95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 05 January 2023

Sec. Breast Cancer

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.1017343

This article is part of the Research Topic Methods in Breast Cancer View all 17 articles

Puneeta Ajmera1

Puneeta Ajmera1 Mohammad Miraj2*

Mohammad Miraj2* Sheetal Kalra3

Sheetal Kalra3 Ramesh K. Goyal4

Ramesh K. Goyal4 Varsha Chorsiya3

Varsha Chorsiya3 Riyaz Ahamed Shaik5

Riyaz Ahamed Shaik5 Msaad Alzhrani2

Msaad Alzhrani2 Ahmad Alanazi2

Ahmad Alanazi2 Mazen Alqahtani6

Mazen Alqahtani6 Shaima Ali Miraj7

Shaima Ali Miraj7 Sonia Pawaria8

Sonia Pawaria8 Vini Mehta9

Vini Mehta9Introduction: The use of telehealth interventions has been evaluated in different perspectives in women and also supported with various clinical trials, but its overall efficacy is still ascertained. The objective of the present review is to identify, appraise and analyze randomized controlled trials on breast cancer survivors who have participated in technology-based intervention programs incorporating a wide range of physical and psychological outcome measures.

Material and methods: We conducted electronic search of the literature during last twenty years i.e., from 2001 till August 10, 2021 through four databases. Standardized mean difference with 95% confidence interval was used.

Results: A total of 56 records were included in the qualitative and 28 in quantitative analysis. Pooled results show that telehealth interventions were associated with improved quality of life (SMD 0.48, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.92, p=0.04), reduced depression (SMD -1.27, 95% CI =-2.43 to -0.10 p=0.03), low distress and less perceived stress (SMD -0.40, 95% CI =-0.68 to -0.12, p=0.005). However, no significant differences were observed on weight change (SMD -0.27, 95% CI =-2.39 to 1.86, p=0.81) and anxiety scores (SMD -0.09, 95% CI =-0.20 to 0.02, p=0.10) between the two groups. Improvement in health care competence and fitness among participants was also reported.

Conclusion: Study concludes that telehealth care is a quick, convenient and assuring approach to breast cancer care in women that can reduce treatment burden and subsequent disturbance to the lives of breast cancer survivors.

Breast cancer is the most common diagnosed cancer in women (1) and accounted for 2.1 million diagnosed cases and an estimated 626,679 deaths worldwide in 2018 (2). Due to advancements in diagnostic techniques and therapeutic treatment during the last few decades, 5-year survival rate of breast cancer patients has exceeded 85 percent (3). “Breast Cancer survivors” is a term commonly used for women living with cancer since the inception (diagnosis) of the disease and for the balance of life (4). Once a woman acquires breast cancer and even if she is treated, a continuous interdisciplinary supportive care is desired (5–7). Majority of the women experience various psychological problems like anxiety, depression and perceived stress which are generally substantial and prolonged (8–10) and require considerable healthcare support that may help them overcome psychological barriers and perceive their situation more positively (11). Every woman plays multifaceted roles in any normal scenario. For women, whether it is job or household responsibilities it is difficult for her to manage a separate time slot for visiting the consultant and get guidance in person (12). Such circumstances consequently brought in demand for alternative provision for health care service delivery, which prioritize the technology guided tele-intervention to come into role (13, 14). The technology acts as a boon in such cases where they can use telehealth consultation or regime and be a part of any fitness protocol during the micro breaks of their already scheduled activities (15, 16). Digital technology guided tele-intervention though are “complex” but have the potential for outreach, cost effectiveness and accessibility in managing the health related issues for consultation and treatment purposes using various application and online web services (13, 17–19). This trend is facilitated more with the inculcation of digital technology of mobile, application and dependency on artificial intelligence (20).

Researchers have investigated the effectiveness of variety of telehealth intervention for breast cancer survivors in a range of domains like quality of life, mental health, nutritional aspects etc (13, 14, 21–23). Tele-interventions targeting various spectrum of ages of women in multiple aspects across diverse racial and cultural perspectives have been shown to be satisfactory to the end-user and realistic to implement (24, 25). Although the use of telehealth interventions have been evaluated in different perspectives in women and also supported with various clinical trials, but its overall efficacy is still ascertain due to difficulty in designing or implementing non-biased randomized controlled trials (RCT) exploring its true effect. A generalized search in data bases indicates that most of the reviews performed on breast cancer survivors has targeted only Quality of life and psychological outcome measures (13). There is a dearth of published systematic reviews on the impact of telehealth guided interventions on outcomes other than Quality of life and psychological measures in breast cancer survivors and that has formed the basis of this review. To the best of author’s knowledge, this meta-analysis is first of its kind to access the effectiveness of spectrum of telehealth interventions on a variety of clinical and psychological outcomes in breast cancer survivors.

The objective of the present review is to identify, appraise and analyze qualitative and quantitative research evidence for breast cancer survivors who have participated in technology based tele-intervention programs incorporating a wide range of physical, physiological and psychological outcome measures. The intent of the present systematic review will help in providing important consideration for potential outcome of telehealth guided tele intervention with a future insight on its successful uptake.

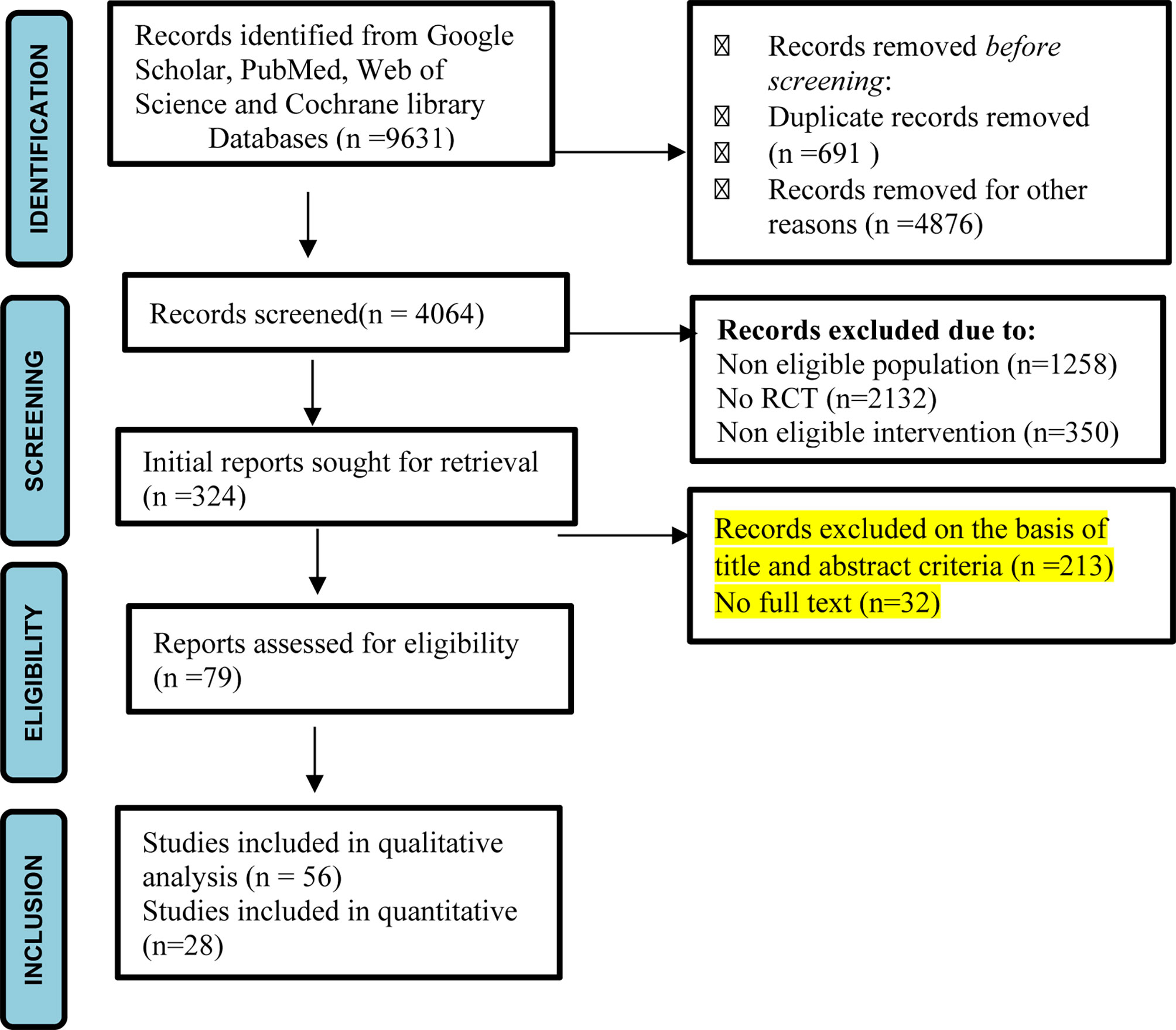

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA)statement was used for to develop and report this systematic review (26) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram of study (27).

We conducted electronic search of the literature during last twenty years i.e. from 2001 till August 10, 2021 through four databases viz. Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane library. To search more precisely, MeSH terms and Boolean operators were used in library databases. Search strategy used was: [Tele OR Tele health OR Tele technology OR Tele intervention OR Tele technologies OR Telemedicine OR Teleconsultation OR Telecommunication OR E health OR e Health OR Mobile Health OR mHealth OR Cell Phones OR Telephones OR Text Messaging OR SMS OR Videoconference OR Video-conference OR Videoconferencing OR Skype] AND [Breast cancer OR Breast neoplasm OR Breast cancer survivor OR Breast cancer survivor OR Breast neoplasm survivor OR Breast neoplasm survivors] AND [Woman OR Women OR Woman health OR Women health OR Health of Woman OR Health of Women].” To maximize literature coverage and cross check the results we followed multivaried methodology covering multiple databases. We used PICOS framework to select articles from the databases. P (Population) breast cancer patients. Telehealth intervention is compared to usual medical care alone in I (intervention) and C (comparison) respectively. Usual care referred to standard medical procedures such routine hospital visits for in-person treatment, conventional breast cancer education, and so on. O (Outcomes: Weight change, Quality of life and psychological outcomes, such as distress and perceived stress, anxiety, and depression. S (study design) only RCTs were included. Case reports, reviews, non-randomized controlled trials, duplicate reports, and studies with uninteresting data were excluded from consideration. PICOS framework is presented in Table 1.

The process of eligibility was divided into subsequent phases with definite inclusion or exclusion criteria. Only full text academic articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included in the review whereas magazine and newspaper articles were excluded. Using the search strings, 324 papers from the four databases were identified in the phase, I. In phase II, duplicate papers in each search string and papers for which only abstracts were available were excluded. In the IIIrd phase, a new search category with papers impending under all established search strings was introduced and duplicates were removed across all search strings.

In phase IV, all full-length texts were thororghly assessed and papers that had no relevance to objectives and research questions of our study were excluded. Twenty Eight papers were finally selected and a descriptive analysis was executed to summarize the results.

* Randomized Controlled Trials that examined the role of telehealth technologies in breast cancer survivors were included. Non randomized controlled trials, cross sectional studies, cohort and case control studies were excluded from the study.

* Full text articles written only in English language and published in peer-reviewed journals were included while articles in any other language, book chapters were excluded.

Data was independently extracted by two reviewers, (SK) and (PA)on characteristics of study location, year of study, participants, study duration, sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, details of intervention, study duration, outcome measures and results of study. Wherever possible, post intervention mean scores and standard deviation were retrieved and recorded. Data was rechecked by third reviewer, (SP) and any discrepancy or doubt pertaining to the selection of particular study was resolved after exhaustive discussion among all the authors.

Risk of bias in individual studies and methodological quality assessment was performed by 2 independent reviewers SK and PA with more than 15 years of experience in empirical research. Cochrane collaboration tool was used to assess bias risk in randomized control trials in selected articles (28). The tool assesses bias risk on basis of 7 domains. The judgment regarding bias was categorized under 3 categories- a. Low risk b. High risk and c. unclear risk. PRISMA guidelines were used for reporting results of systematic reviews and Meta-analysis. Any disagreements between the 2 reviewers regarding appraisal recommendation were resolved by another reviewer (MM). Review Manager (RevMan) software version 5.4 is used for meta-analysis.

Initially, during literature search, 9631 records were identified from selected databases. During first screening 691 articles were removed due to duplication while 1258 records were removed as population was found to be non-eligible. Further 2132 records were non-RCTs and in 350 records intervention was not as per our eligibility, hence they were also removed. After initial screening, 324 titles emerged out to be relevant studies. After removal of duplicates and studies not fulfilling eligibility criteria, seventy nine full text records were identified and screened again. Fifty-six records were found to be relevant and directly within the scope of this review and therefore included in the qualitative analysis. Twenty three studies were included in quantitative analysis. Data was summarized narratively and descriptive analysis was carried out. Tables and graphs were prepared to convey significant features of the literature.

Fifty-six RCT’s met our inclusion criteria involving a total of 20,746 women. The earliest study meeting eligibility criteria was published in year 2001 (29). Thirty two trials were conducted in USA (22, 29–58), 7 in Australia (59–64), 4 in Netherland (65–68), 3 each in Denmark (14, 69, 70) and Spain (71–73), 2 in Germany (74, 75) and 1each in Turkey (76), Finland (77), Taiwan (42), Canada (78), UK (39) and Korea (79). Sample size ranged from 53 in the study of Owen et al, 2005 (76) to 3088 in the study of Pierce et al. in 2007 (30). The trials were conducted in different set ups ranging from cancer societies, multi center institutes, hospitals, medical centers, oncology clinics and Medical University. Age of Participants recruited in different studies ranged from minimum of 18 years to maximum of 80 years. Longest follow up of 4 years for events and mortality related to cancer was done by Pierce et al, 2007 (30). Characteristics of studies are shown in Tables 2, 3. The types of technology used for telehealth interventions varied throughout the studies that were included. Twenty nine studies used telephone based interventions (22, 29–32, 34–36, 38–40, 42, 44–47, 49, 51, 52, 58–62, 66, 69, 75, 78, 80). Twelve studies used web based interventions (33, 47, 50, 53, 57, 63, 65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 77). Telemedicine was used in two studies (70, 73), eight studies utilized combination of Internet, web, telephone and videoconferencing (14, 37, 41, 43, 48, 56, 67, 71) where as in three studies wearable technology was used for weight management or physical activity tracking (33, 54, 64). Two studies used mobile health based app for self-management of symptoms and mobile gaming in cancer patients (42, 56).

Varied outcome measures were evaluated in the trials. Studies targeting weight management in cancer survivors evaluated weight status, calorie intake and Body Composition. Studies that assessed psycho behavioral aspects used different outcomes like depression, anxiety, sleep and sexual dysfunctions, spiritual and emotional wellbeing, psychological morbidity, self-reported functional status, adjustment to life and adherence to treatment. Studies that examined effects of exercise interventions evaluated Physical activity status, quality of life, self-related health outcomes and functional status. Recurrence of cancer and death was also evaluated in 1 study by Pierce et al, 2007 (30). Interventions and outcome measures are presented in Table 3.

Four trials were judged with high risk of bias in the domain of random sequence generation (33, 38, 47, 74), as methods of randomization were not given in detail. Twenty trials were judged with low risk of bias in the domain of allocation concealment (29–32, 38, 39, 42, 44, 51, 54, 60, 63–65, 67, 69, 71–73, 80). Eleven studies reported blinding of participants and personnel (14, 29, 32, 38, 42, 51, 63, 64, 72, 75, 80) while twelve trials mentioned about blinding of outcome assessors (38, 39, 42, 51, 60, 64, 67, 69–72, 80) and hence were regarded at low risk of bias. Six studies were reported at high risk in the domain of incomplete outcome data (35, 39, 56, 61, 62, 73). Therefore, in future researches, the allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors should be emphasized to bring out better and reliable conclusions. Risk of bias is presented in Table 4.

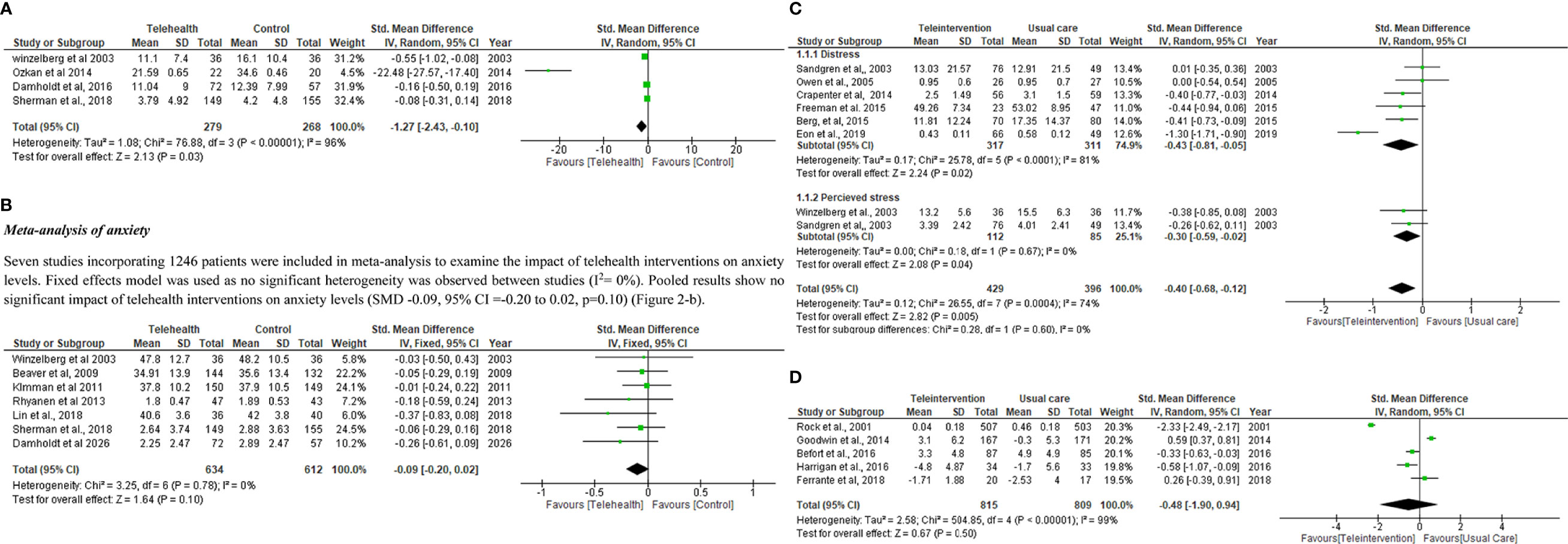

Four trials with 547 participants reported the outcomes of depression in meta-analysis. Random-effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity across these trials (I2 = 96%, Tau2 = 1.08). Pooled results indicated that telehealth intervention were associated with reduced depression levels in breast cancer patients (SMD -1.27, 95% CI =-2.43 to -0.10 p=0.03) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2 (A) Meta-analysis of depression. (B)Meta-analysis of anxiety.(C) Meta-analysis of (A) Distress (B) perceived stress. (D) Meta-analysis of weight change. (E) Meta-analysis of Quality of life.

Seven studies incorporating 1246 patients were included in meta-analysis to examine the impact of telehealth interventions on anxiety levels. Fixed effects model was used as no significant heterogeneity was observed between studies (I2 = 0%). Pooled results show no significant impact of telehealth interventions on anxiety levels (SMD -0.09, 95% CI =-0.20 to 0.02, p=0.10) (Figure 2B).

Six studies involving 628 patients were included in meta-analysis to determine the impact of telehealth interventions on distress. Random effects model was used as high heterogeneity was observed among studies (I2 = 81%). Pooled results depict that a significant impact of telehealth interventions was observed on distress (SMD -0.27, 95% CI =-0.44 to -0.09, p=0.003) (Figure 2C).

Subgroup analysis including 825 patients was carried out to determine the impact of telehealth interventions on perceived stress and distress levels. Random effects model was used as high heterogeneity was observed among studies (I2 = 74%). Six studies involving 628 patients were included to determine the impact of telehealth interventions on distress while two studies including 197 patients were included to determine the impact of telehealth interventions on perceived stress. Pooled results depict that a significant impact of telehealth interventions was observed on distress and perceived stress levels (SMD -0.40, 95% CI =-0.68 to -0.12, p=0.005) (Figure 2C).

Five studies incorporating 1624 subjects were incorporated in the meta-analysis of weight change. Random effects model was used due to more heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 99%). Pooled results depict that no significant impact of telehealth interventions was observed on weight change levels also (SMD -0.48, 95% CI =-1.90 to 0.94, p=0.50) (Figure 2D).

Seventeen RCTs including 3055 breast cancer patients were included in the meta-analysis of QOL. Different QOL measurement scales reported in these trials are: FACT G, EORTC QLQ-C30, SF36, FACT-B, FACT-B+4, BCPT and Impact of Cancer Scale. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was used because of variety of measurement scales used in trials. Pooled results depict that telehealth interventions significantly improved the QOL score in breast cancer patients (SMD 0.48, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.92, p=0.04) (Figure 2E).

In recent decades, medical technology has experienced significant development (82). In addition, breast cancer patients nowadays tend to have better survival rates compared with those in the past. However, during the survival period, these patients’ QOL, physical and psychological health need close attention. Psychological symptoms such as sadness, anxiety and perceived stress are common and generally untreated in breast cancer patients, which can have a detrimental impact on their quality of life. Also, physical health issues like weight gain and obesity can result into recurrent risk, poor prognosis and all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors (30, 83). Lifestyle interventions in form of weight reduction has been recommended to improve health outcomes (84). In comparison to traditional care, telehealth is a highly accessible and effective intervention that may overcome time and location obstacles. Patients can connect with medical professionals about their disease issues and gain more information about disease management through telehealth care. These situations can give patients with continual access to assistance and make them feel that they’re not alone and that medical help is always nearby both of which are advantageous to their psychological well-being. The use of telehealth has numerous advantages for breast cancer patients, but there are also many challenges and issues among patients, healthcare professionals, and service providers. These include patient’s unwillingness to use the technology, especially older patients who prefer in-person consultations, inconsistent internet connections in rural regions, patient mistrust because a thorough physical examination cannot be performed remotely, and inadequate insurance coverage. Additional challenges to telehealth include concerns regarding the security of patient health records transmitted electronically, high acquisition and implementation costs, significant maintenance costs, management and training of healthcare professionals to effectively use the various platforms and limited access to technology or low platform literacy. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first meta-analysis to examine the effect of telehealth intervention from inception till date on various physical and psychological health parameters in breast cancer patients. The results revealed that compared with usual care, telehealth intervention was associated with higher QOL, with less depression, distress and perceived stress symptoms however no significant effect was seen on anxiety and weight status. Fifty Six RCTs incorporating telehealth modalities for breast cancer women were included in this review. Telephone was found to be the leading telehealth tool in most of the studies. A large number of studies also supported use of web based interventions for various physical and psychological outcomes in cancer survivors. There has been an increasing interest in the use of smart wearable technologies to encourage breast cancer survivors to modify their physical activity (PA) habits. Alternate telehealth technologies like mobile-based apps or other advanced e-Health systems have also seen an upsurge in last few years. A precise, reproducible, trustworthy, and affordable diagnosis of breast cancer lymphedema can be made using augmented reality techniques, such 3DLS, in the clinical setup (84). However more number of RCT’s are needed to evaluate their efficacy on weight status, QOL and mental health parameters. Majority of telehealth interventions were related to awareness using educational/supportive material based on scheduled phone calls aimed at improving physical and psychological health of study populations. To enhance the quality of this systematic review, only randomized controlled trials were included and quality was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Timely information and consultation with experts is a crucial aspect for women suffering from breast cancer. Technological advancements have improved the survival rates of these patients. But, during the survival period, their health parameters need to be vigilantly monitored. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that show that breast cancer patients need continuous consultation that would help them in understanding their condition better so that they can cope with the treatment process more confidently (83, 85, 86). The results of this systematic review indicate that telehealth technologies could considerably improve quality of life, physiological and psychological parameters of breast cancer patients.

The increasing enthusiasm for tele health is determined not only by its established benefits, but also by the extensive accessibility of mobile phones, and the comparatively low levels of education required to use them (1).In comparison to traditional care, telehealth is a highly accessible and effective intervention that may overcome time and location obstacles (65). Patients can conveniently interact with health professionals about their medical conditions and get more information about disease management through telehealth care (87). Results of our review also show majority of trials used telephone based interventions. The dominance of telephone based and Web-based telehealth interventions makes participant recruitment easy and facilitates timely data collection. Also the risk of missing information is reduced and follow up becomes easy. Furthermore, eHealth interventions are relatively more cost effective and provide wide geographical coverage overcoming mobility issues. But researchers have less control over respondents (77, 88). The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly transformed how healthcare is provided. In order to sustain patient care while reducing the danger of nosocomial SARS-COV-2 infection, decentralization measures such telehealth visits, home-based care, and remote patient monitoring should be quickly adopted. These techniques can be used to relieve the burden of treatment and lower the risk of exposure for patients and medical staff across the entire spectrum of care, from prevention to palliation (89–92). Moreover, our findings also divulge that telehealth interventions are primarily used in developed nations while their use in developing countries is still less. This may be due to inappropriate resource allocation, dearth of technical expertise, high initial investment and deficient healthcare infrastructure in developing countries.

The large scale search conducted in multiple databases, inclusion of exclusive randomized controlled trials, methodological quality assessment are the strengths of this review. Studies that had only telehealth interventions were included thus making comparison of studies feasible. Another strength is inclusion of wide range of physical, physiological and psychological outcome measures. There are some limitation also. Differences between duration of interventions, outcomes measures and varied control groups in trials led to heterogeneity. Also, inclusion of trials written in English language only was another limitation that may introduce publication bias.

This systematic review concludes that telehealth care is a quick, convenient and assuring approach to breast cancer care in women that can reduce treatment burden and subsequent disturbance to the lives of breast cancer survivors. Telehealth interventions are worthy of clinical consideration and should be used as part of a holistic breast cancer treatment plans. We suggest that additional resources should be placed in the development of telehealth care and more high-quality randomized controlled trials should be conducted to investigate the worth of telehealth care in the management of breast cancer patients. It is also important to tailor and develop telehealth interventions according to survivor’s needs, possibly by involving them in the early stages of intervention design to curtail perception of impersonal care and attain benefits of remote monitoring.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization: Done by PA, SK, RG. Designing the study: RG, VC, RS. Data collection: PA, MA, AA, MAI, SM, SP. Compilation, analysis and interpretation of data: PA, RA, VM, MM. Manuscript writing and review: MM, PA, SK, VM. All the drafts were reviewed by PA, MM, SK, RG, VC, RS, MA, AA, MAI, SM. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research, Majmaah University, for funding through Deanship of Scientific Research vide Project No. RGP-2019-35. The authors are also thankful to AlMareefa and Saudi Electronic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for providing support to do this research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin (2015) 65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262

2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2018) 68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

3. Henson KE, Elliss-Brookes L, Coupland VH, Payne E, Vernon S, Rous B, et al. Data resource profile: National cancer registration dataset in England. Int J Epidemiol (2020) 49(1):16–h. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz076

4. Reich RR, Lengacher CA, Alinat CB, Kip KE, Paterson C, Ramesar S, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer patients: immediate and sustained effects across multiple symptom clusters. J Pain Symptom Manage (2017) 53(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.005

5. Akram M, Iqbal M, Daniyal M, Khan AU. Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biol Res (2017) 50(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s40659-017-0140-9

6. Park BW, Hwang SY. Unmet needs of breast cancer patients relative to survival duration. Yonsei Med J (2012) 53(1):118–25. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.1.118

7. Sanchez L, Fernandez N, Calle AP, Ladera V, Casado I, Sahagun AM. Long-term treatment for emotional distress in women with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2019) 42:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.09.002

8. Khan F, Amatya B, Pallant JF, Rajapaksa I. Factors associated with long-term functional outcomes and psychological sequelae in women after breast cancer. Breast. (2012) 21(3):314–20. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.01.013

9. Amatya B, Khan F, Galea MP. Optimizing post-acute care in breast cancer survivors: A rehabilitation perspective. J Multidiscip healthcare. (2017) 10:347. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S117362

10. Kalra S, Yadav J, Ajmera P, Sindhu B, Pal S. Impact of physical activity on physical and mental health of postmenopausal women: A systematic review. J Clin Diagn Res (2022) 16(2):YE01–YE08. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2022/52302.15974

11. Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Stengle W, Ballard D, Hawkins R, Shaw BR, et al. Use and impact of eHealth system by low-income women with breast cancer. J Health communicat (2005) 10(S1):195–218. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263257

12. Abrahams HJ, Gielissen MF, Donders RR, Goedendorp MM, van der Wouw AJ, Verhagen CA, et al. The efficacy of Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for severely fatigued survivors of breast cancer compared with care as usual: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer (2017) 123(19):3825–34. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30815

13. Chen Y-Y, Guan B-S, Li Z-K, Li X-Y. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients’ quality of life and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. (2018) 24(3):157–67. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16686777

14. Damholdt M, Mehlsen M, O’Toole M, Andreasen R, Pedersen A, Zachariae R. Web-based cognitive training for breast cancer survivors with cognitive complaints–a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology (2016) 25(11):1293–300. doi: 10.1002/pon.4058

15. Ashing K, Rosales M. A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology (2014) 23(5):507–15. doi: 10.1002/pon.3441

16. Badger TA, Segrin C, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM. Telephone-delivered health education and interpersonal counseling improve quality of life for latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Psycho-Oncology (2013) 22(5):1035–42. doi: 10.1002/pon.3101

17. Senanayake B, Wickramasinghe SI, Eriksson L, Smith AC, Edirippulige S. Telemedicine in the correctional setting: a scoping review. J Telemed Telecare. (2018) 24(10):669–75. doi: 10.1177/1357633X18800858

18. Cox A, Lucas G, Marcu A, Piano M, Grosvenor W, Mold F, et al. Cancer survivors’ experience with telehealth: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Med Internet Res (2017) 19(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6575

19. Hancock S, Preston N, Jones H, Gadoud A. Telehealth in palliative care is being described but not evaluated: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care (2019) 18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0495-5

20. Ghosh A, Chakraborty D, Law A. Artificial intelligence in Internet of things. CAAI Trans Intell Technol (2018) 3(4):208–18. doi: 10.1049/trit.2018.1008

21. Ashing KT, Miller AM. Assessing the utility of a telephonically delivered psychoeducational intervention to improve health-related quality of life in African American breast cancer survivors: a pilot trial. Psychooncology (2016) 25(2):236–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.3823

22. Meneses K, Gisiger-Camata S, Benz R, Raju D, Bail JR, Benitez TJ, et al. Telehealth intervention for latina breast cancer survivors: A pilot. Womens Health (2018) 14:1745506518778721. doi: 10.1177/1745506518778721

23. Hung Y, Bauer J, Horsely P, Coll J, Bashford J, Isenring E. Telephone-delivered nutrition and exercise counselling after auto-SCT: a pilot, randomised controlled trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2014) 49(6):786–92. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.52

24. Hatcher JB, Oladeru O, Chang B, Malhotra S, Mcleod M, Shulman A, et al. Impact of high-Dose-Rate brachytherapy training via telehealth in low-and middle-income countries. JCO Global Oncol (2020) 6:1803–12. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00302

25. Lopez AM. Telemedicine, telehealth, and e-health technologies in cancer prevention. Fundament Cancer Prevent: Springer; (2019), 333–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-15935-1_10

26. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-p) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ (2016) 350:354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647

27. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

28. Sterne J, Savović J, Page M, Elbers R, Blencowe N, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

29. Rock CL, Thomson C, Caan BJ, Flatt SW, Newman V, Ritenbaugh C, et al. Reduction in fat intake is not associated with weight loss in most women after breast cancer diagnosis: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer (2001) 91(1):25–34. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<25::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-G

30. Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the women’s healthy eating and living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA (2007) 298(3):289–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289

31. Samarel N, Tulman L, Fawcett J. Effects of two types of social support and education on adaptation to early-stage breast cancer. Res Nurs Health (2002) 25(6):459–70. doi: 10.1002/nur.10061

32. Pierce JP NV, Flatt SW, et al. Telephone counseling intervention increases intakes of micronutrient-and phytochemical-rich vegetables, fruit and fiber in breast cancer survivors. J Nutr (2004) 134(2):452–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.452

33. Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Alpers GW, Roberts H, Koopman C, Adams RE, et al. Evaluation of an internet support group for women with primary breast cancer. Cancer: Interdiscip Int J Am Cancer Society. (2003) 97(5):1164–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11174

34. Mishel MH, Germino BB, Gil KM, Belyea M, LaNey IC, Stewart J, et al. Benefits from an uncertainty management intervention for African–American and Caucasian older long-term breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol: J Psychol Soc Behav Dimensions Canc (2005) 14(11):962–78. doi: 10.1002/pon.909

35. Gotay CC, Moinpour CM, Unger JM, Jiang CS, Coleman D, Martino S, et al. Impact of a peer-delivered telephone intervention for women experiencing a breast cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25(15):2093–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4674

36. Sandgren AK, McCaul KD. Long-term telephone therapy outcomes for breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol: J Psychol Soc Behav Dimensions Canc (2007) 16(1):38–47. doi: 10.1002/pon.1038

37. Budin WC, Hoskins CN, Haber J, Sherman DW, Maislin G, Cater JR, et al. Breast cancer: education, counseling, and adjustment among patients and partners: a randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res (2008) 57(3):199–213. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319496.67369.37

38. Ell K, Vourlekis B, Xie B, Nedjat-Haiem FR, Lee PJ, Muderspach L, et al. Cancer treatment adherence among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer: a randomized controlled trial of patient navigation. Cancer: Interdiscip Int J Am Cancer Society. (2009) 115(19):4606–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24500

39. Beaver K, Tysver-Robinson D, Campbell M, Twomey M, Williamson S, Hindley A, et al. Comparing hospital and telephone follow-up after treatment for breast cancer: randomised equivalence trial. BMJ (2009) 338:a3147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3147

40. Marcus AC, Garrett KM, Cella D, Wenzel L, Brady MJ, Fairclough D, et al. Can telephone counseling post-treatment improve psychosocial outcomes among early stage breast cancer survivors? Psycho-oncology (2010) 19(9):923–32. doi: 10.1002/pon.1653

41. Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Shaw B, Serlin RC, Swoboda C, Han J-Y, et al. Mediating processes of two communication interventions for breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. (2010) 81:S48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.021

42. Baker TB, Hawkins R, Pingree S, Roberts LJ, McDowell HE, Shaw BR, et al. Optimizing eHealth breast cancer interventions: which types of eHealth services are effective? Transl Behav Med (2011) 1(1):134–45. doi: 10.1007/s13142-010-0004-0

43. Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Baker TB, Roberts LJ, Shaw BR, McDowell H, et al. Integrating eHealth with human services for breast cancer patients. Transl Behav Med (2011) 1(1):146–54. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0027-1

44. Sherman DW, Haber J, Hoskins CN, Budin WC, Maislin G, Shukla S, et al. The effects of psychoeducation and telephone counseling on the adjustment of women with early-stage breast cancer. Appl Nurs Res (2012) 25(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.10.003

45. Crane-Okada R, Freeman E, Kiger H, Ross M, Elashoff D, Deacon L, et al. Senior peer counseling by telephone for psychosocial support after breast cancer surgery: effects at six months. Oncol Nurs Forum (2012) 39(1):78–89. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.78-89

46. Pinto BM, Papandonatos GD, Goldstein MG. A randomized trial to promote physical activity among breast cancer patients. Health Psychol (2013) 32(6):616. doi: 10.1037/a0029886

47. Carpenter KM, Stoner SA, Schmitz K, McGregor BA, Doorenbos AZ. An online stress management workbook for breast cancer. J Behav Med (2014) 37(3):458–68. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9481-6

48. Freeman LW, White R, Ratcliff CG, Sutton S, Stewart M, Palmer JL, et al. A randomized trial comparing live and telemedicine deliveries of an imagery-based behavioral intervention for breast cancer survivors: reducing symptoms and barriers to care. Psycho-oncology (2015) 24(8):910–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.3656

49. Befort CA, Klemp JR, Sullivan DK, Shireman T, Diaz FJ, Schmitz K, et al. Weight loss maintenance strategies among rural breast cancer survivors: the rural women connecting for better health trial. Obesity (2016) 24(10):2070–7. doi: 10.1002/oby.21625

50. Chee W, Lee Y, Im E-O, Chee E, Tsai H-M, Nishigaki M, et al. A culturally tailored Internet cancer support group for Asian American breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot intervention study. J Telemed Telecare. (2017) 23(6):618–26. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16658369

51. Harrigan M, Cartmel B, Loftfield E, Sanft T, Chagpar AB, Zhou Y, et al. Randomized trial comparing telephone versus in-person weight loss counseling on body composition and circulating biomarkers in women treated for breast cancer: the lifestyle, exercise, and nutrition (LEAN) study. J Clin Oncol (2016) 34(7):669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6375

52. Han H-R, Song Y, Kim M, Hedlin HK, Kim K, Ben Lee H, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening literacy among Korean American women: A community health worker–led intervention. Am J Public Health (2017) 107(1):159–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303522

53. Cox M, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, Blalock J, Li Y, Murray J, et al. Comparison of internet and telephone interventions for weight loss among cancer survivors: randomized controlled trial and feasibility study. JMIR cancer. (2017) 3(2):e7166. doi: 10.2196/cancer.7166

54. Ferrante JM, Devine KA, Bator A, Rodgers A, Ohman-Strickland PA, Bandera EV, et al. Feasibility and potential efficacy of commercial mHealth/eHealth tools for weight loss in African American breast cancer survivors: pilot randomized controlled trial. Transl Behav Med (2020) 10(4):938–48. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby124

55. Hartman SJ, Nelson SH, Weiner LS. Patterns of fitbit use and activity levels throughout a physical activity intervention: exploratory analysis from a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. (2018) 6(2):e8503. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8503

56. Im EO, Kim S, Yang YL, Chee W. The efficacy of a technology-based information and coaching/support program on pain and symptoms in Asian American survivors of breast cancer. Cancer (2020) 126(3):670–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32579

57. Paladino AJ, Anderson JN, Krukowski RA, Waters T, Kocak M, Graff C, et al. THRIVE study protocol: a randomized controlled trial evaluating a web-based app and tailored messages to improve adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4588-x

58. Meneses K, Pisu M, Azuero A, Benz R, Su X, McNees P. A telephone-based education and support intervention for rural breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial comparing two implementation strategies in rural Florida. J Cancer survivorship: Res practice (2020) 14(4):494–503. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00866-y

59. Aranda S, Schofield P, Weih L, Milne D, Yates P, Faulkner R. Meeting the support and information needs of women with advanced breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Canc (2006) 95(6):667–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603320

60. Hayes S, Rye S, Battistutta D, Yates P, Pyke C, Bashford J, et al. Design and implementation of the exercise for health trial–a pragmatic exercise intervention for women with breast cancer. Contemp Clin Trials. (2011) 32(4):577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.03.015

61. Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Winkler EA, Hayes SC. A randomized trial of a telephone-delivered exercise intervention for non-urban dwelling women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: exercise for health. Ann Behav Med (2012) 43(2):229–38. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9324-7

62. Gordon LG, DiSipio T, Battistutta D, Yates P, Bashford J, Pyke C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a pragmatic exercise intervention for women with breast cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology (2017) 26(5):649–55. doi: 10.1002/pon.4201

63. Sherman KA, Przezdziecki A, Alcorso J, Kilby CJ, Elder E, Boyages J, et al. Reducing body image–related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: Results from the my changed body randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(19):1930–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3318

64. Lynch BM, Nguyen NH, Moore MM, Reeves MM, Rosenberg DE, Boyle T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a wearable technology-based intervention for increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors: The ACTIVATE trial. Cancer (2019) 125(16):2846–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32143

65. van den Berg SW, Gielissen MF, Custers JA, van der Graaf WT, Ottevanger PB, Prins JB. BREATH: web-based self-management for psychological adjustment after primary breast cancer–results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol (2015) 33(25):2763–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.9386

66. Kimman M, Dirksen C, Voogd A, Falger P, Gijsen B, Thuring M, et al. Nurse-led telephone follow-up and an educational group programme after breast cancer treatment: results of a 2× 2 randomised controlled trial. Eur J Canc (2011) 47(7):1027–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.003

67. Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Lombard C, Mathews S, Campbell J, Meel B. Impact of telephonic psycho-social support on adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after rape. AIDS Care (2010) 22(10):1173–81. doi: 10.1080/09540121003692185

68. Bruggeman-Everts FZ, Wolvers MD, Van de Schoot R, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, van der Lee ML. Effectiveness of two web-based interventions for chronic cancer-related fatigue compared to an active control condition: results of the “Fitter na kanker” randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res (2017) 19(10):e336. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7180

69. Høyer BB, Toft GV, Debess J, Ramlau-Hansen CH. A nurse-led telephone session and quality of life after radiotherapy among women with breast cancer: A randomized trial. Open Nurs J (2011) 5:31. doi: 10.2174/1874434601105010031

70. Zachariae R, Amidi A, Damholdt MF, Clausen CD, Dahlgaard J, Lord H, et al. Internet-Delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Institute. (2018) 110(8):880–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx293

71. Galiano-Castillo N, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C, Ariza-García A, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Del-Moral-Ávila R, et al. Telehealth system: A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of an internet-based exercise intervention on quality of life, pain, muscle strength, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer (2016) 122(20):3166–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30172

72. Ariza-Garcia A, Lozano-Lozano M, Galiano-Castillo N, Postigo-Martin P, Arroyo-Morales M. Cantarero-villanueva i. a web-based exercise system (e-cuidatechemo) to counter the side effects of chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res (2019) 21(7):e14418. doi: 10.2196/14418

73. Lleras de Frutos M, Medina JC, Vives J, Casellas-Grau A, Marzo JL, Borràs JM, et al. Video conference vs face-to-face group psychotherapy for distressed cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology (2020) 29(12):1995–2003. doi: 10.1002/pon.5457

74. David N, Schlenker P, Prudlo U, Larbig W. Online counseling via e-mail for breast cancer patients on the German internet: preliminary results of a psychoeducational intervention. GMS Psycho-Social-Med (2011) 8. doi: 10.3205/psm000074

75. Ziller V, Kyvernitakis I, Knöll D, Storch A, Hars O, Hadji P. Influence of a patient information program on adherence and persistence with an aromatase inhibitor in breast cancer treatment-the COMPAS study. BMC Canc (2013) 13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-407

76. Owen JE, Klapow JC, Roth DL, Shuster JL, Bellis J, Meredith R, et al. Randomized pilot of a self-guided internet coping group for women with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Behav Med (2005) 30(1):54–64. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_7

77. Ryhänen AM, Rankinen S, Siekkinen M, Saarinen M, Korvenranta H, Leino-Kilpi H. The impact of an empowering Internet-based breast cancer patient pathway program on breast cancer patients’ clinical outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs (2013) 22(7-8):1016–25. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12007

78. Goodwin PJ, Segal RJ, Vallis M, Ligibel JA, Pond GR, Robidoux A, et al. Randomized trial of a telephone-based weight loss intervention in postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving letrozole: the LISA trial. J Clin Oncol (2014) 32(21):2231–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.1517

79. Kim HJ, Kim SM, Shin H, Jang J-S, Kim YI, Han DH. A mobile game for patients with breast cancer for chemotherapy self-management and quality-of-life improvement: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res (2018) 20(10):e273. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9559

80. Hayes SC, Rye S, DiSipio T, Yates P, Bashford J, Pyke C, et al. Exercise for health: a randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a pragmatic, translational exercise intervention on the quality of life, function and treatment-related side effects following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2013) 137(1):175–86. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2331-y

81. Hou I-C, Lin H-Y, Shen S-H, Chang K-J, Tai H-C, Tsai A-J, et al. Quality of life of women after a first diagnosis of breast cancer using a self-management support mHealth app in Taiwan: randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. (2020) 8(3):e17084. doi: 10.2196/17084

82. Lippi L, D’Abrosca F, Folli A, Dal Molin A, Moalli S, Maconi A, et al. Closing the gap between inpatient and outpatient settings: Integrating pulmonary rehabilitation and technological advances in the comprehensive management of frail patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022) 19(15):9150. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159150

83. Invernizzi M, Runza L, De Sire A, Lippi L, Blundo C, Gambini D, et al. Integrating augmented reality tools in breast cancer related lymphedema prognostication and diagnosis. JoVE (Journal Visualized Experiments). (2020) 156):e60093. doi: 10.3791/60093

84. Kalra S, Miraj M, Ajmera P, Shaik RA, Seyam MK, Shawky GM, et al. Effects of yogic interventions on patients diagnosed with cardiac diseases. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med (2022) 9. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.942740

85. Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago EA, Khatcheressian J, Matsuyama R, Lyckholm LJ. A pilot trial of decision aids to give truthful prognostic and treatment information to chemotherapy patients with advanced cancer. J supportive Oncol (2011) 9(2):79. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.005

86. Vogel RI, Petzel SV, Cragg J, McClellan M, Chan D, Dickson E, et al. Development and pilot of an advance care planning website for women with ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol (2013) 131(2):430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.08.017

87. Leon N, Schneider H, Daviaud E. Applying a framework for assessing the health system challenges to scaling up mHealth in south Africa. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2012) 12(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-123

88. Loubani K, Kizony R, Milman U, Schreuer N. Hybrid tele and in-clinic occupation based intervention to improve women’s daily participation after breast cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18(11):5966. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115966

89. Eysenbach G, Group C-E. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res (2011) 13(4):e1923. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923

90. Palmqvist B, Carlbring P, Andersson G. Internet-Delivered treatments with or without therapist input: does the therapist factor have implications for efficacy and cost? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res (2007) 7(3):291–7. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.3.291

91. Binder AF, Handley NR, Wilde L, Palmisiano N, Lopez AM. Treating hematologic malignancies during a pandemic: utilizing telehealth and digital technology to optimize care. Front Oncol (2020) 10:1183. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01183

92. Demark-Wahnefried W, Colditz GA, Rock CL, Sedjo RL, Liu J, Wolin KY, et al. Quality of life outcomes from the exercise and nutrition enhance recovery and good health for you (ENERGY)-randomized weight loss trial among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2015) 154(2):329–37. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3627-5

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Neoplasm, Tele-health, Meta-analysis, Physiological outcomes, Psychological outcomes

Citation: Ajmera P, Miraj M, Kalra S, Goyal RK, Chorsiya V, Shaik RA, Alzhrani M, Alanazi A, Alqahtani M, Miraj SA, Pawaria S and Mehta V (2023) Impact of telehealth interventions on physiological and psychological outcomes in breast cancer survivors: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Front. Oncol. 12:1017343. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1017343

Received: 11 August 2022; Accepted: 15 November 2022;

Published: 05 January 2023.

Edited by:

Gianluca Franceschini, Agostino Gemelli University Polyclinic (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Marco Invernizzi, University of Eastern Piedmont, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Ajmera, Miraj, Kalra, Goyal, Chorsiya, Shaik, Alzhrani, Alanazi, Alqahtani, Miraj, Pawaria and Mehta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Miraj, bS5tb2xsYUBtdS5lZHUuc2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.