94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 13 September 2021

Sec. Gynecological Oncology

Volume 11 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.730753

This article is part of the Research Topic The Evolving Use of Neoadjuvant Treatment Paradigms in Gynecologic Malignancies: Early Insights into Pharmacodynamic and Clinical Outcomes View all 6 articles

Weili Li1†

Weili Li1† Wenling Zhang1†

Wenling Zhang1† Lixin Sun2†

Lixin Sun2† Li Wang3†

Li Wang3† Zhumei Cui4

Zhumei Cui4 Hongwei Zhao2

Hongwei Zhao2 Danbo Wang5

Danbo Wang5 Yi Zhang6

Yi Zhang6 Jianxin Guo7

Jianxin Guo7 Ying Yang8

Ying Yang8 Wuliang Wang9

Wuliang Wang9 Xiaonong Bin10

Xiaonong Bin10 Jinghe Lang1,11

Jinghe Lang1,11 Ping Liu1*

Ping Liu1* Chunlin Chen1*

Chunlin Chen1*Objective: To compare the 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) of patients with cervical cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery (NACT) with those who received abdominal radical hysterectomy alone (ARH).

Methods: We retrospectively compared the oncological outcomes of 1410 patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer who received NACT (n=583) or ARH (n=827). The patients in the NACT group were divided into an NACT-sensitive group and an NACT-insensitive group according to their response to chemotherapy.

Results: The 5-year oncological outcomes were significantly better in the NACT group than in the ARH group (OS: 96.2% vs. 91.2%, respectively, p=0.002; DFS: 92.2% vs. 87.5%, respectively, p=0.016). Cox multivariate analysis suggested that NACT was independently associated with a better 5-year OS (HR=0.496; 95% CI, 0.281-0.875; p=0.015), but it was not an independent factor for 5-year DFS (HR=0.760; 95% CI, 0.505-1.145; p=0.189). After matching, the 5-year oncological outcomes of the NACT group were better than those of the ARH group. Cox multivariate analysis suggested that NACT was still an independent protective factor for 5-year OS (HR=0.503; 95% CI, 0.275-0.918; p=0.025). The proportion of patients in the NACT group who received postoperative radiotherapy was significantly lower than that in the ARH group (p<0.001). Compared to the ARH group, the NACT-sensitive group had similar results as the NACT group. The NACT-insensitive group and the ARH group had similar 5-year oncological outcomes and proportions of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy.

Conclusion: Among patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer, NACT improved 5-year OS and was associated with a reduction in the proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy. These findings suggest that patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer, especially those who are sensitive to chemotherapy, might consider NACT followed by surgery.

Globally, cervical cancer is a common malignant tumor in females, and it ranks fourth in terms of mortality (1, 2). In 2018, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) defined a new stage of cervical cancer, stage IB3, which is stage IB2 cervical cancer (FIGO 2009) but does not include cases of lymph node metastases (1, 3, 4). All cases involving pelvic lymph nodes and/or para-aortic lymph node metastases were classified as new stage IIIC. This classification raises questions as to whether the previous treatment recommendations for stage IB2 cervical cancer (FIGO 2009) are appropriate for the treatment of FIGO 2018 stage IB3. There is currently no clinical evidence supporting the choice of a specific treatment strategy in cases of FIGO 2018 stage IB3 cervical cancer.

It remains controversial whether NACT improves the oncological outcomes of patients with stage IB2 (FIGO 2009) cervical cancer compared to the standard treatment (5–12). Some studies have indicated that NACT improves patient prognosis (8, 10, 11), especially for patients who are sensitive to NACT (8, 11). Others have shown that the prognosis of cervical cancer patients who receive abdominal radical hysterectomy (ARH) or concurrent chemoradiotherapy is similar to that of patients who receive NACT followed by surgery. Some studies conducted in Japan and China have suggested that NACT does not improve the prognosis but reduces the proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy (12, 13).

The present study retrospectively analyzed the oncological outcomes of patients receiving NACT followed by surgery versus ARH alone based on the FIGO 2018 staging guidelines for stage IB3 cervical cancer. Based on the clinical diagnosis and treatment for cervical cancer in China (Four C) database, we aimed to assess the impact of NACT and its sensitivity on the oncological outcomes of stage IB3 cervical cancer patients.

This multicenter retrospective cohort study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Southern Hospital of Southern Medical University (approval number NFEC-2017-135; clinical study registration number CHiCTR1800017778, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Port, https://trialsearch.who.int/Default.aspx). The Four C database was created in cooperation with 47 hospitals in mainland China and includes data on 63,926 cervical cancer patients who were hospitalized between 2004 and 2018. The methods used for data entry, follow-up, double input and database establishment have been described previously (14, 15). The clinical staging of the patients in the database was revised according to the new FIGO 2018 staging system (1, 4).

In this study, the inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥ 18 years; histology indicating squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma; FIGO stage IB3 (FIGO 2018 staging system); NACT followed by surgery (NACT group) or ARH alone (ARH group); and QM type B or type C radical hysterectomy [Querleu and Morrow surgical classification system (16)] + pelvic lymphadenectomy ± para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Most of the patients in the NACT group received paclitaxel + platinum or platinum, generally in 1-2 courses. The NACT group received preoperative chemotherapy for 2-3 weeks followed by surgical treatment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: preoperative radiotherapy or radiotherapy and chemotherapy and the presence of other malignant tumors, pregnancy or stump cancer.

Because there may be differences in the clinical data (age, initial tumor diameter, and histological type) among the NACT group, ARH group and subgroups, we used the PSM method to balance those factors to ensure comparability.

Before and after PSM, Cox multivariate analysis was performed using the following factors: age, NACT, histology, surgical margin invasion, parametrial involvement, initial tumor diameter, deep stromal invasion, and lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI). The changes in tumor diameter before and after NACT were measured in accordance with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) standard (17). According to the RECIST standard, the numbers of patients with complete response, partial response, stable disease and progressive disease after NACT were 30 (7.09%), 284 (67.14%), 67 (15.84%) and 42 (9.93%), respectively. Patients exhibiting a complete response or a partial response in the NACT group were regarded as the NACT-sensitive group, while patients with stable disease or progressive disease were regarded as the NACT-insensitive group.

The main observation outcomes were 5-year overall survival (OS) and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) in the NACT group, the ARH group and the subgroups. OS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to death from any cause. DFS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to death or to the first evidence of recurrence. Patients with no evidence of recurrence or death were defined by the date of the last follow-up date or the last outpatient visit.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two independent sample t tests were used for continuous variables, and the X2 test or the nonparametric test was used for categorical variables and graded variables. The log-rank test in the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method was used to compare the 5-year oncological outcomes (OS and DFS) of the two groups. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the multivariate analysis. In this study, logistic regression analysis was used. If the equal proportional hazard assumption was satisfied, logistic regression analysis was used to adjust the influence of other confounding factors on the pathological factors. If the equal proportion risk assumption was not satisfied, then nonequal proportion logistic regression was considered to analyze the influence of the research factors. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Statisticians reviewed all statistical methods and statistical processes used in this study.

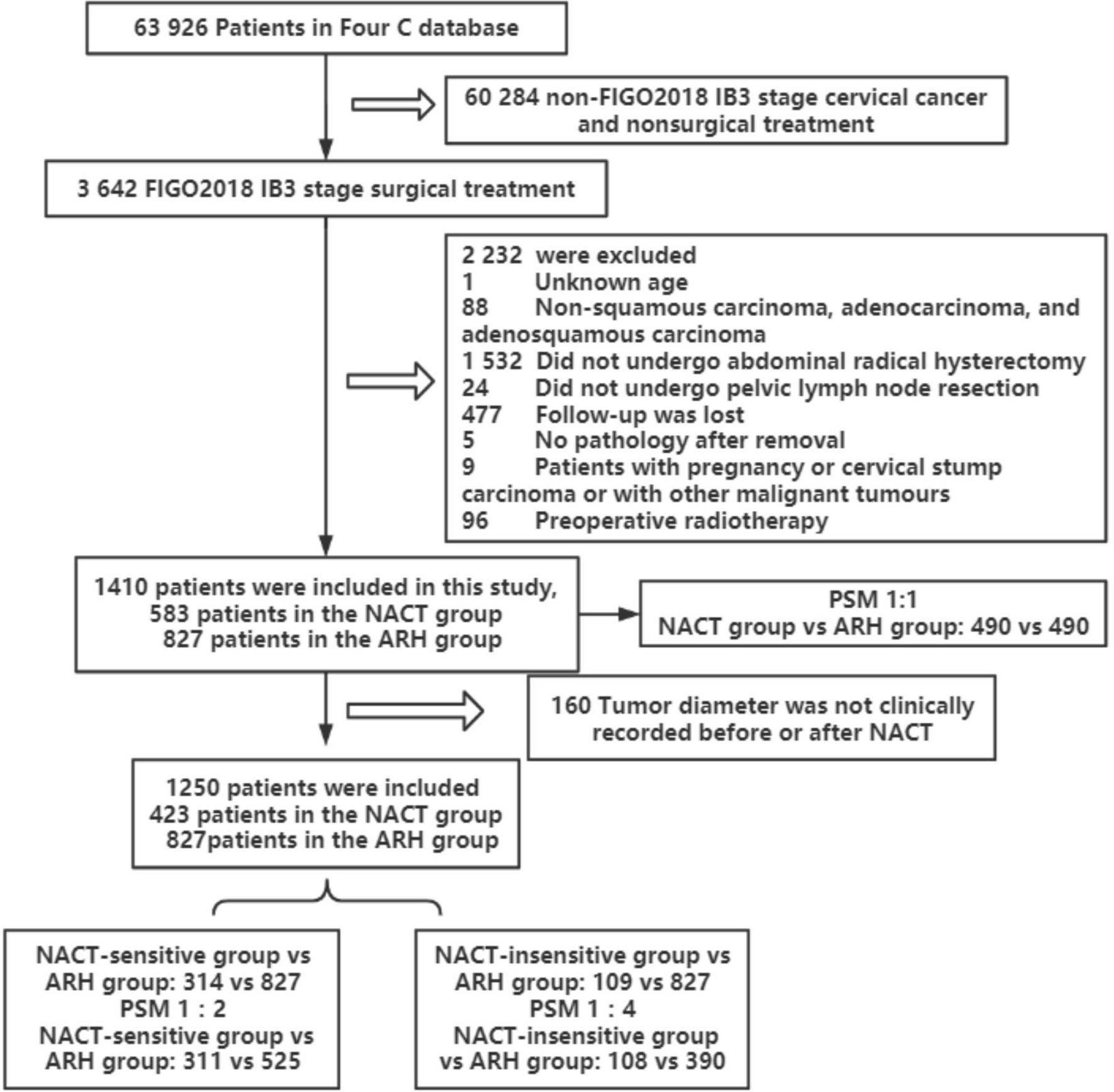

A total of 1410 patients were included: 583 in the NACT group and 827 in the ARH group. The median follow-up time was 41 months. The median follow-up times for patients in the NACT and ARH groups were 40 months and 41 months, respectively. Information on tumor diameter before or after NACT was missing for 160 of the 583 patients in the NACT group, and information on tumor diameter both before and after NACT was available for 423 of the patients. Of those 423 patients, 352 had imaging data and 71 had no imaging data before NACT, while 225 had imaging data and 198 had no imaging data after NACT (Table 1). The data screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Flowchart of patients included in the analysis (NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy).

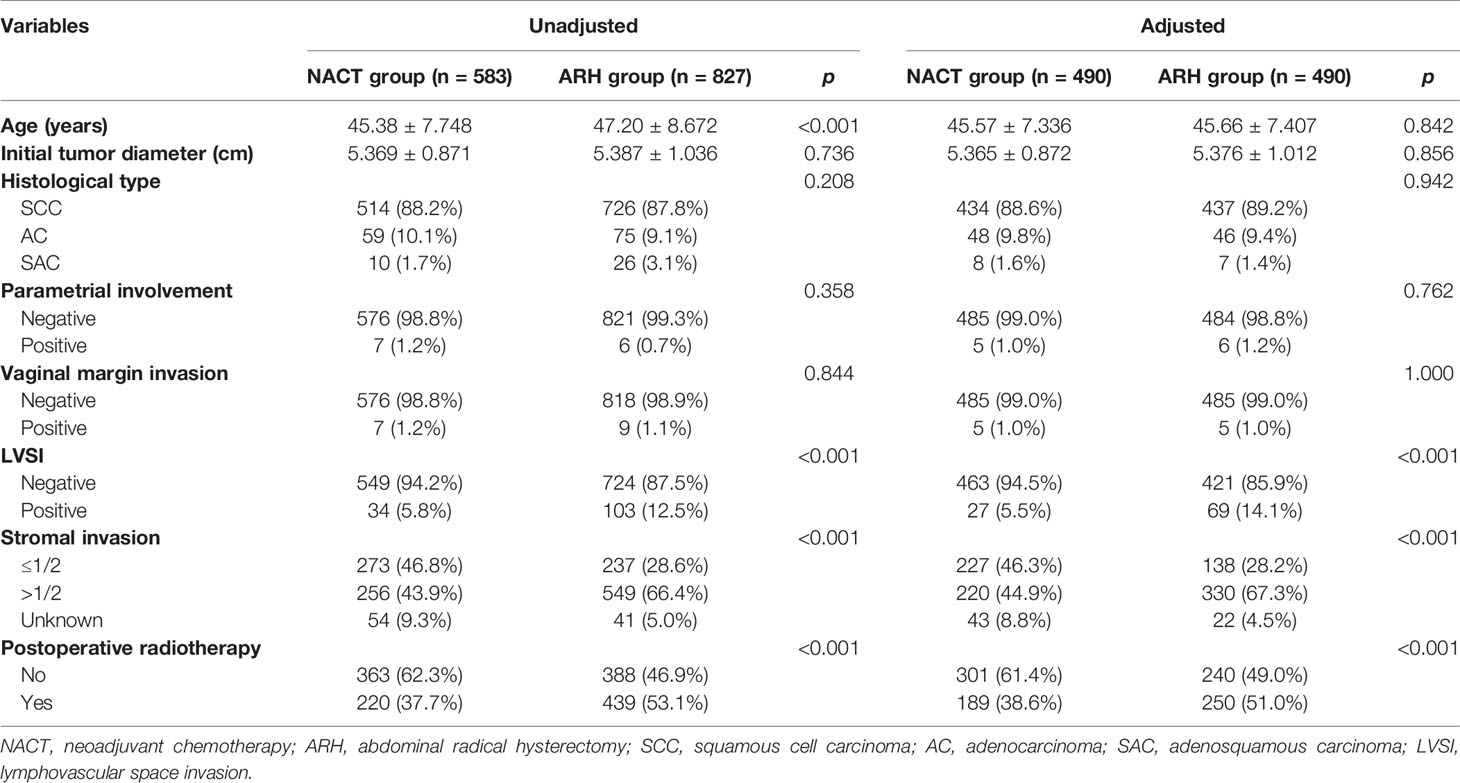

Among the total study population, the difference in oncological outcomes between the NACT group (n=583) and the ARH group (n=827) was significant (OS: 96.2% vs. 91.2%, respectively, p=0.002; DFS: 92.2% vs. 87.5%, respectively, p=0.016). The 5-year oncological outcomes of the NACT group were better than those of the ARH group. Cox multivariate analysis suggested that NACT was independently associated with better 5-year OS (HR=0.496; 95% CI, 0.281-0.875; p=0.015) but was not an independent factor for 5-year DFS (HR=0.760; 95% CI, 0.505-1.145; p=0.189). LVSI positivity was an independent risk factor for 5-year DFS (HR=2.143; 95% CI, 1.343-3.419; p=0.001). The proportion of patients in the NACT group receiving postoperative radiotherapy was significantly lower than the proportion in the ARH group [220 (37.7%) vs. 439 (53.1%), respectively, p<0.001].

The NACT group and the ARH group were unbalanced at baseline. After 1:1 PSM, 490 cases were included in each group (Table 2, Figure 2). The 5-year oncological outcomes of the NACT group were better than those of the ARH group. Cox multivariate analysis indicated that NACT was still an independent protective factor for 5-year OS (HR=0.503; 95% CI, 0.275-0.918; p=0.025) but not an independent protective factor for 5-year DFS (p=0.114). LVSI positivity was found to be an independent risk factor for 5-year DFS (HR=2.082; 95% CI, 1.218-3.5557; p=0.007). The proportion of patients in the NACT group who received postoperative radiotherapy was significantly lower than that in the ARH group [189 (38.6%) vs. 250 (51.0%), respectively, p<0.001].

Table 2 Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in the NACT and ARH groups.

Figure 2 Survival curves of patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in the NACT and ARH groups (unadjusted, panels (A, B); adjusted, panels (C, D); NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy).

The NACT group had a significantly lower rate of detection of postoperative LVSI and deep stromal invasion than in the ARH group [before matching: LVSI, 34 (5.8%) vs. 103 (12.5%), respectively, p<0.001, deep stromal invasion, 256 (43.9%) vs. 549 (66.4%), respectively, p<0.001; after matching: LVSI, 27 (5.5%) vs. 69 (14.1%), respectively, p<0.001, deep stromal invasion: 220 (44.9%) vs. 330 (67.3%), respectively, p<0.001]. There was no statistically significant difference in parauterine infiltration or vaginal margin infiltration between the two groups. Logistic regression analysis showed that NACT was an independent protective factor for postoperative cervical deep stromal invasion and LVSI (p<0.001).

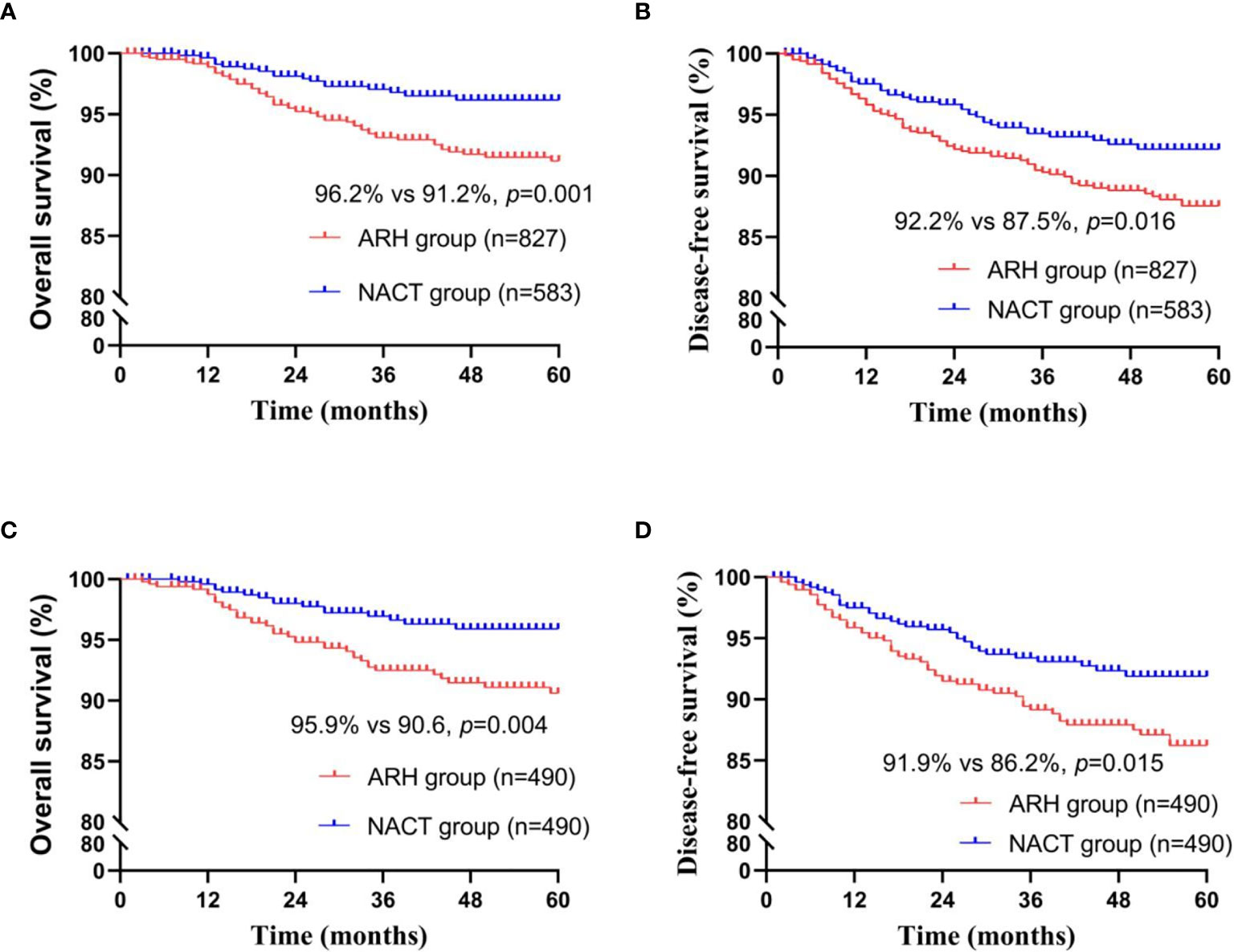

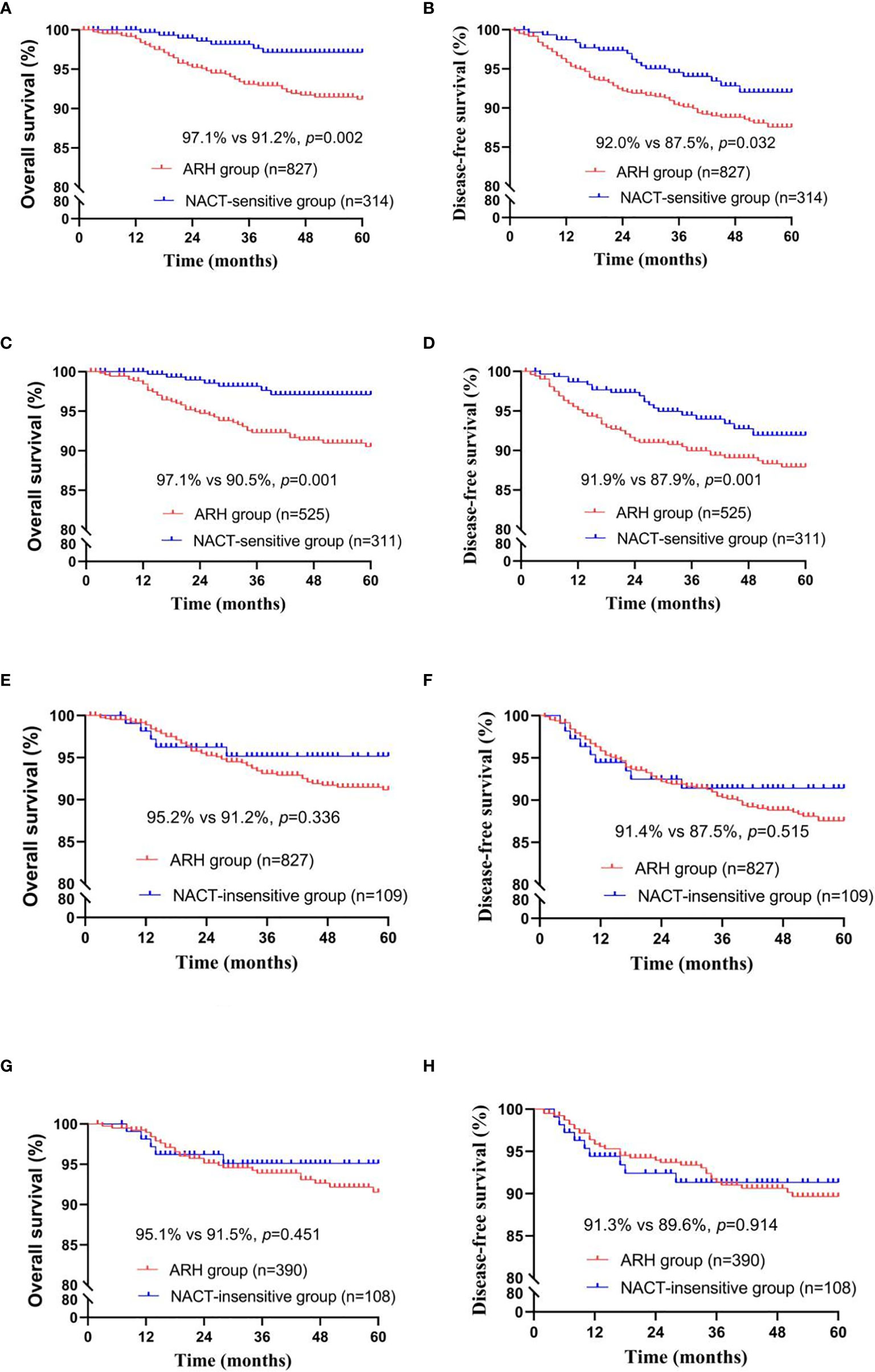

The NACT-sensitive group consisted of 314 patients. Among the total study population, the 5-year oncological outcomes of the NACT-sensitive group with stage IB3 cervical cancer were significantly better than those of the ARH group (OS: 97.1% vs. 91.2%, respectively, p=0.002; DFS: 92.0% vs. 87.5%, respectively, p=0.032). Cox multivariate analysis suggested that NACT sensitivity was an independent protective factor for 5-year OS (HR=0.354; 95% CI, 0.159-0.788; p=0.011) but not an independent protective factor for 5-year DFS. LVSI positivity was found to be an independent risk factor for 5-year DFS. The proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy in the NACT-sensitive group was significantly lower than that in the ARH group [108 (34.4%) vs. 439 (53.1%), respectively, p<0.001].

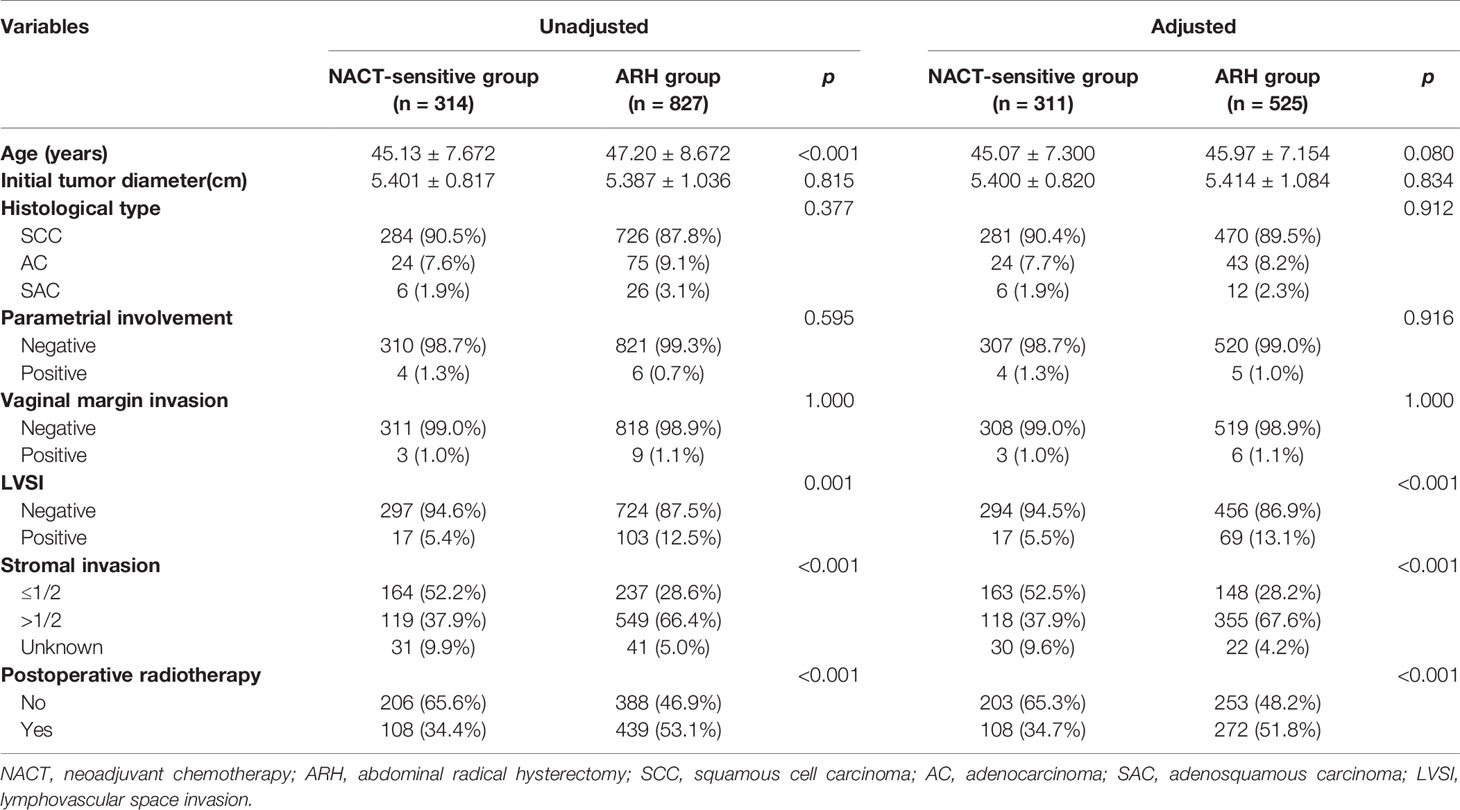

After 1:2 PSM, 311 patients and 525 patients were included in the NACT-sensitive group and the ARH group, respectively (Table 3, Figure 3). The 5-year oncological outcomes of the NACT sensitivity group were better than those of the ARH group (OS: 97.1% vs. 90.5%, respectively, p=0.001; DFS: 91.9% vs. 87.9%, respectively, p=0.041). Cox multivariate analysis suggested that NACT sensitivity was an independent protective factor for 5-year OS (HR=0.326; 95% CI, 0.144-0.741; p=0.007) but not an independent protective factor for 5-year DFS. LVSI positivity was an independent risk factor for 5-year DFS. The proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy in the NACT-sensitive group was significantly lower than that in the ARH group [108 (34.7%) vs. 272 (51.8%), respectively, p<0.001].

Table 3 Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in the NACT-sensitive and ARH groups.

Figure 3 Survival curves of patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in the NACT-sensitive/NACT-insensitive and ARH groups [NACT-sensitive: unadjusted, panels (A, B); adjusted, panels (C, D); NACT-insensitive: unadjusted, panels (E, F); adjusted, panels (G, H); NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy].

The NACT-sensitive group had a significantly lower rate of detection of postoperative LVSI and deep stromal invasion than the ARH group [before matching: LVSI, 17 (5.4%) vs. 103 (12.5%), respectively, p<0.001, deep stromal invasion, 119 (37.9%) vs. 549 (66.4%), respectively, p<0.001; after matching: LVSI, 17 (5.5%) vs. 69 (13.1%), respectively, p<0.001, deep stromal invasion, 118 (37.9%) vs. 355 (67.6%), respectively, p<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in surgical margin invasion or parametrial involvement between the two groups. Logistic regression analysis showed that NACT sensitivity was an independent protective factor for postoperative cervical deep stromal invasion and LVSI (p<0.05).

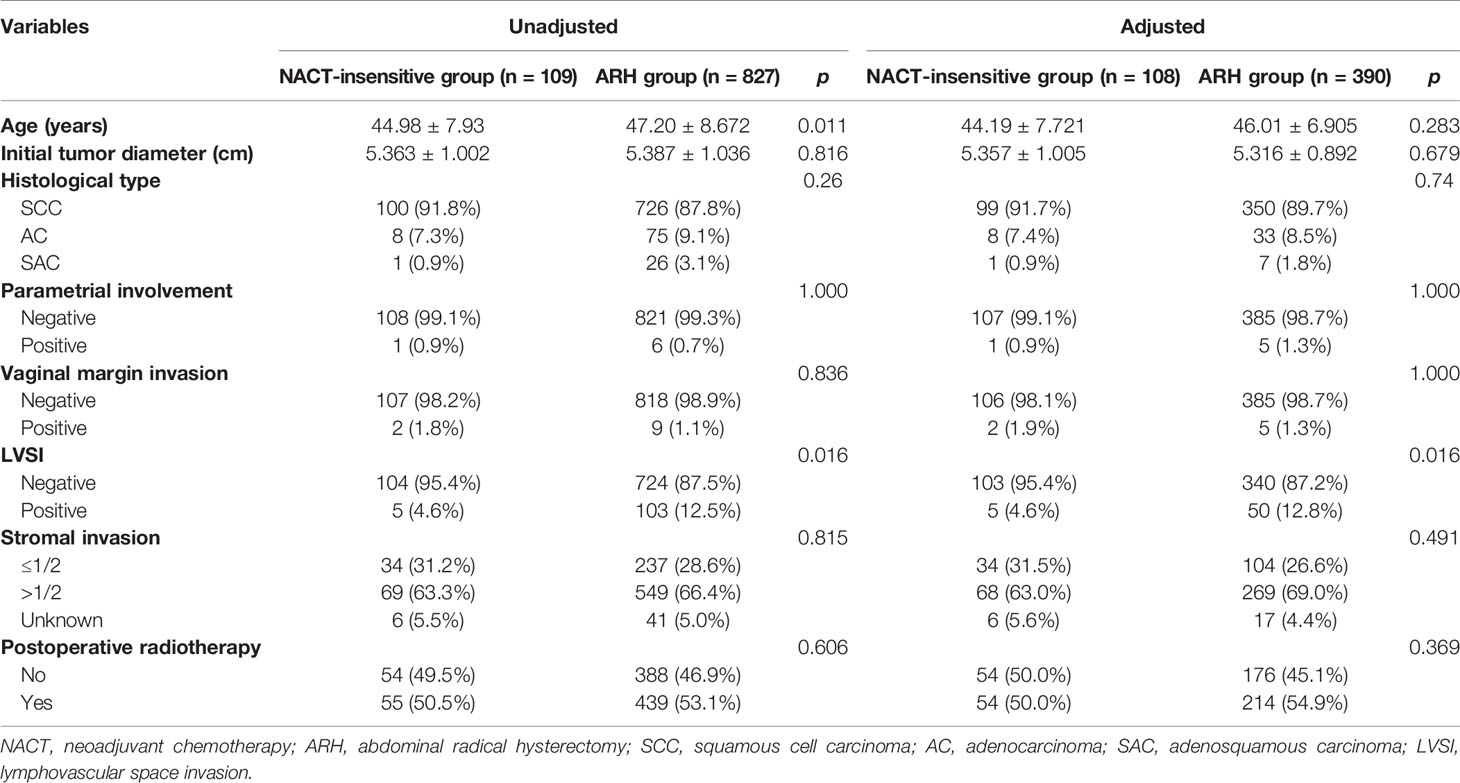

There were 109 patients in the NACT-insensitive group. There was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year oncological outcomes between the NACT-insensitive group with stage IB3 cervical cancer and the ARH group. Cox multivariate analysis indicated that NACT insensitivity was not an independent factor for 5-year oncological outcomes. The proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy in the NACT-insensitive group was similar to that in the ARH group, and the difference was not significant (p=0.606).

After 1:4 PSM, the NACT-insensitive group and the ARH group included 108 cases and 390 cases, respectively (Table 4, Figure 3). There were no significant differences in the 5-year oncological outcomes or in the proportion of patients receiving radiotherapy between the NACT-insensitive group and the ARH group (p=0.369).

Table 4 Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in the NACT-insensitive and ARH groups.

The NACT-insensitive group had a significantly lower rate of detection of postoperative LVSI than the ARH group [before matching: LVSI, 5 (4.6%) vs. 103 (12.5%), respectively, p<0.001; after matching: LVSI, 5(4.6%) vs. 50(12.8%), respectively, p<0.001]. There was no statistically significant difference in deep stromal infiltration, surgical margin invasion or parametrial involvement between the two groups. Logistic regression analysis showed that NACT, even in the insensitive group, was an independent protective factor for postoperative LVSI (p<0.05).

The present study found that NACT improved the 5-year OS of patients with FIGO 2018 stage IB3 cervical cancer and reduced the positive rates of postoperative LVSI and cervical deep stromal infiltration, thereby reducing the proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy. These results suggest that patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer undergoing ARH, especially NACT-sensitive patients, might receive NACT to help reduce the postoperative complications caused by radiotherapy.

The previous literature has mainly focused on the effect of NACT on the prognosis of stage IB2 or locally advanced cervical cancer (FIGO 2009). Some studies have considered that surgery after NACT improves patient prognosis (8–11, 18–20), especially for patients who are sensitive to NACT (8, 11, 19, 20). Sardi et al. (10) found in a prospective randomized controlled study of stage IB cervical squamous cell carcinoma (d>4cm) that the survival and DFS of patients who received NACT were better than those of patients who underwent direct surgery or postoperative radiotherapy; this finding is consistent with the conclusion of the present study. Cai et al. (8) also obtained similar results for patients with stage IB (d>4 cm) cervical carcinoma. Chen et al. (11) included patients with stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer and found that modified preoperative NACT was beneficial in reducing tumor size, eliminating pathological risk factors, and improving the prognosis of responders. Gadducci et al. (20) found that NACT followed by surgery is an effective treatment for stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer and that the pathological response to NACT is the most important factor affecting the prognosis.

Studies have also found that the prognosis of patients who receive NACT followed by surgery is similar to that of patients who receive ARH alone or concurrent radiotherapy (12, 13, 21, 22). Some studies (12, 13) have suggested that although NACT does not improve prognosis, it reduces the proportion of patients who require postoperative radiotherapy. Katsumata et al. (12) showed that NACT followed by surgery does not improve OS compared to direct surgery in patients with stage IB2, IIA2 and IIB cervical cancer but that it may reduce the proportion of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy. These differing results from those obtained in our study may be due to later staging (more than half were stage IIB) and the inclusion of patients with lymph node metastases. Yang et al. (13) reported no difference in 1-year and 3-year OS or DFS between the NACT group and the direct operation group in patients with stage IB2, IIA2 and IIB cervical cancer, and the authors reported that the number of patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy was reduced in the NACT group. That study included many patients with late-stage disease as more than half of the included patients were stage IIB, and patients with stage IB2 accounted for approximately 17.4% (19/109) and 22.7% (25/110) of the patients in the NACT group and the direct operation group, respectively, which may explain why their results differ from those obtained in our study. Most of the cervical cancer patients included in the studies by Duenas-Gonzalez et al. (9) and Gupta et al. (21), who analyzed the prognosis between chemoradiotherapy and NACT followed by surgery, were at or above stage IIB.

Due to the controversy over the efficacy of NACT, the international community has generally maintained a cautious attitude. The 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (23) recommend concurrent chemoradiotherapy for patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer (level of evidence 1) or radical hysterectomy + PL ± PAL (level of evidence 2B). The FIGO Cancer Report 2018 (1) also emphasizes that NACT for cervical cancer is only recommended for use in areas that lack radiotherapy facilities, in prospective studies and in clinical trials. For patients with stage IB2 cervical cancer (FIGO 2009), NACT followed by surgery or ARH is also common in some institutions in Asia and Europe (11, 12, 20). Therefore, there is no multicenter or large-sample clinical evidence that addresses whether the recommended treatment for stage IB2 cervical cancer based on the FIGO stage as defined in 2009 is still suitable for the treatment of stage IB3 defined according to the FIGO 2018 guidelines.

Compared to radiotherapy, surgery has the following two recognized advantages: (1) it preserves ovarian function and (2) it causes less damage in terms of vaginal shortening and sexual function, especially in young women. For these reasons, more patients in China with stage IB3 cervical cancer choose surgery. Previous studies (9, 11–13, 20, 21) mostly evaluated patients with cervical cancer stage IB2 and IIA2 (FIGO 2009), or even included those with more advanced cervical cancer, with a low proportion of patients with stage IB2 cervical cancer (FIGO 2009). Moreover, the FIGO 2018 guidelines for stage IB3 cervical cancer excluded lymph node metastasis, and stage IB3 is an earlier stage than stages IIA2 and IIB. To date, there have been no studies discussing the therapeutic effect of NACT followed by surgery compared to ARH on stage IB3 cervical cancer. Based on the Four C database, it was concluded that the 5-year OS of the NACT group was better than that of the ARH group in patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer, especially for patients with NACT sensitivity. Thus, compared to ARH alone, NACT followed by surgery may be a better treatment option.

In the present study, there were 423 patients for whom tumor diameter records before and after NACT treatment were available. Of these, 314 were NACT-sensitive patients with an effective rate of 74.23%, and 109 were NACT-insensitive patients with an inefficiency of 25.77%. The effective rate in this study was slightly lower than that reported in the literature, which ranges from 79.5% to 84.6% (8, 24); this result may be related to the elimination of 160 patients with unrecorded tumor diameters before or after NACT from the study group, resulting in a certain degree of bias. The oncological outcomes and the radiotherapy rate of NACT-insensitive patients were comparable to those of ARH patients, and NACT insensitivity did not improve patient prognosis but rather increased hospitalization costs and chemotherapy side effects. Therefore, these findings suggest that screening for NACT-sensitive patients is of great significance (11, 20). Sun et al. found that radiomic analysis effectively screens for NACT-sensitive patients (25).

The FIGO Cancer Report 2018 mentions that NACT may conceal some pathological results, that it may affect decisions regarding whether adjuvant treatment should be administered after surgery and that patients with large tumor diameters and pathological types of adenocarcinoma have a low response rate to NACT (1). Some studies have noted that the prognosis of patient who receive surgery after NACT may be related to the patient’s age, initial tumor diameter and pathological type (26). The present study used age, initial tumor diameter, and pathological type as the baseline, and there were no significant differences in these parameters between the two groups. Therefore, we concluded that NACT or NACT sensitivity improves the OS of patients and reduces the proportion of patients requiring postoperative radiotherapy, perhaps because NACT or NACT sensitivity reduces the intermediate-risk factors for postoperative pathology. Li et al. retrospectively found that NACT reduces the positive rate of “intermediate-risk factors” for LVSI and deep stromal invasion in patients with cervical squamous cell carcinoma stage IB2 and IIA2 as defined by FIGO (2009) (27). Our study suggested that NACT and NACT-sensitive patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer had reduced positivity for LVSI and deep stromal infiltration. According to the “Sedlis criteria” for intermediate-risk factors based on the NCCN guidelines (23, 28), these patients had a reduced need for postoperative radiotherapy. In univariate analysis, the 5-year DFS of both the NACT group and the NACT-sensitive group was superior to that of the ARH group. Cox multivariate analysis showed that NACT or NACT sensitivity was not an independent protective factor for DFS. There may be a certain interaction between NACT and LVSI. The DFS of the NACT group was higher than that of the ARH group because the postoperative pathology was not matched in the univariate analysis. However, the interaction between the NACT and LVSI was considered in the Cox multivariate analysis, and LVSI positivity was an independent risk factor for DFS. NACT and NACT sensitivity are not independent protective factors for DFS.

Our study is one of the first population-based studies to compare 5-year OS and DFS after treatment with NACT followed by surgery and after treatment with ARH alone in stage IB3 cervical cancer patients and related subgroups. First, the strength of the present study was its large sample size. Our study analyzed a large cohort of cervical cancer patients who were treated over a 14-year period at 47 hospitals. Second, this study may be the first to investigate the oncological outcomes of patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer (as defined by FIGO 2018) who were treated with NACT followed by surgery or with ARH alone. In previous studies, most patients with stage IB2 and IIA2 or more advanced stage cervical cancer (FIGO 2009) were combined and discussed. The proportion of patients with stage IB2 cervical cancer in those studies was low, and patients with lymph node metastasis were included. In addition, patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were not excluded from the surgical approach. Because the 2018 Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) Trial (29) indicated that laparoscopic surgery is not conducive to the oncological outcomes of patients with cervical cancer, patients who received laparoscopic surgery were excluded from our study. Ferrandina et al. found that minimally invasive radical surgery and open radical surgery were associated with similar rates of recurrence and death in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer whose cancers were managed by surgery after chemoradiation (30). This finding is worthy of further discussion regarding the oncological outcomes of laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgery in patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in the NACT group. The considerations described above may account for the differences in the conclusions between previous studies and the present study.

The present study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective study, it does not provide the highest level of evidence. Second, the NACT treatment plan may have had an impact on prognosis. The present study did not detail the impact of different plans and different treatment courses on patient prognosis. The present study analyzed only the proportion of patients who received postoperative radiotherapy and did not analyze postoperative complications. Third, all patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer in this study received surgical treatment, although in other countries most of these patients are treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy; this difference may make the conclusions not broadly applicable. However, the latest randomized controlled study (EORTC 55994) confirmed that the efficacy of NACT followed by surgery is similar to that of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer (FIGO 2009) with no difference in 5-year OS (72% and 76%, respectively, p=0.332) (31). Nama et al. (32) also reported that there is no single randomized controlled trial in which direct surgery for stage IB2 (FIGO 2009) is compared with chemoradiotherapy; thus, this area requires further research. The current results suggest that surgical treatment is an option for stage IB3 cervical cancer. In addition, our analysis of NACT sensitivity excluded patients whose tumor diameters before or after NACT were unknown. The clinical records were not standardized, which may have caused selection bias. Finally, the identification of NACT-sensitive patients before the administration of NACT was also an important prognostic factor.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that in patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer as defined in FIGO 2018, NACT before ARH can increase 5-year OS, reduce intermediate-risk factors for postoperative pathology, and reduce the proportion of patients requiring postoperative radiotherapy; the latter may reduce the complications caused by radiotherapy. Therefore, patients with stage IB3 cervical cancer, especially those who exhibit NACT sensitivity, might opt for receive NACT before ARH.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

WL, WZ, LS, and LW contribute equally to the work. WL: literature search, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, Methodology. WZ: Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. LS: Investigation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. LW: literature search, data collection, Investigation, Writing-Review & Editing. ZC: Investigation, Resources. HZ: Investigation, Resources. DW: Investigation, Resources. YZ: Investigation, Resources. JG: Investigation, Resources. YY: Investigation, Resources. WW: Investigation, Resources. XB: Formal analysis. JL: Supervision, Conceptualization. PL: Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration. CC: Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Support Program 252 of China (2014BAI05B03); the National Natural Science Fund of Guangdong 253 (2015A030311024) and the Science and Technology Plan of Guangzhou (158100075).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful to Min Hao (The Second Hospital of ShanXi Medical University), Bin Ling (China-Japan Friendship Hospital), LS (Shanxi Cancer Hospital), Jihong Liu and Lizhi Liang (Sun Yatsen University Cancer Center), Yu Guo (Anyang Tumor Hospital), Wentong Liang and Anwei Lu (Guizhou Provincial People`s Hospital), JG (Daping Hospital, The Third Military Medical University), Shaoguang Wang (The Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University), Xuemei Zhan and Mingwei Li (Jiangmen Central Hospital), Weifeng Zhang (Ningbo Women & Children’s Hospital), Peiyan Du (The Affiliated Cancer Hospital and Institute of Guangzhou Medical University), Ziyu Fang (Liuzhou workers’ hospital), Rui Yang (Shenzhen hospital of Peking University), Long Chen (Qingdao Municipal Hospital), Encheng Dai and Ruilei Liu (Linyi People’s Hospital), Yuanli He and Mubiao Liu (Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University), Jilong Yao and Zhihua Liu (Shenzhen Maternity & Child Health Hospital), Xueqin Wang (The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University),Yan Xu (Guangzhou Pan Yu Central Hospital), Ben Ma (Guangzhou First People’s Hospital), Zhonghai Wang (Shenzhen Nanshan People’s Hospital), Lin Zhu (The Second Hospital of Shandong University), Hongxin Pan (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University), Qianyong Zhu (No.153. Center Hospital of Liberation Army/Hospital No.988 of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Joint Support Force), Dingyuan Zeng and Zhong Lin (Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital of Liuzhou) and Xiaohong Wang (Laiwu People’s Hospital/Jinan City People’s Hospital) and Bin Zhu (The Affiliated Yiwu Women and Children Hospital of Hangzhou Medical College) for their contribution in data collection.

1. Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the Cervix Uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2018) 143 Suppl 2:22–36. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12611

2. Wild CP, Weiderpass E, Stewart BW eds. International Agency for Research on Cancer. In: . World Cancer Report: Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention. France: Lyon. Available at: http://publications.iarc.fr/586.

3. Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO Staging for Carcinoma of the Vulva, Cervix, and Endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2009) 105:103–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.012

4. Corrigendum to “Revised FIGO Staging for Carcinoma of the Cervix Uteri” [Int J Gynecol Obstet 145(2019) 129-135]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2019) 147(2):279–80. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12969

5. Iwata T, Miyauchi A, Suga Y, Nishio H, Nakamura M, Ohno A. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data From 21 Randomised Trials. Eur J Cancer (2003) 39(17):2470–86.

6. Mossa B, Mossa S, Corosu L, Marziani R. Follow-Up in a Long-Term Randomized Trial With Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Squamous Cell Cervical Carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol (2010) 31(5):497–503.

7. Eddy GL, Bundy BN, Creasman WT, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Hannigan E, et al. Treatment of (“Bulky”) Stage IB Cervical Cancer With or Without Neoadjuvant Vincristine and Cisplatin Prior to Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic/Para-Aortic Lymphadenectomy: A Phase III Trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol (2007) 106(2):362–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.04.007

8. Cai HB, Chen HZ, Yin HH. Randomized Study of Preoperative Chemotherapy Versus Primary Surgery for Stage IB Cervical Cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res (2006) 32(3):315–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2006.00404.x

9. Benedetti-Panici P, Greggi S, Colombo A, Amoroso M, Smaniotto D, Giannarelli D, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Radical Surgery Versus Exclusive Radiotherapy in Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Cervical Cancer: Results From the Italian Multicenter Randomized Study. J Clin Oncol (2002) 20(1):179–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.179

10. Sardi JE, Giaroli A, Sananes C, Ferreira M, Soderini A, Bermudez A, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of the First Randomized Trial Using Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage Ib Squamous Carcinoma of the Cervix: The Final Results. Gynecol Oncol (1997) 67(1):61–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4812

11. Chen H, Liang C, Zhang L, Huang S, Wu X. Clinical Efficacy of Modified Preoperative Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Locally Advanced (Stage IB2 to IIB) Cervical Cancer: Randomized Study. Gynecol Oncol (2008) 110(3):308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.026

12. Katsumata N, Yoshikawa H, Kobayashi H, Saito T, Kuzuya K, Nakanishi T, et al. Phase III Randomised Controlled Trial of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Plus Radical Surgery vs. Radical Surgery Alone for Stages IB2, IIA2, and IIB Cervical Cancer: A Japan Clinical Oncology Group Trial (JCOG 0102). Br J Cancer (2013) 108(10):1957–63. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.179

13. Yang Z, Chen D, Zhang J, Yao D, Gao K, Wang H, et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: A Randomized Multicenter Study. Gynecol Oncol (2016) 141(2):231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.06.027

14. Li W, Liu P, Zhao W, Yin Z, Lin Z, Bin X, et al. Effects of Preoperative Radiotherapy or Chemoradiotherapy on Postoperative Pathological Outcome of Cervical Cancer–From the Large Database of 46,313 Cases of Cervical Cancer in China. Eur J Surg Oncol (2020) 46(1):148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.09.188

15. He F, Li W, Liu P, Kang S, Sun L, Zhao H, et al. Influence of Uterine Corpus Invasion on Prognosis in Stage IA2-IIB Cervical Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Gynecol Oncol (2020) 158(2):273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.05.005

16. Querleu D, Morrow CP. Classification of Radical Hysterectomy. Lancet Oncol (2008) 9(3):297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70074-3

17. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours: Revised RECIST Guideline (Version 1.1). Eur J Cancer (2009) 45(2):228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

18. Serur E, Mathews RP, Gates J, Levine P, Maiman M, Remy JC. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage IB2 Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix. Gynecol Oncol (1997) 65(2):348–56. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4645

19. Landoni F, Sartori E, Maggino T, Zola P, Zanagnolo V, Cosio S, et al. Is There a Role for Postoperative Treatment in Patients With Stage Ib2-IIb Cervical Cancer Treated With Neo-Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Radical Surgery? An Italian Multicenter Retrospective Study. Gynecol Oncol (2014) 132(3):611–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.010

20. Gadducci A, Sartori E, Maggino T, Zola P, Cosio S, Zizioli V, et al. Pathological Response on Surgical Samples is an Independent Prognostic Variable for Patients With Stage Ib2-IIb Cervical Cancer Treated With Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Radical Hysterectomy: An Italian Multicenter Retrospective Study (CTF Study). Gynecol Oncol (2013) 131(3):640–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.09.029

21. Gupta S, Maheshwari A, Parab P, Mahantshetty U, Hawaldar R, Sastri Chopra S, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Radical Surgery Versus Concomitant Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy in Patients With Stage IB2, IIA, or IIB Squamous Cervical Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(16):1548–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.9985

22. Ouyang P, Cai J, Gui L, Liu S, Wu NY, Wang J. Comparison of Survival Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Therapy and Direct Surgery in IB2/IIA2 Cervical Adenocarcinoma: A Retrospective Study. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2020) 301(5):1247–55. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05505-6

23. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Cervical Cancer, Version 1 (2021). Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf (Accessed 29 June 2021).

24. Choi YS, Sin JI, Kim JH, Ye GW, Shin IH, Lee TS. Survival Benefits of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Radical Surgery Versus Radiotherapy in Locally Advanced Chemoresistant Cervical Cancer. J Korean Med Sci (2006) 21(4):683–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.4.683

25. Sun C, Tian X, Liu Z, Li W, Li P, Chen J, et al. Radiomic Analysis for Pretreatment Prediction of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: A Multicentre Study. EBioMedicine (2019) 46:160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.049

26. Huang HJ, Chang TC, Hong JH, Tseng CJ, Chou HH, Huang KG, et al. Prognostic Value of Age and Histologic Type in Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Plus Radical Surgery for Bulky (>/=4 Cm) Stage IB and IIA Cervical Carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer (2003) 13(2):204–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13004.x

27. Li P, Fang Z, Li W, Hao M, Wang W, Kang S, et al. Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy on the Postoperative Pathology of Locally Advanced Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinomas: 1:1 Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.09.013

28. Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS, Muderspach LI, Zaino RJ. A Randomized Trial of Pelvic Radiation Therapy Versus No Further Therapy in Selected Patients With Stage IB Carcinoma of the Cervix After Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol (1999) 73(2):177–83. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5387

29. Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, Lopez A, Vieira M, Ribeiro R, et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med (2018) 379(20):1895–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395

30. Ferrandina G, Gallotta V, Federico A, Fanfani F, Ercoli A, Chiantera V, et al. Minimally Invasive Approaches in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Surgery After Chemoradiotherapy: A Propensity Score Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol (2021) 28:3616–26. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09302-y

31. Gemma Kenter SG, Ignace Vergote DK, Juliusz Kobierski LM, van Doorn FL HC, Jacobus van der Velden NSR, Corneel Coens I, et al. Results From Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Surgery Compared to Chemoradiation for Stage IB2-IIB Cervical Cancer, EORTC55994. J Clin Oncol (2019) 37:5503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.5503

Keywords: cervical cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, FIGO 2018, oncological outcomes, abdominal radical hysterectomy

Citation: Li W, Zhang W, Sun L, Wang L, Cui Z, Zhao H, Wang D, Zhang Y, Guo J, Yang Y, Wang W, Bin X, Lang J, Liu P and Chen C (2021) Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Surgery Versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy Alone for Oncological Outcomes of Stage IB3 Cervical Cancer—A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Front. Oncol. 11:730753. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.730753

Received: 25 June 2021; Accepted: 27 August 2021;

Published: 13 September 2021.

Edited by:

Valerio Gallotta, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Federica Perelli, Santa Maria Annunziata Hospital, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Li, Zhang, Sun, Wang, Cui, Zhao, Wang, Zhang, Guo, Yang, Wang, Bin, Lang, Liu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunlin Chen, Y2NsMUBzbXUuZWR1LmNu; Ping Liu, bHBpdnlAMTI2LmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.