- Department of Biochemistry, Center of Excellence in Molecular Biology and Regenerative Medicine (CEMR), Jagadguru Sri Shivarathreeshwara (JSS) Medical College, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru, India

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) is a highly aggressive cancer with mortality running parallel to its incidence and has limited therapeutic options. Chronic liver inflammation and injury contribute significantly to the development and progression of HCC. Several factors such as gender, age, ethnicity, and demographic regions increase the HCC incidence rates and the major risk factors are chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), carcinogens (food contaminants, tobacco smoking, and environmental toxins), and inherited diseases. In recent years evidence highlights the association of metabolic syndrome (diabetes and obesity), excessive alcohol consumption (alcoholic fatty liver disease), and high-calorie intake (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) to be the prime causes for HCC in countries with a westernized sedentary lifestyle. HCC predominantly occurs in the setting of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (80%), however, 20% of the cases have been known in patients with non-cirrhotic liver. It is widely believed that there exist possible interactions between different etiological agents leading to the involvement of diverse mechanisms in the pathogenesis of HCC. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of HCC development and progression is imperative in developing effective targeted therapies to combat this deadly disease. Noteworthy, a detailed understanding of the risk factors is also critical to improve the screening, early detection, prevention, and management of HCC. Thus, this review recapitulates the etiology of HCC focusing especially on the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)- and alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD)-associated HCC.

Introduction

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) is a serious public health issue and the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide (1, 2). HCC accounts for about 80% of the primary liver cancer while the other types include cholangiocarcinoma (10–20%) and angiosarcoma (1%) (3). There is a striking variation in HCC incidence rates across geographic regions and at the global level, each year over 800,000 people are diagnosed with liver cancer (4, 5). HCC cases are highest in Eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, followed by intermediate rates in Southern and Western European countries, North and Central America, and the lowest incidence rates are observed in and Northern Europe and South Central Asia (6, 7). HCC predominantly affects men more than women (two to four times higher in men) with its highest incidence in the age group of 45–65 years (8, 9). According to Globocan 2018, HCC is the fifth most common cancer in men and the ninth most commonly occurring cancer in women (10). The overall ratio of mortality to incidence is 0.95 and reflects the poor prognosis of HCC (11).

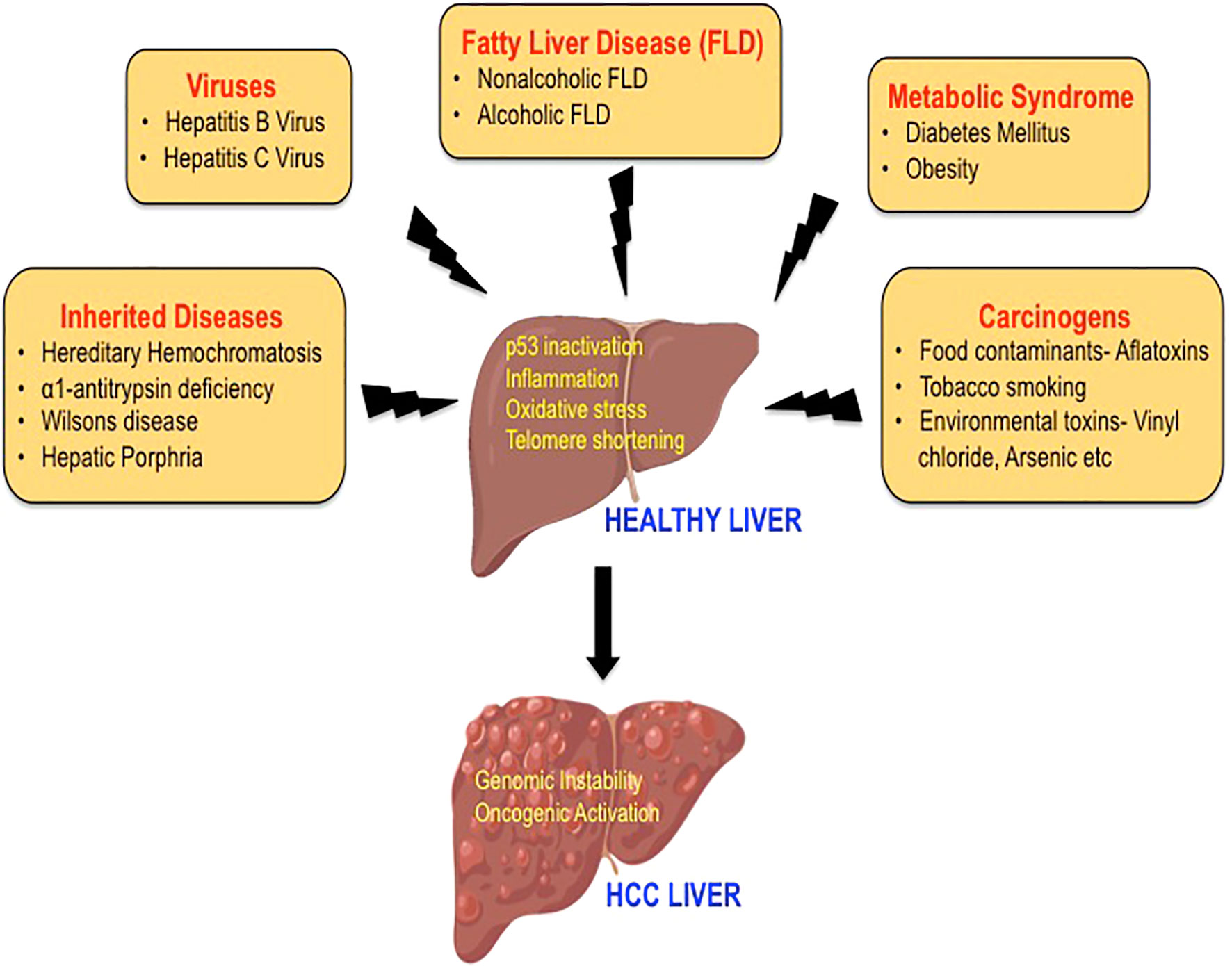

HCC is an extremely complex condition and there are multiple factors involved in the etiology of HCC. The major risk factors for HCC include hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), diabetes, obesity, alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Additional risk factors that are also known to increase the incidence of HCC are tobacco smoking, food contaminants such as aflatoxins, familial or genetic factors, and various environmental toxins that act as carcinogens (12–14) (Figure 1). The development of HCC is initiated by hepatic injury involving inflammation leading to necrosis of hepatocytes and regeneration. This chronic liver disease sequentially transitions to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (15, 16). HCC that often occurs in the setting of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis is diagnosed late in its course and liver transplantation is the best option for patients at this stage (12, 17). Multiple treatment options are available to treat HCC including surgical resection, local ablation with radiofrequency, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radioembolization, and systemic targeted agents like sorafenib depending on the tumor extent or underlying liver dysfunction (12, 14, 18). Furthermore, the viable treatment options offered to the patients also depend on the causative agent of HCC as they define the disease course and patient characteristics. However, with the improved treatment for HCC, the demographic landscape has changed (6, 19). In this mini-review, we aim to describe the traditional risk factors in brief and highlight on fatty liver disease, which is the emerging etiological risk factor contributing to the increasing incidences of HCC.

Figure 1 The etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. A variety of risk factors have been associated with the development of HCC, including hepatitis viruses, carcinogens, heredity diseases, metabolic syndrome, and fatty liver disease. The mechanisms by which these etiological factors may induce hepatocarcinogenesis mainly include p53 inactivation, inflammation, oxidative stress, and telomere shortening leading to genomic instability and activation of multiple oncogenic signaling pathways.

Virus and HCC

The chronic infection by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the traditional risk factors that are associated with HCC for 33,600 years and 1,000 years, respectively (20, 21). The virus-associated mechanisms driving hepatocarcinogenesis are complex and cause liver cirrhosis, which progresses to HCC in about 80–90% of the cases (15, 22).

HBV is partially a double-stranded circular DNA virus, which belongs to the genus Avihepadnavirus of the Hepadnaviridae family. HBV infection accounts for 75–80% of virus-associated HCC and infects over 240 million people around the world (23). The incorporation of the genetic material of this virus into the human genome causes p53 inactivation, inflammation, or oxidative stress, which causes hepatocarcinogenesis (24, 25). HBV-induced HCC can be both cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic and involves an array of processes such as proliferation and loss of growth control (caused by p53 inactivation), sustained cycles of necrosis and regeneration (resultant of inflammation), and activation of various oncogenic pathways such PI3K/Akt/STAT3 pathway and Wnt/β-catenin (induction of oxidative stress), all of which leads to genomic instability (26, 27).

Contrary to HBV, the Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a non-integrating, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Hepacivirus of the Flaviviridae family. HCV infects over 57 million people worldwide and accounts for 10–20% of virus-associated HCC (28, 29). Unlike HBV infection, there is no integration of genetic material into the host’s genome by the HCV virus. It is the HCV proteins (structural and non-structural proteins) that play a critical role in the development of HCC (30). HCV-induced hepatocarcinogenesis is highly complex involving the activation of multiple cellular pathways and gets initiated by the establishment of HCV infection leading to chronic hepatic inflammation, which further progresses to liver cirrhosis and HCC development (31). HCV proteins either directly or indirectly modulate a wide range of host cellular activities, including transcriptional regulation, cytokine modulation, hepatocyte growth regulation, and lipid metabolism that lead to chronic liver injury. In addition to inducing oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, HCV proteins are also known to cause epigenetic alterations by modulating micro RNA (miRNA) and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) in the host cells (32). Thus, HCV shows a high propensity (60–80%) to induce chronic infection and promotes liver cirrhosis 10–20 fold higher than HBV. The angiogenic and metastatic pathways activated by HCV further promote hepatocytes’ malignant transformation and accelerate HCC development (33). Hepatitis D virus (HDV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are also considered as modulators of HCC (14).

Carcinogens and HCC

In addition to hepatitis viruses, chemical carcinogens also play important roles in the etiology of HCC (34). Exposure to carcinogens including aflatoxins, tobacco smoking, vinyl chloride, arsenic, and various other chemicals act either independently or in combination with viruses to cause DNA damage, induce liver cirrhosis, and contribute to HCC (35).

Aflatoxin is a potent liver carcinogen produced by the Aspergillus fungus, which is found to contaminate foodstuffs such as peanuts, corn, soya beans stored in damp conditions. This mycotoxin induces mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene and causes uninhibited growth of liver cells leading to the development of HCC (36, 37). It is reported that the chemicals in tobacco smoke (4-aminobiphenyl and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), areca nut (nitrosamines), and betel leaves (safrole) cause hepatotoxicity (13, 35). Besides, studies have demonstrated that the human exposure to groundwater contaminants (chemicals such as cadmium, lead, nickel, arsenic), organic solvents (toluene, dioxin, xylene), and chemicals such as vinyl chloride and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) have shown to increase the risk of HCC as they exert hepatocarcinogenic effect via induction of oxidative stress and telomere shortening (34, 38).

Inherited Diseases and HCC

Certain metabolic disorders such as hereditary hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, and hepatic porphyria are associated with high risk for the development of HCC. These hereditary diseases are known to promote hepatocarcinogenesis as a result of increased inflammation and hepatocellular damage (39–41).

Metabolic Syndrome and HCC

Diabetes mellitus, a component of the metabolic syndrome has been shown to attribute about 7% of the HCC cases worldwide (5, 42). Meta-analyses have shown that diabetes is associated with HCC independent of viral hepatitis in which diabetic patients show 2-3 fold greater risks in developing HCC compared with non-diabetic controls (43). The pathophysiological conditions such as hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and activation of insulin-like growth factor signaling pathways provide a strong association for diabetes to be the risk factor in the pathogenesis of HCC (5, 44). Obesity, a pathological state characterized by insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and inflammation is also closely associated with HCC (45). It is demonstrated that increased reactive oxygen species, dysregulated adipokines, and adipose tissue remodeling, alteration of gut microbiota, and dysregulated microRNA increases the relative risk of HCC in obese patients (46–48). Accordingly, obesity is one of the common causes of NAFLD, which is also an underlying risk factor of HCC (46).

Fatty Liver Disease and HCC

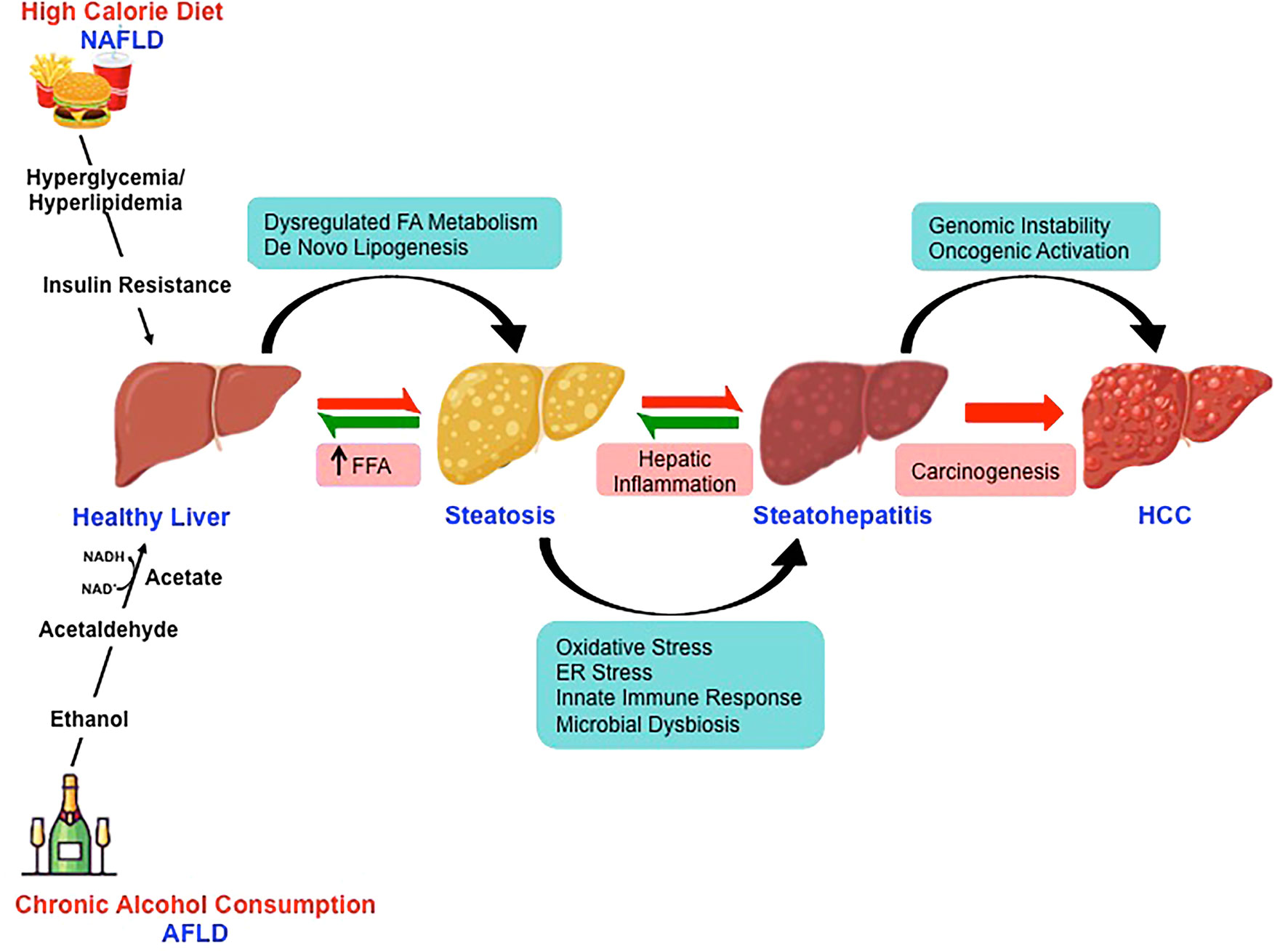

Over the last decade, fatty liver disease is emerging as the leading etiologies for chronic liver disease progressing to HCC (49). The changing scenario is attributed to improved antiviral therapy for virus-related HCC (50). With the growing inclination towards western dietary pattern, sociocultural changes and the lifestyle with limited or no physical activity has sharply increased the incidence rates of NAFLD- and AFLD-associated HCC across the continents (51, 52). The pathological spectra of liver injury in promoting HCC development are similar in these two fatty liver diseases despite having divergent pathogenic origin with yet some key distinct features (Figure 2). Furthermore, a high-calorie diet and ethanol act synergistically at multiple levels potentiating hepatocarcinogenesis (53).

Figure 2 Molecular mechanisms involved in nonalcoholic- and alcoholic-associated HCC. High-calorie diet and excessive alcohol consumption is the major risk factor for the development of NAFLD and AFLD respectively. Despite the divergent pathogenic origin, the pathological spectra of liver injury in promoting HCC development in NAFLD and AFLD share common molecular pathways.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)-Associated HCC

NAFLD is characterized by excessive hepatic lipid accumulation (steatosis), which further transitions to steatohepatitis upon the inflammatory insult, to cirrhosis and HCC (54, 55). It’s a pathophysiological condition that is not associated with excess alcohol consumption or other secondary causes such as viral infection and heredity liver diseases (56). NAFLD is classically associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (57, 58).

A meta-analysis by Younossi et al. (86 studies from 22 countries carried out between 1989 and 2015) reported that the worldwide prevalence of NAFLD is 25.24% (59). The prevalence of NAFLD varies across the continent with the highest in the Middle East (31.79%) followed by South America (30.45%), Asia (27.37%), North America (24.13%), Europe (23.71%), and Africa (13.48%) (51, 60). Studies also indicate that NAFLD is more common in men (42% for white males vs. 24% for white females) and the prevalence of NAFLD increases with age (61, 62). However, as obesity increases in children and adolescents, there is an increasing prevalence of NAFLD and NAFLD-associated HCC compared to adults (63, 64). While studies have shown that NAFLD accounts for about 13% of HCC cases, Wong et al., have reported that NAFLD is the fastest-growing etiology, which is indicative of liver transplantation in HCC patients (65). Studies from long term follow up of non-alcoholic fatty liver patients have shown the prevalence of HCC to be 0.5 and 2.8% in NAFLD and NASH respectively (66, 67). It is interesting to note that 80% of HCC patients have cirrhosis (68). However, HCC is also reported in non-cirrhotic NASH (69). Thus, with the rise in the incidence of NAFLD-associated HCC in recent years, the contribution of NAFLD is underscored among the risk factors that induce HCC (70).

Emerging evidence has established multiple risk factors for NAFLD-associated HCC including obesity, diabetes, iron deposition, genetic and epigenetic factors, microRNA, and gut microbiota (49, 71). In the modern era with a sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy dietary habits, obesity is rapidly increasing and has been established as a risk factor for HCC (56). It is been reported to increase the risk by 1.5–4 times either by contributing to the development of NAFLD or by directly exerting carcinogenic effect leading to HCC (72). Albeit most patients with NAFLD are obese in the western countries, lean NAFLD has also been reported from Asian countries (73). Furthermore, large population-based cohort studies have found that diabetes mellitus is associated with 1.8–4 fold increased risk of HCC (74). Along the same line, a study by Turati et al. reported that the combined effect of diabetes and obesity among the metabolic syndrome was positively associated with HCC risk (75). Excessive iron deposit in the liver is thought to be a risk factor for NAFLD-HCC (76). Indeed, experimental studies by Paola et al., demonstrated that hepatic iron overload might be associated with HCC development in NASH patients (77). Additionally, genetic factors are known to increase the risk of HCC in NAFLD such as the PNPLA3 I148M variant and rs58542926 (E167K) variant in TM6SF2 (78, 79). Studies carried out in mouse models of NAFLD and also in patients with NAFLD or HCC have identified epigenetic-mediated gene regulation involved in the development and progression of the disease (80, 81). Among the various risk factors, the gut microbiota has emerged as an important contributor to NAFLD-associated HCC (82).

The mechanism of NAFLD-associated HCC progression is complex. Hepatic lipid accumulation as a result of high-calorie intake (high carbohydrate and high dietary fat) and low physical activity in the absence of excessive alcohol consumption is a major contributor to the onset of NAFLD development (56). Steatosis progresses to necroinflammation leading to hepatocarcinogenesis as a consequence of multiple parallel acting conditions such as insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, adipose tissue remodeling, oxidative/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, altered immune system, genetic alterations, and dysbiosis in the gut microbiome. These modifications in association with genetic factors and epigenetic changes activate oncogenic signaling and promote HCC development (83). Insulin resistance leads to increased release of free fatty acids (FFA) and release of various inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), leptin, and resistin. This is also accompanied by decreased amounts of adiponectin (84). Insulin resistance along with hyperinsulinemia up-regulates insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), a growth stimulator aiding hepatocyte proliferation and apoptosis inhibition (85, 86).

Furthermore, hepatic lipotoxicity due to insulin resistance leads to imbalanced energy metabolism. Elevated FFAs β-oxidation induces oxidative stress through the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) eventually leading to mitochondrial dysfunction accompanied by ER stress (87, 88). There exists a potent cross talk between oxidative/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and apoptotic pathways along with inflammatory cytokines, innate and adaptive immune responses that significantly contribute to NASH progression to HCC (83). Further, the oxidative stress promotes tumorigenesis by activation of c-Jun amino-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1), a mitogen-activated protein kinase, and by suppressing the action of p53 tumor suppressor gene and nuclear respiratory factor 1 (Nrf1) (89). Interestingly, studies have confirmed the potential role of immune cells such as CD8+, CD4+ T lymphocytes, and Kupffer cells in NASH progression with altered intestinal gut microbiome being one of the contributors (90, 91). Thus, the molecular connection between regulations of hepatocyte cell cycle and energy balance is the key driving force of NAFLD-associated HCC.

Unfortunately, there is yet no FDA-approved drug for the effective treatment of NAFLD and NAFLD-HCC. A better understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms will open up treatment options for HCC subjects with NAFLD etiology. Dietary and lifestyle modifications being the mainstay of disease management need to be tailored to meet individual patients’ needs. Furthermore, knowing the co-morbidities of NAFLD-HCC will aid in designing effective treatment strategies that can be employed in clinical practice.

Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (AFLD)-Associated HCC

As the name suggests, AFLD is attributed to excessive alcohol consumption that causes hepatic injury by the build-up of fats, inflammation, and scarring leading to HCC, which could be fatal (92). Globally, the prevalence of AFLD is increasing and has become a significant contributor to the liver disease burden accounting for 30% of HCC related deaths (93). The “safe” levels of drinking as defined in the dietary guidelines in the United States is two drinks for men and one drink for women per day as one alcoholic drink (12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1 ounce of hard liquor) accounts for about 14 g of alcohol (defined as standard drink by WHO) (53). By contrast, excessive alcohol consumption (more than 14 drinks/week and 7 drinks/week for men and women respectively) is considered to cause AFLD (51). The threshold level of alcohol intake causing hepatotoxic effect varies and it depends on a variety of factors such as gender, ethnicity, and genetics (94).

A large population-based prospective study conducted by Becker et al., for 12 years have provided evidence that females are more susceptible to the toxic effects of alcohol than male for any given level of alcohol intake (95). The possible mechanisms include lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) activity in females and estrogen levels that activate Kupffer cells due to increased gut permeability and portal endotoxin levels leading to alcohol-induced liver injury (96, 97). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that in the United States, compared to Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics drinkers have a two-fold increase in liver enzymes (98). Since there is no significant difference among other ethnic groups, factors such as polymorphism of genes associated with alcohol metabolism (ADH, CYP2E1) and antioxidant enzymes and genes coding for cytokines are also investigated in association with alcoholic liver disease (99). However, it remains critical to consider factors such as amount and type of alcohol consumption and socioeconomic status with the development of AFLD.

As per the global status report on alcohol and health, 2018, there are 2.3 billion active drinkers worldwide (100). In America, Europe, and Western Pacific more than half of the population account for active alcoholics. Though the percentage of drinkers has decreased in Africa and America, there is an increase observed in the Western Pacific region and has remained stable in the regions of Southeast Asia (101). Alcohol is one of the commonest causes of chronic liver disease with nearly 75 million diagnosed for the risk of AFLD and contributes to 50% of mortality related to cirrhosis (102). According to the global health report on alcohol and health, 2018 by World Health Organization (WHO), the alcohol-attributable deaths (AAD) from liver cirrhosis varies across the countries. The top five in the list includes India (Safe limits: ≤16 g/day for men and ≤8 g/day for women, Comparison of international alcohol drinking guidelines, 2019), China (Safe limits: ≤25 g/day for men and ≤15 g/day for women, Chinese Dietary Guidelines, 2016), Nigeria (Safe limits: no written national policy, WHO, 2018), United States (Safe limits: ≤24 g/day for men and ≤14 g/day for women, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020), and Russia (Safe limits: ≤30 g/day for men and ≤20 g/day for women, Prevention of alcohol and drug use, National Medicine Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine). It is also reported that liver cancer (22.5%) is the largest contributor to the burden of alcohol-attributable cancer DALY (disability-adjusted life year), followed by colorectal (20.6%) and esophageal (18.5%) cancers (100). The global HCC BRIDGE study by Park et al. reported that AFLD contributes to HCC development to a large portion in Europe (37%) and North America (21%) compared to East Asia (4–13%) (103). Furthermore, progression to cirrhosis and mortality is higher in patients with AFLD (36%) compared to NAFLD (7%) (104) and studies have reported that AFLD accounts for 10.3% of HCC in liver transplantation candidates (105). It is noteworthy that there is a synergy between excessive alcohol consumption with other risk factors including diabetes mellitus and viral hepatitis (106).

Despite the differences in the epidemiological and clinical characteristics, AFLD-associated HCC shares a similar mechanism of HCC pathogenesis with that of NAFLD. Acetaldehyde, an oxidation product of ethanol is a potent carcinogen driving the tumorigenesis by the formation of DNA adducts (106). Although the major pathway of metabolizing ethanol involves CYP2E1 in microsomes, acetaldehyde, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are formed nevertheless (107). Interestingly, ethanol also induces steatosis by elevating the enzyme levels of de novo lipogenesis (DNL) and by suppressing the oxidation of fatty acid by downregulating PPARα (108, 109). In addition, progressive alterations in PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 genes, and micro RNA are known to promote steatosis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis in AFLD (110, 111). Thus similar to NAFLD-associated HCC, alcohol induces cirrhosis and promotes HCC development via the production of ROS, induction of chronic inflammation, activation of the immune response, leaky gut, and alteration of gene expression. However, the infiltration of inflammatory cells is found to be higher in AFLD (105, 112).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

HCC is a highly fatal cancer driven by multiple etiological factors, among which, fatty liver disease is emerging as a major cause worldwide. Based on the pathogenic origin, NAFLD has been strongly associated with glucose and lipid metabolism, whereas AFLD has been associated with a strong inflammatory response. NAFLD and AFLD share common molecular mechanisms in promoting HCC development, which involves vicious interplay between various pathways including immunological pathways, endocrine pathways, and metabolic pathways. However, there still exists a gap in the knowledge in understanding the molecular mechanisms of inflammation, genetic and epigenetic regulations, and genomic instability leading to hepatocarcinogenesis. Indeed, a comprehensive understanding of these diseases would aid in the identification of biomarkers and therapeutic targets leading to early detection and management.

Albeit, NAFLD- and AFLD-associated HCC are major challenging public health issues, it is preventable. The widely implemented curative approach is lifestyle alteration involving modifications in dietary habits and improving physical activity in case of NAFLD and alcohol abstinence in AFLD. Further personalized treatment strategies could improve healthcare and quality of patient care, thereby reducing the mortality rate. Alternatively, strategies like pharmacological treatment and bariatric surgery are also considered in patients unresponsive to lifestyle changes. Conclusively, it is important to develop diagnostic tests for the detection of early stages of HCC.

Author Contributions

DS and DPK devised and wrote the manuscript. AS and DPK made the figures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship to DPK from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. Cancer today (2018). Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home.

2. Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2019) 380:1450–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263

3. Zhu RX, Seto WK, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific Region. Gut Liver (2016) 10:332–39. doi: 10.5009/gnl15257

4. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer (2019) 144:1941–53. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937

5. Thylur RP, Roy SK, Shrivastava A, LaVeist TA, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. Assessment of risk factors, and racial and ethnic differences in hepatocellular carcinoma. JGH Open (2020) 4:351–59. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12336

6. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, London WT. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clin Liver Dis (2015) 19:223–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.01.001

7. Sagnelli E, Macera M, Russo A, Coppola N, Sagnelli C. Epidemiological and etiological variations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Infection (2020) 48:7–17. doi: 10.1007/s15010-019-01345-y

8. Wands J. Hepatocellular carcinoma and sex. N Engl J Med (2007) 357:1974–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr075652

9. Mittal S, Kramer JR, Omino R, Chayanupatkul M, Richardson PA, El-Serag HB, et al. Role of Age and Race in the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Veterans With Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol (2018) 16:252–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.042

10. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2018) 68:394–24. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

11. Njei B, Rotman Y, Ditah I, Lim JK. Emerging trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and mortality. Hepatology (2015) 61:191–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.27388

12. Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y

13. Sanyal AJ, Yoon SK, Lencioni R. The etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and consequences for treatment. Oncologist (2010) 4:14–22. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-14

14. Jindal A, Thadi A, Shailubhai K. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Etiology and Current and Future Drugs. J Clin Exp Hepatol (2019) 2:221–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.01.004

15. Kanda T, Goto T, Hirotsu Y, Moriyama M, Omata M. Molecular Mechanisms Driving Progression of Liver Cirrhosis towards Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B and C Infections: A Review. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20:1358. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061358

16. Kovalic AJ, Cholankeril G, Satapathy SK. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease: metabolic diseases with systemic manifestations. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 4:65. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.08.09

17. Fuks D, Dokmak S, Paradis V, Diouf M, Durand F, Belghiti J. Benefit of initial resection of hepatocellular carcinoma followed by transplantation in case of recurrence: an intention-to-treat analysis. Hepatology (2012) 55:132–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.24680

18. Wege H, Li J, Ittrich H. Treatment Lines in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Visc Med (2019) 35:266–72. doi: 10.1159/000501749

19. Ozcan M, Altay O, Lam S, Turkez H, Aksoy Y, Nielsen J, et al. Improvement in the Current Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using a Systems Medicine Approach. Adv Biosyst (2020) 4:e2000030. doi: 10.1002/adbi.202000030

20. Paraskevis D, Magiorkinis G, Magiorkinis E, Ho SY, Belshaw R, Allain JP, et al. Dating the origin and dispersal of hepatitis B virus infection in humans and primates. Hepatology (2013) 57:908–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.26079

21. Simmonds P. Reconstructing the origins of human hepatitis viruses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci (2001) 356:1013–26. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0890

22. Yang JD, Kim WR, Coelho R, Mettler TA, Benson JT, Sanderson SO, et al. Cirrhosis is present in most patients with hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol (2011) 9:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.08.019

23. Gowans EJ, Burrell CJ, Jilbert AR, Marmion BP. Patterns of single- and double-stranded hepatitis B virus DNA and viral antigen accumulation in infected liver cells. J Gen Virol (1983) 64:1229–39. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-6-1229

24. Jiang Z, Jhunjhunwala S, Liu J, Haverty PM, Kennemer MI, Guan Y, et al. The effects of hepatitis B virus integration into the genomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Genome Res (2012) 22:593–601. doi: 10.1101/gr.133926.111

25. Jia L, Gao Y, He Y, Hooper JD, Yang P. HBV induced hepatocellular carcinoma and related potential immunotherapy. Pharmacol Res (2020) 159:104992. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104992

26. Neuveut C, Wei Y, Buendia MA. Mechanisms of HBV-related hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol (2010) 52:594–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.033

27. Choudhari SR, Khan MA, Harris G, Picker D, Jacob GS, Block T, et al. Deactivation of Akt and STAT3 signaling promotes apoptosis, inhibits proliferation, and enhances the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to an anticancer agent, Atiprimod. Mol Cancer Ther (2007) 6:112–21. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0561

28. Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2013) 10:553–62. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107

29. Heffernan A, Cooke GS, Nayagam S, Thursz M, Hallett TB. Scaling up prevention and treatment towards the elimination of hepatitis C: a global mathematical model. Lancet (2019) 393:1319–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32277-3

30. Banerjee A, Ray RB, Ray R. Oncogenic potential of hepatitis C virus proteins. Viruses (2010) 2:2108–33. doi: 10.3390/v2092108

31. Goossens N, Hoshida Y. Hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol (2015) 21:105–14. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.21.2.105

32. Irshad M, Gupta P, Irshad K. Molecular basis of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by hepatitis C virus infection. World J Hepatol (2017) 9:1305–14. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1305

33. Vescovo T, Refolo G, Vitagliano G, Fimia GM, Piacentini M. Molecular mechanisms of hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Microbiol Infect (2016) 10:853–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.019

34. Desai A, Sandhu S, Lai JP, Sandhu DS. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: A comprehensive review. World J Hepatol (2019) 11:1–18. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.1

35. Zhang YJ. Interactions of chemical carcinogens and genetic variation in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol (2010) 2:94–102. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i3.94

36. Shen HM, Ong CN. Mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene and ras oncogenes in aflatoxin hepatocarcinogenesis. Mutat Res (1996) 366:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1110(96)90005-6

37. Gouas D, Shi H, Hainaut P. The aflatoxin-induced TP53 mutation at codon 249 (R249S): biomarker of exposure, early detection and target for therapy. Cancer Lett (2009) 286:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.057

38. Wang LY, Chen CJ, Zhang YJ, Tsai WY, Lee PH, Feitelson MA, et al. 4-Aminobiphenyl DNA damage in liver tissue of hepatocellular carcinoma patients and controls. Am J Epidemiol (1998) 147:315–23. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009452

39. Britto MR, Thomas LA, Balaratnam N, Griffiths AP, Duane PD. Hepatocellular carcinoma arising in non-cirrhotic liver in genetic haemochromatosis. Scand J Gastroenterol (2000) 35:889–93. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023282

40. Topic A, Ljujic M, Radojkovic D. Alpha-1-antitrypsin in pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Mon (2012) 12:e7042. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.7042

41. Cheng WS, Govindarajan S, Redeker AG. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a case of Wilson’s disease. Liver (1992) 12:42–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1992.tb00553.x

42. Baecker A, Liu X, La Vecchia C, Zhang ZF. Worldwide incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma cases attributable to major risk factors. Eur J Cancer Prev (2018) 27:205–12. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000428

43. El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Javadi F. The association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol (2006) 4:369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.007

44. Singh MK, Das BK, Choudhary S, Gupta D, Patil UK. Diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: A pathophysiological link and pharmacological management. BioMed Pharmacother (2018) 106:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.095

45. Sun B, Karin M. Obesity, inflammation, and liver cancer. J Hepatol (2012) 56:704–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.020

46. Karagozian R, Derdák Z, Baffy G. Obesity-associated mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Metabolism (2014) 63:607–17. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.01.011

47. Loo TM, Kamachi F, Watanabe Y, Yoshimoto S, Kanda H, Arai Y, et al. Gut Microbiota Promotes Obesity-Associated Liver Cancer through PGE2-Mediated Suppression of Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov (2017) 7:522–38. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0932

48. Marengo A, Rosso C, Bugianesi E. Liver Cancer: Connections with Obesity, Fatty Liver, and Cirrhosis. Annu Rev Med (2016) 67:103–17. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-090514-013832

49. Pocha C, Xie C. Hepatocellular carcinoma in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-one of a kind or two different enemies? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 4:72. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2019.09.01

50. Colombo M, Lleo A. The impact of antiviral therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology. Hepat Oncol (2018) 5:HEP03. doi: 10.2217/hep-2017-0024

51. Ntandja Wandji LC, Gnemmi V, Mathurin P, Louvet A. Combined alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. JHEP Rep (2020) 23:100101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100101

52. Romero-Gómez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol (2017) 67:829–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.016

53. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease to the Burden of Liver-Related Morbidity and Mortality. Gastroenterology (2016) 150:1778–85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.005

54. Nakagawa H, Hayata Y, Kawamura S, Yamada T, Fujiwara N, Koike K. Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) (2018) 10:447. doi: 10.3390/cancers10110447

55. Sunny NE, Bril F, Cusi K. Mitochondrial Adaptation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Novel Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2017) 28:250–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.11.006

56. Huang TD, Behary J, Zekry A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and management. Intern Med J (2019) 24:1038–47. doi: 10.1111/imj.14709

57. Liu K, McCaughan GW. Epidemiology and Etiologic Associations of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Associated HCC. Adv Exp Med Biol (2018) 1061:3–18. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8684-7

58. Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2011) 34:274–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724

59. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology (2016) 64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431

60. Sayiner M, Koenig A, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the United States and the Rest of the World. Clin Liver Dis (2016) 20:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.001

61. Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology (2004) 40:1387–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466

62. Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology (2006) 43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973

63. Nobili V, Alisi A, Newton KP, Schwimmer JB. Comparison of the Phenotype and Approach to Pediatric vs Adult Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology (2016) 150:1798–810. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.009

64. Nobili V, Carpino G, Alisi A, Franchitto A, Alpini G, De Vito R, et al. Hepatic progenitor cells activation, fibrosis, and adipokines production in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology (2012) 56:2142–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.25742

65. Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology (2015) 148:547–55. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039

66. Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Anglulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology (2005) 129:113–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014

67. Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, Thorelius L, Holmqvist M, Bodemar G, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology (2006) 44:865–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.21327

68. Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet (2012) 379:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0

69. Lee DH, Lee JM. Primary malignant tumours in the non-cirrhotic liver. Eur J Radiol (2017) 95:349–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.08.030

70. Campani C, Bensi C, Milani S, Galli A, Tarocchi M. Resection of NAFLD-Associated HCC: Patient Selection and Reported Outcomes. J Hepatocell Carcinoma (2020) 7:107–16. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S252506

71. Gupta H, Youn GS, Shin MJ, Suk KT. Role of Gut Microbiota in Hepatocarcinogenesis. Microorganisms (2019) 7:121. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7050121

72. El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Obesity and hepatocellular carcinoma: hype and reality. Hepatology (2014) 60:779–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.27172

73. Albhaisi S, Chowdhury A, Sanyal AJ. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals. JHEP Rep (2019) 1:329–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.08.002

74. Örmeci N. Surveillance of the Patients with High Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer. J Gastrointest Canc (2017) 48:246–9. doi: 10.1007/s12029-017-9972-3

75. Turati F, Talamini R, Pelucchi C, Polesel J, Franceschi S, Crispo A, et al. Metabolic syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma risk. Br J Cancer (2013) 108:222–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.492

76. Kew MC. Hepatic iron overload and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer (2014) 3:31–40. doi: 10.1159/000343856

77. Dongiovanni P, Fracanzani AL, Fargion S, Valenti L. Iron in fatty liver and in the metabolic syndrome: a promising therapeutic target. J Hepatol (2011) 55:920–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.008

78. Rotman Y, Koh C, Zmuda JM, Kleiner DE, Liang TJ, NASH CRN. The association of genetic variability in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology (2010) 52:894–903. doi: 10.1002/hep.23759

79. Liu YL, Reeves HL, Burt AD, Tiniakos D, McPherson S, Leathart JB, et al. TM6SF2 rs58542926 influences hepatic fibrosis progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun (2014) 5:4309. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5309

80. Martínez-Chantar ML, Vázquez-Chantada M, Ariz U, Martínez N, Varela M, Luka Z, et al. Loss of the glycine N-methyltransferase gene leads to steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology (2008) 47:1191–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.22159

81. Murphy SK, Yang H, Moylan CA, Pang H, Dellinger A, Abdelmalek MF, et al. Relationship between methylome and transcriptome in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology (2013) 145:1076–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.047

82. Chu H, Williams B, Schnabl B. Gut microbiota, fatty liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Res (2018) 2:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.livres.2017.11.005

83. Kutlu O, Kaleli HN, Ozer E. Molecular Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis- (NASH-) Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2018) 2018:8543763. doi: 10.1155/2018/8543763

84. Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG, et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell (2010) 140:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.052

85. Kudo Y, Tanaka Y, Tateishi K, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto S, Mohri D, et al. Altered composition of fatty acids exacerbates hepatotumorigenesis during activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Hepatol (2011) 55:1400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.025

86. Yang S, Liu G. Targeting the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett (2017) 13:1041–7. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5557

87. Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest (2004) 114:147–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI22422

88. Lebeaupin C, Vallée D, Hazari Y, Hetz C, Chevet E, Bailly-Maitre B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol (2018) 69:927–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.06.008

89. Xu Z, Chen L, Leung L, Yen TS, Lee C, Chan JY. Liver-specific inactivation of the Nrf1 gene in adult mouse leads to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatic neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102:4120–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500660102

90. Ma C, Kesarwala AH, Eggert T, Medina-Echeverz J, Kleiner DE, Jin P, et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4(+) T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature (2016) 531:253–7. doi: 10.1038/nature16969

91. Wolf MJ, Adili A, Piotrowitz K, Abdullah Z, Boege Y, Stemmer K, et al. Metabolic activation of intrahepatic CD8+ T cells and NKT cells causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cancer via cross-talk with hepatocytes. Cancer Cell (2014) 26:549–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.003

92. Crawford JM. Histologic findings in alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis (2012) 16:699–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.004

93. Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, et al. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol (2017) 3:1683–91. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055

94. Gramenzi A, Caputo F, Biselli M, Kuria F, Loggi E, Andreone P, et al. Alcoholic liver disease–pathophysiological aspects and risk factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2006) 24:1151–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03110.x

95. Becker U, Deis A, Sørensen TI, Grønbaek M, Borch-Johnsen K, Müller CF, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology (1996) 5:1025–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230513

96. Seitz HK, Pöschl G. The role of gastrointestinal factors in alcohol metabolism. Alcohol Alcohol (1997) 32:543–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008294

97. Ikejima K, Enomoto N, Iimuro Y, Ikejima A, Fang D, Xu J, et al. Estrogen increases sensitivity of hepatic Kupffer cells to endotoxin. Am J Physiol (1998) 274:G669–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.4.G669

98. Stewart SH. Racial and ethnic differences in alcohol-associated aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase elevation. Arch Intern Med (2002) 162:2236–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2236

99. Stickel F, Osterreicher CH. The role of genetic polymorphisms in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol (2006) 41:209–24. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl011

100. Global status report on alcohol and health. (2018). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol.

101. Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol (2013) 59:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.007

102. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol (2019) 70:151–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014

103. Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int (2015) 35:2155–66. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818

104. Haflidadottir S, Jonasson JG, Norland H, Einarsdottir SO, Kleiner DE, Lund SH, et al. Long-term follow-up and liver-related death rate in patients with non-alcoholic and alcoholic related fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol (2014) 14:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-166

105. Ganne-Carrié N, Nahon P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol (2019) 70:284–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.008

106. Hassan MM, Hwang LY, Hatten CJ, Swaim M, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology (2002) 36:1206–13. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36780

107. Albano E. Free radical mechanisms in immune reactions associated with alcoholic liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med (2002) 32:110–4. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00773-0

108. Sangineto M, Villani R, Cavallone F, Romano A, Loizzi D, Serviddio G. Lipid Metabolism in Development and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:1419. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061419

109. Crabb DW, Galli A, Fischer M, You M. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Alcohol (2004) 34:35–8. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.005

110. Stickel F, Hampe J. Genetic determinants of alcoholic liver disease. Gut (2012) 61:150–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301239

111. Xu T, Li L, Hu HQ, Meng XM, Huang C, Zhang L, et al. MicroRNAs in alcoholic liver disease: Recent advances and future applications. J Cell Physiol (2018) 234:382–94. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26938

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, etiology, metabolic syndrome, hepatitis viruses

Citation: Suresh D, Srinivas AN and Kumar DP (2020) Etiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Special Focus on Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Oncol. 10:601710. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.601710

Received: 01 September 2020; Accepted: 30 October 2020;

Published: 30 November 2020.

Edited by:

Rohini Mehta, BioReliance, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Suresh, Srinivas and Kumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Divya P. Kumar, ZGl2eWFwa3VtYXJAanNzdW5pLmVkdS5pbg==

Diwakar Suresh

Diwakar Suresh Akshatha N. Srinivas

Akshatha N. Srinivas Divya P. Kumar

Divya P. Kumar