95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Oncol. , 15 April 2024

Sec. Thoracic Oncology

Volume 14 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1378530

Eleonora Faccioli1*†

Eleonora Faccioli1*† Federica Grosso2†

Federica Grosso2† Andrea Dell’Amore1

Andrea Dell’Amore1 Sara Delfanti2

Sara Delfanti2 Giovanni Zambello1

Giovanni Zambello1 Luigi Cerbone2

Luigi Cerbone2 Gianluca Canu1

Gianluca Canu1 Antonina De Angelis2

Antonina De Angelis2 Viola Sambataro1

Viola Sambataro1 Federica Pezzuto3

Federica Pezzuto3 Paola Barbieri4

Paola Barbieri4 Giulia Pasello5,6

Giulia Pasello5,6 Fiorella Calabrese3

Fiorella Calabrese3 Federico Rea1

Federico Rea1The role of immunotherapy in the multimodal treatment for pleural mesothelioma (PM) is still under investigation, particularly in the preoperative setting. Pathological complete response (pCR) has been previously described after chemotherapy and immunotherapy; however, there is no prior experience reported with immunotherapy alone before surgery. We report the case of a 58-year-old male with biphasic PM treated with immunotherapy, resulting in a major clinical partial response. Following a multidisciplinary evaluation between thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, pathologists, radiologists and radiation oncologists, the patient underwent surgery with radical intent through a right extended pleurectomy/decortication (eP/D). Histopathological examination of the specimen confirmed a pathological Complete Response (pCR). This case supports the feasibility and potential efficacy of combining preoperative immunotherapy with surgery in the management of advanced PM.

Pleural mesothelioma is a rare and aggressive disease associated with asbestos exposure, presenting significant challenges in its treatment (1). As of today, when surgical intervention is feasible, the most recommended approach is multimodal, typically involving preoperative platinum-based chemotherapy plus pemetrexed. Subsequently, a surgical procedure (pleurectomy/decortication or extra-pleural pneumonectomy) is performed to achieve a macroscopic complete resection (MCR). This can be followed by adjuvant radiotherapy or immunotherapy as part of clinical trials (1). In recent years, immunotherapy has emerged as a promising treatment for patients affected by unresectable PM, especially for those with non-epithelioid histology (2, 3). Other ongoing trials are evaluating immunotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy in the preoperative settings for resectable PM, but this approach has not yet received approval. Here, we present the case of a patient affected by biphasic epithelioid PM with unresectable disease treated with up-front immunotherapy, based on Nivolumab 360 mg + Ipilimumab 80 mg (five cicles). Due to the major radiological response and patient’s good performance status, after multidisciplinary discussion between thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, pathologists, radiologists and radiation oncologists and adequate patient information, we decided to proceed with radical surgery.

The patient has expressed a written informed consent to be involved in clinical studies.

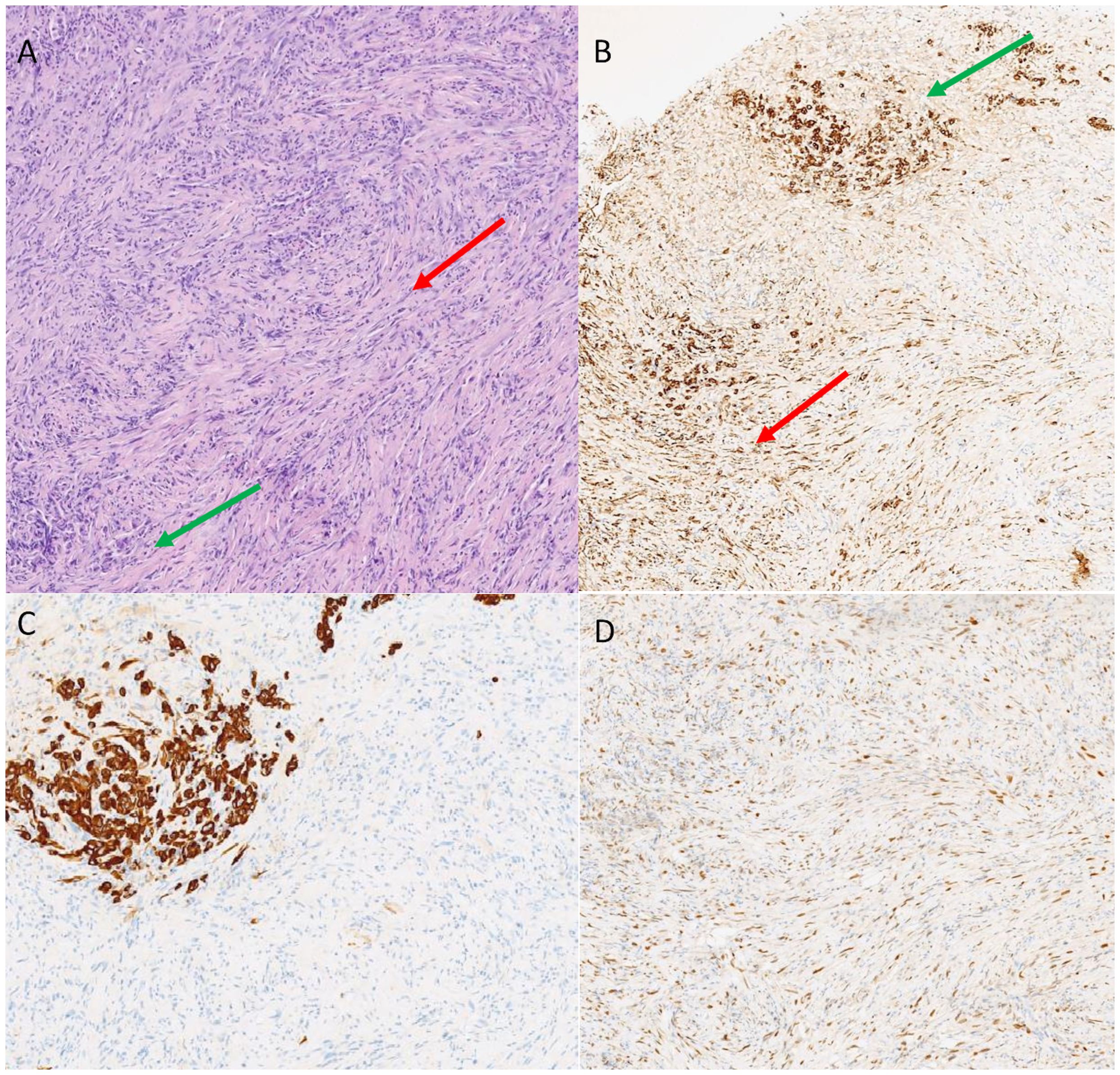

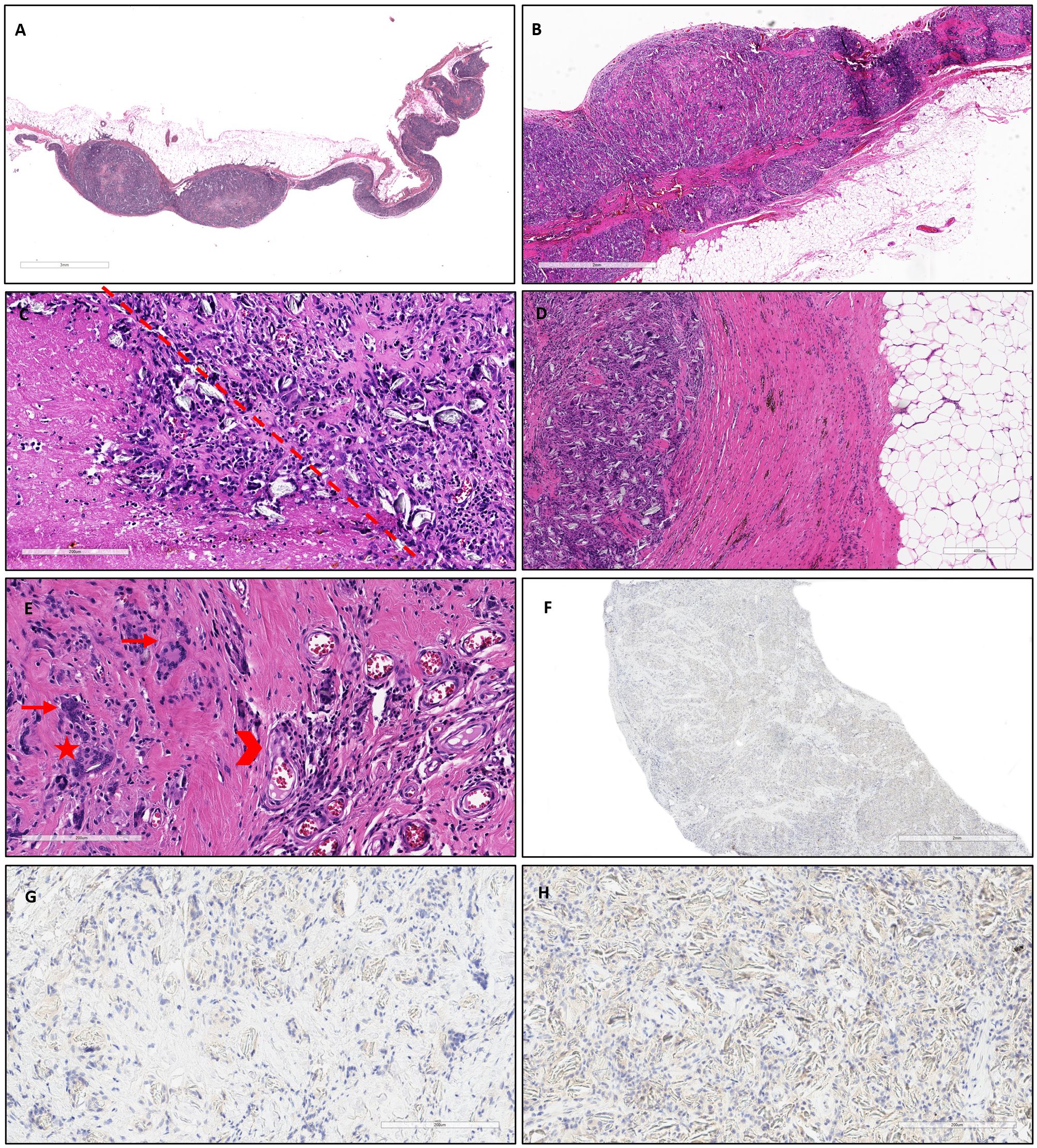

A 58-year-old male patient, former smoker (30 pack/year) with an history of environmental asbestos exposure, presented with pain in the right hypochondrium along with cough and exertional dyspnea. A chest X-ray revealed right-pleural effusion. A subsequent computed tomography (CT)-scan showed diffuse thickening of the right pleural with nodular components, accompanied by pleural effusion. PET-CT scan revealed diffuse pathological uptake in the right pleura but showed no evidence of metastatic disease in other sites. The patient underwent a CT-guided pleural biopsy with the diagnosis of epithelioid PM but since the histotype was not consistent with the radiological aspect of the disease, the patient underwent pleural biopsies and chemical pleurodesis through video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). According to current guidelines (1), based on morphology and immunohistochemistry, the final diagnosis confirmed a biphasic mesothelioma, with a minor (less than 5%) component of spindle cells (Figure 1). Due to the histology and the high disease burden (mRECIST at diagnosis 139 mm), the patient was deemed unresectable. Following guidelines, immunotherapy with Nivolumab 360 mg and Ipilimumab 80 mg was prescribed and administered for five courses. Mild diarrhea, related to the treatment, and episodes of atrial fibrillation, likely related to the proximity of the disease to the pericardium, were the only reported adverse events during treatment. The CT scan performed after the second course showed consistent tumor shrinkage (mRECIST 15 mm), a finding confirmed at the subsequent tumor reassessment after the fourth course (mRECIST 14 mm) (Figure 2). Considering the significant radiological partial response, the patient’s age, and good performance status, a multidisciplinary discussion of the case and in-depth discussion with the patient, deemed him eligible for surgery. A right extended pleurectomy/decortication with mediastinal lymph node dissection was performed. After sampling the entire specimen and conducting serial sections for each block, histological examination revealed diffusely thickened pleura with nodular structures, well-demarcated from subpleural fat tissue. Foci of necrosis within the nodules, alongside granulomatous inflammation, were observed at higher magnification. Intense fibrosis, lymphomonocytic inflammation, and focal hemosiderin deposition were evident, along with fibrosis, neoangiogenesis, and infiltration of multinucleated cells with cholesterol clefts. Immunostaining for cytokeratin (MNF116) was negative. Based on these findings, a pathological complete response (pCR) was reported (Figure 3). The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged in good clinical conditions after eleven days. At six months after surgery, the patient is alive with no signs of recurrence and metastasis.

Figure 1 Hematoxylin and eosin staining identified both the epitelioid (green arrow) and sarcomatoid (red arrow) components (A). Immunostaining for pancytokeratin was positive for both the components (green arrow, epithelioid; red arrow, sarcomatoid, B). CK5 identified the epithelioid component (C) while GATA 3 the sarcomatoid (D).

Figure 2 Chest computed tomography scan of the patient before (A) and after four cycles of immunotherapy (nivolumab and ipilimumab) (B). In image A, the red arrow indicates the significant pleural thickening, while in B, the green arrow highlights the substantial reduction in the disease burden.

Figure 3 At low magnification, the pleura was diffusely thickened with some nodular structures (A, hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar: 3 mm) and well demarcated with respect to the subpleural fat tissue (B, hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar: 2 mm). At higher magnification, several foci of necrosis were detected within the nodules (left side of the dot-line), alongside granulomatous foreign body inflammation (C, hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar: 200 µm). The granulomatous component was separated from the underlying adipose tissue by intense fibrosis, with lymphomonocytic inflammation and focal hemosiderin deposition (D, hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar: 400 µm). Additionally, fibrosis, neoangiogenesis (arrowhead), and a predominant infiltration of multinucleated cells (arrows) with some cholesterol clefts (star) were observed (E, hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar: 200 µm). Immunostaining for cytokeratin, for detecting scattered tumor cells (MNF116) was negative (F, scale bar: 2 mm; G, H: scale bar: 200 µm).

We present a case of pCR in a patient with a biphasic PM who underwent eP/D following immunotherapy. Optimal treatment for PM requires thorough discussion within a multidisciplinary expert team and should only be undertaken in highly specialized centers. The precise histology on well representative samples is crucial to establish the optimal treatment approach: according to clinical practice guidelines (1) thoracoscopy is recommended to obtain adequate histology with deep biopsies from ideally three pleural sites and CT scan or ultrasound-guided biopsies should be considered good alternatives when thoracoscopy is not feasible or contraindicated. Patients with good performance status, non-sarcomatoid histology, and early-stage disease may be suitable for surgery as part of a multimodal treatment which invariably always includes chemotherapy and may also involve radiotherapy in selected cases (1, 4). In PM, clinical studies investigating the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) or chemotherapy (CT) combined with ICIs are currently ongoing. The only evidence regarding the use of PD-L1 CTLA4 blockade comes from a phase II window of opportunity trial primarily focused on evaluating intra-tumoral T cell infiltrates and tumor microenvironment (5). Ongoing trials, such as one associating pembrolizumab with defactinib (NCT04201145) and nivolumab with pemetrexed plus platin, (NCT04162015), are exploring these avenues.

In our case, the decision to start immunotherapy as first-line treatment was based on several aspects: first of all, as reported in the Checkmate 743, the response rate and the overall survival are significantly higher with immunotherapy rather than chemotherapy in non-epithelioid subtypes (3). Furthermore, due to regulatory rules, in case of no response to immunotherapy, we would still have the possibility to administer a second-line chemotherapy but in case of starting chemotherapy, the patient would have never had the possibility to receive immunotherapy. Giving the major partial radiological response, the young age and the good performance status, we decided to submit the patient to surgery with radical intent, through an extended pleurectomy/decortication, to achieve macroscopic complete resection of the disease.

Limited experiences with these agents before surgery are currently documented in short reports. Tostes et al. (6) reported a pCR in a patient with epithelioid PM who underwent surgery after neoadjuvant therapy with cisplatin, pemetrexed, and off-label pembrolizumab. While the concept of resectable PM is currently under debate (7), the utilization of ICIs or ICIs combined CT in the pre-operative setting holds promise for new therapeutic opportunities in PM. It is essential to note that, due to the rarity of this disease, the expertise of the center and diagnostic accuracy are crucial factors for achieving the best response.

In conclusion, we present the first case of a pCR in a patient with PM previously treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab. This case highlights the potential benefits of immunotherapy in a neoadjuvant setting for PM. Further studies are mandatory to enhance the pre-operative experience with ICIs, either alone or in combination with CT, and to better understand the optimal settings for utilizing these agents.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Due to the nature of the study (case report) ethical approval was waived. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

EF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AD: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SD: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LC: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GC: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ADA: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. VS: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FP: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FR: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The study was supported by ERA-NET TRANSCAN-3, TRANSCAN2021-047.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Popat S, Baas P, Faivre-Finn C, Girard N, Nicholson AG, Nowak AK, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33:129–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.11.005

2. Nowak AK, Lesterhuis WJ, Kok PS, Brown C, Hughes BG, Karikios DJ, et al. Durvalumab with first-line chemotherapy in previously untreated Malignant pleurale mesothelioma (DREAM). A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial with safety run-in. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:1213–23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30462-9

3. Baas P, Scherpereel A, Nowak A, Fujimoto N, Peters S, Tsao AS, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable Malignant pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743):a multicentre, randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2021) 397:385–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32714-8

4. Pasello G, Ceresoli GL, Favaretto A. An overview of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the multimodality treatment of Malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Treat Rev. (2013) 39:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.03.001

5. Lee HS, Jang HJ, Ramineni M, Wang DY, Ramos D, Choi JM, et al. A Phase II Window of Opportunity Study of Neoadjuvant PD-L1 versus PD-L1 plus CTLA-4 Blockade for Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. (2023) 29:548–59. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2566

6. Tostes FT, Zugman M, Paes VR, Schvartsman G. Complete pathological response after neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy in Malignant pleural mesothelioma. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:836751. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.836751

Keywords: pleural mesothelioma, surgery, pathological complete response, immunotherapy, multimodal treatment

Citation: Faccioli E, Grosso F, Dell’Amore A, Delfanti S, Zambello G, Cerbone L, Canu G, De Angelis A, Sambataro V, Pezzuto F, Barbieri P, Pasello G, Calabrese F and Rea F (2024) Pathological complete response in a patient with pleural mesothelioma treated with immunotherapy: a case report. Front. Oncol. 14:1378530. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1378530

Received: 29 January 2024; Accepted: 26 March 2024;

Published: 15 April 2024.

Edited by:

Paolo Bironzo, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Anand Singh, National Cancer Institute (NIH), United StatesCopyright © 2024 Faccioli, Grosso, Dell’Amore, Delfanti, Zambello, Cerbone, Canu, De Angelis, Sambataro, Pezzuto, Barbieri, Pasello, Calabrese and Rea. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eleonora Faccioli, ZWxlb25vcmEuZmFjY2lvbGlAdW5pcGQuaXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.