94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol., 23 September 2022

Sec. Gastrointestinal Cancers: Hepato Pancreatic Biliary Cancers

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.978614

This article is part of the Research TopicCombining Localised and Systemic Therapy Options for Advanced Hepatocellular CarcinomaView all 16 articles

Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy and survival of Hepatitis C virus (HCV) -related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) undergoing percutaneous thermal ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE).

Methods: A total of 83 HCV-related HCC patients who were treated with percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE were retrospectively analyzed. The demographic and clinical data were collected. The overall survival (OS) and recurrence free survival (RFS) rates were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to assess independent risk factors of OS and RFS.

Results: 92.8% patients (77/83) and 96.6% (170/176) tumor lesions achieved complete response (CR) 1 month after all treatment, and 10.8% (9/83) patients had minor complications. The median OS was 60 months (95% confidence interval (CI)= 48.0-72.0), and the 1-, 2-, 3-, 5- and 10-year cumulative OS rates were 94%, 78.3%, 72.3%, 43.4% and 27.5%, respectively. The cumulative RFS rates at 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year were 74.7%, 49.3%, 30.7% and 25.3%, respectively. Sex (HR =0.529, P=0.048), ablation result (HR=5.824, P=0.000) and Albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score (HR=2.725, P=0.011) were independent prognostic factors for OS. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (HR =2.360, P = 0.005) and tumor number(HR=2.786, P=0.000) were independent prognostic factors for RFS.

Conclusions: Percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE is a safe and effective treatment for HCV-related HCC. Sex, ablation result and ALBI are significant prognostic factors for OS. AFP and tumor number are significant prognostic factors for RFS.

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world, accounting for the fourth cause of cancer death worldwide in 2018, with about 841000 new cases and 782000 deaths each year (1). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for about 85-90% of all primary liver cancers (2). Hepatitis virus B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the main risk factors for HCC (3, 4). Although the incidence of HCV-related HCC is lower than that of HBV-related HCC, with the aging and population growth, the expected burden of HCV-related HCC in China is rising (5). Curative therapies for early-stage HCC includes surgical resection, liver transplantation and percutaneous ablation. Owing to cirrhosis almost accompanying all HCV-related HCC, percutaneous ablation, especially thermal ablation is usually useful alternative modalities for these patients. Recent studies have showed that percutaneous ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) may have synergistic effect in the treatment of early and intermediate stages HCC (6). However, there are few studies focused on the efficacy and prognosis of HCV-related HCC receiving percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE.

In this study, we aimed to identify the efficacy, safety and survival of HCV-related HCC after percutaneous thermal ablation with TACE in HBV-endemic area.

We retrospectively reviewed a total of 507 consecutive treatment-naive patients with HCC who underwent percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE at Beijing You An Hospital, Capital Medical University from July 2006 to January 2016. Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) HCV-infected patients; (2) a single tumor with a maximum size smaller than 7 cm and tumor number less than 5; (3) no invasion of adjacent organs or tumor thrombi in portal, vein and bile ducts system, and no extrahepatic metastasis; (4) no serious non-liver underlying illness including heart, brain, lung, kidney and other organs dysfunction, and no other tumor diseases; (5) liver function of Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class A and B; ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance status score 0~1; (6) platelet count ≥50 × 109/L for percutaneous thermal ablation, prothrombin time ratio ≥ 50% and total bilirubin<50umol/L for both TACE and percutaneous thermal ablation; (7) no upper digestive track bleeding due to portal hypertension within 1 month before TACE; (8) no uncontrolled infection; (9) complete case and follow-up data. This research scheme has been exempted from the requirement of informed consent and approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital. As summarized in Figure 1, among the 507 patients, the remaining 83 patients met the inclusion criteria, including 30 patients who were diagnosed with HCC histologically by liver biopsy, and another 53 patients, who were diagnosed by imaging diagnosis.

The pretreatment assessment of each patient included spiral computed tomography (CT) of chest, either Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) or contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CEMRI) of the abdomen, electrocardiogram, complete blood count (CBC), liver and renal function tests, prothrombin time, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), HCV RNA. According to the guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer (China, 2017 edition) (7), patients with maximum tumor diameter 1-2cm confirmed by 2 typical contrast enhancement imaging presentations, or maximum tumor diameter more than 2cm confirmed by 1 typical contrast enhancement imaging presentations or histopathological examinations were diagnosed with HCC.

We collected baseline clinical data including: age, gender, CBC, albumin (ALB), total bilirubin(TBIL), glutamic pyruvic transaminase(ALT), glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase(AST), cholinesterase(CHE), prothrombin time(PT), AFP, CTP grade, tumor characteristics. We calculated Albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score as follows, ALBI = 0.66 × Log10(TBIL μmol/L) -0.085 ×(ALB g/L). ALBI grade was classified as grade 1 (≤−2.60), grade 2 (−2.60 to −1.39), or grade 3 (>−1.39), respectively.

All TACE are conventional-TACE(c-TACE). TACE was performed first.Seldinger catheterization was used to intubate the right femoral artery, and angiography of the hepatic artery was performed to observe the location, size, number, arterial supply of tumors. Catheters and microcatheters (Asahi Intecc Co., Ltd., Japan) was inserted into the target branch. Iodized oil (Guerbet, Villepinte, Seine-Saint-Denis, France), and doxorubicin (Pfizer Inc., NY, USA) suspension emulsion were injected into the arterial branches followed by injection of gelatin sponge particles (350~560um, Hangzhou Alicon Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. Hangzhou, China). The dose of the drugs depended on the tumor size, liver function, white blood cell count and platelet count of the patient. One week later, CT scan of the abdomen was performed to evaluate the effect of TACE. The TACE procedure was repeated if the effect was not satisfactory.

Thermal ablation was carried out within 2 weeks after TACE. CT scanning was performed to determine the puncture site and approach. After routine sterilization and focal anesthesia, the RFA electrode needle or microwave antenna was used to puncture the tumor under CT guidance. The ablation was performed according to the predetermined ablation conditions. According to the ablation range of each tumor, the RFA electrode needles or microwave antennas were adjusted to achieve an overlapping ablative margin that would theoretically include the tumor and 0.5~1 cm of surrounding tissue. After the ablation range was satisfied, the electrode needle or microwave antennas were withdrawn, and the needle tunnel was ablated at 70°C-90°C to reduce the risk of hemorrhage or implantation metastasis via the needle tunnel. CECT or CEMRI of the abdomen was performed within 1 week after ablation to evaluate technique effectiveness. If the imaging examination showed an enhanced area within or around the original tumor, we suspected that incomplete ablation portions remained, and the RFA/MWA procedure was repeated if the liver function met the requirements.

Treatment was continued until CT or MRI imaging demonstrated necrosis of the entire tumor. CECT or CEMRI was performed one month after the treatment to determine the effects of ablation, which were classified as complete response (CR) or incomplete response (ICR). CR was defined as CECT or CEMRI detection of a non-enhanced area with necrosis at the ablation site of the HCC nodules. Patients with CECT or CEMRI evidence lacking CR were defined as ICR and received repeated salvage RFA/MWA treatment. The evaluations were repeated 1month after salvage treatment. Those who failed to obtain CR after repeated salvage RFA/MWA were regarded as treatment failure (TF). In these cases, liver transplantation, resection, TACE, or other treatments were considered.

The follow-up protocol included AFP assays, CECT or CEMRI of the abdomen and liver function every 3 months after treatment and more frequently when needed. CT of chest was performed every 6 months or if tumor recurrence was suspected. Tumor recurrence includes local recurrence, intrahepatic recurrence and extrahepatic recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between the date of the initial TACE and the death, or the end of the study for patients who survived. Recurrence free survival (RFS) was defined as the interval between the date of the CR and the recurrence or death or the end of the study for patients who did not experience recurrence.

SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to statistically analyze data. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as medians, ranges. Survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The OS and RFS rates were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analysis was carried out by Cox proportional hazards regression model to assess independent risk factors of OS and recurrence. P<0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics of the 83 patients who underwent percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE were showed in Table 1.

Among the 83 treated patients, 80 patients underwent a single TACE, and 3 patients underwent two TACE for successful embolization of the tumor artery. We performed 110 thermal ablation including 89 RFA and 21 MWA for 176 tumor lesions in 83 patients. 58 patients underwent a single thermal ablation, 23 patients underwent two thermal ablation and 2 patients were treated with three thermal ablation in order to achieve the complete response. 92.8% patients (77/83) and 96.6% (170/176) tumor lesions achieved CR 1 month after all treatment, and 7.2% (6/83) patients and 3.4% (6/176) tumor lesions were identified as ICR. 100% patients in the BCLC-0 group, 97.9% (46/47) in the BCLC-A group and 81.5% (22/27) in the BCLC-B group achieved CR.

During treatments, there were no serious adverse reactions such as liver failure, biliary bleeding, abdominal bleeding, pericardial tamponade, liver abscess and treatment-related death. 10.8% (9/83) patients had minor complications such as puncture point pain, liver pain, fever, nausea and vomiting, abdominal distension, mild liver function injury, ascites or pleural effusion, and recovered by conservative treatment.

Until January 31st 2020, the median follow-up period was 73months (ranging from 7-139months). At the end of follow-up, 57.8%(48/83) patients died and 42.2%(35/83) patients survived. The median OS was 60 months (95% confidence interval (CI)= 48.0-72.0), and the 1-, 2-, 3-, 5- and 10-year cumulative OS rates were 94%, 78.3%, 72.3%, 43.4% and 27.5%, respectively. The 1-, 2-, 3-, 5- and 10-year cumulative OS rates in patients with BCLC−0/A HCC were 98.2%, 89.3%, 83.9%, 51.4%, 32.7%, and 85.2%, 55.6%, 48.1%, 27.2% in patients with BCLC−B. There was significant difference in OS among the two groups (χ2 = 10.134, P=0.001)(Figure 2).

During the follow-up period, 77.9%(60/77) patients who achieved CR from the thermal ablation combined with TACE experienced recurrence. The cumulative RFS rates at 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year were 74.7%, 49.3%, 30.7% and 25.3%, respectively. The median RFS of BCLC BCLC-0/A/B HCC was 32 months (95% CI= 23.1-40.9), 28 months (95% CI= 18.9-37.1) and 18 months (95% CI= 15.9-20.1), respectively.

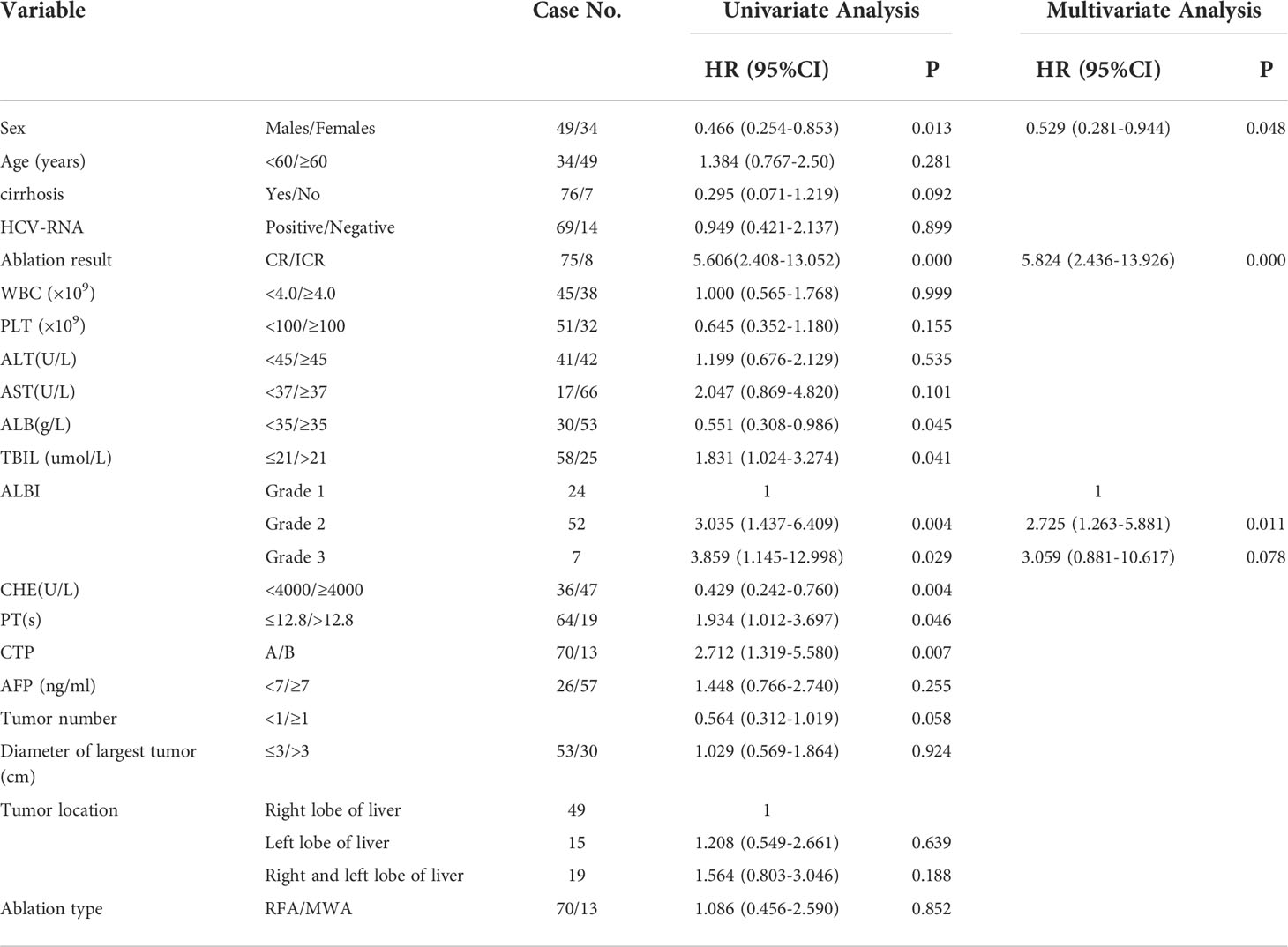

The factors associated with OS were summarized in Table 2. Univariate analysis

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival after percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE in patients with HCV-related HCC.

indicated 8 factors were related with OS, and multivariate analysis confirmed that only three factors including sex (HR =0.529, P= 0.048), ablation result (HR=5.824, P=0.000), ALBI (HR=2.725, P=0.011)were independent prognostic factors for OS.

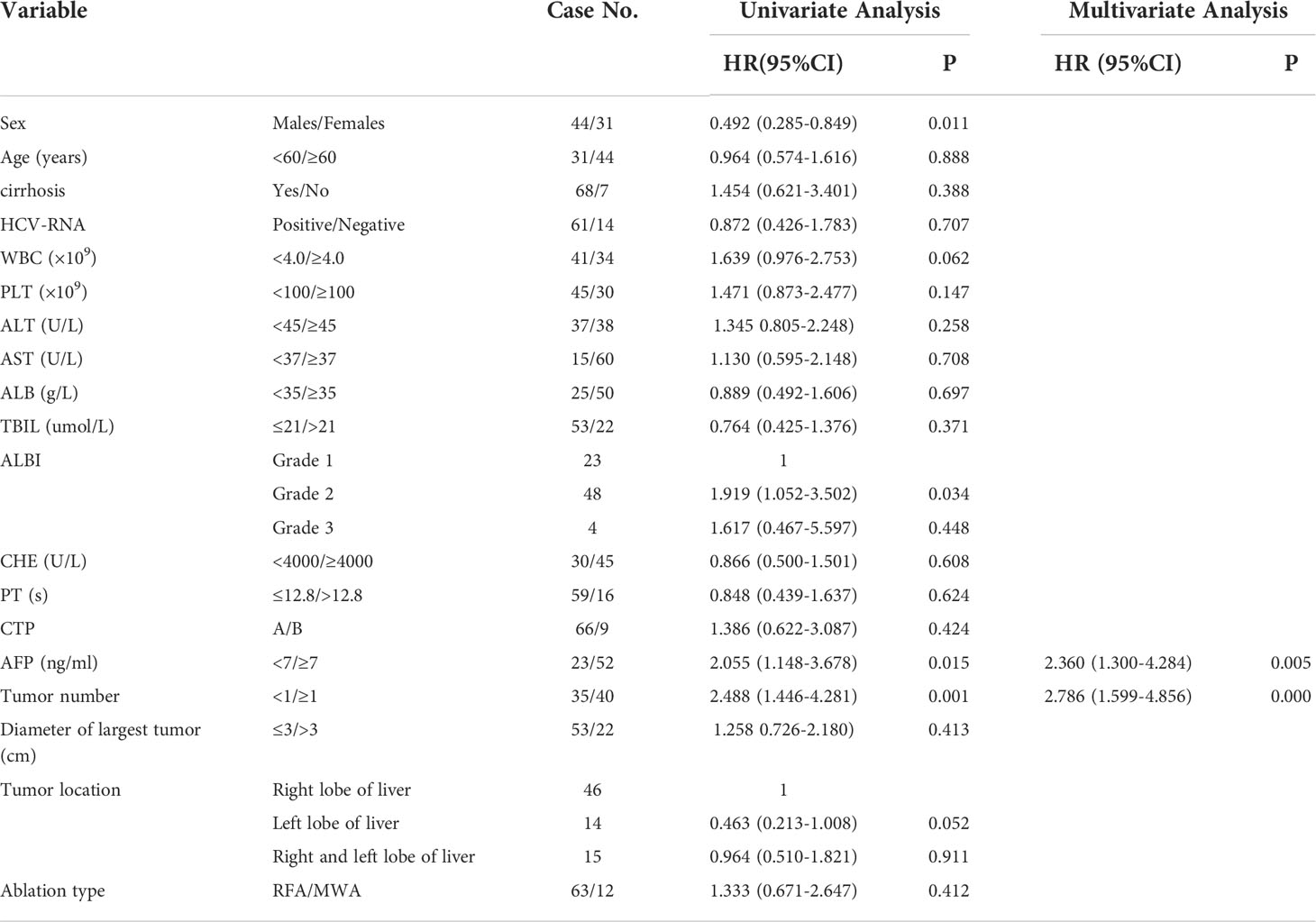

The factors associated with RFS were summarized in Table 3. Univariate analysis

Table 3 Univariate and multivariate analysis of RFS after percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE in patients with HCV-related HCC.

indicated 4 factors were related with RFS, and multivariate analysis confirmed that two factors including AFP (HR =2.360, P = 0.005) and tumor number (HR=2.786, P=0.000) were independent prognostic factors for RFS.

Percutaneous thermal ablation is considered to be the optimum local treatment for patients with early-stage unresectable lesions, liver cirrhosis or elderly patients. Percutaneous MWA had similar therapeutic effects and complication rate compared with RFA for HCC (8). Recent studies revealed that combination of thermal ablation and TACE is an effective option for patients with early or intermedium stage HCC (6, 9). TACE prior to percutaneous ablation can not only block the feeding arteries to reduce tumor burden, but also detect satellite nodules and label range of carcinoma. This treatment mode can increase complete ablation rate and reduce the risk of ablation-related bleeding (10). Zhen et al. (11) divided 189 patients into two groups (RFA group, TACE-RFA group); they found that the 1-, 3-, and 4-year OS for the RFA group and the TACE-RFA group were 85.3%, 59%, and 45.0% and 92.6%, 66.6%, and 61.8%, respectively (HR=0.525, 95% CI:0.335-0.822, P=0.002), and the corresponding RFS were 66.7%, 44.2%, and 38.9% and 79.4%, 60.6%, and 54.8%, respectively(HR=0.575, 95% CI:0.374 to 0.897, P = 0.009).

In this study, the CR rate at 1 month was 96.6% in the combination treatment similar to the obtained in previous studies (12). In subgroup analysis, CR rate of BCLC 0 was 100%, and that of BCLC A was 97.9%. The reason that one patient belonged to BCLC A did not achieve CR was considered that tumors was close to portal vein. In addition, there were only minor complications in 10.8% patients. These data suggest that TACE combined with thermal ablation was safe and effective in the treatment of HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma, although this is an observational study without control.

It is reported that the long-term prognosis of HCV-related HCC is about 50% with the 5-year OS rate after curative treatment (13). Ren Y et al (9) analyzed 128 HCC patients mainly including HBV-HCC (85.2%) and showed the 1-, 3-, 5- and 8-year survival rates were 90.6%, 76.6%, 68.0%, 68.0%. In our study, after long-term follow-up, the 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, 5-year and 10-year cumulative OS rate were 94%, 78.3%, 72.3%, 43.4% and 27.5%, respectively, and the curative effect in first three years is similar to that reported in HBV-HCC. However, the long term outcome was poorer than that of HBV-HCC reported before. This finding may be attributed to different tumor characteristics or hepatocarcinogenesis between HCV-HCC and HBV-HCC (14, 15).

Previous studies have shown that liver function and field factors might play an important role in prognosis of patients with HCV-related HCC. Due to the subjective judgment of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, the CTP system was not accurate. Johnson et al. (16) established a novel and objective evaluation model for liver functional reserve assessment called ALBI grade composed of albumin and bilirubin. A number of retrospective studies further confirmed that ALBI grade can predict the prognosis patients with HCC after hepatectomy, liver transplantation, RFA or TACE (17–20). An C et al. (21) recruited 183 patients of HCV-related HCCs and constructed a nomogram which was based on ALBI grade and could provide prediction of long-term outcomes for HCV-related HCC patients after US-PMWA. In the current study, we also identified that ALBI grade determined prognosis for OS of patients with HCV-related HCC underwent thermal ablation combined with TACE. In addition, Univariate and multivariate analysis demonstrated that incomplete ablation of tumors and male were also independent unfavorable prognostic factors for poor OS. Among the 3 factors, incomplete ablation was the most important prognostic factor. Considered reasons of incomplete ablation, except for the fact that it is difficult to achieve CR for tumors close to the large vessels, it may be related to poor differentiation of tumor or microvascular invasion in some patients before therapy. It is suggested to enlarge the cohort and collect the pathological results. The decreased expression of estrogen receptor alfa (ERα) in male patients may explain the worse prognosis of HCV-related cirrhosis and HCC in men than in women (22).

Several studies showed that sustained virological response (SVR) is associated with the favorable long-term survival after curative resection or ablation (23, 24). However, in this study, HCV-RNA is not related to OS of patients after thermal ablation combined with TACE. We consider that there were only few cases (14/69) achieve virological response when antiviral therapy was applied.

The 1-year, 2-year, 3-year and 5-year RFS rates of patients in this study were 74.7%, 49.3%, 30.7% and 25.3%, respectively, similar to those previously reported (25). It is reported that, tumor‐related factors were risk factor for recurrence of HCC patients after curative treatment, such as AFP, tumor size, tumor number, pathological type, etc. (25–27). In this study, we identified only AFP levels and tumor number were associated with RFS probability in HCV-related HCC patients after thermal ablation combined with TACE. Tumor size was not risk factor for recurrence of HCC, probably because of the low proportion of patients with tumors larger than 3 cm (n=30, 36.14%).

There were some limitations in this study. First of all, this was a single-center and retrospective study, and we could not completely avoid referral bias. Second, this was a single-arm study. The effects of combined therapy on the survival of patients between HCV-related HCC and HBV-related HCC were not compared. Finally, the sample of this study is relatively small. Further prospective randomized controlled trials are necessary to validate our observations.

The data of our study indicated that percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE is an effective and safe ablation modality for patients with HCV-related HCC. Sex, ablation result and ALBI were independent prognostic factors for survival after percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE for HCC.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University affiliated Beijing Youan Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Conceived and designed the protocol: CY. Collected data: YS and JL. Wrote the manuscript: YS and HZ. Analyzed data: JZ and YZ. Critically revised and approved the final version of manuscript: CY. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study is supported by Capital Health Research and Development of Special Fund (No.2018-2-2182); Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (grant no. 7191004) and the Beijing Key Laboratory of Biomarkers for Infectious Diseases (grant no.BZ0373).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin (2018) 68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

2. El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology (2007) 132:2557–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061

3. Petruzziello A. Epidemiology of hepatitis b virus (HBV) and hepatitis c virus (HCV) related hepatocellular carcinoma. Open Virol J (2018) 12:26–32. doi: 10.2174/1874357901812010026

4. Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y

5. Parikh ND, Fu S, Rao H, Yang M, Li Y, Powell C, et al. Risk assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis c in China and the USA. Diges Dis Sci (2017) 62:3243–53. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4776-7

6. Song MJ, Bae SH, Lee JS, Lee SW, Song DS, You CR, et al. Combination transarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation therapy for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Internal Med (2016) 31:242–52. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.112

7. Zhou J, Sun HC, Wang Z, Cong WM, Wang JH, Zeng MS, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer in China (2017 edition). Liver Cancer (2018) 7:235–60. doi: 10.1159/000488035

8. Glassberg MB, Ghosh S, Clymer JW, Qadeer RA, Ferko NC, Sadeghirad B, et al. Microwave ablation compared with radiofrequency ablation for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther (2019) 12:6407–38. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S204340

9. Ren Y, Cao Y, Ma H, Kan X, Zhou C, Liu J, et al. Improved clinical outcome using transarterial chemoembolization combined with radiofrequency ablation for patients in Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage a or b hepatocellular carcinoma regardless of tumor size: Results of a single-center retrospective case control study. BMC Cancer (2019) 19:983. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6237-5

10. Tang C, Shen J, Feng W, Bao Y, Dong X, Dai Y, et al. Combination therapy of radiofrequency ablation and transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective study. Medicine (2016) 95:e3754. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003754

11. Peng Z-W, Zhang Y-J, Chen M-S, Xu L, Liang H-H, Lin X-J, et al. Radiofrequency ablation with or without transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31:426–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.9936

12. Darweesh SK, Gad AA. Percutaneous microwave ablation for HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Efficacy, safety, and survival. Turk J Gastroenterol: Off J Turk Soc Gastroenterol (2019) 30(5):445–53. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2019.17191

13. Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis (2005) 25:181–200. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871198

14. Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Cho J, Paik SW, Yoo BC. Comparison of clinical manifestations and outcomes between hepatitis b virus- and hepatitis c virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of a nationwide cohort. PloS One (2014) 9:e112184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112184

15. Sun S, Li Y, Han S, Jia H, Li X, Li X. A comprehensive genome-wide profiling comparison between HBV and HCV infected hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Med Genomics (2019) 12:147. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0580-x

16. Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2015) 33:550–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151

17. Oh IS, Sinn DH, Kang TW, Lee MW, Kang W, Gwak GY, et al. Liver function assessment using albumin-bilirubin grade for patients with very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radiofrequency ablation. Diges Dis Sci (2017) 62:3235–42. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4775-8

18. Ye L, Liang R, Zhang J, Chen C, Chen X, Zhang Y, et al. Postoperative albumin-bilirubin grade and albumin-bilirubin change predict the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Ann Trans Med (2019) 7:367. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.06.01

19. Kornberg A, Witt U, Schernhammer M, Kornberg J, Muller K, Friess H, et al. The role of preoperative albumin-bilirubin grade for oncological risk stratification in liver transplant patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol (2019) 120:1126–36. doi: 10.1002/jso.25721

20. Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Allara E, Yen C, Arizumi T, Kubota K, et al. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol (2017) 66:338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.008

21. An C, Li X, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, Liu F, et al. Nomogram based on albumin-bilirubin grade to predict outcome of the patients with hepatitis c virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after microwave ablation. Cancer Biol Med (2019) 16:797–810. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0486

22. Iyer JK, Kalra M, Kaul A, Payton ME, Kaul R. Estrogen receptor expression in chronic hepatitis c and hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol (2017) 23:6802–16. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6802

23. Cabibbo G, Celsa C, Calvaruso V, Petta S, Cacciola I, Cannavo MR, et al. Direct-acting antivirals after successful treatment of early hepatocellular carcinoma improve survival in HCV-cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol (2019) 71:265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.027

24. Ryu T, Takami Y, Wada Y, Tateishi M, Matsushima H, Yoshitomi M, et al. Effect of achieving sustained virological response before hepatitis c virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence on survival and recurrence after curative surgical microwave ablation. Hepatol Int (2018) 12:149–57. doi: 10.1007/s12072-018-9851-4

25. Nakano M, Koga H, Ide T, Kuromatsu R, Hashimoto S, Yatsuhashi H, et al. Predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence associated with the use of direct-acting antiviral agent therapy for hepatitis c virus after curative treatment: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Cancer Med (2019) 8:2646–53. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2061

26. Zheng L, Li HL, Guo CY, Luo SX. Comparison of the efficacy and prognostic factors of transarterial chemoembolization plus microwave ablation versus transarterial chemoembolization alone in patients with a Large solitary or multinodular hepatocellular carcinomas. Korean J Radiol (2018) 19:237–46. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.2.237

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, percutaneous thermal ablation, overall survival, recurrence, prognosis

Citation: Sun Y, Zhang H, Long J, Zhang Y, Zheng J and Yuan C (2022) Percutaneous thermal ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Efficacy and survival. Front. Oncol. 12:978614. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.978614

Received: 26 June 2022; Accepted: 05 September 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Hong-Tao Hu, Henan Provincial Cancer Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Rui Liao, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Sun, Zhang, Long, Zhang, Zheng and Yuan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunwang Yuan, eXVhbmN3QGNjbXUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.