95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Oncol. , 23 June 2020

Sec. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 10 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01006

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Association Between Night-Shift Work and Cancer Risk: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Background: Nightshift work introduces light at night and causes circadian rhythm among night workers, who are considered to be at increased risk of cancer. However, in the last 2 years, nine population-based studies reported insignificant associations between night-shift work and cancer risks. We aimed to conduct an updated systematic review and meta-analysis to ascertain the effect of night-shift work on the incidence of cancers.

Methods: Our protocol was registered in PROSPERO and complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science databases were used to comprehensively search studies published up to May 31, 2019. The random-effect model (Der Simonian-Laird method) was carried out to combine the risk estimates of night-shift work for cancers. The dose-response meta-analysis was performed to verify whether the association was in a dose-dependent manner.

Results: Our literature searching retrieved 1,660 publications. Included in the meta-analyses were 57 eligible studies with 8,477,849 participants (mean age 55 years; 2,560,886 men, 4,220,154 women, and 1,696,809 not mentioned). The pooled results showed that night-shift work was not associated with the risk of breast cancer (OR = 1.009, 95% CI = 0.984–1.033), prostate cancer (OR = 1.027, 95% CI = 0.982–1.071), ovarian cancer (OR = 1.027, 95% CI = 0.942–1.113), pancreatic cancer (OR = 1.007, 95% CI = 0.910–1.104), colorectal cancer (OR = 1.016, 95% CI = 0.964–1.068), non-Hodgkin's lymph (OR = 1.046, 95% CI = 0.994–1.098), and stomach cancer (OR = 1.064, 95% CI = 0.971–1.157), while night-shift work was associated with a reduction of lung cancer (OR = 0.949, 95% CI = 0.903–0.996), and skin cancer (OR = 0.916, 95% CI = 0.879–0.953). The dose-response meta-analysis found that cancer risk was not significantly elevated with the increased light exposure of night- shift work.

Conclusion: This systematic review of 57 observational studies did not find an overall association between ever-exposure to night-shift work and the risk of breast, prostate ovarian, pancreatic, colorectal, non-Hodgkin's lymph, and stomach cancers.

Night-shift work is increasingly frequent among both full-time and part-time workers worldwide. Night-shift workers have to face the biological challenges of work shifts, light at night and altered circadian rhythm cycles. These challenges, as well as alterations in daily life and activity may introduce potential harms to night workers. In different employment sectors today, the number of people working overtime or on a night shift has been increasing, especially in transportation, health care, and manufacturing (1). Surveys of Americans, Europeans and Australians have shown that 15–30% of adults were engaged in shift work experience, and more than 30% of them fell asleep at work at least once a week (2). Apart from an increased risk of work-related injury, night-shift workers have a greater chance of having long-term disorders. Currently, epidemiological evidences indicated that night-shift work is recognized to be associated with increased susceptibilities to cancer (3, 4).

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has defined that night-shift work is probably carcinogenic to humans (IARC Group 2A) (5). Further studies have proposed the followings as a potential mechanism of carcinogenicity of night-shift work as: (1) circadian rhythm disruption, (2) melatonin suppression due to exposure to light at night, (3) physiological changes, (4) lifestyle disturbances, and (5) decreased vitamin D levels (resulting from lack of sunlight) (6). However, studies focusing on the association between night-shift work and cancer risks have reached contradictory conclusions. Even though several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted, they presented inconsistent findings (7). Nine reviews reported that night work may be positively associated with breast cancer, skin cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer (2, 8–15), while four reviews reported slightly elevated but statistically insignificant results, among which the review published in 2017 included nine studies and 2,570,790 participants (2), the review in 2016 included ten studies and 4,660 breast cancer patients (16), the review in 2013 included 16 studies and 1,444,881 participants (17), and another review in 2013 included 15 studies and 1,422,189 participants (18).

In the last 2 years, nine original population-based studies reported that night-shift work was not associated with cancer development, which have not been included in previously published reviews (19–26). We conducted this study to systematically summarize the evidence regarding the associations between night-shift work and cancer risks. We expect to facilitate recognition of the health-related problems among night-shift workers.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Table S1). The study protocol was registered in the online database of PROSPERO (CRD42019138215). This systematic review aimed to answer the medical question of the association between night-shift work and cancer risks by reference to PICOS: (1) study population were night-shift workers; (2) compared to population without night-shift work; (3) the exposure was defined as night-shift work; (4) the outcome of cancer risk was evaluated; (5) observational studies on this topic were included.

We used Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science databases to systematically search English language publications issued up to May 31, 2019. The search terms were “carcinoma” or “tumor” or “cancer” or “neoplasm,” and “night-shift work” or “night work” or “shift work” or “work schedule tolerance” or “rotating-shift work.” The detailed literature search strategy was shown in Supplementary Box 1. Two investigators independently searched and then screened the retrieved studies. In addition, we manually screened the reference lists of included studies to collect additional literature.

Literature was included based the following criteria: (1) night-shift work was reported. Night-shift work was defined by questionnaire interview or occupational history of those who have ever exposed to shift system (rotating or fixed, forward or backward rotation). The durations that participants have ever engaged in night-shift work were collected by retrospective investigation or follow-up interview. (2) Cancer risk was investigated. (3) Cohort studies, case-control studies, or nested case-control studies. (4) The risk was estimated by odds ratio (OR), risk ratio (RR), or hazard ratio (HR), with 95% confidence interval (CI). (5) For studies reporting overlapping data, the studies newly published or with a larger sample size were included. (6) Publications in English language. Exclusion criteria were (1) studies without sufficient data; (2) studies referring to recurrent cancer.

We assessed the bias risk as low, high, or unclear by verifying the checklist for measuring bias in risk factor studies to counter 10 important sources (domains) of bias (17, 27). The following are domains of bias risk assessment: (1) exposure definition, (2) exposure assessments, (3) reliability of assessments, (4) analysis methods in research (research-specific bias), (5) confusion, (6) attrition, (7) blinding of assessors, (8) selective reporting, (9) funding, and (10) conflict of interest. We then rated the study-level risk of bias as: low (low risk in all major domains and ≥2 of the minor domains), moderate (low risk of bias in ≥4 major and 2 minor domains), or high risk of bias (low risk of bias in <4 major domains). The detailed information is available in Supplementary Box 2.

The following items were extracted from eligible studies: (1) first author; (2) publication year; (3) country of participants; (4) study design (cohort studies, case-control studies, or nested case-control studies); (5) number of participants (6) number of cases; (7) duration or person-years of follow-up (8) characteristics of participants (e.g., age, sex, and occupation); (9) years of night- shift work, (10) types of night-shift work; (11) adjusted effect estimates (i.e., OR, RR, and HR) with 95% CI; (12) types of cancers; (13) adjusted variables. Two investigators independently undertook data extraction, and the third author participated in handling debatable issues if necessary.

All statistical analyses were done with the Stata14.0 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). We preferentially measured the association between night-shift work and all cancer risks via the pooled estimates (i.e., OR, RR, and HR) and 95% CI. The Q test along with I2 statistic was used to identify whether heterogeneity was significant between eligible studies. When P < 0.10 or I2 > 50% heterogeneity was considered significant, therefore the random-effect model (Der Simonian-Laird method) meta-analysis was applied, otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used. In addition, subgroup analyses were conducted to stratify the results on specific study design, occupation, night-shift work status, cancer type, and sex. A dose-response meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the risk for cancers per year increase of night-shift work. We established the curve of dose-response relationship using a method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker (28). In this process, we combined the data from studies that reported the estimate effects of cancer risks with night-shift work at ≥3 quantitative categories. To assess the stability of the results, sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequential removal of each original study. Potential publication bias was assessed by the Begg's regression asymmetry test and funnel plot.

Details of the literature search and screening are shown in Figure 1. A total of 1660 publications were initially retrieved from Embase, PubMed and Web of Science. Among them, 538 duplicate publications were removed. After review of abstracts 1,037 studies were excluded for the following reasons: not human studies (n = 53), not studies on cancer and night-shift work (n = 713), reviews/editorials/letters (n = 271). By full-text review eight studies with overlapping data and 20 studies on sleep patterns were removed. Altogether, this meta-analysis included 57 articles.

As shown in Table 1, our study included 57 articles with 8,477,849 participants (mean age 55 years; 2,560,886 men, 4,220,154 women, and 1,696,809 sex not mentioned) (8, 16, 19–26, 29–75). Of these, 13 studies were from Asia, 26 were from Europe, 16 were from North America, and 2 were from Oceania. The geographic distribution of the studies included are shown in Figure 2. In terms of the participants' occupations, 11 studies were conducted among nurses, and two were among textile workers. These studies investigated the association between night-shift work and the risk of cancer in the breast (n = 26 studies), prostate (n = 12), ovaries (n = 8), pancreas (n = 6), colon/rectum (n = 6), lung (n = 6), stomach (n = 4), skin (n = 4), urinary tract (n = 3), esophagus (n = 3), uterus (n = 2), oral cavity (n = 2), larynx (n = 2), and testes (n = 2), as well as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (n = 5), and leukemia (n = 3).

The quality assessment of original studies showed that no study had an overall low risk of bias and 44 studies were of moderate risk [(4, 16, 19–21, 23–26, 29, 31, 32, 36, 37, 39–43, 46, 48–53, 57–60, 62, 63, 65–71, 73–75); Table S2]. Thirty-one studies were considered to have a low risk of bias in how they defined night-shift work (4, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 29, 32, 35–37, 41, 43, 46, 48, 50–53, 58–60, 63, 65, 67–72, 74). For method of exposure measurement, only eight studies showed low risk (20, 23, 36, 41, 57–59, 69). Thirty-one studies had a low risk of bias for reliability of exposure assessment (4, 16, 19–21, 23, 29–31, 33, 35, 37–39, 41, 45, 48, 51, 55, 57–61, 65, 66, 68–70, 73, 75). Forty studies had low risk of bias for the analysis domain (4, 16, 19, 20, 22, 23, 26, 29, 31, 35–37, 39–42, 44, 46–52, 55, 57, 59, 61–74), and 49 reported a low risk in adjustment for confounding factors (4, 16, 20, 21, 23–26, 29, 32, 35–43, 45–55, 57–75). For the aspect of attrition domain, 27 studies had low risk in bias (4, 19, 23–26, 31–33, 37, 40–43, 46, 48, 50, 52, 56–58, 60, 61, 65, 66, 72, 74, 75). Nineteen studies were considered a low risk of bias for blinding (19, 29, 31, 32, 34, 37–40, 42, 43, 47, 49, 50, 58, 62, 63, 69, 70, 75). Fifty-two studies had a low risk in the aspect of selective reporting (4, 16, 19–24, 26, 29–45, 48–54, 56–75). Forty-six studies reported that sponsors had no role in conduct (4, 16, 19–26, 26, 29, 31–36, 39–41, 43, 45–49, 51–63, 65–75) and authors from 51 articles confirmed no conflict of interest (4, 16, 19–26, 29, 31–75).

As shown in Table 2, the risks of breast cancer (pooled OR = 1.009, 95% CI = 0.984–1.033), prostate cancer (pooled OR = 1.027, 95% CI = 0.982–1.071), ovarian cancer (pooled OR = 1.027, 95% CI = 0.942–1.113), pancreatic cancer (pooled OR = 1.007, 95% CI = 0.910–1.104), colorectal cancer (pooled OR = 1.016, 95% CI = 0.964–1.068) were not significantly associated with night-shift work. Besides, the pooled results, which were from small number of original studies, showed that stomach cancer, esophageal cancer, leukemia, oral cancer, uterine cancer, laryngeal cancer, testicular cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma were not associated with night-shift work. Combination of three original studies showed that night-shift work increased the risk of urinary cancer. However, decreased risks of lung cancer and skin cancer were observed on the basis of pooled results of six and four studies, respectively.

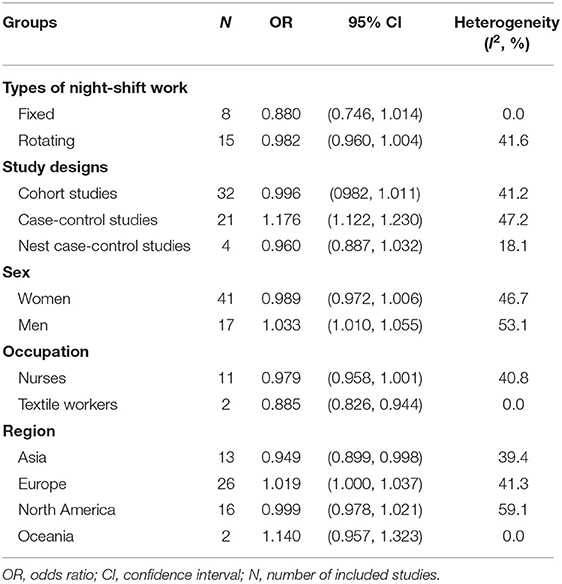

As subgroup analyses on the association between night-shift work and combined risk for cancers (Table 3), no significant associations were observed in cohort studies (pooled OR = 0.996, 95% CI = 0.982–1.011) and nest case-control studies (pooled OR = 0.960, 95% CI = 0.887–1.032). However, the pooled result from case-control studies was statistically significant (pooled OR = 1.176, 95% CI =1.122–1.230). With regard to sex, night-shift work was only associated with increased risk of cancer among men (pooled OR = 1.033, 95% CI = 1.010–1.055).

Table 3. Subgroup meta-analyses on the associations between night-shift work and combined risk for cancers.

For types of night-shift work, neither rotating nor fixed night-shift work was associated with an increased risk of cancer, with pooled ORs 0.982 (95% CI = 0.960–1.004), and 0.880 (95% CI = 0.746–1.014), respectively. The association between night-shift work and cancer risks were also analyzed among occupational groups. Night-shift work was associated with a decreased risk of cancers among textile workers, while no significant association was found for nurses.

We included 13 original studies from Asia, 26 from Europe, 16 from North America, and 2 from Oceania. Subgroup analyses indicated that night-shift work was associated with an increased risk for cancers in Europe, and a decreased risk in Asia, while no significant associations were observed in America or Oceania.

For studies that reported more than one category of durations of night-shift work, we assessed whether the risk of cancer increased in a dose-response manner per year night-shift work. As shown in Figure 3, a dose-response curve was established, in which the solid line is a curve model established by the dose response meta-analysis, while the dotted line represents a reference of linear model. The result indicated that, for every 1 year increase of night-shift work, there is no increased risk for cancer (χ2 = 3.34, P = 0.067).

In addition, we validated this finding with comparisons of cancer risks among individuals with different classifications of night work duration (0–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, 21–25, and ≥26 years). Taking all eligible studies together, night-shift work did not increase the risk of cancer in any group of night workers (Figure 4 and Table S3).

The Q-test and I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity across included studies. No obvious heterogeneity was observed in the overall analyses, while heterogeneity was found in four subgroup analyses (i.e., men, North America area, prostate cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer).

We performed the sensitivity analysis by omitting one study at a time, and recalculated the pooled OR of the remaining studies. As shown in Figure S1, no significant alteration was observed by removal of any single study except when the study of Poole et al. was removed (pooled OR = 1.020, 95% CI = 1.000–1.050) (40).

The Begg's test and funnel plot analysis (Figure 5) revealed a significant publication bias (z = 3.45, P = 0.001). Complete details in the underlying case-control studies that manifested insignificant associations might not have been fully published. In order to eliminate the fallacy introduced by publication bias, we performed a trim and fill analysis, in which the negative insignificant studies were filled (Figure S2). The filled results showed that night-shift work was not associated with breast cancer (Filled OR = 1.018, 95% CI = 0.965–1.074), prostate cancer (Filled OR = 1.066, 95% CI = 0.906–1.254); pancreatic cancer (Filled OR = 1.051, 95% CI = 0.919–1.203), ovarian cancer (Filled OR = 1.050, 95% CI = 0.948–1.164), lung cancer (Filled OR = 0.957, 95% CI = 0.861–1.065), or colorectal cancer (Filled OR = 1.091, 95% CI = 0.976–1.220). Meanwhile, the trim and fill analysis showed a significant association between night-shift work and skin cancer (Filled OR = 0.928, 95% CI = 0.875–0.985). In addition, trim and fill analysis showed insignificant results in Asians (Filled OR = 1.002, 95% CI = 0.906–1.108) and Americans (Filled OR = 1.016, 95% CI = 0.961–1.075), and a significant result among Europeans (Filled OR = 1.058, 95% CI = 1.011–1.106).

This updated systematic review included 57 publications with 8,477,849 participants. Our meta-analysis found an insignificant association between night-shift work and cancer risks. No increased risk for cancer was identified among female night-shift workers as well. Neither rotating night-shift workers nor fixed night-shift workers had an increased risk for cancer. However, analysis on geographical distribution showed an increased risk for cancer among night-shift workers in Europe.

As a common concern in case-control studies, recall bias might have been introduced into our study during the measurement of night work. This bias represents a major threat to the validity when the participants were investigated with self-reported questionnaires. In order to eliminate potential recall bias resulting from previous case-control studies on the association between night-shift work and cancer risks, we synthesized the data from cohort studies in which recall bias can be effectively controlled. Consequently, an insignificant association was noted again.

Researchers have proposed several underlying mechanism of cancer risks induced by night-shift work. Night-shift workers usually experience unnatural light at night, which reduces the release of melatonin (76). As a kind of methoxy indole compound secreted by the pineal gland, melatonin shows a variety of anti-tumor effects, such as anti-oxidant, anti-apoptosis, anti-angiogenesis, as well as modulation of hormones and immunity (77, 78). It has been demonstrated that melatonin plays critical roles in breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, lung, and gastrointestinal cancers (79–86). Decreased melatonin leads to an imbalance of inflammatory cytokine secretions, mutagenesis, and oxidative damage, which likely results in the progression of various cancers (87). Suppression of melatonin also induces the aberrant secretion of testosterone and estrogen which increases the risks of prostate, endometrial, ovarian, uterine, and breast cancers (88).

In addition, tumor suppression is a clock-controlled process. Night-shift workers are exposed to dysfunction of circadian genes that is understood to play a role in DNA repair and carcinogen metabolism (89–91). The disruption of the circadian time organization contributes to cancer development. The “clock” genes are known to be directly involved in the regulation of prostate tumorigenesis.

The intensity and duration, as well as the type of night-shift work may influence the effect on cancer risk. As other published systematic reviews, our study included all eligible studies on night-shift work (i.e., fixed and rotating night-shift work) in retrospective and prospective studies. Our subgroup analyses showed that neither fixed nor rotating night-shift work is associated with cancer risk. In addition, night-shift work has little association with cancer risk in spite of the variation of night work duration.

Surprisingly, our subgroup analysis demonstrated that night-shift work is associated with a reduction of cancer risk in Asians. It has been explained that Asian workers have different lifestyles and genotypes compared with Europeans and Americans (2). This finding, as well as the negative association between night-shift work and lung and skin cancers might result from publication bias or relatively small number of included studies.

The present study has more strengths than previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the same topic. As a newly released update, this study included many more eligible articles, among them nine studies were that were included in a meta-analysis for the first time. The larger populations enrolled in these studies could produce more accurate effect size at a higher statistical power. Furthermore, our study was conducted on the basis of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We rigorously included original data on night-shift work and excluded ineligible studies included in previous meta-analyses. These studies were conducted on work classifications, duration of sleep, sleep disturbance, and light at night. We checked all the database of original studies on night-shift work, and removed three studies on colorectal cancer (58, 92, 93), one study on lung cancer (94), one study on ovarian cancer (40), and five studies on breast cancer (3, 58, 95–97) because these studies reported overlapping data from the Nurses' Health Study (NHS) and/or NHS2. As a preferred solution, the newly published studies were included in our meta-analysis (20, 58).

Our study has some limitations which might sometimes exist in common systematic reviews. First, even though we searched three most commonly used databases, there is potential studies that were missed, especially published in local languages. A slightly different search by a reviewer can lead to very different initial results, which should also cause some caution. Second, we observed moderate heterogeneity in the subgroup analyses of the cohort study group, case-control study group, women, European region, Asian region, breast cancer, lung cancer, and endocrine cancers. The data from case-control studies might be biased by different methods of night-shift work measurement. Third, due to the lack of information on occupations of participants and measurement of night-shift work, these variables were not taken into account in the adjustment model. Moreover, publication bias was statistically positive, which could hinder the quality of this study. We use a trim and fill approach, and no substantial differences were obtained. Our combination of the results on all type of cancers may lead to the neglect of cancer-specific differences. As is known, cancers with stronger hormone components appear to be substantially different from those with less hormone control. In addition, we reported the results for ever vs. never night-shift work. There are many other indicators in night-shift work studies that track exposure in a more variable way. It is possible that the use of more differentiated exposure metrics, such as frequency or intensity of night-shift work, might lead to other results.

In conclusion, this systematic review of 57 observational studies did not find an overall association between ever-exposure to night-shift work and the risk of breast, prostate ovarian, pancreatic, colorectal, non-Hodgkin's lymph, and stomach cancers. With regard to sex, night-shift work was only associated with increased risk of cancer among men.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, https://www.embase.com/, and http://isiknowledge.com.

HH and YW designed this study. AD, XZ, and XG contributed to literature search, review, and data extraction. XZ and TW conduced statistical analyses. XZ, XJ, and HH contributed to manuscript drafting. AD and YW contributed to manuscript revision. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript.

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2017MH100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773527), Academic Promotion Program of Shandong First Medical University (Nos. 2019QL017 and 2019RC010), and Shandong Province Higher Educational Young and Innovation Technology Supporting Program (No. 2019KJL004).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.01006/full#supplementary-material

1. Aisbett B, Condo D, Zacharewicz E, Lamon S. The impact of shiftwork on skeletal muscle health. Nutrients. (2017) 9:248. doi: 10.3390/nu9030248

2. Du HB, Bin KY, Liu WH, Yang FS. Shift work, night work, and the risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis based on 9 cohort studies. Medicine. (2017) 96:e8537. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008537

3. Schernhammer ES, Kroenke CH, Laden F, Hankinson SE. Night work and risk of breast cancer. Epidemiology. (2006) 17:108–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000190539.03500.c1

4. Viswanathan AN, Hankinson SE, Schernhammer ES. Night shift work and the risk of endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. (2007) 67:10618–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2485

5. Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. (2007) 8:1065–6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70373-X

6. Van Dycke KC, Rodenburg W, van Oostrom CT, van Kerkhof LW, Pennings JL, Roenneberg T, et al. Chronically alternating light cycles increase breast cancer risk in Mice. Curr Biol. (2015) 25:1932–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.012

7. Pahwa M, Labreche F, Demers PA. Night shift work and breast cancer risk: what do the meta-analyses tell us? Scand J Work Environ Health. (2018) 44:432–5. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3738

8. Lin X, Chen W, Wei F, Ying M, Wei W, Xie X. Night-shift work increases morbidity of breast cancer and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies. Sleep Med. (2015) 16:1381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.543

9. Megdal SP, Kroenke CH, Laden F, Pukkala E, Schernhammer ES. Night work and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. (2005) 41:2023–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.010

10. Rao D, Yu H, Bai Y, Zheng X, Xie L. Does night-shift work increase the risk of prostate cancer? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. (2015) 8:2817–26. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S89769

11. Liu W, Zhou Z, Dong D, Sun L, Zhang G. Sex differences in the association between night shift work and the risk of cancers: a meta-analysis of 57 articles. Dis Markers. (2018) 2018:7925219. doi: 10.1155/2018/7925219

12. Yuan X, Zhu C, Wang M, Mo F, Du W, Ma X. Retraction: night shift work increases the risks of multiple primary cancers in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 articles. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2019) 28:423. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-1085

13. Wang X, Ji A, Zhu Y, Liang Z, Wu J, Li SQ, et al. A meta-analysis including dose-response relationship between night shift work and the risk of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:25046–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4502

14. Wang F, Yeung KL, Chan WC, Kwok CCH, Leung SL, Wu C, et al. A meta- analysis on dose-response relationship between night shift work and the risk of breast cancer. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24:2724–32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt283

15. Gan Y, Li LQ, Zhang LW, Yan SJ, Gao C, Hu S, et al. Association between shift work and risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Carcinogenesis. (2018) 39:87–97. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx129

16. Travis RC, Balkwill A, Fensom GK, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Wang XS, et al. Night shift work and breast cancer incidence: three prospective studies and meta-analysis of published studies. JNCI J Natl Cancer I. (2016) 108:djw169. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw169

17. Ijaz S, Verbeek J, Seidler A, Lindbohm ML, Ojajarvi A, Orsini N, et al. Night-shift work and breast cancer–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2013) 39:431–47. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3371

18. Kamdar BB, Tergas AI, Mateen FJ, Bhayani NH, Oh J. Night-shift work and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2013) 138:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2433-1

19. Leung L, Grundy A, Siemiatycki J, Arseneau J, Gilbert L, Gotlieb WH, et al. Shift work patterns, chronotype, and epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2019) 28:987–95. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-1112

20. Papantoniou K, Devore EE, Massa J, Strohmaier S, Vetter C, Yang L, et al. Rotating night shift work and colorectal cancer risk in the nurses' health studies. Int J Cancer. (2018) 143:2709–17. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31655

21. Wendeu-Foyet MG, Bayon V, Cenee S, Tretarre B, Rebillard X, Cancel-Tassin G, et al. Night work and prostate cancer risk: results from the EPICAP Study. Occup Environ Med. (2018) 75:573–81. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-105009

22. Walasa WM, Carey RN, Si S, Fritschi L, Heyworth JS, Fernandez RC, et al. Association between shiftwork and the risk of colorectal cancer in females: a population-based case-control study. Occup Environ Med. (2018) 75:344–50. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104657

23. Vistisen HT, Garde AH, Frydenberg M, Christiansen P, Hansen AM, Andersen J, et al. Short-term effects of night shift work on breast cancer risk: a cohort study of payroll data. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2017) 43:59–67. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3603

24. Åkerstedt T, Narusyte J, Svedberg P, Kecklund G, Alexanderson K. Night work and prostate cancer in men: a Swedish prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e015751. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015751

25. Behrens T, Rabstein S, Wichert K, Erbel R, Eisele L, Arendt M, et al. Shift work and the incidence of prostate cancer: a 10-year follow-up of a German population-based cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2017) 43:560–8. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3666

26. Lie J, Kjuus H, Zienolddiny S, Haugen A, Stevens R, Kjærheim K. Night work and breast cancer risk among Norwegian nurses: assessment by different exposure metrics. Am J Epidemiol. (2011) 173:1272–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr014

27. Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Ansari MT, Raman G, Berkman ND, Grant M, et al. Development quality criteria to evaluate nontherapeutic studies of incidence, prevalence, or risk factors of chronic diseases: pilot study of new checklists. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:637–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.006

28. Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. (1992) 135:1301–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237

29. Hansen J, Lassen CF. Nested case-control study of night shift work and breast cancer risk among women in the Danish military. Occup Environ Med. (2012) 69:551–6. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100240

30. Davis S, Mirick DK, Steve RG. Night shift work, light at night, and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2001) 93:1557–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.20.1557

31. Lie J-AS, Roessink J, Kjærheim K. Breast cancer and night work among Norwegian nurses. Cancer Causes Control. (2006) 17:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-3639-2

32. Kubo T, Ozasa K, Mikami K, Wakai K, Fujino Y, Watanabe Y, et al. Prospective cohort study of the risk of prostate cancer among rotating-shift workers: findings from the Japan collaborative cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. (2006) 164:549–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj232

33. O'Leary ES, Schoenfeld ER, Stevens RG, Kabat GC, Henderson K, Grimson R, et al. Shift work, light at night, and breast cancer on Long Island, New York. Am J Epidemiol. (2006) 164:358–66. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj211

34. Schwartzbaum J, Ahlbom A, Feychting M. Cohort study of cancer risk among male and female shift workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2007) 33:336–43. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1150

35. Marino JL, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Rossing MA. Night shift work and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. (2008) 167:S9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn138

36. Lahti TA, Partonen T, Kyyronen P, Kauppinen T, Pukkala E. Night-time work predisposes to non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. (2008) 123:2148–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23566

37. Pronk A, Ji BT, Shu XO, Xue S, Yang G, Li HL, et al. Night-shift work and breast cancer risk in a cohort of Chinese women. Am J Epidemiol. (2010) 171:953–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq029

38. Chu CH, Chen CJ, Hsu GC, Liu IL, Christiani DC, Ku CH. Shift work is risk factor for breast cancer among Taiwanese women. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. (2010) 8:209. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6349(10)70531-0

39. Pesch B, Harth V, Rabstein S, Baisch C, Schiffermann M, Pallapies D, et al. Night work and breast cancer - results from the German GENICA study. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2010) 36:134–41. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2890

40. Poole EM, Schernhammer ES, Tworoger SS. Rotating night shift work and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2011) 20:934–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0138

41. Kubo T, Oyama I, Nakamura T, Kunimoto M, Kadowaki K, Otomo H, et al. Industry-based retrospective cohort study of the risk of prostate cancer among rotating-shift workers. Int J Urol. (2011) 18:206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02714.x

42. Parent ME, El-Zein M, Rousseau MC, Pintos J, Siemiatycki J. Night work and the risk of cancer among men. Am J Epidemiol. (2012) 176:751–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws318

43. Natti J, Anttila T, Oinas T, Mustosmaki A. Night work and mortality: prospective study among Finnish employees over the time span 1984 to 2008. Chronobiol Int. (2012) 29:601–9. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.675262

44. Lin Y, Ueda J, Yagyu K, Kurosawa M, Tamakoshi A, Kikuchi S. A prospective cohort study of shift work and the risk of death from pancreatic cancer in Japanese men. Cancer Causes Control. (2013) 24:1357–61. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0214-0

45. Knutsson A, Alfredsson L, Karlsson B, Akerstedt T, Fransson EI, Westerholm P, et al. Breast cancer among shift workers: results of the WOLF longitudinal cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2013) 39:170–7. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3323

46. Bhatti P, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Doherty JA, Rossing MA. Nightshift work and risk of ovarian cancer. Occup Environ Med. (2013) 70:231–7. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101146

47. Fritschi L, Erren TC, Glass DC, Girschik J, Thomson AK, Saunders C, et al. The association between different night shiftwork factors and breast cancer: a case-control study. Br J Cancer. (2013) 109:2472–80. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.544

48. Menegaux F, Truong T, Anger A, Cordina-Duverger E, Lamkarkach F, Arveux P, et al. Night work and breast cancer: a population-based case-control study in France (the CECILE study). Int J Cancer. (2013) 132:924–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27669

49. Grundy A, Richardson H, Burstyn I, Lohrisch C, SenGupta SK, Lai AS, et al. Increased risk of breast cancer associated with long-term shift work in Canada. Occup Environ Med. (2013) 70:831–8. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101482

50. Rabstein S, Harth V, Pesch B, Pallapies D, Lotz A, Justenhoven C, et al. Night work and breast cancer estrogen receptor status–results from the German GENICA study. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2013) 39:448–55. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3360

51. Koppes LL, Geuskens GA, Pronk A, Vermeulen RC, de Vroome EM. Night work and breast cancer risk in a general population prospective cohort study in the Netherlands. Eur J Epidemiol. (2014) 29:577–84. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9938-8

52. Gapstur SM, Diver WR, Stevens VL, Carter BD, Teras LR, Jacobs EJ. Work schedule, sleep duration, insomnia, and risk of fatal prostate cancer. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 46:S26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.033

53. Carter BD, Diver WR, Hildebrand JS, Patel AV, Gapstur SM. Circadian disruption and fatal ovarian cancer. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 46:S34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.032

54. Yong M, Blettner M, Emrich K, Nasterlack M, Oberlinner C, Hammer GP. A retrospective cohort study of shift work and risk of incident cancer among German male chemical workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2014) 40:502–10. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3438

55. Ren Z. Association of sleep duration, daytime napping, and night shift work with breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:2181. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2014-2181

56. Datta K, Roy A, Nanda D, Das I, Guha S, Ghosh D, et al. Association of breast cancer with sleep pattern - a pilot case control study in a regional cancer centre in South Asia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2014) 15:8641–5. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.20.8641

57. Kwon P, Lundin J, Li W, Ray R, Littell C, Gao D, et al. Night shift work and lung cancer risk among female textile workers in Shanghai, China. J Occup Environ Hyg. (2015) 12:334–41. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2014.993472

58. Gu F, Han J, Laden F, Pan A, Caporaso NE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Total and cause-specific mortality of US nurses working rotating night shifts. Am J Prev Med. (2015) 48:241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.018

59. Hammer GP, Emrich K, Nasterlack M, Blettner M, Yong M. Shift work and prostate cancer incidence in industrial workers: a historical cohort study in a German Chemical Company. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2015) 112:463–70. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0463

60. Lin Y, Nishiyama T, Kurosawa M, Tamakoshi A, Kubo T, Fujino Y, et al. Association between shift work and the risk of death from biliary tract cancer in Japanese men. BMC Cancer. (2015) 15:757. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1722-y

61. Akerstedt T, Knutsson A, Narusyte J, Svedberg P, Kecklund G, Alexanderson K. Night work and breast cancer in women: a Swedish cohort study. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008127. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008127

62. Li W, Ray RM, Thomas DB, Davis S, Yost M, Breslow N, et al. Shift work and breast cancer among women textile workers in Shanghai, China. Cancer Causes Control. (2015) 26:143–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0493-0

63. Papantoniou K, Castano-Vinyals G, Espinosa A, Aragones N, Perez-Gomez B, Ardanaz E, et al. Breast cancer risk and night shift work in a case-control study in a Spanish population. Eur J Epidemiol. (2016) 31:867–78. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0073-y

64. Santi SA, Meigs ML, Zhao Y, Bewick MA, Lafrenie RM, Conlon MS. A case-control study of breast cancer risk in nurses from Northeastern Ontario, Canada. Cancer Causes Control. (2015) 26:1421–8. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0633-1

65. Wang P, Ren FM, Lin Y, Su FX, Jia WH, Su XF, et al. Night-shift work, sleep duration, daytime napping, and breast cancer risk. Sleep Med. (2015) 16:462–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.11.017

66. Heckman CJ, Kloss JD, Feskanich D, Culnan E, Schernhammer ES. Associations among rotating night shift work, sleep and skin cancer in Nurses' Health Study II participants. Occup Environ Med. (2017) 74:169–75. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-103783

67. Dickerman BA, Markt SC, Koskenvuo M, Hublin C, Pukkala E, Mucci LA, et al. Sleep disruption, chronotype, shift work, and prostate cancer risk and mortality: a 30-year prospective cohort study of Finnish twins. Cancer Causes Control. (2016) 27:1361–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0815-5

68. Gyarmati G, Turner MC, Castano-Vinyals G, Espinosa A, Papantoniou K, Alguacil J, et al. Night shift work and stomach cancer risk in the MCC-Spain study. Occup Environ Med. (2016) 73:520–7. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-103597

69. Bai Y, Li X, Wang K, Chen S, Wang S, Chen Z, et al. Association of shift-work, daytime napping, and nighttime sleep with cancer incidence and cancer-caused mortality in Dongfeng-Tongji cohort study. Ann Med. (2016) 48:641–51. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2016.1217037

70. Costas L, Benavente Y, Olmedo-Requena R, Casabonne D, Robles C, Gonzalez-Barca EM, et al. Night shift work and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the MCC-Spain case-control study. Int J Cancer. (2016) 139:1994–2000. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30272

71. Wegrzyn LR, Tamimi RM, Rosner BA, Brown SB, Stevens RG, Eliassen AH, et al. Rotating night-shift work and the risk of breast cancer in the nurses' health studies. Am J Epidemiol. (2017) 186:532–40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx140

72. Jorgensen JT, Karlsen S, Stayner L, Andersen J, Andersen ZJ. Shift work and overall and cause-specific mortality in the Danish nurse cohort. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2017) 43:117–26. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3612

73. Tse LA, Lee PMY, Ho WM, Lam AT, Lee MK, Ng SSM, et al. Bisphenol A and other environmental risk factors for prostate cancer in Hong Kong. Environ Int. (2017) 107:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.06.012

74. Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, McFadden EC, Wright LB, Johns LE, Swerdlow AJ. Night shift work and risk of breast cancer in women: the Generations Study cohort. Br J Cancer. (2019) 121:172–9. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0485-7

75. Hansen J. Increased breast cancer risk among women who work predominantly at night. Epidemiology. (2001) 12:74–7. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200101000-00013

76. Zhao M, Wan JY, Zeng K, Tong M, Lee AC, Ding JX, et al. The reduction in circulating melatonin level may contribute to the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: a retrospective study. J Cancer. (2016) 7:831–6. doi: 10.7150/jca.14573

77. Claustrat B, Leston J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie. (2015) 61:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.03.002

78. Meng X, Li Y, Li S, Zhou Y, Gan RY, Xu DP, et al. Dietary sources and bioactivities of melatonin. Nutrients. (2017) 9:367. doi: 10.3390/nu9040367

79. Rodriguez-Garcia A, Mayo JC, Hevia D, Quiros-Gonzalez I, Navarro M, Sainz RM. Phenotypic changes caused by melatonin increased sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to cytokine-induced apoptosis. J Pineal Res. (2013) 54:33–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01017.x

80. Zare H, Shafabakhsh R, Reiter RJ, Asemi Z. Melatonin is a potential inhibitor of ovarian cancer: molecular aspects. J Ovarian Res. (2019) 12:26. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0502-8

81. Viswanathan AN, Schernhammer ES. Circulating melatonin and the risk of breast and endometrial cancer in women. Cancer Lett. (2009) 281:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.002

82. Lissoni P, Chilelli M, Villa S, Cerizza L, Tancini G. Five years survival in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy and melatonin: a randomized trial. J Pineal Res. (2003) 35:12–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2003.00032.x

83. Ma ZQ, Yang Y, Fan CX, Han J, Wang DJ, Di SY, et al. Melatonin as a potential anticarcinogen for non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:46768–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8776

84. Davis S, Mirick DK, Chen C, Stanczyk FZ. Night shift work and hormone levels in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2012) 21:609–18. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1128

85. Zhang SM, Zuo L, Gui SY, Zhou Q, Wei W, Wang Y. Induction of cell differentiation and promotion of endocan gene expression in stomach cancer by melatonin. Mol Biol Rep. (2012) 39:2843–9. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1043-4

86. Lee JH, Yun CW, Han YS, Kim S, Jeong D, Kwon HY, et al. Melatonin and 5-fluorouracil co-suppress colon cancer stem cells by regulating cellular prion protein-Oct4 axis. J Pineal Res. (2018) 65:e12519. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12519

88. Mancio J, Leal C, Ferreira M, Norton P, Lunet N. Does the association of prostate cancer with night-shift work differ according to rotating vs. fixed schedule? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. (2018) 21:337–44. doi: 10.1038/s41391-018-0040-2

89. Monsees GM, Kraft P, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Schernhammer ES. Circadian genes and breast cancer susceptibility in rotating shift workers. Int J Cancer. (2012) 131:2547–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27564

90. Zienolddiny S, Haugen A, Lie JA, Kjuus H, Anmarkrud KH, Kjaerheim K. Analysis of polymorphisms in the circadian-related genes and breast cancer risk in Norwegian nurses working night shifts. Breast Cancer Res. (2013) 15:R53. doi: 10.1186/bcr3445

91. Zmrzljak UP, Rozman D. Circadian regulation of the hepatic endobiotic and xenobitoic detoxification pathways: the time matters. Chem Res Toxicol. (2012) 25:811–24. doi: 10.1021/tx200538r

92. Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Kawachi I, et al. Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the nurses' health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2003) 95:825–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.11.825

93. Devore EE, Massa J, Papantoniou K, Schernhammer ES, Wu K, Zhang X, et al. Rotating night shift work, sleep, and colorectal adenoma in women. Int J Colorectal Dis. (2017) 32:1013–8. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2758-z

94. Schernhammer ES, Feskanich D, Liang GY, Han JL. Rotating night-shift work and lung cancer risk among female nurses in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. (2013) 178:1434–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt155

95. Lie JAS, Kjuus H, Zienolddiny S, Haugen A, Kjaerheim K. Breast cancer among nurses: is the intensity of night work related to hormone receptor status? Am J Epidemiol. (2013) 178:110–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws428

96. Truong T, Liquet B, Menegaux F, Plancoulaine S, Laurent-Puig P, Mulot C, et al. Breast cancer risk, nightwork, and circadian clock gene polymorphisms. Endocr Relat Cancer. (2014) 21:629–38. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0121

Keywords: night-shift work, carcinogenicity, meta-analysis, risk factor, odds ratio

Citation: Dun A, Zhao X, Jin X, Wei T, Gao X, Wang Y and Hou H (2020) Association Between Night-Shift Work and Cancer Risk: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 10:1006. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01006

Received: 06 December 2019; Accepted: 21 May 2020;

Published: 23 June 2020.

Edited by:

Hajo Zeeb, Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology (LG), GermanyReviewed by:

Manisha Pahwa, Occupational Cancer Research Centre (OCRC), CanadaCopyright © 2020 Dun, Zhao, Jin, Wei, Gao, Wang and Hou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youxin Wang, d2FuZ3lAY2NtdS5lZHUuY24=; Haifeng Hou, aGZob3VAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.