94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 27 January 2021

Sec. Hematologic Malignancies

Volume 10 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.610681

Xiaolei Wei1†

Xiaolei Wei1† Jingxia Zheng1†

Jingxia Zheng1† Zewen Zhang2

Zewen Zhang2 Qiongzhi Liu3

Qiongzhi Liu3 Minglang Zhan1

Minglang Zhan1 Weimin Huang1

Weimin Huang1 Junjie Chen1

Junjie Chen1 Qi Wei1

Qi Wei1 Yongqiang Wei1

Yongqiang Wei1 Ru Feng1*

Ru Feng1*The prognostic value of albumin changes between diagnosis and end-of-treatment (EoT) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) remains unknown. We retrospectively analyzed 574 de novo DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP from our and two other centers. All patients were divided into a training cohort (n = 278) and validation cohort (n = 296) depending on the source of the patients. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were analyzed by the method of Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazard regression model. In the training cohort, 163 (58.6%) patients had low serum albumin at diagnosis, and 80 of them were present with consecutive hypoalbuminemia at EoT. Patients with consecutive hypoalbuminemia showed inferior OS and PFS (p = 0.010 and p = 0.079, respectively). Similar survival differences were also observed in the independent validation cohort (p = 0.006 and p = 0.030, respectively). Multivariable analysis revealed that consecutive hypoalbuminemia was an independent prognostic factor OS [relative risk (RR), 2.249; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.441–3.509, p < 0.001] and PFS (RR, 2.001; 95% CI, 1.443–2.773, p < 0.001) in all DLBCL patients independent of IPI. In conclusion, consecutive hypoalbuminemia is a simple and effective adverse prognostic factor in patients with DLBCL, which reminds us to pay more attention to patients with low serum albumin at EoT during follow-up.

The introduction of rituximab into the CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) has markedly improved the outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (1, 2). Along with this, the prognostic significance of international prognostic index (IPI) was impaired and could only distinguish the low-risk with the high-risk group instead of the four risk groups as previously described (3–5). Alternatively, more and more clinical and biological markers were explored to predict the prognosis of DLBCL, including age, extranodal lesions, cell of origin, c-MYC and Bcl-2 co-expression or translocation, and different biochemical indicators (6–14). As the treatment developed, the prognostic values of these biochemical indicators may also change. It is important to find the new and simple prognostic marker to identify these DLBCL patients with different outcomes throughout the entire treatment.

Our and previous other studies showed that albumin at diagnosis could be used to predict outcome in DLBCL (15–17). Jennifer et al. reported that hypoalbuminemia may predict survival at the start of treatment prior to cycle 2, prior to cycle 4, and 4 weeks after during treatment of DLBCL with R-CHOP (18). However, the prognostic value of albumin changes between diagnosis and end-of-treatment (EoT) in DLBCL remains unknown. Therefore, we performed this study to evaluate the prognostic significance of albumin change after R-CHOP treatment in patients with DLBCL.

This multicenter, retrospective study was conducted in three centers. Patients with primary central nervous system and mediastinal lymphoma, immunodeficiency-associated tumors, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder and transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma were excluded from the study. All DLBCL patients were treated with R-CHOP regimen, and only those patients with good response after four cycles of treatment would continue to finish the planned six to eight cycles of R-CHOP treatment. Patients with poor response and progressive disease at interim would transform to second line therapy and high dose therapy with autologous stem cell rescue. A total of 574 patients consecutively diagnosed as de novo DLBCL treated with six to eight cycles of R-CHOP between 2003 and 2017 were reviewed. The training cohort consisted of 278 newly diagnosed DLBCL patients treated at Nanfang hospital, and the validation cohort included 296 DLBCL patients at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College and Changsha Central Hospital.

Clinical and treatment data were collected prospectively at different centers and reviewed retrospectively in this study. Clinical data included age, gender, height, weight, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), performance status defined by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, number of extranodal sites, disease stage according to the Ann Arbor staging system, IPI score, serum albumin at diagnosis and EoT, and complete blood cell count. GCB and non-GCB subtypes were classified according to the algorithm described by Hans et al. (19). Treatment details were also recorded in electronic medical records system. All patients gave written informed consent themselves prior to treatment allowing the use of their medical records for medical research. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University affiliated Nanfang Hospital before study initiation.

Albumin and overall survival were used as test and state variates in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and Youden index was used to determine the best cutoff value of albumin for survival analysis. Distributions of clinical characteristics between the different groups were carried out by Mann–Whitney test or Fisher’s exact test. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. OS was defined from the date of diagnosis to death from any cause or the last follow-up. PFS was defined from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease progression, relapse or death from any cause. The multivariable analysis was performed by Cox proportional hazard model. All p values were two-sided, and the significance was defined as p <0.05. Data were analyzed by the Statistical Package of Social Sciences version 13.0 for Windows.

The clinical characteristics of the 278 patients with DLBCL in the training cohort and 296 patients in the validation cohort were presented in Table S1. In our training cohort 260 (93.53%) patients achieved complete remission (CR), and 275 (92.91%) patients were CR in the validation cohort at EoT. There were no significant differences between the training cohort and validation cohort in the clinical features including gender, age, B symptoms, performance status, extranodal sites, stage, lactate dehydrogenase, cell of origin, IPI score, and albumin level at diagnosis (p > 0.05). According to ROC, the best cutoff value of albumin for survival analysis was 39.2 g/L with an area under the curve value of 0.618 ± 0.026 (p < 0.001, Figure 1). Low serum albumin was defined when albumin was less than 39.2 g/L. There were 356 patients (62.0%) with low serum albumin at the time of diagnosis, and these patients tended to present with older age (p = 0.021), poor performance status (p = 0.039), B symptoms (p < 0.011), high LDH (p < 0.001), advanced stage (p = 0.029), more extranodal sites (p = 0.034), and high IPI scores (p < 0.001). Baseline characteristics of these patients are displayed in the Table 1.

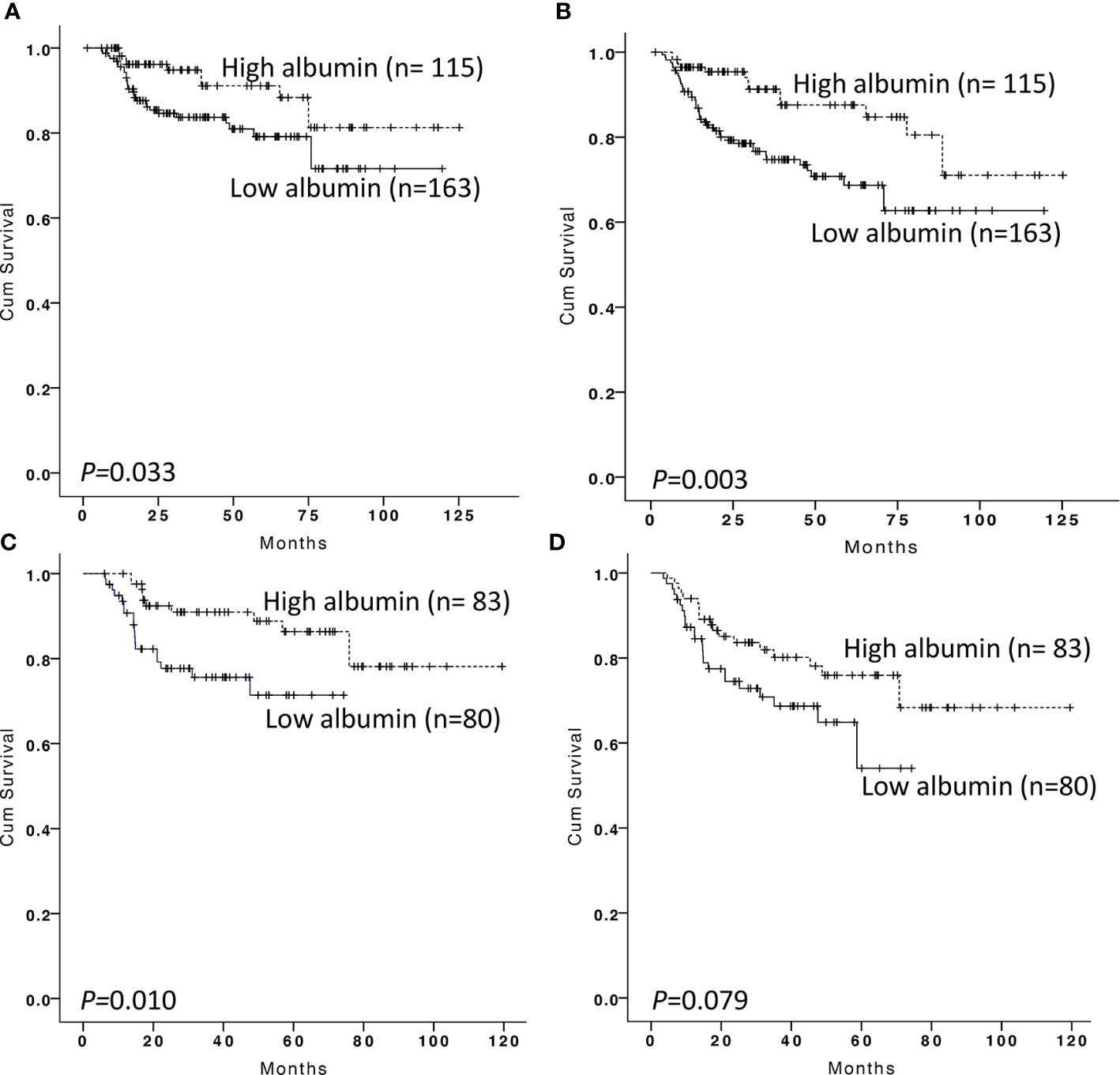

Two hundred and seventy-eight DLBCL patients were analyzed in our training cohort, and 163 of them were present with low serum albumin at the time of diagnosis. Survival analysis showed patients with low albumin showed more inferior OS and PFS than those with high albumin (p = 0.033, with 5-year OS of 79.1 ± 3.9 versus 91.1 ± 3.4%; p < 0.001, with 5-year PFS of 68.7 ± 4.5 versus 87.6 ± 3.9%, respectively, Figures 2A, B). To further investigate the clinical value of albumin changes after EoT, we explored the prognostic value of albumin change between diagnosis and EoT. The serum albumin was recovered in 83 of 163 patients after EoT, and the remaining 80 patients still had low serum albumin. The patient’s characteristics of those with serum albumin recovery vs those without were displayed in the Table S2. Our data showed patients with low albumin after EoT portended a worse OS and PFS than those with the recovery of albumin (p = 0.010, with 5-year OS of 71.4 ± 36.4 versus 86.4 ± 4.4%; p = 0.079, with 5-year PFS of 54.0 ± 11.3 versus 75.9 ± 5.3%, respectively, Figures 2C, D). Patients with albumin recovery after EoT showed no significant difference in OS and PFS compared with patients with high albumin at diagnosis (p = 0.569 and p = 0.075, respectively). The multivariable analysis revealed that low albumin after EoT was an unfavorable factor for OS [relative risk (RR), 1.959; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.020–3.763, p = 0.043) and PFS (RR, 1.731; 95% CI, 1.014–2.957, p = 0.044) independent of IPI.

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of overall survival and progression-free survival according to albumin at diagnosis and end-of treatment in the training cohort. Overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) according to albumin at diagnosis in DLBCL patients. Overall survival (C) and progression-free survival (D) according to albumin at the end of treatment in DLBCL patients with low serum albumin at diagnosis.

To validate the generalizability of the prognostic value of albumin changes in our model, 296 patients from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College and Changsha Central Hospital were used for external validation. There were 193 patients (65.2%) with low serum albumin at the time of diagnosis. Patients with low albumin at the time of diagnosis showed worse OS and PFS than those with high albumin (p = 0.021, with 5-year OS of 71.3 ± 34.7 versus 89.1 ± 3.9%; p < 0.001, with 5-year PFS of 47.2 ± 4.9 versus 74.8 ± 6.6%, respectively, Figures 3A, B). After EoT, serum albumin was recovered in 101 patients and the other 92 patients remained at the low serum albumin. We confirmed that 5-year OS and PFS in patients with low albumin after EoT were significantly lower than in those with albumin recovery (p = 0.006, with 5-year OS of 51.1 ± 9.8 versus 82.9 ± 4.6%; p = 0.030, with 5-year PFS of 30.7 ± 8.2 versus 58.8 ± 6.0%, respectively, Figures 3C, D). We also confirmed that low albumin after EoT was an unfavorable factor for OS (RR, 2.529; 95% CI, 1.372–4.659, p = 0.003) and PFS (RR, 2.153; 95% CI, 1.422–3.259, p < 0.001) independent of IPI by multivariable analysis. The multivariable survival analysis was shown in Table 2.

Figure 3 Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of overall survival and progression-free survival according to albumin at diagnosis and end-of treatment in the validation cohort. Overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) according to albumin at diagnosis in DLBCL patients. Overall survival (C) and progression-free survival (D) according to albumin at end of treatment in DLBCL patients with low serum albumin at diagnosis.

Low serum albumin at diagnosis has been identified as a simple prognostic factor in DLBCL before and after rituximab era (20, 21). One study with small sample also showed serum albumin was a stable biomarker over the course of treatment in DLBCL (18). But the prognostic value of albumin changes between diagnosis and EoT remained unknown. In this study, we retrospectively explored the prognostic value of albumin changes after R-CHOP regimen treatment in DLBCL patients and confirmed our results in another validation cohort. Our data showed low serum albumin at diagnosis and after EoT was associated with poor outcome, and albumin recovery after treatment implied superior survival.

The cutoff value of serum albumin level in our study was 39.2 g/L defined by ROC, which falls into the normal range of our hospital. According to serum albumin level, 58.6% of patients had a low serum albumin, and almost half of them still remained at the low serum albumin at EoT. Those patients showed poor OS and PFS compared with those with high serum albumin at diagnosis and EoT. We also explored the prognostic value of delta albumin between the time of diagnosis and EoT. Our data showed when albumin increased by more than 4.5 g/L after EoT, the patients with low albumin at diagnosis showed superior survival in both the training and validation cohorts (p = 0.001 and 0.001), but not in the patients with high albumin at diagnosis (p = 0.665 and 0.400) (data not shown). The underlying mechanisms of albumin related to the outcome of DLBCL remain unclear (22). Serum albumin level may be a surrogate of poor nutritional and inflammatory status as well as an aggressive tumor behavior (23–25). In our study, hypoalbuminemia was associated with more extranodal sites, advanced stage, high lactate dehydrogenase and also poor performance status and B symptoms, but not with the number of chemotherapy cycles. This indicated that hypoalbuminemia may be driven by the aggressive tumor behavior and inflammatory status rather than by poor nutritional status. Patients with albumin recovery at EoT may imply good disease control and hence outcome.

The major limitation of this study is its retrospective nature (22), which may introduce inherent selection bias by recruiting DLBCL patients who were diagnosed and followed at tertiary medical centers. To minimize the inherent biases of the retrospective study and ensure the homogeneity of treatment, we included only patients with de novo DLBCL treated with R-CHOP and excluded patients with primary central nervous system and mediastinal lymphoma, immunodeficiency-associated tumors, transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, which might result in a selection bias. Despite these limitations, our results were validated in the validation cohort from different centers, which may improve reliability of our findings. As opposed to dynamic monitoring circulating tumor cells or DNA (26), serum albumin level has the advantages of ease of use, ready availability, and low cost.

In summary, we explored the prognostic value of albumin changes in patients with DLBCL and found low serum albumin at diagnosis and EoT was associated with poor outcome. Consecutive hypoalbuminemia is a simple and effective prognostic factor in DLBCL patients. Although the hypothesis requires more evidence to support, this reminds us to pay more attention to patients with low serum albumin at EoT during follow up.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Southern Medical University affiliated Nanfang Hospital before study initiation. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RF and XW designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data. JZ, ZZ, QL, MZ, WH, JC, QW, and YW collected data. RF and XW analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Outstanding Youth Development Scheme of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (Grant No. 2019J011), National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province and Guangzhou City (Grant No. 2018A030313083 and 201804010351).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.610681/full#supplementary-material

1. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. New Engl J Med (2002) 346:235–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795

2. Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood (2010) 116:2040–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246

3. Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Hoskins P, et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood (2007) 109:1857–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257

4. Ruppert AS, Dixon JG, Salles G, Wall A, Cunningham D, Poeschel V, et al. International prognostic indices in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a comparison of IPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI. Blood (2020) 135:2041–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002729

5. International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. New Engl J Med (1993) 329:987–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402

6. Hedström G, Hagberg O, Jerkeman M, Enblad G. The impact of age on survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma - a population-based study. Acta Oncol (Stockholm Sweden) (2015) 54:916–23. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.978367

7. Kaplan D. Anatomical site as a parameter in the predictive model of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Leukemia Res (2019) 76:112–3. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2018.11.005

8. Abdulla M, Hollander P, Pandzic T, Mansouri L, Ednersson SB, Andersson PO, et al. Cell-of-origin determined by both gene expression profiling and immunohistochemistry is the strongest predictor of survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol (2020) 95:57–67. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25666

9. Xu J, Liu JL, Medeiros LJ, Huang W, Khoury JD, McDonnell TJ, et al. MYC rearrangement and MYC/BCL2 double expression but not cell-of-origin predict prognosis in R-CHOP treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol (2020) 104:336–43. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13384

10. Wei X, Xu M, Wei Y, Huang F, Zhao T, Li X, et al. The addition of rituximab to CHOP therapy alters the prognostic significance of CD44 expression. J Hematol Oncol (2014) 7:34. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-34

11. Yang J, Guo X, Hao J, Dong Y, Zhang T, Ma X. The Prognostic Value of Blood-Based Biomarkers in Patients With Testicular Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Front Oncol (2019) 9:1392. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01392

12. Miao Y, Medeiros LJ, Xu-Monette ZY, Li J, Young KH. Dysregulation of Cell Survival in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Front Oncol (2019) 9:107. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00107

13. Roh J, Jung J, Lee Y, Kim SW, Pak HK, Lee AN, et al. Risk Stratification Using Multivariable Fractional Polynomials in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Front Oncol (2020) 10:329. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00329

14. Peyrade F, Jardin F, Thieblemont C, Thyss A, Emile JF, Castaigne S, et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol (2011) 12:460–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70069-9

15. Wei Y, Wei X, Huang W, Song J, Zheng J, Zeng H, et al. Albumin improves stratification in the low IPI risk patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol (2020) 111:681–5. doi: 10.1007/s12185-020-02818-9

16. Zhou Q, Wei Y, Huang F, Wei X, Wei Q, Hao X, et al. Low prognostic nutritional index predicts poor outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Int J Hematol (2016) 104:485–90. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2052-9

17. Bairey O, Shacham-Abulafia A, Shpilberg O, Gurion R. Serum albumin level at diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an important simple prognostic factor. Hematol Oncol (2016) 34:184–92. doi: 10.1002/hon.2233

18. Eatrides J, Thompson Z, Lee JH, Bello C, Dalia S. Serum albumin as a stable predictor of prognosis during initial treatment in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol (2015) 94:357–8. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2150-9

19. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood (2004) 103:275–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545

20. Dalia S, Chavez J, Little B, Bello C, Fisher K, Lee JH, et al. Serum albumin retains independent prognostic significance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the post-rituximab era. Ann Hematol (2014) 93:1305–12. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2031-2

21. Melchardt T, Troppan K, Weiss L, Hufnagl C, Neureiter D, Tränkenschuh W, et al. A modified scoring of the NCCN-IPI is more accurate in the elderly and is improved by albumin and β2 -microglobulin. Br J Haematol (2015) 168:239–45. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13116

22. Go SI, Kim HG, Kang MH, Park S, Lee GW. Prognostic model based on the geriatric nutritional risk index and sarcopenia in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer (2020) 20:439. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06921-2

23. McMillan DC, Watson WS, O’Gorman P, Preston T, Scott HR, McArdle CS. Albumin concentrations are primarily determined by the body cell mass and the systemic inflammatory response in cancer patients with weight loss. Nutr Cancer (2001) 39:210–3. doi: 10.1207/S15327914nc392_8

24. Bland KA, Zopf EM, Harrison M, Ely M, Cormie P, Liu E, et al. Prognostic Markers of Overall Survival in Cancer Patients Attending a Cachexia Support Service: An Evaluation of Clinically Assessed Physical Function, Malnutrition and Inflammatory Status. Nutr Cancer (2020) 1–11. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1800765

25. Guner A, Kim HI. Biomarkers for Evaluating the Inflammation Status in Patients with Cancer. J Gastric Cancer (2019) 19:254–77. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2019.19.e29

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, albumin, survival, change, outcome

Citation: Wei X, Zheng J, Zhang Z, Liu Q, Zhan M, Huang W, Chen J, Wei Q, Wei Y and Feng R (2021) Consecutive Hypoalbuminemia Predicts Inferior Outcome in Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 10:610681. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.610681

Received: 26 September 2020; Accepted: 07 December 2020;

Published: 27 January 2021.

Edited by:

Stefano Luminari, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, ItalyReviewed by:

Raul Cordoba, University Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz, SpainCopyright © 2021 Wei, Zheng, Zhang, Liu, Zhan, Huang, Chen, Wei, Wei and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ru Feng, cnV0aDE2MjZAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.