94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Oncol. , 01 February 2021

Sec. Cancer Genetics

Volume 10 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.586789

This article is part of the Research Topic Genetics and Epigenetics of RNA Methylation System in Human Cancers View all 20 articles

Cellular ribonucleic acids (RNAs), including messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), harbor more than 150 forms of chemical modifications, among which methylation modifications are dynamically regulated and play significant roles in RNA metabolism. Recently, dysregulation of RNA methylation modifications is found to be linked to various physiological bioprocesses and many human diseases. Gastric cancer (GC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) are two main gastrointestinal-related cancers (GIC) and the most leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. In-depth understanding of molecular mechanisms on GIC can provide important insights in developing novel treatment strategies for GICs. In this review, we focus on the multitude of epigenetic changes of RNA methlyadenosine modifications in gene expression, and their roles in GIC tumorigenesis, progression, and drug resistance, and aim to provide the potential therapeutic regimens for GICs.

With the deepening of genetics research and the emergence of epigenetics, many reversible chemical modifications have been identified. In RNAs, human cells undergo various forms of modification with different levels (1–3). The constitutive non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are known to contain larger number of pseudouridine (Ψ) and 2’-O-methylations (2’-OMe or Nm) modifications (1). In addition, various modifications are identified in the regulatory ncRNAs including small ncRNAs (sncRNAs), long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs) and play important roles in metabolism and functions (4–7). However, owing to the spatiotemporal specificity of regulatory ncRNAs in various tissues, the detailed and conserved biological characteristics of most RNA modifications are unclear. As for mRNAs, internal methylation modifications have been recently revealed with help of the advanced detection and analysis technologies as well as the common modification of N7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap in the 5’ terminal region of mRNA (8–12). The most prevalent and crucial internal methylation form in mRNAs is N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification that firstly identified in 1974 in eukaryotic cells (12–16), while the other major forms include N6,2’-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), 2’-OMe, and 5-methylcytosine (m5C).

Gastric cancer (GC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) are the most common gastrointestinal-related cancers (GICs). CRC is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer (6.1%) and the second leading cause of cancer death (9.2%) worldwide, while GC is the sixth diagnosed caner and the third cause of cancer death (8.2%) (17). In-depth research on molecular mechanisms in GICs can provide important insights in developing novel treatment strategies for GICs.

Recently, RNA methylation has been found to play critical roles in various bioprocesses including embryonic development, RNAs metabolism, gene expression regulation, and its aberrant regulation has been linked to many human diseases including cancer (18). Herein, we mainly focus on the multitude of epigenetic changes of RNA methlyadenosine modifications in gene expression, and their roles in GIC tumorigenesis, progression, and drug resistance, and aim to provide the potential therapeutic regimens for GICs.

Although m6A is an “old” modification form that was firstly discovered in 1974 (13, 14), it had not gained enough attention until two breakthrough methods developed in 2011. The first breakthrough is the discovery of FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein), the first mammalian m6A demethylase in 2011 (19) and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), another demethylase in mouse fertility and spermatogenesis in 2013 (20), which proves and highlights that the m6A modification is a dynamic process and regulated by both methyltransferase and demethylase. The second breakthrough is that the transcriptome-wide distribution of m6A modification has been well revealed at ~100–200-nucleotide resolution in 2012 owing to the development of methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq or m6A-seq) technology (21, 22). Since then, other detection methods such as single-nucleotide resolution, antibody-independent, or isoform characterization analysis, have emerged as powerful tools for the m6A analysis. These tools mainly include site-specific cleavage and radioactive labeling followed by ligation-assisted extraction and thin layer chromatography (SCARLET) (23), m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) (4), m6A level and isoform characterization sequencing (m6A-LAIC-seq) (24), deamination adjacent to RNA modification targets sequencing (DART-seq) (25), MAZTER-seq (26), m6A-sensitive RNA-endoribonuclease-facilitated sequencing (m6A-REF-seq) (27), m6A-lable-seq (28), m6A-SEAL (29), and the third-generation sequencing technologies (30). However, these methods have shortcomings such as inconvenient procedures (radioisotope p32), high cost, unavailability to distinguish m6A and m6Am, and detection limits of a certain motif.

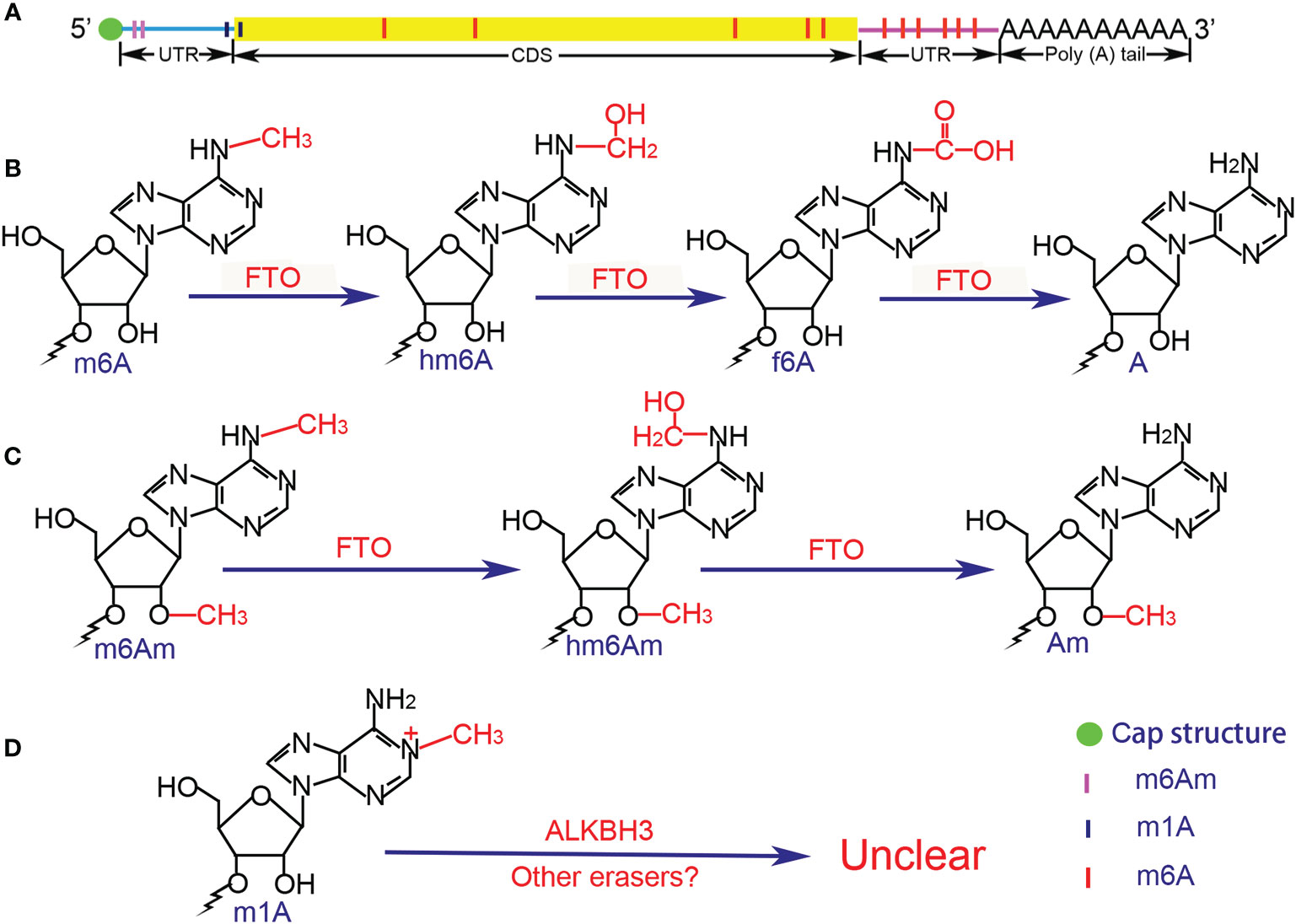

As reported, m6A modification occurs in almost all transcripts with the ratio of m6A/A in mRNAs ranges from 0.2 to 0.5% (15, 24, 31, 32). The distribution of m6A modifications are not random but strictly restricted, where they are commonly confined in the consensus sequence RRACH that refers to [G/A/U][G>A]m6AC[U>A>C] motif (7, 21, 33) and enriched in the long internal exons and regions next to the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) within mRNAs (21, 22, 27). The deposition of m6A is in the introns of the precursor mRNAs (pre-mRNAs) and in primary microRNAs (pri-miRNAs), which means that the m6A modification can be regulated either before or simultaneously with RNAs splicing and processing (34) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribution and chemical structure of methylation modifications. (A) m6Am and m1A are mainly enriched in the 5’UTR, whereas m6A is concentrated in the 3’UTR. (B) Demethylation of m6A is in a stepwise manner, the intermediate of hm6A is the direct oxidation product of m6A, while f6A is the further oxidized product of hm6A, and the final product is A. (C) The demethylation process of m6Am is similar to that of m6A, but the potential intermediate f6Am has not been reported. (D) The demethylation process of m1A remains unclear due to the special chemical bond. UTR, untranslated region; CDS, coding sequence; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; ALKBH3, AlkB homolog 3; A, adenosine; Am, 2’-O-methyladenosine; m6A, N6-methyladenosine; hm6A, N6-hydroxymethyladenosine; f6A, N6-formyladenosine; m6Am, 2’-O-dimethyladenosine; hm6Am, N6-hydroxymethyl, 2’-O-methyladenosine; m1A, N1-methyladenosine.

In 1994, Bokar and colleagues characterized a multicomponent complex of mRNA m6A methyltransferases (MTases, “writers”) that extracted from the nucleus, which is composed of three components with ~30 KDa, ~200 KDa, and ~875 kDa, respectively. The ~200 kDa component contains the S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-binding site on a 70 kDa subunit and the ~875kDa component may has affinity for mRNA strands (35, 36). Subsequently the SAM-binding ability of the 70 kDa subunit and was named as MT-A70 (now known as methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) (37). Hereafter, methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) has been identified as the homologue of METTL3 and functions as another core component of the complex (38–41). Both METTL3 and METTL14 are highly conserved within the (D/E)PP(W/L) active site and the SAM−binding motif in mammals with ~35 and ~43% sequence homology of the MTase domain in mouse and human respectively (39, 40, 42). Despite METTL3 and METTL14 exhibit relatively weak MTase activity when acting alone, the METTL3-METTL14 complex with a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 shows a much higher catalytic activity. The primary functions of METTL3 in the complex is to catalyze methyl-group transfer, whereas METTL14 is the aide that helps MTase complex positioning by identifying the histone H3 trimethylation at Lys36 (H3K36me3) (in co-transcriptional manner), and offers a structural scaffold that enhancing the catalytic activity of METTL3, even though METTL14 can affect the m6A levels more significantly than METTL3 (40, 41, 43–46).

In addition, the Wilms tumor 1-associated protein (WTAP) that previously found to interact with the Wilms’ tumor suppressor-1 (WT1) and participates alternative pre-mRNA splicing was identified as an additional component of the m6A MTases complex (39, 47–49). Without the MTase domain, WTAP assists METTL3/14 to localize in the nuclear speckles where enriched with pre-mRNA processing factors and synergize to methylate the adenosines in mRNAs (39, 41).

Recent studies have identified other associated proteins in MTase complex. Schwartz et al. (50) found that KIAA1429 (VIRMA) is required for the m6A methylation in human cells, and Yue et al. further demonstrated that KIAA1429 can play a role as region-selective factors by recruiting the catalytic core components METTL3/METTL14/WTAP to 3’UTR and near the stop codon (51). They also highlighted the importance of Cbl proto oncogene like 1 (HAKAI or CBLL1) and zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13) in the full methylation program, and ZC3H13 is required for the nuclear localization of MTase complex (51, 52). The RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15) and its paralogue RBM15B are also identified as the regulators of m6A modification in the lncRNA X-inactive specific transcript (XIST), as well as in mRNAs (53). In addition, the transcription factors zinc finger protein 217 (ZFP217), SMAD2/3, and CAAT-box binding protein (CEBPZ) are found to mediate the m6A deposition in mRNAs (54–56). Some other m6A methyltransferases such as METTL5, METTL16, and zinc finger CCHC-type-containing 4 (ZCCHC4) are also indispensable for m6A formation, especially in ncRNAs and rRNAs (57–59).

FTO was recognized as the first m6A eraser (19), which was originally discovered in 1999 and was officially named in 2007 (60, 61). Bioinformatics analysis revealed that FTO is one of the non-heme FeII/α-ketoglutarate(α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases (also known as non-heme FeII/2-oxoglutarate (2-OG)-dependent dioxygenases) (62). FTO was shown to mediate the demethylation of N3-methylthymidine in single-stranded DNA and N3-methyluridine in single-stranded RNA in vitro (63, 64). In 2011, Jia et al. (19) proved that FTO could participate in the demethylation process of nuclear RNAs in nuclear speckles, and Fu et al. (65) further revealed the role of FTO in the detailed process of RNA m6A demethylation in 2013. They found that FTO oxidizes m6A in a stepwise manner, and the intermediate of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine (hm6A) is the direct oxidation product of m6A and turns into the form of N6-formyladenosine (f6A). The final products of m6A demethylation are unmethylated adenosine and formaldehyde (from hm6A) or formic acid (from f6A). Interestingly, the half-lives of hm6A and f6A are suggested to be ~3 h under physiological conditions, meaning that the decomposing of hm6A and f6A do not occur simultaneously with the oxidation of m6A.

As for ALKBH5, the second m6A demethylase identified so far in mammals, belongs to the AlkB family, a class of the non-heme FeII/α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases superfamily which was originally shown to revert DNA base damage by catalyzed oxidative demethylation of N-alkylated nucleic acid bases (20, 66–68). Structure analysis indicates that ALKBH5 has comparable catalytic activity with FTO, whereas AlkB has low level (~17%) of the amino acid sequence identity to FTO (62, 69). While FTO can demethylate on both single-stranded RNA/DNA and double-stranded RNA/DNA (albeit low) (19, 70), ALKBH5 only demethylate the single-stranded RNA/DNA with the sequence preference (the activity in the consensus sequence is twice that in other sequences), which may be due to the fact that ALKBH5 mainly localizes in nuclear speckles and acts in regulating the nuclear export and metabolism of RNAs (20).

There are four main readers selectively bind the m6A-containing mRNAs in the nucleus. In 1998 Imai et al. (71) isolated a novel RNA splicing-related protein YT521 by using yeast two-hybrid screens system with rat transformer-2-beta1 (RA301) as bait, and Hartmann et al. identified a homologous protein YT521-B by using htra2-beta1 as bait (72). Subsequently, the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain was defined as a new protein family, the YTH (YT521-B homology) domain containing protein family, and now YT521-B is known as the YTH domain-containing protein 1 (YTHDC1) (73). YTHDC1 localizes in a subnuclear structure named YT bodies that contain transcriptionally active sites and are close to other subnuclear compartments such as speckles and coiled bodies (74). Structure analysis demonstrated that the GG(m6A)C sequence is the preferred binding site for YTH domain in YTHDC1 (75, 76). Since its localization is adjacent to the nuclear speckles, YTHDC1 is found to participate in pre-mRNAs splicing containing m6A sites, and mediate its nuclear export. YTHDC1 facilitates the splicing pattern of exon inclusion in targeted mRNAs by recruiting pre-mRNA splicing factor SRSF3 (SRp20) and inhibiting SRSF10 (SRp38), by which it changes alternative splicing patterns via modulating splice sites selection in a concentration-dependent manner (72, 77). In addition, YTHDC1 is found to interact with the nuclear RNA export factor 1 (NXF1) to promote the nuclear export of the m6A-containing mRNAs (78).

The other three readers in the nucleus belong to the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) family that is composed of more than 20 members. HnRNP protein contains at least one RNA-binding domain with RNA recognition motif (RRM), K-Homology (KH) domain, or an arginine/glycine-rich box (79). Recently, their role as the “reader” of m6A remains controversial. Previously, Alarcon et al. showed that hnRNPA2/B1 can directly bind with m6A by matching the m6A consensus motif and regulate the alternative splicing of its mRNA targets (80), whereas Wu et al. (81) suggested that hnRNPA2/B1 may interact with m6A via the “m6A switch” mechanism instead of directly recognizing the m6A-containing bases, by which the m6A controls the RNA-structure-dependent accessibility of the RNA-binding domains to affect the RNA-protein interactions for biological regulation. In addition, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (hnRNPC), an abundant nuclear RNA-binding protein, and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G (hnRNPG), a low-complexity protein, interact with the m6A-containing mRNAs via the similar “m6A switch” mechanism (6, 82, 83).

Besides readers in the nucleus, four members of the YTH domain-containing proteins are identified in the cytoplasm that are involved in mRNAs metabolism via interacting the m6A with their hydrophobic pocket, an aromatic cage formed by tryptophan residues, within the YTH domain (76, 84, 85). YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 are highly homologous, and all contain a ~40 kDa low-complexity domain and a prion-like domain (86). The most abundant YTHDF paralog, YTHDF2, is the first member to be fully studied, where it was originally implicated in regulating the instability and the decay of the m6A-containing mRNAs by localizing the complex of YTHDF2-m6A-mRNA from the translatable pool to the processing bodies (P-bodies) (87). However, another group demonstrated that the P-bodies only act an indirect role in the decay of m6A-containing RNAs since no direct interaction between YTHDF2 and GW182, the core component of the P-bodies was found (88). Subsequent study revealed that YTHDF2-m6A-mRNA complex was located in the stress granules or neuronal RNA granules through the phase separation mechanism upon stress stimulation and was subject to compartment-specific regulations (89).

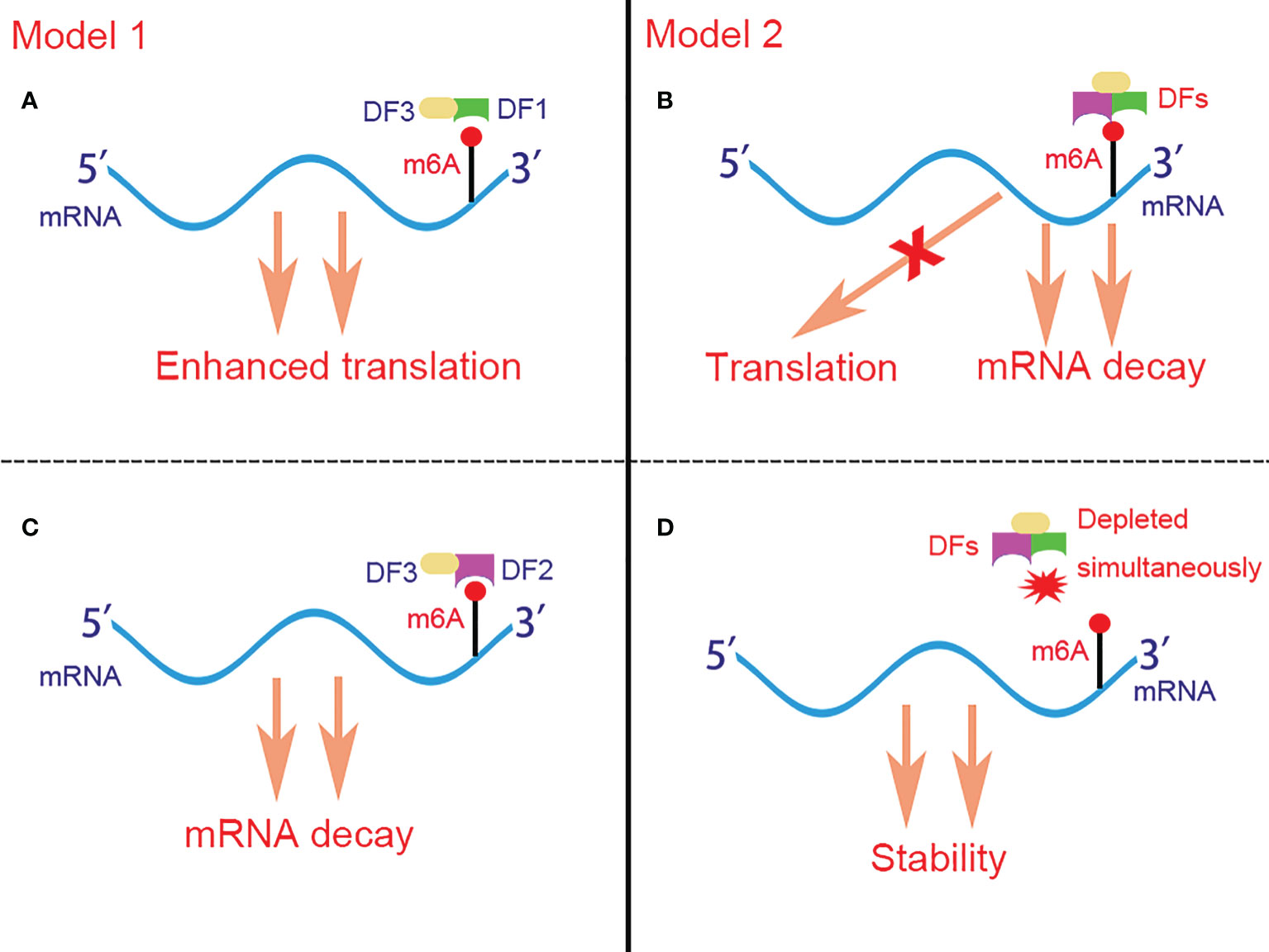

Although all YTHDF proteins can recruit CCR4-NOT and promote mRNA deadenylation (88), YTHDF1 is the only member which is reported to facilitate translation by binding at the RRACH motifs instead of the flanking sequence that cluster around the stop codon and subsequently recruiting translation initiation factor (eIF) and ribosome. The association of YTHDF1 with translational initiation machinery may be depend on the loop structure mediated by eIF4G and the interaction of YTHDF1 with eIF3 (90). Besides, YTHDF1 is found to bind to the nascent methylated mRNAs earlier than YTHDF2, which suggests that the translation of mRNAs occurs before their decay under various physiological conditions (90). As for YTHDF3, it plays dual functions in m6A-containing mRNAs metabolism by either promoting the translation of the targeted mRNAs via interaction with YTHDF1 (91), or accelerating the decay of the targeted mRNAs via interaction with YTHDF2 (92). Controversially, Jaffrey et al. (93) proposed another brand new but opposite model for the role of YTHDF proteins in regulating m6A-containing mRNAs. They demonstrated that YTHDF proteins binded with the same mRNA rather than different mRNAs and act redundantly to co-mediate mRNA degradation, and the stability of mRNA fails to restore until all YTHDF1,2,3 are depleted simultaneously (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Two controversial models for the function of DFs in regulating m6A-containing mRNAs. In model 1 (A, C), DF1 and DF2 bind to different mRNAs and promote their translation and degradation respectively. In model 2 (B, D), DFs bind to the same mRNA rather than different mRNAs simultaneously and act redundantly to co-mediate mRNA degradation but not translation. The stability of mRNA can be restored only when DF1-3 are depleted simultaneously. DFs, YTHDF proteins; DF1, YTHDF1; DF2, YTHDF2; DF3, YTHDF3; m6A, N6-methyladenosine.

The fifth member of the YTH protein family is YTHDC2, which is different from the other cytoplasmic “readers”. YTHDC2 has a large molecular mass of ~160 kDa and contains the helicase domain (94). YTHDC2 is previously reported to enhance the translation efficiency of its targets and decrease their mRNA abundance by binding to the m6A site at its consensus motif and influencing the mRNA secondary structures (94, 95). However, a latest report indicated that YTHDC2 could also reduce the m6A-containing mRNAs stability and inhibit gene expression in certain situations (96).

The insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs, originally called IMPs) family, including IGF2BP1/2/3, which is initially recognized as an IGF2 translation inhibitor (97), belongs to a new family of m6A readers that mainly prevent the m6A-containing mRNAs from degradation in cytoplasm (98). IGF2BPs are composed of two RRM domains and four KH domains, and preferentially bind the m6A-modified mRNAs through recognizing the consensus GG(m6A)C sequence and facilitate the stability and translation of thousands of its mRNA targets by co-localizing in the P-bodies or stress granules, thus upregulating the gene expression in globally (98). Recently, ELAV like RNA binding protein 1 (ELAVL1, also known as HuR), matrin 3 (MATR3), and poly (A) binding protein cytoplasmic 1 (PABPC1) have been identified as the cofactors of IGF2BPs that promote the stability of m6A-containing mRNAs simultaneously.

In addition, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) and proline rich coiled-coil 2 A (PRRC2A) are reported to play a role as the reader/stabilizer of the m6A-containing mRNAs (99, 100). METTL3 is found to associate with ribosomes and promote translation in some cancers when it localizes in the cytoplasm (101, 102). Moreover, accumulated readers of the m6A in ncRNAs is summarized in Table 2.

The m6Am is the second most prevalent modification in cellular mRNAs and in some small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs). The structure of mRNAs after the m7G cap can be divided into three main types, the m7G5’ppp5’NmpNp (p denotes phosphate group, Nm and N denote 2’-O-methylated nucleotide and nucleotide respectively), the m7G5’ppp5’NpNp and the m7G5’ppp5’NmpNmpNp (15, 103, 104). Recently, the 2’-O-methyladenosine (Am) was showed to be the first nucleotide adjacent to the m7G cap and it can be further modified at the N6 position by methylation to generate m6Am (92% chance of being modified), where the structure of m7G5’ppp5’m6AmpNp comprises 20–30% of all the structures (105, 106) (Figure 1). The second nucleotide can harbor a similar modification but with a lower frequency, whereas m6Am rarely located in the third nucleotide and m6A or A has not been found at the first nucleotide position (107). In addition, there are ~6% of the m6Am occurs outside the 5’UTR, and motif analysis reveals that the m6Am mainly deposit in a novel motif BCm6Am (B represents C, G, or U) that enriched in the transcription start site (TSS), rather than the canonical m6A motif RRACH (4, 108, 109). Molinie et al. used liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to quantify of the m6Am in mRNAs and found that mRNAs contain ~3 m6Am nucleotides per 105 nucleotides, revealing a 33-fold level of the m6A modification than the m6Am in mRNAs (24). Consistently, Liu et al. (108) confirmed the m6Am/A ratio of total RNAs and mRNAs ranges from 0.0036 to 0.0169% and from ~0.01 to 0.02% respectively. Currently, the m6Am transcriptome-wide expression can only be detected by the methods of the crosslinking-induced truncation sites-based miCLIP (CITS miCLIP) and the refined RIP-seq, and an antibody-free enzyme-assisted chemical approach termed m6A-SEAL (29) (Table 1).

The formation of m6Am occurs on the basis of Am that formed by the MTases HENMT1 and FTSJ3 (110, 111), and its modification system rarely known yet. The m6Am MTase was previously purified with a molecular weight of ~65 KD in 1978, and phosphorylated CTD-interacting factor 1 (PCIF1) was recognized as the first m6Am MTase in 2019. It was named by its ability to directly bind to the phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) by its WW domain, also called cap-specific adenosine methyltransferase (CAPAM) (106, 112, 113). Unlike the m6A core readers that work in the form of a methyltransferase complex, PCIF1 is a “stand-alone” RNA MTase and functions in an m7G cap-dependent manner. Recently, METTL4 was reported to catalyze m6Am methylation in the U2 snRNA (114).

FTO, the first m6A demethylase, was found to mediate the demethylation of m6Am in the similar manner to that of m6A (115, 116). The intermediate of N6-hydroxymethyl, 2’-O-methyladenosine (hm6Am) was detected as well as the end product Am. Intriguingly, although both m6A and m6Am can be catalyzed by FTO, the priority between them is still controversial. Zhang et al. (116) showed that FTO displays the similar demethylation activity toward internal m6A and cap m6Am modifications in vivo and in vitro. But He et al. revealed that FTO shows different affinity to the m6A and the m6Am among cells where the m6A is most affected despite it prefers the m6Am in vitro by the cellular cap-binding proteins (117). Controversially, Mauer et al. (115) found that FTO does not efficiently demethylate m6A but preferentially demethylates m6Am. They further showed that ALKBH5 did not affect the m6Am in mRNAs and stated that FTO may targets the m6Am whereas ALKBH5 targets the m6A in vivo.

Currently, there is no m6Am reader that has been identified, and its function remains controversial. The first work showed that the m6Am stabilizes mRNA by preventing the mRNA-decapping enzyme DCP2-mediated decapping and microRNA-mediated mRNA degradation (115), and it was confirmed by Mauer’s work (109). However, Sendinc et al. (118) revealed that m6Am fails to alter mRNA transcription and stability, and negatively impacts cap-dependent translation. Akichika et al. (106) further showed that the m6Am facilitates the translation of capped mRNAs. The direct readers of the m6Am are under investigated (Table 2).

The m1A modification was firstly discovered in the total mixed RNA samples in 1961 (119) and was found that it can rearrange into the m6A under alkaline conditions (Dimroth rearrangement) in 1968 (120). Subsequently, accumulating evidence has shown that the m1A occurs in rRNAs and tRNAs where the m1A is typically found at position 9 and 58 in the tRNA TΨC-loop and plays key roles in the structure formation and function execution via its methyl adduct and positive charge (121, 122). By using of the liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), the ratio of m1A/A in the mammalian cell lines and tissues can be easily detected, which ranging from approximately 0.015 to 0.054% and up to 0.16% (123, 124). Hereafter, He et al. (123) used the combined method of an antibody-based approach called m1A-seq and an orthogonal chemical method based on Dimroth rearrangement to obtain a more detailed distribution of m1A. They found that the distribution pattern and the peaks of the m1A are highly conserved in the samples from multiple sources, and the m1A enrich in the 5′ UTR, near the start codons or TSS, which is similar to that of m6Am. Yi et al. further supported the finding by original technology m1A-ID-seq (124). In addition, single-nucleotide resolution analysis (m1A-MAP) showed that the m1A lacks of obvious preference to certain motif, but the GCA codon and GUUCRA tRNA-like motif are frequently modified, and no m1A is detected in the AUG start codon (123, 125). Finally, Safra et al. reported 15 m1A sites in mRNAs and lncRNAs (126) (Table 1) (Figure 1).

Although a variety of the m1A MTases, including tRNA methyltransferase 10C (TRMT10C), TRMT6/61A, TRMT61B, base MTase of 25S RNA (BMT2), MTR1, and nucleomethylin (NML), have been discovered, most of them catalyze the sites on tRNAs or rRNAs (122, 127–130). Li et al. unveiled that TRMT6/61A is able to methylate the m1A sites that are confined in GUUCRA tRNA-like motifs in mRNAs, and some of the mitochondrial (mt)-mRNAs are the target of TRMT61B (125). In addition, Safra et al. (126) have identified that a single m1A site in the mt-ND5 mRNA which is catalyzed by TRMT10C. Nonetheless, there is no direct specific m1A writer has been identified for mRNA yet.

The m1A demethylases are found to only catalyze tRNAs so far. He et al. (131) showed that the human homolog of E. coli AlkB ALKBH1 is an important eraser that catalyzes the demethylation of the m1A in tRNAs in 2016, and FTO, was proven to mediate the m1A demethylation in tRNAs (117). However, neither ALKBH1 nor FTO mediates the removal of the methyl group from m1A in mRNAs. Recently, another demethylase ALKBH3 was shown to have a strong preference for single stranded DNA/RNA and the ability of repairing methylation damage to RNA in vitro in both tRNAs and mRNAs (123, 124, 132, 133). Yi et al. (124) further showed that ALKBH3 has minimal sequence preference and acts globally in the transcriptome.

The process of eukaryotic protein translation, especially the initiation step of translation, is strictly regulated in cells. Structure analysis showed that the secondary structure in the 5’UTR which is the target of the initiation factors such as eIF4A/B/H complex can affect the efficiency of the initiation of translation and the early elongation by impeding the binding and movement of the 40S ribosome (134, 135). He et al. (123) suggested that the m1A plays a positive role for the translation initiation in mammalian mRNAs, which is further supported by Li et al. (125). Mechanically, the m1A may inhibit Watson-Crick base pairing or introduce charge-charge interactions, leading to the alteration of the secondary/tertiary structure of 5’UTR in mRNAs. Potential readers specifically bound to the m1A in mRNAs are supposed to promote the initiation of translation, which is analogous to the role of YTHDF1 in translation enhancement. However, there are controversial reports showed that the m1A can repress the translation of mRNAs, especially mt-mRNAs while the underlying mechanism remains to be explored (126). In addition, the m1A is found to promote mRNA degradation by interacting with its potential readers YTHDF2/3 (136, 137) (Table 2).

Under normal physiological condition, methylation modification is precisely modulated by the methyltransferases and demethylases, and involved in regulating alternative splicing, nuclear export, stability, translation, or degradation of the methylated RNAs, thereby affecting cell self-renew, cell proliferation, and cell differentiation. Recently, accumulating studies have revealed that abnormality in RNA methylation leaded by mutations or dysregulation that cause the gain or the loss of methylation sites are closely related to the initiation, progression metastasis, and suppression of various tumors including GICs (138).

The writer, METTL3, is found to be upregulated in GC patients with poor prognosis, which is caused by the P300-mediated H3K27 acetylation activation in the promoter of METTL3 and mediation by the transcription factor GFI1 (139–143). Yue et al. (139) have identified the zinc finger MYM-type containing 1 (ZMYM1) mRNA as the direct target of METTL3. Mechanistically, the reader ELAVL1 binds to the m6A sites within ZMYM1 mRNA and enhances the stability of ZMYM1. The induced ZMYM1 further inhibits the expression of E-cadherin by forming a complex of CtBP/LSD1/CoREST/ZMYM1 in the promoter region of E-cadherin, thus stimulating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and promoting metastasis of GC. In another report, the m6A modification of hepatoma derived growth factor (HDGF) mRNA can be induced by high level of METTL3, and recognized by the reader IGF2BP3 to promote its stability. The upregulated HDGF could further facilitate tumor angiogenesis and increase glycolysis in GC, which in turn enhance the tumor growth and liver metastasis (140). Additionally, the mRNAs of pre-protein translocation factor (SEC62), ARHGAP5, and MCM5 and MCM6 (the component molecules in the MYC pathway) are highly modified by the aberrant METTL3, and led to the acceleration of GC progression (141, 143, 144).

Upregulated METTL3 in CRC primary or metastatic tissues is highly associated with unfavorable outcomes (145–150). One potential mechanism mediated by upregulated METTL3 is ceramide glycosylation that generates glycosphingolipids (particularly globotriaosylceramide) and activates cSrc and β-catenin signaling (151). Li et al. (145) unveiled that higher METTL3 expression in CRC facilitates the methylation of SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2 (SOX2) mRNA, and the reader IGF2BP2 further recognized the m6A-containing SOX2 mRNA and induced the expression level of SOX2 protein. SOX2 was previously reported to control the properties of the stem cells and enhance cell proliferation and invasion in squamous cell carcinoma (152). While in CRC, highly expressed SOX2 regulated its downstream targets, including cyclin D1 (CCND1), MYC (mainly referred to as c-Myc), and POU class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1), and promoted their expression levels, thus upregulating CD133, CD44, and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM). Shen et al. (148) found that METTL3 can directly interacts with the 5’/3’UTR regions of Hexokinase 2 (HK2) mRNA and the 3’UTR region of Glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1, also SLC2A1) mRNA, and subsequently stabilized their mRNAs and activated the glycolysis pathway in CRC cells in a IGF2BP2- or IGF2BP2/3-dependent manner. In addition, upregulated METTL3 could facilitate CRC cell proliferation, progression, and metastasis by various signaling pathways including miR-1246/SPRED2/MAPK signaling pathway, p38/ERK pathway, and cyclin E1 (CCNE1) cell proliferation pathway (147, 149, 150).

Analogously, the high level of other writers WTAP and RBM15 also predicts poor prognosis for GC (153–155) Li et al. found that WTAP could be served as an independent predictor of GC and its high expression is closely related to the low T lymphocyte infiltration and T cell-related immune response (154).

Intriguingly, the writer METTL14 is reported to be downregulated in GC and CRC patients (139, 156). Zhang et al. (156) unveiled that METTL14 suppression may cause activation of the Wnt and PI3K-Akt signaling and thus promote GC progression. While Yang et al. (157) have revealed that the downregulated METTL14 is associated with the poor outcomes of CRC patients through up-regulating oncogenic lncRNA XIST. Specifically, the m6A level within lncRNA XIST is reduced as METTL14 suppression, which could lead to the RNA degradation and decay mediated by the m6A reader YTHDF2. The abundant lncRNA XIST due to downregulation of METTL14 acts as a carcinogen and promote cell proliferation and metastasis in CRC (158). Additionally, the downregulated METTL14 affects the m6A level in pri-miR-375, by which it decreased the binding of DGCR8 to pri-miR-375 and results in the reduction of mature miR-375. The reduction of miR-375 causes induced level of Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) and SP1, and ultimately leads to cell growth in CRC via miR-375/YAP1 pathway and cell invasion via miR-375/SP1 pathway (159).

FTO, the first mammalian m6A demethylase and the only m6Am demethylase currently discovered, is found to mediate the progression in GICs. FTO was reported to serve as an independent prognostic marker due to its frequently higher expression in high-risk scores subtype of GC (153, 155, 160). Other erasers ALKBH3 and ALKBH5 are also upregulated in GC, and ALKBH5 is found to promote the invasion and metastasis of GC by interacting with the lncRNA NEAT1 (nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1) (155, 161, 162).

However, the expression levels of ALKBH5 and FTO in CRC are still controversial (146). From The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, and the Human Protein Atlas, ALKBH5 shows weak expression in CRC tissues compared to the normal tissues, and FTO shows no significant difference between CRC tissues and normal tissues. Whereas Wu et al. revealed a potential CRC-promoting mechanism via the ALKBH5/m6A/RP11/hnRNPA2B1/E-ligases/Zeb1 axis (163). They found that lncRNA RP11 in CRC is highly expressed and associated with the CRC stage in patients, by which lncRNA RP11 is regulated in an m6A-dependent manner and negatively correlated with ALKBH5 although METTL3 is elevated in CRC patients. Mechanistically, m6A-containing RP11 can interact with the reader hnRNPA2B1 and bind to its downstream targets, two E3-ligase mRNAs Siah1 and Fbxo45 to accelerate their decay. The reduced Siah1 and Fbxo45 further downregulates the EMT-transcription factors Zeb1, and ultimately leads to the development of CRC. In addition, Relier et al. (164) showed that low expression of FTO in CRC cells causes increase of the m6Am levels in mRNAs and results in the enhanced malignancy and chemo resistance in CRC cells, which can be partially reversed by inhibition of PCIF1.

Emerging studies have reported the upstream regulatory mechanisms that lead to generation of the aberrant readers in CRC. Wang et al. (165) have identified a novel lncRNA LINRIS to stabilize IGF2BP2 via LINRIS/IGF2BP2/MYC axis and promote cell proliferation in CRC. Mechanistically, the elevated level of LINRIS in the CRC patients with unfavorable prognostic could act on IGF2BP2 and protect it from K139 ubiquitination and autophagy degradation, and maintain its stability. The upregulated IGF2BP2 subsequently promotes the expression of its downstream target MYC mRNA, and enhances the MYC-mediated glycolysis in CRC, which eventually leads to progression of CRC. Inhibition of this axis by GATA3 may provide a potential therapeutic strategy for CRC.

Recently, Ni et al. showed another lncRNA involved in the YAP signaling pathway during CRC progression via the GAS5/YAP/YTHDF3 axis (166). They found GAS5 is downregulated in most of CRC tissues and is negatively correlated with the protein levels of YAP and YTHDF3, while the increased YTHDF3 is a significant prognostic factor for poor overall survival in CRC patients (146). Mechanistically, downregulation of GAS5 inhibits phosphorylation of YAP and attenuates its ubiquitination and degradation. The increased YAP further promotes expression level of YTHDF3, however, the downstream regulatory pathway of YTHDF3 that facilitates CRC progression is unclear.

Additionally, YTHDF1 is reported to be overexpressed in CRC and plays a vital oncogenic role in CRC (146, 167). Silencing YTHDF1 not only reduces the number of colon spheres but also causes significant downregulation of cancer stem cell markers, including CD44, CD133, OCT4, ALDH1, and Lgr5 in CRC cells. These findings indicate that YTHDF1 plays a key role in maintaining CRC stemness, which is analogous to the role of METTL3 in CRC (145). YTHDF1 is found to regulate the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway in CRC as well (167). Silencing YTHDF1 leads to reduction of the expressions of the nonphospho (active)-β-catenin and the Wnt/β-catenin downstream targets, including c-JUN, CCND1, and CD44, and thus downregulates the β-catenin nuclear signals activity.

Recent study has revealed that the m6A modification in a circular RNA (circRNA), circNSUN2 that maps to the chromosome 5p15 amplicon in CRC, has an important role for promoting CRC liver metastasis (168). Mechanically, circNSUN2 contains an m6A motif within its exon 5-exon 4 junction sequence where it can be modified by METTL3, and then YTHDC1 facilitates the nuclear export of m6A-containing circNSUN2. In cytoplasm, circNSUN2 stabilizes its downstream target HMGA2 mRNA by forming the complex with an m6A reader IGF2BP2, and promoting the EMT process and liver metastasis in CRC. Interestingly, upregulation of circNSUN2 in CRC is in an METTL3-independent manner, and silencing METTL3 does not change total expression of circNSUN2 nor increases the nuclear content or reduces the cytoplasmic content.

Mutations that cause the gain or loss of methylation sites are found to involve in generation, progression and drug resistance of GICs. Uddin et al. (151) have shown that the point-mutated codon 273 (G > A) of p53 pre-mRNA promotes expression of mutant protein in a METTL3- and m6A-dependent manner, while the upregulated METTL3 is partly caused by a serial ceramide glycosylation mechanism. The mutant protein is found to lose its original role of cancer suppressing and obtain many oncogenic functions to generate the acquired multidrug resistance in CRC. Further, they showed that either silencing METTL3 by small interfering RNA (siRNA), or inhibiting RNA methylation with neplanocin A, or suppressing ceramide glycosylation is able to re-sensitize the resistant CRC cells to anticancer drugs. Recently, Tian et al. (169) revealed another type of mutations that are related to the m6A modification, the missense variant rs8100241 (G > A) located in ANKLE1. Overexpression of the rs8100241[A] allele significantly increased the ANKLE1 m6A level that was catalyzed by writers METTL3/14 and WTAP and recognized by reader of YTHDF1, thus the dysregulated ANKLE1 protein is facilitated compared to that of rs8100241[G] allele, which is significantly related to susceptibility of CRC.

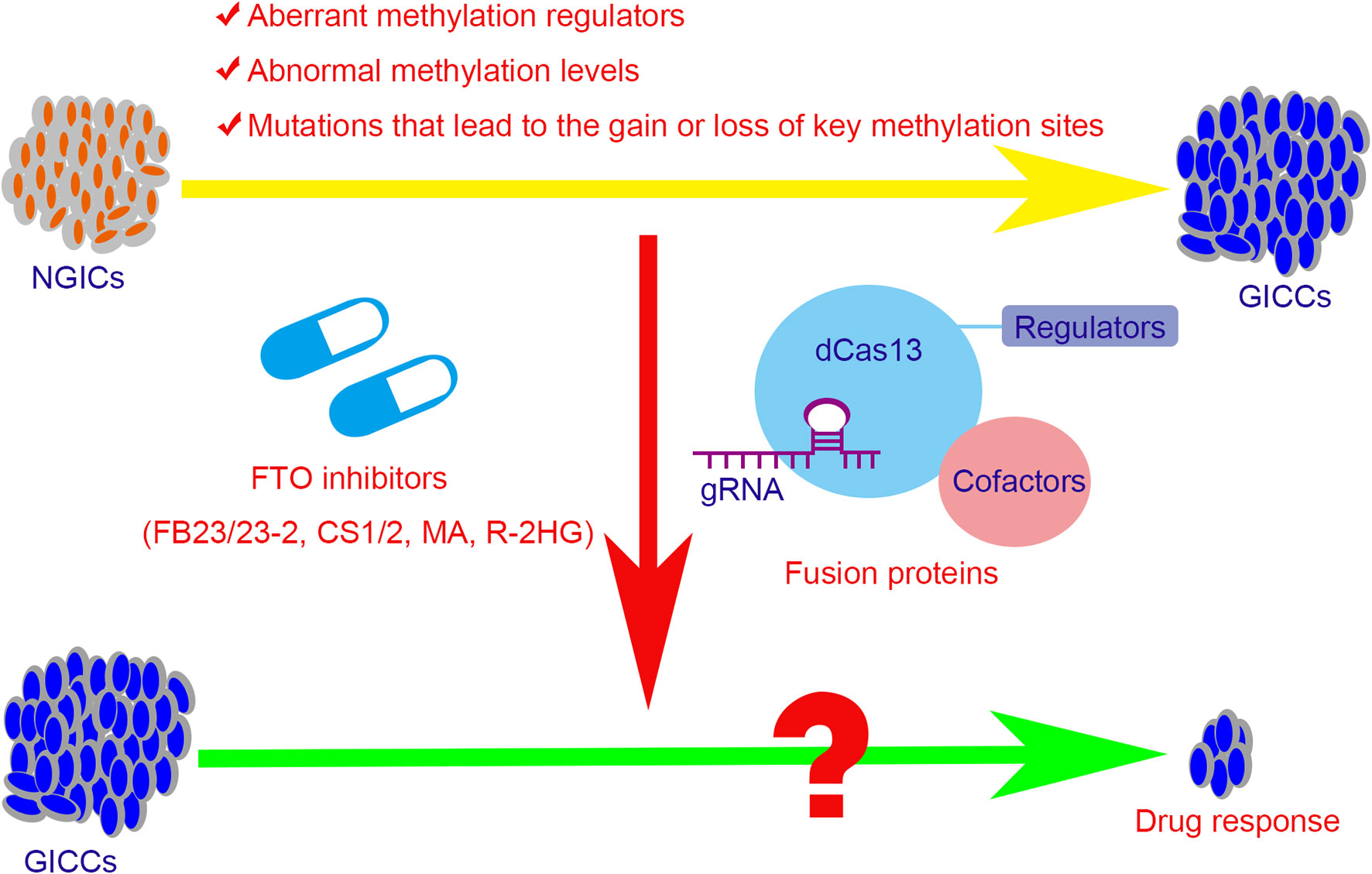

In view of the relationship between methylation modifications and tumors, new tumor treatment strategies have been explored. Meclofenamic acid (MA), the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, was found to compete with FTO binding for the m6A-containing nucleic acid and functions as FTO inhibitor (170). R-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2HG), generated from mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 (IDH1/2) enzymes, was also found to inhibit FTO activity and increase the m6A level in cells, which in turn decreases the stability of MYC/CEBPA and thus block the MYC pathways (171). Recently, two synthetic high-efficient FTO inhibitors are identified. Chen et al. (172) have developed two potent FTO inhibitors FB23 and FB23-2 and showed that they could directly bind to FTO and selectively block the m6A demethylase activity of FTO. Subsequently, they further developed two others promising FTO inhibitors, namely CS1 and CS2, which exhibit strong anti-tumor effects in multiple types of cancers. For leukemia cells, FTO inhibitors can not only block the signal axis of FTO/m6A/MYC/CEBPA and inhibit the self-renewal of cancer stem cells, but also suppress the expression of immune checkpoint LILRB4 and immune evasion thus enhancing the cytotoxicity of T cells (173). However, the inhibitors of other m6A regulators such as METTL3, METTL14, or WTAP have not been systematically developed. Moreover, targeted RNA demethylation or methylation by the engineered dCas13-containing fusion proteins may hold the potential to develop a treatment regimen for GICs (174–176) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The potential therapeutic strategies for the GICs with abnormal methylation regulators or levels. The aberrant methylation regulators, abnormal methylation levels, and the mutations that lead to the gain or loss of key methylation sites contribute partly in tumorigenesis, progression, and drug resistance in GICs. The potential therapeutic strategies include the small molecule inhibitors of the regulators and the targeted fusion proteins that based on CRISPR/Cas 13 system. FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; NGICs, normal gastrointestinal cells; GICCs, gastrointestinal cancer cells; gRNA, guide RNA; dCas13, inactive Cas13 enzyme; MA, meclofenamic acid; R-2HG, R-2-hydroxyglutarate.

Since 2011, extensive studies have worked on the methylation modifications in RNAs, providing an extensive and accumulating database including m6A, m6Am, and m1A. The formation of m1A, m6A, and m6Am is no substantial correlated, and the roles of m6Am and m1A are partly similar to that of m6A, by which the m6Am and m6A modifications are demethylated by FTO. It would be interesting to measure the interference produced by m6Am and m1A during the m6A exploration process.

The dysregulation of RNA methylation has been linked to the abnormalities in the MYC pathway, the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, the ErbB2 pathway, the PI3K-AKT pathway and EMT in many human cancers. For GICs, the upregulated METTL3 and erasers are mainly involved in the MAPK/ERK pathway, the CCNE1 pathway, the SOX2/tumor stemness pathway, glycolipid metabolism, and EMT and to facilitate CRC formation and progression, whereas the low expression of METTL14 mediates the lncRNA XIST axis and the miR-375/YAP1 and SP1 axis to promote CRC progression. Moreover, the upregulated readers, IGF2BP2, YTHDF3, and YTHDF1, represent as poor prognosis factors in CRC by regulating the lncRNA LINRIS/IGF2BP2/MYC/glycolysis axis, the lncRNA GAS5/YAP/YTHDF3 axis and the YTHDF1/Wnt/β-Catenin and tumor stemness pathway respectively (Table 3). Mutations that cause the gain of methylation sites, including the point-mutated codon 273 (G > A) of p53 pre-mRNA and the missense variant rs8100241 (G > A) located in ANKLE1, are also linked to tumorigenesis, progression and drug resistance in CRC.

However, there are some controversies and confusions in the RNA methylation: i) Binding mode of YTHDF proteins on different mRNAs or a single mRNA. ii) Affinity towards the m6A and m6Am sites by FTO. iii) mRNA stability affected by the m6Am modification. iv) The role of the m1A modification in RNA translation. v) Specificity of the targets regulated by the methylation regulators. vi) The distinguish expression signatures of both the writers and the erasers in certain type of GICs, and their downstream targets. viii) Inhibitors for METTL3 and readers.

GW and WH proposed these ideas and valuable comments, and QL drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073869, 81701834, 81871994); Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2019A050510019, 2019B151502063); Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Construction Foundation (2017B030314030, 2020B1212060034); Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Program (202002020051, 201902020018); National Engineering Research Centre for New Drug and Drug ability Evaluation, Seed Program of Guangdong Province (2017B090903004).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell (2017) 169(7):1187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045

2. Pan T. Modifications and functional genomics of human transfer RNA. Cell Res (2018) 28(4):395–404. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0013-y

3. Taoka M, Nobe Y, Yamaki Y, Sato K, Ishikawa H, Izumikawa K, et al. Landscape of the complete RNA chemical modifications in the human 80S ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46(18):9289–98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky811

4. Linder B, Grozhik AV, Olarerin-George AO, Meydan C, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat Methods (2015) 12(8):767–72. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3453

5. Yang Y, Fan X, Mao M, Song X, Wu P, Zhang Y, et al. Extensive translation of circular RNAs driven by N-methyladenosine. Cell Res (2017) 27(5):626–41. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.31

6. Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature (2015) 518(7540):560–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14234

7. Alarcón CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature (2015) 519(7544):482–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14281

8. Helm M, Motorin Y. Detecting RNA modifications in the epitranscriptome: predict and validate. Nat Rev Genet (2017) 18(5):275–91. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.169

9. Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, Piatkowski P, Baginski B, Wirecki TK, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46(D1):D303–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1030

10. Arango D, Sturgill D, Alhusaini N, Dillman AA, Sweet TJ, Hanson G, et al. Acetylation of cytidine in mRNA promotes translation efficiency. Cell (2018) 175(7):1872–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.030

11. Grozhik AV, Jaffrey SR. Distinguishing RNA modifications from noise in epitranscriptome maps. Nat Chem Biol (2018) 14(3):215–25. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2546

12. Gilbert WV, Bell TA, Schaening C. Messenger RNA modifications: form, distribution, and function. Science (New York NY) (2016) 352(6292):1408–12. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8711

13. Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1974) 71(10):3971–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971

14. Perry RP, Kelley DE. Existence of methylated messenger RNA in mouse L cells. Cell (1974) 1:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90153-6

15. Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5’ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell (1975) 4(4):379–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0

16. Niu Y, Wan A, Lin Z, Lu X, Wan GN. N (6)-methyladenosine modification: a novel pharmacological target for anti-cancer drug development. Acta Pharm Sin B (2018) 8(6):833–43. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.06.001

17. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2018) 68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

18. Jaffrey SR, Kharas MG. Emerging links between mA and misregulated mRNA methylation in cancer. Genome Med (2017) 9(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0395-8

19. Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol (2011) 7(12):885–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687

20. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang C-M, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell (2013) 49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015

21. Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell (2012) 149(7):1635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003

22. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature (2012) 485(7397):201–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11112

23. Liu N, Parisien M, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Pan T. Probing N6-methyladenosine RNA modification status at single nucleotide resolution in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA (New York NY) (2013) 19(12):1848–56. doi: 10.1261/rna.041178.113

24. Molinie B, Wang J, Lim KS, Hillebrand R, Lu Z-X, Van Wittenberghe N, et al. m(6)A-LAIC-seq reveals the census and complexity of the m(6)A epitranscriptome. Nat Methods (2016) 13(8):692–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3898

25. Meyer KD. DART-seq: an antibody-free method for global mA detection. Nat Methods (2019) 16(12):1275–80. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0570-0

26. Garcia-Campos MA, Edelheit S, Toth U, Safra M, Shachar R, Viukov S, et al. Deciphering the “mA Code” via antibody-independent quantitative profiling. Cell (2019) 178(3):731–47.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.013

27. Zhang Z, Chen LQ, Zhao YL, Yang CG, Roundtree IA, Zhang Z, et al. Single-base mapping of mA by an antibody-independent method. Sci Adv (2019) 5(7):eaax0250. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0250

28. Shu X, Cao J, Cheng M, Xiang S, Gao M, Li T, et al. A metabolic labeling method detects mA transcriptome-wide at single base resolution. Nat Chem Biol (2020) 16(8):887–895. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0526-9

29. Wang Y, Xiao Y, Dong S, Yu Q, Jia G. Antibody-free enzyme-assisted chemical approach for detection of N-methyladenosine. Nat Chem Biol (2020) 16(8):896–903. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0525-x

30. Liu H, Begik O, Lucas MC, Ramirez JM, Mason CE, Wiener D, et al. Accurate detection of mA RNA modifications in native RNA sequences. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):4079. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11713-9

31. Rottman F, Shatkin AJ, Perry RP. Sequences containing methylated nucleotides at the 5’ termini of messenger RNAs: possible implications for processing. Cell (1974) 3(3):197–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90131-7

32. Perry RP, Kelley DE, Friderici K, Rottman F. The methylated constituents of L cell messenger RNA: evidence for an unusual cluster at the 5’ terminus. Cell (1975) 4(4):387–94. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90159-2

33. Harper JE, Miceli SM, Roberts RJ, Manley JL. Sequence specificity of the human mRNA N6-adenosine methylase in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res (1990) 18(19):5735–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5735

34. Ke S, Pandya-Jones A, Saito Y, Fak JJ, Vågbø CB, Geula S, et al. mA mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev (2017) 31(10):990–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.301036.117

35. Bokar JA, Rath-Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R, Narayan P, Rottman F. Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem (1994) 269(26):17697–704.

36. Rottman FM, Bokar JA, Narayan P, Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R. N6-adenosine methylation in mRNA: substrate specificity and enzyme complexity. Biochimie (1994) 76(12):1109–14. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90038-8

37. Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA (New York NY) (1997) 3(11):1233–47.

38. Bujnicki JM, Feder M, Radlinska M, Blumenthal RM. Structure prediction and phylogenetic analysis of a functionally diverse family of proteins homologous to the MT-A70 subunit of the human mRNA:m(6)A methyltransferase. J Mol Evol (2002) 55(4):431–44. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2339-8

39. Ping X-L, Sun BF, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang WJ, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res (2014) 24(2):177–89. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3

40. Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol (2014) 16(2):191–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902

41. Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol (2014) 10(2):93–5. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432

42. Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet (2014) 15(5):293–306. doi: 10.1038/nrg3724

43. Śledź P, Jinek M. Structural insights into the molecular mechanism of the m(6)A writer complex. eLife (2016) 5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18434

44. Wang X, Feng J, Xue Y, Guan Z, Zhang D, Liu Z, et al. Structural basis of N(6)-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature (2016) 534(7608):575–8. doi: 10.1038/nature18298

45. Wang P, Doxtader KA, Nam Y. Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol Cell (2016) 63(2):306–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041

46. Huang H, Weng H, Zhou K, Wu T, Zhao BS, Sun M, et al. Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides mA RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature (2019) 567(7748):414–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1016-7

47. Ortega A, Niksic M, Bachi A, Wilm M, Sánchez L, Hastie N, et al. Biochemical function of female-lethal (2)D/Wilms’ tumor suppressor-1-associated proteins in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(5):3040–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210737200

48. Zhong S, Li H, Bodi Z, Button J, Vespa L, Herzog M, et al. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell (2008) 20(5):1278–88. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058883

49. Small TW, Penalva LO, Pickering JG. Vascular biology and the sex of flies: regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein. Trends Cardiovasc Med (2007) 17(7):230–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.08.002

50. Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Wang T, Maciag K, Bushkin GG, et al. Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5’ sites. Cell Rep (2014) 8(1):284–96. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.048

51. Yue Y, Liu J, Cui X, Cao J, Luo G, Zhang Z, et al. VIRMA mediates preferential mA mRNA methylation in 3’UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov (2018) 4:10. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0019-0

52. Wen J, Lv R, Ma H, Shen H, He C, Wang J, et al. Zc3h13 Regulates nuclear RNA mA methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol Cell (2018) 69(6):1028–38.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.015

53. Patil DP, Chen CK, Pickering BF, Chow A, Jackson C, Guttman M, et al. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature (2016) 537(7620):369–73. doi: 10.1038/nature19342

54. Aguilo F, Zhang F, Sancho A, Fidalgo M, Di Cecilia S, Vashisht A, et al. Coordination of m(6)A mRNA methylation and gene transcription by ZFP217 regulates pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell (2015) 17(6):689–704. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.005

55. Bertero A, Brown S, Madrigal P, Osnato A, Ortmann D, Yiangou L, et al. The SMAD2/3 interactome reveals that TGFβ controls mA mRNA methylation in pluripotency. Nature (2018) 555(7695):256–9. doi: 10.1038/nature25784

56. Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, Shi J, Millán-Zambrano G, Robson SC, et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by mA-dependent translation control. Nature (2017) 552(7683):126–31. doi: 10.1038/nature24678

57. Brown JA, Kinzig CG, DeGregorio SJ, Steitz JA. Methyltransferase-like protein 16 binds the 3’-terminal triple helix of MALAT1 long noncoding RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2016) 113(49):14013–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614759113

58. Ma H, Wang X, Cai J, Dai Q, Natchiar SK, Lv R, et al. Publisher Correction: N-Methyladenosine methyltransferase ZCCHC4 mediates ribosomal RNA methylation. Nat Chem Biol (2019) 15(5):549. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0233-6

59. van Tran N, Ernst FGM, Hawley BR, Zorbas C, Ulryck N, Hackert P, et al. The human 18S rRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL5 is stabilized by TRMT112. Nucleic Acids Res (2019) 47(15):7719–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz619

60. Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science (New York NY) (2007) 316(5826):889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634

61. Peters T, Ausmeier K, Rüther U. Cloning of Fatso (Fto), a novel gene deleted by the Fused toes (Ft) mouse mutation. Mamm Genome (1999) 10(10):983–6. doi: 10.1007/s003359901144

62. Sanchez-Pulido L, Andrade-Navarro MA. The FTO (fat mass and obesity associated) gene codes for a novel member of the non-heme dioxygenase superfamily. BMC Biochem (2007) 8:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-8-23

63. Gerken T, Girard CA, Tung Y-CL, Webby CJ, Saudek V, Hewitson KS, et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science (New York NY) (2007) 318(5855):1469–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1151710

64. Jia G, Yang C-G, Yang S, Jian X, Yi C, Zhou Z, et al. Oxidative demethylation of 3-methylthymine and 3-methyluracil in single-stranded DNA and RNA by mouse and human FTO. FEBS Lett (2008) 582(23-24):3313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.019

65. Fu Y, Jia G, Pang X, Wang RN, Wang X, Li CJ, et al. FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat Commun (2013) 4:1798. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2822

66. Aravind L, Koonin EV. The DNA-repair protein AlkB, EGL-9, and leprecan define new families of 2-oxoglutarate- and iron-dependent dioxygenases. Genome Biol (2001) 2(3):RESEARCH0007. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-3-research0007

67. Falnes PO, Johansen RF, Seeberg E. AlkB-mediated oxidative demethylation reverses DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Nature (2002) 419(6903):178–82. doi: 10.1038/nature01048

68. Trewick SC, Henshaw TF, Hausinger RP, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B. Oxidative demethylation by Escherichia coli AlkB directly reverts DNA base damage. Nature (2002) 419(6903):174–8. doi: 10.1038/nature00908

69. Yu B, Edstrom WC, Benach J, Hamuro Y, Weber PC, Gibney BR, et al. Crystal structures of catalytic complexes of the oxidative DNA/RNA repair enzyme AlkB. Nature (2006) 439(7078):879–84. doi: 10.1038/nature04561

70. Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nat Rev Genet (2006) 7(9):715–27. doi: 10.1038/nrg1945

71. Imai Y, Matsuo N, Ogawa S, Tohyama M, Takagi T. Cloning of a gene, YT521, for a novel RNA splicing-related protein induced by hypoxia/reoxygenation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res (1998) 53(1-2):33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(97)00262-3

72. Hartmann AM, Nayler O, Schwaiger FW, Obermeier A, Stamm S. The interaction and colocalization of Sam68 with the splicing-associated factor YT521-B in nuclear dots is regulated by the Src family kinase p59(fyn). Mol Biol Cell (1999) 10(11):3909–26. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3909

73. Stoilov P, Rafalska I, Stamm S. YTH: a new domain in nuclear proteins. Trends Biochem Sci (2002) 27(10):495–7. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02189-8

74. Nayler O, Hartmann AM, Stamm S. The ER repeat protein YT521-B localizes to a novel subnuclear compartment. J Cell Biol (2000) 150(5):949–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.949

75. Xu C, Wang X, Liu K, Roundtree IA, Tempel W, Li Y, et al. Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat Chem Biol (2014) 10(11):927–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1654

76. Zhu T, Roundtree IA, Wang P, Wang X, Wang L, Sun C, et al. Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res (2014) 24(12):1493–6. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.152

77. Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, Chen YS, Hao YJ, Sun BF, et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol Cell (2016) 61(4):507–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012

78. Roundtree IA, Luo G-Z, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhou T, Cui Y, et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife (2017) 6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.31311

79. He Y, Smith R. Nuclear functions of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A/B. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS (2009) 66(7):1239–56. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8532-1

80. Alarcón CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m(6)A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell (2015) 162(6):1299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011

81. Wu B, Su S, Patil DP, Liu H, Gan J, Jaffrey SR, et al. Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):420. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02770-z

82. Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T, et al. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res (2017) 45(10):6051–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx141

83. Zhou KI, Shi H, Lyu R, Wylder AC, Matuszek Ż, Pan JN, et al. Regulation of Co-transcriptional Pre-mRNA Splicing by mA through the Low-Complexity Protein hnRNPG. Mol Cell (2019) 76(1). doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.005

84. Luo S, Tong L. Molecular basis for the recognition of methylated adenines in RNA by the eukaryotic YTH domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111(38):13834–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412742111

85. Theler D, Dominguez C, Blatter M, Boudet J, Allain FHT. Solution structure of the YTH domain in complex with N6-methyladenosine RNA: a reader of methylated RNA. Nucleic Acids Res (2014) 42(22):13911–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1116

86. Patil DP, Pickering BF, Jaffrey SR. Reading mA in the Transcriptome: mA-Binding Proteins. Trends Cell Biol (2018) 28(2):113–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.10.001

87. Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature (2014) 505(7481):117–20. doi: 10.1038/nature12730

88. Du H, Zhao Y, He J, Zhang Y, Xi H, Liu M, et al. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat Commun (2016) 7:12626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12626

89. Ries RJ, Zaccara S, Klein P, Olarerin-George A, Namkoong S, Pickering BF, et al. mA enhances the phase separation potential of mRNA. Nature (2019) 571(7765):424–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1374-1

90. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell (2015) 161(6):1388–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014

91. Li A, Chen Y-S, Ping X-L, Yang X, Xiao W, Yang Y, et al. Cytoplasmic mA reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res (2017) 27(3):444–7. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.10

92. Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res (2017) 27(3):315–28. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.15

93. Zaccara S, Jaffrey SR. A unified model for the function of YTHDF proteins in regulating mA-modified mRNA. Cell (2020) 181(7):1582–95.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.012

94. Mao Y, Dong L, Liu X-M, Guo J, Ma H, Shen B, et al. mA in mRNA coding regions promotes translation via the RNA helicase-containing YTHDC2. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):5332. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13317-9

95. Hsu PJ, Zhu Y, Ma H, Guo Y, Shi X, Liu Y, et al. Ythdc2 is an N-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res (2017) 27(9):1115–27. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.99

96. Zhou B, Liu C, Xu L, Yuan Y, Zhao J, Zhao W, et al. N-methyladenosine reader protein Ythdc2 suppresses liver steatosis via regulation of mRNA stability of lipogenic genes. Hepatol (Baltimore Md) (2020). doi: 10.1002/hep.31220

97. Nielsen J, Christiansen J, Lykke-Andersen J, Johnsen AH, Wewer UM, Nielsen FC. A family of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding proteins represses translation in late development. Mol Cell Biol (1999) 19(2):1262–70. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.2.1262

98. Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu H, et al. Recognition of RNA N-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20(3):285–95. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z

99. Zhang F, Kang Y, Wang M, Li Y, Xu T, Yang W, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein modulates the stability of its m6A-marked messenger RNA targets. Hum Mol Genet (2018) 27(22):3936–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy292

100. Wu R, Li A, Sun B, Sun JG, Zhang J, Zhang T, et al. A novel mA reader Prrc2a controls oligodendroglial specification and myelination. Cell Res (2019) 29(1):23–41. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0113-8

101. Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI. The m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol Cell (2016) 62(3):335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.021

102. Choe J, Lin S, Zhang W, Liu Q, Wang L, Ramirez-Moya J, et al. mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature (2018) 561(7724):556–60. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0538-8

103. Adams JM, Cory S. Modified nucleosides and bizarre 5’-termini in mouse myeloma mRNA. Nature (1975) 255(5503):28–33. doi: 10.1038/255028a0

104. Furuichi Y, Morgan M, Shatkin AJ, Jelinek W, Salditt-Georgieff M, Darnell JE, et al. Methylated, blocked 5 termini in HeLa cell mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1975) 72(5):1904–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1904

105. Wei C, Gershowitz A, Moss B. N6, O2’-dimethyladenosine a novel methylated ribonucleoside next to the 5’ terminal of animal cell and virus mRNAs. Nature (1975) 257(5523):251–3. doi: 10.1038/257251a0

106. Akichika S, Hirano S, Shichino Y, Suzuki T, Nishimasu H, Ishitani R, et al. Cap-specific terminal -methylation of RNA by an RNA polymerase II-associated methyltransferase. Science (New York NY) (2019) 363(6423). doi: 10.1126/science.aav0080

107. Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. 5’-Terminal and internal methylated nucleotide sequences in HeLa cell mRNA. Biochemistry (1976) 15(2):397–401. doi: 10.1021/bi00647a024

108. Liu JE, Li K, Cai J, Zhang M, Zhang X, Xiong X, et al. Landscape and Regulation of mA and mAm Methylome across Human and Mouse Tissues. Mol Cell (2020) 77(2):426–40.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.032

109. Boulias K, Toczydłowska-Socha D, Hawley BR, Liberman N, Takashima K, Zaccara S, et al. Identification of the mAm Methyltransferase PCIF1 Reveals the Location and Functions of mAm in the Transcriptome. Mol Cell (2019) 75(3):631–43.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.006

110. Ringeard M, Marchand V, Decroly E, Motorin Y, Bennasser Y. FTSJ3 is an RNA 2’-O-methyltransferase recruited by HIV to avoid innate immune sensing. Nature (2019) 565(7740):500–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0841-4

111. Liang H, Jiao Z, Rong W, Qu S, Liao Z, Sun X, et al. 3’-Terminal 2’-O-methylation of lung cancer miR-21-5p enhances its stability and association with Argonaute 2. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48(13):7027–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa504

112. Sun H, Zhang M, Li K, Bai D, Yi C. Cap-specific, terminal N-methylation by a mammalian mAm methyltransferase. Cell Res (2019) 29(1):80–2. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0117-4

113. Fan H, Sakuraba K, Komuro A, Kato S, Harada F, Hirose Y. PCIF1, a novel human WW domain-containing protein, interacts with the phosphorylated RNA polymerase II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2003) 301(2):378–85. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)03015-2

114. Goh YT, Koh CWQ, Sim DY, Roca X, Goh WSS. METTL4 catalyzes m6Am methylation in U2 snRNA to regulate pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48(16):9250–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa684

115. Mauer J, Luo X, Blanjoie A, Jiao X, Grozhik AV, Patil DP, et al. Reversible methylation of mA in the 5’ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature (2017) 541(7637):371–5. doi: 10.1038/nature21022

116. Zhang X, Wei LH, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Liu J, Zhang W, et al. Structural insights into FTO’s catalytic mechanism for the demethylation of multiple RNA substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2019) 116(8):2919–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820574116

117. Wei J, Liu F, Lu Z, Fei Q, Ai Y, He PC, et al. Differential mA, mA, and mA Demethylation Mediated by FTO in the Cell Nucleus and Cytoplasm. Mol Cell (2018) 71(6):973–85.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011

118. Sendinc E, Valle-Garcia D, Dhall A, Chen H, Henriques T, Navarrete-Perea J, et al. PCIF1 Catalyzes m6Am mRNA Methylation to Regulate Gene Expression. Mol Cell (2019) 75(3):620–30.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.05.030

119. Dunn DB. The occurrence of 1-methyladenine in ribonucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta (1961) 46:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90668-0

120. Macon JB, Wolfenden R. 1-Methyladenosine. Dimroth rearrangement and reversible reduction. Biochemistry (1968) 7(10):3453–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00850a021

121. El Yacoubi B, Bailly M, de Crécy-Lagard V. Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs. Annu Rev Genet (2012) 46:69–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641

122. Sharma S, Watzinger P, Kötter P, Entian KD. Identification of a novel methyltransferase, Bmt2, responsible for the N-1-methyl-adenosine base modification of 25S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res (2013) 41(10):5428–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt195

123. Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben-Haim MS, et al. The dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature (2016) 530(7591):441–6. doi: 10.1038/nature16998

124. Li X, Xiong X, Wang K, Wang L, Shu X, Ma S, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol (2016) 12(5):311–6. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2040

125. Li X, Xiong X, Zhang M, Wang K, Chen Y, Zhou J, et al. Base-resolution mapping reveals distinct mA methylome in nuclear- and mitochondrial-encoded transcripts. Mol Cell (2017) 68(5):993–1005.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.019

126. Safra M, Sas-Chen A, Nir R, Winkler R, Nachshon A, Bar-Yaacov D, et al. The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature (2017) 551(7679):251–5. doi: 10.1038/nature24456

127. Chujo T, Suzuki T. Trmt61B is a methyltransferase responsible for 1-methyladenosine at position 58 of human mitochondrial tRNAs. RNA (New York NY) (2012) 18(12):2269–76. doi: 10.1261/rna.035600.112

128. Ozanick S, Krecic A, Andersland J, Anderson JT. The bipartite structure of the tRNA m1A58 methyltransferase from S. cerevisiae is conserved in humans. RNA (New York NY) (2005) 11(8):1281–90. doi: 10.1261/rna.5040605

129. Vilardo E, Nachbagauer C, Buzet A, Taschner A, Holzmann J. A subcomplex of human mitochondrial RNase P is a bifunctional methyltransferase–extensive moonlighting in mitochondrial tRNA biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res (2012) 40(22):11583–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks910

130. Scheitl CPM, Ghaem Maghami M, Lenz AK, Höbartner C, et al. Site-specific RNA methylation by a methyltransferase ribozyme. Nature (2020) 587(7835):663–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2854-z

131. Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, Wang X, Fu Y, Wei J, et al. ALKBH1-Mediated tRNA Demethylation Regulates Translation. Cell (2016) 167(3):1897. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.038

132. Aas PA, Otterlei M, Falnes PO, Vågbø CB, Skorpen F, Akbari M, et al. Human and bacterial oxidative demethylases repair alkylation damage in both RNA and DNA. Nature (2003) 421(6925):859–63. doi: 10.1038/nature01363

133. Ougland R, Zhang C-M, Liiv A, Johansen RF, Seeberg E, Hou YM, et al. AlkB restores the biological function of mRNA and tRNA inactivated by chemical methylation. Mol Cell (2004) 16(1):107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.002

134. Parsyan A, Svitkin Y, Shahbazian D, Gkogkas C, Lasko P, Merrick WC, et al. mRNA helicases: the tacticians of translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2011) 12(4):235–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm3083

135. Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell (2009) 136(4):731–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042

136. Zheng Q, Gan H, Yang F, Yao Y, Hao F, et al. Cytoplasmic mA reader YTHDF3 inhibits trophoblast invasion by downregulation of mA-methylated IGF1R. Cell Discov (2020) 6:12. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0144-4

137. Seo KW, Kleiner RE. YTHDF2 Recognition of N-Methyladenosine (mA)-Modified RNA Is Associated with Transcript Destabilization. ACS Chem Biol (2020) 15(1):132–9. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00655

138. He L, Li H, Wu A, Peng Y, Shu G, Yin G, et al. Functions of N6-methyladenosine and its role in cancer. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1109-9

139. Yue B, Yue B, Song C, Yang L, Cui R, Cheng X, Zhang Z, et al. METTL3-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification is critical for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric cancer. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1065-4

140. Wang Q, Chen C, Ding Q, Zhao Y, Wang Z, Chen J, et al. METTL3-mediated mA modification of HDGF mRNA promotes gastric cancer progression and has prognostic significance. Gut (2019) 69(7):1193–205. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319639

141. He H, Wu W, Sun Z, Chai L, et al. MiR-4429 prevented gastric cancer progression through targeting METTL3 to inhibit mA-caused stabilization of SEC62. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2019) 517(4):581–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.058

142. Liu T, Yang S, Sui J, Xu SY, Cheng YP, Shen B, et al. Dysregulated N6-methyladenosine methylation writer METTL3 contributes to the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer. J Cell Physiol (2020) 235(1):548–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28994

143. Yang D-D, Chen Z-H, Yu K, Lu JH, Wu QN, Wang Y, et al. METTL3 Promotes the Progression of Gastric Cancer via Targeting the MYC Pathway. Front Oncol (2020) 10:115. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00115

144. Zhu L, Zhu Y, Han S, Chen M, Song P, Dai D, et al. Impaired autophagic degradation of lncRNA ARHGAP5-AS1 promotes chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis (2019) 10(6):383. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1585-2

145. Li T, Hu PS, Zuo Z, Lin JF, Li X, Wu QN, et al. METTL3 facilitates tumor progression via an mA-IGF2BP2-dependent mechanism in colorectal carcinoma. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1038-7

146. Liu X, Liu L, Dong Z, Li J, Yu Y, Chen X, et al. Expression patterns and prognostic value of mA-related genes in colorectal cancer. Am J Trans Res (2019) 11(7):3972–91.

147. Peng W, Li J, Chen R, Gu Q, Yang P, Qian W, et al. Upregulated METTL3 promotes metastasis of colorectal Cancer via miR-1246/SPRED2/MAPK signaling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res CR (2019) 38(1):393. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1408-4

148. Shen C, Xuan B, Yan T, Ma Y, Xu P, Tian X, et al. mA-dependent glycolysis enhances colorectal cancer progression. Mol Cancer (2020) 19(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01190-w

149. Zhu W, Si Y, Xu J, Lin Y, Wang J-Z, Cao M, et al. Methyltransferase like 3 promotes colorectal cancer proliferation by stabilizing CCNE1 mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner. J Cell Mol Med (2020) 24(6):3521–33. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15042

150. Deng R, Cheng Y, Ye S, Zhang J, Huang R, Li P, et al. mA methyltransferase METTL3 suppresses colorectal cancer proliferation and migration through p38/ERK pathways. OncoTarg Ther (2019) 12:4391–402. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S201052

151. Uddin MB, Roy KR, Hosain SB, Khiste SK, Hill RA, Jois SD, et al. An N-methyladenosine at the transited codon 273 of p53 pre-mRNA promotes the expression of R273H mutant protein and drug resistance of cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol (2019) 160:134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.12.014

152. Boumahdi S, Driessens G, Lapouge G, Rorive S, Nassar D, Le Mercier M, et al. SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature (2014) 511(7508):246–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13305

153. Guan K, Liu X, Li J, Ding Y, Li J, Cui G, et al. Expression Status And Prognostic Value Of M6A-associated Genes in Gastric Cancer. J Cancer (2020) 11(10):3027–40. doi: 10.7150/jca.40866

154. Li H, Su Q, Li B, Lan L, Wang C, Li W, et al. High expression of WTAP leads to poor prognosis of gastric cancer by influencing tumour-associated T lymphocyte infiltration. J Cell Mol Med (2020) 24(8):4452–65. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15104

155. Su Y, Huang J, Hu J. mA RNA Methylation regulators contribute to malignant progression and have clinical prognostic impact in gastric cancer. Front Oncol (2019) 9:1038. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01038

156. Zhang C, Zhang M, Ge S, Huang W, Lin X, Gao J, et al. Reduced m6A modification predicts malignant phenotypes and augmented Wnt/PI3K-Akt signaling in gastric cancer. Cancer Med (2019) 8(10):4766–81. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2360

157. Yang X, Zhang S, He C, Xue P, Zhang L, He Z, et al. METTL14 suppresses proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer by down-regulating oncogenic long non-coding RNA XIST. Mol Cancer (2020) 19(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1146-4

158. Chen D-L, Chen LZ, Lu YX, Zhang DS, Zeng ZL, Pan ZZ, et al. Long noncoding RNA XIST expedites metastasis and modulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis (2017) 8(8):e3011. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.421

159. Chen X, Xu M, Xu X, Zeng K, Liu X, Sun L, et al. METTL14 Suppresses CRC progression via regulating N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary miR-375 processing. Mol Ther J Am Soc Gene Ther (2020) 28(2):599–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.11.016

160. Li Y, Zheng D, Wang F, Xu Y, Yu H, Zhang H. Expression of demethylase genes, FTO and ALKBH1, is associated with prognosis of gastric cancer. Digest Dis Sci (2019) 64(6):1503–13. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5452-2

161. Zhao Y, Zhao Q, Kaboli PJ, Shen J, Li M, Wu X, et al. m1A regulated genes modulate PI3K/AKT/mTOR and ErbB pathways in gastrointestinal cancer. Trans Oncol (2019) 12(10):1323–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2019.06.007

162. Zhang J, Guo S, Piao HY, Wang Y, Wu Y, Meng XY, et al. ALKBH5 promotes invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer by decreasing methylation of the lncRNA NEAT1. J Physiol Biochem (2019) 75(3):379–89. doi: 10.1007/s13105-019-00690-8

163. Wu Y, Yang X, Chen Z, Tian L, Jiang G, Chen F, et al. m6A-induced lncRNA RP11 triggers the dissemination of colorectal cancer cells via upregulation of Zeb1. Mol Cancer (2019) 18(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1014-2