94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol., 01 November 2022

Sec. Head and Neck Cancer

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.1017630

Lirui Zhang†

Lirui Zhang† Qiaoshi Xu†

Qiaoshi Xu† Huan Liu

Huan Liu Bo Li

Bo Li Hao Wang

Hao Wang Chang Liu

Chang Liu Jinzhong Li

Jinzhong Li Bin Yang

Bin Yang Lizheng Qin

Lizheng Qin Zhengxue Han

Zhengxue Han Zhien Feng*

Zhien Feng*Objectives: The prognosis, choice of reconstruction and the quality of life (QOL) after salvage surgery (SS) for extensively locoregional recurrent/metastatic head and neck cancer (R/M HNC) is an important issue, but there are few reports at present.

Materials and methods: We analyzed extensively locoregional R/M HNC patients from March 1, 2015, to December 31, 2021 who underwent SS with latissimus dorsi or pectoralis major musculocutaneous flaps. QOL were accessed using QLQ-H&N35 and UW-QOL questionnaire. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare difference between pre- and post-QOL and Kaplan-Meier curves were used in estimate overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). The literature review summarized recent 10 years clinical trials of nonoperative treatment in R/M head and neck cancer.

Results: 1362 patients were identified and 25 patients were analyzed after screened. Median age at surgery was 59 years (range 43-77), 15/25(60%) were male and 22/25(88%) chose latissimus dorsi flap. Better mean pain score after applying massive soft tissue flaps revealed relief of severe pain(p<0.001) which strongly associated with improvement of QOL. The improved mean overall QOL score after surgery revealed a better QOL(p<0.001). As of June 1, 2022, 11/25 (44%) of the patients were alive. The 1-year, 2-year OS after SS was 58.4% and 37.2%, while the 1-year, 2-year DFS was 26.2% and 20.9%. The median OS of our study was better than nonoperative treatment of 11 included clinical trials.

Conclusions: R/M HNC patients underwent SS can obtain survival benefit. The application of massive soft tissue flap in SS could significantly enhance the QOL for patients with extensively locoregional R/M HNC, especially by relieving severe pain.

Currently, surgery with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is the most common treatment utilized for head and neck cancers (HNCs) (1–4). Nevertheless, recurrence is still common, with a rate of 25%-50% (5), especially for advanced stage cancer (Stage III or IV) (6). Extensively locoregional recurrent/metastatic R/M tumors in the head and neck region always lead to severe pain, appearance changes, swallowing dysfunction, chewing and despair, which profoundly impairs quality of life (QOL). Accordingly, R/M HNC involving key structural organs are a huge challenge in surgical treatment, both in therapy selection and implementation.

The term “salvage surgery” (SS) is currently defined as a final attempt to resect residual and recurrent tumors after definitive treatment, including surgical treatment (7). Surgery for patients with extensively recurrent head and neck tumors faces many problems, including the invasion of vital structures such as the skull base and the carotid artery which tightly related to the patient’ life safety and poor vascular conditions (8). Meanwhile, resection of a large tumor will form large area defect. Reconstruction with flaps has been applied to solve these issues in SS. Given the patients’ difficulties, the latissimus dorsi flap and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap are two common choices due to their massive size and high success rate (9, 10).

Multiple studies on SS found good efficacy (11), with five-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates of 42% and 47%, respectively, and it has been advocated as the last curative option for recurrent advanced head and neck cancer (12–14). Although the oncological outcomes of SS showed a substantial improvement, the evaluation of the quality of life before and after salvage surgery has been only poorly analyzed, and the significance of these flaps for the enhancement of QOL after SS is still unknown. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaire and University of Washington Quality of Life (UW-QOL) questionnaire are the two most frequently used questionnaires for globally measuring the QOL of patients with head and neck tumor (15).

Our research aimed to investigate whether SS can improve the overall survival time, and the application of latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flaps in SS is reliable and can improve the QOL of patients with extensively locoregional R/M HNC. In this study, we examined the QOL after SS for patients with R/M HNC using the validated instruments QLQ-H&N35 and UW-QOL.

The data used in this study originated from POROMS, a Prospective, Observational, Real-world Oral Malignant Tumors Study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02395367). This database was established on January 1, 2015, based on the Department of Oral Maxillofacial Head and Neck Oncology, Beijing Stomatological Hospital. In this study, the initial study sample included all treated patients with oncologic malignancy from March 1, 2015, to December 31, 2021. From these patients, we selected eligible patients using the following criteria: (1) patients underwent resection surgery plus reconstruction with latissimus dorsi or pectoralis major myocutaneous flaps; (2) patients with a tumor that recurred more than once (including locoregional recurrence and a secondary primary tumor in the oral cavity, or distant oligometastases); (3) more than 2 cancer centers suggest quit or palliative care; (4) patients with a tumor invading vital structures (internal carotid artery, skull base, pterygoid plate, masticatory space, parapharyngeal space, trachea and suprasternal fossa, and orbit); (5) pre-operative and post-operative QOL questionnaires were integrally available with the instruments QLQ-H&N35 and UW-QOL; and (6) patients provided informed consent. Patients who were lost to follow-up or refused to participate were excluded from the study. This study was approved by the Beijing Stomatological Hospital ethics committee and conducted with the informed consent of the patients.

Pre- and post-operative QOL were measured using the QLQ-H&N35 (version 3.0) and UW-QOL (version 4.0). The EORTC Questionnaire has been well accepted and is widely used to evaluate the QOL of cancer patients (16–18). It contains a general questionnaire, QLQ-Core-30, and a specific module, QLQ-H&N35, which evaluates the common topics and topics specific to cancer patients, respectively. The QLQ-H&N35 is comprised of 7 multi-item scales assessing pain, problems with swallowing, senses (taste and smell), speech, social eating, social contact and sexuality and 11 single items assessing problems with teeth, opening the mouth, dry mouth, sticky saliva, coughing, feeling ill, and the use of analgesics, nutritional supplements, feeding tubes, weight gain and weight loss. The questions were scored on a four-point Likert scale (“not at all,” “a little,” “some,” “very much”), whereas the last five items were answered in the form of yes/no. The scale scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores suggesting more severe symptomatology or problems (16).

Another questionnaire with the same application is the UW-QOL questionnaire, which was developed in 1993 by Hassan and Weymuller (19). It consists of 12 single question domains, including physical function domains with chewing, speech, swallowing, taste, saliva, and appearance, and social function domains with anxiety, mood, pain, activity, recreation, and shoulder function (20). In addition, it also has three global questions, one about how patients feel compared to the month before they developed cancer, one about their health-related QOL during the last 7 days and one about their overall QOL during the last 7 days. For the UW-QOL, each domain has 3-6 options scored evenly from 0 to 100, with higher scores implying better QOL.

Patient demographic characteristics (age, sex), history of treatment (whether they underwent radiotherapy, chemotherapy and other treatments), recurrent tumor characteristics (pathologic type, invasion of important structures), SS details (selection of flaps, the results of resection margins) and follow-up data (adjuvant therapy, post-operative complications, DFS and OS) were extracted from the mentioned database.

All patients registered in the database completed the pre-operative QOL questionnaires by themselves. Post-operative QOL questionnaires were completed 90 days ±7 days after surgery. We encouraged the patients to return to the outpatient clinic to complete the questionnaires to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the data, and telephone follow-up was only used for patients with poor physical condition who could not return to the hospital or died.

A search of human randomized controlled trial (RCT) in English language was completed in PubMed database from 2012 to 2022. The search queries contain MeSH terms of “chemotherapy” OR “molecular targeted therapy” OR “palliative care” OR “immunotherapy” AND “head and neck neoplasms” AND “recurrence” AND “phase 3 or phase III”. The retrieved articles will be further screened according to the exclusion criteria: (1) Nasopharyngeal cancer (21); (2) Repeated analysis of the same clinical trial sample; (3) Without complete description of survival time. The treatment plan and survival date of the finally included trials were extracted.

Descriptive analysis was used to identify the sample characteristics. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a nonparametric test for two paired samples, was used to detect differences between pre- and post-QOL. Significance was established as p<0.05. OS and DFS were calculated by Kaplan–Meier analysis. The calculation starting point of OS and DFS was the time completing SS. The end point of OS was all-cause death or the last follow-up, while that of DFS was first recurrence, metastasis, or death. The OS time of the patients in this study was compared with the treatment of nonoperative therapy in the literature review, and the difference was displayed with a forest diagram. All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical software program SPSS version 26.0.

From January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2021, 1362 patients were enrolled in our program; 53 patients used a latissimus dorsi flap, and 9 patients used a pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap. Among these patients, 32 patients were excluded due to treatment of the primary tumor or replacement of a previous flap. Finally, 25 patients met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for the study (Figure 1). The median age was 59 years (range 43-77) at the time of surgery, and the proportion of men (60%) was slightly higher than that of women (40%). The predominant pathologic type was carcinoma (84%). The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

In terms of the history of prior treatments, 8(32%) patients received resection of the primary tumor alone. 6 (24%) patients underwent resection with reconstruction, while with neck dissection were 7(28%). The remaining 4(16%) patients underwent resection with both neck dissection and reconstruction. The number of patients who received radiotherapy, chemotherapy or other treatments was 8(32%), 4(16%), and 2 (8%), respectively.

The mastication muscle space and parapharyngeal space were the most frequently involved structures in 24 (96%) patients, while invasion of the skull base involved the internal carotid artery, pterygoid process, and orbit in 8(32%), 2(8%), 7(28%), and 2(8%) patients, respectively. Twelve patients presented with invasion of only one structure, eight patients had two invaded structures, and five patients had three invaded structures. In view of organ preservation and the need to avoid fatal complications, approximately 29% of patients could not obtain a negative margin.

Based on the follow-up notes, 7(28%) and 6(24%) patients underwent concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy, respectively; 2(8%) patients received both, and 10(40%) did not receive any adjuvant therapy. The incidence of complications was low, with only 4(16%) patients manifesting maxillofacial edema, flap crisis, pain, bone exposure and/or pharyngo-cutaneous fistula (Table 1).

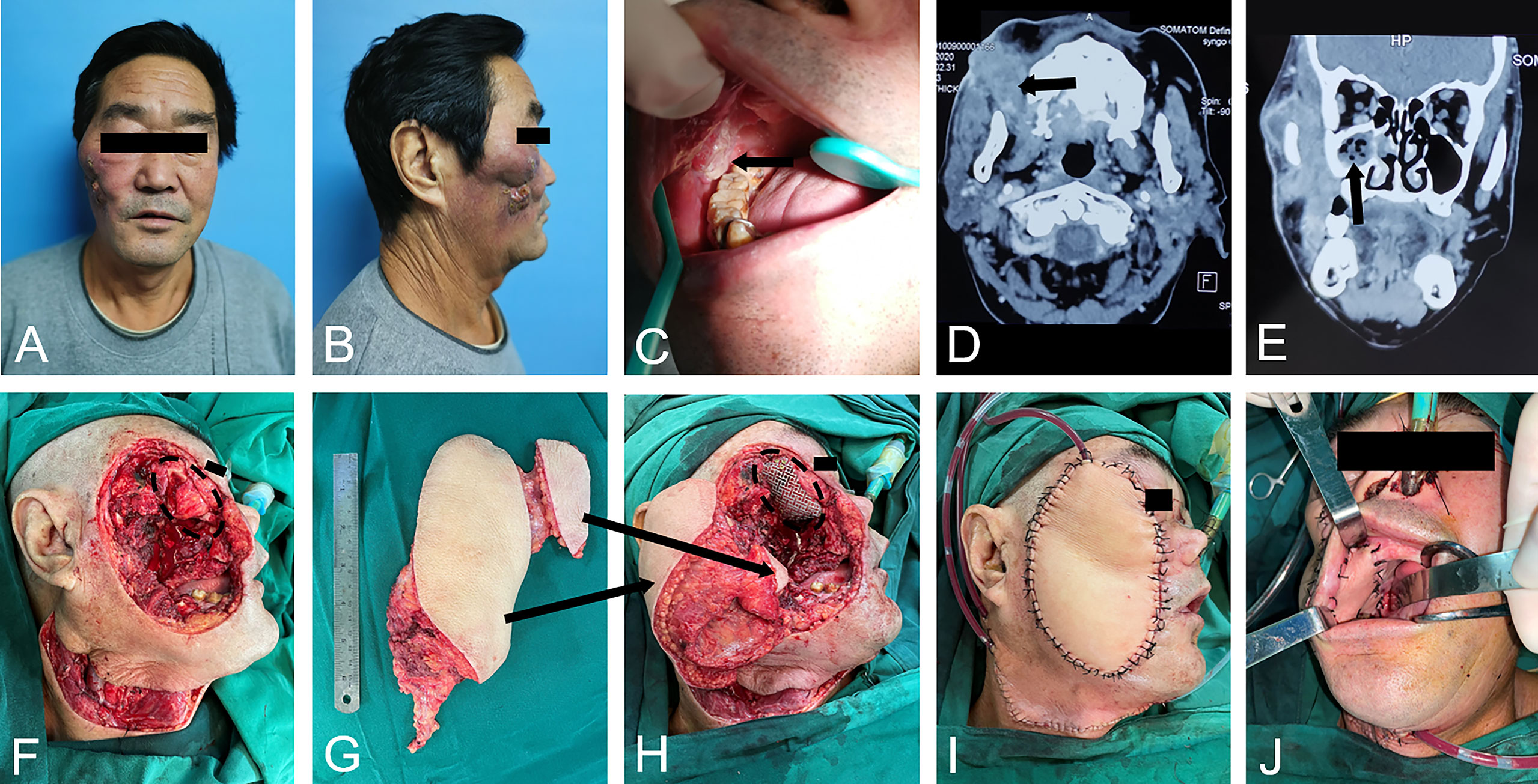

To protect the vital structures and improve the QOL, a latissimus dorsi flap and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap were used for reconstruction. Among 25 patients, 22 patients chose the latissimus dorsi flap (88%), and 3 patients chose the pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap (12%). To show the restoration and reconstruction more intuitively, the operation process of a typical salvage surgical case is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 A typical salvage surgery case. (A-C). primary tumor outside and inside the mouth; (D, E). radiographic images presented tumor encroached maxillary and mandibular bone, maxillary sinus and orbital floor; (F). excision of tumor led to orbit exposure; (G, H). reconstruction with double-skin paddle free latissimus dorsi flaps and Titanium mesh implantation of right orbit; (I, J). immediate postoperative images.

This is a case of a large recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) of the maxillofacial region in which the lesions involved the oral cavity, skin of the zygomatic face, outer orbital, sinuses and deep facial area (Figure 2A-C). Radiographic images presented tumor-encroached maxillary and mandibular bone, maxillary sinus and orbital floor (Figure 2D, E). The patient underwent extensive resection, including the maxilla, mandibular ramus, oral buccal mucosa and gingiva, zygomatic facial skin and lateral orbital bone wall (Figure 2F). Then, the large defect was reconstructed with double-skin paddle-free latissimus dorsi flaps and titanium mesh implantation of the right orbit after all margins were negative (Figure 2G-J). This case obtained a primary cure and received a satisfactory quality of life, and the tumor had not recurred at 1 year.

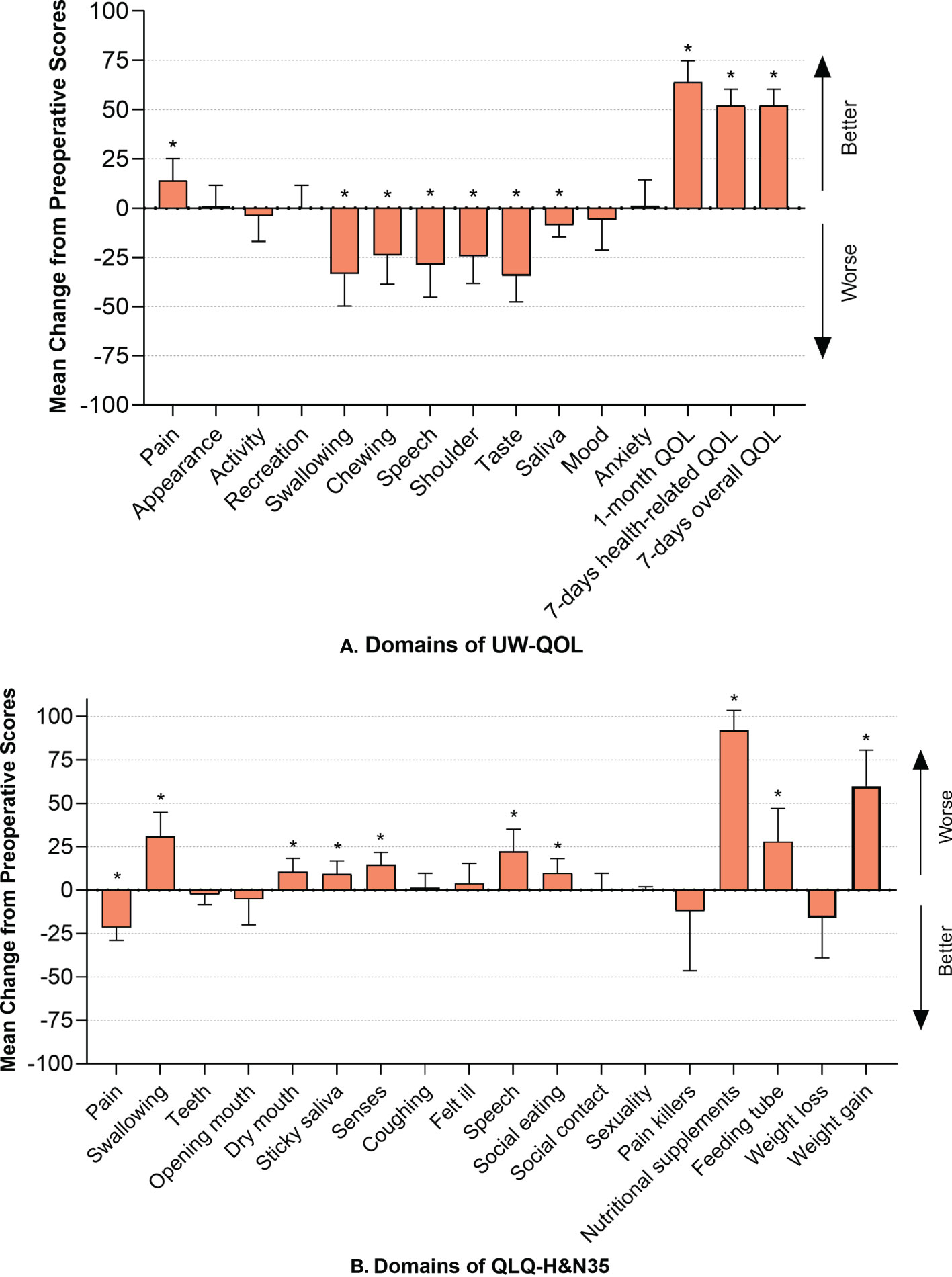

The UW-QOL scores before and after SS are shown in Table 2. The mean overall QOL score prior to SS was 29.00 (95% CI, 24.12-33.88), while that after SS was 81.00 (95% CI, 72.96-89.04). This revealed significant differences (p<0.001) with a better QOL after SS. Among the 12 functional domains, the lowest pre-operative scores were found for pain (58.00), and the lowest post-operative scores were found for chewing (34.00). In comparative analyses of the UW-QOL scores between pre- and post- operative surgery, significant differences were found in 7 functional domains: pain (p=0.018), swallowing (p=0.001), chewing (p=0.005), speech (p=0.004), shoulder function (p=0.002), taste (p<0.001), and saliva (p=0.011). Among the former items, the domain “pain” achieved better scores, which implied relief after SS; however, worse scores were found in others, hinting at diminished functions (Figure 3A).

Figure 3 (A) Mean change from preoperative scores in UW-QOL and I bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks represent significant difference between pre- and post- scores using Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Significance was established as p<0.05; (B) Mean change from preoperative scores in H&N35 and I bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks represent significant difference between pre- and post- scores using Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Significance was established as p < 0.05.

The results of the QLQ-H&N35 were analogous to those of the UW-QOL and are listed in Table 3. Pain (p<0.001) was significantly relieved, while dysfunction was found concerning swallowing (p=0.001), speech (p=0.003), social eating (p=0.018), and senses (p=0.001). Symptoms of dry mouth and sticky saliva were more severe, with P values of 0.017 and 0.023, respectively, compared to prior to surgery. A higher frequency of the use of nutritional supplements (p<0.001) and feeding tubes (p=0.008) was also found, accompanied by an increase in weight (p<0.001) (Figure 3B).

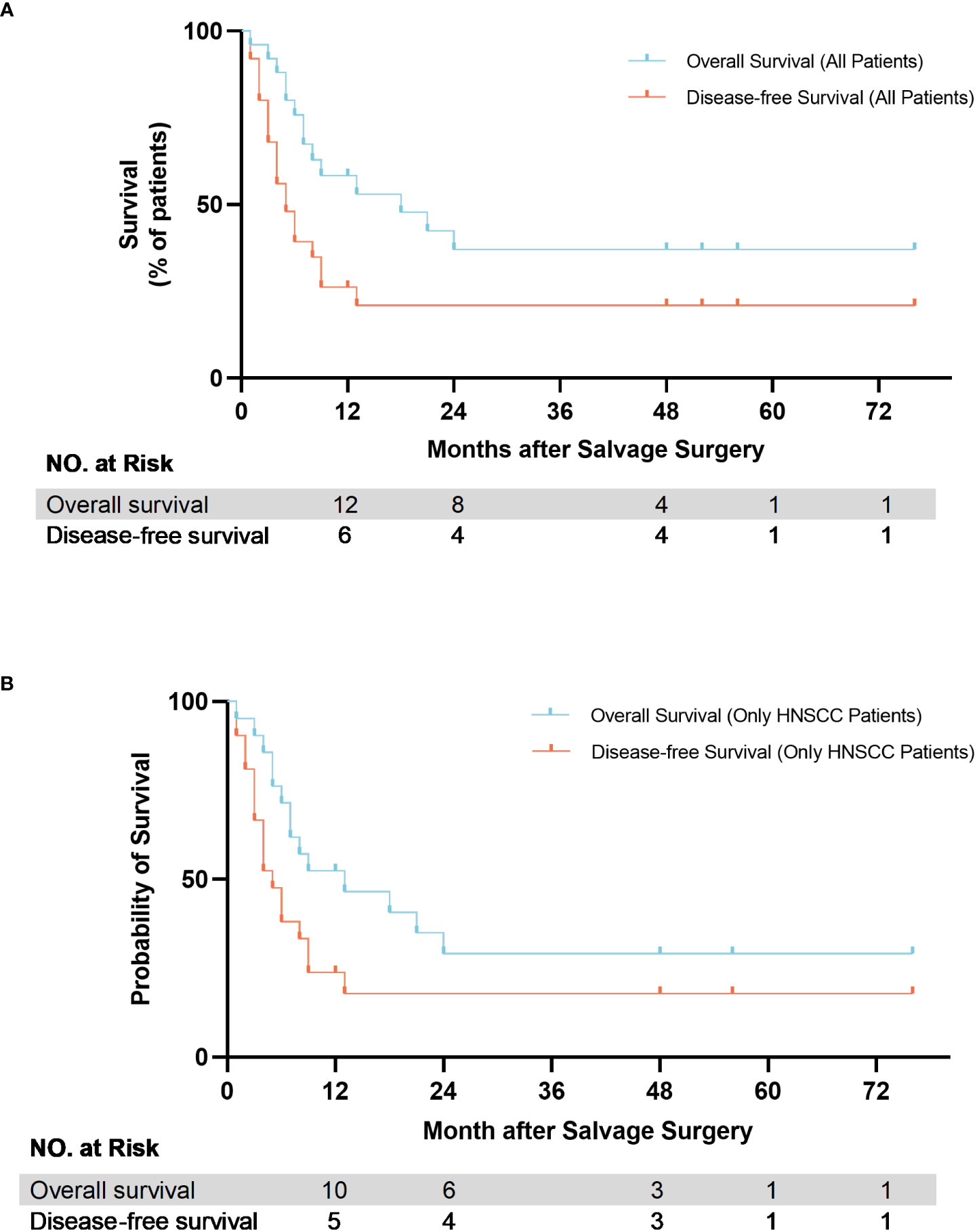

As of June 1, 2022, 11/25 (44%) of the patients in our study were still alive. The 1-year, 2-year OS after SS was 58.4% and 37.2%, respectively, while the DFS was 26.2% and 20.9%, respectively. The median OS of all 25 patients was 18.00 months (95%CI, 2.17-33.83), and the median DFS was 5.00 months (95%CI, 2.66-7.34). In pool of 21 HNSCC patients, the 1-year, 2-year OS after SS was 52.4% and 29.1%, respectively, while the DFS was 23.8% and 17.9%, respectively. The median OS was 13.00 months (95%CI, 0.00-26.30), and the median DFS was 5.00 months (95%CI, 2.76-7.24). The Kaplan–Meier curve showed the OS and DFS of all patients and HNSCC patients (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) of patients after salvage surgery. (A) All patients; (B) HNSCC patients only.

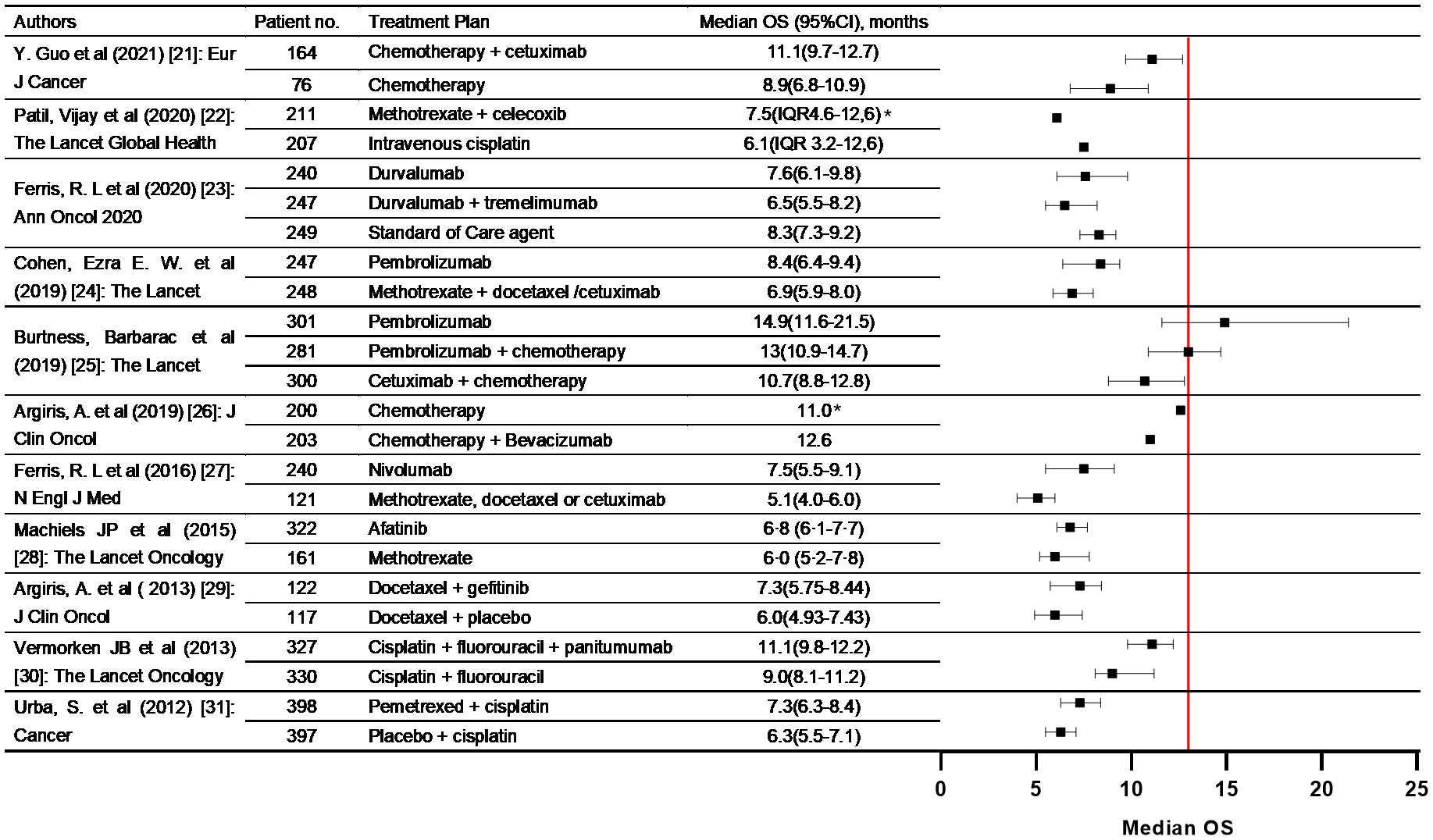

A total of 11 RCTs were included in our review (22–32). 5509 pathologically confirmed R/M HNSCC patients were included in trials and underwent single chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, immunotherapy or combination therapy. The reported date of median OS ranged from 5.1 months to 14.9 months. In our study, the median OS of all 21 patients only affected by squamous cell carcinoma was 13.00 months (95%CI, 0.00-26.30). Compared to these nonoperative treatment in R/M HNSCC, median OS of our study is apparently better. The forest plot showed the median OS with 95%CI of all the former trials (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Summary of phase III clinical trials included in the literature review that evaluating nonoperative treatment in R/M HNSCC patients. The forest plots were built comparing median OS between our study and included trials. (* 95%CI was not presented in the original survival data.).

SS is defined as an attempt to resect residual and recurrent HNCs. In our study, all 25 patients had undergone radical surgery 1-4 times, extensive relapse still occurred, and the tumor had invaded the internal carotid artery, skull base, pterygoid plate, masticatory space, parapharyngeal space or orbit which are generally considered unresectable (33). Under such circumstances, the patient has almost lost all courage to survive, and SS is the last attempt to defeat the cancer.

In this research, we applicate latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flaps for restoration and reconstruction after SS for patients with R/M HNC The head and neck region has many important structures and many functions. Based on this, surgery for head and neck tumors has a prominent impact on their QOL, and reconstruction has great meaning. For patients with extensive R/M HNC, the significance of repair and reconstruction lies in: 1. Coverage of important anatomical structures (e.g. the skull base and carotid artery), 2. Filling the dead cavity after resection of a large tumor, 3. Restoration of maxillofacial function, 4. Repairing the patient’s appearance. However, due to previous treatment experience and the characteristics of recurrent tumors, patients also face many difficulties, including the following: 1. Lack of anastomotic vessels and disordered anatomical structure in the recipient area, 2. Fewer flaps to choose from, 3. A large amount of tissue is necessary, 4. A high success rate is essential.

Considering these problems, the latissimus dorsi flap and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap are the best choices. As common flaps, the tissue masses of these two flaps are larger than those of forearm flaps and anterolateral thigh flaps. At the same time, as nonfirst-line flaps, the latissimus dorsi flap and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap can still be used when other common flaps have already been used in the initial operation. Moreover, multi-island flaps can often be modified to repair complex defects. In this study, we demonstrated the reliability of both flaps as a salvage surgical application. More importantly, we found that the use of both can significantly improve the QOL after SS.

As demonstrated by the UW-QOL questionnaires, the scores of the functional domains declined after SS. We considered it’ s inevitable as the tumor involves many functional structures. Dysphagia occurs frequently after treatment for HNCs because of the gross destruction of organs vital for swallowing (e.g., tongue, larynx, mouth floor and pharyngeal wall) (34, 35). The same consequence was found in our study: swallowing decreased significantly with lower scores, in which 18 of 25 patients suffered partial or total dysphagia, and all of them had one or all of these structures involved. In addition, it was found that problems with the shoulder were significantly worsened. Among the patients with decreased scores, two underwent accessory nerve snipping. We hypothesized that the performance of neck dissection is one possible reason for the excision or destruction of the accessory nerve. Dry mouth is a significant manifestation of salivary gland dysfunction, confirmed as a side effect after radiotherapy (36), and reduced salivary production or sticky saliva is associated with a decline in QOL (37). In our study, significant worsening of sticky saliva and dry mouth were found after surgery. Since our postoperative scale was collected in a short time after operation, the patients lacked perfect functional recovery training. Therefore, long-time post-operative functional recovery training might improve the situation which needs attention during further follow-up.

Surprisingly, we found the composite domains improved after SS and attributed this positive trend to the relief of severe pain, which is one of the most common symptoms of head and neck cancers and has a noticeable impact on QOL. Studies on understanding the priorities of patients with HNCs showed the most concern for cure, survival and avoiding pain (38), which hinted at a strong link between relief of pain and improvement of QOL. In the premise of balance with function, SS can remove the invading tumor and relieve the compression of nerves, which significantly contributes to the relief of severe pain. In addition, the removal of extensively invaded tumors is crucial to enhance the patients’ confidence in treatment modalities and their life expectancy.

Several previous studies indicated that the high rates of complications after SS in HNCs ranged from 23% to 67%, and pharyngocutaneous fistula was the most common complication (13, 39). Complications after SS in our study, however, were rare, affecting only 4 patients, and manifested as maxillofacial edema, flap crisis, chronic pain, bone exposure and/or pharyngocutaneous fistula. We considered this inconsistent result to be related to the small sample size and recall bias, with some post-operative follow-up information being provided by family members of the patient, and grief after their death might have influenced their reminiscence.

We tentatively estimated survival time and found that patients who underwent SS achieved 1-year OS and DFS rates of 58.4% and 26.2%, respectively, and 2 year survival rates were 37.2% and 20%, which is lower than previous results. Elbers reported the OS and DFS at 2-year of were 55% and 53%, respectively (12), and Hamoir reported a 2-year OS of 59% among patients who underwent SS (39). Of note, different previous studies have different emphases, such as specific subsites, specific salvage modalities or specific primary treatments (40–42). Thus, directly comparing their results can be one-sided and potentially misleading. In our study, all patients underwent primary treatment but still had extensive recurrence. Meanwhile, 6 patients (24%) still had positive margins after SS. Some studies also have reported that invasion of vital structures, especially pterygoid plates and the skull base, poses great challenges to achieve adequate resection and leads to poor survival outcomes (43, 44). However, compared to the literature review of nonoperative treatment in R/M HNSCC, median OS of our study is apparently better.

Limitations do exist in this study. The limited sample size is worrisome but it is due to the rarity of patients. Because of the terrible physical condition of some patients who could not return to the hospital, some post-operative follow-up data were obtained via telephone, which undoubtedly increased the inaccuracy of the data. Likewise, the criterion for responses to the questions differed for each patient due to their subjective character. Nevertheless, this study has provided some important results and suggestions for the future selection of SS.

R/M HNC patients underwent SS can obtain survival benefit. The application of latissimus dorsi flap and pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap in SS for R/M HNC is feasible. It could significantly improve the patients’ quality of life after SS, especially by relieving severe pain. In the future, post-operative functional recovery training also needs attention during follow-up.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Beijing Stomatological Hospital ethics committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Contribution Author(s) Study concepts: LZ, QX. Study design: ZF, ZH, LZ, QX. Date acquisition: LZ, QX, HW, CL, BY, L Q. Quality control of data and algorithms: LZ, QX, BL, JL. Data analysis and interpretation: LZ, QX, ZF. Statistical analysis: LZ, QX, HL. Manuscript preparation: All of the authors. Manuscript editing: All of the authors. Manuscript review: All of the authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This article is supported by the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (CFH2020-2-2143); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072984); the Project of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (KM202110025008); innovation Research Team Project of Beijing Stomatological Hospital, Capital Medical University (NO. CXTD202204) and Beijing Stomatological Hospital, Capital Medical University Young Scientist Program (NO. YSP202111).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Zhang L, Liu H, Li B, Li J, Wang H, Yang B, et al. Quality of life after salvage surgery for extensively recurrent head and neck cancer patients: A prospective, observational, real-world study. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at research square. research square (2022). Available at: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1211340/v1

2. Ruud Kjaer EK, Jensen JS, Jakobsen KK, Lelkaitis G, Wessel I, von Buchwald C, et al. The impact of comorbidity on survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A nationwide case-control study spanning 35 years. Front Oncol (2020) 10:617184. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.617184

3. Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designé L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. Lancet (2000) 355:949–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90011-4

4. Forastiere A, Goepfert H, Maor M, Pajak TF, Cooper J. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med (2003) 349:2091–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317

5. Ho AS, Kraus DH, Ganly I, Lee NY, Shah JP, Morris LG. Decision making in the management of recurrent head and neck cancer. Head Neck (2014) 36:144–51. doi: 10.1002/hed.23227

6. Haque S, Karivedu V, Riaz MK, Choi D, Roof L, Hassan SZ, et al. High-risk pathological features at the time of salvage surgery predict poor survival after definitive therapy in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol (2019) 88:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.11.010

7. Sanabria A, Kowalski LP, Shaha AR, Silver CE, Werner JA, Mandapathil M, et al. Salvage surgery for head and neck cancer: a plea for better definitions. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2014) 271:1347–50. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-2924-7

8. Krol E, Brandt CT, Blakeslee-Carter J, Ahanchi SS, Dexter DJ, Karakla D, et al. Vascular interventions in head and neck cancer patients as a marker of poor survival. J Vasc Surg (2019) 69:181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.04.058

9. Brown JS, Shaw RJ. Reconstruction of the maxilla and midface: introducing a new classification. Lancet Oncol (2010) 11:1001–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70113-3

10. Ariyan S. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap: a versatile flap for reconstruction for reconstruction in the head and neck. Plast Reconstr Surg (1979) 63:73–81. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197901000-00012

11. Patil VM, Noronha V, Thiagarajan S, Joshi A, Chandrasekharan A, Talreja V, et al. Salvage surgery in head and neck cancer: Does it improve outcomes? Eur J Surg Oncol (2020) 46:1052–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.01.019

12. Elbers JBW, Veldhuis LI, Bhairosing PA, Smeele LE, Jozwiak K, van den Brekel MWM, et al. Salvage surgery for advanced stage head and neck squamous cell carcinoma following radiotherapy or chemoradiation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2019) 276:647–55. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05292-0

13. Hamoir M, Schmitz S, Suarez C, Strojan P, Hutcheson KA, Rodrigo JP, et al. The current role of salvage surgery in recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) (2018) 10:267. doi: 10.3390/cancers10080267

14. Tan HK, Giger R, Auperin A, Bourhis J, Janot F, Temam S. Salvage surgery after concomitant chemoradiation in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas - stratification for postsalvage survival. Head Neck (2010) 32:139–47. doi: 10.1002/hed.21159

15. Qin S-H, Li X-M, Li W-L. Systematic retrospective study of oral cancer-related quality of life scale. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi = Huaxi Kouqiang Yixue Zazhi = West China J Stomatol (2018) 36:410–20. doi: 10.7518/hxkq.2018.04.012

16. Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Graeff AD, Kaasa S. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol (1999) 17:1008–19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1008

17. Bjordal K, Graeff AD, Fayers PM, Hammerlid E, Pottelsberghe CV, Curran D, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. Eur J Cancer (2000) 36:1796–807. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00186-6

18. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai SA, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Haes JCD. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Ins (1993) 85:365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

19. Hassan SJ, Weymuller EA. Assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck (2010) 15:485–96. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150603

20. Boyapati RP, Shah KC, Flood V, Stassen LF. Quality of life outcome measures using UW-QOL questionnaire v4 in early oral cancer/squamous cell cancer resections of the tongue and floor of mouth with reconstruction solely using local methods. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg (2013) 51:502–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.09.013

22. Guo Y, Luo Y, Zhang Q, Huang X, Li Z, Shen L, et al. First-line treatment with chemotherapy plus cetuximab in Chinese patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Efficacy and safety results of the randomised, phase III CHANGE-2 trial. Eur J Cancer (2021) 156:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.039

23. Patil V, Noronha V, Dhumal SB, Joshi A, Menon N, Bhattacharjee A, et al. Low-cost oral metronomic chemotherapy versus intravenous cisplatin in patients with recurrent, metastatic, inoperable head and neck carcinoma: An open-label, parallel-group, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Global Health (2020) 8:e1213–e22. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30275-8

24. Ferris RL, Haddad R, Even C, Tahara M, Dvorkin M, Ciuleanu TE, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: EAGLE, a randomized, open-label phase III study. Ann Oncol (2020) 31:942–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.001

25. Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C, Dinis J, Licitra L, Ahn M-J, et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet (2019) 393:156–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8

26. Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, Soulières D, Tahara M, de Castro G, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet (2019) 394:1915–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7

27. Argiris A, Li S, Savvides P, Ohr JP, Gilbert J, Levine MA, et al. Phase III randomized trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol (2019) 37:3266–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00555

28. Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med (2016) 375:1856–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252

29. Machiels J-PH, Haddad RI, Fayette J, Licitra LF, Tahara M, Vermorken JB, et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-head & neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2015) 16:583–94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70124-5

30. Argiris A, Ghebremichael M, Gilbert J, Lee JW, Sachidanandam K, Kolesar JM, et al. Phase III randomized, placebo-controlled trial of docetaxel with or without gefitinib in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: an eastern cooperative oncology group trial. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31:1405–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4272

31. Vermorken JB, Stöhlmacher-Williams J, Davidenko I, Licitra L, Winquist E, Villanueva C, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil with or without panitumumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SPECTRUM): an open-label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol (2013) 14:697–710. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70181-5

32. Urba S, van Herpen CM, Sahoo TP, Shin DM, Licitra L, Mezei K, et al. Pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin monotherapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: final results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Cancer (2012) 118:4694–705. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27449

33. Nilsen ML, Johnson JT. Potential for low-value palliative care of patients with recurrent head and neck cancer. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18:e284–e9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30260-7

34. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Lopez-Tortosa J, Palazon Tovar T, Rodriguez-Gonzales MA. Assessing quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer in Spain by means of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35. J Craniomaxillofac Surg (2012) 40:614–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.01.011

35. Pezdirec M, Strojan P, Boltezar IH. Swallowing disorders after treatment for head and neck cancer. Radiol Oncol (2019) 53:225–30. doi: 10.2478/raon-2019-0028

36. Riley P, Glenny AM, Hua F, Worthington HV. Pharmacological interventions for preventing dry mouth and salivary gland dysfunction following radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2017) 7:CD012744. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012744

37. Winter C, Keimel R, Gugatschka M, Kolb D, Leitinger G, Roblegg E. Investigation of changes in saliva in radiotherapy-induced head neck cancer patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18:1629. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041629

38. Windon MJ, D’Souza G, Faraji F, Troy T, Koch WM, Gourin CG, et al. Priorities, concerns, and regret among patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer (2019) 125:1281–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31920

39. Hamoir M, Holvoet E, Ambroise J, Lengele B, Schmitz S. Salvage surgery in recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Oncologic outcome and predictors of disease free survival. Oral Oncol (2017) 67:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.01.008

40. Zafereo ME, Hanasono MM, Rosenthal DI, Sturgis EM, Lewin JS, Roberts DB, et al. The role of salvage surgery in patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Cancer (2009) 115:5723–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24595

41. Dequanter D, Vercruysse N, Shahla M, Paulus P, Lothaire P. Salvage surgery after failure of non surgical therapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Open J Stomatol (2011) 01:189–94. doi: 10.4236/ojst.2011.14029

42. Santoro L, Tagliabue M, Massaro MA, Ansarin M, Calabrese L, Giugliano G, et al. Algorithm to predict postoperative complications in oropharyngeal and oral cavity carcinoma. Head Neck (2015) 37:548–56. doi: 10.1002/hed.23637

43. Liao CT, Ng SH, Chang JT, Wang HM, Hsueh C, Lee LY, et al. T4b oral cavity cancer below the mandibular notch is resectable with a favorable outcome. Oral Oncol (2007) 43:570–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.06.008

Keywords: salvage surgery, massive soft tissue flap, recurrent/metastatic head and neck cancer, quality of life, overall survival (OS)

Citation: Zhang L, Xu Q, Liu H, Li B, Wang H, Liu C, Li J, Yang B, Qin L, Han Z and Feng Z (2022) The application of salvage surgery improves the quality of life and overall survival of extensively recurrent head and neck cancer after multiple operation plus radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 12:1017630. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1017630

Received: 12 August 2022; Accepted: 18 October 2022;

Published: 01 November 2022.

Edited by:

Arun Khattri, Indian Institute of Technology (BHU), IndiaReviewed by:

Ata Garajei, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, IranCopyright © 2022 Zhang, Xu, Liu, Li, Wang, Liu, Li, Yang, Qin, Han and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhien Feng, anlmemhlbkAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.