94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Neurosci. , 12 May 2023

Sec. Neurodevelopment

Volume 17 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1182845

This article is part of the Research Topic In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Neurodevelopmental Disorders View all 5 articles

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) play an essential role in protein synthesis, being responsible for ligating tRNA molecules to their corresponding amino acids in a reaction known as ‘tRNA aminoacylation’. Separate ARSs carry out the aminoacylation reaction in the cytosol and in mitochondria, and mutations in almost all ARS genes cause pathophysiology most evident in the nervous system. Dominant mutations in multiple cytosolic ARSs have been linked to forms of peripheral neuropathy including Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, distal hereditary motor neuropathy, and spinal muscular atrophy. This review provides an overview of approaches that have been employed to model each of these diseases in vivo, followed by a discussion of the existing animal models of dominant ARS disorders and key mechanistic insights that they have provided. In summary, ARS disease models have demonstrated that loss of canonical ARS function alone cannot fully account for the observed disease phenotypes, and that pathogenic ARS variants cause developmental defects within the peripheral nervous system, despite a typically later onset of disease in humans. In addition, aberrant interactions between mutant ARSs and other proteins have been shown to contribute to the disease phenotypes. These findings provide a strong foundation for future research into this group of diseases, providing methodological guidance for studies on ARS disorders that currently lack in vivo models, as well as identifying candidate therapeutic targets.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) are a group of enzymes that pair amino acids to their complementary tRNA molecules (tRNA aminoacylation), facilitating their incorporation into newly synthesized proteins. tRNA aminoacylation is performed for each proteinogenic amino acid by a specific ARS, and this process occurs separately within the cytosol and mitochondria of each cell (Fröhlich et al., 2018). In the first step of the aminoacylation reaction, known as amino acid ‘activation’, the ARS binds its corresponding amino acid and hydrolyses an ATP molecule to produce an aminoacyl-adenylate (aa-AMP). In the second step of the reaction, this activated amino acid residue is ligated to a matching tRNA molecule, and the AMP molecule is released.

Misacylation of tRNA molecules can lead to the misincorporation of amino acids during protein synthesis, which can be highly deleterious to cellular function (Nangle et al., 2006; Fröhlich et al., 2017; Kapur and Ackerman, 2018). To maintain high fidelity of protein translation, if an ARS incorrectly activates the wrong amino acid, this error can be rectified through hydrolysis of the aa-AMP prior to the second step of the aminoacylation reaction (‘pre-transfer editing’), or after the tRNA molecule has been misacylated (‘post-transfer editing’). Multiple ARSs possess editing domains for post-transfer editing, and editing can also be carried out in trans by separate editing proteins (Perona and Gruic-Sovulj, 2014).

Genes encoding ARSs are named according to their target amino acid, and whether they function within the cytosol (ARS1) or mitochondria (ARS2); for example, the cytosolic tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) is encoded by YARS1, and its mitochondrial counterpart is encoded by YARS2. In most cases, cytosolic and mitochondrial ARSs are encoded by separate genes, apart from two bifunctional ARSs; glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GlyRS) and lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS), which are each encoded by a single gene. All ARS genes are encoded by nuclear DNA and translated in the cytosol, with mitochondrial ARSs subsequently imported into the mitochondria.

In addition to their canonical role in tRNA aminoacylation, ARSs have evolved to perform several additional cellular functions. These secondary ARS functions have been reviewed elsewhere (Guo and Schimmel, 2013; Lo et al., 2014), with some examples of non-canonical ARS functions including regulation of vascular development (Mirando et al., 2014), immune responses (Nie et al., 2019), and metabolism (Arif et al., 2017).

Mutations in all ARS genes have been linked to disease. Recessive mutations in cytosolic and mitochondrial ARS genes often cause multi-system disorders, predominantly involving the central nervous system (Ognjenovic and Simonovic, 2018; Fuchs et al., 2019; Muthiah et al., 2020). To date, dominant mutations in ARS2 genes have not been implicated in human disease. In contrast, dominant mutations in multiple cytosolic and bifunctional ARS genes have been linked to peripheral neuropathies (Wei et al., 2019). Recently, the clinical spectrum associated with monoallelic ARS1 variants has been expanded to also include disorders of the central nervous system, which resemble diseases typically associated with recessive ARS1 mutations. Specifically, mutations in AARS1 have been identified as the likely cause of Swedish-type hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids 2 (HDLS2 or HDLS-S) (Sundal et al., 2019), and a dominant HARS1 variant has been linked to cerebellar degeneration, cognitive impairments, and peripheral neuropathy (Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019). Dominant mutations in NARS1 have been identified as a cause of neurodevelopmental disorder with microcephaly, impaired language, epilepsy, and gait abnormalities (NEDMILEG) (Manole et al., 2020). Additionally, a monoallelic KARS1 variant was recently linked to a case of severe anaphylaxis resulting from dysregulation of the non-canonical function of LysRS in activating immune cells (Ribó et al., 2021). The differing inheritance pattern and largely non-overlapping clinical presentations of patients with central and peripheral nervous system disorders suggests that these represent distinct groups of diseases, with divergent pathomechanisms. This review will primarily focus on the association between dominant ARS1 variants and peripheral neuropathy.

Thus far, autosomal dominant mutations in AARS1, GARS1, HARS1, MARS1, WARS1, SARS1 and YARS1 have been linked to peripheral neuropathies, predominantly Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease (Table 1). CMT is characterized by length-dependent degeneration of peripheral motor and sensory neurons, causing distal muscle atrophy and weakness, sensory loss, and diminished deep tendon reflexes (Gutmann and Shy, 2015). Neuronal degeneration can result from demyelination (CMT Type 1; CMT1), or from primary axonal dysfunction (CMT Type 2; CMT2). These categories can be differentiated electrophysiologically, with motor nerve conduction velocities (MNCV) <38 m/s indicative of CMT1, and MNCV >38 m/s designated as CMT2. Individuals with MNCV between 25 m/s and 45 m/s are generally classified as having an intermediate form of CMT (Reilly, 2009). ARS1 mutations have so far been associated with CMT2 and dominant intermediate CMT (DI-CMT), as well as forms of distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), which have overlapping clinical features with CMT. There are currently no curative treatments for ARS-associated neuropathies, or for inherited peripheral neuropathies in general.

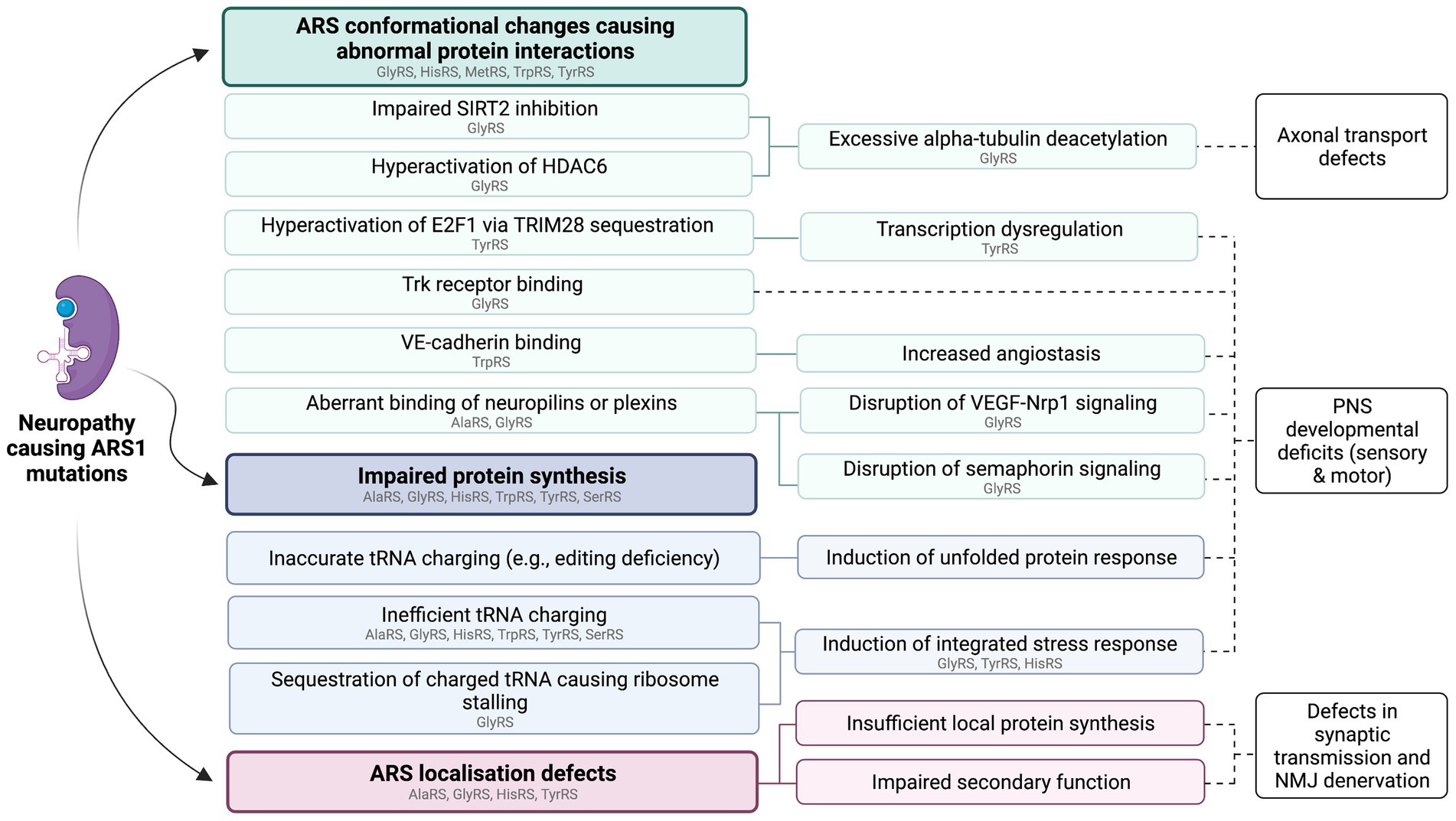

Based on the available evidence, loss of aminoacylation function cannot fully account for the association between dominant ARS mutations and neuropathy. For neuropathy associated ARS1 variants, loss of aminoacylation function in vitro is a common feature, but not a prerequisite for disease (Nangle et al., 2007). Additionally, heterozygous knockouts of ARS1 genes implicated in dominant human ARS diseases are not sufficient to trigger the disease phenotypes in mice (Seburn et al., 2006; Dickinson et al., 2016; Hines et al., 2021), and human heterozygous carriers of loss-of-function ARS mutations are not always affected (Galatolo et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2020). This indicates that the neuropathy phenotype is not caused by haploinsufficiency, suggesting that neuropathy-linked ARS variants exert dominant-negative effects on protein function or confer toxic gain-of-function effects. An overview of proposed disease pathways for ARS-associated neuropathies is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Summary of proposed functional consequences of dominant ARS1 mutations. These pathways are not mutually exclusive and may act synergistically to cause ARS1-associated neuropathy. Individual variants of the same ARS may cause disease via different mechanisms. ARSs with variants that have so far been implicated in specific pathways through in vitro or in vivo studies are listed in gray. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

In vivo models for neuropathy causing ARS1 variants have been produced in Caenorhabditis (C.) elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, zebrafish, and mice (Table 1). The dominant neurotoxicity of two CMT-causing HARS1 variants have been evaluated through overexpression of equivalent variants in C. elegans (Vester et al., 2013; Safka Brozkova et al., 2015). In Drosophila, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated ARS1 knockdown and expression of multiple ARS1 variants have been investigated using the UAS-GAL4 system (Morant et al., 2021). Zebrafish CMT models have been created using forward genetic screens, expression of hypomorphic and hypermorphic human ARS1 variants (Weterman et al., 2018), and overexpression of mutant ARSs equivalent to human patient mutations (Malissovas et al., 2016; Mullen et al., 2021). Mouse models for CMT have been generated using forward genetic screens (Seburn et al., 2006; Achilli et al., 2009), gene trapping (Seburn et al., 2006), and through the introduction of human disease-causing mutations into the mouse genome (Morelli et al., 2019).

Models for ARS1-associated neuropathy have so far been generated for GARS1, YARS1, HARS1, and AARS1. There are currently no animal studies addressing dHMN9 caused by WARS1 mutations, CMT2U caused by MARS1 mutations, or for the form of CMT caused by SARS1 mutations.

Dominant mutations in GARS1, which encodes the bifunctional glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GlyRS), cause CMT2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V (DSMAV) (Antonellis et al., 2003). CMT2D and DSMAV patients typically present with slowly progressing muscle weakness and atrophy, most pronounced in the upper extremities. In addition to motor impairment, CMT2D patients exhibit sensory loss. The severity of sensory deficits among CMT2D patients is variable, predominantly affecting the upper extremities. GARS1 mutations have also been linked to a form of infantile spinal muscular atrophy with a typical clinical presentation of progressive muscle weakness in both upper and lower limbs, sometimes preventing independent ambulation (James et al., 2006; Markovitz et al., 2020). Additionally, some patients present with respiratory failure and eating difficulties (Markovitz et al., 2020). For each of these GARS1-associated disorders, patients exhibit variable reductions in MNCV, as well as in sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) and compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitudes. Sural nerve biopsies show evidence of axonal degeneration, without signs of demyelination (Sivakumar et al., 2005).

Despite the different disease classifications, there is substantial phenotypic overlap between the GARS1-associated neuropathies. DSMAV and CMT2D can be caused by the same GARS1 mutations (Sivakumar et al., 2005; Del Bo et al., 2006), suggesting that these conditions represent a spectrum of GARS1 associated axonal neuropathy, rather than distinct diseases (Sivakumar et al., 2005; Sleigh et al., 2017a).

As the first ARS to be associated with human disease, GlyRS mutations have been the most extensively studied, and were the first dominant ARS variants to be modeled in mammals.

The first mouse model of CMT2D was established in 2006 after identification of the dominant Nmf249 Gars1 mutation (P278KY; equivalent to human P234KY) in a forward genetic screen (Seburn et al., 2006). The P278KY amino acid substitution is located near the human disease-causing G240R variant. Homozygosity for the P278KY variant is embryonically lethal. Heterozygous expression of P278KY GlyRS (Gars1P278KY/+) causes neuromuscular dysfunction in mice by 3 weeks of age, and a high mortality rate by 6–8 weeks. Gars1P278KY/+ mice show progressive neuromuscular junction (NMJ) denervation and length-dependent loss of peripheral sensory and motor axons. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) is significantly decreased in Gars1P278KY/+ mice, resulting from loss of large-diameter axons rather than myelination defects. Mice that survive past 8 weeks display only moderate disease progression beyond this timepoint. Gars1 mRNA levels are unaffected by the P278KY mutation, and aminoacylation levels measured from brain tissue of Gars1P278KY/+ mice are comparable to wildtype mice.

While the Gars1P278KY/+ model recapitulates key hallmarks of CMT2D pathology, the phenotype is more severe than in human patients. A second CMT2D mouse model with a milder neuropathy phenotype (Gars1C201R/+) was developed using N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis (Achilli et al., 2009). By 1 month of age, Gars1C201R/+ mice show a reduction in grip strength, hindlimb muscle force, and fine motor control. As with human patients, certain muscles are more affected than others, and the severity of muscle weakness directly corresponds to denervation of the NMJ. The number of motor neurons does not differ between Gars1C201R/+ and wildtype mice, indicating that the NMJ denervation in Gars1C201R/+ mice is the result of axonal degeneration rather than cell death. No demyelination was observed in the Aβ fibers of the saphenous nerve, however, Gars1C201R/+ mice have smaller diameter axons than wildtype mice, resulting in a slower sensory NCV and a reduction in nerve excitability. As with P278KY, homozygosity for the C201R mutation is lethal. While a small number of homozygous Gars1C201R mice are born, none of these animals survive past postnatal day (P) 17. Unlike Gars1P278KY/+ mice, Gars1C201R/+ mice have a normal lifespan. Analysis of brain tissue homogenates at P15 showed a significant, possibly compensatory, increase in GlyRS protein levels in heterozygous and homozygous Gars1C201R mice compared to wildtype mice, which normalized by 3 months. There were no significant differences in GlyRS aminoacylation activity between heterozygous and wildtype mice at P15 or P90, but homozygous Gars1C201R mice displayed a 60% reduction in enzyme activity at P15.

A third mouse model was developed through the introduction of a patient mutation (p.Glu299_Gln302del) into the mouse genome (Gars1delETAQ) (Morelli et al., 2019). The four amino acid residues that are deleted in the Gars1delETAQ variant are located within the glycine-binding pocket of GlyRS. GlyRS protein levels are unaffected by the mutation, as measured in both patient and mouse cells. To allow for testing of allele-specific RNAi of mutant Gars1 as a potential treatment strategy for CMT2D, the Gars1delETAQ/+ mouse strain was crossed with mice homozygously carrying exon 8 of the human GARS1 gene (Gars1huEx8), producing compound heterozygous Gars1delETAQ/huEx8 mice. At 12 weeks of age, Gars1delETAQ/huEx8 mice demonstrate reduced grip strength and decreased bodyweight. The mutant mice also display decreased axon diameter, reduced motor and sensory NCV, and variable NMJ denervation in distal muscles, as previously seen in the Gars1P278KY/+ and Gars1C201R/+ mice. Unlike the other two Gars1 variants, Gars1delETAQ retains less than 0.01% aminoacylation activity. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated RNAi of the mutant Gars1delETAQ allele successfully alleviated the pathological phenotype of Gars1delETAQ/huEx8 mice.

Adenovirus-mediated expression of the patient variants p.Leu129Pro and p.Gly240Arg (GARS1L129P and GARS1G240R) in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons has also been used to model CMT2D neuropathy in mice (Lee et al., 2014). The adenovirus was injected into the sciatic nerve of wildtype adult C57BL/6 mice, with expression of FLAG-tagged human GARS1 variants under control of the mouse choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) promoter, and expression of a GFP reporter under a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. To prevent mitochondrial expression of mutant GlyRS, the mitochondrial targeting sequence was removed from the GARS1 sequence. Mice expressing GARS1L129P and GARS1G240R exhibit allodynia and elevation of multiple markers of peripheral nerve injury and neuropathic pain, including increased microglia, expression of activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), and activation of p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) in mutant GARS1-expressing DRG neurons (Lee et al., 2014). The pathogenic GARS1 mutations also appear to cause a localization defect of GlyRS within peripheral neurons. G240R mutant GlyRS was absent from axons within the sciatic nerve compared to the uniform distribution of wildtype GlyRS throughout the axon, in addition to reduced expression of G240R GlyRS in the central processes of DRG neurons (Lee et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2014b). Likewise, distribution of L129P GlyRS was defective in projections of DRG neurons and peripheral axons, as well as in processes of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Seo et al., 2014a). Expression of mutant and wildtype GlyRS was unaltered in motor and sensory neuron cell bodies in the dorsal and ventral horns of the spinal cord (Seo et al., 2014a,b). Consistent with the clinical presentation of CMT2D, no myelination defects were observed in mice overexpressing mutant GARS1 (Seo et al., 2014a,b).

Interestingly, the severity of the Gars1P278KY and Gars1C201R mutations differ between mice from different genetic backgrounds, mirroring the clinical variability among patients. The Gars1C201R mutation results in a more severe phenotype on the C57BL/6 background than in C3H mice (Achilli et al., 2009), and the average lifespan of Gars1P278KY/+ mice differs between strains (Seburn et al., 2006). These results have methodological implications, highlighting the importance of considering genetic backgrounds when producing mouse models, and when evaluating or comparing results between studies. Additionally, as discussed by Achilli et al. (2009), the heterogeneity between strains implies the presence of genetic modifiers of the disease phenotype, which could be used as potential treatment targets once identified (Achilli et al., 2009). A more recent study identified genes that modified aspects of the abnormal phenotypes elicited in Drosophila by both GlyRS and TyrRS variants associated with neuropathy (Ermanoska et al., 2014). Although the specific modifier genes identified in this study do not have vertebrate orthologs, it is probable that there are other genetic modifiers, which account for the broad disease spectrum in human patients. If these modifiers are shared across different ARS1-related neuropathies, they could represent broadly applicable therapeutic targets.

Animal models have provided functional insights into CMT2D progression at the cellular level. Despite the later onset of CMT2D during adolescence or adulthood, expression of mutant GlyRS impairs early nervous system development in both Drosophila and mice. Ubiquitous expression of the GlyRSG240R variant in Drosophila causes high rates of mortality during the late pupal stage, and expression of the severe GlyRSP234KY variant (equivalent to mouse Gars1P278KY) is lethal during the first instar (Ermanoska et al., 2014). Conditional expression of GlyRSG240R in the nervous system of Drosophila causes progressive motor deficits, and expression of GlyRSP234KY within the nervous system is lethal in the final stages of development, further demonstrating the neurotoxicity of CMT2D-associated GlyRS variants (Ermanoska et al., 2014). Interestingly, mesoderm- or muscle-specific expression of GlyRSP234KY in Drosophila perturbs axonal branching in the peripheral nervous system during development (Grice et al., 2018), and leads to an abnormal accumulation of mutant GlyRS at the NMJ pre-synapse (Grice et al., 2015, 2018), indicating that mutant GlyRS also exerts non-cell autonomous toxicity.

Longitudinal characterization of the NMJs of Gars1P278KY/+ and Gars1C201R/+ mice has shown that abnormal development of the NMJ synapse precedes the progressive denervation of distal hindlimb muscles (Sleigh et al., 2014). Among axons of similar length, the severity of denervation correlates with levels of postnatal synaptic growth, suggesting that developmental demands exacerbate the consequences of neuropathy associated GlyRS mutations (Sleigh et al., 2020b). Gars1P278KY/+ mice have a reduced number of mitochondria within NMJ presynaptic terminals, which may account for their inability to meet high energy demands during development (Spaulding et al., 2016). Since GlyRS is a bifunctional ARS, this mitochondrial deficiency could arise directly from impaired mitochondrial GlyRS function.

Overexpression of mutant GlyRS in Drosophila either during or post-development impairs synaptic transmission in the giant fiber (GF) circuit (Ermanoska et al., 2014), and both Gars1P278KY/+ and Gars1C201R/+ mice exhibit progressive deficits in NMJ synaptic transmission that correlate with phenotype severity (Spaulding et al., 2016). Presynaptic neurons at the affected NMJs of CMT2D mice have abnormally thin axons and small presynaptic terminals containing fewer vesicles than those of wildtype mice (Spaulding et al., 2016). Likewise, expression of mutant GlyRS in Drosophila causes thinning of the GF axon, as well as vacuolization throughout the axon and presynaptic terminal (Ermanoska et al., 2014). Increasing activation of postsynaptic receptors through intraperitoneal administration of physostigmine improves motor performance in CMT2D mice, confirming that defects in synaptic transmission contribute to the pathological phenotype, and identifying a potential treatment target (Spaulding et al., 2016).

In contrast to the ongoing deterioration of motor neurons, developmental abnormalities in sensory neurons of CMT2D mice are evident from birth and appear to be nonprogressive (Sleigh et al., 2020a). Specifically in lumbar DRGs of Gars1C201R/+ and Gars1P278KY/+ mice, there is an abnormally large proportion of nociceptive neurons relative to mechanosensitive and proprioceptive neurons, and nociceptive neurons of the hind paws exhibit impaired arborization (Sleigh et al., 2017a, 2020a). CMT2D mice additionally show increased expression of capsaicin receptors in thermal nociceptor neurons. The severity of these cellular abnormalities correlate with the relative severity of the Gars1C201R/+ and Gars1P278KY/+ mutant phenotypes. The sensory developmental deficits of CMT2D mice manifest behaviorally as hypersensitivity to thermally nociceptive stimuli, and reduced mechanosensation (Sleigh et al., 2017a). Analysis of GlyRS expression levels in DRG neurons of Gars1C201R/+ and Gars1P278KY/+ mice revealed a preferential increase of GlyRS in lumbar mechanosensitive and proprioceptive neurons, which could represent a compensatory upregulation in response to cellular stress in this particular subpopulation of neurons (Sleigh et al., 2020a).

In vivo experiments have demonstrated that compromised GlyRS aminoacylation function can result in peripheral nerve defects. GlyRS functions as a homodimer, and homozygous expression of the dimerization-incapable gars1T209K variant in zebrafish caused a loss of GlyRS aminoacylation function, which led to a decrease in NMJ innervation, impaired muscle development, and abnormal formation of their cardiac valves. A similar phenotype could be produced in wildtype zebrafish through inhibition of protein synthesis between 24 and 96 h post fertilization, suggesting that loss of GlyRS aminoacylation activity impairs protein translation in gars1T209K zebrafish (Malissovas et al., 2016).

Despite the apparent sensitivity of NMJ development to impaired protein synthesis, the precise relationship between CMT2D pathogenesis and loss of GlyRS canonical function remains unclear, as not all CMT2D-causing GARS1 variants impair aminoacylation activity (Nangle et al., 2007). Gars1P278KY/+ mice exhibit a severe neuropathy phenotype despite retaining normal aminoacylation function and GlyRS expression levels (Seburn et al., 2006). Likewise, analysis of brain lysates from Gars1C201R/+ mice showed comparable levels of aminoacylation activity to wildtype mice (Achilli et al., 2009). In contrast, despite reducing Gars1 expression by 50%, heterozygous Gars1 knockout in mice (Gars1XM256/+) does not trigger a disease phenotype (Seburn et al., 2006), demonstrating that the neuropathy is not caused by haploinsufficiency.

However, despite retaining normal aminoacylation capacity in trans to wildtype GlyRS, neither the Gars1P278KY nor the Gars1C201R variants can complement a loss-of-function allele (Achilli et al., 2009; Motley et al., 2011). The canonical role of GlyRS in protein translation could potentially be disrupted through alternative mechanisms, such as mislocalisation or decreased accuracy in tRNA charging. Multiple CMT2D GlyRS variants impair the transport of GlyRS into neurite projections in vitro (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007). The in vivo effects of CMT2D mutations on GlyRS localization are inconclusive (Stum et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2014a,b; Niehues et al., 2015), and it remains to be seen if mislocalisation of mutant GlyRS contributes to the CMT2D phenotype. Mischarging of tRNA by mutant GlyRS could conceivably also lead to neurodegeneration through toxic accumulation of misfolded proteins, which is a major pathological hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Parakh and Atkin, 2016). However, there is so far no evidence of misfolded proteins aggregating in vitro (Antonellis et al., 2006) or within the nervous system of CMT2D mice (Stum et al., 2011) arguing against tRNA mischarging as the primary cause of CMT2D pathophysiology.

Since GlyRS is a bifunctional ARS, mitochondrial dysfunction might contribute to the CMT2D pathophysiology. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and impaired mitochondrial trafficking have previously been implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple axonal neuropathies (McCray and Scherer, 2021). Whilst several mitochondrial abnormalities were observed within induced neuronal progenitor cells (iNPCs) generated from fibroblasts of a DSMAV patient, these were not detected in Gars1C201R/+ mice (Boczonadi et al., 2018). Additionally, expression of mutant GlyRS exclusively in the cytosol is sufficient to trigger peripheral neuropathy in Drosophila (Ermanoska et al., 2014) and mice (Lee et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2014a,b), suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction is not the primary cause of CMT2D neuropathy. Nevertheless, mitochondrial deficits have been observed in Gars1P278KY/+ mice, including a reduction in the number of mitochondria at synaptic terminals of hindlimb NMJs (Spaulding et al., 2016), and decreased oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in the gastrocnemius muscle (Ozes et al., 2021). Together, these results suggest that while neuropathy can occur independently of mitochondrial dysfunction, this may still be a contributing factor to the CMT2D pathology.

Although many of the GlyRS variants identified to date exhibit loss-of-function characteristics (Griffin et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021b), a common loss-of-function mechanism has not yet been identified among the CMT2D GlyRS variants. This divergence could account for some of the heterogeneity in clinical presentations among patients carrying different GlyRS mutations.

Irrespective of their effects on normal GlyRS function, there is converging evidence that pathogenic GlyRS mutations exert toxic gain-of-function effects. Overexpression of mutant GlyRS on the background of active endogenous GlyRS in Drosophila induces a CMT2D phenotype (Ermanoska et al., 2014), and expression of the Gars1C201R and Gars1P278KY variants in mice show dose-dependent toxicity, which cannot be counteracted with overexpression of wildtype GlyRS (Motley et al., 2011). In addition, a subsequent study demonstrated that the neuropathy phenotypes of both Gars1P278KY/+ and Gars1delETAQ/+ mice could be rescued through AAV-mediated RNAi of the mutant alleles, supporting the toxic gain-of-function hypothesis, and providing proof-of-concept for an AAV-mediated gene therapy approach for CMT2D (Morelli et al., 2019).

Many of the disease associated GARS1 mutations cause conformational changes, exposing new surfaces of the GlyRS protein, which enable abnormal interactions with other proteins (He et al., 2011, 2015). Studies conducted in both mice and Drosophila have provided evidence of aberrant interactions between mutant GlyRS and multiple novel binding partners contributing to the neuropathy phenotype. These results are discussed in the following sections.

Consistent with the developmental defects observed in CMT2D animal models, pathogenic GlyRS variants interfere with signaling pathways that are important for nervous system development. Unlike wildtype GlyRS, several CMT2D causing GlyRS variants strongly bind Neuropilin 1 (Nrp1) in vitro (He et al., 2015; Sleigh et al., 2017b; Mo et al., 2018), thereby competing with the binding of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A). In mice, the strength of the GlyRS-Nrp1 binding directly correlates with disease severity, with lower affinity between GlyRS and Nrp1 resulting in milder disease (Sleigh et al., 2017b). VEGF-Nrp1 signaling plays a role in vascularization, as well as having a neuroprotective effect in peripheral motor neurons (Oosthuyse et al., 2001; Kofler and Simons, 2015). Treating Gars1P278KY/+ mice with VEGF-A injections into the hindlimbs prior to the onset of neuropathy reduced the severity of motor deficits (He et al., 2015). Future studies should validate whether the pathological effects of other CMT2D variants that bind Nrp1 can similarly be counteracted through VEGF-A administration.

In addition to VEGF-A signaling, Nrp1 also plays a role in semaphorin signaling (Gu et al., 2003). Semaphorins are a family of signaling proteins that control developmental processes of the nervous system including neurogenesis, axonal pathfinding, and synapse formation through interactions with their receptors, which include plexins and neuropilins (Limoni and Niquille, 2021). In Drosophila there is no ortholog of the vertebrate Nrp1 gene, with semaphorin signaling occurring via interactions with plexins that are encoded by two genes, plexA and plexB (Grice et al., 2018). Heterozygous knockout of these genes exacerbates the axonal branching defects caused by overexpression of GlyRSP234KY, suggesting that disrupted plexin signaling may underlie the developmental abnormalities seen in GlyRSP234KY Drosophila (Grice et al., 2018). Additionally, interactions between mutant GlyRS and plexB contribute to the accumulation of GlyRS at the NMJ presynaptic terminal and interfere with the capacity of plexB to bind semaphorin-2a. This interaction directly contributes to the neuropathy phenotype, as overexpression of semaphorin-2a attenuates the pathology in GlyRSP234KY Drosophila (Grice et al., 2018). Restoration of semaphorin signaling could therefore also be an avenue for treatment of CMT2D, which should be further explored in mammalian disease models.

The abnormal development of sensory neurons in CMT2D mice is hypothesized to be the result of aberrant activation of tropomyosin receptor kinase (Trk) receptors by mutant GlyRS (Sleigh et al., 2017a). The binding of neurotrophins to Trk receptors regulates key processes including neuronal growth, migration and survival (Huang and Reichardt, 2003), and has directly been implicated in the differentiation of sensory neuron subtypes during development (Moqrich et al., 2004). In vitro results demonstrate that mutant GlyRS binds to and activates Trk receptors A-C, and that the extent of variant binding correlates with the severity of the CMT2D phenotype observed in mice (Sleigh et al., 2017a). The functional consequences of GlyRS-Trk binding are yet to be tested in vivo, however, it is plausible that this interaction disrupts sensory neuron development in CMT2D (Sleigh et al., 2017a, 2020a).

In vivo studies have demonstrated that impaired axonal transport contributes to CMT2D pathology. Axonal transport deficits are a common feature of several neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases including CMT neuropathies, owing to the reliance of neurons on efficient and reliable shuttling of various cargoes between the soma and synapses to support cellular function and viability (Sleigh et al., 2019). Excessive deacetylation of α-tubulin has been demonstrated in multiple CMT2D models, disrupting the microtubule cytoskeleton, which forms the basis of axonal transport. Several CMT2D GlyRS mutants aberrantly bind histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) and enhance its activity, significantly decreasing α-tubulin acetylation in peripheral nerves (Benoy et al., 2018; Mo et al., 2018). Another target of HDAC6 is the mitochondrial Rho GTPase 1 (MIRO1), a protein which helps to facilitate mitochondrial transport along the axons and dendrites of motor and sensory neurons (Nguyen et al., 2014; Kalinski et al., 2019). HDAC6 activity has previously been linked to neuropathy through excessive deacetylation of MIRO1 (English and Barton, 2021), and this pathway may similarly be involved in the pathogenesis of CMT2D.

DRG neurons from Gars1P278KY/+ mice exhibit impairments in axonal transport prior to the onset of neuromuscular dysfunction, implying that these transport defects are not secondary consequences of neurodegeneration (Mo et al., 2018). An assay of axonal transport dynamics in DRGs of late-symptomatic GarsC201R/+ mice showed impaired anterograde and retrograde mitochondrial transport (Benoy et al., 2018), possibly accounting for the reduction in mitochondria observed at NMJs of CMT2D mice (Spaulding et al., 2016). HDAC6 inhibition in symptomatic CMT2D mice restored axonal transport in DRG neurons and improved both sensory and motor function (Benoy et al., 2018; Mo et al., 2018). Consistently, HDAC6 inhibition also reversed axonal transport deficits in GARS1P234KY and GARS1P724H human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines (Smith et al., 2021).

Also contributing to the hypoacetylation of α-tubulin in CMT2D mice is impaired inhibition of the NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) by mutant GlyRS. Wildtype GlyRS binds SIRT2, thereby inhibiting its deacetylation activity. CMT2D GlyRS variants have reduced binding affinity for SIRT2, leading to an increase in SIRT2 deacetylase activity (Zhao et al., 2021). Similar to results obtained with HDAC6 inhibition, SIRT2 inhibition improved motor function in GlyRSG526R Drosophila, and extended their lifespan (Zhao et al., 2021). Together, these results provide compelling evidence that axonal transport deficits arising from increased α-tubulin deacetylation contribute to the pathophysiology of certain forms of CMT2D, and that the deacetylases HDAC6 and SIRT2 may be actionable therapeutic targets.

An important task for future studies will be to determine the extent to which axonal transport defects generalize across CMT-associated GlyRS variants, and more broadly to other neuropathies caused by ARS1 mutations. In contrast to previous studies, a recent study failed to detect the defects in retrograde axonal transport of signaling endosomes in the DRGs of early symptomatic Gars1C201R/+ mice (Sleigh et al., 2020b). Numerous possible explanations for this discrepancy were discussed by the authors, including measurement of different cellular cargoes between studies, and analysis of cells cultured from mice at different stages of the disease. Nevertheless, this apparent inconsistency warrants further investigation, and the use of intravital imaging techniques would circumvent some of the inherent shortcomings of in vitro and ex vivo assays (Sleigh et al., 2017c).

The established CMT2D animal models have also provided evidence that CMT2D-associated GlyRS mutations impair protein synthesis through mechanisms indirectly related to defective tRNA charging. Neurons are particularly vulnerable to disrupted protein synthesis, with inhibition of protein synthesis being sufficient to induce a neuropathy phenotype (Chihara et al., 2007; Malissovas et al., 2016). Ubiquitous overexpression of the G240R and G526R GlyRS variants in adult Drosophila reduced the rate of protein synthesis in both motor and sensory neurons (Niehues et al., 2015), and translation was similarly impaired in motor neurons of Gars1P278KY/+ and Gars1C201R/+ mice (Spaulding et al., 2021). This impairment in protein synthesis is caused by sequestration of tRNAGly by mutant GlyRS, with overexpression of tRNAGly rescuing peripheral neuropathy in multiple Drosophila and mouse CMT2D models (Zuko et al., 2021).

The sequestration of tRNAGly directly impacts the elongation stage of protein synthesis and has a secondary effect on the initiation of translation, through activation of the integrated stress response (ISR) (Mendonsa et al., 2021). The absence of tRNAGly at the ribosome during translation causes stalling of the ribosome at glycine codons. Within alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord, as well as in a subset of sensory neurons, pausing of the ribosome induces phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2a) by the sensor kinase general control nondepressible 2 (GCN2), triggering the ISR (Mendonsa et al., 2021; Spaulding et al., 2021). Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of GCN2 prevents ISR activation and improves both sensory and motor function in CMT2D mice (Spaulding et al., 2021). The precise link between induction of the ISR and neuropathy remains unclear, as does the specificity of the cell populations affected, however, the phenotypic improvement in CMT2D mice following GCN2 inhibition suggests that this may be an effective treatment target (Spaulding et al., 2021).

Neurotrophin 3 (NT-3) gene therapy has been employed to improve the phenotype of CMT2D mice (Ozes et al., 2021). NT-3, through TrkC signaling, supports several aspects of nervous system development and function, including Schwann cell migration, peripheral neurite outgrowth, and development of the NMJ (Yamauchi et al., 2004; Sheard et al., 2010). Intramuscular delivery of NT-3 has previously been shown to alleviate neuropathy in mouse models of CMT type I (Sahenk et al., 2014). AAV1-mediated delivery of NT-3 (AAV1.NT-3) into the gastrocnemius muscles of post-symptomatic Gars1P278KY/+ mice led to improvements in motor performance, increased CMAP, increased myelin thickness, and improved NCV (Ozes et al., 2021). Additionally, NMJ denervation was reduced and mitochondrial abnormalities in the muscles of Gars1P278KY/+ mice were corrected following AAV1.NT-3 treatment. Improvements were less pronounced in Gars1delETAQ/huEx8 mice, possibly due to their milder phenotype, or due to treatment at a later timepoint (Ozes et al., 2021).

Mutations in the cytosolic tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) gene YARS1 are associated with dominant-intermediate CMT type C (DI-CMTC). The age of onset for DI-CMTC is highly variable, with reports ranging between 5 and 60 years of age (Jordanova et al., 2006; Hyun et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2016). Patients typically present with slowly progressive, mild-to-moderate motor and sensory deficits, including distal muscle weakness and atrophy, as well as impaired sensation of vibration and pinprick stimuli. The motor symptoms are generally more pronounced than the sensory impairments. Most DI-CMTC patients have abnormal MNCVs, with reported median MNCVs widely ranging between 25 and 58 m/s. The underlying cause of MNCV slowing in DI-CMTC patients is yet to be determined, with some evidence of both axonal loss and demyelination observed in patient nerve biopsies (Thomas et al., 2016).

As was the case for GlyRS, 50% loss of TyrRS activity does not produce a neuropathy phenotype in either Drosophila or mice (Storkebaum et al., 2009; Hines et al., 2021). YARS1 variants have varied impacts on the efficiency of the aminoacylation reaction itself. For example, whilst the YARS1G41R patient variant reduces the tRNATyr aminoacylation rate by 34% (Jordanova et al., 2006), the YARS1E196K patient variant has a comparable rate of aminoacylation to the wildtype enzyme, despite causing a severe motor phenotype when overexpressed in Drosophila (Storkebaum et al., 2009; Froelich and First, 2011). Both variants are capable of dimerizing with wildtype TyrRS, and results from a yeast complementation assay suggest that the TyrRS mutants may exert a dominant-negative effect on the wildtype enzyme function (Jordanova et al., 2006).

GlyRS and TyrRS both show distinctive subcellular localization patterns within peripheral axons and Schwann cells, possibly reflecting localized demands for protein synthesis, or secondary enzyme functions specific to these locations (Jordanova et al., 2006; Stum et al., 2011). In vitro, wildtype TyrRS is located in granular structures concentrated within the outgrowing axon terminals of differentiating mouse N2a and human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines, whereas mutant (p.Gly41Arg and p.Glu196Lys) TyrRS shows a homogenous, non-granular distribution pattern (Jordanova et al., 2006). Despite this in vitro result, mislocalisation of mutant TyrRS was not observed in a Drosophila model of DI-CMTC (Niehues et al., 2015).

Like CMT2D-associated GlyRS mutations, DI-CMTC mutations can induce conformational changes in TyrRS, which expose previously hidden surfaces of the enzyme, enabling novel interactions with other proteins to take place (Blocquel et al., 2017). DI-CMTC linked YARS1 variants (YARS1G41R, YARS1E196K, and YARS1del153–156) sequester tripartite motif-containing 28 (TRIM28), leading to hyperactivation of the transcription factor E2F1 in mammalian cells (Blocquel et al., 2017; Bervoets et al., 2019). Transcriptomic analyses of a DI-CMTC Drosophila model also suggest that abnormal interactions occur between mutant TyrRS and multiple transcription factors within the nucleus (Bervoets et al., 2019). The transcriptional dysregulation caused by these interactions have been shown to contribute to the DI-CMTC phenotype in Drosophila.

The Drosophila homolog of YARS1 (TyrRS) is 68% identical to the human gene, and wildtype human TyrRS can compensate for loss of Drosophila TyrRS, indicating functional conservation between species (Storkebaum et al., 2009). Ubiquitous expression of a non-pathogenic TyrRS variant (p.Lys256Asp) in Drosophila does not produce an abnormal phenotype, whereas expression of neuropathy-linked TyrRS variants in Drosophila cause dose-dependent toxicity, with strong ubiquitous expression of DI-CMTC variants leading to developmental lethality (Storkebaum et al., 2009; Leitão-Gonçalves et al., 2012).

Selective expression of pathogenic TyrRS variants in neurons is sufficient to cause a DI-CMTC phenotype including progressive motor dysfunction with no signs of degeneration in the brain or ventral nerve cord (Storkebaum et al., 2009). Interestingly, in contrast to the Drosophila models of CMT2D discussed previously, conditional expression of DI-CMTC variants in muscle does not produce a disease phenotype, suggesting that the motor dysfunction in the DI-CMTC model originates in neuronal cells. Expression of DI-CMTC variants within the GF circuit impairs synaptic transmission between the GF and the tergotrochanteral motoneuron (TTMn), and causes thinning and progressive degeneration of the GF axon terminal (Storkebaum et al., 2009). Selective presynaptic, but not postsynaptic expression of the TyrRS variants reproduced these defects. DI-CMTC Drosophila also show distinct morphological abnormalities in their eyes, wings, and bristles, which are unrelated to the clinical phenotype but are nonetheless useful markers of cellular dysfunction (Storkebaum et al., 2009).

A mammalian model of DI-CMTC has been generated through expression of the patient variant p.Glu196Lys in mice (Yars1E196K) (Hines et al., 2021; Spaulding et al., 2021). Homozygous Yars1E196K/E196K mice exhibit a pronounced neuropathy phenotype, with increasingly impaired performance in the wire hang test from 2 months of age and significantly reduced sciatic NCV from 4 months of age. In contrast, heterozygous Yars1E196K/+ mice do not develop an overt neuropathy phenotype, indicating that expression of this variant is better tolerated in mice than in humans. Interestingly, a similar species difference in phenotype severity has also been observed in knock-in mouse models for recessive ARS disease (Fröhlich et al., 2020; Klugmann et al., 2022). No defects in myelination were observed in homozygous or heterozygous Yars1E196K mice, however, Yars1E196K/E196K mice showed a non-progressive decrease in peripheral motor axon diameter compared to wildtype mice at 4 months of age (Hines et al., 2021). Expression of the Yars1E196K allele in combination with a Yars1 null allele (Yars1E196K/−) produced a similar phenotype to Yars1E196K/E196K, with an additional characteristic of weight loss.

DI-CMTC-associated TyrRS variants can cause transcriptional dysregulation through novel interactions with transcription factors in the nucleus. In both DI-CMTC patient cells and in Drosophila, the transcription factor E2F1 is hyperactivated in the presence of mutant TyrRS (Bervoets et al., 2019). Inhibition of E2F1 improved developmental survival rates of Drosophila expressing YARS1E196K but was not sufficient to rescue the motor defects. Excluding TyrRS from the nucleus prevented the DI-CMT phenotype in YARS1E196K expressing Drosophila and normalized their gene expression profile, suggesting that aberrant interactions between mutant TyrRS and transcription factors within the nucleus are likely triggering the DI-CMTC pathophysiology (Bervoets et al., 2019). Given that other cytosolic ARSs have also been found within the nucleus, it will be of interest to determine whether transcription is similarly dysregulated when these are mutated.

Furthermore, reduced rates of protein synthesis have been observed in Drosophila DI-CMTC models, mirroring results obtained from Drosophila models of CMT2D (Niehues et al., 2015). Additionally, as for CMT2D mice, activation of the ISR was detected in homozygous Yars1E196K mice, however the therapeutic benefit of GCN2 inhibition is yet to be tested in this model (Spaulding et al., 2021).

Dominant mutations in HARS1, the gene encoding the cytosolic histidyl-tRNA synthetase (HisRS), have predominantly been associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2W (CMT2W) and hereditary motor neuropathy (HMN), with both disease presentations sometimes occurring within the same family (Safka Brozkova et al., 2015). As with mutations in the other ARS1 genes, disease severity is highly variable between individuals. Additionally, there has been one report of a patient presenting with peripheral neuropathy, accompanied by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive intra-axonal inclusions and cerebellar atrophy (Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019). However, since this is so far an isolated case, it is not clear whether these symptoms were caused by an additional genetic factor or whether they occurred as a direct consequence of the HARS1 mutation (Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019).

All disease-causing dominant HARS1 mutations are located within the catalytic domain of HisRS and have each shown loss-of-function characteristics in vitro. For several pathogenic HisRS variants, the reduced rate of aminoacylation is attributable to an elevated Michaelis constant (KM) for binding ATP and histidine, indicating impairment of the mutant enzymes to recognize these substrates (Abbott et al., 2018). Despite the apparent loss of canonical enzyme function, neither the inability of mutant HisRS to support yeast growth in a yeast complementation assay, nor the decrease of aminoacylation activity within patient cells correlate with disease severity (Safka Brozkova et al., 2015; Blocquel et al., 2019). Localization of CMT2W-associated HARS1 mutants is normal within differentiated rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells and C. elegans motor neurons, respectively (Vester et al., 2013; Mullen et al., 2021). Dimerization of the mutant enzymes also appears unaffected (Abbott et al., 2018; Mullen et al., 2021). Consistent with the tissue-specific disease phenotype, HisRS mutants have cell type-specific impacts on protein synthesis in vitro. While protein synthesis was unchanged in fibroblasts from a CMT2W patient, expression of CMT2W HARS1 mutants in PC12 cells impaired protein synthesis and induced the ISR, causing impaired neurite outgrowth (Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019; Mullen et al., 2021).

Studies conducted in vivo have further confirmed the neurotoxicity of CMT-causing HisRS variants and highlighted the sensitivity of the nervous system to deficiencies in protein synthesis that may arise from these mutations. In C. elegans, overexpression of CMT2W hars-1 variants in GABAergic motor neurons is neurotoxic, causing progressive morphological defects in axons and concomitant locomotor deficits (Vester et al., 2013; Safka Brozkova et al., 2015). Similarly, ubiquitous overexpression of CMT HisRS variants in zebrafish disrupts axonal morphology, causing shortening and disorganization of DRG projections as well as an abnormal motor phenotype (Mullen et al., 2021). So far, no mammalian models of CMT2W have been described.

Heterozygous Hars1 knockout mice have not been characterized, so HisRS haploinsufficiency cannot yet be ruled out as a cause of CMT2W. Another possibility is that CMT2W-causing HisRS variants exert a dominant-negative effect on the activity of wildtype HisRS, thus lowering tRNAHis aminoacylation below a critical threshold that is required to support normal development and function of peripheral neurons. A dominant-negative effect of mutant HisRS could also possibly compromise non-canonical HisRS functions relevant to supporting peripheral neuron development and function. These hypotheses could be assessed in future in vivo studies by investigating whether the pathological phenotype can be rescued through overexpression of wildtype HisRS, or by disrupting the formation of mutant-wildtype HisRS heterodimers (Meyer-Schuman and Antonellis, 2021).

It is also possible that HARS1 mutations lead to a HisRS conformation change, which could result in aberrant protein interactions, as has been observed with other CMT-ARS1 mutations. Interestingly, an analysis of multiple CMT-associated HARS1 variants revealed that each mutant protein had some degree of conformational opening compared to wildtype HisRS, and that the degree of structural opening correlated with disease severity (Bervoets et al., 2019), however, no specific abnormal protein interactions for mutant HisRS have yet been identified.

Dominant mutations in the cytosolic Alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) gene AARS1 primarily lead to an axonal form of CMT (CMT2N). Neuropathies associated with AARS1 mutations have a highly variable age of onset and clinical severity, with some patients exhibiting reduced NCV diagnosed as DI-CMT. One dominant AARS1 variant has also been linked to dHMN, distinguished from CMT2N by the lack of sensory involvement (Zhao et al., 2012). Another AARS1 variant was found to cause a mild myelopathy in addition to axonal neuropathy (Motley et al., 2015), further expanding the disease spectrum associated with dominant AARS1 mutations.

A dominant mutation in AARS1 has also been linked to the leukoencephalopathy HDLS-S (Sundal et al., 2019). HDLS-S presents in adulthood and has a rapid and severe degenerative course, with a median life expectancy of less than 10 years following disease onset. Unlike CMT2N, HDLS-S patients do not show any signs of peripheral axonal degeneration, suggesting that the underlying pathomechanism is different. The responsible AARS1 mutation is located within the aminoacylation domain, and while AlaRS expression levels are unaffected, protein function has not yet been assessed for this variant.

Animal models for neuropathy causing AlaRS variants are sparse, with only a single study in zebrafish conducted to date (Weterman et al., 2018). Several in vitro studies have provided intriguing results that should be followed up in vivo. These key findings are briefly discussed in the following sections.

The AlaRS protein structure comprises an aminoacylation domain, an editing domain, and the C-terminal domain (C-Ala). AlaRS functions as a monomer in human cells, however, the protein is capable of dimerization, possibly to facilitate non-canonical activities (Sun et al., 2016). In humans, the C-Ala domain is not required for aminoacylation but has been shown to bind DNA within the nucleus and to mediate AlaRS dimerization, suggesting that it is involved in the functional expansion of this enzyme (Sun et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021a).

Neuropathy-causing AARS1 mutations have been identified in each of the AlaRS domains. Consistent with other ARS1 variants linked to CMT disease, the occurrence of neuropathy appears to be uncoupled from loss of aminoacylation function (Sun et al., 2021). This was further demonstrated in a zebrafish study, where the expression of either hypomorphic or hypermorphic CMT2N-causing AARS1 variants in 1-cell stage embryos caused severely abnormal embryonic development and aberrant peripheral nerve patterns (Weterman et al., 2018). The AARS1 mutation most commonly linked to CMT (p.Arg329His; AARS1R329H) is located within the AlaRS aminoacylation domain but does not impair its canonical function (Sun et al., 2021). While localization of mutant AARS1E778A appears normal within MN-1 cells (McLaughlin et al., 2012), the AARS1R329H variant exhibits abnormal, punctate co-localization with Golgi bodies and lysosomes in COS-7 fibroblasts, and has an inhibitory effect on neuronal cell differentiation and process outgrowth in N1E-15 cells (Imaizumi et al., 2019). Another AlaRS variant with a mutation in the aminoacylation domain (p.Asn71Tyr) caused similar localization defects and inhibition of neurite outgrowth in vitro, which could be prevented through pre-treatment with the antiepileptic drug valproic acid (Tatsumi et al., 2019). Whether these variants cause localization defects in vivo is yet to be investigated.

AARS1 variants that cause neuropathy do not affect proofreading in vitro, including mutations located within the AlaRS editing domain (Sun et al., 2021). Furthermore, mice homozygous for editing-defective AlaRS alleles exhibit ataxia due to loss of cerebellar Purkinje neurons, but do not develop a neuropathy phenotype (Lee et al., 2006; Stum et al., 2011), suggesting that tRNA mischarging is not the underlying cause of peripheral neuropathies associated with dominant ARS mutations.

Intriguingly, one in vitro study found that all mutations located within the AlaRS aminoacylation domain induced a conformational opening in the protein, which led to an aberrant interaction with Nrp1 (Sun et al., 2021), mirroring the interactions previously identified between mutant GlyRS and Nrp1 (He et al., 2015; Mo et al., 2018). However, in contrast to GlyRS and TyrRS mutants, these AlaRS variants did not interact with HDAC6 or TRIM28. An editing domain mutation investigated in the same study (p.Glu688Gly) induced a different conformational opening in AlaRS, which did not enable binding of Nrp1 but might lead to novel, toxic interactions with other proteins. Hence, despite the shared interactions between Nrp1 and specific AlaRS and GlyRS variants, there is a clear heterogeneity in the downstream consequences of neuropathy associated ARS1 mutations, even among mutations in the same gene. Future studies using animal models are required to establish whether the Nrp1-AlaRS interaction occurs in vivo and how this interaction contributes to the neuropathy phenotype.

Mutations in the WARS1 gene, which encodes the tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS), have been linked to autosomal dominant dHMN (Tsai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Typically, symptoms emerge during adolescence or early adulthood, primarily affecting the distal lower limb muscles, sometimes followed by upper limb involvement. WARS1 variants may also cause CMT neuropathy, as a number of patients harboring the p.Asp341Gly mutation have been reported to have mild sensory deficits (Wang et al., 2019), however, in the small number of cases identified so far, the pathology seems most severe in motor axons.

There are currently no published studies on the effects of pathogenic WARS1 mutations in vivo. Both dHMN-linked WARS1 mutations described in the literature (p.His257Arg and p.Asp341Gly) occur in highly conserved residues of the TrpRS protein. The p.His257Arg mutation exerts a dominant-negative effect on TrpRS aminoacylation activity and on overall protein synthesis in vitro (Tsai et al., 2017). Expression of WARS1H257R in both mouse and human neuronal cell lines impaired neurite outgrowth and caused neurite degeneration (Tsai et al., 2017), consistent with effects observed with other pathogenic ARS1 mutations.

Similar to what has been discovered for GlyRS and TyrRS, pathogenic mutations in TrpRS appear to modulate its interactions with other proteins. TrpRS is known to be involved in angiostasis, and the p.His257Arg variant increases the angiostatic activity of the protein by enhancing the interaction between TrpRS and VE-cadherin (Tsai et al., 2017). In vivo experiments may help to determine whether the TrpRS-VE-cadherin interaction contributes to the dHMN phenotype, and hence whether this represents a potential treatment target. It is also possible that neuropathy associated WARS1 variants cause additional aberrant protein interactions, which may disrupt other cellular processes.

Mutations in MARS1, the cytosolic methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetRS) gene are associated with CMT type 2U (CMT2U) (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Hyun et al., 2014; Hirano et al., 2016; Nam et al., 2016; Sagi-Dain et al., 2018; Gillespie et al., 2019). CMT2U patients present with progressive motor deficits that are most pronounced in the lower limbs, often accompanied by decreased sensation in the lower extremities. NCV results are typically consistent with axonal neuropathy, however, peripheral nerve demyelination has also been observed in some individuals (Hirano et al., 2016; Sagi-Dain et al., 2018). The age of onset for CMT2U varies significantly, ranging from early childhood to late adulthood. Disease severity is similarly heterogeneous, even among family members expressing the same variant (Sagi-Dain et al., 2018). Interestingly, the first MARS1 variant associated with CMT2U (p.Arg618Cys) appeared to have incomplete penetrance (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Rips et al., 2018). However, given the very late disease onset of some patients, it is possible that family members unaffected at the time of testing developed disease later in life.

The MARS1 variants that have so far been linked to neuropathy occur in highly conserved residues of the protein. In vitro and in vivo characterization of MARS1 variants are limited, with no animal models for CMT2U currently available. MARS1 variants that have been evaluated in yeast complementation assays have shown reduced capacity to support yeast growth, consistent with loss of enzyme function (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Rips et al., 2018; Gillespie et al., 2019). In silico modeling of the p.Arg618Cys variant suggested that this mutation induces a structural opening in the protein (Gonzalez et al., 2013), possibly enabling novel protein interactions to take place, as has been observed for other neuropathy-causing ARS1 variants.

Recently, 16 patients with CMT from three unrelated families were identified with heterozygous mutations in SARS1, the gene encoding cytosolic seryl-tRNA synthetase (He et al., 2023). Patients exhibited progressive muscle weakness and atrophy in their limbs, sensory loss, and NCVs consistent with an intermediate form of CMT. The two pathogenic mutations identified in this cohort occur in highly conserved residues within the aminoacylation domain of SerRS, and result in significantly reduced aminoacylation activity in vitro. Both mutant proteins showed increased dimerization with wildtype SerRS. Interestingly, eIF2a phosphorylation was elevated in fibroblasts and N2a cells co-transfected with mutant and wildtype SerRS, but not in cells transfected with mutant SerRS alone (He et al., 2023), suggesting that the formation of mutant-wildtype SerRS heterodimers is pathogenic. Once in vivo models of SerRS-linked CMT are established, it will be of interest to determine whether disrupting the dimerization capability of mutant SerRS provides any phenotypic improvement.

Many in vivo models for ARS1-associated neuropathies have been generated through knock-in or overexpression of pathogenic ARS1 alleles in multiple species including Drosophila, zebrafish, and mice. Where tested, heterozygous knockout of ARS1 genes in mice has not produced a neuropathy phenotype, implying that these disorders are not caused by haploinsufficiency. The majority of animal models for dominant ARS1 diseases have focused on GlyRS and TyrRS variants, however, results from these studies provide a valuable starting point for investigating the pathophysiology underlying neuropathies caused by mutations in the other ARS1 genes. It is important to note that introducing neuropathy associated ARS1 mutations into a model organism might not always accurately capture the human disease spectrum due to interspecies differences including variations in ARS protein structure, splicing, and signaling pathways. Therefore, supplementing data obtained from animal studies with alternative approaches such as patient-derived iPSC disease models will increase their translational relevance.

Existing in vivo models have linked the expression of pathogenic ARS1 variants to defects in the early development of the peripheral nervous system, synaptic transmission deficits at the NMJ, and progressive NMJ denervation. Novel toxic protein interactions have been uncovered for a variety of neuropathy associated ARS1 variants, which directly contribute to the disease pathogenesis, and therefore represent actionable therapeutic targets. In vivo studies have additionally demonstrated the vulnerability of peripheral nervous system development and function to disturbances in protein synthesis, which can arise from compromised ARS function. Individual ARS1 variants differ greatly in the extent of their loss-of-function, as well as in their interactions with other proteins. Different cellular pathways are perturbed across ARS1 variants, likely contributing to the great heterogeneity amongst patients and necessitating the development of personalized medicine and tailored treatment strategies. It will therefore be imperative for future studies to characterize the downstream consequences of other pathogenic ARS1 variants in vivo, to guide the selection of appropriate treatment strategies for individual patients.

EK and DF led the project and the manuscript production. MK and GH contributed to the manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was funded by the European Leukodystrophy Association (ELA 2018-014I2) and the Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund (Leukodystrophy Flagship – Massimo’s Mission; MRFF-ARLKO). EK was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

MK was employed by the company Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG.

The remaining authors declare that this literature review was produced in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbott, J. A., Meyer-Schuman, R., Lupo, V., Feely, S., Mademan, I., Oprescu, S. N., et al. (2018). Substrate interaction defects in histidyl-tRNA synthetase linked to dominant axonal peripheral neuropathy. Hum. Mutat. 39, 415–432. doi: 10.1002/humu.23380

Abe, A., and Hayasaka, K. (2009). The GARS gene is rarely mutated in Japanese patients with Charcot-Marie-tooth neuropathy. J. Hum. Genet. 54, 310–312. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.25

Achilli, F., Bros-Facer, V., Williams, H. P., Banks, G. T., AlQatari, M., Chia, R., et al. (2009). An ENU-induced mutation in mouse glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) causes peripheral sensory and motor phenotypes creating a model of Charcot-Marie-tooth type 2D peripheral neuropathy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2, 359–373. doi: 10.1242/dmm.002527

Antonellis, A., Ellsworth, R. E., Sambuughin, N., Puls, I., Abel, A., Lee-Lin, S. Q., et al. (2003). Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1293–1299. doi: 10.1086/375039

Antonellis, A., Lee-Lin, S. Q., Wasterlain, A., Leo, P., Quezado, M., Goldfarb, L. G., et al. (2006). Functional analyses of glycyl-tRNA synthetase mutations suggest a key role for tRNA-charging enzymes in peripheral axons. J. Neurosci. 26, 10397–10406. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1671-06.2006

Arif, A., Terenzi, F., Potdar, A. A., Jia, J., Sacks, J., China, A., et al. (2017). EPRS is a critical mTORC1-S6K1 effector that influences adiposity in mice. Nature 542, 357–361. doi: 10.1038/nature21380

Bais, P., Beebe, K., Morelli, K. H., Currie, M. E., Norberg, S. N., Evsikov, A. V., et al. (2016). Metabolite profile of a mouse model of Charcot-Marie-tooth type 2D neuropathy: implications for disease mechanisms and interventions. Biol. Open 5, 908–920. doi: 10.1242/bio.019273

Bansagi, B., Antoniadi, T., Burton-Jones, S., Murphy, S. M., McHugh, J., Alexander, M., et al. (2015). Genotype/phenotype correlations in AARS-related neuropathy in a cohort of patients from the United Kingdom and Ireland. J. Neurol. 262, 1899–1908. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7778-4

Benoy, V., Van Helleputte, L., Prior, R., d'Ydewalle, C., Haeck, W., Geens, N., et al. (2018). HDAC6 is a therapeutic target in mutant GARS-induced Charcot-Marie-tooth disease. Brain 141, 673–687. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx375

Bervoets, S., Wei, N., Erfurth, M. L., Yusein-Myashkova, S., Ermanoska, B., Mateiu, L., et al. (2019). Transcriptional dysregulation by a nucleus-localized aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase associated with Charcot-Marie-tooth neuropathy. Nat. Commun. 10:5045. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12909-9

Blocquel, D., Li, S., Wei, N., Daub, H., Sajish, M., Erfurth, M. L., et al. (2017). Alternative stable conformation capable of protein misinteraction links tRNA synthetase to peripheral neuropathy. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 8091–8104. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx455

Blocquel, D., Sun, L., Matuszek, Z., Li, S., Weber, T., Kuhle, B., et al. (2019). CMT disease severity correlates with mutation-induced open conformation of histidyl-tRNA synthetase, not aminoacylation loss, in patient cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 19440–19448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908288116

Boczonadi, V., Meyer, K., Gonczarowska-Jorge, H., Griffin, H., Roos, A., Bartsakoulia, M., et al. (2018). Mutations in glycyl-tRNA synthetase impair mitochondrial metabolism in neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 2187–2204. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy127

Cader, M. Z., Ren, J., James, P. A., Bird, L. E., Talbot, K., and Stammers, D. K. (2007). Crystal structure of human wildtype and S581L-mutant glycyl-tRNA synthetase, an enzyme underlying distal spinal muscular atrophy. FEBS Lett. 581, 2959–2964. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.046

Chihara, T., Luginbuhl, D., and Luo, L. (2007). Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial protein translation in axonal and dendritic terminal arborization. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 828–837. doi: 10.1038/nn1910

Chung, P., Northrup, H., Azmath, M., Mosquera, R. A., Moody, S., and Yadav, A. (2018). Glycyl tRNA Synthetase (GARS) gene variant causes distal hereditary motor neuropathy V. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2018:8516285. doi: 10.1155/2018/8516285

Corcia, P., Brulard, C., Beltran, S., Marouillat, S., Bakkouche, S. E., Andres, C. R., et al. (2019). Typical bulbar ALS can be linked to GARS mutation. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 20, 275–277. doi: 10.1080/21678421.2018.1556699

Del Bo, R., Locatelli, F., Corti, S., Scarlato, M., Ghezzi, S., Prelle, A., et al. (2006). Coexistence of CMT-2D and distal SMA-V phenotypes in an Italian family with a GARS gene mutation. Neurology 66, 752–754. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201275.18875.ac

Dickinson, M. E., Flenniken, A. M., Ji, X., Teboul, L., Wong, M. D., White, J. K., et al. (2016). High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes. Nature 537, 508–514. doi: 10.1038/nature19356

Dubourg, O., Azzedine, H., Yaou, R. B., Pouget, J., Barois, A., Meininger, V., et al. (2006). The G526R glycyl-tRNA synthetase gene mutation in distal hereditary motor neuropathy type V. Neurology 66, 1721–1726. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218304.02715.04

English, K., and Barton, M. C. (2021). HDAC6: a key link between mitochondria and development of peripheral neuropathy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14:684714. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.684714

Ermanoska, B., Motley, W. W., Leitao-Goncalves, R., Asselbergh, B., Lee, L. H., De Rijk, P., et al. (2014). CMT-associated mutations in glycyl-and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases exhibit similar pattern of toxicity and share common genetic modifiers in Drosophila. Neurobiol. Dis. 68, 180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.04.020

Eskuri, J. M., Stanley, C. M., Moore, S. A., and Mathews, K. D. (2012). Infantile onset CMT2D/dSMA V in monozygotic twins due to a mutation in the anticodon-binding domain of GARS. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 17, 132–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00370.x

Froelich, C. A., and First, E. A. (2011). Dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-tooth disorder is not due to a catalytic defect in tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 50, 7132–7145. doi: 10.1021/bi200989h

Fröhlich, D., Mendes, M. I., Kueh, A. J., Bongers, A., Herold, M. J., Salomons, G. S., et al. (2020). A Hypomorphic Dars1 (D367Y) model recapitulates key aspects of the leukodystrophy HBSL. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14:625879. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.625879

Fröhlich, D., Suchowerska, A. K., Spencer, Z. H., von Jonquieres, G., Klugmann, C. B., Bongers, A., et al. (2017). In vivocharacterization of the aspartyl-tRNA synthetase DARS: homing in on the leukodystrophy HBSL. Neurobiol. Dis. 97, 24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.10.008

Fröhlich, D., Suchowerska, A. K., Voss, C., He, R., Wolvetang, E., von Jonquieres, G., et al. (2018). Expression pattern of the aspartyl-tRNA Synthetase DARS in the human brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:81. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00081

Fuchs, S. A., Schene, I. F., Kok, G., Jansen, J. M., Nikkels, P. G. J., van Gassen, K. L. I., et al. (2019). Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase deficiencies in search of common themes. Genet. Med. 21, 319–330. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0048-y

Galatolo, D., Kuo, M. E., Mullen, P., Meyer-Schuman, R., Doccini, S., Battini, R., et al. (2020). Bi-allelic mutations in HARS1 severely impair histidyl-tRNA synthetase expression and enzymatic activity causing a novel multisystem ataxic syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 41, 1232–1237. doi: 10.1002/humu.24024

Gillespie, M. K., McMillan, H. J., Kernohan, K. D., Pena, I. A., Meyer-Schuman, R., Antonellis, A., et al. (2019). A novel mutation in MARS in a patient with Charcot-Marie-tooth disease, axonal, type 2U with congenital onset. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 6, 333–339. doi: 10.3233/jnd-190404

Gonzaga-Jauregui, C., Harel, T., Gambin, T., Kousi, M., Griffin, L. B., Francescatto, L., et al. (2015). Exome sequence analysis suggests that genetic burden contributes to phenotypic variability and complex neuropathy. Cell Rep. 12, 1169–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.023

Gonzalez, M., McLaughlin, H., Houlden, H., Guo, M., Yo-Tsen, L., Hadjivassilious, M., et al. (2013). Exome sequencing identifies a significant variant in methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MARS) in a family with late-onset CMT2. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 1247–1249. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305049

Grice, S. J., Sleigh, J. N., Motley, W. W., Liu, J. L., Burgess, R. W., Talbot, K., et al. (2015). Dominant, toxic gain-of-function mutations in gars lead to non-cell autonomous neuropathology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 4397–4406. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv176

Grice, S. J., Sleigh, J. N., and Zameel Cader, M. (2018). Plexin-semaphorin signaling modifies neuromuscular defects in a Drosophila model of peripheral neuropathy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:55. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00055

Griffin, L. B., Sakaguchi, R., McGuigan, D., Gonzalez, M. A., Searby, C., Züchner, S., et al. (2014). Impaired function is a common feature of neuropathy-associated glycyl-tRNA synthetase mutations. Hum. Mutat. 35, 1363–1371. doi: 10.1002/humu.22681

Gu, C., Rodriguez, E. R., Reimert, D. V., Shu, T., Fritzsch, B., Richards, L. J., et al. (2003). Neuropilin-1 conveys semaphorin and VEGF signaling during neural and cardiovascular development. Dev. Cell 5, 45–57. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00169-2

Guo, M., and Schimmel, P. (2013). Essential nontranslational functions of tRNA synthetases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 145–153. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1158

Gutmann, L., and Shy, M. (2015). Update on Charcot-Marie-tooth disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 28, 462–467. doi: 10.1097/wco.0000000000000237

Hamaguchi, A., Ishida, C., Iwasa, K., Abe, A., and Yamada, M. (2010). Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type 2D with a novel glycyl-tRNA synthetase gene (GARS) mutation. J. Neurol. 257, 1202–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5491-x

He, W., Bai, G., Zhou, H., Wei, N., White, N. M., Lauer, J., et al. (2015). CMT2D neuropathy is linked to the neomorphic binding activity of glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Nature 526, 710–714. doi: 10.1038/nature15510

He, J., Liu, X. X., Ma, M. M., Lin, J. J., Fu, J., Chen, Y. K., et al. (2022). Heterozygous seryl-tRNA synthetase 1 variants cause Charcot-Marie-tooth disease. Ann. Neurol. 93, 244–256. doi: 10.1002/ana.26501

He, J., Liu, X. X., Ma, M. M., Lin, J. J., Fu, J., Chen, Y. K., et al. (2023). Heterozygous Seryl-tRNA synthetase 1 variants cause Charcot-Marie-tooth disease. Ann. Neurol. 93, 244–256. doi: 10.1002/ana.26501

He, W., Zhang, H. M., Chong, Y. E., Guo, M., Marshall, A. G., and Yang, X. L. (2011). Dispersed disease-causing neomorphic mutations on a single protein promote the same localized conformational opening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 12307–12312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104293108

Hines, T. J., Tadenev, A. L. D., Lone, M. A., Hatton, C. L., Bagasrawala, I., Stum, M. G., et al. (2021). Precision mouse models of Yars/dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type C and Sptlc1/hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type 1. J. Anat. 241, 1169–1185. doi: 10.1111/joa.13605

Hirano, M., Oka, N., Hashiguchi, A., Ueno, S., Sakamoto, H., Takashima, H., et al. (2016). Histopathological features of a patient with Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type 2U/AD-CMTax-MARS. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 21, 370–374. doi: 10.1111/jns.12193

Høyer, H., Busk, Ø. L., Esbensen, Q. Y., Røsby, O., Hilmarsen, H. T., Russell, M. B., et al. (2022). Clinical characteristics and proteome modifications in two Charcot-Marie-tooth families with the AARS1 Arg326Trp mutation. BMC Neurol. 22:299. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-02828-6

Hsu, Y. H., Lin, K. P., Guo, Y. C., Tsai, Y. S., Liao, Y. C., and Lee, Y. C. (2019). Mutation spectrum of Charcot-Marie-tooth disease among the Han Chinese in Taiwan. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 6, 1090–1101. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50797

Huang, Y., Bi, B., Zhao, P., Yu, T., Luo, S., Tan, L., et al. (2022). Infantile-onset CMT2D/dSMA-V in a Chinese family with parental germline mosaicism for a novel mutation in the GARS1 gene. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 10:e1846. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1846

Huang, E. J., and Reichardt, L. F. (2003). Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 609–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629

Huang, H., Zhang, Y., Yang, M., Lian, B., Guo, R., and Cao, L. (2022). Case report: early-onset Charcot-Marie-tooth 2N with reversible White matter lesions repeatedly mimicked stroke or encephalitis. Front. Pediatr. 10:935721. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.935721

Hyun, Y. S., Park, H. J., Heo, S. H., Yoon, B. R., Nam, S. H., Kim, S. B., et al. (2014). Rare variants in methionyl-and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase genes in late-onset autosomal dominant Charcot-Marie-tooth neuropathy. Clin. Genet. 86, 592–594. doi: 10.1111/cge.12327

Imaizumi, N., Takeuchi, Y., Hirano, H., Torii, T., Seki, Y., Morimoto, T., et al. (2019). Data on the effects of Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type 2N-associated AARS missense mutation (Arg329-to-his) on the cell biological properties. Data Brief. 25:104029. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.104029

James, P. A., Cader, M. Z., Muntoni, F., Childs, A. M., Crow, Y. J., and Talbot, K. (2006). Severe childhood SMA and axonal CMT due to anticodon binding domain mutations in the GARS gene. Neurology 67, 1710–1712. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242619.52335.bc

Jordanova, A., Irobi, J., Thomas, F. P., Van Dijck, P., Meerschaert, K., Dewil, M., et al. (2006). Disrupted function and axonal distribution of mutant tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase in dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-tooth neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 38, 197–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1727

Kalinski, A. L., Kar, A. N., Craver, J., Tosolini, A. P., Sleigh, J. N., Lee, S. J., et al. (2019). Deacetylation of Miro1 by HDAC6 blocks mitochondrial transport and mediates axon growth inhibition. J. Cell Biol. 218, 1871–1890. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201702187

Kapur, M., and Ackerman, S. L. (2018). mRNA translation gone awry: translation fidelity and neurological disease. Trends Genet. 34, 218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.12.007

Kawakami, N., Komatsu, K., Yamashita, H., Uemura, K., Oka, N., Takashima, H., et al. (2014). A novel mutation in glycyl-tRNA synthetase caused Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type 2D with facial and respiratory muscle involvement. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 54, 911–915. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.54.911

Klugmann, M., Kalotay, E., Delerue, F., Ittner, L. M., Bongers, A., Yu, J., et al. (2022). Developmental delay and late onset HBSL pathology in hypomorphic Dars1(M256L) mice. Neurochem. Res. 47, 1972–1984. doi: 10.1007/s11064-022-03582-4