94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Front. Oncol., 27 March 2023

Sec. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.991791

This article is part of the Research TopicEarly Palliative Care for Cancer PatientsView all 11 articles

Background: Research in PC (Palliative Care) is frequently challenging for patient’s frailty, study design, professional misconceptions, and so on. Little is known about specificity in PC research on Hematologic cancer patients, who have distinct characteristics that might influence the enrollment process.

Aims: What works, how and for whom, in increasing enrollment in studies in PC on patients with hematologic malignancies?

Methods: Realist review: a qualitative review whose goal is to identify and explain the interaction between Contexts, Mechanisms, and Outcomes (CMOs). The theory was informed by a narrative, theory-based literature research, including an initialsystematic research, and the addition of papers suggested by experts of the field. We also used 7 interviews with experts in PC about patients with hematologic malignancies research and our own experience from a PC pilot study on patients with hematologic malignancies to refine the initial theory.

Results: In our initial theory we hypothesize that:

- Access to palliative care could be beneficial to hematologic patients, even in early stages

- Hematologists tend to under-use palliative care services in general, due to unpredictable disease trajectories and cultural barriers.

- These factors may negatively impact the patients’ enrollment in PC research

We included secondary literature as narrative reviews, if they presented interesting propositions useful for our theoretical construction. 23 papers met our inclusion criteria.

We also searched for relevant CMOs impacting referral in palliative care, and we selected a list of CMOs that could be relevant also in hematology. We accordingly theorized a group of interventions that could increase the enrollment in PC research and presented them using “social exchange theory” (SET) as a theoretical framework.

Prominent researchers in PC in hematologic malignancies were interviewed on their opinion on our results, and additional CMOs.

Conclusions: Before conducting research in PC on patients with hematologic malignancies, it’s probably advisable to assess:

- The perception of the different actors (physicians, nurses, other professionals involved), in particular the hematologists, in terms of pros and cons of referral to PC and enrollment in PC trials

- The existing relationship between PC and the Hematology department

Accordingly, it’s possible to tailor different interventions on the various actors and choose a model of trial to increase the perception of benefits from PC and, consequently, enrollment.

In this section we are presenting the known difficulties met when recruiting PC (palliative care) patients in research projects, and the goal of this paper: investigating how these difficulties apply to PC patients with hematologic malignances. We used the realist (see Box 1) approach for this, as we developed an Initial theory (presented at the beginning of the “results” section) and we “refined it” through an evidence informed process, consisting of different steps (see “data collection and analysis” in “materials and methods” section) and produced a more refined, final theory of what works, for whom and in what circumstances in enrollment of palliative care patients with hematological malignances (reported at the end of the “results” section).

Box 1 Glossary of terms of realist methodology.

Realism: theory-driven research approach, which produces evidence-informed theories, to better understand how an intervention works, for whom and under what circumstances, through the search for underpinning mechaninsms (“retroduction”).

CMO configuration:

Context: environmental backdrop elements of an intervention or program (ig: laws, cultural norms). Context in realist theory describes “in what circumstances and why interventions or programs ‘work’”.

Mechanism: resources offered in a specific context (ig: information) and reactions of people involved (ig: trust or engagement). It should provide an “an explanatory account of how and why programs gives rise to outcomes”.

Outcome: effects of specific mechanisms in a defined context, both intended or unintended (ig: adherence to a treatment).

Initial Rough theory (IRT): hypothesis of underpinning mechanisms in a program or intervention, usually, in the form of “if…then” statements, that need to be furtherly tested.

Refined theory: theorization resulting from the testing of IRT through the analysis of the gathered evidence.

Patients with advanced hematological malignancies suffer from a very high symptom burden and psychological, spiritual, social, and physical symptoms comparable with patients with metastatic non-hematological malignancy (1–4).

In agreement with the new World Health Organization recommendation (5) the evidence from studies performed in patients with solid tumors and hematologic patients’ symptom burden suggests that an earlier and integrated provision of specialized palliative care has the potential to improve their quality of life and reduce resource consumption through effective management of psychological and physical symptoms, appropriate relationships, effective communication, and support in decision-making. Palliative Care study design must take into account intrinsic methodological challenges, such as the unpredictability of disease progression, recruiting difficulties, and high attrition rates (6). Moreover, outcome measures that assessed the acceptance of the study by the participants were frequently absent (7) and RCT (Randomized Controlled Trial) design may be more frequently connected with people who are unwilling to be enrolled, aseven the use of words like “randomization” and “placebo” (6), can be negatively perceived by the patients. In the other hand,a language perceived as clear, and non-technical in that specific culture, and the use of words more oriented to symptom management then to palliation could have a positive impact.

Trials encountered enrollment challenges; for example, the consent approach rate in the ENABLE III trial of early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative care was 44%, with a variety of reasons given by approached patients for declining participation (7, 8).

Thespecialist’s opinion about the experimental arm involved in the trial proposal can also influence the enrollment (6, 9).

If they have the perception of “failing the patient”, or adding burden, or if they lack faith in the proposed intervention, when referring to palliative care, because they lack faith in the specific research or intervention proposed, fears to speak about prognosis, or perceive the enrollment procedure as too demanding for the usual care staff, this might have a negative impact on the overall enrollment (10). In their study, White et al. state that over three quarters of interviewed patients stated that they would be interested in trial participation if their doctor made it clear that he/she was keen for participation (6). The absence of symptoms can decrease patients’ motivation, and in general patients need to see some relevant potential personal gain, as the access to additional care or a better symptom management (when they are already present), or feel that their contribution can be helpful to others. Organizational factors can also have an effect, such as if the patient must attend multiple visits or travel further to receive the offered service.

Little is known about specific research in PC regarding hematologic cancer patients.

Studies showed heterogeneity in the population, PC intervention, disease trajectory and treatment phase (11). Only in the last 2 years some evidences on effectiveness arose on high symptomatic hospitalized patients by EL-Jawahri et al. (12).

Following the WHO recommendation, we initially developed a PC intervention integrated with standard hematological care (13). This pilot study was primarily focused on assessing the feasibility of the PC intervention. Secondary aims included exploring its acceptability by patients, professionals and caregivers and collecting preliminary information on its effectiveness. Our study design was discussed with hematology colleagues to better understand how to propose it and the inclusion criteria suitable for the feasibility trial including patients at their last active treatment (see Table 1).

However, the enrollment for this protocol has been difficult; it started in November 2018 with patients and caregivers; we enrolled 15 patients in 3 years.

It’s essential for our research team to understand the reason for this low accrual, related to patients, professionals, trial itself or organization. We believe it should be interesting to compare our experience with other realities all over the world.

In this paper we described a realist synthesis (14, 15) (read Box 1 for details on realist methodology), based on our previous Review, a rapid review on Hematologic cancer patient and research in Palliative Care (final check March 2022) and experts ‘opinion on PC trials for hematologic cancer patients.

Eventually, We (11) integrated these data with our experience.

Hence, the aims of the current study were:

● to provide an overview of difficulties in patients enrollment in palliative care studies, specifically in hematologic malignancies, exploring the experts’ point of view, literature overview, our experience.

● to elaborate a realist synthesis of enrollment in palliative care intervention for hematologic cancer patients

The results of this study might be relevant for developing structured intervention proposals regarding hematologic cancer patients in PC trials or to give some suggestions to our colleagues involved in research protocol in this complex topic.

With this in mind, as expected by the realist approach, we aimed at producing a theoretical contribution, starting from an “Initial Rough Theory” (IRT) at the beginning of the process and finishing with a more refined version of it, as a result of our research work.

The process that we followed could be considered a process of realist synthesis; we decided to include secondary studies in our revision, which is not typical, and we tested our Initial rough theory with an independent study.

This part of the process is compatible with the realist logic, but it’s not a fixed stage of usual research strategies in realist synthesis. We considered as our guide for this manuscript the “Quality standards for realist synthesis for researchers and peer-reviewers” (16, 17) of the Rameses project.

According to realist analysis methodology, our first literature consultation aimed at the development of a rough theory (IRT), that further research and expert consultation aimed to refine the IRT, focusing on what seems to work better, for whom, and how, describing it through Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) configurations (see Box 1 “glossary of terms of realist methodology”).

The initial rough theory was based on a previous systematic revision of literature from our team (11) and our knowledge from our personal experience in conducting a trial on PC with hematologic patients (see Table 1 “Our intervention: difficulties met, and initiatives taken in response”).

We then better specified our focus and decided to extend our search of possible mechanisms that might have an impact on the enrollment process to contiguous fields. In addition to the search for CMOs regarding the enrollment of hematologic patients into PC studies, we searched for articles describing CMOs relevant in the referral to palliative care in hematological patients. (Research strategy reported in Table 2, where we reported both the shift of focus of our research and the correspondent article selection process, as suggested in “quality standards for realist synthesis”, standard 5 and 6) (17). This is an example of “progressive focusing”, a well-established technique in qualitative research in which the focus of the inquiry is iteratively clarified by reflection on emerging data (50).

We derived an interview guide (see appendix 1 “the interview guide”) to collect data about the different research teams that are conducting similar studies. The interview was developed following the recommendations by the RAMESES project for “realist interviews” (17, 51).

Steps in developing our final theory were shown in Figure 1 “phases of research”.

They were:

● STEP 1: we developed our IRT starting from literature review on Early Palliative Care and Hematologic cancer patients and our experience in a pilot feasibility trial

● STEP 2: we searched for relevant palliative care studies conducted with hematologic patients and for ongoing trials.

We analyzed the available materials (published papers, protocols and abstract), using an appraisal process in which we made a first selection based on abstract’s pertinence, and then a second appraisal rating the full-text articles based on their relevance (“high”, “medium”, “low”, “none”). Study characteristics (e.g. sample type and size, type of research, grade of evidence) and theoretical contribution (e.g. ‘how’, ‘why, ‘in what circumstances’) were tabulated on an Excel spreadsheet.

● STEP 3: we developed a list of the retrieved CMOs, linking them to the different studies, to have an operative summary of the main mechanism that seemed likely to have an impact on hematologic studies’ enrollments (see appendix 2).

● STEP 4: we developed an interview guide based on the CMOs’ list and the suggested guidelines for authors’ interviews in realist evaluations; we then contacted the authors of the research that we analyzed to gather additional information on their studies and to compare our findings with the experts’ opinion (see appendix 1).

In October 2020, we sent a first email to ask the availability for an interview; in December 2020 -March 2021 we conducted 7 interviews to the researchers involved in palliative care on patients with hematologic malignancies interventions. GM conducted audio-recorded phone interviews with key informants of researcher teams, purposively selected according to the following characteristics: having conducted a palliative care study on hematologic cancer patients published in literature, trials ongoing (referring to trial.gov registration, last research July 2020) or published research protocols. Two experts were also contacted based on their works presented in congresses’ abstract. The semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim by GM. The authors of the 2 trials ongoing did not answer to our invitation.

Both authors searched the transcripts and the articles for possible context, mechanisms, ad outcomes configurations that could emerge and refine the initial rough theory (see Table 3).

This Research project did not include the collection, processing, or analysis of personal or sensitive data of an interested party. Accordingly, the research did not require review or approval by the Ethics Committee. Nevertheless, specific participant protection procedures were adopted: researchers asked participants to agree to participate in the survey and interviews on a voluntary basis by email, and to give their informed consent orally during the audio registered phone call.

We developed our IRT through a published systematic review (11) and the testing in our context through a trial (13). We tried to apply some suggested improvements during the enrolment of our research study: some attentions were planned just from the beginning of the study and others were added during the enrolment process (see Table 1 “our intervention”).

Enrollment in palliative interventions have its difficulties, but hematology has some specific obstacles, leading to additional difficulties to enrollment and subsequent development of new high-quality knowledge.

Additional features that might negatively impact enrollment in PC interventions on patients with hematologic malignancies probably are:

● Difficulty in prognostication by hematologists:

● Disease development: uncertainty in its trajectory (also for the advent of potential lifesaving therapies-as CAR T-cell) and consequently on referring to PC.

● On the other end, patients suitable of a PC intervention were identified between very “end of life” population (life expectancy of days/few weeks)

● Defining target population: Difficulty to understand which hematologic population could benefit most from PC service, based on patients’ needs as perceived by hematologists

● Organizational challenges: especially for ambulatory outpatients, it’s hard to keep in mind the possibility of enrollment in non-pharmacological protocol through ordinary care. Moreover, sometimes clinicians needed to start the allegedly last line of therapy in a really short time, and palliative care evaluation and randomization was not possible

We refined our initial theory through a) literature research for relevant mechanisms and b) interviews to experts in the fields.

We are presenting our results based both on their source of retrieval (“CMOs literature research” and “CMOs in interviews”), and as our “refined theory”, a possible global theorization of how the different CMOs might be theoretically related.

In our literature research, we selected some relevant mechanisms that might have an impact on the enrollment process. We hypothesize that if hematologists do not refer to PC at the same time, they don’t enroll in a palliative care trial.

So, for the aim of this project we wrote 2 tables (see appendix 2):

CMO on patterns on referral to PC by hematologists

CMO on specific patterns on PC research for hematologic cancer patients

This group of CMOs focuses on the difficulties of referring to PC by hematologists and the mechanisms which have an impact on it.

Some of these M regard the model of integration between hematology and PC and other organizational difficulties: strict criteria to access to hospice, for example, lack of space and time to discuss about PC, hospital culture focused on curing, being in different department and not having access 24/24 hours to PC service, could reduce referral to PC. A linear (from beginning to end) model more than a sequential one (PC only when hematologic care is concluded) could improve PC referral as having clear leadership on patients between the 2 staffs. Poor communication between staffs is detrimental even for PC referral.

Relation between hematologist and pc professionals with reciprocal acknowledgment could improve PC referral, not seeing referring to PC as a failure or a deskilling. Perceived self-efficacy by hematologists and misconceptions about palliative care could reduce referral to PC service. The term PC itself could be avoided. Patient’s conditions as asymptomatic patients or patients with unrealistic expectations could reduce the integration between the 2 staffs. Hematologic patients could have specific needs not addressed by PC and unexpected disease trajectory makes difficult to recognize PC needs. Hematologists difficulties to propose a consultant inside a long-time relationship with patient, late end of life discussions and unrealistic expectations from active treatments could reduce PC referral by hematologists.

In this group we analyzed mechanisms suggested from the scarce literature on enrolment in PC for hematologic cancer patients (7, 18, 35–37). The mechanisms underlying the low enrollment seem to be quite similar to the well-known mechanisms in PC in general (8, 9, 38–42, 52, 53), with some more specificity regarding this subgroup as the difficulty to define a clear prognosis. Identifying patients with highest supportive needs may improve feasibility and acceptability of future primary palliative care in hematologic malignancy trials. Moreover, lack of patient interest in the topic of palliative care research also potentially affected the feasibility.

The interviews with expert partially agreed with the results from the literature, but they also contributed to add some significant insight into our research question (see Table 3 “interviews’ mechanisms” and Table 4 “interviewers characteristics”). Experts’ interviews suggested that the initial identified population should be rich in symptoms burden to start building a collaboration with hematologists.

Consequently, in a second time, end-of-life patients could be co-managed between the two staffs, with a simultaneous approach. Moreover, being part of the hematologic team or being perceived like an insider seem to be the winning element in the RCTs realized until now.

Finally, trials with inpatients -as transplanted patients, for example - could be easier to conduct, due to the high symptoms burden and the access facility to the ward.

On the other hand, failure experience collected from the interviewed experts are described as linked to the population target definition as “incurable”, a criterion hard to recognize for hematologists.

Moreover, the hematologist point of view on Palliative Care is essential for both refer to PC and propose a PC trial.

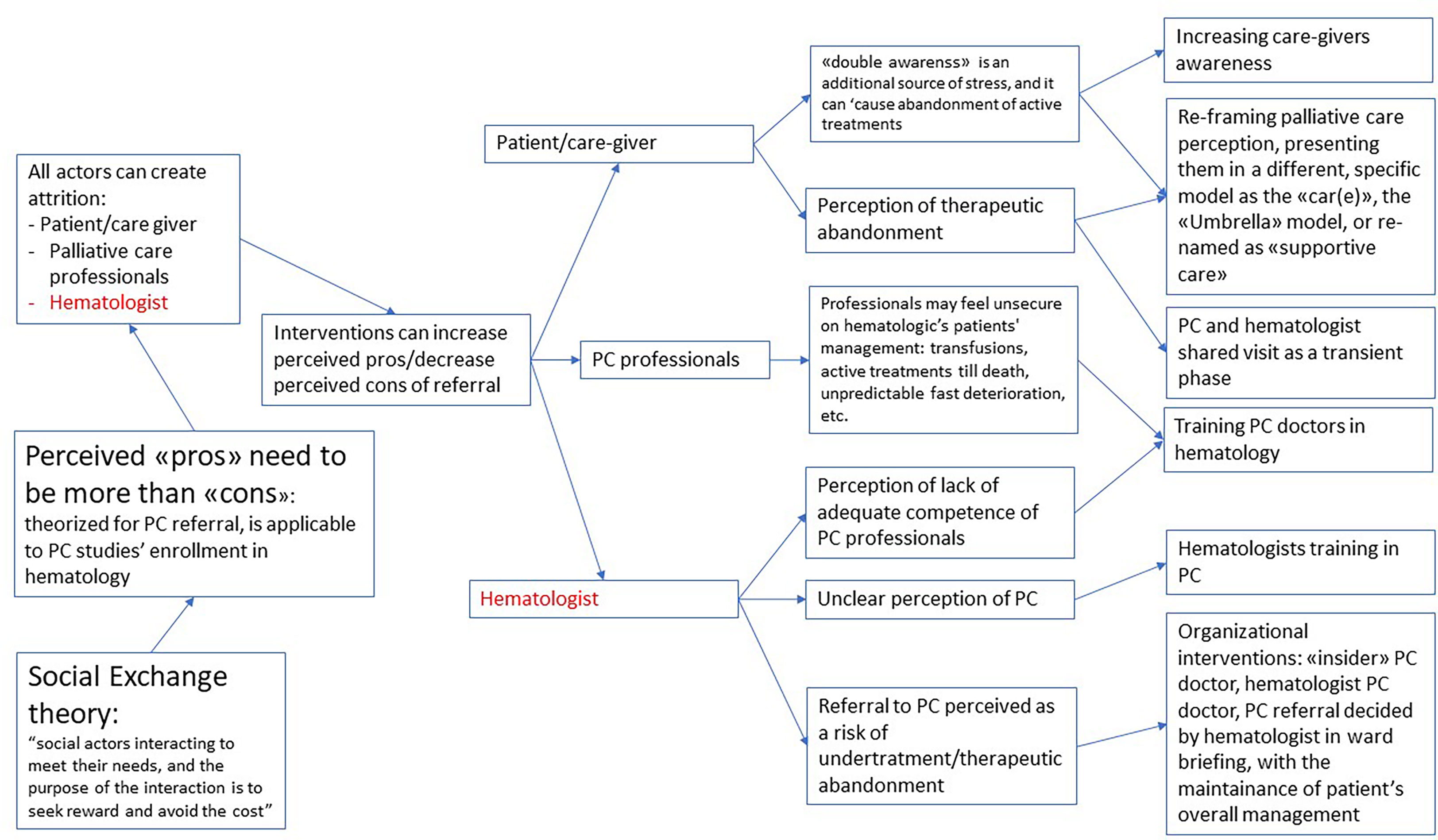

An important finding of this review was that ‘success features’ did not seem to be intrinsic to any specific single study design or type of research, but the result of many different interactions between different contexts and mechanisms. “Social exchange theory” by Homans was used by Salins to explain the possible problems in referral in palliative care (47), including hematology. We selected this theory as flexible and useful enough to be used to explain the problems in enrollment in PC studies in hematologic patients too. According to this interpretation, referral is a social interaction, and depends on the perception of social actors of this interaction as capable of providing a sort of reward and avoid a cost. As represented in Figure 2, it’s plausible that every actor involved can create attrition in the enrollment process. But as stated both in the reviewed literature and in the experts ‘opinions, it’s possible to design a study or a clinical environment to create a perception of a more favorable reward/costs relation for all the actors involved: this might be seen as the “intermediate mechanism”, on which different kind of interventions might have an impact.

Figure 2 Refined theory: what works, for whom and in which circumstaces, when enrolling hematologic cancer patients in palliative care?

It’s possible to intervene on the perception of patients and caregivers, where the “double awareness” (26) of potentially fatal development of the disease and at the same time potentially life-prolonging intervention creates a high stress. For instance, reframing their perception of palliative care through the use of a different term (as “supportive care”) (27) or the explanation of a different framework for palliative care for patients with hematologic malignancies as the “CAR(E)” or “Umbrella” model (43), or even with an explicit decision to create a higher involvement of the care giver in partial substitution of the patient.

It’s also possible to increase the self-efficacy of palliative care doctors, through specific hematologic training, considering the specific differences of this patients’ population.

But it’s highly likely that the more relevant actor in the process might be the hematologist. Many possible interventions might lead to a better perception of the advantages of PC referral.

An unclear perception of referral as a possible source of undertreatment might be addressed with organizational adjustments, as having a PC hematologist, or a palliative care consultation that is discussed in the ward meeting and keeps the patient under the hematologic management.

As a consequence, (see Figure 3) the perception of the different actors might be the key element to lead to an intervention modulated on the characteristics of the specific environment in which the study might be developed, in particular the perception of hematologists. A stronger, already existing relationship between the two teams might imply the chance of working on highly complex needs. On the other end, a new relationship might require an easier task to start, as addressing highly symptomatic patients (ig, patients undergoing transplantation).

This synthesis from literature and experts ‘opinions allows us to deepen the topic of enrolment in PC trial in hematologic cancer patients.

As highlighted by our results, the problem of enrolling hematological patients in palliative care trials overlaps with dynamics inherent in the referral to PC services by hematologists, in general.

We defined our general refined theory as a “ecological theory of enrollment in palliative care research on patients with hematologic malignancies”.

As a refinement to our initial list of CMOs impacting the enrollment process, we selected the “social exchange theory” (SET) of Salins (47) as a relevant model for our theoretical construction. In his SET, he theorizes that oncologists need to have a clear perception of the advantages that they might get from the referral to palliative care, and that these advantages need to outbalance the costs.

This model is useful to explain the difficulty of enrollment in palliative care intervention in hematologic patients too and could be integrated with other theoretical aspects specific for this field. We face in hematologic patients the specific difficulty of “double awareness” (as theorized by Gerlach (26)) that puts the patients and the caregivers on a specific tension due to the double possibility of having a rapid deterioration of health conditions to death or getting to a disease-free period of time thanks to the medicines. Applying the SET model to hematology intervention, we might see how this aspect of “double awareness” needs to be managed both by health professionals and patients and caregivers. Health professionals will then be assessing their pros and cons of referral, knowing that the costs of the referral might result in less awareness of curing possibilities and less focus on available treatments.

Another relevant CMO that we added to our initial theory, is that palliative care needs the PC professionals to be really flexible, to increase referral to PC of patients with hematologic malignancies, searching for the most suitable model for their environment. While we listed several aspects that could have an impact and need to be addressed while designing the intervention, if we start from the SET theory, it seems safe to theorize that every intervention should start from the assessment of the perception of the hematologists of the possible advantages and disadvantages of the referral to palliative care. A first distinction should be between interventions that are built on a strong relationship between PC staff and hematologists, and interventions that are developed independently from an already relationship between the teams. Often, these interventions might implicitly be designed to build a better relationship by the leaders of the program.

Quantitative elements could be informative on the level of integration; while qualitative data could help selecting the elements that could be addressed by an intervention aimed at reaching a more cooperative environment.

The successful experiences reported of enrollment of hematologic patients in palliative care were all based on a previous positive experience of cooperation between the two teams (7, 18). It might be unlikely that the enrollment process could be successful in a context where the intervention itself aims at obtaining a better interaction between the two teams.

Some interventions are possible and seem more likely to work, and all of them might be interpreted as an effort to increase the pros/cons ratio and the perception of the palliative care contribution in the hematologists.

Mere technical improvements (such as a remembering email or a phone call from the researcher) as well as simply hypothesizing a different study design (42) seem to not be able to solve the question and might lead to miss the more relevant points.

The contamination of knowledge with a Palliative care/hematology model that is not only integrated but embedded (44) would respond both to organizational problems and to those related to misconceptions on PC; both expert interviews and data from literature confirm this suggestion.

The health care professionals gate keeping-where the professionals don’t recognize PC needs- was recognized as a barrier to PC enrolment by the literature (42) and seems to be logically applicable in the hematologic setting too. An integrative model “fluctuant, flexible and based on patients’ needs”, where these needs are detected by hematologists has been suggested as a possible model of optimal integration (3). But it might be beneficial to consider the possibility of an even more embedded model, where PC is almost “forced” in hematology ward’s daily work. It could minimize the burden of the intervention both for patients and clinical staff and overcome the difficulties by hematologist to recognize PC needs especially in asymptomatic patients. Moreover, having a PC physician/nurse as a member of the hematologic team could lead to perceive palliative care as a routine component of the patient care.

According to this, an additional mechanism that might be beneficial in terms of integration is the training of hematological professionals in palliative care and in understanding deeply the palliative care approach, while training palliative care practitioners as well to the specificities of the hematological patient, as suggested by many authors (26, 28–30, 45).

Our experts’ interviews also suggested that enrolling only symptomatic patients could be a more initial intervention; however, an early approach also for asymptomatic patients could change the culture/improve the acceptance between palliative care professionals and hematologist. The referral not only for physical needs but also social, psychological, ethical and spiritual ones, should be learnt and improved (26, 46).

Unpredictable course of hematologic malignancies could negatively impact the enrollment.

Using objective and systematic criteria for enrollment (as conducing a first assessment on the list of transplants, or having an automatic flagging and reporting of patients with bad prognosis criteria) would avoid this lack. Artificial intelligence has had a growing improvement for this kind of problems (54).

The overall quality of a review is strongly influenced by the quality of the primary studies considered. The difficulty in gathering firsthand data on palliative care patients is the very reason why this approach might be interesting, as we tried to produce a theoretical contribution based on what is known, what is guessable and what is not known to help navigate this difficult field.

A realist review is an evidence-informed review, who is only partially evidence based, as part of the effort in this specific type of review is trying to produce a theoretical contribution from the available data. We attempted to suggest possible solutions and useful links between what is perceived as connected in this field, trying to start from making explicit what is “obvious” for the researchers in the field but not so obvious for the readers.

This approach limits the exact generalizability of our suggestions, but encourages researchers to try and confirm or challenge our hypothesis, as expected by realist methodologies.

The referral to PC- as the enrollment in a PC trial - should be tailored on patients’ needs and recognizing these palliative care needs is not simple for Hematologists.

To recognize the relationship between PC staff and Hematology is mandatory to propose the right approach, an integration flexible model or on an embedded model.

Consequently, we suggest that expected outcomes should be different, based on a preliminary evaluation of the context of the intervention: while an intervention based on a new relationship might have as a starting stage the aim to address complex symptoms control, and might also explicitly be part of a wider intervention that might result in building stronger relationships between the different stakeholders. On the other side, when a strong, previous relationship between the staffs is already present, it might increase the chance to address more complex topics as advance care planning.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Both authors contributed to all parts of the manuscripts. In particular, ST worked more on background and discussion and GM worked more on “methods” and results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health – Ricerca Corrente Annual Program 2024.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.991791/full#supplementary-material

1. Bandieri E, Apolone G, Luppi M. Early palliative and supportive care in hematology wards. Leuk Res (2013) 37(7):725–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.03.007

2. Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB, Fletcher SA, Earle CC, Tulsky JA, et al. Barriers to quality end-of-Life care for patients with blood cancers. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2016) 34(26):3126–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8177

3. Roeland E, Ku G. Spanning the canyon between stem cell transplantation and palliative care. Hematology (2015) 2015(1):484–9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.484

4. Zimmermann C, Mathews J. Palliative care is the umbrella, not the rain–a metaphor to guide conversations in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol (2022) 8(5):681. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.8210

5. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: the world health organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage (2002) 24(2):91–6. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00440-2

6. White C, Hardy J. What do palliative care patients and their relatives think about research in palliative care?–a systematic review. Support Care Cancer (2010) 18(8):905–11. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0724-1

7. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2015) 33(13):1438–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362

8. Schenker Y, Bahary N, Claxton R, Childers J, Chu E, Kavalieratos D, et al. A pilot trial of early specialty palliative care for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: Challenges encountered and lessons learned. J Palliat Med (2018) 21(1):28–36. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0113

9. Bloomer MJ, Hutchinson AM, Brooks L, Botti M. Dying persons’ perspectives on, or experiences of, participating in research: An integrative review. Palliat Med (2018) 32(4):851–60. doi: 10.1177/0269216317744503

10. Firn J, Preston N, Walshe C. What are the views of hospital-based generalist palliative care professionals on what facilitates or hinders collaboration with in-patient specialist palliative care teams? a systematically constructed narrative synthesis. Palliat Med (2016) 30(3):240–56. doi: 10.1177/0269216315615483

11. Tanzi S, Venturelli F, Luminari S, Merlo FD, Braglia L, Bassi C, et al. Early palliative care in haematological patients: a systematic literature review. BMJ Support Palliat Care (2020) 10(4):395–403. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002386

12. El-Jawahri A, Nelson AM, Gray TF, Lee SJ, LeBlanc TW. Palliative and end-of-Life care for patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38(9):944–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02386

13. Tanzi S, Luminari S, Cavuto S, Turola E, Ghirotto L, Costantini M. Early palliative care versus standard care in haematologic cancer patients at their last active treatment: study protocol of a feasibility trial. BMC Palliat Care (2020) 19(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00561-w

14. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ (2012) 46(1):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04045.x

15. Pawson R. Realistic evaluation. SAGE Publications Ltd New York (2018). Available at: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/realistic-evaluation/book205276.

16. Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, Greenhalgh J, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med (2016) 14(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1

17. Welcome to ramesesproject.org . Available at: https://www.ramesesproject.org/.

18. El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, Traeger L, Greer JA, Pirl WF, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA (2016) 316(20):2094–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16786

19. Cheung MC, Croxford R, Earle CC, Singh S. Days spent at home in the last 6 months of life: a quality indicator of end of life care in patients with hematologic malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma (2020) 61(1):146–55. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1654095

20. Rodin G, Malfitano C, Rydall A, Schimmer A, Marmar CM, Mah K, et al. Emotion and symptom-focused engagement (EASE): a randomized phase II trial of an integrated psychological and palliative care intervention for patients with acute leukemia. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer (2020) 28(1):163–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04723-2

21. Loggers ET, LeBlanc TW, El-Jawahri A, Fihn J, Bumpus M, David J, et al. Pretransplantation supportive and palliative care consultation for high-risk hematopoietic cell transplantation patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transpl (2016) 22(7):1299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.03.006

22. Porta-Sales J, Guerrero-Torrelles M, Moreno-Alonso D, Sarrà-Escarré J, Clapés-Puig V, Trelis-Navarro J, et al. Is early palliative care feasible in patients with multiple myeloma? J Pain Symptom Manage (2017) 54(5):692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.012

23. Selvaggi KJ, Vick JB, Jessell SA, Lister J, Abrahm JL, Bernacki R. Bridging the gap: a palliative care consultation service in a hematological malignancy-bone marrow transplant unit. J Community Support Oncol (2014) 12(2):50–5. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0015

24. Cartoni C, Brunetti GA, D’Elia GM, Breccia M, Niscola P, Marini MG, et al. Cost analysis of a domiciliary program of supportive and palliative care for patients with hematologic malignancies. Haematologica (2007) 92(5):666–73. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10324

25. Hung YS, Wu JH, Chang H, Wang PN, Kao CY, Wang HM, et al. Characteristics of patients with hematologic malignancies who received palliative care consultation services in a medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Care (2013) 30(8):773–80. doi: 10.1177/1049909112471423

26. Gerlach C, Alt-Epping B, Oechsle K. Specific challenges in end-of-life care for patients with hematological malignancies. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care (2019) 13(4):369–79. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000470

27. Booker R, Dunn S, Earp MA, Sinnarajah A, Biondo PD, Simon JE. Perspectives of hematology oncology clinicians about integrating palliative care in oncology. Curr Oncol (2020) 27(6):313–20. doi: 10.3747/co.27.6305

28. Dowling M, Fahy P, Houghton C, Smalle M. A qualitative evidence synthesis of healthcare professionals’ experiences and views of palliative care for patients with a haematological malignancy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) (2020) 29(6):1-25. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13316

29. Oechsle K. Palliative care in patients with hematological malignancies. Oncol Res Treat (2019) 42(1–2):25–30. doi: 10.1159/000495424

30. McCaughan D, Roman E, Smith AG, Garry AC, Johnson MJ, Patmore RD, et al. Palliative care specialists’ perceptions concerning referral of haematology patients to their services: findings from a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care (2018) 17(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0289-1

31. Bennardi M, Diviani N, Gamondi C, Stüssi G, Saletti P, Cinesi I, et al. Palliative care utilization in oncology and hemato-oncology: a systematic review of cognitive barriers and facilitators from the perspective of healthcare professionals, adult patients, and their families. BMC Palliat Care (2020) 19(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00556-7

32. Barbaret C, Berthiller J, Schott Pethelaz AM, Michallet M, Salles G, Sanchez S, et al. Research protocol on early palliative care in patients with acute leukaemia after one relapse. BMJ Support Palliat Care (2017) 7(4):480–4. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001173

33. Morikawa M, Shirai Y, Ochiai R, Miyagawa K. Barriers to the collaboration between hematologists and palliative care teams on relapse or refractory leukemia and malignant lymphoma patients’ care: A qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med (2016) 33(10):977–84. doi: 10.1177/1049909115611081

34. Scarfò L, Karamanidou C, Doubek M, Garani-Papadatos T, Didi J, Pontikoglou C, et al. MyPal ADULT study protocol: a randomised clinical trial of the MyPal ePRO-based early palliative care system in adult patients with haematological malignancies. BMJ Open (2021) 11(11):e050256. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050256

35. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Ahles T. Oncologists’ perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a national cancer institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care (2013) 11(5):415–23. doi: 10.1017/S1478951512000673

36. Maloney C, Lyons KD, Li Z, Hegel M, Ahles TA, Bakitas M. Patient perspectives on participation in the ENABLE II randomized controlled trial of a concurrent oncology palliative care intervention: Benefits and burdens. Palliat Med (2013) 27(4):375–83. doi: 10.1177/0269216312445188

37. Resick JM, Sefcik C, Arnold RM, LeBlanc TW, Bakitas M, Rosenzweig MQ, et al. Primary palliative care for patients with advanced hematologic malignancies: A pilot trial of the SHARE intervention. J Palliat Med (2021) 24(6):820–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0407

38. Jones TA, Olds TS, Currow DC, Williams MT. Feasibility and pilot studies in palliative care research: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage (2017) 54(1):139–151.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.02.015

39. Audrey S. Qualitative research in evidence-based medicine: Improving decision-making and participation in randomized controlled trials of cancer treatments. Palliat Med (2011) 25(8):758–65. doi: 10.1177/0269216311419548

40. Houghton C, Dowling M, Meskell P, Hunter A, Gardner H, Conway A, et al. Factors that impact on recruitment to randomised trials in health care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. In: Cochrane database syst rev. (New Jersey, U.S.: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd Hoboken) (2020)2020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000045.pub2

41. Walsh E, Sheridan A. Factors affecting patient participation in clinical trials in Ireland: A narrative review. Contemp Clin Trials Commun (2016) 3:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2016.01.002

42. Dunleavy L, Walshe C, Oriani A, Preston N. Using the “Social marketing mix framework” to explore recruitment barriers and facilitators in palliative care randomised controlled trials? a narrative synthesis review. Palliat Med (2018) 32(5):990–1009. doi: 10.1177/0269216318757623

43. Button E, Bolton M, Chan RJ, Chambers S, Butler J, Yates P. A palliative care model and conceptual approach suited to clinical malignant haematology. Palliat Med (2019) 33(5):483–5. doi: 10.1177/0269216318824489

44. Ofran Y, Bar-Sela G, Toledano M, Kushnir I, Moalem B, Gil W, et al. Palliative care service incorporated in a hematology department: a working model fostering changes in clinical practice. Leuk Lymphoma (2019) 60(8):2079–81. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1564826

45. Santivasi W, Wu K, Litzow M, LeBlanc T, Strand J. Palliative care physician comfort (and discomfort) with discussing prognosis in hematologic diseases: Results of a nationwide survey (SA528B). J Pain Symptom Manage (2019) 57(2):454. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.12.205

46. Porta-Sales J, Noble S. Haematology and palliative care: the needs are out there. Palliat Med (2019) 33(5):481–2. doi: 10.1177/0269216319840604

47. Salins N, Ghoshal A, Hughes S, Preston N. How views of oncologists and haematologists impacts palliative care referral: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care (2020) 19(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00671-5

48. Santivasi WL, Childs DS, Wu KL, Partain DK, Litzow MR, LeBlanc TW, et al. Perceptions of hematology among palliative care physicians: Results of a nationwide survey. J Pain Symptom Manage (2021) 62(5):949–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.04.021

49. Payne SA, Moore DC, Stamatopoulos K. MyPal: Designing and evaluating digital patient-reported outcome systems for cancer palliative care in Europe. J Palliat Med (2021) 24(7):962–4. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2021.0120

50. Britten N, Jones R, Murphy E, Stacy R. Qualitative research methods in general practice and primary care. Fam Pract (1995) 12(1):104–14. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.1.104

51. Westhorp G, Manzano A. Realist evaluation interviewing – a ‘Starter set’ of questions. (2017) 3. Available at: https://www.ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Realist_interviewing_starter_questions.pdf.

52. Boland J, Currow DC, Wilcock A, Tieman J, Hussain JA, Pitsillides C, et al. A systematic review of strategies used to increase recruitment of people with cancer or organ failure into clinical trials: Implications for palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage (2015) 49(4):762–772.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.09.018

53. Vlckova K, Polakova K, Tuckova A, Houska A, Loucka M. Views of patients with advanced disease and their relatives on participation in palliative care research. BMC Palliat Care (2021) 20(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00779-2

Keywords: realist sinthesys, hematologic palliative care, research in hematologic palliative care, research in palliative care, enrollment in palliative care, oncology, hemato oncology

Citation: Tanzi S and Martucci G (2023) Doing palliative care research on hematologic cancer patients: A realist synthesis of literature and experts’ opinion on what works, for whom and in what circumstances. Front. Oncol. 13:991791. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.991791

Received: 12 July 2022; Accepted: 13 March 2023;

Published: 27 March 2023.

Edited by:

Marco Maltoni, University of Bologna, ItalyReviewed by:

Eleonora Borelli, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Tanzi and Martucci. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gianfranco Martucci, Z2ZtYXJ0dWNjaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.