94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 13 January 2022

Sec. Breast Cancer

Volume 11 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.802177

This article is part of the Research Topic Advancements in Metastatic Breast Cancer: Predictive and Prognostic Biomarkers, and Molecular Mechanisms View all 17 articles

Nawale Hajjaji1,2*†

Nawale Hajjaji1,2*† Soulaimane Aboulouard1

Soulaimane Aboulouard1 Tristan Cardon1

Tristan Cardon1 Delphine Bertin1,2

Delphine Bertin1,2 Yves-Marie Robin1,2

Yves-Marie Robin1,2 Isabelle Fournier1,3*

Isabelle Fournier1,3* Michel Salzet1,3*

Michel Salzet1,3*Integrating tumor heterogeneity in the drug discovery process is a key challenge to tackle breast cancer resistance. Identifying protein targets for functionally distinct tumor clones is particularly important to tailor therapy to the heterogeneous tumor subpopulations and achieve clonal theranostics. For this purpose, we performed an unsupervised, label-free, spatially resolved shotgun proteomics guided by MALDI mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) on 124 selected tumor clonal areas from early luminal breast cancers, tumor stroma, and breast cancer metastases. 2868 proteins were identified. The main protein classes found in the clonal proteome dataset were enzymes, cytoskeletal proteins, membrane-traffic, translational or scaffold proteins, or transporters. As a comparison, gene-specific transcriptional regulators, chromatin related proteins or transmembrane signal receptor were more abundant in the TCGA dataset. Moreover, 26 mutated proteins have been identified. Similarly, expanding the search to alternative proteins databases retrieved 126 alternative proteins in the clonal proteome dataset. Most of these alternative proteins were coded mainly from non-coding RNA. To fully understand the molecular information brought by our approach and its relevance to drug target discovery, the clonal proteomic dataset was further compared to the TCGA breast cancer database and two transcriptomic panels, BC360 (nanoString®) and CDx (Foundation One®). We retrieved 139 pathways in the clonal proteome dataset. Only 55% of these pathways were also present in the TCGA dataset, 68% in BC360 and 50% in CDx. Seven of these pathways have been suggested as candidate for drug targeting, 22 have been associated with breast cancer in experimental or clinical reports, the remaining 19 pathways have been understudied in breast cancer. Among the anticancer drugs, 35 drugs matched uniquely with the clonal proteome dataset, with only 7 of them already approved in breast cancer. The number of target and drug interactions with non-anticancer drugs (such as agents targeting the cardiovascular system, metabolism, the musculoskeletal or the nervous systems) was higher in the clonal proteome dataset (540 interactions) compared to TCGA (83 interactions), BC360 (419 interactions), or CDx (172 interactions). Many of the protein targets identified and drugs screened were clinically relevant to breast cancer and are in clinical trials. Thus, we described the non-redundant knowledge brought by this clone-tailored approach compared to TCGA or transcriptomic panels, the targetable proteins identified in the clonal proteome dataset, and the potential of this approach for drug discovery and repurposing through drug interactions with antineoplastic agents and non-anticancer drugs.

● Spatially resolved mass spectrometry guided by MALDI mass spectrometry imaging allows an in-depth proteomic screening for drug targets in luminal breast cancers.

● This unsupervised and unlabeled technology performed on intact tumors provides a multidimensional analysis of the clonal proteome including conventional proteins, mutated proteins, and alternative proteins.

● The rich clonal proteomic information generated was not redundant with TCGA or transcriptomic panels, and showed pathways exclusively found in the proteomic analysis.

● A large proportion of the proteins in the clonal proteome dataset were druggable with both antineoplastic agents and non-anticancer drugs, showing the potential application to drug repurposing.

● A significant number of the proteins detected had partially or not yet known drug interactions, showing the potential for discovery.

● Many of the protein targets identified and drugs screened were clinically relevant to breast cancer.

Breast cancer remains the most frequent cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death among women in Europe (globocan iarc). The rational development of targeted drugs based on molecular knowledge of cancer is a major therapeutic progress that brought substantial hope to improving patients’ outcome. However, the complex biological features of this disease, especially the existence of multiple heterogeneous tumor subclones (1), have prevented its eradication, driven drug resistance, including to targeted therapies (2), and has been identified as a marker of poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (3, 4). Integrating tumor heterogeneity in the target discovery process to tailor therapies to the clones present within the tumor is a paradigm shift to reach clonal theranostics. However, technological limitations and breast tumors molecular features have prevented this breakthrough. In fact, this implies the ability to isolate and screen tumor clones separately to understand their biology, find vulnerabilities and identify potential druggable targets.

Historically, sequencing methods revealed genomic alterations driving the emergence of clonal cancer cell subpopulations (5, 6). Beside this genomic heterogeneity, non-genetic mechanisms, such as dynamic transcriptional, translational and metabolic adaptations also contribute to tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance or tolerance (7, 8). Thus, beside the technologies used to detect gene mutations or single nucleotide polymorphisms, technics exploring transcript expression (9), proteins (10), or metabolites (11) also showed significant tumor heterogeneity, demonstrating that heterogeneity is constantly present from the structural to the functional levels of the tumor. Therefore, approaches complementary to genomics are necessary to comprehensively analyze tumor heterogeneity.

Yielding large molecular information on tumor clones from small samples for biomarker or drug target discovery represents a technical challenge despite the advent of single cell technologies (12). Current single-cell sequencing methods require suspensions of cells for isolation, whereas in routine clinical practice the majority of tumors after surgery or biopsy are fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin blocks. Moreover, analyzing isolated cells does not capture cell-cell interaction in the microenvironment. Spatial transcriptomics represent a powerful tool to access in situ functional information about tumor subpopulations (13), and offers the possibility to be multiplexed to fluorescence in situ hybridization (14, 15). However, some limitations include the poor prediction of protein expression from RNA expression (16) or transcriptional errors (17) that may hamper drug target inference. Moreover, transcriptome measurements may not necessarily capture adaptive responses that involve post-transcriptional mechanisms such as translation or metabolic reprogramming (18–20). Focusing on tumor proteomic landscape has the advantage of recapitulating both the expressed genomic landscape and the non-genetic processes. This could be of particular interest in tumors with a relatively low mutational burden such as breast cancers (21). Besides, given that the vast majority of drug targets are proteins (22), a proteomic approach allows direct target detection. Technologies specifically dedicated to study the spatial proteomic heterogeneity of tumors, combined or not with transcriptomics are scarce. Most rely on selected and labeled markers, limited in number, for instance with multiplexed pathology methods (23–25), which is not suited for discovery.

We asked whether matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) combined with microproteomics could screen for relevant druggable protein targets from breast cancer clones to guide clonal theranostics. MALDI MSI enables the spatially resolved label-free imaging of different molecular classes, including proteins, in their histological context (26–28), thus revealing functionally heterogeneous tumor subpopulations in solid tumors (29, 30). The selected subclones are further extracted in situ using a semi-automated standardized microproteomic technology to perform a full proteomic profiling with LC-MS/MS (31) comprising identification of referenced proteins but also proteins presenting mutations or alternative proteins issued from the non-coding parts of RNA or non-coding RNA. This approach constitutes a unique tool to characterize the proteomic profile of functionally distinct tumor subpopulations, which we denoted the clonal proteome. Our aims were (i) to map and characterize luminal breast cancers’ functional clones using MALDI MSI combined with microproteomics, and (ii) determine the potential of this approach to identify clinically relevant druggable protein targets in luminal tumors.

We carried out a retrospective single center study at Centre Oscar Lambret (Lille, France) to analyze the spatial heterogeneity of primary breast tumors and breast cancer metastases. Eligible patients were women with early breast cancer or metastatic luminal breast cancer with available FFPE tumor tissue after a surgical procedure or a fine needle biopsy. Our pathologists selected 52 primary tumors and 24 metastases from 51 and 12 patients respectively. All patients still alive gave their informed consent. This retrospective study was approved by the local institutional clinical research committee. The clinico-pathological data of both patient series were listed in Table 1 (Supplementary Table 1).

For each tumor sample, 2 consecutive sections of 8 micrometers were cut of off the block. The first section was used to perform the MALDI MSI analysis (27, 32–34). The tumor tissue section was deposited on ITO-coated glass slides (LaserBio Labs, Valbonne, France) and vacuum-dried during 15 min. Protein demasking was performed with washing with NH4HCO3 10mM for 5 min twice, then TRIS HCl 20mM pH9 for 30 min at 95°C. Tryptic digestion was performed (40μg/mL, dissolved in NH4HCO3 50mM) by micro-spraying trypsin on the section surface using an HTX TM sprayer (HTX technologies, LLC), and incubation overnight at 56°C. The slide was dried in a dessicator prior to deposition of a solid ionic matrix HCCA-aniline using an HTX TM sprayer (HTX technologies, LLC). Briefly, 36 μL of aniline were added to 5 mL of a solution of 10 mg/mL HCCA dissolved in ACN/0.1% TFA aqueous (7:3, v/v). A real-time control of the deposition was performed by monitoring scattered light to obtain a uniform layer of matrix. The MALDI mass spectrometry images were performed on a RapifleX Tissuetyper MALDI TOF/TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) equipped with a smartbeam 3D laser. The MSI mass spectra were acquired in the positive delayed extraction reflectron mode using the 500-3000 m/z range, and averaged from 200 laser shots per pixel, using a 70μm spatial resolution raster.

The MALDI-MSI data were analyzed using SCiLS Lab software (SCiLS Lab 2019, SCiLS GmbH). Common processing methods for MALDI MSI were applied with a baseline removal using a convolution method and data were normalized using Total Ion Count (TIC) method (35, 36). Then, the resulting pre-processing data were clustered to obtain a spatial segmentation using the bisecting k means algorithm (37). Different spatial segmentations were performed. First, an individual segmentation was applied to each tissue separately. Then, the data from all tissues were clustered together to obtain a global segmentation. Briefly, the spatial segmentation consists of grouping all spectra according to their similarity using a clustering algorithm that apply a color code to all pixels of a same cluster. Colors are arbitrarily assigned to clusters; several disconnected regions can have the same color if they share the same molecular content. To limit the pixel-to-pixel variability, edge-preserving image denoising was applied. The segmentation results were represented on a dendrogram resulting from a hierarchical clustering. The branches of the dendrogram were defined based on a distance calculation between each cluster. The manual selection of different branches of the dendrogram allows further segmentation of selected clusters to visualize more regions with distinct molecular composition. Each color-coded region identified a proteomic tumor clone. The regions/clones of interest were then subjected to on-tissue microproteomics, i.e. microdigestion and microextraction, to perform nanoLC-MS & MS/MS analysis of the extract for in-depth protein identification.

Superimposing the molecular image with the immunochemistry image allowed selection of the subclonal areas to be submitted to microproteomics using the second consecutive 8 μm tumor sections. The tissue sections were deposited on polylysine glass slides, and microdigested with a trypsin solution deposited with a microspotter. On-tissue trypsin digestion was performed using a Chemical Inkjet Printer (CHIP-100, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The trypsin solution (40µg/mL, 50mM NH4HCO3 buffer) was deposited on a region defined to 1mm² for 2h. During this time, the trypsin was changed every half-hour. With 350 cycles and 450pl per spot, a total of 6.3µg was deposited. After microdigestion, the spot content was micropextracted by liquid microjunction using the TriVersa Nanomate (Advion Biosciences Inc., Ithaca, NY, USA) using Liquid Extraction and Surface Analysis (LESA) settings. With 3 different solvent mixtures composed of 0.1% TFA, ACN/0.1% TFA (8:2, v/v), and MeOH/0.1% TFA (7:3, v/v). A complete LESA sequence run 2 cycles for each mixture composed of an aspiration (2µL), a mixing onto the tissue, and a dispensing into low-binding tubes. For each tumor area of interest, 2 microextraction sequences were run and pooled (38).

After liquid extraction, samples were freeze-dried in a SpeedVac concentrator (SPD131DPA, ThermoScientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), reconstituted with 10µL 0.1% TFA and subjected to solid-phase extraction to remove salts and concentrate the peptides. This was done using a C-18 Ziptip (Millipore, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France), eluted with ACN/0.1% TFA (8:2, v/v) and then the samples were dried for storage. Before analysis, samples were suspended in 20µL ACN/0.1% FA (2:98, v/v), deposited in vials and 10µL were injected for analysis. The separation prior to the MS used online reversed-phase chromatography coupled with a Proxeon Easy-nLC-1000 system (Thermo Scientific) equipped with an Acclaim PepMap trap column (75 μm ID x 2 cm, Thermo Scientific) and C18 packed tip Acclaim PepMap RSLC column (75 μm ID x 50 cm, Thermo Scientific). Peptides were separated using an increasing amount of acetonitrile (5%-40% over 140 minutes) and a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The LC eluent was electrosprayed directly from the analytical column and a voltage of 2 kV was applied via the liquid junction of the nanospray source. The chromatography system was coupled to a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer was programmed to acquire in a data-dependent mode. The survey scans were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer operated at 70,000 (FWHM) resolving power. A mass range of 200 to 2000 m/z and a target of 3E6 ions were used for the survey scans. Precursors observed with an intensity over 500 counts were selected “on the fly” for ion trap collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation with an isolation window of 4 amu and a normalized collision energy of 30%. A target of 5000 ions and a maximum injection time of 120 ms were used for CID MS2 spectra. The method was set to analyze the top 10 most intense ions from the survey scan and a dynamic exclusion was enabled for 20 s. Extracts were sequenced randomly to avoid batch effect.

All MS data were processed with MaxQuant (39, 40) (Version 1.5.6.5) using the Andromeda (41) search engine. The proteins were identified by searching MS and MS/MS data against the Decoy version of the complete proteome for Homo sapiens in the UniProt database (Release March 2017, 70941 entries) combined with 262 commonly detected contaminants. Trypsin specificity was used for digestion mode, with N-terminal acetylation and methionine oxidation selected as a variable. We allowed up to two missed cleavages. Initial mass accuracy of 6 ppm was selected for MS spectra, and the MS/MS tolerance was set to 20 ppm for the HCD data. False discovery rate (FDR) at the peptide spectrum matches (PSM) and protein level was set to 1%. Relative, label-free quantification of the proteins was conducted into MaxQuant using the MaxLFQ algorithm (42) with default parameters. Analysis of the identified proteins was performed using Perseus software (http://www.perseus-framework.org/) (version 1.6.12.0). The file containing the information from the identification was filtered to remove hits from the reverse database, proteins with only modified peptides and potential contaminants. The LFQ intensity was logarithmized (log2[x]). Categorical annotation of the rows was used to define the different groups. Principal component analysis (PCA) was done to compare the protein content of each sample. Multiple-sample tests were performed using ANOVA with a p-value of 1%. Normalization was achieved using a Z-score with matrix access by rows. Only proteins that were significant by ANOVA were retained. The hierarchical clustering and profile plots of the statistically significant proteins were performed and visualized with Perseus. Functional annotation and characterization of the identified proteins were performed using FunRich software (version 3) and STRING (version 9.1, http://stringdb.org) (43). Pearson’s correlation coefficient and matrix representation were generated in R software using corrplot package. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and Cytoscape software (version 3.6.1) were used for the biological process analysis of the clusters selected from the heatmap. The data sets were deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository (44) with Data available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD024134.

The Elsevier’s Pathway Studio version 10.0 (Ariadne Genomics/Elsevier) was used to deduce relationships among differentially expressed proteomics protein candidates using the Ariadne ResNet database (45, 46). “Subnetwork Enrichment Analysis” (SNEA) algorithm was selected to extract statistically significant altered biological and functional pathways pertaining to each identified set of protein hits among the different groups. SNEA utilizes Fisher’s statistical test set to determine if there are nonrandom associations between two categorical variables organized by specific relationships. Integrated Venn diagram analysis was performed using “the InteractiVenn”: a web-based tool for the analysis of complex data sets (47). Annotation analysis of gene ontology terms for the identified proteins was performed using PANTHER Classification System (version 15.0, http://www.pantherdb.org) (48). Interaction network analyses were performed with Cytoscape (version 3.7.2) and the Cluego application (version 2.5.5) to interpret the lists of genes and proteins by selecting representative Gene Ontology terms and pathways from multiple ontologies and visualize them into functionally organized networks (49). The ontologies used included GO_BiologicalProcess-EBI-UniProt-GOA_27.02.2019, GO_CellularComponent-EBI-UniProt-GOA_27.02.2019, GO_ImmuneSystemProcess-EBI-UniProt-GOA_27.02.2019, GO_MolecularFunction-EBI-UniProt-GOA_27.02.2019, KEGG_27.02.2019, REACTOME_Pathways_27.02.2019, REACTOME_Reactions_27.02.2019, and WikiPathways_27.02.2019. The GO level range was 3 to 8, and groups with more than 50% overlap were merged. The statistical test used was enrichment/depletion (two-sided hypergeometric test) with a Bonferroni step down correction method.

Protein identification was also performed using the mutation-specific database (50). XMan v2 database contains 2 539 031 mutated peptide sequences from 17 599 Homo sapiens proteins (2 377 103 are missense and 161 928 are nonsense mutations). The interrogation was performed by Proteome Discoverer 2.3 software and Sequest HT package, using an iterative method. The precursor mass tolerance was set to 15 ppm and the fragment mass tolerance was set to 0.02 Da. For high confidence result, the FDR values were specified to 1%. A filter with a minimum Xcorr of 2 was applied. The generated result file was filtered using a Python script to remove unmutated peptides. All mutations were then manually checked based on MS/MS spectra profile.

RAW data obtained by nanoLC-MS/MS analysis were processed using Proteome Discoverer V2.3 (Thermo Scientific) with the following parameters: Trypsin as an enzyme, 2 missed cleavages, methionine oxidation as a variable modification, Precursor Mass Tolerance: 10 ppm and Fragment mass tolerance: 0.6 Da. The validation was performed using Percolator with an FDR set to 0.001%. A consensus workflow was then applied for the statistical arrangement, using the high confidence protein identification. The protein database was uploaded from Openprot (https://openprot.org/) and included reference proteins, novel isoforms, and alternative proteins predicted from both Ensembl and RefSeq annotations (GRCh38.83, GRCh38.p7) (51).

To compare our proteomic data with genomic and transcriptomic datasets used in breast cancer, the reference genes of the proteins were contrasted to publically available TCGA, BC360 (nanoString®) and CDx (Foundation One®) datasets. Breast cancer genomic alterations were collected from the TCGA web portal using “breast cancer” as keyword in the search engine. The TCGA gene list is in Supplementary Material 1. The gene list of the BC360 and CDx panels were obtained from nanoString and Foundation One websites. The gene lists are in Supplementary Materials 2 and 3 respectively.

DrugCentral (http://drugcentral.org) is an online drug information resource created and maintained by the Division of Translational Informatics at University of New Mexico in collaboration with the IDG Illuminating the Druggable Genome (IDG) (https://druggablegenome.net/index) (52). DrugCentral provides information on active ingredients, chemical entities, pharmaceutical products, the mode of action of drugs, indications, and pharmacologic action. Data is monitored on FDA, EMA, and PMDA for new drug approval on regular basis. Supported target search terms are HUGO gene symbols, Uniprot accessions and target names, and Swissprot identifiers. We used the WHO anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification to categorize drugs.

The druggability level of the targets was classified using the definition of the Illuminating the Druggable Genome Knowledge Management Center (IDG-KMC) based on four target development levels (TDLs) categorized as follows: (i) Tclin: targets with activities in DrugCentral (i.e., approved drugs) and known mechanism of action, (ii) Tchem: targets with activities in ChEMBL or DrugCentral that satisfy the activity thresholds detailed in https://druggablegenome.net/ProteinFam, (iii) Tbio: targets with no known drug or small molecule activities that satisfy the activity thresholds and criteria (detailed in https://druggablegenome.net/ProteinFam), (iv) Tdark: targets with virtually no known drug or small molecule activities that satisfy the criteria defined by IDG-KMC.

ClinicalTrials.gov is a web-based resource that provides information on publicly and privately supported clinical studies on a wide range of diseases and conditions (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home). The web site is maintained by the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (US). Information on ClinicalTrials.gov is provided and updated by the sponsor or principal investigator of the clinical study. 6159 studies corresponding to interventional clinical trials conducted in breast cancer patients were retrieved using “breast cancer” as the medical condition and “drug” as other condition. Results were also filtered to select “Adult” and “Older Adult”, and “Interventional Studies”.

Descriptive analyses used frequency of distribution, median, quartiles and extremes. Survival analyses were performed using the breast cancer Kaplan-Meier plotter online tool (https://kmplot.com; n=3955). The database sources included GEO, EGA, and TCGA (53). A multiple gene testing was run using available cohorts of patients with estrogen receptor positive and HER2 negative disease to analyze the reference genes association with distant metastases free survival (DMFS) and overall survival (OS). A logrank p<0.05 was considered significant.

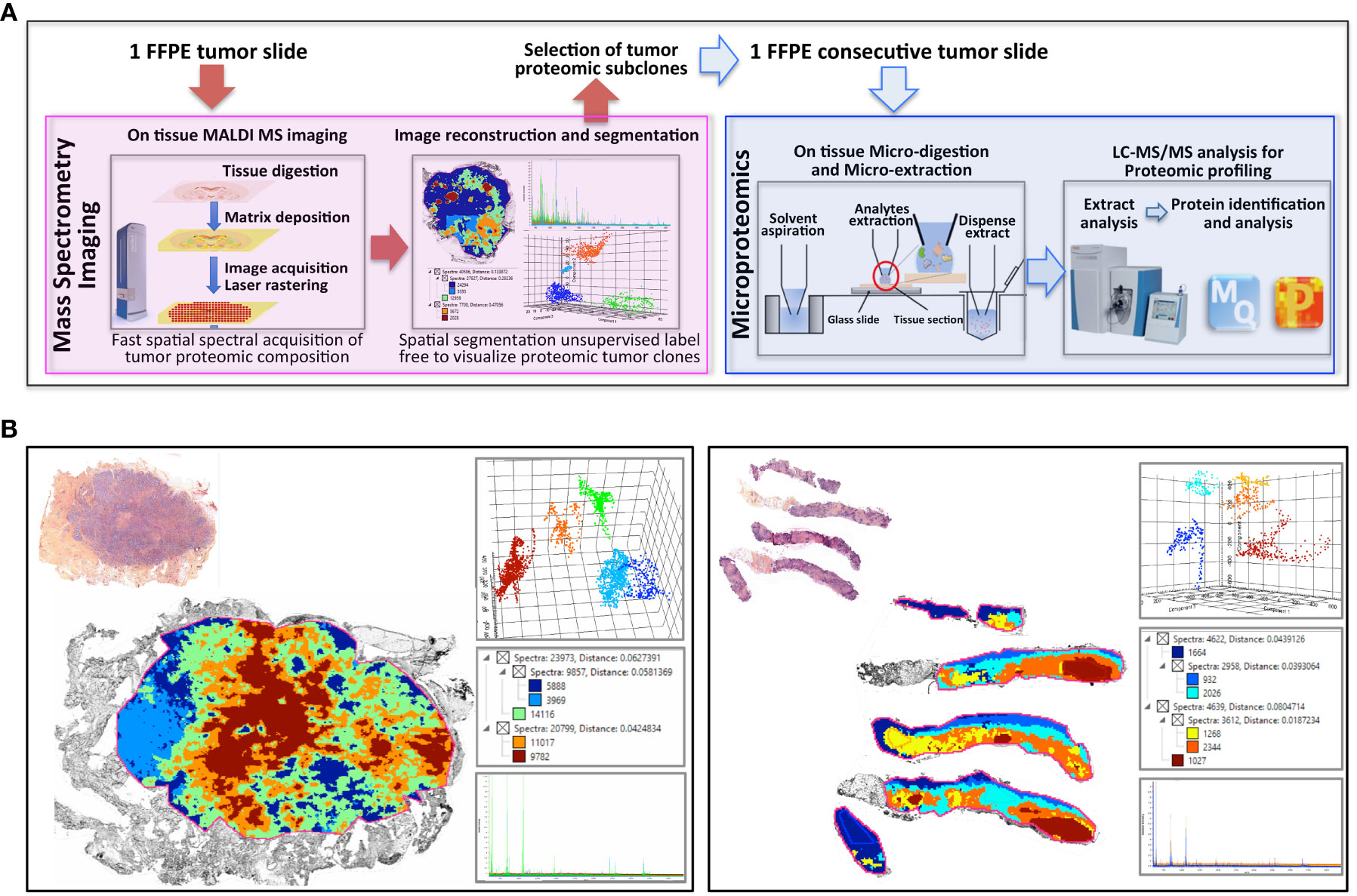

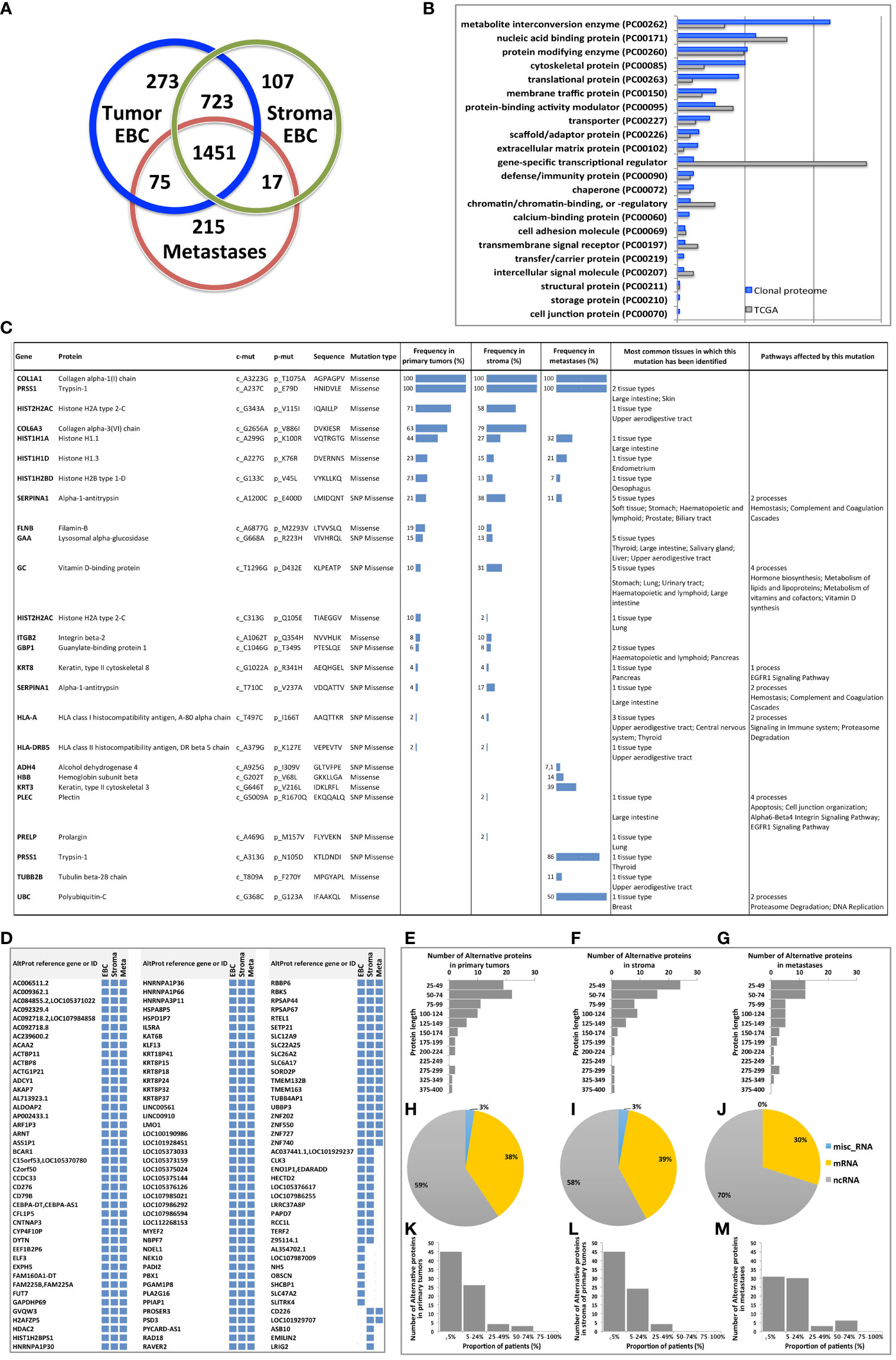

The workflow described in Figure 1A was applied to two FFPE tumor slides to provide a spatially resolved unsupervised and unlabeled visualization of breast cancer spatial heterogeneity, and an in-depth proteomic profiling. The MALDI MSI on-tissue spatial analysis mapped high molecular weight peptide composition on the first tumor slide. The spectral data obtained were clustered by the bisecting k-means method, which attributed color-coded groups to tumors areas according to the similarity of their proteomic signature. Manual group splitting (group segmentation) was limited to 3 in order to map only main functional differences between tumor subpopulations. Imaging revealed distinct proteomic clones, as illustrated in Figure 1B showing representative MALDI MS images of a primary tumor and a metastasis sample among the 76 luminal tumors analyzed (52 primary breast tumors and 24 metastases in (Supplementary Materials 4, 5). From the MSI data, 124 MSI clonal areas were retrieved corresponding to 52 areas of primary tumors, 48 areas of primary tumor stroma and 24 areas of metastases. Each of these 124 MSI clones were individually analyzed by spatially resolved shotgun proteomic. MaxLFQ algorithm was used to perform label-free quantification of proteins and resulted in a total of 2868 proteins from the 124 clonal areas (Figure 2A). The number of proteins identified did not significantly differ between tissue types (Supplementary Material 6A), or according to the sampling method, i.e. mastectomy, surgical biopsy or fine needle core biopsy (Supplementary Material 6B). Panther analysis showed that the main protein classes found in the clonal proteome dataset were enzymes, cytoskeletal proteins, membrane-traffic, translational or scaffold proteins, or transporters (Figure 2B). As a comparison, gene-specific transcriptional regulators, chromatin related proteins or transmembrane signal receptor were more abundant in the TCGA dataset (Figure 2B). Differences between primary tumors and stroma, or between primary tumors and metastases were mild among the main protein classes (Supplementary Material 7). We also detected modified proteins, specifically mutated proteins and alternative proteins. Mutations-missense at a protein-level were identified by expanding the search of the raw mass spectrometry files of our proteomic dataset against a mutated peptide database. The search identified 26 mutated proteins, 18 in primary tumors, 20 in stroma and 12 in metastases, with various frequencies (Figure 2C). Similarly, expanding the search to alternative proteins databases retrieved 126 alternative proteins in the clonal proteome dataset (Figure 2D): 79 were identified in primary tumors, 69 in stroma and 50 in metastases. The majority of these alternative proteins had a length ranging from 29 to 150 amino acids (Figures 2E–G). They were coded mainly from non-coding RNA (Figures 2H–J). These proteins were infrequent and found mostly in less than 25% of the patients (Figures 2K–M).

Figure 1 Clonal proteome analysis in breast cancer. (A) Workflow for on tissue analysis of tumor proteomic heterogeneity using spatially resolved microproteomics guided by MALDI MSI (B) The presence of tumor proteomic clones revealed by MSI was illustrated in a primary tumor (left) from a surgical resection (case 42) and a metastatic sample (right) collected with a fine needle biopsy (case 22). In each sample vignette, the MALDI MS imaging is displayed with the histological HPS picture (upper left), the principal component analysis of the proteomic clones (upper right), the segmentation tree (middle right), and the spectra of the clones (bottom right).

Figure 2 (A) The Venn diagram showing the number of proteins specific or shared among primary tumors (blue), stroma (green) and metastases (red). (B) Distribution of protein classes (in %) in the clonal proteome dataset (in blue) compared with TCGA dataset (in grey). (C) Mutated proteins identified using mass spectrometry, with their frequency in primary tumors, stroma and metastases, and the tissues in which they have been reported, along with the processes they affected. (D) 126 Alternative proteins identified by mass spectrometry; their length is indicated in (E) primary tumor samples, (F) stroma samples and (G) metastases. Their coding RNA distribution is shown in (H–J), respectively. The frequency of alternative proteins among patients is shown in (K) primary tumors, (L) stroma and (M) metastases. AltProt, alternative proteins; EBC, early breast cancer; ID, identification; Meta, metastases; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

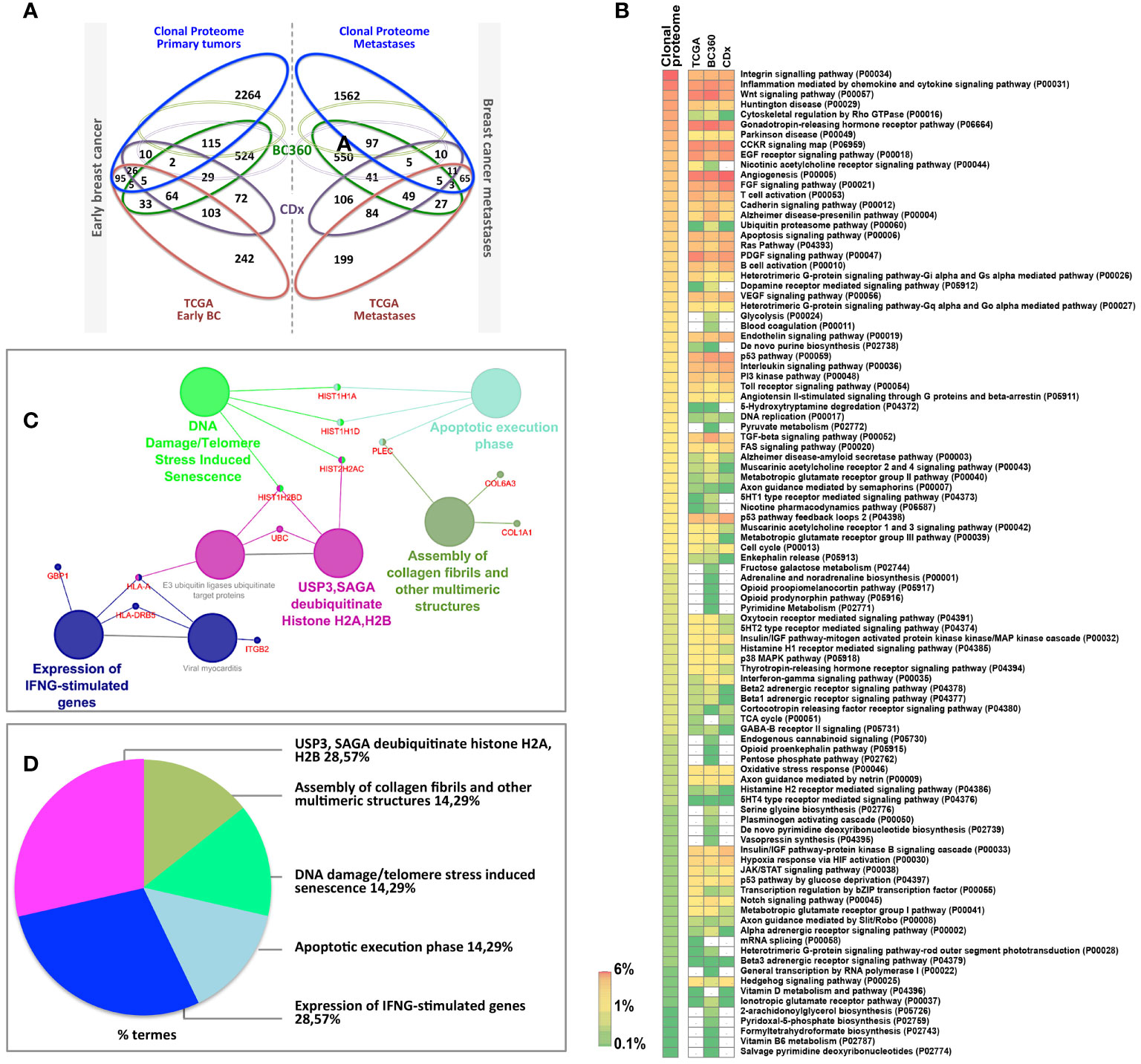

To fully understand the molecular information brought by our approach and its relevance to drug target discovery, the clonal proteomic dataset was further compared to the TCGA breast cancer database and two transcriptomic panels, BC360 (nanoString®) and CDx (Foundation One®). The Venn diagram in Figure 3A showed that only few proteins of the clonal proteomic dataset (identified by their reference gene) were shared with TCGA, BC360 or CDx panels, both in primary tumors and metastases. 2264 and 1562 proteins were exclusively found in the clonal proteome dataset of primary tumors and metastases respectively (Supplementary Material 8). Enrichment analysis using Panther software identified 139 pathways in the clonal proteome dataset. Only 55% of these pathways were also present in the TCGA dataset, 68% in BC360 and 50% in CDx. The pathways and processes identified were differentially distributed across the datasets as depicted in the heatmap in Figure 3B. Pathways over-represented in the clonal proteome dataset were integrin or inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathways, cytoskeletal regulation by Rho GTPase, the ubiquitin proteasome pathway, glycolysis, de novo purine biosynthesis or DNA replication. Under-represented processes were mainly signaling pathways or the oxidative stress response. 41 pathways were exclusive to the clonal proteome (Table 2), mainly metabolic pathways involved in amino acid, lipid or nucleic acid synthesis. Seven of these pathways have been suggested as candidate for drug targeting, 22 have been associated with breast cancer in experimental or clinical reports, the remaining 19 pathways have been understudied in breast cancer (Table 2) (54–86). The mutated proteins identified have been reported in a variety of human tissues; only mutated polyubiquitin-C has been reported in breast tissue with an impact on proteasome degradation and DNA replication. The other mutated proteins may affect hemostasis, complement and coagulation cascades, hormone biosynthesis, metabolism, EGFR1 signaling, signaling in the immune system, apoptosis, cell junction organization, or integrin signaling (Figure 2C). Enrichment analyses performed on the identified mutated proteins using their reference genes showed three main biological processes: expression of interferon gamma genes, apoptosis, and senescence (Figures 3C, D). Only 4 of the reference genes (COL6A3, COL1A1, HBB, HLA-A) were also found in TCGA or BC360 datasets (none in CDx). The functions of the alternative proteins identified are not known yet. Among their known reference genes, only 8 (ARNT, CD79B, KAT6B, LMO1, PBX1, CD276, ELF3, HDAC2) were also present in TCGA, BC360 or CDx panels.

Figure 3 (A) Venn diagram comparing the clonal proteome dataset with TCGA, BC360 and CDx panels, in primary breast cancer (left) or metastases (right). (B) Panther pathways heatmap showing gene distribution between the datasets. Pathways over-represented are colored in orange and those underrepresented in green. (C) Mutated protein networks and (D) biological processes distribution analyzed using Cytoscape and Cluego.

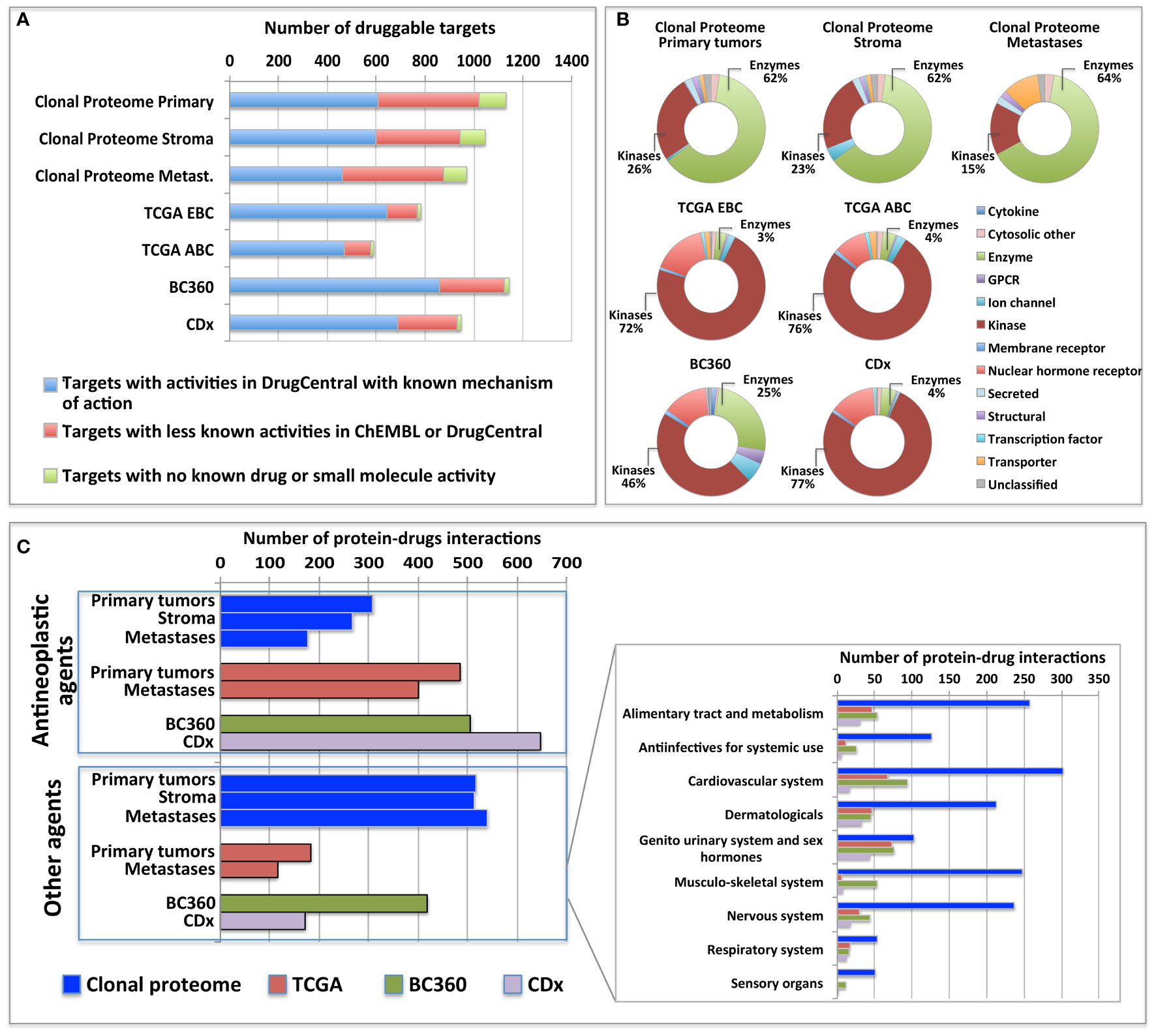

The clonal proteome dataset was reviewed against DrugCentral database to determine the number of proteins targetable, their level of druggability and their interaction with approved drugs. Among the proteins identified in the clonal proteome dataset, 1495 proteins were targetable with a level of druggability high for 52% of them (known mechanism of action and drug interaction, Tclin), while 39% had a lower level of knowledge (Tchem), and 9% had no known drug or small molecule interaction (Tbio) (Figure 4A). The highest number of druggable targets was observed in the clonal proteome compared to the genomic and transcriptomic datasets. The proportion of less known targets was also greater in the clonal proteome dataset (47%) compared to TCGA (18%), BC360 (23%) or CDx (25%) (Figure 4A). The main target classes in the clonal proteome dataset were enzymes (60%), kinases (23%) and transporters (7%), whereas kinases were dominant in the other datasets (46% to 77%) (Figure 4B). The number of protein and drug interactions with antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents were up to 309 in the clonal proteome dataset, 485 in TCGA, 506 in BC360, and 647 in CDx (Figure 4C and Supplementary Material 9). Among the anticancer drugs, 35 drugs matched uniquely with the clonal proteome dataset, with only 7 of them already approved in breast cancer. The number of target and drug interactions with non-anticancer drugs (such as agents targeting the cardiovascular system, metabolism, the musculoskeletal or the nervous systems) was higher in the clonal proteome dataset (540 interactions) compared to TCGA (83 interactions), BC360 (419 interactions), or CDx (172 interactions) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4 Druggable targets identified (A) in the clonal proteome, TCGA, CDx, and BC360 datasets using DrugCentral, and the druggability level as defined by IDG-KMC (https://druggablegenome.net/ProteinFam). Known targets (Tclin) are in blue, less known targets are in orange (Tchem) and targets with no known drug are in red (Tbio). (B) Target class distribution among the datasets, and (C) matching drugs, both approved antineoplastic drugs or other drugs (non-anticancer drugs) described using the ATC classification. ABC, advanced breast cancer; EBC, early breast cancer; Metas, metastases.

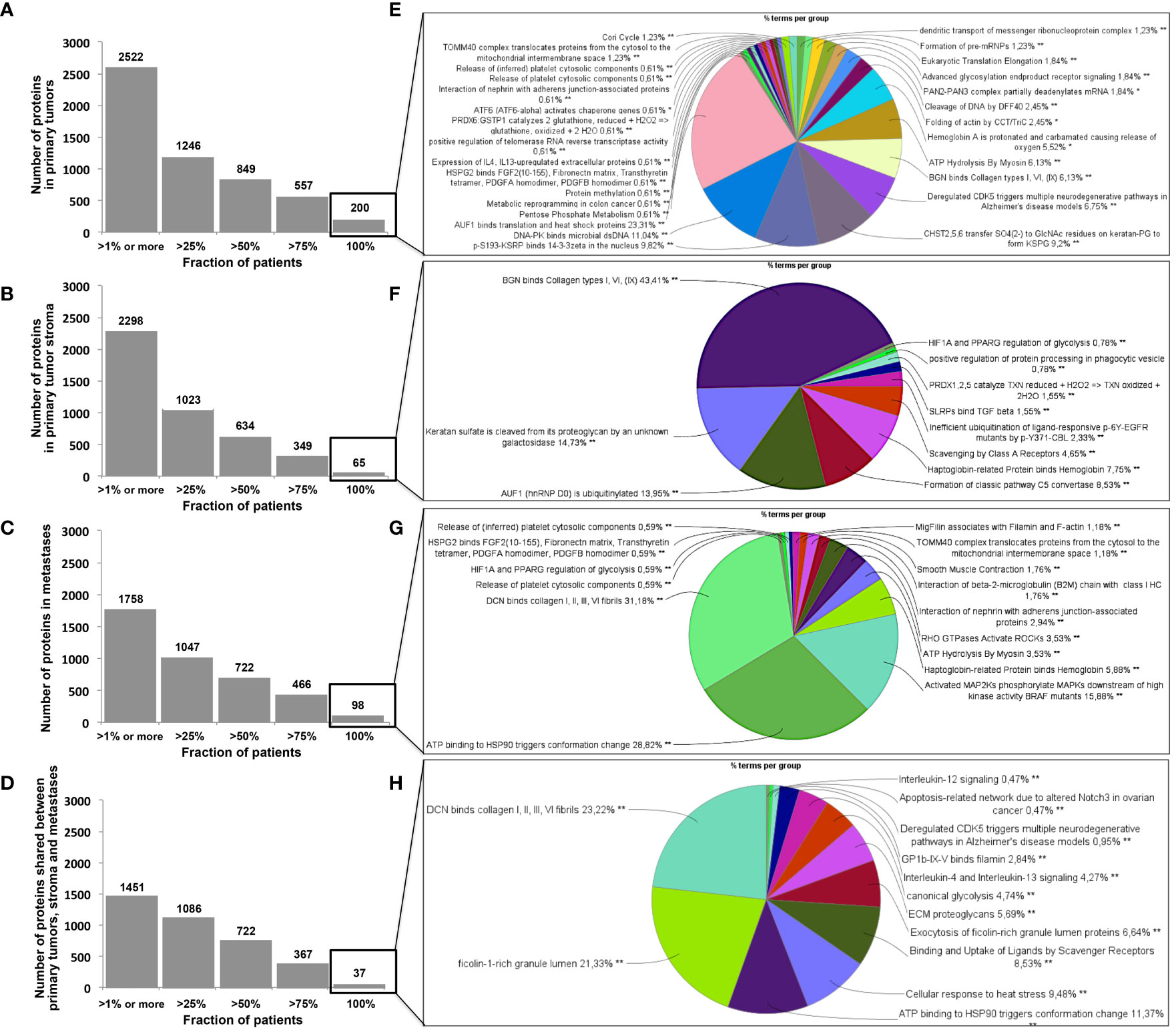

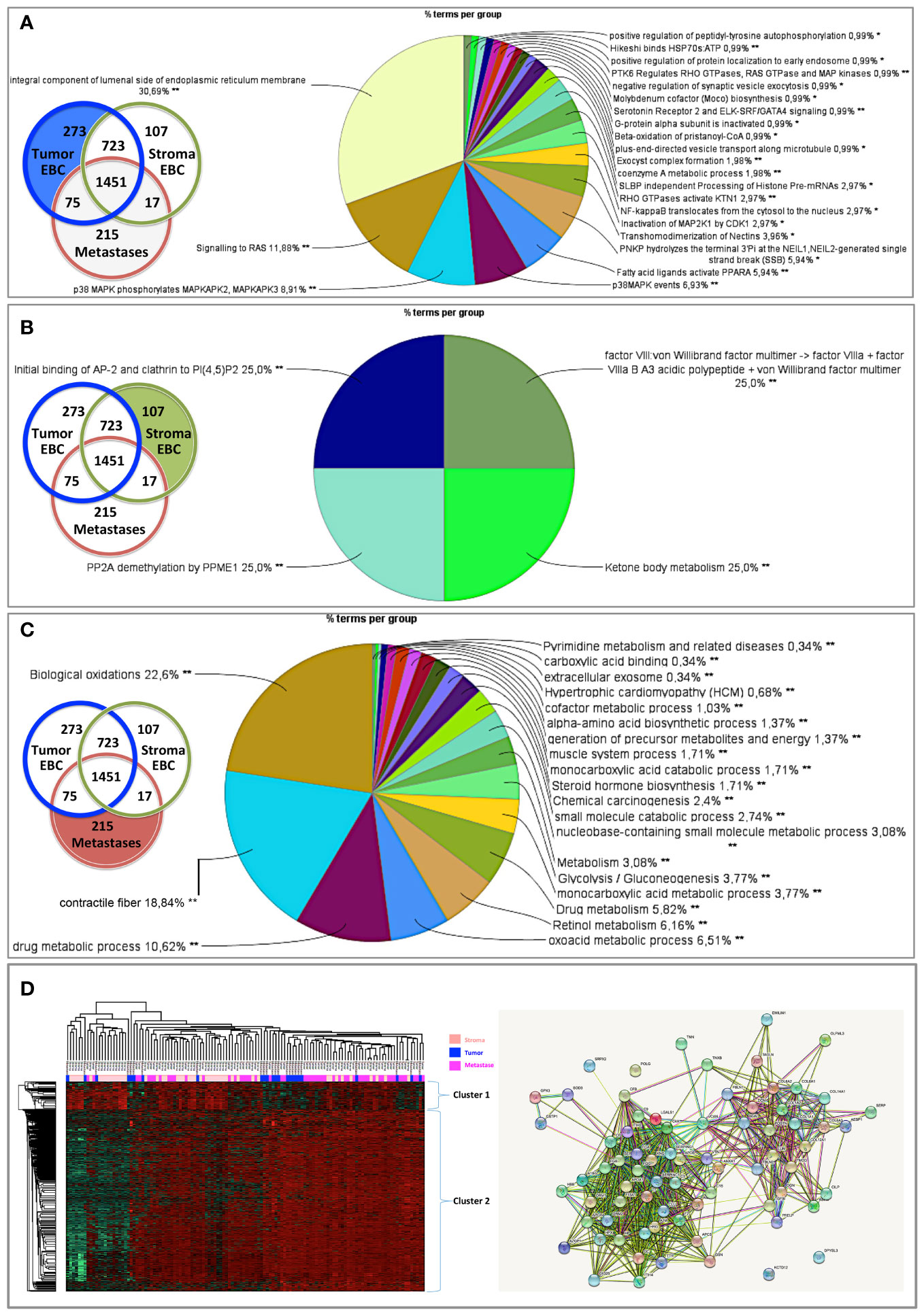

In the clonal proteome dataset, proteins shared among samples or specific to primary tumors, stroma or metastases, or differentially expressed may associate with biological processes intrinsic to breast cancer stage, tumor microenvironment, or progression. These proteins may therefore be of interest, especially if they also associate with breast cancer survival. Protein distribution among patients showed that 200 proteins were found in all primary tumor samples (Figure 5A), 65 proteins were shared among all the stromal samples (Figure 5B), 98 proteins were found in all the metastases samples (Figure 5C), and 37 proteins were present in all the 124 clonal samples (Figure 5D). Enrichment analyses for specific pathways showed as main biological processes in primary tumors AUF1, DNA-PK, S193-KSRP, or CDK5 related activities (Figure 5E), in stroma BGN activity, keratin sulfate cleavage, AUF1 ubiquitinoylation, and C5 pathway activity (Figure 5F), and in metastases DCN, HSP90, and MAP2Ks related activities (Figure 5G). In addition, ficolin-rich granule exocytosis and cellular response to heat stress were among the main processes found in all samples (Figure 5H). Enrichment analyses of proteins specific to primary tumors (n=273), stroma (n=107) or metastases (n=215) showed biological processes related to membrane components of the endoplasmic reticulum, RAS or MAPK signaling in primary tumors (Figure 6A), AP-2, clathrin, or PP2A activities or ketone body metabolism in stroma (Figure 6B), oxidation, contractile fibers processes, and drug metabolism in metastases (Figure 6C).

Figure 5 Distribution of proteins among patients in (A) primary tumors, (B) in stroma, (C) in metastases, and (D) shared in all samples. Biological processes enriched (in %) from proteins shared by all patients in (A–D) are represented as pie charts in (E–H), respectively. Analyses were performed with Cytoscape and ClueGo. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 6 Biological processes enriched from proteins specifically found in (A) primary tumors, (B) stroma, or (C) metastases. Proteins differentially expressed in (D) primary tumors, stroma and metastases were analyzed using a multiple sample test ANOVA with a p<0.01 and represented in a heat map (on the left) identifying 2 clusters separating the stroma (Cluster 1) from the primary tumor and the metastases (Cluster 2). The String networks of the clusters are shown on the bottom right Analyses were performed with Cytoscape, ClueGo and String; proportions of processes in %. *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

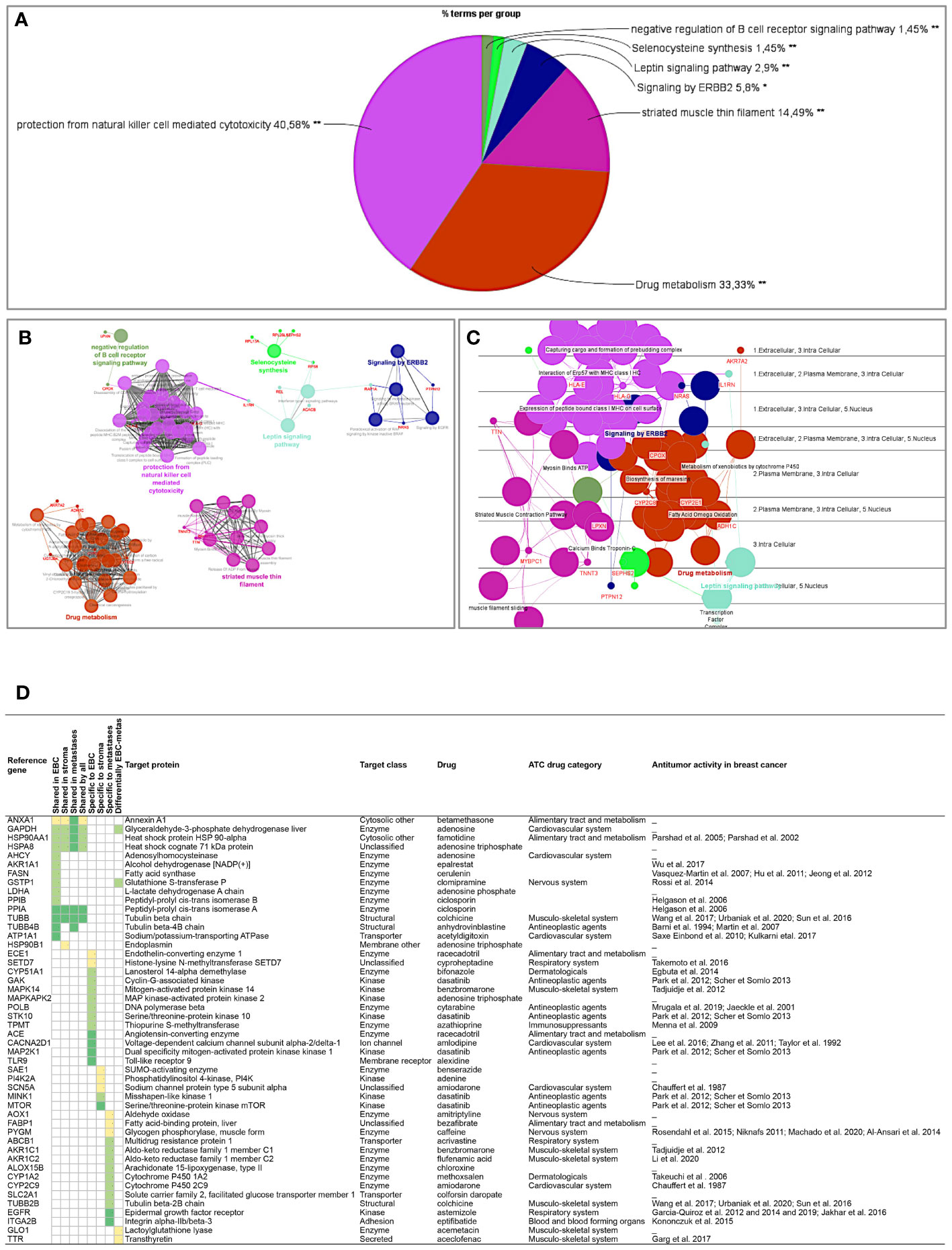

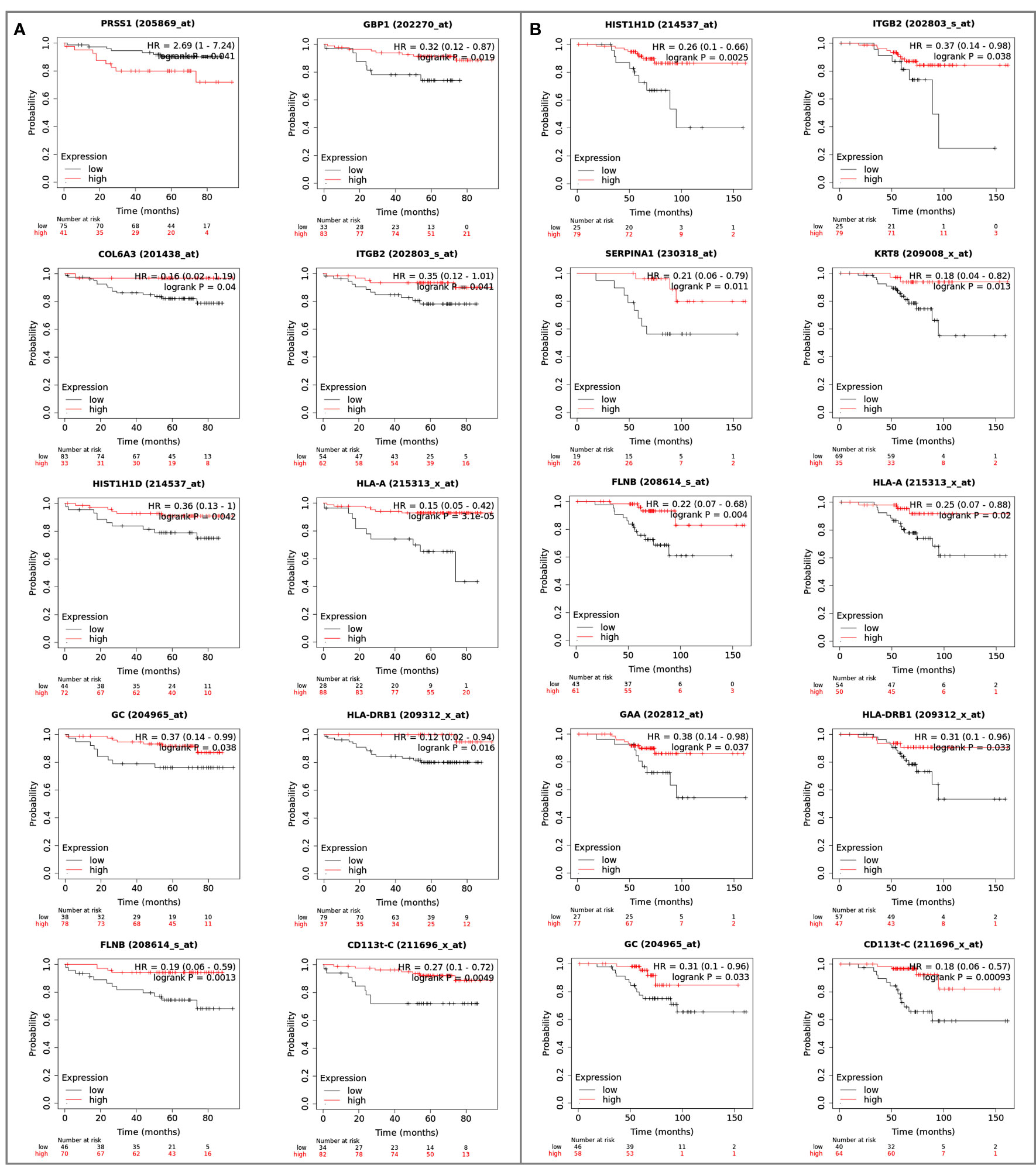

Proteins differentially expressed among primary tumors, stroma and metastases were identified using a multiple sample test ANOVA with a p<0.01. A total of 662 proteins showed a significant difference in expression among the 3 groups. Two clusters have been identified separating the stroma (Cluster 1) from the primary tumor and the metastases (Cluster 2) (Figure 6D). String analysis of Cluster 1 revealed two separated networks linked by VCAN i.e. one centered on immune response inhibition and one on collagen proteins and protein in interaction with the extracellular matrix (Supplementary Material 10). In Cluster 2, gene ontology reflects the presence of paraspeckles, VCP-NSFL1C complex, cytosolic small ribosomal subunit, cytosolic and polysomal ribosome, SNP and RNP complexes networks. KEGG Pathways identify as major networks the ones related to metabolism (lipids, glycosgelysis, pyruvate, proteins, carbon, butanoate, amino acid residues), antigen processing and presentation (Supplementary Material 10). The relationship between the proteins of interest in the clonal proteome (shared, specific or differentially expressed) with TCGA, BC360 or CDx datasets on the one hand, and with survival on the other hand was detailed in Figure 7. Less than 5% of these proteins of interest were shared with the genomic/transcriptomic datasets, and 25% were associated with distant metastases free survival (DMFS) (n=222) or overall survival (OS) (n=227). Enrichment analyses of genes associated with both breast cancer DMFS and OS showed their involvement in natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity, drug metabolism, muscle filament, ERBB2 and leptin signaling, aminoacid synthesis and B cell receptor signaling (Figures 8A–C). Among the proteins of interest, 48 (5%) had interactions with known drugs, mostly non-anticancer agents such as colchicine, acemetacin, aceclofenac (musculo-skeletal system), astemizole (respiratory system), eptifibatide (blood system), or acetyldigitoxin (cardiovascular system), which have shown anti-tumor activity experimentally in breast cancer (Figure 8D) (Supplementary Table 2). Among the mutated proteins, 10 reference genes were associated with breast cancer DMFS (Figure 9A) or OS (Figure 9B) and were involved in the response to interferon gamma.

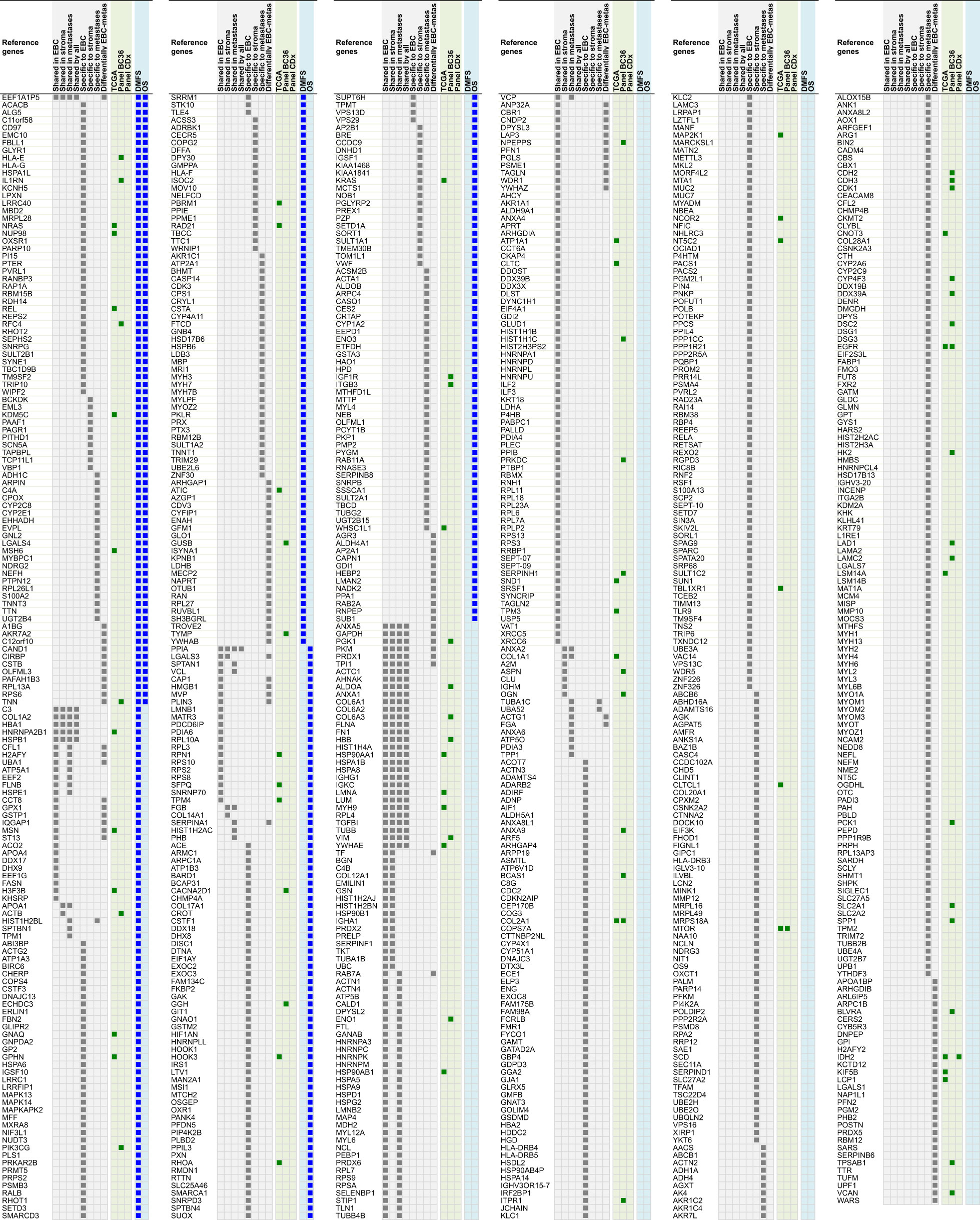

Figure 7 Proteins shared, specific or differentially expressed in the clonal proteome dataset (in grey). 892 proteins are indicated with their reference gene. Proteins also found in TCGA, BC360 or CDx datasets are indicated in green. Genes associated with DMFS or OS using publically available databases are shown in blue. EBC, early breast cancer; DMFS, distant metastases free survival; OS, overall survival.

Figure 8 Analyses of the proteins from the clonal proteome associated both with DMFS and OS, showing (A) enrichment, (B) networks analysis, (C) cerebral layout of cellular distribution, and (D) their druggability. In the table, targets with a known drug-target interaction are in dark green, those with a less known interaction are in green, and those with limited data are in yellow. The target class, matching drug name, ATC classification and reported antitumor activity in breast cancer are indicated. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Figure 9 Reference genes of the mutated proteins identified in the clonal proteome dataset associated with breast cancer (A) DMFS or (B) OS. The breast cancer Kaplan-Meier plotter tool was used to run multiple reference gene testing in publically available estrogen receptor positive and HER2 negative cohorts. A logrank p<0.05 was considered significant. DMFS, distant metastases free survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

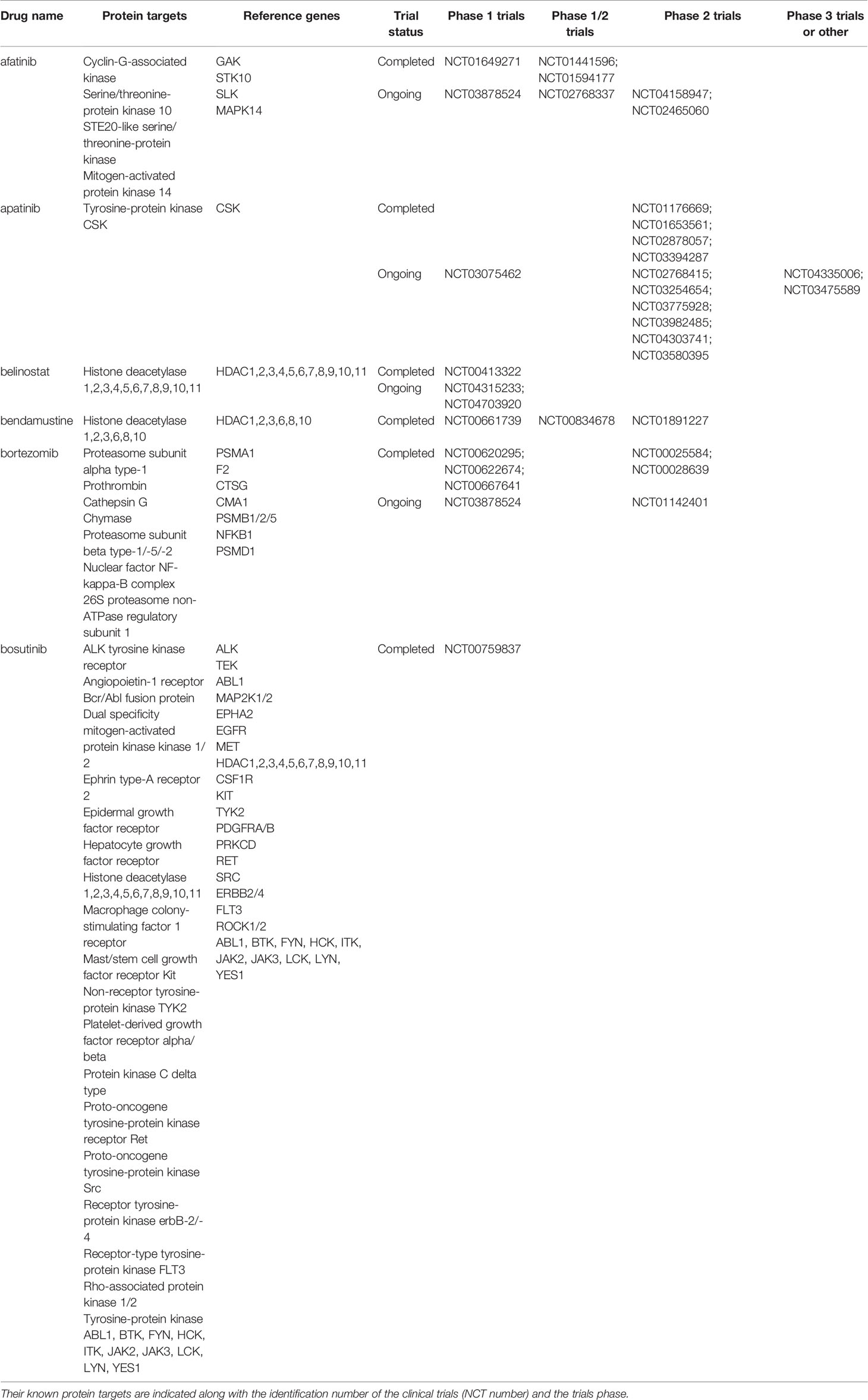

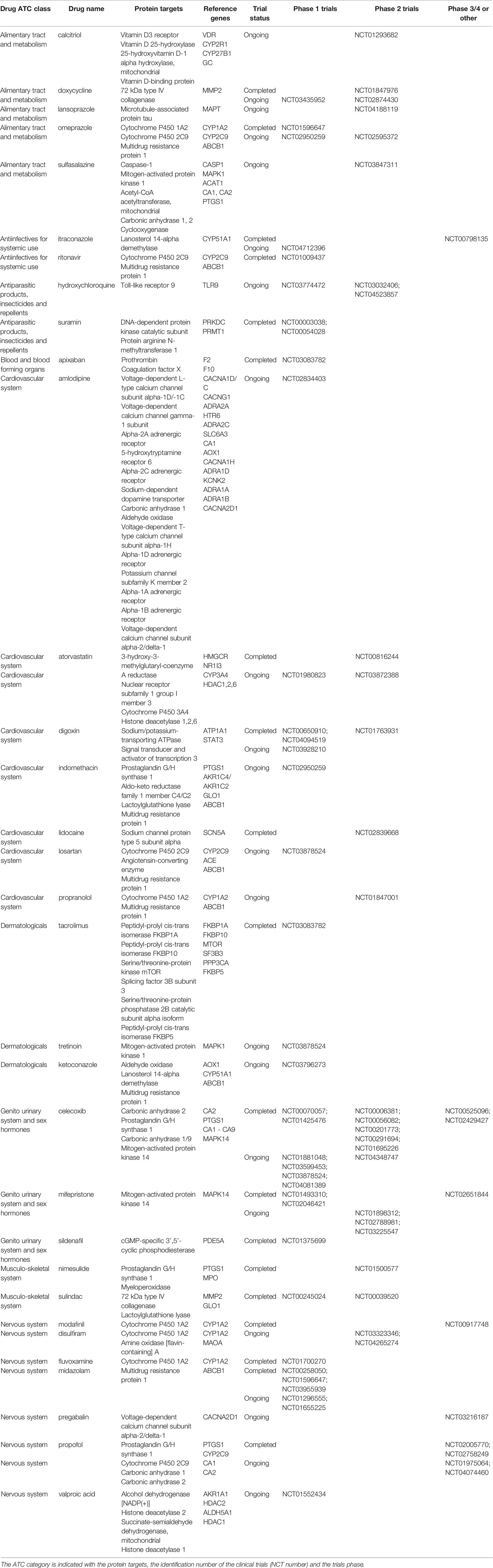

To show the clinical usefulness of the drugs identified through their interactions with protein targets of the clonal proteomic dataset, the clinicaltrial.gov database was searched to determine the proportion of these drugs that reached clinical investigation for breast cancer treatment. Among the 721 drugs accessible through the clonal proteome, 107 drugs were investigated in at least one breast cancer clinical trial: only 26 were drugs already used to treat breast cancer, 49 were antineoplastic drugs not yet approved for breast cancer and 32 were non-anticancer drugs. As expected, the 26 drugs used in breast cancer were chemotherapy molecules (taxanes, doxorubicin, eribulin, methotrexate, gemcitabine, etoposide, platinum, vinorelbine), endocrine therapy, targeted therapies such as everolimus and olaparib, and anti-HER2 therapies (trastuzumab, pertuzumab, trastuzumab emtansine, lapatinib), and steroids and zoledronic acid. Our approach identified 49 antineoplastic drugs already under clinical investigation to explore their value for repositioning in breast cancer, either in monotherapy or in combination. Their known protein targets were detailed in Table 3 along with identification number of the clinical trials and the trials phase. A majority of these drugs were investigated in phase 1 or 2 trials. Our approach also identified 32 non-anticancer drugs in trial for repurposing in breast cancer. The drugs were mainly anti-infective agents, or were involved in metabolism, the cardiovascular system or the nervous system. The ATC category of the drugs was indicated in Table 4 with the protein targets, trials ID and trial phase.

Table 3 Anticancer drugs identified through the clonal proteome that are under clinical investigation in breast cancer patients for repositioning.

Table 4 Non-anticancer drugs identified through the clonal proteome that are under clinical investigation in breast cancer patients for repurposing.

The present study showed that MALDI MSI combined with microproteomics can be used as a precision oncology tool to map and profile specific tumor subpopulations in luminal breast cancers for clonal theranostic applications. This unsupervised and label-free technology characterized the tumors conventional proteome along with the mutated and alternative proteomes, at a clonal level, to identify candidate druggable targets. Our MS imaging and microproteomic technology offers the advantage of identifying proteomic clones in situ on intact tumors. In MALDI MSI, the signal intensities are recorded for analytes at specific x,y coordinates of the tissue section in their native states. MSI produces images of the scanned area where each pixel contains the MS spectrum at this location. In the present study, 204 spectra were generated by square millimeter. Spectra are high-dimensional vectors (typically in the order of 105 dimensions), making MSI data similar to hyperspectral images. The spectrum produced by MSI at a given location represents a signature of the molecules present at this location. This proteomic signature was used to provide a label free unbiased method to map and visualize tumor functional heterogeneity and perform directed proteomic profiling on selected tumor subpopulations. This label free method is a strength compared to multiplex technics that require few selected markers (23). This makes the MSI-microproteomics technology particularly suited to discovery. So far, relevant candidate tumor targets for drug development are sought mainly among tumor genomic alterations because of their putative role as oncogenic drivers and in drug resistance. Implementation of this concept in the clinic has yielded mitigated benefit for patients (87). Moreover, the majority of oncogenic mutations are not druggable (88). Target inference from bioinformatic analyses based on genomic data may not provide knowledge precise enough about the functional state of the tumor and its diversity to identify relevant targets. Searching candidate targets among proteins circumvents these limitations. The performance and usefulness of the MSI-microproteomic technology was previously reported in solid tumors such as ovarian cancer or gliomas to help finding novel biomarkers or refining diagnosis classification (29, 30). Additionally, MSI-microproteomics tumor subpopulation scale allowed a successful identification of specific tumor stroma proteins. This is a significant advantage given the involvement of the tumor microenvironment in drug response (88), contrary to single cell methods, which cannot analyze intercellular communications in their intact microenvironment.

The clonal proteome showed a rich landscape of proteins and biological processes compared to genomic or transcriptomic datasets. The overlap with TCGA data and transcriptomic panels was limited and a distinct distribution of biological processes was observed in enrichment analyses. The clonal proteomic dataset provided more information on enzymatic and metabolic processes. A study by Patel et al. reporting on a computational assessment of drug targets showed that enzymes were the most frequent protein class and the most druggable (89). The clonal proteome revealed 41 exclusive metabolic pathways, most of them understudied in relation to breast cancer. This was of particular interest because tumor metabolic phenotype has been recognized as a hallmark of cancer and is involved in drug resistance (81). Transcriptomic panels were enriched with kinases or immune processes as expected. The discrepancy with TCGA data may be related to alternative splicing and post-translational modifications revealed by mass spectrometry analyses that cannot be predicted by genome databases. Although the bulk of targetable proteins identified might not be involved in driver oncogenic pathways to which cancer cells are addicted, focusing on common and cell type- or stage-specific proteins and processes might increase their relevance. The relevance of the protein targets was showed by the fact that a large number of proteins in the clonal proteome dataset was associated with breast cancer outcome and highlighted shared or specific biological processes of interest.

An additional strength of the present mass spectrometry technology relies on the detection of altered proteins, such as those originating from missense mutations or single nucleotide polymorphism missense mutations, and a newly recognized type of proteins named alternative proteins (or ghost proteins) because of their translation from alternative open reading frames. Although their functions cannot be predicted from their reference gene, their presence may reveal altered biological processes. Alternative proteins represent a vast class of proteins with still largely unknown biological functions, thus expanding the proteome complexity (90). This field of research offers exciting perspectives about the functions of these modified proteins related to cancer and their potential impact on drug target interactions.

Our study showed that a clonal proteomic analysis brought additional non-redundant molecular information. The proteins and pathways uniquely identified with this clonal approach may offer opportunities to identify novel drug targets. Drug development struggles with the molecular heterogeneity of tumor subpopulations, potentially leading to a differential target expression among cancer cells, which contributes to drug resistance. This has stimulated the development of multi-targeted therapeutic strategies (91, 92), facilitated by the fast expansion of the drug pipeline. Interestingly, a high proportion of the proteins in the clonal proteome dataset were druggable, with interactions with a variety of drug classes, either antineoplastic agents or non-anticancer drugs. We showed that many of these drugs, both antineoplastic agents and non-anticancer drugs, were already under clinical investigation for breast cancer treatment. This underlines the clinical relevance of using this approach for clone-tailored strategies of systematic high-throughput unbiased drug target screening for drug combination or repositioning (93). A significant number of proteins had partially or not yet known drug interactions, showing also the potential of our approach for discovery. Despite the recognition of breast cancer heterogeneity, technical limitations hampered the implementation of clonal theranostics in practice. MSI-microproteomics technology revealed more edges of breast cancer heterogeneity and bridges the technological gap to allow contemplating a paradigm shift from treating one main detectable tumor clone (with current technics) to strategies taking into account several functional clones. To tackle tumor complexity, system biology approaches are developing to reveal therapeutic opportunities associated with the multiple dimensions of cancer through integration of tumor genome, phenome and other omics data (94, 95). Accessing sufficient quantities of tumor tissue to perform all the omics analyses represents a technical challenge. Our technology uses only a limited amount of tumor tissue while maintaining the whole tissue section integrity allowing it to be re-used for additional experiments. For this reason and the large amount of data generated, the MSI-microproteomic technology is suited to multiomic strategies.

In conclusion, spatially resolved MSI-guided microproteomics is a unique tool to perform a label-free multidimensional proteomic characterization of intratumor heterogeneity for clone-tailored drug target screening. This new approach is adapted to drug target discovery and repurposing to achieve clonal theranostics. Moreover, it is applicable in routine clinical care and its scalability thanks to the speed of analysis of current and next generation mass spectrometry instruments, makes MSI-microproteomics integration to precision oncology tools foreseeable in a near future to implement clone-tailored therapies.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the local Research and Ethics Committee (Centre Oscar Lambret). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

NH wrote the manuscript original draft. NH designed the study. SA and NH performed the analyses. NH and DB selected and collected the breast cancer samples. Y-MR and DB performed histology and validated diagnostics. NH, SA, TC, IF, and MS analyzed the data. IF, MS, TC, and SA corrected the manuscript. NH, IF, and MS supervised the project and MS, IF, and NH provided the funding. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was funded by Inserm and Centre Oscar Lambret.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.802177/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Material 1 | TCGA database of mutations and CNV alterations in early and advanced breast cancers.

Supplementary Material 2 | BC360 panel gene list

Supplementary Material 3 | CDx panel gene list

Supplementary Material 4 | MALDI MSI of 52 cases of primary tumors showing the spatial proteomic heterogeneity of the tumors. In each sample vignette, the MALDI MS imaging is displayed with the histological HPS picture (upper left), the principal component analysis of the proteomic clones (upper right), the segmentation tree (middle right), and the spectra of the clones (bottom right).

Supplementary Material 5 | MALDI MSI of 24 cases of metastases showing the spatial proteomic heterogeneity of the tumors. In each sample vignette, the MALDI MS imaging is displayed with the histological HPS picture (upper left), the principal component analysis of the proteomic clones (upper right), the segmentation tree (middle right), and the spectra of the clones (bottom right).

Supplementary Material 6 | Number of total proteins identified according to (A) tissue types (bone n=3; liver n=5; nodes n=6; skin n=10) or (B) to the sampling method (B), i.e. surgery (n=52), surgical biopsy (n=9) or fine needle core biopsy (n=15). Line in the middle of the box is the median, the upper and lower sides of the box represent the 75th and 25th percentiles respectively, and the outside lines are the extremes.

Supplementary Material 7 | Panther analysis of the clonal proteome landscape showing (A) the protein class distribution (in %), and (B) a comparison of the distribution between primary tumors and stroma (relative difference in % in blue) and between primary tumors and metastases (relative difference in % in red).

Supplementary Material 8 | Reference gene distribution across the four datasets (clonal proteome, TCGA, BC360, CDx).

Supplementary Material 9 | Targets interacting with anticancer drugs across the four datasets (clonal proteome, TCGA, BC360, CDx).

Supplementary Material 10 | String networks in stroma (cluster 1) and in primary tumors and metastases (cluster 2).

Supplementary Table 1 | Information concerning patients and type of tumors identified by the pathologist.

Supplementary Table 2 | References cited in Table 2 and Figure 8D.

ABC, advanced breast cancer; ACN, acetonitrile; AGC, automatic gain control; AltProt, alternative proteins; Amu, atomic mass unit; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical; BC, breast cancer; Da, Dalton; DMFS, distant metastases free survival; EBC, early breast cancer; EMA, European medicines agency; FDA, food and drug administration; FDR, false discovery rate; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; HCCA, hydroxycinnamic acid; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; HR, hazard ratio; HUGO, human genome organization; ID, identification; IDG, illuminating the druggable genome; IDG-KMC, illuminating the druggable genome knowledge management center; ITO, indium tin oxide; LC, liquid chromatography; LESA, liquid extraction surface analysis; LFQ, label-free quantification; MALDI, matrix assisted laser desorption ionization; MeOH, methanol; Meta metastases; MS mass spectrometry; MSI mass spectrometry imaging; OS, overall survival; PMDA, pharmaceuticals and medical devices agency; PSM, peptide spectrum matches; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TDL, target development level; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; TIC, total ion count.

1. Yates LR, Gerstung M, Knappskog S, Desmedt C, Gundem G, Van Loo P, et al. Subclonal Diversification of Primary Breast Cancer Revealed by Multiregion Sequencing. Nat Med (2015) 21:751–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.3886

2. Garraway LA, Jänne PA. Circumventing Cancer Drug Resistance in the Era of Personalized Medicine. Cancer Discov (2012) 2:214–26. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0012

3. McDonald K-A, Kawaguchi T, Qi Q, Peng X, Asaoka M, Young J, et al. Tumor Heterogeneity Correlates With Less Immune Response and Worse Survival in Breast Cancer Patients. Ann Surg Oncol (2019) 26:2191–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07338-3

4. Pereira B, Chin S-F, Rueda OM, Vollan H-KM, Provenzano E, Bardwell HA, et al. The Somatic Mutation Profiles of 2,433 Breast Cancers Refines Their Genomic and Transcriptomic Landscapes. Nat Commun (2016) 7:11479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11479

5. Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal Evolution in Cancer. Nature (2012) 481:306–13. doi: 10.1038/nature10762

6. Williams MJ, Sottoriva A, Graham TA. Measuring Clonal Evolution in Cancer With Genomics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet (2019) 20:309–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021712

7. Pogrebniak KL, Curtis C. Harnessing Tumor Evolution to Circumvent Resistance. Trends Genet (2018) 34:639–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2018.05.007

8. Marine J-C, Dawson S-J, Dawson MA. Non-Genetic Mechanisms of Therapeutic Resistance in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2020) 20:743–56. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-00302-4

9. Gyanchandani R, Lin Y, Lin H-M, Cooper K, Normolle DP, Brufsky A, et al. Intratumor Heterogeneity Affects Gene Expression Profile Test Prognostic Risk Stratification in Early Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2016) 22:5362–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2889

10. Hennessy BT, Lu Y, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Carey MS, Myhre S, Ju Z, et al. A Technical Assessment of the Utility of Reverse Phase Protein Arrays for the Study of the Functional Proteome in Non-Microdissected Human Breast Cancers. Clin Proteomics (2010) 6:129–51. doi: 10.1007/s12014-010-9055-y

11. Kim J, DeBerardinis RJ. Mechanisms and Implications of Metabolic Heterogeneity in Cancer. Cell Metab (2019) 30:434–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.013

12. Jackson HW, Fischer JR, Zanotelli VRT, Ali HR, Mechera R, Soysal SD, et al. The Single-Cell Pathology Landscape of Breast Cancer. Nature (2020) 578:615–20. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1876-x

13. Ståhl PL, Salmén F, Vickovic S, Lundmark A, Navarro JF, Magnusson J, et al. Visualization and Analysis of Gene Expression in Tissue Sections by Spatial Transcriptomics. Science (2016) 353:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2403

14. Xia C, Fan J, Emanuel G, Hao J, Zhuang X. Spatial Transcriptome Profiling by MERFISH Reveals Subcellular RNA Compartmentalization and Cell Cycle-Dependent Gene Expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116:19490–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912459116

15. Lee JH, Daugharthy ER, Scheiman J, Kalhor R, Ferrante TC, Terry R, et al. Fluorescent in Situ Sequencing (FISSEQ) of RNA for Gene Expression Profiling in Intact Cells and Tissues. Nat Protoc (2015) 10:442–58. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.191

16. Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on Mrna Abundance. Cell (2016) 165:535–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014

17. Gout J-F, Li W, Fritsch C, Li A, Haroon S, Singh L, et al. The Landscape of Transcription Errors in Eukaryotic Cells. Sci Adv (2017) 3:e1701484. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701484

18. Rapino F, Delaunay S, Rambow F, Zhou Z, Tharun L, De Tullio P, et al. Codon-Specific Translation Reprogramming Promotes Resistance to Targeted Therapy. Nature (2018) 558:605–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0243-7

19. García-Jiménez C, Goding CR. Starvation and Pseudo-Starvation as Drivers of Cancer Metastasis Through Translation Reprogramming. Cell Metab (2019) 29:254–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.11.018

20. Jewer M, Lee L, Leibovitch M, Zhang G, Liu J, Findlay SD, et al. Translational Control of Breast Cancer Plasticity. Nat Commun (2020) 11:2498. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16352-z

21. Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, et al. Analysis of 100,000 Human Cancer Genomes Reveals the Landscape of Tumor Mutational Burden. Genome Med (2017) 9:34. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2

22. Santos R, Ursu O, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Donadi RS, Bologa CG, et al. A Comprehensive Map of Molecular Drug Targets. Nat Rev Drug Discovery (2017) 16:19–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.230

23. Giesen C, Wang HAO, Schapiro D, Zivanovic N, Jacobs A, Hattendorf B, et al. Highly Multiplexed Imaging of Tumor Tissues With Subcellular Resolution by Mass Cytometry. Nat Methods (2014) 11:417–22. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2869

24. Schulz D, Zanotelli VRT, Fischer JR, Schapiro D, Engler S, Lun X-K, et al. Simultaneous Multiplexed Imaging of Mrna and Proteins With Subcellular Resolution in Breast Cancer Tissue Samples by Mass Cytometry. Cell Syst (2018) 6:25–36.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.12.001

25. Beechem JM. High-Plex Spatially Resolved RNA and Protein Detection Using Digital Spatial Profiling: A Technology Designed for Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Discovery and Translational Research. Methods Mol Biol (2020) 2055:563–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9773-2_25

26. Fournier I, Wisztorski M, Salzet M. Tissue Imaging Using MALDI-MS: A New Frontier of Histopathology Proteomics. Expert Rev Proteomics (2008) 5:413–24. doi: 10.1586/14789450.5.3.413

27. Lemaire R, Tabet JC, Ducoroy P, Hendra JB, Salzet M, Fournier I. Solid Ionic Matrixes for Direct Tissue Analysis and MALDI Imaging. Anal Chem (2006) 78:809–19. doi: 10.1021/ac0514669

28. Lemaire R, Menguellet SA, Stauber J, Marchaudon V, Lucot J-P, Collinet P, et al. Specific MALDI Imaging and Profiling for Biomarker Hunting and Validation: Fragment of the 11S Proteasome Activator Complex, Reg Alpha Fragment, is a New Potential Ovary Cancer Biomarker. J Proteome Res (2007) 6:4127–34. doi: 10.1021/pr0702722

29. Delcourt V, Franck J, Leblanc E, Narducci F, Robin Y-M, Gimeno J-P, et al. Combined Mass Spectrometry Imaging and Top-Down Microproteomics Reveals Evidence of a Hidden Proteome in Ovarian Cancer. EBioMedicine (2017) 21:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.06.001

30. Le Rhun E, Duhamel M, Wisztorski M, Gimeno J-P, Zairi F, Escande F, et al. Evaluation of non-Supervised MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging Combined With Microproteomics for Glioma Grade III Classification. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom (2017) 1865:875–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.11.012

31. Quanico J, Franck J, Cardon T, Leblanc E, Wisztorski M, Salzet M, et al. Nanolc-MS Coupling of Liquid Microjunction Microextraction for on-Tissue Proteomic Analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom (2017) 1865:891–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.11.002

32. Fournier I, Day R, Salzet M. Direct Analysis of Neuropeptides by in Situ MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry in the Rat Brain. Neuro Endocrinol Lett (2003) 24:9–14.

33. Lemaire R, Desmons A, Tabet JC, Day R, Salzet M, Fournier I. Direct Analysis and MALDI Imaging of Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissue Sections. J Proteome Res (2007) 6:1295–305. doi: 10.1021/pr060549i

34. Wisztorski M, Lemaire R, Stauber J, Menguelet SA, Croix D, Mathé OJ, et al. New Developments in MALDI Imaging for Pathology Proteomic Studies. Curr Pharm Des (2007) 13:3317–24. doi: 10.2174/138161207782360672

35. Klein O, Strohschein K, Nebrich G, Oetjen J, Trede D, Thiele H, et al. MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry: Discrimination of Pathophysiological Regions in Traumatized Skeletal Muscle by Characteristic Peptide Signatures. Proteomics (2014) 14:2249–60. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400088

36. Trede D, Kobarg JH, Oetjen J, Thiele H, Maass P, Alexandrov T. On the Importance of Mathematical Methods for Analysis of MALDI-Imaging Mass Spectrometry Data. J Integr Bioinform (2012) 9:189. doi: 10.1515/jib-2012-189

37. Alexandrov T, Becker M, Deininger S-O, Ernst G, Wehder L, Grasmair M, et al. Spatial Segmentation of Imaging Mass Spectrometry Data With Edge-Preserving Image Denoising and Clustering. J Proteome Res (2010) 9:6535–46. doi: 10.1021/pr100734z

38. Quanico J, Franck J, Dauly C, Strupat K, Dupuy J, Day R, et al. Development of Liquid Microjunction Extraction Strategy for Improving Protein Identification From Tissue Sections. J Proteomics (2013) 79:200–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.11.025

39. Cox J, Mann M. Maxquant Enables High Peptide Identification Rates, Individualized P.P.B.-Range Mass Accuracies and Proteome-Wide Protein Quantification. Nat Biotechnol (2008) 26:1367–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511

40. Tyanova S, Temu T, Carlson A, Sinitcyn P, Mann M, Cox J. Visualization of LC-MS/MS Proteomics Data in Maxquant. Proteomics (2015) 15:1453–6. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400449

41. Cox J, Neuhauser N, Michalski A, Scheltema RA, Olsen JV, Mann M. Andromeda: A Peptide Search Engine Integrated Into the Maxquant Environment. J Proteome Res (2011) 10:1794–805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j

42. Cox J, Hein MY, Luber CA, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Accurate Proteome-Wide Label-Free Quantification by Delayed Normalization and Maximal Peptide Ratio Extraction, Termed Maxlfq. Mol Cell Proteomics (2014) 13:2513–26. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031591

43. Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, et al. The STRING Database in 2011: Functional Interaction Networks of Proteins, Globally Integrated and Scored. Nucleic Acids Res (2011) 39:D561–568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973

44. Vizcaíno JA, Deutsch EW, Wang R, Csordas A, Reisinger F, Ríos D, et al. Proteomexchange Provides Globally Coordinated Proteomics Data Submission and Dissemination. Nat Biotechnol (2014) 32:223–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2839

45. Bonnet A, Lagarrigue S, Liaubet L, Robert-Granié C, Sancristobal M, Tosser-Klopp G. Pathway Results From the Chicken Data Set Using GOTM, Pathway Studio and Ingenuity Softwares. BMC Proc (2009) 3 Suppl 4:S11. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-S4-S11

46. Yuryev A, Kotelnikova E, Daraselia N. Ariadne’s Chemeffect and Pathway Studio Knowledge Base. Expert Opin Drug Discov (2009) 4:1307–18. doi: 10.1517/17460440903413488

47. Heberle H, Meirelles GV, da Silva FR, Telles GP, Minghim R. Interactivenn: A Web-Based Tool for the Analysis of Sets Through Venn Diagrams. BMC Bioinf (2015) 16:169. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3

48. Mi H, Muruganujan A, Huang X, Ebert D, Mills C, Guo X, et al. Protocol Update for Large-Scale Genome and Gene Function Analysis With the PANTHER Classification System (V.14.0). Nat Protoc (2019) 14:703–21. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0128-8

49. Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. Cluego: A Cytoscape Plug-in to Decipher Functionally Grouped Gene Ontology and Pathway Annotation Networks. Bioinformatics (2009) 25:1091–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101

50. Flores MA, Lazar IM. Xman V2-a Database of Homo Sapiens Mutated Peptides. Bioinformatics (2020) 36:1311–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz693

51. Cardon T, Salzet M, Franck J, Fournier I. Nuclei of Hela Cells Interactomes Unravel a Network of Ghost Proteins Involved in Proteins Translation. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj (2019) 1863:1458–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.05.009

52. Sheils T, Mathias SL, Siramshetty VB, Bocci G, Bologa CG, Yang JJ, et al. How to Illuminate the Druggable Genome Using Pharos. Curr Protoc Bioinf (2020) 69:e92. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.92

53. Györffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, et al. An Online Survival Analysis Tool to Rapidly Assess the Effect of 22,277 Genes on Breast Cancer Prognosis Using Microarray Data of 1,809 Patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2010) 123:725–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9

54. Schug ZT, Peck B, Jones DT, Zhang Q, Grosskurth S, Alam IS, et al. Acetyl-Coa Synthetase 2 Promotes Acetate Utilization and Maintains Cancer Cell Growth Under Metabolic Stress. Cancer Cell (2015) 27:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.002

55. Yu L, Li K, Xu Z, Cui G, Zhang X. Integrated Omics and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies the Loss of Metabolite-Metabolite Correlations in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Onco Targets Ther (2018) 11:3919–29. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S166149

56. Vaughan RA, Gannon NP, Garcia-Smith R, Licon-Munoz Y, Barberena MA, Bisoffi M, et al. β-Alanine Suppresses Malignant Breast Epithelial Cell Aggressiveness Through Alterations in Metabolism and Cellular Acidity In Vitro. Mol Cancer (2014) 13:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-14

57. Stewart A, Maity B, Fisher RA. Two for the Price of One: G Protein-Dependent and -Independent Functions of RGS6 In Vivo. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci (2015) 133:123–51. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.03.001

58. Parczyk K, Schneider MR. The Future of Antihormone Therapy: Innovations Based on an Established Principle. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (1996) 122:383–96. doi: 10.1007/BF01212877

59. Geck RC, Toker A. Nonessential Amino Acid Metabolism in Breast Cancer. Adv Biol Regul (2016) 62:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2016.01.001

60. Pickup KE, Pardow F, Carbonell-Caballero J, Lioutas A, Villanueva-Cañas JL, Wright RHG, et al. Expression of Oncogenic Drivers in 3D Cell Culture Depends on Nuclear ATP Synthesis by NUDT5. Cancers (Basel) (2019) 11. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091337

61. Ehmsen S, Pedersen MH, Wang G, Terp MG, Arslanagic A, Hood BL, et al. Increased Cholesterol Biosynthesis is a Key Characteristic of Breast Cancer Stem Cells Influencing Patient Outcome. Cell Rep (2019) 27:3927–3938.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.104

62. Cai D, Wang J, Gao B, Li J, Wu F, Zou JX, et al. Rorγ is a Targetable Master Regulator of Cholesterol Biosynthesis in a Cancer Subtype. Nat Commun (2019) 10:4621. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12529-3

63. Simigdala N, Gao Q, Pancholi S, Roberg-Larsen H, Zvelebil M, Ribas R, et al. Cholesterol Biosynthesis Pathway as a Novel Mechanism of Resistance to Estrogen Deprivation in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res (2016) 18:58. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0713-5

64. Brown KK, Spinelli JB, Asara JM, Toker A. Adaptive Reprogramming of De Novo Pyrimidine Synthesis is a Metabolic Vulnerability in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Discovery (2017) 7:391–9. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0611

65. Opolski A, Mazurkiewicz M, Wietrzyk J, Kleinrok Z, Radzikowski C. The Role of GABA-Ergic System in Human Mammary Gland Pathology and in Growth of Transplantable Murine Mammary Cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2000) 19:383–90.

66. Shkurnikov MY, Nechaev IN, Khaustova NA, Krainova NA, Savelov NA, Grinevich VN, et al. Expression Profile of Inflammatory Breast Cancer. Bull Exp Biol Med (2013) 155:667–72. doi: 10.1007/s10517-013-2221-2

67. Lampa M, Arlt H, He T, Ospina B, Reeves J, Zhang B, et al. Glutaminase is Essential for the Growth of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells With a Deregulated Glutamine Metabolism Pathway and its Suppression Synergizes With Mtor Inhibition. PloS One (2017) 12:e0185092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185092

68. Kim D-H, Yoon H-J, Cha Y-N, Surh Y-J. Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 and its Reaction Product, Carbon Monoxide, in Manifestation of Breast Cancer Stem Cell-Like Properties: Notch-1 as a Putative Target. Free Radic Res (2018) 52:1336–47. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2018.1473571

69. Ifergan I, Assaraf YG. Molecular Mechanisms of Adaptation to Folate Deficiency. Vitam Horm (2008) 79:99–143. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(08)00404-4

70. Efimova EV, Takahashi S, Shamsi NA, Wu D, Labay E, Ulanovskaya OA, et al. Linking Cancer Metabolism to DNA Repair and Accelerated Senescence. Mol Cancer Res (2016) 14:173–84. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0263

71. Ferrer CM, Lynch TP, Sodi VL, Falcone JN, Schwab LP, Peacock DL, et al. O-Glcnacylation Regulates Cancer Metabolism and Survival Stress Signaling via Regulation of the HIF-1 Pathway. Mol Cell (2014) 54:820–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.026

72. Ferrer CM, Sodi VL, Reginato MJ. O-Glcnacylation in Cancer Biology: Linking Metabolism and Signaling. J Mol Biol (2016) 428:3282–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.05.028

73. Chiaradonna F, Ricciardiello F, Palorini R. The Nutrient-Sensing Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway as the Hub of Cancer Metabolic Rewiring. Cells (2018) 7. doi: 10.3390/cells7060053

74. Ma Z, Vosseller K. Cancer Metabolism and Elevated O-Glcnac in Oncogenic Signaling. J Biol Chem (2014) 289:34457–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.577718

75. Nie H, Yi W. O-Glcnacylation, a Sweet Link to the Pathology of Diseases. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B (2019) 20:437–48. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1900150

76. Very N, Vercoutter-Edouart A-S, Lefebvre T, Hardivillé S, El Yazidi-Belkoura I. Cross-Dysregulation of O-Glcnacylation and PI3K/AKT/Mtor Axis in Human Chronic Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2018) 9:602. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00602

77. Makwana V, Ryan P, Patel B, Dukie S-A, Rudrawar S. Essential Role of O-Glcnacylation in Stabilization of Oncogenic Factors. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj (2019) 1863:1302–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.04.002

78. Singh A, Nunes JJ, Ateeq B. Role and Therapeutic Potential of G-Protein Coupled Receptors in Breast Cancer Progression and Metastases. Eur J Pharmacol (2015) 763:178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.011

79. Geck RC, Foley JR, Murray Stewart T, Asara JM, Casero RA, Toker A. Inhibition of the Polyamine Synthesis Enzyme Ornithine Decarboxylase Sensitizes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to Cytotoxic Chemotherapy. J Biol Chem (2020) 295:6263–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.012376

80. Barupal DK, Gao B, Budczies J, Phinney BS, Perroud B, Denkert C, et al. Prioritization of Metabolic Genes as Novel Therapeutic Targets in Estrogen-Receptor Negative Breast Tumors Using Multi-Omics Data and Text Mining. Oncotarget (2019) 10:3894–909. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26995

81. Wang Y-P, Lei Q-Y. Perspectives of Reprogramming Breast Cancer Metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol (2017) 1026:217–32. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-6020-5_10

82. Kim H-Y, Lee K-M, Kim S-H, Kwon Y-J, Chun Y-J, Choi H-K. Comparative Metabolic and Lipidomic Profiling of Human Breast Cancer Cells With Different Metastatic Potentials. Oncotarget (2016) 7:67111–28. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11560

83. Strekalova E, Malin D, Weisenhorn EMM, Russell JD, Hoelper D, Jain A, et al. S-Adenosylmethionine Biosynthesis is a Targetable Metabolic Vulnerability of Cancer Stem Cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2019) 175:39–50. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05146-7

84. Surguchov A. Intracellular Dynamics of Synucleins: ‘Here, There and Everywhere’. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol (2015) 320:103–69. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.07.007

85. Wang X, Wan J, Xu Z, Jiang S, Ji L, Liu Y, et al. Identification of Competitive Endogenous Rnas Network in Breast Cancer. Cancer Med (2019) 8:2392–403. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2099

86. Fan Y, Zhou X, Xia T-S, Chen Z, Li J, Liu Q, et al. Human Plasma Metabolomics for Identifying Differential Metabolites and Predicting Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer. Oncotarget (2016) 7:9925–38. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7155

87. Marquart J, Chen EY, Prasad V. Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients With Cancer Who Benefit From Genome-Driven Oncology. JAMA Oncol (2018) 4:1093–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1660

88. Beltran H, Eng K, Mosquera JM, Sigaras A, Romanel A, Rennert H, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing of Metastatic Cancer and Biomarkers of Treatment Response. JAMA Oncol (2015) 1:466–74.

89. Patel MN, Halling-Brown MD, Tym JE, Workman P, Al-Lazikani B. Objective Assessment of Cancer Genes for Drug Discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2013) 12:35–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd3913

90. Cardon T, Franck J, Coyaud E, Laurent EMN, Damato M, Maffia M, et al. Alternative Proteins are Functional Regulators in Cell Reprogramming by PKA Activation. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48:7864–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa277

91. Sicklick JK, Kato S, Okamura R, Schwaederle M, Hahn ME, Williams CB, et al. Molecular Profiling of Cancer Patients Enables Personalized Combination Therapy: The I-PREDICT Study. Nat Med (2019) 25:744–50. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0407-5

92. Al-Lazikani B, Banerji U, Workman P. Combinatorial Drug Therapy for Cancer in the Post-Genomic Era. Nat Biotechnol (2012) 30:679–92. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2284

93. Würth R, Thellung S, Bajetto A, Mazzanti M, Florio T, Barbieri F. Drug-Repositioning Opportunities for Cancer Therapy: Novel Molecular Targets for Known Compounds. Drug Discov Today (2016) 21:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.09.017

94. Griffiths JI, Cohen AL, Jones V, Salgia R, Chang JT, Bild AH. Opportunities for Improving Cancer Treatment Using Systems Biology. Curr Opin Syst Biol (2019) 17:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coisb.2019.10.018

Keywords: functional tumor heterogeneity, spatially resolved MALDI mass spectrometry imaging, microproteomics, spatially resolved proteome, luminal breast cancers, clonal theranostics, mutated and alternative proteomes, drug repurposing and drug target discovery

Citation: Hajjaji N, Aboulouard S, Cardon T, Bertin D, Robin Y-M, Fournier I and Salzet M (2022) Path to Clonal Theranostics in Luminal Breast Cancers. Front. Oncol. 11:802177. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.802177

Received: 26 October 2021; Accepted: 06 December 2021;

Published: 13 January 2022.

Edited by:

San-Gang Wu, First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yong-Yu Liu, University of Louisiana at Monroe, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Hajjaji, Aboulouard, Cardon, Bertin, Robin, Fournier and Salzet. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nawale Hajjaji, bi1oYWpqYWppQG8tbGFtYnJldC5mcg==; Isabelle Fournier, aXNhYmVsbGUuZm91cm5pZXJAdW5pdi1saWxsZS5mcg==; Michel Salzet, bWljaGVsLnNhbHpldEB1bml2LWxpbGxlLmZy

†Lead contact: Nawale Hajjaji,bi1oYWpqYWppQG8tbGFtYnJldC5mcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.