94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Mol. Neurosci., 19 September 2019

Sec. Methods and Model Organisms

Volume 12 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00228

Chunmei Jin1,2†

Chunmei Jin1,2† Hyae Rim Kang1,2†

Hyae Rim Kang1,2† Hyojin Kang3†

Hyojin Kang3† Yinhua Zhang1,2

Yinhua Zhang1,2 Yeunkum Lee1,2

Yeunkum Lee1,2 Yoonhee Kim1,2

Yoonhee Kim1,2 Kihoon Han1,2*

Kihoon Han1,2*Genetic variants of the SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (SHANK3) gene, which encodes excitatory postsynaptic core scaffolds cause numerous brain disorders. Several lines of Shank3 knock-out (KO) mice with deletions of different Shank3 exons have previously been generated and characterized. The different Shank3 KO mouse lines have both common and line-specific phenotypes. Shank3 isoform diversity is considered a mechanism underlying phenotypic heterogeneity, and compensatory changes through regulation of Shank3 expression may contribute to this heterogeneity. However, whether such compensatory changes occur in Shank3 KO mouse lines has not been investigated in detail. Using previously reported RNA-sequencing analyses, we identified an unexpected increase in Shank3 transcripts in two different Shank3 mutant mouse lines (Shank3B and Shank3ΔC) having partial deletions of Shank3 exons. We validated an increase in Shank3 transcripts in the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum, but not in the cerebellum, of Shank3B heterozygous (HET) and KO mice, using qRT-PCR analyses. In particular, expression of the N-terminal exons 1–12, but not the more C-terminal exons 19–22, was observed to increase in Shank3B mice with deletion of exons 13–16. This suggests a selective compensatory activation of upstream Shank3 promoters. Furthermore, using domain-specific Shank3 antibodies, we confirmed that the increased Shank3 transcripts in Shank3B KO mice produced a small Shank3 isoform that was not detected in wild-type mice. Taken together, our results illustrate another layer of complexity in the regulation of Shank3 expression in the brain, which may also contribute to the phenotypic heterogeneity of different Shank3 KO mouse lines.

Deletions, duplications, and various point mutations of the SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (SHANK3) gene that encodes neuronal excitatory postsynaptic core scaffolds are causally associated with numerous brain disorders, including autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, intellectual disability, and schizophrenia (Grabrucker et al., 2011; Monteiro and Feng, 2017). Previously, several Shank3 mutant mouse models (i.e., knock-out (KO), knock-in, viral-mediated knock-down, and overexpression) mimicking conditions in patients, were generated and their neurobehavioral phenotypes were characterized in detail (Jiang and Ehlers, 2013; Monteiro and Feng, 2017). Specifically, more than ten different lines of Shank3 KO mice having deletions of different Shank3 exons were generated and mutant phenotypes both common and specific to certain lines were identified (Monteiro and Feng, 2017). The mouse Shank3 gene has 22 exons and expresses several protein isoforms as a result of processing multiple intragenic promoters and alternative splicing (Wang et al., 2014; Figure 1A). Therefore, different subsets of Shank3 isoforms are disrupted in different Shank3 KO mouse lines having partial deletions of exons, which can contribute to the phenotypic heterogeneity among the KO mouse lines.

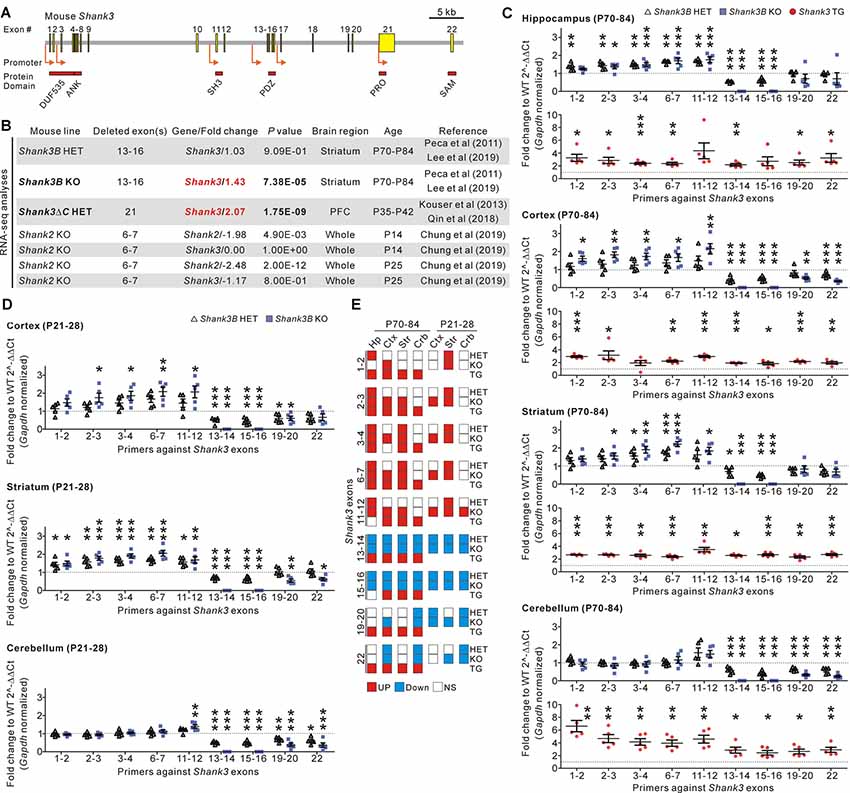

Figure 1. Identification and validation of increased Shank3 transcript abundance in the brain regions of Shank3 mutant mice with partial exon deletions. (A) Schematic diagram showing the structure of the mouse Shank3 gene. The locations of the intragenic promoters and protein domains below their respective encoding exons are indicated. ANK, ankyrin repeat domain; DUF535, protein domain of unknown function 535; PDZ, postsynaptic density 95/discs large/zonula occludens 1 domain; PRO, proline-rich region; SAM; sterile alpha motif; SH3, SRC homology 3 domain. (B) Summary of changes in the Shank3 and Shank2 transcript levels obtained from the previously reported RNA-sequencing analyses of different Shank3 and Shank2 mutant mouse lines. P, postnatal day; PFC, prefrontal cortex. (C) qRT-PCR validation of Shank3 transcript levels in the four brain regions of adult Shank3B heterozygous (HET) and knock-out (KO), and Shank3 TG mice compared to their respective WT littermates (n = 5 animals per genotype). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of Shank3 transcript levels in the cortex, striatum, and cerebellum of juvenile Shank3B HET and KO mice compared to the WT littermates (n = 5 animals per genotype). (E) Summary of the qRT-PCR analyses. Crb, cerebellum; Ctx, cortex; Hp, hippocampus; NS, not significant; Str, striatum. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 [one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-test for WT, HET, and KO; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for WT and TG].

Because of its crucial roles in synaptic development and function, Shank3 gene expression, and Shank3 protein stability and interaction are tightly controlled by multiple mechanisms from the transcriptional to post-translational levels (Zhu et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2015; Kerrisk Campbell and Sheng, 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, in addition to isoform diversity, any compensatory changes in these Shank3 regulatory mechanisms may also contribute to variable phenotypes in different Shank3 KO mouse lines. However, whether such compensatory changes in regulation occur in any of the Shank3 KO mouse lines has not yet been investigated in detail.

In this study, we identified and validated an unexpected increase in Shank3 transcripts in the brain regions of Shank3B mice, in which exons 13–16 of the Shank3 gene are targeted. This increase occurred in both heterozygous (HET) and KO mice. The increase was mainly observed from the N-terminal (1–12) Shank3 exons in terms of the deleted exons in Shank3B mice, suggesting selective compensatory activation of upstream Shank3 promoters. Furthermore, we confirmed that the upregulated Shank3 transcripts produced a small Shank3 protein isoform in Shank3B KO brains. Our results reveal a novel compensatory change with respect to regulating Shank3 expression in the brain, which may also contribute to the phenotypic heterogeneity of different Shank3 KO mouse lines.

The enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-Shank3 transgenic (TG), and Shank3B HET and KO mice used in this study have been described previously (Peca et al., 2011; Han et al., 2013b; Lee et al., 2017a; Lee B. et al., 2017). The mice were bred and maintained in a C57BL/6J (Japan SLC, Inc.) background according to the Korea University College of Medicine Research Requirements, and all the experimental procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Research at the Korea University College of Medicine (KOREA-2016-0096). The mice were had access to water and food ad libitum and were housed at 4–6 mice per cage under a 12-h light-dark cycle at 18–25°C. For all experiments, only male mice were used, and WT control refers to the WT littermates of the TG or HET and KO mice.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as described previously (Kim et al., 2016; Lee B. et al., 2017; Jin et al., 2018b). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from the brain regions of WT and Shank3 TG as well as WT, Shank3B HET, and KO mice using an miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, #217004) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1.5 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using an iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, #170-8891). Target mRNAs were detected and quantified by a real-time PCR instrument (CFX96 Touch, Bio-Rad) using SYBR Green master mix (Bio-Rad, #170-8884AP). The results were analyzed using the comparative Ct method normalized against the housekeeping gene Gapdh (Han et al., 2013a). The primer sequences for real-time PCR are as follows:

Mouse Shank3 (exons 1–2)

forward 5′ CGGACCTGCAACAAACGAAG 3′,

reverse 5′ TGTCCAGGTTAGGCGGGTAG 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 2–3)

forward 5′ TCTGCGCCCTCAATCATAGC 3′,

reverse 5′ AGCTTTGCAAACTGCTTGTCA 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 3–4)

forward 5′ GCGGAGAGTTTATGCCCAGA 3′,

reverse 5′ GGCCACCTTATCTGTGCTGT 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 6–7)

forward 5′ TGGTTGGCAAGAGATCCAT 3′,

reverse 5′ TTGGCCCCATAGAACAAAAG 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 11–12)

forward 5′ CAAGTTCATCGCTGTGAAGG 3′,

reverse 5′ TGTCGCATCTGCACTTCTTC 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 13–14)

forward 5′ TCTTCCGCCACTACACTGTG 3′,

reverse 5′ AAAGCCAAACCCCTCATGGT 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 15–16)

forward 5′ TTACACCCACACCTGCCTTC 3′,

reverse 5′ CACCATCCTCCTCGGGTTTC 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exons 19–20)

forward 5′ ACATTGCAGATGCTGACTCG 3′,

reverse 5′ CAGATTTGGTCCGTGGAATC 3′

Mouse Shank3 (exon 22)

forward 5′ AGTACCCCTTCGGGCTTCTA 3′,

reverse 5′ CAGACTCCAAACCCGATGTT 3′

Mouse Gapdh

forward 5′ GGCATTGCTCTCAATGACAA 3′,

reverse 5′ CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTAT 3′

Specificity of each primer set was confirmed by examining the melting peaks of qRT-PCR reactions and the band size of PCR products from the reactions (Supplementary Figure S1).

Whole lysate of the mouse brain tissue was prepared as previously described (Han et al., 2009, 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). Briefly, frozen mouse brain tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) with freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, #11836170001 and #4906837001, respectively). Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, #500-0006). The lysate was heated in 1X NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #NP0007) containing 1X NuPAGE reducing agent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #NP0004). From each sample, 20 μg of protein was loaded into 4%–15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX™ Precast Protein Gels (Bio-Rad, #4561084) for western blotting. The proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, #IPVH00010). The primary antibodies used for western blot analysis were Shank3 Ab#1 (aa 192–221) and Ab#2 (aa 529–558; kindly gifted by Prof. Eunjoon Kim, KAIST; Lee et al., 2015), Shank3 Ab#3 (aa 1431–1590, Santa Cruz, #sc-30193), and GAPDH (Cell Signaling, #2118S). Western blot images were acquired with the ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad) and quantified using ImageJ software.

In recent RNA-sequencing analyses of the striatum of adult Shank3B HET and KO mice (Lee et al., 2019), we had unexpectedly observed significantly increased total Shank3 transcripts in the KO striatum when compared to the WT striatum (Figure 1B). This raised our interest in the potential compensatory changes that occur in Shank3 KO mouse lines. To understand whether this increase in Shank3 transcripts was specific to the Shank3B KO line alone, we consulted another recently reported RNA-sequencing analysis (Qin et al., 2018) of the prefrontal cortex of Shank3ΔC HET mice in which exon 21 of the Shank3 gene was targeted (Kouser et al., 2013). We found that abundance of Shank3 transcripts was also significantly increased in this line (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, RNA-sequencing analyses for the whole brain of KO mice in which exons 6–7 of Shank2, another member of the Shank gene family, were targeted (Chung et al., 2019), showed a decrease in total Shank2 transcripts and normal Shank3 transcripts (Figure 1B), thus suggesting that an increase in Shank3 transcripts may be specific to Shank3 mutant mice with partial deletions of Shank3 exons.

To directly validate the changes in Shank3 transcripts in detail, we performed qRT-PCR analyses on four different brain regions (hippocampus, cortex, striatum, and cerebellum) from adult (postnatal day 70–84) Shank3B HET and KO mice, and their WT littermates. We used nine primer sets targeting different exons along the Shank3 gene (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we performed qRT-PCR experiments on the brain regions in adult Shank3-overexpressing TG mice and their WT littermates as a control (Han et al., 2013b; Lee et al., 2017b; Jin et al., 2018a,c). As expected, expression of exons 13–16 (i.e., the deleted exons) decreased by 50% and 100% in the four brain regions of Shank3B HET and KO mice, respectively (Figure 1C). Moreover, the C-terminal exons (exons 19–22) showed decreased expression in the cortex and cerebellum from Shank3B HET and KO mice when compared to WT mice. However, expression levels of the N-terminal exons (exons 1–12) were unexpectedly and significantly increased in the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum of Shank3B HET and KO mice (Figure 1C). These N-terminal exons were expressed at normal levels in the cerebellum of Shank3B HET and KO mice. In contrast, all the examined Shank3 exons were expressed at higher levels in the four brain regions of Shank3 TG mice compared to WT mice (Figure 1C). Increased expression of N-terminal Shank3 exons was also observed in the cortex and striatum, but not in the cerebellum (with the exception of exons 11–12), of juvenile (postnatal day 21–28) Shank3B HET and KO mice (Figure 1D). Figure 1E summarizes the qRT-PCR analyses.

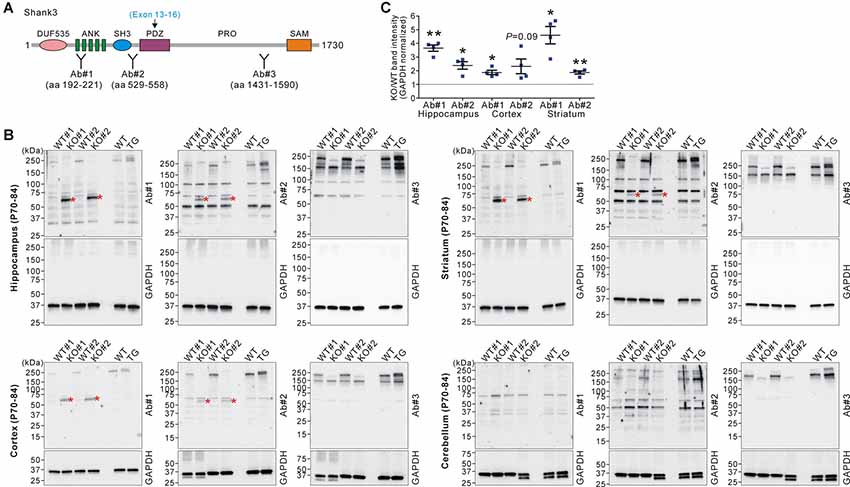

Next, we investigated whether the increased Shank3 transcripts in Shank3B KO mice were translated to produce Shank3 proteins. We performed western blot analyses on the brain lysates from WT, KO, and TG mice using three different domain-specific Shank3 antibodies (Lee et al., 2015; Figure 2A). Notably, antibodies against the N-terminal regions (Ab#1 and Ab#2), but not against the C-terminal region (Ab#3), of Shank3 detected a ~60 kDa protein band in the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum of Shank3B KO mice (Figures 2B,C). Importantly, the band was not detected in the WT and TG brains. The protein size approximately corresponded to the number of amino acids (~540 residues) encoded by exons 1–12 of the Shank3 gene. These results suggest that the ~60 kDa Shank3 protein detected in the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum of Shank3B KO mice was likely translated from the increased Shank3 exon 1–12 transcripts in the mice. Consistently with this interpretation, we did not detect the KO-specific ~60 kDa protein in the cerebellum (Figure 2B) where expression of the N-terminal Shank3 exons was normal in Shank3B KO mice (Figure 1C). Nevertheless, our western blot results should be considered cautiously and require further validation with additional, if available, Shank3 domain-specific antibodies because there were multiple faint bands detected by the antibodies.

Figure 2. Western blot validation of expression of a small Shank3 isoform in the brain regions of Shank3B KO mice. (A) Targeted Shank3 regions of the antibodies (Ab#1~3) are indicated. Ab, antibody. Note that the deleted exons (13–16) in Shank3B mutant mice encode the PDZ domain of Shank3. (B) Western blot detection of Shank3 proteins by domain-specific Shank3 antibodies from whole lysates of the hippocampus, cortex, striatum, and cerebellum of adult WT, Shank3B KO, and Shank3 TG mice. Note that a ~60 kDa band (asterisk) was detected in the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum of KO, but not WT and TG, mice by N-terminal antibodies #1 and #2. Also note that, in the cerebellum, there is no such KO-specific ~60 kDa band detected. (C) Quantification of fold-increases of the ~60 kDa band in the Shank3B KO brains compared to the WT brains (n = 4 animals per genotype). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

In this study, we observed an unexpected increase in Shank3 transcripts in the brain regions in Shank3 HET and KO mice having partial deletions of particular exons. The increase in Shank3 transcripts was unlikely to be a non-specific outcome of chromosomal changes in the Shank3 gene because it was observed in two different Shank3 mutant mouse lines (i.e., Shank3B and Shank3ΔC) with different Shank3 exonal deletions, and because it was not observed in the cerebellum of Shank3B mutant mice based on qRT-PCR. Moreover, the increase mainly occurred in the N-terminal but not C-terminal exons in Shank3B mutant mice, which suggests selective compensatory activation of upstream Shank3 promoters in the process. Even so, it is not immediately clear how loss of synaptic Shank3 leads to the activation of Shank3 promoters. One candidate player for this feedback mechanism is β-catenin, which, upon loss of synaptic Shank3, translocates from the synapse to the nucleus to induce histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2)-dependent transcriptional changes (Qin et al., 2018). Whether β-catenin directly binds to the upstream Shank3 promoters to induce their transcription remains to be validated.

Any functional effect of the increased Shank3 transcripts in Shank3 mutant mice also remains to be investigated. Our western blot analyses suggest that Shank3B KO mice produce a small Shank3 isoform, possibly having the N-terminal DUF535, ANK, and SH3 domains. This short isoform may function in a dominant-negative manner by sequestering some N-terminal Shank3 interactors, and thereby contributing to synaptic changes observed in the KO mice. Indeed, functional roles of the N-terminal part of Shank3 have been revealed by several studies (Hayashi et al., 2009; Cochoy et al., 2015; Lilja et al., 2017; Hassani Nia and Kreienkamp, 2018).

Regardless of the detailed underlying mechanisms and potential functional effects, our finding provides another layer of complexity with respect to regulating Shank3 expression in the brain. We suggest that this may also contribute to phenotypic heterogeneity between Shank3 mutant mouse lines with partial deletions of exons. For example, even with activation of the upstream Shank3 promoters, no or minimal Shank3 transcript increase may be observed in mutant mouse lines having deletions in the N-terminal Shank3 exons (Bozdagi et al., 2010; Peca et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). Meanwhile, the increased Shank3 transcripts in Shank3ΔC mice in which exon 21 of the Shank3 gene was targeted (Kouser et al., 2013), may produce longer Shank3 protein isoforms than the ~60 kDa isoform detected in Shank3B KO mice. Comprehensive qRT-PCR validation of exon-specific Shank3 transcripts and western blot analyses using domain-specific Shank3 antibodies in the brain regions of different Shank3 mutant mouse lines are necessary to confirm this intriguing hypothesis.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Committee on Animal Research at the Korea University College of Medicine (KOREA-2016-0096).

CJ, HRK, HK, YZ, YL, YK and KH designed and performed the experiments. HK and KH analyzed and interpreted the data. KH wrote the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea Government Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2015M3C7A1028790, NRF-2018R1C1B6001235, NRF-2018M3C7A1024603, and NRF-2018R1A6A3A11040508), and by the Korea University Grant.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00228/full#supplementary-material

Bozdagi, O., Sakurai, T., Papapetrou, D., Wang, X., Dickstein, D. L., Takahashi, N., et al. (2010). Haploinsufficiency of the autism-associated Shank3 gene leads to deficits in synaptic function, social interaction, and social communication. Mol. Autism 1:15. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-15

Choi, S. Y., Pang, K., Kim, J. Y., Ryu, J. R., Kang, H., Liu, Z., et al. (2015). Post-transcriptional regulation of SHANK3 expression by microRNAs related to multiple neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol. Brain 8:74. doi: 10.1186/s13041-015-0165-3

Chung, C., Ha, S., Kang, H., Lee, J., Um, S. M., Yan, H., et al. (2019). Early correction of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function improves autistic-like social behaviors in adult Shank2−/− mice. Biol. Psychiatry 85, 534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.025

Cochoy, D. M., Kolevzon, A., Kajiwara, Y., Schoen, M., Pascual-Lucas, M., Lurie, S., et al. (2015). Phenotypic and functional analysis of SHANK3 stop mutations identified in individuals with ASD and/or ID. Mol. Autism 6:23. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0020-5

Grabrucker, A. M., Schmeisser, M. J., Schoen, M., and Boeckers, T. M. (2011). Postsynaptic ProSAP/Shank scaffolds in the cross-hair of synaptopathies. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.07.003

Han, K., Chen, H., Gennarino, V. A., Richman, R., Lu, H. C., and Zoghbi, H. Y. (2015). Fragile X-like behaviors and abnormal cortical dendritic spines in Cytoplasmic FMR1-interacting protein 2-mutant mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 1813–1823. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu595

Han, K., Gennarino, V. A., Lee, Y., Pang, K., Hashimoto-Torii, K., Choufani, S., et al. (2013a). Human-specific regulation of MeCP2 levels in fetal brains by microRNA miR-483–5p. Genes Dev. 27, 485–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.207456.112

Han, K., Holder, J. L. Jr., Schaaf, C. P., Lu, H., Chen, H., Kang, H., et al. (2013b). SHANK3 overexpression causes manic-like behaviour with unique pharmacogenetic properties. Nature 503, 72–77. doi: 10.1038/nature12630

Han, K., Kim, M. H., Seeburg, D., Seo, J., Verpelli, C., Han, S., et al. (2009). Regulated RalBP1 binding to RalA and PSD-95 controls AMPA receptor endocytosis and LTD. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000187

Hassani Nia, F., and Kreienkamp, H. J. (2018). Functional relevance of missense mutations affecting the N-terminal part of Shank3 found in autistic patients. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:268. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00268

Hayashi, M. K., Tang, C., Verpelli, C., Narayanan, R., Stearns, M. H., Xu, R. M., et al. (2009). The postsynaptic density proteins Homer and Shank form a polymeric network structure. Cell 137, 159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.050

Jiang, Y. H., and Ehlers, M. D. (2013). Modeling autism by SHANK gene mutations in mice. Neuron 78, 8–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.016

Jin, C., Kang, H., Kim, S., Zhang, Y., Lee, Y., Kim, Y., et al. (2018a). Transcriptome analysis of Shank3-overexpressing mice reveals unique molecular changes in the hypothalamus. Mol. Brain 11:71. doi: 10.1186/s13041-018-0413-4

Jin, C., Kang, H., Ryu, J. R., Kim, S., Zhang, Y., Lee, Y., et al. (2018b). Integrative brain transcriptome analysis reveals region-specific and broad molecular changes in Shank3-overexpressing mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:250. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00250

Jin, C., Zhang, Y., Kim, S., Kim, Y., Lee, Y., and Han, K. (2018c). Spontaneous seizure and partial lethality of juvenile Shank3-overexpressing mice in C57BL/6 J background. Mol. Brain 11:57. doi: 10.1186/s13041-018-0403-6

Kerrisk Campbell, M., and Sheng, M. (2018). USP8 deubiquitinates SHANK3 to control synapse density and SHANK3 activity-dependent protein levels. J. Neurosci. 38, 5289–5301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3305-17.2018

Kim, Y., Zhang, Y., Pang, K., Kang, H., Park, H., Lee, Y., et al. (2016). Bipolar disorder associated microRNA, miR-1908–5p, regulates the expression of genes functioning in neuronal glutamatergic synapses. Exp. Neurobiol. 25, 296–306. doi: 10.5607/en.2016.25.6.296

Kouser, M., Speed, H. E., Dewey, C. M., Reimers, J. M., Widman, A. J., Gupta, N., et al. (2013). Loss of predominant Shank3 isoforms results in hippocampus-dependent impairments in behavior and synaptic transmission. J. Neurosci. 33, 18448–18468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3017-13.2013

Lee, J., Chung, C., Ha, S., Lee, D., Kim, D. Y., Kim, H., et al. (2015). Shank3-mutant mice lacking exon 9 show altered excitation/inhibition balance, enhanced rearing, and spatial memory deficit. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:94. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00094

Lee, Y., Kang, H., Jin, C., Zhang, Y., Kim, Y., and Han, K. (2019). Transcriptome analyses suggest minimal effects of Shank3 dosage on directional gene expression changes in the mouse striatum. Anim. Cells Syst. 23, 270–274. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2019.1595142

Lee, Y., Kang, H., Lee, B., Zhang, Y., Kim, Y., Kim, S., et al. (2017a). Integrative analysis of brain region-specific Shank3 interactomes for understanding the heterogeneity of neuronal pathophysiology related to SHANK3 mutations. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10:110. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00110

Lee, Y., Kim, S. G., Lee, B., Zhang, Y., Kim, Y., Kim, S., et al. (2017b). Striatal transcriptome and interactome analysis of Shank3-overexpressing mice reveals the connectivity between Shank3 and mTORC1 signaling. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10:201. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00201

Lee, B., Zhang, Y., Kim, Y., Kim, S., Lee, Y., and Han, K. (2017). Age-dependent decrease of GAD65/67 mRNAs but normal densities of GABAergic interneurons in the brain regions of Shank3-overexpressing manic mouse model. Neurosci. Lett. 649, 48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.016

Lilja, J., Zacharchenko, T., Georgiadou, M., Jacquemet, G., De Franceschi, N., Peuhu, E., et al. (2017). SHANK proteins limit integrin activation by directly interacting with Rap1 and R-Ras. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 292–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb3487

Monteiro, P., and Feng, G. (2017). SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 147–157. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.183

Peca, J., Feliciano, C., Ting, J. T., Wang, W., Wells, M. F., Venkatraman, T. N., et al. (2011). Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature 472, 437–442. doi: 10.1038/nature09965

Qin, L., Ma, K., Wang, Z. J., Hu, Z., Matas, E., Wei, J., et al. (2018). Social deficits in Shank3-deficient mouse models of autism are rescued by histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 564–575. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0110-8

Wang, X., McCoy, P. A., Rodriguiz, R. M., Pan, Y., Je, H. S., Roberts, A. C., et al. (2011). Synaptic dysfunction and abnormal behaviors in mice lacking major isoforms of Shank3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3093–3108. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr212

Wang, L., Pang, K., Han, K., Adamski, C. J., Wang, W., He, L., et al. (2019). An autism-linked missense mutation in SHANK3 reveals the modularity of Shank3 function. Mol. Psychiatry doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0324-x [Epub ahead of print].

Wang, X., Xu, Q., Bey, A. L., Lee, Y., and Jiang, Y. H. (2014). Transcriptional and functional complexity of Shank3 provides a molecular framework to understand the phenotypic heterogeneity of SHANK3 causing autism and Shank3 mutant mice. Mol. Autism 5:30. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-30

Zhang, Y., Kang, H., Lee, Y., Kim, Y., Lee, B., Kim, J. Y., et al. (2018). Smaller body size, early postnatal lethality, and cortical extracellular matrix-related gene expression changes of Cyfip2-null embryonic mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:482. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00482

Keywords: Shank3, knock-out mice, transcripts, compensation, exon

Citation: Jin C, Kang HR, Kang H, Zhang Y, Lee Y, Kim Y and Han K (2019) Unexpected Compensatory Increase in Shank3 Transcripts in Shank3 Knock-Out Mice Having Partial Deletions of Exons. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12:228. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00228

Received: 01 July 2019; Accepted: 04 September 2019;

Published: 19 September 2019.

Edited by:

Carlo Sala, Institute of Neuroscience (CNR), ItalyReviewed by:

Andreas Martin Grabrucker, University of Limerick, IrelandCopyright © 2019 Jin, Kang, Kang, Zhang, Lee, Kim and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kihoon Han, bmV1cm9oYW5Aa29yZWEuYWMua3I=

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.