- 1College of Sports Science, Jishou University, Jishou, Hunan, China

- 2School of Nursing, Dalian University, Dalian, Liaoning, China

- 3Ophthalmology Department, Xuzhou First People’s Hospital, Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China

- 4School of Stomatology, Dalian University, Dalian, Liaoning, China

- 5The Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

- 6Medical School, Weifang University of Science and Technology, Weifang, Shandong, China

- 7Department of Pathology, Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

- 8College of Physical Education, Beibu Gulf University, Qinzhou, Guangxi, China

Purpose: To investigate the effects of various intervention approaches on cancer-related fatigue (CRF) in patients with breast cancer.

Method: Computer searches were conducted on PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP), and Wanfang databases from their establishment to June 2023. Selection was made using inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 77 articles were included to compare the effects of 12 interventions on patients with breast cancer.

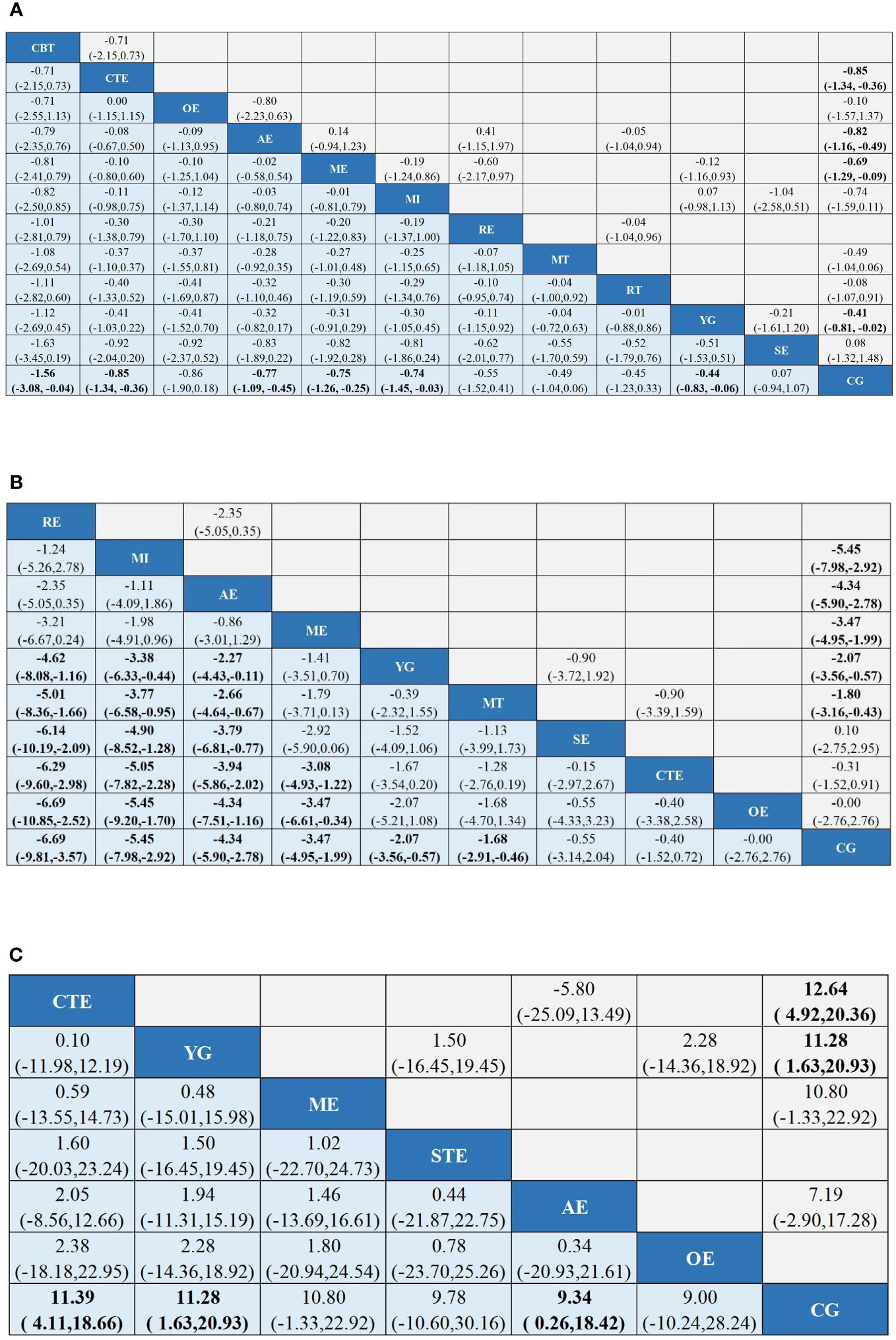

Results: Seventy-seven studies with 12 various interventions were examined. The network findings indicated that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (SMD, -1.56; 95%CI, -3.08~-0.04), Chinese traditional exercises (CTE) (SMD, -0.85; 95%CI, -1.34~-0.36), aerobic exercise (AE) (SMD, -0.77; 95%CI, -1.09~-0.45), multimodal exercise (ME) (SMD, -0.75; 95%CI, -1.26~-0.25), music interventions (MI) (SMD, -0.74; 95%CI, -1.45~-0.03), and yoga (YG) (SMD, -0.44; 95%CI, -0.83 to -0.06) can reduce CRF more than the control group (CG). For relaxation exercises (RE) (MD, -6.69; 95%CI, -9.81~-3.57), MI (MD, -5.45; 95%CI, -7.98~-2.92), AE (MD, -4.34; 95%CI, -5.90~-2.78), ME (MD, -3.47; 95%CI, -4.95~-1.99), YG (MD, -2.07; 95%CI, -3.56~-0.57), and mindfulness training (MD, -1.68; 95%CI, -2.91~-0.46), PSQI improvement was superior to CG. In addition, for CTE (MD, 11.39; 95%CI, 4.11-18.66), YG (MD, 11.28; 95%CI, 1.63-20.93), and AE (MD, 9.34; 95%CI, 0.26~18.42), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast improvement was superior to CG.

Conclusion: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most effective measure for alleviating CRF in patients with breast cancer and Relaxation exercises (RE) is the most effective measure for improving sleep quality. In addition, Chinese traditional exercises (CTE) is the best measure for enhancing quality of life. Additional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are expected to further investigate the efficacy and mechanisms of these interventions.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42023471574.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. The American Cancer Society reports a yearly increase of 0.5% in the incidence of breast cancer in women. The projection for 2022 estimates approximately 287,850 new cases of breast cancer in women in the United States, accounting for 31% of all new cancer diagnoses in women (1). In recent years, the survival rate of patients has improved due to the emergence of neoadjuvant therapy. However, survivors face a series of physical and mental problems, such as premature menopause, body image disorder, fatigue, and depression (2–4). Patients with breast cancer commonly experience cancer-related fatigue (CRF) as one of the most common symptoms (5). Before undergoing anticancer treatment, women with breast cancer may have already experienced fatigue. The occurrence of CRF is closely connected to the factors inherent to the primary tumor, which may be associated with the abnormal expression of certain substances released by the cancer cells in the patient, such as IL1, IL6, and TNF-a interferon. The severity of fatigue is proportional to the amount of interleukin released by tumor cells into the blood (6). When starting treatment, between 60% and 90% of women with breast cancer may experience fatigue (7). Severe fatigue is experienced by approximately a quarter of breast cancer survivors (8). An increase in the burden on patients’ families and caregivers can be caused by CRF. In addition, the time it takes for patients to return to work early after cancer treatment may be prolonged by CRF (9–13).

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in investigating CRF for breast cancer. The effects of aerobic exercise (AE), resistance exercise, relaxation training, yoga (YG), music, and other intervention methods on CRF in patients with breast cancer have been investigated in previous studies. Traditional meta-analyses have also demonstrated the effectiveness of YG and resistance training (RT) in reducing CRF in patients with breast cancer (14, 15). Olsson et al. offered a comprehensive overview of the effects of rehabilitation interventions and discovered that CRF was positively affected by exercise and YG (16). Health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors can be significantly impaired by the occurrence of CRF. Practical exercise training can enhance mitochondrial function and plasticity in patients, thereby improving the occurrence of CRF (17–19). However, evidence-based recommendations regarding the most effective type of intervention for improving CRF in patients with breast cancer are still lacking. Therefore, it is crucial to identify a suitable intervention for reducing CRF among complex interventions in patients with breast cancer.

Network meta-analysis (NMA), also called meta-analysis of mixed treatment comparisons or multiple treatment comparisons (20), offers a method to compare the size of the impact of various intervention types on CRF in patients with breast cancer by estimating direct and indirect comparisons. Although two previously published NMA studies were identified (21, 22), the study only reported on the effects of various exercise interventions, and no further studies were conducted on other intervention types. Consequently, this study aims to conduct an NMA on relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to compare the effects of various interventions on CRF in patients with breast cancer. The findings of this study are crucial for developing clinical practice guidelines recommending the best intervention to improve the outcome of CRF in patients with breast cancer.

Methods

This NMA was designed based on the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis (23), which are registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023471574).

Search strategies

Searches for RCT-related studies on CRF in breast cancer, published up to July 2023, were conducted using databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang. The search involved a combination of subject and free words. The search strategy can be found in Additional Document 1 (Appendix 1).

Study selection

In this study, YL and LG were selected as independent reviewers to screen the titles and abstracts of the retrieved literature using search strategies to identify literature that met the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, checks and discussions were performed by XA C to reach a consensus. Duplicate data were de-duplicated using EndNote software (24). A full-text assessment of potentially eligible studies was conducted based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any differences between the reviewers were resolved through discussion, and EndNote software was used to manage this phase.

Inclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included (1): Study type: RCT (2). Studies that included adult patients (18 years or older) diagnosed with breast cancer that were not limited to cancer stage and current treatment options for breast cancer (3); Interventions: AE, RT, Chinese traditional exercises (CTE), other exercise (OE), multimodal exercise (ME), YG, stretching exercise (STE), music interventions (MI), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness training (MT), and relaxation exercises (RE); and (4) Outcomes: at least one outcome measure. The primary outcome measure was CRF assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)-Fatigue Scale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQC30), Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS), Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale (SCFS), and Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (25). The secondary outcomes were sleep quality versus quality of life as measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B). Each intervention is defined in Additional Document 1 (Appendix 2). Each outcome measure is defined in Additional Document 1 (Appendix 3).

Exclusion criteria

(1) Patients with severe complications (2). Studies with outcomes that did not align with the design of this study (3). Studies with data that could not be integrated, such as incorrect or incomplete information.

Data extraction

The reviewers independently extracted the following data: first author, publication year, country, sample size, body mass index (BMI), age, weight, height, weight, intervention, tumor stage, intervention time, intervention frequency, and outcome indicators. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (LG and ZR Z) independently assessed the risk of bias, and a third reviewer adjudicated using Cochrane collaboration tools, such as sequence generation, assignment hiding, blinding, incomplete outcome data, non-selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias (26). Each criterion was judged to have a low, unclear, or high risk of bias (27).

Data analysis

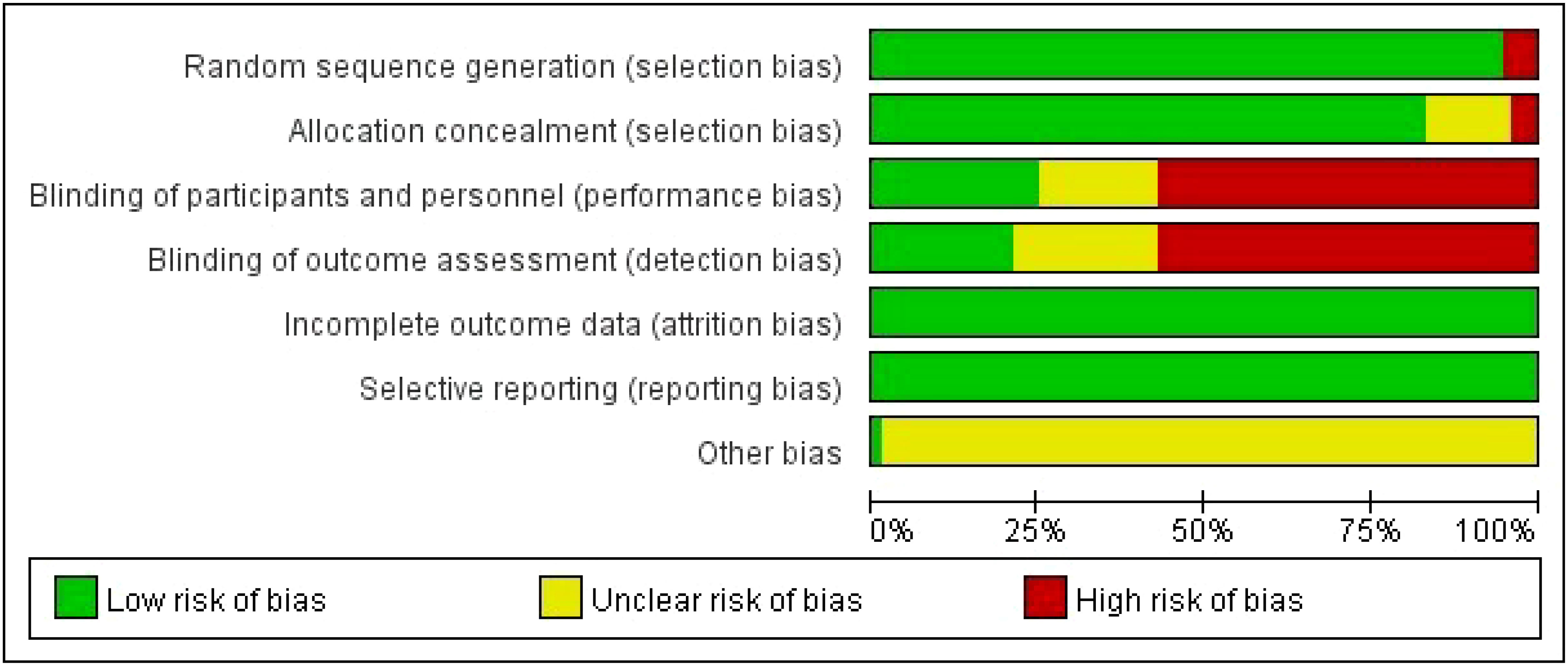

The “Netmeta” package (28) in R-4.2.1 software (29) was used for NMA. Network plots were generated using the STATA 15.1 “network plot” feature to describe and present various forms of motion. Nodes were used to represent various interventions, and edges were used to depict favorable intervention comparisons. Inconsistencies between direct and indirect comparisons were evaluated using the node segmentation method (30). Combined estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed using random effects network element analysis. In studies where the same unit of measurement was of interest, the mean difference (MD) was considered a treatment effect when analyzing the results or evaluating the standardized mean difference (SMD). Different exercise treatments were compared using a pairwise randomized effects meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of all pair-to-pair comparisons was evaluated using the I2 statistic, and publication bias was evaluated using the p-value of Egger’s test. Publication bias and secondary study effects, analyzed by the results of more than a dozen reported studies, were identified using funnel plots.

Results

Literature selection

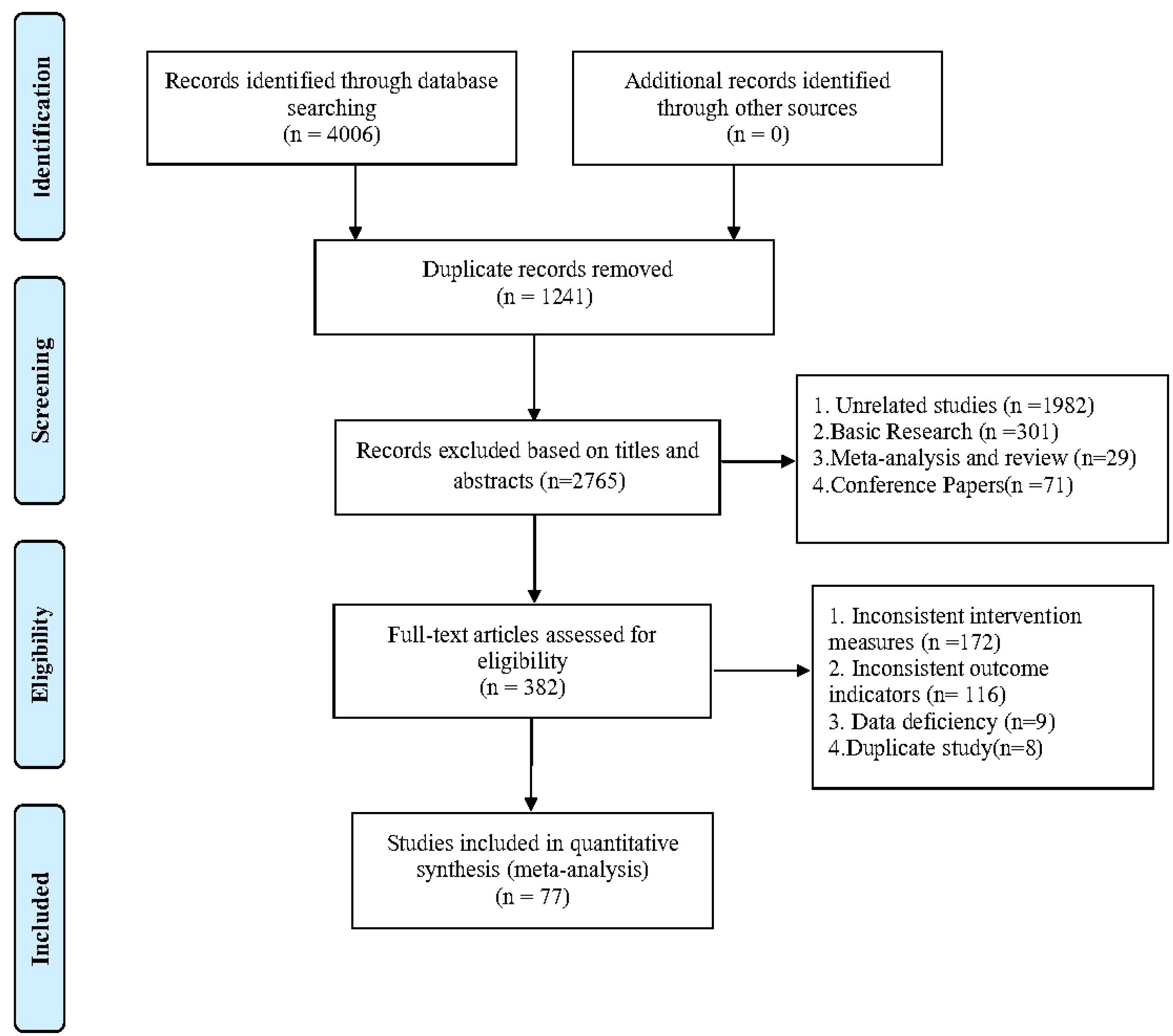

After removing duplicates, 4006 records were retrieved, and 3624 papers were discarded. The full text of the remaining 382 records was analyzed, and 305 cases did not satisfy the inclusion criteria: inconsistent intervention measures (172), inconsistent outcome indicators (31), data deficiency (9), and duplicate study (8). In the end, 77 (32–108) studies were included. Figure 1 shows the research flowchart. Articles from the full-text evaluation and the reasons for their exclusion are provided in Additional Document 1 (Appendix 8).

Study and participant characteristics

Studies comparing the effects of 12 various interventions on patients with breast cancer, published between 2001 and 2022, were included. The intervention durations ranged from 1 week to 12 months, and a total of 5,254 patients were reported in the included studies. Among these studies, 62 reported CFR, 23 reported PSQI, and 17 reported FACT-B. The participants had an average age of 18-73 years, an average BMI of 21.06 ± 2.26-72.3 ± 13.1, an average height of 145.64 ± 24.07-170.2 ± 5.4 cm, and an average weight of 54.74± 6.66-74.3 ± 17.0 Kg.

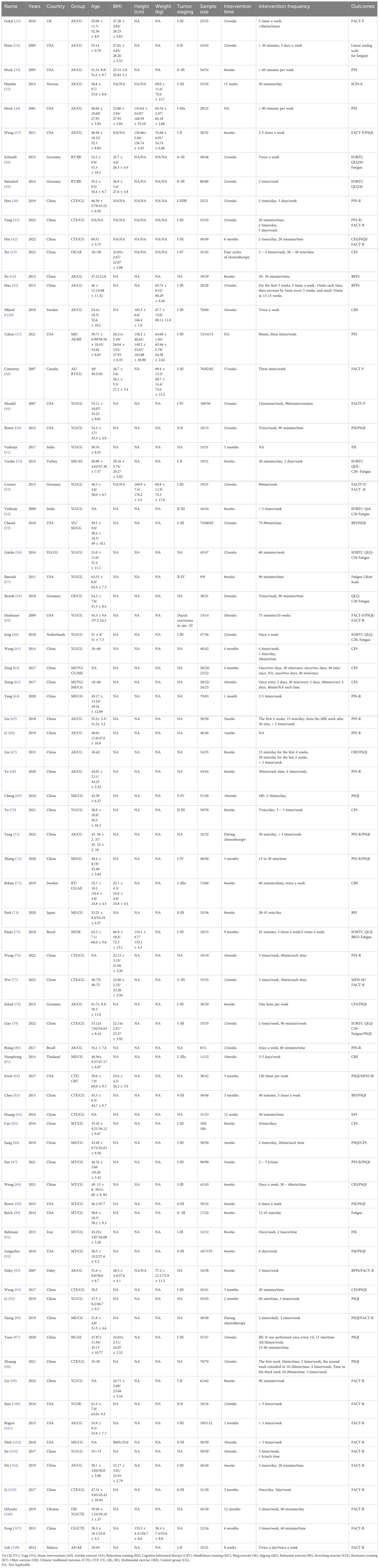

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies and participants. The risk of bias assessment for each study is presented in Additional Document 1 (Appendix 4), and Figure 2 presents the aggregated data.

Figure 2 Percentage of studies examining the efficacy of interventions in patients with breast cancer with low, unclear, and high risk of bias for each feature of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.

Outcomes

CRF

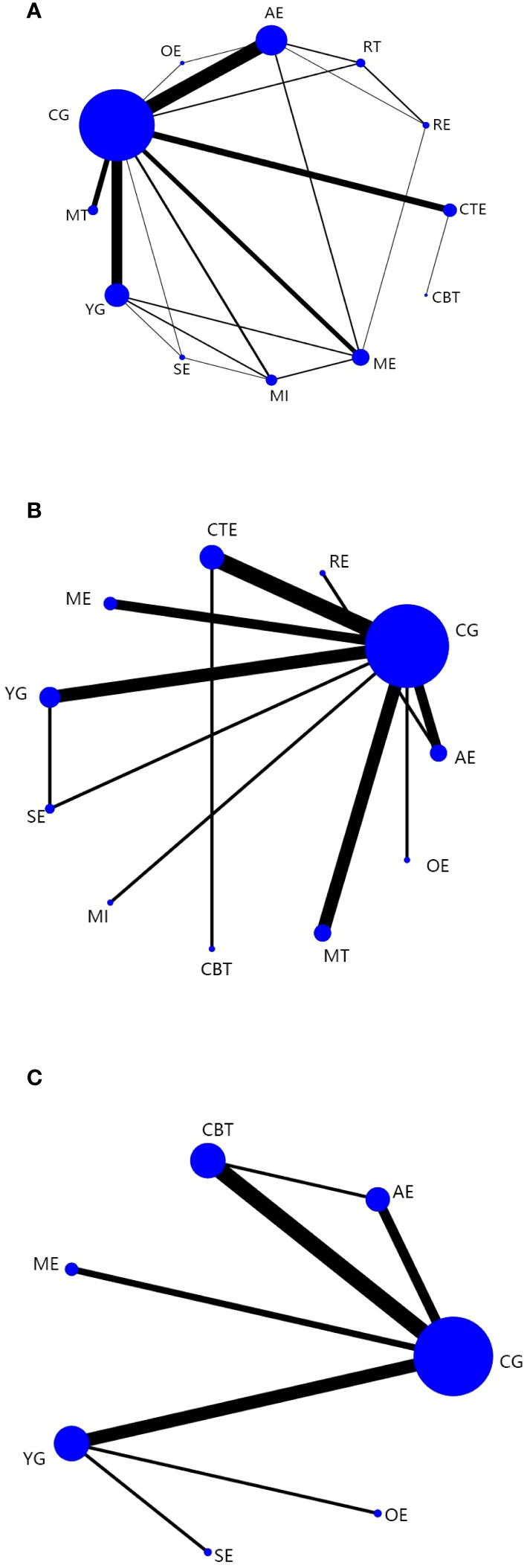

A total of 62 (32–94) studies, involving 5385 participants, assessed CRF. In the NMA, 12 interventions were included (Figure 3A): AE, CG, RT, RE, CTE, OE, ME, YG, SE, MI, CBT, and MT. Superior CFR improvement compared with CG was observed for CBT (SMD, -1.56; 95%CI, -3.08~-0.04), CTE (SMD, -0.85; 95%CI, -1.34~-0.36), AE (SMD, -0.77; 95%CI, -1.09~-0.45), ME (SMD, -0.75; 95%CI, -1.26~-0.25), MI (SMD, -0.74; 95%CI, -1.45~-0.03), and YG (SMD, -0.44; 95%CI, -0.83 to -0.06) (Figure 4A). Comparison of adjusted funnel plots did not provide evidence of significant publication bias, as confirmed by Egger’s test (P = 0.085) (Additional Document 1: Appendix 5.1). Heterogeneity, intransitivity, and inconsistencies in network meta-analyses were also evaluated (Additional Reference 1: Appendix 6.1). Furthermore, direct comparisons of the CRF were assessed. (Additional Reference 1: Appendix 7.1).

Figure 3 Network plots: Tai chi (TC), Yoga (YG), Music interventions (MI), Aerobic exercise (AE), Relaxation training (RE), Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Mindfulness training (MT), Sling exercise (SE), Qigong (QG), Baduanjin Exercise (BE), Stretching exercise (STE), Resistance training (RT), Other exercise (OE), Chinese traditional exercises (CTE), CTE (TC, QG, BE), Multimodal exercise (ME), Control group (CG). (A) is network plots of CRF. (B) is network plots of Sleep quality. (C) is network plots of Quality of Life. The size of the nodes represents the number of times the exercise appears in any comparison of that treatment, and the width of the edges represents the total sample size in the comparisons it connects.

Figure 4 League tables of outcome analyses: Tai chi (TC), Yoga (YG), Music interventions (MI), Aerobic exercise (AE), Relaxation training (RE), Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Mindfulness training (MT), Sling exercise (SE), Qigong (QG), Baduanjin Exercise (BE), Stretching exercise (STE), Resistance training (RT), Other exercise (OE), Chinese traditional exercises (CTE), CTE (TC, QG, BE), Multimodal exercise (ME), Control group (CG). (A) is the results of CRF's network meta-analysis. (B) is the results of Sleep quality's the network meta-analysis. (C) is the results of Quality of Life's the network meta-analysis. Data are mean differences and 95% credibility intervals for continuous data.

Sleep quality

In 23 (37, 42, 50, 55, 59, 67, 69, 71, 72, 78, 79, 82, 83, 86–89, 92, 94–98) studies, PSQI was assessed in 2334 participants. Eleven interventions were included in the NMA (Figure 3B): RE, MI, AE, ME, YG, MT, SE, CTE, OE, and CG. PSQI improvement was superior to YG for RE (MD, -4.62; 95%CI, -8.08~-1.16), MI (MD, -3.38; 95%CI, -6.33~-0.44), and AE (MD, -2.27; 95%CI, -4.43~-0.11). In addition, PSQI improvement was superior to MT for RE (MD, -5.01; 95%CI, -8.36~-1.66), MI (MD, -3.77; 95%CI, -6.58~-0.95), and AE (MD, -2.66; 95%CI, -4.64~-0.67). RE (MD, -6.14; 95%CI, -10.19~-2.09), MI (MD, -4.90; 95%CI, -8.52~-1.28), and AE (MD, -3.79; 95%CI, -6.81~-0.77) demonstrated superior PSQI improvement compared with SE. Furthermore, PSQI improvement was superior to CTE for RE (MD, -6.29; 95%CI, -9.60~-2.98), MI (MD, -5.05; 95%CI, -7.82~-2.28), AE (MD, -3.94; 95%CI, -5.86~-2.02), and ME (MD, -3.08; 95%CI, -4.93~-1.22). RE (MD, -6.69; 95%CI, -10.85~-2.52), MI (MD, -5.45; 95%CI, -9.20~-1.70), AE (MD, -4.34; 95%CI, -7.51~-1.16), and ME (MD, -3.47; 95%CI, -6.61~-0.34) demonstrated superior PSQI improvement compared to OE. Additionally, RE (MD, -6.69; 95%CI, -9.81~-3.57), MI (MD, -5.45; 95%CI, -7.98~-2.92), AE (MD, -4.34; 95%CI, -5.90~-2.78), ME (MD, -3.47; 95%CI, -4.95~-1.99), YG (MD, -2.07; 95%CI, -3.56~-0.57), and MT (MD, -1.68; 95%CI, -2.91~-0.46) demonstrated superior PSQI improvement compared to CG (Figure 4). Comparison of the adjusted funnel plot did not provide evidence of significant publication bias, as confirmed by Egger’s test (P = 0.744) (Additional document 1: Appendix 5.2). Heterogeneity, inaccessibility, and inconsistencies in the network meta-analyses were evaluated (Additional Reference 1: Appendix 6). In addition, direct comparisons of the PSQI scores were evaluated. (Additional Reference 1: Appendix 7.2).

Quality of life

A total of 17 (41, 42, 53, 59, 77, 93, 96, 99–108) studies evaluated FACT-B in 1372 participants. Seven interventions were included in the NMA (Figure 3C): CG, AE, ME, CBT, YG, SE, and OE. CTE (MD, 11.39; 95%CI, 4.11-18.66), YG (MD, 11.28; 95%CI, 1.63-20.93), and AE (MD, 9.34; 95%CI, 0.26~18.42) demonstrated superior FACT-B improvement compared with CG. (Figure 4C). The comparison of the adjusted funnel plots did not provide evidence of significant publication bias, as confirmed by Egger’s test (P = 0.365) (Additional document 1: Appendix 5.3). Heterogeneity, inaccessibility, and inconsistencies in network meta-analyses were also evaluated (Additional Reference 1: Appendix 6). In addition, direct comparisons of FACT-B were assessed (Additional Reference 1: Appendix 7.3).

Discussion

Breast cancer has the highest cancer incidence in women worldwide, and the survival rate of patients with breast cancer has been increasing. A range of side effects are often experienced by survivors of breast cancer, with CRF being a common side effect (109).

Several factors, including tumor stage, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgery, hormone therapy, radiation therapy dose, tumor burden, and the combination of these therapies, contribute to the development of CRF. Patients receiving cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil, adriamycin, or docetaxel experience more severe CRF than patients receiving paclitaxel alone (8, 110). An increase in the incidence of fatigue from 10% to 29% after treatment was observed in a cross-sectional study (111).

Furthermore, a patient’s CRF can be affected by factors such as family dysfunction, social support system, occupation, and hope level. Patients experiencing family dysfunction not only confront the physical pain induced by the disease and radiotherapy and chemotherapy but also endure the pressure arising from the family disorder, contributing to an increase in fatigue level (112). The onset of breast cancer and subsequent lifelong treatment impose medical burdens on patients, leading to emotional and role changes among some patient’s family members. This exacerbates the psychological burden and contributes to increased CRF (112). Sørensen HL et al. (113) discovered a close relationship between social support and physical and mental fatigue experienced by patients with breast cancer, with a stronger correlation observed for mental fatigue. Patients lacking social support face difficulties in receiving adequate support and assistance and struggle to effectively express sad emotions, leading to increased pressure on patients and a consequent worsening of fatigue. Yao Li et al. (114). found that farmers’ lower fatigue levels may be attributed to their low educational level, limited avenues for acquiring tumor-related knowledge, and higher expectations regarding disease prognosis. Furthermore, farmers may shoulder less social responsibility than patients with higher education, experiencing less social pressure, and exhibiting less noticeable fatigue. CRF has a tendency to persist and can result in dysfunction, reduced quality of life, and the emergence of negative emotions. Patients with breast cancer experience pain from CRF before or during treatment. Currently, a significant number of patients with breast cancer experience CRF, emphasizing the urgent need for its management.

Currently, numerous studies are focusing on improving CRF in breast cancer. This study conducted a literature search from 2001 to 2022, yielding 77 articles. Twelve various interventions (Aerobic exercise, Resistance training, Chinese traditional exercises, Other exercise, Multimodal exercise, Yoga, Stretching exercise, Music interventions, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Mindfulness training, Relaxation exercises, Control group) were analyzed to investigate their impact on patients with breast cancer and determine which intervention can effectively enhance CRF, alleviate depression, and improve quality of life in these patients.

The findings of this study indicate that CBT, CTE, AE, ME, MI, and YG were more effective than CG in improving CRF in patients with breast cancer. CBT can alter patients’ thinking, beliefs, and behaviors, correcting erroneous cognition and eliminating negative emotions through psychological treatment (115). Cognitive behavioral therapy can reduce CRF in patients with cancer through cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy, and psychological intervention. Clinical practice guidelines have recommended Cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce CRF in adults (116). The findings of this study are consistent with those of the traditional meta (117). In this study, we referred to Tai Chi, Qigong, and Baduanjin as Chinese traditional exercises. It was found that Chinese traditional exercises significantly improved CRF in patients with breast cancer compared to Control group. Tai Chi can regulate the nervous regions of the downstream stress response pathway by regulating the neuroendocrine system, including the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. This regulation impacts the production of inflammatory factors (31, 118), leading to the downregulation of inflammatory factors, improvement in the inflammatory environment of patients’ tumors, and alleviation of CRF. Furthermore, Tai Chi is typically performed in groups, fostering a strong sense of community and social support among participating patients. They can share difficult everyday experiences and feel comfortable facing similar adversities. Additionally, social support can play a crucial role in buffering patients’ stress (119). Social support can enhance patients’ self-management ability, coping ability, and quality of life, including CRF (120). CTE regulates the respiratory system, enhances physiological function, promotes metabolism, and improves physical fitness, which can improve CRF in patients with breast cancer to a certain extent.

A relatively severe symptom burden caused by cancer diagnosis and treatment leads to patients being prone to sleep disorders (121). Sleep disorders affect more than 50% of patients with cancer, with some experiencing persistent and recurring sleep disorders within one year of completing treatment. Prolonged sleep disorders exacerbate patients’ pain, fatigue, psychological pain, and other symptoms, significantly affecting their quality of life and prognosis (122, 123).

This study discovered that Relaxation exercises, Music interventions, Aerobic exercise, and Multimodal exercise were more likely to improve the sleep quality of patients with breast cancer than Chinese traditional exercises, Other exercise, and Control group. Relaxation exercises regulates the function disturbed by tension stimulation, promotes muscle relaxation, reduces the arousal level of the cerebral cortex, and facilitates falling asleep through consciously repeated exercises of muscle tension and relaxation. Music interventions can affect the release of morphine peptides and other substances in the body and slow down negative emotions associated with sleep disorders, such as anxiety and depression, to improve sleep quality (117). Furthermore, Music interventions can regulate the body and mind of patients, inducing relaxation and guiding them into a relaxed and happy state, which contributes positively to stabilizing emotions and relieving pain. Relaxation exercises and Music interventions are also cost-effective and easy to practice. Using Relaxation exercises is recommended to improve sleep in patients with breast cancer and those experiencing sleep disorders. Moreover, this study observed that Chinese traditional exercises, Yoga, and Aerobic exercise were more effective than Control group in improving patients’ quality of life.

Study strengths and limitations

This review has several advantages. First, mesh meta-analysis was used to directly and indirectly compare various interventions. Notably, more accurate interventions were included and meticulously classified into 12 various interventions, with each being defined. The effects of various intervention methods on CRF, PSQI, and quality of life were examined, along with the investigation of additional intervention measures. The findings of this study can be used as an optimal reference.

However, certain limitations exist in this study. First, the duration, intensity, and frequency of the interventions were not considered. Second, the implementation quality of the blind approach in the included literature is not high, and the outcome indicators are all subjective, lacking objective indicators. A description of the biological parameters should be added. Third, only Chinese–English literature was included, which may have resulted in heterogeneity. Fourth, all the studies were small sample studies; therefore, it is recommended to conduct future studies with large samples. Finally, in this study, the effects of tumor stage, patient treatment, patient’s psychological status, and patient’s family situation on CRF were not considered, which will have a particular impact on the results of this study.

Conclusion

Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses strongly recommends CBT for improving CRF in patients with breast cancer. RE and CTE are recommended to enhance the quality of sleep in patients with breast cancer. This study includes limited results, and it is recommended that future investigations include more studies to further validate the findings and select appropriate interventions based on the circumstances of patients with breast cancer.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LG: Data curation, Writing – original draft. RL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. JZ: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft. ZZ: Data curation, Writing – original draft. SL: Writing – original draft, Data curation. XC: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources. TL: Writing – review & editing, Resources. JL: Writing – review & editing, Resources. ZW: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1341927/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin (2022) 72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708

2. Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol (2005) 23:3322–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130

3. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol (2000) 18:743–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743

4. Ganz PA. Monitoring the physical health of cancer survivors: a survivorship-focused medical history. J Clin Oncol (2006) 24:5105–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0541

5. Nowe E, Friedrich M, Leuteritz K, Sender A, Stöbel-Richter Y, Schulte T, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and associated factors in young adult cancer patients. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol (2019) 8:297–303. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2018.0091

6. Wang Z, Qi F, Cui Y, Zhao L, Sun X, Tang W, et al. An update on Chinese herbal medicines as adjuvant treatment of anticancer therapeutics. Biosci Trends (2018) 12:220–39. doi: 10.5582/bst.2018.01144

7. Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S. Breast cancer and fatigue. Sleep Med Clin (2008) 3:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.10.011

8. Abrahams HJG, Gielissen MFM, Schmits IC, Verhagen C, Rovers MM, Knoop H. Risk factors, prevalence, and course of severe fatigue after breast cancer treatment: a meta-analysis involving 12 327 breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol (2016) 27:965–74. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw099

9. Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol (2001) 19:3385–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385

10. Phillips SM, McAuley E. Physical activity and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a panel model examining the role of self-efficacy and depression. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2013) 22:773–81. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0983

11. Carlson MA, Fradgley EA, Bridge P, Taylor J, Morris S, Coutts E, et al. The dynamic relationship between cancer and employment-related financial toxicity: an in-depth qualitative study of 21 Australian cancer survivor experiences and preferences for support. Support Care Cancer (2022) 30:3093–103. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06707-7

12. Bøhn SH, Vandraas KF, Kiserud CE, Dahl AA, Thorsen L, Ewertz M, et al. Work status changes and associated factors in a nationwide sample of Norwegian long-term breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv (2022). doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01202-2

13. Tran TXM, Jung SY, Lee EG, Cho H, Cho J, Lee E, et al. Long-term trajectory of postoperative health-related quality of life in young breast cancer patients: a 15-year follow-up study. J Cancer Surviv (2023) 17:1416–26. doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01165-4

14. Dong B, Xie C, Jing X, Lin L, Tian L. Yoga has a solid effect on cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2019) 177:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05278-w

15. Gray L, Sindall P, Pearson SJ. Does resistance training ameliorate cancer-related fatigue in cancer survivors? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil (2023) 1–10. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2023.2226408

16. Olsson Möller U, Beck I, Rydén L, Malmström M. A comprehensive approach to rehabilitation interventions following breast cancer treatment - a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Cancer (2019) 19:472. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5648-7

17. Invernizzi M, de Sire A, Lippi L, Venetis K, Sajjadi E, Gimigliano F, et al. Impact of rehabilitation on breast cancer related fatigue: A pilot study. Front Oncol (2020) 10:556718. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.556718

18. Penna F, Ballarò R, Costelli P. The redox balance: A target for interventions against muscle wasting in cancer cachexia? Antioxid Redox Signal (2020) 33:542–58. doi: 10.1089/ars.2020.8041

19. Idorn M, Thor Straten P. Exercise and cancer: from "healthy" to "therapeutic"? Cancer Immunol Immunother (2017) 66:667–71. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1985-z

20. Bafeta A, Trinquart L, Seror R, Ravaud P. Reporting of results from network meta-analyses: methodological systematic review. Bmj (2014) 348:g1741. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1741

21. Wu PY, Huang KS, Chen KM, Chou CP, Tu YK. Exercise, nutrition, and combined exercise and nutrition in older adults with sarcopenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Maturitas (2021) 145:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.12.009

22. Liu YC, Hung TT, Konara Mudiyanselage SP, Wang CJ, Lin MF. Beneficial exercises for cancer-related fatigue among women with breast cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) (2022) 15(1):151. doi: 10.3390/cancers15010151

23. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev (2015) 4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

24. Kali A, Srirangaraj S. EndNote as document manager for summative assessment. J Postgrad Med (2016) 62:124–5. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.174158

25. Meneses-Echávez JF, González-Jiménez E, Ramírez-Vélez R. Supervised exercise reduces cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review. J Physiother (2015) 61:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2014.08.019

26. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

27. Jardim PSJ, Rose CJ, Ames HM, Echavez JFM, Van de Velde S, Muller AE. Automating risk of bias assessment in systematic reviews: a real-time mixed methods comparison of human researchers to a machine learning system. BMC Med Res Methodol (2022) 22:167. doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01649-y

28. Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Krahn U, König J. netmeta: Network meta-analysis with R.2018 . Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/netmeta/index.html.

29. R Development Core Team. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2017). Available at: http://www.R-project.org.

30. Rücker G, Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol (2015) 15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0060-8

31. Fronza MG, Baldinotti R, Fetter J, Rosa SG, Sacramento M, Nogueira CW, et al. Beneficial effects of QTC-4-MeOBnE in an LPS-induced mouse model of depression and cognitive impairments: The role of blood-brain barrier permeability, NF-κB signaling, and microglial activation. Brain Behav Immun (2022) 99:177–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.10.002

32. Gokal K, Wallis D, Ahmed S, Boiangiu I, Kancherla K, Munir F. Effects of a self-managed home-based walking intervention on psychosocial health outcomes for breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer (2016) 24:1139–66. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2884-5

33. Pinto BM, Frierson GM, Rabin C, Trunzo JJ, Marcus BH. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol (2005) 23:3577–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.080

34. Mock V, Frangakis C, Davidson NE, Ropka ME, Pickett M, Poniatowski B, et al. Exercise manages fatigue during breast cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology (2005) 14:464–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.863

35. Husebø AM, Dyrstad SM, Mjaaland I, Søreide JA, Bru E. Effects of scheduled exercise on cancer-related fatigue in women with early breast cancer. ScientificWorldJournal (2014) 2014:271828. doi: 10.1155/2014/271828

36. Mock V, Pickett M, Ropka ME, Muscari Lin E, Stewart KJ, Rhodes VA, et al. Fatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise during cancer treatment. Cancer Pract (2001) 9:119–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009003119.x

37. Wang YJ, Boehmke M, Wu YW, Dickerson SS, Fisher N. Effects of a 6-week walking program on Taiwanese women newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Nurs (2011) 34:E1–13. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181e4588d

38. Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Armbrust P, Schneeweiss A, Ulrich CM, Steindorf K. Effects of resistance exercise on fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Cancer (2015) 137:471–80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29383

39. Steindorf K, Schmidt ME, Klassen O, Ulrich CM, Oelmann J, Habermann N, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of resistance training in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy: results on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Ann Oncol (2014) 25:2237–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu374

40. Qiong H, Willow, Shuangyan H, Minghui Z, Simin H, Hui X. Study on the influence of eight forms of Taijiquan on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer. J Guangxi Univ Chin Med (2019) 22:30–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4441.2019.04.011

41. liu Y, Qiong H, Hui X, Xianhua Q, Ligang W, Liuyin C, et al. Observation of curative effect of simple Taijiquan on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer and influence of inflammatory factors. J Guizhou Univ Chin Med (2022) 44:29–34.

42. Hui RU, Zhou Z, Jianfeng S. Effect observation of social support combined with Taijiquan exercise in elderly patients with breast cancer after surgery. Nurs Pract Res (2022) 19:1268–72. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9676.2022.09.002

43. Rong X, Ruijun L, Wenlin C, Good A. Effects of dance exercise therapy on cancer fatigue and nutritional status in young and middle-aged breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Chin J Pract Nurs (2022) 38:1074–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn211501-20210609-01636

44. Ying X. Effect of home aerobic exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer outpatient patients undergoing chemotherapy. Hainan Med (2012) 23:145–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2012.19.064

45. Nan H, Grass P, Xiaoyun K, Libin G. Nursing study on the influence of aerobic exercise on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer. Nurs Pract Res (2013) 10:4–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9676.2013.12.002

46. Mijwel S, Backman M, Bolam KA, Jervaeus A, Sundberg CJ, Margolin S, et al. Adding high-intensity interval training to conventional training modalities: optimizing health-related outcomes during chemotherapy for breast cancer: the OptiTrain randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2018) 168:79–93. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4571-3

47. Cohen J, Rogers WA, Petruzzello S, Trinh L, Mullen SP. Acute effects of aerobic exercise and relaxation training on fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A feasibility trial. Psychooncology (2021) 30:252–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.5561

48. Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Friedenreich CM, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25:4396–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024

49. Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, Harris MS, Patel SR, Hall CB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25:4387–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027

50. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer (2012) 118:3766–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702

51. Vadiraja HS, Rao RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Patil S, Diwakar RB, et al. Effects of yoga in managing fatigue in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Palliat Care (2017) 23:247–52. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_95_17

52. Vardar Yağlı N, Şener G, Arıkan H, Sağlam M, İnal İnce D, Savcı S, et al. Do yoga and aerobic exercise training have impact on functional capacity, fatigue, peripheral muscle strength, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Integr Cancer Ther (2015) 14:125–32. doi: 10.1177/1534735414565699

53. Cramer H, Rabsilber S, Lauche R, Kümmel S, Dobos G. Yoga and meditation for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors-A randomized controlled trial. Cancer (2015) 121:2175–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29330

54. Vadiraja SH, Rao MR, Nagendra RH, Nagarathna R, Rekha M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of yoga on symptom management in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga (2009) 2:73–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.60048

55. Chaoul A, Milbury K, Spelman A, Basen-Engquist K, Hall MH, Wei Q, et al. Randomized trial of Tibetan yoga in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer (2018) 124:36–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30938

56. Lötzke D, Wiedemann F, Rodrigues Recchia D, Ostermann T, Sattler D, Ettl J, et al. Iyengar-yoga compared to exercise as a therapeutic intervention during (Neo)adjuvant therapy in women with stage I-III breast cancer: health-related quality of life, mindfulness, spirituality, life satisfaction, and cancer-related fatigue. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med (2016) 2016:5931816. doi: 10.1155/2016/5931816

57. Banasik J, Williams H, Haberman M, Blank SE, Bendel R. Effect of Iyengar yoga practice on fatigue and diurnal salivary cortisol concentration in breast cancer survivors. J Am Acad Nurse Pract (2011) 23:135–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00573.x

58. Strunk MA, Zopf EM, Steck J, Hamacher S, Hallek M, Baumann FT. Effects of kyusho jitsu on physical activity-levels and quality of life in breast cancer patients. In Vivo (2018) 32:819–24. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11313

59. Danhauer SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, Campbell CR, Felder L, Daley K, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: findings from a randomized pilot study. Psychooncology (2009) 18:360–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1503

60. Jong MC, Boers I, Schouten van der Velden AP, Meij SV, Göker E, Timmer-Bonte A, et al. A randomized study of yoga for fatigue and quality of life in women with breast cancer undergoing (Neo) adjuvant chemotherapy. J Altern Complement Med (2018) 24:942–53. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0191

61. Guofei W, Shuhong W, Pinglan J, Chun Z. Intervention effect of yoga on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. J Cent South Univ (Medical) (2014) 39:1077–82. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2014.10.016

62. Jinfang Z. Effect of yoga combined with music relaxation training on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Electronic J Pract Clin Nurs (2017) 2:1–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2096-2479.2017.19.001

63. Dongyang X, Mei W, Hao W, Jie L, Jia L, Zhongru C. Effect of yoga combined with music relaxation training on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Chin J Modern Nurs (2017) 23:184–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2907.2017.02.009

64. Min Y, Yanni D, Jing X, Effect W, Lan L, Jing Z. Application effect of exercise intervention on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Clin Med Res Pract (2020) 5:161–3. doi: 10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.202031057

65. Jiali L. Effect of exercise intervention on cancer-induced fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. World J Sleep Med (2018) 5:792–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7130.2018.07.013

66. Xuanzhi L, Huiying L, Huizhen H, Liangsheng S. Effect of exercise intervention on cancer-induced fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. World J Sleep Med (2019) 6:1311–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7130.2019.09.057

67. Lina L, Lihua Z, Hongxia F, Xiangyun S. Effect of exercise intervention on cancer-related fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Gen Nurs (2015) 13:2190–1. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4748.2015.22.030

68. Xin Y. Observation on the effect of aerobic exercise on cancer-induced fatigue in patients with breast cancer treated with radiotherapy. Chin Med Guide (2020) 18:95–6.

69. Li C, Jie Z, Yan W, Yamei W, Hongfang L, Xiaomei L. Effect of music therapy combined with aerobic exercise on sleep quality in patients with chemotherapy after radical breast cancer surgery. Nurs Manage China (2016) 16:989–94. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2016.07.030

70. Ximei Y. Effects of rehabilitation yoga exercises combined with emotional nursing on cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer. Chin convalescent Med (2021) 30:1185–9. doi: 10.13517/j.cnki.ccm.2021.11.020

71. Li Y. To analyze the effects of exercise intervention on cancer-induced fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. World J Sleep Med (2022) 9:1414–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7130.2022.08.011

72. Jiang Z, Yan L, Wenhui L, Xijuan Z, Zhengting C, Qiongyao G, et al. Effects of bedtime music therapy on sleep quality and cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer radiotherapy. J Kunming Med Univ (2020) 41:173–8. doi: 10.12259/j.issn.2095-610X.S20201248

73. Bolam KA, Mijwel S, Rundqvist H, Wengström Y. Two-year follow-up of the OptiTrain randomised controlled exercise trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2019) 175:637–48. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05204-0

74. Park S, Sato Y, Takita Y, Tamura N, Ninomiya A, Kosugi T, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological distress, fear of cancer recurrence, fatigue, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer-A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage (2020) 60:381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.02.017

75. Paulo TRS, Rossi FE, Viezel J, Tosello GT, Seidinger SC, Simões RR, et al. The impact of an exercise program on quality of life in older breast cancer survivors undergoing aromatase inhibitor therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes (2019) 17:17. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1090-4

76. Yanbing W, Zhongguo C, Li Z, Wanping L, Jianling Z, Zhonghai W, et al. Intervention effect of Baduanjin and pattern-doudou diabolo on breast cancer patients after surgery. J Hebei North Univ (Natural Sci Edition) (2022) 38:16–19+22.

77. Wei X, Yuan R, Yang J, Zheng W, Jin Y, Wang M, et al. Effects of Baduanjin exercise on cognitive function and cancer-related symptoms in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer (2022) 30:6079–91. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07015-4

78. SChad F, Rieser T, Becker S, Groß J, Matthes H, Oei SL, et al. Efficacy of tango argentino for cancer-associated fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancers (Basel) (2023) 15(11):2920. doi: 10.3390/cancers15112920

79. Liao J, Chen Y, Cai L, Wang K, Wu S, Wu L, et al. Baduanjin's impact on quality of life and sleep quality in breast cancer survivors receiving aromatase inhibitor therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Front Oncol (2022) 12:807531. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.807531

80. Boing L, Baptista F, Pereira GS, Sperandio FF, Moratelli J, Cardoso AA, et al. Benefits of belly dance on quality of life, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer - A pilot study of a non-randomised clinical trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther (2018) 22:460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.10.003

81. Naraphong W, Lane A, Schafer J, Whitmer K, Wilson BRA. Exercise intervention for fatigue-related symptoms in Thai women with breast cancer: A pilot study. Nurs Health Sci (2015) 17:33–41. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12124

82. Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, Sadeghi N, Nicassio P, Ganz PA, et al. Tai chi chih compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia in survivors of breast cancer: A randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol (2017) 35:2656–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0285

83. Chen Z, Meng Z, Milbury K, Bei W, Zhang Y, Thornton B, et al. Qigong improves quality of life in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer: results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer (2013) 119:1690–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27904

84. Huang SM, Tseng LM, Chien LY, Tai CJ, Chen PH, Hung CT, et al. Effects of non-sporting and sporting qigong on frailty and quality of life among breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs (2016) 21:257–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.10.012

85. Xin C, Huan Z, Ling L. A study of mindfulness training intervention on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients after chemotherapy. Chongqing Med Sci (2016) 45:2953–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-8348.2016.21.022

86. Zhen JJ, Ping MX. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction training on perceived stress and cancer-related fatigue in patients with advanced breast cancer. Clin Educ Gen Pract (2019) 17:575–6. doi: 10.13558/j.cnki.issn1672-3686.2019.03.033

87. Fanbenben. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on cancer-related fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Chin school doctor (2021) 35:111–3.

88. Jinmei W, Huiyuan M, Yalan S. Effects of mindfulness relaxation training on fear of cancer recurrence, cancer-related fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer. Oncol Clin Rehabil China (2021) 28:228–33.

89. Brown CH, Max L, LaFlam A, Kirk L, Gross A, Arora R, et al. The association between preoperative frailty and postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analgesia (2016) 123:430–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001271

90. Reich RR, Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Shivers SC, Schell MJ, Shelton MM, et al. Baseline immune biomarkers as predictors of MBSR(BC) treatment success in off-treatment breast cancer patients. Biol Res Nurs (2014) 16:429–37. doi: 10.1177/1099800413519494

91. Rahmani S, Talepasand S. The effect of group mindfulness - based stress reduction program and conscious yoga on the fatigue severity and global and specific life quality in women with breast cancer. Med J Islam Repub Iran (2015) 29:175.

92. Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Paterson CL, Ramesar S, Park JY, Alinat C, et al. Examination of broad symptom improvement resulting from mindfulness-based stress reduction in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol (2016) 34:2827–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7874

93. Daley AJ, Crank H, Saxton JM, Mutrie N, Coleman R, Roalfe A. Randomized trial of exercise therapy in women treated for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25:1713–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5083

94. Yingying W. Effect of Taijiquan on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life in middle-aged and elderly patients with breast cancer after surgery thesis]. Anhui Normal University (2017).

95. Jing L. Effects of yoga combined with meditation training on cancer-related fatigue and negative emotions in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Clin Nurs China (2019) 11:284–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-3768.2019.04.003

96. Ping X. Application effect of music therapy combined with aerobic exercise in postoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer patients. Chin Contemp Med (2019) 26:214–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4721.2019.14.064

97. Taohua Y, Weiwei F, Guangling H. Effects of relaxation training combined with aerobic exercise on psychological adjustment, cancer-related fatigue and sleep quality in patients with breast cancer. Guangdong Med (2020) 41:1373–7. doi: 10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx.20191342

98. Ling ZY. Study of Baduanjin alleviating cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer thesis]. Qingdao University (2021).

99. Liu W, Liu J, Ma L, Chen J. Effect of mindfulness yoga on anxiety and depression in early breast cancer patients received adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2022) 148:2549–60. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04167-y

100. Stan DL, Croghan KA, Croghan IT, Jenkins SM, Sutherland SJ, Cheville AL, et al. Randomized pilot trial of yoga versus strengthening exercises in breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue. Support Care Cancer (2016) 24:4005–15. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3233-z

101. Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Anton PM, Hopkins-Price P, Verhulst S, Vicari SK, et al. Effects of the BEAT Cancer physical activity behavior change intervention on physical activity, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2015) 149:109–19. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3216-z

102. Dieli-Conwright CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Sami N, Lee K, Sweeney FC, et al. Aerobic and resistance exercise improves physical fitness, bone health, and quality of life in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res (2018) 20:124. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-1051-6

103. Cuifeng J, Lili W, Bei W. Effect of yoga exercise on cancer-induced fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Integrated Nurs (Chinese Western Medicine) (2017) 3:12–5. doi: 10.11997/nitcwm.201704004

104. Ping D, Zheng Z, Yao L, Li F. Clinical effect of aerobic exercise on oxygen carrying capacity and quality of life of breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Rehabil China (2019) 34:596–8. doi: 10.3870/zgkf.2019.11.010

105. Qun L, Fang WL, Xin Z. Effect of Baduanjin on mood and quality of life of patients undergoing radiotherapy after radical breast cancer surgery. Gen Nurs (2017) 15:2257–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4748.2017.18.033

106. Odynets T, Briskin Y, Todorova V. Effects of different exercise interventions on quality of life in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther (2019) 18:1534735419880598. doi: 10.1177/1534735419880598

107. Fong SS, Ng SS, Luk WS, Chung JW, Chung LM, Tsang WW, et al. Shoulder mobility, muscular strength, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors with and without tai chi qigong training. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med (2013) 2013:787169. doi: 10.1155/2013/787169

108. Loh SY, Lee SY, Murray L. The Kuala Lumpur Qigong trial for women in the cancer survivorship phase-efficacy of a three-arm RCT to improve QOL. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2014) 15:8127–34. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.19.8127

109. Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A, Breitbart WS, Carpenter KM, Cella D, et al. Cancer-related fatigue, version 2. 2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2015) 13:1012–39. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0122

110. Lundh Hagelin C, Wengström Y, Fürst CJ. Patterns of fatigue related to advanced disease and radiotherapy in patients with cancer-a comparative cross-sectional study of fatigue intensity and characteristics. Support Care Cancer (2009) 17:519–26. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0502-5

111. Berger AM, Gerber LH, Mayer DK. Cancer-related fatigue: implications for breast cancer survivors. Cancer (2012) 118:2261–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27475

112. Junwei M, Yimei Z, Shan Y, Ping L. Longitudinal study of cancer-induced fatigue trajectories and influencing factors in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Chin J Pract Nurs (2022) 38:1121–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn211501-20210929-02734

113. Sørensen HL, Schjølberg TK, Småstuen MC, Utne I. Social support in early-stage breast cancer patients with fatigue. BMC Womens Health (2020) 20:243. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-01106-2

114. Li Y, Yan W, Yang Y, Shurui J, Key H. Longitudinal study on the trajectory and influencing factors of cancer-induced fatigue in patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Nurs Manage China (2022) 29:795–802. doi: 10.12025/j.issn.1008-6358.2022.20220271

115. An H, He RH, Zheng YR, Tao R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol (2017) 1010:321–9. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5562-1_16

116. Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, Breitbart W, Escalante CP, Ganz PA, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol (2014) 32:1840–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495

117. Liping T, Xiaoqing W, Fan T, Shaowen Z, Yuzhu Z, Qianjun C. Cognitive behavioral therapy improves cancer-related fatigue in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Chongqing Med Sci (2020) 49:3985–90. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-8348.2020.23.028

118. O'Higgins CM, Brady B, O'Connor B, Walsh D, Reilly RB. The pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue: current controversies. Support Care Cancer (2018) 26:3353–64. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4318-7

119. Yeh GY, Chan CW, Wayne PM, Conboy L. The impact of tai chi exercise on self-efficacy, social support, and empowerment in heart failure: insights from a qualitative sub-study from a randomized controlled trial. PloS One (2016) 11:e0154678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154678

120. Yan D, Jing L, Lizhen L, Jingli F. Effects of social support, coping style and depression on quality of life in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis based on structural equation model. Int J Nurs Sci (2022) 41:2028–32. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn221370-20200818-00523

121. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, et al. Colon cancer, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2021) 19:329–59. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012

122. Reynolds-Cowie P, Fleming L. Living with persistent insomnia after cancer: A qualitative analysis of impact and management. Br J Health Psychol (2021) 26:33–49. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12446

Keywords: breast cancer, CFR, network meta-analysis, cancer, systematic review

Citation: Li Y, Gao L, Chao Y, Lan T, Zhang J, Li R, Zhang Z, Li S, Lian J, Wang Z and Chen X (2024) Various interventions for cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 14:1341927. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1341927

Received: 21 November 2023; Accepted: 17 January 2024;

Published: 09 February 2024.

Edited by:

Kevin Ni, St George Hospital Cancer Care Centre, AustraliaReviewed by:

Arianna Folli, Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale, ItalySemra Bulbuloglu, Istanbul Aydın University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2024 Li, Gao, Chao, Lan, Zhang, Li, Zhang, Li, Lian, Wang and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoan Chen, ODEyNTU3NDUzQHFxLmNvbQ==; Zhaofeng Wang, MjcwOTk0NDE3QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Ying Li

Ying Li Lei Gao

Lei Gao Yaqing Chao3†

Yaqing Chao3†