- 1Department of Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- 2Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have exhibited promising efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but the response occurs in only a minority of patients. In clinic, biomarkers such as TMB (tumor mutation burden) and PD-L1 (programmed cell death 1 ligand 1) still have their limitations in predicting the prognosis of ICI treatment. Hence, reliable predictive markers for ICIs are urgently needed. A public immunotherapy dataset with clinical information and mutational data of 75 NSCLC patients was obtained from cBioPortal as the discovery cohort, and another immunotherapy dataset of 249 patients across multiple cancer types was collected as the validation. Integrated bioinformatics analysis was performed to explore the potential mechanism, and immunohistochemistry studies were used to verify it. AHNAK nucleoprotein 2 (AHNAK2) was reported to have pro-tumor growth effects across multiple cancers, while its role in tumor immunity was unclear. We found that approximately 11% of the NSCLC patients harbored AHNAK2 mutations, which were associated with promising outcomes to ICI treatments (ORR, p = 0.013). We further found that AHNAK2 deleterious mutation (del-AHNAK2mut) possessed better predictive function in NSCLC than non-deleterious AHNAK2 mutation (PFS, OS, log-rank p < 0.05), potentially associated with stronger tumor immunogenicity and an activated immune microenvironment. This work identified del-AHNAK2mut as a novel biomarker to predict favorable ICI response in NSCLC.

Introduction

Lung cancer, histologically differentiated into small cell lung cancer and non–small cell lung cancer, ranks among the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 85% of total cases routinely being treated with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy. Nowadays, tumor immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), have revolutionized NSCLC treatment (1, 2). While ICIs have the potential for a durable response, the response occurs in only a minority of patients (3, 4). Therefore, predictive biomarkers of ICI treatment response are required to provide effective therapy. Although tumor mutation burden (TMB), PD-L1 expression, tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), and some specific gene mutations have been reported to be associated with ICI response (5–9), only a few of them have been validated in the clinic and even those validated biomarkers still had their limitations.

AHNAK2, a protein consisting of many extremely conserved duplicated fragments, shares extensive homology with AHNAK1 and can interact with the C-terminal peptides of a variety of channel proteins (10). AHNAK1 and AHNAK2 co-localized with vinculin, suggesting that the proteins are components of the costameric network (11). It has previously been observed that AHNAK2 is overexpressed in many cancers and acts as a poor prognostic biomarker in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), pancreatic ductal carcinoma (PDAC), papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), and lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) (12–14). Several studies showed that AHNAK2 promotes cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition in LUAD via the MAPK pathway and the TGF-beta/Smad3 pathway (15, 16). A recent study has demonstrated that the expression of AHNAK2 is related to TIICs (tumor-infiltrating immune cells) (17). However, there is no study illustrating the relationship between AHNAK2 and immune response.

In this study, we performed an extensive analysis of AHNAK2 mutation using the previously published immunotherapy cohorts and aimed to explore the predictive value of the AHNAK2 to ICI response in NSCLC patients.

Materials and Methods

Data Download and Processing

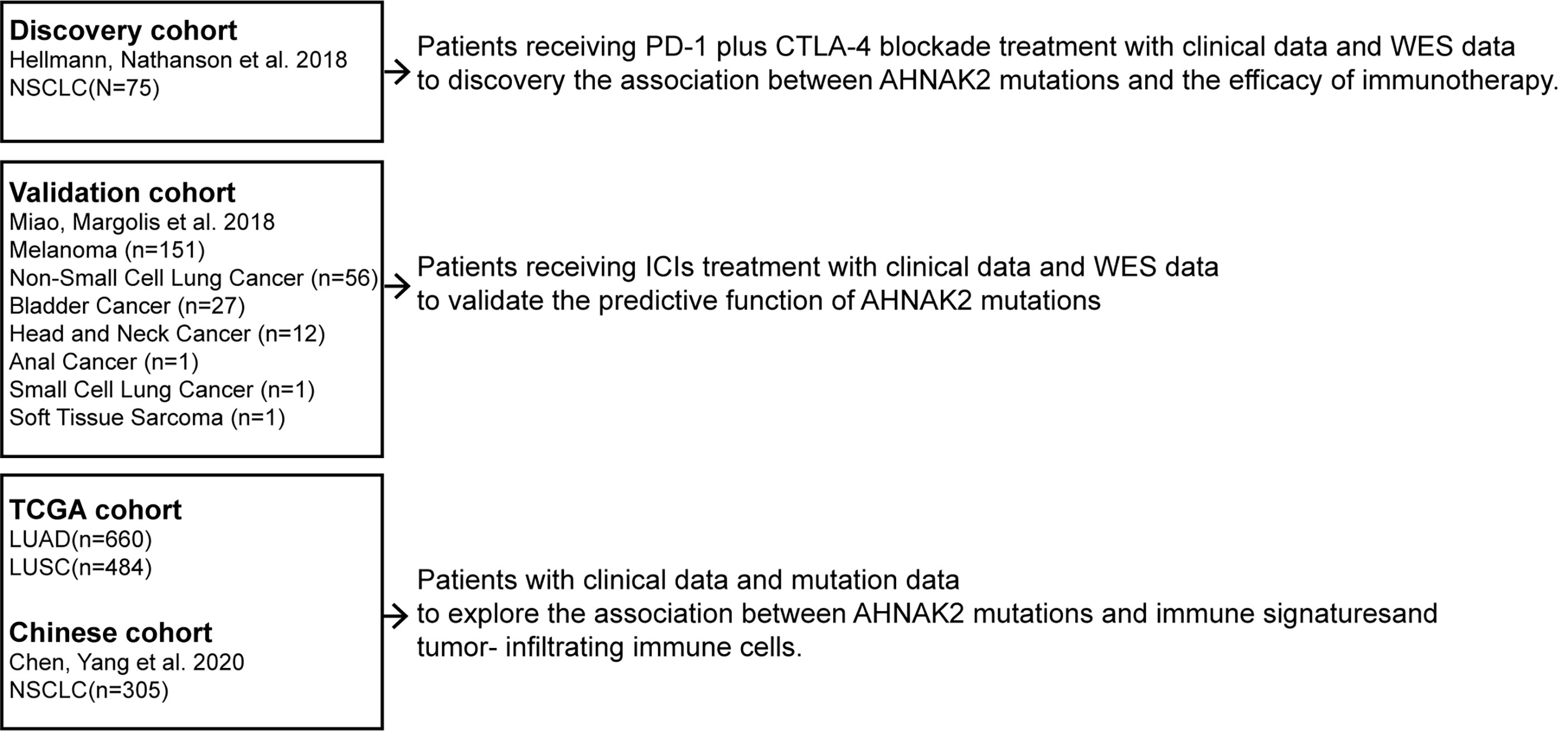

The flow diagram of this study is depicted in Figure 1. To evaluate the predictive functions of AHNAK2 in ICI-treated patients, we use the data accessed from the cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org). A total of 75 NSCLC patients who received anti-PD-L1 plus anti-cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-4 (anti-CTLA-4) treatment with whole-exome sequencing (WES) data (18) were included in our research as the discovery cohort. The validation cohort consisted of 249 patients across multiple cancer types who had received ICI therapy (19).

To study the mechanism underlying the association between AHNAK2 mutation and ICI response, we obtained the WES data along with the corresponding mRNA expression data of 513 LUAD and 480 LUSC in TCGA cohort from the UCSC Xena data portal (https://xenabrowser.net). In addition, 305 Chinese NSCLC patients (20) from cBioPortal, referred to as Chinese cohort, were used to validate the findings.

Clinical Outcomes

The primary clinical outcomes were objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). ORR was assessed with Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. OS and PFS were measured from the start date of ICI therapy to the date of death or progression, respectively, in the ICI-treated cohort. Patients who had not died or progressed were censored at the date of their last scan. In TCGA cohort, OS and PFS were both assessed from the date of the first diagnosis.

PROVEAN Protein Database Evaluating the Mutational Impact on Protein Structure

Missense mutations might be deleterious or benign, on account of their effects on protein structure. The PROVEAN tool (http://provean.jcvi.org) was used to predict the function of missense variants (21). The cutoff for PROVEAN scores was set to −2.5 for high balanced accuracy, and we selected those amino acid changes with the PROVEAN score <−2.5, indicating a deleterious effect on protein function.

Tumor Mutation Characteristics, Tumor Immunogenicity, and TIME Analysis

The cBioPortal online tool was used for visualization of the mutation rates of the top 20 genes and clinical characteristics. TMB was defined as the total number of non-synonymous somatic, coding, base substitution, and indel mutations per megabase (Mb) of the genome examined (22). Neoantigen data in the TCGA cohort were obtained from Thorsson et al. (23).

GSEA was used to associate the gene signatures with AHNAK2 deleterious mutation (del-AHNAK2mut), AHNAK2 non-deleterious mutation (non-del-AHNAK2mut), and AHNAK2 wild type (AHNAK2wt). The normalized enrichment score (NES) is the primary statistic for examining gene set enrichment results. The single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) method was applied to quantify the enrichment levels of the immune signatures in each sample using the “GSVA” R package (24). Twenty-nine characteristic immune signatures were obtained from a previous study (25).

The levels of TILs were calculated by analyzing the data from Saltz et al., who used deep learning-based lymphocyte classification to estimate the H&E-stained images from TCGA dataset (26). The infiltration statuses of twenty-two immune cells were analyzed using the CIBERSORT web portal (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/) (27).

Human Sample Collection and Immunohistochemistry

We collected five cases with two pulmonary nodules from the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, both of which were confirmed as primary NSCLC by pathology. All samples were sequenced through whole-exome sequencing. Interestingly, in each case, one primary lung cancer was confirmed with AHNAK2 mutation and the other was confirmed without AHNAK2 mutation. Anti-CD3, anti-IFNG, and anti-GZMB immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining assays were performed on the tissue sections. The following antibodies were used: anti-CD3 (Servicebio, Wuhan, China, GB111337), anti-GZMB (Servicebio, GB14092), anti-IFNG (Abcam, Cambridge, CA, USA, ab231036). The digital quantitation of immunohistochemistry staining was conducted with HALO image analysis software (Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM, USA).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses and statistical tests were carried out with the R software (version 3.6.1). Univariate Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed, and the survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the enrichment of AHNAK2 status with response (ORR). All comparisons were conducted using the Wilcoxon test. Statistical significance was set as 2-sided p < 0.05 for all comparisons.

Results

Association Between AHNAK2 Mutation and Better Clinical Benefit to ICIs in the Discovery Cohort

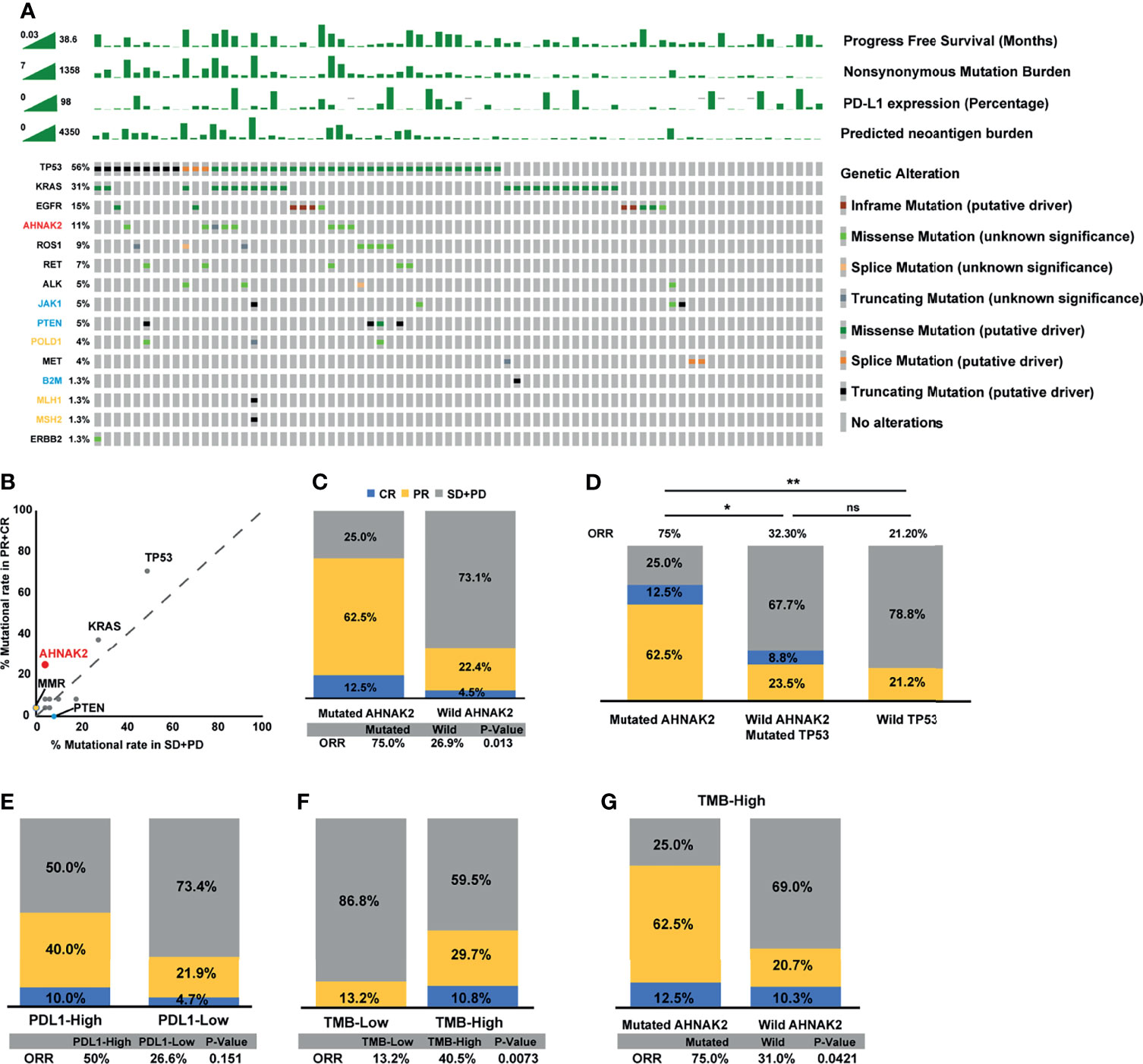

We collected 75 NSCLC patients who received ICI treatment with WES data as the discovery cohort. The genomic mutational landscape from the discovery cohort is displayed in Figure 2A (including genes as suggested by NCCN guidelines and other oncogenes which had been reported to affect the efficacy of immunotherapies (28–31)). In agreement with previous studies, higher mutational rates of TP53, KRAS, and MMR-related genes were shown in responders relative to non-responders. On top of that, AHNAK2 mutation was also observed to be enriched in responders (Figure 2B). The frequency of AHNAK2 mutation was up to 11%, indicating that it was not a rare mutation in NSCLC. We found that the mutation of AHNAK2 was statistical significantly associated with higher ORR (Figure 2C), suggesting that AHNAK2 mutation might predict an improved clinical outcome for NSCLC patients treated with ICIs.

Figure 2 AHNAK2 mutations are significantly associated with better clinical benefit to ICIs in the discovery cohort. (A) Stacked plots show mutational burden, PD-L1 expression, and predicted neoantigen burden (histogram, top); mutations in TP53, KRAS, EGFR, ROS1, RET, ALK, MET, ERBB2 (genes recommended to tested according NCCN guidelines), and JAK1, PTEN, POLD1, B2M, MLH1, MSH2 (genes had been reported to affect the efficacy of immunotherapies; yellow represents positive predictors of immunotherapy, while blue represents negative predictors of immunotherapy) (tile plot, middle) and mutational marks (right). (B) Scatter diagram displays the mutational rate in patients having achieved objective response or progressive disease. MMR: mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2). (C) Histogram depicting proportions of ORR in mutated AHNAK2 and wild AHNAK2 patients. (D) Histogram depicting proportions of ORR in mutated AHNAK2, mutated TP53/wild AHNAK2, and wild TP53 patients. (E) Histogram depicting proportions of ORR in PDL1-High and PDL1-Low patients. (F) Histogram depicting proportions of ORR in mutated TMB-High and TMB-Low patients. (G) Histogram depicting proportions of ORR in mutated AHNAK2 and wild AHNAK2 among TMB-High patients (Mann–Whitney U test; ns, not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Interestingly, we found that all patients with AHNAK2 mutation harbored TP53 mutation in the discovery cohort. As TP53 mutations are known to be correlated with response to immunotherapy, we compared ICI response between patients with TP53 mutation only and patients with both TP53 and AHNAK2 mutation. As shown in Figure 2D, patients with AHNAK2 and TP53 co-mutations achieved a higher ORR than patients with TP53 mutation only. Besides, among patients without AHNAK2 mutation, TP53 was not a statistically significant predictor. These results implied that clinical benefits of ICIs were even more remarkable in patients with AHNAK2 mutation than in those with TP53 mutation.

In addition, we compared the predictive value of AHNAK2 mutation with other widely recognized ICI biomarkers. Here, we found that patients with high PD-L1 expression (≥50% percentage) had higher ORR than those with low PD-L1 expression (<50% percentage), while this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2E). Patients with high TMB level were more likely to benefit from the immunotherapy, which was also observed here (Figure 2F). Notably, AHNAK2 mutation could identify patients with better response to immunotherapy among TMB-high patients (Figure 2G), indicating that the combination of AHNAK2 mutation and TMB level could better stratify patients to identify those who are likely to benefit most from immunotherapy.

Del-AHNAK2mut Is a Predictive, Not Prognostic, Biomarker of ICI Benefit

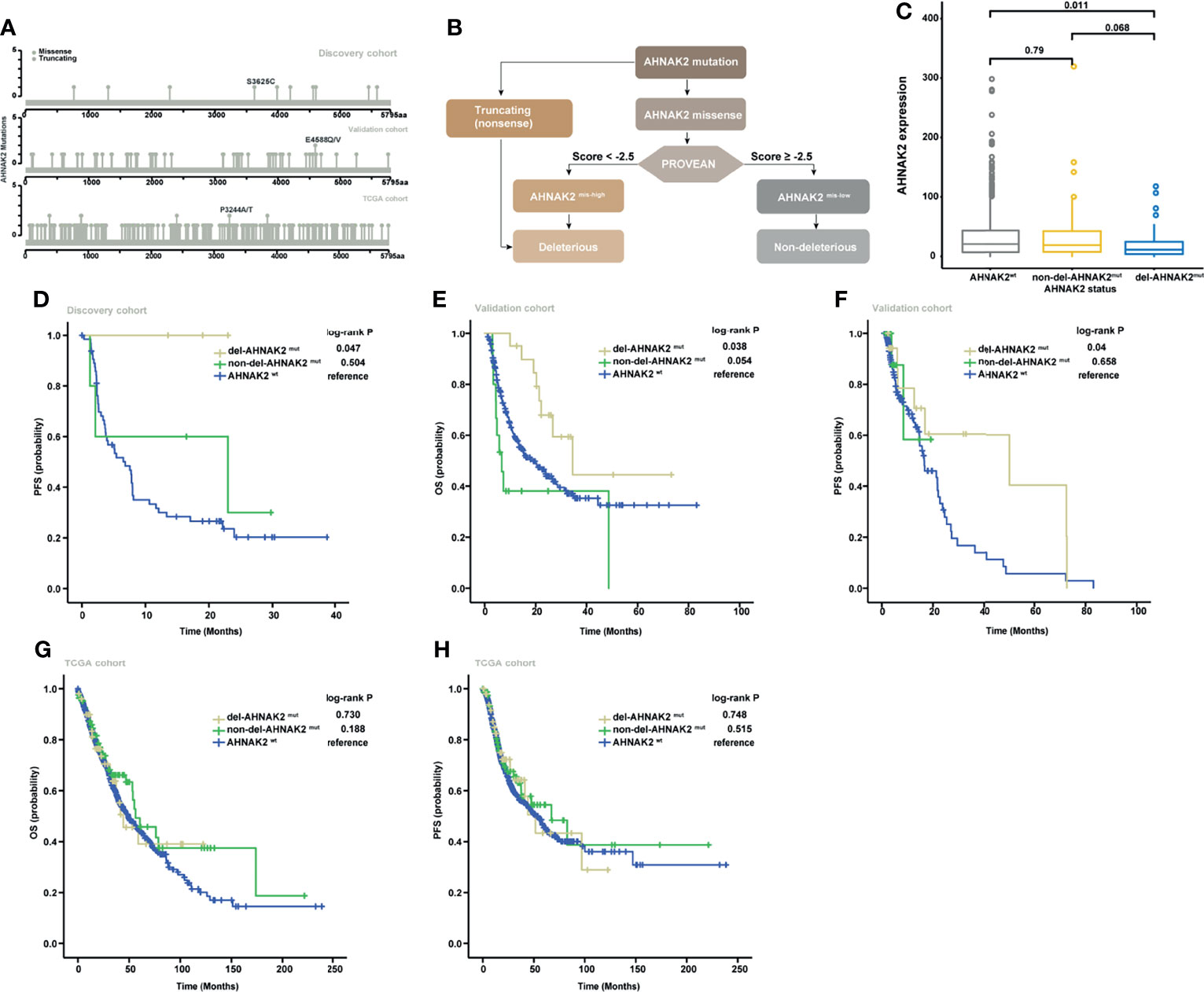

As illustrated in Figure 3A, most of the AHNAK2 alterations were missense mutations, which can be partitioned into deleterious or benign, depending on whether they affect protein structures or not. To exclude the benign mutations that generally do not affect the protein function, the PROVEAN tool was applied to distinguish the missense mutations of AHNAK2 with a high probability of impact on protein structures with a low probability (abbreviated as AHNAK2 mis-high and AHNAK2 mis-low, respectively). Since both truncating and mis-high mutations affect the biological function of the involved genes, we therefore grouped these two kinds of alterations as del-AHNAK2mut. Relatively, patients with mis-low mutations of AHNAK2 were defined as non-del-AHNAK2mut whereas the patients without any AHNAK2 mutations were categorized as the control group (AHNAK2wt). A schematic of the workflow is shown in Figure 3B. As shown in Figure 3C, the patients harboring deleterious AHNAK2 mutations, not non-deleterious AHNAK2 mutations, possessed a trend of better PFS than the patients with AHNAK2wt in the discovery cohort.

Figure 3 Validation of the predictive significance of AHNAK2 in pan-cancer. (A) Lollipop plots showing the locus distribution of mutations across the AHNAK2-altered patient cohorts. (B) Flow diagram of the identification of del-AHNAK2mut and non-del-AHNAK2mut by mutational forms and PROVEAN. (C) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS in the discovery cohort classified by AHNAK2 mutations. (D) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS in the validation cohort classified by AHNAK2 mutations. (E) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFSS in the validation cohort classified by AHNAK2 mutations. (F) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS in the TCGA cohort classified by AHNAK2 mutations. (G) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS in the TCGA cohort classified by AHNAK2 mutations.

To further assess the predictive value of deleterious AHNAK2 mutations, we explored another pan-cancer immunotherapy cohort (19) as an independent external validation. In this validation cohort, the overall mutation frequency of AHNAK2 was 14% with melanoma (17.2%) ranking the most prevalent cancer type followed by non-small cell lung cancer (12.5%) and bladder cancer (7.4%). Consistent with the results described above, the patients harboring deleterious AHNAK2 mutation achieved better survival from ICI treatment compared with those without AHNAK2 mutation (Figures 3D, E). Taking TCGA cohort as a comparison, which includes the NSCLC patients without receiving immunotherapy, we found no significant survival differences between del-AHNAK2mut and AHNAK2wt (Figures 3F, G). These results suggested that del-AHNAK2mut was not linked with prognosis but was associated with significant immunotherapeutic efficacy independently, which delineated the potential predictive value of del-AHNAK2mut in immunotherapy against NSCLC.

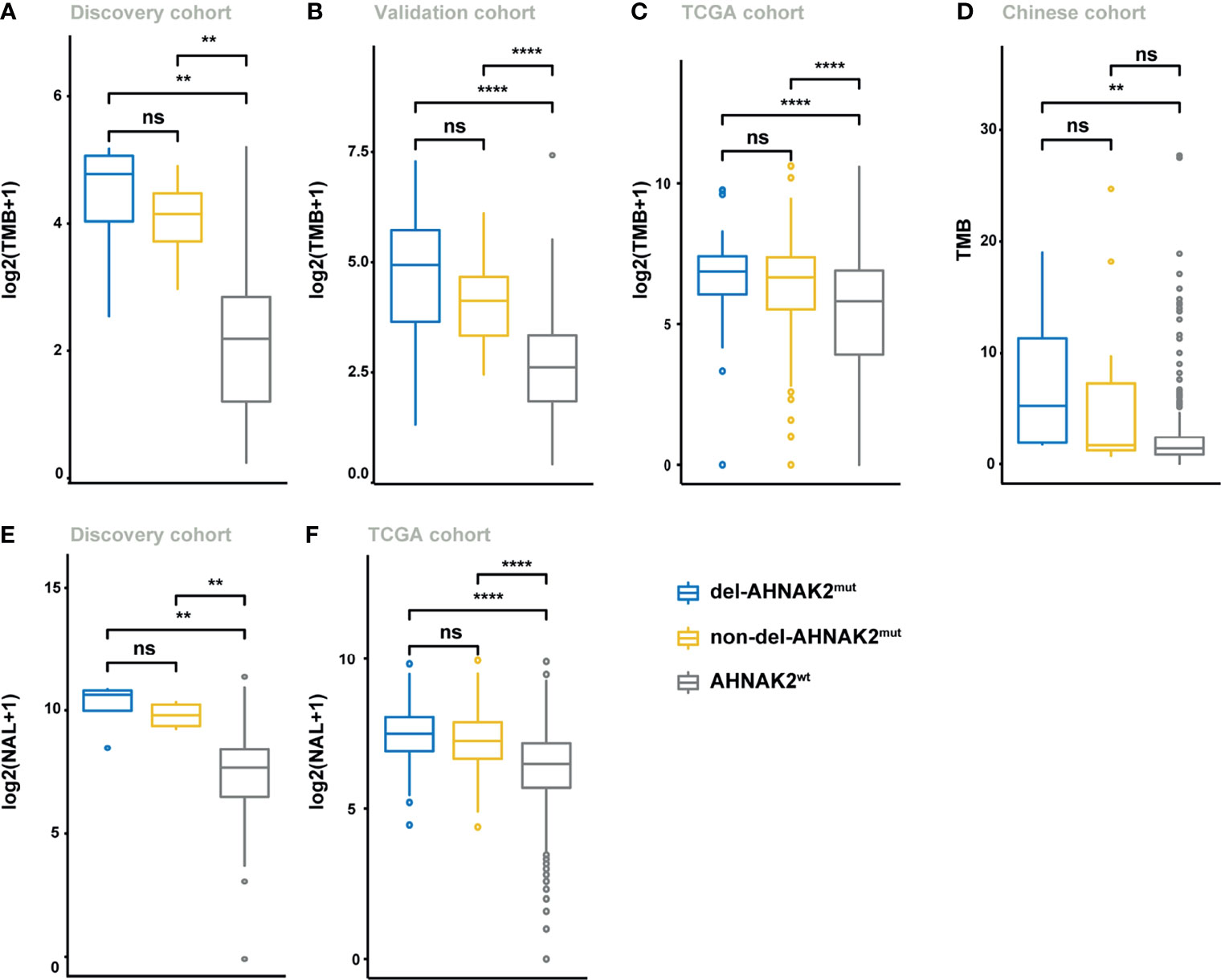

Association Between AHNAK2mut and Higher Tumor Immunogenicity

To investigate the potential mechanism by which AHNAK2 mutations influence the sensitivity of ICI therapy, we first analyzed the mutational burden (TMB) and neoantigen load (NAL). As shown in Figure 4A, higher TMB levels were observed in AHNAK2mut tumors in the discovery cohort, which was verified in the validation cohort, TCGA cohort, and Chinese cohort (Figures 4B–D). In addition, the level of NAL was significantly higher in the AHNAK2mut tumors as well, relative to the AHNAK2wt group (Figures 4E, F). These results suggested that AHNAK2mut tumors were strongly related to enhanced tumor immunogenicity, firmly supporting its predictive value for ICI therapy.

Figure 4 Del-AHNAK2mut was associated with the enhanced tumor immunogenicity. (A–D) Comparison of the levels of TMB in patients from discovery cohort (A), validation cohort (B), TCGA cohort (C), and Chinese cohort (D) classified by AHNAK2 mutations (del-AHNAK2mut, non-del-AHNAK2mut, and no AHNAK2 mutation). (E, F) Comparison of the levels of NAL in patients from discovery cohort (E) and TCGA cohort (F) classified by AHNAK2 mutations (del-AHNAK2mut, non-del-AHNAK2mut, and no AHNAK2 mutation). (Mann–Whitney U test; ns, not significant; **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

Impact of del-AHANK2mut on Activated Immune Microenvironment

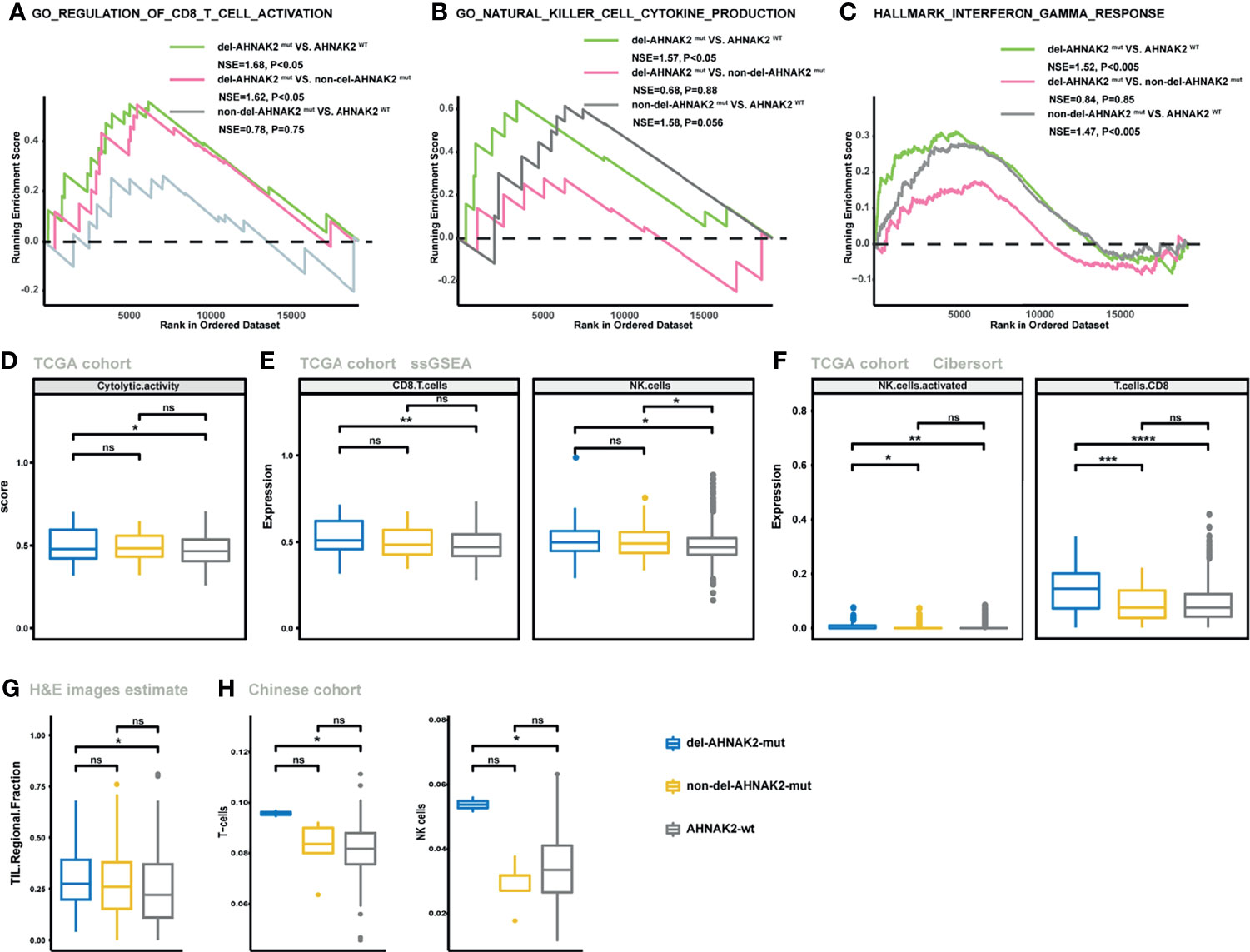

Despite the undifferentiated levels of TMB and NAL observed in the del-AHNAK2mut and non-del-AHNAK2mut groups, the potential mechanisms to immune activation might be dissimilar between these two groups. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ T cells and NK cells) were major mediators of the innate and adaptive antitumor immune response and can use cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes to lyse cancer cells. GSEA revealed prominent enrichment of signatures related to CD8+ T cell and NK cell activation in the del-AHNAK2mut group, compared with the non-del-AHNAK2mut and AHNAK2wt groups (Figures 5A, B). In addition, enhanced IFN-γ signaling was also observed in the del-AHNAK2mut group (Figure 5C). Previous studies have implicated that the efficiency of anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy was dependent on IFN-γ. Produced by cytotoxic immune cells, IFN-γ could facilitate CD8+ T cell and NK cell filtration (32). Next, to test whether del-AHNAK2mut was associated with cytotoxic T lymphocyte function and infiltration, the ssGSEA method was utilized to evaluate the immune status of each patient by analyzing the expression profiles of 29 immune signatures (25). As expected, we found that del-AHNAK2mut tumors expressed higher cytolytic activity scores (Figure 5D), indicating that del-AHNAK2mut might liberate CTL cell effector functions. Beyond this, the del-AHNAK2mut tumors were also characterized by more CD8+ T cell and NK cell infiltrations according to the ssGSEA results (Figure 5E). To cross-examine the above results with different methods of evaluating immune cells, we analyzed the distribution of 22 immune cells based on the CIBERSORT method, observing an increase of CD8+ T cells and NK cells in the tumors with del-AHNAK2mut, relative to those with non-del-AHNAK2mut and AHNAK2wt (Figure 5F). According to the TIL fraction data estimated from hematoxylin and eosin-stained (H&E-stained) slides (26), we found that the TIL fraction of the del-AHNAK2mut tumors was higher than that of the AHNAK2wt tumors (Figure 5G). To further validate the above results, we also analyzed the RNA-sequencing data from the Chinese cohort and obtained similar findings for the high T cell and NK cell infiltration in del-AHNAK2mut tumor (Figure 5H).

Figure 5 The mutation status of AHNAK2 was associated with the activated immune microenvironment. (A–C) GSEA of signatures related to CD8 T cell activation (A), NK cell activation (B), and IFN-γ (C) in comparisons between NSCLC samples with del-AHNAK2mut, non-del-AHNAK2mut, and no AHNAK2 mutation. (D) Comparison of the cytolytic activity score between AHNAK2wt, del-AHNAK2mut, and non-del-AHNAK2mut tumors by the ssGSEA method based on TCGA RNA-sequencing data. (E) Comparison of the infiltration degree of immune cells by the ssGSEA method based on RNA-sequencing data between AHNAK2wt, del-AHNAK2mut, and non-del-AHNAK2mut tumors. (F) Comparison of the infiltration degree of immune cells by the CIBERSORT analysis. (G) Comparison of the TIL regional fractions based on estimates from processing diagnostic H&E images between AHNAK2wt, del-AHNAK2mut, and non-del-AHNAK2mut tumors. (H) Comparison of the infiltration degree of immune cells in the Chinese NSCLC cohort. (Mann–Whitney U test; ns, not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

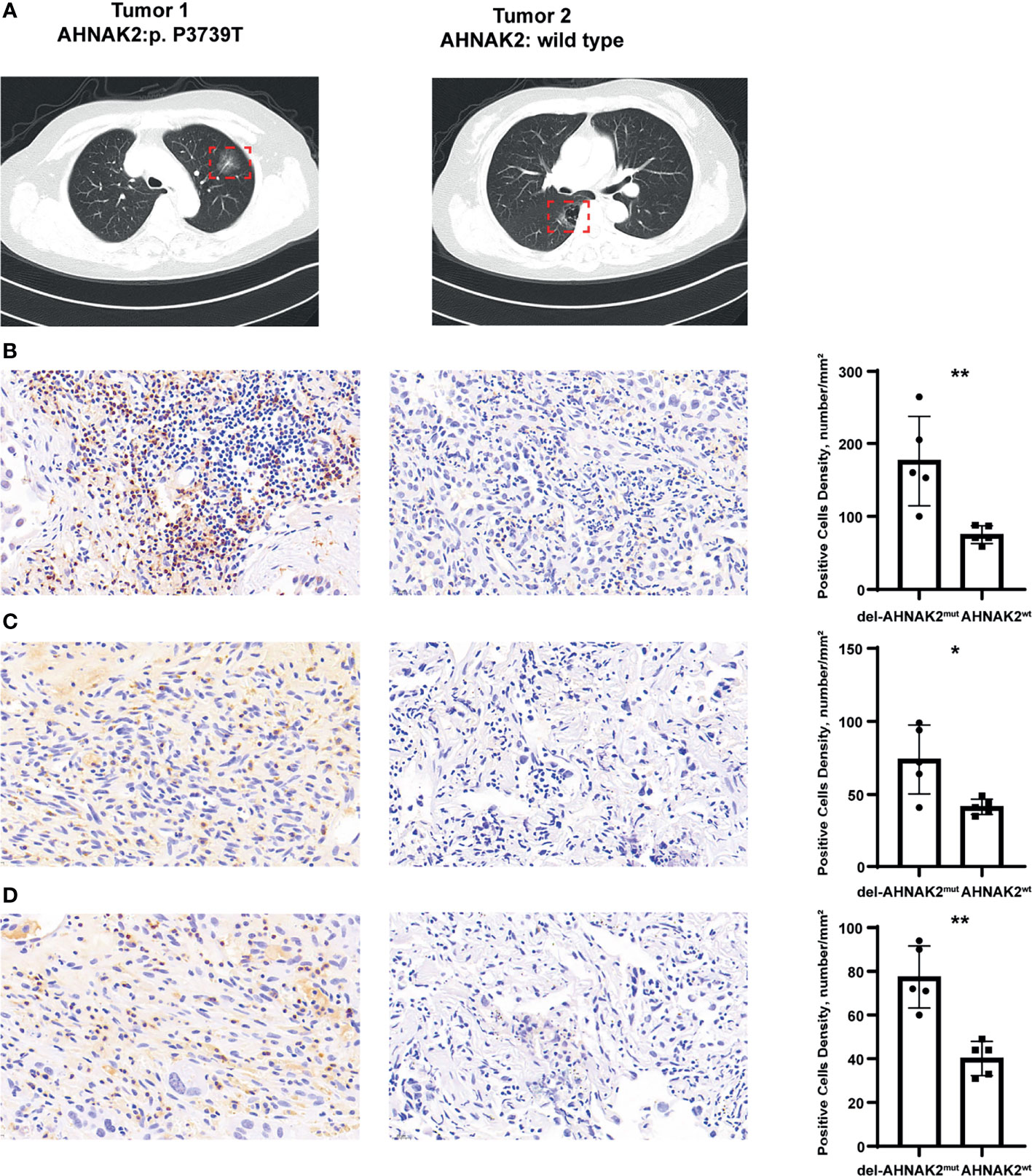

Immunohistochemistry Confirmed the Association Between del-AHANK2mut and Activated Immune Microenvironment

We collected 5 patients with multiple lung cancer (MPLC) from the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, and each patient owned two primary tumors (Figure 6A). After surgical treatment, a total of 10 resected tumors from the 5 patients were processed for whole-exome sequencing. Many studies have revealed that in the context of identical constitutional genetic background and environmental exposure, different lung cancers in the same individual have distinct genomic profiles and can be driven by distinct molecular events (33, 34). In our study, few shared mutations were detected between two tumors from the same patient by performing whole-exome sequencing (Figures S1A, B). Interestingly, in each patient from our study, one tumor was conformed with deleterious AHNAK2 mutation and the other was conformed without AHNAK2 mutation (Figure S1A). In this unique model, tumors with different mutation statuses of AHNAK2 came from the same patient, so some interference caused by genetic background and lifestyle among patients can be reduced to a large extent, enabling us to better explore the association between del-AHNAK2mut and the immune environment. As shown in Figure 6B, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of CD3 confirmed the presence of tumor-infiltrating T cells in the del-AHNAK2mut tumors. In addition, CD3, IFNG, and GZMB were markedly increased in del-AHNAK2mut tumors compared to AHNAK2wt tumors (Figures 6C, D).

Figure 6 Immunohistochemical staining to evaluate the association between del-AHNAK2mut and activated immune microenvironment. (A) Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the representative MPLC patient. (B–D) Quantitative immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of CD3 (B), GZMB (C), and IFNG (D) protein expression in the del-AHNAK2mut and AHNAK2wt groups (n = 5/group). Representative micrographs of these samples are shown. Data represent the mean ± SD. (Mann–Whitney U test; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

To sum up, del-AHNAK2mut positively correlated with activated CTL effector functions, IFN-γ signaling, and infiltration of TIILs, which contributed to the activated immune microenvironment.

Discussion

In recent years, immunotherapy has become a critical milestone of oncology. The growing types of immunotherapy treatments are put into clinical application. Meanwhile, the selection of patients who could get benefit from immunotherapy has also become a formidable clinical problem. Given that the PD-L1 expression or TMB level could not be sufficient to select patients who may benefit the most from immunotherapy, many studies dedicated to identify more precise biomarkers to predict the efficacy of immunotherapy and genetic alterations are among the best-studied (35). For example, gene mutation biomarkers such as POLE, ARID1, and FGFR4 increase the TMB level, expression of PD-L1, and activation of the cellular immunity CD8+ tumor infiltration level (36–38). However, these results were not imperfect.

AHNAK1 and AHNAK2 are two members of the AHNAK family (10), and several studies have strived to decode their function. AHNAK can serve as a structural scaffold to mediate the assembly of multiprotein complexes. Meanwhile, significant evidence has been provided to characterize the role of AHNAK in membrane repair and calcium channel regulation (39, 40). In recent studies, AHNAK1 has also been proved as a tumor suppressor in several cancers, including colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, glioma, and lung cancer (41–45). However, as a homologous gene, AHNAK2 appears to play the opposite function promoting cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal translation. AHNAK2 expression negatively correlated with activated CD8+ T cell infiltration. We thus posit that the dysfunction of AHNAK2 may contribute to tumor immunity and improved outcomes in ICI-treated NSCLC.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to propose the predictive value of the AHNAK2 in ICI treatment. In our study, we demonstrated that patients harboring AHNAK2 mutations were likely to have a better response to ICI treatment. Importantly, among all kinds of AHNAK2 alterations, compared to non-deleterious, deleterious mutation might exhibit more predictive power. Del-AHNAK2mut was closely correlated with the higher TMB and NAL level and activation of the NK cells, T cells, and IFN-γ signaling, which in turn initiate a therapeutic immune response in NSCLC.

A major limitation of the study is the limited sample size. AHNAK2 mutation was not included in the routine gene panel; it could only be detected with whole exon sequencing. So far, only two public immunotherapy studies have used the whole exon sequencing, which has been included in our study as the discovery cohort and validation cohort. To compensate for this limitation, RNA-seq data from the TCGA cohort and Chinese cohort were used to verify the association between del-AHNAK2mut and activated immune microenvironment. Further studies are needed to decrypt the effect of AHNAK2 in cancer immunotherapy. In addition, while our results suggest that del-AHNAK2mut may play a role in the regulation of the tumor microenvironment, no specific molecular mechanisms were determined. An earlier report raised a potential mechanism by which AHNAK1 affects CTL function by disrupting calcium entry formation (46). In our study, we also found that AHNAK2 loss-of-function mutation could liberate CTL (CD8+ T cells and NK cells) effector function. As the homolog gene of AHNAK1, whether AHNAK2 can also influence the calcium entry which in turn regulates TIILs remains a subject for future research.

In conclusion, we proposed that del-AHNAK2mut could serve as a novel biomarker for NSCLC patients with ICI treatment. Predictive biomarkers to ICIs, such as the TMB level, NAL level, and TIICs, are closely associated with deleterious AHNAK2 mutations.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

YC: conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. XyL: writing—reviewing and editing. YW: data curation. XL: methodology. JD: data curation. ZZ and RG: supervision, project administration. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972188) and the Medical Important Talents of Jiangsu Province (ZDRCA2016024).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.798401/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, et al. Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2015) 373(17):1627–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643

2. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2016) 375(19):1823–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774

3. Rotte A, Jin JY, Lemaire V. Mechanistic Overview of Immune Checkpoints to Support the Rational Design of Their Combinations in Cancer Immunotherapy. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol (2018) 29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx686

4. Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, Flores-Chávez A, Keegan N, Khamashta MA, et al. Immune-Related Adverse Events of Checkpoint Inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers (2020) 6(1):38. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

5. Wu HX, Chen YX, Wang ZX, Zhao Q, He MM, Wang YN, et al. Alteration in TET1 as Potential Biomarker for Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Multiple Cancers. J Immunother Cancer (2019) 7(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0737-3

6. Hakimi AA, Voss MH, Kuo F, Sanchez A, Liu M, Nixon BG, et al. Transcriptomic Profiling of the Tumor Microenvironment Reveals Distinct Subgroups of Clear Cell Renal Cell Cancer: Data From a Randomized Phase III Trial. Cancer Discovery (2019) 9(4):510–25. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0957

7. Ready N, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, Otterson GA, Gutierrez M, Gainor JF, et al. First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (CheckMate 568): Outcomes by Programmed Death Ligand 1 and Tumor Mutational Burden as Biomarkers. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2019) 37(12):992–1000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01042

8. Zhou H, Liu J, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Shen J, Yang Y, et al. PBRM1 Mutation and Preliminary Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade Treatment in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol (2020) 4:6. doi: 10.1038/s41698-020-0112-3

9. Ott PA, Bang YJ, Piha-Paul SA, Razak ARA, Bennouna J, Soria JC, et al. T-Cell-Inflamed Gene-Expression Profile, Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, and Tumor Mutational Burden Predict Efficacy in Patients Treated With Pembrolizumab Across 20 Cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol (2019) 37(4):318–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.2276

10. Komuro A, Masuda Y, Kobayashi K, Babbitt R, Gunel M, Flavell RA, et al. The AHNAKs are a Class of Giant Propeller-Like Proteins That Associate With Calcium Channel Proteins of Cardiomyocytes and Other Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2004) 101(12):4053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308619101

11. Marg A, Haase H, Neumann T, Kouno M, Morano I. AHNAK1 and AHNAK2 Are Costameric Proteins: AHNAK1 Affects Transverse Skeletal Muscle Fiber Stiffness. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2010) 401(1):143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.030

12. Wang M, Li X, Zhang J, Yang Q, Chen W, Jin W, et al. AHNAK2 Is a Novel Prognostic Marker and Oncogenic Protein for Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Theranostics (2017) 7(5):1100–13. doi: 10.7150/thno.18198

13. Xie Z, Lun Y, Li X, He Y, Wu S, Wang S, et al. Bioinformatics Analysis of the Clinical Value and Potential Mechanisms of AHNAK2 in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Aging (2020) 12(18):18163–80. doi: 10.18632/aging.103645

14. Lu D, Wang J, Shi X, Yue B, Hao J. AHNAK2 Is a Potential Prognostic Biomarker in Patients With PDAC. Oncotarget (2017) 8(19):31775–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15990

15. Liu G, Guo Z, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Zhu D. AHNAK2 Promotes Migration, Invasion, and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells via the TGF-β/Smad3 Pathway. OncoTargets Ther (2020) 13:12893–903. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S281517

16. Wang D-W, Zheng H-Z, Cha N, Zhang X-J, Zheng M, Chen M-M, et al. Down-Regulation of AHNAK2 Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Migration and Invasion Through Inactivating the MAPK Pathway in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat (2020) 19:1533033820957006. doi: 10.1177/1533033820957006

17. Zheng M, Liu J, Bian T, Liu L, Sun H, Zhou H, et al. Correlation Between Prognostic Indicator AHNAK2 and Immune Infiltrates in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol (2021) 90:107134. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107134

18. Hellmann MD, Nathanson T, Rizvi H, Creelan BC, Sanchez-Vega F, Ahuja A, et al. Genomic Features of Response to Combination Immunotherapy in Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell (2018) 33(5):843–52.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.04.005

19. Miao D, Margolis CA, Vokes NI, Liu D, Taylor-Weiner A, Wankowicz SM, et al. Genomic Correlates of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Microsatellite-Stable Solid Tumors. Nat Genet (2018) 50(9):1271–81. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0200-2

20. Chen J, Yang H, Teo ASM, Amer LB, Sherbaf FG, Tan CQ, et al. Genomic Landscape of Lung Adenocarcinoma in East Asians. Nat Genet (2020) 52(2):177–86. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0569-6

21. Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the Functional Effect of Amino Acid Substitutions and Indels. PloS One (2012) 7(10):e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688

22. Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N Engl J Med (2017) 377(25):2500–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444

23. Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D, Bortone DS, Ou Yang T-H, et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity (2018) 48(4):812–30.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.02

24. Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: Gene Set Variation Analysis for Microarray and RNA-Seq Data. BMC Bioinf (2013) 14:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7

25. He Y, Jiang Z, Chen C, Wang X. Classification of Triple-Negative Breast Cancers Based on Immunogenomic Profiling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR (2018) 37(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-1002-1

26. Saltz J, Gupta R, Hou L, Kurc T, Singh P, Nguyen V, et al. Spatial Organization and Molecular Correlation of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Using Deep Learning on Pathology Images. Cell Rep (2018) 23(1):181–93.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.086

27. Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, et al. Robust Enumeration of Cell Subsets From Tissue Expression Profiles. Nat Methods (2015) 12(5):453–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337

28. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer Immunology. Mutational Landscape Determines Sensitivity to PD-1 Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Science (2015) 348(6230):124–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348

29. Haradhvala NJ, Kim J, Maruvka YE, Polak P, Rosebrock D, Livitz D, et al. Distinct Mutational Signatures Characterize Concurrent Loss of Polymerase Proofreading and Mismatch Repair. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1746. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04002-4

30. Dong Z-Y, Zhong W-Z, Zhang X-C, Su J, Xie Z, Liu S-Y, et al. Potential Predictive Value of and Mutation Status for Response to PD-1 Blockade Immunotherapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2017) 23(12):3012–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2554

31. Miao D, Margolis CA, Gao W, Voss MH, Li W, Martini DJ, et al. Genomic Correlates of Response to Immune Checkpoint Therapies in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Science (2018) 359(6377):801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5951

32. Jorgovanovic D, Song M, Wang L, Zhang Y. Roles of IFN-γ in Tumor Progression and Regression: A Review. biomark Res (2020) 8:49. doi: 10.1186/s40364-020-00228-x

33. Ma P, Fu Y, Cai M-C, Yan Y, Jing Y, Zhang S, et al. Simultaneous Evolutionary Expansion and Constraint of Genomic Heterogeneity in Multifocal Lung Cancer. Nat Commun (2017) 8(1):823. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00963-0

34. Liu Y, Zhang J, Li L, Yin G, Zhang J, Zheng S, et al. Genomic Heterogeneity of Multiple Synchronous Lung Cancer. Nat Commun (2016) 7:13200. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13200

35. Rossi G, Russo A, Tagliamento M, Tuzi A, Nigro O, Vallome G, et al. Precision Medicine for NSCLC in the Era of Immunotherapy: New Biomarkers to Select the Most Suitable Treatment or the Most Suitable Patient. Cancers (2020) 12(5):1125. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051125

36. Song Z, Cheng G, Xu C, Wang W, Shao Y, Zhang Y, et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics of POLE Mutation in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam Netherlands) (2018) 118:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.02.004

37. Wang L, Ren Z, Yu B, Tang J. Development of Nomogram Based on Immune-Related Gene FGFR4 for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients With Sensitivity to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Trans Med (2021) 19(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02679-0

38. Sun D, Tian L, Zhu Y, Wo Y, Liu Q, Liu S, et al. Subunits of ARID1 Serve as Novel Biomarkers for the Sensitivity to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Prognosis of Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Med (Cambridge Mass.) (2020) 26(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00208-9

39. Sussman J, Stokoe D, Ossina N, Shtivelman E. Protein Kinase B Phosphorylates AHNAK and Regulates Its Subcellular Localization. J Cell Biol (2001) 154(5):1019–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105121

40. Davis TA, Loos B, Engelbrecht AM. AHNAK: The Giant Jack of All Trades. Cell Signal (2014) 26(12):2683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.08.017

41. Shen E, Wang X, Liu X, Lv M, Zhang L, Zhu G, et al. MicroRNA-93-5p Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Gastric Cancer by Repressing Tumor Suppressor AHNAK Expression. Cancer Cell Int (2020) 20:76. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-1092-7

42. Cho W-C, Jang J-E, Kim K-H, Yoo B-C, Ku J-L. SORBS1 Serves a Metastatic Role via Suppression of AHNAK in Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. Int J Oncol (2020) 56(5):1140–51. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.5006

43. Zhao Z, Xiao S, Yuan X, Yuan J, Zhang C, Li H, et al. AHNAK as a Prognosis Factor Suppresses the Tumor Progression in Glioma. J Cancer (2017) 8(15):2924–32. doi: 10.7150/jca.20277

44. Chen B, Wang J, Dai D, Zhou Q, Guo X, Tian Z, et al. AHNAK Suppresses Tumour Proliferation and Invasion by Targeting Multiple Pathways in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR (2017) 36(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0522-4

45. Park JW, Kim IY, Choi JW, Lim HJ, Shin JH, Kim YN, et al. AHNAK Loss in Mice Promotes Type II Pneumocyte Hyperplasia and Lung Tumor Development. Mol Cancer Res: MCR (2018) 16(8):1287–98. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0726

Keywords: NSCLC, AHNAK2, immune checkpoint inhibitors, biomarker, immune microenvironment

Citation: Cui Y, Liu X, Wu Y, Liang X, Dai J, Zhang Z and Guo R (2022) Deleterious AHNAK2 Mutation as a Novel Biomarker for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 12:798401. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.798401

Received: 21 October 2021; Accepted: 14 February 2022;

Published: 10 March 2022.

Edited by:

Nicolas Poté, Bichat Hospital, FranceReviewed by:

Rohimah Mohamud, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), MalaysiaEdouard Guenzi, Assistance Publique Hopitaux De Paris, France

Copyright © 2022 Cui, Liu, Wu, Liang, Dai, Zhang and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renhua Guo, cmhndW9AbmptdS5lZHUuY24=; Zhihong Zhang, emhhbmd6aEBuam11LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yanan Cui1†

Yanan Cui1† Zhihong Zhang

Zhihong Zhang Renhua Guo

Renhua Guo