94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Oncol., 28 April 2023

Sec. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1040589

This article is part of the Research TopicUniversal Health Coverage and Global Health in OncologyView all 13 articles

Lisa Guccione1,2*

Lisa Guccione1,2* Sonia Fullerton2,3

Sonia Fullerton2,3 Karla Gough1,4

Karla Gough1,4 Amelia Hyatt1,2,5,6

Amelia Hyatt1,2,5,6 Michelle Tew1,5

Michelle Tew1,5 Sanchia Aranda1,6

Sanchia Aranda1,6 Jill Francis1,2,6,7

Jill Francis1,2,6,7Background: Advance care planning (ACP) centres on supporting people to define and discuss their individual goals and preferences for future medical care, and to record and review these as appropriate. Despite recommendations from guidelines, rates of documentation for people with cancer are considerably low.

Aim: To systematically clarify and consolidate the evidence base of ACP in cancer care by exploring how it is defined; identifying benefits, and known barriers and enablers across patient, clinical and healthcare services levels; as well as interventions that improve advance care planning and are their effectiveness.

Methods: A systematic overview of reviews was conducted and was prospectively registered on PROSPERO. PubMed, Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and EMBASE were searched for review related to ACP in cancer. Content analysis and narrative synthesis were used for data analysis. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was used to code barriers and enablers of ACP as well as the implied barriers targeted by each of the interventions.

Results: Eighteen reviews met the inclusion criteria. Definitions were inconsistent across reviews that defined ACP (n=16). Proposed benefits identified in 15/18 reviews were rarely empirically supported. Interventions reported in seven reviews tended to target the patient, even though more barriers were associated with healthcare providers (n=40 versus n=60, respectively).

Conclusion: To improve ACP uptake in oncology settings; the definition should include key categories that clarify the utility and benefits. Interventions need to target healthcare providers and empirically identified barriers to be most effective in improving uptake.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?, identifier CRD42021288825.

A recent international consensus definition for advance care planning (ACP) states that ACP is “the ability to enable individuals to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these goals and preferences with family and health-care providers, and to record and review these preferences if appropriate” (1). Ultimately the goal of ACP is to align the treatment a person receives with their preferences for care (2). Despite practice guidelines recommending ACP for people with cancer, results from the Australia National Advance Care Directive Prevalence study (2017) suggested that only 27% of people with cancer had documented their ACP preferences in an advance care directive (3). This finding is consistent with low rates of ACP discussion and documentation reported internationally (4–6).

In Australia, the terms used in advance care planning differ by state. Nationally, the term ‘substitute decision maker’ is used to denote the person who makes medical decisions if a person loses medical decision-making capacity. ‘Advance care directive’ is the umbrella term for documents expressing the person’s preferences for future health care in the event that they lose medical decision-making capacity. Internationally there is considerable variation in terminology used for ACP. However, the principles of appointing a surrogate decision maker, having conversations about preferences and values, and recording a written advance care directive are generally applicable. In the USA, physician orders such as Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) are included in ACP documentation (1). In Europe, concepts and laws regarding ACP differ, with some countries having legally binding frameworks and others not (1). Some examples from English-speaking countries and Europe are presented in Supplementary File 1 (Advance care planning terms of reference). Often, laws regarding ACP are made at a state or provincial, rather than at a national, level. The lack of consistency in terms and definitions used can be confusing for patients and health providers.

Literature proposes a range of benefits of ACP across various populations. However, it is uncertain from the literature on cancer patients if proposed benefits of ACP have been empirically identified. Studies have found that the values and needs of cancer patients in response to ACP are different to other patient populations (7). For example, patients with cancer placed greater emphasis on decisions on their preferences for site or care rather than intervention-based treatment decisions (7). Also unknown from the literature is whether interventions to support uptake of ACP are targeting the most frequently reported barriers and enablers of ACP, and if so are they effective in improving uptake.

With several published reviews identifying barriers to ACP (8–10) and interventions to support uptake of ACP (11, 12), the aim of this overview of reviews is to clarify and consolidate the evidence base in oncology settings to inform recommendations for improving uptake of ACP. This overview took a systematic approach to searching, appraising, and synthesizing the review literature to address the following research questions (13):

1. How has advance care planning (ACP) been defined and what are the included elements?

2. What are the proposed and empirically supported benefits of ACP in oncology settings?

3. What are the known barriers and enablers of ACP uptake across patient, clinician, healthcare service, and systems levels?

4. Which interventions to improve ACP uptake have been reported, do they target the identified barriers and enablers, and how effective are they?

This systematic overview of reviews used a standardized protocol prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (14). The protocol was registered with Prospero; registration number: CRD42021288825 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021288825).

The search was conducted by one author (LG) using databases PubMed, Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and EMBASE. Papers were restricted to reviews published in English, within a 10-year publication date range from 2011 to August 4, 2021. The search strategy was designed in collaboration with an expert librarian and critically discussed by the research team, capturing terms and synonyms relating to three domains: “advance care plan”, “cancer” and “review”. A full list of search terms is provided in Supplementary File 2.

A review was included in this systematic overview of reviews if it fulfilled all the following inclusion criteria: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) English language; (3) reported only on the populations of interest: adult cancer patients of any gender, healthcare providers responsible for facilitating ACP with adult cancer patients, or family or caregivers of adult cancer patients; and (4) reported on ACP using any definition from the perspectives of patients, healthcare professionals, or staff at hospital service or system levels. We excluded an article if it: (1) reported on a pediatric cancer population; (2) focused on community settings; or (3) did not address at least one of the research questions.

All identified reviews were uploaded to EndNote (15) and imported into Covidence (16) to manage citations and remove duplicates. Following de-duplication, two authors (LG and SF) screened identified articles to determine eligibility for inclusion. Screening occurred in two steps: an initial screen of titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria, and a further step of retrieving the full paper if eligibility could not be confirmed from the abstract. Screening involved judging each review as either: eligible, not eligible, or potentially eligible. Conflicts were resolved initially through discussion (LG and SF) and presented to the research team for final resolution. All differences of opinion were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction templates were designed to enable extraction of all data addressing the research questions and to facilitate consistency of extraction across studies and reviewers. For all reviews that met the inclusion criteria, data extraction was conducted by one author (LG), with 20% of the reviews crosschecked by a second author (SF).

Content analysis (17, 18) and narrative synthesis (19) were used to organise and summarise ACP definitions (research question 1), and the proposed and empirically supported benefits of ACP (research question 2). Proposed benefits were those that formed part of the rationale of an included review, and empirically identified benefits, were those that reported measured outcomes of ACP. These analyses were conducted by one author (LG) and reviewed by a second author (AH or KG).

Reported barriers and enablers of requesting and recording ACP details from a healthcare professional perspective, or deciding and communicating ACP details from a patient perspective were coded into the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (20) (research question 3). This framework was developed to synthesise 33 theories of behaviour, to provide a theory-informed basis for identifying barriers and enablers of behaviour (21, 22). The thematic analysis was conducted by one author (LG) and reviewed by a second author (JF). Identified themes were assessed against previously published ‘importance criteria’ to determine the likely importance and role of each domain in influencing behaviours related to ACP (23). These criteria were: frequency (number of reviews that identified each domain; elaboration (number of content themes identified in each domain); and ‘expressed importance’ (statement from the authors expressing importance in relation to ACP uptake).

Content analysis (17, 18) was used to organize and summarise the details of the interventions such as the various forms of delivery and intervention content. The implied barriers targeted by each of these interventions were coded to the Theoretical Domains Framework domains. For example, educational interventions imply that lack of knowledge is a barrier, whereas communication skills training implies that lack of skills or lack of confidence to discuss ACP are barriers, even if these assumptions are not explicit. This analysis was conducted by one author (LG) and reviewed by another author (JF). We also report on evidence of effectiveness of these interventions for improving documentation of ACP (research question 4).

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal assessment checklist for systematic reviews was used to assess the methodological quality of the systematic and scoping reviews included in this overview of reviews. This checklist consists of 10 items that address methodological characteristics of a review article including: appropriateness of search strategies, potential sources of bias, and prospects for future research and policy-making (24). Each item is scored as 1 (met) or 0 (not met, unclear, or not applicable) with item scores summed to calculate an overall score. Studies scoring 0-4, 5-7 and 8-10 points were categorized as low, medium, and high quality, respectively, as described by Hossain et al. (25).

The methodological quality of narrative reviews included in this overview was assessed using the Scale for the Quality Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) tool. The SANRA is a 6-item scale whereby each item is scored as 0 (low quality) to 2 (high quality), with item scores then summed; hence, the range of overall quality scores is 0-12. (Reviews scoring ≥9 are classified as high quality) (26).

All quality assessments were conducted by one reviewer (LG), with a second reviewer (SF) independently assessing a random selection of 20%. Minor differences in assessment were identified and discussed to reach consensus, or discussed with a third author (KG or MT). Reviews were not excluded based on quality assessment scores but any findings from reviews that received low scores were noted.

A total of 478 records from MEDLINE (n=56), PubMed (n=208), PsycInfo (n=27), CINAHL (n=92) EMBASE (n=95) were identified across all searches. Of these, 210 duplicates were removed. Following review of titles and abstracts, 29 records met the eligibility criteria and were retained for full text review. A further 11 records were excluded at initial full-text review, resulting in 18 records (12, 27–43) being included in the analysis (Figure 1).

The included reviews consisted of systematic reviews (n=6), scoping reviews (n=3) and narrative reviews (n=9), published from 2011 to August 4, 2021, with more than half of these in the period 2018-2020. The majority used mixed-methods with only four using purely quantitative methods. The reviews mostly included both patients and healthcare providers (n=10), with seven reviews involving patients only and one review of healthcare providers only.

All systematic reviews included in this overview were appraised as high quality. The three scoping reviews, also assessed using the JBI checklist, were appraised as low (n=1), medium (n=1), and high quality (n=1). The main criteria leading to low scores included unclear search strategy, poorly defined or missing inclusion criteria, and no appraisal of included studies, which is likely due to a lack of standardized reporting for scoping reviews whereby these details are often omitted (44).

SANRA scores for narrative reviews ranged from 5-10 points, with a median score of 9 points. Although there are no predefined quality categories for this scale, experience suggests a score ≤4 is indicative of poor quality (26). Study characteristics and quality assessment scores are summarized in Table 1.

ACP was defined in 16 of the 18 reviews (12, 27–31, 33–39, 41–43). The systematic (32) and narrative review (40)without a definition of ACP both scored the lowest on the JBI and SANRA quality assessment tools, respectively.

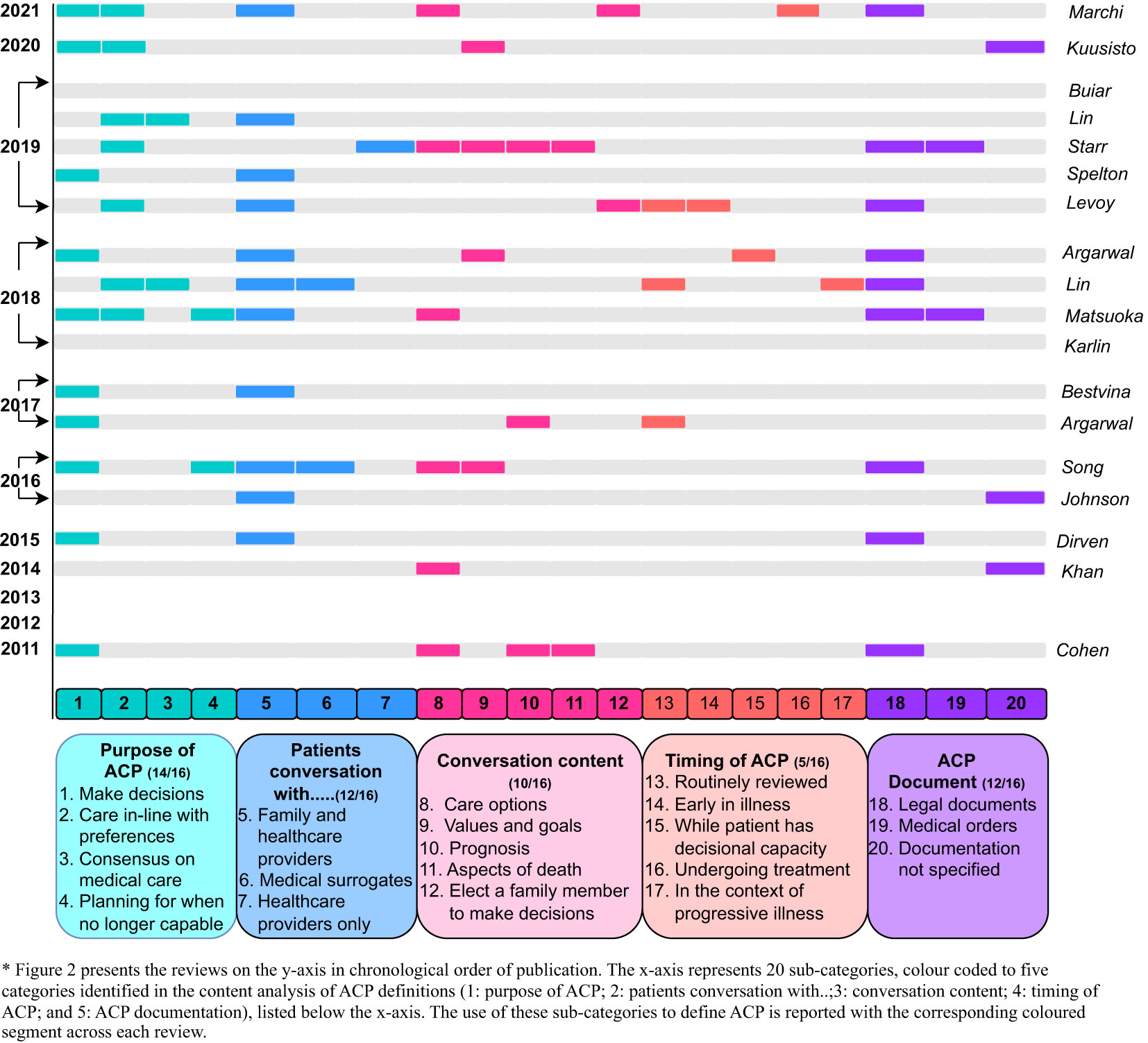

Figure 2 presents the content categories and sub-categories used to define ACP across all reviews, listed chronologically. Overall, it appears that a consistent definition of ACP has not developed over time. The most common combination of categories and subcategories used in defining ACP were as follows: ‘the purpose of ACP is—to make decisions’; ‘patients should have conversations with—family and healthcare providers’; conversations should cover—care options’; and ‘ACP should result in documentation—in the form of a legal document’. Notably, prior to 2017, the timing of ACP development was not included in any definition, and once present, not consistently described; although in the context of oncology settings, reviews included both terminal and non-terminal cancer patients (terminal patients only, n=6; non-terminal patients, n=4; and unclear, n=8).

Figure 2 Chronological mapping of categories identified in the content analysis of ACP definitions across reviews.

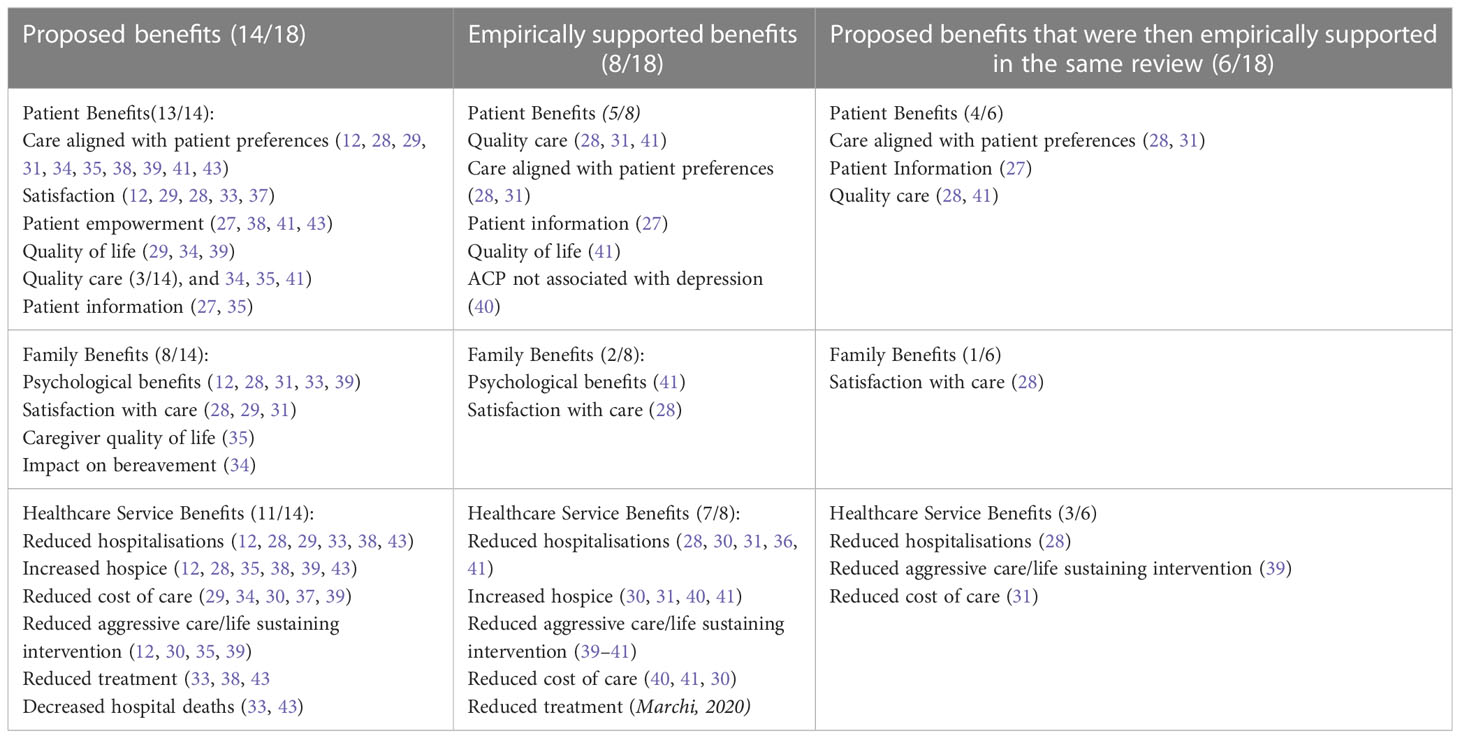

Content analysis identified three categories of proposed and empirically supported benefits of ACP: patient benefits, family benefits, and healthcare service benefits, presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Summary of proposed and identified benefits of ACP by content categories and frequencies of sub-categories for each.

A misalignment was found between the proposed and empirically supported benefits of ACP, with many proposed benefits for patients, families, and healthcare providers not empirically supported within the same review. In terms of patient benefits, only ‘quality care’, ‘patient information’ and ‘care alignment’ had both proposed and empirically supported benefits (27, 28, 31, 41). For families, only ‘satisfaction with care’ was proposed as a benefit and empirically supported in the same review (28). Assessment of health care service benefits identified reduced hospitalization, reduced aggressive care, and reduced cost of care, as both proposed and empirically supported (28, 30, 39).

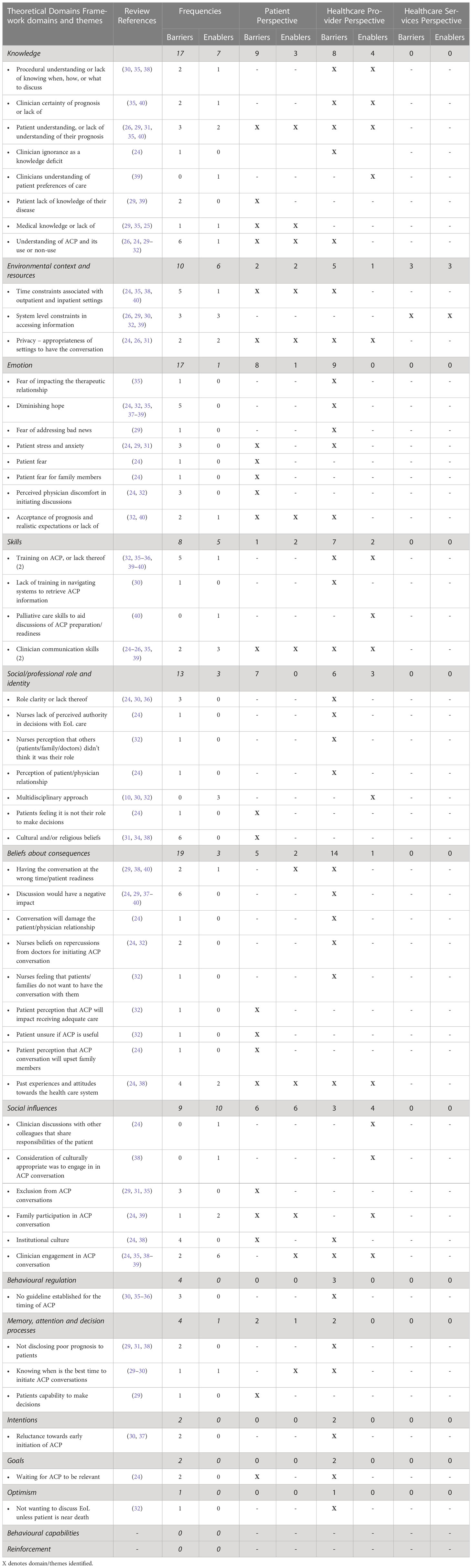

A deductive analysis identified barriers and enablers of ACP across 12 of the 14 Theoretical Domains Framework domains from 15/18 reviews (12, 27–29, 32–35, 37–43). Table 3 presents frequencies of the barriers and enablers by Theoretical Domains Framework domain, and content themes identified within each domain from the patient, healthcare provider, and healthcare service perspectives. More barriers of ACP were associated with healthcare providers (n=60) in comparison to patients (n=40) and healthcare services (n=3). Enablers of ACP were more frequently identified for patients (n=17) compared to healthcare providers (n=15) and healthcare services (n=3).

Table 3 Theoretical Domains Framework domains and themes of barriers and enablers across patient, healthcare provider, and healthcare services perspectives.

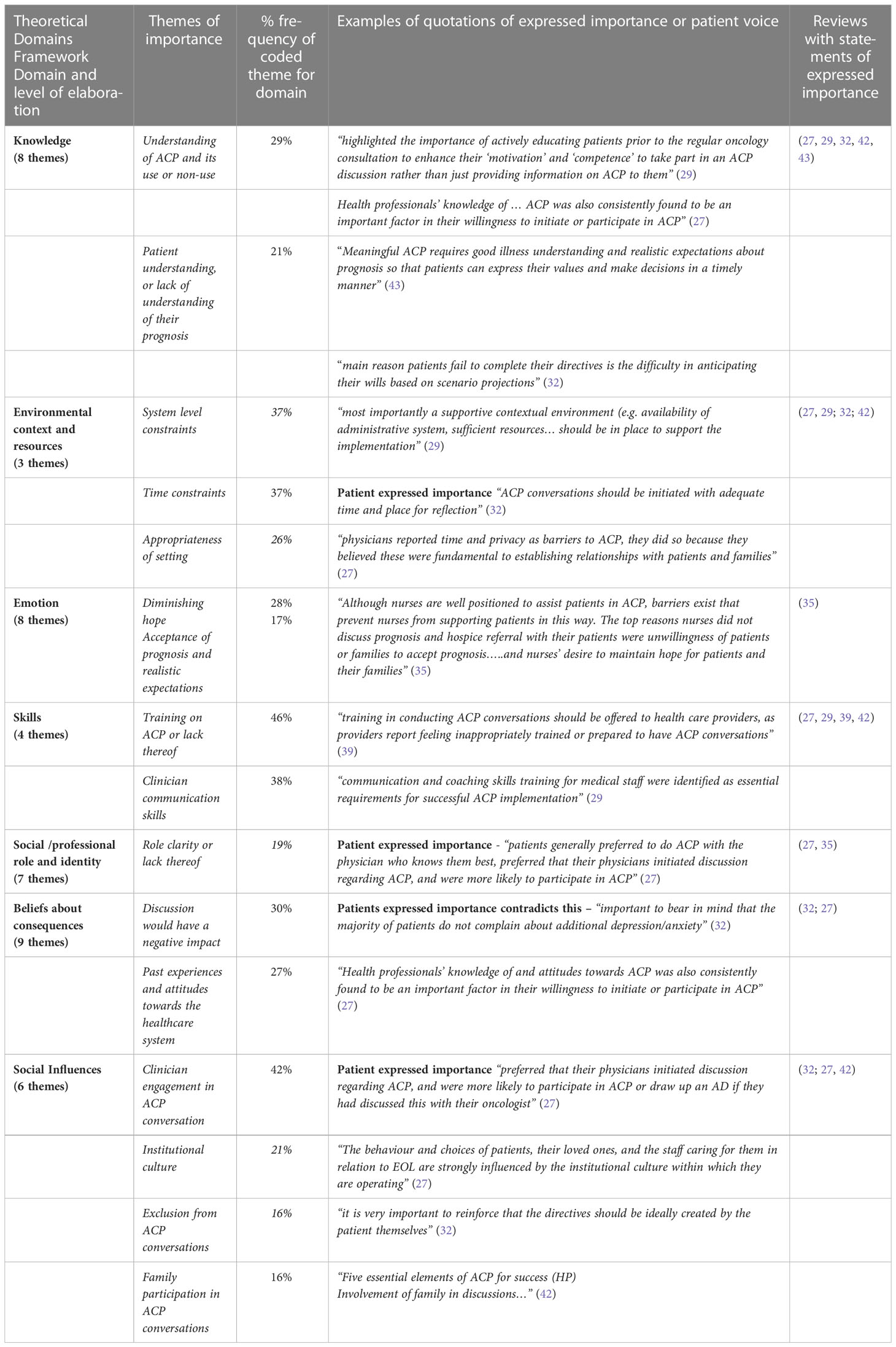

As described in the method, we assessed importance in relation to three previously published criteria: domain frequency, level of elaboration within each domain, and authors’ explicit statements about importance (22, 23). Of 14 possible domains, the most frequently coded across the 15 reviews were: knowledge (66%); environmental context and resources (66%); emotion (66%); skills (60%); social/professional role and identity (53%); beliefs about consequences (46%); and social influences (40%). High levels of elaboration were found in the most frequently coded domains, except for those where minimal themes are to be expected: for example, skills whereby communication and training were predominant.

Evidence of importance was further supported by the authors of reviews articulating specific barriers or enablers as important in influencing ACP; for example, “Health professionals’ knowledge of and attitudes towards ACP was also consistently found to be an important factor in their willingness to initiate or participate in ACP” (27). Importance was also inferred in statements that articulated the patient’s voice; for example, “Patients generally preferred to do ACP with the physician who knows them best, preferred that their physicians initiated discussion regarding ACP, and were more likely to participate in ACP or draw up an advance directive (AD) if they had discussed this with their oncologist” (27).

Statements of expressed importance were identified in seven reviews (27, 29, 32, 35, 39, 42, 43) and these aligned with the seven most frequently coded domains with the greatest level of elaboration: knowledge (n=5); skills (n=4); environmental context and resources (n=4); social influences (n=3); beliefs about consequences (n=2); social/professional role and identity (n=2); and emotion (n=1). High frequency content themes within these domains also aligned with expressed statements of importance. Details on domains of importance and example quotations are presented in Table 4. Supplementary File 3 presents a narrative description and sample quotations for all themes across Theoretical Domains Framework domains.

Table 4 Theoretical Domains Framework domains of importance in influencing behaviours related to ACP; identified themes and quotations of expressed importance.

Nine of the 18 reviews identified interventions that aim to improve ACP uptake at various phases and target either the patient, healthcare provider, or healthcare service levels (12, 28, 29, 31, 32, 38–40, 43). In Figure 3, interventions have been mapped to the phases of ACP as presented by the Australian National Framework for advance care planning documents (45), with the addition of a preparatory phase, labelled Phase 1a. This figure also depicts the intervention target and interactions associated with delivering the intervention.

Seven reviews reported interventions that targeted the patient (12, 28, 29, 38–40, 43). Reporting of intervention effectiveness varied. Patient education tools were effective in increasing ACP documentation. Interventions that involved websites, patient prompts and/or patient tools to improve communication resulted in increased discussions of end-of-life issues and patients asking more questions (12, 29, 39, 43). Video-decision aid interventions increased knowledge scores and patients were less likely to opt for life-sustaining care (12, 28, 38–40). Consultation-based interventions did not report any effectiveness in improving ACP (12).

Multimodal interventions did not result in changes to ACP documentation, healthcare utilization, patient quality-of-life, consultation length, or communication self-efficacy. However, patients’ willingness to discuss end-of-life care, patient-physician communication, and patient knowledge and confidence in decision-making were enhanced (29, 38, 43).

Three reviews reported interventions that targeted the healthcare provider (31, 32, 39). Interventions that used clinician resources reported an increase in ACP discussion (32, 39). Clinician reminders (email reminders to address goals of care) increased ACP documentation from 14.5% to 33.7% (39).

Interventions providing clinician training administered the Serious Illness care program (39), interactive training (31), or training to improve clinician communication (32). These interventions were associated with an increase in discussions, earlier initiation of ACP discussions, and an increase in clinician confidence in initiating ACP conversations. However, they had little impact on ACP documentation.

Three interventions targeted healthcare services (32, 39). Intervention effectiveness was not reported; however, an Advance Directive was documented for 33 of 48 patients, with the availability of an EMR note template (39).

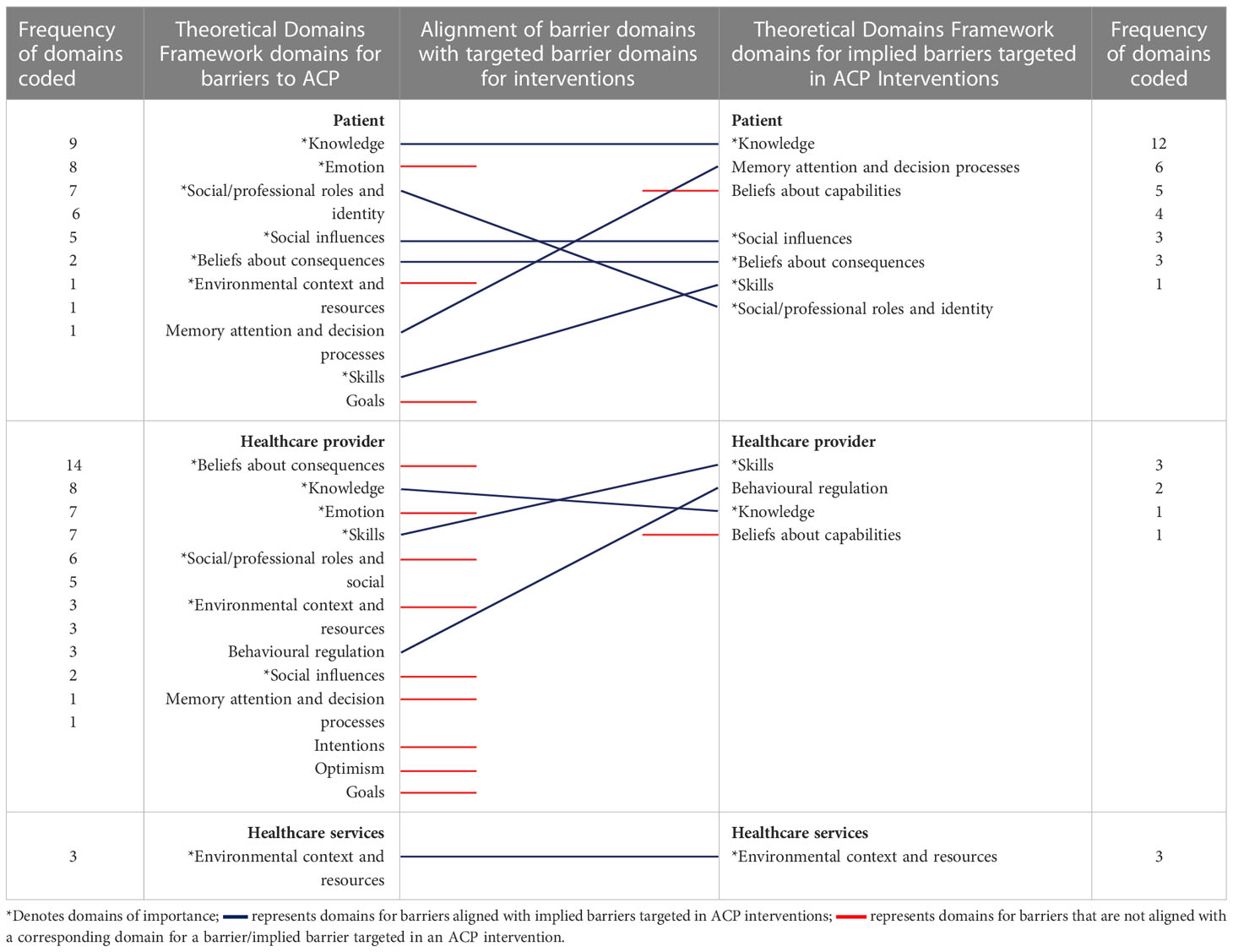

Table 5 compares the frequencies of Theoretical Domains Framework domains for barriers of ACP with the Theoretical Domains Framework domains for implied barriers targeted by ACP interventions across patient, healthcare provider, and healthcare systems levels. Across levels, there was a misalignment between barriers identified and implied barriers targeted by interventions. Interventions most frequently targeted the patient; however, more barriers for ACP were identified for healthcare providers. There were also implied barriers targeted by ACP interventions that were not identified as barriers to ACP in the included reviews. This occurred for interventions targeting the patient as well as the healthcare provider.

Table 5 Frequencies of the Theoretical Domains Framework domains for barriers of ACP and barriers targeted by ACP interventions.

● Five common categories were identified when defining ACP. However, these were not consistently applied across reviews, and there was no emergence of a clear definition of ACP over time.

● The most common combination of categories/subcategories used in defining ACP were: the purpose of ACP is to make decisions; patients should have conversations with family and healthcare providers; conversation should cover care options; and ACP should result in documentation (in the form of a legal document).

● There were more proposed than empirically supported benefits for ACP. There were no proposed or empirically supported benefits for the healthcare provider.

● A greater number of barriers for ACP were associated with the healthcare provider than the patient, or healthcare service. Enablers of ACP were greater for the patient than the healthcare provider or service.

● The majority of interventions to improve ACP target the patient rather than healthcare providers. Implied barriers that were targeted by ACP interventions and coded to Theoretical Domains Framework domains did not align with barriers identified in the included reviews as the most important in influencing ACP.

● Theoretical Domains Framework Effectiveness of ACP interventions varied. Interventions targeting identified barriers tended to be more effective.

Based on this systematic overview of reviews, consistency is lacking in the literature in relation to defining ACP, its benefits, and its barriers and enablers in oncology settings. While the peer-reviewed literature lacks a consensus definition, there are key categories and sub-categories that align with the benefits of ACP and overarching values associated with optimal patient care that should be consistently used in its definition. The most frequently used sub-categories to define the purpose of ACP are about making decisions to ensure that the patient receives care in-line with their preferences. Receiving care that is in-line with one’s preferences and values is the hallmark of patient-centered care (46) and known to improve care quality and patient satisfaction (47). It is also one of the empirically supported benefits of ACP (28, 41). We suggest that these content categories should be included in the standardized definition of ACP (presented in Figure 4), along with identifying who should participate in the conversation. Evidence suggests the involvement of family and healthcare providers in ACP conversations is an enabler for the patient and healthcare provider for ACP uptake (27, 41–43).

The lack of consensus around the timing of ACP should be addressed within oncology settings, as this is also associated with barriers for healthcare providers not knowing when to initiate the conversation (32, 41, 43). It is important to consider that, within this patient population, the timing of conversations does not necessarily have a negative impact on patients (40) but, rather, consideration of contextual factors is important, such as having the conversation in an appropriate and private setting important (27, 29, 34). Whilst there is agreement within the literature (12, 28, 30, 31, 35, 37, 41–43) and also in the Australian National Framework of ACP (45), that ACP should result in a legal document, emphasizing the importance of this step, we found no mention of barriers associated with creating this document or any process or person to facilitate this process. Nor did any interventions target this phase of ACP.

Interventions predominantly focused on a preparatory phase of ACP, which we identified as Phase 1a (Figure 3): Preparation for the ACP conversation; currently beyond the scope of the Australian National Framework of ACP, which primarily focusses on three phases ACP; 1) having the conversation; 2) making an ACP document; and 3) accessing and enacting an ACP document (45). Interventions to enhance the uptake of ACP sometimes, but not always, addressed the known barriers and there appeared to be considerable variation in these interventions to improve ACP uptake. They also tended to target the patient rather than healthcare providers, even though the number of barriers associated with healthcare providers were a third greater than those for patients.

Further expanding the ‘importance criteria’ to a theme level enabled us to identify the mismatch of interventions in targeting empirically identified problems. Interventions that targeted patients did address patient barriers that were coded to important domains, and to some extent were effective in increasing ACP documentation. However, these interventions aimed to improve the knowledge of patients on end-of-life care decisions and gaining medical knowledge, yet the most important knowledge enabler was for patients to have an understanding of their prognosis. Interventions also focused on communication between patients and clinicians. While these interactions are important, the involvement of family members in the process of ACP was an enabler for both patients and healthcare providers. Yet, no interventions focused on educating and actively engaging family members in ACP. This is despite empirically supported psychological benefits and satisfaction with care being linked to the involvement of family members (28, 41).

Few interventions targeted empirically identified problems for healthcare providers, and these were mostly ineffective in increasing ACP documentation. These interventions targeted barriers coded to only two of the seven domains identified as important in influencing ACP uptake for healthcare providers (i.e., skills and knowledge); and were placed in phase 1 of the Australian National Framework of ACP (45). Interventions have failed to address the most frequently reported barriers for healthcare providers, specifically, beliefs that ACP conversations would have a negative impact on patients. This is in spite of patient accounts that this assumption is incorrect and contrary to empirically identified benefits for patients (40).

The pathways from having the ACP conversation to phase 2 of the Australian National Framework of ACP, making an ACP document, were not discussed in the literature reviewed in this overview. The barriers and enablers of making an ACP document have not been explored in the literature, nor addressed in any interventions. Yet, national frameworks identify this as a phase of successful ACP, consistent with many definitions that state ACP should result in some form of documentation. Interventions addressing phase 3 of the framework, accessing and enacting an ACP document, did not report effectiveness in improving ACP. System-level constraints was one of three themes coded to the domain of environmental context and resources and identified as important in influencing ACP uptake.

In summary of the findings discussed above, we recommend that future ACP interventions and research focus on:

● Interventions that target educating family members and actively engaging family in ACP.

● Interventions that encourage the discussion and understanding of prognosis;

● Interventions that challenge clinician beliefs— about understanding the impact and benefits of ACP; and

● The importance of context and availability of resources.

While there is the lack of emergence of a clear definition of ACP in the academic literature, governments and non-governmental organizatisations may employ more complete definitions that were not included in this review; such as the one proposed in the Australian National Framework of ACP (45). The scope of the inclusion criteria for this overview may have also excluded other interventions for ACP that were not trialed only in cancer populations and, therefore, were not included in this analysis. It is possible that additional barriers and enablers of ACP, as well as potentially effective interventions, may also be relevant for cancer populations but have not been identified or included in this review.

In conclusion, this overview of reviews has identified key categories of content that should be included in defining ACP. These address the most frequently used sub-categories and are consistent with empirically supported benefits of ACP. We have also identified that, in many cases, proposed benefits of ACP did not actualize into empirically supported benefits. This was most evident for empirically supported benefits for patients and family members. No benefits of ACP were reported in the literature for healthcare providers. Lastly, interventions tended to target a different population and barriers than the ones the majority of evidence identified as a problem. Implications for this are that, in targeting an imagined problem as opposed to one that has been empirically identified we are unlikely to be effective in changing ACP uptake. Future interventions for ACP should target the domains of importance identified and address key barriers to change the behaviours of healthcare providers and improve ACP uptake.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

LG conducted the search. Authors LG and SF screened reviews for inclusion and conducted the data extraction. LG, JF, AH and KG participated in the analysis of results. Writing of the original draft manuscript was prepared by LG. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1040589/full#supplementary-material

1. Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European association for palliative care. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18:e543–51. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30582-x

2. Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28:1203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672

3. Buck K, Detering K, Sellars M, White B, Kelly H, Nolte L, et al. Prevalence of advance care planning documentation in Australian health and residential aged care services: Report, Vol. 2019. (2019).

4. Watson A, Weaver M, Jacobs S, Lyon ME. Interdisciplinary communication: Documentation of advance care planning and end-of-Life care in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Hosp Palliat Nurs (2019) 21:215–22. doi: 10.1097/njh.0000000000000512

5. Brown AJ, Shen MJ, Urbauer D, Taylor J, Parker PA, Carmack C, et al. Room for improvement: An examination of advance care planning documentation among gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol (2016) 142:525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.07.010

6. Korfage IJ, Carreras G, Arnfeldt Christensen CM, Billekens P, Bramley L, Briggs L, et al. Advance care planning in patients with advanced cancer: A 6-country, cluster-randomised clinical trial. PloS Med (2020) 17:e1003422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003422

7. Fried TR, O’Leary JR. Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient-and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Internal Med (2008) 23:1602–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0748-0

8. Risk J, Mohammadi L, Rhee J, Walters L, Ward PR. Barriers, enablers and initiatives for uptake of advance care planning in general practice: a systematic review and critical interpretive synthesis. BMJ Open (2019) 9:e030275. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030275

9. O’Caoimh R, Cornally N, O’Sullivan R, Hally R, Weathers E, Lavan AH, et al. Advance care planning within survivorship care plans for older cancer survivors: a systematic review. Maturitas (2017) 105:52–7. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.06.027

10. Somal K, Foley T. A literature review of possible barriers and knowledge gaps of general practitioners in implementing advance care planning in Ireland: Experience from other countries. Int J Med Students (2021) 9:145–56. doi: 10.5195/ijms.2021.567

11. Chan B, Sim H-W, Zimmermann C, Krzyzanowska MK. Systematic review of interventions to facilitate advance care planning (ACP) in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol (2016) 34. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.34.26_suppl.21

12. Levoy K, Salani DA, Buck H. A systematic review and gap analysis of advance care planning intervention components and outcomes among cancer patients using the transtheoretical model of health behavior change. J Pain Symptom Manage (2019) 57:118–39:e116. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.502

13. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libraries J (2009) 26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

17. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Advanced Nurs (2008) 62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

18. Forman J, Damschroder L. Qualitative content analysis. In: Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited (2007).

19. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product ESRC Methods Programme Version (2006) 1:b92.

20. Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O'Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Sci (2017) 12:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

21. Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Sci (2012) 7:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

22. Graham-Rowe E, Lorencatto F, Lawrenson JG, Burr JM, Grimshaw JM, Ivers NM, et al. Barriers and enablers to diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: Protocol for a systematic review. System Rev (2016) 5:134. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0309-2

23. Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM, Canada PRIME Plus Team. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the theoretical domains framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implementation Sci (2012) 7:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-52

24. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P, et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid Implementation (2015) 13:132–40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

25. Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: a systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiol Health (2020) 42:1–11. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020038

26. Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA–a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integrity Peer Rev (2019) 4:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

27. Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, Tattersall M. Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review of perceptions and experiences of patients, families, and healthcare providers. Psycho-oncology (2016) 25:362–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.3926

28. Song K, Amatya B, Voutier C, Khan F. Advance care planning in patients with primary malignant brain tumors: a systematic review. Front Oncol (2016) 6:223. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00223

29. Lin C-P, Evans CJ, Koffman J, Armes J, Murtagh FEM, Harding R, et al. The conceptual models and mechanisms of action that underpin advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Palliative Med (2019) 33:5–23. doi: 10.1177/0269216318809582

30. Starr LT, Ulrich CM, Corey KL, Meghani SH. Associations among end-of-life discussions, health-care utilization, and costs in persons with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Am J Hospice Palliative Medicine® (2019) 36:913–26. doi: 10.1177/1049909119848148

31. Marchi LPS, Santos Neto MF, Moraes JWP, Paiva CE, Paiva BSR. Influence of advance directives on reducing aggressive measures during end-of-life cancer care: A systematic review. Palliative Supportive Care (2021) 19:348–54. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000838

32. Buiar PG, Goldim JR. Barriers to the composition and implementation of advance directives in oncology: a literature review. Ecancermedicalscience (2019) 13:1–12. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2019.974

33. Kuusisto A, Santavirta J, Saranto K, Korhonen P, Haavisto E. Advance care planning for patients with cancer in palliative care: A scoping review from a professional perspective. J Clin Nurs (2020) 29:2069–82. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15216

34. Spelten ER, Geerse O, van Vuuren J, Timmis J, Blanch B, Duijts S, et al. Factors influencing the engagement of cancer patients with advance care planning: A scoping review. Eur J Cancer Care (2019) 28:e13091. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13091

35. Cohen A, Nirenberg A. Current practices in advance care planning. Clin J Oncol Nurs (2011) 15:547–53. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.547-553

36. Khan SA, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. End-of-life care–what do cancer patients want? Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2014) 11:100–8. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.217

37. Dirven L, Sizoo EM, Taphoorn MJ. Anaplastic gliomas: end-of-life care recommendations. CNS Oncol (2015) 4:357–65. doi: 10.2217/cns.15.31

38. Agarwal R, Epstein AS. Palliative care and advance care planning for pancreas and other cancers. Chin Clin Oncol (2017) 6:32. doi: 10.21037/cco.2017.06.16

39. Bestvina CM, Polite BN. Implementation of advance care planning in oncology: a review of the literature. J Oncol Pract (2017) 13:657–62. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.021246

40. Karlin D, Phung P, Pietras C. Palliative care in gynecologic oncology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol (2018) 30:31–43. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000426

41. Lin C-P, Cheng S-Y, Chen P-J. Advance care planning for older people with cancer and its implications in Asia: highlighting the mental capacity and relational autonomy. Geriatrics (2018) 3:43. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics3030043

42. Matsuoka J, Kunitomi T, Nishizaki M, Iwamoto T, Katayama H. Advance care planning in metastatic breast cancer. Chin Clin Oncol (2018) 7:33. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.06.03

43. Agarwal R, Epstein AS. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making for patients with cancer. In: Seminars in oncology nursing, vol. pp. WB Saunders: Elsevier (2018) 34(3):316–26.

44. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Method (2016) 16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

46. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–the pinnacle patient-centered care. (2012) 66(9):780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283

Keywords: advance care planning (ACP), barriers and enablers, healthcare provider (HCP), improving uptake, patient-centered care, theoretical domains framework

Citation: Guccione L, Fullerton S, Gough K, Hyatt A, Tew M, Aranda S and Francis J (2023) Why is advance care planning underused in oncology settings? A systematic overview of reviews to identify the benefits, barriers, enablers, and interventions to improve uptake. Front. Oncol. 13:1040589. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1040589

Received: 09 September 2022; Accepted: 24 March 2023;

Published: 28 April 2023.

Edited by:

Marine Hovhannisyan, Yerevan State Medical University, ArmeniaReviewed by:

Stéphane Sanchez, Centre Hospitalier de Troyes, FranceCopyright © 2023 Guccione, Fullerton, Gough, Hyatt, Tew, Aranda and Francis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa Guccione, bGlzYS5ndWNjaW9uZUBwZXRlcm1hYy5vcmc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.