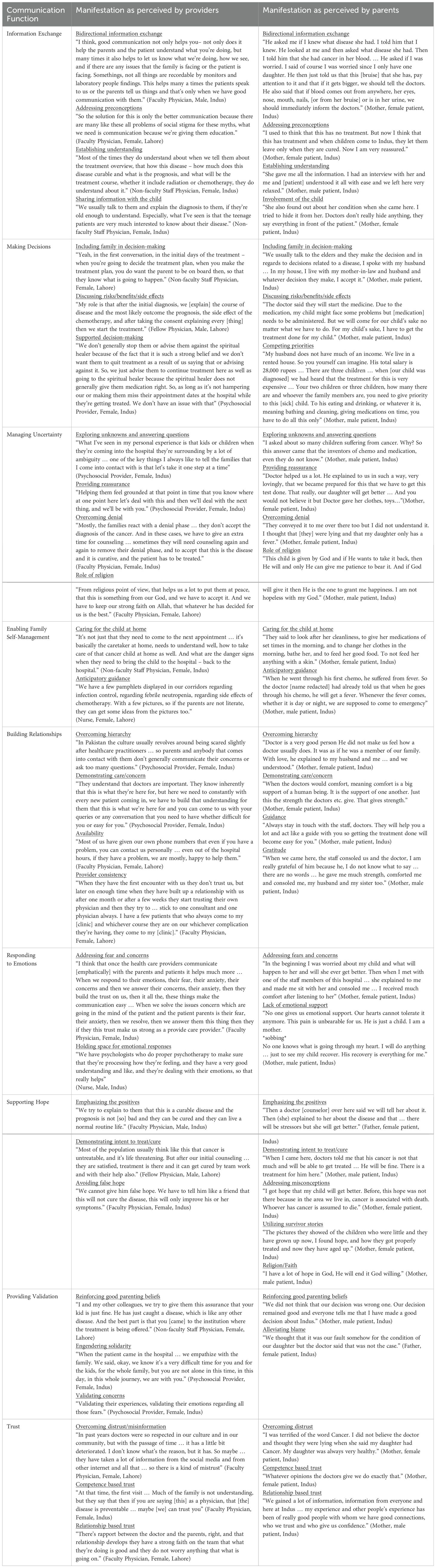

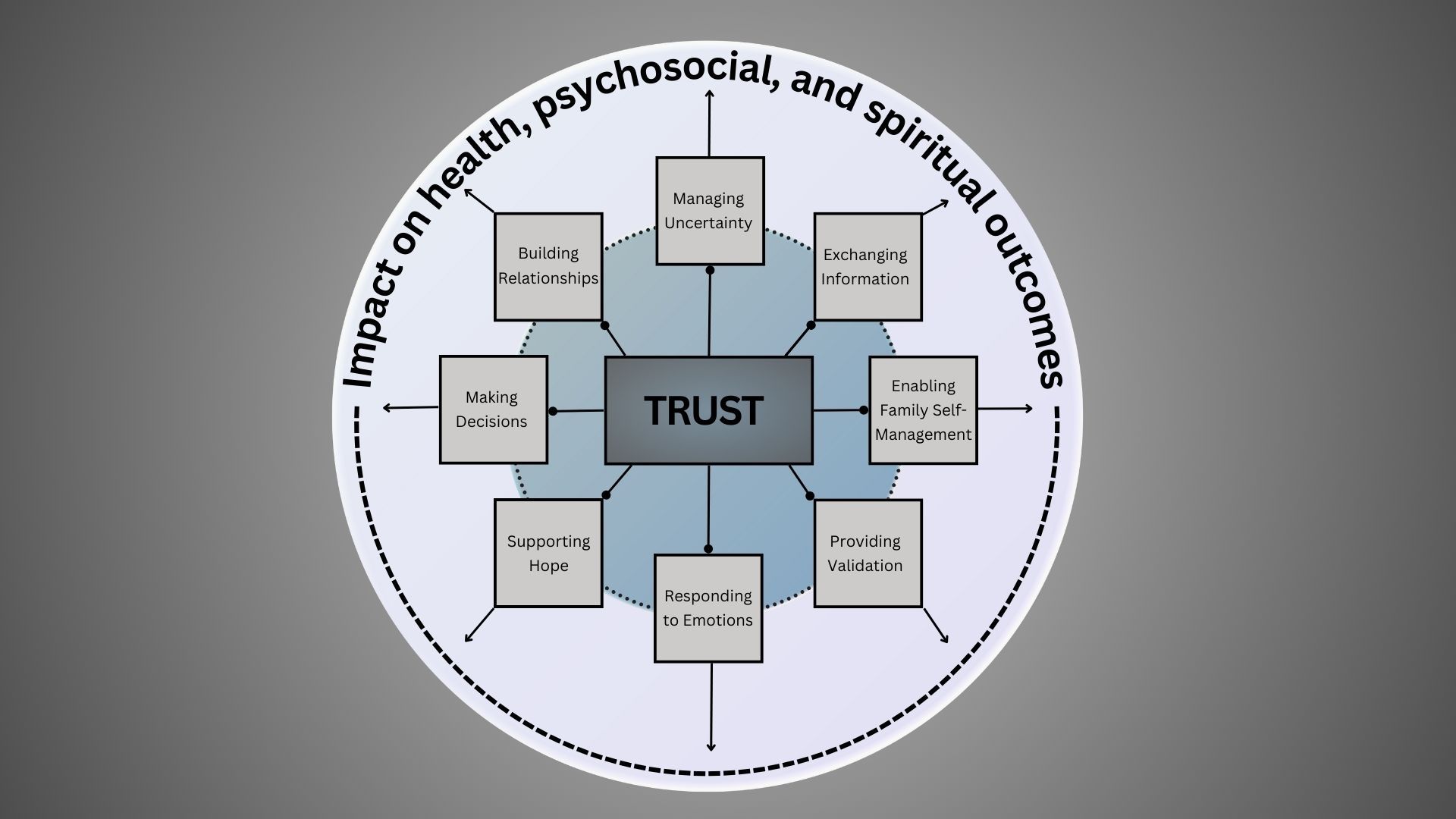

Results: Clinicians and caregivers in Pakistan discussed the importance of all eight communication functions previously identified including: information exchange, decision-making, managing uncertainty, enabling family self-management, responding to emotions, supporting hope, providing validation, and building relationships. The operationalization of these functions was influenced by Pakistani cultural context. For example, information-exchange included the importance of addressing preconceptions and community myths, while managing uncertainty included strong references to religion and faith-based coping. Essential to all eight functions was trust between the family and the medical team.

Discussion: These findings support the use of this functional communication model in diverse pediatric oncology settings and emphasize the importance of trust. Culturally sensitive operationalization of these functions could inform the adaptation of tools to measure communication and interventions aimed at supporting the needs of parents of children with cancer.

Introduction

Communication is a central component of patient-centered pediatric cancer care. Families that experience “high-quality” communication have a heightened sense of purpose and peace of mind (1), are more hopeful (2), and describe increased trust of the medical team (3). Improved communication enables patients and caregivers to feel more comfortable caring for their disease at home (4) and aids in decision-making (5). On the other hand, patients and families who experience poor communication are at risk for decisional regret (6), emotional distress (7), and poor understanding (8).

In 2007, researchers at the National Cancer Institute in the United States proposed a model for communication that focused on interactions between adult cancer patients and their medical teams, identifying six interdependent communication functions: “building relationships”, “enabling family self-management”, “making decisions”, “managing uncertainty”, “responding to emotions”, and “exchanging information” (9). This model applies to communication tasks and outcomes from the time of diagnosis, throughout the cancer continuum and has been used for over a decade to define high-quality cancer communication including prediction of patients at risk for poor communication (10) and interventions aimed at improving cancer communication (11). In 2020, the model was adapted for pediatric cancer care and two additional functions, “supporting hope” and “providing validation”, were added (12). “Providing validation” includes ways in which clinicians empower parents, validate concerns, and assure them they are doing a good job. “Supporting hope” was operationalized as emphasizing positives, encouraging hope beyond cure, demonstrating intention to treat, and avoiding false hope, which might include, for example, avoiding the truth about a poor prognosis (12). Although the pediatric adaptation was published more recently, it has already been used in the United States to develop tools to assess pediatric cancer communication at the bedside (13).

While not always explicitly studied, all of the initial six functions have been noted in communication literature from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (14), where 90% of children with cancer live (15). Our prior work explicitly investigated these functions and found them to be prioritized by patients and families in Guatemala (16, 17). We have hypothesized that the equifinality of this functional model will make it adaptable for use in many low- and middle-income countries (18). Culture, including social norms, customs, religion, and traditions shape health-related beliefs and behaviors and are known to impact communication and decision-making during cancer care (19, 20). In order to further investigate how this model might apply or differ in distinct cultural settings, this study was conducted in two pediatric cancer centers in Pakistan. Pakistan is a lower-middle income country with a diverse population of approximately 200 million people who speak >75 different languages. Every year, an estimated 8,000-12,000 children develop cancer and <50% of these children survive (15, 21). Pakistan is a country with rich internal diversity as well as a population and healthcare system that is distinct from those in which this model has been previously applied. We conducted qualitative interviews with clinicians and caregivers of children with cancer treated at two pediatric cancer centers in Pakistan, exploring communication experiences and needs in order to examine the operationalization of this model in this unique setting.

Materials and methods

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines were used to ensure rigor in conducting and reporting this study (22).

Settings and participants

We interviewed clinicians and caregivers at two of the nine centers caring for children with cancer in Pakistan: Indus Hospital and Health Network in Karachi and Children’s Hospital of Lahore. These hospitals are large referral centers. Each treat >1200 newly diagnosed pediatric patients a year, and both provide care to children free of charge. Clinician participants were eligible if they (1) spoke English, (2) were involved in the care of children with cancer, and (3) were employed at either center; purposive sampling was used to ensure a range of professionals. Caregiver interviews were conducted only at Indus Hospital and Health Network, as this team had the local human resources and training necessary to conduct qualitative interviews. Caregivers were eligible if they (1) had a child with cancer under the age of 19 years old who (2) had been diagnosed within the last 8 weeks.

We focused on diagnosis because it is a critical time for communication. It is a time filled with anxiety, fear, and uncertainty for families (23, 24) and is the medical team’s first opportunity to develop rapport and set the stage for an ongoing relationship as early treatment decisions are made. In addition, in Pakistan, like other LMICs, there is a high rate of treatment abandonment defined as the failure to start or complete curative therapy (25–27). High-quality communication from the time of diagnosis could minimize abandonment, a leading cause of mortality in these settings.

Data collection

We conducted semi-structured interviews using a guide based on prior work (5, 28) and previously established functional communication framework (12, 18) (Supplementary Figure 1). Questions focused on experiences with communication at diagnosis including strengths, weaknesses, communication priorities, and unmet needs. Members of the research team (C.S. and G.F.) who did not work at either hospital conducted interviews with clinicians in English over Zoom. Interviews with families were conducted in person in Urdu by members of the research team (As N, At N, At Q, SM) in Pakistan. All interviewers had qualitative research training. Interviews lasted approximately 30-60 minutes, were audio-recorded, and professionally transcribed and translated into English as necessary.

Data analysis

We analyzed transcripts using thematic analysis (29) beginning with an a priori functional model for communication previously described and highlighted for global pediatric oncology (12, 18, 30). Additionally, three authors (D.G., C.S., G.F.) iteratively read transcripts to identify novel codes based on recurrent themes. The codebook was developed through iterative review and application to 17 transcripts. Two researchers (C.S. and G.F.) independently applied codes using the final codebook (Supplementary Table 1) and MAXQDA software (VERBI, Berlin, Germany). Coders met to resolve discrepancies by consensus with a third-party adjudicator (D.G.) present as necessary.

Results

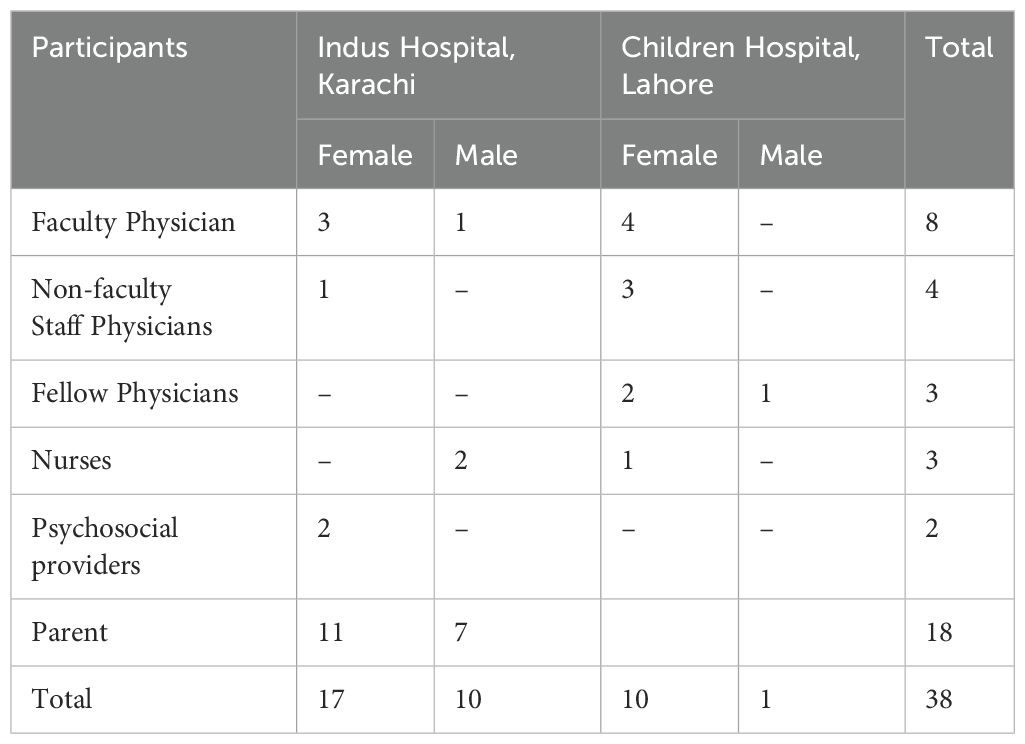

We interviewed 20 multidisciplinary oncology clinicians, nine from Indus Hospital in Karachi, and 11 from Children’s Hospital Lahore. Clinicians included faculty, fellow, and non-faculty physicians, nurses, and psychosocial providers. We also interviewed 18 caregivers of children diagnosed with cancer at Indus including 11 females and 7 males (Table 1).

Participants discussed all eight of the previously identified communication functions and highlighted the importance of “trust” as an element underpinning each function.

Information exchange

All participants discussed “information exchange.” Clinicians and caregivers emphasized that information exchange should be bidirectional and discussed the importance of addressing cancer preconceptions (Table 2). Successful communication, according to participants, depended on families’ ultimate understanding of their child’s diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan. One clinician described this saying: “The initial or the general impression that most parents have [is that cancer is] just like a death [sentence]. And when we try to explain to them that this is a curable disease and the prognosis is not as bad and they can be cured and they can live a normal routine life … then they do understand and it helps” (Faculty Physician, Male, Indus). Many caregivers and clinicians also discussed the importance of sharing information with the pediatric patient, particularly adolescents.

Decision-making

Every interview included “decision-making.” Participants discussed the importance of involving the family in decision-making, including extended family members. Clinicians and caregivers also identified a discussion of risks, benefits, and side effects as important to the decision-making process (Table 2). Caregivers explained their competing priorities and how factors beyond the cancer center including geography, family income, and other children weighed on them as they made decisions. Caregivers and clinicians described how acknowledgment of these competing factors during diagnostic communication helped families accept care. One caregiver said, “The [psychologist] helped us a lot … she asked what happened, how it happened and I told her about my house’s situation and how our life is going like this and said that really, you have seen many worries and when a child gets sick, the entire house gets affected … [she] said that don’t worry, her test will be done in the same way as other kids. But she has a little problem with her brain, hence we would need brain doctors … As soon as the doctor called us, we went” (Mother, female patient, Indus). Clinicians also emphasized the importance of supported decision-making, including recognizing traditional beliefs and allowing families to continue traditional therapies as long as they did not interfere with allopathic care.

Managing uncertainty

“Managing uncertainty” was identified in every interview. Components of this function included exploring unknowns and answering questions, providing reassurance, overcoming denial, and the role of religion (Table 2). One clinician described how she handles persistent uncertainty by acknowledging the unknown and providing small amounts of information at a time: “So we will tell them that your child now this is happening now … we will go there, so they absorb easily. If we tell all the things [at once] I think – for them [it causes] too much worry … In every disease we can’t predict all the things in the first go. And we can’t predict, we don’t know [how the child will react once] we give the chemotherapy … We can’t give them 100% that your child will survive” (Fellow Physician, Female, Lahore). Caregivers and clinicians both discussed the solace they found in religion and the role of God, or Allah, and how they used this shared faith to help manage uncertainty. One parent said: “I believe in God. We have come this far and the surgery will also happen God willingly and God will take care of it” (Mother, female patient, Indus).

Enabling family self-management

Every interview referenced “enabling family self-management” which manifested as caring for the child at home and anticipatory guidance regarding what to expect and when to bring the child back to the cancer center (Table 2). Caregivers and clinicians discussed the role of effective communication in not only making sure the patient made it to their appointments, but also that the child was well cared for at home, including following specific guidance regarding hygiene and nutrition. Taking care of a child with cancer was a constant responsibility. As one parent described: “For my child, I am always ready. Day or night for [my child] for 24 hours I am ready to give him attention and put my other tasks to one side. All my time is for [my child]. [My child] needs to eat this now, [my child] needs to get up, [my child] needs to sleep, [my child] needs to take a bath, [my child] needs to study so it is all of my effort to give all of my attention to [my child] and whatever advice the doctors gives or you give, in accordance with that I keep my child prepared at home like that” (Mother, male patient, Indus).

Building relationships

“Building relationships” was identified in every interview. Caregivers and clinicians referenced a cultural hierarchy separating physicians from patients that had to be overcome at the start of a therapeutic relationship and explained how clinicians established rapport by demonstrating care and concern (Table 2). As one parent said: “Doctor X appreciates a lot and loves my child very much … she lets me know about everything … I am very at ease with her and the staff” (Mother, male patient, Indus). Clinicians further described how they built relationships by making themselves available to families and providing a consistent presence. Over time, clinicians explained, families began to trust and seek out specific clinicians. As caregivers described this relationship, they emphasized the guidance available clinicians provided them and the gratitude they felt toward the medical team: “It is their kindness that they will get the treatment done … I am trying to thank them. Aside from this, I have nothing to offer them. I can only thank them and pray for them” (Mother, female patient, Indus).

Responding to emotions

All clinician interviews and 17/18 caregiver interviews included “responding to emotions.” The dominant emotions discussed were anxiety, fear, worry, and concern. This function manifested as clinicians addressing and responding to those fears and concerns. As one parent said: “[When we come here (initially), we are all very worried]. Believe me that our worry was so much when we were coming here but just a little bit of [clinician] attention, the doctor’s attention, or a social department’s attention is a source of much happiness for us. And I become relaxed” (Mother, male patient, Indus). Clinicians specifically discussed how a multidisciplinary team including psychologists allowed them to hold space for emotional responses to treatment. On the other hand, a few parents described unmet emotional needs and a lack of emotional support (Table 2).

Supporting hope

“Supporting hope” appeared in most (16/20) clinician interviews and all but one caregiver interview (17/18). In both clinician and caregiver interviews, supporting hope manifested as emphasizing the positives and demonstrating intent to treat or cure (Table 2). Clinicians discussed the importance of avoiding false hope, especially in the setting of poor prognosis. Caregivers described how clinicians addressed misconceptions and utilized survivor stories to further support hope. Caregivers also frequently discussed how their faith gave them hope, and how clinician’s references to God supported this hope. At times, caregivers connected God (Allah) to the medical team: “I am … very hopeful in God and the doctors too” (Mother, male patient, Indus).

Providing validation

“Providing validation” was identified in half (10/20) of the clinician interviews and some (7/18) caregiver interviews. This manifested as reinforcing good parenting beliefs and minimizing regret, particularly around decision-making. As one parent described “[My child’s clinician] said okay, you have made such a good decision” (Mother, male patient, Indus). Clinicians further described how they empathized, validated caregiver concerns, and partnered with families to engender solidarity. For caregivers, providing validation also manifested as alleviating blame or guilt (Table 2).

Trust

In previous models, trust has been explicitly discussed as a component of “building relationships” and described as an outcome of high-quality communication. In this study, participants described “trust” existing before and throughout diagnostic communication. “Trust” was identified in 75% (15/20) of clinician interviews and about half of the caregiver interviews (8/18). Participants described overcoming initial mistrust stemming from disinformation and depicted both competence-based trust as well as relationship-based trust (Table 2). Competence-based trust included a deference to clinicians based on their position or title and expected knowledge. One parent described this as close to God “after God, doctors are responsible for making this treatment successful and curing this disease” (Mother, male patient, Indus). Relationship-based trust, on the other hand, stemmed from rapport that was built over time: “Every time [there is] good communication … patient and parents increase [their] acceptance of the treatment … so the treatment compliances increases and their … understanding is increasing their trust … and their false misconceptions decreasing, their distress is decreasing and … their trust in their physician increases” (Faculty Physician, Female, Indus).

Discussion

This multicenter study demonstrates that a functional model for pediatric cancer communication developed and previously applied in high-income western settings (12) is relevant in Pakistan, a lower-middle income country located in the Middle East. Our findings confirm prior work exploring the possibility of applying this model to diverse settings with variable resources (18).

The specific manifestations of these functions, and the extent to which they were discussed by Pakistani participants highlight the importance of culture and the equifinality of the model. All eight functions were discussed by a majority of both clinician and parent participants, with 5/8 functions (information exchange, decision-making, managing uncertainty, enabling self-management and building relationships) identified in every interview. Supporting hope was discussed by a higher percentage of parents than caregivers, while providing validation and trust were discussed in more clinician interviews. Hope has been a major area of focus in communication research in pediatric oncology both from high-income (31) and low-income contexts (17). Our data confirms the importance of honesty highlighted in prior literature and emphasizes a connection to faith or religion as helpful to supporting hope within the Pakistani context. The role of religion was also discussed by clinician and caregiver participants in relation to managing uncertainty. Pakistan is a predominantly Muslim country and this shared faith emerged as important in diagnostic conversations in a way that has not been described in similar studies conducted in the United States.

Information exchange and decision-making have also been the focus of communication work in high-income countries and were prioritized in work from Guatemala (16), another middle-income country that is geographically and culturally distinct from Pakistan. While this may indicate the relative importance of these two functions in all settings, it is also possible that there are specific conditions in LMICs that contribute to their emphasis by participants. For example, limited childhood cancer awareness, misconceptions, and low health literacy may contribute to the need for explicit and thorough information exchange in LMICs. Similarly, decision-making in these settings may be complicated by extended family involvement and traditional beliefs. It is also possible that different communication functions emerge as more or less relevant at different times throughout the cancer care continuum. This study, as well as those conducted in Guatemala (5, 16), focused on diagnostic communication, a time during which there is a lot of essential information that must be exchanged, and many decisions must be made.

In addition to the eight identified communication functions, participants in this study discussed the importance of trust. Previous models implicitly mention trust as a component of many functions and specifically incorporated trust as a component of “building relationships,” while also highlighting it as an outcome of high-quality communication (9, 12). Clinicians and caregivers in this study discussed the importance of trust before and during diagnostic communication. Many acknowledged that families had to overcome distrust in the medical system before accepting care and others described competence-based trust (32, 33) that was related to a family’s prior experiences or inherent faith in the medical team rather than the actions or words of the clinician. Over time, relationship-based trust (32) was established. Actions taken by the medical team and time spent caring for a child with cancer led caregivers to overcome their initial distrust or built upon the competence-based trust initially established. Trust, as described by participants in this study, was a separate and explicit function of communication. We have placed it at the center of our adapted model because participants describe trust as necessary to the effectiveness of all other functions of communication, which in turn impact outcomes (Figure 1). It is possible that the importance of trust is specific to the Pakistani context or other settings in which initial mistrust could contribute to delayed diagnosis and abandonment of therapy. However, competence- and relationship-based trust have been previously described in literature from high-income countries and we hypothesize that this modified model, in which trust is unique and central to all other interrelated functions, might be applicable in other pediatric cancer settings. Further work exploring this hypothesis is warranted.

An assessment tool to measure these communication functions as experienced by caregivers and pediatric patients (PedCOM) has been previously developed and validated in the United States (13). This tool includes questions based on each function, some of which we have previously adapted and utilized during studies in Guatemala (5, 16). Given the relevance of this model to Pakistani populations, the tool and question items should be translated and adapted for further investigations of patient-centered communication in this setting.

Additionally, process models and interventions are needed to operationalize this functional model and apply it to improve care for children with cancer in Pakistan and around the world. There are very few communication interventions for children with cancer (34), and to our knowledge none that have been studied in Pakistan. Findings from this study might be used to inform process models and specific interventions aimed at improving communication and tailored to the Pakistani context.

This in-depth study explored communication functions in Pakistan, a setting where they have not been previously explored, using a model from existing literature. However, certain limitations should be considered as our findings are interpreted. We interviewed clinicians at 2 centers treating children with cancer in Pakistan and caregivers at only 1 site. While we believe the themes discussed are applicable to all centers in Pakistan and potentially pediatric cancer communication in other LMICs, further context specific work is needed. Additionally, all interviews were conducted around the time of diagnosis. Future work should explore how this model or specific communication functions might be perceived throughout the cancer care continuum. Finally, all data analysis was conducted in English which may have impacted our ability to interpret nuanced results.

Conclusion

Communication is essential to high-quality pediatric cancer care in low- and middle-income countries where it may improve trust in the medical team, enable parents to feel more comfortable making decisions and caring for their child at home, and decrease treatment abandonment. Our findings support the use of a functional model for communication in Pakistan and emphasize the importance of trust. Adaptation of existing measurement tools should be used to further investigate this model and culturally sensitive operationalization of all communication functions should influence interventions aimed at supporting the needs of caregivers and children with cancer in diverse settings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving human subjects was approved by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Indus Hospital and Health Network, and Children's Hospital Lahore. The study was conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided voluntary informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AA: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MR: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. AsN: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AtN: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. AtQ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CR: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SAH: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SJ: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JM: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St. Jude Children’s Hospital and by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant (CA21765). Additionally, this work was funded by a Conquer Cancer - Janssen Research & Development, LLC Career Development Awards in Health Equity. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the American Society of Clinical Oncology® or Conquer Cancer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1393908/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Peace of mind and sense of purpose as core existential issues among parents of children with cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2009) 163:519–24. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.57

2. Nyborn JA, Olcese M, Nickerson T, Mack JW. Don’t try to cover the sky with your hands”: parents’ Experiences with prognosis communication about their children with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. (2016) 19:626–31. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0472

3. Mack JW, Kang TI. Care experiences that foster trust between parents and physicians of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67:e28399. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28399

4. Stinson JN, Sung L, Gupta A, White ME, Jibb LA, Dettmer E, et al. Disease self-management needs of adolescents with cancer: perspectives of adolescents with cancer and their parents and healthcare providers. J Cancer Surviv. (2012) 6:278–86. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0222-1

5. Graetz DE, Rivas S, Wang H, Vedaraju Y, Ferrara G, Fuentes L, et al. Cancer treatment decision-making among parents of paediatric oncology patients in Guatemala: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e057350. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057350

6. Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. The evolution of regret: decision-making for parents of children with cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:1215–22. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04933-8

7. Sisk BA, Zavadil JA, Blazin LJ, Baker JN, Mack JW, DuBois JM. Assume it will break: parental perspectives on negative communication experiences in pediatric oncology. JCO Oncol Pract. (2021) 17:e859–71. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.01038

8. Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Kang TI, Geyer JR, Feudtner C, Dussel V, et al. Differences in parent-provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals of care among children with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:3005–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.4659

9. Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering [NIH Publication No. 07-6225]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute (2007).

10. Trivedi N, Moser RP, Breslau ES, Chou WS. Predictors of patient-centered communication among U.S. Adults: analysis of the 2017-2018 health information national trends survey (HINTS). J Health communication. (2021) 26:57–64. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2021.1878400

11. Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, Fiscella K, Hoerger M, Tancredi DJ, et al. Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: the VOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2017) 3:92–100. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373

12. Sisk BA, Friedrich A, Blazin LJ, Baker JN, Mack JW, DuBois J. Communication in pediatric oncology: A qualitative study. Pediatrics. (2020) 146. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1193

13. Sisk BA, Newman AR, Chen D, Mack JW, Reeve BB. Designing and validating novel communication measures for pediatric, adolescent, and young adult oncology care and research: The PedCOM measures. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2023) 70:e30685. doi: 10.1002/pbc.30685

14. Graetz DE, Garza M, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Mack JW. Pediatric cancer communication in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Cancer. (2020) 126:5030–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33222

15. Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:483–93. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4

16. Graetz DE, Rivas SE, Wang H, Vedaraju Y, Funetes AL, Caceres-Serrano A, et al. Communication priorities and experiences of caregivers of children with cancer in Guatemala. JCO Glob Oncol. (2021) 7:1529–36. doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00232

17. Williams AH, Rivas S, Fuentes L, Caceres-Serrano A, Ferrara G, Reeves T, et al. Understanding hope at diagnosis: A study among Guatemalan parents of children with cancer. Cancer Med. (2023) 12:9966–75. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5725

18. Graetz DE, Caceres-Serrano A, Radhakrishnan V, Salaverria CE, Kambugu JB, Sisk BA. A proposed global framework for pediatric cancer communication research. Cancer. (2022) 128:1888–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34160

19. Brown O, Ten Ham-Baloyi W, van Rooyen DR, Aldous C, Marais LC. Culturally competent patient-provider communication in the management of cancer: An integrative literature review. Glob Health Action. (2016) 9:33208. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.33208

20. Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. (2006) 64:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.014

21. Basbous M, Al-Jadiry M, Belgaumi A, Sultan I, Al-Haddad A, Jeha S, et al. Childhood cancer care in the Middle East, North Africa, and West/Central Asia: A snapshot across five countries from the POEM network. Cancer Epidemiol. (2021) 71:101727. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101727

22. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

23. Mack JW, Grier HE. The day one talk. J Clin Oncol. (2004) 22:563–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.078

24. Ptacek JT, Ptacek JJ. Patients’ perceptions of receiving bad news about cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2001) 19:4160–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4160

25. Weaver MS, Arora RS, Howard SC, Salaverria CE, Liu Y-L, Ribeiro RC, et al. A practical approach to reporting treatment abandonment in pediatric chronic conditions. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2015) 62:565–70. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25403

26. Weaver MS, Howard SC, Lam CG. Defining and distinguishing treatment abandonment in patients with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2015) 37:252–6. doi: 10.1097/mph.0000000000000319

27. Friedrich P, Lam CG, Itriago E, Perez R, Ribeiro RC, Arora RS. Magnitude of treatment abandonment in childhood cancer. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0135230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135230

28. Graetz D, Rivas S, Fuentes L, Caceres-Serrano A, Ferrara G, Antillon-Klussmann F, et al. The evolution of parents’ beliefs about childhood cancer during diagnostic communication: a qualitative study in Guatemala. BMJ Glob Health. (2021) 6. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004653

29. Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int J Transgend Health. (2023) 24:1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

30. Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. (2011) 9:100–3. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239

31. Kaye EC, Kiefer A, Blazin L, Spraker-Perlman H, Clark L, Baker JN, et al. Bereaved parents, hope, and realism. Pediatrics. (2020) 145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2771

32. Sisk B. Baker JN. A model of interpersonal trust, credibility, and relationship maintenance. Pediatrics. (2019) 144. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1319

33. Hillen MA, Onderwater AT, van Zwieten MC, de Haes HC, Smets EM. Disentangling cancer patients’ trust in their oncologist: a qualitative study. Psychooncology. (2012) 21:392–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1910

Keywords: pediatrics, cancer, communication, decision-making, global health

Citation: Graetz DE, Ahmad A, Raza MR, Hameed A, Naheed A, Najmi A, Quanita At, Munir S, Ahmad S, Ferrara G, Staples C, Rodriguez Galindo C, Ahmer Hamid S, Jeha S and Mack JW (2024) Functions of patient- and family-centered pediatric cancer communication in Pakistan. Front. Oncol. 14:1393908. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1393908

Received: 29 February 2024; Accepted: 08 August 2024;

Published: 11 September 2024.

Edited by:

M. Tish Knobf, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jana Pressler, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United StatesYvette Renee Harris, Miami University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Graetz, Ahmad, Raza, Hameed, Naheed, Najmi, Quanita, Munir, Ahmad, Ferrara, Staples, Rodriguez Galindo, Ahmer Hamid, Jeha and Mack. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dylan E. Graetz, ZHlsYW4uZ3JhZXR6QHN0anVkZS5vcmc=

Dylan E. Graetz

Dylan E. Graetz Alia Ahmad

Alia Ahmad Muhammad Rafie Raza3

Muhammad Rafie Raza3 Afia tul Quanita

Afia tul Quanita Gia Ferrara

Gia Ferrara Carlos Rodriguez Galindo

Carlos Rodriguez Galindo Syed Ahmer Hamid

Syed Ahmer Hamid Sima Jeha

Sima Jeha