94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Oncol., 28 April 2022

Sec. Hematologic Malignancies

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.873903

m6A modification is the most common modification in eukaryotes. METTL3, as a core methyltransferase of m6A modification, plays a vital role in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Recent studies have shown that METTL3 is required for normal and symmetric differentiation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs). Moreover, METTL3 strongly impacts the process and development of hematological neoplasms, including the differentiation, apoptosis, proliferation, chemoresistance, and risk of tumors. Novel inhibitors of METTL3 have been identified and studied in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells. STM2457, a selective inhibitor of METTL3, has been identified to block proliferation and promote differentiation and apoptosis of AML cells without impacting normal hematopoiesis. Therefore, in our present review, we focus on the structure of METTL3, the role of METTL3 in both normal and malignant hematopoiesis, and the potential of METTL3 for treating hematological neoplasms.

Epigenetic modifications have been identified to be involved in many physiological and pathological processes in most eukaryotes without DNA sequence changes (1), including DNA methylation, histone modification, RNA methylation, and noncoding RNA regulation (2). Unlike DNA methylation and histone modification, RNA methylation is still at an infant stage. Among RNA methylation modifications, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant internal modification of messenger RNA (mRNA) (3), which was first discovered in Novikoff hepatoma cells in 1974 (4). However, due to the lack of robust methods to detect the precise modification sites of m6A in mRNA, interest in m6A research has been hindered significantly. It was not until 2011 that fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) was discovered as a m6A demethylase, indicating the reversibility of the m6A modification on mRNA (5). Meanwhile, detection technology has been largely improved and has benefited the investigation of m6A modification on mRNA. Dominissini et al. and Meyer et al. independently used high-throughput sequencing to detect m6A modification at the whole transcriptome level, revealing the main distribution of m6A near stop codons, 3′ or 5′-untranslated terminal regions (UTRs), and long exons (5, 6). Due to the two critical advances, the enthusiasm and motivation of m6A research have been refueled, resulting in a flood of studies on the m6A modification on mRNA in eukaryotes.

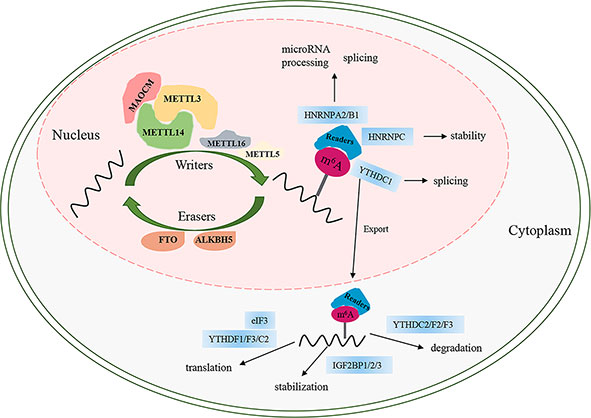

Similar to DNA methylation, m6A is a reversible and dynamic process regulated by three categories of enzymes, namely, “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers” (Figure 1). At present, FTO and ALKB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) are the only two identified “erasers” that are responsible for reversing m6A (5, 7) (Figure 1). FTO, the first m6A demethylase identified in 2011, has strongly promoted the development of research on m6A. The demethylation activity of ALKBH5 significantly impacts mRNA export, RNA metabolism, and mRNA processing factor assembly (8). The final biological function of m6A is mainly associated with m6A “readers” that recognize sites of m6A and induce it to bind to the target sites to perform different functions involving mRNA degradation, translation, splicing, stability, and export (9–15) (Figure 1). m6A can be recognized by a set of RNA-binding proteins, including YT521-B homology (YTH) domain family proteins (YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2) (10–13, 16), insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs, including IGF2BP1/2/3) (15), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (including HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPG, and HNRNPC), and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (eIF3) (9, 17, 18). m6A is installed by methyltransferases (writers), which comprise several different “writer” proteins, including methyltransferase-like 3/5/14/16 (METTL3/5/14/16), Wilms tumor 1-associated protein (WTAP), Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA, also called KIAA1429), RNA binding motif protein 15/15B (RBM15/15B), zinc finger CCHC-type containing 4 (ZCCHC4), and zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13) (19) (Figure 1). Among the methyltransferases, METTL3 is the only one that has the S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-binding protein in the catalytic pocket and composes a stable methyltransferase complex (MTC) heterodimer with METTL14 at 1:1 to exert methylation activity (20). Moreover, the activity of the METTL3/METTL14 core complex is assisted by an additional regulatory complex (known as MACOM, a m6A-METTL-associated complex) composed of WTAP, VIRMA, RBM15/15B, and ZC3H13. WTAP contributes to the heterodimer being located in nuclear speckles to complete m6A modification (21, 22). VIRMA recruits the catalytic core complex METTL3/METTL14/WTAP in the 3′UTR and is near the stop codon to methylate (23). RBM15/15B, as an X-inactive specific transcript-binding protein (XIST-binding protein), is associated with XIST-mediated gene silencing and regulates the m6A modification in XIST (24). ZC3H13 interacts with the m6A machinery and contributes the MTC to the mRNA-specific sites by binding factor Nito (25). ZCCHC4 acts on 28S rRNA by m6A modification and impacts mRNA translation (26, 27). METTL5 is the 18S rRNA m6A methyltransferase (26). MTTL16, a novel methyltransferase, is responsible for modifying the m6A modification of A43 in U6 small nuclear RNA and catalyzing m6A within a hairpin in MAT2A (28) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The process of m6A modification. m6A RNA methylation is regulated by “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers”. MAOCM, m6A-METTL-associated complex, composed of WTAP, VIRMA, RBM15/15B, and ZC3H13.

Because METTL3 plays a critical role in catalytic activity, many studies regarding its biological function in cancers have been widely reported, including lymphoma (29, 30), leukemia (31–33), breast cancer progression (34), liver cancer (35), glioblastoma (36, 37), bladder cancer (38, 39), gastric cancer (40), and lung cancer (41, 42). However, studies on m6A modification in hematology have not been systematically summarized thus far. Therefore, we will mainly focus on the role of METTL3 in normal hematopoiesis and hematological neoplasms in the present review and discuss directions for future research and potential clinical applications of METTL3 in hematological diseases.

METTL3 (also known as MT-A70), a 70-kDa protein, was first identified as a m6A “writer” and is highly conserved in eukaryotes from yeast to human (43). Although METTL3 forms a stable 1:1 heterodimer structure with METTL14 to exert higher methylation activity, it has been identified as the core catalytic enzyme of m6A methylation, and METTL14 mainly plays a role in the structure of MTC stabilization and recognizes target RNAs (20, 24, 44, 45). In contrast to METTL14, METTL3 contains S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-binding protein and its product S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH) in the catalytic pocket, which were not observed in METTL14 (20, 44–46) (Figure 2). In addition, the catalytic site of METTL3 contains a more conserved DPPW motif involved in coordinating the adenine of the acceptor substrate, while METTL14 has a more divergent EPPL sequence (20, 46, 47). After replacing the DPPW motif with APPW(D395) in METTL3, the methylation of the METTL3–METLL14 complex was significantly destroyed but was very lightly affected after changing EPPL to APPL in METTL14 (44). Moreover, due to the collision between the adenine moiety and the side chain (Trp211 and Pro362) residues in METTL14, the binding of SAM would be prevented in the METTL14 catalytic site (46, 48). Furthermore, METTL3 also contains two CYS-CYS-HIS (CCCH)-type zinc binding motifs, which are critical for RNA methylation in vitro (44, 49). The methyltransferase domain of METTL3 (MTD3) presents a classic α–β–α fold, including a mixed eight-strand β-sheet, four α-helices, and three 310 helices, which makes a special catalytic cavity for METTL3, while the catalytic site of METTL14 is relatively occluded (20, 44). The methyltransferase domain of METTL14 (MTD14) contains residues 165–378, which is near the N-terminal α-helical motif (NHM, residues 116–163) and the C-terminal motif (CTM, residues 380–402) (20). MTD3 mainly contains residues 369–570, making three loops to fence the METTL3 catalytic cavity: gate loop 1 (residues 396–410), gate loop 2 (residues 507–515), and interface loop (residues 462–479) (20, 44). The two gate loops are adjacent to the SAM binding site and are associated with adenosine recognition, and the interface loop with the longer sequence allows METTL3 and METTL14 to bind each other tightly (20, 44, 50). Meanwhile, 11 residues of METTL3 are involved in SAM coordination, including D377, I378, Q550, N549, R536, D395, K513, H538, N539, E532, and L533 (20). Wang et al. further found that mutations of these residues completely abrogated methyltransferase activity (D377A, D395A, N539A, and E532A) or moderately weakened enzyme activity (R536, H538, N549, or Q550), while corresponding mutations of METTL14 have little effect on catalytic activity (20, 44). Between the interface of METTL3 and METTL14, a highly conserved groove comprises Arg465, Arg468, His474, and His478 of METTL3 and Arg245, Arg249, Arg254, and Arg255 of METTL14, which contributes to internal RNA binding (20, 46).

Furthermore, METTL3 has also been reported to promote translation independently of its methyltransferase activity or downstream m6A reader proteins (51, 52). The function of METTL3 in the cytoplasm promoting translation is to recruit the initiation factor eIF3 h to the translation initiation complex (51, 52). It can enhance epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and TAZ protein expression independent of YTHDF1.

More recent studies on METTL3 in hematology have been reported, including the function of METTL3 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. METTL3 has been discovered to be associated with differentiation, growth, and apoptosis in both normal and malignant cells. Moreover, it has also been revealed to impact chemoresistance in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which would be a novel potential target molecule in hematological neoplasms. Therefore, we summarized the function of METTL3 in normal hematopoiesis and several hematological malignancies (Table 1).

Normal hematopoiesis plays a vital role in hematology, presenting multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) being differentiated into various mature cells of the blood system. The process is complex and multistep and is regulated by many factors, such as the transcription factor PU.1 for myeloid cells and C/EBPα for granulocyte/macrophage progenitors.

The first populations of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are mainly produced by hemogenic endothelial cells (ECs), which later acquire a cell morphology and gene expression consistent with hematopoietic identity in a process called endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition (EHT) (64). In zebrafish, m6A has been reported to determine cell fate when EHT progresses to the earliest hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) during embryogenesis (14). METTL3 was found to be enriched in sorted endothelial cells and hemogenic endothelium, correspondingly affecting hematopoiesis (14). The deletion of METTL3 results in impaired HSPC differentiation by activating Notch1 signaling. Increasing Notch signaling can abrogate the generation of hematopoietic cells by maintaining endothelial identity in EHT (14, 64). Notch1a m6A enrichment is significantly decreased in METTL3 morphants, but the expression of Notch1a is increased in endothelial cells, resulting in a decrease in HSPC generation (14). Conversely, overexpression of METTL3 inhibiting Notch1 activity could rescue this phenomenon in zebrafish (14). Additionally, the same phenotype was also observed in mice with METTL3 knockdown. In 2018, this team reported that METTL3 promotes HSPC generation by inhibiting Notch1 signaling in endothelial cells of the Vec-Cre; METTL3fl/fl mouse aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region, consistent with the phenomenon in zebrafish (53). In 2019, Heather Lee et al. performed a study on Mx1-cre; METTL3fl/fl mice and discovered that METTL3 deletion has little impact on HSC self-renewal and quiescence but significantly affects HSC differentiation (54). The deletion of METTL3 has resulted in a blocking of HSCs and an accumulation of HSCs by reducing Myc mRNA translation (54). Deleting METTL3 in myeloid cells from Lysm-cre; METTL3fl/fl mice, they found that METTL3 is not indispensable for mature myeloid cell maintenance or function (54). Via Mx1-cre; METTL3fl/fl mice, Cheng et al. reported that METTL3 depletion in normal murine HSCs results in a decrease in Myc mRNA and protein levels. Furthermore, METTL3 is required for normal hematopoiesis and maintains HSC symmetric commitment and identity by controlling Myc abundance in differentiating HSCs and Myc mRNA stability (55). Metll3 ablation can impair the differentiation of myeloid, megakaryocytes, and erythroid lineages, leading to an additional population that molecularly and functionally resembles multipotent progenitors (55). m6A loss by deleting Metll3 in mice blocked HSC transition to myeloid progenitors, notably presenting as decreases in common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and granulocyte myeloid progenitors (GMPs) (55). Meanwhile, they also found a cell-intrinsic role of Metll3 in regulating HSC number and function in a bone marrow competitive transplantation trial (55). In our previous study, we discovered that the METTL3-mettl14 methyltransferase complex plays a vital role in regulating HSC self-renewal in adult mouse bone marrow, and METTL3 is mainly responsible for HSCs being in a quiescent state in mice (56). After conditional knockout of METTL3, Metll14, or both in mice, we found that the depletion of METTL3 is in charge of expanding phenotypic HSCs in adult mouse bone marrow and promotes the HSC cell cycle by regulating HSC self-renewal genes such as Nr4a2, p21, Bmi-1, and Prdm16 (56). In human HSPCs from cord blood, the depletion of METTL3 has been discovered to enhance cell differentiation, inhibit cell proliferation with fewer colony-forming units (CFUs) in all lineages, and hardly affect the apoptosis of HSPCs (31). Additionally, METTL3 absence contributes to myeloid differentiation, and METTL3 mRNA is expressed at lower levels in mature differentiated myeloid cells in both mouse HSCs and HSPCs (31). Taking human erythroleukemia (HEL) cells as a surrogate model for studying erythropoiesis, Kupper et al. also found that METTL3 blocked erythropoiesis by impacting the stage-specific gene expression of erythroid progenitors, such as the erythroid transcription factors GYPA, HBA1, SPTB, EPOR, and ALAS2 (57).

As METTL3 plays a significant role in normal hematopoiesis, an increasing number of studies on hematology malignancies have been reported in recent years, including AML, acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), CML, and lymphomas.

AML is a common hematological malignancy that is mainly caused by gene mutations and chromosomal aberrations resulting in changes in gene expression and, sequentially, aberrant growth and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (65). In 2017, Ly Vu et al. discovered that METTL3 has higher expression in AML cells than in normal HSPCs (31). In addition, they found that METTL3 disruption promotes the differentiation and apoptosis of AML cells both in vitro (MOLM-13 cells) and in vivo, which indicated that METTL3 affects the undifferentiated state and growth of leukemia cell lines (31). By connecting the single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and ribosome profiling, they revealed that MELLT3 deletion reduced the translation efficiency of c-MYC, BCL2, and PTEN in MOLM-13, resulting in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT (PI3K/AKT) pathway activation (31). Meanwhile, Isaia Barbieri reported that METTL3 is necessary for leukemia cell growth and in maintaining an undifferentiated state (32). They further found that METTL3 could be recruited by CEBPZ to promoters, which led to m6A methylation of the respective mRNAs and increased translation. Among the promoters, translation of SP1 was significantly reduced after deleting METTL3 (32). Wang et al. also reported that METTL3 was more highly expressed in immature cells than in mature monocytes, and its depletion significantly inhibited cell proliferation and decreased MYC expression and m6A levels on MYC mRNA (66). Recently, a group of researchers reported that METTL3 plays a role in inhibiting adipogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and blocking the chemoresistance of acute myeloid leukemia cells by regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (58). However, METTL3 expression was significantly decreased in AML-MSCs, which enhanced the adipogenesis and chemoresistance of AML cells (58). They found that METTL3 impacted the m6A modification of AKT1 mRNA, resulting in a decrease in the protein level of AKT1 and an increase in adipogenesis. Correspondingly, activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway contributes to adipogenesis and AML chemoresistance in MSCs (58). In our recent study, we found that METTL3 is highly expressed in AML patients, which results in poorer prognosis than in AML patients without METTL3 expression (p=0.017). Furthermore, knockdown of METTL3 in AML cells (K562 and Kasumi-1) inhibited proliferation and increased apoptosis and differentiation by regulating the p53 signaling pathway. METTL3 deletion led to decreased MDM2 expression and MDM2 mRNA transcript stability, which activated the p53 signaling pathway (59).

CML is caused by the oncogenic BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, which is mainly treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (67). However, TKI resistance is still a challenge for CML patients and increases the risk of transfer to AML (68). In 2018, Zaira Ianniello et al. discovered that METTL3 is a novel oncogene in CML and potentially a therapeutic target for TKI-resistant CML. The m6A methyltransferase complex METTL3/METTL14 and METTL3 is upregulated in primary CML patients, and its downregulation significantly impairs the proliferation of both primary CML cells and TKI-sensitive and TKI-resistant CML cells (60). Silencing METTL3 in K562 cells and the TKI imatinib mesylate-resistant K562 cell line (K562r), they found that METTL3 affects the growth and viability of CML cells directly and indirectly. MYC, as a transcriptional activator, is notably affected by METTL3 in CML cells, including the protein, mRNA, and premRNA levels. METTL3 knockdown strongly reduced MYC expression at multiple levels in CML, which consequently regulated the genes associated with RNA metabolism (60). Moreover, they found that the PES1 protein was potentially involved in blocking the cell cycle in G1 phase after METTL3 knockdown in CML cells (60). They showed that METTL3 both regulates PES1 by methyltransferase activity in the nucleus and directly promotes PES1 translation in the cytoplasm independently of its catalytic activity (60). Lai et al. recently reported that LINC00470 and METTL3 played a role in chemoresistance and autophagy in CML by regulating phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) (61). PTEN, a well-known tumor suppressor, suppresses the activation of PI3K/AKT signaling and subsequently inhibits AKT activity and its downstream pathways (69). In the study, they disclosed that PTEN expression was obviously lower in chemoresistant CML cells than in K562 parental cells, which was negatively associated with LINC00470 and METTL3 (61). More interestingly, they found that overexpression of LINC00470 shortened the half-life of PTEN mRNA and enhanced the binding of METTL3 to PTEN mRNA (61). The depletion of METTL3 in K562 cells reversed the downregulation and degradation of PTEN mRNA and protein induced by LINC00470 and recovered the normal level of m6A modification in PTEN (61). Accordingly, overexpression of METTL3/LINC00470 promoted chemoresistance and reduced autophagy in CML cells by regulating PTEN stability and activating AKT. Fang-Yi Yao et al. reported that METTL3 was downregulated in CML cells, resulting in a decrease in the protein level of nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) (70). Furthermore, METTL3 downregulation in CMLs reduced its ability to modify NETA1 m6A, subsequently enhancing CML cell viability and inhibiting CML cell apoptosis. NEAT1, a lncRNA, is crucial for composing the subnuclear structure paraspeckle and is associated with the progression of hematological malignancies (62).

Lymphocytic neoplasm comprises lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. Similar to AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is also a severe hematology malignancy and is the most common form of cancer in children (71). However, studies on m6A modification in ALL are significantly fewer than those in AML. Congcong Sun et al. reported that the expression of METTL3 was lower in children with ETV6-RUNX1-positive ALL (63). Meanwhile, they also found that the METTL3 expression level was reduced in ALL relapse patients compared with non-relapse patients (63). However, they did not find any correlation between METTL3 expression and some basic clinical characteristics, including age, sex, initial white blood cell count, blast percentage, and LDH level (63). In 2021, a five-center case–control study reported that METLL3 gene polymorphisms were strongly associated with pediatric ALL, mainly including rs1263801 C>G, rs1139130 A>G, and rs1061027 A>C polymorphisms (33). All three polymorphisms were reported to remarkably increase the risk of common B-type and MLL fusion-type ALL in southern Chinese children (33). Additionally, all three polymorphisms were also related to primitive/naive lymphocytes and MRD after chemotherapy. The study showed that patients carrying rs1263801 CC and rs1139130 AA would have a better response to South China Children Leukemia Group chemotherapeutics (SCCLG) chemotherapeutics, and Chinese Children Cancer Group Chemotherapeutics (CCCG) chemotherapeutics are more efficient for patients with rs1061027 (33).

Lymphoma is a well-known hematological neoplasm that mainly includes Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common neoplasm in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which is an aggressive lymphoma with a median survival of <1 year in untreated patients (72). A study regarding the correlation of m6A modifications with DLBCL reported that the expression level of METTL3 is higher in DLBCL tissues/cell lines than in normal lymph nodes/cells (29). Additionally, higher expression of METTL3 facilitates the proliferation of DLBCL cell lines and viability by regulating the m6A mRNA modification of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), which was usually regarded as inhibitor of canonical Wnt signaling in previous studies (73, 74). Subsequently, they found that overexpression of PEDF can disable the inhibitory effects of METTL3 silencing on DLBCL cell proliferation (29). These results suggest that the METTL3/PEDF axis may have therapeutic potential for DLBCL, but more specific studies are needed for verification.

METTL3 expression is significantly different in different tumors. The above discussion indicates that METTL3 plays a vital role in both normal hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies, including their self-renewal and differentiation. METTL3 knockdown can destroy HSPC differentiation and HSC symmetric commitment by regulating Myc and Notch1a m6A modification (14, 54, 55). Despite the discrepancy in METTL3 expression levels in different hematological malignancies, METTL3 is upregulated in most tumor tissues and cell lines and is involved in disease progression and the maintenance of a cancer cell undifferentiated state. Higher expression of METTL3 in AML is critical to maintain the undifferentiation of AML cells, promote the growth of AML cells, and inhibit AML cell apoptosis (31, 32, 66). In CML, TKI resistance always makes it more difficult to cure patients with CML, while METTL3 has been found to affect the apoptosis, proliferation, and viability of CML cells with higher expression (60, 61, 68, 70). More importantly, METTL3 depletion notably damages the proliferation of primary CML cells and TKI-resistant CML cells, which suggests that METTL3 inhibitors may have novel potential to cure TKI-resistant CML patients. Similarly, the expression level of METTL3 in DLBCL tissues and cell lines is higher than that in normal lymph nodes and cells, which promotes the proliferation of DLBCL cell lines and viability by governing PEDF (29). In contrast, METTL3 has also been discovered to be downregulated in CML, and it decreases NEAT1 m6A modification to impact CML viability and apoptosis (62). Likewise, ALL children with ETV6-RUNX1 positivity had lower METTL3 expression than normal children.

Due to the further understanding of m6A modification, associated molecular inhibitors have been produced and studied, such as the FTO and METTL3 molecules. Molecular inhibitors of FTO, including meclofenamic acid (MA), MA2, FB23-2, and FB23, have been produced and studied (75–77). Among them, FB23-2 inhibits growth and promotes the differentiation/apoptosis of AML cells both in vitro and in vivo [patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model] (77). Similar to molecular inhibitors of FTO, METTL3 molecule inhibitors have also been produced and studied in vitro and vivo, especially in hematology malignances. STM2457 is a highly potent inhibitor of METTL3 with an IC50 of 16.9 nM, and it performs a cofactor competitive mode using SAM in surface plasmon resonance, avoiding the homocysteine binding pocket used by SAM (78). STM2457 has been verified to block both human AML cell lines (MOLM-13) and proliferation and colony-forming ability potential and promote differentiation and apoptosis, whereas it has no impact on normal hematopoiesis (78). Furthermore, STM2457 application in AML cells significantly reduced the m6A modification of several mRNAs associated with AML. Among these mRNAs, SP1 and BRD4, which are known to be governed by METTL3, were obviously decreased upon treating MOLM-13 cells with STM2457 (78). Consistent with the in vitro results, the inhibition of METTL3 function by STM2457 was also verified in vivo. STM2457 can prevent AML expansion and impair leukemia stem cells in both a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model and a primary mouse MLL-AF9/Flt3itd/+ model (78). Another METTL3-selective inhibitor, UZH1a, a high-nanomolar inhibitor, occupies the SAM binding site of METTL3, similar to STM2457 (79). UZH1a could also result in a decrease in the mRNA m6A methylation level in AML MOLM-13 cells in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 of 7 µM) (79). Furthermore, this group also confirmed that UZH1a could reduce mRNA m6A/A levels not only in the leukemia cell line MOLM-13 but also in other cell lines (osteosarcoma U2OS cells and immortalized human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T).

Increasing studies have identified that m6A RNA modifications notably influence physiological and pathological processes in eukaryotes by regulating RNA translation, degradation, stability, export, and splicing. Meanwhile, many recent emerging studies have revealed that m6A RNA modifications play critical roles in various cancers, including cervical cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, leukemia, lymphoma, glioblastoma, lung cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and bladder cancer. Therefore, more attention should be given to the function of m6A modification in tumorigenesis, which would provide more suitable therapies for patients.

In the reversible and dynamic m6A process, METTL3, with a special structure, is the core methyltransferase involved in m6A modification. It plays a vital role in many biological processes, including cell differentiation, proliferation, viability, apoptosis, cycle, invasion, inflammatory response, and metabolism (80). Moreover, it has also been reported that METTL3 in the cytoplasm can promote translation independently of its methyltransferase activity (51). Meanwhile, recent studies have revealed that METTL3 impacts biological processes in both normal and malignant hematopoiesis. METTL3 not only influences normal and symmetric HSPC/HSC differentiation, HSPC self-renewal, and colony formation ability in normal hematopoiesis but also affects leukemia cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, chemoresistance, and a higher risk of specific ALL or lymphoma. Therefore, the initial mechanisms of METTL3 in hematological biology and disease require further exploration, subsequently revealing the relationship between them and providing a foundation for producing potential inhibitors. However, the role of other members of the m6A process, such as methyltransferases and demethyltransferases, should also be considered in tumorigenesis. Undoubtedly, the deeper the understanding of m6A modification, the more inhibitors will be produced. Similar to FTO inhibitors, METTL3 inhibitors have been produced and studied in recent years, and they will be a potent potential target to treat patients with hematological malignancies in the future, especially AML and chemoresistant CML.

Collectively, METTL3 plays a vital role in both normal and malignant hematopoiesis, while its studies are still in a very early stage. Therefore, further studies are required to explore the mechanism, hoping to optimize a potential targeted METTL3 therapy and use it widely in clinical practice in the future.

XW and YG wrote and revised the manuscript. WY drafted the pictures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The study was supported by the Foundation of the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (No. 2019YFS0026).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We sincerely thank all workers who contributed to this study.

1. Jiang X, Liu B, Nie Z, Duan L, Xiong Q, Jin Z, et al. The Role of M6a Modification in the Biological Functions and Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2021) 6(1):74. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00450-x

2. Jones PA, Issa JP, Baylin S. Targeting the Cancer Epigenome for Therapy. Nat Rev Genet (2016) 17(10):630–41. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.93

3. Deng X, Su R, Weng H, Huang H, Li Z, Chen J. RNA N(6)-Methyladenosine Modification in Cancers: Current Status and Perspectives. Cell Res (2018) 28(5):507–17. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0034-6

4. Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of Methylated Nucleosides in Messenger RNA From Novikoff Hepatoma Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (1974) 71(10):3971–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971

5. Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in Nuclear RNA Is a Major Substrate of the Obesity-Associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol (2011) 7(12):885–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687

6. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the Human and Mouse M6a RNA Methylomes Revealed by M6a-Seq. Nature (2012) 485(7397):201–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11112

7. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase That Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol Cell (2013) 49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015

8. Ueda Y, Ooshio I, Fusamae Y, Kitae K, Kawaguchi M, Jingushi K, et al. AlkB Homolog 3-Mediated tRNA Demethylation Promotes Protein Synthesis in Cancer Cells. Sci Rep (2017) 7:42271. doi: 10.1038/srep42271

9. Alarcón CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of M(6)A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell (2015) 162(6):1299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011

10. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, et al. N(6)-Methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell (2015) 161(6):1388–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014

11. Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, Chen YS, Hao YJ, Sun BF, et al. Nuclear M(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol Cell (2016) 61(4):507–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012

12. Hsu PJ, Zhu Y, Ma H, Guo Y, Shi X, Liu Y, et al. Ythdc2 Is an N(6)-Methyladenosine Binding Protein That Regulates Mammalian Spermatogenesis. Cell Res (2017) 27(9):1115–27. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.99

13. Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, et al. YTHDF3 Facilitates Translation and Decay of N(6)-Methyladenosine-Modified RNA. Cell Res (2017) 27(3):315–28. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.15

14. Zhang C, Chen Y, Sun B, Wang L, Yang Y, Ma D, et al. M(6)A Modulates Haematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Specification. Nature (2017) 549(7671):273–6. doi: 10.1038/nature23883

15. Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu H, et al. Recognition of RNA N(6)-Methyladenosine by IGF2BP Proteins Enhances mRNA Stability and Translation. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20(3):285–95. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z

16. Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, et al. N6-Methyladenosine-Dependent Regulation of Messenger RNA Stability. Nature (2014) 505(7481):117–20. doi: 10.1038/nature12730

17. Shen H, Lan Y, Zhao Y, Shi Y, Jin J, Xie W. The Emerging Roles of N6-Methyladenosine RNA Methylation in Human Cancers. biomark Res (2020) 8:24. doi: 10.1186/s40364-020-00203-6

18. Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N(6)-Methyladenosine-Dependent RNA Structural Switches Regulate RNA-Protein Interactions. Nature (2015) 518(7540):560–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14234

19. Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell (2017) 169(7):1187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045

20. Wang X, Feng J, Xue Y, Guan Z, Zhang D, Liu Z, et al. Structural Basis of N(6)-Adenosine Methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 Complex. Nature (2016) 534(7608):575–8. doi: 10.1038/nature18298

21. Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang WJ, et al. Mammalian WTAP Is a Regulatory Subunit of the RNA N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase. Cell Res (2014) 24(2):177–89. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3

22. Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Wang T, Maciag K, Bushkin GG, et al. Perturbation of M6a Writers Reveals Two Distinct Classes of mRNA Methylation at Internal and 5’ Sites. Cell Rep (2014) 8(1):284–96. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.048

23. Yue Y, Liu J, Cui X, Cao J, Luo G, Zhang Z, et al. VIRMA Mediates Preferential M(6)A mRNA Methylation in 3’UTR and Near Stop Codon and Associates With Alternative Polyadenylation. Cell Discov (2018) 4:10. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0019-0

24. Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 Complex Mediates Mammalian Nuclear RNA N6-Adenosine Methylation. Nat Chem Biol (2014) 10(2):93–5. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432

25. Knuckles P, Lence T, Haussmann IU, Jacob D, Kreim N, Carl SH, et al. Zc3h13/Flacc Is Required for Adenosine Methylation by Bridging the mRNA-Binding Factor Rbm15/Spenito to the M(6)A Machinery Component Wtap/Fl(2)d. Genes Dev (2018) 32(5-6):415–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.309146.117

26. van Tran N, Ernst FGM, Hawley BR, Zorbas C, Ulryck N, Hackert P, et al. The Human 18S rRNA M6a Methyltransferase METTL5 Is Stabilized by TRMT112. Nucleic Acids Res (2019) 47(15):7719–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz619

27. Pinto R, Vågbø CB, Jakobsson ME, Kim Y, Baltissen MP, O’Donohue MF, et al. The Human Methyltransferase ZCCHC4 Catalyses N6-Methyladenosine Modification of 28S Ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48(2):830–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1147

28. Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Hackert P, Lenz C, Urlaub H, Höbartner C, et al. Human METTL16 Is a N(6)-Methyladenosine (M(6)A) Methyltransferase That Targets pre-mRNAs and Various Non-Coding RNAs. EMBO Rep (2017) 18(11):2004–14. doi: 10.15252/embr.201744940

29. Cheng Y, Fu Y, Wang Y, Wang J. The M6a Methyltransferase METTL3 Is Functionally Implicated in DLBCL Development by Regulating M6a Modification in PEDF. Front Genet (2020) 11:955. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00955

30. Ma H, Shen L, Yang H, Gong H, Du X, Li J. M6a Methyltransferase Wilms’ Tumor 1-Associated Protein Facilitates Cell Proliferation and Cisplatin Resistance in NK/T Cell Lymphoma by Regulating Dual-Specificity Phosphatases 6 Expression via M6a RNA Methylation. IUBMB Life (2021) 73(1):108–17. doi: 10.1002/iub.2410

31. Vu LP, Pickering BF, Cheng Y, Zaccara S, Nguyen D, Minuesa G, et al. The N(6)-Methyladenosine (M(6)A)-Forming Enzyme METTL3 Controls Myeloid Differentiation of Normal Hematopoietic and Leukemia Cells. Nat Med (2017) 23(11):1369–76. doi: 10.1038/nm.4416

32. Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, Shi J, Millán-Zambrano G, Robson SC, et al. Promoter-Bound METTL3 Maintains Myeloid Leukaemia by M(6)A-Dependent Translation Control. Nature (2017) 552(7683):126–31. doi: 10.1038/nature24678

33. Liu X, Huang L, Huang K, Yang L, Yang X, Luo A, et al. Novel Associations Between METTL3 Gene Polymorphisms and Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Five-Center Case-Control Study. Front Oncol (2021) 11:635251. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.635251

34. Wang H, Xu B, Shi J. N6-Methyladenosine METTL3 Promotes the Breast Cancer Progression via Targeting Bcl-2. Gene (2020) 722:144076. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.144076

35. Liu L, Wang J, Sun G, Wu Q, Ma J, Zhang X, et al. M(6)A mRNA Methylation Regulates CTNNB1 to Promote the Proliferation of Hepatoblastoma. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1119-7

36. Visvanathan A, Patil V, Arora A, Hegde AS, Arivazhagan A, Santosh V, et al. Essential Role of METTL3-Mediated M(6)A Modification in Glioma Stem-Like Cells Maintenance and Radioresistance. Oncogene (2018) 37(4):522–33. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.351

37. Li F, Yi Y, Miao Y, Long W, Long T, Chen S, et al. N(6)-Methyladenosine Modulates Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay in Human Glioblastoma. Cancer Res (2019) 79(22):5785–98. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-2868

38. Cheng M, Sheng L, Gao Q, Xiong Q, Zhang H, Wu M, et al. The M(6)A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Bladder Cancer Progression via AFF4/NF-κb/MYC Signaling Network. Oncogene (2019) 38(19):3667–80. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0683-z

39. Han J, Wang JZ, Yang X, Yu H, Zhou R, Lu HC, et al. METTL3 Promote Tumor Proliferation of Bladder Cancer by Accelerating Pri-Mir221/222 Maturation in M6a-Dependent Manner. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1036-9

40. Yue B, Song C, Yang L, Cui R, Cheng X, Zhang Z, et al. METTL3-Mediated N6-Methyladenosine Modification Is Critical for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Metastasis of Gastric Cancer. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1065-4

41. Jin D, Guo J, Wu Y, Du J, Yang L, Wang X, et al. M(6)A mRNA Methylation Initiated by METTL3 Directly Promotes YAP Translation and Increases YAP Activity by Regulating the MALAT1-miR-1914-3p-YAP Axis to Induce NSCLC Drug Resistance and Metastasis. J Hematol Oncol (2021) 14(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01048-8

42. Wang H, Deng Q, Lv Z, Ling Y, Hou X, Chen Z, et al. N6-Methyladenosine Induced miR-143-3p Promotes the Brain Metastasis of Lung Cancer via Regulation of VASH1. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1108-x

43. Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA Cloning of the AdoMet-Binding Subunit of the Human mRNA (N6-Adenosine)-Methyltransferase. Rna (1997) 3(11):1233–47.

44. Wang P, Doxtader KA, Nam Y. Structural Basis for Cooperative Function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 Methyltransferases. Mol Cell (2016) 63(2):306–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041

45. Zhou KI, Pan T. Structures of the M(6)A Methyltransferase Complex: Two Subunits With Distinct But Coordinated Roles. Mol Cell (2016) 63(2):183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.005

46. Śledź P, Jinek M. Structural Insights Into the Molecular Mechanism of the M(6)A Writer Complex. Elife (2016) 5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18434

47. Bujnicki JM, Feder M, Radlinska M, Blumenthal RM. Structure Prediction and Phylogenetic Analysis of a Functionally Diverse Family of Proteins Homologous to the MT-A70 Subunit of the Human mRNA:M(6)A Methyltransferase. J Mol Evol (2002) 55(4):431–44. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2339-8

48. Zhou H, Yin K, Zhang Y, Tian J, Wang S. The RNA M6a Writer METTL14 in Cancers: Roles, Structures, and Applications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer (2021) 1876(2):188609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188609

49. Hall TM. Multiple Modes of RNA Recognition by Zinc Finger Proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol (2005) 15(3):367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.04.004

50. Goedecke K, Pignot M, Goody RS, Scheidig AJ, Weinhold E. Structure of the N6-Adenine DNA Methyltransferase M.TaqI in complex with DNA and a cofactor analog. Nat Struct Biol (2001) 8(2):121–5. doi: 10.1038/84104

51. Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI. The M(6)A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Translation in Human Cancer Cells. Mol Cell (2016) 62(3):335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.021

52. Choe J, Lin S, Zhang W, Liu Q, Wang L, Ramirez-Moya J, et al. mRNA Circularization by METTL3-Eif3h Enhances Translation and Promotes Oncogenesis. Nature (2018) 561(7724):556–60. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0538-8

53. Lv J, Zhang Y, Gao S, Zhang C, Chen Y, Li W, et al. Endothelial-Specific M(6)A Modulates Mouse Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Development via Notch Signaling. Cell Res (2018) 28(2):249–52. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.143

54. Lee H, Bao S, Qian Y, Geula S, Leslie J, Zhang C, et al. Stage-Specific Requirement for Mettl3-Dependent M(6)A mRNA Methylation During Haematopoietic Stem Cell Differentiation. Nat Cell Biol (2019) 21(6):700–9. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0318-1

55. Cheng Y, Luo H, Izzo F, Pickering BF, Nguyen D, Myers R, et al. M(6)A RNA Methylation Maintains Hematopoietic Stem Cell Identity and Symmetric Commitment. Cell Rep (2019) 28(7):1703–16.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.032

56. Yao QJ, Sang L, Lin M, Yin X, Dong W, Gong Y, et al. Mettl3-Mettl14 Methyltransferase Complex Regulates the Quiescence of Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Res (2018) 28(9):952–4. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0062-2

57. Kuppers DA, Arora S, Lim Y, Lim AR, Carter LM, Corrin PD, et al. N(6)-Methyladenosine mRNA Marking Promotes Selective Translation of Regulons Required for Human Erythropoiesis. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):4596. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12518-6

58. Pan ZP, Wang B, Hou DY, You RL, Wang XT, Xie WH, et al. METTL3 Mediates Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Adipogenesis to Promote Chemoresistance in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. FEBS Open Bio (2021) 11(6):1659–72. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.13165

59. Sang L, Wu X, Yan T, Naren D, Liu X, Zheng X, et al. The M(6)A RNA Methyltransferase METTL3/METTL14 Promotes Leukemogenesis Through the Mdm2/P53 Pathway in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Cancer (2022) 13(3):1019–30. doi: 10.7150/jca.60381

60. Ianniello Z, Sorci M, Ceci Ginistrelli L, Iaiza A, Marchioni M, Tito C, et al. New Insight Into the Catalytic -Dependent and -Independent Roles of METTL3 in Sustaining Aberrant Translation in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Death Dis (2021) 12(10):870. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04169-7

61. Lai X, Wei J, Gu XZ, Yao XM, Zhang DS, Li F, et al. Dysregulation of LINC00470 and METTL3 Promotes Chemoresistance and Suppresses Autophagy of Chronic Myelocytic Leukaemia Cells. J Cell Mol Med (2021) 25(9):4248–59. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16478

62. Gao C, Zhang J, Wang Q, Ren C. Overexpression of lncRNA NEAT1 Mitigates Multidrug Resistance by Inhibiting ABCG2 in Leukemia. Oncol Lett (2016) 12(2):1051–7. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4738

63. Sun C, Chang L, Liu C, Chen X, Zhu X. The Study of METTL3 and METTL14 Expressions in Childhood ETV6/RUNX1-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Mol Genet Genomic Med (2019) 7(10):e00933. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.933

64. Lizama CO, Hawkins JS, Schmitt CE, Bos FL, Zape JP, Cautivo KM, et al. Repression of Arterial Genes in Hemogenic Endothelium Is Sufficient for Haematopoietic Fate Acquisition. Nat Commun (2015) 6:7739. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8739

65. Short NJ, Rytting ME, Cortes JE. Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Lancet (2018) 392(10147):593–606. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31041-9

66. Wang XS, He JR, Yu S, Yu J. [Methyltransferase-Like 3 Promotes the Proliferation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells by Regulating N6-Methyladenosine Levels of MYC]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao (2018) 40(3):308–14. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2018.03.002

67. Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, O’Brien S, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM. The Biology of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med (1999) 341(3):164–72. doi: 10.1056/nejm199907153410306

68. Corbin AS, Agarwal A, Loriaux M, Cortes J, Deininger MW, Druker BJ. Human Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells Are Insensitive to Imatinib Despite Inhibition of BCR-ABL Activity. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(1):396–409. doi: 10.1172/jci35721

69. Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The Functions and Regulation of the PTEN Tumour Suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2012) 13(5):283–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330

70. Yao FY, Zhao C, Zhong FM, Qin TY, Wen F, Li MY, et al. M(6)A Modification of lncRNA NEAT1 Regulates Chronic Myelocytic Leukemia Progression via miR-766-5p/CDKN1A Axis. Front Oncol (2021) 11:679634. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.679634

71. Wu C, Li W. Genomics and Pharmacogenomics of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2018) 126:100–11. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.04.002

72. Flowers CR, Sinha R, Vose JM. Improving Outcomes for Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. CA Cancer J Clin (2010) 60(6):393–408. doi: 10.3322/caac.20087

73. Gong J, Belinsky G, Sagheer U, Zhang X, Grippo PJ, Chung C. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) Blocks Wnt3a Protein-Induced Autophagy in Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasms. J Biol Chem (2016) 291(42):22074–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.729962

74. Protiva P, Gong J, Sreekumar B, Torres R, Zhang X, Belinsky GS, et al. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) Inhibits Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in the Liver. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol (2015) 1(5):535–549.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.06.006

75. Huang Y, Yan J, Li Q, Li J, Gong S, Zhou H, et al. Meclofenamic Acid Selectively Inhibits FTO Demethylation of M6a Over ALKBH5. Nucleic Acids Res (2015) 43(1):373–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1276

76. Cui Q, Shi H, Ye P, Li L, Qu Q, Sun G, et al. M(6)A RNA Methylation Regulates the Self-Renewal and Tumorigenesis of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell Rep (2017) 18(11):2622–34. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.059

77. Huang Y, Su R, Sheng Y, Dong L, Dong Z, Xu H, et al. Small-Molecule Targeting of Oncogenic FTO Demethylase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell (2019) 35(4):677–691.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.03.006

78. Yankova E, Blackaby W, Albertella M, Rak J, De Braekeleer E, Tsagkogeorga G, et al. Small-Molecule Inhibition of METTL3 as a Strategy Against Myeloid Leukaemia. Nature (2021) 593(7860):597–601. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03536-w

79. Moroz-Omori EV, Huang D, Kumar Bedi R, Cheriyamkunnel SJ, Bochenkova E, Dolbois A, et al. METTL3 Inhibitors for Epitranscriptomic Modulation of Cellular Processes. ChemMedChem (2021) 16(19):3035–43. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100291

Keywords: METTL3, N6-methyladenosine, normal hematopoiesis, malignant hematopoiesis, inhibitor

Citation: Wu X, Ye W and Gong Y (2022) The Role of RNA Methyltransferase METTL3 in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. Front. Oncol. 12:873903. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.873903

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 23 March 2022;

Published: 28 April 2022.

Edited by:

Swami P. Iyer, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Chunming Cheng, The Ohio State University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Wu, Ye and Gong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuping Gong, Z29uZ3l1cGluZzIwMTBAYWxpeXVuLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.