Corrigendum: YAP and TAZ Regulate Cc2d1b and Purβ in Schwann Cells

- 1Department of Neuroscience and Experimental Therapeutics, Albany Medical College, Albany, NY, United States

- 2Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 3Department of Biochemistry, Hunter James Kelly Research Institute, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States

- 4Department of Neurology, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States

Schwann cells (SCs) are exquisitely sensitive to the elasticity of their environment and their differentiation and capacity to myelinate depend on the transduction of mechanical stimuli by YAP and TAZ. YAP/TAZ, in concert with other transcription factors, regulate several pathways including lipid and sterol biosynthesis as well as extracellular matrix receptor expressions such as integrins and G-proteins. Yet, the characterization of the signaling downstream YAP/TAZ in SCs is incomplete. Myelin sheath production by SC coincides with rapid up-regulation of numerous transcription factors. Here, we show that ablation of YAP/TAZ alters the expression of transcription regulators known to regulate SC myelin gene transcription and differentiation. Furthermore, we link YAP/TAZ to two DNA binding proteins, Cc2d1b and Purβ, which have no described roles in myelinating glial cells. We demonstrate that silencing of either Cc2d1b or Purβ limits the formation of myelin segments. These data provide a deeper insight into the myelin gene transcriptional network and the role of YAP/TAZ in myelinating glial cells.

MAIN POINTS

YAP and TAZ regulate positive and negative myelin regulators.

Cc2d1b and Purβ are necessary for Schwann cell myelination in vitro.

Introduction

The function of the nervous system relies on the ability of peripheral nerve fibers to transmit information to and from the target tissues. The speed of propagation of action potentials in these fibers is regulated by myelin, a multilamellar structure produced by Schwann cells (SCs; Monk et al., 2015). Damage to SC or peripheral myelin can be caused by numerous factors, including genetic mutations, toxic agents, inflammation, viral infections, metabolic alterations, hypoxia or physical trauma and results in severe peripheral neuropathies. SC integrate biochemical signaling pathways and mechanical stimuli coming from the extracellular matrix or from the axon (Michailov et al., 2004; Feltri and Wrabetz, 2005; Taveggia et al., 2005; Belin et al., 2017). These signals regulate an intricate network of transcription factors that control differentiation of SCs and myelination (e.g., EGR2, YY1, ZEB2, Topilko et al., 1994; Nagarajan et al., 2001; He et al., 2010; Weng et al., 2012; Quintes et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016). The identification and characterization of the complete repertoire of transcription factors that modulate myelination is still incomplete (Svaren and Meijer, 2008; Fulton et al., 2011).

The identification of transcription factors responding to a specific signal is one of the first steps in dissecting the underlying regulatory networks. We showed that in Yap fl/+; Taz fl/fl; Mpz-Cre (Yap cHet; Taz cKO) sciatic nerves, SCs lacking YAP/TAZ are unable to myelinate and experience a global dysregulation of transcription (Poitelon et al., 2016). YAP/TAZ are two transcriptional activators of the HIPPO pathway, and play important roles in controlling organ growth, cell differentiation, proliferation and survival (Dupont, 2016). Mechanical stimulation can regulate YAP/TAZ through signals involving FAK, Src, PI3K and JNK pathways (Codelia et al., 2014; Mohseni et al., 2014; Kim and Gumbiner, 2015; Elbediwy et al., 2016), or the formation of actomyosin filaments and accumulation of F-actin (Dupont et al., 2011; Aragona et al., 2013). In addition, YAP/TAZ in SCs can be activated through Crb/Amolt proteins and laminin/G-protein signaling (Colciago et al., 2015; Fernando et al., 2016; Poitelon et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2017). YAP/TAZ regulate gene expression by binding to other DNA-binding transcription factors, especially TEAD transcription factors, but also p73, ERBB4, EGR-1 SMADs RUNXs and TBX5 (Kim et al., 2018). TEADs role in myelination is unknown (Hung et al., 2015; Lopez-Anido et al., 2015), but TEAD1 binding to transcriptional enhancers is induced during myelination (Lopez-Anido et al., 2016). Furthermore, genes encoding for essential myelin proteins (i.e., Mpz, Pmp22, Mbp and Mag) harbor TEAD elements and are downregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves (Poitelon et al., 2016). Finally, it was suggested that YAP/TAZ and TEAD1 regulate myelin wrapping in cooperation with master myelin regulators EGR2 and SOX10 (Lopez-Anido et al., 2016; Poitelon et al., 2016).

To identify novel regulators that are essential for myelination, we integrated RNA-seq and bioinformatics analyses and looked for DNA binding proteins dysregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves at 3 days of age. We identified two highly expressed proteins, i.e., Cc2d1b and Purβ, downregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves. We found that silencing of Cc2d1b or Purβ in vitro significantly decreased the number of myelin segments and silencing of Purβ also significantly decreased the length of myelin segments, independently for effect on SC number, proliferation or apoptosis. These data demonstrate that CC2D1B and PURβ are necessary for myelination in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Primary rat SCs were produced as described (Poitelon and Feltri, 2018) and grown with DMEM supplemented with 4 g/l glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5% bovine growth serum, 2 μM forskolin, 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor, penicillin and streptomycin. SCs were not used beyond the fourth passage. Rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons from Sprague–Dawley rats embryos were isolated at embryonic day 14.5 embryos. DRG were dissociated by treatment with 0.25% trypsin and mechanical trituration and 1.5 DRGs were seeded on collagen-coated glass coverslips as described (Poitelon and Feltri, 2018). DRGs cultures were then cycled with fluoroxidine (FUDR, Sigma-Aldrich) to eliminate all non-neuronal cells. Once all non-neuronal cell remove, rat SCs were added (200,000 cells per coverslip) to establish myelinating cocultures of DRG neurons, and myelination was initiated by supplementing the medium with 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). For verteporfin (Sigma SML0534) treatment, verteporfin was solubilized in DMSO at 20 mM, then SCs were treated with either 0.5% of DMSO; 2 or 10 μM of verteporfin for 24 h. mRNA was extracted and cDNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR, as described in Poitelon et al. (2016). This study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Basel Declaration and recommendations of ARRIVE guidelines issued by the NC3Rs and approved by the Albany Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (no. 17-08002).

shRNA Lentivirus Production and Infection

shRNA virions were produced as Poitelon et al. (2015). shRNA targeting Cc2d1b (#1, TTGCGCTCATCCCCACTGG), (#2, ATGAGCTCGAATAGCATCC) and Purβ (#1, AACTCGATGAGGCCCTGCG), (#2, TGGCATTGCGGTAGGATGG) and control (non-targeting) were bought from Dharmacon SMARTvector library. SCs were infected with five virions per cells, incubated for 72 h and collected for qRT-PCR analysis. Coculture experiments were done with shCc2d1b #1 and shPurβ #2.

RNA Preparation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Sciatic nerves were dissected, stripped of epineurium, frozen in liquid nitrogen, pulverized and processed as described (Poitelon et al., 2012). Total RNA was prepared from sciatic nerve or SCs with TRIzol (Roche Diagnostic). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For each reaction, 5 μM of oligo(dT)20 and 5 ng/μl random hexamers were used. Quantitative PCR was performed using the 20 ng of cDNA combined with 1× FastStart Universal Probe Master (Roche Diagnostic). Data were analyzed using the threshold cycle (Ct) and 2(−ΔΔCt) method. Actb was used as endogenous gene of reference and 18S was used as to validate the stable expression of Actb. The primers and probe used are the following: 18S (F: ctcaacacgggaaacctcac, R: cgctccaccaactaagaacg, probe #77), mouse Actb (F: aaggccaaccgtgaaaagat, R: gtggtacgaccagaggcatac, probe #56), mouse Cc2d1b (F: cactcacaggggaaacagc, R: ctgctgccagcttctcaat, probe #4); mouse Purβ (F: aattatggctaattcggctgtt, R: tttgcagatagtcaagttttaaggttt, probe #71); rat Cc2d1b (F: gcactcactggggaaacag, R: ctgccaacttctcaatgtgg, probe #4); rat Purβ (F: aaggaactgccagcaacct, R: agactcttgcgcaggtgag, probe #56).

Immunofluorescence and Immunoblotting

Immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting were performed as described (Della-Flora Nunes et al., 2017). Ten microgram of protein was used for western blot. The antibodies used are the following: anti-CC2D1A (Abcam, ab68302), anti-CC2D1B (Proteintech, 20774-1-AP), anti-PURα (Proteintech, 17733-1-AP), anti-PURβ (Proteintech, 18128-1-AP), anti-calnexin (Sigma, C4731), anti-phospho-histone H3 (Millipore, 06-576), anti-neurofilament H (Biolegend, 822701), anti-MBP (Biolegend, 808401). CC2D1B antibody was validated using Cc2d1b knockout mouse (Zamarbide et al., 2018). PURβ antibody was validated using purified PURβ fusion protein (Proteintech, Ag12705). Briefly, 1.5 μg of PURβ antibody was incubated with 50 μg of Purβ protein for 1 h at 37°C prior to being used for immunohistochemistry. TUNEL assays were performed on coverslips of culture as described in Poitelon et al. (2016). Myelination in vitro was evaluated from three different experiments, performed with two coverslips in each case, which is a standard sample size for these experiments. Images were acquired with identical acquisition parameters on an epi fluorescent Axio Imager A2 (Zeiss). Myelin segments number and length were quantified using ImageJ software1 from two random fields of each culture at the 10× objective, as described in Ghidinelli et al. (2017).

Bioinformatics

RNAseq data were obtained from NCBI GEO: GSE79115 (Poitelon et al., 2016). Genes encoding for DNA-binding protein genes were predicted thanks to transcriptionfactor.org database. The expression data for Cc2d1b and Purβ were obtained from mousebrain.org/ and gtexportal.org on 09/2018.

Statistical Analyses

Experiments were not randomized, but data collection and analysis were performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Data excluded are reported in the legend of the figures. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or SD. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those generally employed in the field. Two-tailed Student’s t-test, One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Two-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis of the differences between multiple groups according to the number of sample groups. Values of P ≤ 0.05 were considered to represent a significant difference.

Results

YAP and TAZ Regulate DNA-Binding Proteins in Schwann Cells

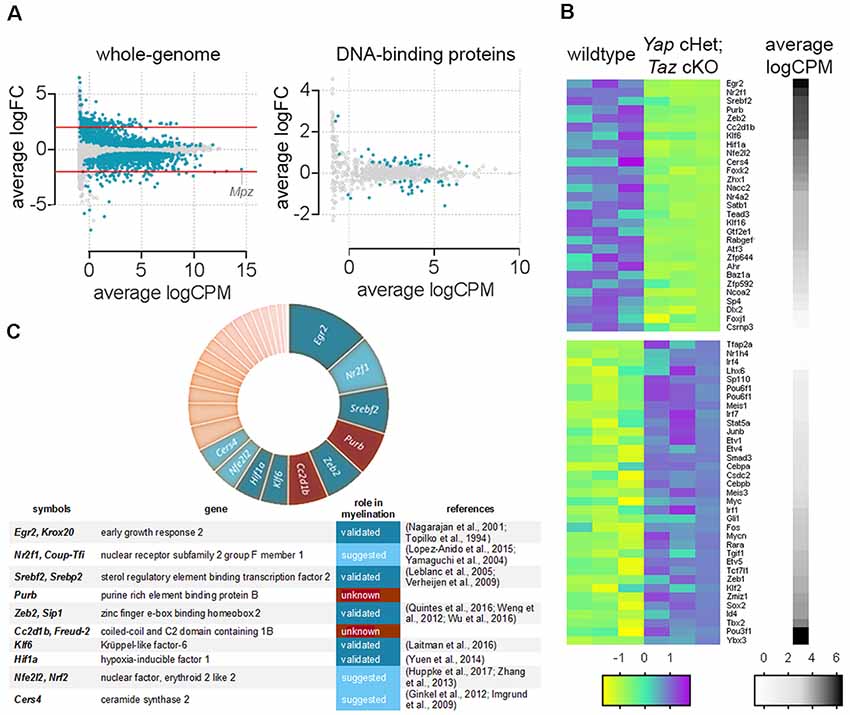

To examine the function of YAP and TAZ at the whole-genome level we analyzed RNA-seq transcriptome profiling of Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves at 3 days of age (NCBI GEO: GSE79115). We identified 2,071 misregulated transcripts (Figure 1, Poitelon et al., 2016). We narrowed our analysis to DNA-binding proteins and identified that ablation of Yap/Taz dysregulated 64 genes (Figure 1B). Genes encoding for DNA-binding proteins were then categorized according to their level of expression (Figure 1B, black/white heatmap). Signature genes normally expressed in neural crest cells (Tbx2) and immature SCs (Oct6/Pou3f1/Scip), as well as genes inhibiting differentiation (Id4) and myelin formation (Sox2) were highly expressed (Figure 1B, black) and upregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves (Figure 1B, magenta; Arroyo et al., 1998; Jang et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2017). Genes involved in myelination were highly expressed and downregulated (Figure 1C). Among the 10 most expressed DNA-binding proteins that were downregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves, eight were already shown or suggested to play a role in myelination: Egr2, Nr2f1, Srebf2, Zeb2, Klf6, Hif1a, Nfe2l2 and Cers4 (Figure 1C; Topilko et al., 1994; Nagarajan et al., 2001; Yamaguchi et al., 2004; Leblanc et al., 2005; Imgrund et al., 2009; Verheijen et al., 2009; Ginkel et al., 2012; Weng et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013; Yuen et al., 2014; Lopez-Anido et al., 2015; Laitman et al., 2016; Quintes et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Huppke et al., 2017). Excitingly, the remaining two DNA-binding proteins Cc2d1b and Purβ, have no known roles in peripheral nervous system development or myelination.

Figure 1. Genes encoding DNA-binding proteins significantly repressed in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves at 3 days of age. (A) Scatter plot for the comparison between genes differentially expressed in the wildtype and Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves at 3 days of age. Log2 fold-change in Yap cHet; Taz cKO; vs. control mice was plotted against the average count size (log-counts-per-million) for every gene. Blue dots indicate statistically different genes (False Discovery Rate ≤0.05). The x-axis (logCPM, log counts per million) is a measure of gene expression, with higher numbers indicating genes highly expressed in sciatic nerves (e.g., Mpz). The y-axis (logFC, log base 2-fold change) indicates if ablation of Yap/Taz upregulate or downregulate gene expression. Genes with positive values on the y-axis are positively regulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves when compared to control, while those with negative values on the y-axis are negatively regulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves. Red lines indicate a 2-fold difference. On the left, expression levels of all genes expressed in sciatic nerves are represented (whole-genome). Among these, 2,071 out of 18,016 genes are dysregulated (Poitelon et al., 2016). On the right, genes encoding for a DNA-binding protein were selected for the presence of a DNA binding domain (http://www.transcriptionfactor.org) expression levels of all DNA-binding proteins expressed in sciatic nerves are represented. Among these, 64 out of 1,445 are dysregulated. Average logCPM were calculated as log2 (average CPM + 0.5). (B) Heatmap for the significantly dysregulated DNA-binding proteins in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves at 3 days of age. The differential expression of genes encoding for a DNA binding domain protein was tested in wildtype and Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves. Of the 1,445 genes tested, 64 showed statistical significance. Colors in this heatmap correspond to expression levels in Yap cHet; Taz cKO vs. control sciatic nerves, on a scale of yellow for lowest values to magenta for highest values with cyan for moderate values. Genes are categorized based on their expression levels in wildtype sciatic nerves (black denotes high expression levels, whereas white depicts low expression levels). Heatmap data are calculated using Z-score, where z = x-mean in the samples/standard deviation in the samples. (C) The chart categorized DNA-binding proteins repressed Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves according to their expression levels in wildtype sciatic nerves (segment width indicates expression level). Among the 10 most expressed DNA-binding proteins (Egr2, Nr2f1, Srebf2, Purβ, Zeb2, Cc2d1b, Klf6, Hif1a, Nfe2l2, Cers4), eight have a role to play in myelin formation (blue). The role of Purβ and Cc2d1b in myelination is unknown (brown).

Identification of Novel Myelin Regulators in Schwann Cells

Cc2d1b, also named Freud-2, encodes for Coiled-coil and c2 domain containing 1B protein and is highly expressed in peripheral nerves and myelinating oligodendrocytes2,3 (Zhang et al., 2014). Purβ encodes for the Purine Rich elem//ent binding protein B. Purβ binding elements have already been characterized in numerous genes, including Mbp and Plp1 (Tretiakova et al., 1999; Dobretsova et al., 2008), yet it is unclear if Purβ is necessary for their expression.

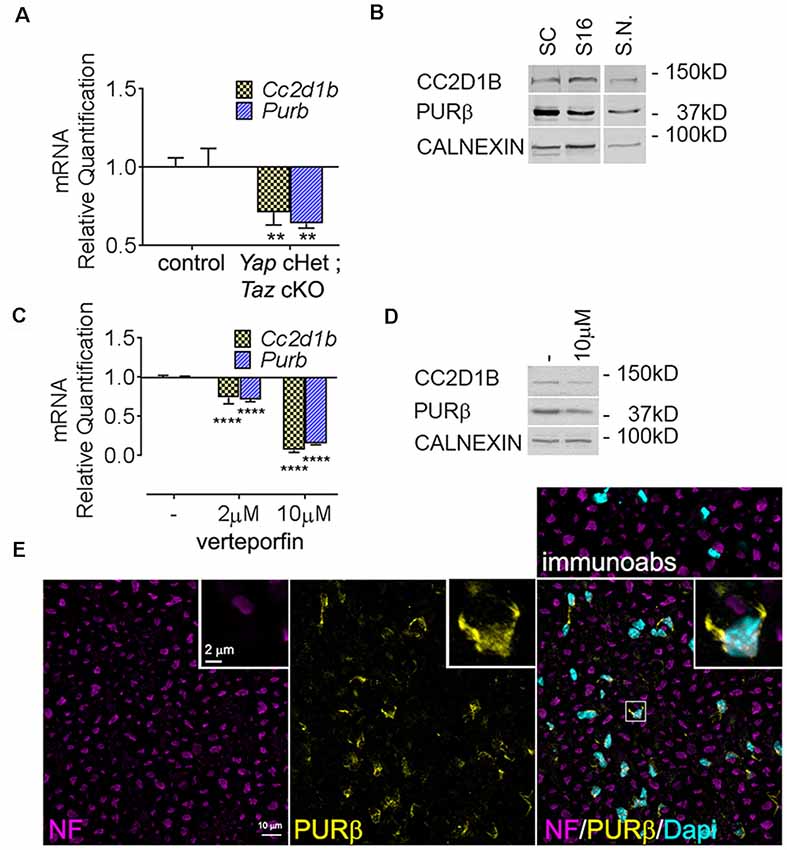

We first confirmed our RNAseq data by qRT-PCR and showed that Cc2d1b and Purβ are downregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves (Figure 2A). Because dysregulation of gene expression in sciatic nerves can be due to alterations of mRNA level in SCs, axons, perineurial or endothelial cells or fibroblasts, we confirmed that Cc2d1b and Purβ are expressed by primary SCs (Figures 2B,E). Finally, we showed that treatment of primary rat SCs with verteporfin, a drug that inhibits YAP/TAZ regulation of transcription by disrupting its interactions with TEAD transcription factors, reduces expression of Cc2d1b and Purβ (Figures 2C,D). Altogether, these data indicate that CC2D1B and PURβ are expressed by SCs and regulated by YAP/TAZ/TEAD.

Figure 2. Expression of Cc2d1b and Purβ in sciatic nerves and SCs. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed a transcriptional repression of Cc2d1b (−29%) and Purβ (−36%) in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves at P3. n = 3 animals per genotype. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test. F(1,8) = 49.64, P = 0.0001, Cc2d1b P = 0.0044, Purβ P = 0.0011. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Western blot analysis using the rabbit anti- CC2D1B and PURβ antibodies on wildtype rat SCs (lane 1), S16 SCs (lane 2) and wildtype mouse sciatic nerves (S.N.) at 30 days of age (lane 3). Calnexin was used as loading control. (C) mRNA and (D) protein levels of Cc2d1b and Purβ after verteporfin treatment (relative to DMSO-treated controls) in SCs. Cc2d1b (−93%) and Purβ (−85%) mRNA are strongly reduced upon a 24 h treatment with 10 μM of verteporfin. CC2D1B (−44%) and PURβ (−38%) protein levels are also reduced after a 24 h treatment with 10 μM of verteporfin. n = 3 independent experiments with three independent samples per group for (A,C). Error bars indicate SD. A logarithmic scale was used for the y-axis of (A,C), and the origin was set to 1. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. F(2,12) = 817.9, P < 0.0001, Cc2d1b P < 0.0001, Purβ P < 0.0001. (E) Immunolocalization of PURβ in cross section of sciatic nerve at P30 show localization of PURβ in SC cytoplasm and nuclei, although at P30 PURβ staining appears to be more intense in SC cytosol than in the nuclei. Scale bar = 10 μm. Insert display a magnified SCs stained for PURβ. Insert scale bar = 2 μm. Immunoabs displays a validation for PURβ antibody for which PURβ antibody was pre-absorbed with 30-fold excess of the PURβ protein before immunohistochemistry. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Cc2d1b and Purβ Regulate Myelination in vitro

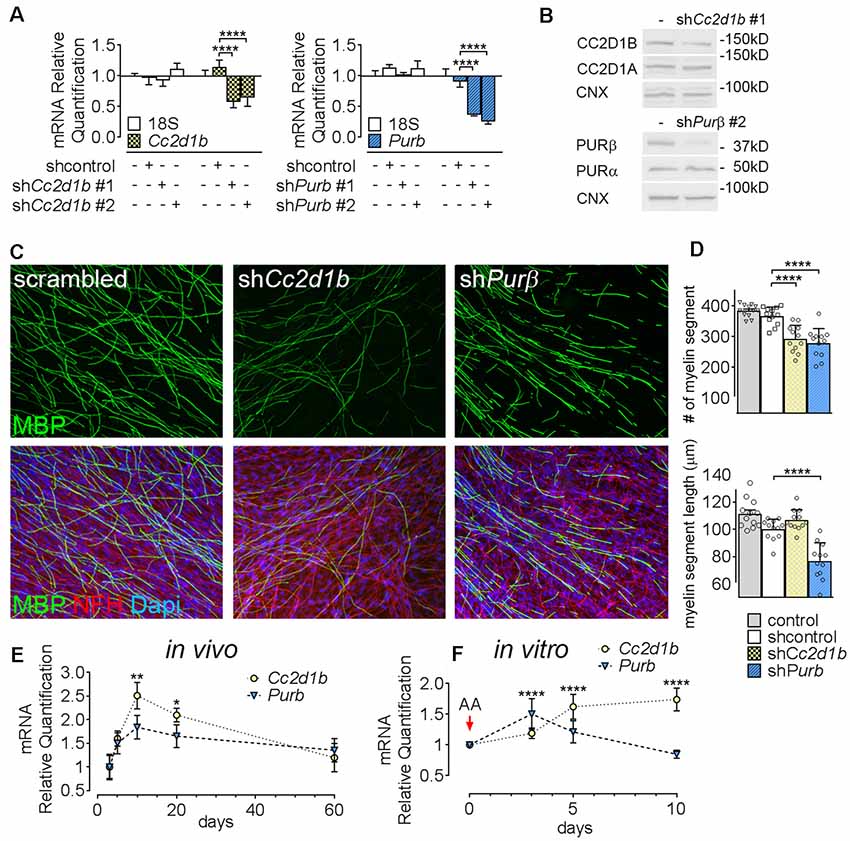

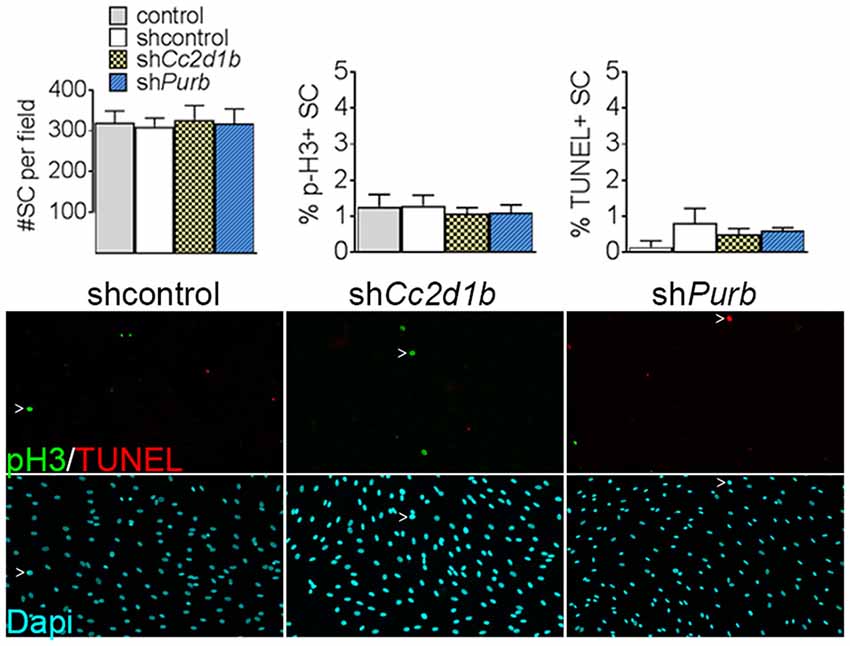

To determine the function of CC2D1B and PURβ in SCs, we asked if silencing the expression of Cc2d1b and Purβ in SCs would affect the capability of SC to myelinate axons. SCs were infected with viruses expressing different shRNAs for either Cc2d1b or Purβ. All shRNAs reduced expression of Cc2d1b or Purβ, as shown by quantitative RT-PCR and western blot (Figures 3A,B). In addition, we show that silencing Cc2d1b or Purβ does not affect the protein level of their homolog CC2D1A and PURα (Figure 3B). When SCs silenced for Cc2d1b and Purβ were seeded on DRG neurons and cocultured in myelinating conditions by adding ascorbic acid to the cultures, myelination of axons was impaired (Figures 3C,D). Because a defect of myelination can be caused by a reduced number of SCs attached to axons, we asked whether silencing Cc2d1b or Purβ caused changes in apoptosis or proliferation. However, silencing of Cc2d1b and Purβ did not affect SC proliferation or apoptosis (Figure 4). Finally, during in vivo and in vitro myelination, Mbp and Mpz gene expression peak 3 days after birth and 40 days after addition of ascorbic acid, respectively (Notterpek et al., 1999). We showed that Purβ expression was not significantly altered during SC development (Figure 3E) but appears, in vitro, to spike after 3 days in culture, before the start of myelination (Figure 3F). In contrast, Cc2d1b was highly expressed in vivo between postnatal day 5 (P5) and P20 (Figure 3E), and in vitro after 5 days in culture (Figure 3F), when SCs myelinate axons. Taken together, these data show that CC2D1B or PURβ is required for SC myelination in vitro.

Figure 3. Cc2d1b and Purβ regulate myelination in vitro. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed the silencing efficiency of shRNAs targeting Cc2d1b and Purβ in primary rat SCs. n = 3 experiments. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Cc2d1b F(3,16) = 10.83, P = 0.0004, shCc2d1b #1 (−43%) P < 0.0001 shCc2d1b #2 (−36%) P < 0.0001, Purβ F(3,16) = 35.09, P < 0.0001, shPurβ #1 (−64%) P < 0.0001, shPurβ #2 (−75%) P < 0.0001. Error bars indicate SD. A logarithmic scale was used for the y-axis and the origin was set to 1. (B) Western analysis showed that silencing Cc2d1b and Purβ reduce CC2D1B (−41%) and PURβ (−80%) protein levels, but do not after their respective homologs (CC2D1A and PURα). (C,D) Immunolocalization of myelin protein revealed a defect in myelin production in SCs silenced for either Cc2d1b or Purβ. SCs (200,000 cells) infected with shRNA were seeded on dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons and allowed to myelinate for 10 days. Cultures were stained for Myelin Basic Protein (MBP, green), neurofilament H (NFH, red) and DAPI (blue). The number and length of myelin segments were quantified. A lower number of segments were observed in both shCc2d1b and shPurβ and shortened myelin segments were observed in shPurβ. n = 4 coverslips for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. #myelin segments F(3,44) = 24.31, P < 0.0001, shCc2d1b P < 0.0001, shPurβ P < 0.0001. myelin segments length F(3,44) = 28.03, P < 0.0001, shPurβ P < 0.0001. Error bars indicate SD. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated a transient upregulation of Cc2d1b mRNA (dotted line, yellow circles) in sciatic nerves during in vivo myelination, from 10 to 20 days of age. Purβ expression (dashed line, blue triangles) also tend to be increased at 10 days of age. n = 3 animals. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. F(4,20) = 7.51, P = 0.0007, Cc2d1b 10 days P = 0.001, Cc2d1b 20 days P = 0.017, Purβ 10 days P = 0.09. Error bars indicate SEM. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated an upregulation of Cc2d1b (dotted line, yellow circles) in SC-neuron cocultures during in vitro myelination, from 5 days after addition of ascorbic acid (AA). Purβ (dashed line, blue triangles) is also transiently upregulated, 3 days after addition of AA. n = 6 coverslips. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. F(3,40) = 17.26, P < 0.0001, Cc2d1b 5 days P < 0.0001, Cc2d1b 10 days P < 0.0001, Purβ 3 days P < 0.0001, Purβ 5 days P = 0.05. Error bars indicate SD. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Figure 4. Cc2d1b and Purβ do not increase SC proliferation or apoptosis. Dapi (blue) staining on SC silenced for either Cc2d1b and Purβ show no differences in cell number. TUNEL analysis (red) and phospho-Histone 3 (p-H3—green) staining show no increase in proliferation or apoptosis. SCs were infected with five virions per cells, incubated for 72 h and stained. n = 4 independent experiment. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Error bars indicate SD.

Discussion

In this study, we identify novel regulators essential for myelination. Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves present an arrest SC early development and an abolition of subsequent SC myelination. We first hypothesized that genes regulated by YAP/TAZ include novel regulators of myelin formation. Thus, we analyzed gene expression by RNA-Seq analysis in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves. In contrast to classical analyses based on gene dysregulation, which would highlight genes highly regulated by YAP/TAZ (Poitelon et al., 2016), we used our dataset to look at DNA binding proteins highly expressed in Yap cHet; Taz cKO sciatic nerves, with the secondary assumption that their level of expression would be correlated to their importance in myelin formation. In this report, we validate our hypotheses and found that global gene expression stratification allows for the identification of genes essential for myelination. We were able to identify that most of the genes known to be either activators or inhibitors of myelination are highly expressed in sciatic nerves and are dysregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO. Following our reasoning, we identify two novel DNA binding proteins CC2D1B and PURβ, with previously unsuspected role in myelinating glial cells. CC2D1B and PURβ are highly expressed in sciatic nerves and in SCs and downregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO. We demonstrate that CC2D1B and PURβ are required for normal myelination. Ablation of either CC2D1B or PURβ impairs myelination in vitro, independently from effects on SC proliferation or apoptosis. Altogether our data demonstrate that CC2D1B and PURβ are both involved in myelin formation in vitro.

CC2D1B and PURβ are both DNA-binding proteins, but their role as a regulator in myelinating glial cells or other cells remains undefined. CC2D1B protein structure is close to its homolog CC2D1A.

Cc2d1a is highly expressed in neurons and has been implicated in intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder (Basel-Vanagaite et al., 2006; Manzini et al., 2014), Cc2d1b is expressed in myelinating glial cells and peripheral nerves4,5 (Zhang et al., 2014), which indicates that its role and function might not be fully redundant with Cc2d1a.

Few studies have suggested a redundant role between both proteins for the regulation of serotonin receptors (Hadjighassem et al., 2009, 2011). Yet, the transcriptional role of CC2D1 remains controversial, as other studies showed that both CC2D1 are confined to the cytoplasm and perinuclear endosomes (Drusenheimer et al., 2015). Thus, it remains unclear whether CC2D1B can directly control transcription in vivo and whether it translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Interestingly, other functions have been proposed for CC2D1 proteins independently from their DNA-binding domain. CC2D1 proteins belong to the evolutionary conserved Lgd protein family which was shown to be involved in the regulation of signaling receptor degradation via the endosomal pathway (Jaekel and Klein, 2006). Loss of Lgd function results in an ectopic and ligand-independent activation of the Notch pathway (Childress et al., 2006; Gallagher and Knoblich, 2006; Jaekel and Klein, 2006). Notch signaling promotes the early stage of SC development but inhibits myelination (Woodhoo et al., 2009). Thus, it is possible that CC2D1B modulates myelination through the recruitment of specific signaling complexes. Finally, Cc2d1b KO mice have been reported and present delayed memory acquisition and retention (Zamarbide et al., 2018). There is growing evidence, both from animal studies and human neuroimaging that myelin plays a role in learning (McKenzie et al., 2014; Sampaio-Baptista and Johansen-Berg, 2017) and it might be worthwhile to also consider the role of CC2D1B in central nervous system myelination.

PURβ belongs to the purine-rich element binding (PUR) protein family, which includes of PURα, PURβ and PURγ. There is substantial evidence for PUR role in DNA binding (Rumora et al., 2013; Ferris and Kelm, 2019). Among them, PURα was studied the most, for its implication in fragile × syndrome and PURA syndrome, a disorder characterized by intellectual disability and delayed development of speech and motor skills, such as walking (Johnson et al., 2013; Hunt et al., 2014; Lalani et al., 2014). Interestingly, Purα knockout mice present with reduced myelin production and pathologic development of glial cells (Khalili et al., 2003). However, no knockouts of the other PUR family genes have been reported. PURβ is known to play a role in cell differentiation and modulates transcriptional regulation of gene expression of the α-and β-myosin heavy chain and actin α-2 (Gupta et al., 2003; Ramsey and Kelm, 2009). Notably, TEAD-1, the main transcriptional partner of YAP/TAZ, was reported to be upstream of Purβ (Tsika et al., 2010). TEAD motif-harboring enhancers (GGAAT) can be found in numerous genes dysregulated in Yap cHet; Taz cKO, including CC2D1B and PURβ. Yet, no binding motifs for EGR2 or SOX10 were found in the PURβ enhancer region (Heinz et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that PURβ is a promyelinating regulator directly downstream of YAP/TAZ/TEAD1. Finally, all PUR isoforms have been associated with neoplasia (Johnson et al., 2013).

Although the Cc2d1b and Purβ expression appear to be downstream YAP/TAZ/TEADs, the signals contributing to the regulation of their expression are essentially unknown. Elucidation of the upstream pathways and signals that induce CC2D1B and PURβ will be important both for understanding the molecular control of the myelination program, but also potentially for identifying strategies to promote remyelination in demyelinating disease. Indeed, numerous transcription factor involved in developmental myelination is also involved in remyelination following injury. Thus, it will be critical to characterize the role of CC2D1B and PURB in peripheral nerve repair.

Finally, our study extends regulatory mechanisms directing SC myelinogenesis (Hung et al., 2015; Boerboom et al., 2017; Quintes and Brinkmann, 2017) and supports the transition from a gene-centric to a network-systems view of the myelin formation. Further characterization of the transcription factor network controlling myelin gene expression should help refine our understanding of SC development as well as suggest novel therapeutic strategies to potentiate their regenerative capacity.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Author Contributions

SB and YPo designed research and interpreted data. SB and YPo performed experiments with JH assistance. YPa contributed to analytical tools. YPo wrote the manuscript with SB assistance. SB and YPo analyzed the data. YPa, JV, and LF critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by AMC start-up grant (to YPo) and by National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS: PP-1803-30535) pilot grant (to YPo).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^ http://imagej.nih.gov/ij

- ^ www.mousebrain.org

- ^ www.gtexportal.org

- ^ www.mousebrain.org

- ^ www.gtexportal.org

References

Aragona, M., Panciera, T., Manfrin, A., Giulitti, S., Michielin, F., Elvassore, N., et al. (2013). A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell 154, 1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042

Arroyo, E. J., Bermingham, J. R. Jr., Rosenfeld, M. G., and Scherer, S. S. (1998). Promyelinating schwann cells express Tst-1/SCIP/Oct-6. J. Neurosci. 18, 7891–7902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07891.1998

Basel-Vanagaite, L., Attia, R., Yahav, M., Ferland, R. J., Anteki, L., Walsh, C. A., et al. (2006). The CC2D1A, a member of a new gene family with C2 domains, is involved in autosomal recessive non-syndromic mental retardation. J. Med. Genet. 43, 203–210. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035709

Belin, S., Zuloaga, K. L., and Poitelon, Y. (2017). Influence of mechanical stimuli on schwann cell biology. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:347. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00347

Boerboom, A., Dion, V., Chariot, A., and Franzen, R. (2017). Molecular mechanisms involved in Schwann cell plasticity. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10:38. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00038

Childress, J. L., Acar, M., Tao, C., and Halder, G. (2006). Lethal giant discs, a novel C2-domain protein, restricts notch activation during endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 16, 2228–2233. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.031

Codelia, V. A., Sun, G., and Irvine, K. D. (2014). Regulation of YAP by mechanical strain through Jnk and Hippo signaling. Curr. Biol. 24, 2012–2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.034

Colciago, A., Melfi, S., Giannotti, G., Bonalume, V., Ballabio, M., Caffino, L., et al. (2015). Tumor suppressor Nf2/merlin drives Schwann cell changes following electromagnetic field exposure through Hippo-dependent mechanisms. Cell Death Discov. 1:15021. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.21

Della-Flora Nunes, G., Mueller, L., Silvestri, N., Patel, M. S., Wrabetz, L., Feltri, M. L., et al. (2017). Acetyl-CoA production from pyruvate is not necessary for preservation of myelin. Glia 65, 1626–1639. doi: 10.1002/glia.23184

Deng, Y., Wu, L. M. N., Bai, S., Zhao, C., Wang, H., Wang, J., et al. (2017). A reciprocal regulatory loop between TAZ/YAP and G-protein Gαs regulates Schwann cell proliferation and myelination. Nat. Commun. 8:15161. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15161

Dobretsova, A., Johnson, J. W., Jones, R. C., Edmondson, R. D., and Wight, P. A. (2008). Proteomic analysis of nuclear factors binding to an intronic enhancer in the myelin proteolipid protein gene. J. Neurochem. 105, 1979–1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05288.x

Drusenheimer, N., Migdal, B., Jackel, S., Tveriakhina, L., Scheider, K., Schulz, K., et al. (2015). The mammalian orthologs of Drosophila Lgd, CC2D1A and CC2D1B, function in the endocytic pathway, but their individual loss of function does not affect notch signalling. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005749

Dupont, S. (2016). Role of YAP/TAZ in cell-matrix adhesion-mediated signalling and mechanotransduction. Exp. Cell Res. 343, 42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.034

Dupont, S., Morsut, L., Aragona, M., Enzo, E., Giulitti, S., Cordenonsi, M., et al. (2011). Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137

Elbediwy, A., Vincent-Mistiaen, Z. I., Spencer-Dene, B., Stone, R. K., Boeing, S., Wculek, S. K., et al. (2016). Integrin signalling regulates YAP and TAZ to control skin homeostasis. Development 143, 1674–1687. doi: 10.1242/dev.133728

Feltri, M. L., and Wrabetz, L. (2005). Laminins and their receptors in Schwann cells and hereditary neuropathies. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 10, 128–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.0010204.x

Fernando, R. N., Cotter, L., Perrin-Tricaud, C., Berthelot, J., Bartolami, S., Pereira, J. A., et al. (2016). Optimal myelin elongation relies on YAP activation by axonal growth and inhibition by Crb3/Hippo pathway. Nat. Commun. 7:12186. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12186

Ferris, L. A., and Kelm, R. J. Jr. (2019). Structural and functional analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphic variants of purine-rich element-binding protein B. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 5835–5851. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27869

Fulton, D. L., Denarier, E., Friedman, H. C., Wasserman, W. W., and Peterson, A. C. (2011). Towards resolving the transcription factor network controlling myelin gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 7974–7991. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr326

Gallagher, C. M., and Knoblich, J. A. (2006). The conserved c2 domain protein lethal (2) giant discs regulates protein trafficking in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 11, 641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.014

Ghidinelli, M., Poitelon, Y., Shin, Y. K., Ameroso, D., Williamson, C., Ferri, C., et al. (2017). Laminin 211 inhibits protein kinase A in Schwann cells to modulate neuregulin 1 type III-driven myelination. PLoS Biol. 15:e2001408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001408

Ginkel, C., Hartmann, D., vom Dorp, K., Zlomuzica, A., Farwanah, H., Eckhardt, M., et al. (2012). Ablation of neuronal ceramide synthase 1 in mice decreases ganglioside levels and expression of myelin-associated glycoprotein in oligodendrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41888–41902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m112.413500

Gupta, M., Sueblinvong, V., Raman, J., Jeevanandam, V., and Gupta, M. P. (2003). Single-stranded DNA-binding proteins PURα and PURβ bind to a purine-rich negative regulatory element of the α-myosin heavy chain gene and control transcriptional and translational regulation of the gene expression. Implications in the repression of α-myosin heavy chain during heart failure. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44935–44948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m307696200

Hadjighassem, M. R., Austin, M. C., Szewczyk, B., Daigle, M., Stockmeier, C. A., and Albert, P. R. (2009). Human Freud-2/CC2D1B: a novel repressor of postsynaptic serotonin-1A receptor expression. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.033

Hadjighassem, M. R., Galaraga, K., and Albert, P. R. (2011). Freud-2/CC2D1B mediates dual repression of the serotonin-1A receptor gene. Eur. J. Neurosci. 33, 214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07498.x

He, Y., Kim, J. Y., Dupree, J., Tewari, A., Melendez-Vasquez, C., Svaren, J., et al. (2010). Yy1 as a molecular link between neuregulin and transcriptional modulation of peripheral myelination. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1472–1480. doi: 10.1038/nn.2686

Heinz, S., Benner, C., Spann, N., Bertolino, E., Lin, Y. C., Laslo, P., et al. (2010). Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004

Hung, H. A., Sun, G., Keles, S., and Svaren, J. (2015). Dynamic regulation of Schwann cell enhancers after peripheral nerve injury. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6937–6950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m114.622878

Hunt, D., Leventer, R. J., Simons, C., Taft, R., Swoboda, K. J., Gawne-Cain, M., et al. (2014). Whole exome sequencing in family trios reveals de novo mutations in PURA as a cause of severe neurodevelopmental delay and learning disability. J. Med. Genet. 51, 806–813. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102798

Huppke, P., Weissbach, S., Church, J. A., Schnur, R., Krusen, M., Dreha-Kulaczewski, S., et al. (2017). Activating de novo mutations in NFE2L2 encoding NRF2 cause a multisystem disorder. Nat. Commun. 8:818. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00932-7

Imgrund, S., Hartmann, D., Farwanah, H., Eckhardt, M., Sandhoff, R., Degen, J., et al. (2009). Adult ceramide synthase 2 (CERS2)-deficient mice exhibit myelin sheath defects, cerebellar degeneration and hepatocarcinomas. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33549–33560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109.031971

Jaekel, R., and Klein, T. (2006). The Drosophila Notch inhibitor and tumor suppressor gene lethal (2) giant discs encodes a conserved regulator of endosomal trafficking. Dev. Cell 11, 655–669. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.019

Jang, S. W., Srinivasan, R., Jones, E. A., Sun, G., Keles, S., Krueger, C., et al. (2010). Locus-wide identification of Egr2/Krox20 regulatory targets in myelin genes. J. Neurochem. 115, 1409–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07045.x

Johnson, E. M., Daniel, D. C., and Gordon, J. (2013). The pur protein family: genetic and structural features in development and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 228, 930–937. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24237

Khalili, K., Del Valle, L., Muralidharan, V., Gault, W. J., Darbinian, N., Otte, J., et al. (2003). Purα is essential for postnatal brain development and developmentally coupled cellular proliferation as revealed by genetic inactivation in the mouse. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 6857–6875. doi: 10.1128/mcb.23.19.6857-6875.2003

Kim, N. G., and Gumbiner, B. M. (2015). Adhesion to fibronectin regulates Hippo signaling via the FAK-Src-PI3K pathway. J. Cell Biol. 210, 503–515. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501025

Kim, M. K., Jang, J. W., and Bae, S. C. (2018). DNA binding partners of YAP/TAZ. BMB Rep. 51, 126–133. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2018.51.3.015

Laitman, B. M., Asp, L., Mariani, J. N., Zhang, J., Liu, J., Sawai, S., et al. (2016). The transcriptional activator kruppel-like factor-6 is required for CNS myelination. PLoS Biol. 14:e1002467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002467

Lalani, S. R., Zhang, J., Schaaf, C. P., Brown, C. W., Magoulas, P., Tsai, A. C., et al. (2014). Mutations in PURA cause profound neonatal hypotonia, seizures and encephalopathy in 5q31.3 microdeletion syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 95, 579–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.014

Leblanc, S. E., Srinivasan, R., Ferri, C., Mager, G. M., Gillian-Daniel, A. L., Wrabetz, L., et al. (2005). Regulation of cholesterol/lipid biosynthetic genes by Egr2/Krox20 during peripheral nerve myelination. J. Neurochem. 93, 737–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03056.x

Lopez-Anido, C., Poitelon, Y., Gopinath, C., Moran, J. J., Ma, K. H., Law, W. D., et al. (2016). Tead1 regulates the expression of peripheral myelin protein 22 during schwann cell development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 3055–3069. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw158

Lopez-Anido, C., Sun, G., Koenning, M., Srinivasan, R., Hung, H. A., Emery, B., et al. (2015). Differential Sox10 genomic occupancy in myelinating glia. Glia 63, 1897–1914. doi: 10.1002/glia.22855

Ma, K. H., Hung, H. A., Srinivasan, R., Xie, H., Orkin, S. H., and Svaren, J. (2015). Regulation of peripheral nerve myelin maintenance by gene repression through polycomb repressive complex 2. J. Neurosci. 35, 8640–8652. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2257-14.2015

Manzini, M. C., Xiong, L., Shaheen, R., Tambunan, D. E., Di Costanzo, S., Mitisalis, V., et al. (2014). CC2D1A regulates human intellectual and social function as well as NF-κB signaling homeostasis. Cell Rep. 8, 647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.039

McKenzie, I. A., Ohayon, D., Li, H., De Faria, J. P., Emery, B., Tohyama, K., et al. (2014). Motor skill learning requires active central myelination. Science 346, 318–322. doi: 10.1126/science.1254960

Michailov, G. V., Sereda, M. W., Brinkmann, B. G., Fischer, T. M., Haug, B., Birchmeier, C., et al. (2004). Axonal neuregulin-1 regulates myelin sheath thickness. Science 304, 700–703. doi: 10.1126/science.1095862

Mohseni, M., Sun, J., Lau, A., Curtis, S., Goldsmith, J., Fox, V. L., et al. (2014). A genetic screen identifies an LKB1-MARK signalling axis controlling the Hippo-YAP pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 108–117. doi: 10.1038/ncb2884

Monk, K. R., Feltri, M. L., and Taveggia, C. (2015). New insights on Schwann cell development. Glia 63, 1376–1393. doi: 10.1002/glia.22852

Nagarajan, R., Svaren, J., Le, N., Araki, T., Watson, M., and Milbrandt, J. (2001). EGR2 mutations in inherited neuropathies dominant-negatively inhibit myelin gene expression. Neuron 30, 355–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00282-3

Notterpek, L., Snipes, G. J., and Shooter, E. M. (1999). Temporal expression pattern of peripheral myelin protein 22 during in vivo and in vitro myelination. Glia 25, 358–369. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(19990215)25:4<358::AID-GLIA5>3.0.CO;2-K

Poitelon, Y., Bogni, S., Matafora, V., Della-Flora Nunes, G., Hurley, E., Ghidinelli, M., et al. (2015). Spatial mapping of juxtacrine axo-glial interactions identifies novel molecules in peripheral myelination. Nat. Commun. 6:8303. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9303

Poitelon, Y., and Feltri, M. L. (2018). The pseudopod system for axon-glia interactions: stimulation and isolation of schwann cell protrusions that form in response to axonal membranes. Methods Mol. Biol. 1739, 233–253. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7649-2_15

Poitelon, Y., Kozlov, S., Devaux, J., Vallat, J. M., Jamon, M., Roubertoux, P., et al. (2012). Behavioral and molecular exploration of the AR-CMT2A mouse model Lmna (R298C/R298C). Neuromolecular Med. 14, 40–52. doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8168-z

Poitelon, Y., Lopez-Anido, C., Catignas, K., Berti, C., Palmisano, M., Williamson, C., et al. (2016). YAP and TAZ control peripheral myelination and the expression of laminin receptors in Schwann cells. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 879–887. doi: 10.1038/nn.4316

Quintes, S., and Brinkmann, B. G. (2017). Transcriptional inhibition in Schwann cell development and nerve regeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 12, 1241–1246. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.213537

Quintes, S., Brinkmann, B. G., Ebert, M., Frob, F., Kungl, T., Arlt, F. A., et al. (2016). Zeb2 is essential for Schwann cell differentiation, myelination and nerve repair. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nn.4321

Ramsey, J. E., and Kelm, R. J. Jr. (2009). Mechanism of strand-specific smooth muscle α-actin enhancer interaction by purine-rich element binding protein B (Purβ). Biochemistry 48, 6348–6360. doi: 10.1021/bi900708j

Roberts, S. L., Dun, X. P., Doddrell, R. D. S., Mindos, T., Drake, L. K., Onaitis, M. W., et al. (2017). Sox2 expression in Schwann cells inhibits myelination in vivo and induces influx of macrophages to the nerve. Development 144, 3114–3125. doi: 10.1242/dev.150656

Rumora, A. E., Wang, S. X., Ferris, L. A., Everse, S. J., and Kelm, R. J. Jr. (2013). Structural basis of multisite single-stranded DNA recognition and ACTA2 repression by purine-rich element binding protein B (Purβ). Biochemistry 52, 4439–4450. doi: 10.1021/bi400283r

Sampaio-Baptista, C., and Johansen-Berg, H. (2017). White matter plasticity in the adult brain. Neuron 96, 1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.026

Svaren, J., and Meijer, D. (2008). The molecular machinery of myelin gene transcription in Schwann cells. Glia 56, 1541–1551. doi: 10.1002/glia.20767

Taveggia, C., Zanazzi, G., Petrylak, A., Yano, H., Rosenbluth, J., Einheber, S., et al. (2005). Neuregulin-1 type III determines the ensheathment fate of axons. Neuron 47, 681–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.017

Topilko, P., Schneider-Maunoury, S., Levi, G., Baron-Van Evercooren, A., Chennoufi, A. B., Seitanidou, T., et al. (1994). Krox-20 controls myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature 371, 796–799. doi: 10.1038/371796a0

Tretiakova, A., Steplewski, A., Johnson, E. M., Khalili, K., and Amini, S. (1999). Regulation of myelin basic protein gene transcription by Sp1 and Purα: evidence for association of Sp1 and Purα in brain. J. Cell. Physiol. 181, 160–168. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4652(199910)181:1<160::aid-jcp17>3.0.co;2-h

Tsika, R. W., Ma, L., Kehat, I., Schramm, C., Simmer, G., Morgan, B., et al. (2010). TEAD-1 overexpression in the mouse heart promotes an age-dependent heart dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13721–13735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109.063057

Verheijen, M. H., Camargo, N., Verdier, V., Nadra, K., De Preux Charles, A. S., Medard, J. J., et al. (2009). SCAP is required for timely and proper myelin membrane synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 21383–21388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905633106

Weng, Q., Chen, Y., Wang, H., Xu, X., Yang, B., He, Q., et al. (2012). Dual-mode modulation of Smad signaling by Smad-interacting protein Sip1 is required for myelination in the central nervous system. Neuron 73, 713–728. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.021

Woodhoo, A., Alonso, M. B., Droggiti, A., Turmaine, M., D’Antonio, M., Parkinson, D. B., et al. (2009). Notch controls embryonic Schwann cell differentiation, postnatal myelination and adult plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 839–847. doi: 10.1038/nn.2323

Wu, L. M., Wang, J., Conidi, A., Zhao, C., Wang, H., Ford, Z., et al. (2016). Zeb2 recruits HDAC-NuRD to inhibit Notch and controls Schwann cell differentiation and remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1060–1072. doi: 10.1038/nn.4322

Yamaguchi, H., Zhou, C., Lin, S. C., Durand, B., Tsai, S. Y., and Tsai, M. J. (2004). The nuclear orphan receptor COUP-TFI is important for differentiation of oligodendrocytes. Dev. Biol. 266, 238–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.038

Yuen, T. J., Silbereis, J. C., Griveau, A., Chang, S. M., Daneman, R., Fancy, S. P. J., et al. (2014). Oligodendrocyte-encoded HIF function couples postnatal myelination and white matter angiogenesis. Cell 158, 383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.052

Zamarbide, M., Oaks, A. W., Pond, H. L., Adelman, J. S., and Manzini, M. C. (2018). Loss of the intellectual disability and autism gene Cc2d1a and its homolog cc2d1b differentially affect spatial memory, anxiety and hyperactivity. Front. Genet. 9:65. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00065

Zhang, Y., Chen, K., Sloan, S. A., Bennett, M. L., Scholze, A. R., O’Keeffe, S., et al. (2014). An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 34, 11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014

Keywords: Yap, Taz, Cc2d1b, Purβ, myelin, Schwann cell

Citation: Belin S, Herron J, VerPlank JJS, Park Y, Feltri LM and Poitelon Y (2019) YAP and TAZ Regulate Cc2d1b and Purβ in Schwann Cells. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12:177. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00177

Received: 24 March 2019; Accepted: 04 July 2019;

Published: 17 July 2019.

Edited by:

Ildikó Rácz, Universitätsklinikum Bonn, GermanyReviewed by:

Dies Meijer, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomLi-Jin Chew, Children’s National Health System, United States

Rachelle Franzen, University of Liège, Belgium

Copyright © 2019 Belin, Herron, VerPlank, Park, Feltri and Poitelon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yannick Poitelon, poitely@amc.edu

Sophie Belin

Sophie Belin Jacob Herron1

Jacob Herron1 Yannick Poitelon

Yannick Poitelon