94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Oncol., 14 March 2022

Sec. Molecular and Cellular Oncology

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.772351

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Role of ncRNAs (non-coding RNAs) in Regulating Tumor Immune MicroenvironmentView all 32 articles

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous group of immature cells derived from bone marrow that play critical immunosuppressive functions in the tumor microenvironment (TME), promoting cancer progression. According to base length, Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are mainly divided into: microRNAs (miRNAs), lncRNAs, snRNAs and CircRNAs. Both miRNA and lncRNA are transcribed by RNA polymerase II, and they play an important role in gene expression under both physiological and pathological conditions. The increasing data have shown that MiRNAs/LncRNAs regulate MDSCs within TME, becoming one of potential breakthrough points at the investigation and treatment of cancer. Therefore, we summarize how miRNAs/lncRNAs mediate the differentiation, expansion and immunosuppressive function of tumor MDSCs in TME. We will then focus on the regulatory mechanisms of exosomal MicroRNAs/LncRNAs on tumor MDSCs. Finally, we will discuss how the interaction of miRNAs/lncRNAs modulates tumor MDSCs.

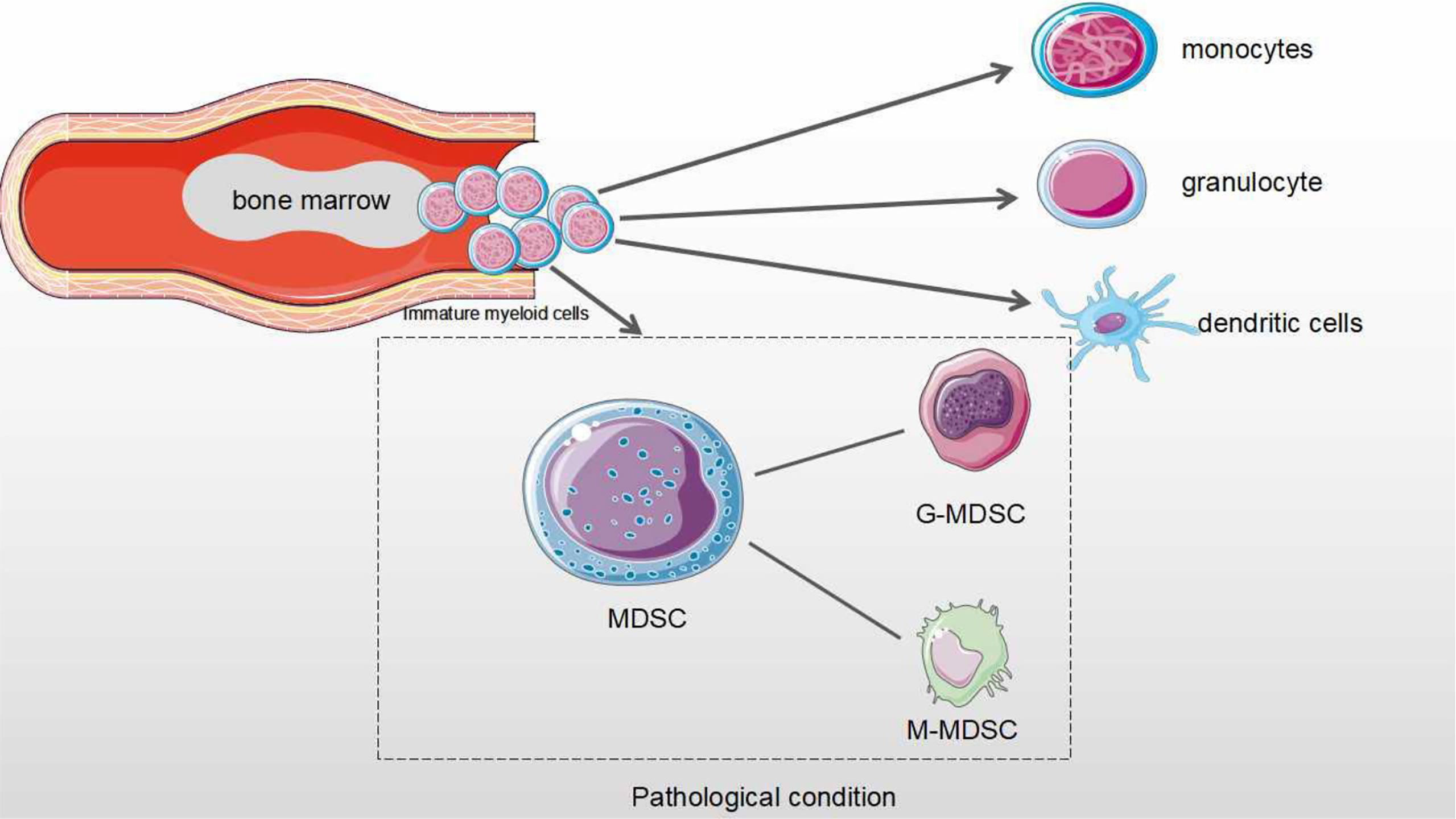

MDSCs are a heterogeneous population derived from bone marrow progenitor cells and immature myeloid cells (1). In normal physiology, immature myeloid cells are differentiated into monocytes, granulocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells, which exert immune activity (2). However, in cancers and other diseases (such as inflammation), MDSCs have the negative regulatory immune response to exacerbate disease status (2, 3). In the process of tumor progression, MDSCs cannot properly differentiated into monocytes and macrophages to play their immune roles, but abnormally proliferate and accumulate within TME (4). Tumor cells secrete many factors to inhibit the differentiation of immature myeloid cells and promote the proliferation and immunosuppressive roles of MDSCs (5). These mediators mainly include the TGF-β, Ligands for toll-like receptors, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-6, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L), Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-SCF), Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-4 (6). Most mediators activate the functional state of MDSCs by regulating signal converters and transcriptional activators (STATs and NFκB) (7, 8). For example, IL-6 enhances both stimulatory and inhibitory roles of MDSCs via STAT3 signaling pathways in breast cancer (8, 9).

Tumor MDSCs are mainly divided into two main subtypes according to their phenotypes and origins, which are defined by cell surface markers of MDSCs in both tumor models and cancer patients (10, 11). The phenotypes of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice are defined using Gr1 (ly6G/ly6C)/CD11b and further include two subtypes of MDSCs: Monocyte-MDSCs (M-MDSCs, CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6Chi) and Granulocyte-MDSCs (G-MDSCs, CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clo) (12, 13). The phenotypes of MDSCs are more diverse in cancer patients. MDSCs are cell populations expressing Lin-HLA-DR-CD33+ or CD11b-CD14-CD33+ in human body. The main subtypes are also divided into M-MDSCs (HLA-DR−/loCD11b+CD14+ CD15−) and G-MDSCs (CD11b+ CD14− CD15+ or CD11b+CD14− CD66b+) (14). Third subtype known as early-MDSCs which has been found in human studies. They are defined as Lin-HLA-DR-CD33+, mainly consisting of colony-forming cells activity and other myeloid precursor cells (13, 15).

M-MDSCs account for about 80% of all tumor MDSCs, but their inhibitory roles are lower than those of G-MDSCs. M-MDSCs are modulated by producing NO and Arginases. In contrast, the roles of G-MDSCs are determined by ROS and H2O2 (16–19). The main function of G-MDSCs is to inhibit T cell function, while M-MDSCs mainly differentiate into TAMs in cancer. It is well known that MDSCs have become the most important prognostic markers in cancer immunotherapy and contribute to immunosuppressive checkpoint resistance (20) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The differentiation process of MDSCs in physiological and pathological conditions. Under normal physiological conditions, myeloid progenitor cells are differentiated into monocytes, granulocytes and dendritic cells that are involved in the regulation of immune response. Under pathological condition, myeloid progenitor cells are differentiated into MDSCs. MDSCs from Immature myeloid cells are divided as two subtypes: monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs) and Granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs).

MiRNAs are non-coding single-stranded small RNAs of approximately 22-24 nucleotides in length and are highly conserved evolutionarily, and are widely found in eukaryotic cells. They play vital regulatory roles in cells, especially in mRNA post-transcriptional regulation, and reduce mRNA expression levels by binding to the 3’UTR of mRNA and binding to the 5 ‘-UTR of mRNA to upregulate its transcription (10–12). MiRNAs are involved in regulating both a wide range of physiological activities such as cell cycle, differentiation, proliferation, maturation and immune response and pathological processes, such as inflammation and cancer (13). For example, our data have shown that miRNAs mediate the differentiation, expansion and function of tumor MDSCs (14).

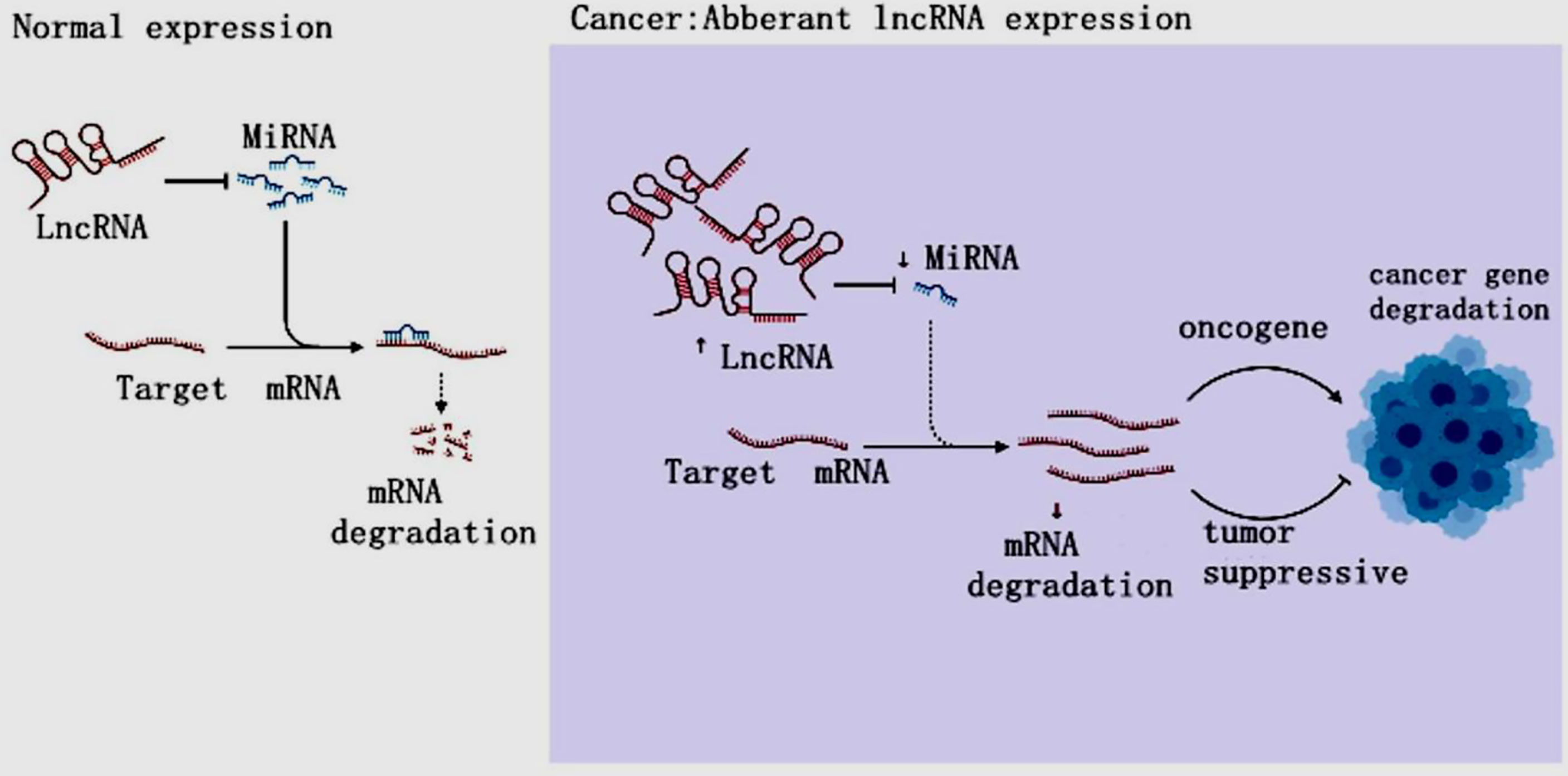

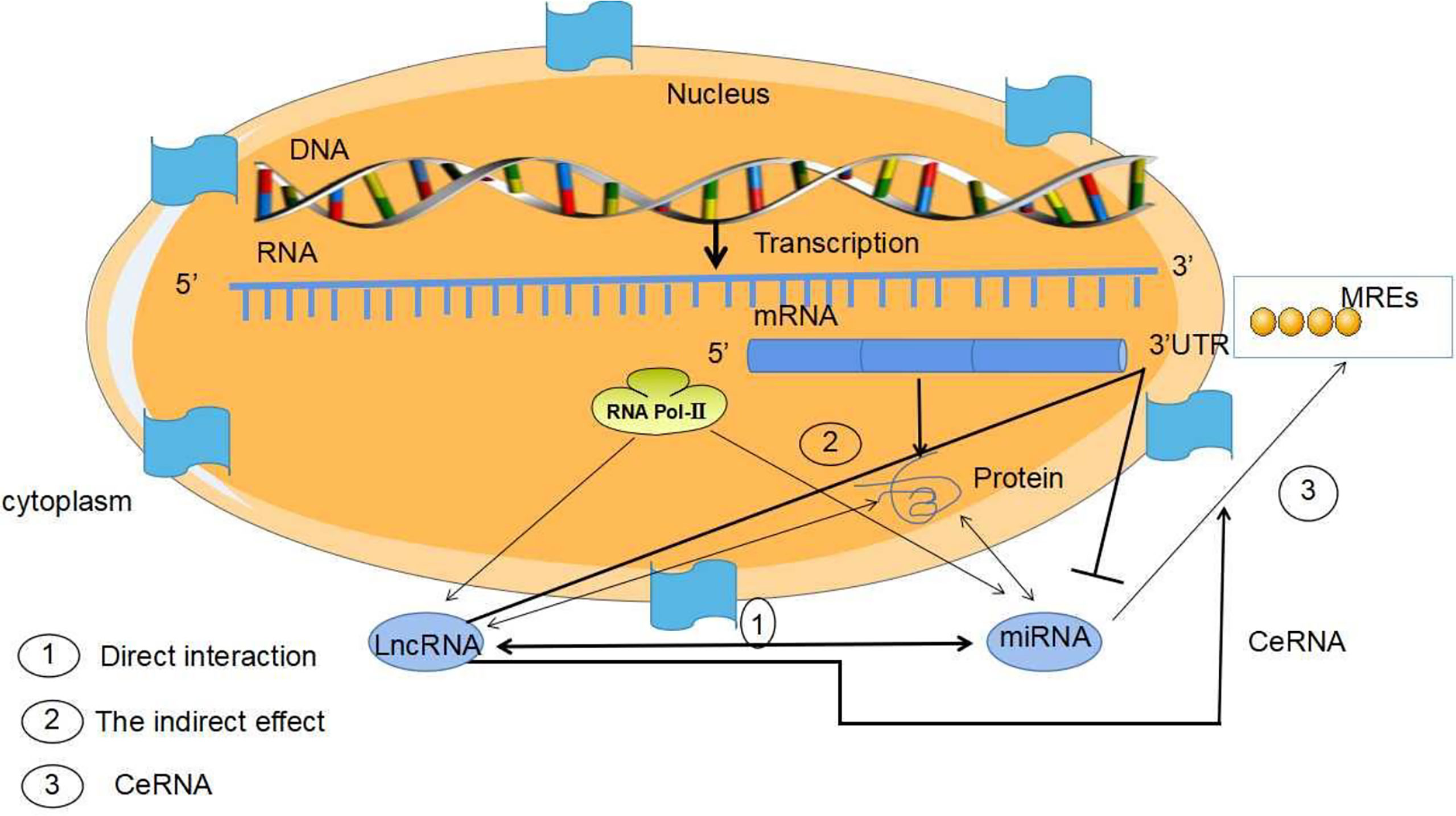

LncRNAs are non-protein-coding RNAs of approximately 200 nucleotides in length (15). According to the position of lncRNAs in the genome relative to protein-coding genes, they can be divided into five categories: sense, antisense, bidirectional, intronic and intergenic (16, 17). LncRNAs are ever regarded byproducts of RNA polymerase II transcription as “noise” of genomic transcription without biological function (5, 17). However, the increasing evidences have revealed that LncRNAs mediate gene expression through chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation and post-transcriptional regulation in the nucleus and extranuclear, and are also involved in the occurrence and development of tumors (18–22) (Figure 2). LncRNAs have been found to mediate the carcinogenesis of colon cancer through a variety of molecular mechanisms, suggesting that lncRNAs can be used as biomarkers for early diagnosis and treatment of colon cancer (23). LncRNAs are overexpressed during the development, differentiation and activation of immune cells, such as monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils (24). Furthermore, the increasing data were conducted on the activity of lncRNAs on MDSCs in TME (16, 25–27). Both miRNA and lncRNAs, as Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) can modulate tumor MDSCs. Thus, here we discuss the regulatory mechanisms of miRNAs/lncRNAs on the biological status and immune activity of MDSCs in TME, and put forward our own opinions.

Figure 2 The LncRNA Regulation in cancer. In cancer, lncRNAs inhibit targeted mRNAs through endogenous competition with miRNAs, resulting in mRNA downregulation and carcinogenesis, resulting in tumor gene disorder and cancer.

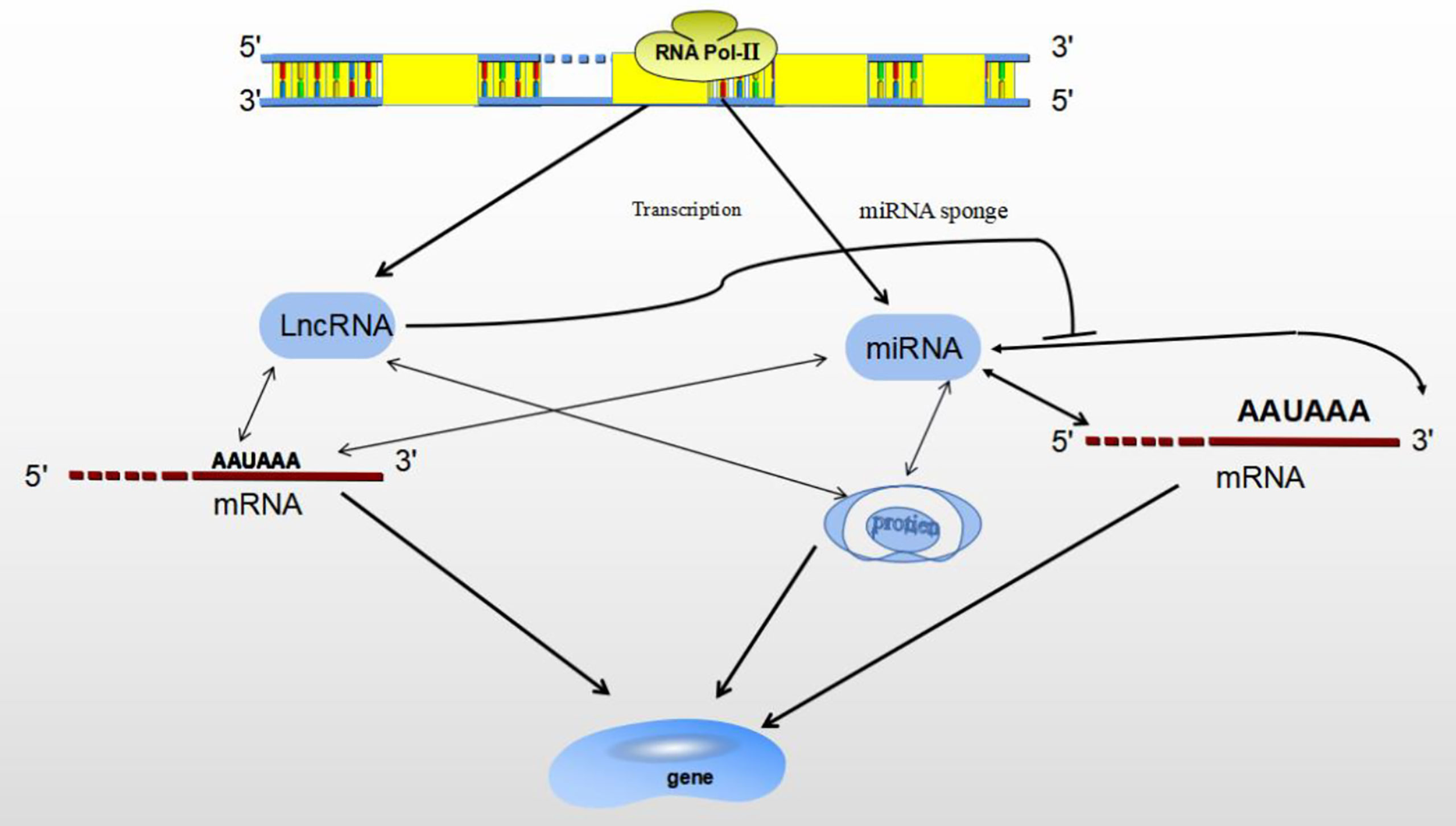

ncRNAs are mainly divided by length into small (< 200 nucleotides) and long (> 200 nucleotides) RNAs according to base length. ncRNAs are: miRNAs、lncRNAs、snRNAs、circRNAs (28). ncRNAs act as regulatory molecules that regulate for a wide range of cellular processes, such as chromatin remodeling, transcription and post-transcriptional modification (29). MiRNAs have been well investigated over the past decade, lncRNAs are actively studied for their diverse roles in gene expression regulation. Besides, lncRNAs themselves can interact with other ncRNAs, such as miRNAs (30). Both miRNA and lncRNA are transcribed by RNA polymerase II, and they play important roles in gene expression under both physiological and pathological conditions, as transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulators (28). Studies have shown that miRNAs and lncRNAs are involved in transcriptional regulation at different levels, miRNAs/lncRNAs directly determine gene expression by binding with mRNA, gene/transcript or histone modifiers (31). LncRNAs may play a functional role as miRNA sponges by base-pair blocking of miRNA binding to target mRNA-3’UTR (32) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The relationship between MiRNA and LncRNA. Both miRNA and lncRNA regulate gene expression through binding with mRNA, gene/transcript or histone modifiers. LncRNA may sponges miRNA by base-pair blocking of miRNA response elements binding to target mRNA-3’UTR.

Recent studies have highlighted the diverse roles of MiRNAs/LncRNAs in cancer progression and metastasis. Increasing numbers of miRNAs and lncRNAs are found to be dysregulated in cervical cancer, regulating metastasis through regulating metastasis-related genes and signaling pathways. Moreover, miRNAs can interact with lncRNAs respectively during this complex process (33, 34). In breast cancer, the lncRNA MALAT1 and miR-100 are indirectly interlinked through VEGFA. MALAT1 binds to miR-216b as a competing endogenous RNA to restore Pyridox(am)ine-5- phosphate Oxidase deficiency (PNPO) and promote cell proliferation, migration and invasion in breast cancer (33). Therefore, miRNAs/lncRNAs are involved in gene expression and transcriptional regulation. They also affect the development of cancer and regulate the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressors in TME (28, 32, 35). Therefore, the regulation of miRNA/lncRNA is more conducive to the research of bioactive targets for cancer treatment.

Researchers have found that the interactions between miRNAs/LncRNAs and transcription factor modulated the biological status and immune activity of MDSCs in TME (36). Here, we describe the regulation of miRNA/lncRNA on MDSCs in the TME. The abnormal expression of miRNAs/lncRNAs in MDSCs and their regulatory mechanism on MDSCs have become potential breakthrough points.

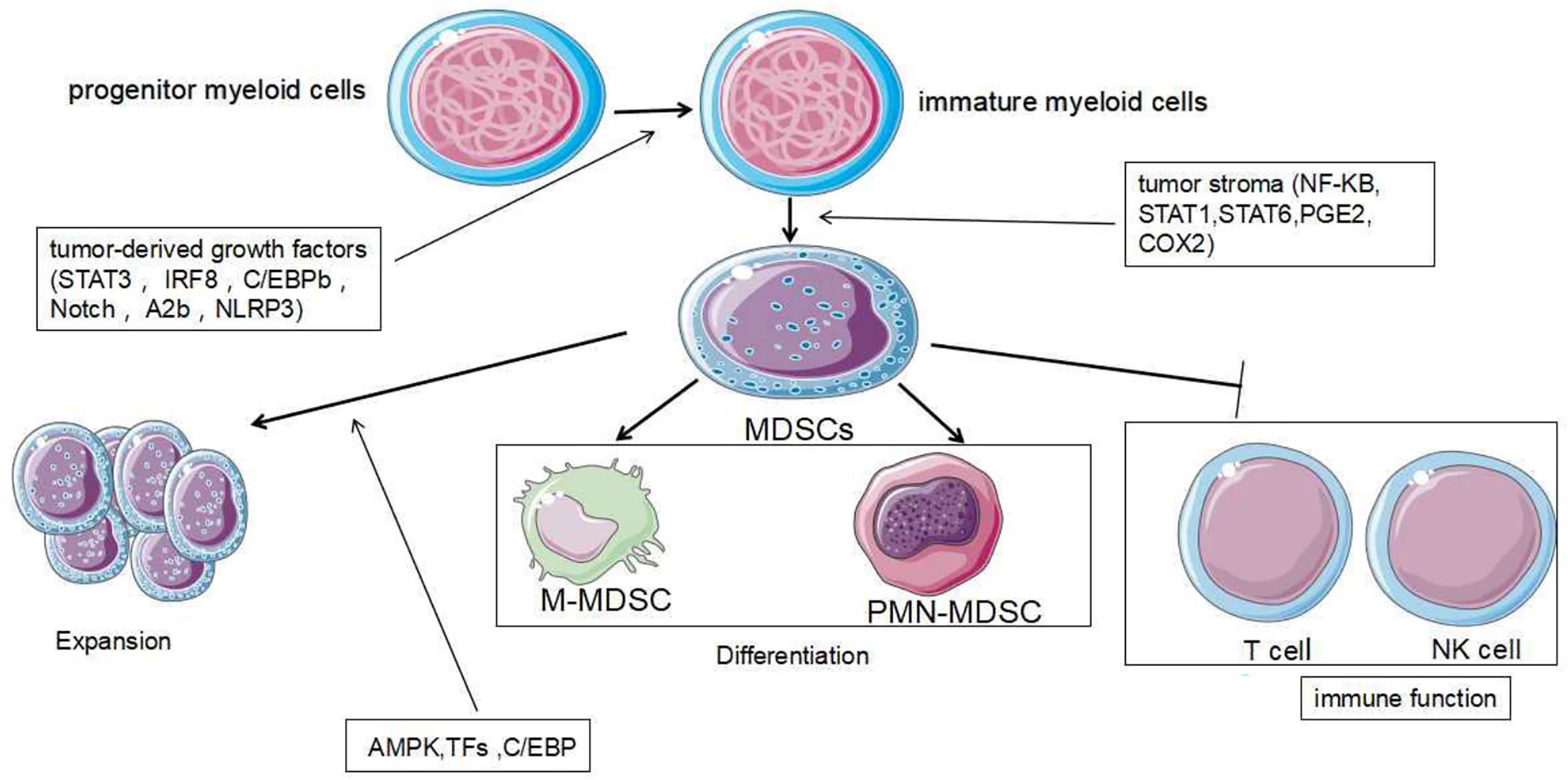

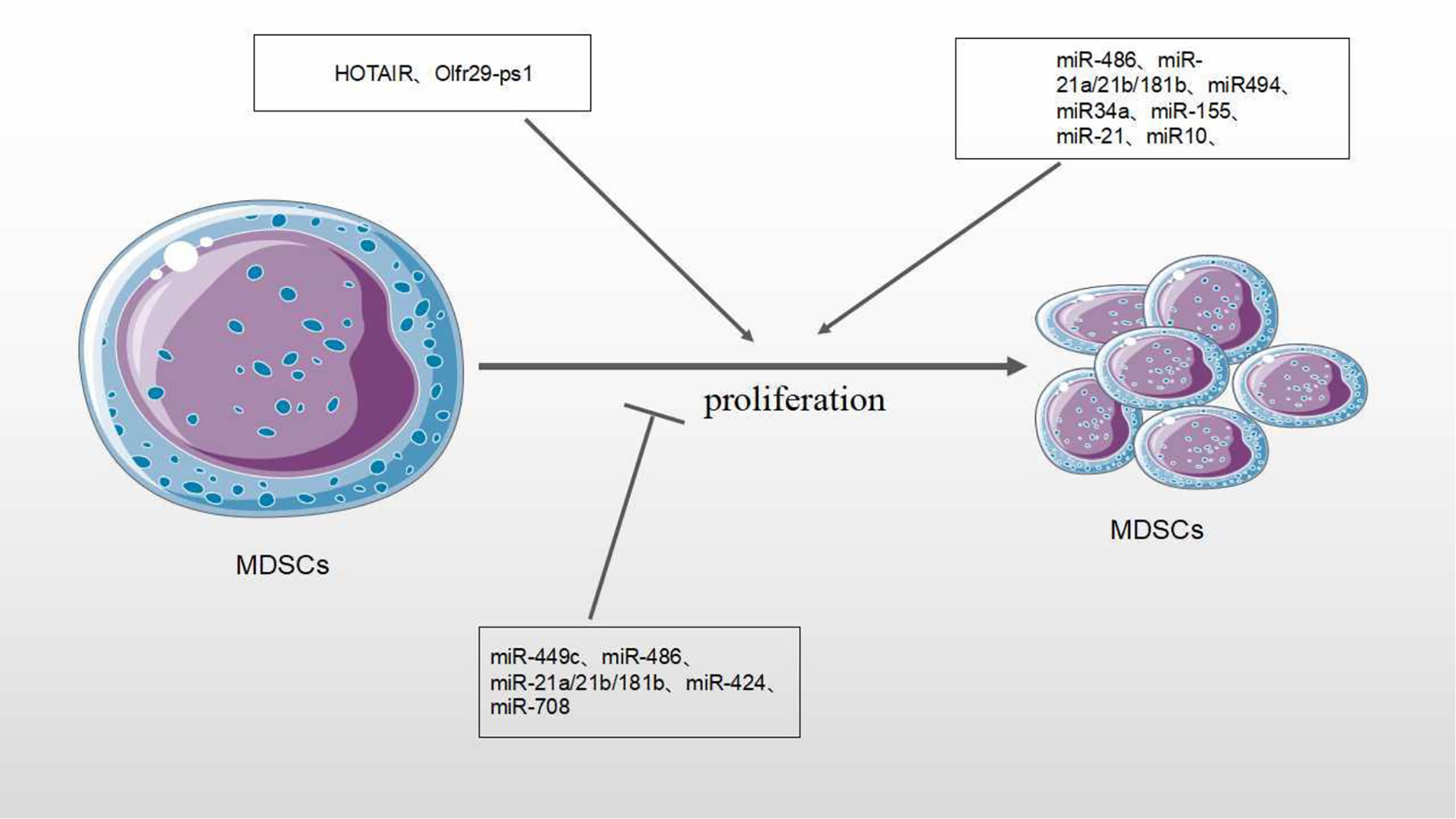

The expansion of tumor MDSCs is regulated through several pathways. Members of the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) family, as key regulatory transcription factors, may regulate many biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, metabolism and death. In TME, C/EBP maintains the critical regulation of MDSCs (37, 38) (Figure 4). In Lewis lung carcinoma and B16 melanoma, the overexpression of miR-486 promotes the proliferation of MDSCs and inhibits the differentiation and apoptosis of MDSCs through targeting C/EBPA (39). During the tumor process, when the C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2(CXCR2) is activated, the expression level of miR-449c targeting STAT6 mRNA in MDSCs is upgraded to promote the MDSC expansion (6). In 4T1-breast cancer cell, miRNA-494 which is upregulated by tumor-derived factor TGF-β1, promotes the accumulation and activity of MDSCs through targeting Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and activating Akt pathway (40). miR-155 and miR-21 promote the expansion of tumor MDSCs through targeting ship-1 and PTEN (41). Furthermore, miR-155 enhances tumor MDSC inhibitory activity through SocS1 repression (42–44). MiR-155 deficiency is also found to diminish the aggregation of functional MDSCs in the colon cancer, indicating that miRNA-155 could accelerate the accumulation of MDSCs (43–45). In lung tumor mouse model, miR-21 maintained MDSC accumulation in the TME by downregulating RUNX1 and upregulating Yes-associated protein (YAP), indicating that targeting miR-21 in MDSCs may be developed as an immunotherapeutic approach to combat lung cancer (46). In mixed leukemia, tumor-secreted factors GM-CSF/IL-6 upregulate high expression levels of miR-21a/21b/181b through STAT3/CEBPβ pathway, further diminishing the expression of WD repeat-containing protein 5 (Wdr5), absent small or homeotic-like (ASH2L) and mixed lineage leukemia 1 (MLL1), which are involved in the expansion and differentiation of G-MDSC. Furthermore, knockdown of these miRNAs diminishes the expansion of GM-CSF/IL-6-induced G-MDSCs, suggesting that miR-21a/21b/181b stimulate accumulation of MDSCs in the TME (47) (Table 1).

Figure 4 Development and role of MDSCs. MDSCs are differentiated from myeloid progenitor cells. During the differentiation process, two signaling models are mainly used: The signaling driven by tumor-derived growth factors (STAT3, IRF8, C/EBPb, Notch and NLRP3) is responsible for proliferation of immature bone marrow cells and inhibits their differentiation. The second type of signaling is mediated by factors which are produced by tumor stroma (NF-KB, STAT1, STAT6). It is responsible for pathological development of immature myeloid cells into MDSCs. The expansion and immune function of MDSCs are regulated by other different signaling mechanisms further.

Chemotherapy is one major method of cancer treatment. However, it also brings some side effects. Rong et al. found that chemotherapies (such as doxorubicin treatment) induced drug-resistance in breast cancers cells and stimulated proliferation and activation of MDSCs to inhibit T cell anti-tumor response. In doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer, Doxorubicin-induced miR-10 overexpression exaggerates the expansion and activation of MDSCs by activating the AMKP signaling pathway, leading to poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (52). Hox antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) is one lncRNA which is regarded as oncogene to play crucial roles in the progression and metastasis of several cancers such as breast, colorectal and gastric cancers. Moreover, HOTAIR overexpression causes expansion and recruitment of MDSCs in cancer cells through the release of CCL2 (5) (Table 2).

MiRNAs/lncRNAs also negatively regulate the numbers and expansion of MDSCs in the TME. In our previous studies, negative roles of miRNAs on MDSCs have been described (14). In tumor-bearing mice, miR-223 reduces the accumulation of MDSCs and inhibits immature myeloid cells differentiation into MDSCs by targeting Myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) (36, 48). In ovarian cancer treatment, Lin et al. found that dexamethasone(DEX), a synthetic glucocorticoid (GC), stimulated miR-708 overexpression by targeting RaP1B, further diminishing the expansion and number of MDSCs in TME (53). Pyzer et al. demonstrated that miR34a overexpression led to the downregulation of c-myc expression by transmembrane glycoprotein Mucin 1 (MUC1) silencing, reducing the expansion of MDSCs in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (50) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Effect of MicroRNA/LncRNA on MDSC’ proliferation in the TME. MiRNAs/LncRNAs modulate the proliferation of MDSCs through different genes and signaling pathways. In each process, microRNA/LncRNA play positive: ⊣ or negative: ⊣ roles.

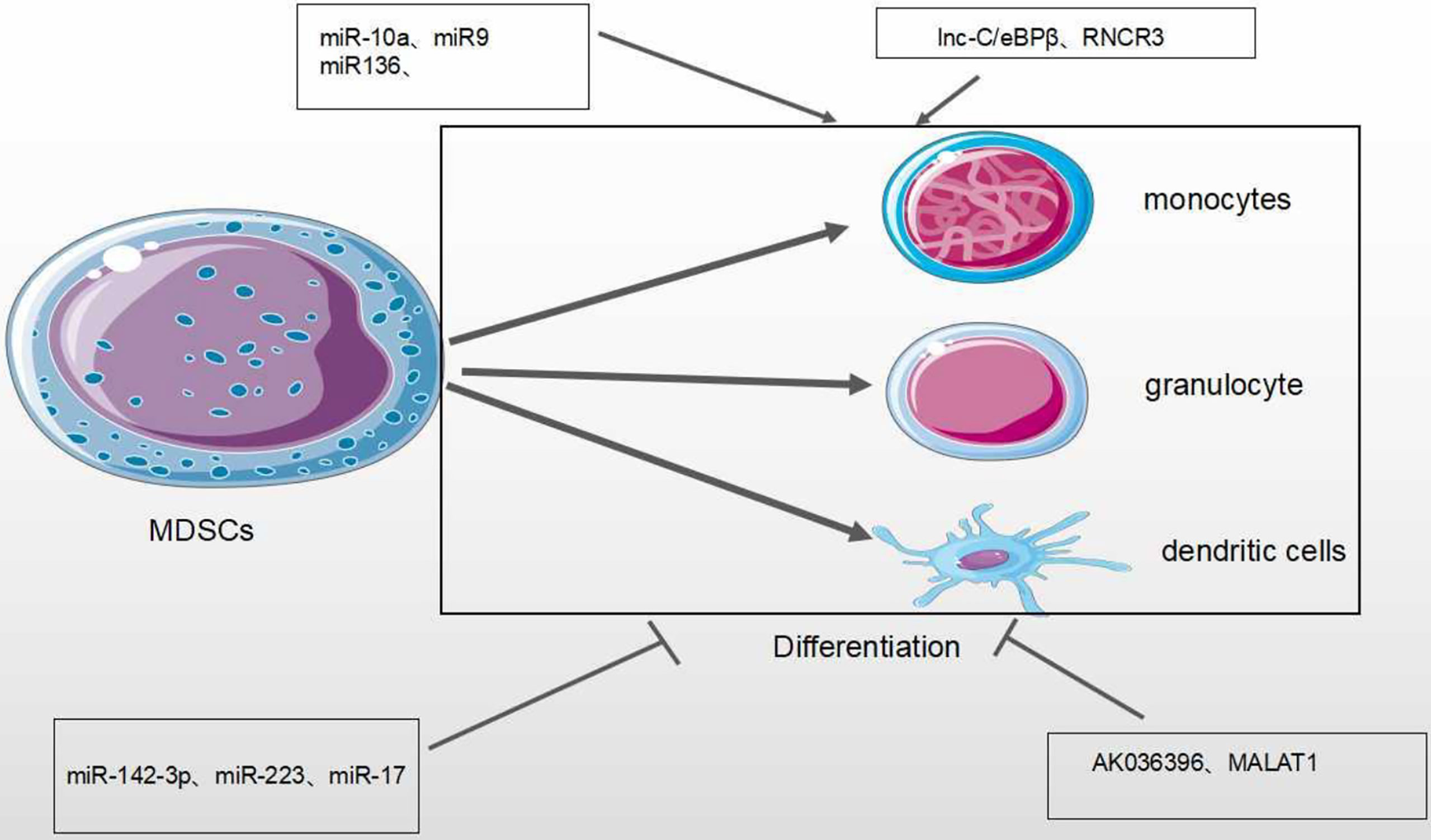

Tumor-derived factors affect different stages of myeloid cell differentiation, leading to the generation of pathologically activated M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs. The differentiation process of MDSCs is mediated through two types of signaling panels. The first type of signaling, driven by tumor-derived growth factors (STAT3, IRF8, C/EBPb, Notch and NLRP3), is responsible for proliferation of immature bone marrow cells and inhibits their differentiation. The second type of signaling is mediated by factors produced by tumor stroma (the NF-KB Pathway, STAT1, STAT6). It is responsible for pathologically activating immature myeloid cells into MDSCs (68) (Figure 4). Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that tumor-related MDSCs are differentiated into mature myeloid cells, such as macrophages or neutrophils through the regulation of different miRNAs. The downregulation of miR-9 is found to improve the differentiation of tumor MDSCs via targeting Runx1, thereby hindering tumor growth (56). Shi et al. demonstrated that TNF-α-upregulated miR-136 enhanced the differentiation of MDSCs and inhibited tumor growth by targeting Nuclear factor I A(NFIA) (57).

MiRNAs/lncRNAs also negatively modulate the differentiation of MDSCs in the TME. The upregulation of miR-34a reduces immature myeloid cells differentiation into MDSCs via TGF-β and IL-10 (51). The productions of bone marrow are altered during tumor development, leading to the accumulation of immunosuppressive cells there. miR-142-3p is found to restrain the differentiation of MDSCs into mature cells by regulating STAT3 and C/EBPβ signaling pathways (13, 14). MiR-17 family members (such as miR-17-5p, miR-20a and miR-106a) are overexpressed in human progenitor cells and inhibit AML1(the leukemia-associated transcription factor acute myeloid leukemia 1; also known as runt-related transcription factor 1, or RUNX1), leading to downregulation of M-CSFR, which prevents differentiation and activity of tumor MDSCs (63). In human acute promyelocytic leukemia, the master transcription factor PU.1 is revealed to activate the transcription of miR-424 and repress NFI-A, an inhibitor of monocyte differentiation, thereby stimulating the differentiation of MDSCs into mature cells to reduce MDSC population (55) (Table 1).

Lnc-C/EBPβ is an intermediate gene encoded on chromosome 4 that is highly conserved in mice, humans and other species. There are two subtypes of c/EBPβ: liver-rich activating protein (LAP*, LAP) and liver-rich inhibitory protein (LIP) (64). Expression of lnc-C/EBPβ in murine M-MDSCs is found to block the differentiation and inhibitory activity of MDSCs. This is through down-regulating the expression of IL-4, suggesting that it could be a potential target in tumor immunotherapy (46, 47). Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 (MALAT1), a nuclear intergenic lncRNA, is highly conserved among species and involved in various diseases. Recently, lncRNA MALAT1 was found to stimulate the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of many types of cancer cells such as cervical cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer and liver cancer (69). Knockout of MALAT1 genes in MDSCs lead to the increased number of MDSCs by the inhibition of MDSC differentiation (67). However, the regulatory mechanisms need to be investigated further (Figure 6 and Table 2).

Figure 6 Effect of MicroRNA/LncRNA on MDSC’ differentiation in the TME. MiRNAs/LncRNAs mediate the differentiation of MDSCs into monocyte, dendritic cells and neutrophils through different genes and signaling pathways. In each process, microRNA/LncRNA play positive: ⊣ or negative: ⊣ roles.

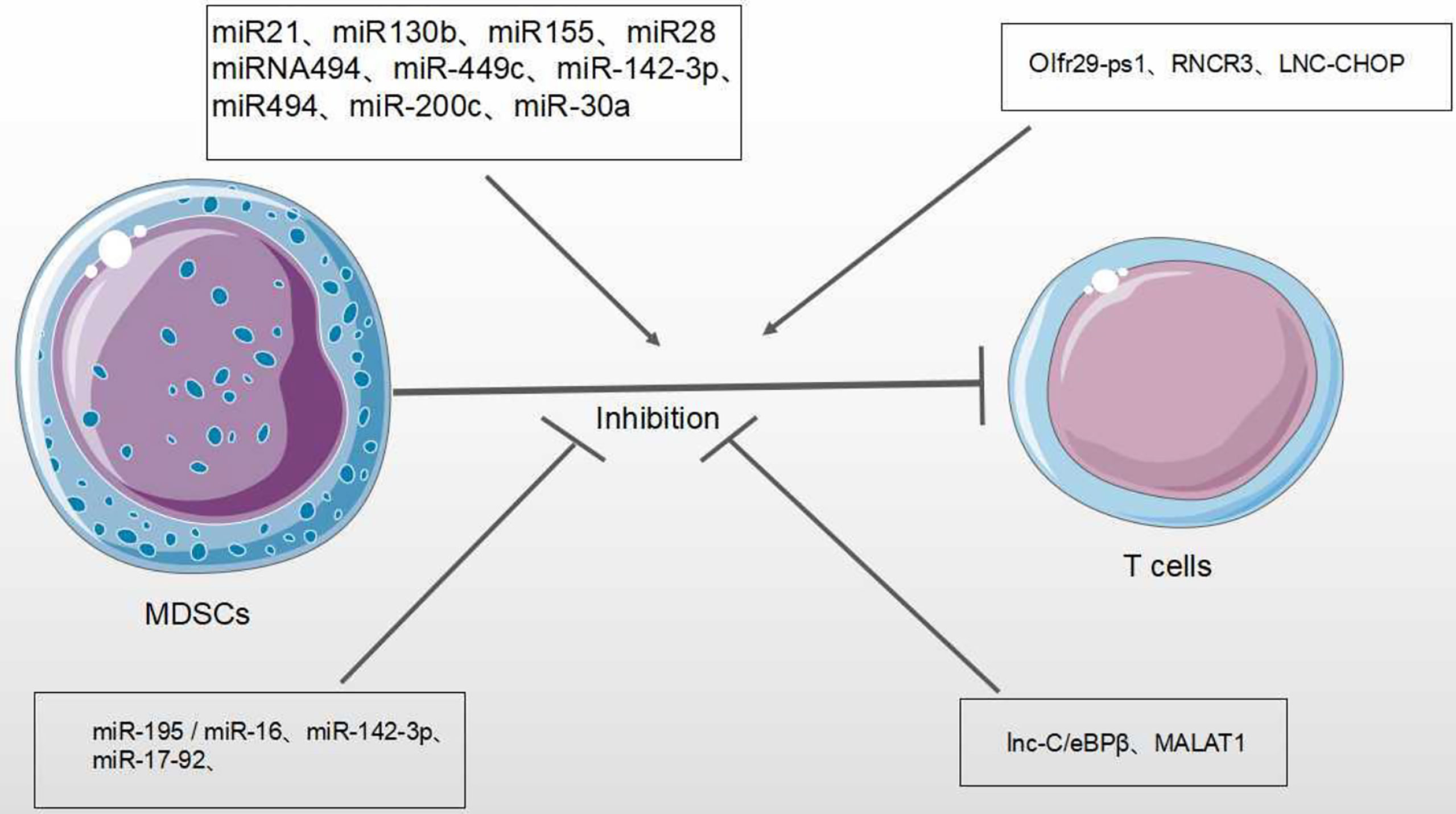

In the TME, MDSCs inhibit the anti-tumor roles of many immune cells, such as Natural Killer (NK) cells, B cells and T cells. The inhibition of T cell function is most important for evaluating the activity of MDSCs (1) (Figure 4). MiRNAs/lncRNA upregulate the activity and immunosuppressive function of MDSCs through different signaling pathways and transcription factors within TME (39, 58). In B lymphoma mouse models, the expression of miR-30a in MDSCs promotes the immunosuppressive roles of MDSCs (56). In addition, miR-30a also targets SOCS3/STAT3 to enhance the inhibitory activity of MDSCs (55). In the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) —– diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), four circulating miRNAs (miR-21, miR-130b, miR-155, and miR-28) are considered to be novel prognosis biomarkers of DLBCL and modulate RAS protein signaling transduction via Insuline-like growth factor I(IGF1) and Jun. These four miRNAs are associated with the induction of MDSCs and Th17 cells through cytokines TGFB1, IL-6 and IL-17, resulting in the immune suppression of DLBCL (58). In gastric cancer, miR-494 is positively associated with the expression of tumor-derived TGF-β which exaggerates the suppressive roles of MDSCs (49). In various tumor mouse models (such as lung cancer, breast cancer and colon cancer), it has been found that the tumor-derived factor GM-CSF induces miR-200c overexpression to activate Akt by negatively regulating the transcriptional regulator friend of Gata 2 (FOG2) and PTEN expression, further enhancing the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs (59) (Table 1).

Olfactory Receptor 29 Pseudogene 1 (Olfr29-ps1), as one lncRNA pseudogene, is conserved in vertebrates (70). Tumor-associated factors can increase the expression of Olfr29-ps1 in MDSCs. In colon and rectal cancer, Olfr29-ps1 stimulates proliferation and inhibitory activity of M-MDSC by the upregulation of pro-inflammatory factor IL-6 (16). Plasmacytoma Variant Translocation 1 (PVT1), an intergenic lncRNA, is conserved in humans and mice. In various cancers, tumor-associated factors induce the increased expression of PVT1 in MDSCs. Downregulation of Pvt1 expression in PMN-MDSCs can reduce suppressive activity of MDSCs through the reduced activity of both ROS and Arg-1. In addition, PVT1 also up-regulates the expression levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α to enhance the immunosuppressive activity of G-MDSCs under hypoxia (65). Similarly, lnc-CHOP, as an intronic lncRNA, increases the activity of both ROS and Arg-1 through interacting with both CHOP and C/EBPβ subtypes to promote C/EBPβ activity and H3K4me3 enrichment, further enhancing the suppressive activity of MDSCs within the TME (64).

Tian et al. found that lncRNA AK036396 and its target Ficolin B were highly expressed in mouse PMN-MDSCs. The downregulation of lncRNA AK036396 improved differentiation and diminished the suppressive roles of PMN-MDSCs through reduced Ficolin B protein stability. In addition, human M-ficolin, as an ortholog of mouse Ficolin B, stimulates the suppressive activity of MDSCs in patients with lung cancer through the induction of arginase1 expression. These results indicate that lncRNA AK036396 could accelerate inhibitory roles of PMN-MDSCs on T cell anti-tumor responses (66) (Table 2).

MiRNAs/lncRNAs also negatively modulate the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs in the TME. The STATs pathway is of vital regulatory function. In both lung carcinoma and 1D8 ovarian carcinoma, miR-17-92 cluster (miR-17-5p and miR-20a) could block the roles of MDSCs through targeting STATs (54). Tao et al. demonstrated that the restoration of miR-195 and miR-16 expression enhanced radiotherapy via T cell activation in TME by the inhibition of PD-L1 expression, after radiation with anti-PD-1 treatment on prostate cancer. The synergistic effect of immunotherapy and radiotherapy is associated with the proliferation of CD8+ T cells and inhibition of MDSCs and regulatory T cells (Treg), indicating that miR-195 and miR-16 may reduce the suppressive functions of MDSCs through PD-1 dependent pathways (60).

An intergenic lncRNA, HOXA Transcript Antisense RNA Myeloid-Specific1 (HOTAIRM 1) has been shown to downregulate the suppressive functions of MDSCs in the TME, since HOTAIRM1 can induce the high expression of HOXA1 in MDSCs to reduce Arg-1 expression and ROS production. In addition, increased expression of HOXA1 has been shown to decrease the percentage of MDSCs, and enhance the immune response in a tumor mouse model (26).

Therefore, miRNAs/lncRNAs effectively regulate the differentiation, proliferation, and immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs (47, 71) (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Effect of miRNA/LncRNA on MDSC’ function in the TME. MiRNAs/LncRNAs modulate the immunosuppressive roles of MDSCs on T cell anti-tumor response. In each process, miRNAs/LncRNAs play positive → or negative ⊣ roles.

Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles with size 30-150nm in diameter that are secreted by most cells (72). Exosomes are rich in genetic material and molecules: DNA, miRNA, lncRNAs, proteins and lipids, which are essential for cell-cell communication and physiological status. Moreover, exosomes are also involved in the regulation of tumor progression in the TME (11). Recently, it has been demonstrated that exosomes secreted by tumor cells play critical roles in cancer progression and invasion, including TME remodeling, tumor metastasis and tumor-associated immunosuppression (73).

MiRNAs in tumor-derived exosomes mediate the activity of MDSCs in TME through different expression patterns, transcription factors and signaling pathways (61, 74). In pancreatic cancer, the increased expression of miR-let-7i in TDEs affects the levels of myeloid inhibitory intracellular inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, IL-1β) and transcription factors, downregulating the anti-tumor immune response (74). In glioma, glioma-derived exosomes (GDEs) miR-29a and miR-92a increase the proliferation and suppressive roles of MDSCs through targeting high-mobility group box transcription factor 1 (Hbp1) and protein kinase cAMP-dependent type I regulatory subunit alpha (Prkar1a), respectively, further mediating the formation of suppressive TME (75). In LLC lung cancer model, miR-21a from LLC-Exosomes are revealed to increase both the autocrine production of IL-6 and phosphorylation levels of STAT3 by targeting Programmed cell death 4(PDCD4), thereby preventing the activation of cytotoxic CD8+T cells and enhancing the proliferation and activity of MDSCs (76). In addition, in hypoxia-induced GDEs miR-10a and miR-21 stimulate the expansion and activation of MDSCs by targeting RAR-related orphan receptor α (RORA) and PTEN (77). In breast cancer with high expression of interleukin-6, TDEs miR-9 and miR-181A activate the JAK/STAT to exaggerate the proliferation and inhibitory roles of MDSCs by targeting SOCS3 and PIAS3 (76). In gastric cancer, Ren et al. found that the TDE miR-107 prompted the proliferation and activation of MDSCs by targeting Dicer1 and PTEN (78) (Table 3).

lncRNAs are also secreted in exosomes as messengers of intercellular communication. Some lncRNAs are enriched in exosomes, while others are almost absent, suggesting that some lncrnas are selectively trafficked into exosomes. Furthermore, RNA sequencing in exosomes derived from tumors revealed that most of the non-coding transcripts of exosomes were lncRNAs (79). Meanwhile, exosomal LncRNAs are often found in clinical cancer samples, indicating that LncRNA may be a potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis. In primary urothelial bladder cancer (UBC) cells, exosomic lncRNA HOTAIR is secreted by proteins (SNAI1, TWIST1, ZEB1 and LAMB3), which regulate EMT, resulting in gene changes on epithelial cells. LncRNA ZFAS1 is found to increase in the serum exosomes of GC patients with gastric cancer (GC), suggesting that lncRNA ZFAS1 plays a positive role in the progression of gastric cancer (80). Exosomal LncRNA ZFAS1 also promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of tumor cells from esophageal carcinoma (ESCC), and inhibits the apoptosis of ESCC cells by up-regulating STAT3 and down-regulating MiR-124, leading to the carcinogenesis of ESCC. LncRNA ZFAS1 is believed to be a competitive endogenous RNA regulating MiR-124, thereby enhancing STAT3 expression (81). In bladder cancer (BCs), lncRNA-PTENP1 is found to be reduced in tissues and plasma exosomes. Cells which secrete exosomal PTENP1, deliver it to BC cells to inhibit the biological malignant behavior of BC cells by increasing apoptosis and decreasing invasion and migration (82). The regulatory mechanism of TDEs lncRNAs on MDSCs has not been clarified thoroughly. A few studies have shown that TDEs lncRNAs play the important regulatory role in TME and tumor cell interactions, accelerating tumor growth (24). TDEs lncRNAs are transported to the TME to modulate the roles of various cells, including macrophages, endothelial cells and fibroblasts (24). In liver cancer cells, lncRNA TUC339 induces M2 polarization by interacting with cytokine-cytokine receptors to exaggerate tumor metastasis (83). It is well known that lncRNA urothelial carcinoma-associated (UCA1) is an lncRNA associated with the occurrence and progression of various cancers, including colorectal cancer. Meanwhile, the mechanism of tumor-derived exosome lncRNA-UCA1 has also been studied. In colon cancer (CRC), UCA1 plays a key role in CRC tumor progression by packaging into exosome, and UCA1 sequesters mir-143 via a sponge mechanism (84) (Table 4). However, the mechanism by which exosome miRNA/LncRNA affects MDSC in TME remains to be studied.

LncRNA not only directly participates in the regulation of gene expression, but also regulates the expression of miRNA (85). miRNA can regulate mRNA expression through the miRNA response elements (MREs) of mRNA 3 ‘- UTR. LncRNA can adsorb miRNA through MREs to competitively bind miRNA as one Competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) and interfere with the binding of miRNA with downstream target genes, and then participate in various biological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and angiogenesis (86, 87). Luan et al. reported that LncRNA XLOC_006390z played a functional role as one ceRNA in cervical cancer. When XLOC_006390 is knocked out, the expression of Mir-331-3p target gene NRP2 and Mir-338-3p target gene PKM2 is significantly downregulated, further promoting the occurrence and metastasis of cervical cancer (88). MiRNA can regulate lncRNA expression as well as target mRNA expression. LncRNA structure is similar to mRNA. LncRNAs indirectly inhibit the negative regulation of miRNAs on target genes by competing with miRNA to bind the 3’-UTR of target gene mRNA. Some of lncRNAs can form miRNA precursors through intracellular shearing, and then process and generate specific miRNAs to regulate the expression of target genes and exert functions. In addition, Individual lncRNAs function as endogenous miRNA sponges and inhibit miRNA expression, further performing biological roles. Therefore, integrated analysis of the regulatory relationship between mirNA-lncrNA-mrna can explain the occurrence and development of diseases comprehensively. These indicted that miRNA may regulate lncRNA expression through the similar mechanism by which mRNA is regulated (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Mechanism of MiRNA/LncRNA interaction. The interaction mechanism between miRNAs and lncRNAs is as follows: (1) The two directly interact with each other. (2) lncRNAs inhibit miRNAs by competitively binding the 3 ‘-UTR of miRNA target mRNA. (3) lncRNAs, as ceRNA, inhibit the expression of miRNA by using the “miRNA sponge”. MiRNAs may regulate lncRNA expression through the similar mechanism by which miRNAs regulate mRNA, since LncRNA structure is similar to that of mRNA.

Mir-155 was overexpressed in MEGO1 leukemia cell line and the expression level of target lncRNA was significantly decreased. When Mir-155 was silenced, the expression of target lncRNA was significantly increased. These results indicated that miRNA could regulate the expression of lncRNA (89). lncRNAs can act as one ceRNA to sequester miRNAs, regulating the abundance and activity of miRNAs, resulting in the de-repression of genes targeted by corresponding miRNAs in cancer progression (34, 90). Recently, the regulation of lncRNA/miRNA in MDSCs has become increasingly important. Studies have speculated that lncRNA-miRNA may have synergistic effects on the roles of MDSCs. MiR-9 and or Runx1 overlapping RNA (RUNXOR) are two non-coding RNAs involved in the differentiation and activation of MDSCs. Tian et al. showed that miR-9 directly downregulated the expression of lncRNA Runx to stimulate the differentiation of MDSCs and reduce the suppressive ability of MDSCs (36). The retinal non-coding RNA3 (RNCR3), an intragenic lncRNA, which is conserved sequence in mammalian genomes, has been shown to be highly expressed in glioblastoma and prostate cancer (91). Furthermore. Shang et al. recognized that RNCR3 expression in MDSCs is upregulated by inflammatory and tumor associated factors. In the TME, the expression of RNCR3 was up-regulated in MDSC. RNCR3 may function as one ceRNA to upregulate the expression of Arg-1 and iNOS on MDSCs to enhance the roles of these MDSCs through sponge mir-185-5p which binds to CHOP to upregulate CHOP expression [104]. Therefore, those results suggest that RNCR3/miR-185-5p/Chop may strengthen suppressive roles of MDSCs in the TME.

MDSCs, as immunosuppressive cells, seriously affect the progression, invasion and metastasis of tumors, and may be used as potential targets for tumor immunotherapy. The regulatory mechanism of tumor MDSCs has been widely investigated by us and other scientists (14, 92–95). Increasing evidence demonstrated that ncRNAs, especially miRNA and lncRNAs, played the key roles in the regulation of tumor MDSCs in the TME. Here we review that MiRNA/lncRNAs regulate the biological status and functional activity of tumor MDSCs through different regulatory mechanisms. Moreover, we discuss how both exosomal miRNAs/lncRNAs and the interaction of miRNAs/lncRNAs modulate tumor MDSCs. However, In the TME, the regulation of miRNAs/lncRNA on MDSCs is affected. It remains to be explored how those dysregulated miRNAs/lncRNA are combined in the TME to act on tumor MDSCs through tumor-related signaling pathway. In addition, the regulation of miRNA/lncRNAs on MDSCs provided opportunities and challenges for targeting MDSCs immunotherapy. Moreover, these functional data of miRNA/lncRNA on tumor MDSCs are gained from animal studies, there are a few data from human patients with cancer. Thus, miRNAs/lncRNAs application for tumor MDSCs in clinical patients with cancer need be further clarified. In summary, the interaction of dysregulated miRNAs/lncRNA on tumor MDSCs with transcription factors, cofactors and chromatin modifiers may target specific signals to treat tumor MDSCs in the TME, providing novel strategies for cancer treatment.

XL and SZ wrote, reviewed, and revised manuscript, figures and tables.HS prepared the figures and tables. HL and MY reviewed and revised the manuscript. YS revised the manuscript. PQ wrote, reviewed, and revised manuscript, figures and tables. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81572868) and Science Foundation of Shandong (Grant No. ZR2018LC012).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

MDSCs, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TME, Tumor microenvironment; TGF-β, The transforming growth factor-β; IL-1β, The cytokine interleukin-1β; IFN-γ, Interferon-γ; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; CXCR2,C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2; PTEN, Phosphatase and tensin homolog; SHIP-1, Src Homology 2-containing Inositol Phosphatase-1; YAP, Yes-associated protein; ASH2L, Absent small or homeotic-like; MLL1, Mixed lineage leukemia 1; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; MEF2C, Myocyte enhancer factor 2C; RaP1B, Ras-related protein Rap1B; MUC1, Transmembrane glycoprotein Mucin 1; IRF8, Interferon regulatory factor 8; NLRP3,NACHT; LRR; and PYD domains-containing protein 3; NFIA, Nuclear factor I A; AML1, Acute myeloid leukemia 1; IGF1, Insulin-like growth factor I; FOG2, Friend of Gata 2; PDCD4, Programmed cell death 4; SOCS3, Suppressor of cytokine signalling-3; PIAS3, Protein inhibitor of activated STAT3; SNAI1, Snail family transcriptional repressor 1; Twist1, Twist-related protein 1; ZEB1, Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1; LAMB3, Laminin subunit beta-3; CHOP, C/EBP Homologous Protein.

1. Law AMK, Valdes-Mora F, Gallego-Ortega D. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as a Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Cells (2020) 9(3):561. doi: 10.3390/cells9030561

2. Dysthe M, Parihar R. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol (2020) 1224:117–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-35723-8_8

3. Nakamura K, Smyth MJ. Myeloid Immunosuppression and Immune Checkpoints in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Mol Immunol (2020) 17(1):1-12. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0306-1

4. Fleming V, Hu X, Weber R, Nagibin V, Groth C, Altevogt P, et al. Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells to Bypass Tumor-Induced Immunosuppression. Front Immunol (2018) 9:398. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00398

5. Safarzadeh E, Asadzadeh Z, Safaei S, Hatefi A, Derakhshani A, Giovannelli F, et al. MicroRNAs and lncRNAs-A New Layer of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Regulation. Front Immunol (2020) 11:572323. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.572323

6. Han X, Luan T, Sun Y, Yan W, Wang D, Zeng X, et al. MicroRNA 449c Mediates the Generation of Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Targeting Stat6. Molecules Cells (2020) 43(9):793–803. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2020.2307

7. Dai H, Xu H, Wang S, Ma J. Connections Between Metabolism and Epigenetic Modification in MDSCs. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(19):7356. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197356

8. Weber R, Riester Z, Hüser L, Sticht C, Siebenmorgen A, Groth C, et al. IL-6 Regulates CCR5 Expression and Immunosuppressive Capacity of MDSC in Murine Melanoma. J Immunother Cancer (2020) 8(2):e000949. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000949

9. Groth C, Hu X, Weber R, Fleming V, Altevogt P, Utikal J, et al. Immunosuppression Mediated by Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) During Tumour Progression. Br J Cancer (2019) 120(1):16–25. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0333-1

10. Wang W, Hong G, Wang S, Gao W, Wang P. Tumor-Derived Exosomal miRNA-141 Promote Angiogenesis and Malignant Progression of Lung Cancer by Targeting Growth Arrest-Specific Homeobox Gene (GAX). Bioengineered (2021) 12(1):821–31. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1886771

11. Zheng W, Ye W, Wu Z, Huang X, Xu Y, Chen Q, et al. Identification of Potential Plasma Biomarkers in Early-Stage Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma-Derived Exosomes Based on RNA Sequencing. Cancer Cell Int (2021) 21(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01881-4

12. Syeda ZA, Langden SSS, Munkhzul C, Lee M, Song SJ, et al. Regulatory Mechanism of MicroRNA Expression in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(5):1723. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051723

13. Daveri E, Vergani E, Shahaj E, Bergamaschi L, La Magra S, Dosi M, et al. microRNAs Shape Myeloid Cell-Mediated Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1214. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01214

14. Su Y, Qiu Y, Qiu Z, Qu P. MicroRNA Networks Regulate the Differentiation, Expansion and Suppression Function of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor Microenvironment. J Cancer (2019) 10(18):4350–6. doi: 10.7150/jca.35205

15. Lin Y-H. Crosstalk of lncRNA and Cellular Metabolism and Their Regulatory Mechanism in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(8):2947. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082947

16. Leija Montoya G, et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs: Regulators of the Activity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1734. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01734

17. Statello L, González Ramírez J, Sandoval Basilio J, Serafín Higuera I, Isiordia Espinoza M, González González R, et al. Gene Regulation by Long Non-Coding RNAs and its Biological Functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2021) 22(2):96–118. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00330-4

18. Wu P, Mo Y, Peng M, Tang T, Zhong Y, Deng X, et al. Emerging Role of Tumor-Related Functional Peptides Encoded by lncRNA and circRNA. Mol Cancer (2020) 19(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1147-3

19. Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long Non-Coding RNAs: Insights Into Functions. Nat Rev Genet (2009) 10(3):155–9. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521

20. Ferreira HJ, Esteller M. Non-Coding RNAs, Epigenetics, and Cancer: Tying it All Together. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2018) 37(1):55–73. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9715-8

21. Hombach S, Kretz M. Non-Coding RNAs: Classification, Biology and Functioning. Adv Exp Med Biol (2016) 937:3–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42059-2_1

22. de Goede OM, Nachun DC, Ferraro NM, Gloudemans MJ, Rao AS, Smail C, et al. Population-Scale Tissue Transcriptomics Maps Long non-Coding RNAs to Complex Disease. Cell (2021) 184(10):2633-48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.050

23. Yang Y, Yan X, Li X, Ma Y, Goel A. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Colorectal Cancer: Novel Oncogenic Mechanisms and Promising Clinical Applications. Cancer Lett (2021) 504:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.01.009

24. Pathania AS, Challagundla KB. Exosomal Long Non-Coding RNAs: Emerging Players in the Tumor Microenvironment. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids (2021) 23:1371–83. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.09.039

25. Li J, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Xia L, Su Z. Emerging Roles of Non-Coding RNAs in the Metabolic Reprogramming of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Immunol Lett (2021) 232:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2021.02.003

26. Tian X, Ma J, Wang T, Tian J, Zhang Y, Mao L, et al. Long Non-Coding RNA HOXA Transcript Antisense RNA Myeloid-Specific 1-HOXA1 Axis Downregulates the Immunosuppressive Activity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Lung Cancer. Front Immunol (2018) 9:473. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00473

27. Li Y, Jiang T, Zhou W, Li J, Li X, Wang Q, et al. Pan-Cancer Characterization of Immune-Related lncRNAs Identifies Potential Oncogenic Biomarkers. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):1000. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14802-2

28. Goodall GJ, Wickramasinghe VO. RNA in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2021) 21(1):22–36. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-00306-0

29. Zhao Z, Sun W, Guo Z, Zhang J, Yu H, Liu B. Mechanisms of lncRNA/microRNA Interactions in Angiogenesis. Life Sci (2019) 254:116900. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116900

30. Paraskevopoulou MD, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Analyzing MiRNA-LncRNA Interactions. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton NJ) (2016) 1402:271–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3378-5_21

31. Panni S, Lovering RC, Porras P, Orchard S. Non-Coding RNA Regulatory Networks. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech (2020) 1863(6):194417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.194417

32. Klinge CM. Non-Coding RNAs: Long Non-Coding RNAs and microRNAs in Endocrine-Related Cancers. Endocr-Relat Cancer (2018) 25(4):R259–82. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0548

33. Crudele F, Bianchi N, Reali E, Galasso M, Agnoletto C, Volinia S. The Network of non-Coding RNAs and Their Molecular Targets in Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer (2020) 19(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01181-x

34. Cheng T, Huang S. Roles of Non-Coding RNAs in Cervical Cancer Metastasis. Front Oncol (2021) 11:646192. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.646192

35. Tomar D, Yadav AS, Kumar D, Bhadauriya G, Kundu GC. Non-Coding RNAs as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Breast Cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech (2020) 1863(4):194378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.04.005

36. Shabgah AG, Salmaninejad A, Thangavelu L, Alexander M, Yumashev AV, Goleij P, et al. The Role of non-Coding Genome in the Behavior of Infiltrated Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor Microenvironment; a Perspective and State-of-the-Art in Cancer Targeted Therapy. Prog Biophys Mol Biol (2021) 161:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2020.11.006

37. Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Kaarniranta K. AMPK Activation Inhibits the Functions of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSC): Impact on Cancer and Aging. J Mol Med (Berlin Germany) (2019) 97(8):1049–64. doi: 10.1007/s00109-019-01795-9

38. Wang W, Xia X, Mao L, Wang S. The CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein Family: Its Roles in MDSC Expansion and Function. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1804. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01804

39. Jiang J, et al. MiR-486 Promotes Proliferation and Suppresses Apoptosis in Myeloid Cells by Targeting Cebpa In Vitro. Cancer Med (2018) 7(9):4627–38. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1694

40. Liu Y, Lai L, Chen Q, Song Y, Xu S, Ma F, et al. MicroRNA-494 Is Required for the Accumulation and Functions of Tumor-Expanded Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells via Targeting of PTEN. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950) (2012) 188(11):5500–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103505

41. Li L, Zhang J, Diao W, Wang D, Wei Y, Zhang CY. MicroRNA-155 and MicroRNA-21 Promote the Expansion of Functional Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950) (2014) 192(3):1034–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301309

42. Huber V, Vallacchi V, Fleming V, Hu X, Cova A, Dugo M, et al. Tumor-Derived microRNAs Induce Myeloid Suppressor Cells and Predict Immunotherapy Resistance in Melanoma. J Clin Invest (2018) 128(12):5505–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI98060

43. Wang J, Yu F, Jia X, Iwanowycz S, Wang Y, Huang S, et al. MicroRNA-155 Deficiency Enhances the Recruitment and Functions of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor Microenvironment and Promotes Solid Tumor Growth. Int J Cancer (2015) 136(6):E602–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29151

44. Kim S, Song JH, Kim S, Qu P, Martin BK, Sehareen WS, et al. Loss of Oncogenic miR-155 in Tumor Cells Promotes Tumor Growth by Enhancing C/EBP-β-Mediated MDSC Infiltration. Oncotarget (2016) 7(10):11094–112. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7150

45. Chen S, Wang L, Fan J, Ye C, Dominguez D, Zhang Y, et al. Host Mir155 Promotes Tumor Growth Through a Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell-Dependent Mechanism. Cancer Res (2015) 75(3):519–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2331

46. Haverkamp JM, Smith AM, Weinlich R, Dillon CP, Qualls JE, Neale G, et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Activity Is Mediated by Monocytic Lineages Maintained by Continuous Inhibition of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Death Pathways. Immunity (2014) 41(6):947–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.020

47. Gao Y, Shang W, Zhang D, Zhang S, Zhang X, Zhang Y, et al. Modulates Differentiation of MDSCs Through Downregulating IL4i1 With C/Ebpβ LIP and WDR5. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1661. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01661

48. Liu Q, Zhang M, Jiang X, Zhang Z, Dai L, Min S, et al. miR-223 Suppresses Differentiation of Tumor-Induced CD11b⁺ Gr1⁺ Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells From Bone Marrow Cells. Int J Cancer (2011) 129(11):2662–73. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25921

49. Moaaz M, Lotfy H, Elsherbini B, Motawea MA, Fadali G. TGF-β Enhances the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Tumor- Infiltrating CD33+11b+HLA-DR Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Gastric Cancer: A Possible Relation to MicroRNA-494. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2020) 21(11):3393–403. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.11.3393

50. Pyzer AR, Stroopinsky D, Rajabi H, Washington A, Tagde A, Coll M, et al. MUC1-Mediated Induction of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood (2017) 129(13):1791–801. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-730614

51. Wang X, Chang X, Zhuo G, Sun M, Yin K. Twist and miR-34a Are Involved in the Generation of Tumor-Educated Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Int J Mol Sci (2013) 14(10):20459–77. doi: 10.3390/ijms141020459

52. Rong Y, Yuan CH, Qu Z, Zhou H, Guan Q, Yang N, et al. Doxorubicin Resistant Cancer Cells Activate Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Releasing PGE2. Sci Rep (2016) 6:23824. doi: 10.1038/srep23824

53. Lin K-T, Sun SP, Wu JI, Wang LH. Low-Dose Glucocorticoids Suppresses Ovarian Tumor Growth and Metastasis in an Immunocompetent Syngeneic Mouse Model. PloS One (2017) 12(6):e0178937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178937

54. Zhang M, Liu Q, Mi S, Liang X, Zhang Z, Su X, et al. Both miR-17-5p and miR-20a Alleviate Suppressive Potential of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Modulating STAT3 Expression. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950) (2011) 186(8):4716–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002989

55. Zhang C, Wang S, Liu Y, Yang C. Epigenetics in Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells: A Sheathed Sword Towards Cancer. Oncotarget (2016) 7(35):57452–63. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10767

56. Tian J, Rui K, Tang X, Ma J, Wang Y, Tian X, et al. MicroRNA-9 Regulates the Differentiation and Function of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells via Targeting Runx1. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950) (2015) 195(3):1301–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500209

57. Mei S, Liu Y, Wu X, He Q, Min S, Li L, et al. TNF-α-Mediated microRNA-136 Induces Differentiation of Myeloid Cells by Targeting NFIA. J Leukocyte Biol (2016) 99(2):301–10. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1A0115-032RR

58. Sun R, Zheng Z, Wang L, Cheng S, Shi Q, Qu B, et al. A Novel Prognostic Model Based on Four Circulating miRNA in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Implications for the Roles of MDSC and Th17 Cells in Lymphoma Progression. Mol Oncol (2021) 15(1):246–61. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12834

59. Mei S, Xin J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Liang X, Su X, et al. MicroRNA-200c Promotes Suppressive Potential of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Modulating PTEN and FOG2 Expression. PloS One (2015) 10(8):e0135867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135867

60. Tao Z, Xu S, Ruan H, Wang T, Song W, Qian L, et al. MiR-195/-16 Family Enhances Radiotherapy via T Cell Activation in the Tumor Microenvironment by Blocking the PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint. Cell Physiol Biochem: Int J Exp Cell Physiol Biochem Pharmacol (2018) 48(2):801–14. doi: 10.1159/000491909

61. Wang W, Han Y, Jo HA, Lee J, Song YS. Non-Coding RNAs Shuttled via Exosomes Reshape the Hypoxic Tumor Microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol (2020) 13(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00893-3

62. Xu Z, Ji J, Xu J, Li D, Shi G, Liu F, et al. MiR-30a Increases MDSC Differentiation and Immunosuppressive Function by Targeting SOCS3 in Mice With B-Cell Lymphoma. FEBS J (2017) 284(15):2410–24. doi: 10.1111/febs.14133

63. Chen S, Zhang Y, Kuzel TM, Zhang B. Regulating Tumor Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by MicroRNAs. Cancer Cell Microenviron (2015) 2(1):e637. doi: 10.14800/ccm.637

64. Gao Y, Wang T, Li Y, Zhang Y, Yang R. Promotes Immunosuppressive Function of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor and Inflammatory Environments. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950) (2018) 200(8):2603–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701721

65. Zheng Y, Tian X, Wang T, Xia X, Cao F, Tian J, et al. Long Noncoding RNA Pvt1 Regulates the Immunosuppression Activity of Granulocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor-Bearing Mice. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0978-2

66. Tian X, Zheng Y, Yin K, Ma J, Tian J, Zhang Y, et al. LncRNA Inhibits Maturation and Accelerates Immunosuppression of Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Enhancing the Stability of Ficolin B. Cancer Immunol Res (2020) 8(4):565–77. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0595

67. Zhou Q, Tang X, Tian X, Tian J, Zhang Y, Ma J, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 Negatively Regulates MDSCs in Patients With Lung Cancer. J Cancer (2018) 9(14):2436–42. doi: 10.7150/jca.24796

68. Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Immunol Res (2017) 5(1):3–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0297

69. Wang Z, Wang X, Zhang T, Su L, Liu B, Zhu Z, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 Promotes Gastric Cancer Progression via Inhibiting Autophagic Flux and Inducing Fibroblast Activation. Cell Death Dis (2021) 12(4):368. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03645-4

70. Shang W, Gao Y, Tang Z, Zhang Y, Yang R. The Pseudogene Promotes the Suppressive Function and Differentiation of Monocytic MDSCs. Cancer Immunol Res (2019) 7(5):813–27. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0443

71. Wencong, et al. The Pseudogene Olfr29-Ps1 Promotes the Suppressive Function and Differentiation of Monocytic MDSCs. Cancer Immunol Res (2019) 7(5):813-27. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0443

72. Tang Z, Li D, Hou S, Zhu X. The Cancer Exosomes: Clinical Implications, Applications and Challenges. Int J Cancer (2020) 146(11):2946–59. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32762

73. Li X, Liu Y, Zheng S, Zhang T, Wu J, Sun Y, et al. Role of Exosomes in the Immune Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer. Oncol Lett (2021) 21(5):377. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12638

74. Tan S, Xia L, Yi P, Han Y, Tang L, Pan Q, et al. Exosomal miRNAs in Tumor Microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR (2020) 39(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01570-6

75. Elewaily MI, Elsergany AR. Emerging Role of Exosomes and Exosomal microRNA in Cancer: Pathophysiology and Clinical Potential. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2021) 147(3):637–48. doi: 10.1007/s00432-021-03534-5

76. Zhang X, Li F, Tang Y, Ren Q, Xiao B, Wan Y, et al. miR-21a in Exosomes From Lewis Lung Carcinoma Cells Accelerates Tumor Growth Through Targeting PDCD4 to Enhance Expansion of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Oncogene (2020) 39(40):6354–69. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01406-9

77. Guo X, Qiu W, Liu Q, Qian M, Wang S, Zhang Z, et al. Immunosuppressive Effects of Hypoxia-Induced Glioma Exosomes Through Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells via the miR-10a/Rora and miR-21/Pten Pathways. Oncogene (2018) 37(31):4239–59. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0261-9

78. Ren W, Zhang X, Li W, Feng Q, Feng H, Tong Y, et al. Exosomal miRNA-107 Induces Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Expansion in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Manage Res (2019) 11:4023–40. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S198886

79. Xie Y, Dang W, Zhang S, Yue W, Yang L, Zhai X, et al. The Role of Exosomal Noncoding RNAs in Cancer. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0984-4

80. Pan L, Liang W, Fu M, Huang ZH, Li X, Zhang W, et al. Exosomes-Mediated Transfer of Long Noncoding RNA ZFAS1 Promotes Gastric Cancer Progression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2017) 143(6):991–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2361-2

81. Li Z, Qin X, Bian W, Li Y, Shan B, Yao Z, et al. Exosomal lncRNA ZFAS1 Regulates Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Proliferation, Invasion, Migration and Apoptosis via microRNA-124/STAT3 Axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR (2019) 38(1):477. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1473-8

82. Zheng R, Du M, Wang X, Xu W, Liang J, Wang W, et al. Exosome-Transmitted Long non-Coding RNA PTENP1 Suppresses Bladder Cancer Progression. Mol Cancer (2018) 17(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0880-3

83. Han S, Qi Y, Luo Y, Chen X, Liang H. Exosomal Long Non-Coding RNA: Interaction Between Cancer Cells and Non-Cancer Cells. Front Oncol (2020) 10:617837. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.617837

84. Luan Y, Li X, Luan Y, Zhao R, Li Y, Liu L, et al. Circulating lncRNA UCA1 Promotes Malignancy of Colorectal Cancer via the miR-143/MYO6 Axis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids (2020) 19:790–803. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.12.009

85. Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA Hypothesis: The Rosetta Stone of a Hidden RNA Language? Cell (2011) 146(3):353–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014

86. Botla SK, Savant S, Jandaghi P, Bauer AS, Mücke O, Moskalev EA, et al. Early Epigenetic Downregulation of microRNA-192 Expression Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Progression. Cancer Res (2016) 76(14):4149–59. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0390

87. Ouyang H, Gore J, Deitz S, Korc M. microRNA-10b Enhances Pancreatic Cancer Cell Invasion by Suppressing TIP30 Expression and Promoting EGF and TGF-β Actions. Oncogene (2014) 33(38):4664–74. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.405

88. Luan X, Wang Y. LncRNA XLOC_006390 Facilitates Cervical Cancer Tumorigenesis and Metastasis as a ceRNA Against miR-331-3p and miR-338-3p. J Gynecol Oncol (2018) 29(6):e95. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e95

89. Calin GA, Liu CG, Ferracin M, Hyslop T, Spizzo R, Sevignani C, et al. Ultraconserved Regions Encoding ncRNAs are Altered in Human Leukemias and Carcinomas. Cancer Cell (2007) 12(3):215–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.027

90. Zuo L, Su H, Zhang Q, Wu WY, Zeng Y, Li XM, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of lncRNAs N 6 -Methyladenosine Modification in Colorectal Cancer. Aging (Albany NY) (2021) 12(3):4182–98. doi: 10.18632/aging.202383

91. Mercer TR, Qureshi IA, Gokhan S, Dinger ME, Li G, Mattick JS, et al. Long Noncoding RNAs in Neuronal-Glial Fate Specification and Oligodendrocyte Lineage Maturation. BMC Neurosci (2010) 11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-14

92. Qu P, Boelte KC, Lin PC. Negative Regulation of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Cancer. Immunol Investigat (2012) 41(6-7):562–80. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2012.685538

93. Ben-Meir K, Twaik N, Baniyash M. Plasticity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Cancer. Curr Opin Immunol (2018) 51:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.03.009

94. Ben-Meir K, Twaik N, Baniyash M. Plasticity and Biological Diversity of Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells. Curr Opin Immunol (2018) 51:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.03.015

Keywords: myeloid-derived suppressor cells, microRNAs, lncRNAs, networks, tumor microenvionment

Citation: Liu X, Zhao S, Sui H, Liu H, Yao M, Su Y and Qu P (2022) MicroRNAs/LncRNAs Modulate MDSCs in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 12:772351. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.772351

Received: 08 September 2021; Accepted: 14 February 2022;

Published: 14 March 2022.

Edited by:

Shiv K. Gupta, Mayo Clinic, United StatesReviewed by:

Erbao Bian, Second Hospital of Anhui Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Liu, Zhao, Sui, Liu, Yao, Su and Qu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanping Su, c3UteWFucGluZ0AxNjMuY29t; Peng Qu, cGVuZ3F1amkyMDAwQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.