95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Mol. Neurosci. , 22 July 2022

Sec. Neuroplasticity and Development

Volume 15 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2022.964488

This article is part of the Research Topic The Role of GABA-Shift in Neurodevelopment and Psychiatric Disorders View all 13 articles

Inhibitory neurotransmission plays a fundamental role in the central nervous system, with about 30–50% of synaptic connections being inhibitory. The action of both inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric-acid (GABA) and glycine, mainly relies on the intracellular Cl– concentration in neurons. This is set by the interplay of the cation chloride cotransporters NKCC1 (Na+, K+, Cl– cotransporter), a main Cl– uptake transporter, and KCC2 (K+, Cl– cotransporter), the principle Cl– extruder in neurons. Accordingly, their dysfunction is associated with severe neurological, psychiatric, and neurodegenerative disorders. This has triggered great interest in understanding their regulation, with a strong focus on phosphorylation. Recent structural data by cryogenic electron microscopy provide the unique possibility to gain insight into the action of these phosphorylations. Interestingly, in KCC2, six out of ten (60%) known regulatory phospho-sites reside within a region of 134 amino acid residues (12% of the total residues) between helices α8 and α9 that lacks fixed or ordered three-dimensional structures. It thus represents a so-called intrinsically disordered region. Two further phospho-sites, Tyr903 and Thr906, are also located in a disordered region between the ß8 strand and the α8 helix. We make the case that especially the disordered region between helices α8 and α9 acts as a platform to integrate different signaling pathways and simultaneously constitute a flexible, highly dynamic linker that can survey a wide variety of distinct conformations. As each conformation can have distinct binding affinities and specificity properties, this enables regulation of [Cl–]i and thus the ionic driving force in a history-dependent way. This region might thus act as a molecular processor underlying the well described phenomenon of ionic plasticity that has been ascribed to inhibitory neurotransmission. Finally, it might explain the stunning long-range effects of mutations on phospho-sites in KCC2.

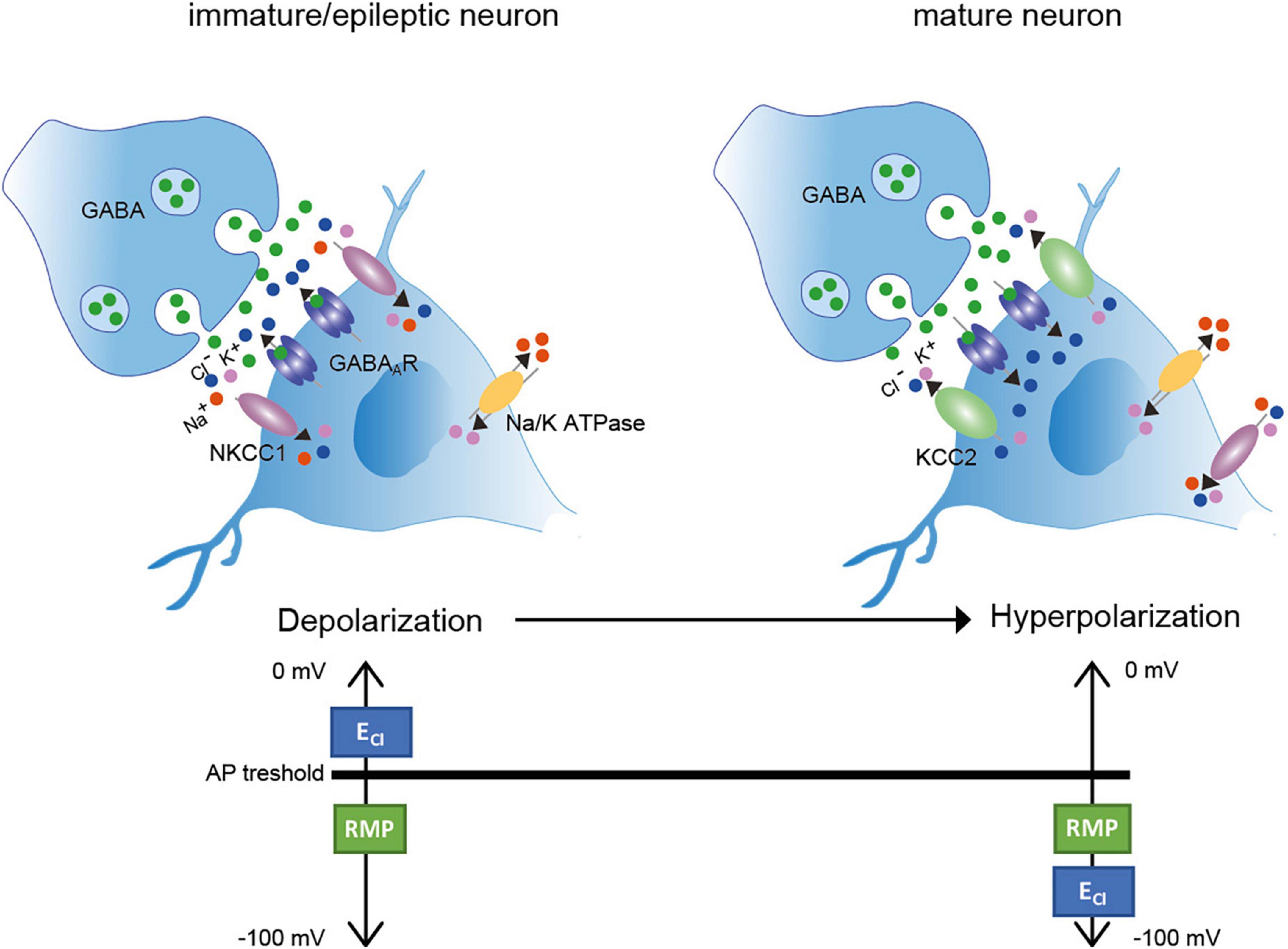

Information transfer in the brain requires a homeostatic control of neuronal firing rate (Turrigiano and Nelson, 2004; Eichler and Meier, 2008). Therefore, a functional balance between excitatory and inhibitory synapses (E-I balance) is established during development and maintained throughout life (Turrigiano and Nelson, 2004; Eichler and Meier, 2008). Excitatory synaptic transmission is mainly mediated through glutamatergic synapses and inhibitory synaptic transmission by GABAergic and glycinergic signaling (Eichler and Meier, 2008). The inhibitory neurotransmitters GABA (gamma aminobutyric acid) and glycine mainly bind to ionotropic GABAA and glycine receptors (GABAAR and GlyR), correspondingly (Bormann et al., 1987). GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in both the brain and spinal cord, since GABAAR are widely expressed in these tissues [reviewed in Möhler (2006)]. Glycine is mainly present in the brainstem and spinal cord, where it acts on a variety of neurons involved in motor and sensory function [reviewed in Rahmati et al. (2018)]. In mature neurons, the binding of the inhibitory neurotransmitters results in Cl– influx due to a low intracellular Cl– ([Cl–]i.) concentration and thus to hyperpolarizing inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (Figure 1). In contrast, in immature neurons, binding of GABA and glycine to their respective ionotropic receptors leads to an efflux of Cl– due to a high [Cl–]i (Cherubini et al., 1990, 1991; Luhmann and Prince, 1991; Zhang et al., 1991; Ehrlich et al., 1999; Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Rahmati et al., 2018; Figure 1). This results in a depolarizing action. The developmental shift from depolarization to hyperpolarization (D/H shift) occurs during early postnatal life (Blaesse et al., 2009; Kaila et al., 2014) and is present throughout the nervous system (e.g., cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord) (Ben-Ari et al., 1983; Cherubini et al., 1990; Luhmann and Prince, 1991; Wu et al., 1992; Kandler and Friauf, 1995; Owens et al., 1996; Rohrbough and Spitzer, 1996; Ehrlich et al., 1999). However, the timing of the D/H shift can differ between species such as precocial (e.g., guinea pig, prenatal D/H shift) and altricial (e.g., rat and mice, postnatal D/H shift) species (Rivera et al., 1999). Furthermore, even within a species, timing differences exist between different neuronal populations (Löhrke et al., 2005).

Figure 1. Depolarization/Hyperpolarization shift in inhibitory neurons (Left). In immature neurons, high transport activity of NKCC1 results in increased [Cl–]i. Binding of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA to GABAA receptors results in Cl– outward currents and thus depolarization. Here, the ECl– is more depolarized than the AP threshold (Right). In mature neurons, KCC2 activity is increased resulting in decreased [Cl–]i. Binding of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA to its receptor results in Cl– inward currents and thus hyperpolarization. ECl– is here hyperpolarized according to the resting membrane potential. AP: action potential; RMP: resting membrane potential. Green dots: GABA; red dots: Na+; purple dots: K+; blue dots: Cl–. Figure modified from Moore et al. (2017).

Important players to regulate the D/H shift are the secondary active membrane transporters NKCC1 (sodium potassium chloride cotransporter 1) and KCC2 (potassium chloride cotransporter 2) (Delpire, 2000; Payne et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2017; Virtanen et al., 2021). Both transporters mediate the Cl– coupled transport of K+ with or without Na+ across the plasma membrane. In immature neurons, NKCC1 is one of the main Cl– uptake transporter, maintaining a high [Cl–]i. (Figure 1; Sung et al., 2000; Ikeda et al., 2004; Dzhala et al., 2005; Achilles et al., 2007). In mature neurons, KCC2 is the essential Cl– extruder that lowers [Cl–]i and thus enables fast hyperpolarizing post-synaptic inhibition due to Cl– influx (Kaila, 1994; Rivera et al., 1999). NKCC1 is also expressed in mature neurons, but the mRNA expression developmentally changes from a neuronal pattern at birth to a glial pattern (esp. oligodendrocytes and their precursors, endothelial cells, astrocytes and microglia) in adult mouse brain (Hübner et al., 2001a; Su et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2014; Henneberger et al., 2020; Virtanen et al., 2020; Tóth et al., 2022). In glia cells, NKCC1 regulates for instance the proliferation and maturation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the adult mouse cerebellar white mater (Zonouzi et al., 2015) and modulates the microglial phenotype and inflammatory response (Tóth et al., 2022).

The physiological relevance of NKCC1 and KCC2 is corroborated by the phenotypes present in knock-out mice. Mice with disruption of the gene Slc12a2 encoding both NKCC1 splice variants (NKCC1a and NKCCb) are viable, but suffer from deafness, pain perception, and male infertility (Randall et al., 1997; Delpire et al., 1999; Delpire and Mount, 2002). Mice with disruption of the gene Slc12a5 that encodes both splice variants of KCC2 (KCC2a and KCC2b) die shortly after birth due to severe motor deficits that also affect respiration (Hübner et al., 2001b; Uvarov et al., 2007).

Several other plasma membrane Cl– channels and transporters are present to regulate Cl– homeostasis in neurons [see review: (Rahmati et al., 2018)]. These include the voltage-gated Cl– channels (e.g., ClC-1 to 3), Ca2+ activated Cl– channels (TMEM16 family, anoctamins), the pH sensitive Cl– channels and transporters of the SLC4 family [Na+- independent Cl–/HCO3– exchangers (e.g., AE3) and Na+-dependent Cl–/HCO3– exchangers (e.g., NCBE and NDCBE)], and SLC26 family [e.g., anion exchange transporter (SLC26A7) and sodium independent sulfate anion transporter (SLC26A11)] and glutamate-activated Cl– channels (EAAT4) (Blaesse et al., 2009; Rahmati et al., 2018; Kilb, 2020). In this review, we will focus on the secondary active transporters NKCC1 and KCC2.

Inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABAA or glycine receptors is somewhat unique in that its function can be relatively easily modified via changes to the ionic driving force. In mature neurons, a low [Cl–]i results in ECl being slightly hyperpolarized with respect to the neuronal resting membrane potential Vrest (Figure 1). In P12 auditory neurons of the lateral superior olive, for instance, [Cl–]i is 8 ± 5 mM, and in cortical pyramidal neurons cultured for 21 days, it is 7.3 ± 0.2 mM (Balakrishnan et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2005). In such conditions, GABAA or glycine receptor activation results in an inward Cl– gradient that reduces excitability by pulling the membrane potential away from threshold. This decreases the probability of action potential generation. However, even relatively small increases in [Cl–]i will depolarize ECl toward Vrest (Currin et al., 2020). This significantly reduces or even eliminates hyperpolarizing inhibition thus affecting the input-out function of neurons and modify or even degenerate neuronal function (Currin et al., 2020). Computational models of a mature CA1 pyramidal neuron revealed that shifting the reversal potential of GABA (EGABA) by only ∼2.5 mM (∼ to 5 mV from −75 to −70 mV) results in an increase in action potential firing by 39% (Saraga et al., 2008). Further increase in Cl–can even invert the polarity of GABAA or glycine receptor mediated currents from hyperpolarizing to depolarizing. On the other hand, extraordinary decreases in neuronal Cl– with functional relevance have also been observed. Auditory neurons of the superior paraolivary nucleus possess an extremely negative ECl, which increases the magnitude of hyperpolarizing currents. This is required to trigger hyperpolarization-activated non-specific cationic and T-type calcium currents to promote rebound spiking to signal when a sound ceases (Kopp-Scheinpflug et al., 2011).

Changes in the ionic driving force for Cl– have been observed on different time scales. The developmental D/H shift occurs on the long term and results in the general observation of hyperpolarizing action of GABA or glycine in the mature brain. More dynamic, short-term alterations have also been reported (Woodin et al., 2003; Khirug et al., 2005; Lamsa et al., 2010; Chamma et al., 2012; Doyon et al., 2016). These changes often occur in a way that relates to the history of synaptic activity. Coincident pre- and post-synaptic spiking results in mature hippocampal neurons in a shift of EGABA toward more positive values (Woodin et al., 2003; Ormond and Woodin, 2009). This change in [Cl–]i in the post-synaptic neurons was synapse specific and dependent on KCC2 activity, as revealed by furosemide application (Woodin et al., 2003). In immature hippocampal neurons, coincident activity was reported to result in both a hyperpolarized EGABA (Balena and Woodin, 2008) or a depolarized EGABA (Xu et al., 2008). This difference might be attributed to differences in the system used (cultured neurons vs. hippocampal slices) or in the protocols. In both studies, pharmacological approaches related the change in EGABA to changes in the activity of NKCC1.

These examples of short-term plasticity that involves changes in the ionic driving force for post-synaptic ionotropic receptors have been referred to as ionic plasticity (Rivera et al., 2005) or ionic shift plasticity (Lamsa et al., 2010). These changes are directly related to the history of activity at inhibitory synapses and likely include rapid post-translational modifications of NKCC1 and KCC2.

The easy modification of the effect of GABA and glycine via changes in the ionic driving force for Cl– makes inhibitory neurotransmission prone to disease causing alterations. Indeed, perturbation of [Cl–]i is associated with a long and still growing list of neurological, psychiatric, and neurodegenerative disorders including epilepsy, neuropathic pain, spasticity, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, brain trauma, ischemic insults, Rett Syndrome and Parkinson‘s disease (Rivera et al., 2002; Coull et al., 2003; Huberfeld et al., 2007; Papp et al., 2008; Shulga et al., 2008; Boulenguez et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012; Kahle et al., 2014; Puskarjov et al., 2014; Tyzio et al., 2014; Merner et al., 2015; Ben-Ari, 2017; Pisella et al., 2019; Savardi et al., 2021). These disorders are often associated with increased activity of NKCC1 and/or decreased activity of KCC2 promoting GABAAR mediated membrane depolarization and excitation (Figure 1; Kaila et al., 2014; Mahadevan and Woodin, 2016; Ben-Ari, 2017; Moore et al., 2017; Fukuda and Watanabe, 2019; Tillman and Zhang, 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Savardi et al., 2021). In patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, a subset of neurons in the subiculum in the hippocampus displayed depolarizing up to excitatory GABAergic response that correlated with decreased KCC2 expression and upregulation of NKCC1 (Cohen et al., 2002; Palma et al., 2006; Huberfeld et al., 2007; Muñoz et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2017). Contradictory, recent finding in NKCC1 knock out mice showed that deletion of NKCC1 results in more severe epileptic phenotype in the intrahippocampal kainate mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy (Hampel et al., 2021). Thus, NKCC1 role in epilepsy is still not completely understood.

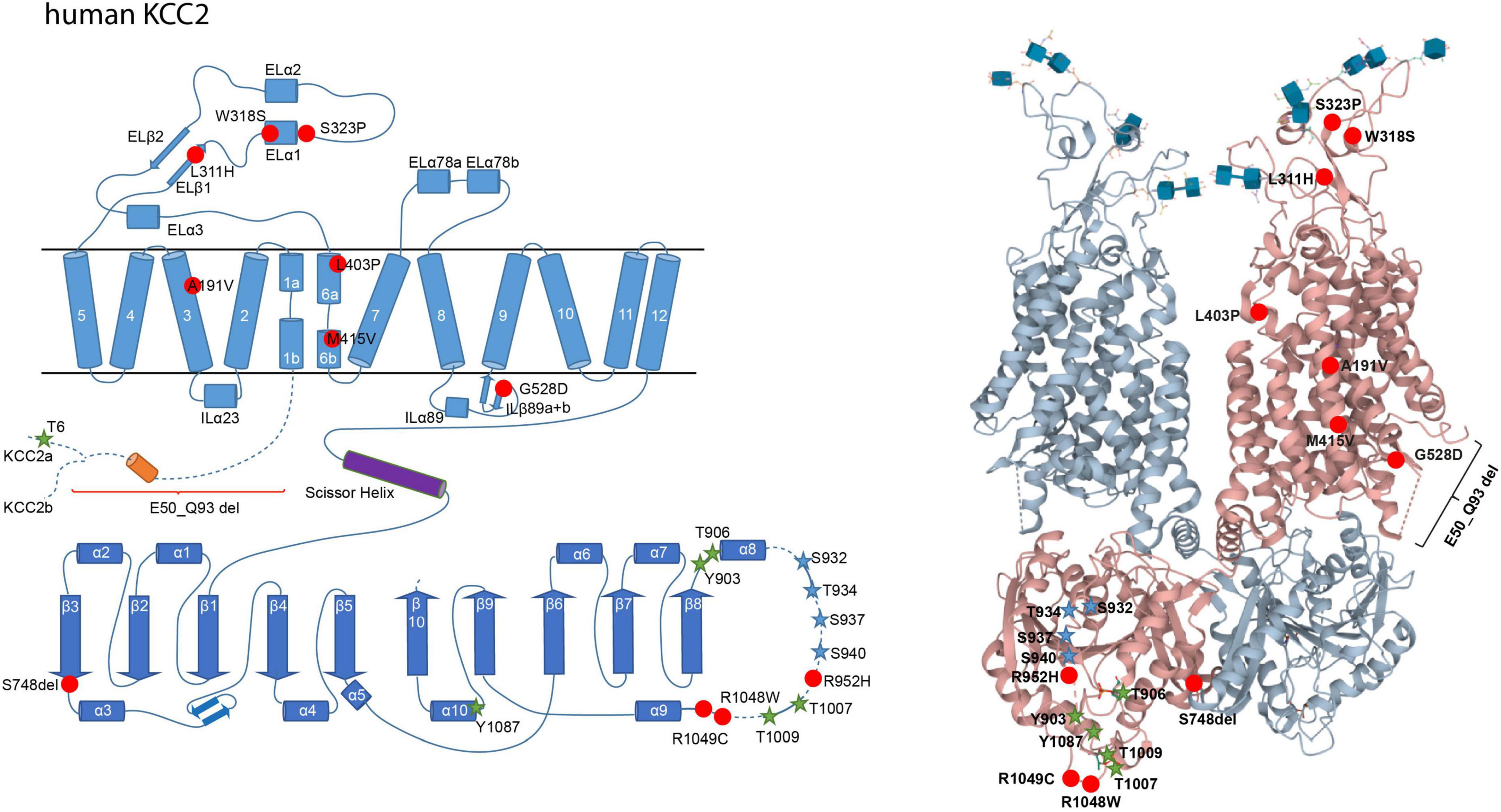

Concerning KCC2, several human pathogenic variants are associated with epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorder (Figure 2). These include the heterozygous missense mutations of Arg to His at positions 952 (Arg952His; numbering according to KCC2b) and 1049 (Arg1049His) that are associated with febrile seizures and/or idiopathic generalized seizure and decreased KCC2 activity (Kahle et al., 2014; Puskarjov et al., 2014; Merner et al., 2015). Substitution of Arg952His was also found to be associated with schizophrenia (Merner et al., 2015, 2016). In addition, three autosomal recessive heterozygous mutations (Leu288His, Leu403Pro, and Gly528Asp) were identified in children of two unrelated families, which are associated with epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures (Stödberg et al., 2015). Two children had compound heterozygous mutations of Leu403Pro and Gly528Asp and the other child had a homozygous Leu288His mutation (Stödberg et al., 2015). Leu403Pro and Gly528Asp both result in loss-of-function and Leu288His decreases KCC2 activity (Stödberg et al., 2015). Saitsu et al. (2016) also discovered six heterozygous compound KCC2 variants (E50_Q93del, Ala191Val, Ser323Pro, Met415Val, Trp318Ser, and Ser748del) that are associated with this disorder (Saitsu et al., 2016). Analysis of E50_Q93del and Met415Val revealed that each of the mutations strongly decreases KCC2 activity, whereas Ala191Val and Ser323Pro moderately impair KCC2 function. Co-transfection of E50_Q93del with Ala191Val or Met415Val with Ser323Pro significantly decreases KCC2 activity (Saitsu et al., 2016).

Figure 2. Structural organization of human KCC2. 2-dimensional (left) and 3-dimensional (right) organization of human KCC2 according to Chi X. et al. (2020) (PDB: 6m23). KCC2 consists of 12 transmembrane domains (TMs) and two intracellular termini. A large extracellular loop is located between transmembrane domains 5 and 6 (EL3) and five N-glycosylation sites (blue cubes, left). Phosphorylation sites that increase KCC2 activity upon dephosphorylation are marked as green stars (Thr6 in KCC2a, Thr906, Tyr903, Thr1007, Thr1009, and Tyr1087). Phosphorylation sites that increase KCC2 activity upon phosphorylation are marked as blue stars (Ser932, Thr934, Ser937, Ser940). Human pathogenic variants of KCC2 associated with epilepsy, autism-spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia are depicted as red dots (Ala191Val, Leu311His, Trp318Ser, Ser323Pro, Leu403Pro, Met415Val, Gly528Asp, Arg952His, Arg1048Trp, Arg1049C, Ser748del). Annotation of amino acid residues is according to human KCC2b. The 3D reconstruction of KCC2 was generated using cryo-EM (Chi X. et al., 2020). 3D visualization was performed using Mol* Viewer in PDB (Sehnal et al., 2021).

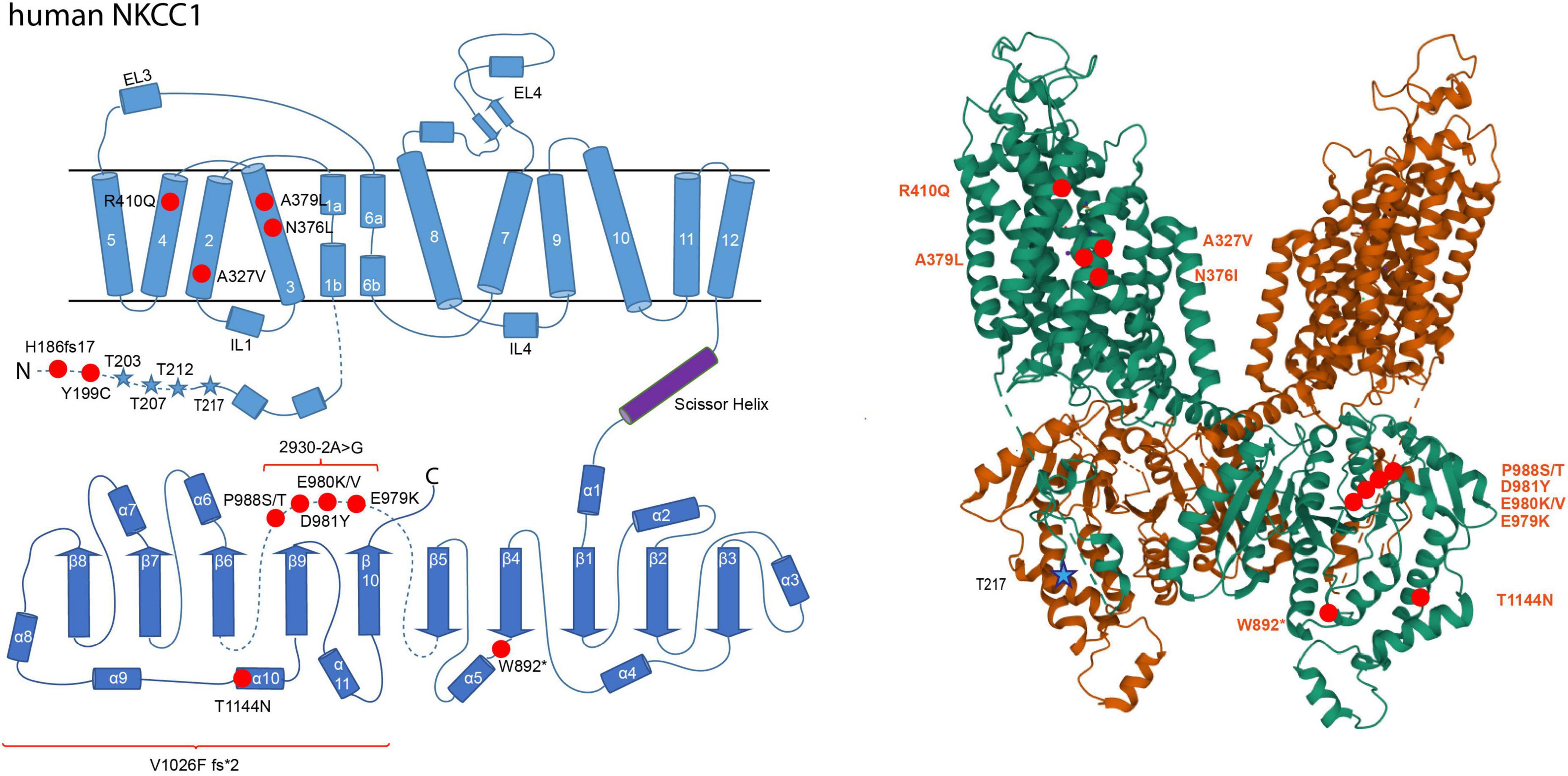

In schizophrenia, an enhanced NKCC1/KCC2 expression ratio was shown to increase [Cl–]i (Arion and Lewis, 2011; Hyde et al., 2011; Ben-Ari, 2017). Substitution of Arg952His is associated with schizophrenia and results in decreased KCC2 activity (Figure 2; Merner et al., 2015). Additionally, the human pathogenic NKCC1 variant Tyr199Cys, which enhances its activity, is associated with this disorder (Figure 3; Merner et al., 2016).

Figure 3. Structural organization of human NKCC1. 2-dimensional (left) and 3-dimensional (right) organization of human NKCC1 (A) according to Zhao et al. (2022) (PDB: 7S1X). NKCC1 consists of 12 transmembrane domains (TMs) and two intracellular termini. A large extracellular loop is located between transmembrane domains 7 and 8 (EL4). Phosphorylation sites that increase NKCC1 activity upon phosphorylation are marked as blue stars (Thr203, Thr207, Thr212, and Thr217). Human pathogenic variants of NKCC1 associated with autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, multisystem dysfunction, spastic quadriparesis, and hearing impairment are depicted as red dots in human NKCC1 (His186fs17, Tyr199Cys, Ala327Val, Asn376Leu, Ala379Leu, Arg410Glu, Trp892*, Gln979Lys, Asn981Tyr, Pro988Ser, Pro988Thr, Thr411Asn, 2930.2A > G, Val1026F fs*2). The 3D reconstruction of NKCC1 was generated using cryo-EM (Zhao et al., 2022). 3D visualization was performed using Mol* Viewer in PDB (Sehnal et al., 2021).

In autism spectrum disorder, downregulation of KCC2 and upregulation of NKCC1 were observed in several brain regions (Savardi et al., 2021). Application of bumetanide, a specific NKCC inhibitor, markedly improves visual contact, sensory behavior, rigidity and memory performance in preclinical trials (Lemonnier and Ben-Ari, 2010; Lemonnier et al., 2012, 2017; Hadjikhani et al., 2015, 2018). This suggests an association of NKCC1 with autism spectrum disorder. This is supported by two human pathogenic variants (Ala379Leu and Arg410Gln) that are linked to this disorder and intellectual disabilities (McNeill et al., 2020; Adadey et al., 2021). Both mutations impair NKCC1 function (McNeill et al., 2020), indicating a developmental defect. Unfortunately, bumetanide has a poor blood-brain barrier permeability and two recent phase 3 clinical trials using bumetanide in the treatment of ASD in children and adults showed no effectiveness (Löscher and Kaila, 2021). Concerning KCC2, three human pathogenic variants (Arg952His, Arg1048Trp, and Arg1049Cys) have also been linked to it (Merner et al., 2016). Both Arg952His and Arg1049Cys impair KCC2 function; functional data for Arg1048Trp are not yet available (Kahle et al., 2014).

Several NKCC1 human pathogenic variants are furthermore associated with multisystem dysfunction (Val1026F fs*2), spastic quadriparesis (His186fs17 frameshift mutant), spastic paraparesis (Asn376Ile) and minor developmental delay (W892*) (Delpire et al., 2016; McNeill et al., 2020; Adadey et al., 2021). Finally, NKCC1 exon 21 variants are linked to hearing impairment (Glu979Lys, Glu980Val, Glu980Lys) and hearing loss (Asp981Tyr, Pro988Ser, Pro988Thr, and 2930-2A > G) (Morgan et al., 2020; Mutai et al., 2020; Adadey et al., 2021; Koumangoye et al., 2021; Vanniya et al., 2022). The mutation 2930-2A > G has an effect on splicing leading to loss of exon 21 (Mutai et al., 2020). All of these mutations impair NKCC1 function (Delpire et al., 2016; McNeill et al., 2020; Mutai et al., 2020; Adadey et al., 2021). The human pathogenic variants Ala327Val and Thr1144Asn outside exon 21 are also associated with hearing impairment (McNeill et al., 2020; Adadey et al., 2021). These sensory impairments, however, rather reflects perturbed K+ recycling in the inner ear than an imbalance in neurotransmission.

To sum up, dysregulation of NKCC1 and KCC2 result in an imbalance of excitation/inhibition that is associated with several neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Modulation of Cl– extrusion constitute promising new strategies for treating these debilitating diseases. Phosphorylation has emerged as the major means to rapidly and reversibly modulate intrinsic transport activity, cell surface stability, and plasma membrane trafficking of NKCC1 and KCC2 (Kahle et al., 2013). So far, four to five phospho-sites with a regulatory effect on transport activity have been identified in the N-terminus of NKCC1 (Thr203, Thr207, Thr212, and Thr217 in human NKCC1; Thr175, Thr179, Thr184, Thr189, and Thr202 in shark NKCC1) (Muzyamba et al., 1999; Flemmer et al., 2002; Gagnon et al., 2006; Vitari et al., 2006; Hartmann and Nothwang, 2014). For KCC2, the number of regulatory phospho-sites that affect transport activity due to (de)phosphorylation is even higher with one regulatory phospho-site in the N-terminus (Thr6 in KCC2a) and nine phospho-sites in the C-terminus (Tyr903, Thr906, Ser932, Thr934, Ser937, Ser940, Thr1007, Thr1009, and Tyr1087) (Lee et al., 2007, 2010; Rinehart et al., 2009; Weber et al., 2014; Titz et al., 2015; Markkanen et al., 2017; Cordshagen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020b). In addition, there are phospho-sites with no detectable effect so far on KCC2 activity (N-terminus: Ser25, Ser26, Ser31, Thr34 and C-terminus: Ser728, Thr787, Thr999, Ser1022, Ser1025, Ser1026, Ser1034) or which have not yet been functionally investigated (N-terminus: Thr32, Ser55, Ser60, Thr69, and C-terminus: Ser913, Ser988) (Lee et al., 2007; de Los Heros et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2014; Cordshagen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020b). The difference in the location of the phospho-sites between NKCC1 (N-terminus) and KCC2 (C-terminus) might relate to the presence of an autoinhibitory loop present in KCC2 (Chew et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). This loop occludes the translocation pathway and thus locks the transporter in the inactive state (Zhang et al., 2021). The outward-open conformation of the human NKCC1 displays no autoinhibitory loop (Figure 3; Zhao et al., 2022). Although the presence of an auto-inhibitory loop in other conformations cannot be excluded, the current data suggests two distinct regulatory mechanisms in the N-terminus of CCC subfamilies: post-translational modification in NKCC1 and an autoinhibitory loop in KCC2 (Chew et al., 2021).

The high number of regulatory phospho-sites enables the transporters to sample across a multitude of signaling pathways, including with-no-lysine kinase (WNK) with their downstream kinase targets STE20/SP1-related proline/alanine rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress response kinase (OSR1), protein kinase C (PKC), Src-tyrosine kinases, brain type creatine kinases and protein phosphatases (Liedtke et al., 2003; Korkhov et al., 2004; Inoue et al., 2006; Gagnon and Delpire, 2013; de Los Heros et al., 2014; Medina et al., 2014). The high number of phospho-sites might reflect the multi-compartmental organization of a neuron (e.g., soma vs. proximal vs. distal dendrites) and the different states a neuron or a synapse can adopt (see ionic plasticity). Future work should therefore aim to relate individual phospho-sites to specific forms of ionic plasticity. The increasing availability of mice with mutated phospho-sites (Silayeva et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2018, 2019; Pisella et al., 2019) will pave the avenue for such analyses.

Generally, phosphorylation of NKCC1 and dephosphorylation of KCC2 increase transport activity. The main mechanism that ensures reciprocal regulation is WNK-SPAK/OSR1 dependent phosphorylation of specific NKCC1 and KCC2 phospho-sites, thus activating NKCCs and inactivating KCCs (Darman and Forbush, 2002; Vitari et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2008; Rinehart et al., 2009; Kahle et al., 2013; Alessi et al., 2014a; Titz et al., 2015; Markkanen et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020b). SPAK/OSR1, which is activated via WNK1, phosphorylates Thr6 and Thr1007 of KCC2 (Rinehart et al., 2009; de Los Heros et al., 2014; Conway et al., 2017; Heubl et al., 2017; Markkanen et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2018). WNKs also interact with a yet unknown kinase to phosphorylate Thr906 in the KCC2 C-terminus (de Los Heros et al., 2014; Conway et al., 2017). Site directed mutagenesis of Thr6 of KCC2a or Thr906 and Thr1007 of KCC2 to alanine (mimicking the dephosphorylated state) results in activation of KCC2 as shown in cultured hippocampal neurons, cultured cortical neurons and slices, and HEK293 cells (Rinehart et al., 2009; Inoue et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2014; Friedel et al., 2015; Titz et al., 2015). The enhanced activation via dephosphorylation of Thr906 and Thr1007 is accompanied by an increase in cell surface expression in cultured hippocampal neurons (Friedel et al., 2015). Enhanced phosphorylation of Thr906 and Thr1007 increases in mature hippocampal neurons membrane diffusion resulting in cluster dispersion and enhanced membrane turnover (Heubl et al., 2017; Côme et al., 2019). This indicates that dephosphorylation of these residues increases KCC2 activity. WNK-SPAK/OSR1 mediates also the phosphorylation of human NKCC1 Thr203, Thr207, Thr212, and Thr217 resulting in enhanced NKCC1 activity (Darman and Forbush, 2002; Dowd and Forbush, 2003; Moriguchi et al., 2005; Vitari et al., 2006; Gagnon et al., 2007; Richardson and Alessi, 2008; Geng et al., 2009; Thastrup et al., 2012; Alessi et al., 2014b; Hartmann and Nothwang, 2014; Heubl et al., 2017; Shekarabi et al., 2017). Thus, dephosphorylation (KCC2) and phosphorylation (NKCC1) reciprocally decrease the activity of the two Cl– cotransporters (Zhang et al., 2020b).

The reciprocal phosphorylation of NKCC1 and KCC2 by the WNK-SPAK/OSR1-mediated pathway is involved in the regulation of the development-dependent D/H shift. In neurons, WNK1 phosphorylates SPAK at Ser373 and of OSR1 at Ser325, thereby activating these kinases. This results in phosphorylation of NKCC1 (activation) and KCC2 (inactivation) and thus their reciprocal regulation (Vitari et al., 2005; Richardson and Alessi, 2008; de Los Heros et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020a). The action of WNK1 developmentally decreases, since phosphorylation of Ser382 in WNK1, and consequently of its targets Ser373 in SPAK and Ser325 in OSR1, decreases over time in cortical and hippocampal cultures (Friedel et al., 2015). This causes reduced phosphorylation of Thr906 and Thr1007 in KCC2 (Rinehart et al., 2009; Friedel et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2017). The developmental dependent dephosphorylation of Thr906 and Thr1007 activates KCC2 function, shifting EGABA to more negative values (Friedel et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2017). This was corroborated by a dominant-negative WNK1 mutant or by genetic depletion of the kinase in immature neurons, as both manipulations cause an early hyperpolarizing action of GABA due to decreased phosphorylation of KCC2 Thr906 and Thr1007 (Friedel et al., 2015). Moreover, cultured hippocampal neurons derived from a mouse model, in which Thr906 and Thr1007 were mutated to alanine (mimicking the dephosphorylated state) show an accelerated D/H shift due to increased KCC2 function (Moore et al., 2019). In contrast, Thr906E/Thr1007E mice (mimicking phosphorylated states) showed a delayed D/H shift in CA3 pyramidal neurons and hippocampal slices (Pisella et al., 2019). These mice showed in addition long-term abnormalities in social behavior, memory retention and increased seizure susceptibility (Moore et al., 2019; Pisella et al., 2019). These data support the notion that post-translational regulation of KCC2 plays a central role in development-dependent regulation in the D/H shift in the central nervous system and that impairment of this regulatory mechanism entails neurodevelopmental disorders (Pisella et al., 2019).

Reciprocal regulation of NKCC1 and KCC2 is important not only in neuronal development but also in adult neurons. Inhibition of GABAAR via gabazine in mature neurons increases [Cl–]i. This activates WNK1 leading to phosphorylation of Thr906/Thr1007 in KCC2 (inactivation) and phosphorylation of Thr203/Thr207/Thr212 in NKCC1 (activation) (Heubl et al., 2017). This is important for “auto-tuning” GABAergic signaling via rapid regulation of KCC2-mediated Cl– extrusion (Heubl et al., 2017).

The principle that phosphorylation increases the activity of N(K)CCs and dephosphorylation that of KCCs is true for N(K)CCs and KCC1, KCC3, and KCC4. Phospho-regulation in KCC2 is more complex since phosphorylation and dephosphorylation can both enhance its activity. Dephosphorylation of the following phospho-sites increases KCC2 activity: Thr6 (present only in KCC2a) and Thr906, Thr1007, Thr1009, and Tyr1087 (present in both splice variants) (Figure 2). The mechanism leading to phosphorylated Thr6, Thr906, and Thr1007 by WNK1 mediated signaling was already described above. Dephosphorylation of the highly conserved Tyr1087 residue increases cell surface stability (Lee et al., 2010) and mutation of Tyr1087 to phenylalanine (mimicking the dephosphorylated state) does not alter KCC2 activity (Strange et al., 2000). In contrast, mutation of Tyr1087 into aspartate (mimicking the phosphorylated state) abolishes KCC2 activity (Strange et al., 2000; Akerman and Cline, 2006; Watanabe et al., 2009; Pellegrino et al., 2011). This indicates that KCC2 is dephosphorylated at Tyr1087 under basal conditions and that phosphorylation of this site decreases KCC2 activity. The highly conserved Thr1009 is another site that results in increased activity when dephosphorylated. Mutating this residue into alanine (mimicking the dephosphorylated state) intrinsically increases KCC2 activity without affecting cell surface expression (Cordshagen et al., 2018). The Thr1009 phosphorylating kinase has yet to be identified. Thus, several sites have been identified where dephosphorylation increases KCC2 activity.

In contrast, phosphorylation of the following residues activates KCC2: Ser932, Thr934, Ser937, and Ser940 (Figure 2). These residues are all encoded by exon 22, which is only present in KCC2 and non-therian KCC4 (Hartmann and Nothwang, 2014). The most in-depth analyzed residue is Ser940, which is phosphorylated via protein kinase C (PKC) and dephosphorylated via protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (Lee et al., 2007, 2011). Phosphorylation of Ser940 increases cell surface expression, transport activity, and membrane clustering of KCC2 (Lee et al., 2007; Chamma et al., 2012), with most clusters found at both excitatory and inhibitory synapses in hippocampal cultures (Chamma et al., 2013; Côme et al., 2019). Accordingly, dephosphorylation of Ser940 increases membrane diffusion resulting in cluster dispersion and enhanced membrane turnover of KCC2 (Chamma et al., 2013; Côme et al., 2019). Consequently, its dephosphorylation inactivates KCC2 (Lee et al., 2011). Mutation of Ser940 to alanine results in transport activity that is equal or decreased compared to KCC2 wild type activity (Lee et al., 2007; Silayeva et al., 2015; Titz et al., 2015). These different outcomes likely reflect the different cellular systems used for the analyses (HEK293 cells, neuronal cell cultures, or knock-in mice) (Lee et al., 2007; Silayeva et al., 2015; Titz et al., 2015).

During development, phosphorylation of Ser940 increases concomitantly with KCC2 activity (Moore et al., 2019). Ser940Ala knock-in mice show a delayed D/H shift, demonstrating that not only dephosphorylation of Thr906 and Thr1007 is important for the D/H shift, but also phosphorylation of Ser940 (Moore et al., 2019). Notably, these mice suffer from profound social interaction abnormalities (Moore et al., 2017, 2019). Furthermore, (de)phosphorylation of Ser940 is associated with epilepsy. Induction of status epilepticus using kainate causes dephosphorylation of Ser940 and internalization of KCC2 (Silayeva et al., 2015). This observation is supported by an analysis of the two human KCC2 pathogenic variants Arg952His and Arg1049Cys. Both variants are associated with idiopathic generalized seizure and decreased Ser940 phosphorylation (Kahle et al., 2014; Puskarjov et al., 2014; Silayeva et al., 2015). Phosphorylation of Ser940 therefore could provide an approach to limit the progress of status epilepticus (Silayeva et al., 2015).

In addition to Ser940, exon 22 encodes the phosphorylation sites Ser932, Thr934, and Ser937. Mutation of any of these residues to aspartate (mimicking the phosphorylated state) intrinsically increases KCC2 activity in HEK293 cells without affecting cell surface expression (Weber et al., 2014; Cordshagen et al., 2018). Mutation into alanine (mimicking the dephosphorylated state) has no effect in HEK293 cells (Weber et al., 2014; Cordshagen et al., 2018). Thus, both dephosphorylation and phosphorylation of specific phospho-sites can increase KCC2 activity. This peculiarity provides KCC2 with a rich regulatory tool-box for graded activity and integration of different signaling pathways (Cordshagen et al., 2018).

3D structure of the outward-open conformation of human NKCC1 (Figure 3) reveals that the dimeric interface is formed between the C-terminus and the N-terminal phosphoregulatory element and the C-terminus and the TMs (Zhao et al., 2022). These two domains define an allosteric interface that may transmit the impact of (de)phosphorylation of N-terminal phospho-sites, via the intervening C-terminal tail and the intracellular loop 1 (ICL1) to affect ion translocation (Zhao et al., 2022). Binding of kinases or phosphatases may form or disrupt these domain interactions (Zhao et al., 2022). However, FRET experiments in NKCC1 revealed that phosphorylation within the N-terminus affects movement of the C-terminus leading to a dissociation of the two monomers within the dimer (Monette and Forbush, 2012). Cross-linking studies support this conclusion. They showed that phosphorylation of residues within the N-terminus affects the localization of TM10 relative to TM12 thereby inducing movement of the C-terminus and disruption of dimerization (Monette et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, phosphorylation of N-terminal phospho-sites in NKCC1 may induce long-range distance effects involving movement of the C-terminus. It is therefore an open question whether (de)phosphorylation of N-terminal NKCC1 phospho-sites cause disengagement of the TMs as described in the outward-facing cryo-EM of NKCC1 (Zhao et al., 2022) or dissociation of the C-terminal domains (Monette and Forbush, 2012; Monette et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021).

(De)phosphorylation dependent conformational differences were also reported for KCC3. To examine the effect of phosphorylation on structural organization, two different KCC3 mutants were generated with triple substitutions of Ser45, Thr940, and Thr997 by either aspartate (KCC3-PM) or by alanine (KCC3-PKO). Analysis by cryo-EM revealed that the “dephosphorylated” KCC3-PKO is more dynamic in the scissor helix region and exhibits a greater rotational flexibility of the C-terminal dimer (Chi G. et al., 2021). The KCC3-PM mutant demonstrated more dynamic conformational changes within the ß7 strand and in the α8 and α10 helices (Chi G. et al., 2021). Multiple conformations for α7 were observed, in which the end of α7 moves 21° outward entailing conformational changes in the α7/ß6 loop (Chi G. et al., 2021). Cryo-EM identified also two conformational states in KCC1, as α8 was observed either above or below α10 (Chi G. et al., 2021). The first state matches the structures of KCC3wt and KCC3-PM (Chi G. et al., 2021). The second state is stabilized by polar interactions with glutamate residues in α11 (Chi G. et al., 2021). Thus, (de)phosphorylation of C-terminal phospho-sites results in substantial conformational reorganizations within the C-terminus in KCCs.

Notably, KCC2 Thr906 and Thr1007 correspond to the investigated Thr940, and Thr997 amino acid residues in KCC3. Both amino acid residues are bona fide phospho-sites of KCC2 and targets of the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signaling pathway with dephosphorylation resulting in increased transport activity (Rinehart et al., 2009; Inoue et al., 2012; de Los Heros et al., 2014; Titz et al., 2015; Markkanen et al., 2017). It is therefore tempting to speculate that changes in their phosphorylation pattern alter the C-terminal conformation of KCC2.

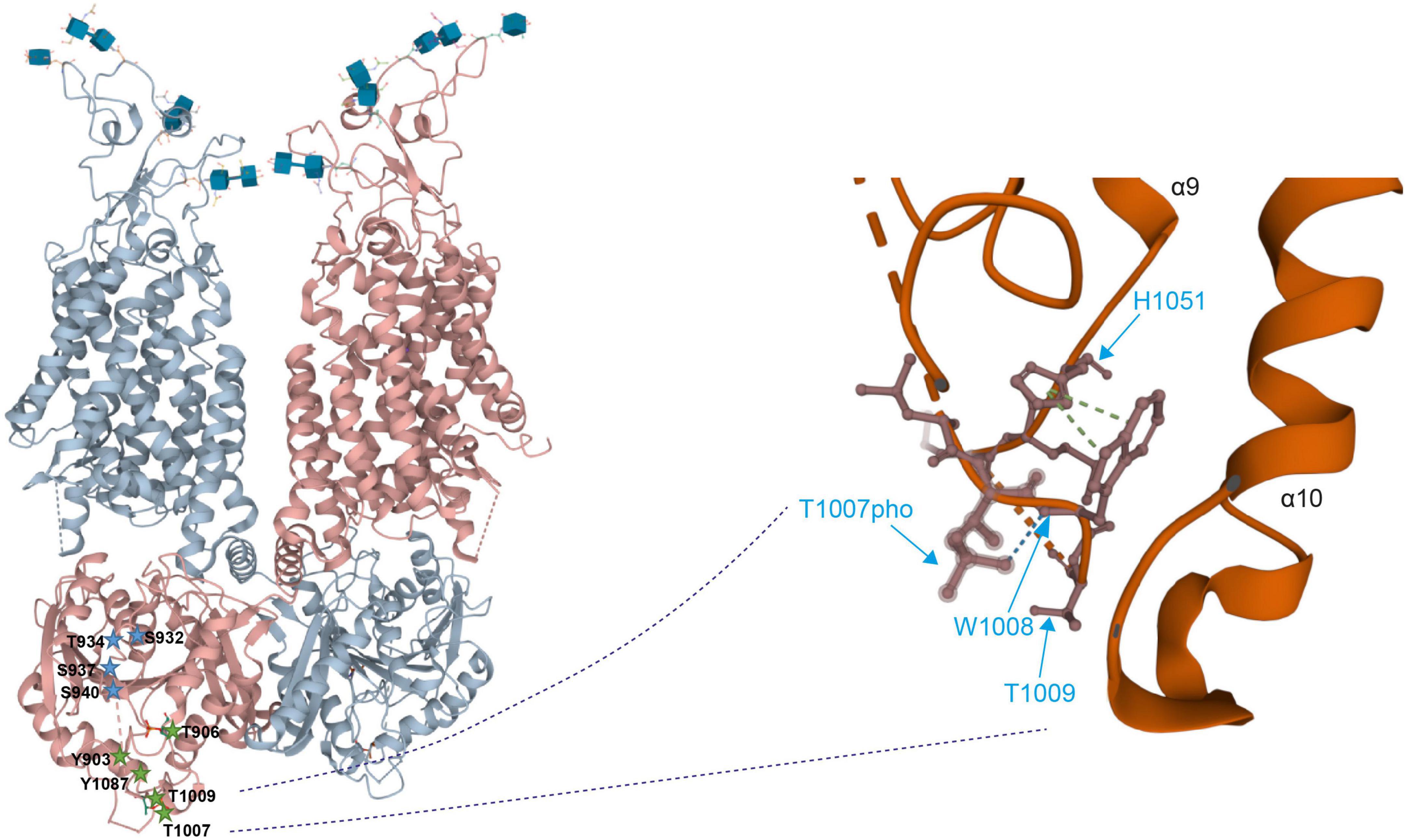

The six KCC2 phosphorylation sites Ser932, Thr934, Ser937, Ser940, Thr1007, and Thr1009, which form a tight cluster, all reside in an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) between α8 and α9 helices according to the cryo-EM reconstruction of KCC2 (Chi G. et al., 2021; Chi X. et al., 2021). The presence of six out of ten (60%) known regulatory KCC2 phospho-sites within a stretch of 134 amino acid residues (12% of the total residues, Met919 to Ala1053 in hsKCC2b) (Figure 2) agrees well with the general enrichment of post-translational modification sites in such regions due to their increased surface area (Oldfield et al., 2008; Forman-Kay and Mittag, 2013; Hsu et al., 2013). In line with this, two further phospho-sites, Tyr903 and Thr906 are also located in a disordered region between ß8 strand and α8 helix (Figure 2).

Intrinsically disordered regions do not have a well-defined tertiary structure, instead they are in a dynamic equilibrium between different sets of conformational states (Boehr et al., 2009; Flock et al., 2014). It is thus likely that (de)phosphorylation of the amino acid residues within these regions will induce structural transitions with impact on the conformation of the entire C-terminus (and likely other regions as well). Indeed, phosphorylated Thr1007 forms main chain hydrogen bonds with Trp1008, that itself has side chain interactions with His1051 (pi stacking), and Tyr903 forms a main chain hydrogen bond with Ser899 (Figure 4). Alterations in phosphorylation might affect these interactions thereby altering the organization and thus conformation of the C-terminus.

Figure 4. Detailed view on the 3D structure of the KCC2 C-terminus (Left). Overall 3-dimensional organization of human KCC2 (Right). Detailed view of the localization of phosphorylated Thr1007 and Thr1009. Dashed lines indicate missing density and thus lack of structural information. The 3D reconstruction of KCC2 was generated using cryo-EM (Chi X. et al., 2020). 3D visualization was performed using Mol* Viewer in PDB (Sehnal et al., 2021).

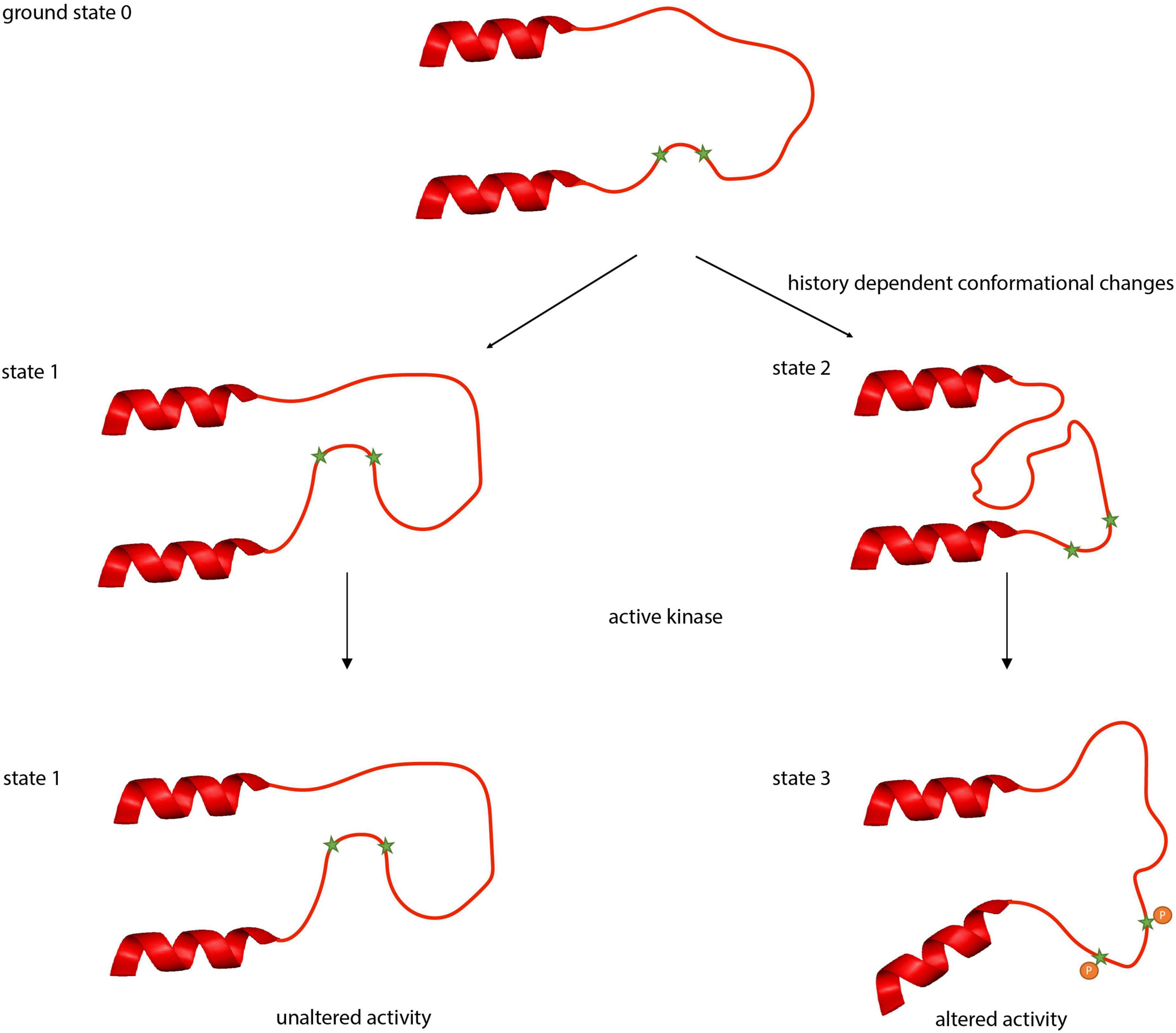

The clusters of phospho-sites might not only enable the transporters to integrate multiple signaling pathways but also to regulate activity in a history-dependent manner. Intrinsically disordered regions can adopt a variety of conformations each with distinct binding affinities and specificity properties (Oldfield et al., 2008; Forman-Kay and Mittag, 2013; Hsu et al., 2013; Flock et al., 2014). Thus, starting from a ground state 0, slightly different conformations named states 1 and 2 can be induced by two different physiological states, upon which a signaling pathway will act in different, history-dependent ways. This will induce in one instance a further conformational change resulting in state 3 whereas in the other instance, no further conformational change occurs (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Putative conformational states of the intrinsically disordered regions between α8 and α9 helices in KCC2. Intrinsically disordered regions can adopt a variety of conformational states. Beginning with the ground state 0, different physiological conditions (activity, pH, temperature) can induce different conformational states (states 1 or 2). These conformational changes can result in occlusion (state 1) or deocclusion (state 2) of phospho-sites to signaling pathways. Phosphorylation in the deoccluded state results subsequently in altered transport activity.

Experiments with the kinase inhibitor staurosporine provide evidence for such different conformational states in KCC2. Mutation of the regulatory phospho-sites Ser932 and Thr1009 to either alanine or aspartate abrogates stimulation by staurosporine. In contrast, Ser31, Thr34, and Thr999 represent regulatory phospho-sites where only mutation into alanine or aspartate (Ser31Asp, Thr34Ala, and Thr999Ala) abrogates stimulation, whereas substitution by the other amino acid residue (Ser31Ala, Thr34Asp, and Thr999Asp) maintains sensitivity to staurosporine (Cordshagen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020b). The change in phosphorylation of either of the three sites likely impacts the accessibility of other phospho-sites such as Ser932 and Thr1009 to the action of staurosporine (Cordshagen et al., 2018). One conformational state (state 1) might occlude hidden sites that are final targets of the action of staurosporine, resulting in no further activation of KCC2. The other conformational state (state 2) provides access to phospho-sites that are targeted by the action of this reagent, leading to state 3 (Figure 5). This can result in distinct Cl– transport activities, reflecting the past history, and ultimately in different transformations of the neuronal input-output function (Currin et al., 2020), which relate to phenomena as important and diverse as synaptic integration, the flow of information through neuronal circuits, learning and memory, neural circuit development and diseases. The phospho-site enriched unstructured regions are therefore ideally suited to act as a processor to regulate the output of the transporters by computing signaling from ongoing and past physiological states. This inherent feature of an intrinsically disordered region thus might provide a molecular basis for ionic plasticity.

Furthermore, the properties of intrinsically disordered regions might explain the surprising observation of decreased Ser940 phosphorylation in the presence of the two human pathogenic variants Arg952His and Arg1049Cys (Kahle et al., 2014; Puskarjov et al., 2014; Silayeva et al., 2015; Figure 2). Both variants may cause altered conformation of the unstructured area, resulting in different binding affinities for PKC and PP1 that determine together the amount of Ser940 phosphorylation (Lee et al., 2007, 2011; Kahle et al., 2014). Finally, environmental factors, like changes in temperature, redox-potential and pH can induce conformational changes of intrinsically disordered regions (Kjaergaard et al., 2010; Flock et al., 2014; Jephthah et al., 2019). This might explain the temperature-dependency of KCC2, since increasing the temperature to 37°C decreases KCC2 activity (Hartmann and Nothwang, 2011).

(De)phosphorylation of phospho-sites most likely results in conformational reorganization as observed for other CCC family members. Many of the phospho-sites in the C-terminus of KCC2 are localized in an unstructured area. Due to biophysical properties of such areas, this part of KCC2 might serve a dual role. It might represent a platform for integrating different signaling pathways and simultaneously constitute a flexible, highly dynamic linker that can survey a wide variety of distinct conformations (Forman-Kay and Mittag, 2013). As each conformation can have distinct binding affinities and specificity properties, this may enable regulation of [Cl–]i and thus the ionic driving force in a history-dependent way and explain long-range effects of mutations on phospho-sites.

A-MH and HN equally wrote the manuscript. A-MH generated all of the figures. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The manuscript was supported by the funding of the DFG (grant numbers: HA6338/2-1 to A-MH and 428-4/1 and 428-4/2 to HN). Our institution has an open access for the publication (library).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

A-MH and HN gratefully acknowledge long time support by the DFG.

CCC, cation chloride cotransporter; KCC, K+, Cl–cotransporter, NKCC, Na+, K+, Cl– cotransporter, GABA, gamma-aminobutyric aci, TM, transmembrane domain.

Achilles, K., Okabe, A., Ikeda, M., Shimizu-Okabe, C., Yamada, F., Fukuda, A., et al. (2007). Kinetic properties of Cl– uptake mediated by Na+-dependent K+-2Cl– cotransport in immature rat neocortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 27, 8616–8627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5041-06.2007

Adadey, S. M., Schrauwen, I., Aboagye, E. T., Bharadwaj, T., Esoh, K. K., Basit, S., et al. (2021). Further confirmation of the association of SLC12A2 with non-syndromic autosomal-dominant hearing impairment. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 1169–1175. doi: 10.1038/s10038-021-00954-6

Akerman, C. J., and Cline, H. T. (2006). Depolarizing GABAergic conductances regulate the balance of excitation to inhibition in the developing retinotectal circuit in vivo. J. Neurosci. 26, 5117–5130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0319-06.2006

Alessi, D. R., Gourlay, R., Campbell, D. G., Deak, M., Macartney, T. J., Kahle, K. T., et al. (2014a). The WNK-regulated SPAK/OSR1 kinases directly phosphorylate and inhibit the K+–Cl- co-transporters. Biochem. J. 458(Pt 3), 559–573. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131478

Alessi, D. R., Zhang, J., Khanna, A., Hochdörfer, T., Shang, Y., and Kahle, K. T. (2014b). The WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway: master regulator of cation-chloride cotransporters. Sci. Signal. 7:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005365

Arion, D., and Lewis, D. A. (2011). Altered expression of regulators of the cortical chloride transporters NKCC1 and KCC2 in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 21–31. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.114

Balakrishnan, V., Becker, M., Löhrke, S., Nothwang, H. G., Güresir, E., and Friauf, E. (2003). Expression and function of chloride transportes during development of inhibitory neurotransmission in the auditory brainstem. J. Neurosci. 23, 4134–4145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04134.2003

Balena, T., and Woodin, M. A. (2008). Coincident pre-and postsynaptic activity downregulates NKCC1 to hyperpolarize ECl during development. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 2402–2412. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06194.x

Ben-Ari, Y. (2017). NKCC1 chloride importer antagonists attenuate many neurological and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 40, 536–554. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.07.001

Ben-Ari, Y., Cherubini, E., Corradetti, R., and Gaiarsa, J.-L. (1983). Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J. Physiol. 416, 303–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762

Ben-Ari, Y., Gaiarsa, J.-L., Tyzio, R., and Khazipov, R. (2007). GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiology 87, 1215–1284. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006

Blaesse, P., Airaksinen, M. S., Rivera, C., and Kaila, K. (2009). Cation-chloride cotransporters and neuronal function. Cell 61, 820–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.003

Boehr, D. D., Nussinov, R., and Wright, P. E. (2009). The role of dynamic conformational ensembles in biomolecular recognition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 789–796. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.232

Bormann, B. J., Hamill, O. P., and Sackmann, B. (1987). Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and y-aminobutyric acid in mouse cultured spinal neurones. J. Physiol. 385, 243–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016493

Boulenguez, P., Liabeuf, S., Bos, R., Bras, H., Jean-Xavier, C., Brocard, C., et al. (2010). Down-regulation of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 contributes to spasticity after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 16, 302–307. doi: 10.1038/nm.2107

Chamma, I., Chevy, Q., Poncer, J. C., and Lévi, S. (2012). Role of the neuronal K-Cl co-transporter KCC2 in inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 6:5. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2012.00005

Chamma, I., Heubl, M., Chevy, Q., Renner, M., Moutkine, I., Eugène, E., et al. (2013). Activity-dependent regulation of the K/Cl transporter KCC2 membrane diffusion, clustering, and function in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 33, 15488–15503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5889-12.2013

Cherubini, E., Gaiarsa, J.-L., and Ben-Ari, Y. (1991). GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 14, 515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-D

Cherubini, E., Rovira, C., Gaiarsa, J.-L., Corradetti, R., and Ben-Ari, Y. (1990). GABA mediated excitation in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurons. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 8, 481–490. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(90)90080-L

Chew, T. A., Zhang, J., and Feng, L. (2021). High-resolution views and transport mechanisms of the NKCC1 and KCC transporters. J. Mol. Biol. 433:167056. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167056

Chi, G., Ebenhoch, R., Man, H., Tang, H., Tremblay, L. E., Reggiano, G., et al. (2021). Phospho-regulation, nucleotide binding and ion access control in potassium-chloride cotransporters. EMBO J. 40:e107294. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020107294

Chi, X., Li, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Su, Q., and Zhou, Q. (2020). Molecular basis for regulation of human potassium chloride cotransporters. bioRxiv [Preprint] doi: 10.1101/2020.02.22.960815

Chi, X., Li, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Su, Q., and Zhou, Q. (2021). Cryo-EM structures of the full-length human KCC2 and KCC3 cation-chloride cotransporters. Cell Res. 31, 482–484. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00437-x

Cohen, I., Navarro, V., Clemenceau, S., Baulac, M., and Miles, R. (2002). On the origin of interictal activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy in vitro. Science 298, 1418–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.1076510

Côme, E., Heubl, M., Schwartz, E. J., Poncer, J. C., and Lévi, S. (2019). Reciprocal regulation of KCC2 trafficking and synaptic activity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13:48. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00048

Conway, L. C., Cardarelli, R. A., Moore, Y. E., Jones, K., McWilliams, L. J., Baker, D. J., et al. (2017). N-Ethylmaleimide increases KCC2 cotransporter activity by modulating transporter phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 21253–21263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.817841

Cordshagen, A., Busch, W., Winklhofer, M., Nothwang, H. G., and Hartmann, A.-M. (2018). Phosphoregulation of the intracellular termini of K+-Cl- cotransporter 2 (KCC2) enables flexible control of its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 16984–16993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004349

Coull, J. A. M., Boudreau, D., Bachand, K., Prescott, S. A., Nault, F., Sik, A., et al. (2003). Trans-synaptic shift in anion gradient in spinal lamina I neurons as a mechanism of neuropathic pain. Nature 424, 938–942. doi: 10.1038/nature01868

Currin, C. B., Trevelyan, A. J., Akerman, C. J., and Raimondo, J. V. (2020). Chloride dynamics alter the input-output properties of neurons. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16:e1007932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007932

Darman, R. B., and Forbush, B. (2002). A regulatory locus of phosphorylation in the N terminus of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter, NKCC1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37542–37550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206293200

de Los Heros, P., Alessi, D. R., Gourlay, R., Campbell, D. G., Deak, M., Macartney, T. J., et al. (2014). The WNK-regulated SPAK/OSR1 kinases directly phosphorylate and inhibit the K+-Cl– co-transporters. Biochem. J. 458, 559–573. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131478

Delpire, E. (2000). Cation-chloride cotransporter in neuronal communication. News Physiol. Sci. 15, 309–312. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.309

Delpire, E., Lu, J., England, R., Dull, C., and Thorne, T. (1999). Deafness and imbalance associated with inactivation of the secretory Na-K-2Cl co-transporter. Nat. Genet. 22, 192–195. doi: 10.1038/9713

Delpire, E., and Mount, D. B. (2002). Human and murine phenotypes associated with defects in cation-chloride-cotransporter. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 803–843. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155847

Delpire, E., Wolfe, L., Flores, B., Koumangoye, R., Schornak, C. C., Omer, S., et al. (2016). A patient with multisystem dysfunction carries a truncation mutation in human SLC12A2, the gene encoding the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, NKCC1. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2:a001289. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a001289

Dowd, B. F. X., and Forbush, B. (2003). PASK (Proline-Alanine-rich-related Kinase), a regulatory kinase of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC1). J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27347–27353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301899200

Doyon, N., Vinay, L., Prescott, S. A., and De Koninck, Y. (2016). Chloride regulation: a dynamic equilibrium crucial for synaptic inhibition. Neuron 89, 1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.02.030

Dzhala, V. I., Talos, D. M., Sdrulla, D. A., Brumback, A. C., Mathews, G. C., Benke, T. A., et al. (2005). NKCC1 transporter facilitates seizures in the developing brain. Nat. Med. 11, 1205–1213. doi: 10.1038/nm1301

Ehrlich, I., Löhrke, S., and Friauf, E. (1999). Shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing glycine action in rat auditory neurones is due to age-dependent Cl– regulation. J. Physiol. 520, 121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00121.x

Eichler, S. A., and Meier, J. C. (2008). EI balance and human diseases-from molecules to networking. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 1:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.002.2008

Flemmer, A. W., Gimenz, I., Dowd, B. F. X., Darman, R. B., and Forbush, B. (2002). Activation of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter NKCC1 detected with a Phospho-specific antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37551–37558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206294200

Flock, T., Weatheritt, R. J., Latysheva, N. S., and Babu, M. M. (2014). Controlling entropy to tune the functions of intrinsically disordered regions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 26, 62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.05.007

Forman-Kay, J. D., and Mittag, T. (2013). From sequence and forces to structure, function, and evolution of intrinsically disordered proteins. Structure 21, 1492–1499.

Friedel, P., Kahle, K. T., Zhang, J., Hertz, N., Pisella, L. I., Buhler, E., et al. (2015). WNK1-regulated inhibitory phosphorylation of the KCC2 cotransporter maintains the depolarizing action of GABA in immature neurons. Sci. Signal. 8:ra65. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa0354

Fukuda, A., and Watanabe, M. (2019). Pathogenic potential of human SLC12A5 variants causing KCC2 dysfunction. Brain Res. 1710, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.12.025

Gagnon, K. B., and Delpire, E. (2013). Physiology of SLC12 transporters: lessons from inherited human genetic mutations and genetically engineered mouse knockouts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C693–C714. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00350.2012

Gagnon, K. B., England, R., and Delpire, E. (2007). A single binding motif is required for SPAK activation of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 20, 131–142. doi: 10.1159/000104161

Gagnon, K. B. E., England, R., and Delpire, E. (2006). Characterization of SPAK and OSR1, regulatory kinases of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 689–698. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.689-698.2006

Geng, Y., Hoke, A., and Delpire, E. (2009). The Ste20 Kinases SPAK and OSR1 regulate NKCC1 function in sensory neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14020–14028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900142200

Hadjikhani, N., Johnels, J. Å., Lassalle, A., Zürcher, N. R., Hippolyte, L., Gillberg, C., et al. (2018). Bumetanide for autism: more eye contact, less amygdala activation. Sci. Rep. 8:3602. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21958-x

Hadjikhani, N., Zürcher, N. R., Rogier, O., Ruest, T., Hippolyte, L., Ben-Ari, Y., et al. (2015). Improving emotional face perception in autism with diuretic bumetanide: a proof-of-concept behavioral and functional brain imaging pilot study. Autism 19, 149–157. doi: 10.1177/1362361313514141

Hampel, P., Johne, M., Gailus, B., Vogel, A., Schidlitzki, A., Gericke, B., et al. (2021). Deletion of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC1 results in a more severe epileptic phenotype in the intrahippocampal kainate mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 152:105297. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2021.105297

Hartmann, A.-M., and Nothwang, H. G. (2011). Opposite temperature effect on transport activity of KCC2/KCC4 and N (K) CCs in HEK-293 cells. BMC Res. Notes 4:526. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-526

Hartmann, A.-M., and Nothwang, H. G. (2014). Molecular and evolutionary insights into the structural organization of cation chloride cotransporters. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:470. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00470

Henneberger, C., Bard, L., Panatier, A., Reynolds, J. P., Kopach, O., Medvedev, N. I., et al. (2020). LTP induction boosts glutamate spillover by driving withdrawal of perisynaptic astroglia. Neuron 108, 919–936.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.030

Heubl, M., Zhang, J., Pressey, J. C., Al Awabdh, S., Renner, M., Gomez-Castro, F., et al. (2017). GABA A receptor dependent synaptic inhibition rapidly tunes KCC2 activity via the Cl–sensitive WNK1 kinase. Nat. Commun. 8:1776. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01749-0

Hsu, W. L., Oldfield, C. J., Xue, B., Meng, J., Huang, F., Romero, P., et al. (2013). Exploring the binding diversity of intrinsically disordered proteins involved in one-to-many binding. Protein Sci. 22, 258–273. doi: 10.1002/pro.2207

Huberfeld, G., Wittner, L., Clemenceau, S., Baulac, M., Kaila, K., Miles, R., et al. (2007). Perturbed chloride homeostasis and GABAergic signaling in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 27, 9866–9873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-07.2007

Hübner, C. A., Lorke, D. E., and Hermans-Borgmeyer, I. (2001a). Expression of the Na-K-2Cl-cotransporter NKCC1 during mouse development. Mech. Dev. 102, 267–269. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00309-4

Hübner, C. A., Stein, V., Hermans-Borgmeyer, I., Meyer, T., Ballanyi, K., and Jentsch, T. J. (2001b). Disruption of KCC2 reveals an essential role of K-Cl cotransport alreadys in early synaptic inhibition. Neuron 30, 515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00297-5

Hyde, T. M., Lipska, B. K., Ali, T., Mathew, S. V., Law, A. J., Metitiri, O. E., et al. (2011). Expression of GABA signaling molecules KCC2, NKCC1, and GAD1 in cortical development and schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 31, 11088–11095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1234-11.2011

Ikeda, K., Onimaru, H., Yamada, J., Inoue, K., Ueno, S., Onaka, T., et al. (2004). Malfunction of respiratory-related neuronal activity in Na+, K+-ATPase L2 subunit-deficient mice is attributable to abnormal Cl– homeostasis in brainstem neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 10693–10701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2909-04.2004

Inoue, K., Furukawa, T., Kumada, T., Yamada, J., Wang, T., Inoue, R., et al. (2012). Taurine inhibits K+-Cl- cotransporter KCC2 to regulate embryonic Cl- homeostasis via With-no-lysine (WNK) protein kinase signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20839–20850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.319418

Inoue, K., Yamada, J., Ueno, S., and Fukuda, A. (2006). Brain-type creatine kinase activates neuron-specific K+-Cl- co-trasnporter KCC2. J. Biochem. 96, 598–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03560.x

Jephthah, S., Staby, L., Kragelund, B., and Skepo, M. (2019). Temperature dependence of intrinsically disordered proteins in simulations: what are we missing? J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 2672–2683. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01281

Kahle, K. T., Deeb, T. Z., Puskarjov, M., Silayeva, L., Liang, B., Kaila, K., et al. (2013). Modulation of neuronal activity by phosphorylation of the K–Cl cotransporter KCC2. Trends Neurosci. 36, 726–737. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.08.006

Kahle, K. T., Merner, N. D., Friedel, P., Silayeva, L., Liang, B., Khanna, A., et al. (2014). Genetically encoded impairment of neuronal KCC2 cotransporter function in human idiopathic generalized epilepsy. EMBO Rep. 15, 766–774. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438840

Kaila, K. (1994). Ionic basis of GABA A receptor channel function in the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 42, 489–537. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90049-3

Kaila, K., Price, T. J., Payne, J. A., Puskarjov, M., and Voipio, J. (2014). Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 637–654. doi: 10.1038/nrn3819

Kandler, K., and Friauf, E. (1995). Development of glycinergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission on the auditory brainstem of perinatal rats. J. Neurosci. 15, 6890–6904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06890.1995

Khirug, S., Huttu, K., Ludwig, A., Smirnov, S., Voipo, J., Rivera, C., et al. (2005). Distinct properties of functional KCC2 expression in immature mouse hippocampal neurons in culture and in acute slices. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 899–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03886.x

Kilb, W. (2020). “The relation between neuronal chloride transpor ter activities, GABA inhibition, and neuronal activity,” in Neuronal Chloride Transporters in Health and Disease, ed. X. Tang (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 43–57. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815318-5.00003-0

Kim, J. Y., Liu, C. Y., Zhang, F., Duan, X., Wen, Z., Song, J., et al. (2012). Interplay between DISC1 and GABA signaling regulates neurogenesis in mice and risk for schizophrenia. Cell 148, 1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.037

Kjaergaard, M., Nørholm, A. B., Hendus-Altenburger, R., Pedersen, S. F., Poulsen, F. M., and Kragelund, B. B. (2010). Temperature-dependent structural changes in intrinsically disordered proteins: formation of α−helices or loss of polyproline II? Protein Sci. 19, 1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/pro.435

Kopp-Scheinpflug, C., Tozer, A. J., Robinson, S. W., Tempel, B. L., Hennig, M. H., and Forsythe, I. D. (2011). The sound of silence: ionic mechanisms encoding sound termination. Neuron 71, 911–925. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.028

Korkhov, V. M., Farhan, H., Freissmuth, M., and Sitte, H. H. (2004). Oligomerization of the y-aminobutyric acid transporter-1is driven by an interplay of polar and hydrophobic interactions in transmembrane helix II. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55728–55736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409449200

Koumangoye, R., Bastarache, L., and Delpire, E. (2021). NKCC1: newly found as a human disease-causing ion transporter. Function 2:zqaa028. doi: 10.1093/function/zqaa028

Lamsa, K. P., Kullmann, D. M., and Woodin, M. A. (2010). Spike-timing dependent plasticity in inhibitory circuits. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2:8. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00008

Lee, H. C., Jurd, R., and Moss, S. J. (2010). Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the membrane trafficking of the potassium chloride co-transporter KCC2. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 45, 173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.06.008

Lee, H. H., Deeb, T. Z., Walker, J. A., Davies, P. A., and Moss, S. J. (2011). NMDA receptor activity downregulates KCC2 resulting in depolarizing GABA A receptor–mediated currents. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 736–743. doi: 10.1038/nn.2806

Lee, H. H. C., Walker, J. A., Jeffrey, R. W., Goodier, R. J., Payne, J. A., and Moss, S. J. (2007). Direct PKC-dependent phosphorylation regulates the cell surface stability and activity of the potassium chloride cotransporter, KCC2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29777–29784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705053200

Lemonnier, E., and Ben-Ari, Y. (2010). The diuretic bumetanide decreases autistic behaviour in five infants treated during 3 months with no side effects. Acta Paediatr. 99, 1885–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01933.x

Lemonnier, E., Degrez, C., Phelep, M., Tyzio, R., Josse, F., Grandgeorge, M., et al. (2012). A randomised controlled trial of bumetanide in the treatment of autism in children. Transl. Psychiatry 2:e202. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.124

Lemonnier, E., Villeneuve, N., Sonie, S., Serret, S., Rosier, A., Roue, M., et al. (2017). Effects of bumetanide on neurobehavioral function in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 7:e1124. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.101

Liedtke, C. M., Hubbard, M., and Wang, X. (2003). Stability of actin cytoskeleton and PKC-δ binding to actin regulate NKCC1 function in airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, C487–C496. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00357.2002

Liu, R., Wang, J., Liang, S., Zhang, G., and Yang, X. (2020). Role of NKCC1 and KCC2 in epilepsy: from expression to function. Front. Neurol. 10:1407. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01407

Löhrke, S., Srinivasan, G., Oberhofer, M., Doncheva, E., and Friauf, E. (2005). Shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing glycine action occurs at different perinatal ages in superior olivary complex nuclei. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 2708–2722. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04465.x

Löscher, W., and Kaila, K. (2021). CNS pharmacology of NKCC1 inhibitors. Neuropharmacology 205:108910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108910

Luhmann, H. J., and Prince, D. A. (1991). Postnatal maturation of the GABAergic system in rat neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 65, 247–263. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.247

Mahadevan, V., and Woodin, M. A. (2016). Regulation of neuronal chloride homeostasis by neuromodulators. J. Physiol. 594, 2593–2605. doi: 10.1113/JP271593s

Markkanen, M., Ludwig, A., Khirug, S., Pryazhnikov, E., Soni, S., Khiroug, L., et al. (2017). Implications of the N-terminal heterogeneity for the neuronal K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 function. Brain Res. 1675, 87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.08.034

McNeill, A., Iovino, E., Mansard, L., Vache, C., Baux, D., Bedoukian, E., et al. (2020). SLC12A2 variants cause a neurodevelopmental disorder or cochleovestibular defect. Brain 143, 2380–2387. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa176

Medina, I., Friedel, P., Rivera, C., Kahle, K. T., Kourdougli, N., Uvarov, P., et al. (2014). Current view on the functional regulation of the neuronal K+-Cl- cotransporter KCC2. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:27. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00027

Merner, N. D., Chandler, M. R., Bourassa, C., Liang, B., Khanna, A. R., Dion, P., et al. (2015). Regulatory domain or CpG site variation in SLC12A5, encoding the chloride transporter KCC2, in human autism and schizophrenia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:386. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00386

Merner, N. D., Mercado, A., Khanna, A. R., Hodgkinson, A., Bruat, V., Awadalla, P., et al. (2016). Gain-of-function missense variant in SLC12A2, encoding the bumetanide-sensitive NKCC1 cotransporter, identified in human schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 77, 22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.016

Möhler, H. (2006). GABAA receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 326, 505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3

Monette, M. Y., and Forbush, B. (2012). Regulatory activation is accompanied by movement in the C terminus of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC1). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2210–2220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.309211

Monette, M. Y., Somasekharan, S., and Forbush, B. (2014). Molecular motions involved in Na-K-Cl cotransporter-mediated ion transport and transporter activation revealed by internal cross-linking between transmembrane domains 10 and 11/12. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 7569–7579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.542258

Moore, Y. E., Conway, L. C., Wobst, H. J., Brandon, N. J., Deeb, T. Z., and Moss, S. J. (2019). Developmental regulation of KCC2 phosphorylation has long-term impacts on cognitive function. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12:173. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00173

Moore, Y. E., Deeb, T. Z., Chadchankar, H., Brandon, N. J., and Moss, S. J. (2018). Potentiating KCC2 activity is sufficient to limit the onset and severity of seizures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 10166–10171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810134115

Moore, Y. E., Kelley, M. R., Brandon, N. J., Deeb, T. Z., and Moss, S. J. (2017). Seizing control of KCC2: a new therapeutic target for epilepsy. Trends Neurosci. 40, 555–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.06.008

Morgan, A., Pelliccione, G., Ambrosetti, U., Dell’Orco, D., and Girotto, G. (2020). SLC12A2: a new gene associated with autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss in humans. Hearing Balance Commun. 18, 149–151. doi: 10.1038/s10038-021-00954-6

Moriguchi, T., Urushiyama, S., Hisamoto, N., Iemura, S.-I., Uchida, S., Natsume, T., et al. (2005). WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42685–42693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510042200

Muñoz, A., Méndez, P., DeFelipe, J., and Alvarez-Leefmans, F. J. (2007). Cation-chloride cotransporters and GABA-ergic innervation in the human epileptic hippocampus. Epilepsia 48, 663–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00986.x

Mutai, H., Wasano, K., Momozawa, Y., Kamatani, Y., Miya, F., Masuda, S., et al. (2020). Variants encoding a restricted carboxy-terminal domain of SLC12A2 cause hereditary hearing loss in humans. PLoS Genet. 16:e1008643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008643

Muzyamba, M., Cossins, A., and Gibson, J. (1999). Regulation of Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransport in turkey red cells: the role of oxygen tension and protein phosphorylation. J. Physiol. 517, 421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0421t.x

Oldfield, C. J., Meng, J., Yang, J. Y., Yang, M. Q., Uversky, V. N., and Dunker, A. K. (2008). Flexible nets: disorder and induced fit in the associations of p53 and 14-3-3 with their partners. BMC Genomics 9, (Suppl. 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-S1-S1

Ormond, J., and Woodin, M. A. (2009). Disinhibition mediates a form of hippocampal long-term potentiation in area CA1. PLoS One 4:e7224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007224

Owens, D. F., Boyce, L. H., Davis, M. B. E., and Kriegstein, A. R. (1996). Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J. Neurosci. 16, 6416–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996

Palma, E., Amici, M., Sobrero, F., Spinelli, G., Di Angelantonio, S., Ragozzino, D., et al. (2006). Anomalous levels of Cl- transporters in the hippocampal subiculum from temporal lobe epilepsy patients make GABA excitatory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8465–8468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602979103

Papp, E., Rivera, C., Kaila, K., and Freund, T. F. (2008). Relationship between neuronal vulnerability and potassium-chloride cotransporter 2 immunoreactivity in hippocampus following transient forebrain ischemia. Neuroscience 154, 677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.072

Payne, J. A., Rivera, C., Voipo, J., and Kaila, K. (2003). Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal communication, development and trauma. Trends Neurosci. 26, 199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00068-7

Pellegrino, C., Gubkina, O., Schaefer, M., Becq, H., Ludwig, A., Mukhtarov, M., et al. (2011). Knocking down of the KCC2 in rat hippocampal neurons increases intracellular chloride concentration and compromises neuronal survival. J. Physiol. 589, 2475–2496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203703

Pisella, L. I., Gaiarsa, J.-L., Diabira, D., Zhang, J., Khalilov, I., Duan, J., et al. (2019). Impaired regulation of KCC2 phosphorylation leads to neuronal network dysfunction and neurodevelopmental pathology. Sci. Signal. 12:eaay0300. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aay0300

Puskarjov, M., Seja, P., Heron, S. E., Williams, T. C., Ahmad, F., Iona, X., et al. (2014). A variant of KCC 2 from patients with febrile seizures impairs neuronal Cl- extrusion and dendritic spine formation. EMBO Rep. 15, 723–729. doi: 10.1002/embr.201438749

Rahmati, N., Hoebeek, F. E., Peter, S., and De Zeeuw, C. I. (2018). Chloride homeostasis in neurons with special emphasis on the olivocerebellar system: differential roles for transporters and channels. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12:101. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00101

Randall, J., Thorne, T., and Delpire, E. (1997). Partial cloning and characterization of Slc12a2: the gene encoding the secretory Na+-K+-2Cl– cotransporter. Am. J. Cell Physiol. 273, 1267–1277. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1267

Richardson, C., and Alessi, D. R. (2008). The regulation of salt transport and blood pressure by the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signalling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3293–3304. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029223

Richardson, C., Rafiqi, F. H., Karlsson, H. K. R., Moleleki, N., Vandewalle, A., Campbell, D. G., et al. (2008). Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl–cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J. Cell Sci. 121, 675–684. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025312

Rinehart, J., Maksimova, Y. D., Tanis, J. E., Stone, K. L., Hodson, C. A., Zhang, J., et al. (2009). Sites of regulated phosphorylation that control K-Cl cotransporter activity. Cell 138, 525–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.031

Rivera, C., Li, H., Thomas-Crussels, J., Lahtinen, H., Viitanen, T., Nanobashvili, A., et al. (2002). BDNF-induced TrkB activation down-regulates the K+-Cl- cotransporter KCC2 and impairs neuronal Cl- extrusion. J. Cell Biol. 159, 747–752. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209011

Rivera, C., Voipo, J., and Kaila, K. (2005). Two developmental switches in GABAergic signalling: the K+-Cl- cotransporter KCC2 and carbonic anhydrase CAVII. J. Physiol. 562, 27–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077495

Rivera, C., Voipo, J., Payne, J. A., Ruusuvuori, E., Lahtinen, H., Lamsa, K., et al. (1999). The K+/Cl– co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature 397, 251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697

Rohrbough, J., and Spitzer, N. C. (1996). Regulation of intracellular Cl- Levels by Na+-dependent Cl- cotransport distinguishes depolarizing from hyperpolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses in spinal neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 82–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00082.1996

Saitsu, H., Watanabe, M., Akita, T., Ohba, C., Sugai, K., Ong, W. P., et al. (2016). Impaired neuronal KCC2 function by biallelic SLC12A5 mutations in migrating focal seizures and severe developmental delay. Sci. Rep. 6:30072. doi: 10.1038/srep30072

Saraga, F., Balena, T., Wolansky, T., Dickson, C., and Woodin, M. (2008). Inhibitory synaptic plasticity regulates pyramidal neuron spiking in the rodent hippocampus. Neuroscience 155, 64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.009

Savardi, A., Borgogno, M., De Vivo, M., and Cancedda, L. (2021). Pharmacological tools to target NKCC1 in brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 42, 1009–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2021.09.005

Sehnal, D., Bittrich, S., Deshpande, M., Svobodová, R., Berka, K., Bazgier, V., et al. (2021). Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W431–W437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab314

Shekarabi, M., Zhang, J., Khanna, A. R., Ellison, D. H., Delpire, E., and Kahle, K. T. (2017). WNK kinase signaling in ion homeostasis and human disease. Cell Metab. 25, 285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.01.007

Shulga, A., Thomas-Crusells, J., Sigl, T., Blaesse, A., Mestres, P., Meyer, M., et al. (2008). Posttraumatic GABAA-mediated [Ca2+] i increase is essential for the induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent survival of mature central neurons. J. Neurosci. 28, 6996–7005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5268-07.2008

Silayeva, L., Deeb, T. Z., Hines, R. M., Kelley, M. R., Munoz, M. B., Lee, H. H., et al. (2015). KCC2 activity is critical in limiting the onset and severity of status epilepticus. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 3523–3528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415126112

Stödberg, T., McTague, A., Ruiz, A. J., Hirata, H., Zhen, J., Long, P., et al. (2015). Mutations in SLC12A5 in epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures. Nat. Commun. 6:8038. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9038

Strange, K., Singer, T. D., Morrison, R., and Delpire, E. (2000). Dependence of KCC2 K-Cl cotransporter activity on a conserved carboxy terminus tyrosine residue. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, 860–867. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C860

Su, G., Kintner, D. B., Flagella, M., Shull, G. E., and Sun, D. (2001). Astrocytes from Na-K-Cl cotransporter null mice exhibit an absence of high [K] o-induced swelling and a decrease in EAA release. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282, C1147–C1160. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00538.2001

Sung, K. W., Kirby, M., McDonald, M. P., Lovinger, D., and Delpire, E. (2000). Abnormal GABAA receptor-mediated currents in dorsal root ganglien neurons isolated from Na-K-2Cl cotransporter null mice. J. Neurosci. 20, 7531–7538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07531.2000

Thastrup, J. O., Rafiqi, F. H., Vitari, A. C., Pozo-Guisado, E., Deak, M., Mehellou, Y., et al. (2012). SPAK/OSR1 regulate NKCC1 and WNK activity: analysis of WNK isoform interactions and activation by T-loop trans-autophosphorylation. Biochem. J. 441, 325–337. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111879

Tillman, L., and Zhang, J. (2019). Crossing the chloride channel: the current and potential therapeutic value of the neuronal K+-Cl-cotransporter KCC2. Biomed Res. Int. 2019:8941046. doi: 10.1155/2019/8941046

Titz, S., Sammler, E. M., and Hormuzdi, S. G. (2015). Could tuning of the inhibitory tone involve graded changes in neuronal chloride transport? Neuropharmacology 95, 321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.03.026

Tóth, K., Lénárt, N., Berki, P., Fekete, R., Szabadits, E., Pósfai, B., et al. (2022). The NKCC1 ion transporter modulates microglial phenotype and inflammatory response to brain injury in a cell-autonomous manner. PLoS Biol. 20:e3001526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001526

Turrigiano, G. G., and Nelson, S. B. (2004). Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327

Tyzio, R., Nardou, R., Ferrari, D. C., Tsintsadze, T., Shahrokhi, A., Eftekhari, S., et al. (2014). Oxytocin-mediated GABA inhibition during delivery attenuates autism pathogenesis in rodent offspring. Science 343, 675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1247190

Uvarov, P., Ludwig, A., Markkanen, M., Pruunsild, P., Kaila, K., Delpire, E., et al. (2007). A novel N-terminal isoform of the neuron-specific K-Cl cotransporter KCC2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30570–30576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705095200

Vanniya, S. P., Chandru, J., Jeffrey, J. M., Rabinowitz, T., Brownstein, Z., Krishnamoorthy, M., et al. (2022). PNPT1, MYO15A, PTPRQ, and SLC12A2-associated genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity among hearing impaired assortative mating families in Southern India. Ann. Hum. Genet. 86, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12442

Virtanen, M. A., Uvarov, P., Hübner, C. A., and Kaila, K. (2020). NKCC1, an elusive molecular target in brain development: making sense of the existing data. Cells 9:2607. doi: 10.3390/cells9122607

Virtanen, M. A., Uvarov, P., Mavrovic, M., Poncer, J. C., and Kaila, K. (2021). The multifaceted roles of KCC2 in cortical development. Trends Neurosci. 44, 378–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2021.01.004

Vitari, A. C., Deak, M., Morrice, N. A., and Alessi, D. R. (2005). The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon’s hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem. J. 391, 17–24. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051180