- 1Department of Hematology, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China

- 2Department of Hepatological Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China

Introduction: Several maintenance therapies are available for treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The objective of this review was to assess the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide monotherapy in these patients.

Methods: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library databases were searched for publications up to April 7, 2021. Original studies that had information on lenalidomide monotherapy for DLBCL patients with R/R status were included. Meta-analyses of response rates, adverse events (AEs), overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS) were performed. The pooled event rates were calculated using a double arcsine transformation to stabilize the variances of the original proportions. Subgroup analysis was used to compare patients with different germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) phenotypes.

Results: We included 11 publications that examined DLBCL patients with R/R status. These studies were published from 2008 to 2020. The cumulative objective response rate (ORR) for lenalidomide monotherapy was 0.33 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.40), and the ORR was better in patients with the non-GCB phenotype (0.50; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.74) than the GCB phenotype (0.06; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.11). The major serious treatment-related AEs were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, respiratory disorders, anemia, and diarrhea. The median PFS ranged from 2.6 to 34 months and the median OS ranged from 7.8 to 37 months.

Conclusion: This study provides evidence that lenalidomide monotherapy was active and tolerable in DLBCL patients with R/R status. Patients in the non-GCB subgroup had better responsiveness.

Introduction

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and accounts for about 40% of all diagnosed lymphomas (1). The current standard first-line treatment of DLBCL is immunochemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone, a regimen that provides complete and sustained remission for about 75% of newly diagnosed patients (2). The remaining patients are classified as having “relapsed” DLBCL if there is any new lesion after complete response (CR), and as “refractory” DLBCL if 50% or more of the lesions increased in size following initial treatment or if there is appearance of a new lesion during or following the initial treatment (3).

For DLBCL patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) disease, the standard therapeutic option for those who are chemosensitive to second-line regimens is high-dose therapy plus autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) (4). Patients who are ineligible for ASCT or who fail after second-line treatment typically have poor prognoses. However, recent findings indicated that these patients may benefit from alternative salvage therapies. For example, lenalidomide with tafasitmab is often an effective treatment for DLBCL patients with R/R status.

Lenalidomide is a second−generation immunomodulatory drug, and several clinical trials reported that it provided effective treatment of multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and mantle cell lymphoma (5, 6). Other trials showed that lenalidomide monotherapy was an active and safe treatment for DLBCL patients with R/R status (7, 8). However, there has been no systematic synthesis of available studies on this topic.

The objective of the present study was to assess the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide monotherapy for DLBCL patients with R/R status and provide useful guidance for the treatment of these patients in clinical settings.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

The present systematic review and meta-analysis followed the PRISMA statement (9, 10) and used searches from Embase, Medline, and the Cochrane library to identify articles published up to April 7, 2021 (Figure 1). The search terms included “lenalidomide”, “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma”, and “lymphoma”, and appropriate search strategies and syntax were used for each database (Appendix I).

Selection Criteria and Study Selection

The criteria for inclusion/exclusion were as follows: (i) studies were included if they were original randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, prospective one-arm studies, or observational studies, but excluded if they were letters, commentaries, conference abstracts, case reports, case series, preclinical trials, review articles, or meta-analyses; (ii) studies were included if they examined populations of DLBCL patients with R/R status; (iii) studies were included if they provided information on lenalidomide monotherapy; and (iv) studies were included if they provided information on the outcomes of response rate, safety events, and survival [overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS)].

The titles and abstracts were first independently screened by two authors (Ou Bai and Jia Li) to identify potentially eligible publications. Then, full-text screening was independently performed by Wei Guo and Jia Li. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by referral to a third party.

Data Collection

Jia Li, Xingtong Wang, and Yangzhi Zhao performed the data collection independently and resolved disagreements by discussion or referral to a third party. The basic information of the included studies was study design; publication year; patient demographics; and data on response rates, safety events, and survival (OS and PFS). Responses were determined using the Cheson criteria, and included ORR, CR, partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) (3). PFS was defined as the time from the onset of lenalidomide monotherapy until PD (defined by RECIST criteria ver. 1.1) (11). OS time was defined as the time from the onset of lenalidomide monotherapy until death. Adverse events were reported and graded according to CTCAE ver. 5.0 (12).

Data Analysis

Because the target was the efficacy and safety of the one-arm intervention, not a comparison of groups, the risk of bias assessment was performed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (13). Meta-analyses of response rates, safety events, and survival rates (OS and PFS) were performed. Sensitivity analyses were not performed due to the limited amount of data. The pooled event rates were calculated using a double arcsine transformation to stabilize the variances of the original proportions. Each pooled rate is presented as proportion with a 95% confidential interval (CI). Heterogeneity was estimated using the Q-test. When the P-value was less than 0.1 (Q-test) and the I2 was greater than 50%, the result was considered heterogeneous, and a random-effects model was used for analysis; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Subgroup analysis was performed to examine patients with germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) phenotype and non-GCB phenotype. A P-value below 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corp. Texas, USA).

Results

Basic Characteristics of Studies

Our initial screening led to the identification of 1237 potentially eligible studies (1231 from PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library, and 6 from other sources). We ultimately excluded 1226 of these studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and included 11 publications from 10 studies from that were published from 2008 to 2020 (Figure 1 and Table 1) (7, 8, 14–22). Five of these studies were prospective one-arm studies (7, 8, 15, 16, 20, 21), four were retrospective analyses (14, 17, 18, 22), and one was a randomized controlled trial (19). The sample size ranged from 15 to 153 patients, and the median patient age ranged from 51 to 79 years old. Based on the ROBINS-I tool, the included studies had variable quality (Table 2). Moreover, because these data were from one-arm interventions, each study had a high risk of confounding. We also classified six studies as having problems with selection bias. The one RCT, in which our extracted data were targeted as a one-arm treatment, also had a high risk of confounding.

Response Rates and Adverse Events

All publications reported ORRs, and the pooled results had an ORR of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.40, I2 = 59.55%; Figure 2A). Among all 600 patients, 197 achieved at least PR. The cumulative CR (which included confirmed and unconfirmed CR) was 0.16 (95% CI: 0.11, 0.21, I2 = 56.40%; Figure 2B). PD was present in about half the patients, and the cumulative PD was 0.46 (95% CI: 0.39, 0.54, I2 = 63.18%; Figure 2C). We also determined several other responses (Table 3). Notably, the median response duration ranged from 4.1 months to 18.5 months (Table 4).

Figure 2 (A) Forest plot of the overall response rates of patients who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy. (B) Forest plot of the complete response rates of patients who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy. (C) Forest plot of progressive disease rates of patients who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy.

Table 3 Pooled response rates and five major adverse events (≥Grade 3) in patients who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy.

Table 4 Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy.

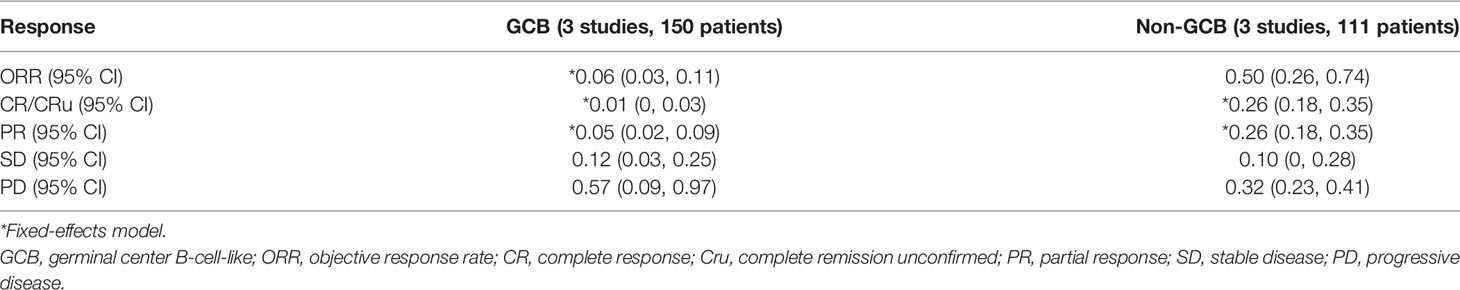

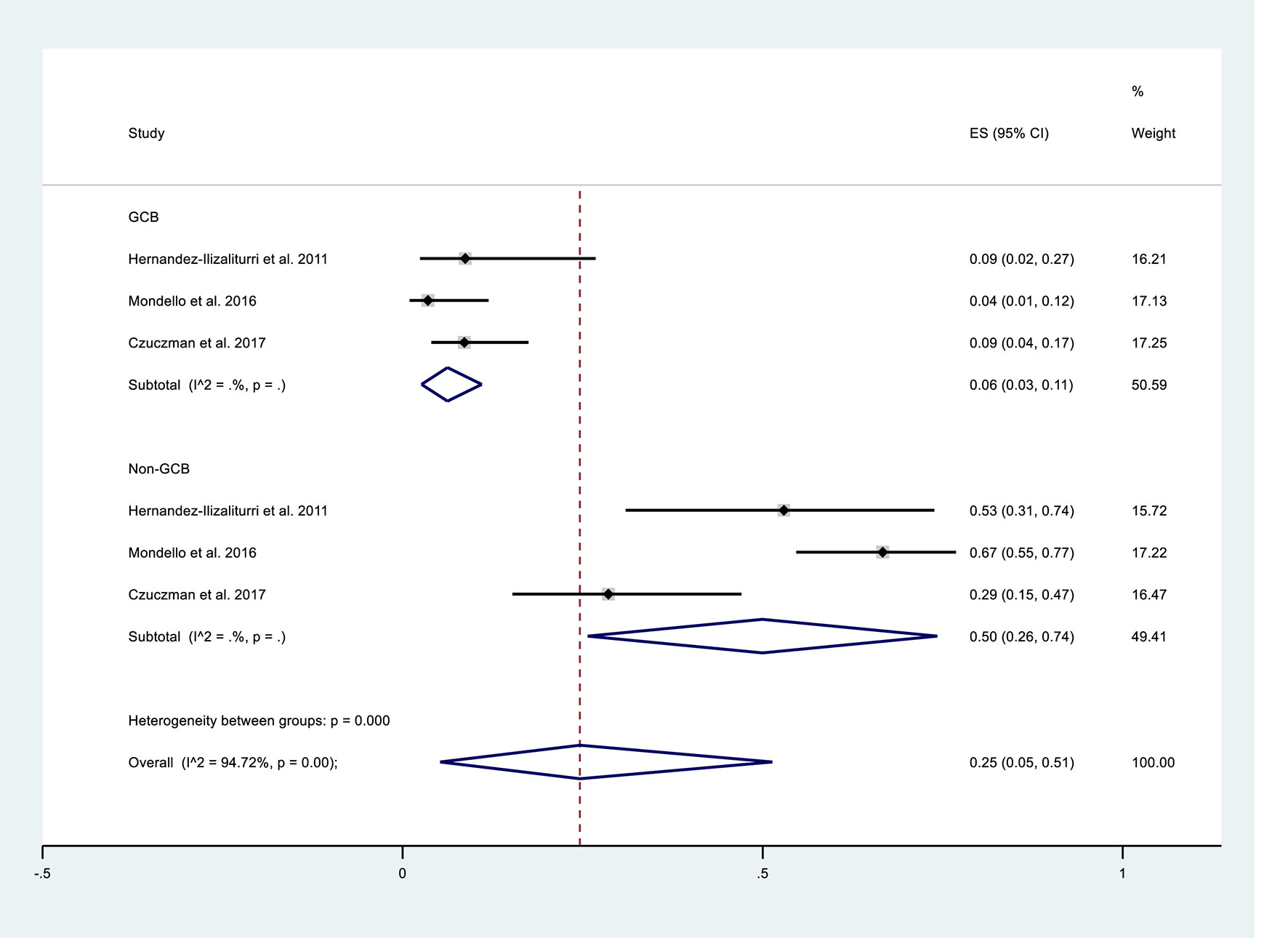

We performed subgroup analysis to compare the responses of patients with the GCB and non-GCB phenotypes (Table 5, Figure 3). The results indicated that patients with non-GCB status had a greater ORR (0.50; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.74) than those with GCB status (0.06; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.11). The non-GCB group also had significantly better CR and PR (both P < 0.05).

Table 5 Pooled response rates in patients with GCB and non-GCB phenotypes who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy.

Figure 3 Subgroup analysis of overall response rates of patients with germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) phenotype or non-GCB phenotype who received maintenance treatment consisting of lenalidomide monotherapy.

The most serious treatment-related adverse events (AEs; Grade 3 or more) were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, respiratory disorder, anemia, and diarrhea, and their mean cumulative incidences ranged from 2% to 28% (Table 3).

Survival Data

Eight studies reported survival data. The median PFS ranged from 2.6 to 34 months and the median OS ranged from 7.8 to 37 months (Table 4). The study by Mondello et al. (18) reported distinctly better survival rates than the other studies. Further analysis indicated the Mondello et al. study examined patients who were less likely to be high-risk (34%), received fewer early treatment lines (mean: 1), and had longer median response times to the first treatment (median: 23 months).

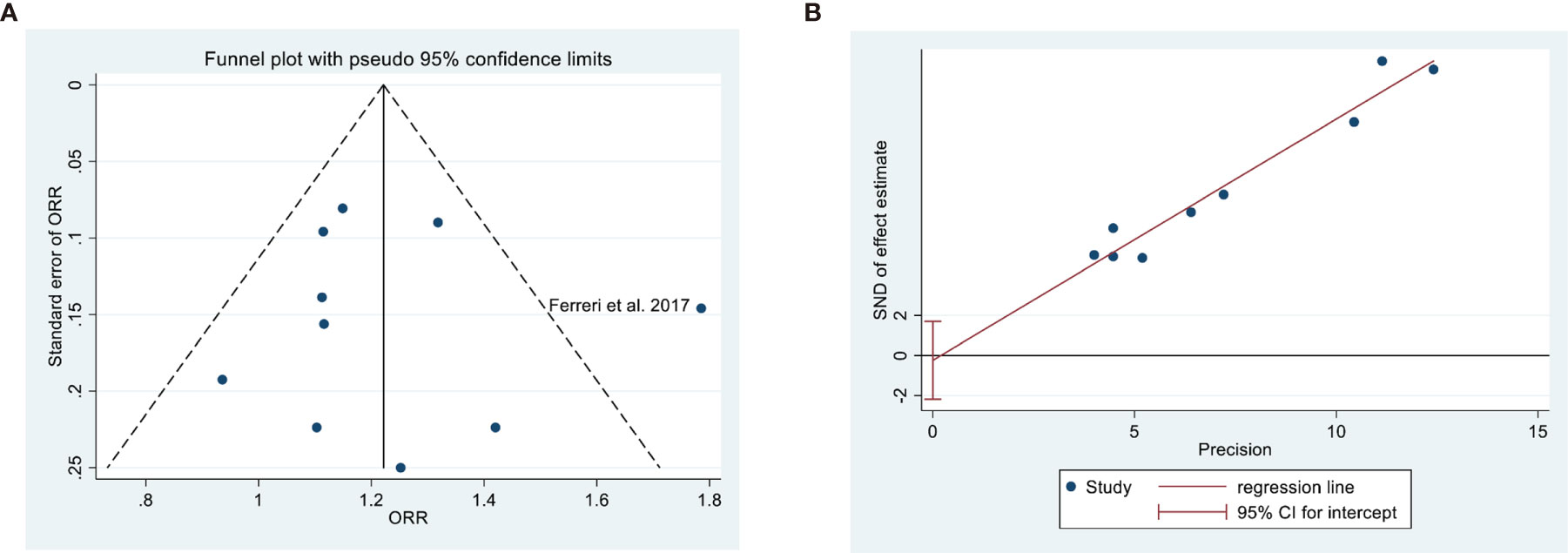

Publication Bias

Analysis of publication bias indicated no evidence of this bias based on a symmetric funnel plot and the results of the Egger’s test (P = 0.778; Figure 4).

Figure 4 Assessment of publication bias in overall response rate based on a funnel plot (A) and Egger’s test (B, P = 0.778).

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of 10 studies that examined the effect of lenalidomide monotherapy for DLBCL patients with R/R status indicated the ORR was 0.33 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.40). Moreover, patients with the non-GCB phenotype had a greater ORR (0.50; 95% CI: 0.26-0.74) than those with the GCB phenotype (0.06; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.11). The major serious treatment-related AEs in these patients were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, respiratory disorder, anemia, and diarrhea. The median PFS ranged from 2.6 to 34 months and the median OS ranged from 7.8 to 37 months.

The introduction of lenalidomide treatment for DLBCL patients who have R/R status provides an opportunity for them to overcome chemorefractoriness (5). The anti-cancer effects of lenalidomide are due to its stimulation of cereblon, a component of E3 ubiquitin-ligase, and restoration of the function of immune effector cells (23). Our meta-analysis indicated the cumulative ORR (0.33; 95% CI 0.26, 0.40) was similar to that achieved by obinutuzumab monotherapy (0.32) (24) and tafasitamab monotherapy (ORR: 0.26–0.29) (25). Furthermore, trials have shown that combining lenalidomide and tafasitamab had higher efficacy than the single drug each, which indicated the synergistic effect between the two drugs (26, 27). Because lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent, clinicians have used it for maintenance therapy and in various induction and salvage regimens (28). However, the evidence of a benefit of lenalidomide for DLBCL patients with R/R status is still limited. Some trials (e.g., NCT03730740) are now examining the efficiency of lenalidomide monotherapy as maintenance treatment for R/R non-Hodgkin T-cell lymphoma.

The GCB and non-GCB phenotypes of DLBCL have significant differences in prognosis (29, 30), and these phenotype have approximately the same prevalence among DLBCL patients (31). Although there are several moderating factors, patients with the non-GCB phenotype have better prognosis (32). In agreement, our meta-analysis indicated the ORR, CR, and PR of the non-GCB subgroup were significantly better (all P < 0.05). This may be related to the effect of lenalidomide on the transcription regulatory factor IRF4/MUM1 and its inhibition of the nuclear factor-kB pathway (33, 34). Further large-scale trials are needed to confirm these findings.

Previous studies reported the AEs of lenalidomide monotherapy were generally manageable (5). The most frequent serious AE in our 10 included studies was neutropenia (0.28; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.37). One study that compared placebo with lenalidomide reported a greater risk of neutropenia in the lenalidomide group (RR: 4.74; 95% CI: 2.96, 7.57) (35). Therefore, in routine clinical practice, prevention and appropriate management of neutropenia are important when administering lenalidomide monotherapy.

Because of the limited data in the available studies, we were unable to assess survival rates. However, Mondello et al. reported better survival rates than the other studies due to their methods of patient selection. In particular, they included fewer patients with high-risk (34%), patients who received fewer early treatment lines (mean: 1), and patients who had longer median response times for the first treatment (median: 23 months) (18). Further investigations are needed to confirm the effects of these different factors on survival of these patients.

To our best knowledge, the present systematic review is the first to examine the effect of lenalidomide monotherapy for DLBCL patients with R/R status. Our results indicated this treatment was active and tolerable, but these results should be considered with caution because the data were mostly from low-quality observational studies. For instance, one of the limitations of the present systematic review is the presence of selection bias regarding patient inclusion. Large and rigorously designed studies on this topic are needed to confirm the efficiency and safety of lenalidomide monotherapy for DLBCL patients with R/R status.

Conclusion

The results of the present study suggest that lenalidomide monotherapy was active for DLBCL patients with R/R status and leads to AEs that are mostly manageable. The non-GCB subgroup of these patients had greater tumor responsiveness than the GCB subgroup.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

OB designed and JL performed most of the investigation, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. JZ, WG, XW, and YZ provided data collection assistance. JZ contributed to interpretation of the data and analyses. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.756728/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Wild CP, Stewart BW, Wild C. World Cancer Report 2014. Switzerland: World Health Organization Geneva (2014).

2. Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, et al. Long-Term Outcome of Patients in the LNH-98.5 Trial, the First Randomized Study Comparing Rituximab-CHOP to Standard CHOP Chemotherapy in DLBCL Patients: A Study by the Groupe d’Etudes Des Lymphomes De l’Adulte. Blood (2010) 116:2040–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246

3. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. J Clin Oncol (2014) 32:3059–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800

4. Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, Sieber M, Carella AM, Haenel M, et al. Aggressive Conventional Chemotherapy Compared With High-Dose Chemotherapy With Autologous Haemopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation for Relapsed Chemosensitive Hodgkin’s Disease: A Randomised Trial. Lancet (2002) 359:2065–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08938-9

5. Chiappella A, Vitolo U. Lenalidomide in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas. Adv Hematol (2012) 2012:498342. doi: 10.1155/2012/498342

6. Garciaz S, Coso D, Schiano de Colella JM, Bouabdallah R. Lenalidomide for the Treatment of B-Cell Lymphoma. Expert Opin Investigational Drugs (2016) 25:1103–16. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1208170

7. Beylot-Barry M, Mermin D, Maillard A, Bouabdallah R, Bonnet N, Duval-Modeste AB, et al. A Single-Arm Phase II Trial of Lenalidomide in Relapsing or Refractory Primary Cutaneous Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type. J Invest Dermatol (2018) 138:1982–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.03.1516

8. Wiernik PH, Lossos IS, Tuscano JM, Justice G, Vose JM, Cole CE, et al. Lenalidomide Monotherapy in Relapsed or Refractory Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2008) 26:4952–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3429

9. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Bmj (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

10. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. J Clin Epidemiol (2021) 134:178–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

11. Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH, Van den Abbeele AD. Revised RECIST Guideline Version 1.1: What Oncologists Want to Know and What Radiologists Need to Know. AJR Am J Roentgenol (2010) 195:281–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4110

12. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Ctcae) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Ctcae) V5. 0. (2017).

13. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ (2016) 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

14. Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Deeb G, Zinzani PL, Pileri SA, Malik F, Macon WR, et al. Higher Response to Lenalidomide in Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Nongerminal Center B-Cell-Like Than in Germinal Center B-Cell-Like Phenotype. Cancer (2011) 117:5058–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26135

15. Witzig TE, Vose JM, Zinzani PL, Reeder CB, Buckstein R, Polikoff JA, et al. An International Phase II Trial of Single-Agent Lenalidomide for Relapsed or Refractory Aggressive B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol (2011) 22:1622–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq626

16. Lakshmaiah KC, Shetty KSR, Sathyanarayanan V, Lokanatha D, Abraham LJ, Babu KG. Lenalidomide in Relapsed Refractory Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: An Indian Perspective. J Cancer Res Ther (2015) 11:857–61. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.151418

17. Zinzani PL, Rigacci L, Cox MC, Devizzi L, Fabbri A, Zaccaria A, et al. Lenalidomide Monotherapy in Heavily Pretreated Patients With Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: An Italian Observational Multicenter Retrospective Study in Daily Clinical Practice. Leukemia Lymphoma (2015) 56:1671–6. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.964702

18. Mondello P, Steiner N, Willenbacher W, Ferrero S, Marabese A, Pitini V, et al. Lenalidomide in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: Is It a Valid Treatment Option? Haematologica (2016) 101:278–. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0103

19. Czuczman MS, Trneny M, Davies A, Rule S, Linton KM, Wagner-Johnston N, et al. A Phase 2/3 Multicenter, Randomized, Open-Label Study to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Lenalidomide Versus Investigator’s Choice in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res (2017) 23:4127–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2818

20. Ferreri AJM, Sassone M, Zaja F, Re A, Spina M, Rocco AD, et al. Lenalidomide Maintenance in Patients With Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Who Are Not Eligible for Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation: An Open Label, Single-Arm, Multicentre Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Haematology (2017) 4:e137–46. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30016-9

21. Ferreri AJM, Sassone M, Angelillo P, Zaja F, Re A, Di Rocco A, et al. Long-Lasting Efficacy and Safety of Lenalidomide Maintenance in Patients With Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Who Are Not Eligible for or Failed Autologous Transplantation. Hematological Oncol (2020) 38:257–65. doi: 10.1002/hon.2742

22. Broccoli A, Casadei B, Chiappella A, Visco C, Tani M, Cascavilla N, et al. Lenalidomide in Pretreated Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: An Italian Observational Multicenter Retrospective Study in Daily Clinical Practice. oncologist (2019) 24:1246–52. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0603

23. Gribben JG, Fowler N, Morschhauser F. Mechanisms of Action of Lenalidomide in B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol (2015) 33:2803–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5363

24. Morschhauser FA, Cartron G, Thieblemont C, Solal-Céligny P, Haioun C, Bouabdallah R, et al. Obinutuzumab (GA101) Monotherapy in Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma or Mantle-Cell Lymphoma: Results From the Phase II GAUGUIN Study. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31:2912–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.9585

25. Jurczak W, Zinzani PL, Gaidano G, Goy A, Provencio M, Nagy Z, et al. Phase IIa Study of Single-Agent MOR208 in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Blood (2015) 126:1528. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.1528.1528

26. Salles G, Duell J, González Barca E, Tournilhac O, Jurczak W, Liberati AM, et al. Tafasitamab Plus Lenalidomide in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (L-MIND): A Multicentre, Prospective, Single-Arm, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol (2020) 21:978–88. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30225-4

27. Zinzani PL, Rodgers T, Marino D, Frezzato M, Barbui AM, Castellino C, et al. RE-MIND: Comparing Tafasitamab + Lenalidomide (L-MIND) With a Real-World Lenalidomide Monotherapy Cohort in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res (2021) 27(22):6124–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1471

28. Ma LY, Su L. Application of Lenalidomide on Diffused Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Salvage, Maintenance, and Induction Treatment. Chin Med J (2018) 131:2510–3. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.243567

29. Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, Fisher RI, et al. The Use of Molecular Profiling to Predict Survival After Chemotherapy for Diffuse Large-B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med (2002) 346:1937–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914

30. Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, et al. Distinct Types of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Identified by Gene Expression Profiling. Nature (2000) 403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501

31. Karmali R, Gordon LI. Molecular Subtyping in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: Closer to an Approach of Precision Therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol (2017) 18:11. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0449-1

32. Cho MC, Chung YS, Jang S, Park C, Chi H, Huh J, et al. Prognostic Impact of Germinal Center B-Cell-Like and Non-Germinal Center B-Cell-Like Subtypes of Bone Marrow Involvement in Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Treated With R-CHOP. Medicine (2018) 97:e13046. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013046

33. Lopez-Girona A, Heintel D, Zhang LH, Mendy D, Gaidarova S, Brady H, et al. Lenalidomide Downregulates the Cell Survival Factor, Interferon Regulatory Factor-4, Providing a Potential Mechanistic Link for Predicting Response. Br J Haematol (2011) 154:325–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08689.x

34. Zhang LH, Kosek J, Wang M, Heise C, Schafer PH, Chopra R. Lenalidomide Efficacy in Activated B-Cell-Like Subtype Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Is Dependent Upon IRF4 and Cereblon Expression. Br J Haematol (2013) 160:487–502. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12172

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, lenalidomide, monotherapy, treatment outcome, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Li J, Zhou J, Guo W, Wang X, Zhao Y and Bai O (2021) Efficacy and Safety of Lenalidomide Monotherapy for Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 11:756728. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.756728

Received: 11 August 2021; Accepted: 11 November 2021;

Published: 02 December 2021.

Edited by:

Jignesh D. Dalal, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

Monica Balzarotti, Humanitas Research Hospital, ItalyUmberto Vitolo, Fondazione del Piemonte per l’Oncologia, Istituto di Candiolo (IRCCS), Italy

Copyright © 2021 Li, Zhou, Guo, Wang, Zhao and Bai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ou Bai, YmFpb3VAamx1LmVkdS5jbg==

Jia Li

Jia Li Jianpeng Zhou

Jianpeng Zhou Wei Guo1

Wei Guo1 Ou Bai

Ou Bai