- 1Department of Radiation Oncology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

- 2Radiation Biology Department, National Center for Radiation Research and Technology, Cairo, Egypt

- 3Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

Calorie restriction (CR) is considered one of the most robust ways to extend life span and reduce the risk of age-related diseases, including cancer, as shown in many different organisms, whereas opposite effects have been associated with high fat diets (HFDs). Despite the proven contribution of sirtuins in mediating the effects of CR in longevity, the involvement of these nutrient sensors, specifically, in the diet-induced effects on tumorigenesis has yet to be elucidated. Previous studies focusing on SIRT1, do not support a critical role for this sirtuin family member in CR-mediated cancer prevention. However, the contribution of other family members which exhibit strong deacetylase activity is unexplored. To fill this gap, we aimed at investigating the role of SIRT2 and SIRT3 in mediating the anti and pro-tumorigenic effect of CR and HFD, respectively. Our results provide strong evidence supporting distinct, context-dependent roles played by these two family members. SIRT2 is indispensable for the protective effect of CR against tumorigenesis. On the contrary, SIRT3 exhibited oncogenic properties in the context of HFD-induced tumorigenesis, suggesting that SIRT3 inhibition may mitigate the cancer-promoting effects of HFD. Given the different functions regulated by SIRT2 and SIRT3, unraveling downstream targets/pathways involved may provide opportunities to develop new strategies for cancer prevention.

Introduction

Calorie restriction (CR); 20-40% reduction of daily calorie intake without malnutrition, is the most studied and reproducible non-genetic intervention known to extend lifespan in different species (1–8). In addition to positively affecting longevity, CR improves also healthspan as evidenced by the reduced risk for a variety of age-associated diseases, including diabetes, sarcopenia, cardiovascular diseases, and hearing loss in both rodents and humans (9). The opposite effect is exerted by obesity and high-fat diets. In this regard, the high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mouse has been well-established as a model for impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and type 2 diabetes (10). In a similar way, obesity in humans is linked with increased mortality due to several pathologies and major reductions in life expectancy compared with normal weight (11).

Given that cancer is considered an age-related disease (12), any interventions shown to improve healthspan could be exploited to either prevent or slow down tumorigenesis. Indeed, CR delays tumorigenesis in a p53-knockout mouse model (13) and recent studies show a significant reduction in the incidence of cancers in rhesus monkeys fed a CR diet compared to a control diet (14). Accordingly, a recent meta-analysis showed that 40 of the 44 pre-clenical studies (90.9%) support the anticancer role of CR despite the different measurements (15). On the contrary, HFD-induced obesity was found to shorten life expectancy through mediating various diseases, including cancer (16–18). While the anti and pro-tumorigenic effects of CR and HFD, respectively, are well-established, the underlying mechanisms remain obscure.

Considering that sirtuins mediate the CR-induced anti-aging effects (19, 20) through their function as NAD-dependent protein deacetylases directly activated by CR, it could be proposed that they may contribute to the tumor suppressive effects of CR. Despite extensive research regarding the broader role of sirtuins in cancer (21), this is a relatively unexplored area. Therefore, it is rather surprising that there is a lack of experimental data to assess the involvement of sirtuins, specifically, in the CR-induced effect on tumorigenesis. Among the different family members, SIRT1, is the only sirtuin studied so far in this context. More specifically, its overexpression failed to influence the anticancer effects of every-other-day fasting-a variation of CR–(22). Although these result suggest that SIRT1 may play a limited role in the effects of CR on cancer, the possible involvement of other sirtuins in the diet-induced effects on tumorigenesis has yet to be elucidated.

SIRT2 and SIRT3 exhibit the strongest deacetylation activity compared to other family members (23) and have been shown to regulate the acetylome (24, 25). Here, we investigated the role of these two family members in mediating the anti and pro-tumorigenic effect of CR and HFD, respectively. Toward this direction, heterozygous(+/−) and homozygous(−/−) p53 deleted C57BL/6 mice were crossed with either Sirt2−/− or Sirt3−/− mice to generate mice with 6 different genotypes: p53+/−, Sirt2−/−; p53+/−, Sirt3−/−; p53+/−, p53−/−, Sirt2−/−; p53−/−, and Sirt3−/−; p53−/−. Each of the 6 genotypes was subjected to 3 dietary regimes; ad libitum control diet, 30% CR diet, and ad libitum HFD, starting at about 7-8 weeks after birth followed by survival and tumor incidence analysis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

p53 knockout mice [Stock No. 002101, The Jackson Laboratory, (26)] were kindly provided by Elizabeth Eklund (Northwestern University). Sirt2−/− and Sirt3−/− mice have been generated and described previously (27, 28). Hemizygous (+/-) and nullizygous (-/-) p53 mice were crossed with either Sirt2−/− or Sirt3−/− mice to generate mice with 6 different genotypes: p53+/−, Sirt2−/−; p53+/−, Sirt3−/−; p53+/−, p53−/−, Sirt2−/−; p53−/−, and Sirt3−/−; p53−/−. Mice were housed and treated in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Genotyping

Mouse genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies using the REDExtract-N-Amp™ Tissue PCR Kit following the standard protocol. PCR was performed using the primer pairs and conditions as described below:

For p53

Forward wild-type 5′-AGGCTTAGAGGTGCAAGCTG-3′,

Forward mutant 5′-CAGCCTCTGTTCCACATACACT-3′,

Reverse (common) 5′-TGGATGGTGGTATACTCAGAGC-3′

32 cycles at 93°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 65°C for 2 min.

For SIRT2

Forward wild-type 5′-CAGGGTCTCACGAGTCTCATG-3′,

Forward mutant 5′-GACTGGAAGTGATCAAAGCTC-3′,

Reverse (common) 5′-TCAAATCTGGCCAGAACTTATG-3′

35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s.

For SIRT3

Forward (common) 5′-GGGAGCACTCTCATACTCTA-3′,

Reverse wild-type 5′-TTACTGCTGCCTAACGTTCC-3′

Reverse mutant 5′-CCCTCAATCACAAATGTCGG-3′,

32 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s.

Diets

Each of the 6 genotypes (n = 9–12) was subjected to 3 dietary regimes; ad libitum control diet (3.85 kcal/g, D12450Ji), 30% calorie restriction diet (D15032801Bi), and ad libitum high-fat diet (5.24 kcal/g with 60% kcal from fat, D12492Ri), starting at about 7-8 weeks after birth. Diets were purchased from Research Diet Inc. (Brunswick, NJ, USA), and were designed to provide variations in calories while maintaining similar micronutrient composition. Heterozygous p53 knockout mice were subjected to two cycles of either CR or HFD-14 weeks each, intercepted by 21 weeks of exposure to control diet pellets. Homozygous p53 knockout mice displayed shorter lifespan (~60% shorter than p53 heterozygous knockout mice), and were subjected to one 14 weeks long cycle of either CR or HFD.

Body Weight, Tumor Incidence, and Survival

Diets were administered by members of the Center for Comparative Medicine (CCM) at Northwestern University. Body weights and health condition of the mice were closely monitored and reports were provided to the lab members. All data were analyzed by lab members. Tumors and tissues were collected at the end of the experiments.

Western Blotting

Tissues were homogenized in cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40), with freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The following antibodies were used: SIRT2 (Proteintech, #19655-1-AP), SIRT3 (Cell Signaling, #5490), p53 (1C12) (Cell Signaling, #2524S), and HRP-conjugated beta Actin (Proteintech, #HRP-60008). Antibody detection was accomplished using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and the chemiluminescence signals developed after incubation with ECL (Azure Biosystems) were detected using C-400 imaging system (Azure Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

All graphs, statistical analysis, and calculation of p-values were carried out using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Overall survival and tumor-free survival were plotted by Kaplan-Meier curves and analyzed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The hazard ratios, indicating changes in tumor incidence rate, were calculated from the slopes of tumor-free survival curves and estimated based on log-rank test.

Results

Effect of SIRT2 and SIRT3 Loss on Body Weight Upon CR and HFD

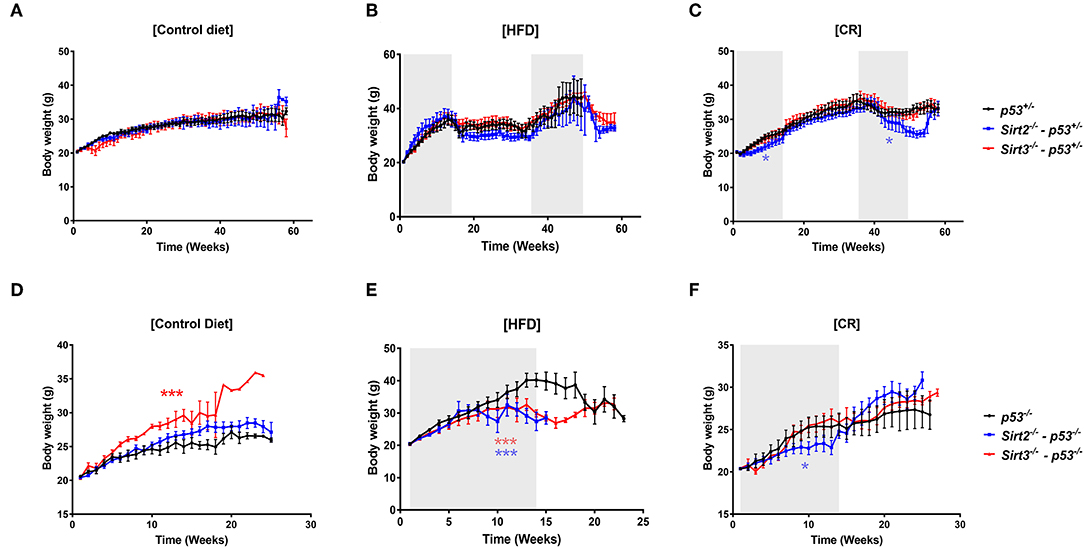

No change in body weight of Sirt2−/− and Sirt3−/− mice fed on control diet was observed, as compared to control mice with the exception of Sirt3−/−; p53−/− mice which exhibited increased body weight (Figures 1A,D). Upon CR, all mice responded to the diet as evidenced by the decrease in body weight and the weight gain following withdrawal from calorie restriction (Figures 1C,F). Of note, Sirt2−/− mice appeared to show the greatest effect, based on the significant decreased body weight compared to other mice (Figures 1C,F). On the other hand, Sirt3−/− mice were indistinguishable compared to wild-type (Figures 1C,F) with regards to body weight following CR. This finding is consistent with previous reports showing no difference in the body weight of Sirt3 deleted mice compared to Sirt3 wild-type ones under CR conditions (29, 30). Upon HFD, although a similar gain weight was observed in all mice in the p53+/− background (Figure 1B), both Sirt2−/− and Sirt3−/− mice in the p53−/− background displayed decreased body weights as compared to control mice (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Body weight changes in response to the different diets. Body weights of Sirt2−/− (blue line), Sirt3−/− (red line), and control Sirt2wt/Sirt3wt (black line) mice heterozygous or nullizygous for p53 were measured weekly during exposure to (A,D) a control diet, (B,E) a high fat diet, or (C,F) a 30% calorie restricted diet. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

SIRT2 Deletion Abolishes the Cancer-Preventive Effect of CR

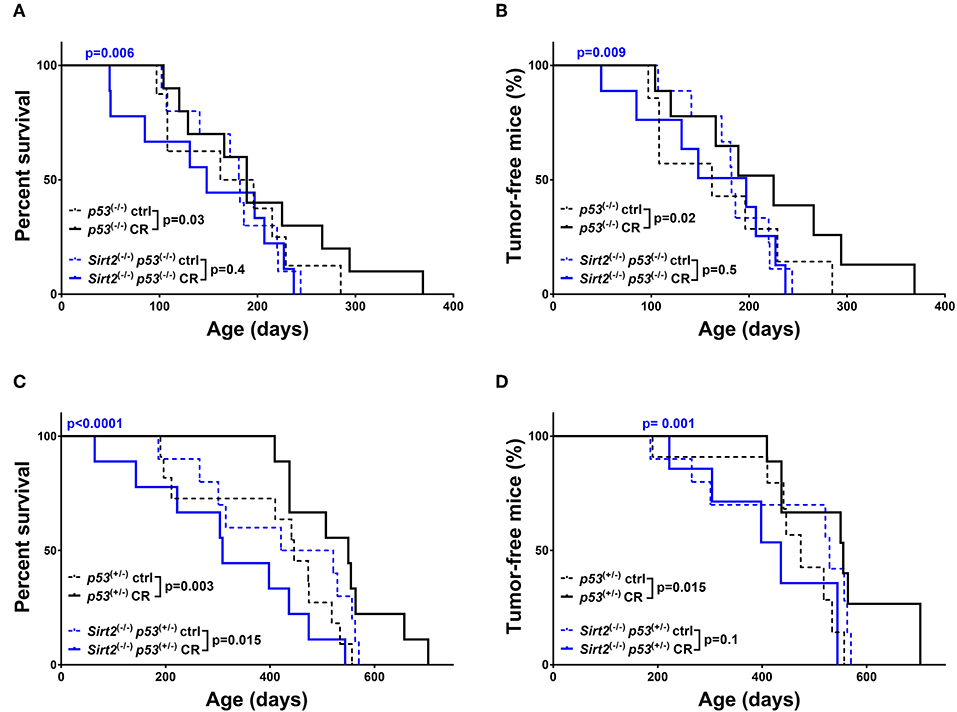

Consistent with previous studies (13, 31), CR exerted a beneficial effect in both p53+/− and p53−/− mice (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). This is reflected by increased overall survival (p53+/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.003 / p53−/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.03) and median survival (p53+/−: 446 days ctrl vs. 550 days CR/p53−/−: 179 days ctrl vs. 189 days CR), with concomitant significant decrease in tumor incidence (p53+/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.015-HR = 0.46/p53−/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.02-HR = 0.55, Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Of note, deletion of Sirt2 in both p53+/− and p53−/− backgrounds abolished the protective effect of CR. In both the Sirt2−/−; p53−/− (Figures 2A,B) and Sirt2−/−; p53+/− (Figures 2C,D) mice, the beneficial effect of CR as compared to the control diet was not observed based on the overall survival (Sirt2−/−; p53−/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.4 / Sirt2−/−; p53+/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.015) and the tumor incidence (Sirt2−/−; p53−/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.5/Sirt2−/−; p53+/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.1). This happened despite the decreased overall weight of calorie restricted Sirt2−/− mice as compared to Sirt2 wild-type mice (Figures 1C,F). Consistently, calorie restricted Sirt2−/−; p53−/−; and Sirt2−/−; p53+/− compared to p53−/− and p53+/− mice showed significantly decreased overall survival (CR: Sirt2−/−; p53−/− vs. p53−/−p = 0.006 / Sirt2−/−; p53+/− vs. p53+/−p < 0.0001) and increased tumor incidence (CR: Sirt2−/−; p53−/− vs. p53−/−p = 0.009 / Sirt2−/−; p53+/− vs. p53+/−p = 0.001).

Figure 2. Sirt2 deficiency abolished CR-mediated increased survival and tumor protection in mice. Kaplan-Meier curves show overall survival (A,C) and tumor free survival (B,D). Sirt2−/−; p53−/− (blue lines) and p53−/− (black lines) mice (A,B), Sirt2−/−; p53+/− (blue lines) and p53+/− (black lines) (C,D) were included in the analysis. Mice were either calorie restricted (CR) or fed ad libitum control diet. Solid lines represent mice in the CR groups, whereas control diet groups are represented in dotted lines. The blue p-values on the top of each curve represent the statistical difference in survival and tumor incidence between calorie restricted Sirt2−/− mice, and calorie restricted Sirt2+/+ mice with similar p53 genotypes. All p-values are calculated using the log rank test.

On the contrary, the beneficial effect from CR was maintained in the Sirt3−/−; p53−/− mice as evidenced by the increased survival (Sirt3−/−; p53−/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.05) and delay in tumor development (Sirt3−/−; p53−/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.001) (Figures 3A,B). Accordingly, survival and tumor incidence curves upon CR were identical in Sirt3−/−; p53−/−; and p53−/− mice suggesting that both benefited (CR: Sirt3−/−; p53−/− vs. p53−/−p = 0.1 survival/CR: Sirt3−/−; p53−/− vs. p53−/−p = 0.2 tumor incidence). Interestingly, this was not the case in the p53 heterozygous background, where Sirt3−/−; p53+/− mice did not benefit from CR (Sirt3−/−p53+/−: CR vs. ctrl p = 0.4 survival / CR vs. ctrl p = 0.1 tumor incidence) (Figures 3C,D and Supplementary Table 1). It is worth mentioning that p53+/− control diet-fed mice deleted for Sirt3 exhibited accelerated tumor incidence when compared to Sirt3 wild-type mice, (Figure 3D) which could possibly mask any benefits from CR. All together, our data suggest that among the two family members studied here, SIRT2 exhibits strong tumor suppressive properties upon CR regardless of the p53 genetic background, consistent with a role for SIRT2 in mediating the cancer preventive effect of CR.

Figure 3. Overall survival and tumor incidence in calorie-restricted Sirt3−/− mice. Kaplan-Meier curves show overall survival (A,C) and tumor free survival (B,D). Sirt3−/−; p53−/− (red lines) and p53−/− (black lines) mice (A,B), Sirt3−/−; p53+/− (red lines) and p53+/− (black lines) (C,D) were included in the analysis. Mice were either calorie restricted (CR) or fed ad libitum control diet. Solid lines represent mice in the CR groups, whereas control diet groups are represented in dotted lines. The red p-values on the top of each curve represent the statistical difference in survival and tumor incidence between calorie restricted Sirt3−/− mice, and calorie restricted Sirt3+/+ mice with similar p53 genotypes. All p-values are calculated using the log rank test.

SIRT3 Deletion Renders Mice Resistant to HFD-Induced Tumor Development

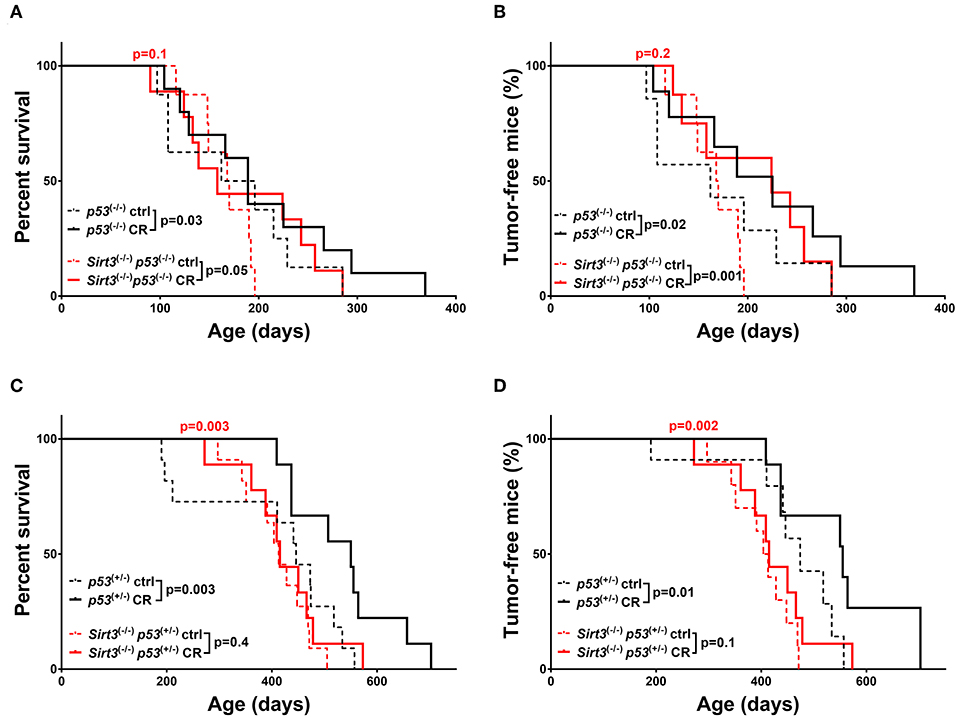

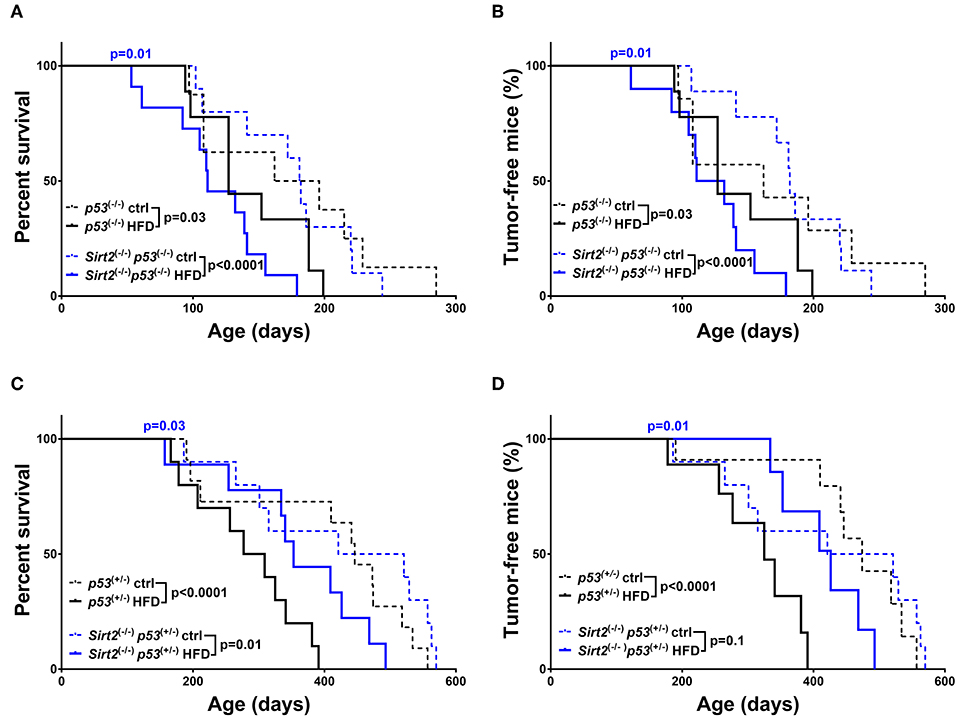

As already mentioned before, obesity, and high-fat diets exert the complete opposite effects compared to caloric restriction. Accordingly, both p53+/− and p53−/− mice fed on a HFD exhibited a significant decrease in overall survival (p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl p < 0.0001 / p53−/−: HFD vs. ctrl p = 0.03) and median survival (p53+/−: 446 days ctrl vs. 293 days HFD / p53−/−:179 days ctrl vs. 139.5 days HFD) which was further associated with increased tumor incidence (p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl p < 0.0001, HR = 4.01 / p53−/−: HFD vs. ctrl p = 0.03, HR = 1.58), as compared to the control diet group (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1). The detrimental effects of HFD were potentiated in Sirt2−/−; p53−/− mice after analyzing both overall survival (Sirt2−/−; p53−/−: HFD vs. ctrl p < 0.0001) and tumor incidence (Sirt2−/−; p53−/−: HFD vs. ctrl p < 0.0001) suggesting that SIRT2 exhibits tumor suppressive properties in this context as well (Figures 4A,B). However, a different response was observed in the p53 heterozygous background (Figures 4C,D). Although there was a trend toward decreased survival in the Sirt2−/−; p53+/− mice under HFD, they seemed to be partially protected as the decrease in tumor incidence did not reach statistical significance (Sirt2−/−; p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl survival p = 0.01 / tumor incidence p = 0.1). The protective effect of Sirt2 deletion in the p53 heterozygous background was further supported by the observation that HFD Sirt2−/−; p53+/− mice, relative to p53+/− mice, exhibited increased survival (HFD: Sirt2−/−; p53+/− vs. p53+/−p = 0.03) and decreased tumor incidence (HFD: Sirt2−/−; p53+/− vs. p53+/− p = 0.01).

Figure 4. Effect of Sirt2 deletion in overall survival and tumorigenesis upon HFD. Kaplan-Meier curves show overall survival (A,C) and tumor free survival (B,D). Sirt2−/−; p53−/− (blue lines) and p53−/− (black lines) mice (A,B), Sirt2−/−; p53+/− (blue lines) and p53+/− (black lines) (C,D) were included in the analysis. Mice were either fed a high fat diet (HFD) or fed ad libitum control diet. Solid lines represent mice in the HFD groups, whereas control diet groups are represented in dotted lines. The blue p-values on the top of each curve represent the statistical difference in survival and tumor incidence between HFD Sirt2−/− mice, and HFD Sirt2+/+ mice with similar p53 genotypes. All p-values are calculated using the log rank test.

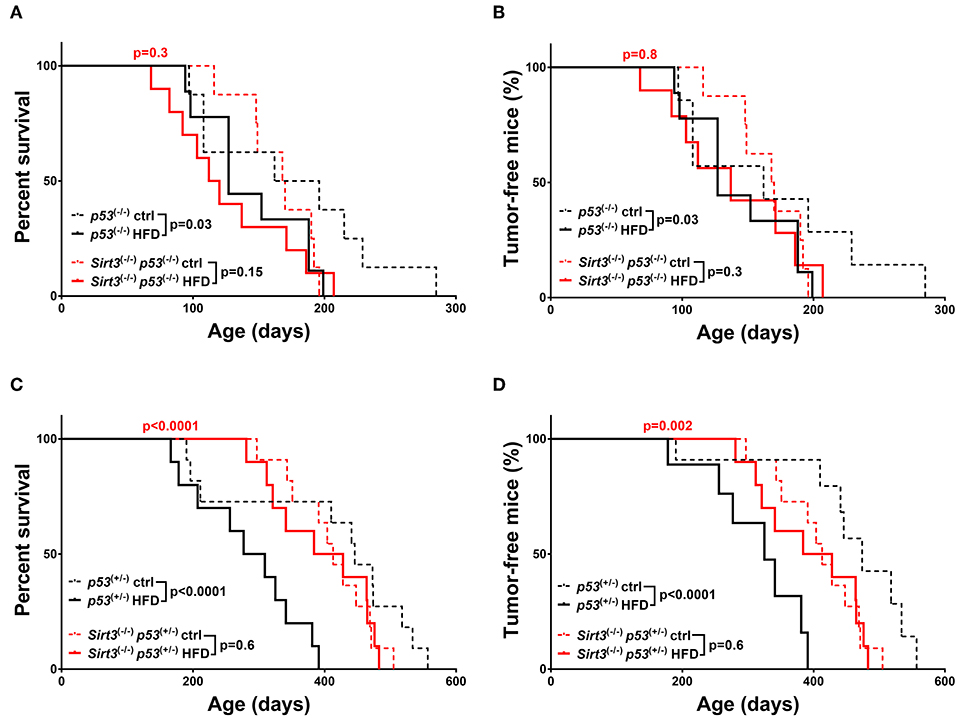

With regards to the other sirtuin family member, Sirt3 deletion resulted in decreased HFD-induced tumorigenesis, in both p53 backgrounds, supporting a tumor promoting role for SIRT3 in this context. In a p53 null background, Sirt3−/− mice fed a HFD did not show statistically significant decrease in survival (Sirt3−/−; p53−/−: HFD vs. ctrl p = 0.15) and tumor incidence (Sirt3−/−; p53−/−: HFD vs. ctrl p = 0.3) as compared to Sirt3+/+ mice (Figures 5A,B). The protective effect of Sirt3 loss was even more pronounced in the p53 heterozygous mice (Figures 5C,D). In contrast to the p53+/− mice, HFD did not decrease survival of Sirt3−/−p53+/− mice (p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl p < 0.0001 / Sirt3−/−; p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl p = 0.6). Consistently, HFD did not affect tumor incidence in mice with Sirt3 deletion (p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl p < 0.0001/Sirt3−/−; p53+/−: HFD vs. ctrl p = 0.6). As a result, Sirt3−/−; p53+/− mice exhibited significant protection against the tumor promoting effects of HFD compared to p53+/− mice. This is supported by the increased overall (HFD: p53+/− vs. Sirt3−/−; p53+/−p < 0.0001) and median (HFD: 293 days p53+/− vs. 406 days Sirt3−/−; p53+/−) survival, as well as decreased tumor incidence (HFD: p53+/− vs. Sirt3−/−; p53+/−p = 0.002) (Figures 5C,D and Supplementary Table 1). Taken together, these results highlight the different roles played by the two sirtuin family members in HFD-induced tumorigenesis. While SIRT2 maintains its tumor suppressive properties (at least in a p53 null background), SIRT3 switches to an oncogenic role in mice fed a HFD suggesting that SIRT3 inhibition renders mice resistant to HFD-induced tumorigenesis.

Figure 5. Sirt3 deletion exhibited a protective effect against HFD-induced tumorigenesis. Kaplan-Meier curves show overall survival (A,C) and tumor free survival (B,D). Sirt3−/−; p53−/− (red lines), and p53−/− (black lines) mice (A,B), Sirt3−/−; p53+/− (red lines), and p53+/− (black lines) mice (C,D) were included in the analysis. Mice were either fed a high fat diet (HFD) or fed ad libitum control diet. Solid lines represent mice in the HFD groups, whereas control diet groups are represented in dotted lines. The red p-values on the top of each curve represent the statistical difference in survival and tumor incidence between HFD Sirt3−/− mice, and HFD Sirt3+/+ mice with similar p53 genotypes. All p-values are calculated using the log rank test.

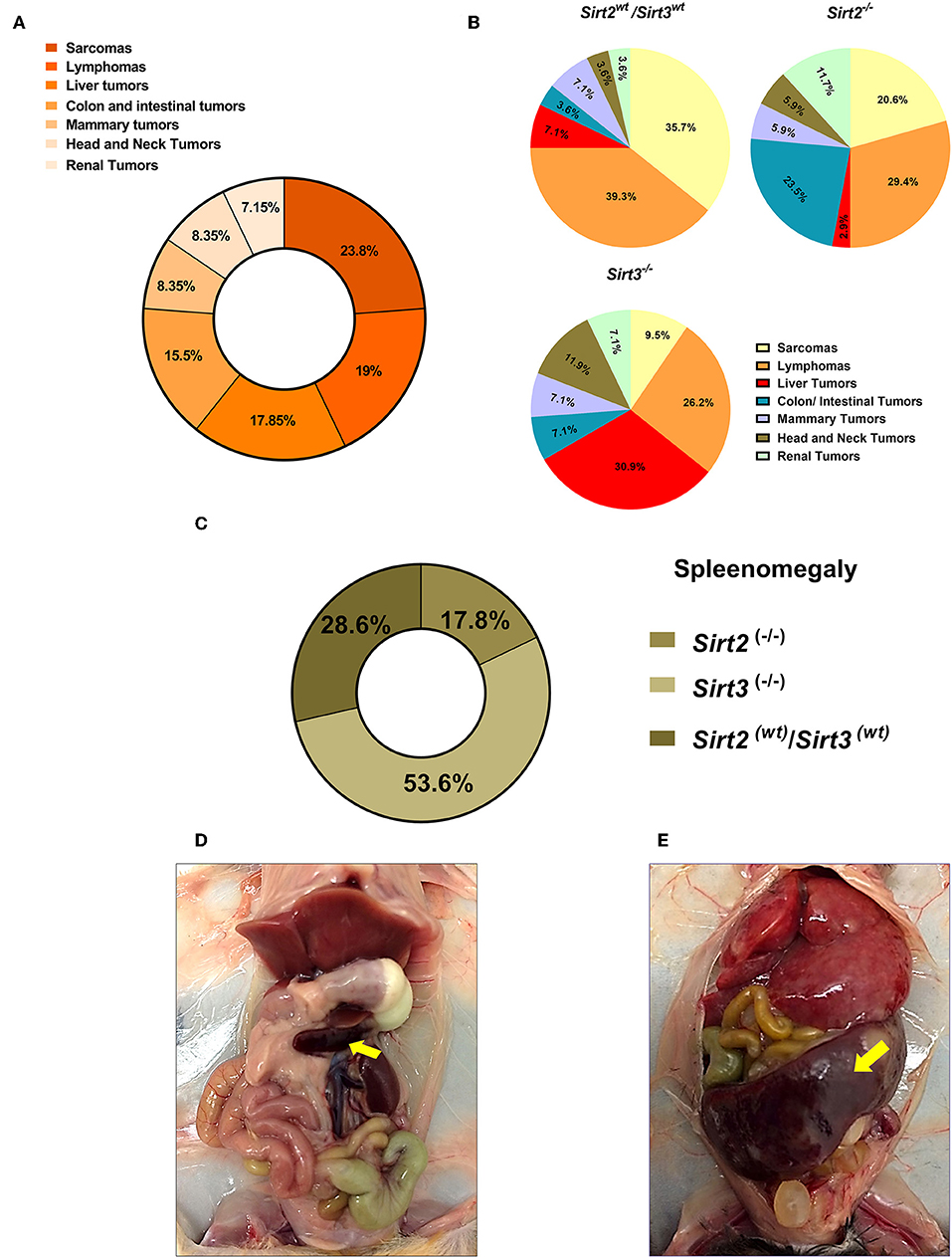

Tumor Spectrum Analysis in Sirt2 and Sirt3 Null Mice Upon CR and HFD

We noticed that p53-related tumors were the major tumors developed in mice of our study, with sarcomas and lymphomas representing more than 50% of all tumors (Figure 6A). Interestingly, we observed strong association between the loss of Sirt2/Sirt3 and certain tumors (Figure 6B and Supplementary Table 2). Under different dietary regimens, Sirt3 deficient mice experienced the highest incidence rate of liver tumors and the lowest incidence of sarcomas, either in p53+/− or p53−/− background, compared to the other groups. On the other hand, colon/intestinal and renal tumors were increased in Sirt2 knockout mice as compared to other genotypes. Moreover, we observed an increased incidence of splenomegaly in mice with Sirt3 deletion, when compared to the other genotypes, regardless of p53 status (Figures 6C–E).

Figure 6. Spectrum of tumors developed in the Sirt2 and Sirt3-deficient mice. (A) Percentages of different tumor types refer to proportion of all tumors reported, with sarcoma and lymphoma being the most prominent tumors reported. (B) Relative frequencies of the different types of tumors detected in Sirt2wt/Sirt3wt, Sirt2−/−, and Sirt3−/− mice, regardless of the dietary group, are displayed by pie charts. (C) 26 mice with splenomegaly were found in this study. Majority of cases (~54%) were reported in Sirt3 knockout mice. (D,E) Representative pictures of a mouse with normal spleen size (D) and a mouse with splenomegaly (E) are shown.

Discussion

SIRT2 is the least comprehensively studied member of mammalian sirtuins, especially for its role in the context of calorie restriction. The results from this study provide evidence, for the first time, to support a role for SIRT2 in mediating the protective effects of CR against tumorigenesis. Although controversial roles for SIRT2 in cancer have been described (32), our data show that SIRT2 exhibits tumor suppressive properties upon calorie restriction. Interestingly, this happened despite the decreased overall weight of calorie restricted Sirt2−/− mice as compared to Sirt2 wild-type mice suggesting that SIRT2-directed downstream signaling is impaired. The observed effect is consistent with previous studies showing that SIRT2 functions as a tumor suppressor (28, 33–35). Sirt2 loss negates the protective effect of CR on tumor development in a p53 mouse model and, therefore, unraveling downstream pathways regulated by SIRT2 in this context is warranted. It is worth mentioning that despite that several SRT2 deacetylation targets have been reported, a comprehensive analysis of SIRT2 targets using unbiased high throughput approaches is currently missing. We are in the process of completing such an analysis (data not show), which will enable to associate SIRT2 targets with molecular pathways related to CR and provide mechanistic insights. Very recently, Diaz-Ruiz et al. showed that upregulation of NQO1, an essential NADH-dehydrogenase that mediates redox control of metabolic homeostasis, mimicks aspects of CR including protection against carcinogenesis in mice (36). Of note, our latest study showed that NQO1 interacts with and activates SIRT2 in an NAD-dependent manner (37). Therefore, it is intriguing to further investigate whether SIRT2 activation mediates the CR-mimetic effects of NQO1 overexpression or whether SIRT2 overexpression alone can mimic the beneficial effects exerted by CR on cancer prevention, further emphasizing the potential for exploiting SIRT2 as a target for cancer prevention.

SIRT3 has been previously described to mediate CR-related health benefits (25, 30, 38). However, the involvment of SIRT3 in regulating diet-dependent tumor development is obscure. By using a p53 mouse model, here we show that SIRT3 plays a prominent role in HFD-induced tumorigenesis. Notably, Sirt3 deficient mice were resistant to the tumor promoting effect of HFD. Although it has been previously shown that Sirt3 loss in mice on a high-fat diet accelerates obesity, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and steatohepatitis (39), and SIRT3 preserves heart function and capillary density (40), our results show that Sirt3 loss increases survival and decreases tumor incidence upon HFD. Therefore, it can be proposed that SIRT3 exhibits oncogenic properties in the context of HFD-induced tumorigenesis and SIRT3 inhibition might be suggested as a strategy to mitigate the tumor promoting effects of HFD. The protective effect of Sirt3 loss, especially in the p53+/− background, was observed while mice gained weight as a response to the HFD. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that SIRT3 functions previously shown to support its role as an oncogene might be involved. In this regard, regulation of ROS production and mitochondrial metabolism (41–43) might provide the mechanistic link to explain the protective effect of SIRT3 inhibition in HFD-induced tumorigenesis. Of note, our unbiased proteomics-based analysis to detect proteins with increased acetylated levels in Sirt3−/− liver tissue as compared to Sirt3+/+ tissue revealed that fatty acid metabolic process was the most significantly enriched pathway using (Supplementary Figure 1). This is consistent with previous studies showing that SIRT3 regulates fatty acid oxidation (25, 44), while Perturbations in fatty acid metabolism have been associated with cancer (45). More importantly, regulation of fatty acid metabolism is critical especially in mice fed a HFD diet. Therefore, it is possible that dysregulation of this pathway in Sirt3−/− mice might provide some mechanistic insights to explain the observed resistance to HFD-induced tumorigenesis.

Both p53−/− and p53+/− mice were included in our analysis to address whether p53-dependent functions are involved. Upon CR, Sirt2 deletion abolished the protective effect in both genotypes, supporting a critical role for SIRT2 upon CR. In the HFD-fed mice, Sirt3 deletion rendered mice more resistant to HFD-induced tumorigenesis in both p53 genotypes, suggesting a role for SIRT3 in this context. p53 has been previously shown to regulate metabolism and mitochondrial function (46–48). The observed phenotypes in mice lacking p53 favor a role for these sirtuin family members involving p53-independent mechanisms. Although some responses seem to be stronger in the p53 heterozygous as compared to the p53 homozygous knockout mice, we believe that this might due to the different total time that the mice have been exposed to the two diets. In this regard, p53+/− mice develop tumors later in life compared to the p53−/− mice which allowed 2 cycles of feeding with the different diets as opposed to one cycle in the p53−/− mice.

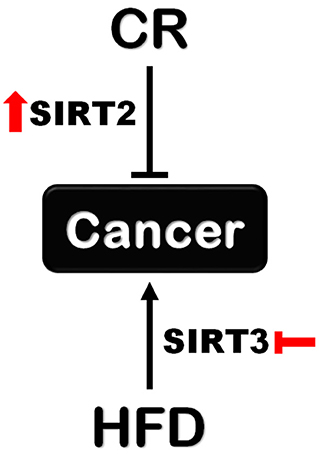

Collectively, our data support new context dependent roles for SIRT2 and SIRT3 in regulating the effects of CR and HFD on tumorigenesis. Given the lack of experimental data to address the contribution of situin family members other than SIRT1, our results reignite interest regarding the contribution of sirtuins under these specific metabolic conditions. Therefore, SIRT2 activation upon CR and SIRT3 inhibition upon HFD could be explored as new strategies to enhance CR-induced cancer prevention and decrease HFD-induced tumor development, respectively (Figure 7). Future studies focusing on unraveling downstream pathways and mechanisms hold the promise for identifying novel interventions to either mimic the cancer-preventive effect of CR or protect against HFD-induced tumorigenesis.

Figure 7. Different roles for SIRT2 and SIRT3 in tumorigenesis upon CR and HFD. Sirt2 is indispensable for the protective effect of CR against tumorigenesis supporting a cancer-preventive role for SIRT2 activation. On the other hand, Sirt3 loss renders mice resistant to HFD-induced tumorigenesis which supports the beneficial effect of SIRT3 inhibition in this context.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Northwestern University.

Author Contributions

MA and CO'C performed experiments and collected data. HJ maintained the mice colonies. EC helped with tissue collection and tissue sample analysis. MA performed statistical analyses. CO'C and AV designed the study. MA and AV prepared the manuscript.

Funding

AV was supported by NCI/NIH R01CA182506, a Lefkofsky Family Foundation Innovation Research Award, and the Lynn Sage Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of Center for Comparative Medicine (CCM)-Northwestern University, especially Tamara Cox and Matthew Castillo, for their significant help in this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2019.01462/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Colman RJ, Beasley TM, Kemnitz JW, Johnson SC, Weindruch R, Anderson RM. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun. (2014) 5:3557. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4557

2. Comfort A. The retardation of aging and disease by dietary restriction - weindruch, R, Walford, Rl. Nature. (1989) 338:469. doi: 10.1038/338469a0

3. Holehan AM, Merry BJ. The experimental manipulation of ageing by diet. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. (1986) 61:329–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1986.tb00658.x

4. Lawler DF, Larson BT, Ballam JM, Smith GK, Biery DN, Evans RH, et al. Diet restriction and ageing in the dog: major observations over two decades. Br J Nutr. (2008) 99:793–805. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507871686

5. Mattison JA, Roth GS, Beasley TM, Tilmont EM, Handy AM, Herbert RL, et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature. (2012) 489:318–21. doi: 10.1038/nature11432

6. Wanagat J, Allison DB, Weindruch R. Caloric intake and aging: mechanisms in rodents and a study in non-human primates. Toxicol Sci. (1999) 52:35–40. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/52.suppl_1.35

7. Weindruch R, Walford RL. Dietary restriction in mice beginning at 1 year of age: effect on life-span and spontaneous cancer incidence. Science. (1982) 215:1415–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7063854

8. Yu BP, Masoro EJ, Murata I, Bertrand HA, Lynd FT. Life span study of SPF Fischer 344 male rats fed ad libitum or restricted diets: longevity, growth, lean body mass and disease. J Gerontol. (1982) 37:130–41. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.2.130

9. Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span-from yeast to humans. Science. (2010) 328:321–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539

10. Winzell MS, Ahren B. The high-fat diet-fed mouse: a model for studying mechanisms and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. (2004) 53 (Suppl. 3):S215–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.S215

11. Kitahara CM, Flint AJ, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Bernstein L, Brotzman M, MacInnis RJ, et al. Association between class III obesity (BMI of 40-59 kg/m2) and mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. PLoS Med. (2014) 11:e1001673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001673

12. Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute (2018). Available online at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/, based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018.

13. Hursting SD, Perkins SN, Phang JM. Calorie restriction delays spontaneous tumorigenesis in p53-knockout transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1994) 91:7036–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7036

14. Mattison JA, Colman RJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Kemnitz JW, Roth GS, et al. Caloric restriction improves health and survival of rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:14063. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14063

15. Lv M, Zhu X, Wang H, Wang F, Guan W. Roles of caloric restriction, ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting during initiation, progression and metastasis of cancer in animal models: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e115147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115147

16. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. (2003) 348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423

17. Demark-Wahnefried W, Platz EA, Ligibel JA, Blair CK, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, et al. The role of obesity in cancer survival and recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2012) 21:1244–59. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0485

18. Oldham S. High fat diet induced obesity and nutrient sensing TOR signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 22:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.11.002

19. Guarente L. Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes Dev. (2013) 27:2072–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.227439.113

20. Lin SJ, Kaeberlein M, Andalis AA, Sturtz LA, Defossez PA, Culotta VC, et al. Calorie restriction extends Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan by increasing respiration. Nature. (2002) 418:344–8. doi: 10.1038/nature00829

21. Chalkiadaki A, Guarente L. The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2015) 15:608–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3985

22. Herranz D, Iglesias G, Munoz-Martin M, Serrano M. Limited role of Sirt1 in cancer protection by dietary restriction. Cell Cycle. (2011) 10:2215–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.13.16185

23. Feldman JL, Baeza J, Denu JM. Activation of the protein deacetylase SIRT6 by long-chain fatty acids and widespread deacylation by mammalian sirtuins. J Biol Chem. (2013) 288:31350–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.511261

24. Gomes P, Fleming Outeiro T, Cavadas C. Emerging role of sirtuin 2 in the regulation of mammalian metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2015) 36:756–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.08.001

25. Hebert AS, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Yu W, Bailey DJ, Selen ES, Boersma MD, et al. Calorie restriction and SIRT3 trigger global reprogramming of the mitochondrial protein acetylome. Mol Cell. (2013) 49:186–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.024

26. Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. (1994) 4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00002-6

27. Ahn BH, Kim HS, Song S, Lee IH, Liu J, Vassilopoulos A, et al. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:14447–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803790105

28. Kim HS, Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, Lahusen T, Xiao Z, Xu X, et al. SIRT2 maintains genome integrity and suppresses tumorigenesis through regulating APC/C activity. Cancer Cell. (2011) 20:487–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.004

29. Lombard DB, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Bunkenborg J, Streeper RS, Mostoslavsky R, et al. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. (2007) 27:8807–14. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01636-07

30. Someya S, Yu W, Hallows WC, Xu J, Vann JM, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell. (2010) 143:802–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.002

31. Kapahi P, Kaeberlein M, Hansen M. Dietary restriction and lifespan: lessons from invertebrate models. Ageing Res Rev. (2017) 39:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.005

32. Roth M, Chen WY. Sorting out functions of sirtuins in cancer. Oncogene. (2014) 33:1609–20. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.120

33. Head PE, Zhang H, Bastien AJ, Koyen AE, Withers AE, Daddacha WB, et al. Sirtuin 2 mutations in human cancers impair its function in genome maintenance. J Biol Chem. (2017) 292:9919–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.772566

34. Serrano L, Martinez-Redondo P, Marazuela-Duque A, Vazquez BN, Dooley SJ, Voigt P, et al. The tumor suppressor SirT2 regulates cell cycle progression and genome stability by modulating the mitotic deposition of H4K20 methylation. Genes Dev. (2013) 27:63–53. doi: 10.1101/gad.211342.112

35. Song HY, Biancucci M, Kang HJ, O'Callaghan C, Park SH, Principe DR, et al. SIRT2 deletion enhances KRAS-induced tumorigenesis in vivo by regulating K147 acetylation status. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:80336–49. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12015

36. Diaz-Ruiz A, Lanasa M, Garcia J, Mora H, Fan F, Martin-Montalvo A, et al. Overexpression of CYB5R3 and NQO1, two NAD(+) -producing enzymes, mimics aspects of caloric restriction. Aging Cell. (2018) 17:e12767. doi: 10.1111/acel.12767

37. Kang HJ, Song HY, Ahmed MA, Guo Y, Zhang M, Chen C, et al. NQO1 regulates mitotic progression and response to mitotic stress through modulating SIRT2 activity. Free Radic Biol Med. (2018) 126:358–71. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.08.009

38. Sheng S, Kang Y, Guo Y, Pu Q, Cai M, Tu Z. Overexpression of Sirt3 inhibits lipid accumulation in macrophages through mitochondrial IDH2 deacetylation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2015) 8:9196–201.

39. Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Jing E, Grueter CA, Collins AM, Aouizerat B, et al. SIRT3 deficiency and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation accelerate the development of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell. (2011) 44:177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.019

40. Zeng H, Vaka VR, He X, Booz GW, Chen J-X. High-fat diet induces cardiac remodelling and dysfunction: assessment of the role played by SIRT3 loss. J Cell Mol Med. (2015) 19:1847–56. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12556

41. Choi J, Koh E, Lee YS, Lee H-W, Kang HG, Yoon YE, et al. Mitochondrial Sirt3 supports cell proliferation by regulating glutamine-dependent oxidation in renal cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2016) 474:547–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.04.117

42. Cui Y, Qin L, Wu J, Qu X, Hou C, Sun W, et al. SIRT3 enhances glycolysis and proliferation in SIRT3-expressing gastric cancer cells. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0129834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129834

43. Torrens-Mas M, Oliver J, Roca P, Sastre-Serra J. SIRT3: oncogene and tumor suppressor in cancer. Cancers. (2017) 9:90. doi: 10.3390/cancers9070090

44. Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, Jing E, Schwer B, Lombard DB, et al. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. (2010) 464:121–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08778

45. Camarda R, Zhou AY, Kohnz RA, Balakrishnan S, Mahieu C, Anderton B, et al. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation as a therapy for MYC-overexpressing triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Med. (2016) 22:427–32. doi: 10.1038/nm.4055

46. Kruiswijk F, Labuschagne CF, Vousden KH. p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: a lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2015) 16:393–405. doi: 10.1038/nrm4007

47. Lago CU, Sung HJ, Ma W, Wang PY, Hwang PM. p53, aerobic metabolism, and cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2011) 15:1739–48. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3650

Keywords: SIRT2, SIRT3, calorie restriction, high fat diet, cancer, aging

Citation: Ahmed MA, O'Callaghan C, Chang ED, Jiang H and Vassilopoulos A (2020) Context-Dependent Roles for SIRT2 and SIRT3 in Tumor Development Upon Calorie Restriction or High Fat Diet. Front. Oncol. 9:1462. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01462

Received: 23 September 2019; Accepted: 05 December 2019;

Published: 08 January 2020.

Edited by:

Yong Teng, Augusta University, United StatesReviewed by:

Gizem Donmez, Adnan Menderes University, TurkeySonia Lain, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

Copyright © 2020 Ahmed, O'Callaghan, Chang, Jiang and Vassilopoulos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Athanassios Vassilopoulos, YXRoYW5hc2lvcy52YXNpbG9wb3Vsb3NAbm9ydGh3ZXN0ZXJuLmVkdQ==

Mohamed A. Ahmed1,2

Mohamed A. Ahmed1,2 Elliot D. Chang

Elliot D. Chang Athanassios Vassilopoulos

Athanassios Vassilopoulos