- Biochemistry, Biochemical Analysis and Matrix Pathobiology Research Group, Laboratory of Biochemistry, Department of Chemistry, University of Patras, Patras, Greece

Extracellular matrix (ECM) components form a dynamic network of key importance for cell function and properties. Key macromolecules in this interplay are syndecans (SDCs), a family of transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Specifically, heparan sulfate (HS) chains with their different sulfation pattern have the ability to interact with growth factors and their receptors in tumor microenvironment, promoting the activation of different signaling cascades that regulate tumor cell behavior. The affinity of HS chains with ligands is altered during malignant conditions because of the modification of chain sequence/sulfation pattern. Furthermore, matrix degradation enzymes derived from the tumor itself or the tumor microenvironment, like heparanase and matrix metalloproteinases, ADAM as well as ADAMTS are involved in the cleavage of SDCs ectodomain at the HS and protein core level, respectively. Such released soluble SDCs “shed SDCs” in the ECM interact in an autocrine or paracrine manner with the tumor or/and stromal cells. Shed SDCs, upon binding to several matrix effectors, such as growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines, have the ability to act as competitive inhibitors for membrane proteoglycans, and modulate the inflammatory microenvironment of cancer cells. It is notable that SDCs and their soluble counterparts may affect either the behavior of cancer cells and/or their microenvironment during cancer progression. The importance of these molecules has been highlighted since HSPGs have been proposed as prognostic markers of solid tumors and hematopoietic malignancies. Going a step further down the line, the multi-actions of SDCs in many levels make them appealing as potential pharmacological targets, either by targeting directly the tumor or indirectly the adjacent stroma.

Tumor Microenvironment and HSPGs

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is a dynamic non-cellular network of macromolecules present within all tissues and organs. It is composed of a large collection of biochemically distinct components including collagens, elastin, fibronectin (FN), laminins, tenascin, vitronectin, thrombospondin, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), various proteoglycans (PGs), and hyaluronan (HA). These molecules of unique properties are able to provide the necessary mechanical structure for the cellular components but also contribute in several processes that are crucial for tissue morphogenesis, differentiation, and homeostasis (1, 2).

Cancer research has expanded and increasingly evolved over the years but there are still many unanswered questions due to the biological complexity of this pathological condition. One aspect of this complexity is attributed to the essential role of the stromal tissue in cancer progression. The tumor microenvironment is supported by a vascular network and contains several ECM molecules, fibroblasts, migratory immune cells, and neural elements, all within a milieu of cytokines and growth factors (3–5). The crosstalk between the cancer and the host stroma cells, via autocrine and paracrine complex mechanisms, recruits and activates the neighboring normal cells. This results in the re-organization of the stroma and it is often referred to as “reactive stroma” (6, 7). Both activated stromal and cancer cells exhibit a significant role in the re-organization of ECM in order to facilitate tumor cell growth, migration, and invasion (8, 9). PGs are among the key player components of stroma- and cancer-derived ECM. They interact with several structural components and matrix-associated proteins [growth factors, cytokines, and growth factor receptor (GF-R)] and during cancer progression their expression in tumor microenvironment is markedly modified (10). Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) can be found both at the cellular and extracellular matrices. The principal representatives of HSPGs are syndecans (SDCs), which have a single transmembrane domain; glypicans, which are linked to the outer plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor; and a group of secreted PGs, including perlecan, agrin, collagen XVIII, and the testican family (11, 12). They are present almost in all cell types and tissues and they act as regulators not only in normal but also in pathological conditions (13). Their regulatory role is attributed to their ability to collaborate with other matrix components contributing to basement membrane structural integrity and cell–cell as well as cell–matrix interactions. HSPGs, via their covalently bound heparan sulfate (HS) chains bind cytokines, chemokines, morphogens, and growth factors, serving also as signaling co-receptors (11, 14).

In the present review, we have addressed our attention to SDCs. There are four types of SDCs in mammals and probably in all vertebrates, whereas all the invertebrates and primitive chordates possess only one (15, 16). SDCs possess three distinct structural domains: the ectodomain with an N-terminal signal peptide and several sites for glycosaminoglycan attachment, which have a low sequence homology among the different types of SDCs, the highly conserved single transmembrane domain, and the short C-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Apart from HS chains, chondroitin sulfate (CS) GAG-attachment in SDC-1 and -3 is also reported (17, 18). The majority of cell types with the exception of the erythrocytes express at least one type of SDC and in several cases all four. Specifically, SDC-1, mainly expressed in epithelia as well as in some leukocytes, is responsible for mesenchyme condensation during development. On the other hand, its structural counterpart, SDC-3 is present in neural tissue and the developing musculoskeletal system. SDC-2 is distributed in mesenchymal tissues, fibroblasts, liver, and developing neural tissue, whereas SDC-4 is ubiquitously distributed (16, 19).

Syndecans are involved in a variety of complex signaling events through which they play regulatory roles for cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, and migration (8). Using mutated mice with altered HSPG core proteins expression as a tool, some important functions for SDCs have been identified. Results highlighted that the mice in which SDCs-1, -3, or -4 have been depleted, develop normally, are fertile, and have no obvious pathologies. Based on these observations, it is stated that the redundancy of an individual SDC has no critical role during development (20–23). Notably, SDC-1 null mice had epithelial cell migration defects, whereas SDC-3 null mice exhibited impaired radial migration and neural migration in development as well as partial resistance to obesity. A possible implication of SDC-3 has occurred in satellite cell maintenance, proliferation, and differentiation (24). On the other hand, SDC-4 is implicated in processes involving vascular defects in fetal placental labyrinth and poor angiogenic response in postnatal wound healing (14, 24). We should note at this point that SDC-2 mutants have not been reported so far, but it has been established that SDC-2 plays an important function in the angiogenic process (25). Moreover, Noguer et al. showed that SDC-2 impairs angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells (26).

Syndecans as Cell Surface Mediators in Cancer Biology

Functions Mediated by Syndecans–ECM Interactions

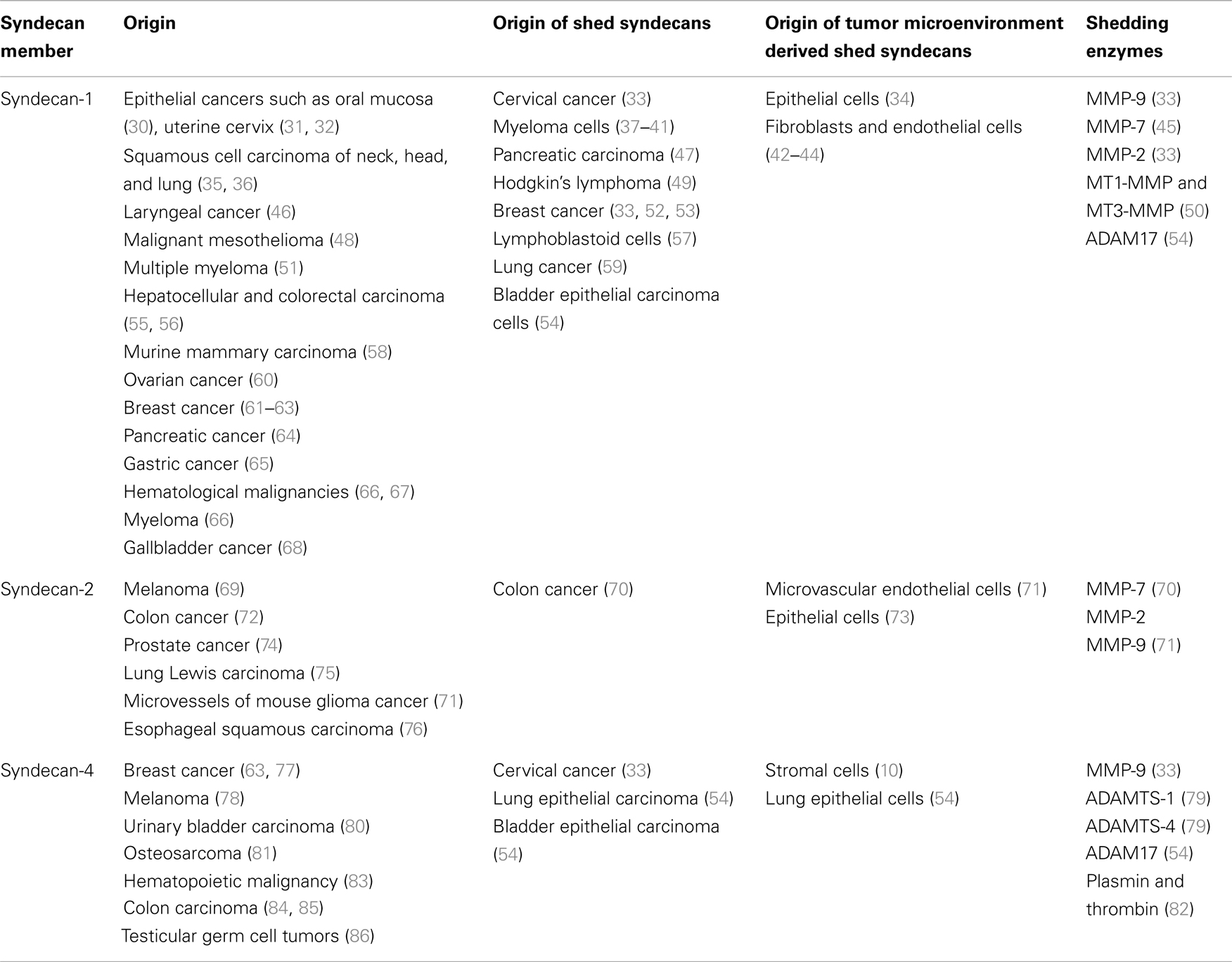

Syndecans exhibit a great variety in their localization and function and as a result, they are considered as key regulators of tumorigenesis and tumor progression (27). It is well established that SDCs may serve as biomarkers for early detection or severity of cancer. As presented in Table 1, they are expressed in a variety of cancer types, apart from SDC-3 that is not implicated in cancerous conditions. To note, SDCs possess diverse roles each time based on the type and stage of cancer, acting either as inhibitors or promoters of tumor progression (28, 29).

Several ECM macromolecules, such as FN, tenascin-C, collagen, thrombospondin, laminin, glycoproteins, etc., are documented to interact with SDCs. These specific interactions depend on the length diversity and extent of GAGs chains sulfation, which is actually different among cell types. On the other hand, the heparin-binding motifs of ECM macromolecules are responsible for SDCs–matrix interactions (19). Such close dynamic relations initiate signaling cascades, that in turn result in altered functional cellular properties. In highly metastatic colorectal cancer cells, SDC-2 is enhanced by stromal secreted FN promoting cell adhesion via simultaneous up-regulation of α2, β1-integrin, and FAK phosphorylation (87). Accordingly, high expression levels of SDC-4 and FN may be the underlying molecular alteration occurred in osteosarcoma, that lead to an aggressive phenotype (81). Furthermore, tenascin-C impairs the adhesive properties of FN by blocking SDC-4 co-receptor function in integrin signaling, thereby triggering tumor cell proliferation (88). Moreover, a peptide derived from tenascin-C, strongly activates β1-integrin functional activity through binding with SDC-4. These interactions lead to induced apoptosis selectively in hematopoietic tumor cells, which express adequate amounts of both integrin α4β1 (very late antigen-4, VLA-4) and SDC-4, driving FN-mediated effects (83). SDC-1 and -4 in collagen microenvironment create a complex interplay between integrin α2β1 and membrane type 1 metalloproteinase [MT1-matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)] in K-Ras mutated cells, promoting cell invasion and metastasis (89). Moreover, SDC-1 is essential for cell motility and invasion in collagen substrate via the modulation of RhoA and Rac activity in squamous cell carcinoma (90). Thrombospondin-1, a homotrimeric protein, is implicated in cancer cell adhesion, migration, and invasion as it activates the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (91). On the top of that glioma cells secrete high levels of thrombospondin-1, which bind to ανβ3, α3β1 integrins, and SDC-1, participating in carcinoma cell motility and migration (92). Notably, SDC-1 expression in association with the high expression of thrombospondin-1 is mediated through NF-kB signaling effector (93).

Syndecans as Co-Receptors for Growth Factors Signaling

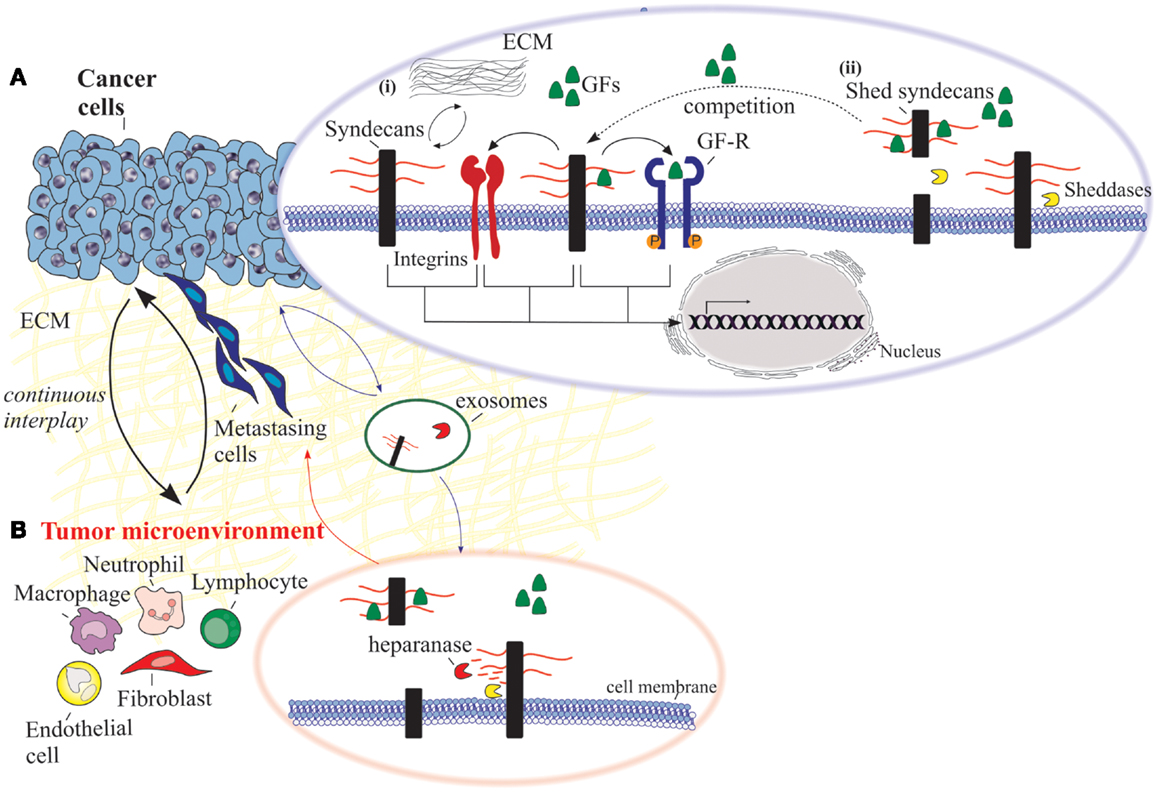

Syndecans are associated with several cell surface receptors and therefore regulate dynamically the binding of their adjacent ligands, forming active complexes. Some of the most common regulatory interactions of SDCs involve growth factors, integrins, and other signaling molecules (Figure 1). Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs)-mediated signaling via FGFRs regulate development and homeostasis. Characteristically, in breast carcinoma cells SDC-1 and SDC-4 regulate the formation of FGF-2/HSPG/FGFR-1 complex, indicating the importance of altered HS chains sulfation pattern during malignant conditions (94). Further investigation of the underlying mechanism indicated that SDC-1 and FGF-2, but not FGFR-1, share a common transport route and co-localize with heparanase in the nucleus at mesenchymal tumor cells (95). However, the effect of SDC-1 translocation on malignant cells, it has not yet clarified. On the other hand, it is clearly stated in the literature that HS chains of SDC-1 in premalignant epithelial cells interact with both FGFR-1 and -2 signaling complexes and this interaction is directly associated with the progression of malignancy (96). Moreover, in melanoma cell lines the expression of SDCs CS/HS chains appears to be modulated by FGF-2, that in turn facilitates signaling (97).

Figure 1. An overview of the functional properties of syndecans in cancer cells and the adjacent tumor microenvironment. (A) Cancer cells: (i) syndecans interact with various ECM macromolecules derived either from stromal cells or tumor cells. Such interactions lead to integrin-mediated altered functional properties such as cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion. On the other hand, transmembrane syndecans interact with growth factors (GFs) via their HS chains and subsequently act as co-receptors for the respective growth factor receptor (GF-R). In both cases, integrins can co-interact with these complexes and as a consequence to mediate different signaling pathways. (ii) Syndecan shedding is a process that involves the proteolytic cleavage of their ectodomain near the plasma membrane by sheddases. It is also reported that the shed syndecans compete with their transmembrane counterparts for soluble GFs. Shedding of syndecans contributes to cancer progression and especially to the crosstalk between the tumor cells and their host microenvironment. Exosomes, extracellular vesicles that are secreted in high amounts in tumors, retain both heparanase and syndecan-1 as cargo within exosomes and subsequently influence not only the behavior of the tumor microenvironment within the tumor niche and distant sites, but also the growth of the metastasizing cells. (B) Tumor microenvironment. Heparanase plays a distinct role in the shedding of syndecans by cleaving HS chains promoting the shedding via sheddases. This action results in induced tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin growth factor (IGF) are key regulators of vascular, organ, and neural development, but are also related to angiogenesis and cancer progression (98). In multiple myeloma, SDC-1 promotes endothelial cells proliferation and survival by modulating VEGF–VEGFR-2 signaling pathway (99). In addition, VEGF expression is significantly upregulated in cells expressing high levels of heparanase, leading to decreased nuclear SDC-1 and an aggressive tumor phenotype (100). In another line of studies on human breast carcinoma, SDC-1 ectodomain, but not SDC-4, regulates ανβ3 integrin–SDC signaling complex (77, 101). Although the engagement between SDC-1 and ανβ3 integrin occurs through the SDC-1 ectodomain, the activation is correlated with the cytoplasmic domain. On top of that, the extracellular interaction of SDC-1 with ανβ3 integrin promotes the docking of IGFR with SDC-1 ectodomain. The formation of IGFR/SDC-1/integrin complex seems to be a crucial regulator for integrin-mediated effect in tumor cell metastasis and tumor-induced angiogenesis (102). On the other hand, in mouse fibroblasts, constitutive association of SDC-1 with β5 integrin appears to be important for ανβ5-dependent signaling (103). According to the above data, a recent study presented that vascular endothelial-cadherin induces SDC-1 complex with IGFR and the subsequent crosstalk between ανβ3 and VEGFR-2 on endothelial cells during angiogenesis (104).

Epidermal growth factor (EGF), IGF, and platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) are key players in several malignancies. In human mesothelioma, the presence of EGF, IGF, and PDGF-BB seems to regulate the levels of SDCs and these variations in the expression of SDCs are correlated with the growth factor signaling activation by an auto-regulatory loop mechanism (105). Histological immunostaining in patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma demonstrated that the expression of SDC-1 and EGFR is associated with patient survival (106). On the other hand, the low expression of SDC-1 stimulates the ovarian cancer cells invasion, mediated by heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF) through a urokinase-independent mechanism (60). Moreover, EGF-family ligands are essential for multiple myeloma cell growth via binding with HSPGs and especially with SDC-1, which is abundantly expressed in this malignancy (107). It is also of great importance to point out the role of EGFR/IGFR signaling pathways in the expression of SDCs-2 and -4 in hormone-dependent breast cancer. The variations in the expression levels of SDCs, mediated through EGFR/IGFR signaling pathways, are correlated also with the migratory potential of breast cancer cells (108). Furthermore, the abundant PDGF-BB in cell microenvironment stimulates fibroblasts migration, inducing the level of SDC-4 (109). On the contrary, PDGF-mediated signaling in glioma cells initiates an induction of migration via a SDC-4-independent action (110). Reduced levels of SDC-4 in non-seminomatous germ cell tumors are related to their metastatic potential, whereas stromal staining of SDC-4 in testicular germ cell tumors is correlated with angiogenesis (86). SDC-2 binds to TGF-β via HS chains and promotes TGF-β signaling (111). In fibrosarcoma cells, TGF-β2 via Smad2 promotes cell adhesion and this function is directly modulated through SDC-2 (112). SDC-1 expression in breast cancer stroma fibroblasts regulates cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and cell motility. On the other hand, SDC-2 seems to exert antifibrotic effect by promoting caveolin-1-mediated TGF-βRI internalization and inhibiting TGF-β1 signaling (44, 61, 113).

Shed Syndecans in Cancer Biology

As part of the normal turnover, SDCs undergo regulated proteolytic cleavage of their extracellular domain near the plasma membrane into the extracellular milieu. There it can be diffused away from the cell, be part of the ECM or remain soluble. In the soluble state, it can influence the surrounding or distal cells (37). This process is known as “shedding” and it happens under physiological conditions. However, shedding may be increased in response to stimuli (37, 114). The shed SDC not only downregulates signal transduction, but also converts the membrane-bound receptors into soluble effectors and/or antagonists. The remnant core protein at the cell surface loses its ability to bind ligands and can be further processed via intramembrane cleavage by the presenilin/γ-secretase complex (37).

Syndecan Sheddases

All mammalian SDC family members can be cleaved by extracellular proteases. The MMPs are zinc-dependent endopeptidases that play an important role at different stages of cancer. Several studies have shown that the expression of MMPs is upregulated during cancer progression, and it is directly associated with poor clinical prognosis (115). MMPs have been incriminated to shed the extracellular domain at membrane-proximal sites. For example, MMP-9 has been implicated in the stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1)-mediated shedding of SDC-1 and SDC-4 in HeLa cells (33). It has been reported that matrilysin (MMP-7) as well as the membrane-associated metalloproteinases MT1-MMP and MT3-MMP are responsible for SDC-1 cleavage, whereas the gelatinases MMP-2 and -9 cleave SDCs-1 and -2 (50). The ADAMTS (disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs) family is also implicated in SDC shedding. It has been reported that both ADAMTS-1 and -4 cleave SDC-4 near the first GAG-attachment site that eventually results in decreased cell adhesion and promotion of cell migration (37, 79). In addition, ADAM17 has been reported to shed SDC-1 and -4, effect that is diminished following ADAM17 knockdown (54). It is also worth noticing that human SDC-4 is cleaved by the serine proteases plasmin and thrombin (82). Shedding can occur at different cases and different sites at the core protein of SDCs. Focused studies on the shedding mechanism will improve our knowledge regarding their potential implication in cell function. An overview of the documented shed SDCs and the respective sheddases in various cancer types is presented in Table 1.

Regulatory Mechanisms of Syndecan Shedding

Syndecan shedding is regulated by a variety of extracellular stimuli including growth factors (116), inflammatory chemokines (33, 45), bacterial virulence factors (117, 118), heparanase (39), insulin (119), oxidative stress (120), and others (37). In all cases, the cleavage occurs through direct action of the extracellular proteases, sheddases. The exact mechanism on the extracellular stimuli that influence them to mediate shedding is still unknown.

Several growth factors like EGF, TGF-α, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin induce the release of SDCs-1 and -4 in a concentration dependent manner (116). A step further, thrombin receptor and EGF-mediated shedding is associated with the activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway (116, 120). Although, it is reported that protein kinase C (PKC) activation by the phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) induces SDC-1 shedding in myeloma cells and that its inhibition reverts this effect, PKC signaling cascade is not involved in EGF- and thrombin-mediated shedding (37, 121). Furthermore, FGF-2 is reported to enhance the shedding of SDC-1 in pancreatic carcinoma cells. The overexpression and activation of matrilysin MMP-7 in these cells has been related with the FGF-2 stimulatory effect on MMP-7 along with SDC-1 shedding (47, 122).

Another aspect of shedding regulation involves the heparanase, an endoglycosidase that degrades HS chains. Increased expression of heparanase is highlighted throughout the literature in a great number of tumor types, associated with angiogenic and metastatic potential of tumor cells (123). Upregulation of heparanase expression or exogenous addition of recombinant heparanase to myeloma cells stimulates SDC-1 expression and shedding (39, 124). Interestingly, it is reported that the HS chains of SDCs are able to coordinate the ectodomain cleavage. According to Ramani et al., the attached HS chains of SDCs may suppress the activity of heparanase and subsequent its shedding (125).

Intracellular regulatory mechanisms play also important roles in an agonist-induced shedding. Notably, SDC-1 cytoplasmic domain interacts with the inactive GDP-bound form of Rab5, a small GTPase that regulates intracellular trafficking. Rab5 triggers the conversion from the inactive GDP-bound to active GTP-bound state in response to shedding promoters. According to Hayashida et al., a dominant negative form of Rab5, without the ability to switch between active and inactive state, inhibited the SDC-1 proteolytic cleavage, stating that Rab5 is a critical regulator of SDC-1 shedding acting as an on–off molecular switch (126). It has been also reported that intracellular trafficking is actually a key regulator of SDC-1 shedding (126). Many growth factors are also involved in SDC-2 shedding, since treatment of microvascular epithelial cells with EGF, FGF-2, or VEGF induced this processing (71). It is also likely that SDC-1 shedding upregulates the SDC-2 synthesis affecting positively the proliferation of the cancer cells (127).

Functional Insights of Syndecan Shedding

The effects of SDCs shed ectodomain have been incriminated in several steps of cancer progression. Studies have pinpointed soluble SDC-1 ectodomain in the serum of lung cancer patients (59), Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients (49), and myeloma patients as well as within the ECM of the myeloma microenvironment (40, 41). In breast cancer, it is stated that the shed SDC-1 is derived largely from the host fibroblasts of the tumor microenvironment. To continue, based on studies in ARH-77 human lymphoblastoid cells, shed SDC-1 is established to promote tumor growth and progression in vivo, mediated by the crosstalk between tumor and host cells (57). Moreover, MT1-MMP-induced SDC-1 shedding inhibits cell migration in HEK293T cells (50) and cell proliferation in T47D breast carcinoma cells (52).

The significance of SDC shedding in malignancies is well documented in myeloma cells. As stated above, soluble SDC-1 is present at high levels in the serum of myeloma patients, promoting the growth of myeloma tumors in vivo. This observation renders shed SDC-1 as an indicator of poor prognosis in myeloma (38, 66, 123, 128). In addition, heparanase seems to play a distinct role in the shedding of SDCs in myeloma. It mediates shedding by cleaving the less sulfated regions along the HS chains creating fragments of 10–20 residues, promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis (129, 130). It is also documented that heparanase initiates the growth of myeloma cells and promotes bone metastasis by increasing the size of blood vessels within the tumor (37, 131–133). The basic idea is that the shed SDC-1 binds to growth factors derived from the tumor and concentrates them in the tumor microenvironment, promoting their signaling activity (Figure 1). On the other hand, upregulation of heparanase in the tumor microenvironment leads to elevated active levels of the intracellular effector ERK (p-ERK), and in turn increased expression of VEGF and MMP-9 (123). These effects are mediated not only from the high phosphorylation of ERK, but also due to the diminished levels of SDC-1 in the nucleus, leading to increased levels of acetylated histone H3 and eventually facilitating the transcription of VEGF and MMP-9 (100). As a result, MMP-9 cleaves SDC-1 from the cell surface and therefore interacts with growth factors like hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and VEGF, whose expression is already stimulated by heparanase (134). Then, the “loaded” with growth factors shed SDC-1 binds to ECM macromolecules, such as FN and collagen, rendering these growth factors available in the tumor microenvironment even in distal sites. As a consequence, shed SDC-1 mediates the signaling of bound growth factors leading to a strong downstream signaling to host cells, triggering the microenvironment to support aggressive tumor growth (57).

Another aspect of heparanase action involves its cooperation with SDC-1 that regulates the biogenesis and function of the exosomes. These lipid bilayer bound extracellular vesicles are very aggressive especially when they are secreted in high amounts in tumors. Their cargo including proteins, mRNA, and miRNA, are of outmost importance for intracellular communication within tumor and host cells (135, 136). In many cases, exosomes derived from tumor cells are reported to promote angiogenesis (137), metastasis (138, 139), and immune evasion (140). In addition, both heparanase and SDC-1 are retained as cargo within exosomes and subsequently influence not only the behavior of the tumor microenvironment within the tumor niche and distant sites, but also the growth of the metastasizing cells (Figure 1) (57).

Similar to SDC-1, there is evidence indicating that the shed ectodomains of SDC-2 and -4 increase angiogenesis. Studies have shown that recombinant shed SDC-2 is cleaved by the MMP-7 in colon cancer but the consequences of this effect are not yet determined (141). Moreover, secreted ADAMTS-1 cleaves the ectodomain of SDC-4, affecting cytoskeleton organization and adhesion, enhancing angiogenesis and migration (79).

Shed SDCs are also in position to eliminate the inhibitory soluble factors. Shed SDC-1 facilitates the resolution of neutrophilic inflammation by inducing the clearance of proinflammatory CXC cytokines. In other words, shed SDCs may promote cancer also by sequestrating inhibitory signals (142).

Importantly, the soluble SDC ectodomain may serve as new soluble effectors and even compete with intact cell membrane SDCs for extracellular ligands in the host microenvironment (37, 143). In addition, there are several studies indicating that shed SDCs might act as ligands to induce gene expression. In particular, shed SDC-1 expression is reported to regulate the expression of TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP-1), urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), and E-cadherin in breast cancer cells coordinating their invasiveness (53). Finally there are emerging evidence indicating that HSPG shedding can down-regulate HSPG-dependent functions by binding the appropriate HS ligands and making them accessible for internalization. Based on this observation, shed SDCs may actually have a role as extracellular chaperones that transfer ligands to cell surface HSPGs on neighboring cells based on the paracrine stimulation (144).

Finally, it is worth noticing that shed SDCs have also been reported to have anti-tumorigenic effects in several cases. To state, the membrane-bound SDC-1 promotes proliferation and inhibits invasiveness of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, whereas the soluble form has the exact opposite effect (53). Moreover shed SDC-1 inhibits alveolar epithelial wound healing, promotes fibrogenesis (145), and decreases invasion of TIMP-1-sensitive breast cancer cell invasion (53, 121).

Potential Syndecan-Based Pharmacological Approaches in Cancer Treatment

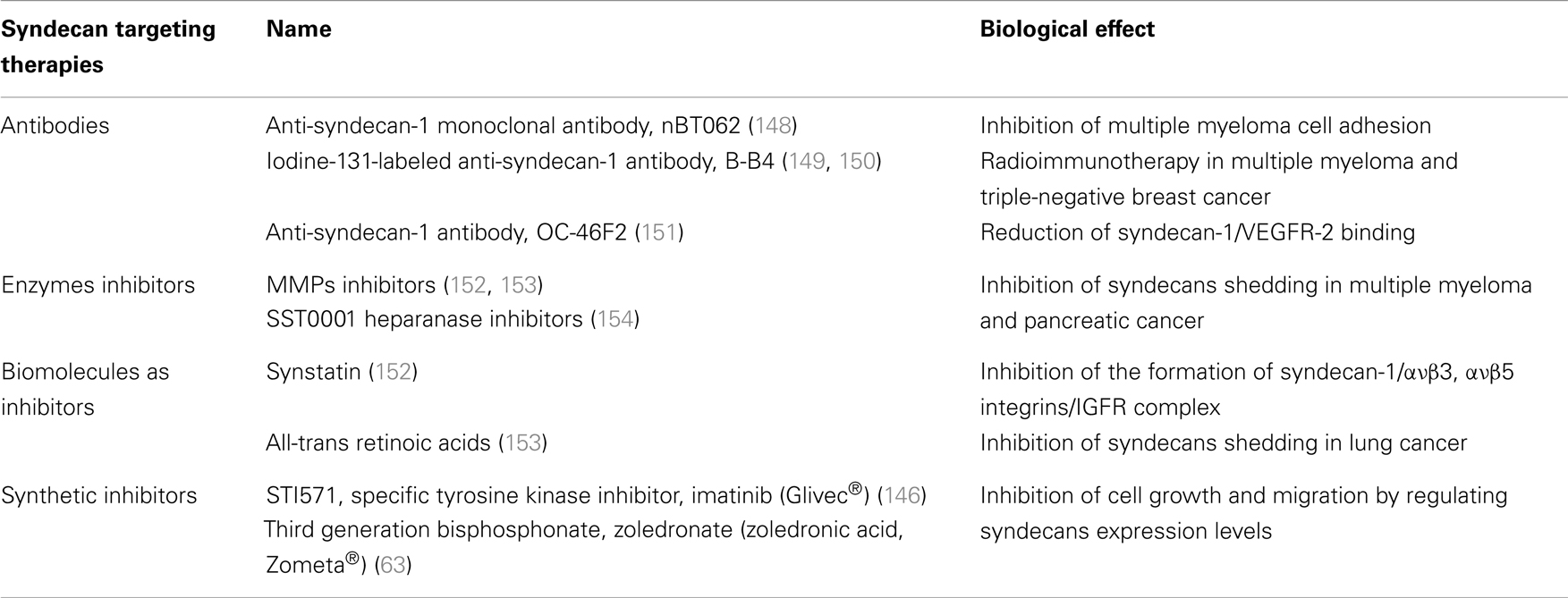

As the knowledge of HSPGs role on cancer progression and development is accumulating, the perspective to use SDCs in therapeutics is becoming more and more appealing. An overview of SDCs-based therapeutic targeting is summarized in Table 2. The treatment with already existed pharmaceutical formulations in several in vitro and in vivo biological systems, suggests that they can regulate the expression levels of SDCs, thus inhibiting their carcinogenic potential. According to that notion, the third generation bisphosphonate, zoledronate (zoledronic acid, Zometa®) is shown to down-regulate the expression levels of SDC-1 and -2, in contrast with the upregulation of SDC-4 in human breast cancer cells with different metastatic potentials (63). This effect is associated with the inhibition of cell growth, migration, adhesion, and invasion in correlation with the diminished levels of ανβ3, ανβ5, and α5β1 integrins (63). Similar mode of action has the specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Glivec®), which targets PDGFRs, c-Kit and Bcr-Abl. It exerts a significant inhibitory effect on the expression of SDCs-2 and -4 on PDGF-BB-treated breast cancer cells, leading to suppressed cell growth ability, migration, and invasion (146). Also, Nimesulide a worldwide known non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, with specific action on cyclooxygenase (COX-2) inhibits the expression of SDC-1 in primary effusion lymphoma and blocks its anti-tumorigenic action (147).

Recent studies focus on exploring therapeutically approaches that are associated with SDCs ectodomain. As a result monoclonal antibodies or peptides, which target specifically extracellular domain of SDCs, have been evaluated. OC-46F2, a fully human anti-SDC-1 recombinant antibody, reduces SDC-1/VEGFR-2 distribution in tumor microenvironment, resulting in suppressed vascular maturation and tumor growth in melanoma and ovarian experimental model (151). It has also been suggested that antibodies against SDCs, especially SDC-1 and -4, are able to inhibit the dynamic relations between SDCs and cytokines leading to potential treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (155, 156). To continue, a murine/human chimeric anti-SDC-1 monoclonal antibody, nBT062, conjugated with highly cytotoxic maytansinoid derivatives was introduced. The nBT062-maytansinoid conjugation was reported to drive targeted maytansinoid-induced cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma, blocking cell adhesion to bone marrow stromal cells. Moreover, these conjugations inhibit multiple myeloma tumor growth in vivo and prolong host survival in both xenograft mouse models of human multiple myeloma and SCID-hu mouse model (148). In addition, B-B4 (iodine-131-labeled anti-SDC-1 antibody) was administrated to myeloma patients with success, promoting the notion of targeted radioimmunotherapy (RIT) (149). Interestingly, recent studies indicate the importance of B-B4 antibody not only in multiple myeloma but also in triple-negative breast cancer in combination with immune-PET imaging and RIT (150). Another approach in SDC targeting involves the use of small peptides. For example, Synstatin was developed to the sequence between 82 and 130 amino acids of SDC-1 ectodomain. In detail, this peptide antagonizes SDC-1 domain, responsible for capturing and activating ανβ3 or ανβ5 integrins and IGF-IR. To note, Synstatin’s action prevents the formation of the receptor complex, and in turn blocks tumor-induced angiogenesis and metastasis mediated by the initial complex (152).

Considering the significant role of shed SDCs, their pharmacological potential was investigated in several studies targeting indirectly their actions. It is noted that myeloma and pancreatic chemotherapeutic drugs tend to induce accumulation of shed SDC-1 exactly as benzo(α)pyrene does in lung cancer. To avoid such tumor initiating effect, the use of metalloproteinase inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy and all-trans retinoic acid was suggested (153, 157). Another strategy to accomplish shedding inhibition involves the use of SST0001, a non-anticoagulant heparin with anti-heparanase activity, whose use diminishes the heparanase-induced SDC-1 shedding. In addition, the combination of SST0001 with dexamethasone, blocks tumor growth in vivo presumably through dual targeting of the tumor itself as well as its microenvironment (154). A recent study in multiple myeloma highlighted that targeting HS expression, through knockdown of EXT1, in combination with exposure to lenalidomide or bortezomib results in inhibition of cell growth (158).

Based on the ability of SDCs to act as endocytosis receptors, SDCs have been used for viral and non-viral scaffolds that deliver nucleic acids for gene therapy. Specifically, lipoplexes and nucleic acid polyplexes before entering into the cell bind on SDCs clusters in actin-rich plasma membrane extensions, and therefore are internalized driven by the action of the cytoskeleton retrograde flow (159). Polyethyleneimine (PEI)–DNA conjugates represent a drug delivery mechanism according to which SDC-1 is required for the successful gene transfer whereas SDC-2 inhibits this process (160).

Concluding Remarks

Syndecans represent an ongoing field of investigation, attempting to elucidate their regulatory roles in normal and pathological conditions. Multiple roles of SDCs in cancer progression are documented, implicating them in diagnosis, progression, and even the treatment of different types of cancer. The dynamic potential of these HSPGs is vast, considering their transmembrane localization, their ability to promote signal transduction through interactions with a plethora of ligands, the interplay between tumor and stroma cells and last but certainly not least their ability to be cleaved upon different stimulations. An overview of the major reported mediated effects of SDCs (transmembrane and shed) are depicted in Figure 1. These molecules have strong implications in cancer biology in membrane-bound state and also in their soluble state, it is a fact that SDCs can function in different ways, different stages of cancer, and to regulate tumorigenic mechanisms. The promising in vitro and in vivo results indicate the feasibility of targeting SDCs as a potential cancer treatment strategy. However, in order this concept to be shaped, further preclinical studies and well-designed clinical trials are necessary. Anticancer drugs will be probably produced through pharmacological targeting of shed SDCs in combination with agents responsible for inhibition of signal transduction and epigenetics. Taking into consideration the SDCs-mediated biological actions during early stage and progression of cancer, it is plausible to suggest that members of the SDCs family may be a potential tool for disease diagnosis and prognosis as well as candidates for designing novel therapeutic approaches against cancer progression.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci (2010) 123(Pt 24):4195–200. doi:10.1242/jcs.023820

2. Lu P, Takai K, Weaver VM, Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2011) 3(12):a005058. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a005058

3. Sappino AP, Schurch W, Gabbiani G. Differentiation repertoire of fibroblastic cells: expression of cytoskeletal proteins as marker of phenotypic modulations. Lab Invest (1990) 63(2):144–61.

4. Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumour-host interface. Nature (2001) 411(6835):375–9. doi:10.1038/35077241

5. Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J (2011) 278(1):16–27. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07919.x

6. Fidler IJ. Seed and soil revisited: contribution of the organ microenvironment to cancer metastasis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am (2001) 10(2):257–69.

7. Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res (1999) 59(19):5002–11.

8. Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK. Proteoglycans in health and disease: novel roles for proteoglycans in malignancy and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J (2010) 277(19):3904–23. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07800.x

9. Iozzo RV, Karamanos N. Proteoglycans in health and disease: emerging concepts and future directions. FEBS J (2010) 277(19):3863. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07796.x

10. Iozzo RV, Sanderson RD. Proteoglycans in cancer biology, tumour microenvironment and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med (2011) 15(5):1013–31. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01236.x

11. Kirkpatrick CA, Selleck SB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance. J Cell Sci (2007) 120(Pt 11):1829–32. doi:10.1242/jcs.03432

12. Dreyfuss JL, Regatieri CV, Jarrouge TR, Cavalheiro RP, Sampaio LO, Nader HB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans: structure, protein interactions and cell signaling. An Acad Bras Cienc (2009) 81(3):409–29. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652009000300007

13. Afratis N, Gialeli C, Nikitovic D, Tsegenidis T, Karousou E, Theocharis AD, et al. Glycosaminoglycans: key players in cancer cell biology and treatment. FEBS J (2012) 279(7):1177–97. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08529.x

14. Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2011) 3(7):a004952. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a004952

15. Couchman JR. Syndecans: proteoglycan regulators of cell-surface micro- domains? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2003) 4(12):926–37. doi:10.1038/nrm1257

16. Couchman JR. Transmembrane signaling proteoglycans. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (2010) 26:89–114. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104126

17. Yoneda A, Couchman JR. Regulation of cytoskeletal organization by syndecan transmembrane proteoglycans. Matrix Biol (2003) 22(1):25–33. doi:10.1016/S0945-053X(03)00010-6

18. Choi Y, Chung H, Jung H, Couchman JR, Oh ES. Syndecans as cell surface receptors: unique structure equates with functional diversity. Matrix Biol (2011) 30(2):93–9. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2010.10.006

19. Xian X, Gopal S, Couchman JR. Syndecans as receptors and organizers of the extracellular matrix. Cell Tissue Res (2010) 339(1):31–46. doi:10.1007/s00441-009-0829-3

20. Bellin R, Capila I, Lincecum J, Park PW, Reizes O, Bernfield MR. Unlocking the secrets of syndecans: transgenic organisms as a potential key. Glycoconj J (2002) 19(4–5):295–304. doi:10.1023/A:1025352501148

21. Ishiguro K, Kadomatsu K, Kojima T, Muramatsu H, Iwase M, Yoshikai Y, et al. Syndecan-4 deficiency leads to high mortality of lipopolysaccharide-injected mice. J Biol Chem (2001) 276(50):47483–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106268200

22. Kaksonen M, Pavlov I, Voikar V, Lauri SE, Hienola A, Riekki R, et al. Syndecan-3-deficient mice exhibit enhanced LTP and impaired hippocampus-dependent memory. Mol Cell Neurosci (2002) 21(1):158–72. doi:10.1006/mcne.2002.1167

23. Stepp MA, Gibson HE, Gala PH, Iglesia DD, Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Pal-Ghosh S, et al. Defects in keratinocyte activation during wound healing in the syndecan-1-deficient mouse. J Cell Sci (2002) 115(Pt 23):4517–31. doi:10.1242/jcs.00128

24. Pataki CCJ. Structure and function of syndecans. In: Karamanos N, editor. Extracellular Matrix Pathobiology and Signalilng. Berlin: De Gruyter (2012). p. 197–204.

25. Noguer O, Reina M. Is syndecan-2 a key angiogenic element? ScientificWorldJournal (2009) 9:729–32. doi:10.1100/tsw.2009.89

26. Noguer O, Villena J, Lorita J, Vilaro S, Reina M. Syndecan-2 downregulation impairs angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res (2009) 315(5):795–808. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.11.016

27. Bernfield M, Kokenyesi R, Kato M, Hinkes MT, Spring J, Gallo RL, et al. Biology of the syndecans: a family of transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Cell Biol (1992) 8:365–93. doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002053

28. Sanderson RD, Yang Y, Suva LJ, Kelly T. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans and heparanase – partners in osteolytic tumor growth and metastasis. Matrix Biol (2004) 23(6):341–52. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2004.08.004

29. Sanderson RD, Yang Y. Syndecan-1: a dynamic regulator of the myeloma microenvironment. Clin Exp Metastasis (2008) 25(2):149–59. doi:10.1007/s10585-007-9125-3

30. Soukka T, Pohjola J, Inki P, Happonen RP. Reduction of syndecan-1 expression is associated with dysplastic oral epithelium. J Oral Pathol Med (2000) 29(7):308–13. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290704.x

31. Inki P, Stenback F, Grenman S, Jalkanen M. Immunohistochemical localization of syndecan-1 in normal and pathological human uterine cervix. J Pathol (1994) 172(4):349–55. doi:10.1002/path.1711720410

32. Nakanishi K, Yoshioka N, Oka K, Hakura A. Reduction of syndecan-1 mRNA in cervical-carcinoma cells is involved with the 3’ untranslated region. Int J Cancer (1999) 80(4):527–32. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990209)80:4<527::AID-IJC8>3.3.CO;2-P

33. Brule S, Charnaux N, Sutton A, Ledoux D, Chaigneau T, Saffar L, et al. The shedding of syndecan-4 and syndecan-1 from HeLa cells and human primary macrophages is accelerated by SDF-1/CXCL12 and mediated by the matrix metalloproteinase-9. Glycobiology (2006) 16(6):488–501. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwj098

34. Hinkes MT, Goldberger OA, Neumann PE, Kokenyesi R, Bernfield M. Organization and promoter activity of the mouse syndecan-1 gene. J Biol Chem (1993) 268(15):11440–8.

35. Anttonen A, Kajanti M, Heikkila P, Jalkanen M, Joensuu H. Syndecan-1 expression has prognostic significance in head and neck carcinoma. Br J Cancer (1999) 79(3–4):558–64. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6690088

36. Nackaerts K, Verbeken E, Deneffe G, Vanderschueren B, Demedts M, David G. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan expression in human lung-cancer cells. Int J Cancer (1997) 74(3):335–45. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970620)74:3<335::AID-IJC18>3.0.CO;2-A

37. Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J (2010) 277(19):3876–89. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07798.x

38. Yang Y, Yaccoby S, Liu W, Langford JK, Pumphrey CY, Theus A, et al. Soluble syndecan-1 promotes growth of myeloma tumors in vivo. Blood (2002) 100(2):610–7. doi:10.1182/blood.V100.2.610

39. Yang Y, Macleod V, Miao HQ, Theus A, Zhan F, Shaughnessy JD Jr, et al. Heparanase enhances syndecan-1 shedding: a novel mechanism for stimulation of tumor growth and metastasis. J Biol Chem (2007) 282(18):13326–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M611259200

40. Bayer-Garner IB, Sanderson RD, Dhodapkar MV, Owens RB, Wilson CS. Syndecan-1 (CD138) immunoreactivity in bone marrow biopsies of multiple myeloma: shed syndecan-1 accumulates in fibrotic regions. Mod Pathol (2001) 14(10):1052–8. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880435

41. Lovell R, Dunn JA, Begum G, Barth NJ, Plant T, Moss PA, et al. Soluble syndecan-1 level at diagnosis is an independent prognostic factor in multiple myeloma and the extent of fall from diagnosis to plateau predicts for overall survival. Br J Haematol (2005) 130(4):542–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05647.x

42. Stanley MJ, Stanley MW, Sanderson RD, Zera R. Syndecan-1 expression is induced in the stroma of infiltrating breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol (1999) 112(3):377–83.

43. Su G, Blaine SA, Qiao D, Friedl A. Shedding of syndecan-1 by stromal fibroblasts stimulates human breast cancer cell proliferation via FGF2 activation. J Biol Chem (2007) 282(20):14906–15. doi:10.1074/jbc.M611739200

44. Maeda T, Alexander CM, Friedl A. Induction of syndecan-1 expression in stromal fibroblasts promotes proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res (2004) 64(2):612–21. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2439

45. Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL, Parks WC. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell (2002) 111(5):635–46. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01079-6

46. Klatka J. Syndecan-1 expression in laryngeal cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2002) 259(3):115–8. doi:10.1007/s00405-001-0429-7

47. Ding K, Lopez-Burks M, Sanchez-Duran JA, Korc M, Lander AD. Growth factor-induced shedding of syndecan-1 confers glypican-1 dependence on mitogenic responses of cancer cells. J Cell Biol (2005) 171(4):729–38. doi:10.1083/jcb.200508010

48. Kumar-Singh S, Jacobs W, Dhaene K, Weyn B, Bogers J, Weyler J, et al. Syndecan-1 expression in malignant mesothelioma: correlation with cell differentiation, WT1 expression, and clinical outcome. J Pathol (1998) 186(3):300–5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(1998110)186:3<300::AID-PATH180>3.0.CO;2-Q

49. Vassilakopoulos TP, Kyrtsonis MC, Papadogiannis A, Nadali G, Angelopoulou MK, Tzenou T, et al. Serum levels of soluble syndecan-1 in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Anticancer Res (2005) 25(6C):4743–6.

50. Endo K, Takino T, Miyamori H, Kinsen H, Yoshizaki T, Furukawa M, et al. Cleavage of syndecan-1 by membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 stimulates cell migration. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(42):40764–70. doi:10.1074/jbc.M306736200

51. Sanderson RD, Borset M. Syndecan-1 in B lymphoid malignancies. Ann Hematol (2002) 81(3):125–35. doi:10.1007/s00277-002-0437-8

52. Su G, Blaine SA, Qiao D, Friedl A. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase-mediated stromal syndecan-1 shedding stimulates breast carcinoma cell proliferation. Cancer Res (2008) 68(22):9558–65. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1645

53. Nikolova V, Koo CY, Ibrahim SA, Wang Z, Spillmann D, Dreier R, et al. Differential roles for membrane-bound and soluble syndecan-1 (CD138) in breast cancer progression. Carcinogenesis (2009) 30(3):397–407. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgp001

54. Pruessmeyer J, Martin C, Hess FM, Schwarz N, Schmidt S, Kogel T, et al. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17) mediates inflammation-induced shedding of syndecan-1 and -4 by lung epithelial cells. J Biol Chem (2010) 285(1):555–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.059394

55. Matsumoto A, Ono M, Fujimoto Y, Gallo RL, Bernfield M, Kohgo Y. Reduced expression of syndecan-1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma with high metastatic potential. Int J Cancer (1997) 74(5):482–91. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971021)74:5<482::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-#

56. Levy P, Munier A, Baron-Delage S, Di Gioia Y, Gespach C, Capeau J, et al. Syndecan-1 alterations during the tumorigenic progression of human colonic Caco-2 cells induced by human Ha-ras or polyoma middle T oncogenes. Br J Cancer (1996) 74(3):423–31. doi:10.1038/bjc.1996.376

57. Ramani VC, Purushothaman A, Stewart MD, Thompson CA, Vlodavsky I, Au JL, et al. The heparanase/syndecan-1 axis in cancer: mechanisms and therapies. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2294–306. doi:10.1111/febs.12168

58. Viklund L, Vorontsova N, Henttinen T, Salmivirta M. Syndecan-1 regulates FGF8b responses in S115 mammary carcinoma cells. Growth Factors (2006) 24(2):151–7. doi:10.1080/08977190600699426

59. Joensuu H, Anttonen A, Eriksson M, Makitaro R, Alfthan H, Kinnula V, et al. Soluble syndecan-1 and serum basic fibroblast growth factor are new prognostic factors in lung cancer. Cancer Res (2002) 62(18):5210–7.

60. Matsuzaki H, Kobayashi H, Yagyu T, Wakahara K, Kondo T, Kurita N, et al. Reduced syndecan-1 expression stimulates heparin-binding growth factor-mediated invasion in ovarian cancer cells in a urokinase-independent mechanism. Oncol Rep (2005) 14(2):449–57.

61. Maeda T, Desouky J, Friedl A. Syndecan-1 expression by stromal fibroblasts promotes breast carcinoma growth in vivo and stimulates tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene (2006) 25(9):1408–12. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209168

62. Burbach BJ, Friedl A, Mundhenke C, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 accumulates in lysosomes of poorly differentiated breast carcinoma cells. Matrix Biol (2003) 22(2):163–77. doi:10.1016/S0945-053X(03)00009-X

63. Dedes PG, Gialeli C, Tsonis AI, Kanakis I, Theocharis AD, Kletsas D, et al. Expression of matrix macromolecules and functional properties of breast cancer cells are modulated by the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta (2012) 1820(12):1926–39. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.07.013

64. Conejo JR, Kleeff J, Koliopanos A, Matsuda K, Zhu ZW, Goecke H, et al. Syndecan-1 expression is up-regulated in pancreatic but not in other gastrointestinal cancers. Int J Cancer (2000) 88(1):12–20. doi:10.1002/1097-0215(20001001)88:1<12::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-T

65. Wiksten JP, Lundin J, Nordling S, Lundin M, Kokkola A, von Boguslawski K, et al. Epithelial and stromal syndecan-1 expression as predictor of outcome in patients with gastric cancer. Int J Cancer (2001) 95(1):1–6. doi:10.1002/1097-0215(20010120)95:1<1::AID-IJC1000>3.0.CO;2-5

66. Seidel C, Sundan A, Hjorth M, Turesson I, Dahl IM, Abildgaard N, et al. Serum syndecan-1: a new independent prognostic marker in multiple myeloma. Blood (2000) 95(2):388–92.

67. Sebestyen A, Berczi L, Mihalik R, Paku S, Matolcsy A, Kopper L. Syndecan-1 (CD138) expression in human non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Br J Haematol (1999) 104(2):412–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01211.x

68. Roh YH, Kim YH, Choi HJ, Lee KE, Roh MS. Fascin overexpression correlates with positive thrombospondin-1 and syndecan-1 expressions and a more aggressive clinical course in patients with gallbladder cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg (2009) 16(3):315–21. doi:10.1007/s00534-009-0046-1

69. Lee JH, Park H, Chung H, Choi S, Kim Y, Yoo H, et al. Syndecan-2 regulates the migratory potential of melanoma cells. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(40):27167–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.034678

70. Choi S, Kim JY, Park JH, Lee ST, Han IO, Oh ES. The matrix metalloproteinase-7 regulates the extracellular shedding of syndecan-2 from colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2012) 417(4):1260–4. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.120

71. Fears CY, Gladson CL, Woods A. Syndecan-2 is expressed in the microvasculature of gliomas and regulates angiogenic processes in microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem (2006) 281(21):14533–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.C600075200

72. Park H, Kim Y, Lim Y, Han I, Oh ES. Syndecan-2 mediates adhesion and proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem (2002) 277(33):29730–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202435200

73. Hrabar D, Aralica G, Gomercic M, Ljubicic N, Kruslin B, Tomas D. Epithelial and stromal expression of syndecan-2 in pancreatic carcinoma. Anticancer Res (2010) 30(7):2749–53.

74. Popovic A, Demirovic A, Spajic B, Stimac G, Kruslin B, Tomas D. Expression and prognostic role of syndecan-2 in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis (2010) 13(1):78–82. doi:10.1038/pcan.2009.43

75. Munesue S, Kusano Y, Oguri K, Itano N, Yoshitomi Y, Nakanishi H, et al. The role of syndecan-2 in regulation of actin-cytoskeletal organization of Lewis lung carcinoma-derived metastatic clones. Biochem J (2002) 363(Pt 2):201–9. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3630201

76. Huang X, Xiao DW, Xu LY, Zhong HJ, Liao LD, Xie ZF, et al. Prognostic significance of altered expression of SDC2 and CYR61 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep (2009) 21(4):1123–9.

77. Beauvais DM, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1-mediated cell spreading requires signaling by alphavbeta3 integrins in human breast carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res (2003) 286(2):219–32. doi:10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00126-5

78. O’Connell MP, Fiori JL, Kershner EK, Frank BP, Indig FE, Taub DD, et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan modulation of Wnt5A signal transduction in metastatic melanoma cells. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(42):28704–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.028498

79. Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Carpizo D, Plaza-Calonge Mdel C, Torres-Collado AX, Thai SN, Simons M, et al. Cleavage of syndecan-4 by ADAMTS1 provokes defects in adhesion. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2009) 41(4):800–10. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.014

80. Nord H, Segersten U, Sandgren J, Wester K, Busch C, Menzel U, et al. Focal amplifications are associated with high grade and recurrences in stage Ta bladder carcinoma. Int J Cancer (2010) 126(6):1390–402. doi:10.1002/ijc.24954

81. Na KY, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, Kim YW, Park YK. Syndecan-4 and fibronectin in osteosarcoma. Pathology (2012) 44(4):325–30. doi:10.1097/PAT.0b013e328353447b

82. Schmidt A, Echtermeyer F, Alozie A, Brands K, Buddecke E. Plasmin- and thrombin-accelerated shedding of syndecan-4 ectodomain generates cleavage sites at Lys(114)-Arg(115) and Lys(129)-Val(130) bonds. J Biol Chem (2005) 280(41):34441–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501903200

83. Saito Y, Owaki T, Matsunaga T, Saze M, Miura S, Maeda M, et al. Apoptotic death of hematopoietic tumor cells through potentiated and sustained adhesion to fibronectin via VLA-4. J Biol Chem (2010) 285(10):7006–15. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.027581

84. Jayson GC, Vives C, Paraskeva C, Schofield K, Coutts J, Fleetwood A, et al. Coordinated modulation of the fibroblast growth factor dual receptor mechanism during transformation from human colon adenoma to carcinoma. Int J Cancer (1999) 82(2):298–304. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990719)82:2<298::AID-IJC23>3.3.CO;2-0

85. Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Kletsas D, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK. Expression of matrix macromolecules and functional properties of EGF-responsive colon cancer cells are inhibited by panitumumab. Invest New Drugs (2012) 31(3):516–24. doi:10.1007/s10637-012-9875-x

86. Labropoulou VT, Skandalis SS, Ravazoula P, Perimenis P, Karamanos NK, Kalofonos HP, et al. Expression of syndecan-4 and correlation with metastatic potential in testicular germ cell tumours. Biomed Res Int (2013) 2013:214864. doi:10.1155/2013/214864

87. Vicente CM, Ricci R, Nader HB, Toma L. Syndecan-2 is upregulated in colorectal cancer cells through interactions with extracellular matrix produced by stromal fibroblasts. BMC Cell Biol (2013) 14:25. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-14-25

88. Huang W, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Moyano JV, Garcia-Pardo A, Orend G. Interference of tenascin-C with syndecan-4 binding to fibronectin blocks cell adhesion and stimulates tumor cell proliferation. Cancer Res (2001) 61(23):8586–94.

89. Vuoriluoto K, Hognas G, Meller P, Lehti K, Ivaska J. Syndecan-1 and -4 differentially regulate oncogenic K-ras dependent cell invasion into collagen through alpha2beta1 integrin and MT1-MMP. Matrix Biol (2011) 30(3):207–17. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2011.03.003

90. Ishikawa T, Kramer RH. Sdc1 negatively modulates carcinoma cell motility and invasion. Exp Cell Res (2010) 316(6):951–65. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.12.013

91. Isenberg JS, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1: a physiological regulator of nitric oxide signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci (2008) 65(5):728–42. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7488-x

92. Naganuma H, Satoh E, Asahara T, Amagasaki K, Watanabe A, Satoh H, et al. Quantification of thrombospondin-1 secretion and expression of alphavbeta3 and alpha3beta1 integrins and syndecan-1 as cell-surface receptors for thrombospondin-1 in malignant glioma cells. J Neurooncol (2004) 70(3):309–17. doi:10.1007/s11060-004-9167-1

93. Watanabe A, Mabuchi T, Satoh E, Furuya K, Zhang L, Maeda S, et al. Expression of syndecans, a heparan sulfate proteoglycan, in malignant gliomas: participation of nuclear factor-kappaB in upregulation of syndecan-1 expression. J Neurooncol (2006) 77(1):25–32. doi:10.1007/s11060-005-9010-3

94. Mundhenke C, Meyer K, Drew S, Friedl A. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans as regulators of fibroblast growth factor-2 receptor binding in breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol (2002) 160(1):185–94. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64362-3

95. Zong F, Fthenou E, Wolmer N, Hollosi P, Kovalszky I, Szilak L, et al. Syndecan-1 and FGF-2, but not FGF receptor-1, share a common transport route and co-localize with heparanase in the nuclei of mesenchymal tumor cells. PLoS One (2009) 4(10):e7346. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007346

96. Wu X, Kan M, Wang F, Jin C, Yu C, McKeehan WL. A rare premalignant prostate tumor epithelial cell syndecan-1 forms a fibroblast growth factor-binding complex with progression-promoting ectopic fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Cancer Res (2001) 61(13):5295–302.

97. Nikitovic D, Assouti M, Sifaki M, Katonis P, Krasagakis K, Karamanos NK, et al. Chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate-containing proteoglycans are both partners and targets of basic fibroblast growth factor-mediated proliferation in human metastatic melanoma cell lines. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2008) 40(1):72–83. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.019

98. Grunewald FS, Prota AE, Giese A, Ballmer-Hofer K. Structure-function analysis of VEGF receptor activation and the role of coreceptors in angiogenic signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta (2010) 1804(3):567–80. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.002

99. Lamorte S, Ferrero S, Aschero S, Monitillo L, Bussolati B, Omede P, et al. Syndecan-1 promotes the angiogenic phenotype of multiple myeloma endothelial cells. Leukemia (2012) 26(5):1081–90. doi:10.1038/leu.2011.290

100. Purushothaman A, Hurst DR, Pisano C, Mizumoto S, Sugahara K, Sanderson RD. Heparanase-mediated loss of nuclear syndecan-1 enhances histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity to promote expression of genes that drive an aggressive tumor phenotype. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(35):30377–83. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.254789

101. Beauvais DM, Burbach BJ, Rapraeger AC. The syndecan-1 ectodomain regulates alphavbeta3 integrin activity in human mammary carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol (2004) 167(1):171–81. doi:10.1083/jcb.200404171

102. Beauvais DM, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 couples the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor to inside-out integrin activation. J Cell Sci (2010) 123(Pt 21):3796–807. doi:10.1242/jcs.067645

103. McQuade KJ, Beauvais DM, Burbach BJ, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 regulates alphavbeta5 integrin activity in B82L fibroblasts. J Cell Sci (2006) 119(Pt 12):2445–56. doi:10.1242/jcs.02970

104. Rapraeger AC, Ell BJ, Roy M, Li X, Morrison OR, Thomas GM, et al. Vascular endothelial-cadherin stimulates syndecan-1-coupled insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and cross-talk between alphaVbeta3 integrin and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 at the onset of endothelial cell dissemination during angiogenesis. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2194–206. doi:10.1111/febs.12134

105. Dobra K, Andang M, Syrokou A, Karamanos NK, Hjerpe A. Differentiation of mesothelioma cells is influenced by the expression of proteoglycans. Exp Cell Res (2000) 258(1):12–22. doi:10.1006/excr.2000.4915

106. Shah L, Walter KL, Borczuk AC, Kawut SM, Sonett JR, Gorenstein LA, et al. Expression of syndecan-1 and expression of epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with survival in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer (2004) 101(7):1632–8. doi:10.1002/cncr.20542

107. Mahtouk K, Cremer FW, Reme T, Jourdan M, Baudard M, Moreaux J, et al. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans are essential for the myeloma cell growth activity of EGF-family ligands in multiple myeloma. Oncogene (2006) 25(54):7180–91. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209699

108. Tsonis AI, Afratis N, Gialeli C, Ellina MI, Piperigkou Z, Skandalis SS, et al. Evaluation of the coordinated actions of estrogen receptors with epidermal growth factor receptor and insulin-like growth factor receptor in the expression of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans and cell motility in breast cancer cells. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2248–59. doi:10.1111/febs.12162

109. Lin F, Ren XD, Doris G, Clark RA. Three-dimensional migration of human adult dermal fibroblasts from collagen lattices into fibrin/fibronectin gels requires syndecan-4 proteoglycan. J Invest Dermatol (2005) 124(5):906–13. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23740.x

110. Lange K, Kammerer M, Saupe F, Hegi ME, Grotegut S, Fluri E, et al. Combined lysophosphatidic acid/platelet-derived growth factor signaling triggers glioma cell migration in a tenascin-C microenvironment. Cancer Res (2008) 68(17):6942–52. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0347

111. Chen L, Klass C, Woods A. Syndecan-2 regulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(16):15715–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300430200

112. Mytilinaiou M, Bano A, Nikitovic D, Berdiaki A, Voudouri K, Kalogeraki A, et al. Syndecan-2 is a key regulator of transforming growth factor beta 2/Smad2-mediated adhesion in fibrosarcoma cells. IUBMB Life (2013) 65(2):134–43. doi:10.1002/iub.1112

113. Yang N, Mosher R, Seo S, Beebe D, Friedl A. Syndecan-1 in breast cancer stroma fibroblasts regulates extracellular matrix fiber organization and carcinoma cell motility. Am J Pathol (2011) 178(1):325–35. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.039

114. Kim CW, Goldberger OA, Gallo RL, Bernfield M. Members of the syndecan family of heparan sulfate proteoglycans are expressed in distinct cell-, tissue-, and development-specific patterns. Mol Biol Cell (1994) 5(7):797–805. doi:10.1091/mbc.5.7.797

115. Curran S, Dundas SR, Buxton J, Leeman MF, Ramsay R, Murray GI. Matrix metalloproteinase/tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase phenotype identifies poor prognosis colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res (2004) 10(24):8229–34. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0424

116. Subramanian SV, Fitzgerald ML, Bernfield M. Regulated shedding of syndecan-1 and -4 ectodomains by thrombin and growth factor receptor activation. J Biol Chem (1997) 272(23):14713–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.23.14713

117. Chen Y, Hayashida A, Bennett AE, Hollingshead SK, Park PW. Streptococcus pneumoniae sheds syndecan-1 ectodomains through ZmpC, a metalloproteinase virulence factor. J Biol Chem (2007) 282(1):159–67. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608542200

118. Park PW, Foster TJ, Nishi E, Duncan SJ, Klagsbrun M, Chen Y. Activation of syndecan-1 ectodomain shedding by Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin and beta-toxin. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(1):251–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308537200

119. Wang JB, Guan J, Shen J, Zhou L, Zhang YJ, Si YF, et al. Insulin increases shedding of syndecan-1 in the serum of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2009) 86(2):83–8. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2009.08.002

120. Fitzgerald ML, Wang Z, Park PW, Murphy G, Bernfield M. Shedding of syndecan-1 and -4 ectodomains is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and mediated by a TIMP-3-sensitive metalloproteinase. J Cell Biol (2000) 148(4):811–24. doi:10.1083/jcb.148.4.811

121. Choi S, Lee H, Choi JR, Oh ES. Shedding; towards a new paradigm of syndecan function in cancer. BMB Rep (2010) 43(5):305–10. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.5.305

122. Wang F, Reierstad S, Fishman DA. Matrilysin over-expression in MCF-7 cells enhances cellular invasiveness and pro-gelatinase activation. Cancer Lett (2006) 236(2):292–301. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2005.05.042

123. Purushothaman A, Uyama T, Kobayashi F, Yamada S, Sugahara K, Rapraeger AC, et al. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 by myeloma cells promotes endothelial invasion and angiogenesis. Blood (2010) 115(12):2449–57. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-07-234757

124. Mahtouk K, Hose D, Raynaud P, Hundemer M, Jourdan M, Jourdan E, et al. Heparanase influences expression and shedding of syndecan-1, and its expression by the bone marrow environment is a bad prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Blood (2007) 109(11):4914–23. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-043232

125. Ramani VC, Pruett PS, Thompson CA, DeLucas LD, Sanderson RD. Heparan sulfate chains of syndecan-1 regulate ectodomain shedding. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(13):9952–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.330803

126. Hayashida K, Stahl PD, Park PW. Syndecan-1 ectodomain shedding is regulated by the small GTPase Rab5. J Biol Chem (2008) 283(51):35435–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M804172200

127. Peterfia B, Fule T, Baghy K, Szabadkai K, Fullar A, Dobos K, et al. Syndecan-1 enhances proliferation, migration and metastasis of HT-1080 cells in cooperation with syndecan-2. PLoS One (2012) 7(6):e39474. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039474

128. Khotskaya YB, Dai Y, Ritchie JP, MacLeod V, Yang Y, Zinn K, et al. Syndecan-1 is required for robust growth, vascularization, and metastasis of myeloma tumors in vivo. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(38):26085–95. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.018473

129. Kato M, Wang H, Kainulainen V, Fitzgerald ML, Ledbetter S, Ornitz DM, et al. Physiological degradation converts the soluble syndecan-1 ectodomain from an inhibitor to a potent activator of FGF-2. Nat Med (1998) 4(6):691–7. doi:10.1038/nm0698-691

130. Meirovitz A, Goldberg R, Binder A, Rubinstein AM, Hermano E, Elkin M. Heparanase in inflammation and inflammation-associated cancer. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2307–19. doi:10.1111/febs.12184

131. Ilan N, Elkin M, Vlodavsky I. Regulation, function and clinical significance of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2006) 38(12):2018–39. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.06.004

132. Yang Y, Macleod V, Bendre M, Huang Y, Theus AM, Miao HQ, et al. Heparanase promotes the spontaneous metastasis of myeloma cells to bone. Blood (2005) 105(3):1303–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-06-2141

133. Kelly T, Miao HQ, Yang Y, Navarro E, Kussie P, Huang Y, et al. High heparanase activity in multiple myeloma is associated with elevated microvessel density. Cancer Res (2003) 63(24):8749–56.

134. Ramani VC, Yang Y, Ren Y, Nan L, Sanderson RD. Heparanase plays a dual role in driving hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) signaling by enhancing HGF expression and activity. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(8):6490–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.183277

135. Record M, Subra C, Silvente-Poirot S, Poirot M. Exosomes as intercellular signalosomes and pharmacological effectors. Biochem Pharmacol (2011) 81(10):1171–82. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2011.02.011

136. Ge R, Tan E, Sharghi-Namini S, Asada HH. Exosomes in cancer microenvironment and beyond: have we overlooked these extracellular messengers? Cancer Microenviron (2012) 5(3):323–32. doi:10.1007/s12307-012-0110-2

137. Janowska-Wieczorek A, Wysoczynski M, Kijowski J, Marquez-Curtis L, Machalinski B, Ratajczak J, et al. Microvesicles derived from activated platelets induce metastasis and angiogenesis in lung cancer. Int J Cancer (2005) 113(5):752–60. doi:10.1002/ijc.20657

138. Peinado H, Lavotshkin S, Lyden D. The secreted factors responsible for pre-metastatic niche formation: old sayings and new thoughts. Semin Cancer Biol (2011) 21(2):139–46. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002

139. Peinado H, Aleckovic M, Lavotshkin S, Matei I, Costa-Silva B, Moreno-Bueno G, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med (2012) 18(6):883–91. doi:10.1038/nm.2753

140. Bobrie A, Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Exosome secretion: molecular mechanisms and roles in immune responses. Traffic (2011) 12(12):1659–68. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01225.x

141. Ryu HY, Lee J, Yang S, Park H, Choi S, Jung KC, et al. Syndecan-2 functions as a docking receptor for pro-matrix metalloproteinase-7 in human colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(51):35692–701. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.054254

142. Hayashida K, Parks WC, Park PW. Syndecan-1 shedding facilitates the resolution of neutrophilic inflammation by removing sequestered CXC chemokines. Blood (2009) 114(14):3033–43. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-02-204966

143. Steinfeld R, van den Berghe H, David G. Stimulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 occupancy and signaling by cell surface-associated syndecans and glypican. J Cell Biol (1996) 133(2):405–16. doi:10.1083/jcb.133.2.405

144. Christianson HC, Belting M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan as a cell-surface endocytosis receptor. Matrix Biol (2013). doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2013.10.004

145. Kliment CR, Englert JM, Gochuico BR, Yu G, Kaminski N, Rosas I, et al. Oxidative stress alters syndecan-1 distribution in lungs with pulmonary fibrosis. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(6):3537–45. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807001200

146. Malavaki CJ, Roussidis AE, Gialeli C, Kletsas D, Tsegenidis T, Theocharis AD, et al. Imatinib as a key inhibitor of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor mediated expression of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans and functional properties of breast cancer cells. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2477–89. doi:10.1111/febs.12163

147. Paul AG, Sharma-Walia N, Chandran B. Targeting KSHV/HHV-8 latency with COX-2 selective inhibitor nimesulide: a potential chemotherapeutic modality for primary effusion lymphoma. PLoS One (2011) 6(9):e24379. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024379

148. Ikeda H, Hideshima T, Fulciniti M, Lutz RJ, Yasui H, Okawa Y, et al. The monoclonal antibody nBT062 conjugated to cytotoxic Maytansinoids has selective cytotoxicity against CD138-positive multiple myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15(12):4028–37. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2867

149. Rousseau C, Ferrer L, Supiot S, Bardies M, Davodeau F, Faivre-Chauvet A, et al. Dosimetry results suggest feasibility of radioimmunotherapy using anti-CD138 (B-B4) antibody in multiple myeloma patients. Tumour Biol (2012) 33(3):679–88. doi:10.1007/s13277-012-0362-y

150. Rousseau C, Ruellan AL, Bernardeau K, Kraeber-Bodere F, Gouard S, Loussouarn D, et al. Syndecan-1 antigen, a promising new target for triple-negative breast cancer immuno-PET and radioimmunotherapy. A preclinical study on MDA-MB-468 xenograft tumors. EJNMMI Res (2011) 1(1):20. doi:10.1186/2191-219X-1-20

151. Orecchia P, Conte R, Balza E, Petretto A, Mauri P, Mingari MC, et al. A novel human anti-syndecan-1 antibody inhibits vascular maturation and tumour growth in melanoma. Eur J Cancer (2013) 49(8):2022–33. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.019

152. Rapraeger AC. Synstatin: a selective inhibitor of the syndecan-1-coupled IGF1R-alphavbeta3 integrin complex in tumorigenesis and angiogenesis. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2207–15. doi:10.1111/febs.12160

153. Ramya D, Siddikuzzaman, Grace VM. Effect of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) on syndecan-1 expression and its chemoprotective effect in benzo(alpha)pyrene-induced lung cancer mice model. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol (2012) 34(6):1020–7. doi:10.3109/08923973.2012.693086

154. Ritchie JP, Ramani VC, Ren Y, Naggi A, Torri G, Casu B, et al. SST0001, a chemically modified heparin, inhibits myeloma growth and angiogenesis via disruption of the heparanase/syndecan-1 axis. Clin Cancer Res (2011) 17(6):1382–93. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2476

155. Charni F, Friand V, Haddad O, Hlawaty H, Martin L, Vassy R, et al. Syndecan-1 and syndecan-4 are involved in RANTES/CCL5-induced migration and invasion of human hepatoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta (2009) 1790(10):1314–26. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.015

156. Dagouassat M, Suffee N, Hlawaty H, Haddad O, Charni F, Laguillier C, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CCL2 secreted by hepatic myofibroblasts promotes migration and invasion of human hepatoma cells. Int J Cancer (2010) 126(5):1095–108. doi:10.1002/ijc.24800

157. Ramani VC, Sanderson RD. Chemotherapy stimulates syndecan-1 shedding: a potentially negative effect of treatment that may promote tumor relapse. Matrix Biol (2013). doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2013.10.005

158. Reijmers RM, Spaargaren M, Pals ST. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the control of B cell development and the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. FEBS J (2013) 280(10):2180–93. doi:10.1111/febs.12180

159. ur Rehman Z, Sjollema KA, Kuipers J, Hoekstra D, Zuhorn IS. Nonviral gene delivery vectors use syndecan-dependent transport mechanisms in filopodia to reach the cell surface. ACS Nano (2012) 6(8):7521–32. doi:10.1021/nn3028562

Keywords: proteoglycans, syndecans, shed syndecans, heparan sulfate, cancer, tumor microenvironment, pharmacological targeting

Citation: Barbouri D, Afratis N, Gialeli C, Vynios DH, Theocharis AD and Karamanos NK (2014) Syndecans as modulators and potential pharmacological targets in cancer progression. Front. Oncol. 4:4. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00004

Received: 31 October 2013; Accepted: 09 January 2014;

Published online: 03 February 2014.

Edited by:

Elvira V. Grigorieva, Institute of Molecular Biology and Biophysics SB RAMS, RussiaReviewed by:

Martin Götte, Münster University Hospital, GermanyLeny Toma, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil

Copyright: © 2014 Barbouri, Afratis, Gialeli, Vynios, Theocharis and Karamanos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nikos K. Karamanos, Biochemistry, Biochemical Analysis and Matrix Pathobiology Research Group, Laboratory of Biochemistry, Department of Chemistry, University of Patras, 261 10 Patras, Greece e-mail:bi5rLmthcmFtYW5vc0B1cGF0cmFzLmdy

Despoina Barbouri

Despoina Barbouri Nikolaos Afratis

Nikolaos Afratis Chrisostomi Gialeli

Chrisostomi Gialeli Demitrios H. Vynios

Demitrios H. Vynios Achilleas D. Theocharis

Achilleas D. Theocharis Nikos K. Karamanos

Nikos K. Karamanos