94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Oncol., 22 July 2022

Sec. Gastrointestinal Cancers: Hepato Pancreatic Biliary Cancers

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.948293

Hiroyuki Suzuki1

Hiroyuki Suzuki1 Hideki Iwamoto1,2*

Hideki Iwamoto1,2* Shigeo Shimose1

Shigeo Shimose1 Takashi Niizeki1

Takashi Niizeki1 Tomotake Shirono1

Tomotake Shirono1 Yu Noda1

Yu Noda1 Naoki Kamachi1

Naoki Kamachi1 Taizo Yamaguchi2

Taizo Yamaguchi2 Masahito Nakano1

Masahito Nakano1 Ryoko Kuromatsu1

Ryoko Kuromatsu1 Hironori Koga1

Hironori Koga1 Takumi Kawaguchi1

Takumi Kawaguchi1Recently, a combined regimen of atezolizumab and bevacizumab (AB) treatment has been approved as a first-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), contributing to prolonged survival. However, we often encounter cases where treatment must be discontinued due to the occurrence of adverse events. One of these events, which is often fatal, is gastrointestinal bleeding. To clarify the clinical effects of gastrointestinal bleeding after AB treatment, we evaluated patients with HCC who were treated with AB at our institution. Of the 105 patients, five treated with AB developed gastrointestinal bleeding, necessitating treatment discontinuation. Additionally, we encountered two cases where exacerbation of varicose veins was observed, and AB therapy could be continued by preventive treatment of varices. In conclusion, an appropriate follow-up is required during treatment with AB to prevent possible exacerbation of varicose veins.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequently occurring primary liver malignancy and a major cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). It typically occurs in patients with persistent hepatitis or cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B or C virus infection, excessive alcohol consumption, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (2, 3). Although advances in diagnosis have contributed to a reduced risk of developing HCC, this malignancy is often diagnosed in advanced stages (4). Recently, systemic therapy for advanced HCC has achieved remarkable progress, and various molecular targeted agents (MTAs), primarily inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling, have been approved (3). In the past few years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which target tumor immunity, have caused a paradigm shift in the treatment of advanced HCC (3). Patients with HCC having liver cirrhosis, particularly decompensated liver cirrhosis, often experience complications, such as varicose veins, associated with portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome (5, 6). Treatment of advanced stages of HCC involving MTAs and ICIs, often aggravates these complications, rendering treatment continuation difficult (3). Therefore, a comprehensive follow-up prevents the exacerbation of these complications is required.

A combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab (AB) has been recently approved as a first-line treatment in patients with advanced HCC, as it shows superiority to sorafenib in terms of survival benefits (7). However, information regarding potential predictors of response, resistance, and toxicity of immunotherapy for HCC is very limited, therefore, clarifying these indicators is of pivotal importance when using this combination therapy in a clinical setting (8–10). Even after excluding patients at high risk for bleeding, approximately 10% of the patients in the study experienced bleeding during AB treatment, and 6%–10% of them developed > grade 3 hemorrhage (7, 11). In such circumstances, HCC treatment has to be discontinued to stop the bleeding, favoring HCC progression. Therefore, elucidating the clinical features of gastrointestinal bleeding due to AB treatment is imperative.

Herein, we present a case series and literature review of exacerbated varices and/or gastrointestinal bleeding during AB combination treatment.

In this study, we evaluated 105 patients with advanced HCC who received AB treatment between January 2020 and December 2021 at our institute (Kurume University Hospital and Iwamoto Internal Medicine Clinic). Endoscopic evaluation was not performed in cases where collateral blood vessels were not found on computed tomography or other modalities or when patients had chronic hepatitis instead of cirrhosis, as indicated by clinical evaluation. Out of 105 patients, 85 of them underwent endoscopic evaluation for varices prior to AB treatment. To assess splenomegaly, we calculated the splenic index based on the formula (craniocaudal dimension × width × thickness) and defined patients with splenomegaly as having a splenic index > 480 (12).

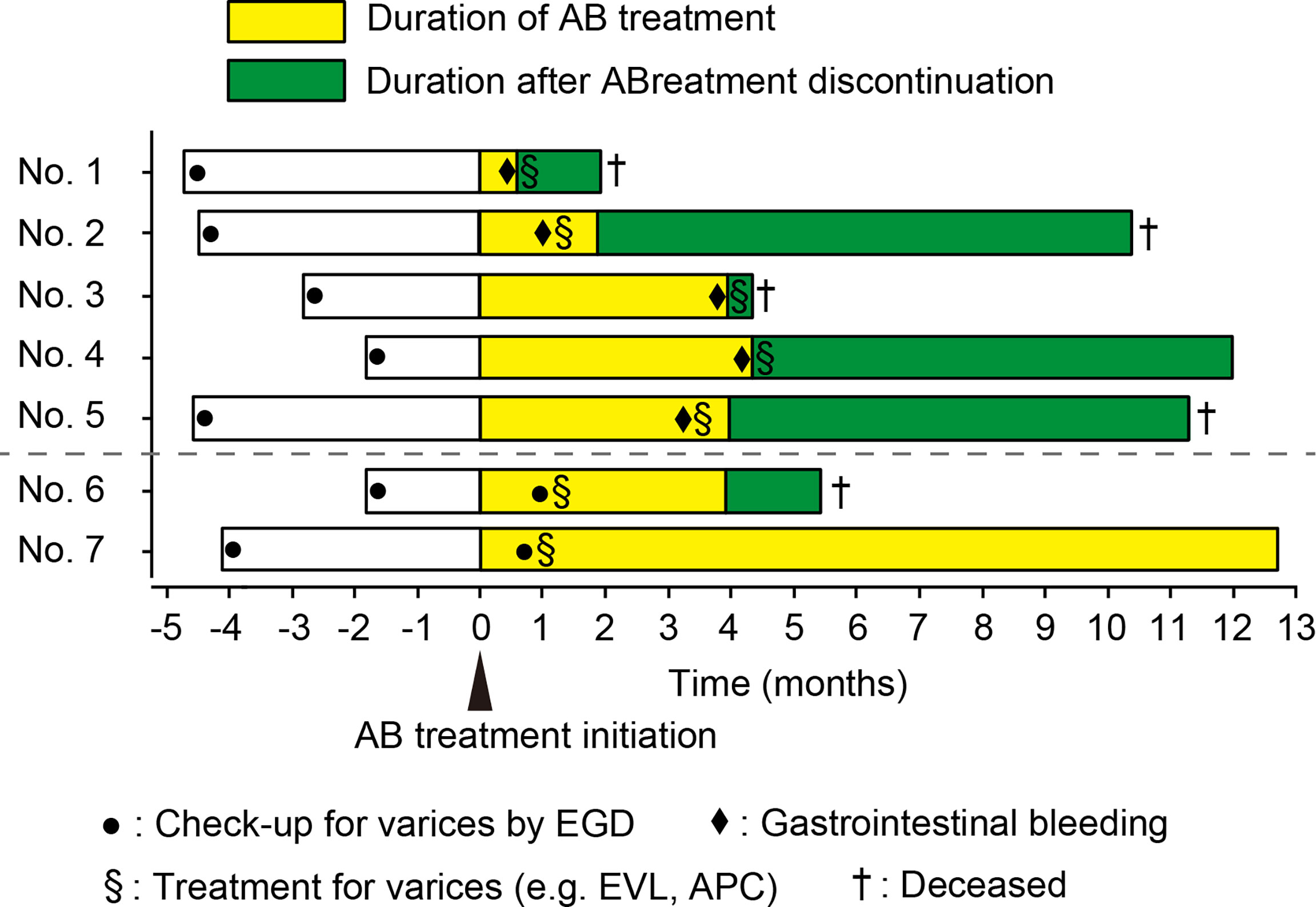

Of the 85 patients who underwent endoscopic evaluation prior to AB treatment, 12 had form 1 of varicose veins. In 55 patients, follow-up endoscopy could not be performed after initiation of the treatment due to deterioration of general condition, progression of HCC, or lack of scheduled endoscopic follow-up. Thirty patients underwent follow-up endoscopy after AB treatment. Out of the 105 patients, 4.8% (5/105) developed gastrointestinal bleeding as an adverse event (AE) and 1.9% (2/105) had rapid exacerbated varices during AB therapy. Patient characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 1. The clinical course of patients is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Swimmer plot for all cases. AB, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation; APC, argon plasma coagulation. EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

In the following five cases, bleeding was observed 76.8 (range: 18–132) days after initiation of AB treatment.

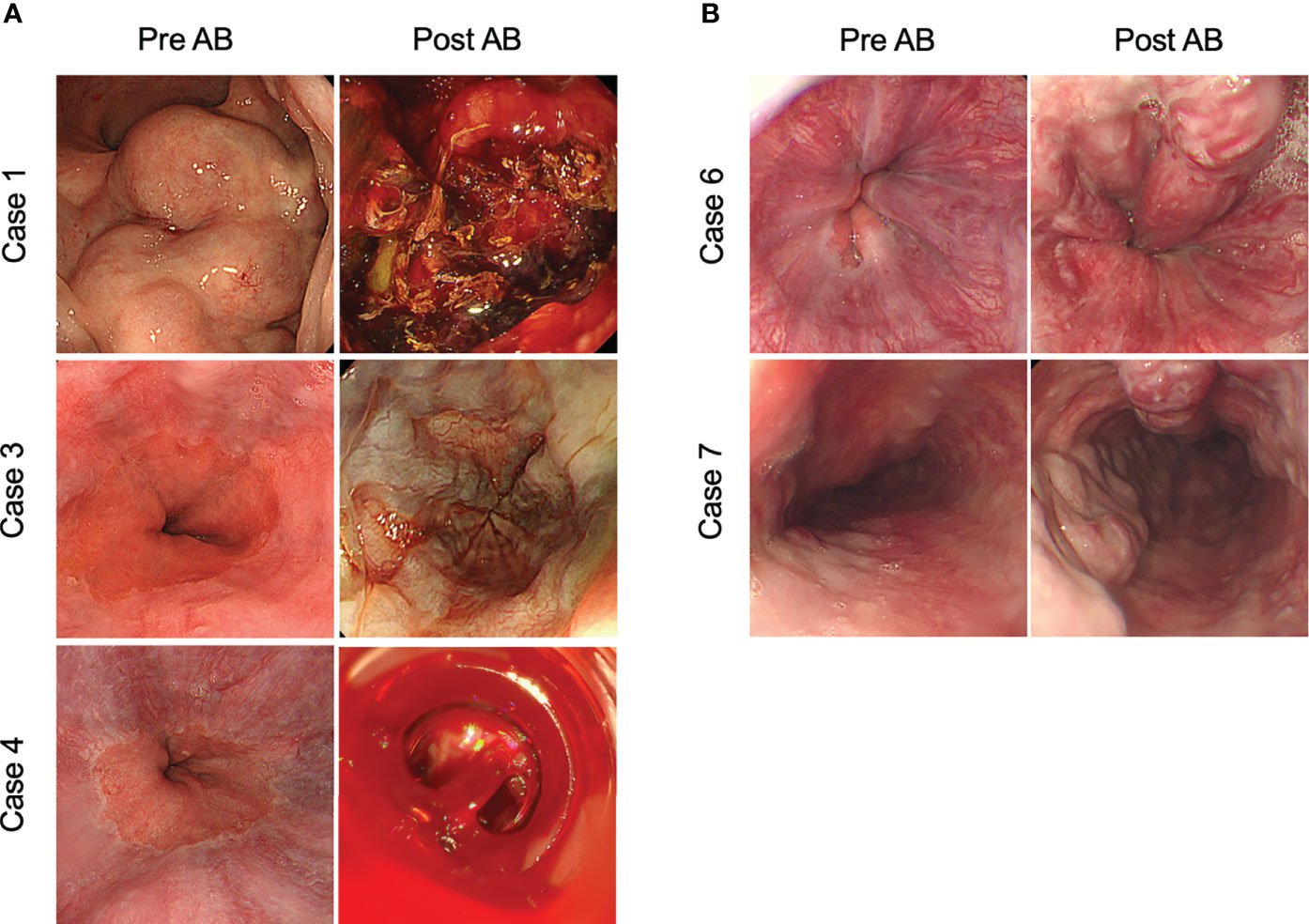

A 70-year-old Japanese man with stage IVB HCC with lung metastasis was treated with AB. He had splenomegaly and developed collateral circulation in the inferior vena cava. Seventeen days after treatment initiation, a large blood volume was observed in the patient’s stool. Colonoscopy revealed hemorrhage from the rectal varicose vein, which was detected as grade III form of varices, and the red color sign was negative before treatment (Figure 2A). Immediate endoscopic treatment, including endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, was performed. However, the hemostatic effect was poor, leading to cardiopulmonary arrest. Bleeding continued, and the patient eventually died 39 days after the occurrence of the first bleeding event.

Figure 2 Representative images of gastrointestinal bleeding and exacerbation of varicose veins after atezolizumab plus bevacizumab treatment. (A) Patients that developed gastrointestinal bleeding after treatment with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. (B) Patients in which varices exacerbated during atezolizumab plus bevacizumab treatment. AB, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab treatment.

A 78-year-old Japanese man with unresectable HCC (stage III) was treated with AB. Two weeks after treatment initiation, the patient developed melena and grade 3 liver dysfunction. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed bleeding from the esophageal varices, detected as Li F1 Cb RC(-) before treatment. EVL was performed immediately, and hemostasis was achieved. Although endoscopic findings 1 month after varicose vein treatment indicated only esophageal varicose vein [Li F1 Cb RC(-)], the AB therapy was discontinued due to the event of bleeding from esophageal varices. Eventually, due to HCC progression, the patient died 9 months after the varicose vein ruptured.

A 61-year-old Japanese man with stage IVB HCC with lung metastasis was treated with AB. After three cycles of AB treatment, computed tomography demonstrated stable disease condition according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Four cycles after treatment initiation, the patient experienced hematemesis and was admitted to our hospital. EGD revealed bleeding from esophageal varices, detected as Lm F1 Cb RC(-) before treatment. EVL was immediately performed, and temporary hemostasis was achieved. However, his liver function and general condition rapidly deteriorated after the varix rupture, and then the patient died 10 days after the event. (Figure 2A).

A 55-year-old Japanese man with stage IVB HCC with bone metastasis was treated with AB. Four months after treatment initiation, the patient experienced hematemesis and was admitted to the hospital. EGD revealed hemorrhage from the esophageal varices, detected as Li F1 Cb RC(-) before treatment (Figure 2A). EVL was immediately performed, and hemostasis was achieved; however, AB treatment was discontinued. Subsequent endoscopy showed no apparent exacerbation of varicose veins. The patient is alive and is being treated with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for HCC.

A 69-year-old Japanese man with unresectable HCC (stage III) was treated with AB. After three courses of AB treatment, computed tomography demonstrated a partial response to treatment, according to the RECIST ver.1.1. Five cycles after treatment initiation, the patient presented with hematemesis and was admitted to our hospital. EGD revealed bleeding from the esophageal varices, detected as Li F1 Cb RC(-) before treatment. EVL was immediately performed, and hemostasis was achieved. Endoscopic findings 1 month after varicose vein treatment showed only esophageal varices [Li F1 Cb RC(-)]. However, the AB therapy was discontinued due to the event of bleeding from esophageal varices. Thereafter, atezolizumab monotherapy was initiated in accordance with the patient’s wishes. Eventually, due to HCC progression, the patient died 7 months after the varicose vein ruptured.

A 37-year-old Japanese man with stage IVB HCC with peritoneal dissemination was treated with AB combination therapy. EGD performed 4 weeks after treatment revealed worsened esophageal varices [Li F3 Cb RC(-)], detected as Li F1 Cb RC(-) before AB treatment initiation (Figure 2B). Thereafter, EVL was performed to prevent bleeding. Due to the progression of HCC, the patient died 5 months after the initiation of combined AB treatment.

A 72-year-old Japanese man with unresectable HCC (stage III) received AB treatment. EGD performed 3 weeks after treatment initiation revealed rapidly exacerbated esophageal varices [Li F3 Cb RC(-)], detected as Li F1 Cb RC(-) prior to the initiation of AB treatment (Figure 2B). EVL and argon plasma coagulation were performed to prevent bleeding. After three courses of combination treatment, enhanced computed tomography demonstrated a partial response to treatment according to the RECIST ver.1.1. Subsequently, the combination therapy with AB was continued for more than 12 months.

In this study, we described the clinical features of gastrointestinal bleeding during AB treatment in patients with advanced HCC. Five patients experienced gastrointestinal bleeding. The prevalence of gastrointestinal bleeding in the current study (4.8%) was similar to that in a previous clinical trial (7). To the best of our knowledge, two cases of rapid growth of esophageal varices following AB have been reported (13). Table 1 shows the characteristics of those patients and that of the patients in the present study. It has been reported that once gastrointestinal bleeding occurs, combination treatment continuation will be difficult in most cases for the following reasons: rapid deterioration in liver function, rapid growth of HCC, and acquired resistance against AB treatment (11, 14). Similarly, all patients in our study who developed gastrointestinal bleeding could not continue AB treatment and experienced HCC progression after treatment discontinuation. However, two patients in whom preventive treatment for varicose veins was possible, AB treatment could be continued for a longer period. Therefore, to continue treatment without gastrointestinal bleeding occurrence, appropriate follow-up and intervention for varicose veins at the right time are of utmost importance. Elective treatment modalities for non-bleeding varices, such as EVL and APC, are invasive. Therefore, it is important to consider the delayed wound healing effect of bevacizumab, which could induce varicose vein rupture after the treatment. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology ver. 2.2022 (15), 4–6 weeks of intermission from the last administration of bevacizumab is recommended for surgical treatment. Therefore, if possible, we recommend that elective treatments should be performed 4–6 weeks after the last administration of bevacizumab for non-urgent cases.

It has been shown that HCC developed in the context of chronic hepatitis/cirrhosis (2, 3). Cirrhosis is closely associated with portal hypertension and has a very high risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to the development of collateral circulation (16). Although the liver function of all patients in our report and a previous report (17) was well preserved (Child-Pugh score ≤ 7), splenomegaly was observed in most of the patients. It is suggested that all of them had potential portal hypertension. Consequently, it seems that there might be no association between the severity of liver cirrhosis and worsening of varicose vein or bleeding. Portal vein tumor thrombosis has been recognized to increase portal pressure, leading to exacerbation of varicose veins (17). However, portal vein tumor thrombosis was not identified in these cases.

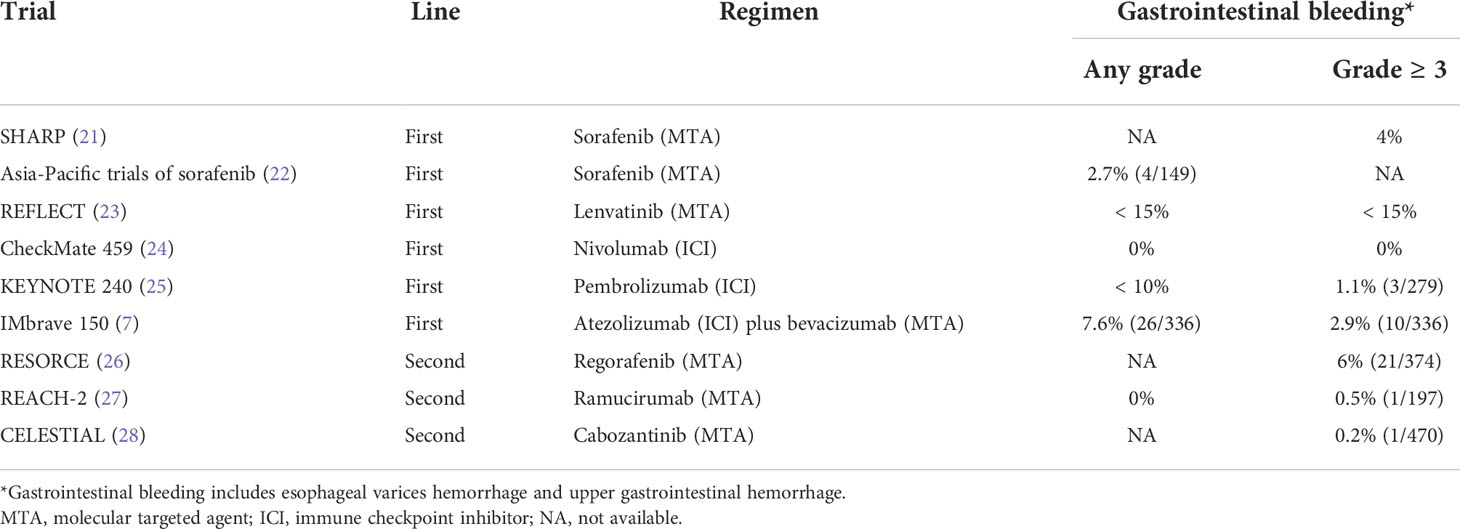

ICIs are monoclonal antibodies that target immune checkpoint molecules (18, 19). Since these drugs directly regulate the immune system, immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events (irAEs), mainly due to immune dysregulation, are often problematic in clinical practice (18, 19). Colitis and diarrhea are the most common irAEs in the gastrointestinal system. However, the frequency of irAEs in the upper gastrointestinal tract is low, the most common of which is nausea and loss of appetite (20). Thus, the association between gastrointestinal bleeding observed in this study and immune checkpoint inhibitors was considered low. As shown in the incidence rate of bleeding in the clinical trials summarized in Table 2, the incidence of bleeding with immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy is relatively low.

Table 2 The incidence rate of gastrointestinal bleeding in reported clinical trials of systemic chemotherapy for advanced HCC.

Many types of MTA have been approved as systemic chemotherapy for patients with advanced HCC and have provided survival benefits (29, 30). In previous trials, it has been reported that 0%–7.6% of the patients with HCC developed bleeding during MTA treatment (Table 2) (7, 21–28). Most MTAs commonly exert their antitumor effects by inhibiting VEGF signaling. We have previously reported that MTAs inhibit angiogenesis via VEGF signaling not only in tumor micro vessels, but also in normal organs, such as the liver, pituitary gland, kidneys, and intestine, leading to the occurrence of various AEs (31). Moreover, the association between the use of anti-VEGF antibody and AEs of hemorrhage has been elucidated, and it comprises of the following: (i) poor vasodilation due to inhibition of nitric oxide, which has a vasodilatory effect, and (ii) reduction in capillary bed density (32). Inhibition of VEGF, which is responsible for the homeostasis of micro vessels, leads to a decrease in capillary bed density in the liver and an increase in pressure in the reticuloendothelial system, resulting in worsened varicose veins. To evaluate whether the amount of vascular bed in the liver was associated with varicose vein exacerbation, we looked for correlation between presence or absence of hepatectomy and varicose vein exacerbation. However, half of the patients had a history of resection with no significant findings. We also evaluated the correlation between the use of MTA for pretreatment and exacerbation of varicose veins. Nevertheless, only three patients had MTA as a history of pretreatment, and no significant findings were found.

Bevacizumab is recommended at a dose range of 5–15 mg/kg every 2–3 weeks, depending on the type of tumor and combination therapy (7, 33). For HCC, the recommended dosage of bevacizumab is 15 mg/kg after intravenous administration of 1200 mg of atezolizumab on the same day, every 3 weeks (7). At present, a method for reducing the dose of bevacizumab has not been established, and it is contraindicated to restart bevacizumab after it has caused gastrointestinal bleeding. Unfortunately, in cases where AB therapy has to be discontinued due to gastrointestinal bleeding, alternative HCC treatment strategies are limited. They include (1) atezolizumab monotherapy, as executed in Case 5 in this report, although it may have limited efficacy (7); (2) treatment with MTAs (ramucirumab, cabozantinib) since they are associated with a relatively low frequency of gastrointestinal bleeding as shown in Table 2; however, since these drugs commonly have anti-angiogenesis effect via VEGF signaling inhibition, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding persists; (3) ICI plus ICI combination therapy, which is currently being evaluated in clinical trials (durvalumab plus tremelimumab, NCT03298451; ipilimumab plus nivolumab, NCT04039607), could be possible treatment options in the future. We have previously reported that in patients with advanced HCC who discontinued treatment due to AE after MTA administration, it might be possible to increase the antitumor effect while reducing the incidence of AE using the weekends-off administration method (31). Therefore, it is necessary to establish optimal methods for reducing bevacizumab dosage in cases where severe gastrointestinal bleeding could develop. In this report, gastrointestinal bleeding occurred at an average of 76.8 days after AB treatment initiation in five cases. In addition, in the two cases of varicose vein exacerbation, varicose veins worsened to the extent of requiring treatment 1 month after initiation of AB treatment. Based on these findings, it is necessary to evaluate varicose veins not only before AB treatment initiation but also early after its initiation. Regular follow-up every 3–6 months might be necessary, especially in patients at high risk for varicose vein rupture.

AB treatment of advanced HCC might exacerbate varicose veins. However, appropriate prevention and treatment of varicose veins can contribute to prolonging the treatment duration.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HS and HI wrote the manuscript. SS, TN, TS, YN, NK, and TY participated in the acquisition of data and critical revision. RK, HK, and TK supervised the study. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor TK declared a shared Research Group Japanese Society of Hepatology with the author(s) at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank the patients and their families for their involvement in the study.

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology (2007) 132(7):2557–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061

3. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers (2021) 7(1):6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

4. Grandhi MS, Kim AK, Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Kamel IR, Ghasebeh MA, Pawlik TM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: From diagnosis to treatment. Surg Oncol (2016) 25:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2016.03.002

5. Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet (2008) 371(9615):838–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9

6. Allaire M, Rudler M, Thabut D. Portal hypertension and hepatocellular carcinoma: Des liaisons dangereuses. Liver Int (2021) 41(8):1734–43. doi: 10.1111/liv.14977

7. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Investigators: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2020) 382(20):1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

8. Rizzo A, Ricci AD. PD-L1, TMB, and other potential predictors of response to immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: how can they assist drug clinical trials? Expert Opin Investig Drugs (2022) 31(4):415–23. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.1972969

9. Rizzo A, Brandi G. Biochemical predictors of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Treat Res Commun (2021) 27:100328. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100328

10. Lorenzo SD, Tovoli F, Barbera MA, Garuti F, Palloni A, Frega G, et al. Metronomic capecitabine vs. best supportive care in child-pugh b hepatocellular carcinoma: a proof of concept. Sci Rep (2018) 8:9997. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28337-6

11. Liu X, Lu Y, Qin S. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab for hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanism, pharmacokinetics and future treatment strategies. Future Oncol (2021) 17(17):2243–56. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-1290

12. Indiran V, Vinod Singh N, Ramachandra Prasad T, Maduraimuthu P. Does coronal oblique length of spleen on CT reflect splenic index? Abdom Radiol (NY) (2017) 42(5):1444–8. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1055-1

13. Furusawa A, Naganuma A, Suzuki Y, Hoshino T, Yasuoka H, Tamura Y, et al. Two cases of rapid progression of esophageal varices after atezolizumab-bevacizumab treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol (2022) 15(2):451–9. doi: 10.1007/s12328-022-01605-9

14. Tang W, Chen Z, Zhang W, Cheng Y, Zhang B, Wu F, et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2020) 5(1):87. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0187-x

15. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain MA, Chen Y-J, Ciombor KK, et al. Colon cancer, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2021) 19(3):329–59. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012

16. Iwakiri Y. Pathophysiology of portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis (2014) 18(2):281–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2013.12.001

17. Iavarone M, Primignani M, Vavassori S, Sangiovanni A, La Mura V, Romeo R, et al. Determinants of esophageal varices bleeding in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. United Eur Gastroenterol J (2016) 4(3):363–70. doi: 10.1177/2050640615615041

18. Cramer P, Bresalier RS. Gastrointestinal and hepatic complications of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep (2017) 19(1):3. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0540-6

19. Shivaji UN, Jeffery L, Gui X, Smith SCL, Ahmad OF, Akbar A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated gastrointestinal and hepatic adverse events and their management. Therap Adv Gastroenterol (2019) 12:1756284819884196. doi: 10.1177/1756284819884196

20. Ahmed M. Checkpoint inhibitors: What gastroenterologists need to know. World J Gastroenterol (2018) 24(48):5433–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i48.5433

21. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2008) 359(4):378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

22. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol (2009) 10(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7

23. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet (2018) 391(10126):1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1

24. Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Mathurin P, Edeline J, et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2022) 23(1):77–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00604-5

25. Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim HY, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38(3):193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307

26. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet (2017) 389(10064):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9

27. Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2019) 20(2):282–96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9

28. Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2018) 379(1):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002

29. Kudo M. Impact of multi-drug sequential therapy on survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer (2021) 10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000514194

30. Iwamoto H, Shimose S, Noda Y, Shirono T, Niizeki T, Nakano M, et al. Initial experience of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world clinical practice. Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13(11):2786. doi: 10.3390/cancers13112786

31. Iwamoto H, Suzuki H, Shimose S, Niizeki T, Nakano M, Shirono T, et al. Weekends-off lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma improves therapeutic response and tolerability toward adverse events. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12(4):1010. doi: 10.3390/cancers12041010

32. Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer (2007) 96(12):1788–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603813

Keywords: atezolizumab, bevacizumab, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, portal hypertension, varices

Citation: Suzuki H, Iwamoto H, Shimose S, Niizeki T, Shirono T, Noda Y, Kamachi N, Yamaguchi T, Nakano M, Kuromatsu R, Koga H and Kawaguchi T (2022) Case Report: Exacerbation of varices following atezolizumab plus bevacizumab treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A case series and literature review. Front. Oncol. 12:948293. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.948293

Received: 19 May 2022; Accepted: 28 June 2022;

Published: 22 July 2022.

Edited by:

Takahiro Kodama, Osaka University, JapanReviewed by:

Satoru Kakizaki, Gunma University, JapanCopyright © 2022 Suzuki, Iwamoto, Shimose, Niizeki, Shirono, Noda, Kamachi, Yamaguchi, Nakano, Kuromatsu, Koga and Kawaguchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hideki Iwamoto, aXdhbW90b19oaWRla2lAbWVkLmt1cnVtZS11LmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.