94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mol. Neurosci., 19 July 2021

Sec. Brain Disease Mechanisms

Volume 14 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2021.701977

This article is part of the Research TopicAutism Spectrum Disorders and Metal DyshomeostasisView all 8 articles

Shadi Shiva1†

Shadi Shiva1† Jalal Gharesouran2†

Jalal Gharesouran2† Hani Sabaie3

Hani Sabaie3 Mohammad Reza Asadi3

Mohammad Reza Asadi3 Shahram Arsang-Jang4

Shahram Arsang-Jang4 Mohammad Taheri5*

Mohammad Taheri5* Maryam Rezazadeh2*

Maryam Rezazadeh2*Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder that involves social interaction defects, impairment of non-verbal and verbal interactions, and limited interests along with stereotypic activities. Its incidence has been increasing rapidly in recent decades. Despite numerous attempts to understand the pathophysiology of ASD, its exact etiology is still unclear. Recent data shows the role of accurate myelination and translational regulation in ASD’s pathogenesis. In this study, we assessed Ermin (ERMN) and Listerin E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 1 (LTN1) genes expression in Iranian ASD patients and age- and gender-matched healthy subjects’ peripheral blood using quantitative real-time PCR to recognize any probable dysregulation in the expression of these genes and propose this disorder’s mechanisms. Analysis of the expression demonstrated a significant ERMN downregulation in total ASD patients compared to the healthy individuals (posterior beta = −0.794, adjusted P-value = 0.025). LTN1 expression was suggestively higher in ASD patients in comparison with the corresponding control individuals. Considering the gender of study participants, the analysis showed that the mentioned genes’ different expression levels were significant only in male subjects. Besides, a significant correlation was found between expression of the mentioned genes (r = −0.49, P < 0.0001). The present study provides further supports for the contribution of ERMN and LTN1 in ASD’s pathogenesis.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a disorder in neurodevelopment that occurs early in life (Parellada et al., 2014). ASD includes poor interpersonal communication, social interaction, and repetitive behaviors (Carlisi et al., 2017). Although an incidence of 1 per 160 kids has been reported throughout the world (Elsabbagh et al., 2012), some varieties are observed in the epidemiology of disorder in distinct world areas (Elsabbagh et al., 2012; Baxter et al., 2015). These variations could be attributed to different techniques, variations in diagnostic or community identification, and probable risk factors (Rice et al., 2012). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), ASD includes two classes of symptoms, the first of which is poor communication and social interaction, and the second is repetitive and restricted behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Therefore, ASD is currently defined as autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), Rett’s disorder, and childhood disintegrative disorder. This broad-spectrum causes diversity in terms of the diagnosis of ASD regarding the previous version of DSM (Harstad et al., 2015). Although the pathophysiology of ASD is not clear, it is assumed that developmental abnormalities in the limbic region, frontal lobe, and putamen lead to imbalanced inhibiting and exciting of neurons. Recently, researchers have revealed that disrupted neuronal connectivity could be associated with alterations in the neurons related to the production of white matter and myelination in different regions of the brain of ASD patients (Galvez-Contreras et al., 2020). Moreover, the disruption of brain translational regulation in ASD progression is increasingly being taken into consideration. New mechanisms, such as ribosome stalling and ribosome quality control (RQC), are highly related to translational regulation. Consequently, all these might play a role in the pathogenesis of these disorders (Hui et al., 2019). According to the literature about blood transcriptome in patients with ASD, extraction of valuable information about the pathophysiology of the disease is possible using peripheral blood. In other words, the best way of assessing systemic alterations is blood investigation because of the role in controlling both centrally and peripherally (Ansel et al., 2017). The etiology of ASD is complicated, heterogeneous, and multifactorial. Diverse environmental factors related to the intrauterine environment and genetic-related risk factors, along with abnormalities in molecular and cellular signaling pathways, might contribute to the etiology of the disorder (Parellada et al., 2014). There has been extended research on autism genetics in recent decades, and findings are increasingly being reported (Thapar and Rutter, 2020).

An oligodendrocyte-specific protein that plays a role in myelination is encoded by Ermin (ERMN) or Juxtanodin. This protein is expressed in a late phase of myelination and is located in the myelin sheath’s outer cytoplasmic lip and the paranodal loops in mature neurons (Brockschnieder et al., 2006). Correct myelination is vital in ASD (Zikopoulos and Barbas, 2010; Broek et al., 2014). Listerin E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 1 (LTN1) encoded protein is a part of the RQC complex. The latter complex plays a role in the degradation of the polybasic-mediated stalled protein (Bengtson and Joazeiro, 2010; Brandman et al., 2012; Defenouillère et al., 2013; Verma et al., 2013). These two genes were selected to further investigate their possible role and interaction in ASD pathogenesis.

Since ASD is a prevalent disorder with a rapidly elevating incidence in previous decades and due to the possible role of ERMN and LTN1 genes in the pathogenesis of this disorder through contributing to disturbances related to oligodendrocytes and RQC pathway disruption and the possible usage of these components in diagnosis, prognosis, and early treatment, we investigated the expression of ERMN and LTN1 performed by qRT-PCR in the peripheral blood of ASD patients.

We carried out this case-control study on 100 participants, including 50 ASD patients and 50 healthy controls matched for age and gender. The current study was approved by the committee of clinical research ethics of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1017). The case group participants were recruited from the Tabriz Children’s Hospital, Iran. A specialized psychiatrist confirmed the diagnosis of all patients based on the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The exclusion criteria entailed being affected by other comorbid genetic syndromes or metabolic disorders. All individuals or their surrogates signed written informed consent, and peripheral blood samples of 5 ml were taken from the participants.

We used a published methodology from our group (Ghafouri-Fard et al., 2021). Total RNA was extracted from whole blood using Hybrid-RTM Blood RNA purification kit (GeneALL, Seoul, South Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Assessment of the extracted RNA in terms of quantity and quality was performed by NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, United States). The synthesis of cDNA was done by the cDNA synthesis Kit (GeneALL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The obtained cDNA was stored at −20°C for further investigation. The designing of specific probes and primers for ERMN, LTN1, and HPRT1 was carried out applying Allele ID 7 software (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, United States). HPRT1 was chosen because it has been introduced as one of the most stable housekeeping genes in autism studies (Anitha et al., 2012; Nardone et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2016). PCR program comprised an initial activation phase for 5 min at 94°C, and 40 cycles at 94°C for 10 s and 60°C for 40 s. Total reaction volumes were 20 μL containing 4 μl of cDNA, 3.5 μl double distilled water, 10 μl of Master Mix 2×, 250 and 900 nM concentrations of probe and each primer, respectively. Table 1 summarizes probes and primers sequences. The qPCR was carried out by the Step OnePlusTM Real-Time PCR and the RealQ Plus2x Master Mix (Ampliqon, Odense, Denmark).

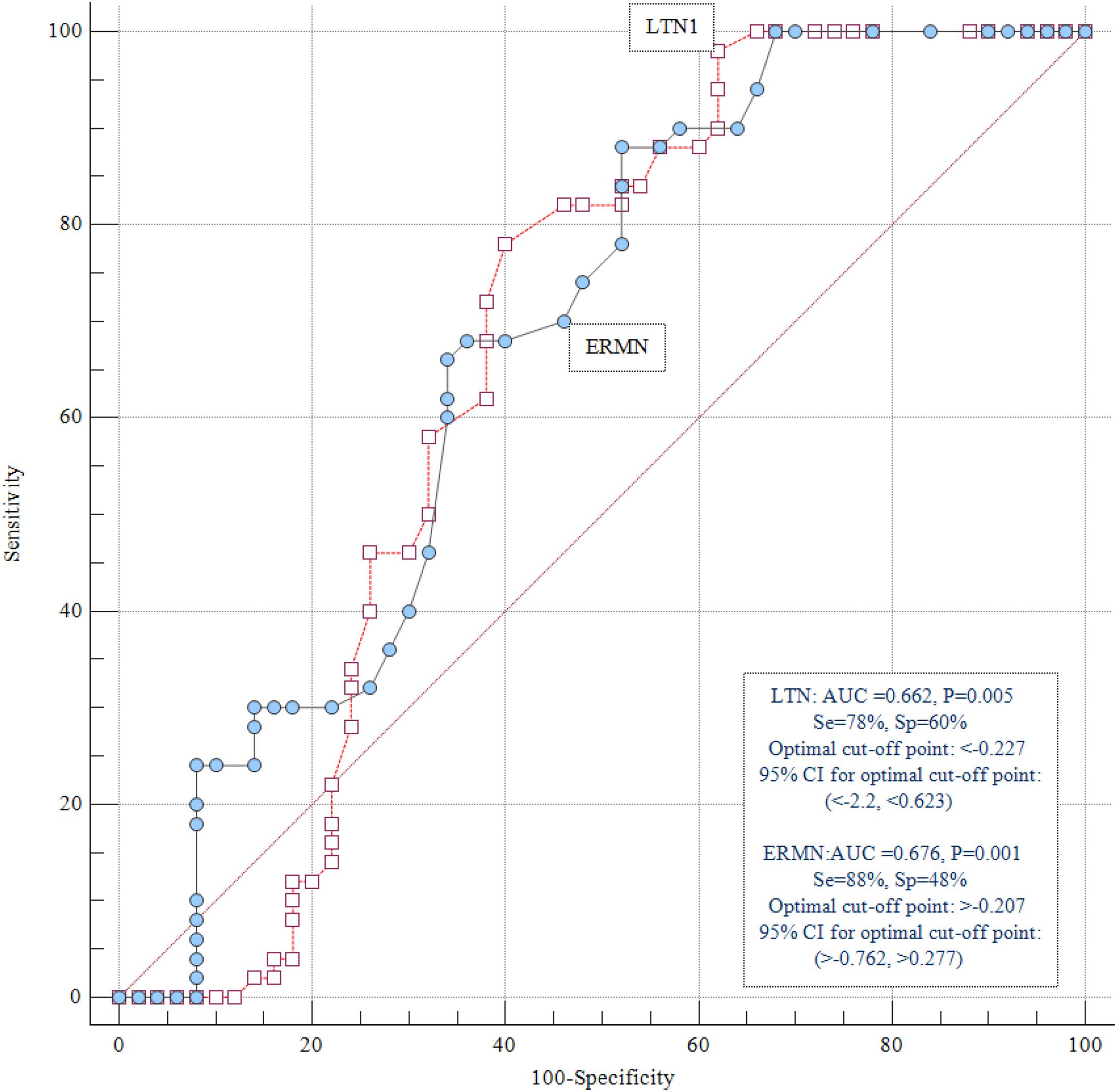

Data were analyzed using Stan, “ggplot2,” “brms,” and pROC packages in the R v.4 software. ERMN and LTN1 genes’ relative expressions were compared in the patients with ASD and the healthy subjects besides their subgroups employing the Bayesian regression model. The effects of gender and age were adjusted. Adjusted P-values were reported. Expression of mentioned genes was also compared between different age groups as well as between males and females. Correlations between the study variables were appraised using Pearson correlation coefficients. The diagnostic power of genes was measured using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Demographic and clinical data of patients and healthy subjects are summarized in Table 2.

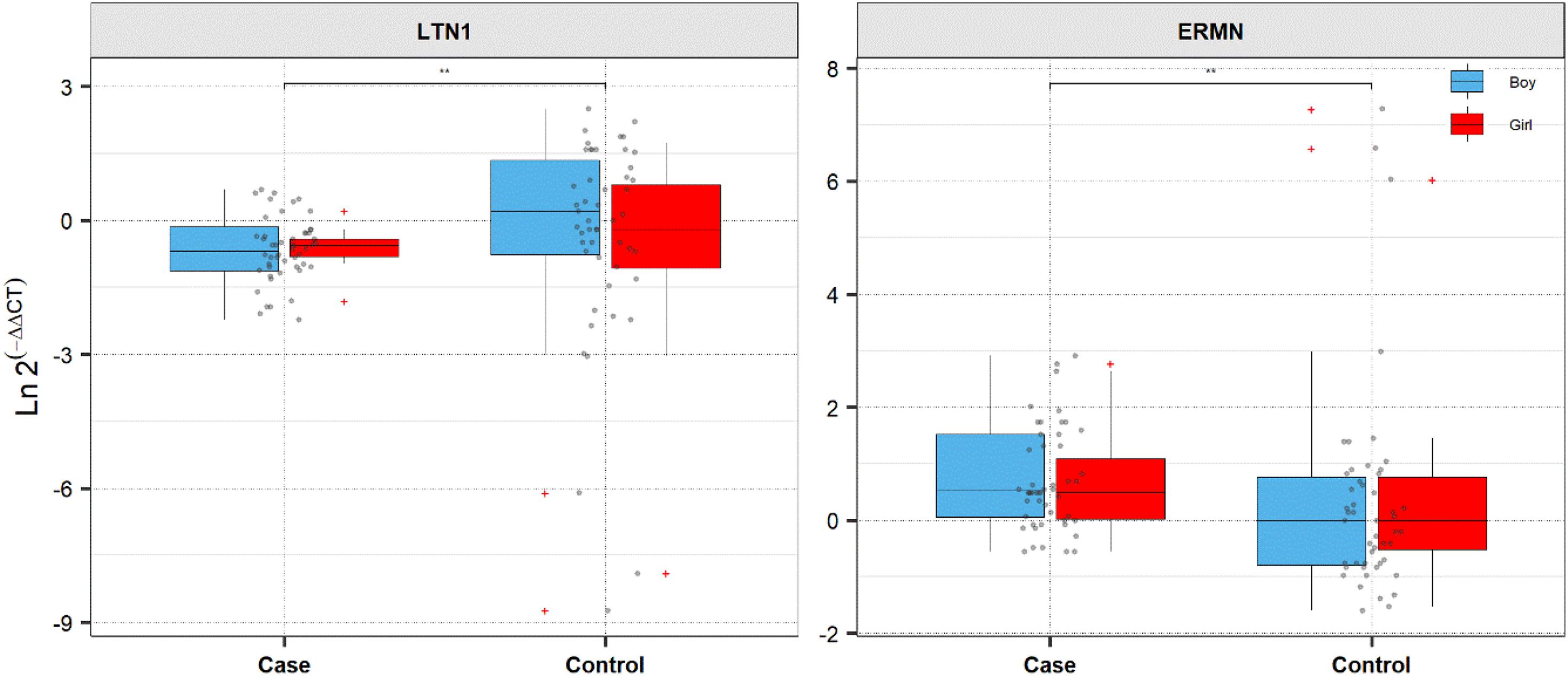

Figure 1 shows ERMN and LTN1 genes’ relative expression levels in patients with ASD and controls.

Figure 1. Expression of ERMN and LTN1 in cases and controls’ blood samples. Ln (EfficiencyΔCt) method was used to calculate expression levels of genes, and the values are depicted as black dots. Means of expression levels and interquartile range are displayed.

The ERMN gene’s expression was suggestively decreased in total ASD cases compared with total controls (posterior beta = −0.794, adjusted P-value = 0.025). Such decreased expression was found between boy subgroups too (posterior beta = −0.938, adjusted P-value = 0.041). On the contrary, LTN1 was higher in total ASD cases vs. controls (posterior beta = 1.317, adjusted P-value = 0.033). Such increased expression was identified in boy cases compared to boy controls (posterior beta = 1.269, adjusted P-value = 0.01). Age of total and boy individuals were associated with LTN1 gene’s expression levels. Tables 3, 4 show the detailed data about the relative expression of ERMN and LTN1, respectively.

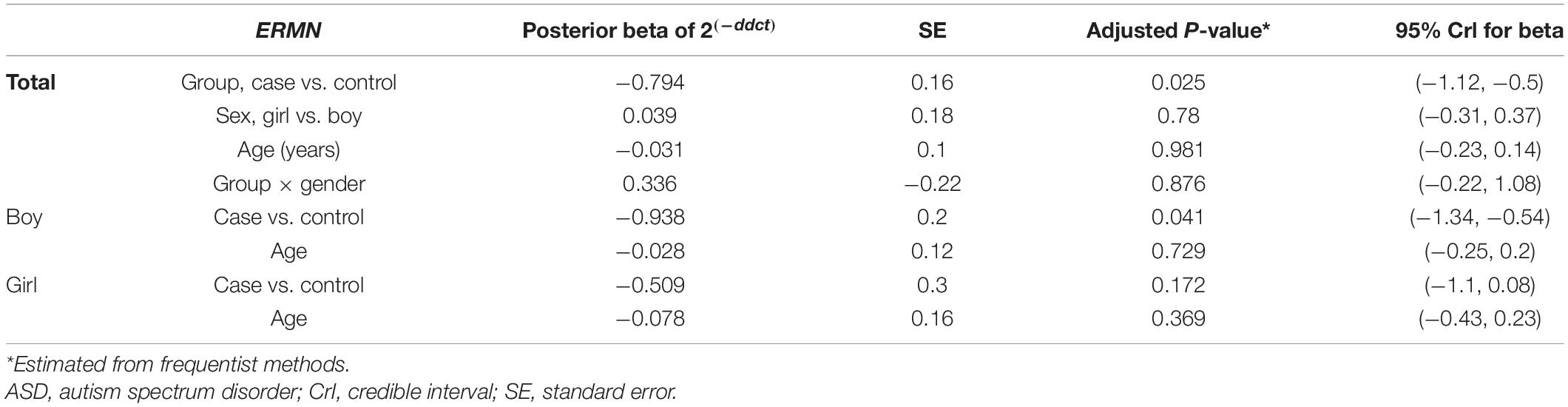

Table 3. Relative levels of ERMN in ASD cases and controls according to the Bayesian quantile regression model.

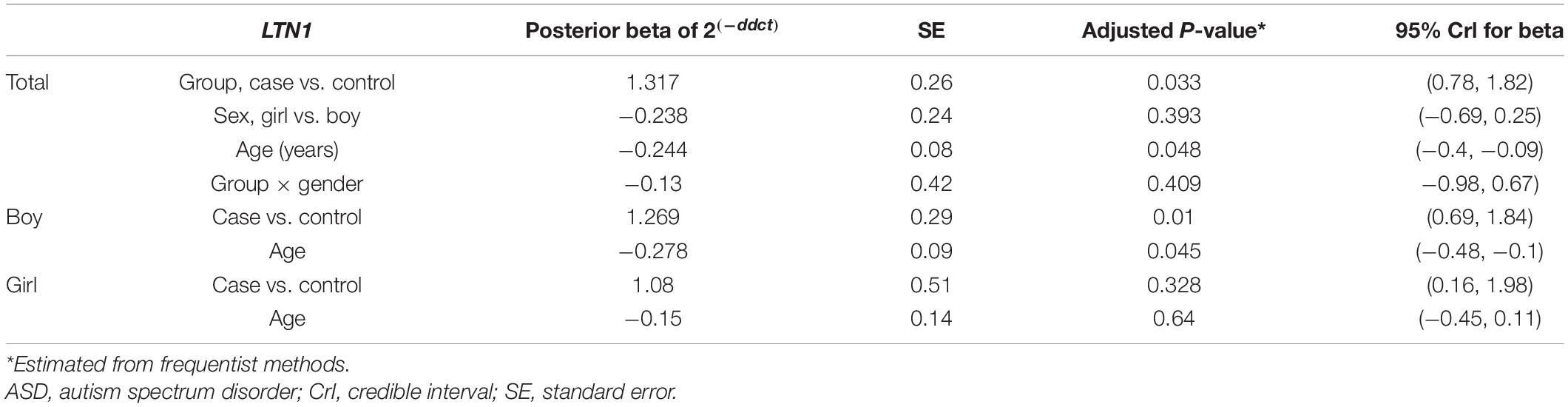

Table 4. Relative levels of LTN1 in ASD cases and controls according to the Bayesian quantile regression model.

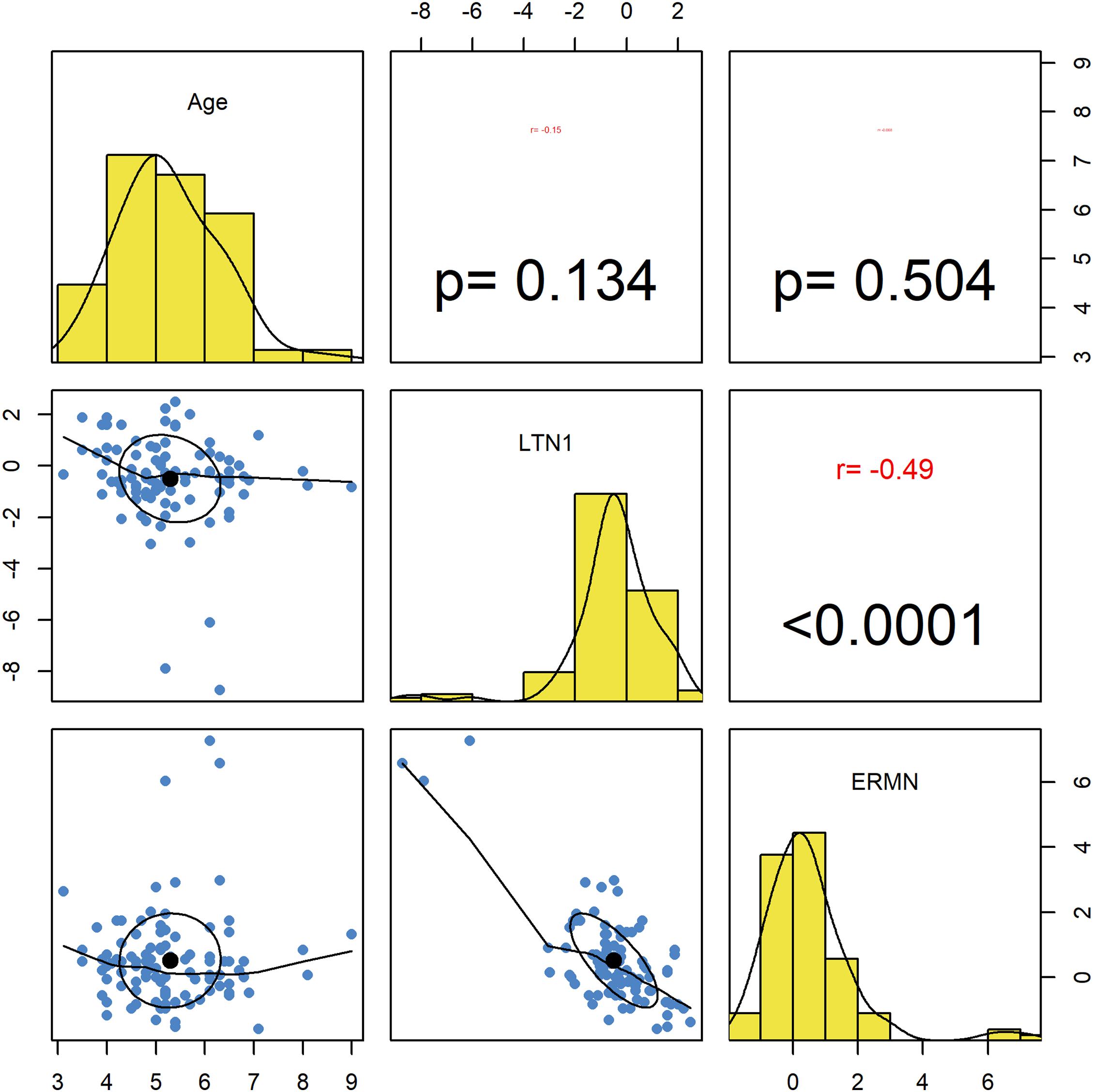

Ermin and LTN1 expression was not correlated with participants’ age. Significant opposite correlations were detected between assessed genes’ expression levels (r = −0.49, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Correlations between ERMN and LTN1 genes’ expression levels and age. The distribution of variables is presented on the diagonal. The lower portion of the diagonal shows bivariate scatter plots with a fitted line. The upper part of the diagonal demonstrates correlation coefficients and P-values.

We assessed the diagnostic power of ERMN and LTN1 to distinguish ASD patients from healthy controls at different threshold settings. ERMN and LTN1 transcript levels presented diagnostic power of 0.676 and 0.662, respectively, based on the area under the ROC curves (Figure 3).

Figure 3. ROC curve analysis. ERMN and LTN1 transcript levels displayed diagnostic power of 0.676 and 0.662, respectively.

Autism spectrum disorder is among the disorders with the highest heritability with the typically multifactorial origin. Strong interest exists in using gene discoveries to achieve insights into ASD’s underlying biology (Quesnel-Vallieres et al., 2019). In the present study, we evaluated ERMN and LTN1 expression in the peripheral blood of ASD patients and healthy individuals.

Lower levels of ERMN were detected in patients with ASD in comparison with the controls. ERMN encoded protein belonging to the ezrin-radixin-moesin family (ERM) was identified as a cytoskeletal protein in 2006. It is demonstrated that this gene stimulating differentiation of oligodendroglial cells and the maintenance of myelin sheath via interaction with myosin phosphatase Rho interacts with protein (Mprip/p116RIP) and inactivates RhoA, which is a GTPase regulating the cytoskeleton rearrangement in differentiating cells (Wang et al., 2020). Remarkably, ERMN is located inside the AUTS5 locus boundaries, which has been repeatedly shown to be linked with autism (Maestrini et al., 2010), language impairment (Bartlett et al., 2004), and IQ (Posthuma et al., 2005). A preceding study showed the overexpression of ERMN in a patient presented with rare genetic variants (meSNV). Furthermore, targeted resequencing showed that higher loads of ERMN were recognized in ASD patients with rare damaging mutations. Function gaining via overexpression and function losing via deleterious mutations suggests gentle gene dosage equilibrium (Homs et al., 2016). Besides, deletions including ERMN were reported in impaired communication and developmental delay patients (Newbury et al., 2009). Expression of ERMN is lower in patients with epilepsy which suggests its role in the epileptogenic process (Wang et al., 2011). Moreover, investigations showed the upregulation of ERMN in the prefrontal cortex (Martins-de-Souza et al., 2009a) and its downregulation in the anterior temporal lobe of SCZ cases’ samples. The downregulation of ERMN may explain why the integrity of the white matter is disrupted in individuals with SCZ (Martins-de-Souza et al., 2009b). Besides, a study suggested that reduced ERMN expression in the leukocytes could cause demyelination in patients with relapsing-remitting MS (Salek Esfahani et al., 2019).

Conversely, the level of LTN1 was higher in patients with ASD in comparison with controls. LTN1 gene acts in a specific pathway for protein quality control by mediating the incomplete polypeptides’ proteolytic targeting produced by ribosome stalling (Martin et al., 2020). The potential mechanism of the LTN1 gene in the pathogenesis of ASD is possibly via disruption of the pathway of RQC, which is shown to influence brain function and is involved in ASD pathogenic processes (Hui et al., 2019). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first report on the expression of LTN1 in ASD patients’ peripheral blood. Only one preceding study recommended according to (1) the essential genes’ importance in the etiology of ASD as presented by their role in the critical stages of development and the increased burden of rare, damaging mutations in patients with ASD; (2) their co-expression with the ASD’s high-confidence genes in the brain; and (3) the genetic evidence suggesting from the transmission and de novo association (TADA) analysis that LTN1 gene is among the strongest candidates whose roles should be evaluated in ASD (Ji et al., 2016).

Furthermore, gender-related differences were found in ERMN and LTN1 genes’ expression levels (Tables 2, 3). The absence of difference in these genes’ expression in female patients might be caused by gender-based differences found in the phenotypes or underlying mechanism of ASD. According to previous reports, affected boys and girls showed phenotypic differences (Van Wijngaarden-Cremers et al., 2014). For example, repetitive and stereotyped behaviors were found to be less common in girls compared with boys (Bölte et al., 2011). These differences are attributable to the underlying mechanisms of sexual dimorphism, such as those associated with the dosage of sex chromosomal genes and the levels of sex hormones (Van Wijngaarden-Cremers et al., 2014).

The present study results suggest that the expression of LTN1 is associated but not correlated with the age of total participants and male participants (Table 3 and Figure 2). Additional studies are required to be further investigate this relationship and interpret such results. Besides, a significant inverse correlation was found between ERMN and LTN1 levels, which shows an interactive network, probably owing to the translational regulation. Moreover, the sex-related differences in ERMN and LTN1 expression (Tables 2, 3) suggest the effect of sex-related factors on this pathway. A robust male bias has been disclosed in ASD with striking consistency, though no mechanism is found yet to account for these sex differences conclusively (Werling and Geschwind, 2013).

Also, we evaluated the LTN1 and ERMN genes’ diagnostic power to differentiate ASD patients from healthy individuals and stated the diagnostic power of 0.676 and 0.662 for ERMN and LTN1, respectively. These data should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small sample size of the present study. If future research supports the present study’s findings, the transcription level of ERMN/LTN1 could be regarded as an ASD disease marker in male patients. Moreover, replicating these experiments in cerebrospinal fluid samples would provide some evidence that the differences in whole blood transcript levels are markers for changes in transcript levels in the nervous system. Taken together, the present study further verified LTN1 and ERMN genes’ putative role in ASD’s pathophysiology, which potentiates the genes as functional studies’ candidates.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1017). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

MT and MR wrote the draft and revised it. SA-J analyzed the data. JG, HS, SS, and MA performed the experiment and data collection. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Anitha, A., Nakamura, K., Thanseem, I., Yamada, K., Iwayama, Y., Toyota, T., et al. (2012). Brain region-specific altered expression and association of mitochondria-related genes in autism. Mol Autism. 3:12. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-12

Ansel, A., Rosenzweig, J. P., Zisman, P. D., Melamed, M., and Gesundheit, B. (2017). Variation in gene expression in autism spectrum disorders: an extensive review of transcriptomic studies. Front. Neurosci. 10:601. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00601

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders (dsm-5®). Verginia: American Psychiatric Association.

Bartlett, C. W., Flax, J. F., Logue, M. W., Smith, B. J., Vieland, V. J., Tallal, P., et al. (2004). Examination of potential overlap in autism and language loci on chromosomes 2, 7, and 13 in two independent samples ascertained for specific language impairment. Hum. Hered. 57, 10–20. doi: 10.1159/000077385

Baxter, A. J., Brugha, T. S., Erskine, H. E., Scheurer, R. W., Vos, T., and Scott, J. G. (2015). The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol. Med. 45, 601–613. doi: 10.1017/s003329171400172x

Bengtson, M. H., and Joazeiro, C. A. P. (2010). Role of a ribosome-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase in protein quality control. Nature. 467, 470–473. doi: 10.1038/nature09371

Bölte, S., Duketis, E., Poustka, F., and Holtmann, M. (2011). Sex differences in cognitive domains and their clinical correlates in higher-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism 15, 497–511. doi: 10.1177/1362361310391116

Brandman, O., Stewart-Ornstein, J., Wong, D., Larson, A., Williams, C. C., Li, G. W., et al. (2012). A ribosome-bound quality control complex triggers degradation of nascent peptides and signals translation stress. Cell. 151, 1042–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.044

Brockschnieder, D., Sabanay, H., Riethmacher, D., and Peles, E. (2006). Ermin, a myelinating oligodendrocyte-specific protein that regulates cell morphology. J. Neurosci. 26, 757–762. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4317-05.2006

Broek, J. A., Guest, P. C., Rahmoune, H., and Bahn, S. (2014). Proteomic analysis of post mortem brain tissue from autism patients: evidence for opposite changes in prefrontal cortex and cerebellum in synaptic connectivity-related proteins. Mol. Autism. 5:41. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-41

Carlisi, C. O., Norman, L. J., Lukito, S. S., Radua, J., Mataix-Cols, D., and Rubia, K. (2017). Comparative multimodal meta-analysis of structural and functional brain abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.10.006

Defenouillère, Q., Yao, Y., Mouaikel, J., Namane, A., Galopier, A., Decourty, L., et al. (2013). Cdc48-associated complex bound to 60S particles is required for the clearance of aberrant translation products. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S.A. 110, 5046–5051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221724110

Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., et al. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 5, 160–179. doi: 10.1002/aur.239

Galvez-Contreras, A. Y., Zarate-Lopez, D., Torres-Chavez, A. L., and Gonzalez-Perez, O. (2020). Role of oligodendrocytes and myelin in the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Brain Sci. 10:951. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10120951

Ghafouri-Fard, S., Eghtedarian, R., Hussen, B. M., Motevaseli, E., Arsang-Jang, S., and Taheri, M. (2021). Expression analysis of VDR-related LncRNAs in autism spectrum disorder. J Mol. Neurosci. 71, 1403–1409. doi: 10.1007/s12031-021-01858-y

Harstad, E. B., Fogler, J., Sideridis, G., Weas, S., Mauras, C., and Barbaresi, W. J. (2015). Comparing Diagnostic Outcomes of Autism Spectrum Disorder Using DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 Criteria. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 1437–1450. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2306-4

Homs, A., Codina-Solà, M., Rodríguez-Santiago, B., Villanueva, C. M., Monk, D., Cuscó, I., et al. (2016). Genetic and epigenetic methylation defects and implication of the ERMN gene in autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 6:e855–e.

Hui, K. K., Chen, Y.-K., Endo, R., and Tanaka, M. (2019). Translation from the ribosome to the clinic: implication in neurological disorders and new perspectives from recent advances. Biomolecules. 9:680. doi: 10.3390/biom9110680

Ji, X., Kember, R. L., Brown, C. D., and Bućan, M. (2016). Increased burden of deleterious variants in essential genes in autism spectrum disorder. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 15054–15059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613195113

Maestrini, E., Pagnamenta, A. T., Lamb, J. A., Bacchelli, E., Sykes, N. H., Sousa, I., et al. (2010). High-density SNP association study and copy number variation analysis of the AUTS1 and AUTS5 loci implicate the IMMP2L-DOCK4 gene region in autism susceptibility. Mol. Psychiatry. 15, 954–968. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.34

Martin, P. B., Kigoshi-Tansho, Y., Sher, R. B., Ravenscroft, G., Stauffer, J. E., Kumar, R., et al. (2020). NEMF mutations that impair ribosome-associated quality control are associated with neuromuscular disease. Nat. Commun. 11:4625.

Martins-de-Souza, D., Gattaz, W. F., Schmitt, A., Rewerts, C., Maccarrone, G., Dias-Neto, E., et al. (2009a). Prefrontal cortex shotgun proteome analysis reveals altered calcium homeostasis and immune system imbalance in schizophrenia. Eur. Arch Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 259, 151–163. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0847-2

Martins-de-Souza, D., Gattaz, W. F., Schmitt, A., Rewerts, C., Marangoni, S., Novello, J. C., et al. (2009b). Alterations in oligodendrocyte proteins, calcium homeostasis and new potential markers in schizophrenia anterior temporal lobe are revealed by shotgun proteome analysis. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 116, 275–289. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0156-y

Nardone, S., Sharan Sams, D., Reuveni, E., Getselter, D., Oron, O., Karpuj, M., et al. (2014). DNA methylation analysis of the autistic brain reveals multiple dysregulated biological pathways. Transl. Psychiatry 4:e433–e.

Newbury, D. F., Warburton, P. C., Wilson, N., Bacchelli, E., and Carone, S. (2009). International Molecular Genetic Study of Autism C, et al. Mapping of partially overlapping de novo deletions across an autism susceptibility region (AUTS5) in two unrelated individuals affected by developmental delays with communication impairment. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 149A, 588–597. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32704

Parellada, M., Penzol, M. J., Pina, L., Moreno, C., González-Vioque, E., Zalsman, G., et al. (2014). The neurobiology of autism spectrum disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 29, 11–19.

Posthuma, D., Luciano, M., Geus, E. J., Wright, M. J., Slagboom, P. E., Montgomery, G. W., et al. (2005). A genomewide scan for intelligence identifies quantitative trait loci on 2q and 6p. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 318–326. doi: 10.1086/432647

Quesnel-Vallieres, M., Weatheritt, R. J., Cordes, S. P., and Blencowe, B. J. (2019). Autism spectrum disorder: insights into convergent mechanisms from transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 51–63. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0066-2

Rice, C. E., Rosanoff, M., Dawson, G., Durkin, M. S., Croen, L. A., Singer, A., et al. (2012). Evaluating changes in the prevalence of the Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs). Public Health Rev. 34, 1–22.

Salek Esfahani, B., Gharesouran, J., Ghafouri-Fard, S., Talebian, S., Arsang-Jang, S., Omrani, M. D., et al. (2019). Down-regulation of ERMN expression in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Metab. Brain Dis. 34, 1261–1266. doi: 10.1007/s11011-019-00429-w

Van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P. J., van Eeten, E., Groen, W. B., Van Deurzen, P. A., Oosterling, I. J., and Van der Gaag, R. J. (2014). Gender and age differences in the core triad of impairments in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1913-9

Verma, R., Oania, R. S., Kolawa, N. J., and Deshaies, R. J. (2013). Cdc48/p97 promotes degradation of aberrant nascent polypeptides bound to the ribosome. eLife 2:e00308.

Wang, S., Wang, T., Liu, T., Xie, R. G., Zhao, X. H., Wang, L., et al. (2020). Ermin is a p116(RIP) -interacting protein promoting oligodendroglial differentiation and myelin maintenance. Glia 68, 2264–2276.

Wang, T., Jia, L., Lv, B., Liu, B., Wang, W., Wang, F., et al. (2011). Human Ermin (hErmin), a new oligodendrocyte-specific cytoskeletal protein related to epileptic seizure. Brain Res. 1367, 77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.003

Werling, D. M., and Geschwind, D. H. (2013). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders Curr. Opin. Neurol. 26, 146–153.

Zhou, J., Zhang, X., Ren, J., Wang, P., Zhang, J., Wei, Z., et al. (2016). Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in valproic acid rat models of autism. Mol. Biol. Rep. 43, 837–847. doi: 10.1007/s11033-016-4015-x

Keywords: autism spectrum disorders, ERMN, LTN1, expression, biomarker

Citation: Shiva S, Gharesouran J, Sabaie H, Asadi MR, Arsang-Jang S, Taheri M and Rezazadeh M (2021) Expression Analysis of Ermin and Listerin E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 1 Genes in Autistic Patients. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14:701977. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.701977

Received: 28 April 2021; Accepted: 28 June 2021;

Published: 19 July 2021.

Edited by:

Mukesh K. Pandey, Mayo Clinic, United StatesReviewed by:

Salvatore Chirumbolo, University of Verona, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Shiva, Gharesouran, Sabaie, Asadi, Arsang-Jang, Taheri and Rezazadeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Taheri, TW9oYW1tYWRfODIzQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==; Maryam Rezazadeh, UmV6YXphZGVobUB0YnptZWQuYWMuaXI=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.