94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol., 16 March 2023

Sec. Pharmacology of Anti-Cancer Drugs

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1089234

This article is part of the Research TopicMetals in Cancer: from Intracellular Signaling to TherapyView all 5 articles

Xiangling Wang1†

Xiangling Wang1† Ting Wang1†

Ting Wang1† Yunxia Chu1

Yunxia Chu1 Jie Liu2

Jie Liu2 Cuihua Yi1

Cuihua Yi1 Xuejun Yu1

Xuejun Yu1 Yonggang Wang1

Yonggang Wang1 Tianying Zheng1

Tianying Zheng1 Fangli Cao3

Fangli Cao3 Linli Qu3

Linli Qu3 Bo Yu4

Bo Yu4 Huayong Liu5

Huayong Liu5 Fei Ding6

Fei Ding6 Shuang Wang7

Shuang Wang7 Xiangbo Wang8

Xiangbo Wang8 Jing Hao1*

Jing Hao1* Xiuwen Wang1*

Xiuwen Wang1*Background: For patients who have contraindications to or have failed checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy remains the standard second-line option to treat non-oncogene-addicted advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of S-1-based non-platinum combination in advanced NSCLC patients who had failed platinum doublet chemotherapy.

Methods: During January 2015 and May 2020, advanced NSCLC patients who received S-1 plus docetaxel or gemcitabine after the failure of platinum-based chemotherapy were consecutively retrieved from eight cancer centers. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), overall survival (OS), and safety. By using the method of matching-adjusted indirect comparison, the individual PFS and OS of included patients were adjusted by weight matching and then compared with those of the docetaxel arm in a balanced trial population (East Asia S-1 Trial in Lung Cancer).

Results: A total of 87 patients met the inclusion criteria. The ORR was 22.89% (vs. 10% of historical control, p < 0.001) and the DCR was 80.72%. The median PFS and OS were 5.23 months (95% CI: 3.91–6.55 months) and 14.40 months (95% CI: 13.21–15.59 months), respectively. After matching with a balanced population in the docetaxel arm from the East Asia S-1 Trial in Lung Cancer, the weighted median PFS and OS were 7.90 months (vs. 2.89 months) and 19.37 months (vs. 12.52 months), respectively. Time to start of first subsequent therapy (TSFT) from first-line chemotherapy (TSFT > 9 months vs. TSFT ≤ 9 months) was an independent predictive factor of second-line PFS (8.7 months vs. 5.0 months, HR = 0.461, p = 0.049). The median OS in patients who achieved response was 23.5 months (95% CI: 11.8–31.6 months), which was significantly longer than those with stable disease (14.9 months, 95% CI: 12.9–19.4 months, p < 0.001) or progression (4.9 months, 95% CI: 3.2–9.5 months, p < 0.001). The most common adverse events were anemia (60.92%), nausea (55.17%), and leukocytopenia (33.33%).

Conclusions: S-1-based non-platinum combination had promising efficacy and safety in advanced NSCLC patients who had failed platinum doublet chemotherapy, suggesting that it could be a favorable second-line treatment option.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of primary lung cancer. Recent laboratory research highlighted current treatment strategies, such as radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and traditional therapy (1). In the clinic, especially for non-oncogene-addicted advanced NSCLC patients without contraindications to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), chemotherapy in combination with immunotherapy has become the preferred first-line treatment strategy. However, most patients will develop resistance to ICI over time. To date, several combination therapies are under development to delay or manage the acquired resistance to ICIs, including the blockade of immune coinhibitory signals, the activation of those with costimulatory functions, the modulation of the tumor microenvironment, and the targeting T-cell priming (2).

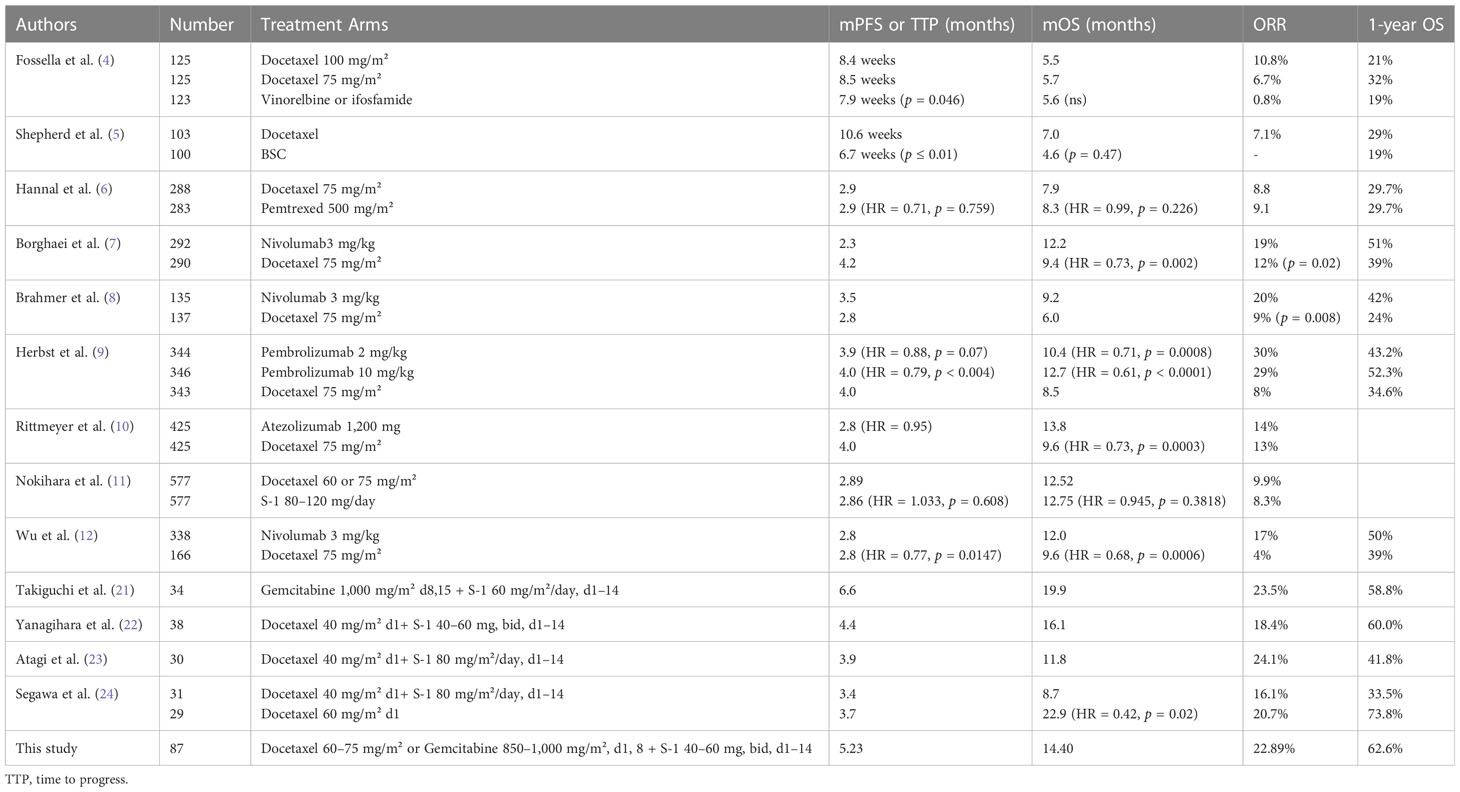

Thus far, conventional systemic chemotherapy alone or with antiangiogenic agents remains the mainstay treatment (3). To date, several options for second-line treatment are available, ranging from chemotherapy alone, in combination with an antiangiogenic agent, and immunotherapy. Docetaxel and pemetrexed are the most commonly used single agents. As a historical control, the response rate (RR) of docetaxel was approximately 10%, and the median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 2 to 4 months and 5.5 to 12.5 months, respectively (4–12). Since 2015, ICIs have become the preferred second-line option over docetaxel because of their significant improvement in OS, durable response, and better tolerability, with an ORR of 14% to 30%, a PFS of 2.3 to 4.0 months, and an OS of 9.2 to 13.8 months (7–10, 12, 13). However, the high cost of ICIs and low coverage of health insurance restrict ICI application in Chinese patients widely.

The roles of doublet chemotherapy in the second-line setting are still controversial. In one early meta-analysis (14), the combination arm showed a statistically significant improvement in ORR (15.1% vs. 7.3%) and PFS (14 weeks vs. 11.7 weeks), but no improvement difference in OS (37.3 weeks vs. 34.7 weeks) compared with single-agent therapy. However, most studies did not distinguish or categorize the patients by factors that might impact the potential benefit from the second-line combination chemotherapy. By contrast, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy was revealed to be the preferred second-line option over single-agent chemotherapy in clinical practice from two Chinese retrospective studies and conferred improved OS especially in patients with longer treatment-free interval (TFI) or time to progression from first-line chemotherapy (15, 16).

In East Asia, S-1 is another promising, well-tolerated, and cost-effective option in advanced NSCLC (17), which is a kind of oral compound anticancer drug composed of tegafur (FT), gimeracil (CDHP), and oteracil potassium (OXO). Furthermore, in comparison with pemetrexed, S-1 improved the synergistic therapeutic efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibodies by eliminating myeloid-derived suppressor cells and downregulating the expression of tumor-derived Bv8 and S100A8 (18). S-1 plus cisplatin or carboplatin demonstrated non-inferior OS as compared to paclitaxel or docetaxel plus platinum as first-line treatment in two randomized phase III trials (19, 20). Furthermore, S-1 was as effective as docetaxel in second-line therapy with less toxicity in the East Asia S-1 Trial in Lung Cancer (11). Several single-arm phase I/II trials evaluated the efficacy and safety of S-1 plus docetaxel or gemcitabine and had shown encouraging RR, OS, and non-overlapping toxicity profile (21–23). Data are still lacking about S-1 plus non-platinum doublet chemotherapy as a second-line option in Chinese advanced NSCLC patients. Therefore, we conducted a multicenter retrospective study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of S-1-based non-platinum combination chemotherapy in previously treated advanced NSCLC.

We retrieved data from the HIS (hospital information system) in the advanced NSCLC patients from January 2015 to May 2020 treated at eight institutions of Shandong Province in China, namely, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Qingdao branch of Qilu Hospital; Shandong University; Shandong Tumor Hospital; the First People’s Hospital of Zibo; Zhangqiu People’s Hospital; Linyi People’s Hospital; Taian Central People’s Hospital; and Huantai People’s Hospital.

Patients eligible for this study were required to meet the following criteria: (1) aged between 18 and 75 years; (2) ECOG performance status of 0 or 1; (3) histologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC with stage IIIB or IV disease (AJCC 7th); (4) progression from first-line platinum-based doublet chemotherapy; (5) negative EGFR/ALK mutation or unknown before initiation of second-line chemotherapy; if EGFR/ALK mutation was positive, chemotherapy was introduced after TKI failure; (6) at least one measurable target lesion; (7) without symptomatic brain metastasis; and (8) received docetaxel plus S-1 or gemcitabine plus S-1 as second-line chemotherapy. The main exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) brain metastasis with symptoms; (2) patients with positive driver genes can be treated with other targeted therapies as a second-line treatment.

Approval for the retrospective review of these patients’ records was approved by the Medical Ethics Association of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (2015040).

The chemotherapy regimen was docetaxel plus S-1 or gemcitabine plus S-1. The doses of drugs were within the following range: S-1: 40–60 mg, po, twice a day for 2 weeks and 1 week off; docetaxel: 60–75 mg/m², day 1 every 3 weeks; gemcitabine: 850–1,000 mg/m², day 1 and day 8 every 3 weeks. At least two cycles were required to evaluate the overall response rate (ORR). S-1 maintenance therapy was allowed for patients who achieved stable disease or response after combination chemotherapy.

The primary endpoint was PFS. The secondary endpoints were ORR, disease control rate (DCR), OS, and safety. Radiological response was assessed every 6 weeks in accordance with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1). TSFT after first-line chemotherapy was calculated from the date of initiation of first-line chemotherapy to the initiation of second-line treatment. PFS was defined as the time period since the date of initiation of second-line therapy to the date of disease progression or death of any cause, whichever occurred first; OS was defined as the time period since the date of initiation of second-line therapy to the date of death of any cause or last follow-up. Adverse events were recorded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0) of the National Cancer Institute. The subsequent treatment information after failure of second-line chemotherapy was attained by telephone interview or medical records. The last day of follow-up was 31 October 2020.

The ORR of this study was compared with the ORR of docetaxel as a historical control by Fisher’s exact test, which was set as 10%, according to a summary of all phase III clinical studies of docetaxel as second-line treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC (Table 1). p < 0.025 in the unilateral test was considered statistically significant. Survival probabilities were calculated and compared in two groups using the Kaplan–Meier method and Log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Table 1 Comparison of S-1-based doublet chemotherapy with docetaxel from phase III randomized controlled clinical trials of second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC.

The PFS and OS of this study were compared with those of docetaxel using matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC). After a systematic literature review, patients across our study and the East Asia S-1 Trial in Lung Cancer were matched on a range of potential effect modifiers, including age, sex, smoking status, TNM stage, histology, postoperative recurrence, ECOG performance status, and EGFR mutation status (11). Data from patients receiving S-1 were re-weighted to match the baseline characteristics of patients included in the East Asia S-1 Trial receiving docetaxel. The individual weights were estimated using a logistic model as described by Signorovitch et al. (25). OS and PFS analyses were conducted using aggregate data. All statistical analyses were carried out by R 3.5.0 and SAS 9.4 software, and a two-sided test was performed (α = 0.05).

A total of 87 patients were eligible for safety analysis; 34 patients (39.08%) received gemcitabine plus S-1, while 53 cases (60.92%) were given docetaxel combined with S-1. The median follow-up time was 14.13 months, and the median treatment course was 4 cycles (range, 1–12). A total of 83 patients were eligible for ORR and OS analysis and 76 patients were eligible for PFS analysis (Figure 1). The clinicopathological characteristics of 83 cases are shown in Table 2. Two-thirds of patients were men and the median age was 60 years. Nearly one-fourth of patients were stage IIIB and one-third were squamous carcinomas. Most patients (78%) had ECOG PS 1. Less than 10% of the patients had asymptomatic brain metastasis. EGFR and ALK mutations were seen in 5 and 3 out of 52 patients, respectively, who had gene mutation detection before enrollment. The time to first subsequent therapy (TFST) of first-line chemotherapy in 83 patients was 4.6 months (2.1–8.7 months) and 17 patients (20.48%) had more than 9 months of mPFS (Table 2). Most patients (84.2%) were treated at the Qilu Hospital of Shandong University.

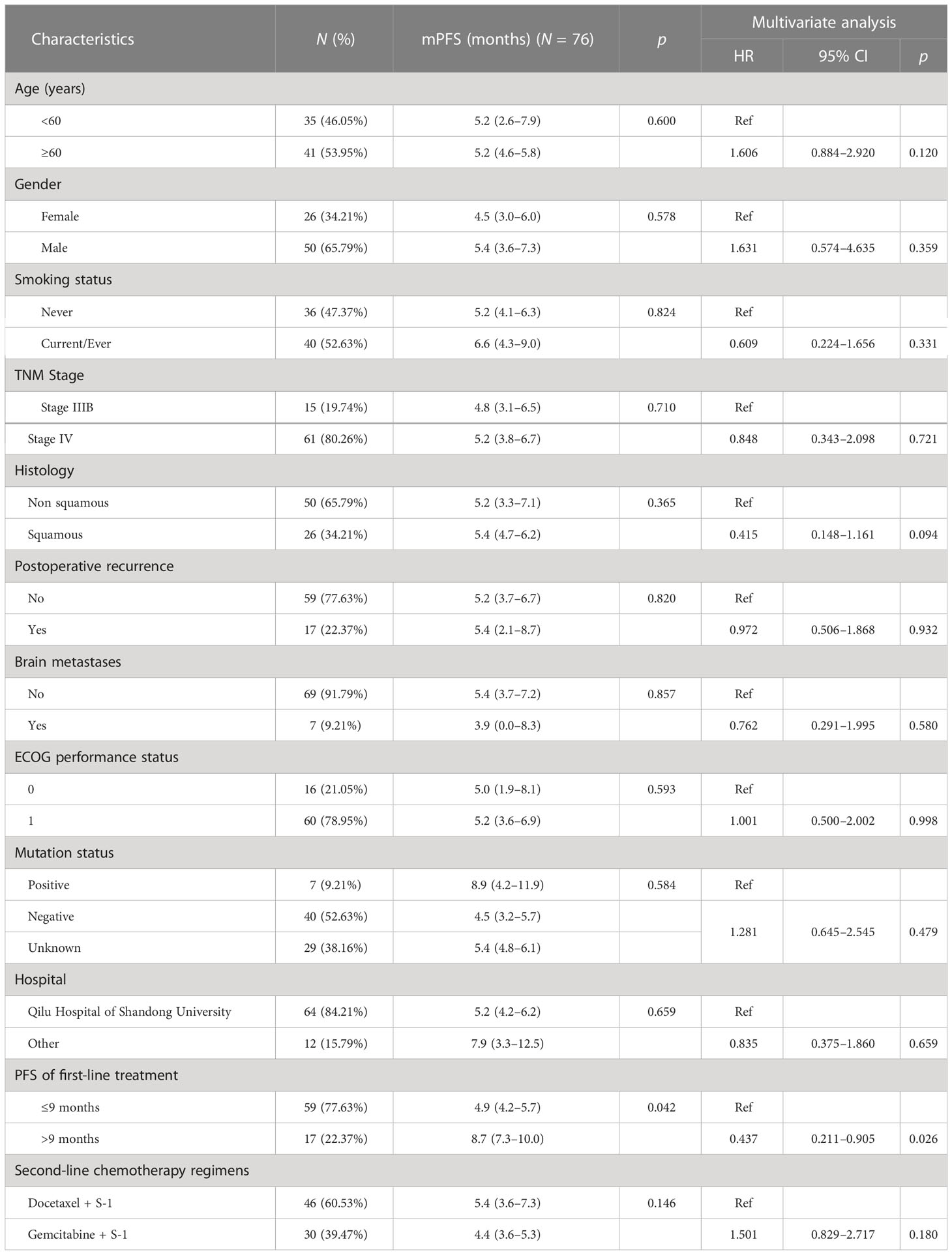

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of PFS in 76 advanced NSCLC patients receiving S-1-based non-platinum doublet chemotherapy as a second-line treatment.

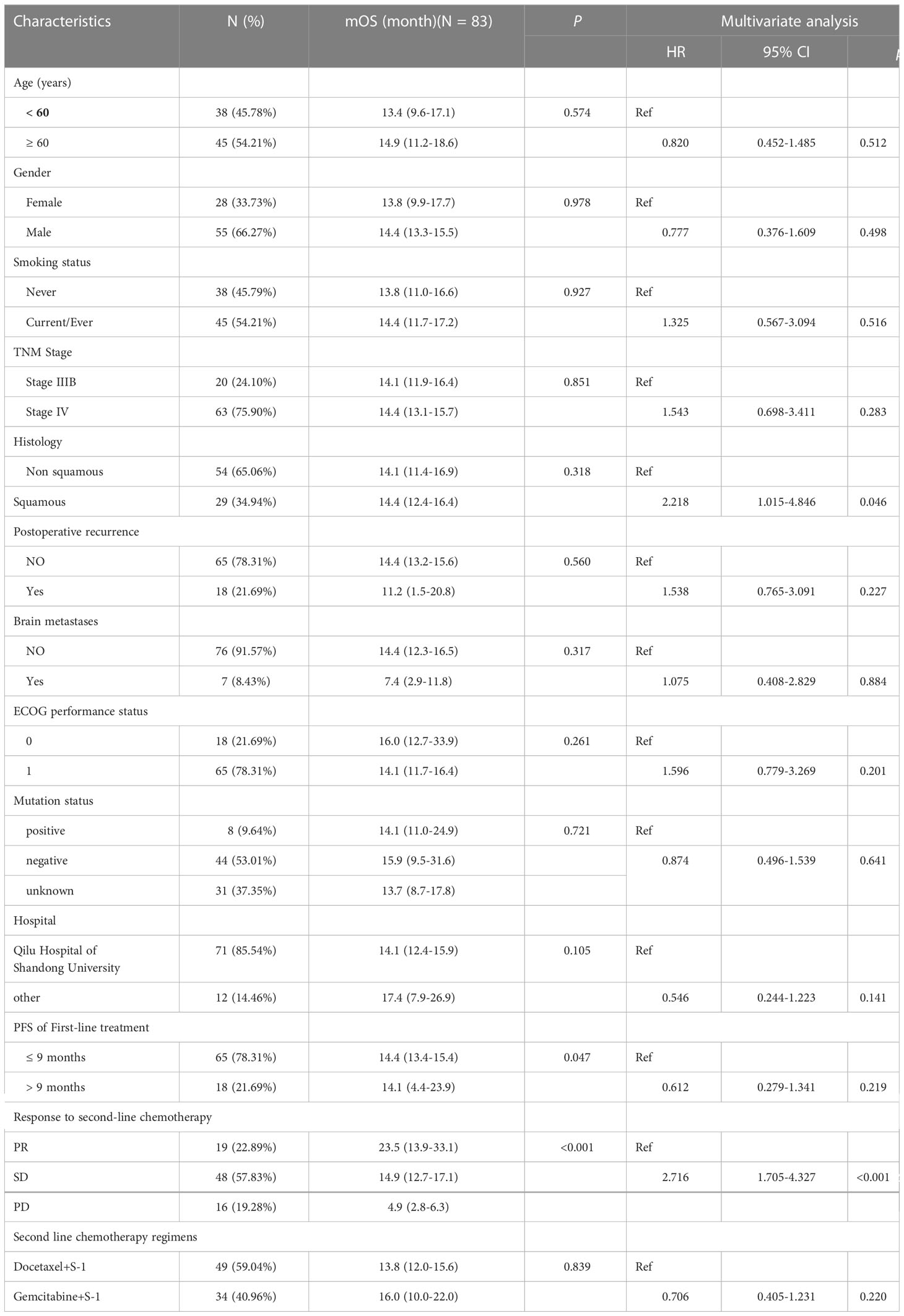

A total of 19 patients (22.89%) were evaluated as partial remission (PR) among 83 patients, much higher than the 10% RR with docetaxel in the historical control (p < 0.001). A total of 48 patients (57.83%) achieved stable disease and 16 patients (19.28%) progressed. The DCR was 80.72%. Of note, the ORR was 52.94% (9/17) in patients with a TFST of > 9 months, whereas in those with a TFST of ≤ 9 months, the ORR was 16.95% (10/59), p = 0.007.

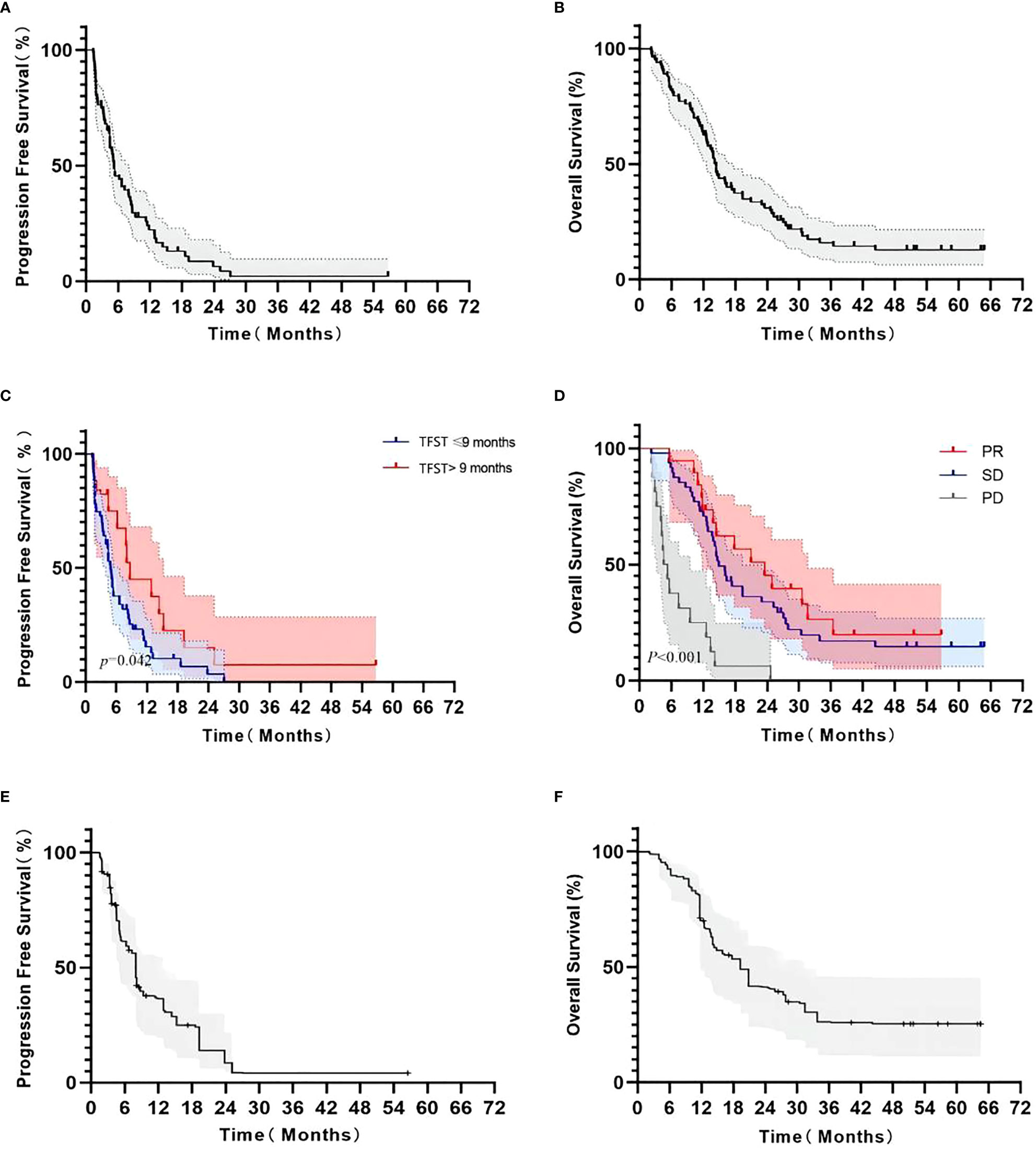

Of 76 patients, 74 (97.4%) had disease progression. Median PFS was 5.23 months (95% CI: 3.91–6.55 months). Six-month PFS rate was 45.5% (95% CI: 33.6%–56.7%) and 1-year PFS rate was 22.2% (95% CI: 12.8%–33.2%), as shown in Figure 2. Multivariate Cox analysis showed that a TFST of > 9 months of first-line chemotherapy was an independent favorable predictive factor of second-line PFS (8.7 months vs. 4.9 months, HR = 0.437, p = 0.026) (Table 2).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier survival curve in advanced NSCLC patients receiving second-line S-1-based doublet chemotherapy. Progression-free survival (A); overall survival (B); PFS according to the TFST from first-line chemotherapy (>9 months and ≤9 months, (C); OS according to response from second-line chemotherapy (PR, SD, and PD, (D); adjusted PFS by weight matching (E); adjusted OS by weight matching (F).

By the end of follow-up, 69 patients (83.1%) died from cancer. The median OS was 14.40 months (95% CI: 13.21–15.59 months). Six-month OS rate was 81.9% (95% CI: 71.8%–88.7%) and 1-year OS rate was 62.6% (95% CI: 51.3%–72.0%), as shown in Figure 2. The median OS in patients who achieved response was 23.5 months (95% CI: 11.8–31.6 months, p < 0.001), which was significantly longer than those with stable disease (14.9 months, 95% CI: 12.9–19.4 months) or progression (4.9 months, 95% CI: 3.2–9.5 months) (Table 3).

Table 3 Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of OS in 83 advanced NSCLC receiving S-1 based doublet as second line treatment.

When adjusted by weight matching with a weighted balanced population from the East Asia S-1 Trial in Lung Cancer (11), 37.9 and 39.4 of the patients were used for comparison for PFS and OS, respectively (Table 4). The weighted mPFS and mOS was 7.90 months (Figure 2A) and 19.37 months (Figures 2E, F), respectively, with S-1 combined with non-platinum-based regimen. A 95% CI of mPFS and mOS was not available owing to the small number of enrolled patients after weighting.

At the date of last follow-up, two patients were still free from progression. Fourteen patients only received best supportive care after failure of chemotherapy. A total of 65 patients (82.28%) received subsequent systemic treatment (Table 5), in which chemotherapy alone accounted for 31.64% of the cases and antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor accounted for 27.85%. Five patients each received later-line anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and further targeted therapy.

As shown in Table 6, a total of 87 patients were evaluated for safety; adverse events of any grade in our study were 88.51%. Grade 3–4 adverse events occurred in 11 of 53 patients (20.75%) in the S-1 plus docetaxel subgroup and in 7 of 34 patients (20.59%) in the S-1 plus gemcitabine subgroup. Ten patients (11.49%) experienced dose reduction and four patients (4.60%) interrupted the treatment.

There was no treatment-related death. The most common adverse events were anemia (60.92%), nausea (55.17%), and leukocytopenia (33.33%), whether in the docetaxel or the gemcitabine plus S-1 subgroup. The most common grade 3/4 adverse event was neutropenia (14.94%).

To our knowledge, this study was the first to explore the efficacy and safety of S-1-based non-platinum combination chemotherapy as a second-line treatment in non-oncogene-addicted advanced Chinese NSCLC patients. There were two major findings.

The first finding was that S-1-based non-platinum combination chemotherapy could be a promising second-line option. When compared with docetaxel as a historical control, as shown in Table 1, this multicenter study provided encouraging benefit in response (22.89%), PFS (5.23 months), OS (14.40 months), and good tolerability. After adjustment by weight matching, there was still a dramatic improvement in PFS (7.90 months) and OS (19.37 months). The results of our study were consistent with most of the other Japanese cohort studies (21–23). The excellent ORR and PFS might be attributed to the combination of S-1 and docetaxel or gemcitabine and also S-1 maintenance. Furthermore, the median OS in patients who achieved response was significantly longer than those with stable disease or progression, which suggested the durable survival benefit from S-1-based doublet non-platinum chemotherapy once achieving response.

One exception was OLCSG trial 0503 (24), in which the single-agent docetaxel had a similar ORR and PFS, but an extraordinarily prolonged survival compared with docetaxel plus S-1 (22.9 months vs. 8.7 months). The much higher percentages of patients receiving poststudy EGFR TKI in the single docetaxel arm (42.9% vs. 16.7%) might contribute to this discrepancy. Poststudy treatment was very prevalent (81.82%) in our study, and nearly 30% of the patients received antiangiogenic treatment with bevacizumab, apatinib, or anlotinib. All of the above post-study drugs were considered to prolong the OS. In a recently published study (26), anlotinib plus S-1 as third- or later-line treatment showed very promising antitumor activity, with an ORR of 37.9%, a PFS of 5.8 months, and an OS of 16.7 months, supporting the use of S-1 and anlotinib either concomitantly or subsequently in the future. Also, in another prospective study (27), bevacizumab and S-1 combination chemotherapy showed high activity with an ORR of 28.3%, a PFS of 4.3 months, and an OS of 15.0 months, and tolerable toxicities.

The second finding was that TFST could predict the PFS benefit from S-1 doublet chemotherapy. The patients with a TFST of > 9 months had a much longer PFS (8.7 months) than those with a TFST of ≤ 9 months (5.0 months). In other words, TFST from first-line chemotherapy could distinguish the patients who might benefit the most from second-line therapy, which was confirmed in two previous Chinese retrospective studies (15, 16). Both a TFST of > 12 months and a TFI of > 6 months from first-line chemotherapy were independent predictive factors of favorable PFS and OS in advanced NSCLC patients who received platinum-based doublet chemotherapy in the second-line setting. With additional new drugs introduced into the first-line treatment in advanced NSCLC, especially CPIs (checkpoint inhibitors) and antiangiogenic agents, whether TFST from these new first-line combinations could predict the benefit of the subsequent treatment remains to be elucidated in the future.

Regarding safety, both hematological and non-hematological toxicity in our study were tolerable and could be well controlled through treatment interruption and/or symptomatic treatment and dose reduction. There were no treatment-related deaths. Common adverse events of S-1 with docetaxel or gemcitabine were anemia, nausea, and leukocytopenia. The most common grade 3/4 adverse event was neutropenia (14.94%). All the above toxicities were higher than those of docetaxel as a historical control (3–10), but consistent with the data of previous S-1 studies (11, 21–23).

New evidence showing that immunotherapy plus chemotherapy could substantially improve ORR, PFS, and OS when compared with immunotherapy (4) or chemotherapy (28, 29) alone has emerged. S-1 had been proven to have a synergistic effect with nivolumab in gastric cancer (30); thus, it can be expected that S-1 would be introduced to clinical trials of immunotherapy in advanced NSCLC in the future.

The present study had some limitations. First, our study is limited by its retrospective nature and patients’ heterogeneity. Selection bias could not be ignored, since patients who could not afford the cost of ICIs or refused the gene mutation analysis had more chances of receiving cytotoxic drugs as a second-line treatment. Second, during the study period, no patient received ICIs in the first-line setting; whether the efficacy of S-1-based doublet chemotherapy as second-line option could be generalized to those who failed immunotherapy needs to be explored. Actually, there may be no need to worry about it since subsequent S-1 or docetaxel after nivolumab was proved to be more effective than regimens without ICI pretreatment (31). Moreover, the high percentage of unknown driver mutation in our study precluded patients’ availability to targeted therapy. Indeed, in the NJLCG0804 trial (32), among NSCLC patients whose treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy failed, S-1 and irinotecan combination therapy demonstrated high effectiveness; the ORR reached 52.0%, and PFS and OS were 5.0 and 17.1 months, respectively. Third, although we did not find a significant difference in survival benefit among patients from different centers, it should be noted that most patients in this study were from the sponsor’s cancer center, while platinum-based doublet chemotherapy as second-line option seemed to be more popular in other institutions from the same province (15).

In conclusion, S-1-based non-platinum combination had promising efficacy and manageable toxicity in advanced NSCLC patients who had failed platinum doublet chemotherapy, indicating a favorable second-line option.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Association of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (2015040). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Conception and design: JH and XWW; Administrative support: XWW; Provision of study materials or patients: TW, XLW, YC, JL, CY, XY, YW, TZ, FC, LQ, BY, HL, FD, SW, XBW, JH, and XWW; Collection and assembly of data: XLW, TW, and JH; Data analysis and interpretation: XLW, TW, and JH; Manuscript writing: All authors; All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Pathiranage VC, Thabrew I, Samarakoon SR, Tennekoon KH, Rajagopalan U, Ediriweera MK. Evaluation of anticancer effects of a pharmaceutically viable extract of a traditional polyherbal mixture against non-small-cell lung cancer cells. J Integr Med (2020) 18:242–52. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2020.02.007

2. Passaro A, Brahmer J, Antonia S, Mok T, Peters S. Managing resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer: Treatment and novel strategies. J Clin Oncol (2022) 40:598–610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01845

3. Santos ES. Treatment options after first-line immunotherapy in metastatic NSCLC. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther (2020) 20:221–8. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2020.1738930

4. Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, Crawford J, Natale RR, Dunphy F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 non-small cell lung cancer study group. J Clin Oncol (2000) 18:2354–62. doi: 10.1200/jco.2000.18.12.2354

5. Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol (2000) 18:2095–103. doi: 10.1200/jco.2000.18.10.2095

6. Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol (2004) 22:1589–97. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.08.163

7. Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-Small-Cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med (2015) 373:1627–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643

8. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-Small-Cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med (2015) 373:123–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627

9. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London England) (2016) 387:1540–50. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01281-7

10. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London England) (2017) 389:255–65. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32517-x

11. Nokihara H, Lu S, Mok TSK, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto N, Shi YK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of s-1 versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (East Asia s-1 trial in lung cancer). Ann oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol (2017) 28:2698–706. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx419

12. Wu YL, Lu S, Cheng Y, Zhou C, Wang J, Mok T, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in a predominantly Chinese patient population with previously treated advanced NSCLC: CheckMate 078 randomized phase III clinical trial. J Thorac Oncol (2019) 14:867–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.006

13. Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London England) (2016) 387:1837–46. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00587-0

14. Di Maio M, Chiodini P, Georgoulias V, Hatzidaki D, Takeda K, Wachters FM, et al. Meta-analysis of single-agent chemotherapy compared with combination chemotherapy as second-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27:1836–43. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.17.5844

15. Yi Y, Liu Z, Fang L, Li J, Liu W, Wang F, et al. Comparison between single-agent and combination chemotherapy as second-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A multi-institutional retrospective analysis. Cancer chemother Pharmacol (2020) 86:65–74. doi: 10.1007/s00280-020-04091-3

16. Mo H, Hao X, Liu Y, Wang L, Hu X, Xu J, et al. A prognostic model for platinum-doublet as second-line chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Med (2016) 5:1116–24. doi: 10.1002/cam4.689

17. Kawahara M, Furuse K, Segawa Y, Yoshimori K, Matsui K, Kudoh S, et al. Phase II study of s-1, a novel oral fluorouracil, in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer (2001) 85:939–43. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2031

18. Nguyen NT, Mitsuhashi A, Ogino H, Kozai H, Yoneda H, Afroj T, et al. S-1 eliminates MDSCs and enhances the efficacy of PD-1 blockade via regulation of tumor-derived Bv8 and S100A8 in thoracic tumor. Cancer Sci (2022) 114(2):384–98. doi: 10.1111/cas.15620

19. Yoshioka H, Okamoto I, Morita S, Ando M, Takeda K, Seto T, et al. Efficacy and safety analysis according to histology for s-1 in combination with carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Updated results of the West Japan oncology group LETS study. Ann Oncol (2013) 24:1326–31. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds629

20. Kubota K, Sakai H, Katakami N, Nishio M, Inoue A, Okamoto H, et al. A randomized phase III trial of oral s-1 plus cisplatin versus docetaxel plus cisplatin in Japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: TCOG0701 CATS trial. Ann Oncol (2015) 26:1401–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv190

21. Takiguchi Y, Seto T, Ichinose Y, Nogami N, Shinkai T, Okamoto H, et al. Long-term administration of second-line chemotherapy with s-1 and gemcitabine for platinum-resistant non-small cell lung cancer: A phase II study. J Thorac Oncol (2011) 6:156–60. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f7c76a

22. Yanagihara K, Yoshimura K, Niimi M, Yasuda H, Sasaki T, Nishimura T, et al. Phase II study of s-1 and docetaxel for previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer chemother Pharmacol (2010) 66:913–8. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1239-7

23. Atagi S, Kawahara M, Kusunoki Y, Takada M, Kawaguchi T, Okishio K, et al. Phase I/II study of docetaxel and s-1 in patients with previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2008) 3:1012–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318183f8ed

24. Segawa Y, Kiura K, Hotta K, Takigawa N, Tabata M, Matsuo K, et al. A randomized phase II study of a combination of docetaxel and s-1 versus docetaxel monotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy: Results of Okayama lung cancer study group (OLCSG) trial 0503. J Thorac Oncol (2010) 5:1430–4. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e3248e

25. Signorovitch JE, Wu EQ, Yu AP, Gerrits CM, Kantor E, Bao Y, et al. Comparative effectiveness without head-to-head trials: A method for matching-adjusted indirect comparisons applied to psoriasis treatment with adalimumab or etanercept. Pharmacoeconomics (2010) 28:935–45. doi: 10.2165/11538370-000000000-00000

26. Xiang M, Yang X, Ren S, Du H, Geng L, Yuan L, et al. Anlotinib combined with s-1 in third- or later-line stage IV non-small cell lung cancer treatment: A phase II clinical trial. oncologist (2021) 26:e2130–5. doi: 10.1002/onco.13950

27. Hasegawa T, Yanagitani N, Ohyanagi F, Kudo K, Horiike A, Tambo Y, et al. Phase II study of the combination of s-1 with bevacizumab for patients with previously treated advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol (2021) 26:507–14. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01822-7

28. Zhang F, Huang D, Zhao L, Li T, Zhang S, Zhang G, et al. Efficacy and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus nab-paclitaxel for patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol (2020) 12:1758835920936882. doi: 10.1177/1758835920936882

29. Arrieta O, Barron F, Ramirez-Tirado LA, Zatarain-Barron ZL, Cardona AF, Diaz-Garcia D, et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The PROLUNG phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6:856–64. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0409

30. Boku N, Ryu MH, Kato K, Chung HC, Minashi K, Lee KW, et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in combination with s-1/capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, advanced, or recurrent gastric/gastroesophageal junction cancer: Interim results of a randomized, phase II trial (ATTRACTION-4). Ann Oncol (2019) 30:250–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy540

31. Tamura N, Horinouchi H, Sekine K, Matsumoto Y, Murakami S, Goto Y, et al. Efficacy of subsequent docetaxel +/- ramucirumab and s-1 after nivolumab for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer (2019) 10:1141–8. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13055

32. Nakamura A, Harada M, Watanabe K, Harada T, Inoue A, Sugawara S. Phase II study of s-1 and irinotecan combination therapy in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer resistant to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: North Japan lung cancer study group trial 0804 (NJLCG0804). Med Oncol (2022) 39(11):163. doi: 10.1007/s12032-022-01755-3

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, second-line treatment, S-1, gemcitabine, docetaxel

Citation: Wang X, Wang T, Chu Y, Liu J, Yi C, Yu X, Wang Y, Zheng T, Cao F, Qu L, Yu B, Liu H, Ding F, Wang S, Wang X, Hao J and Wang X (2023) Could S-1-based non-platinum doublet chemotherapy be a new option as a second-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients? A multicenter retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 13:1089234. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1089234

Received: 04 November 2022; Accepted: 23 February 2023;

Published: 16 March 2023.

Edited by:

Chen Ling, Fudan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaobo Du, Mianyang Central Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Wang, Wang, Chu, Liu, Yi, Yu, Wang, Zheng, Cao, Qu, Yu, Liu, Ding, Wang, Wang, Hao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Hao, aGVkaTAwODRAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=; Xiuwen Wang, eGl1d2Vud2FuZzEyQHNkdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.