95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 24 April 2019

Sec. Women's Cancer

Volume 9 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00256

This article is part of the Research Topic Endometrial Cancer: From Biological to Clinical Approaches View all 12 articles

Qing Wang1,2†

Qing Wang1,2† Qi Wang1,2†

Qi Wang1,2† Lanbo Zhao3

Lanbo Zhao3 Lu Han1,2

Lu Han1,2 Chao Sun1,2

Chao Sun1,2 Sijia Ma1,2

Sijia Ma1,2 Huilian Hou4

Huilian Hou4 Qing Song1

Qing Song1 Qiling Li1,2*

Qiling Li1,2*More and more researchers have reported that dilatation and curettage (D&C) or Pipelle had low accuracy, high misdiagnosis, and insufficient rate. Endometrial cytology is often compared with histology and seems to be an efficient method for the diagnosis of endometrial disorders, especially endometrial cancer. We report a case of misdiagnosed endometrial cancer by D&C, but with a positive cytopathological finding. Following that, a meta-analysis including 4,179 patients of endometrial diseases with cyto-histopathological results was performed to assess the value of the endometrial cytological method in endometrial cancer diagnosis. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of the cytological method in detecting endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer was 0.91[95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74–0.97] and 0.96 (95% CI 0.90–0.99), respectively. The pooled positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio was 25.4 (95% CI 8.1–80.1) and 0.10 (95% CI 0.00–0.30), respectively. The diagnostic odds ratio which was usually used to evaluate the diagnostic test performance reached 260 (95% CI 36–1905). So we recommend that D&C and Pipelle are still practical procedures to evaluate the endometrium, cytological examinations should be utilized as an additional endometrial assessment method.

Endometrial cancer is becoming the primary reason of female deaths of genital track cancer in developed countries (1). Dilatation and curettage (D&C), as the traditional gold standard procedure for diagnosing endometrial cancer, is painful, expensive, requires general anesthesia and has a high rate of misdiagnosis (2). It has been reported that less than half of the uterine cavity is curetted in 60% of cases (3), and over 40% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia as a preoperative diagnosis have a final confirmation of endometrial cancer during hysterectomy (4, 5). Endometrial cytology is recently reported as a useful diagnostic method with high sensitivity and specificity in detecting endometrial malignancies (6–9), but no meta-analysis, which is considered more credible, has yet been performed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of endometrial cytology for endometrial carcinoma compared with histological diagnosis.

Here, we report a case of misdiagnosed endometrial cancer by D&C, but with a positive cytopathological finding. The patient has provided her written informed consent for the publication of this manuscript and any identifying images or data. After searching on PubMed, we believe it is the first case report of a misdiagnosis of endometrial cancer detected by cytopathology. Following this, a random-effects meta-analysis including 4,179 patients with both cytopathological and histopathological results was performed to assess the value of the endometrial cytology method in the diagnosis of endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer.

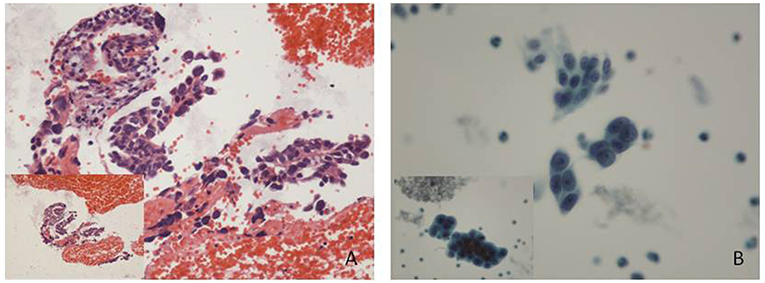

A 60-year-old post-menopause female, from Baoji City of the Shaanxi province in China, went to a local hospital complaining of abnormal uterine bleeding for 2 months. No high risk factor for endometrial cancer was observed, such as genetic factors, obesity, diabetes, a history of tamoxifen use and so on. Curettage was performed with a histopathological diagnosis of complex hyperplasia endometrium. No medicine or therapeutic curettage was effective for her with a continued bleeding. Her type B ultrasound in Shaanxi Provincial People's hospital showed a 0.8 cm-thick endometrium. Then, she turned to the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University for further treatment. After written informed consent, she volunteered to get cytological endometrial samplings by Li Brush (Xi'an Meijiajia Bio-Technologies Co. Ltd., China, 20152660054) for cytological examination before D&C. Her histopathological report revealed that papillary epithelial hyperplasia was found, and cancer was a concern according to the structure of tissue but could not be diagnosis due to insufficient tissue (Figure 1A). Meanwhile, the cytopathological report revealed that some malignant cells were found (Figure 1B). Her serum markers showed high serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9, 42.08 U/ml) and squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC, 6.10 ng/ml). A diagnostic laparoscopic hystero-salpingo-oophorectomy was performed and the patient was converted to a laparotomy when intraoperative frozen section examination revealed an endometrial serous carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Omentum resection, pelvic lymphadenectomy and para-aortic nodes dissection were performed. She was finally diagnosed with stage IIIc endometrial serous carcinoma.

Figure 1. Histological and cytological images. (A) Some papillary arranged epithelial dysplasia cells could be found in plenty of blood cells, with no tissue structure. (Hematoxylin-eosin staining; original magnification x10). (B) Endometrial carcinoma cells: cell clumps with irregular protrusions were rich in dimensional sense. Variable sizes, different shapes and hyperchromatic nuclei showed a loss of polarity within the epithelial sheet with irregularly clumped chromatin (Papanicolaou stain; original magnification x 20).

We searched the PubMed and Embase databases with the heading terms and keywords as “cytology” and “endometrial” from Jan 1, 1995 to June 1, 2018. Then, the results were manually selected for studies to include and repeatedly checked by a second investigator. We searched the full-text articles about the comparison of cytological results and the histological results in endometrial samples.

All candidate studies were evaluated and extracted by two independent investigators. Inclusion criteria: (1) patients were diagnosed by histopathological and cytological examination; (2) the histopathological results were paired with cytological results; (3) sufficient information was provided to conduct a statistical analysis; (4) endometrial cells were sampled by endometrial brushes; (5) studies were limited to human trials and published in English. Exclusion criteria include: (1) news, abstracts, case reports, letters, commentaries, and reviews studies; (2) other kinds of endometrial cells sampler like endometrial aspiration cytology; (3) different cytopathology report formats with others, that made it hard to re-group and analyze; and (4) studies with different positive result definition or duplicate data.

We set atypical hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma as the positive results and the others as the negative results, including normal endometrium, non-atypical hyperplasia, endometrial polyp, simple endometrial hyperplasia, complex endometrial hyperplasia and so on.

Two investigators separately extracted the following information from each research: the name of the first author, year of publication, cytological sampling method, cytological specimen preparation, histological sampling method, number of patients enrolled, and true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP), and true negative (TN) results. Any discrepancies between the two investigators were discussed by all the authors.

A quality assessment of eligible studies was evaluated using the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews-2 (QUADAS-2). There were 13 questions (each of which was scored as yes, no, or unclear): (1) Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? (2) Was a case–control design avoided? (3) Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? (4) Were the cytopathological diagnoses interpreted without knowledge of the results of the gold standard (histopathological diagnosis)? (5) whether the blind method was used for pathologists? (6) Was the histopathological diagnosis likely to correctly classify the target condition? (7) Was there an appropriate interval between the cytological sampling and histological sampling? (8) Did all patients receive the histopathological diagnosis? (9) Were all patients included in the analysis? (10) Whether the diagnostic test steps were detailed? (11) Were there concerns that the included patients and setting do not match the review question? (12) Were there concerns that the target condition as defined by the gold standard does not match the question? (13) Were there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or its interpretation differ from the review question?

The publication bias was checked by a Deeks funnel plot, and P < 0.05 was considered a significant publication bias. Statistical heterogeneity was detected by a Q test and an inconsistency index (I2), with significant heterogeneity set at P ≤ 0.05 and I2 > 50%. If there was no significance in heterogeneity (P > 0.05), a fixed effects model was chosen. If it was the opposite (P < 0.05), a random effects model was chosen.

According to TP, FN, FP and TN results, we calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR) (>10 suggested strong concordance), negative likelihood ratio (NLR) (<0.1 suggested strong concordance), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). PLR was calculated as: positive likelihood ratio = sensitivity/(1–specificity). NLR was calculated as: negative likelihood ratio = (1–sensitivity)/specificity. DOR was estimated by the Mantel-Haenszel formula. All statistical analyses, including 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were performed using STATA software (version 12.1, StataCorp LP) with the Midas module.

After searching on PubMed and Embase, 9 of 4,182 studies were included in meta-analysis. Figure 2 showed a flow diagram of the selection process. All data in researches were screened rigorously by our team.

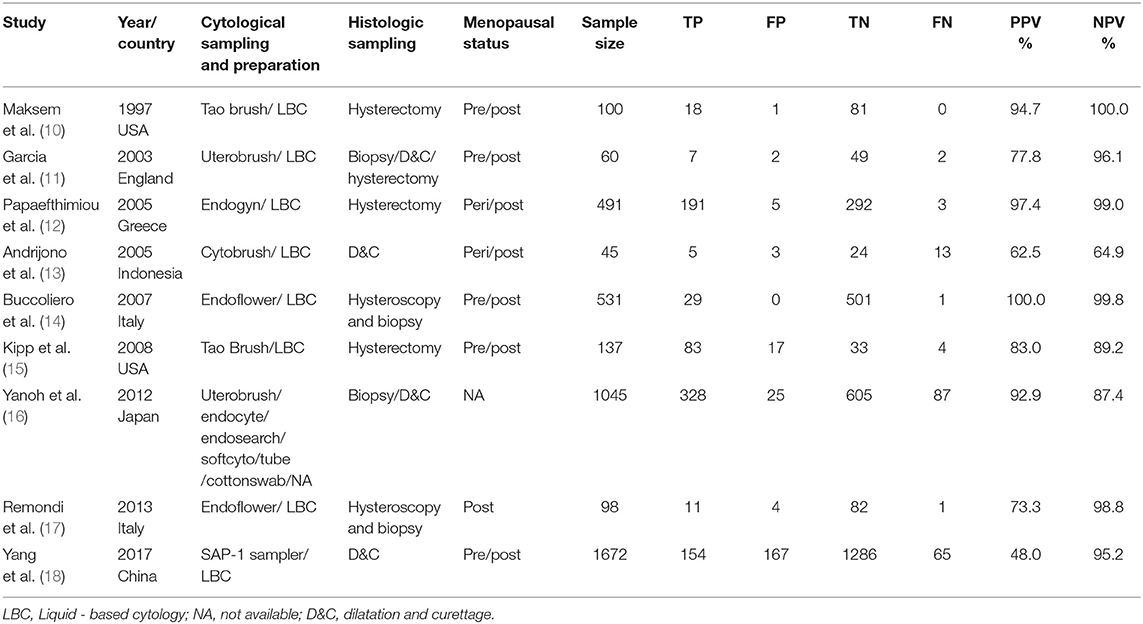

Our analysis included 9 eligible studies, which were shown in Table 1. In total, 2 studies were from Italy, 2 from the USA, 1 from China, 1 from Japan, 1 from England, 1 from Indonesia, and 1 from Greece. A total of 4,179 patients were included. Different endometrial brushes were used in these 9 studies, including the Tao brush (2), Endoflower (2), Endogyn (1), Cytobrush (1), and Uterobrush (1), and 1 study used six different devices. In all, 8 studies prepared the cytology specimens with a liquid-based cytology, and 1 study used the conventional way. In sum, 2 studies compared the cytological results to the D&C results, 3 studies compared the cytological results to the hysterectomy results, 2 studies compared the cytological results to the hysteroscopy and biopsy results, 1 study compared the cytological results to the biopsy or D&C results and 1 study compared the cytological results to the biopsy, D&C or hysterectomy results. Additionally, 5 studies research the pre/post-menopausal patients, 2 studies researched peri/post-menopausal patients, 1 study researched post-menopausal patients, and in 1 study, the menopause situation was unknown.

Table 1. Study characteristics of the nine included studies on the diagnostic accuracy of endometrial cytological sampling.

We assessed the quality of eligible studies by QUADAS-2 and found that the quality of all the studies was good (Table 2).

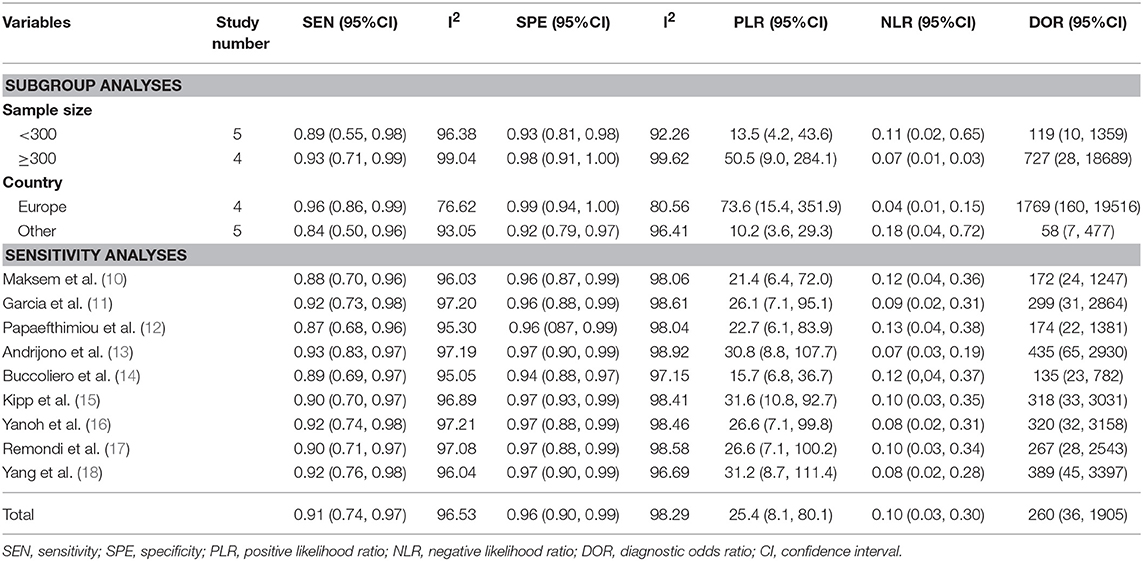

The pooled sensitivity and specificity of the cytological method in detecting endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer was 0.91 (95% CI 0.74–0.97) and 0.96 (95% CI 0.90–0.99), respectively (Figure 3). The pooled PLR and NLR were 25.4 (95% CI 8.1–80.1) and 0.10 (95% CI 0.00–0.30), respectively. The DOR which used to evaluate the diagnostic test performance,reached 260 (95% CI 36–1905).

I2 values of pooled sensitivity and specificity were 96.53 (95% CI, 95.23–97.83) and 98.29 (95% CI, 97.78–98.80), which indicated a statistically significant heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the influence of each study, in which each individual study was removed each time. No significant change or reversal of result was found (Table 3). The I2-value showed that none of the single study affected the heterogeneity of this meta-analysis.

Table 3. Sub-analysis and sensitivity analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of endometrial cytological sampling.

Subgroup 1: the corresponding values of the subgroup with sample size <300 were 0.89 (95% CI: 0.55, 0.98) for sensitivity and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.98) for specificity. While in subgroup sample size ≥300, the sensitivity was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.71, 0.99) and specificity was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.00). Subgroup 2: the corresponding values of the studies of European countries showed the sensitivity of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.99) and specificity of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.00) and in other countries were 0.84(95% CI: 0.50, 0.96) and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.79, 0.97), respectively (Table 3).

Deeks funnel plot asymmetry test was conducted to evaluate publication bias in this study (Figure 4), which showed statistically nonsignificant publication bias (P = 0.60).

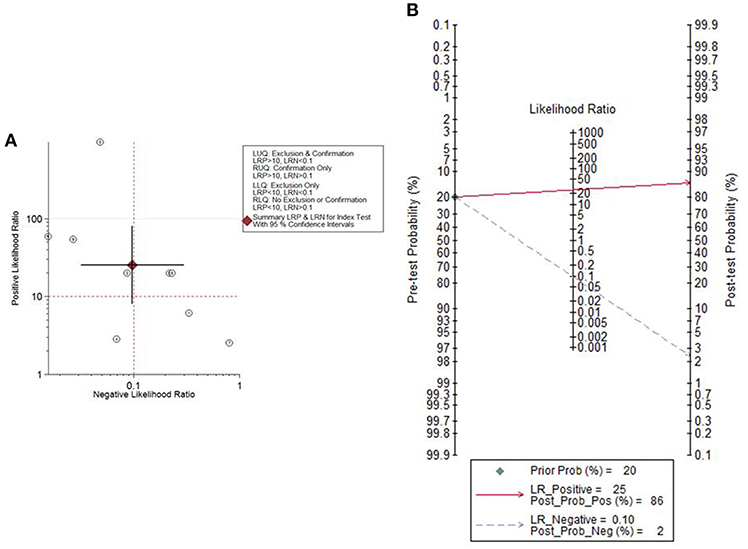

Given the PLR and NLR, the cytological detection method of endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer was located in the left upper quadrant (Figure 5A), indicating that the cytological detection method could serve as a test to confirm and exclude endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer. Fagan's plot indicated a dramatic improvement in posttest probability. When the pretest probability of endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer was set to 20%, using the cytological method as a source to detect the above diseases could significantly raise the posttest probability of a positive result to 86% and lower the posttest probability of a negative result to 2% (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. The likelihood ratio matrix and Fagan's plot. (A) The likelihood ratio matrix of the cytological method for the detection of endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer. (B) Fagan's plot presented the clinical utility of the cytological method for the detection of endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer.

It is currently estimated, that 60 million cervical cytology examinations are performed every year in the United States (19). Cytopathological screening, histopathological diagnosis and even the human papillomavirus vaccine are used to prevent and to make early diagnosis of cervical cancer, which helps the early detection and lowers the mortality of cervical cancer. In the absence of such effective screening programs and prevention methods, endometrial malignant diseases are becoming the most prevalent cancer of the female genital tract in developed countries, accounting for nearly 50% of all new diagnoses of gynecological cancer (20, 21). Nearly 75–80% of all endometrial cancer patients diagnosed at early stage (22, 23). But researchers are still paying attention to the early diagnosis of endometrial malignant diseases, especially its precancerous lesion.

Histological (D&C and Pipelle) and cytological diagnosis are two classes of endometrial sampling modalities. Both D&C and the most golden standard of evaluating the endometrium, hysteroscopic-guided uterine biopsy, are painful, expensive, and requires dilatation and anesthesia (24–26). Insufficient samples carry negative ramifications and increase the difficulty for the pathologist (27). An insufficient rate was reported as 6.4% (810/12,745) of curettage and 6.5% (310/4,777) of endometrial biopsy, and multiple factors contributed to such variation, including patient age, parity, endometrial thickness, sampling device, and provider technique. When stratified by age, the insufficient rate was 2.7% in the group of patients under 40 years old (3,454 cases), 5.8% in the group of 40 to 59 years old (11,838 cases), and 14.6% in the group of 60 years and older (2,230 cases) (28, 29). Sakhdari et al. (27) also showed that 15% (226/1,768) of the samples of women age 60 and older were reported as insufficient, and Barut et al. reported the insufficient rate was likely associated with menopause, with 6.5% (26/401) in premenopausal and 49.2% (120/244) in postmenopausal women (25). However, 75% of endometrial cancers occurred in women older than 55 years of age, with a median age of 62 (30). A meta-analysis evaluated the diagnostic rate of D&C and hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. It pointed out that D&C had a high rate of non-diagnostic samples 31% (range 7–76%) and a high failure rate of 11% (range 1–53%), which lead to a missing diagnosis rate of 7% (range 0–18%) (31).

Pipelle, as another widely used endometrial biopsy apparatus, is safe, cost-effective, and easily preformed (24). A meta-analysis of 39 studies, including 7,914 patients, revealed the concordance rate between Pipelle and D&C/hysteroscopy/hysterectomy in endometrial cancer detection of postmenopausal and premenopausal women was 99.6% and 91%, respectively (32). However, the Pipelle is random point sampling and said to sample 4.2% of the uterine cavity (33), and 25–36% women using Pipelle were found to have insufficient tissue for pathologic assessment (34).

Both D&C and Pipelle have their limitations in detecting endometrial cancer. Hysteroscopic guided biopsy showed a high diagnostic accuracy for endometrial cancer diagnosis (estimated sensitivity of 82.6% and specificity of 99.7%), data from a meta-analysis over 9,000 patients (35), but it could not be performed on asymptomatic women or used as a screening method. Are histological procedures (curettage or biopsy) enough to be the only methods in the diagnosis of endometrial diseases?

Endometrial cytology examination may be an inevitable method for endometrial cancer screening and a combined diagnostic procedure. It might have been hampered by the frequent presence of excess blood, mucus and overlapping cells and varied endometrium cell morphology with different sex hormone levels. However, liquid-based preparation techniques improve the diagnostic accuracy of endometrial cytology (6, 36), and more and more scholars have made efforts on the endometrial cytology reporting system (37–39). With the establishment and maturation of universal standards for the reporting system, endometrial cytology will truly play an important role in the diagnosis of endometrial diseases and endometrial cancer screening. Kondo et al. tested some different methods in 114 consecutive symptomatic women, and they reported that the sensitivity of detecting malignancy increased from 92% to 98% when endometrial cytology was combined with suction curettage (40).

Our meta-analysis showed that endometrial cytology had a high diagnostic accuracy and could serve as a test to confirm or exclude endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of the cytological method in detecting endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer was 0.91 (95% CI 0.74–0.97) and 0.96 (95% CI 0.90–0.99), respectively. Its diagnostic odds ratio reached 260 (95% CI 36–1905). The pooled positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio was 25.4 and 0.10, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that the test results of endometrial cytology are very accurate in diagnosing endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer.

Therefore, we recommend that D&C and Pipelle are still practical procedures to evaluate the endometrium, cytological examinations should be utilized as an additional endometrial assessment method, especially for women at high-risk for endometrial cancer.

Additionally, endometrial cytology is inexpensive, tolerated well and can be performed without anesthesia in an outpatient clinic. It is now the most common test for an initial evaluation of endometrial cancer in Japan (7) and has been encouraged as the first level screening method for women at high risk for endometrial cancer (37). Japanese epidemiological data revealed that the overall death rate of endometrial cancer decreased from 20.0 per 100,000 in 1950 to 8.0 per 100,000 in 1999, and this was thought to be a consequence of cytological screening (41).

Many researchers reported a high risk of endometrial cancer with positive cervical cytology (42, 43). Abnormal cervical cytology was associated with high-grade endometrial cancer, worse 5-year median recurrence-free survival and worse disease-specific survival (44). Positive cervical cytology should also be considered as a high risk of endometrial cancer, and endometrial cytology may benefit this kind of patients even with no clinical symptom.

An important strength of this meta-analysis is that we performed a thorough search for articles on the diagnostic accuracy in women with endometrial atypical hyperplasia or cancer using endometrial cytology. This article has several limitations. First, the risk of missing potentially relevant articles is a concern. Otherwise, the relatively small number of studies and variability in methods did not allow for more standard statistical analyses. Higher sensitivity and specificity could be found in subgroup of studies with sample size ≥ 300 and studies in European countries. However, after the subgroup analyses and sensitivity analysis, no factor showed associated with high heterogeneity. Patient age, menopause or not, different kinds of clinical symptoms, varies of cytological samplers and histological sampling methods might contribute to the high heterogeneity, and further study should approve it with enough data. What's more, the studies that are included in the meta-analysis are performed in symptomatic women. More data are needed before endometrial cytology being an effective screening tool for asymptomatic women with high-risks of endometrial cancer.

In conclusion, endometrial cytology is an efficient diagnostic method and could be applied in the diagnosis of endometrial disorders. The diagnostic accuracy of endometrial carcinoma will surely be improved by the combination of cyto-histopathological procedures and vaginal ultrasonography. Moreover, cytological examination, as a proper outpatient procedure, should be advised for endometrial screening, especial for those with high-risks of endometrial cancer.

QingW and QiW drafted the manuscript. QingW, LZ, and CS collected the case. QiW, LH, and SM performed the meta analysis. HH performed the pathological figure. QS helped to revise the manuscript. QL conceptualized the study.

This study was partly supported by the Shaanxi Provincial Collaborative Technology Innovation Plan (2017XT-026, 2018XT-002), Key Research and Development Project of Shaanxi Province Science and Technology Department (2017ZDXM-SF-068) and Medical Research Project of Xi'an Social Development Guidance Plan (2017117SF/YX011-3).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. (2015) 65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254

2. Telner DE, Jakubovicz D. Approach to diagnosis and management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Can Fam Physician. (2007) 53:58–64. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm014

3. Clark TJ, Gupta JK. Endometrial sampling of gynaecological pathology. Obstetr Gynaecol. (2002) 4:169–74. doi: 10.1576/toag.2002.4.3.169

4. Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. (2006) 106:812–819. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21650

5. Suh BE, Hung YY, Armstrong MA. Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: the risk of unrecognized adenocarcinoma and value of preoperative dilation and curettage. Obstetr Gynecol. (2009) 114:523–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b190d5

6. Norimatsu Y, Kouda H, Kobayashi TK, Shimizu K, Yanoh K, Tsukayama C, et al. Utility of liquid-based cytology in endometrial pathology: diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma. Cytopathology. (2010) 20:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2008.00589.x

7. Fujiwara H, Takahashi Y, Takano M, Miyamoto M, Nakamura K, Kaneta Y, et al. Evaluation of endometrial cytology: cytohistological correlations in 1,441 cancer patients. Oncology. (2015) 88:86–94. doi: 10.1159/000368162

8. Fambrini M, Sorbi F, Sisti G, Cioni R, Turrini I, Taddei G, et al. Endometrial carcinoma in high-risk populations: is it time to consider a screening policy? Cytopathology. (2014) 25:71–7. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12131

9. Yanaki F, Hirai Y, Hanada A, Ishitani K, Matsui H. Liquid-based endometrial cytology using surepath™ is not inferior to suction endometrial tissue biopsy in clinical performance for detecting endometrial cancer including atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Acta Cytol. (2017) 61:133−9. doi: 10.1159/000455890

10. Maksem MDJ, Sager DOF, Bender MDR. Endometrial collection and interpretation using the Tao brush and the CytoRich fixative system: a feasibility study. Diagnost Cytopathol. (1997) 17:339–46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199711)17:5<339::AID-DC6>3.0.CO;2-5

11. Garcia FAR, Barker B, Davis JD, Shelton T, Harrigill K, Schalk N, et al. Thin-layer cytology and histopathology in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. J Reprod Med. (2003) 48:882–8. doi: 10.1023/B:JARG.0000006710.64788.99

12. Papaefthimiou M, Symiakaki H, Mentzelopoulou P, Giahnaki AE, Voulgaris Z, Diakomanolis E, et al. The role of liquid-based cytology associated with curettage in the investigation of endometrial lesions from postmenopausal women. Cytopathology. (2005) 16:32–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2004.00224.x

13. Andrijono A, Prayitno GD, Hamdani C. Diagnostic test of endometrial cytobrush in cases of perimenopausal and postmenopausal hemorrhage. Med J Indonesia. (2005) 14:87–91. doi: 10.13181/mji.v14i2.181

14. Buccoliero AM, Gheri CF, Castiglione F, Garbini F, Barbetti A, Fambrini M, et al. Liquid-based endometrial cytology: cyto-histological correlation in a population of 917 women. Cytopathology. (2007) 18:241–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00463.x

15. Kipp BR, Medeiros F, Campion MB, Distad TJ, Peterson LM, Keeney GL, et al. Direct uterine sampling with the Tao brush sampler using a liquid-based preparation method for the detection of endometrial cancer and atypical hyperplasia: a feasibility study. Cancer. (2008) 114:228–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23636

16. Yanoh K, Hirai Y, Sakamoto A, Aoki D, Moriya T, Hiura M, et al. New terminology for intrauterine endometrial samples: a group study by the japanese society of clinical cytology. Acta Cytol. (2012) 56:113–4. doi: 10.1159/000336258

17. Remondi C, Sesti FF, Bonanno E, Pietropolli A, Piccione E. Diagnostic accuracy of liquid-based endometrial cytology in the evaluation of endometrial pathology in postmenopausal women. Cytopathology. (2013) 24:365–71. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12013

18. Yang X, Ma K, Chen R, Zhao J, Wu C, Zhang N, et al. Liquid-based endometrial cytology associated with curettage in the investigation of endometrial carcinoma in a population of 1987 women. Arch Gynecol Obstetr. (2017) 296:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4400-2

19. Cohen CJ, Gusberg SB. Screening for endometrial cancer. Clin Obstetr Gynecol. (2008) 114:219–21. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23705

20. Sorosky JI. Endometrial cancer. Obstetr Gynecol. (2012) 120:383–397. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182605bf1

21. Bakkum-Gamez JN, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Laack NN, Mariani A, Dowdy SC. Current issues in the management of endometrial cancer. Mayo Clinic Proceed. (2008) 83:97–112. doi: 10.4065/83.1.97

22. Bijen CBM, Bock GHD, Vermeulen KM, Arts HJG, Brugge HGT, Sijde RVD, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy is preferred over laparotomy in early endometrial cancer patients, however not cost effective in the very obese. Eur J Cancer. (2011) 47:2158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.035

23. Seebacher V, Schmid M, Polterauer S, Hefler-Frischmuth K, Leipold H, Concin N, et al. The presence of postmenopausal bleeding as prognostic parameter in patients with endometrial cancer: a retrospective multi-center study. BMC Cancer. (2009) 9:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-460

24. Abdelazim IA, Aboelezz A, Abdulkareem AF. Pipelle endometrial sampling versus conventional dilatation & curettage in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Turkish German Gynecol Assoc. (2013) 14:1–5. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2013.01

25. Barut A, Barut F, Arikan I, Harma M, Harma MI, Ozmen BU. Comparison of the histopathological diagnoses of preoperative dilatation and curettage and hysterectomy specimens. J Obstetr Gynaecol Res. (2012) 38:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01633.x

26. Su H, Huang L, Huang KG, Yen CF, Han CM, Lee CL. Accuracy of hysteroscopic biopsy, compared to dilation and curettage, as a predictor of final pathology in patients with endometrial cancer. Taiwanese J Obstetr Gynecol. (2015) 54:757–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2015.10.013

27. Sakhdari A, Moghaddam PA, Liu Y. Endometrial samples from postmenopausal women: a proposal for adequacy criteria. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2016) 35:525–30. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000279

28. Williams A, Brechin S, Porter A, Warner P, Critchley H. Factors affecting adequacy of Pipelle and Tao Brush endometrial sampling. BJOG. (2008) 115:1028–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01773.x

29. Kandil D, Yang X, Stockl T, Liu Y. Clinical outcomes of patients with insufficient sample from endometrial biopsy or curettage. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2014) 33:500–6. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000085

30. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. National Cancer Institute (2013).

31. Van HN, Prins MM, Bongers MY, Opmeer BC, Sahota DS, Mol BW, et al. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2016) 197:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.12.008

32. Dijkhuizen FP, Mol BW, Brölmann HA, Heintz AP. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in the diagnosis of patients with endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia: a meta-analysis. Cancer. (2000) 89:1765–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001015)89:8<1765::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-F

33. Demirkiran F, Yavuz E, Erenel H, Bese T, Arvas M, Sanioglu C. Which is the best technique for endometrial sampling? Aspiration (pipelle) versus dilatation and curettage (D&C). Arch Gynecol Obstetr. (2012) 286:1277–82. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2438-8

34. Tanriverdi HA, Barut A, Gun BD, Kaya E. Is pipelle biopsy really adequate for diagnosing endometrial disease. Medical Sci Monitor. (2004) 10:CR271–4. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2004206-7710

35. Gkrozou F, Dimakopoulos G, Vrekoussis T, Lavasidis L, Koutlas A, Navrozoglou I, et al. Hysteroscopy in women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a meta-analysis on four major endometrial pathologies. Arch Gynecol Obstetr. (2015) 291:1347. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3585-x

36. Norimatsu Y, Kouda H, Kobayashi TK, Moriya T, Yanoh K, Tsukayama C, et al. Utility of thin-layer preparations in the endometrial cytology: evaluation of benign endometrial lesions. Ann Diagnost Pathol. (2008) 12:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2007.05.005

37. Fulciniti F, Yanoh K, Karakitsos P, Watanabe J, Di LA, Margari N, et al. The Yokohama system for reporting directly sampled endometrial cytology: the quest to develop a standardized terminology. Diagnost Cytopathol. (2018) 46:400–12. doi: 10.1002/dc.23916

38. Shinagawa A, Kurokawa T, Yamamoto M, Onuma T, Tsuyoshi H, Chino Y, et al. Evaluation of the benefit and use of the new terminology in endometrial cytology reporting system. Diagnost Cytopathol. (2018) 46:314–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.23901

39. Margari N, Pouliakis A, Aninos D, Meristoudis C, Stamataki M, Panayiotides I, et al. Internal quality control in an academic cytopathology laboratory for the introduction of a new reporting system for endometrial cytology. Diagnost Cytopathol. (2017) 45:883–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.23787

40. Kondo E, Tabata T, Koduka Y, Nishiura K, Tanida K, Okugawa T, et al. What is the best method of detecting endometrial cancer in outpatients?-Endometrial sampling, suction curettage, endometrial cytology. Cytopathology. (2008) 19:28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00509.x

41. Nagase E, Yasuda M, Kajiwara H, Osamura RY, Yoshitake T, Hirasawa T, et al. Uterine body cancer mass screening at Tokai University Hospital. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. (2004) 29:43–8.

42. Tate K, Yoshida H, Ishikawa M, Uehara T, Ikeda S, Hiraoka N, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with early-stage uterine serous carcinoma without adjuvant therapy. J Gynecol Oncol. (2018) 29:e34. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e34

43. van Doom HC, Opmeer BC, Kooi GS, Ewing Graham PC, Kruitwagen RF, Mol BW. Value of cervical cytology in diagnosing endometrial carcinoma in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Cytol. (2009) 53:277–82. doi: 10.1159/000325308

Keywords: cytology, histology, endometrial cancer, diagnosis, atypical hyperplasia

Citation: Wang Q, Wang Q, Zhao L, Han L, Sun C, Ma S, Hou H, Song Q and Li Q (2019) Endometrial Cytology as a Method to Improve the Accuracy of Diagnosis of Endometrial Cancer: Case Report and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 9:256. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00256

Received: 15 September 2018; Accepted: 21 March 2019;

Published: 24 April 2019.

Edited by:

Massimo Nabissi, University of Camerino, ItalyReviewed by:

Johanna Pijnenborg, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, NetherlandsCopyright © 2019 Wang, Wang, Zhao, Han, Sun, Ma, Hou, Song and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiling Li, bGlxaWxpbmdAbWFpbC54anR1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.