94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Synaptic Neurosci. , 27 November 2018

Volume 10 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2018.00045

This article is part of the Research Topic Dynamics and Modulation of Synaptic Transmission in the Mammalian CNS View all 11 articles

Research on glial cells over the past 30 years has confirmed the critical role of astrocytes in pathophysiological brain states. However, most of our knowledge about astrocyte physiology and of the interactions between astrocytes and neurons is based on the premises that astrocytes constitute a homogeneous cell type, without considering the particular properties of the circuits or brain nuclei in which the astrocytes are located. Therefore, we argue that more-sophisticated experiments are required to elucidate the specific features of astrocytes in different brain regions, and even within different layers of a particular circuit. Thus, in addition to considering the diverse mechanisms used by astrocytes to communicate with neurons and synaptic partners, it is necessary to take into account the cellular heterogeneity that likely contributes to the outcomes of astrocyte–neuron signaling. In this review article, we briefly summarize the current data regarding the anatomical, molecular and functional properties of astrocyte–neuron communication, as well as the heterogeneity within this communication.

A fundamental property of the mammalian brain is its ability to modify its function based on experience, and thereby to alter subsequent behavior. By changing the strength of transmission at preexisting synapses, transient experiences can be incorporated into the neuronal circuits as persistent memory traces during both development and adulthood. As such, synaptic plasticity is a fundamental mechanism that supports brain function (Buzsáki and Chrobak, 2005). Among the different factors that regulate synaptic plasticity, glial cells have been found to be key players in maintenance of synapse homeostasis (Eroglu and Barres, 2010). The biggest challenge when studying the effects of glial cells on brain activity is isolating the different cell-type components, i.e., neurons vs. glia. Recent research advances using various strategies, such as pharmacological or genetic manipulation and gene expression from viral vectors (Nimmerjahn and Bergles, 2015; Oliveira et al., 2015; Ben Haim and Rowitch, 2017), have allowed researchers to elucidate the role of glial cells in several aspects of brain function, and such knowledge may lead to the development of new therapies and biomarkers for many types of neurological dysfunction (Almad and Maragakis, 2018).

Astrocytes, after oligodendrocytes, constitute the major glial cell population in the mammalian brain (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2015). Since the tripartite synapse concept emerged in 1999 (Araque et al., 1999), data from numerous studies have supported the notion that astrocytes are involved in tight regulation of synaptic transmission (Eroglu and Barres, 2010; Perea et al., 2014; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016). Given that astrocytes have been revealed as strategic cells for controlling neuronal activity, it is crucial to understand the properties and functions of these cells. Astrocytes are now recognized as a markedly heterogeneous group comprising different morphologically specialized cells, such as protoplasmic astrocytes, fibrous astrocytes, perivascular glia, velate astrocytes, Müller cells or Bergman glia, which show particular molecular profiles and which have been extensively reviewed previously (Matyash and Kettenmann, 2010; Reichenbach et al., 2010; Farmer and Murai, 2017). Additionally, there are significant differences between human astrocytes and their rodent counterparts, i.e., the gene expression pattern (Zhang et al., 2016), size and complexity of cellular architecture (Oberheim et al., 2009), and faster calcium dynamics (Oberheim et al., 2009) indicate specialization of glial cells in the human brain that may contribute to the distinctive neurological capabilities that make humans different from other mammals (Han et al., 2013). It is not yet quite clear how those differences account for the higher functions of the human brain (Min et al., 2012; Vasile et al., 2017).

One of the key factors that regulates intracellular signaling in astrocytes is calcium (Ca2+). However, because the controversies regarding astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and synaptic plasticity, which have been revised in recent excellent reports (Araque et al., 2014; Rusakov, 2015; Fiacco and McCarthy, 2018; Savtchouk and Volterra, 2018), Ca2+ signals will not be further discussed in this review article.

The goal of the present review is to highlight the existing data supporting the critical roles of astrocytes in synaptic function, and how those roles may be determined by structurally and functionally different astrocyte populations.

Astrocytes tightly enwrap neuronal cell bodies, axons, dendrites and synapses (Montagnese et al., 1988; Ventura and Harris, 1999; Khan et al., 2001; Witcher et al., 2010), and their endfoot processes associate with vascular endothelial cells and pericytes (Liebner et al., 2018), being ideally positioned to monitor and regulate both synaptic activity and blood brain barrier. The close association between astrocytes and neuronal synapses is a critical factor required for the maintenance of brain homeostasis (Perea et al., 2009). Astrocytes predominantly show potassium (K+) conductance (Kuffler and Nicholls, 1966; Hertz et al., 2013), which is mainly due to the inwardly rectifying K + (Kir) channels that control the hyperpolarized resting potential of astrocytes (Seifert et al., 2009). Among other important channels/ion transporters (e.g., aquaporin-4, chloride channels, Na+-Ca2+ exchangers; Haj-Yasein et al., 2011b; Halnes et al., 2013), high densities of Kir4.1 channels have been found on thin processes that face the synapses, thus allowing rapid uptake of K+ from the synaptic cleft and redistribution of K+ in the extracellular space during neuronal activity (Kuffler and Nicholls, 1966; Seifert et al., 2018). Indeed, reduced levels of Kir4.1 protein expression in astrocytes lead to elevated extracellular levels of K+ and neuronal membrane depolarization, which has been related to multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, epilepsy and Huntington’s disease (Haj-Yasein et al., 2011a; Jiang et al., 2016; Dossi et al., 2018). K+ buffering has been well studied in the retina, where Müller cells show an enriched distribution of Kir channels in endfoot processes (Newman, 1984, 1993). The water channel aquaporin-4 is also highly expressed at the same subcellular domains (Nagelhus et al., 1999), indicating that K+ uptake generates parallel water fluxes that are required to dissipate such osmotic changes. Additionally, it has been shown in optic nerve and hippocampus that Na+/K+-ATPase activity efficiently contributes to the clearance of K+ following neuronal activity (Ransom et al., 2000; D’Ambrosio et al., 2002; Larsen et al., 2014), indicating that astrocytes may use a combination of different mechanisms to control extracellular K+ levels.

Astrocytic membranes are enriched in glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporters that are differentially expressed throughout the adult brain. These transporters serve as an efficient mechanism for clearing these neurotransmitters (NTs) from the extracellular space after neuronal activity (Borden, 1996; Bergles and Jahr, 1997; Danbolt, 2001). In fact, the expression of glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) and glutamate–aspartate transporter (GLAST) prevents glutamate-derived excitotoxicity during neuronal regular synaptic transmission (Danbolt, 2001); and under glutamatergic over-excitation, such as that observed in conditions like epilepsy or brain trauma (Tanaka et al., 1997; Goodrich et al., 2013). Although these transporters are distributed throughout the brain, the highest levels of GLT-1 are found in the hippocampus and the neocortex; while GLAST is enhanced in the cerebellum (Chaudhry et al., 1995; Lehre and Danbolt, 1998), and retina (Rauen et al., 1996; Lehre et al., 1997). Additionally, two populations of astrocytes have been described, based on the predominant expression of particular glutamate transporters in the hippocampus (Matthias et al., 2003). Interestingly, by modulating the expression levels and surface diffusion of glutamate transporters, astrocytes influence synaptic transmission by controlling the glutamate spillover beyond the synapse. Such glutamate spillover can activate extrasynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors (Huang et al., 2004), which shape the kinetics of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs; Murphy-Royal et al., 2015). Hence, changes in EPSCs have important effects on the local and temporal integration of synaptic inputs by neuronal networks, and consequently on synaptic plasticity. Therefore, glutamate transporters not only support synaptic homeostasis, but also contribute, at least in part, to plasticity processes at the synaptic levels (reviewed by Rose et al., 2017).

Interestingly, the GABA transporters (GATs) GAT-1 and GAT-3 show particular cellular and sub-cellular distributions throughout the brain (Ribak et al., 1996; Boisvert et al., 2018). GAT-3 is the most abundant GAT in astrocytes and is localized in astrocytic processes that are adjacent to synapses and cell bodies, but are also close to basal and apical dendrites (Boddum et al., 2016), while GAT-1 can be found in distal astrocytic processes and is more abundant in neurons (Borden, 1996; Scimemi, 2014). Activation of GAT-3 results in a rise in Na+ concentrations in hippocampal astrocytes and a consequent increase in intracellular Ca2+ through the action of Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (Doengi et al., 2009). Thus, GABA-uptake by astrocytic GAT-3 can stimulate the release of ATP/adenosine that contributes to downregulation of the excitatory synaptic transmission, and provides a mechanism for homeostatic regulation of synaptic activity in the hippocampus (Boddum et al., 2016). In the thalamus, GAT-1 and GAT-3 occupy different domains within the astrocytic membrane, with GAT-1 being located closer to synaptic contacts than GAT-3 (Beenhakker and Huguenard, 2010); this implies that these transporters might play different roles in GABAergic synaptic function. For instance, research suggests that GAT-1 reduces GABA spillover from the synaptic cleft, while GAT-3 controls the extrasynaptic GABA tone, thus regulating tonic inhibition (Beenhakker and Huguenard, 2010). There is a causal relationship between intracellular Ca2+ levels and GAT-3 expression in striatal astrocytes (Yu et al., 2018). Downregulation of Ca2+ signaling enhances membrane expression of GAT-3, resulting in the reduction of GABAergic tone and abnormal repetitive behavioral phenotypes in mice (Yu et al., 2018) that are related to human psychiatric disorders.

Together with glutamate and GABA uptake, a transient increase in intracellular Na+ concentration occurs (Gadea and López-Colomé, 2001a,b). That Na+ local boost can be buffered through gap junctions to neighboring astrocytes acting as an intercellular signaling molecule (Rose and Ransom, 1997; Kirischuk et al., 2007). Considering that Na+ is also co-transported with other transmitters and molecules, changes in the intracellular Na+ concentration are directly related with changes in synaptic transmission (Karus et al., 2015), and the activity of Na+/K+-ATPase, linking Na+ homeostasis to metabolic functions in astrocytes (for review see Chatton et al., 2016).

Therefore, astrocytes are powerful regulators of synaptic activity by combining the extent of synapse coverage and the expression level of ion channels and neurotransmitter transporters at their cell membrane.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that astrocytes do not ensheath all synapses (Ventura and Harris, 1999; Witcher et al., 2010; Chung et al., 2015a). Moreover, the astrocytic coverage of synapses is a highly dynamic process that changes throughout development and adulthood (Chung et al., 2015a; Heller and Rusakov, 2015). Thus, in layer IV of the somatosensory cortex in adult mice, 90% of excitatory synapses are in contact with astrocytes (Bernardinelli et al., 2014a), as compared to 60%–90% of these synapses in the hippocampus (Ventura and Harris, 1999). In the cerebellum, only ca. 15% of mossy fiber synapses on granule cells are in contact with astrocyte processes; in contrast, the climbing fibers show ca. 85% of synapses covered by astroglial processes, and ca. 65% of parallel fiber synapses are also in relatively close contact with Bergmann glia (Xu-Friedman et al., 2001). Additionally, changes in astrocyte–synapse associations can be induced by different neuronal activity levels (Genoud et al., 2006; Bernardinelli et al., 2014b; Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014) and by a range of physiological conditions, including starvation and satiety (Panatier et al., 2006; Theodosis et al., 2008; Chung et al., 2015a). Hence, structural changes in the astrocytic processes can greatly impact the glial network signaling as well as its relationship with synapses, which will shift the function of neuronal circuits.

Astrocytes are enriched in gap junctions, which are formed by connexins (Cxs; Nagy et al., 1999). Cx43 and Cx30 are the main Cxs expressed by astrocytes (Nagy et al., 1999). Through gap junctions, which allow intercellular diffusion of ions, second messengers and small molecules of up to ca. 1.8 kDa (Kumar and Gilula, 1996), astrocytes form broad cellular networks that involve hundreds of astrocytes (Giaume et al., 2010; Pannasch et al., 2011). In fact, astrocytic intercellular diffusion has been reported for cyclic AMP, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3), Ca2+, glutamate, ATP and energy metabolites (glucose, glucose-6-phosphate and lactate; Tabernero et al., 2006; Harris, 2007). Prior research has demonstrated that the intact function of local astrocyte networks is critical for complex cerebral functions, including sleep–wake cycle regulation, sensory functions, cognition and behavior (for a review see Oliveira et al., 2015; Charvériat et al., 2017). Interestingly, such astrocytic networks show selective and preferential coupling, meaning that not all neighboring astrocytes are functionally connected by gap junctions (Houades et al., 2008; Roux et al., 2011). Based on data of intracellular loading of tracers/reporters in single cells, it has been shown that astrocytes occupy non-overlapping territories, that is, they have independent domains that are established during development (Bushong et al., 2002; Ogata and Kosaka, 2002). However, it remains unclear whether the preferential connectivity between subsets of astrocytes is determined by a common astrocyte progeny during embryonic development or by local factors. Studies focused on astrocyte lineage have revealed that multiple astrocyte clones derived from single precursor cells coexist in the adult cortex, where these clones establish spatially restricted domains that contain up to 40 astrocytes (García-Marqués and López-Mascaraque, 2013). Cx43 is expressed from early in development in radial glial cells; however, Cx30 is expressed postnatally in rodent astrocytes around the third postnatal week (Kunzelmann et al., 1999; Nagy and Rash, 2000). Such different expression of Cxs generates additional differences in the intercellular connectivity of astrocyte networks, with implications in metabolic states (glucose and lactate supply) and synaptic transmission (Rouach et al., 2008). Moreover, gap-junction connectivity is highly sensitive to changes in phosphorylation/dephosphorylation pathways, intracellular calcium levels, pH and redox-related variations (Sáez et al., 2014). Altogether, the data support the existence of plasticity within astrocyte networks. Because astrocytes form large circuits, further studies are required to understand how signals detected within particular astrocytic domains work either locally to affect a few synapses from the same neuron, or remotely to regulate synapses that possibly belong to different neurons or circuits. Future research should also clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying the complex actions of astrocyte–synapse communication in brain circuits.

Intracellular Ca2+ signals, driven by endogenous signaling or neuronal activity, are also related to the release of active substances, called gliotransmitters (GTs), which target the synapse via vesicular-dependent (Araque et al., 2000, 2014; Bezzi et al., 2004; Bowser and Khakh, 2007; Parpura and Zorec, 2010) and -independent mechanisms (Duan et al., 2003; Hamilton and Attwell, 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Woo et al., 2012). Although there are controversies regarding the astrocytic expression of different components required for vesicular transmitter release (Schwarz et al., 2017; Bohmbach et al., 2018), several studies have elucidated the mechanisms underlying the dynamic regulation of synaptic transmission by astrocyte activity; this topic has been extensively reviewed (Araque et al., 2014; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Allen and Eroglu, 2017).

By releasing glutamate, D-serine, GABA, ATP, adenosine, or tumor necrosis factor-alpha, among others, astrocytes control the basal tone of synaptic activity and the threshold for synaptic plasticity (Beattie et al., 2002; Angulo et al., 2004; Fellin et al., 2004; Jourdain et al., 2007; Perea and Araque, 2007; Henneberger et al., 2010; Bonansco et al., 2011; Di Castro et al., 2011; Panatier et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013; Shigetomi et al., 2013; Gómez-Gonzalo et al., 2015; De Pittà and Brunel, 2016; Petrelli et al., 2018). One hippocampal astrocyte ensheaths approximately 120,000 synapses (Bushong et al., 2002) belonging to different cell types (excitatory vs. inhibitory neurons) and circuits, and that astrocyte might be able to detect the NTs released from all of those synapses. Indeed, glutamatergic synaptic activation of astrocytes stimulates the release of glutamate, D-serine, ATP, or adenosine, which, through the activation of pre- and postsynaptic receptors sets the threshold for basal synaptic transmission (Bonansco et al., 2011; Panatier et al., 2011), and enhances short- and long-term glutamatergic synaptic plasticity (Jourdain et al., 2007; Perea and Araque, 2007; Henneberger et al., 2010). GABAergic activity stimulates astrocyte Ca2+ signaling (Mariotti et al., 2016, 2018; Perea et al., 2016), which induces the release of ATP and adenosine, decreasing the excitatory synaptic tone (Serrano et al., 2006; Covelo and Araque, 2018). Interestingly, hippocampal astrocytes can contribute to neuronal information processing by decoding GABAergic synaptic activity based on frequency and duration of interneuron firing (Perea et al., 2016; Covelo and Araque, 2018). Such decoding dictates whether astrocytes release either glutamate, which enhances excitatory synaptic activity (Perea et al., 2016), or ATP/adenosine, which reduces excitatory synaptic strength (Covelo and Araque, 2018).

Pyramidal cell activity can also engage astrocytes through endocannabinoid (eCB) signaling. eCBs play a critical role in short- and long-term plasticity at both excitatory and inhibitory synapses, mainly via retrograde signaling (Kano, 2014). However, growing evidence indicates that astrocytes participate in eCB signaling, with the postsynaptic activity-dependent release of eCBs stimulating Ca2+ signaling in surrounding astrocytes, ultimately influencing glutamatergic synaptic transmission (Navarrete and Araque, 2010; Min and Nevian, 2012; Gómez-Gonzalo et al., 2015; Martín et al., 2015; Andrade-Talavera et al., 2016; Martin-Fernandez et al., 2017; Robin et al., 2018). In fact, research has shown that eCB-astrocyte activation stimulates the release of glutamate, which enhances synaptic strength, with both short-term (Navarrete and Araque, 2010; Martín et al., 2015; Martin-Fernandez et al., 2017) and long-term effects (Gómez-Gonzalo et al., 2015). Moreover, D-serine is released in response to eCB-astrocyte activation, and by stimulating synaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), actively contributes to hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP; Robin et al., 2018) and spike timing-dependent long-term depression (tLTD; Min and Nevian, 2012; Andrade-Talavera et al., 2016). Therefore, eCBs that mainly depress synaptic transmission can, by activating astrocytes, exert opposite or additive effects on excitatory synaptic transmission in different brain areas, such as the hippocampus. This has important homeostatic effects that contribute to achieving coordinated activity among neuronal ensembles. Another important factor released by astrocytes is S100β, a Ca2+ binding protein, that is able to induce neuronal bursting and engages rhythmic activity both in the dorsal part of the trigeminal main sensory nucleus (NVsnpr; Morquette et al., 2015), and in the prefrontal cortex (Brockett et al., 2018). Additionally, astrocytic S100β enhances synchrony between theta and gamma cortical oscillations and improves cognitive flexibility (Brockett et al., 2018), indicating the behavioral impact of GTs.

These representative examples show the complex and refined effects of astrocyte-released transmitters on neuronal activity. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that astrocytes can also respond to other neuromodulators, such as norepinephrine (Bekar et al., 2008; Paukert et al., 2014), acetylcholine (Takata et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Navarrete et al., 2012; Papouin et al., 2017), dopamine (Jennings et al., 2017), and molecules derived from the neuroendocrine system (Fuente-Martin et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2014), possibly in different fashions depending on the nature of NTs and affecting particular neural circuits that rule behavioral outputs. For example, astrocytes in the hypothalamus respond to the hormones leptin, ghrelin, and insulin, and regulate neuronal activity by releasing ATP (Kim et al., 2014; García-Cáceres et al., 2016), controlling the food consumption. Astrocytes form the dorsal suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and show an anti-phase oscillatory activity compared to neurons, being more active during the night and reducing neuronal firing by the release of glutamate (Brancaccio et al., 2017). Hence, SCN astrocytes show high Ca2+ activity at night and release high levels of glutamate into the extracellular space, activating presynaptic NMDARs in SCN neurons, which in turn increases the GABAergic tone across the circuit. However, during daytime extracellular levels of glutamate are reduced by an increased glutamate uptake, and consequently GABAergic tone is reduced, facilitating neuronal firing (Brancaccio et al., 2017). Astrocytes also participate in sleep homeostasis, which is regulated by the accumulation of adenosine (Halassa et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2012). By releasing ATP/adenosine and glutamate, astrocytes regulate cortical states and induce the transition into slow neuronal oscillations associated with sleep (Fellin et al., 2009; Poskanzer and Yuste, 2016; Clasadonte et al., 2017). In this spirit, the lymphatic-like pathway organized by astrocytes and blood vessels in the central nervous system, the “glymphatic” hypothesis (Xie et al., 2013; Plog and Nedergaard, 2018), suggests a significant impact of astrocyte activity during sleep in terms of the clearance of different solutes accumulated during wakefulness. Additionally, glymphatic system seems to be critical for the distribution of nutrients and metabolic homeostasis throughout the brain (Lundgaard et al., 2017), and an enhanced glymphatic clearance has been related with the reduced lactate levels in the brain that usually accompany the transition from wakefulness to sleep (Lundgaard et al., 2017). Therefore, the opposite and complementary neuron–astrocyte signals mutually support the mammalian circadian clock.

Interestingly, the disruption of the glymphatic system has been related with the accumulation of toxic species in the brain, such as amyloid β (Xie et al., 2013). Glymphatic system dysfunctions have been found in murine models that resemble human type 2 diabetes, which also show accumulation of misaggregated proteins (Jiang et al., 2017). Whether glymphatic system alterations and the accumulation of waste in the paravascular space drive the cognitive deficits associated with Alzheimer Disease (AD) or diabetes (Yaffe et al., 2004; Moheet et al., 2015) is under debate (Bacyinski et al., 2017).

Along with the changes noted in synapses, astrocytes are also sensitive to plasticity processes. Indeed, structural changes, based on the number of synapses covered by astrocyte processes, have been reported in the hippocampus, hypothalamus and cerebellum (Haber et al., 2006; Lippman et al., 2008; Theodosis et al., 2008). Structural imaging studies have shown that fine astrocyte processes have a high motility rate, changing their shape at a time-scale of minutes (Haber et al., 2006; Bernardinelli et al., 2014b; Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014), and can be influenced by learning paradigms, i.e., LTP protocols (Bernardinelli et al., 2014b; Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014). Moreover, after sustained afferent inputs, astrocytes display functional changes based on up/down regulation of membrane ion channels, and neurotransmitter receptors and transporters, showing similar plasticity phenomena to their neuronal counterparts. After using protocols that induce neuronal LTP, hippocampal astrocytes (Pita-Almenar et al., 2006, 2012) show enhanced ability to take up glutamate from adjacent synapses. In vivo, whisker stimulation that stimulates LTP in somatosensory cortical neurons also induces an increase of the expression of GLAST and GLT1 in cortical astrocytes (Genoud et al., 2006). In contrast, sustained depression of glutamate transporter currents and AMPA-mediated currents are expressed by Bergmann glia at low frequencies, which typically trigger LTP in Purkinje neurons (Bellamy and Ogden, 2006; Balakrishnan and Bellamy, 2009; Wang et al., 2014). Functional changes are seen not only in terms of neuron-to-astrocyte signaling, that is, the capability of astrocytes to sense and respond to neuronal activity, but also in terms of astrocyte-to-neuron communication. Thus, astrocytes from the ventrobasal (VB) thalamus are capable of adapting their actions on thalamic neurons when protocols for synaptic plasticity are applied to both the peripheral somatosensory and corticothalamic glutamatergic inputs (Pirttimaki et al., 2011). Repetitive stimulation of those pathways leads to a sustained increase in glutamate release from astrocytes, which persists for several minutes after the offset of the stimulus (ca. 60 min). Such enhanced gliotransmission affects the nearby thalamic neurons through NMDA receptor activation for long periods, boosting the time window for synaptic plasticity (Pirttimaki et al., 2011). These facts indicate that astrocytes are endowed with mechanisms that allow them to integrate synaptic information and store it for a period of time; therefore, astrocytes are able to memorize synaptic events that will have an impact on subsequent neuronal activity. Hence, astrocytic plasticity is an activity-dependent and input-specific process that is tightly controlled by synaptic activity. However, concomitantly neuronal signaling is dynamically modulated by the surrounding astrocytes, reinforcing the concept that brain function relies on interdependent neuron–astrocyte signaling.

To improve our understanding of brain circuits, it is essential to identify the properties and functions of each of their components. Neurons consist of several subtypes that are defined by their morphology, genetic profile, electrophysiological properties and input/target regions (Bota and Swanson, 2007). Recent data indicate that astrocytes are also a highly heterogeneous cell group with precise neural circuit specializations, especially when considering the wide range of transporters, membrane receptors, protein expression and functions that they exhibit (Zhang and Barres, 2010; Freeman and Rowitch, 2013; Khakh and Sofroniew, 2015). For example, a recent study on astrocyte diversity, which employed state-of-the-art optical, anatomical, electrophysiological, transcriptomic and proteomic approaches, revealed that dorsal striatal and hippocampal astrocytes (stratum radiatum) show significant differences in the sizes of their barium-sensitive K+ currents, as well as differences in the spontaneously and synaptically evoked G protein-coupled receptor-mediated Ca2+ signals (Chai et al., 2017). Interestingly, hippocampal and striatal astrocytes show different territory sizes, with the territory size being larger for striatal astrocytes, although hippocampal astrocytes display significantly greater and closer physical interactions with excitatory synapses than do astrocytes in the striatum (Chai et al., 2017). Striatal astrocytes are enriched for expression of the aldehyde dehydrogenase 5 family member A1 (Aldh5a1), a protein involved in GABA degradation, which seems highly relevant to a circuit mainly composed of GABAergic medium spiny neurons (Chai et al., 2017). Likewise, astrocytes from the dorsal striatum show functional selectivity in terms of neuronal cell-type activity by responding with variations in Ca2+ to the signaling of a particular type of medium spiny neuron (D1 or D2; Martín et al., 2015). By releasing glutamate, astrocytes activated by D1 or D2 neurons will specifically signal only the same type of neuron, implying that astrocyte–synapse signaling is largely cell-type specific (Martín et al., 2015). Compared with the striatum, hippocampal astrocytes are enriched for expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), Cx 43 and glutamine synthetase (Chai et al., 2017), which are likely involved in both glutamate metabolism and astrocyte connectivity in a circuit with strong oscillatory activity. Astrocytes from another dopaminergic nucleus, the ventral tegmental area (VTA), also show specific features that differentiate them from cortical and hippocampal astrocytes. VTA astrocytes show morphological differences, smaller somata and less tissue coverage by their processes, as well as electrical membrane property differences, and reduced expression of Kir4.1 channels (Xin et al., 2018). Furthermore, although gap junction coupling between astrocytes and oligodendrocytes is also present in the hippocampus and cortex, it is significant higher in the VTA region (Xin et al., 2018), which could impact the metabolic states of the dopaminergic neurons and their axons that exhibit tonic firing activity.

Remarkably, one of the molecular markers usually used to identify astrocytes, GFAP, shows different isoforms (α, β, γ, δ and κ) that are variably expressed in astrocytes across different brain regions (Middeldorp and Hol, 2011). Indeed, the cortex shows limited detectable levels of GFAP-labeled astrocytes, mostly located in layer 1 and in deep layers; as well as in the thalamus and other subcortical regions. In contrast, the hippocampus displays a high number of astrocytes expressing detectable levels of GFAP, which is considered to indicate astrocytic molecular diversity. Additionally, developmental and regional differences can be found in terms of the expression of the GLTs GLT-1 and GLAST, which show a dominant expression in different astrocyte populations (Regan et al., 2007). Hence, much effort has been expended in quantitative analysis of the molecular profiles of astrocytes in different brain regions. An integrated transcriptional analysis has been performed, taking advantage of some of the most common proteins expressed by astrocytes, such as GFAP, aquaporin-4, S100β, glutamine synthetase, GLT-1 and Aldh1L1 (Bachoo et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2016; John Lin et al., 2017; Morel et al., 2017). In this spirit, the astroglial mRNA expression patterns have been examined along the dorsoventral axis, including the cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens. These studies revealed opposite profiles between dorsal (cortex and hippocampus) and ventral (thalamus and hypothalamus) regions, i.e., the extracellular matrix protein, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) is selectively highly expressed in the hypothalamus/thalamus, while its levels are very low in the cortex/hippocampus (Morel et al., 2017). Additionally, astrocytes promote neurite growth and synaptic maturation of neurons from the same region, that is, subcortical neurons develop larger neurites when they are co-cultured with astrocytes from subcortical regions than with cortical astrocytes (Morel et al., 2017), which suggest that astrocyte modulation of synaptogenesis and synaptic activity is determined by neuronal cell type (Christopherson et al., 2005), but also specific brain areas (Morel et al., 2017).

It is important to establish whether astrocytes located at specific layers within a cortical circuit express different properties. Neurons display layer-specific subtypes that play particular roles in cortical circuitry. Therefore, it is possible that astrocytes show similar layer segregation to support and regulate such circuitry. A recent study on the somatosensory cortex found that, compared to astrocytes in deeper layers, astrocytes located in the upper layers differentially express several molecules related to morphogenesis, synaptic regulation and metabolism (Lanjakornsiripan et al., 2018). Astrocytes from layer 2/3 occupy a larger volume than do astrocytes at layers 4–6 and 1, likely due to greater astrocytic process arborization, thus supporting the notion that astrocytes in different layers possess distinct morphological features. Similarly, astrocytes located at layer 2/3 show more-extensive ensheathment of the synaptic clefts than do astrocytes in layer 6 (Lanjakornsiripan et al., 2018). Additionally, functional differences between astrocytes from different cortical layers have been described in vivo (Takata and Hirase, 2008). Astrocytes located in layer 1 show different spontaneous astrocytic Ca2+ dynamics than those from layer 2/3; for instance, the average frequency of somatic Ca2+ events is higher in layer 1 than in layer 2/3, and the magnitude of those Ca2+ responses differ (Takata and Hirase, 2008); however, astrocytic membrane potential was similar for all layers (Mishima and Hirase, 2010). Hence, the diverse territorial volume of cortical astrocytes and particular Ca2+ dynamics at different layers might differentially influence the surrounding synapses, yielding layer differences in astrocyte–synapse interactions, ultimately establishing functional heterogeneity through the modulation of glutamate/GABA clearance and the release of active substances that affect synaptic transmission and plasticity.

Surprisingly, such layer-specific distribution is dictated by neuronal migration during development. Indeed, the layer-specific orientation of neocortical astrocytes depends on reelin (Lanjakornsiripan et al., 2018), a protein secreted predominantly from Cajal-Retzius neurons located in layer 1 that regulates the migration of cortical neurons (D’Arcangelo et al., 1995; Katsuyama and Terashima, 2009). This indicates that the existence of neuronal layers is a requirement for establishing layer-specific features of mature cortical astrocytes (Lanjakornsiripan et al., 2018). Furthermore, signaling of the neuron-derived sonic hedgehog (Shh) protein also regulates the molecular and functional profile of astrocytes across different brain regions (Farmer et al., 2016). Hence, Shh signaling in cerebellar Bergman glia promotes glutamatergic signals, enhancing expression of GLTs (GLAST) and AMPA receptors; additionally, potassium homeostasis (Kir4.1) might be related to the dense glutamatergic inputs onto Purkinje cells in the molecular layer. In contrast, cortical and hippocampal astrocytes use Shh signaling for preferential regulation of Kir4.1 channels (Farmer et al., 2016), which are related to potassium buffering. Therefore, such astrocyte regionalization seems to be dictated not only by endogenous astrocytic molecular programs, but also by neuronal signals during development. Thus, neuron–astrocyte signaling dynamically cooperates to generate astrocyte heterogeneity, and ultimately guarantees that mature astrocytes are appropriately specialized to fit the requirements of particular neural circuits.

It is important to note that astrocyte diversity might get even more complex across species. Critical molecular and anatomical differences have been found between rodent and human astrocytes (Oberheim et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2016; Vasile et al., 2017). As an example, while a single rodent astrocyte can cover up to 120,000 synapses, a human astrocyte might cover from ca. 270,000 to 2 million synapses within a single domain (Bushong et al., 2002; Oberheim et al., 2009). Consequently, it is tempting to speculate that astrocytic changes in channel or transporter expression, GTs or extension of astrocytic domains will deeply impact synapses. Astrocytes by enhancing or decreasing synaptic strength would regulate the operational capabilities of human neuronal networks, and might contribute to the higher functions of the human brain.

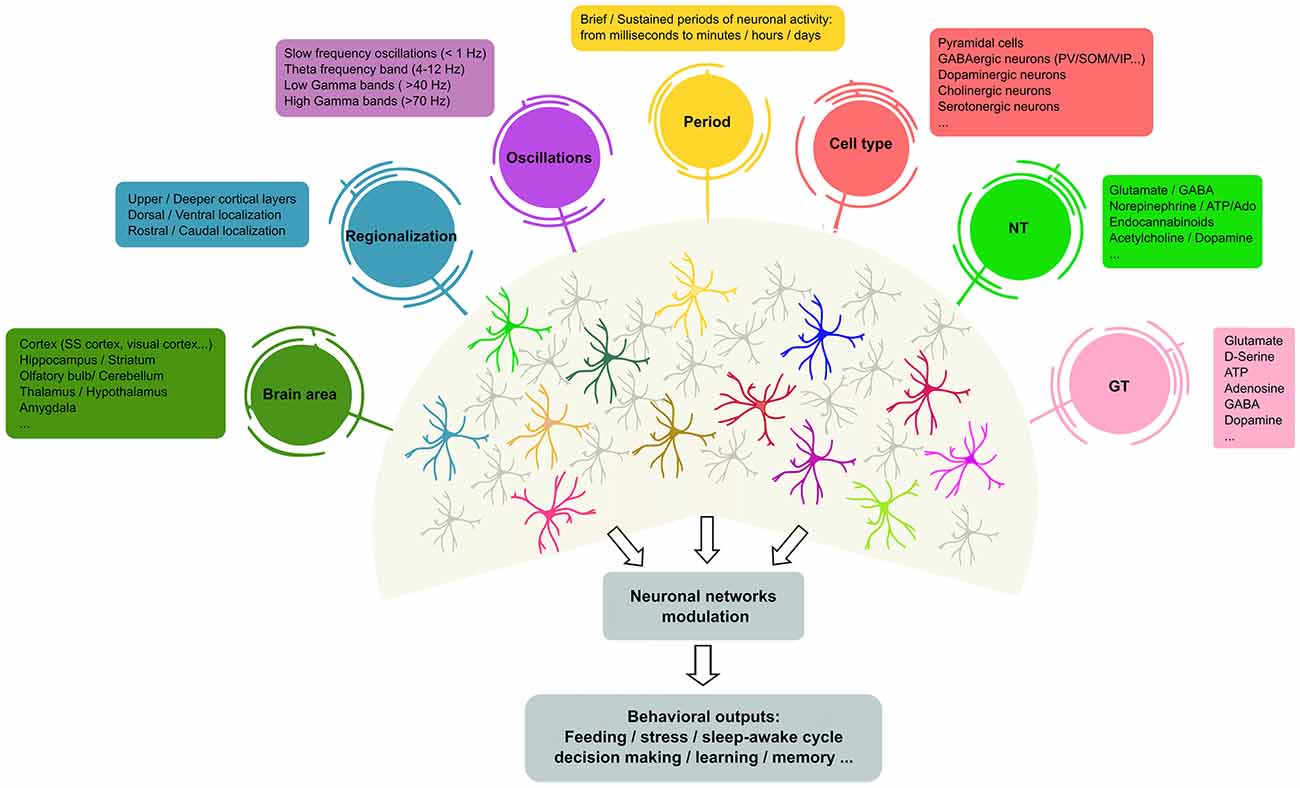

Collectively, these recent data indicate that astrocytes are not a homogeneous cell type, but rather are circuit-specialized cells that allow for focused astrocyte–synapse signaling, with critical consequences for information-coding in particular layers, circuits and regions in the adult brain (see Figure 1). Such astrocyte heterogeneity also provides new variables to the operational codes used by neural circuits that govern complex behavioral responses in health and disease. Therefore, our current knowledge of astrocyte physiology and its impact in synaptic function supports the idea that neuron–glia networks are complex systems that are regionally regulated, with particular structural and functional features.

Figure 1. Heterogeneity of astrocyte–neuron networks. Astrocytes are able to respond to different NTs, cell types in different brain areas and under diverse patterns of stimulation. In turn, astrocytes modulate the activity of ion channels and neurotransmitter transporters in their membranes, but also release different active substances (so-called GTs, e.g., glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), adenosine and D-serine, among others) that contribute to shape neuronal activity. However, it remains unclear whether the same or different astrocyte subtypes mediate these differential effects. The scheme illustrates recent evidence of the molecular and functional diversity of astrocytes that may underlie the outcomes of brain activity. In this context, single astrocytes can be affected by more than one physiological feature (represented as colored circles that connect to astrocytes), or subsets of astrocytes may show preferential links with particular physiological features, suggesting the existence of different astrocyte populations that exhibit specific properties (astrocyte color code). NTs, neurotransmitters; GTs, gliotransmitters; SS, somatosensory; PV, parvalbumin positive cells; SOM, somatostatin positive cells; VIP, vasoactive-intestinal peptide.

The aim of this review article was to provide an update on the central components that underlie the heterogeneity of astrocyte–neuron signaling, which supports the wide range of functional consequences of astrocytes on synaptic transmission and behavior. Current data show that astrocytes, via expression of ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, subcellular Ca2+ dynamics, GTs release and structural changes of the cell body and fine processes, critically contribute to shape neuronal transmission. However, the full scenario of what particular features trigger molecular, structural and functional changes in astrocytes is unknown. Yet, future studies applying new approaches and methodology are required to reveal the precise mechanisms that rule astrocyte heterogeneity in different brain regions, which help to address some open questions in the field: (i) which features of astrocyte physiology are driven by neuronal activity and which others are inherent to astrocytes? (ii) what are the boundaries of brain homeostasis? That is, to what extent astrocytes can adapt themselves to neuronal changes to keep brain homeostasis; and vice versa, to what extent synapses can adapt themselves to astrocytic changes. These aims emphasize whether it is considered that altered balance of astrocyte–neuronal signaling might underlie numerous neuropathological states (AD, Huntington disease, epilepsy, major depression; for review see Lundgaard et al., 2014; Chung et al., 2015b; Koyama, 2015). Therefore, a deeper knowledge of astrocyte physiology and astrocyte–neuron networks is necessary to reveal the dynamic and complex organization of the brain circuits underlying animal behavior in health and disease.

SM, CG-A and GP wrote the article. All authors discussed the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the PhD fellowship program (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, MINECO, BES-2014-067594) to SM; BES-2017-080303 to CG-A; and MINECO grant (BFU2016-75107-P) to GP.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Dr. E. Martin and M. Navarrete for helpful comments.

Allen, N. J., and Eroglu, C. (2017). Cell biology of astrocyte-synapse interactions. Neuron 96, 697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.056

Almad, A., and Maragakis, N. J. (2018). A stocked toolbox for understanding the role of astrocytes in disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 351–362. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0010-2

Andrade-Talavera, Y., Duque-Feria, P., Paulsen, O., and Rodriguez-Moreno, A. (2016). Presynaptic spike timing-dependent long-term depression in the mouse hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex 26, 3637–3654. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw172

Angulo, M. C., Kozlov, A. S., Charpak, S., and Audinat, E. (2004). Glutamate released from glial cells synchronizes neuronal activity in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 24, 6920–6927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0473-04.2004

Araque, A., Carmignoto, G., Haydon, P. G., Oliet, S. H., Robitaille, R., and Volterra, A. (2014). Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron 81, 728–739. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.007

Araque, A., Li, N., Doyle, R. T., and Haydon, P. G. (2000). SNARE protein-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 20, 666–673. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.20-02-00666.2000

Araque, A., Parpura, V., Sanzgiri, R. P., and Haydon, P. G. (1999). Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends Neurosci. 22, 208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6

Bachoo, R. M., Kim, R. S., Ligon, K. L., Maher, E. A., Brennan, C., Billings, N., et al. (2004). Molecular diversity of astrocytes with implications for neurological disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 8384–8389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402140101

Bacyinski, A., Xu, M., Wang, W., and Hu, J. (2017). The paravascular pathway for brain waste clearance: current understanding, significance and controversy. Front. Neuroanat. 11:101. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00101

Balakrishnan, S., and Bellamy, T. C. (2009). Depression of parallel and climbing fiber transmission to Bergmann glia is input specific and correlates with increased precision of synaptic transmission. Glia 57, 393–401. doi: 10.1002/glia.20768

Bazargani, N., and Attwell, D. (2016). Astrocyte calcium signaling: the third wave. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.4201

Beattie, E. C., Stellwagen, D., Morishita, W., Bresnahan, J. C., Ha, B. K., Von Zastrow, M., et al. (2002). Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFα. Science 295, 2282–2285. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859

Beenhakker, M. P., and Huguenard, J. R. (2010). Astrocytes as gatekeepers of GABAB receptor function. J. Neurosci. 30, 15262–15276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3243-10.2010

Bekar, L. K., He, W., and Nedergaard, M. (2008). Locus coeruleus α-adrenergic-mediated activation of cortical astrocytes in vivo. Cereb. Cortex 18, 2789–2795. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn040

Bellamy, T. C., and Ogden, D. (2006). Long-term depression of neuron to glial signalling in rat cerebellar cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04588.x

Ben Haim, L., and Rowitch, D. H. (2017). Functional diversity of astrocytes in neural circuit regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 31–41. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.159

Bergles, D. E., and Jahr, C. E. (1997). Synaptic activation of glutamate transporters in hippocampal astrocytes. Neuron 19, 1297–1308. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80420-1

Bernardinelli, Y., Nikonenko, I., and Muller, D. (2014a). Structural plasticity: mechanisms and contribution to developmental psychiatric disorders. Front. Neuroanat. 8:123. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00123

Bernardinelli, Y., Randall, J., Janett, E., Nikonenko, I., König, S., Jones, E. V., et al. (2014b). Activity-dependent structural plasticity of perisynaptic astrocytic domains promotes excitatory synapse stability. Curr. Biol. 24, 1679–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.025

Bezzi, P., Gundersen, V., Galbete, J. L., Seifert, G., Steinhäuser, C., Pilati, E., et al. (2004). Astrocytes contain a vesicular compartment that is competent for regulated exocytosis of glutamate. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 613–620. doi: 10.1038/nn1246

Boddum, K., Jensen, T. P., Magloire, V., Kristiansen, U., Rusakov, D. A., Pavlov, I., et al. (2016). Astrocytic GABA transporter activity modulates excitatory neurotransmission. Nat. Commun. 7:13572. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13572

Bohmbach, K., Schwarz, M. K., Schoch, S., and Henneberger, C. (2018). The structural and functional evidence for vesicular release from astrocytes in situ. Brain Res. Bull. 136, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.01.015

Boisvert, M. M., Erikson, G. A., Shokhirev, M. N., and Allen, N. J. (2018). The aging astrocyte transcriptome from multiple regions of the mouse brain. Cell Rep. 22, 269–285. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.039

Bonansco, C., Couve, A., Perea, G., Ferradas, C. A., Roncagliolo, M., and Fuenzalida, M. (2011). Glutamate released spontaneously from astrocytes sets the threshold for synaptic plasticity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 33, 1483–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07631.x

Borden, L. A. (1996). GABA transporter heterogeneity: pharmacology and cellular localization. Neurochem. Int. 29, 335–356. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(95)00158-1

Bota, M., and Swanson, L. W. (2007). The neuron classification problem. Brain Res. Rev. 56, 79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.005

Bowser, D. N., and Khakh, B. S. (2007). Vesicular ATP is the predominant cause of intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 129, 485–491. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709780

Brancaccio, M., Patton, A. P., Chesham, J. E., Maywood, E. S., and Hastings, M. H. (2017). Astrocytes control circadian timekeeping in the suprachiasmatic nucleus via glutamatergic signaling. Neuron 93, 1420.e5–1435.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.030

Brockett, A. T., Kane, G. A., Monari, P. K., Briones, B. A., Vigneron, P. A., Barber, G. A., et al. (2018). Evidence supporting a role for astrocytes in the regulation of cognitive flexibility and neuronal oscillations through the Ca2+ binding protein S100β. PLoS One 13:e0195726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195726

Brown, R. E., Basheer, R., McKenna, J. T., Strecker, R. E., and McCarley, R. W. (2012). Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1087–1187. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2011

Bushong, E. A., Martone, M. E., Jones, Y. Z., and Ellisman, M. H. (2002). Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J. Neurosci. 22, 183–192. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.22-01-00183.2002

Buzsáki, G., and Chrobak, J. J. (2005). Synaptic plasticity and self-organization in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1418–1420. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1418

Chai, H., Diaz-Castro, B., Shigetomi, E., Monte, E., Octeau, J. C., Yu, X., et al. (2017). Neural circuit-specialized astrocytes: transcriptomic, proteomic, morphological and functional evidence. Neuron 95, 531.e9–549.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.029

Charvériat, M., Naus, C. C., Leybaert, L., Sáez, J. C., and Giaume, C. (2017). Connexin-dependent neuroglial networking as a new therapeutic target. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:174. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00174

Chatton, J. Y., Magistretti, P. J., and Barros, L. F. (2016). Sodium signaling and astrocyte energy metabolism. Glia 64, 1667–1676. doi: 10.1002/glia.22971

Chaudhry, F. A., Lehre, K. P., van Lookeren Campagne, M., Ottersen, O. P., Danbolt, N. C., and Storm-Mathisen, J. (1995). Glutamate transporters in glial plasma membranes: highly differentiated localizations revealed by quantitative ultrastructural immunocytochemistry. Neuron 15, 711–720. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90158-2

Chen, N., Sugihara, H., Sharma, J., Perea, G., Petravicz, J., Le, C., et al. (2012). Nucleus basalis-enabled stimulus-specific plasticity in the visual cortex is mediated by astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 109, E2832–E2841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206557109

Chen, J., Tan, Z., Zeng, L., Zhang, X., He, Y., Gao, W., et al. (2013). Heterosynaptic long-term depression mediated by ATP released from astrocytes. Glia 61, 178–191. doi: 10.1002/glia.22425

Christopherson, K. S., Ullian, E. M., Stokes, C. C., Mullowney, C. E., Hell, J. W., Agah, A., et al. (2005). Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis. Cell 120, 421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.020

Chung, W. S., Allen, N. J., and Eroglu, C. (2015a). Astrocytes control synapse formation, function and elimination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a020370. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020370

Chung, W. S., Welsh, C. A., Barres, B. A., and Stevens, B. (2015b). Do glia drive synaptic and cognitive impairment in disease? Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1539–1545. doi: 10.1038/nn.4142

Clasadonte, J., Scemes, E., Wang, Z., Boison, D., and Haydon, P. G. (2017). Connexin 43-mediated astroglial metabolic networks contribute to the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle. Neuron 95, 1365.e5–1380.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.022

Covelo, A., and Araque, A. (2018). Neuronal activity determines distinct gliotransmitter release from a single astrocyte. Elife 7:e32237. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32237

D’Ambrosio, R., Gordon, D. S., and Winn, H. R. (2002). Differential role of KIR channel and Na+/K+-pump in the regulation of extracellular K+ in rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 87–102. doi: 10.1152/jn.00240.2001

D’Arcangelo, G., Miao, G. G., Chen, S. C., Soares, H. D., Morgan, J. I., and Curran, T. (1995). A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 374, 719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0

Danbolt, N. C. (2001). Glutamate uptake. Prog. Neurobiol. 65, 1–105. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00067-8

De Pittà, M., and Brunel, N. (2016). Modulation of synaptic plasticity by glutamatergic gliotransmission: a modeling study. Neural Plast. 2016:7607924. doi: 10.1155/2016/7607924

Di Castro, M. A., Chuquet, J., Liaudet, N., Bhaukaurally, K., Santello, M., Bouvier, D., et al. (2011). Local Ca2+ detection and modulation of synaptic release by astrocytes. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2929

Doengi, M., Hirnet, D., Coulon, P., Pape, H. C., Deitmer, J. W., and Lohr, C. (2009). GABA uptake-dependent Ca2+ signaling in developing olfactory bulb astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 17570–17575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809513106

Dossi, E., Vasile, F., and Rouach, N. (2018). Human astrocytes in the diseased brain. Brain Res. Bull. 136, 139–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.02.001

Duan, S., Anderson, C. M., Keung, E. C., Chen, Y., Chen, Y., and Swanson, R. A. (2003). P2X7 receptor-mediated release of excitatory amino acids from astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 23, 1320–1328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01320.2003

Eroglu, C., and Barres, B. A. (2010). Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature 468, 223–231. doi: 10.1038/nature09612

Farmer, W. T., Abrahamsson, T., Chierzi, S., Lui, C., Zaelzer, C., Jones, E. V., et al. (2016). Neurons diversify astrocytes in the adult brain through sonic hedgehog signaling. Science 351, 849–854. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3103

Farmer, W. T., and Murai, K. (2017). Resolving astrocyte heterogeneity in the CNS. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:300. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00300

Fellin, T., Halassa, M. M., Terunuma, M., Succol, F., Takano, H., Frank, M., et al. (2009). Endogenous nonneuronal modulators of synaptic transmission control cortical slow oscillations in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 15037–15042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906419106

Fellin, T., Pascual, O., Gobbo, S., Pozzan, T., Haydon, P. G., and Carmignoto, G. (2004). Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron 43, 729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011

Fiacco, T. A., and McCarthy, K. D. (2018). Multiple lines of evidence indicate that gliotransmission does not occur under physiological conditions. J. Neurosci. 38, 3–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0016-17.2017

Freeman, M. R., and Rowitch, D. H. (2013). Evolving concepts of gliogenesis: a look way back and ahead to the next 25 years. Neuron 80, 613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.034

Fuente-Martin, E., Garcia-Caceres, C., Morselli, E., Clegg, D. J., Chowen, J. A., Finan, B., et al. (2013). Estrogen, astrocytes and the neuroendocrine control of metabolism. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 14, 331–338. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9263-7

Gadea, A., and López-Colomé, A. M. (2001a). Glial transporters for glutamate, glycine and GABA I. Glutamate transporters. J. Neurosci. Res. 63, 453–460. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1039

Gadea, A., and López-Colomé, A. M. (2001b). Glial transporters for glutamate, glycine and GABA: II. GABA transporters. J. Neurosci. Res. 63, 461–468. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1040

García-Cáceres, C., Quarta, C., Varela, L., Gao, Y., Gruber, T., Legutko, B., et al. (2016). Astrocytic insulin signaling couples brain glucose uptake with nutrient availability. Cell 166, 867–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.028

García-Marqués, J., and López-Mascaraque, L. (2013). Clonal identity determines astrocyte cortical heterogeneity. Cereb. Cortex 23, 1463–1472. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs134

Genoud, C., Quairiaux, C., Steiner, P., Hirling, H., Welker, E., and Knott, G. W. (2006). Plasticity of astrocytic coverage and glutamate transporter expression in adult mouse cortex. PLoS Biol. 4:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040343

Giaume, C., Koulakoff, A., Roux, L., Holcman, D., and Rouach, N. (2010). Astroglial networks: a step further in neuroglial and gliovascular interactions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 87–99. doi: 10.1038/nrn2757

Gómez-Gonzalo, M., Navarrete, M., Perea, G., Covelo, A., Martín-Fernández, M., Shigemoto, R., et al. (2015). Endocannabinoids induce lateral long-term potentiation of transmitter release by stimulation of gliotransmission. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3699–3712. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu231

Goodrich, G. S., Kabakov, A. Y., Hameed, M. Q., Dhamne, S. C., Rosenberg, P. A., and Rotenberg, A. (2013). Ceftriaxone treatment after traumatic brain injury restores expression of the glutamate transporter, GLT-1, reduces regional gliosis and reduces post-traumatic seizures in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 30, 1434–1441. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2712

Haber, M., Zhou, L., and Murai, K. K. (2006). Cooperative astrocyte and dendritic spine dynamics at hippocampal excitatory synapses. J. Neurosci. 26, 8881–8891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1302-06.2006

Haj-Yasein, N. N., Jensen, V., Vindedal, G. F., Gundersen, G. A., Klungland, A., Ottersen, O. P., et al. (2011a). Evidence that compromised K+ spatial buffering contributes to the epileptogenic effect of mutations in the human Kir4.1 gene (KCNJ10). Glia 59, 1635–1642. doi: 10.1002/glia.21205

Haj-Yasein, N. N., Vindedal, G. F., Eilert-Olsen, M., Gundersen, G. A., Skare, O., Laake, P., et al. (2011b). Glial-conditional deletion of aquaporin-4 (Aqp4) reduces blood-brain water uptake and confers barrier function on perivascular astrocyte endfeet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 17815–17820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110655108

Halassa, M. M., Florian, C., Fellin, T., Munoz, J. R., Lee, S. Y., Abel, T., et al. (2009). Astrocytic modulation of sleep homeostasis and cognitive consequences of sleep loss. Neuron 61, 213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.024

Halnes, G., Ostby, I., Pettersen, K. H., Omholt, S. W., and Einevoll, G. T. (2013). Electrodiffusive model for astrocytic and neuronal ion concentration dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9:e1003386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003386

Hamilton, N. B., and Attwell, D. (2010). Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrn2803

Han, X., Chen, M., Wang, F., Windrem, M., Wang, S., Shanz, S., et al. (2013). Forebrain engraftment by human glial progenitor cells enhances synaptic plasticity and learning in adult mice. Cell Stem Cell 12, 342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.015

Harris, A. L. (2007). Connexin channel permeability to cytoplasmic molecules. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 94, 120–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.011

Heller, J. P., and Rusakov, D. A. (2015). Morphological plasticity of astroglia: understanding synaptic microenvironment. Glia 63, 2133–2151. doi: 10.1002/glia.22821

Henneberger, C., Papouin, T., Oliet, S. H., and Rusakov, D. A. (2010). Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature 463, 232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08673

Herculano-Houzel, S., Catania, K., Manger, P. R., and Kaas, J. H. (2015). Mammalian brains are made of these: a dataset of the numbers and densities of neuronal and nonneuronal cells in the brain of glires, primates, scandentia, eulipotyphlans, afrotherians and artiodactyls and their relationship with body mass. Brain Behav. Evol. 86, 145–163. doi: 10.1159/000437413

Hertz, L., Xu, J., Song, D., Yan, E., Gu, L., and Peng, L. (2013). Astrocytic and neuronal accumulation of elevated extracellular K+ with a 2/3 K+/Na+ flux ratio-consequences for energy metabolism, osmolarity and higher brain function. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 7:114. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2013.00114

Houades, V., Koulakoff, A., Ezan, P., Seif, I., and Giaume, C. (2008). Gap junction-mediated astrocytic networks in the mouse barrel cortex. J. Neurosci. 28, 5207–5217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5100-07.2008

Huang, Y. H., Sinha, S. R., Tanaka, K., Rothstein, J. D., and Bergles, D. E. (2004). Astrocyte glutamate transporters regulate metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated excitation of hippocampal interneurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 4551–4559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5217-03.2004

Jennings, A., Tyurikova, O., Bard, L., Zheng, K., Semyanov, A., Henneberger, C., et al. (2017). Dopamine elevates and lowers astroglial Ca2+ through distinct pathways depending on local synaptic circuitry. Glia 65, 447–459. doi: 10.1002/glia.23103

Jiang, R., Diaz-Castro, B., Looger, L. L., and Khakh, B. S. (2016). Dysfunctional calcium and glutamate signaling in striatal astrocytes from Huntington’s disease model mice. J. Neurosci. 36, 3453–3470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3693-15.2016

Jiang, Q., Zhang, L., Ding, G., Davoodi-Bojd, E., Li, Q., Li, L., et al. (2017). Impairment of the glymphatic system after diabetes. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 37, 1326–1337. doi: 10.1177/0271678x16654702

John Lin, C. C., Yu, K., Hatcher, A., Huang, T. W., Lee, H. K., Carlson, J., et al. (2017). Identification of diverse astrocyte populations and their malignant analogs. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 396–405. doi: 10.1038/nn.4493

Jourdain, P., Bergersen, L. H., Bhaukaurally, K., Bezzi, P., Santello, M., Domercq, M., et al. (2007). Glutamate exocytosis from astrocytes controls synaptic strength. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 331–339. doi: 10.1038/nn1849

Kano, M. (2014). Control of synaptic function by endocannabinoid-mediated retrograde signaling. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 90, 235–250. doi: 10.2183/pjab.90.235

Karus, C., Mondragão, M. A., Ziemens, D., and Rose, C. R. (2015). Astrocytes restrict discharge duration and neuronal sodium loads during recurrent network activity. Glia 63, 936–957. doi: 10.1002/glia.22793

Katsuyama, Y., and Terashima, T. (2009). Developmental anatomy of reeler mutant mouse. Dev. Growth Differ. 51, 271–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169x.2009.01102.x

Khakh, B. S., and Sofroniew, M. V. (2015). Diversity of astrocyte functions and phenotypes in neural circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 942–952. doi: 10.1038/nn.4043

Khan, Z. U., Koulen, P., Rubinstein, M., Grandy, D. K., and Goldman-Rakic, P. S. (2001). An astroglia-linked dopamine D2-receptor action in prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 98, 1964–1969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1964

Kim, J. G., Suyama, S., Koch, M., Jin, S., Argente-Arizon, P., Argente, J., et al. (2014). Leptin signaling in astrocytes regulates hypothalamic neuronal circuits and feeding. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 908–910. doi: 10.1038/nn.3725

Kirischuk, S., Kettenmann, H., and Verkhratsky, A. (2007). Membrane currents and cytoplasmic sodium transients generated by glutamate transport in Bergmann glial cells. Pflugers Arch. 454, 245–252. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0207-5

Koyama, Y. (2015). Functional alterations of astrocytes in mental disorders: pharmacological significance as a drug target. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:261. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00261

Kuffler, S. W., and Nicholls, J. G. (1966). The physiology of neuroglial cells. Ergeb. Physiol. 57, 1–90. doi: 10.1007/bfb0116991

Kumar, N. M., and Gilula, N. B. (1996). The gap junction communication channel. Cell 84, 381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81282-9

Kunzelmann, P., Schröder, W., Traub, O., Steinhäuser, C., Dermietzel, R., and Willecke, K. (1999). Late onset and increasing expression of the gap junction protein connexin30 in adult murine brain and long-term cultured astrocytes. Glia 25, 111–119. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(19990115)25:2<111::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-i

Lanjakornsiripan, D., Pior, B. J., Kawaguchi, D., Furutachi, S., Tahara, T., Katsuyama, Y., et al. (2018). Layer-specific morphological and molecular differences in neocortical astrocytes and their dependence on neuronal layers. Nat. Commun. 9:1623. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03940-3

Larsen, B. R., Assentoft, M., Cotrina, M. L., Hua, S. Z., Nedergaard, M., Kaila, K., et al. (2014). Contributions of the Na+/K+-ATPase, NKCC1 and Kir4.1 to hippocampal K+ clearance and volume responses. Glia 62, 608–622. doi: 10.1002/glia.22629

Lee, S., Yoon, B. E., Berglund, K., Oh, S. J., Park, H., Shin, H. S., et al. (2010). Channel-mediated tonic GABA release from glia. Science 330, 790–796. doi: 10.1126/science.1184334

Lehre, K. P., and Danbolt, N. C. (1998). The number of glutamate transporter subtype molecules at glutamatergic synapses: chemical and stereological quantification in young adult rat brain. J. Neurosci. 18, 8751–8757. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.18-21-08751.1998

Lehre, K. P., Davanger, S., and Danbolt, N. C. (1997). Localization of the glutamate transporter protein GLAST in rat retina. Brain Res. 744, 129–137. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01022-0

Liebner, S., Dijkhuizen, R. M., Reiss, Y., Plate, K. H., Agalliu, D., and Constantin, G. (2018). Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 311–336. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1815-1

Lippman, J. J., Lordkipanidze, T., Buell, M. E., Yoon, S. O., and Dunaevsky, A. (2008). Morphogenesis and regulation of Bergmann glial processes during Purkinje cell dendritic spine ensheathment and synaptogenesis. Glia 56, 1463–1477. doi: 10.1002/glia.20712

Lundgaard, I., Lu, M. L., Yang, E., Peng, W., Mestre, H., Hitomi, E., et al. (2017). Glymphatic clearance controls state-dependent changes in brain lactate concentration. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 37, 2112–2124. doi: 10.1177/0271678x16661202

Lundgaard, I., Osório, M. J., Kress, B. T., Sanggaard, S., and Nedergaard, M. (2014). White matter astrocytes in health and disease. Neuroscience 276, 161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.050

Mariotti, L., Losi, G., Lia, A., Melone, M., Chiavegato, A., Gómez-Gonzalo, M., et al. (2018). Interneuron-specific signaling evokes distinctive somatostatin-mediated responses in adult cortical astrocytes. Nat. Commun. 9:82. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02642-6

Mariotti, L., Losi, G., Sessolo, M., Marcon, I., and Carmignoto, G. (2016). The inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA evokes long-lasting Ca2+ oscillations in cortical astrocytes. Glia 64, 363–373. doi: 10.1002/glia.22933

Martín, R., Bajo-Graáeras, R., Moratalla, R., Perea, G., and Araque, A. (2015). Circuit-specific signaling in astrocyte-neuron networks in basal ganglia pathways. Science 349, 730–734. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa7945

Martin-Fernandez, M., Jamison, S., Robin, L. M., Zhao, Z., Martin, E. D., Aguilar, J., et al. (2017). Synapse-specific astrocyte gating of amygdala-related behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1540–1548. doi: 10.1038/nn.4649

Matthias, K., Kirchhoff, F., Seifert, G., Hüttmann, K., Matyash, M., Kettenmann, H., et al. (2003). Segregated expression of AMPA-type glutamate receptors and glutamate transporters defines distinct astrocyte populations in the mouse hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 23, 1750–1758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01750.2003

Matyash, V., and Kettenmann, H. (2010). Heterogeneity in astrocyte morphology and physiology. Brain Res. Rev. 63, 2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.12.001

Middeldorp, J., and Hol, E. M. (2011). GFAP in health and disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 93, 421–443. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.005

Min, R., and Nevian, T. (2012). Astrocyte signaling controls spike timing-dependent depression at neocortical synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 746–753. doi: 10.1038/nn.3075

Min, R., Santello, M., and Nevian, T. (2012). The computational power of astrocyte mediated synaptic plasticity. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 6:93. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2012.00093

Mishima, T., and Hirase, H. (2010). In vivo intracellular recording suggests that gray matter astrocytes in mature cerebral cortex and hippocampus are electrophysiologically homogeneous. J. Neurosci. 30, 3093–3100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5065-09.2010

Moheet, A., Mangia, S., and Seaquist, E. R. (2015). Impact of diabetes on cognitive function and brain structure. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1353, 60–71. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12807

Montagnese, C., Poulain, D. A., Vincent, J. D., and Theodosis, D. T. (1988). Synaptic and neuronal-glial plasticity in the adult oxytocinergic system in response to physiological stimuli. Brain Res. Bull. 20, 681–692. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90078-0

Morel, L., Chiang, M. S. R., Higashimori, H., Shoneye, T., Iyer, L. K., Yelick, J., et al. (2017). Molecular and functional properties of regional astrocytes in the adult brain. J. Neurosci. 37, 8706–8717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3956-16.2017

Morquette, P., Verdier, D., Kadala, A., Féthière, J., Philippe, A. G., Robitaille, R., et al. (2015). An astrocyte-dependent mechanism for neuronal rhythmogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 844–854. doi: 10.1038/nn.4013

Murphy-Royal, C., Dupuis, J. P., Varela, J. A., Panatier, A., Pinson, B., Baufreton, J., et al. (2015). Surface diffusion of astrocytic glutamate transporters shapes synaptic transmission. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 219–226. doi: 10.1038/nn.3901

Nagelhus, E. A., Horio, Y., Inanobe, A., Fujita, A., Haug, F. M., Nielsen, S., et al. (1999). Immunogold evidence suggests that coupling of K+ siphoning and water transport in rat retinal Muller cells is mediated by a coenrichment of Kir4.1 and AQP4 in specific membrane domains. Glia 26, 47–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199903)26:1<47::aid-glia5>3.0.co;2-5

Nagy, J. I., Patel, D., Ochalski, P. A., and Stelmack, G. L. (1999). Connexin30 in rodent, cat and human brain: selective expression in gray matter astrocytes, co-localization with connexin43 at gap junctions and late developmental appearance. Neuroscience 88, 447–468. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00191-2

Nagy, J. I., and Rash, J. E. (2000). Connexins and gap junctions of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the CNS. Brain Res. Rev. 32, 29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00066-1

Navarrete, M., and Araque, A. (2010). Endocannabinoids potentiate synaptic transmission through stimulation of astrocytes. Neuron 68, 113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.043

Navarrete, M., Perea, G., Fernandez De Sevilla, D., Gómez-Gonzalo, M., Núñez, A., Martín, E. D., et al. (2012). Astrocytes mediate in vivo cholinergic-induced synaptic plasticity. PLoS Biol. 10:e1001259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001259

Newman, E. A. (1984). Regional specialization of retinal glial cell membrane. Nature 309, 155–157. doi: 10.1038/309155a0

Newman, E. A. (1993). Inward-rectifying potassium channels in retinal glial (Muller) cells. J. Neurosci. 13, 3333–3345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03333.1993

Nimmerjahn, A., and Bergles, D. E. (2015). Large-scale recording of astrocyte activity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 32, 95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.01.015

Oberheim, N. A., Takano, T., Han, X., He, W., Lin, J. H., Wang, F., et al. (2009). Uniquely hominid features of adult human astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 29, 3276–3287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4707-08.2009

Ogata, K., and Kosaka, T. (2002). Structural and quantitative analysis of astrocytes in the mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience 113, 221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00041-6

Oliveira, J. F., Sardinha, V. M., Guerra-Gomes, S., Araque, A., and Sousa, N. (2015). Do stars govern our actions? Astrocyte involvement in rodent behavior. Trends Neurosci. 38, 535–549. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.07.006

Panatier, A., Theodosis, D. T., Mothet, J. P., Touquet, B., Pollegioni, L., Poulain, D. A., et al. (2006). Glia-derived D-serine controls NMDA receptor activity and synaptic memory. Cell 125, 775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.051

Panatier, A., Vallée, J., Haber, M., Murai, K. K., Lacaille, J. C., and Robitaille, R. (2011). Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell 146, 785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.022

Pannasch, U., Vargová, L., Reingruber, J., Ezan, P., Holcman, D., Giaume, C., et al. (2011). Astroglial networks scale synaptic activity and plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 8467–8472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016650108

Papouin, T., Dunphy, J. M., Tolman, M., Dineley, K. T., and Haydon, P. G. (2017). Septal cholinergic neuromodulation tunes the astrocyte-dependent gating of hippocampal NMDA receptors to wakefulness. Neuron 94, 840.e7–854.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.021

Parpura, V., and Zorec, R. (2010). Gliotransmission: exocytotic release from astrocytes. Brain Res. Rev. 63, 83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.11.008

Paukert, M., Agarwal, A., Cha, J., Doze, V. A., Kang, J. U., and Bergles, D. E. (2014). Norepinephrine controls astroglial responsiveness to local circuit activity. Neuron 82, 1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.038

Perea, G., and Araque, A. (2007). Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science 317, 1083–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1144640

Perea, G., Gómez, R., Mederos, S., Covelo, A., Ballesteros, J. J., Schlosser, L., et al. (2016). Activity-dependent switch of GABAergic inhibition into glutamatergic excitation in astrocyte-neuron networks. Elife 5:e20362. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20362

Perea, G., Navarrete, M., and Araque, A. (2009). Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci. 32, 421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001

Perea, G., Sur, M., and Araque, A. (2014). Neuron-glia networks: integral gear of brain function. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:378. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00378

Perez-Alvarez, A., Navarrete, M., Covelo, A., Martin, E. D., and Araque, A. (2014). Structural and functional plasticity of astrocyte processes and dendritic spine interactions. J. Neurosci. 34, 12738–12744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2401-14.2014

Petrelli, F., Dallérac, G., Pucci, L., Cali, C., Zehnder, T., Sultan, S., et al. (2018). Dysfunction of homeostatic control of dopamine by astrocytes in the developing prefrontal cortex leads to cognitive impairments. Mol. Psychiatry doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0226-y [Epub ahead of print].

Pirttimaki, T. M., Hall, S. D., and Parri, H. R. (2011). Sustained neuronal activity generated by glial plasticity. J. Neurosci. 31, 7637–7647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5783-10.2011

Pita-Almenar, J. D., Collado, M. S., Colbert, C. M., and Eskin, A. (2006). Different mechanisms exist for the plasticity of glutamate reuptake during early long-term potentiation (LTP) and late LTP. J. Neurosci. 26, 10461–10471. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2579-06.2006

Pita-Almenar, J. D., Zou, S., Colbert, C. M., and Eskin, A. (2012). Relationship between increase in astrocytic GLT-1 glutamate transport and late-LTP. Learn. Mem. 19, 615–626. doi: 10.1101/lm.023259.111

Plog, B. A., and Nedergaard, M. (2018). The glymphatic system in central nervous system health and disease: past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 13, 379–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-051217-111018

Poskanzer, K. E., and Yuste, R. (2016). Astrocytes regulate cortical state switching in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, E2675–E2684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520759113

Ransom, C. B., Ransom, B. R., and Sontheimer, H. (2000). Activity-dependent extracellular K+ accumulation in rat optic nerve: the role of glial and axonal Na+ pumps. J. Physiol. 522, 427–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00427.x

Rauen, T., Rothstein, J. D., and Wassle, H. (1996). Differential expression of three glutamate transporter subtypes in the rat retina. Cell Tissue Res. 286, 325–336. doi: 10.1007/s004410050702

Regan, M. R., Huang, Y. H., Kim, Y. S., Dykes-Hoberg, M. I., Jin, L., Watkins, A. M., et al. (2007). Variations in promoter activity reveal a differential expression and physiology of glutamate transporters by glia in the developing and mature CNS. J. Neurosci. 27, 6607–6619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0790-07.2007

Reichenbach, A., Derouiche, A., and Kirchhoff, F. (2010). Morphology and dynamics of perisynaptic glia. Brain Res. Rev. 63, 11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.02.003

Ribak, C. E., Tong, W. M., and Brecha, N. C. (1996). GABA plasma membrane transporters, GAT-1 and GAT-3, display different distributions in the rat hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 367, 595–606. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19960415)367:4<595::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-#

Robin, L. M., Oliveira da Cruz, J. F., Langlais, V. C., Martin-Fernandez, M., Metna-Laurent, M., Busquets-Garcia, A., et al. (2018). Astroglial CB1 receptors determine synaptic D-serine availability to enable recognition memory. Neuron 98, 935.e5–944.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.034

Rose, C. R., Felix, L., Zeug, A., Dietrich, D., Reiner, A., and Henneberger, C. (2017). Astroglial glutamate signaling and uptake in the hippocampus. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10:451. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00451

Rose, C. R., and Ransom, B. R. (1997). Gap junctions equalize intracellular Na+ concentration in astrocytes. Glia 20, 299–307. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199708)20:4<299::aid-glia3>3.0.co;2-1

Rouach, N., Koulakoff, A., Abudara, V., Willecke, K., and Giaume, C. (2008). Astroglial metabolic networks sustain hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science 322, 1551–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.1164022

Roux, L., Benchenane, K., Rothstein, J. D., Bonvento, G., and Giaume, C. (2011). Plasticity of astroglial networks in olfactory glomeruli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 18442–18446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107386108

Rusakov, D. A. (2015). Disentangling calcium-driven astrocyte physiology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 226–233. doi: 10.1038/nrn3878

Sáez, P. J., Shoji, K. F., Aguirre, A., and Sáez, J. C. (2014). Regulation of hemichannels and gap junction channels by cytokines in antigen-presenting cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:742734. doi: 10.1155/2014/742734

Savtchouk, I., and Volterra, A. (2018). Gliotransmission: beyond black-and-white. J. Neurosci. 38, 14–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0017-17.2017

Schwarz, Y., Zhao, N., Kirchhoff, F., and Bruns, D. (2017). Astrocytes control synaptic strength by two distinct v-SNARE-dependent release pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1529–1539. doi: 10.1038/nn.4647

Scimemi, A. (2014). Structure, function, and plasticity of GABA transporters. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:161. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00161

Seifert, G., Henneberger, C., and Steinhauser, C. (2018). Diversity of astrocyte potassium channels: an update. Brain Res. Bull. 136, 26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.12.002

Seifert, G., Huttmann, K., Binder, D. K., Hartmann, C., Wyczynski, A., Neusch, C., et al. (2009). Analysis of astroglial K+ channel expression in the developing hippocampus reveals a predominant role of the Kir4.1 subunit. J. Neurosci. 29, 7474–7488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3790-08.2009

Serrano, A., Haddjeri, N., Lacaille, J. C., and Robitaille, R. (2006). GABAergic network activation of glial cells underlies hippocampal heterosynaptic depression. J. Neurosci. 26, 5370–5382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-05.2006

Shigetomi, E., Jackson-Weaver, O., Huckstepp, R. T., O’Dell, T. J., and Khakh, B. S. (2013). TRPA1 channels are regulators of astrocyte basal calcium levels and long-term potentiation via constitutive D-serine release. J. Neurosci. 33, 10143–10153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5779-12.2013

Tabernero, A., Medina, J. M., and Giaume, C. (2006). Glucose metabolism and proliferation in glia: role of astrocytic gap junctions. J. Neurochem. 99, 1049–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04088.x

Takata, N., and Hirase, H. (2008). Cortical layer 1 and layer 2/3 astrocytes exhibit distinct calcium dynamics in vivo. PLoS One 3:e2525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002525

Takata, N., Mishima, T., Hisatsune, C., Nagai, T., Ebisui, E., Mikoshiba, K., et al. (2011). Astrocyte calcium signaling transforms cholinergic modulation to cortical plasticity in vivo. J. Neurosci. 31, 18155–18165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-11.2011

Tanaka, K., Watase, K., Manabe, T., Yamada, K., Watanabe, M., Takahashi, K., et al. (1997). Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science 276, 1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699

Theodosis, D. T., Poulain, D. A., and Oliet, S. H. (2008). Activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity of astrocyte-neuron interactions. Physiol. Rev. 88, 983–1008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2007