- 1Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA, United States

- 2Khoury College of Computer Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, United States

- 3Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

- 4Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 5Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 6Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, United States

Editorial on the Research Topic

Disparities in Cancer Prevention and Epidemiology

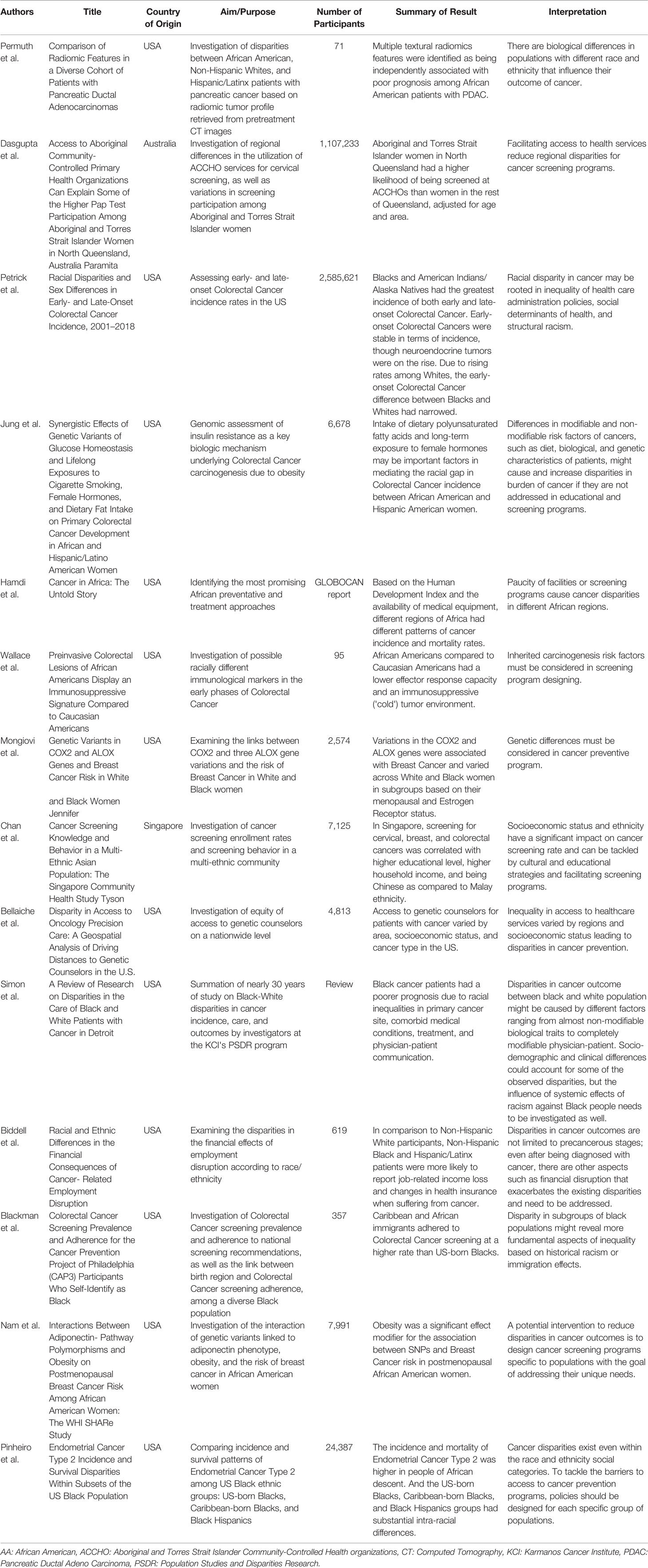

There were 23.6 million new cancer cases in 2019 in the world, causing 10 million deaths and 250 million disability-adjusted life years (1). The burden of the cancer has dramatically increased since 2010 such that cancer new cases, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years increased by 26.3%, 20.9%, and 16.0%, respectively, in 2019 (1). The largest percentage increases have occurred in the low and low-middle socio-demographic index quintiles, suggesting inequal distributions of cancer cases and burden in different populations. Therefore, not only we generally need to improve cancer prevention and control, but we should also aim to make efforts to address inequal burden of cancer among different groups of patients (1). To do so, Disparities in Cancer Prevention and Epidemiology Research Topic in Frontiers in Oncology journal attempted to understand the coordinates and causes of the existing disparities in cancer prevention and distribution in groups of patients with the goal of tackling the by means of of evidence-informed and population-specific policy making. Table 1 provides a summary of the articles in this Research Topic.

This Research Topic was established because although there are considerable number of effective and efficient preventive strategies for many types of cancers, still some populations are severely and unequally suffering from cancer. These preventive strategies and practices consist of, but are not limited to, preventing exposure to identified carcinogens, risk factor management, vaccination against cancer, screening for subclinical incidence, and early detection of the clinically present cancers. But these programs are not equally and equitably helping patients in different populations. A part of the unequal benefit of these interventions for different groups of patients is due to patients' biophysical attributes and their differences in the likelihood of developing cancer and the prognosis (2). Nevertheless, the existing disparities among patient populations are mainly caused by inequalities in cancer prevention and care and other related aspects of healthcare rather than biological differences in patients. The followings depict the steps of care in which different factors cause the discussed disparities.

The first stage of cancer prevention is individuals becoming aware that if they belong to high-risk groups for a cancer, they need to be screened for it. Therefore, a potential point of intervention to address inequalities in cancer prevention and care is to increase public awareness of screening programs or vaccination and emphasize their importance in groups of patients who are not appropriately utilizing preventive and screening services. The strategies and interventions should be designed to create a comprehensive understanding of screening in populations according to their differential background, education, gender, race, ethnicity, culture, and socioeconomic status. And these interventions should be tailored to specific needs of each patient group. As an example, and in this Research Topic, Chan et al. showed that the ever-screened rates for cervical and breast cancer improved in parallel with increasing the screening knowledge in Singapore (cervical, 70.1 vs. 77.1%; breast, 54.2 vs. 75.2%), indicating the role of awareness in preventive service utilization. However, the outcome of increasing people’s knowledge varied depending on their socioeconomic status and ethnicity which directly supports the argument that each population should have their own intervention uniquely designed.

Having perceived the need, the second stage in cancer prevention is utilizing the preventive healthcare service. Regarding preventive care utilization, we first need to understand where the disparities are coming from and what the barriers to care equity are. Differences in perceived benefits and costs of preventive care is one of the factors that cause unequal access to care. Individuals make the decision to utilize a cancer prevention service by comparing the perceived costs and benefits of a service. And these perceptions are influenced by different factors including their socioeconomic status and financial support (3). Therefore, the costs and benefits of services are not just a matter of objective assessments. Services with exactly similar estimated costs could extremely differ in the cost that patients in different bio-socio-economic groups perceive them. Chan et al. supported this concern and reported that poor understanding of the screening procedure, fear of pain and diagnosis, and scheduling difficulty limit preventive service utilization because these factors increase the patients' perceived cost of screening. To elaborate, a group of patients perceived the preventive service to be more costly and less beneficial than others not because the costs of the service were higher for them or they objectively would benefit less from the care. But because that group of patients did not have appropriate familiarity with the preventive care and the fear of pain, for example, increased their perceived cost.

By studying and identifying what contributes to the perceived costs and benefits of screening in different populations, policies could be particularly designed for each population and effectively address their unique needs. As an illustration, the population in Chan et al. study would benefit most from interventions that address their fear and knowledge of screening while Dasgupta et al. study population need physically closer healthcare provision centers to decrease their perceived cost of care. No matter how much we decrease the fear of pain in the population studied by Dasgupta et al., they still cannot afford to travel the distance and utilize the care. Taken together, the goals of each promising intervention such as social network-based policies, could only be realized if the policy incorporates unique features of the patients' social lives and understand their special needs and barriers (4).

As we previously and slightly discussed, the percevied benefits and costs of care also depend on the accessibility and quality of the preventive care. Human resources, such as professional health care workers, healthcare facilities, and access to necessary technologies are important for cancer patients’ preventive care and they must be equitably distributed. Namely, in this Research Topic, Hamdi et al. showed that there is a huge gap in access to relatively simplest types of preventive care in different populations. They reported that in Western, Eastern, and Central African regions, the higher mortality rate of the most preventable cancers like breast, cervical, and prostate cancer is in tandem with the paucity of facilities or screening programs compared to Northern and Southern settings. And it is worth noting that the preventable services of these cancers are among the most easily accessible and affordable types of care in their setting. Bellaiche et al. also supported this notion by showing that access to a high-quality genetic consult for precision medicine depends on where a patient lives in the United States, indicating that even in a developed country not all patients face similar costs of care. And finally, Dasgupta et al. showed that a great proportion of the existing disparities in preventive care in indigenous women could be addressed/resolved by improving their access to primary health care, supporting the importance of understanding the unique needs of each group of patients.

Population-specific policy design is also important for patients. As an instance populations differ in how much burden their diagnosed cancer could cause them. For example, in some instances, the higher burden of cancer in a group of patients is due to lower acceptability of cancer-related programs and, thus, increasing the acceptability of the provided healthcare services could help to narrow the gap in burden of cancer for different patients. In agreement with this, Chan et al. showed that patients’ and physicians’ linguistic and ethnic concordance significantly improved healthcare service efficiency. Additionally, some populations are hit harder by cancer and require more protecting interventions. As an illustration, Biddell et al. showed that cancer’s cost is different for patients of the non-Hispanic black race, compared to patients of the non-Hispanic white race. Black patients in their study were more likely to lose their income and insurance after being diagnosed with cancer. And while non-Hispanic black patients were diagnosed with more aggressive cancers that required more expensive treatment, their employment flexibility and income were significantly limited compared to non-Hispanic white patients.

As of now, we realized how different factors in each step of healthcare utilization could have contributed to the existing disparities. Nevertheless, some might argue that a great proportion of disparities are caused by factors such as age, gender, race, and ethnicity of patients that are non-modifiable. We argue that healthcare systems can still ameliorate the disparities in cancer prevention and care through the modifiable factors or providing more and specifically designed care to those who are more likely to experience higher cancer burdens due to non-modifiable risk factors (Nam et al., Jung et al.). The changes that target the modifiable contributors to disparities in cancer burden include the inequalities that are rooted in factors such as, but not limited to, racioethnic discriminations. For example, Pinheiro et al. and Blackman et al. showed that there are disparities in cancer incidence and screening even among the Black population of the US that might be due to some historical racism or immigration effects. This study, per se, enlightens that racism, an example of a modifiable factor, could be used as a point of intervention to address disparities in cancer burden. The modifiable factors could also consist of biophysical conditions of patients. For example, Simon et al. showed that chronic kidney diseases, as preventable comorbidities, were more prevalent at the time of diagnosis and had a more significant adverse impact on renal cell carcinoma incidence in black patients than in white patients. Therefore, by designing prevention strategies that target chronic kidney diseases in black patients, we could decrease the black patients' burden of renal cell carinoma which is higher than white patients. And as previously discussed, even for non-modifiable factors, decision makers could design policies to more intensively help patients with a higher bio-physical probability of being diagnosed with cancer or suffering from more aggressive cancers with the hope of closing the gaps of cancer's burden between different populations. Accordingly, Simon et al., Wallace et al., and Mongiovi et al. showed that Black women in the United States are more likely to be diagnosed with more aggressive breast tumors or different immune responses in colorectal cancer, resulting in a higher incidence and mortality rate. Permuth et al. also demonstrated that some specific radiologic biomarkers for pancreatic cancer have only been reported in African Americans, not non-Hispanic white Americans or Hispanic/Latinx, indicating racial biological variations. To provide an example of what the goal of this Research Topic is and how it could be realized, we argue that these two studies suggest a potential point of intervention to address inequalities in cancer burden: more aggressively screening Black women for breast cancer and taking extra care of Black women with diagnosed breast cancer and all African Americans with pancreatic cancer. Therefore, a part of the gap in cancer burden could be closed by deliberately providing more care to more vulnerable populations. Taken together, care for cancer prevention and burden has multiple stages and each could be a point of intervention to control modifiable factors in more suffering patients or provide extra attention and support to patients with non-modifiable factors that make them more vulnerable to cancer and cause them to experience higher burdens.

All in all, this Research Topic presented a non-comprehensive but enlightening collection of research studies on the disparities in cancer prevention and epidemiology and it shed light on the aspects of cancer care that are potential fields for further exploration. Therefore, the reported results could be directly used for popultion-specific and effective intervention designs. Or the studies could serve as a guide for future investigations. This is particularly important because this Research Topic revealed that there is an absolute need for more research that provides thorough understanding of the life course of cancer patients in different biological, social, and economic groups. This information could help policy makers and researchers to understand what the contributing factors to the existing inequalties in cancer prevention, epidemiology, and burden are and how they could tackle these inequalities through population-specific studies and policy designs.

Author Contributions

FMon and HK drafted the manuscript and incorporated the ideas of all authors. BM provided comments and approved of the final version. FMoh devised the idea, supervised the drafting, and finalized the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Kocarnik JM, Compton K, Dean FE, Fu W, Gaw BL, Harvey JD, et al. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol (2022) 8(3):420–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6987

2. Pomerantz MM, Freedman ML. The Genetics of Cancer Risk. Cancer J (Sudbury Mass) (2011) 17(6):416–22. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31823e5387

3. Biddell CB, Spees LP, Smith JS, Brewer NT, Des Marais AC, Sanusi BO, et al. Perceived Financial Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Cost Burden Among Low-Income, Under-Screened Women. J Womens Health (2021) 30(9):1243–52. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8807

Keywords: cancer prevention, cancer epidemiology, disparities, inequality, gender disparities, racial disparities, socioeconomic disparities, population-specific

Citation: Montazeri F, Komaki H, Mohebi F, Mohajer B, Mansournia MA, Shahraz S and Farzadfar F (2022) Editorial: Disparities in Cancer Prevention and Epidemiology. Front. Oncol. 12:872051. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.872051

Received: 09 February 2022; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 01 June 2022.

Edited and reviewed by:

Dana Kristjansson, Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), NorwayCopyright © 2022 Montazeri, Komaki, Mohebi, Mohajer, Mansournia, Shahraz and Farzadfar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Farnam Mohebi, ZmFybmFtLm1vaGViaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Fateme Montazeri1†

Fateme Montazeri1† Hamidreza Komaki

Hamidreza Komaki Farnam Mohebi

Farnam Mohebi Bahram Mohajer

Bahram Mohajer Mohammad Ali Mansournia

Mohammad Ali Mansournia Saeid Shahraz

Saeid Shahraz Farshad Farzadfar

Farshad Farzadfar