- 1Oncology Operative Unit, “Santa Maria delle Grazie” Hospital, ASL Napoli 2 NORD–, Pozzuoli, Italy

- 2Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Napoli, Italy

- 3CEINGE Biotecnologie Avanzate scarl, Napoli, Italy

- 4Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnologies, University of Naples “Federico II”, Napoli, Italy

- 5SEMM-European School of Molecular Medicine, Milano, Italy

- 6Institute of Experimental Endocrinology and Oncology, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Napoli, Italy

- 7BIOGEM, Ariano Irpino, Italy

Glioblastomas are the most frequent and malignant brain tumor hallmarked by an invariably poor prognosis. They have been classically differentiated into primary isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 (IDH1 -2) wild-type (wt) glioblastoma (GBM) and secondary IDH mutant GBM, with IDH wt GBMs being commonly associated with older age and poor prognosis. Recently, genetic analyses have been integrated with epigenetic investigations, strongly implementing typing and subtyping of brain tumors, including GBMs, and leading to the new WHO 2021 classification. GBM genomic and epigenomic profile influences evolution, resistance, and therapeutic responses. However, differently from other tumors, there is a wide gap between the refined GBM profiling and the limited therapeutic opportunities. In addition, the different oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes involved in glial cell transformation, the heterogeneous nature of cancer, and the restricted access of drugs due to the blood–brain barrier have limited clinical advancements. This review will summarize the more relevant genetic alterations found in GBMs and highlight their potential role as potential therapeutic targets.

Introduction

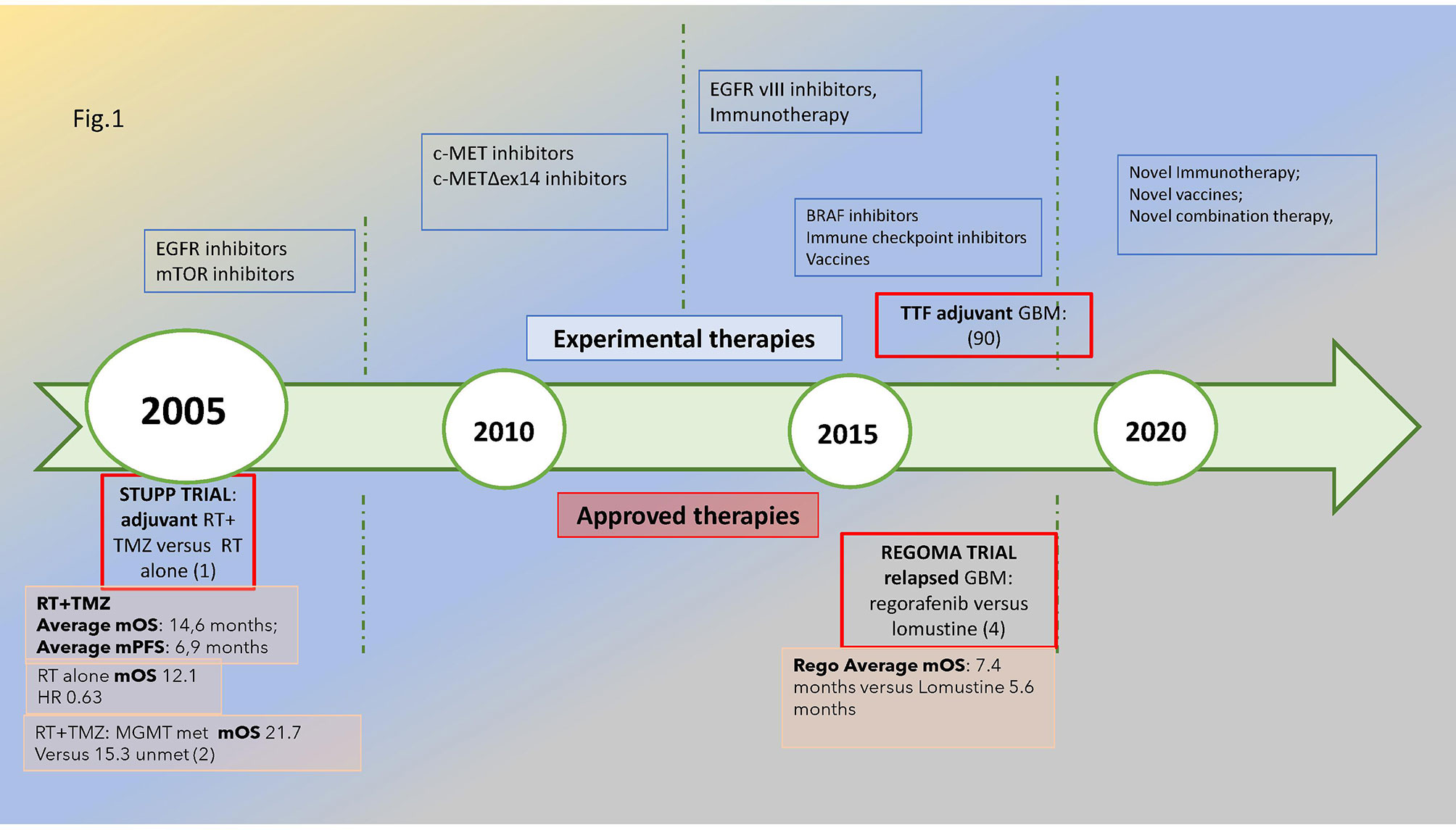

The most common malignant primitive tumor of the central nervous system, glioblastoma (GBM), shows some distinctive features: WHO grade IV—it is uniquely classified as “metastatic” even if it remains limited within the brain. As it is different from most kinds of cancers, oncological research faces an uphill struggle to find therapeutic significant advancements which are scarce since the 2005 STUPP pivotal trial (1, 2). The prognosis remains poor: 12–18 months median overall survival and 5% alive at 5 years (3). As shown in Figure 1, the timeline of glioblastoma treatments emphasized the lack of significant medical progress: a wait of 14 years after STUPP to find an improvement in survival in relapsed glioblastoma with regorafenib (4) and a wide array of novel treatments under investigation.

Figure 1 Glioblastoma’s treatment timeline: in the upper part of the figure, the novel treatments under investigation are reported, while in the lower part are the approved treatments in the adjuvant and relapsed phases with a reported significant improvement in survival, i.e., STUPP and REGOMA trial, respectively, dated 2005 and 2019. The median overall survival for the experimental and control arms is also reported. The methylation of MGMT promoter is associated with improved survival compared with unmethylated subtypes. Met, methylated; unmet, unmethylated.

Pathological classification appears to be substantially surpassed by molecular classification since 2016 and increasingly in the new WHO 2021 edition (5). Alteration of specific GBM markers, including the O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) overexpression, co-deletion of 1p and 19q, mutation in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) as well as telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (TERT) promoter, along with epigenome analysis not only underline the novel nomenclature but have a prognostic value and may guide treatment decisions. However, these molecular signatures do not automatically merge into precision medicine applications of immediate practical value, thus determining a certain discouragement towards analyses that requires high time and costs, with limited practical relevance.

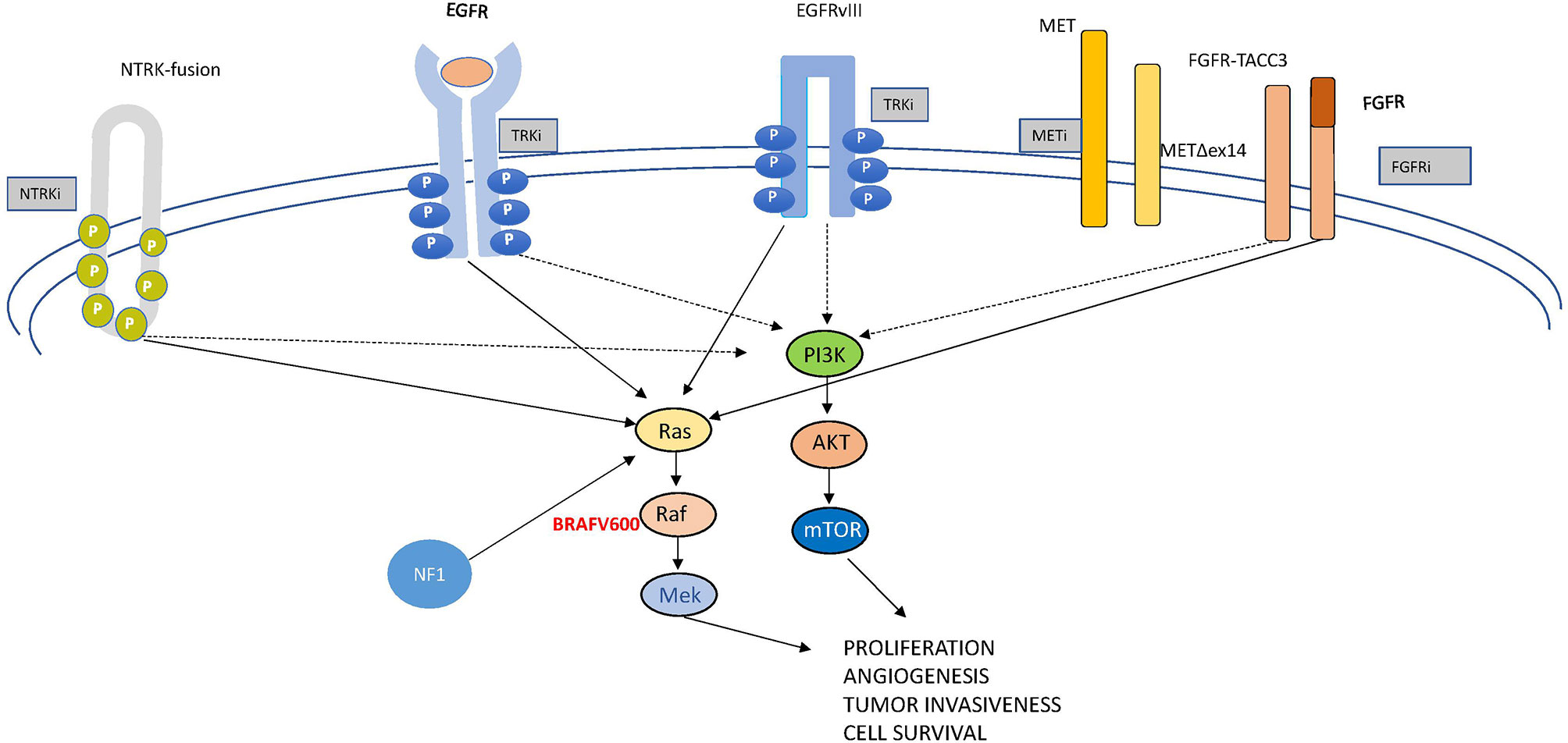

In this review, we examine the most relevant molecular drivers of GBM which are comprehensively depicted in Figure 2, both from a molecular and a clinical point of view, being aware that we are far from really-practice-changing interventions but still in the world of “one, no one, and one hundred thousand”. Like this drama, glioblastoma represents a complex conundrum. Following the track of other Pirandello’s plays, we gave a title to each paragraph that calls to mind uncertainty, investigation (a player in search of an author, either of one or of no one), high expectations (the lord of the ship), what is unexpected but in some cases may be a turning point (the turn), the relationship with other signaling (the rules of the game), and an undefined identity (each on its own way). Through this walk into the challenging glioblastoma land, we will provide some insights into the complex genomics looking to the progress with desirable clinical relevance.

Targeting TERT: A Player in Search of an Author

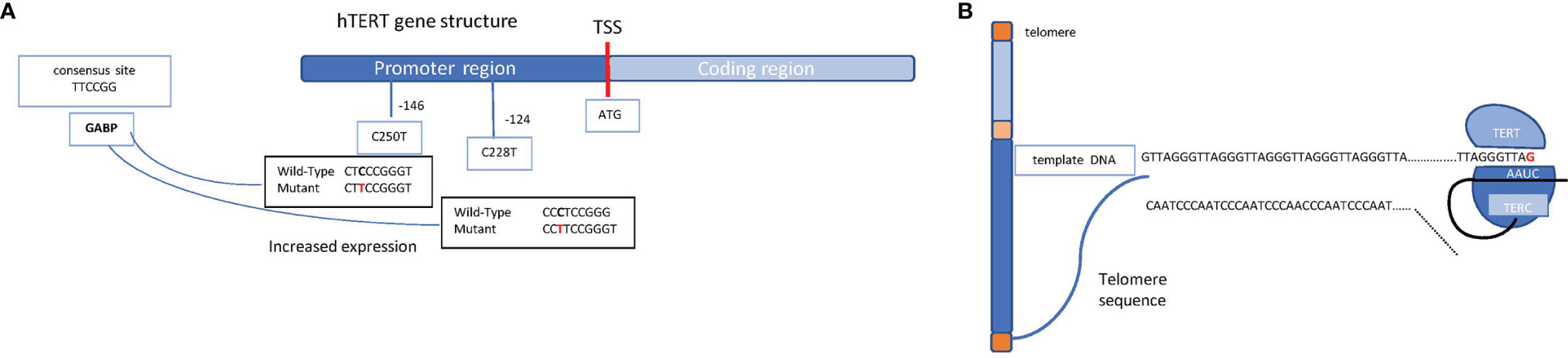

At each cell division, telomeres become shorter; however, a specialized enzyme called telomerase provides the chromosome tips of additional DNA. Telomerase is a reverse transcriptase ribonucleoprotein enzyme coded by the TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) gene that copies the template RNA named telomerase RNA component (TERC) (Figure 3A). Telomerase critically ensures chromosome length and genomic stability during cell replication, with telomerase defects being, accordingly, associated with senescence and cellular death (6). Conversely, some mutations in the TERT promoter are oncogenic, resulting in cell immortalization and transformation. These mutations, firstly discovered in melanoma, include frequent cytidine-to-thymidine conversion and have been found at two genetic regions upstream of the transcriptional start site, specifically c.-124C>T and c.-146C>T (7) (Figure 3B). A low rate of self-renewal in GBM histological samples has been correlated to high TERT expression in various cancer types, including melanomas, primary GBMs, liposarcomas, and hepatocellular carcinomas among others (8).

Figure 3 Schematic representation of the hTERT gene structure and the telomerase complex. (A) Schematic mechanism of a chromosome (telomeres in orange, short arm in light blue, long arm in blue, and centromere in yellow) and the molecular mechanism through which TERT enzyme, supported by TERC, ensure the telomere length. (B) hTERT gene promoter region (in blue) and coding region (in light blue) are shown. The transcription start site (TSS) is indicated as a red bar; on the promoter region, the most common mutations which lead to an increased expression of the gene are shown (the indicated positions refer to the TSS). Shown on the left, in the light blue box, is the consensus sequence which takes place because of the single mutation, allowing the binding of the transcription factor GABP on the promoter.

Mutations in the TERT promoter result in the generation of a novel binding site for the transcription factor GABP that, in turn, triggers TERT overexpression. Intriguingly, TERT mutations have been identified in about 80% of IDH wild-type GBMs and in 30% of IDH mutant GBMs, correlating with poor prognosis (9). These mutations may confer an increased benefit to temozolomide in MGMT-methylated GBMs (10, 11).

The role of TERT mutations in cell transformation and tumor aggressiveness has been documented in several preclinical studies. However, the number of available antitelomerase drugs is currently low, and only imetelstat (GRN163L) has entered in clinical practice. Imetelstat is a competitive inhibitor of TERT that acts by hindering the binding of telomerase to DNA (12). Interestingly, in GBM, imetelstat has been shown to reduce cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, the drug was observed to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and reduce tumor growth in tumor-engrafted mice (13). In addition, the association of imetelstat with classical radiotherapy and temozolomide drastically reduced GBM tumor growth in vitro and in pre-clinical studies (12). However, despite the promising results obtained, clinical trials have failed to prove imetelstat as effective on human solid tumors, probably because of the poor permeation of the drug into tumor tissues and for critical effects, such as several intracranial hemorrhages in phase II trial NCT01836549 (14). To date, imetelstat remains under investigation only in a phase III study for myelofibrosis cure (14). Although pharmacological research is currently oriented to improve the pharmacological characteristics of imetelstat, new strategies targeting the enzymatic activity of TERT are being developed. The small molecule -6-thio-2′- deoxyguanosine, whose metabolite is preferentially incorporated into telomeres, changes DNA structure and inhibits transcription factor binding. This compound is actively tested in preclinical studies (15) and is under investigation in a phase II study involving patients with non-small cell lung cancer at late disease stages. Eribulin has also been shown to effectively inhibit TERT activity in GBM cells (16, 17); however, its development has been stopped early.

Other approaches to target telomerase include antisense oligonucleotides, small-molecule inhibitors targeting TERT or TERC, such as BIBR1532 (18), and vaccines including UCPVax and INO-5401. UCPVax has been investigated in a phase I/II clinical trial (NCT04280848) (14). It is a universal vaccine designed by employing small portions of telomerase peptides to induce strong TH1 CD4 T cell responses in oncological patients (NCT02818426) (14). Differently, INO-5401 uses a combination of three separated DNA plasmids to co-target the Wilms tumor gene-1 (WT1) antigen, prostate-specific membrane antigen, and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) genes. It is currently in phase I/II clinical trials for newly diagnosed GBM patients together with INO-9012, which employs a DNA vector to overexpress human interleukin-12 (IL-12), and cemiplimab (NCT03491683) (14). This study is in an active—but not recruiting—phase, with June 2022 as the estimated date of completion.

To summarize, many clinical trials targeting TERT have not been concluded yet. Thus, its role in GBM treatment plan is still undecided. TERT is still “a character in search of an author”.

Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Their Downstream Pathways

Targeting receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are transmembrane-spanning receptors that, following ligand binding, undergo homo- or heterodimerization, leading to intracellular kinase domain activation and induction of a variety of downstream signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MAPK. RTK activation enhances tumor progression and survival as well as metastatic potential and angiogenesis.

The Lord of the Ship: EGFR

Among all oncogenic pathways, epidermal growth factor signaling has the right credentials to be considered the driver of GBM tumorigenesis (19).

EGFR is part of the transmembrane HER receptor family which also includes HER2/neu, HER3, and HER4 and is located on chromosome band 7p12. More than 40 EGFR high- and low-affinity ligands are recognized (20). Frequently, classical and mesenchymal GBMs are characterized by chromosome 7 gains with amplification of EGFR (21). The amplification can be graded into low/moderate and high ratio between EGFR and chromosome 7 with a significant correlation with survival, which was worse in the highly amplified group (22).

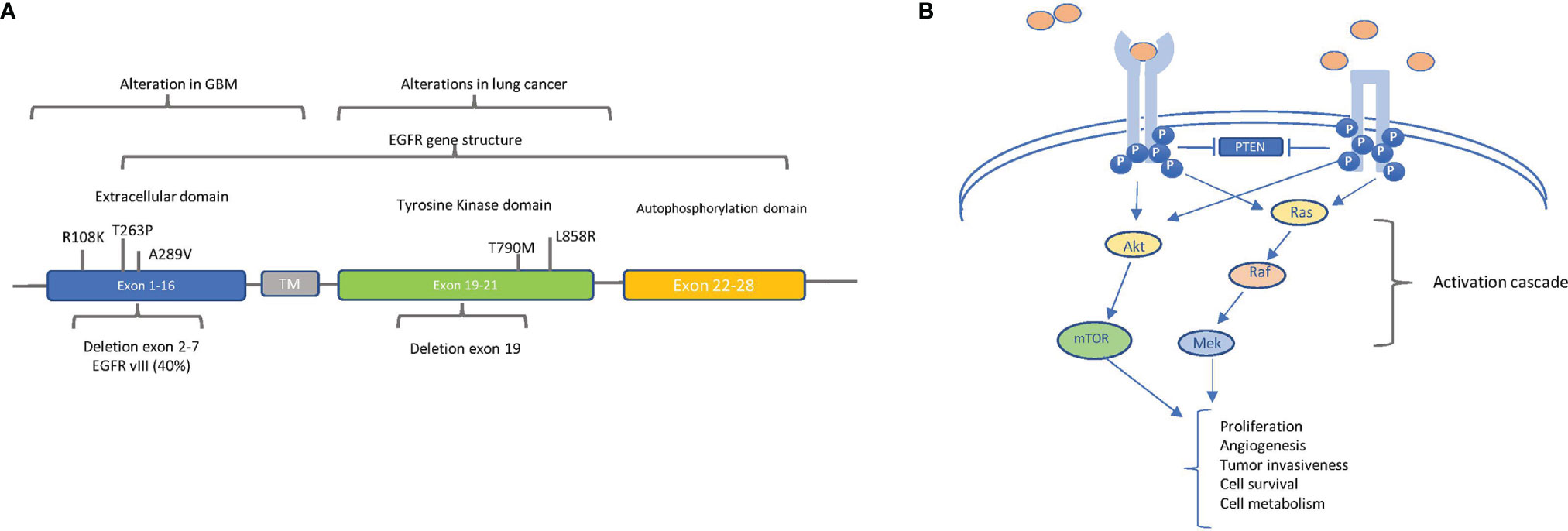

Specifically, EGFR gene amplification, resulting in high levels of protein expression, is detected at a high frequency rate (more than 50%) in GBM (23) and is associated with poor prognosis. In Figure 4A, the alterations found in GBM along with that found in lung cancer are reported.

Figure 4 The main oncogenic alterations of EGFR: (A) Localization of relevant alterations within the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene in glioblastoma (GBM) and lung cancer. The structural organization of EGFR exons and respective domains is shown. The principal point mutations and deletions in GBM (in exons 1–16, extracellular domain) and in lung cancer (in exons 19–20, tyrosine kinase domain) are indicated. The frequency of intragenic deletion in exons 2 to 7 (leading to variant EGFRvIII) is indicated. (B) EGFR (left) and EGFRvIII (right) signaling pathways. EGFR and EGFRvIII trigger the AKT and MAPK pathways, but ligands (pink circles) can bind and activate only EGFR, whereas EGFRvIII is constitutively active in a ligand-independent manner. Block arrows indicate inhibition. Point arrows indicate activation. The downstream processes of the activation cascade are described.

Of note is the fact that, in the majority of EGFR-amplified GBMs, an intragenic deletion in exons 2 to 7 leads to the distinctive production of the variant EGFRvIII, corresponding to a truncated constitutively active receptor (23). Besides gene amplification, the spectrum of the described EGFR alterations in GBM is quite heterogeneous—for example, EGFR overexpression can also result from increased gene transcription, without any DNA alterations, even if overexpression mostly correlates with gene amplification (24, 25). Additionally, in GBM, EGFR has been found to be constitutively active because of point mutations in the extracellular domain, especially A289V, R108K, and T263P (Figure 4A) (26). Regardless of the molecular mechanism causing constitutive activation, EGFR strongly induces GBM tumor growth and participates in other cell processes, such as autophagy, aerobic glycolysis, and biosynthesis of fatty acids and pyrimidines (Figure 4B) (27).

These observations altogether encouraged clinical trial studies of drugs targeting EGFR in GBM patients. However, until now, the results of the clinical trials involving tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are quite disappointing since they have shown limited activity. Even type II TKIs, which, by binding to the inactive kinase, had the potential to be more active in GBM (28), have failed in clinical trials—for example, one such drug, lapatinib, failed to show a significant activity in GBM patients (29).

Currently, among the more potent tested TKIs (30), TAS2940, a small molecule inhibitor of ERBB family proteins HER2 and EGFR, has entered phase I trial (14) (NCT04982926). Failure reasons of drugs targeting EGFR in GBM, compared to therapeutic efficacy observed in other tumors, may depend on several reasons, including GBM tissue heterogeneity and the restricted access of TKIs due to the BBB (31). Considering these limitations, two ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of two novel targeted agents able to cross the BBB: epitinib (HMPL-813), a potent and highly selective oral EGFR inhibitor, and WSD0922-FU, which prevents EGFR/EGFRvIII-mediated signaling (14, 32) (NCT04197934 and NCT03231501).

Another critical point underlying TKIs’ failure is the frequent mutation in the EGFR extracellular domain in GBM. However, these mutations might make GBM particularly susceptible to targeted extracellular interventions (33). Accordingly, the anti-EGFR antibody GC1118 is currently tested in a phase II trial (14) (NCT03618667), following promising preclinical results (34). Depatuxizumab mafodotin (Depatux-M), a selective antibody-conjugated drug comprising an EGFR-targeting antibody (ABT-414/806) together with the toxin monomethylauristatin-F, has instead shown no survival advantage in the phase III INTELLANCE-1 study, leading to the recommendation of trial stop by an independent data monitoring committee and the discontinuation of all ongoing related studies (35) (NCT02573324).

Additionally, the vaccine rindopepimut, targeting the GBM-peculiar EGFRvIII mutant, has been investigated in the series of ACT trials (36, 37). The phase II trial (ACTIVATE/ACT II) showed good tolerance with EGFRvIII-specific immunity, displaying encouraging results in increasing patients’ survival as confirmed in the phase II trial (ACT III) (38). However, these promising therapeutic effects failed in the phase III trial ACT IV, in which rindopepimut alone was compared, in newly diagnosed GBM, to the standard regimen of temozolomide and radiation therapy after maximal surgical resection (39). Rindopepimut has also been investigated in the Re-ACT trial, a double-blind randomized phase II trial evaluating GBM patients injected with vaccine plus bevacizumab and a control injection of keyhole limpet hemocyanin concurrent with bevacizumab (40). Alarmingly, in the Re-ACT trial, the experimental arm was built on two tethering columns: rindopepimut coming from a negative phase III trial and bevacizumab, which has not demonstrated a survival-related improvement being FDA-approved for treating relapsing GBM only based on progression-free survival benefit.

The Turn: Ras-Raf Signaling

The pathway controlled by RAS and the downstream cascade of kinases (mitogen-activated protein kinase—MAPK—and extracellular-regulated kinase—ERK) (Figure 2) is critically involved in most tumors. It is often activated in GBM, even in the absence of RAS mutations, due to its overstimulation by RTKs, such as EGFR. BRAF, a key mediator of the MAPK pathway, has been found mutated in about 7% of tumors arising in the central nervous system (41). The most frequently described (~90%) oncogenic driver mutation in BRAF is represented by the substitution of valine by glutamic acid at amino acid 600 (V600E). The mutated protein boosts about 500× the MAPK/ERK activation, resulting in uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival (42). BRAFV600E was reported in 69% of epithelioid GBM in a recent systematic review performed on more than 13,000 patients (43).

BRAF class I inhibitors (BRAFi) selectively bind to the mutated V600E BRAF protein, thus inhibiting MAPK/ERK signaling and the related effects on tumor growth. This class encompasses three FDA compounds approved for the treatment of BRAFV600-mutated metastatic malignant melanomas: vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib. Their use in melanoma has revealed that patients often acquire resistance to BRAFi through several molecular mechanisms, including the overactivation of RTKs such as EGFR (44). To overcome BRAFi resistance, a next-generation BRAF inhibitor, PLX8394, has been synthesized and reached phase I and II clinical trials (14) (NCT02428712), which include glioma patients. PLX8394 belongs to the novel dimer breakers that selectively target BRAF fusion proteins, splice variants as well as BRAF V600 monomers, leading to the inhibition of the overriding ERK signaling in tumors with sparing of BRAF function in normal cells in which signaling is driven by BRAF homodimers (44, 45). It should overcome resistance to the classical class I BRAF inhibitors by inducing a paradoxical, negative cooperativity effect, which means the activation of one BRAF monomer when the other is linked to a BRAF inhibitor (46).

Importantly, the combination of BRAF inhibitors with a drug inhibiting the downstream MEK protein reinforces the inhibition of MAPK/ERK signaling, delays the occurrence of acquired resistance, and reduces the adverse events related to BRAF inhibitors used as single agents (47). Three MEK inhibitors—cobimetinib, trametinib, and binimetinib—reached clinical approval in the USA and Europe. Nevertheless, they have a low BBB crossing rate that is limited by P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and Bcrp as reported by in vitro studies (48).

In the recent Rare Oncology Agnostic Research basket trial, the rate of responses to the combination of BRAF/MEK inhibition obtained in high-grade as well as in low-grade glioma cohorts has been encouraging (49), thus advocating BRAF testing in clinical practice (50, 51). In detail, at a median follow-up of 12.7 months (IQR, 5.4–32.3) among the 45 patients with high-grade tumors, three complete responses and 12 partial responses were reported (ORR, 33%; 95% CI, 20–49). At a median follow-up of 32.2 months (IQR, 25.1–47.8), in the low-grade cohort of 13 patients, one complete, six partial, and two minor responses were achieved (ORR, 69%; 95% CI, 39–91). A pediatric rollover phase IV study is ongoing (NCT03975829) (14). A phase II clinical study with the BRAF/MEK inhibitor combo encorafenib plus binimetinib is ongoing, with a foreseen primary estimated completion in July 2025 (14) (NCT03973918). Binimetinib is in the preliminary clinical phases also in combination with a new, potent, selective, highly brain-penetrant, small-molecule inhibitor of BRAF V600, PF-07284890 (14) (NCT04543188).

Besides BRAF point mutations, particularly in pilocytic astrocytomas, KIAA1549–BRAF gene fusions have been found (52). In these tumors, a phase I clinical trial (NCT03429803) and a phase II FIREFLY study (NCT04775485) (14) are investigating the efficacy of the pan-RAF inhibitor DAY 101 (tovorafenib, formerly TAK-580, MLN2480). The FIRELIGHT trial (phase Ib/II NCT04985604), a multi-center, open-label umbrella master study, is also investigating DAY101 as monotherapy in phase II and, in association with the novel oral MEK inhibitor pimasertib, in a phase I study. DAY 101 and other pan-BRAF inhibitors, by inhibiting also the wild-type protein, have, on one hand, the potential to inhibit MAPK/ERK pathway regardless of the activating BRAF mutation and the ability to overcome some resistance mechanisms; on the other hand, the therapeutic index is expected to be low (53).

NF-1

Apart from BRAF mutations, in glioma, RAS/MAPK signaling (Figure 2) can be activated by neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) gene inactivating mutations or deletions. The NF1-derived protein is named neurofibromin, which is a tumor suppressor RAS-GAP. The shutdown of RAS signaling, through the conversion of the GTP-bound active RAS form into the inactive GDP-bound form and the increasing levels of cAMP induced by neurofibromin, finally inhibits cell proliferation and survival (54). According to the vast evaluation performed by the Tumor Cancer Genome Atlas, a discrete percentage of GBMs (13 to 14%) are NF-1-mutated, and these tumors are characterized by a poor prognosis. NF-1-mutated GBMs are often associated with the mesenchymal subtype, with a bidirectional correspondence (55). Despite the fact that the loss of NF-1 function is related to resistance to targeted therapies, MEK inhibitors may be effective against NF-1-mutated brain tumors (56). Among those, pediatric inoperable plexiform neurofibromas may be eligible for treatment with selumetinib which was acknowledged as orphan drug by the FDA (57). An ongoing phase III study (NCT03871257) is evaluating selumetinib in comparison with chemotherapy in low-grade NF-1-associated gliomas (14).

Interestingly, the tumors with NF1 mutations, as compared with those with RAS or BRAF mutations, are characterized by a higher mutational burden and, thus, may be responsive to immunotherapy-based treatment strategy (58).

The Rules of the Game: Mesenchymal–Epithelial Transition Factor

Mesenchymal–epithelial transition (MET) is a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in several cell processes related not only to proliferation and cell survival but also to invasiveness and angiogenesis (Figure 2). In this capacity, it functions as a team player given the intricate crosstalk between MET and other signaling pathways. As an example, VEGFR and c-Met signaling cooperate in the control of angiogenesis and tumor growth (59, 60).

Overexpression is the most frequently found MET alteration, detected in 20–30% of high-grade gliomas, followed by amplification, found in 4% of primary GBM. About 3% of GBMs consist of a constitutively active ligand-independent MET protein, derived from exons 7 and 8 deletions in the MET gene (METΔ7-8) (61). Additionally, the MET exon 14 skipping mutation (METΔex14) produces an abnormal receptor lacking the juxtamembrane domain which activates MET downstream effectors in a ligand-independent manner.

Crizotinib is one of the first MET inhibitors tested in clinical studies together with other small-molecule inhibitors and anti-MET antibodies. However, a relative paucity of them have been rescued and moved forward in advanced late-stage clinical trials (62, 63).

Capmatinib, a highly selective MET inhibitor (INC280), has shown an overall response of 41% in non-small cell lung cancer patients harboring a METΔex14 mutation as compared with 29% in patients with MET amplification (64). The promising anticancer potential of this drug prompted the conduct of a phase I/II study (NCT01870726) using capmatinib alone and in combination with the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor buparlisib (65). Unfortunately, the published results were not particularly encouraging in terms of activity.

The MET inhibitor tepotinib has shown good tolerability and clinical activity in MET-dysregulated tumors. A phase II basket trial (NCT04647838) is ongoing to evaluate tepotinib in solid cancers with MET amplification or exon 14 mutation.

APL-101 is a novel, selective small-molecule MET inhibitor currently investigated in the SPARTA phase I/II trial (NCT03175224), including advanced solid tumors with METΔex14 and MET dysregulation (14).

Given the crosstalk between MET-induced and other signaling pathways, further research is looking towards combinatorial treatments to synergize and prevent resistance, such as VEGFR/c-Met dual-target inhibitors (59). One of them, dovitinib, reached phase II study but has not shown a clinically meaningful activity (66), and the same fate has befallen tivozanib (67) and cabozantinib (68).

Each on Its Own Way: Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Oncogenic Mutations

Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) comprises a family of RTKs consisting of four members (FGFR1–4) which are involved in several tumor-cell-related processes, such as proliferation, survival, invasion, and vessel growth (Figure 2). Twenty-two ligands and cell adhesion molecules, including the neural cell adhesion molecule, are known to bind these receptors and activate downstream signaling, including the PI3K-AKT and Ras-BRAF-MEK-ERK pathways (69). Comprehensively, amplifications, mutations, and translocations of FGFR genes are described in different tumors (69) with a quite composite arrangement: gene amplification, abnormal activation, or single-nucleotide polymorphisms mostly pertain to FGFR1 and FGFR2, while genetic fusions that involve FGFR1 and FGFR3 tyrosine kinase domains and the transforming acidic coiled-coil proteins generate oncoproteins. Similar to MET, an autocrine loop contributes to overstimulation of FGFR signaling.

FGFR inhibitors are in the earlier phase of clinical studies. Following on from the promising clinical results achieved by one of these compounds, infigratinib (BGJ398) in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 gene fusions or rearrangements (70), a phase I study (NCT04424966) is ongoing in recurrent high-grade glioma with definite mutations of FGFR1 or FGFR3 or translocations involving FGFR3 (14).

AZD4547 is an oral TKI selective for FGFR1, 2, and 3 which showed only a modest activity in patients with advanced cancer who harbor FGFR1, 2, or 3 alterations and enrolled in the arm of the National Cancer Institute—Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCT02465060) (71).

Either of One or of No One: Neurotrophic Tyrosine Receptor Kinase Fusions

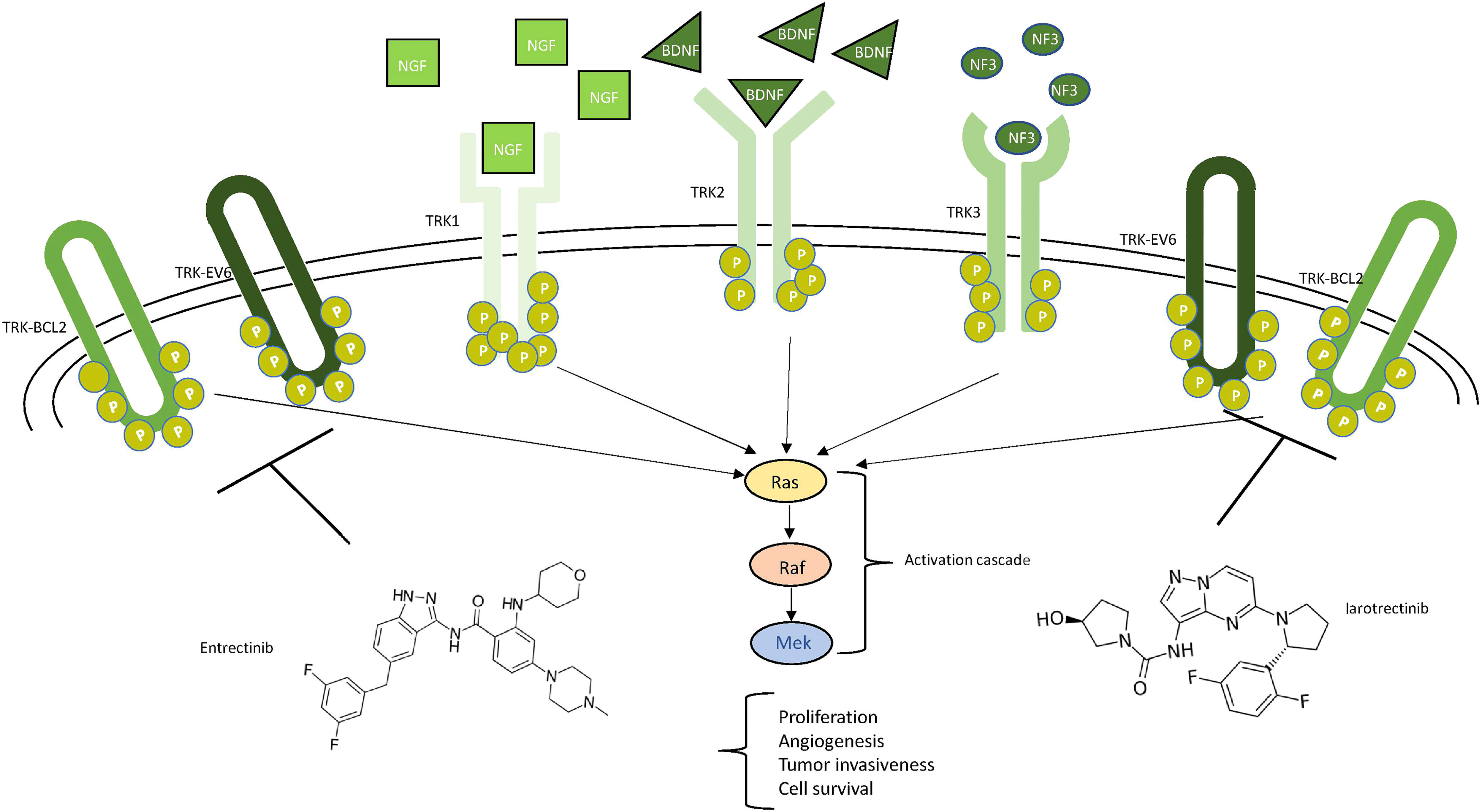

The neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) family comprises three genes—NTRK1 (1q21–q22), NTRK2 (9q22.1), and NTRK3 (15q25)—each encoding one receptor protein (TRKA, TRKB, TRKC or NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3) (Figure 5) with the same characteristics of the other transmembrane receptors with tyrosine kinase activity (72). The recognized ligands nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and neurotrophin-3 (NTF-3) exhibit a preferential binding with TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC, respectively (73–76). Upon ligand binding, receptor dimerization induces signals that promote cell survival and proliferation. The most common oncogenic NTRK aberrations produce fusion proteins able to activate signaling independently from ligand binding (76) (Figure 5). The constitutive activation of NTRK signaling induced by NTRK fusions has been recognized as oncogenic not only in different rare and aggressive tumors, such as salivary gland and infantile fibrosarcoma tumors (77), but also more commonly melanoma and thyroid carcinoma as well as lung, breast, and colon cancer (78, 79). NTRK fusions are less reported in glioma (0.55 to 2%) while exceeding 5% in pediatric high-grade gliomas (80). In some cases, the NTRK fusion correlates to the switch from low-grade to high-grade glioma (81).

Figure 5 Schematic view of NTRK signaling. Ligands (NGF in squares, BDNF in triangles, and NF3 in circles) and their respective receptors (TRK1/2/3) are represented. The main neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) fusion products (TRK-BCL1 and TRK-EV6) are represented as ellipticals as they do not need any ligand to be active. All the receptors trigger the MAPK pathway, leading to the indicated consequences. Two drugs, entrectinib and larotrectinib, can inhibit the NTRK aberrant forms as shown.

Larotrectinib is the first FDA-approved powerful and selective TRK inhibitor. Both in vitro and in vivo, larotrectinib inhibits kinase activity by blocking ATP binding sites and, in vivo, potently suppresses the growth of tumor cancer with TRKA and TRKB fusion proteins (82). Following several positive pre-clinical investigations (83, 84), three trials (NCT02122913; NCT02637687, SCOUT; and NCT02576431, NAVIGATE) led to FDA approval, but it should be emphasized that only one was a phase II basket trial while the others were phase I studies. The combined analysis of the two of these trials documented that the responses induced by larotrectinib were significant in terms of number, duration, and speed of onset (85). In December 2020, an early phase I clinical trial (NCT04655404) was started to evaluate the disease control rate in high-grade pediatric glioma with NTRK fusion (14).

Entrectinib is another orally available inhibitor with activity on TRKA/B/C, ROS1, and ALK (86, 87) developed to reach a high concentration in the central nervous system that correlates to high intracranial activity as shown in preclinical models (88). Two phase I dose-escalation studies and a phase II basket trial STARTRK-2 (NCT02568267) supported the activity of entrectinib. In 2020, an integrated analysis of these three clinical trials (89) confirmed that entrectinib is an effective treatment for patients with NTRK fusion-positive solid tumors. The results of the ongoing STARTRK-2 and STARTRK-NG trials are awaited to confirm the activity of entrectinib in NTRK fusion-positive tumors (90).

Selitrectinib and repotrectinib are next-generation TRK inhibitors developed to be used at the presentation of resistance. Clinical trials are ongoing (NCT03215511 and NCT03093116) (14).

Discussion

The therapeutic algorithm of GBM is based on some main indications with few evolutions over time. As proof, the Central Nervous System National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines have not required any update for more than a year (91). Surgery with radical intent, at diagnosis and relapse, is a bearing pillar, whereas medical treatments consist of the dated STUPP protocol following resection and limited therapeutic options while on a progressive disease. A significant advancement over standard treatment has been obtained with the intensification of adjuvant temozolomide with tumor-treating fields, which interferes with cell growth. This treatment achieved a reduction of about 40% in the risk of progression and death in a large, randomized trial (92).

However, GBM is not only an aggressive and ominous disease but also distinctively affects the entire body functions through the tumor itself and related edema, with invalidating symptoms such as headache, speech disturbances, loss of motor abilities, amnesia, sleep disorders, seizures, fatigue, and psychiatric disorders, with the need for a specialized team to counteract each of them. In front of this parade of symptoms, supportive care also turns around steroids, antiseizure drugs, and a few other beneficial medications. This perspective is rather frustrating because of the instinctive comparison between the therapeutic advancements in several types of cancer with the insufficient medical progress and invariably poor prognosis of GBM patients.

Genomics has radically changed the outcomes of many tumors with identifiable actionable and druggable mutations. Otherwise, the identification of gene alterations and presumptive key pathways has not translated into practice-changing results in GBM. There are different reasons underlying this paradoxical discrepancy.

First, there is the selection of molecules for clinical studies. Many times, drugs active in cell and animal models fail to confirm any activity in clinical trials. Of note is that the pre-clinical evaluation of most RTK-targeting molecules has been conducted in models harboring a unique genetic alteration that is far from the heterogeneous nature of GBM. Moreover, predetermined selection criteria based on molecular tumor signatures may address the rational use of RTK-targeting compounds.

The BBB, tumor edema, and necrosis limit the rate of the drug ultimately reaching the target tumor so that a pharmacodynamically effective concentration is not attained. As intuitively recognized, even the most powerful drug should exert a limited effect if does not reach an active concentration in brain tumors. One way to overcome the limited drug transition through the BBB is local administration at surgery time when access to the tumor area is easier—for example, with gliadel wafers which, however, reported controversial results (93). The next-generation approaches, including biomaterials, alternative formulations, and targeted delivery, bear the promise to improve the glioblastoma therapy outcomes. Targeted delivery includes the selection of biochemical compounds interacting with a ligand highly expressed in brain tumor and studies of pharmacokinetics improving drug distribution and reducing elimination. The most promising approaches concern nanoparticles and exosomes loading the active cargo and efficiently carrying it at the tumor site.

Most studies are investigating the complex nature of glioblastoma which even increases if we look immediately outside the restricted field of tumor cells: the composite network of immune cells, blood vessels, and the microglia compartments which reciprocally interact. These cells are presumed to be more stable and perhaps targetable (94). However, it is hard to identify a unique hypothetical Achilles’ heel.

Intensive medical research concern immunotherapy which, however, require being adaptively inclined to glioblastoma specificity. This tumor is fundamentally immune resistant as documented by some intrinsic features, such as low tumor mutational burden, a highly immunosuppressive microenvironment, and tumor heterogeneity, without counting systemic immunosuppression which is often associated with glioblastoma because of steroid concomitant use. Moreover, primitive and relapsed tumors are different in their gene signatures, thus exhibiting a different response to a defined treatment, as recent studies suggested (95). This is the shape-shifting nature of glioblastoma—changing constantly its appearance to prevail over the host. The selection by different parameters, such as high towards low tumor mutational burden, may help to individualize treatment strategies. Moreover, the combination of procedures, such as radiotherapy, which itself increases antigen presentation with enhanced immunotherapy by the use of immune adjuvants or dendritic cells, bears the promise that the desert landscape of glioblastoma will change.

Looking at the role of gene pathways that preliminarily raise important expectations, such as EGFR, two main mechanisms have been suggested: target independence, namely, alterations in the target that becomes insensitive to inhibition, and target compensation; in other words, the activation of alternative pathways (96). GBM cells are probably dependent on several growth pathways and are particularly skilled to escape a one-modality attempt. The dynamics of GBM cells with their adaptive nature to change under therapeutic and metabolic pressure (97) and the role of microenvironment with other peculiar metabolic and molecular signatures (98) even complicate the enigmatic nature of this tumor. Since GBMs are characterized by multiple genetic as well as epigenetic mutations within the same tumor, it is fundamental to perform extensive research using single-cell technology to comprehensively define GBM heterogeneity. These results will not only elucidate the unclear GMB-related biological mechanisms but will also identify genomic signatures and address treatment strategies, including combinatorial therapy. On top of that, it remains also crucial to recognize new druggable targets driving GBM onset, maintenance, and progression that will contribute to changing the present treatment algorithms.

Concerning NTRK and BRAF, they are found only in a minority of adult cases. A relatively low percentage of a definite alteration is hard to represent in a paradigm shift for the whole. Moreover, the low rates of these alterations allow only for phase II and basket/umbrella trials, with phase III studies being unfeasible. Consequently, these studies are not candidates for evaluation through a standardized approach such as the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale aimed at defining the unbiased magnitude of the clinical benefit given by a new anticancer therapy (99).

To date, the expectations placed in precision medicine and, particularly, in genomics determine the heterogeneous use of cancer gene platforms worldwide, which does not always correspond to the principles of evidence-based medicine and available guidelines. In the future, it will be urgent to unravel the molecular pathways involved in GBM drug resistance mechanisms as well as improve drug delivery approaches to bypass BBB. Next-generation sequencing methods should be part of national and international studies, including data banking and platform trials integrated with artificial intelligence and machine-learning-based approaches, which can disclose the composite and mutable nature of glioblastoma.

Author Contributions

LM, RDM, LA, NG, GB, and LC: conceptualization and methodology. LM, NG, and LA: writing, original draft preparation, and data curation. LM, MC, MB, DC, RV, GF, RDM, LA, NG, GB, LA, GF, and LC: visualization and supervision. LM, RDM, MB, DC, and RV: figures. LM, LA, and NG: writing—reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Campania Regional Government Lotta alle Patologie Oncologiche iCURE (CUP B21C17000030007); MIUR Proof of Concept (POC01_00043); MISE: Nabucco Project; VALERE: Vanvitelli per la Ricerca Program: EPInhibitDRUGre (CUP B66J20000680005). Campania Regional Government FASE 2: IDEAL (CUP B63D18000560007); NDG is supported by PON Ricerca e Innovazione 2014-2020- Linea 1, AIM - AIM1859703.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Radiotherapy Plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med (2005) 352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330

2. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit From Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med (2005) 352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331

3. Taylor OG, Brzozowski JS, Skelding KA. Glioblastoma Multiforme: An Overview of Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Front Oncol (2019) 9:963. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00963

4. Lombardi G, De Salvo GL, Brandes AA, Eoli M, Rudà R, Faedi M, et al. Regorafenib Compared With Lomustine in Patients With Relapsed Glioblastoma (REGOMA): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol (2019) 20:110–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30675-2

5. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Neuro Oncol (2021) 23:1231–51. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106

6. Jafri MA, Ansari SA, Alqahtani MH, Shay JW. Roles of Telomeres and Telomerase in Cancer, and Advances in Telomerase-Targeted Therapies. Genome Med (2016) 69:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0324-x

7. Aquilanti E, Kageler L, Wen PY, Meyerson M. Telomerase as a Therapeutic Target in Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol (2021) 23:2004–13. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab203

8. Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Diaz LA, et al. TERT Promoter Mutations Occur Frequently in Gliomas and a Subset of Tumors Derived From Cells With Low Rates of Self-Renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:6021–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303607110

9. Kikuchi Z, Shibahara I, Yamaki T, Yoshioka E, Shofuda T, Ohe R, et al. TERT Promoter Mutation Associated With Multifocal Phenotype and Poor Prognosis in Patients With IDH Wild-Type Glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol Adv (2020) 2:vdaa114. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa114

10. Vuong HG, Nguyen TQ, Ngo TNM, Nguyen HC, Fung K-M, Dunn IF. The Interaction Between TERT Promoter Mutation and MGMT Promoter Methylation on Overall Survival of Glioma Patients: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer (2020) 20:897. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07364-5

11. Gramatzki D, Felsberg J, Hentschel B, Wolter M, Schackert G, Westphal M, et al. Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Promoter Mutation- and O 6-Methylguanine DNA Methyltransferase Promoter Methylation-Mediated Sensitivity to Temozolomide in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-Wild-Type Glioblastoma: Is There a Link? Eur J Cancer (2021) 147:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.014

12. Marian CO, Cho SK, McEllin BM, Maher EA, Hatanpaa KJ, Madden CJ, et al. The Telomerase Antagonist, Imetelstat, Efficiently Targets Glioblastoma Tumor-Initiating Cells Leading to Decreased Proliferation and Tumor Growth. Clin Cancer Res (2010) 16:154–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2850

13. Ferrandon S, Malleval C, El Hamdani B, Battiston-Montagne P, Bolbos R, Langlois JB, et al. Telomerase Inhibition Improves Tumor Response to Radiotherapy in a Murine Orthotopic Model of Human Glioblastoma. Mol Cancer (2015) 14:134. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0376-3

14. . Available at: https://Clinicaltrials.gov/ (Accessed March 19th , 2022).

15. Yu S, Wei S, Savani M, Lin X, Du K, Mender I, et al. A Modified Nucleoside 6-Thio-2'-Deoxyguanosine Exhibits Antitumor Activity in Gliomas. Clin Cancer Res (2021) 27:6800–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0374

16. Takahashi M, Miki S, Fujimoto K, Fukuoka K, Matsushita Y, Maida Y, et al. Eribulin Penetrates Brain Tumor Tissue and Prolongs Survival of Mice Harboring Intracerebral Glioblastoma Xenografts. Cancer Sci (2019) 110:2247–57. doi: 10.1111/cas.14067

17. Miki S, Imamichi S, Fujimori H, Tomiyama A, Fujimoto K, Satomi K, et al. Concomitant Administration of Radiation With Eribulin Improves the Survival of Mice Harboring Intracerebral Glioblastoma. Cancer Sci (2018) 109:2275–85. doi: 10.1111/cas.13637

18. Lavanya C, Venkataswamy MM, Sibin MK, Srinivas Bharath MM, Chetan GK. Down Regulation of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (hTERT) Expression by BIBR1532 in Human Glioblastoma LN18 Cells. Cytotechnology (2018) 70:1143–54. doi: 10.1007/s10616-018-0205-9

19. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive Genomic Characterization Defines Human Glioblastoma Genes and Core Pathways. Nature (2008) 455:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385

20. Oprita A, Baloi SC, Staicu GA, Alexandru O, Tache DE, Danoiu S, et al. Updated Insights on EGFR Signaling Pathways in Glioma. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:587. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020587

21. Lombardi MY, Assem M, De Vleeschouwer S. Glioblastoma Genomics: A Very Complicated 447 Story. In: Glioblastoma, vol. 448. . Brisbane (AU: Codon Publications (2017). p. 1. doi: 10.15586/codon.glioblastoma.2017.ch1

22. Hobbs J, Nikiforova MN, Fardo DW, Bortoluzzi S, Cieply K, Hamilton RL, et al. Paradoxical Relationship Between Degree of EGFR Amplification and Outcome in Glioblastomas. Am J Surg Pathol (2012) 36:1186–93. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182518e12

23. Felsberg J, Hentschel B, Kaulich K, Gramatzki D, Zacher A, Malzkorn B, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Variant III (EGFRvIII) Positivity in EGFR-Amplified Glioblastomas: Prognostic Role and Comparison Between Primary and Recurrent Tumors. Clin Cancer Res (2017) 23:6846–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0890

24. Viana-Pereira M, Lopes JM, Little S, Milanezi F, Basto D, Pardal F, et al. Analysis of EGFR Overexpression, EGFR Gene Amplification and the EGFRvIII Mutation in Portuguese High-Grade Gliomas. Anticancer Res (2008) 28:913–20.

25. Lopez-Gines C, Gil-Benso R, Ferrer-Luna R, Benito R, Serna E, Gonzalez-Darder J, et al. New Pattern of EGFR Amplification in Glioblastoma and the Relationship of Gene Copy Number With Gene Expression Profile. Mod Pathol (2010) 23:856–65. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.62

26. Lee JC, Vivanco I, Beroukhim R, Huang JHY, Feng WL, DeBiasi RM, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Activation in Glioblastoma Through Novel Missense Mutations in the Extracellular Domain. PloS Med (2006) 3:e485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030485

27. Montella L, Sarno F, Altucci L, Cioffi V, Sigona L, Di Colandrea S, et al. A Root in Synapsis and the Other One in the Gut Microbiome-Brain Axis: Are the Two Poles of Ketogenic Diet Enough to Challenge Glioblastoma? Front Nutr (2021) 8:703392. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.703392

28. Orellana L, Thorne AH, Lema R, Gustavsson J, Parisian AD, Hospital A, et al. Oncogenic Mutations at the EGFR Ectodomain Structurally Converge to Remove a Steric Hindrance on a Kinase-Coupled Cryptic Epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116:10009–18. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821442116

29. Thiessen B, Stewart C, Tsao M, Kamel-Reid S, Schaiquevich P, Mason W, et al. A Phase I/II Trial of GW572016 (Lapatinib) in Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme: Clinical Outcomes, Pharmacokinetics and Molecular Correlation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2010) 65:353–61. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1041-6

30. Sepúlveda-Sánchez JM, Vaz M.Á, Balañá C, Gil-Gil M, Reynés G, Gallego Ó., et al. Phase II Trial of Dacomitinib, a Pan-Human EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, in Recurrent Glioblastoma Patients With EGFR Amplification. Neuro Oncol (2017) 19:1522–31. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox105

31. Aldaz P, Arozarena I. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Adult Glioblastoma: An (Un)Closed Chapter? Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13:5799. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225799

32. Bolcaen J, Nair S, Driver CHS, Boshomane TMG, Ebenhan T, Vandevoorde C. Novel Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Pathway Inhibitors for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy of Glioblastoma. Pharm (Basel) (2021) 14:626. doi: 10.3390/ph14070626

33. Kilian M, Bunse T, Wick W, Platten M, Bunse L. Genetically Modified Cellular Therapies for Malignant Gliomas. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:12810. doi: 10.3390/ijms222312810

34. Lee K, Koo H, Kim Y, Kim D, Son E, Yang H, et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of GC1118, a Novel Anti-EGFR Antibody, Against Glioblastoma With High EGFR Amplification in Patient-Derived Xenografts. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:3210. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113210

35. Van Den Bent M, Eoli M, Sepulveda JM, Smits M, Walenkamp A, Frenel J-S, et al. INTELLANCE 2/EORTC 1410 Randomized Phase II Study of Depatux-M Alone and With Temozolomide vs Temozolomide or Lomustine in Recurrent EGFR Amplified Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol (2020) 22:684–93. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz222

36. Platten M. EGFRvIII Vaccine in Glioblastoma-InACT-IVe or Not ReACTive Enough? Neuro Oncol (2017) 19:1425–6. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox167

37. Platten M, Bunse L, Riehl D, Bunse T, Ochs K, Wick W. Vaccine Strategies in Gliomas. Curr Treat Options Neurol (2018) 20:11. doi: 10.1007/s11940-018-0498-1

38. Schuster J, Lai RK, Recht LD, Reardon DA, Paleologos NA, Groves MD, et al. A Phase II, Multicenter Trial of Rindopepimut (CDX-110) in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: The ACT III Study. Neuro Oncol (2015) 17:854–61. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou348

39. Weller M, Butowski N, Tran DD, Recht LD, Lim M, Hirte H, et al. Rindopepimut With Temozolomide for Patients With Newly Diagnosed, EGFRvIII-Expressing Glioblastoma (ACT IV): A Randomised, Double-Blind, International Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18:1373–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30517-X

40. Reardon DA, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, O'Rourke DM, Tran DM, Fink KL, et al. Rindopepimut With Bevacizumab for Patients With Relapsed EGFRvIII-Expressing Glioblastoma (ReACT): Results of a Double-Blind Randomized Phase II Trial. Clin Cancer Res (2020) 26:1586–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1140

41. Bouchè V, Aldegheri G, Donofrio CA, Fioravanti A, Roberts-Thomson S, Fox SB, et al. BRAF Signaling Inhibition in Glioblastoma: Which Clinical Perspectives? Front Oncol (2021) 11:772052. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.772052

42. Tuncel G, Kalkan R. Receptor Tyrosine Kinase-Ras-PI 3 Kinase-Akt Signaling Network in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Med Oncol (2018) 35:122. doi: 10.1007/s12032-018-1185-5

43. Andrews LJ, Thornton ZA, Saincher SS, Yao IY, Dawson S, McGuinness LA, et al. Prevalence of BRAFV600 in Glioma and Use of BRAF Inhibitors in Patients With BRAFV600 Mutation-Positive Glioma: Systematic Review. Neuro Oncol (2021) 28:noab247. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab247

44. Schreck KC, Morin A, Zhao G, Allen AN, Flannery P, Glantz M, et al. Deconvoluting Mechanisms of Acquired Resistance to RAF Inhibitors in BRAF V600E-Mutant Human Glioma. Clin Cancer Res (2021) 27:6197–208. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2660

45. Yao A, Gao Y, Su W, Yaeger R, Tao J, Na N, et al. RAF Inhibitor PLX8394 Selectively Disrupts BRAF Dimers and RAS-Independent BRAF-Mutant-Driven Signaling. Nat Med (2019) 25:284–91. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0274-5

46. Pickles OJ, Drozd A, Tee L, Beggs AD, Middleton GW. Paradox Breaker BRAF Inhibitors Have Comparable Potency and MAPK Pathway Reactivation to Encorafenib in BRAF Mutant Colorectal Cancer. Oncotarget (2020) 11:3188–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27681

47. Subbiah V, Baik C, Kirkwood JM. Clinical Development of BRAF Plus MEK Inhibitor Combinations. Trends Cancer (2020) 6:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.05.009

48. Vaidhyanathan S, Mittapalli RK, Sarkaria JN, Elmquist WF. Factors Influencing the CNS Distribution of a Novel MEK-1/2 Inhibitor: Implications for Combination Therapy for Melanoma Brain Metastases. Drug Metab Dispos (2014) 42:1292–300. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.058339

49. Wen PY, Stein A, van den Bent M, De Greve J, Wick A, de Vos FYFL, et al. Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib in Patients With BRAF V600E-Mutant Low-Grade and High-Grade Glioma (ROAR): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase 2, Basket Trial. Lancet Oncol (2022) 23:53–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00578-7

50. Li Y, Yang S, Hao C, Chen J, Li S, Kang Z, et al. Effect of BRAF/MEK Inhibition on Epithelioid Glioblastoma With BRAFV600E Mutation: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin Lab (2020) 66. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2020.191134

51. Woo PYM, Lam T-C, Pu JKS, Li L-F, Leung RCY, Ho JMK, et al. Regression of BRAFV600E Mutant Adult Glioblastoma After Primary Combined BRAF-MEK Inhibitor Targeted Therapy: A Report of Two Cases. Oncotarget (2019) 10:3818–26. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26932

53. Wang X, Zhang H, Chen X. Drug Resistance and Combating Drug Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Drug Resist (2019) 2:141–60. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2019.10

54. Philpott C, Tovell H, Frayling IM, Cooper DN, Upadhyaya M. The NF1 Somatic Mutational Landscape in Sporadic Human Cancers. Hum Genomics (2017) 11:13. doi: 10.1186/s40246-017-0109-3

55. Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated Genomic Analysis Identifies Clinically Relevant Subtypes of Glioblastoma Characterized by Abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell (2010) 17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020

56. Harder A. MEK Inhibitors - Novel Targeted Therapies of Neurofibromatosis Associated Benign and Malignant Lesions. biomark Res (2021) 9:26. doi: 10.1186/s40364-021-00281-0

57. Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, et al. Selumetinib in Children With Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N Engl J Med (2020) 382:1430–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912735

58. Liu W-J, Du Y, Wen R, Yang M, Xu J. Drug Resistance to Targeted Therapeutic Strategies in non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Pharmacol Ther (2020) 206:107438. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107438

59. Zhang Q, Zheng P, Zhu W. Research Progress of Small Molecule VEGFR/c-Met Inhibitors as Anticancer Agents (2016-Present). Molecules (2020) 25:2666. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112666

60. Xie Q, Bradley R, Kang L, Koeman J, Ascierto ML, Worschech A, et al. Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) Autocrine Activation Predicts Sensitivity to MET Inhibition in Glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:570–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119059109

61. Qin A, Musket A, Musich PR, Schweitzer JB, Xie Q. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases as Druggable Targets in Glioblastoma: Do Signaling Pathways Matter? Neurooncol Adv (2021) 3:vdab133. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdab133

62. Le Rhun E, Chamberlain MC, Zairi F, Delmaire C, Idbaih A, Renaud F, et al. Patterns of Response to Crizotinib in Recurrent Glioblastoma According to ALK and MET Molecular Profile in Two Patients. CNS Oncol (2015) 4:381–6. doi: 10.2217/cns.15.30

63. Rodig SJ, Shapiro GI. Crizotinib, a Small-Molecule Dual Inhibitor of the C-Met and ALK Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Curr Opin Investig Drugs (2010) 11:1477–90.

64. Falchook GS, Kurzrock R, Amin HM, Xiong W, Fu F, Piha-Paul SA, et al. First-In-Man Phase I Trial of the Selective MET Inhibitor Tepotinib in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res (2020) 26:1237–46. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2860

65. van den Bent M, Azaro A, De Vos F, Sepulveda J, Yung WKA, Wen PY, et al. A Phase Ib/II, Open-Label, Multicenter Study of INC280 (Capmatinib) Alone and in Combination With Buparlisib (BKM120) in Adult Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol (2020) 146:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03337-2

66. Sharma M, Schilero C, Peereboom DM, Hobbs BP, Elson P, Stevens GHJ, et al. Phase II Study of Dovitinib in Recurrent Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol (2019) 144:359–68. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03236-6

67. Kalpathy-Cramer J, Chandra V, Da X, Ou Y, Emblem KE, Muzikansky A, et al. Phase II Study of Tivozanib, an Oral VEGFR Inhibitor, in Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol (2017) 131:603–10. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2332-5

68. Wen PY, Drappatz J, de Groot J, Prados MD, Reardon DA, Schiff D, et al. Phase II Study of Cabozantinib in Patients With Progressive Glioblastoma: Subset Analysis of Patients Naive to Antiangiogenic Therapy. Neuro Oncol (2018) 20:249–58. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox154

69. Ardizzone A, Scuderi SA, Giuffrida D, Colarossi C, Puglisi C, Campolo M, et al. Role of Fibroblast Growth Factors Receptors (FGFRs) in Brain Tumors, Focus on Astrocytoma and Glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:3825. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123825

70. Javle M, Roychowdhury S, Kelley RK, Sadeghi S, Macarulla T, Weiss KH, et al. Infigratinib (BGJ398) in Previously Treated Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Cholangiocarcinoma With FGFR2 Fusions or Rearrangements: Mature Results From a Multicentre, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol (2021) 6:803–15. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00196-5

71. Chae YK, Hong F, Vaklavas C, Cheng HH, Hammerman P, Mitchell EP, et al. Phase II Study of AZD4547 in Patients With Tumors Harboring Aberrations in the FGFR Pathway: Results From the NCI-MATCH Trial (EAY131) Subprotocol W. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38:2407–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02630

72. Amatu A, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S. NTRK Gene Fusions as Novel Targets of Cancer Therapy Across Multiple Tumour Types. ESMO Open (2016) 1:e000023. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2015-000023

73. Nakagawara A, Liu XG, Ikegaki N, White PS, Yamashiro DJ, Nycum LM, et al. Cloning and Chromosomal Localization of the Human TRK-B Tyrosine Kinase Receptor Gene (NTRK2). Genomics (1995) 25:538–46. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80055-q

74. Valent A, Danglot G, Bernheim A. Mapping of the Tyrosine Kinase Receptors trkA (NTRK1), trkB (NTRK2) and trkC (NTRK3) to Human Chromosomes 1q22, 9q22 and 15q25 by Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization. Eur J Hum Genet (1997) 5:102–4. doi: 10.1159/000484742

75. Mardy S, Miura Y, Endo F, Matsuda I, Sztriha L, Frossard P, et al. Congenital Insensitivity to Pain With Anhidrosis: Novel Mutations in the TRKA (NTRK1) Gene Encoding a High-Affinity Receptor for Nerve Growth Factor. Am J Hum Genet (1999) 64:1570–9. doi: 10.1086/302422

76. Weiss LM, Funari VA. NTRK Fusions and Trk Proteins: What are They and How to Test for Them. Hum Pathol (2021) 112:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2021.03.007

77. Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, DuBois SG, Lassen UN, Demetri GD, et al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Cancers in Adults and Children. N Engl J Med (2018) 378:731–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

78. Harada G, Santini FC, Wilhelm C, Drilon A. NTRK Fusions in Lung Cancer: From Biology to Therapy. Lung Cancer (2021) 161:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.09.005

79. Solomon JP, Benayed R, Hechtman JF, Ladanyi M. Identifying Patients With NTRK Fusion Cancer. Ann Oncol (2019) 30 Suppl 8:viii16–22. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz384

80. Torre M, Vasudevaraja V, Serrano J, DeLorenzo M, Malinowski S, Blandin A-F, et al. Molecular and Clinicopathologic Features of Gliomas Harboring NTRK Fusions. Acta Neuropathol Commun (2020) 8:107. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-00980-z

81. Jones KA, Bossler AD, Bellizzi AM, Snow AN. BCR-NTRK2 Fusion in a Low-Grade Glioma With Distinctive Morphology and Unexpected Aggressive Behavior. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud (2019) 5:a003855. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a003855

82. Hong DS, DuBois SG, Kummar S, Farago AF, Albert CM, Rohrberg KS, et al. Larotrectinib in Patients With TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumours: A Pooled Analysis of Three Phase 1/2 Clinical Trials. Lancet Oncol (2020) 21:531–40. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30856-3

83. Rosen EY, Schram AM, Young RJ, Schreyer MW, Hechtman JF, Shu CA, et al. Larotrectinib Demonstrates CNS Efficacy in TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors. JCO Precis Oncol (2019) 3:PO.19.00009. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00009

84. Ziegler DS, Wong M, Mayoh C, Kumar A, Tsoli M, Mould E, et al. Brief Report: Potent Clinical and Radiological Response to Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Driven High-Grade Glioma. Br J Cancer (2018) 119:693–6. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0251-2

85. Doz F, van Tilburg CM, Geoerger B, Højgaard M, Øra I, Boni V, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Primary Central Nervous System Tumors. Neuro Oncol (2021) 27:noab274. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab274

86. Al-Salama ZT, Keam SJ. Entrectinib: First Global Approval. Drugs (2019) 79:1477–83. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01177-y

87. Han S-Y. TRK Inhibitors: Tissue-Agnostic Anti-Cancer Drugs. Pharm (Basel) (2021) 14:632. doi: 10.3390/ph14070632

88. Jørgensen JT. Twenty Years With Personalized Medicine: Past, Present, and Future of Individualized Pharmacotherapy. Oncologist (2019) 21:e432–40. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0054

89. Drilon A, Nagasubramanian R, Blake JF, Ku N, Tuch BB, Ebata K, et al. A Next-Generation TRK Kinase Inhibitor Overcomes Acquired Resistance to Prior TRK Kinase Inhibition in Patients With TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors. Cancer Discovery (2017) 7:963–72. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0507

90. Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, Siena S, Shaw AT, Farago AF, et al. Trial Investigators. Entrectinib in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic NTRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumours: Integrated Analysis of Three Phase 1-2 Trials. Lancet Oncol (2020) 21:271–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

91. Muir M, Gopakumar S, Traylor J, Lee S, Rao G. Glioblastoma Multiforme: Novel Therapeutic Targets. Expert Opin Ther Targets (2020) 24:605–14. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1762568

92. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, Read W, Steinberg D, Lhermitte B, et al. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA (2017) 318:2306–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18718

93. Gromeier M, Brown MC, Zhang G, Lin X, Chen Y, Wei Z, et al. Very Low Mutation Burden is a Feature of Inflamed Recurrent Glioblastomas Responsive to Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat Commun (2021) 12:352. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20469-6

94. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1 (Accessed 20.03.2022).

95. Tabet A, Jensen MP, Parkins CC, Patil PG, Watts C, Scherman OA. Designing Next-Generation Local Drug Delivery Vehicles for Glioblastoma Adjuvant Chemotherapy: Lessons From the Clinic. Adv Healthc Mater (2019) 8:e1801391. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801391

96. Saleem H, Abdul UK, Küçükosmanoglu A, Houweling M, Cornelissen FMG, Heiland DH, et al. The TICking Clock of EGFR Therapy Resistance in Glioblastoma: Target Independence or Target Compensation. Drug Resist Update (2019) 43:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.04.002

97. Wang Z, Zhang H, Xu S, Liu Z, Cheng Q. The Adaptive Transition of Glioblastoma Stem Cells and its Implications on Treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2021) 6:124. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00491-w

98. Virtuoso A, Giovannoni R, De Luca C, Gargano F, Cerasuolo M, Maggio N, et al. The Glioblastoma Microenvironment: Morphology, Metabolism, and Molecular Signature of Glial Dynamics to Discover Metabolic Rewiring Sequence. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:3301. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073301

99. Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Dafni U, Kerst JM, Sobrero A, Zielinski C, et al. A Standardised, Generic, Validated Approach to Stratify the Magnitude of Clinical Benefit That can be Anticipated From Anti-Cancer Therapies: The European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Ann Oncol (2015) 26:1547–73. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv249

Keywords: glioblastoma, targeted therapy, EGFR, B-Raf, Met, NF-1

Citation: Montella L, Del Gaudio N, Bove G, Cuomo M, Buonaiuto M, Costabile D, Visconti R, Facchini G, Altucci L, Chiariotti L and Della Monica R (2022) Looking Beyond the Glioblastoma Mask: Is Genomics the Right Path? Front. Oncol. 12:926967. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.926967

Received: 23 April 2022; Accepted: 09 June 2022;

Published: 06 July 2022.

Edited by:

Shmuel Jaffe Cohen, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, IsraelReviewed by:

Aram S. Modrek, New York University, United StatesDanilo Maddalo, Genentech, Inc., United States

Copyright © 2022 Montella, Del Gaudio, Bove, Cuomo, Buonaiuto, Costabile, Visconti, Facchini, Altucci, Chiariotti and Della Monica. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liliana Montella, bGlsaWFuYS5tb250ZWxsYUBhc2xuYXBvbGkybm9yZC5pdA==

Liliana Montella

Liliana Montella Nunzio Del Gaudio

Nunzio Del Gaudio Guglielmo Bove

Guglielmo Bove Mariella Cuomo3,4

Mariella Cuomo3,4 Davide Costabile

Davide Costabile Gaetano Facchini

Gaetano Facchini Lucia Altucci

Lucia Altucci Lorenzo Chiariotti

Lorenzo Chiariotti Rosa Della Monica

Rosa Della Monica