- Service de NeuroImagerie, Centre Hospitalier National d’Ophtalmologie des 15-20, Paris, France

Anatomical tracing, human clinical data, and stimulation functional imaging have firmly established the major role of the (neo-)cerebellum in cognition and emotion. Telencephalization characterized by the great expansion of associative cortices, especially the prefrontal one, has been associated with parallel expansion of the neocerebellar cortex, especially the lobule VII, and by an increased number of interconnections between these two cortical structures. These anatomical modifications underlie the implication of the neocerebellum in cognitive control of complex motor and non-motor tasks. In humans, resting state functional connectivity has been used to determine a thorough anatomo-functional parcellation of the neocerebellum. This technique has identified central networks involving the neocerebellum and subserving its cognitive function. Neocerebellum participates in all intrinsic connected networks such as central executive, default mode, salience, dorsal and ventral attentional, and language-dedicated networks. The central executive network constitutes the main circuit represented within the neocerebellar cortex. Cerebellar zones devoted to these intrinsic networks appear multiple, interdigitated, and spatially ordered in three gradients. Such complex neocerebellar organization enables the neocerebellum to monitor and synchronize the main networks involved in cognition and emotion, likely by computing internal models.

Introduction

The cerebellum has been classically involved in sensorimotor planning, execution, control, automation, and learning. However, in the last 30 years, a growing number of studies has broadened its role to cognitive and emotional processing. Anatomical tracing in monkeys showing cerebellum interconnections between neocerebellum and associative brain areas organized in closed loops (Schmahmann and Pandya, 1997; Strick et al., 2009) in agreement with human tractograms reviewed in Habas and Manto (2018), human clinical studies leading to the description of a “cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome” (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998), and activation functional MRI (Stoodley et al., 2012; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2018) have firmly supported the enlarged functional implication of the cerebellum in cognition. Moreover, from a phylogenetical standpoint, increased neocerebellar (posterior lobule) volume (MacLeod et al., 2003) and folding (Sereno et al., 2020), as well as an increased number of associative, mainly prefrontal, cerebello-cortical connections have been observed during the macroevolution history from great apes to humans (Ramnani et al., 2006; Balsters et al., 2010; Smaers, 2014). In other words, the neocerebellar expansion (lobules VII–VIII, especially crus 1–2) is parallel to the associative, mainly prefrontal, expansion in hominoids and humans.

In humans, two complementary imaging methods have been applied to delineate the cerebellar networks subserving cognitive functions. As mentioned above, diffusion imaging coupled with tractography strove to identify neocerebellar afferents and efferents connecting the cerebellum with associative cortices, thalamus, and striatum. The second method, on which we will exclusively focus, consists in determining the brain “resting-state” static and dynamic functional connectivity (rssFC). These methods allowed identifying the associative cortices functionally connected with the neocerebellum, and the whole network the neocerebellum takes part in.

Functional Connectivity Methods

“Resting-state” static and dynamic functional connectivity detects temporal correlations between spontaneous BOLD signal fluctuations in a specific frequency domain (0.01–0.1 Hz) across brain areas belonging to specific—genetically prewired—networks during the brain “resting state.” Several algorithms (Bastos and Schoffelen, 2016) have been utilized to determine cerebellar rssFC, such as correlational, independent component, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations, and regional homogeneity analyses. The most widely used ones are the seed-based correlational analysis and independent component analysis (ICA). The first method computes the r Pearson correlation coefficient between the BOLD time-series of a region of interest (ROI) and the time-series of the rest of the brain. It generates a specific temporal correlational map between the ROI and the functional interconnected brain areas. The second method consists of an exploratory multivariate data-driven approach. ICA decomposes the MRI dataset into statistically independent spatial maps, part of which can represent distinct large-scale networks whose neural nodes exhibit synchronized activity. The other part corresponds to different kinds of noise such as head or eye movements, breathing, heart rate, or spinal fluid pulsation. rssFC studies have identified the associative brain areas specifically connected with the neocerebellum, using seed-based method, and allowed to group these areas in functional networks, called intrinsically connected networks (ICNs), using ICA. However, these methods assume a stationary resting-state brain activity across the whole MRI exam and, thus, fail to describe the temporal dynamics of network recruitment. Dynamic functional connectivity methods have been developed to overcome this important limitation (Hutchison et al., 2013) such as the sliding window, time-frequency, paradigm-/parameter-free mapping, coactivation patterns (CAPs), or innovation-driven coactivation pattern (iCAP) methods (Preti et al., 2017). Put in a nutshell, the former technique relies on the segmentation of the BOLD time series in intervals of equal duration (usually around 30 s). Functional connectivity is then calculated for each interval separately, highlighting the temporal evolution of within- and between-network reconfiguration. Conversely, the CAP method associated with K-mean clustering consists in a point process analysis tracking brief (around 5–10 s) recurring coactivation or co-deactivation patterns by computing the rate of BOLD peaks or trough co-occurrence between an ROI and the rest of the brain voxels. In addition, the iCAP method specifically deals with transient encoding, in the BOLD fluctuations, onsets of network (de-)activations (Karahanoğlu and Van De Ville, 2015). All these methods permit to capture time-varying states characterized by synchronized networks and to quantify their duration (dwell time), the frequency of their occurrence, and the frequency of state-to-state transitions. Dynamic functional connectivity studies revealed that resting-state brain activity is a highly non-stationary process characterized by dynamic within- and across-network reconfiguration into recurring, sometimes overlapping, patterns (CAPs) and correlated with specific phases of the spontaneous low-frequency BOLD signal (Gutierrez-Barragan et al., 2019).

Functional Connectivity and Graph Analysis

Graph analysis can be applied to functional connectivity in order to decipher network topological organization (Bullmore and Sporns, 2009). Brain circuits are regarded as graphs composed of a set of nodes (brain areas) interconnected by edges (functional and/or structural links). An edge between region A and region B is said to be “oriented or directed” if A exerts a causal effect on B (effective connectivity), as measured, for instance, by dynamic causal modeling or Granger causality. Such edges can also be weighted, for example, by the internode correlation coefficient. Several metrics have been defined to thoroughly describe the complex architecture of functional brain networks, such as connection or adjacency matrix, node connectivity degree, node connection strength, internodal path length, shortest path length, etc. (Bullmore and Sporns, 2009; Sporns, 2018). Networks encompass modules interconnected by specific nodes, called provincial hubs, and networks are bridged by connector hubs. Modules are implicated in local specialized information processing, whereas connector hubs contribute to information transferring and integration. Most networks display a specific architecture, called small-world architecture, which is intermediate between random (short path length between nodes) and regular organization (high clustering among nodes). Such small word architecture optimizes regional information processing and distributed integration. Small-world organization has been demonstrated in resting-state networks (Achard et al., 2006; van den Heuvel et al., 2008), and its graph properties varied in relation with the frequency of the BOLD fluctuations (Thompson and Fransson, 2015). Therefore, resting-state networks also undergo dynamic topological reconfiguration.

Functional Connectivity Physiological Basis

The physiological mechanism underlying the endogenous hemodynamic low-frequency fluctuations remains a matter of debate. RssFC in the gray matter would derive from a region-specific complex combination of Fox and Raichle (2007): 1. (inter-) neuronal and astrocytic sources, such as spiking, quantal exocytosis, up–down neuronal states, energetic metabolism, extracellular sodium/potassium regulation (Krishnan et al., 2018), neuromodulation (Cole et al., 2013), microstates (Custo et al., 2017), topological network constraints (Deco and Corbetta, 2011), vasculature and extracerebral blood flow source (Tong et al., 2019), and behavioral sources (Lu et al., 2019). rssFC partly reflects the structural connectivity (SC) (Greicius et al., 2009) and can evolve with learning (epigenesis) in an age-dependent manner (Edde et al., 2020). Moreover, the cortical nodes of the resting-state networks display specific electroencephalographic power variation of infra-slow-to-gamma rhythms (Mantini et al., 2007; Grooms et al., 2017). In particular, there exists a strong correlation between infra-slow scalp potentials and the spontaneous BOLD signal (Hiltunen et al., 2014). Finally, biophysical models showed that the networks composed of coupled gamma oscillators linked by long-range structural connections with delay transmission yielded the emergence of endogenous low-frequency neural activity fluctuations (Cabral et al., 2017). In conclusion, rssFC is an emergent functional pattern of the brain activity, which is spatially and temporally multiscale organized from the cell to the network, and modulated by experience (training).

Region of Interest-Based Associative Cerebello-Cortical “Resting-State” Static and Dynamic Functional Connectivity

fMRI studies (Stoodley et al., 2012; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2018) using task-based protocols clearly delineated different sensorimotor territories such as sensorimotor (anterior lobe: lobules II–VI and VIIIB), oculomotor (vermis of lobules VI–VII, and lobules IX–X), vestibular (lobules IX–X), visual (lobule VI vermal), and auditory (lobules V–VI and left crus 1) zones. Cognitive and emotional regions have also been described, especially in lobule VII (Stoodley et al., 2012; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2018). Using rssFC between the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex, Krienen and Buckner (2009) have found functional coherence between crus 2-lobule VIIB and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, crus 1-lobule IX and the medial prefrontal cortex, and VI/crus 1 border-crus 1-VIIB/VIIIA border and the anterior prefrontal cortex. O’Reilly et al. (2010) and Sang et al. (2012) have also found functional links between lobule VIIA paravermal-crus 2, posterior parietal and cingulate cortices as well as precuneus, lobule VIIA paravermal-IX and the prefrontal cortex, lobule VIII and the visual MT area, lobules VIII–IX and hippocampus and amygdala, and crus 1–2–vermal VIIIb–lobule IX and caudate nucleus. Regarding the vermis, rssFC has been identified between crus 2 and the cuneus, lobule VIIB and anterior thalamus–precuneus–posterior cingulate cortex, lobule VIIIA and superior frontal gyrus, and lobule IX and superior frontal and median temporal gyri (Bernard et al., 2012). All these studies have shown strong and lateralized functional coherence between crus 1–2 and contralateral prefrontal cortex. There exists a homotopic relation between associative cortical surface and their cerebellar representation with an over-representation within the cerebellar cortex of associative brain areas (Buckner et al., 2011).

The ROI-based rssFC demonstrates widespread interconnections between the neocerebellum (lobule VII and VIII) and prefrontal, parietal, cingulate, temporal, and occipital cortices. Such functional connections might rely on cortico-pontine afferents and/or cerebello-thalamo-cortical efferents in agreement with anatomical tracing in animal (Schmahmann and Pandya, 1997; Strick et al., 2009) and human tractography (Habas and Manto, 2018).

Region of Interest-Based Dentato-Cortical “Resting-State” Static and Dynamic Functional Connectivity

Moreover, the human dentate nuclei, the main cerebellar output system to the brain and brainstem, exhibits rssFC with occipital (BA 19), parietal (BA 40), insular (BA 13), cingulate (BA 24), and prefrontal (BA6-8-9-32-46) cortices, the left dentate nucleus displaying more widespread efferents than the right one (Allen et al., 2005). The neocerebellar cortex, especially the prominent lobule VII, and the dentate nuclei constitute a supramodal zone interconnected with the major associative brain regions (O’Reilly et al., 2010) and, to a lesser extent, to affective and associative subcortical nuclei such as the amygdala and striatum. Finally, the interlobular rssFC could subserve a cross-network coordination within the cerebellum; for instance, crus 1–2 are correlated with lobule IX. This could functionally bridge executive network (EN) and default-mode network (DMN) (Bernard et al., 2012). Of interest, topological properties of the intracerebellar rssFC, such as small-world organization, depend upon intelligence coefficient and gender (especially in lobules VI–crus 1 on the left side and vermal VIII) (Pezoulas et al., 2018).

In conclusion, the cerebellum can influence, through dentate-thalamo-cortical projections, all the associative cortices.

Independent Component Analysis-Based Associative Cerebello-Cortical Closed Loops

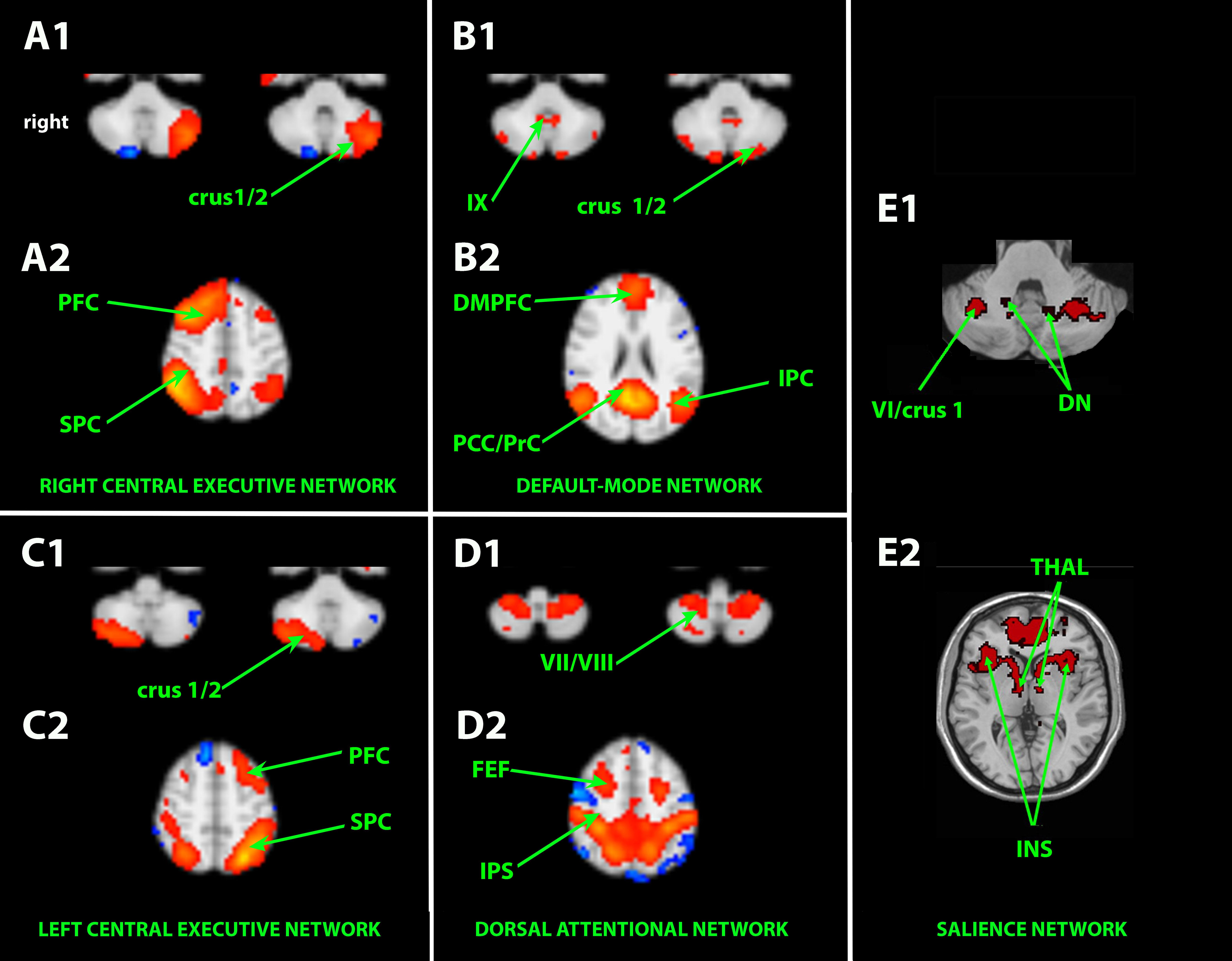

The abovementioned cerebellar areas and functionally associated cortical areas take part in parallel cerebro-ponto/reticulo-cerebello-thalamo-cortical loops. More precisely, these ICNs encompass (Habas et al., 2009; Krienen and Buckner, 2009; Brissenden et al., 2016) (Figure 1):

- the right and left frontoparietal EN passing through crus 1–2 (working memory, adaptive control, and task switching),

- the DMN passing through crus 1–2 and lobule IX (mind wandering, episodic memory, agentivity, navigation, self-reflection, and consciousness),

- the limbic salience network passing through lobules VI–VIIb/crus 1–2 (interoception, autonomic regulation, emotional processing, and bottom–up attention),

- the frontoparietal dorsal attentional network (DAN) passing through lobules VIIB–VIIIA (top–down attention and visual working memory),

- the language-dedicated network passing through the cerebellum (especially right crus 1–2) (Tomasi and Volkow, 2012).

Figure 1. Independent component analysis (ICA)-based resting-state associative cortico-cerebello-cortical networks. A1–B1–C1–D1–E1: axial slices passing through the neocerebellum. A2–B2–C2–D2–E2: axial slices passing through the brain. DMPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; DN, dentate nucleus; FEF, frontal eye field; INS, insula; IPC, inferior parietal cortex; PCC/PrC, posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus; PFC, prefrontal cortex; SPC, superior parietal cortex; Thal, thalamus. Cerebellar lobules are numbered with Latin numerals. Crus 1/2 corresponds to the hemisphere of lobule VIIA.

Using another method (fuzzy-c means clustering algorithm), Lee et al. (2012) also reported during the resting state a ventral attentional network (VAN) previously described by Corbetta et al. (2000). VAN encompasses mainly the inferior and middle prefrontal, temporoparietal junctional, anterior insula, inferior parietal on the right side, and is involved in the bottom–up reorientation of attention. VAN passes bilaterally through parts of lobules VI and VIIIA and, to a lesser extent, lobules crus 1 and VIIIB (Guell et al., 2018; Guell and Schmahmann, 2020). This circuit can switch DAN activity to a novel object of interest. It is noteworthy that several nodes of VAN, such as anterior insula, also belong to the limbic salience network.

In conclusion, the neocerebellum can influence all the associative resting-state networks.

Gradient Organization

It has been shown (Guell et al., 2018; Guell and Schmahmann, 2020) that EN, DMN, and DAN are represented three times in each hemisphere of the neocerebellar cortex (lobules VII–VIII–IX–X), and that these representations are included in functional gradients from attentional (DAN) and task-positive executive (CEN) processing to task-negative default-mode processing (DMN). These three gradient-based representations are found in lobules VI–crus 1, lobules VIIB–crus 2, and lobules IX–X. The rostro-caudal direction of the first representation and the opposite direction of the second representation imply that the crus 1–2 intersection encompasses partial overlapping of the first and second DMN representations. These anatomical gradients mirror hierarchical cognitive control of the prefrontal and parietal cortices (D’Mello et al., 2020). Furthermore, this anatomo-functional gradient organization may reflect the phylogenetical coupling between telencephalization and neocerebellar development with progressive complexification of motor abilities requiring more executive control (attention, anticipation, and regulation) and behavioral integration (emotion-related behaviors) until the cerebellum could also monitor non-motor tasks. The differential role of these multiple representations and whether adjacent contiguous representations, as in the DMN case, would participate in a coordinated computation through, for instance, intracerebellar interconnections, remains to be determined.

Emotional Cerebellum

It is worth noting that the “emotional cerebellum” belongs to SN and DMN, and includes, in particular, the vermis of lobule VII, in accord with the “constructivist” or “scaffolding” hypothesis, claiming that no specific network is dedicated, at least, to emotion such as lateral and medial pain matrix (Iannetti and Mouraux, 2010). Emotions rest on the transient collaboration of distinct intrinsic networks with specific hubs such as insula and anterior cingulate cortex (Menon and Uddin, 2010) and subserving the multidimensional (autonomic, affective, cognitive, mnesic, and motor) aspects of emotion.

Striato-Cerebellar Interconnection

Of interest, several studies found structural and functional connectivity between the cerebellum and the limbic ventral striatum. For instance, Pelzer et al. (2013) found dentato-thalamo-striato-pallidal and sub-thalamo–pontine nuclei–cerebellar connections passing through crus 2/lobules VIII–IX, using probabilistic tractography. Functional coherence was recorded between lobule IX (DMN) and the ventral tegmental area (Murty et al., 2014), and between lobule VII–IX (EN, DMN, and SN) and nucleus accumbens (Cauda et al., 2011). In this vein, a serial reaction time task was accompanied by FC strengthening of a cerebello (crus 1 and dentate nucleus)-thalamo-lenticular nucleo-cortical network during explicit and implicit learning (Sami et al., 2014). Therefore, SC and FC tightly and directly interconnect the (neo-)cerebellum and basal ganglia, which explains why a reward signal can be detected in granule cells and climbing fibers (Wagner and Luo, 2020). Although the role of this latter signal requires further investigations, it has been speculated that the basal ganglia would send to the cerebellum a value estimation of the cerebellar forward model-based selection of cortical planned or executed mental actions (Caligiore et al., 2017). In other words, striatal reinforcement learning could not only modulate the cortical activity but also the cerebellar error-based supervised learning.

Lobule VII “Resting-State” Static and Dynamic Functional Connectivity

Two main networks occupying the most voluminous neocerebellar lobule (VII) are represented by EN and DMN, with an EN predominance. The DMN-related cerebellar zone within crus 1–2 is surrounded by the EN-related cerebellar zone. It has been demonstrated that there exists a greater individual variability in the spatial organization of ICNs within the neocerebellum than in the corresponding cortex, despite a group-level identical spatial pattern, and that the resting state cerebellar fluctuations of EN and DMN lag behind the cortex ones by hundreds of milliseconds (Marek et al., 2018). Marek et al. (2018) hypothesized that the cerebral cortex would transmit information to the neocerebellum using infra-slow activity conveyed by cortico-ponto-cerebellar afferents, and the cerebellum would respond by sending a signal back to the cortex through the cerebello-thalamo-cortical efferents using delta rhythm (0.5–4 Hz). It is noteworthy that delta rhythms are involved in learning-dependent timing (Dalal et al., 2013), and in the latter assumption, part of the endogenous fluctuations could subserve information processing.

Intermittent theta burst magnetic stimulation applied to the neocerebellum induced DMN and EN reconfiguration in terms of functional connectivity and frequency of their associated electroencephalogram signal (Halko et al., 2014; Farzan et al., 2016). The stimulation of vermian lobule VII influenced the DAN with enhanced power in beta/gamma oscillations, whereas the stimulation of the hemisphere of lobule VII modulated the activity of DMN with diminished frontal theta activity. The absence of EN implication could be ascribed to the prominent recruitment of DMN during the resting state. This study illustrated that neocerebellum can differentially alter electrophysiological activity of networks.

Dynamic rssFC, studying time-varying rssFC, coupled with SC reveals the highest rssFC/SC similarity in the posterior lobe compared with the anterior one and a low rssFC variability (Fernandez-Iriondo et al., 2020). These last findings might explain the specific and constant recruitment of DMN and EN during mind wandering (Fox et al., 2016), and the high and temporally stable constraints exerted by SC onto the rssFC of the cognitive circuits. Moreover, the CAPs method was applied to the resting-state BOLD fluctuations (Liu and Duyn, 2013). When the left intraparietal sulcus belonging to DAN was seeded, several CAPs were found in distinct non-overlapping neocerebellar regions showing activation or deactivation. Thus, different transient states of a specific circuit can recruit distinct cerebellar subregions.

Functional Considerations and Synthesis

The polymodal neocerebellum (lobules VII, VIII, and IX) is massively interconnected with associative cortices, as well as with the striatum and amygdala, and it partakes in all associative resting-state circuits with an overrepresentation of EN. Each circuit contributes to a triple functional gradient-based representation within the cerebellar cortex. These resting-state circuits are also characterized by a specific BOLD and electrophysiological signature. The slow BOLD fluctuations, at least for CEN, lag behind the cortical oscillations. This resting-state functional architecture can also be modulated by experience and individual mental abilities. For instance, enhanced functional coherence between crus 1–2 and the right CEN is positively correlated with task goal maintaining (Reineberg et al., 2015). However, functional connectivity analyses per se cannot specify which precise functional action is exerted by such networks. It is assumed that “[…] resting state networks represent a finite set of spatiotemporal basis function from which task-networks are then dynamically assembled and modulated during different behavioral states” (Mantini et al., 2007) even if intrinsic networks, especially DMN, can be actively recruited by mind wandering during the brain resting state. The associative function of the human neocerebellum can only be inferred from task-based fMRI paradigms and from clinical studies. Task-based fMRI meta-analysis has shown involvement of the neocerebellum, including lobules VI, VII, and VIII, in executive, linguistic, and emotional functions (Stoodley et al., 2012). In addition, cerebellar stroke patients exhibited cognitive deficits due to posterior lobe, mainly lobules VII–VIII, and dentate nucleus lesions (Stoodley et al., 2016). Such deficits corresponded to components of the Schmahmann’s cognitive and affective syndrome (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998). Furthermore, from a computational standpoint, because of the structural and histological homogeneity of the cerebellum organized in microcomplexes, it is postulated that motor and associative cerebellum may accomplish the same algorithmic function. Substantial data support the view that the cerebellum may elaborate internal models and especially forward models (Wolpert et al., 1998; Sokolov et al., 2017). Such models would allow prediction of the consequences of intended mental activity during movement (sensory consequence of planned or executed motor action) (Ito, 2005) or cognition (Ito, 2008), and, consequently, would control and optimize the accuracy of the current performance, particularly during supervised learning. The cerebello-cortical closed loops would likely help coordinate or (de-)synchronize cortical areas through the thalamus reviewed in Habas et al. (2019) and to sequence their activity (Molinari et al., 2008). In other words, the cerebellum would act as a general modulator, or “universal transform” (Sereno and Ivry, 2019), generating internal models (functional unicity of microcomplexes) for all motor and associative/emotional domains (functional heterogeneity due to its wide interconnections with the cerebral cortex). Finally, it is noteworthy that task-free and task-based functional parcellations of the cerebellum can exhibit some small regional differences (King et al., 2019): for example, several tasks such as hand movement, working memory and language activation recruit bilateral homologous cerebellar zones, although these zones belong to lateralized resting-state networks. Moreover, if task-free intrinsic connectivity can predict task-evoked activations, small differences can be noted between the former one and the task-state functional connectivity (Cole et al., 2021). Idiosyncratic mental strategies to solve the current tasks may explain these differences observed in functional connectivity.

Conclusion

“Resting-state” static and dynamic functional connectivity sheds light on the genetically prewired and epigenetically tuned resting-state networks underlying the cognitive function of the neocerebellum for motor and non-motor tasks. RssFC demonstrated in humans that the major part of the cerebellum (lobules VII–VIII and dentate nucleus) is functionally interconnected with non-motor associative cortices and constitutes a major relay of all associative resting-state networks. These cerebello-cortical functional interconnections partly reflect the underlying structural hardware. Further studies are required to determine whether this cerebello-cortical coherence would also reflect information processing/transferring between the cerebellum and its targets during the resting state. However, this “functional tracing” method does not furnish any explanation concerning the exact functional or algorithmic role of the neocerebellum in the cognitive domain. It can only suggest that the cerebellar computation based on supervised and predictive control through internal models—the current prevalent hypothesis about the cerebellar function—is the same for networks in charge of movements and networks in charge of executive and emotional processing. Finally, the advances in our understanding of the organization of ICNs would lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis and therapy of major disorders of the brain such as Parkinson’s disease (Mueller et al., 2019) or genuine disorders of the cerebellar circuitry itself (Iang et al., 2019). The understanding of node shaping and synchronizing activities of the cortical areas (Habas et al., 2019) will benefit from refinements in the techniques currently applied, such as neurostimulation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mario Manto, Mons, Belgium.

References

Achard, S., Salvador, R., Whitcher, B., Suckling, J., and Bullmore, E. (2006). A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. J. Neurosci. 26, 63–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3874-05.2006

Allen, G., McColl, R., Barnard, H., Ringe, W. K., Fleckenstein, J., and Cullum, C. M. (2005). Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebellar-prefrontal and cerebellar-parietal functional connectivity. Neuroimage 28, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.013

Balsters, J. H., Cussans, E., Diedrichsen, J., Phillips, K. A., Preuss, T. M., Rilling, J. K., et al. (2010). Evolution of the cerebellar cortex: the selective expansion of prefrontal-projecting cerebellar lobules. Neuroimage 9, 2045–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.045

Bastos, A. M., and Schoffelen, J. M. A. (2016). Tutorial review of functional connectivity analysis methods and their interpretational pitfalls. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9:175. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00175

Bernard, J. A., Seidler, R. D., Hassevoort, K. M., Benson, B. L., Welsh, R. C., Wiggins, J. L., et al. (2012). Resting state cortico-cerebellar functional connectivity networks: a comparison of anatomical and self-organizing map approaches. Front. Neuroanat. 6:31. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00031

Brissenden, J. A., Levin, E. J., Osher, D. E., Halko, M. A., and Somers, D. C. (2016). Functional evidence for a cerebellar node of the dorsal attention network. J. Neurosci. 36, 6083–6096. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0344-16.2016

Buckner, R. L., Krienen, F. M., Castellanos, A., Diaz, J. C., and Yeo, B. T. (2011). The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 2322–2345. doi: 10.1152/jn.00339.2011

Bullmore, E., and Sporns, O. (2009). Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10:186–98. doi: 10.1038/nrn2575

Cabral, J., Kringelbach, M. L., and Deco, G. (2017). Functional connectivity dynamically evolves on multiple time-scales over a static structural connectome: models and mechanisms. Neuroimage 160, 84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.03.045

Caligiore, D., Pezzulo, G., Baldassarre, G., Bostan, A. C., Strick, P. L., Doya, K., et al. (2017). Consensus paper: towards a systems-level view of cerebellar function: the interplay between cerebellum, basal ganglia, and cortex. Cerebellum 1, 203–229. doi: 10.1007/s12311-016-0763-3

Cauda, F., Cavanna, A. E., D’agata, F., Sacco, K., Duca, S., and Geminiani, G. C. (2011). Functional connectivity and coactivation of the nucleus accumbens: a combined functional connectivity and structure-based meta-analysis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 2864–2877. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2011.21624

Cole, D. M., Beckmann, C. F., Oei, N. Y., Both, S., van Gerven, J. M., and Rombouts, S. A. (2013). Differential and distributed effects of dopamine neuromodulations on resting-state network connectivity. Neuroimage 78, 59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.034

Cole, M. W., Ito, T., Cocuzza, C., and Sanchez-Romero, R. (2021). The functional relevance of task-state functional connectivity. J. Neurosci. 41, 2684–2702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1713-20.2021 Epub ahead of print. JN-RM-1713-20

Corbetta, M., Kincade, J. M., Ollinger, J. M., McAvoy, M. P., and Shulman, G. L. (2000). Voluntary orienting is dissociated from target detection in human posterior parietal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 3:292–7. doi: 10.1038/73009

Custo, A., Van De Ville, D., Wells, W. M., Tomescu, M. I., Brunet, D., and Michel, C. M. (2017). Electroencephalographic resting-state networks: source localization of microstates. Brain Connect. 7, 671–682. doi: 10.1089/brain.2016.0476

Dalal, S. S., Osipova, D., Bertrand, O., and Jerbi, K. (2013). Oscillatory activity of the human cerebellum: the intracranial electrocerebellogram revisited. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.006

Deco, G., and Corbetta, M. (2011). The dynamical balance of the brain at rest. Neuroscientist 17, 107–123. doi: 10.1177/1073858409354384

D’Mello, A. M., Gabrieli, J. D. E., and Nee, D. E. (2020). Evidence for hierarchical cognitive control in the human cerebellum. Curr. Biol. 30, 1881–1892.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.028

Edde, M., Di Scala, G., Dupuy, M., Dilharreguy, B., Catheline, G., and Chanraud, S. (2020). Learning-drivencerebellar intrinsic functional connectivity changes in men. J. Neurosci. Res. 98, 668–679. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24555

Farzan, F., Pascual-Leone, A., Schmahmann, J. D., and Halko, M. (2016). Enhancing the temporal complexity of distributed brain networks with patterned cerebellar stimulation. Sci. Rep. 6:23599. doi: 10.1038/srep23599

Fernandez-Iriondo, I., Jimenez-Marin, A., Diez, I., Bonifazi, P., Swinnen, S. P., Munoz, M. A., et al. (2020). Small variation in dynamic functional connectivity in cerebellar networks. Quantitative biology–neurons and cognition. arXiv:2011.13506 [Preprint] Available online at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2011.13506.pdf (accessed November 27, 2020).

Fox, K. C., Spreng, R. N., Ellamil, M., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., and Christoff, K. (2016). The wandering brain: meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind-wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage 111:611–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.02.039

Fox, M. D., and Raichle, M. E. (2007). Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201

Greicius, M. D., Supekar, K., Menon, V., and Dougherty, R. F. (2009). Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb. Cortex 19, 72–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn059

Grooms, J. K., Thompson, G. J., Pan, W. J., Billings, J., Schumacher, E. H., Epstein, C. M., et al. (2017). Infraslow electroencephalographic and dynamic resting state network activity. Brain Connect. 7, 265–280. doi: 10.1089/brain.2017.0492

Guell, X., and Schmahmann, J. (2020). Cerebellar functional anatomy: a didactic summary based on human fMRI evidence. Cerebellum 19, 1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12311-019-01083-9

Guell, X., Schmahmann, J. D., Gabrieli, J., and Ghosh, S. S. (2018). Functional gradients of the cerebellum. Elife 7:e36652. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36652

Gutierrez-Barragan, D., Basson, M. A., Panzeri, S., and Gozzi, A. (2019). Infraslow state fluctuations govern spontaneous fMRI network dynamics. Curr. Biol. 29, 2295–2306.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.017

Habas, C., Kamdar, N., Nguyen, D., Prater, K., Beckmann, C. F., Menon, V., et al. (2009). Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks. J. Neurosci. 29, 8586–8594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1868-09.2009

Habas, C., and Manto, M. (2018). Probing the neuroanatomy of the cerebellum using tractography. Handb Clin. Neurol. 154, 235–249. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63956-1.00014-X

Halko, M. A., Farzan, F., Eldaief, M. C., Schmahmann, J. D., and Pascual-Leone, A. (2014). Intermittent theta-burst stimulation of the lateral cerebellum increases functional connectivity of the default network. J. Neurosci. 34, 12049–12056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1776-14.2014

Hiltunen, T., Kantola, J., Abou Elseoud, A., Lepola, P., Suominen, K., Starck, T., et al. (2014). Infra-slow EEG fluctuations are correlated with resting-state network dynamics in fMRI. J. Neurosci. 34, 356–362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0276-13.2014

Hutchison, R. M., Womelsdorf, T., Allen, E. A., Bandettini, P. A., Calhoun, V. D., Corbetta, M., et al. (2013). Dynamic functional connectivity: promise, issues, and interpretations. Neuroimage 80, 360–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.079

Iang, X., Faber, J., Giordano, I., Machts, J., Kindler, C., Dudesek, A., et al. (2019). Characterization of cerebellar atrophy and resting state functional connectivity patterns in sporadic adult-onset ataxia of unknown etiology (SAOA). Cerebellum 18, 873–881.

Iannetti, G. D., and Mouraux, A. (2010). From the neuromatrix to the pain matrix (and back). Exp. Brain Res. 205, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2340-1

Ito, M. (2005). Bases and implications of learning in the cerebellum–adaptive control and internal model mechanism. Prog. Brain Res. 148, 95–109. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)48009-1

Ito, M. (2008). Control of mental activities by internal models in the cerebellum. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 304–313. doi: 10.1038/nrn2332

Karahanoğlu, F. I., and Van De Ville, D. (2015). Transient brain activity disentangles fMRI resting-state dynamics in terms of spatially and temporally overlapping networks. Nat. Commun. 6:7751. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8751

King, M., Hernandez-Castillo, C. R., Poldrack, R. A., Ivry, R. B., and Diedrichsen, J. (2019). Functional boundaries in the human cerebellum revealed by a multi-domain task battery. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1371–1378. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0436-x

Krienen, F. M., and Buckner, R. L. (2009). Segregated fronto-cerebellar circuits revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Cereb. Cortex 9, 2485–2497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp135

Krishnan, G. P., González, O. C., and Bazhenov, M. (2018). Origin of slow spontaneous resting-state neuronal fluctuations in brain networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 6858–6863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715841115

Lee, M. H., Hacker, C. D., Snyder, A. Z., Corbetta, M., Zhang, D., Leuthardt, E. C., et al. (2012). Clustering of resting state networks. PLoS One 7:e40370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040370

Liu, X., and Duyn, J. H. (2013). Time-varying functional network information extracted from brief instances of spontaneous brain activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10, 4392–4397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216856110

Lu, H., Jaime, S., and Yang, Y. (2019). Origins of the resting-state functional mri signal: potential limitations of the “neurocentric”. Model. Front. Neurosci. 13:1136. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01136

MacLeod, C. E., Zilles, K., Schleicher, A., Rilling, J. K., and Gibson, K. R. (2003). Expansion of the neocerebellum in Hominoidea. J. Hum. Evol. 44(4):401–29. doi: 10.1016/s0047-2484(03)00028-9

Mantini, D., Perrucci, M. G., Del Gratta, C., Romani, G. L., and Corbetta, M. (2007). Electrophysiological signatures of resting state networks in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13170–13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700668104

Marek, S., Siegel, J. S., Gordon, E. M., Raut, R. V., Gratton, C., Newbold, D. J., et al. (2018). Spatial and temporal organization of the individual human cerebellum. Neuron 100, 977–993.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.010

Menon, V., and Uddin, L. Q. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0

Molinari, M., Chiricozzi, F. R., Clausi, S., Tedesco, A. M., De Lisa, M., and Leggio, M. G. (2008). Cerebellum and detection of sequences, from perception to cognition. Cerebellum 7, 611–615. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0060-x

Mueller, K., Jech, R., Ballarini, T., Holiga, Š, Rùžièka, F., Piecha, F. A., et al. (2019). Modulatory effects of levodopa on cerebellar connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Cerebellum 18, 212–224.

Murty, V. P., Shermohammed, M., Smith, D. V., Carter, R. M., Huettel, S. A., and Adcock, R. A. (2014). Resting state networks distinguish human ventral tegmental area from substantia nigra. Neuroimage 100, 580–589. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.047

O’Reilly, J. X., Beckmann, C. F., Tomassini, V., Ramnani, N., and Johansen-Berg, H. (2010). Distinct and overlapping functional zones in the cerebellum defined by resting state functional connectivity. Cereb. Cortex 20, 953–965. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp157

Pelzer, E. A., Hintzen, A., Goldau, M., von Cramon, D. Y., Timmermann, L., and Tittgemeyer, M. (2013). Cerebellar networks with basal ganglia: feasibility for tracking cerebello-pallidal and subthalamo-cerebellar projections in the human brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 38, 3106–3114. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12314

Pezoulas, V. C., Zervakis, M., Michelogiannis, S., and Klados, M. A. (2018). Resting-state functional connectivity and network analysis of cerebellum with respect to [corrected] IQ and gender. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11:189. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00189

Preti, M. G., Bolton, T. A., and Van De Ville, D. (2017). The dynamic functional connectome: state-of-the-art and perspectives. Neuroimage 160, 41–54.

Ramnani, N., Behrens, T. E., Johansen-Berg, H., Richter, M. C., Pinsk, M. A., Andersson, J. L., et al. (2006). The evolution of prefrontal inputs to the cortico-pontine system: diffusion imaging evidence from macaque monkeys and humans. Cereb. Cortex 16, 811–818. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj024

Reineberg, A. E., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Depue, B. E., Friedman, N. P., and Banich, M. T. (2015). Resting-state networks predict individual differences in common and specific aspects of executive function. Neuroimage 104, 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.045

Sami, S., Robertson, E. M., and Miall, R. C. (2014). The time course of task-specific memory consolidation effects in resting state networks. J. Neurosci. 34, 3982–3992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4341-13.2014

Sang, L., Qin, W., Liu, Y., Han, W., Zhang, Y., Jiang, T., et al. (2012). Resting-state functional connectivity of the vermal and hemispheric subregions of the cerebellum with both the cerebral cortical networks and subcortical structures. Neuroimage 61, 1213–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.011

Schmahmann, J. D., and Pandya, D. N. (1997). The cerebrocerebellar system. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 41, 31–60. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60346-3

Schmahmann, J. D., and Sherman, J. C. (1998). The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain 121(Pt 4), 561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561

Sereno, M., and Ivry, R. B. (2019). Universal transform or multiple functionality? Understanding the contribution of the human cerebellum across task domains. Neuron 102, 918–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.04.021

Sereno, M. I., Diedrichsen, J., Tachrount, M., Testa-Silva, G., d’Arceuil, H., and De Zeeuw, C. (2020). The human cerebellum has almost 80% of the surface area of the neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 19538–19543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002896117

Smaers, J. B. (2014). Modeling the evolution of the cerebellum: from macroevolution to function. Prog. Brain Res. 210, 193–216. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63356-9.00008-X

Sokolov, A. A., Miall, R. C., and Ivry, R. B. (2017). The cerebellum: adaptive prediction for movement and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 313–332. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.02.005

Sporns, O. (2018). Graph theory methods: applications in brain networks. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 20, 111–121. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.2/osporns

Stoodley, C. J., MacMore, J. P., Makris, N., Sherman, J. C., and Schmahmann, J. D. (2016). Location of lesion determines motor vs. cognitive consequences in patients with cerebellar stroke. Neuroimage Clin. 12, 765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.10.013

Stoodley, C. J., and Schmahmann, J. D. (2018). Functional topography of the human cerebellum. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 154, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63956-1.00004-7

Stoodley, C. J., Valera, E. M., and Schmahmann, J. D. (2012). Functional topography of the cerebellum for motor and cognitive tasks: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 59, 1560–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.065

Strick, P. L., Dum, R. P., and Fiez, J. A. (2009). Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 413–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125606

Thompson, W. H., and Fransson, P. (2015). The frequency dimension of fMRI dynamic connectivity: network connectivity, functional hubs and integration in the resting brain. Neuroimage 121, 227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.022

Tomasi, D., and Volkow, N. (2012). Resting functional connectivity of language networks: characterization and reproductibility. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 841–854. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.177

Tong, Y., Hocke, L. M., and Frederick, B. B. (2019). Low frequency systemic hemodynamic “noise” in resting state bold fmri: characteristics, causes, implications, mitigation strategies, and applications. Front. Neurosci. 13:787. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00787

van den Heuvel, M. P., Stam, C. J., Boersma, M., and Hulshoff Pol, H. E. (2008). Small-world and scale-free organization of voxel-based resting-state functional connectivity in the human brain. Neuroimage 43, 528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.010

Wagner, M. J., and Luo, L. (2020). Neocortex-cerebellum circuits for cognitive processing. Trends Neurosci. 43, 42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2019.11.002

Keywords: neocerebellum, crus 1–2, cognition, functional connectivity, resting-state, intrinsic networks

Citation: Habas C (2021) Functional Connectivity of the Cognitive Cerebellum. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15:642225. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2021.642225

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 11 March 2021;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Angelo Quartarone, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Timothy J. Ebner, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesMatilde Inglese, University of Genoa, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Habas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christophe Habas, Y2hhYmFzQDE1LTIwLmZy

Christophe Habas

Christophe Habas