95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurosci. , 28 March 2023

Sec. Neuroprosthetics

Volume 17 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1113009

This article is part of the Research Topic Advances in Haptic Feedback for Neurorobotics Applications View all 10 articles

Bone conduction is a promising haptic feedback modality for upper-limb prosthesis users, however, its potential and characteristics as a non-invasive feedback modality have not been thoroughly investigated. This study aimed to establish the temporal and spatial characteristics of non-invasive bone conduction as a sensory feedback interface for upper-limb prostheses. Psychometric human-subject experiments were conducted on three bony landmarks of the elbow, with a vibrotactile transducer affixed to each to provide the stimulus. The study characterized the temporal domain by testing perception threshold and resolution in amplitude and frequency. The spatial domain was evaluated by assessing the ability of subjects to detect the number of simultaneous active stimulation sites. The experiment was conducted with ten able-bodied subjects and compared to two subjects with trans-radial amputation. The psychometric evaluation of the proposed non-invasive bone conduction feedback showed results comparable to invasive methods. The experimental results demonstrated similar amplitude and frequency resolution of the interface for all three stimulation sites for both able-bodied subjects and subjects with trans-radial amputation, highlighting its potential as a non-invasive feedback modality for upper-limb prostheses.

Haptic sensory feedback plays an important role in effective closed-loop control of upper-limb prostheses (Saunders and Vijayakumar, 2011; Antfolk et al., 2013; Markovic et al., 2018; Stephens-Fripp et al., 2018; Farina et al., 2021), promoting the body ownership of prosthetic arm users (Canzoneri et al., 2013; Shehata et al., 2020; Richard et al., 2021) and the reduction of phantom limb pain management (Dietrich et al., 2012). This feedback is generated through a form of stimulation that is encoded with relevant feedback information and delivered to the user's residual limb. The sensory feedback information can be used in a variety of applications including upper-limb prosthesis, e.g., for grasp force control (Childress, 1980; Westling and Johansson, 1984; Augurelle et al., 2003; Antfolk et al., 2013), haptic applications e.g., robotic teleoperation (Dahiya et al., 2010) or virtual reality applications (Richard et al., 2021).

Invasive and non-invasive haptic sensory feedback approaches have been investigated in the past (Cordella et al., 2016; Stephens-Fripp et al., 2018). Invasive approaches, such as implanted nerve electrodes, show great potential but limited applicability or desirability to a subset of the people living with limb loss due to the inherent surgical risks and potential limited lifetime of the electrodes (Schofield et al., 2014; Cordella et al., 2016; Farina and Amsüss, 2016; Svensson et al., 2017). Non-invasive stimulation will therefore continue to play a strong role in prosthetic applications (Farina and Amsüss, 2016). It is also directly applicable in other areas such as in haptics and human robot interaction (Goodrich and Schultz, 2007) and more generally in human machine interfaces (HMI) (Tahir et al., 2018). The state of the arts of non-invasive tactile feedback are conventionally applied on the skin through electrotactile, vibrotactile and mechanotactile modalities to varying degrees of success (Antfolk et al., 2013; Schofield et al., 2014; Sensinger and Dosen, 2020; Farina et al., 2021). The shortcomings of these methods were comprehensively studied and summarized in two thorough review papers (Svensson et al., 2017; Stephens-Fripp et al., 2018). These shortcomings include: (1) The force dependency of perceived sensation in vibrotactile feedback, which can affect the accuracy and consistency of feedback information when the transducer is pressed against the skin; (2) Changes in the perception of both electrotactile and vibrotactile stimulation on the skin with varying locations, making it difficult to achieve precise and reliable feedback; (3) The bulky and high power consumption setup of the mechanotactile feedback, which can limit its practicality in real-world applications.

This paper focuses on the investigation of a non-invasive bone conduction modality as an interface to convey information to the human user. Bone conduction is a method of providing vibrotactile feedback through the bone. This approach relies on the transmission of vibrations/sound through the bone, which stimulates the Pacinian Corpuscles located around the bone (Clemente et al., 2017). Bone conduction is a relatively recent and emerging modality which can potentially address the aforementioned shortcomings.

The potential of bone conduction as a haptic feedback interface for upper-limb prosthesis has been studied in Clemente et al. (2017) through mechanical stimulation of a bone-anchored (osseointegrated) prosthesis. Superior bandwidth compared to vibrotactile feedback on the skin was found in Clemente et al. (2017) for invasive bone conduction. This allows for richer feedback of sensory information to the human user.

While the results of the osseoperception using bone conduction were promising, it is only applicable for users with osseointegrated upper-limb prostheses. There are cases that osseointegration is not suited for people with upper-limb loss due to the lack of length or strength in the residual limb or the inherent surgical risks of the invasive technique (Schofield et al., 2014; Cordella et al., 2016; Farina and Amsüss, 2016; Svensson et al., 2017). Therefore, non-invasive options such as stump sockets are expected to continue to play an important role in prosthesis.

In Mayer et al. (2019), the authors proposed the non-invasive bone conduction as haptic feedback system through vibrotactile stimulation of bony landmarks of the elbow. The preliminary results, with limited number of psychometric parameters and subjects, demonstrated comparable performance to the invasive bone conduction method (Mayer et al., 2019, 2020c). It provides a higher sensitivity of the perception of lower frequencies, allowing for the use of lower stimulation forces and therefore smaller and lower power consuming transducers. In addition, it has been observed that the non-invasive bone conduction is independent from the force pressing the transducers against the human subject (Mayer et al., 2018). This is an important characteristic as volume fluctuations, present in residual limbs (Sanders et al., 2012; Paterno et al., 2018), no longer affect the perception of the provided sensory feedback.

The objective of this paper is to thoroughly investigate and determine the temporal and spatial characteristics of the non-invasive bone conduction with different user groups including subjects with amputation. The temporal parameters of the interface will be characterized by the lowest perceivable stimulation threshold and the smallest perceivable resolution in amplitude as well as frequency. The spatial parameters define the capabilities of the interface to perceive stimulation on multiple sites on the physiologically given bony landmarks on the elbow when stimulation was applied one-at-a-time. This is of interest in prosthetic grasping as combination of different types of feedback information are required (Westling and Johansson, 1984; Johansson and Westling, 1987; Augurelle et al., 2003; Mayer et al., 2020b). The temporal and spatial characteristics of the bone conduction has been conducted on both able-bodied subjects and subjects with trans-radial amputation and compared to each other and to the invasive bone conduction method.

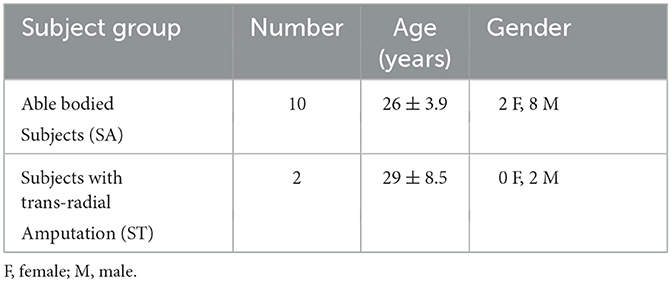

In this section, the measuring parameters, experimental setup, and protocol used to obtain temporal and spatial parameters as well as the statistical analysis are presented. The experiment was conducted with ten able-bodied subjects (SA) and two subjects with trans-radial amputation (ST), see Table 1. All subjects read the plain language statement and signed the consent form approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Melbourne (Ethics Id 1852875.1).

Table 1. Subjects were in the following results of able-bodied subjects are indicated as (SA) and for subjects with trans-radial Amputation as (ST).

The temporal domain is characterized by the perception threshold (PT) and the minimum noticeable difference for subjects, referred to as “just noticeable difference” (JND). The JND is obtained to quantify the perceivable resolution of the bone conduction interface for frequency and amplitude. The spatial domain is characterized by the ability to identify different stimulation sites (SPLIR).

PT is the minimum stimulation amplitude that subjects can perceive at a certain stimulation frequency at a certain stimulation site and can be represented as PT(f, l). For any given frequency f and site l, the amplitude thresholds changes for each person, as shown in Clemente et al. (2017, 2016), and Mayer et al. (2019), thus it is necessary to be identified.

The JND is determined for amplitude as well as frequency describing the resolution of the interface and therefore specifying the possible information rate of the interface. It is the minimum difference a subject can discriminate with a pre-determined probability. The JNDf(f, a, l) varies with stimulation amplitude a for a given stimulation frequency f and site l. The JNDa(f, a, l) varies with stimulation frequency f for a given stimulation amplitude a and site l. For a non-invasive bone conduction interface applied to the elbow (a natural location for the case of a transradial prosthetic arm), three accessible bony landmarks exist, namely the epicondylus (medialis and lateralis) and the ulnar olecranon. Therefore, multiple vibrotactile transducers can be deployed and potentially be used simultaneously. The spatial domain is therefore characterized by the spatial parameter single-point location identification rate (SPLIR).

SPLIR is the success rate that the subject correctly identifies the correct stimulation site. SPLIR is different for each site l:

where Ncorr(l) is the number of correct identified stimulations for the number of presented stimulations N(l) at site l.

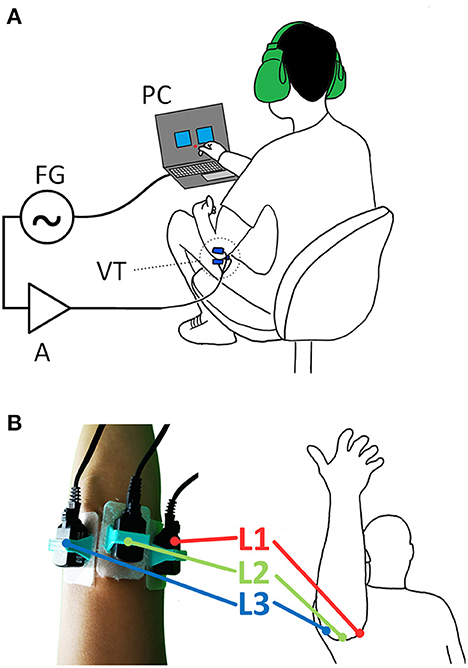

The experiment was conducted using the setup shown in Figure 1, where three Vibrotactile Transducers (VT) were driven by the frequency generator (FG) and amplifier (A) and controlled by the personal computer (PC). The three transducers T1-T3 were placed onto the 3 bony landmarks of the elbow: epicondylis medialis (L1), ulnar olecranon (L2) and epicondylus lateralis (L3), see Figure 1.

Figure 1. The experimental setup: (A) three vibrotactile transducers (VT) are controlled via a personal computer (PC) connected via USB to a frequency generator (FG) and an amplifier (A); (B) the transducers are fixed onto the bony landmarks (figure shows right arm) of the dominant hand: (L1) epicondylis medialis, (L2) ulnar olecranon and (L3) epicondylus lateralis in 3D printed holder and medical grade double sided sticker and mounted.

Three B81 transducers T1-T3 from RadioEar Corporation (USA) were utilized to provide the vibrotactile stimulus to the bony landmarks. All three transducers were calibrated using an Artificial Mastoid Type 4930 from Brüel & Kjære (Denmark) adjusted to produce the same force output of 121.5 dB at f = 1 kHz. The transducers were affixed to the bony landmarks, see Figure 1, of the subjects using a 3D printed holder (PLA/TPU) and medical grade double sided sticker Type 1510 (3M™).

A National Instruments NI USB-6343 is used.

A 15W Public Address amplifier type A4017 from Redback Inc. (Australia) with 4 − 16Ω output to drive the 12.5Ω B81 transducers and achieve a harmonic distortion of < 3% at 1 kHz.

A Windows Surface Book 2 (Intel Core i7-8, 16GB RAM, Windows 10™) and a MATLAB® GUI, guiding the user through the experiment and controlling the stimulation parameters.

The experiment is divided into temporal and spatial parameters. In order to reduce time effort for the subjects with trans-radial amputation, the able-bodied subjects carried out the whole experiment first. The longest time effort in the experiment was in the identification of the just noticeable difference. Therefore, this was carried out in stages: it was first done on the able-bodied subjects. The site with the lowest perception threshold was identified as L1. For the subjects with transradial amputation, this experiment was done for L1 instead of for all three sites, thus reducing the time-effort required from the subjects with amputation. The following explains the protocol for determining each parameter.

The temporal parameters, PT and JND, are obtained utilizing a single interval adjustment matrix (SIAM) method in order to reduce long trial times, requiring half the amount of repetitions compared to a standard two-interval forced-choice (2IFC). SIAM methods has been previously been implemented by Dosen et al. (2016) and shown to achieve same precision as a 2IFC test in Kaernbach (1990). In the SIAM procedure the outcome (hit, miss, false alarm, correct rejection) is used to adjust the signal level in a staircase manner. The response criterion is set to 0.5 which means the obtained PTs / JNDs are recognized with a 50% probability which is the same performance as in 2IFC tests (Kaernbach, 1990). This was chosen according to Kaernbach (1990) where it was shown that it results in the best threshold estimate.

A SIAM matrix,

as shown in Kaernbach (1990), achieves the best threshold estimate via a 50% target performance, i.e., half of the presented stimuli are blank. Blank stimulus means that it carries no stimulation for perception threshold and no change for JND tests. The provided stimulus Si is therefore adjusted based on the response of the subject

where δS is the step size. The index a determines if the stimulus was a blank (a = 1) or a true stimulation (a = 0). The index b is determined by the subject's yes/no response, where a yes means b = 1 and a no means b = 0. A correctly perceived stimulation changes the stimulus by −1δS while an incorrectly perceived stimulation increases the stimulus by +1δS. An incorrect perception of a blank stimulation increases the stimulus by +2δS while a correct perception of a blank keeps it at the current level (Kaernbach, 1990; Dosen et al., 2016).

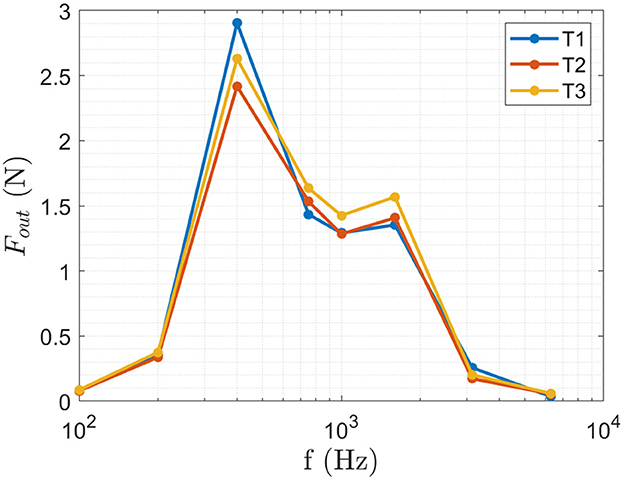

A complete psychophysical evaluation of the perception threshold would imply determining the PT at a step size determined by the Just Noticeable Difference Frequency difference (JNDf). As the JNDf is not known a priori, the preliminary results obtained in Mayer et al. (2018, 2019, 2020c) are used to define the frequency range, where the three sites L1-3 are each individually perceivable as well as dominant tactile perception is shown in a frequency range of f ∈ [100, 400, 750] Hz. The perception threshold PT(f, l) is obtained via SIAM (Kaernbach, 1990) method. The threshold for each frequency f at the site l is obtained by presenting 26 repetitions and the amplitude adjusted according to the subjects feedback via SIAM method. The frequencies f are presented in a randomized manner at each site l. To allow for a technical implementation and selection of suitable transducers the Perception Threshold is given in Newton utilizing the previously obtained calibration (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The calibration curve for the transducers T1-T3 is used to calculate the perception threshold in Newton from the recorded Voltage applied to the transducers. The produced force Fout was measured for f ∈ [100, 200, 400, 750, 1,500, 3,000, and 6,000] Hz at an amplitude of a ∈ [0.1, 0.3, 0.5] V where the figure shows the obtained results at a = 0.5 V.

Similar to PT, a complete psychophysical characterization of the JND would imply determining a full range in amplitude/frequency (AF). This would result in an impractically large number of measurements, resulting in an excessively long duration of experiments for subjects. Hence, the AF domain was divided into discrete steps, called AF reference points, where fref ∈ [100, 400, 750] Hz and aref ∈ [0.1, 0.3, 0.5] V resulting in a combination of 9 AF points where the reference amplitudes and frequencies where chosen according to the preliminary results obtained in Mayer et al. (2019). At each AF reference point, the JNDf and JNDa were obtained in increasing direction (toward the maximum value). The JND is given in Volt, which can be used to derive the smallest necessary step size for an implementation and selection of suitable driver circuitry.

Spatial parameters were obtained according to Mayer et al. (2020c). The subjects were asked to report on the site L1-L3 of the stimulation. Therefore, the subjects were presented with the stimuli on the three different sites without a priori knowledge of the stimulation site. The order of stimulation sites were applied randomly from f ∈ [100, 200, 400, 750, 1,500, 3,000, and 6,000] Hz, a = 0.5 V and each repeated 10 times. Frequencies are choose according to the shown bandwidth in Clemente et al. (2017) and Mayer et al. (2019). Each stimulation was ON for 1 s. At the start of the experiment, the subjects were provided with the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the stimulation and therefore explore the association of the three stimulation sites by voluntary inducing stimuli on each site.

The statistical analysis in this study is utilized to investigate the difference between the physiological sites and the different subject groups.

A non-parametric statistical analysis, specifically a Friedman Test (Daniel, 1990) was applied to compare the three physiological sites for each temporal and spatial parameter. In case of statistical significant differences, this was followed up by a post-hoc analysis via Wilcoxon signed rank test (Wilcoxon, 1945) to determine which of the three physiological sites was different. The p-value results are presented for the Friedman as well as the applied post-hoc Wilcoxon signed rank test.

The achieved results of perception threshold are visually presented by plotting the mean and the stand deviation as an error bar.

A summary plot shows the JNDa and JNDf at each AF reference point by its mean value, with the origin at the AF reference point. More details are shown in individual plots for each AF reference point for each site showing the obtained mean value and the stand deviation as an error bar.

The achieved results of perception threshold is visually presented similar as in Mayer et al. (2020c) by plotting the mean and the stand deviation as an error bar.

A qualitative comparison between able-bodied subjects and subjects with trans-radial amputation (ST) was carried out to compare the two subject groups for each temporal and spatial parameter. The obtained mean values for the parameters are use for such comparison.

In this section, the temporal and spatial parameters are presented and compared statistically for the different sites/bony landmarks (L1-L3) at the elbow and qualitatively across different subject groups.

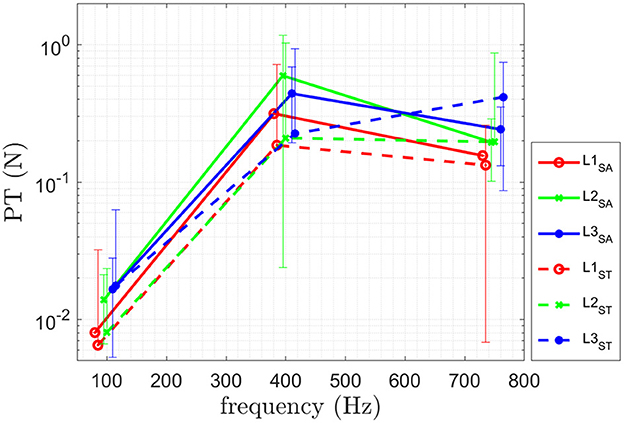

The results for PT are shown in Figure 3 and Table 2. The results of the obtained perception threshold, for the three physiological sites of able-bodied subjects (SA) and trans-radial amputees (ST) are shown in Figure 3. The mean perception thresholds for SA is [0.015 0.45 0.2] N and for ST [0.015 0.21 0.25] N for [100 400 750] Hz.

Figure 3. Results of the psychophysical evaluation for PT of ten able-bodied subjects (SA) and for two trans-radial amputees (ST). Means and standard deviations of the identified PT at frequencies [100 400 750] Hz are shown.

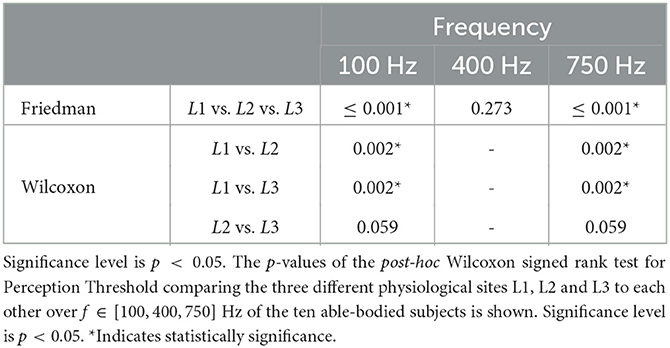

Table 2. The p-values of the Friedman for perception threshold comparing the three different physiological sites L1, L2, and L3 at all frequencies is shown.

The Friedman test results, comparing the three different sites, are shown in Table 2. The obtained results indicate a statistically significant difference in performance for [100 750] Hz for the perception threshold for the three different sites. No statistical difference is observed at 400 Hz. A post-hoc test (Wilcoxon signed rank test), is performed for [100 750] Hz and the corresponding p-values are shown in Table 2. In the following, the obtained results are summarized:

L1 vs. L2: A statistical significant difference for perception threshold at [100 750] Hz is shown in Table 2 with L1 having a lower PT.

L1 vs. L3: A statistical significant difference for perception threshold at [100 750] Hz is shown in Table 2 with L1 having a lower PT.

L2 vs. L3: No statistical significant difference was obtained for perception threshold at [100 750] Hz shown in Table 2.

Note that the p-values are at 0.059 for both cases, therefore they are only slightly above significance level of p < 0.05.

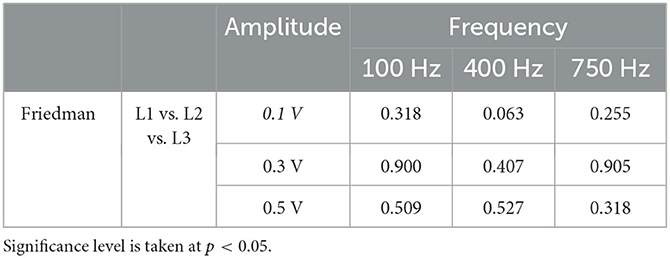

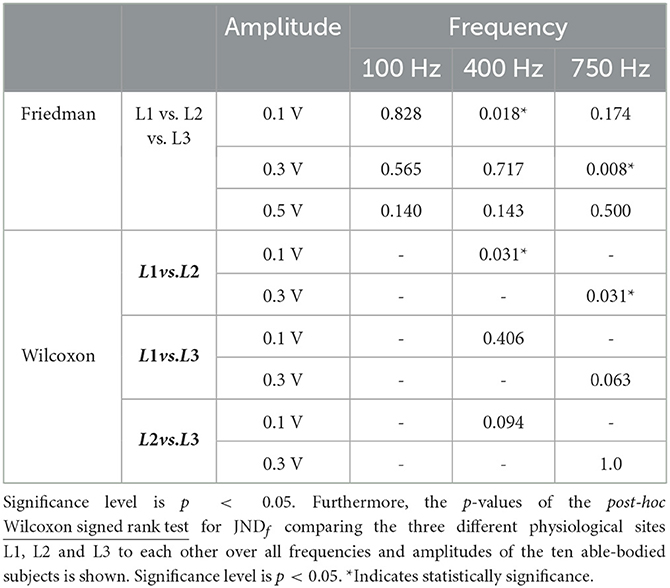

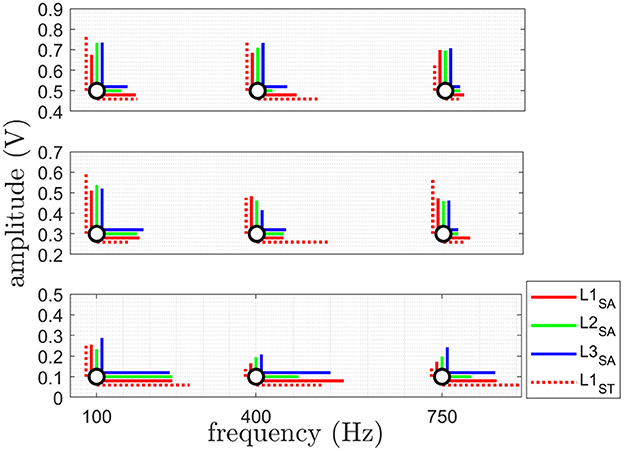

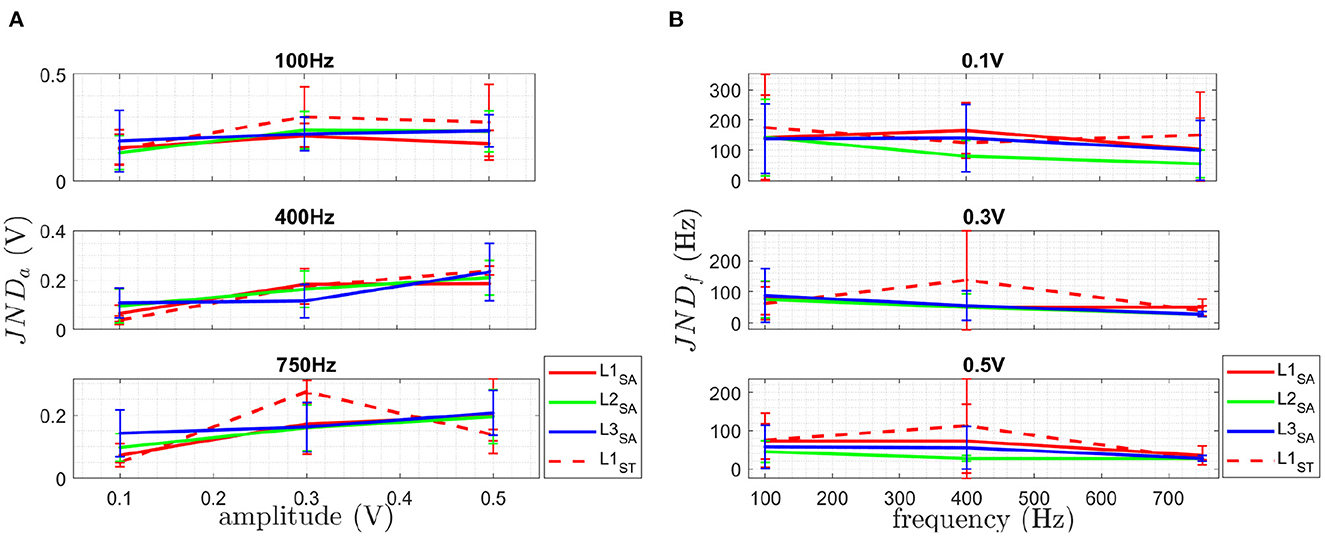

The results for the just noticable difference in amplitude JNDa are shown in Figure 5A and Table 3. The results for the just noticable difference in frequency JNDf are shown in Figure 5B and Table 4. A combined plot is shown in Figure 4, showing the mean at each site. The details of JNDa and JNDf are shown and discussed in the following.

Table 3. The p-values of the Friedman for JNDa comparing the three different physiological sites L1, L2, and L3 at all frequencies and amplitudes of the ten able-bodied subjects (SA) is given.

Table 4. The p-values of the Friedman for JNDf comparing the three different physiological sites L1, L2, and L3 at all frequencies and amplitudes is given.

Figure 4. This plot shows the combination of JNDa (vertically) and JNDf (horizontally) at each AF point. The JNDa showing the amplitude resolution for 3 different frequencies at 3 different amplitudes and JNDf giving the frequency resolution for 3 different amplitudes at 3 different frequencies in a summary plot of the obtained mean value of JNDa (blue) and JNDf (red) at each reference stimulus (black) giving. See Figure 5 for the detailed trends of each JNDa and JNDf. The results are shown for all three sites L1-L3 for the able-bodied subjects (SA) and for site L1 subjects with trans-radial amputation (ST).

The obtained results of JNDa are shown in Figure 5A. The obtained results of the Friedman test comparing the three sites, as shown in Table 3, indicate no statistically significant difference between the three physiological sites, therefore no post-hoc test was performed.

Figure 5. The plot in (A) shows the detailed JNDa at the three different chosen AF reference frequencies for the three different AF reference amplitudes and (B) shows the detailed JNDf for at the three different chosen AF reference amplitudes for the three different AF reference frequencies. Both are given for the three sites L1-L3 for SA and ST. The mean is plotted as solid line and the standard deviation given as error bar.

The obtained results of JNDf are shown in Figure 5B. The results of the Friedman test for the three sites of JNDf, as shown in Table 4, indicate a statistically significant difference for JNDf at [0.1 V, 400 Hz] as well as for [0.3 V, 750 Hz]. No statistically significant difference was found for all other discrete steps in the AF domain. The results of the post-hoc Wilcoxon signed rank test comparing the three different physiological sites L1, L2 and L3 to each other for 0.1 V at 400 Hz and 0.3 V at 750 Hz, shown in Table 4. In the following, the obtained results are summarized:

L1 vs. L2: A statistical significant difference for JNDf at 400 Hz for 0.1 V and 0.3 V is shown in Table 4.

No statistical significant difference was obtained for 0.1 V at 400 Hz and 0.3 V at 750 Hz is shown for

L1 vs. L3 as well as L2 vs. L3 in Table 4.

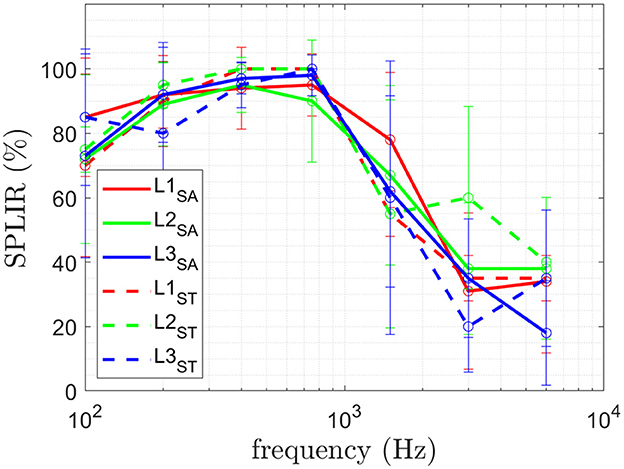

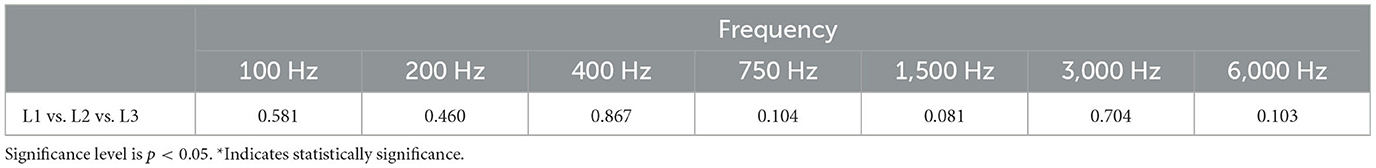

The results of the obtained SPLIR are shown in Figure 6 for all three physiological sites. The Friedman results for the three different sites, as shown in Table 5, indicate no statistically significant difference in performance for the different sites for SPLIR, hence, no post-hoc test was performed.

Figure 6. The mean and standard deviation of the SPLIR for each site L1, L2, and L3 is shown. The results of the ten able-bodied subjects (SA) is plotted in solid lines and for subjects with trans-radial amputation (ST).

Table 5. The p-values of the Friedman for SPLIR comparing the three different physiological sites L1, L2, and L3 at all frequencies and amplitudes is given.

The obtained perception threshold of the two user groups, able-bodied subjects (SA) and subjects with trans-radial amputation (ST), are shown in Figure 3. The results show a lower to similar perception threshold for ST compared to SA. A higher value is obtained for L3 at 750 Hz.

The obtained JNDa of the two user groups is shown in Figure 5A. The obtained JNDf of the two user groups is shown in Figure 5B. The obtained SPLIR of the two user groups is shown in Figure 6.

In this section, the obtained results are discussed for: (a) the three physiological sites; (b) the different subject groups and compared to results obtained for invasive bone conduction in Clemente et al. (2017).

For perception threshold site L1 performed better (in statistically significance manner) than L2 and L3 at 100 and 750 Hz, while no difference was obtained at 400 Hz. Better performance of L1 can be explained by on the one hand allowing better contact to the bones in a non-invasive manner due to little skin and soft tissue in between transducer and bone. On the other hand the ulnar nerve runs behind the medial epicondyle on the inside of the elbow and might increase the perception by being mechanically stimulated. The results of the study did not reveal any statistically significant differences in PT between the three stimulation sites at 400 Hz. While the L1 site demonstrated the lowest value, the high variance of the results could account for the lack of statistical significance (see Figure 3). One possible explanation for the variability in the results is the limited number of participants in the study. Another factor to consider is the findings of Clemente et al. (2017), which suggest that stimulation frequencies above 400 Hz can be perceived as sound. As a result, the change in sensation from tactile-only to tactile and audio could contribute to the increased variability observed in the results. The obtained PT achieved for invasive bone conduction (Clemente et al., 2017) which is a mean PT of [0.2, 0.1, 0.47] N compared to the results obtained in this study being [0.01, 0.45, 0.20] N for SA and [0.01, 0.21, 0.25] N for ST at f=[100, 400, 750] Hz. A smaller perception threshold at 100 Hz and 750 Hz for all three sites has been achieved for both user groups for non-invasive bone conduction feedback. The obtained PT at 400 Hz is higher than in Clemente et al. (2017) for all three sites.

Note that a lower perception threshold is the desired performance. Performing better with respect to PT means a lower perception threshold was obtained, allowing to use a bigger force range and therefore a larger bandwidth for the feedback information is available. It also allows the use of smaller transducers, as investigated in Mayer et al. (2020a), and therefore reduced energy consumption for battery powered prosthesis. Furthermore, lower stimulation force reduces the resulting noise and therefore increases the likelihood of the acceptance within the prosthetic field.

For JNDa, no statistically significant difference between different sites at the three different frequencies was obtained. As a result, each of the three sites is equally sensitive.

For JNDf, a statistically significant difference between different sites at [0.1 V, 400 Hz] as well as for [0.3 V, 750 Hz] was found. No statistical difference was found for all other stimulation permutations. In combination with the significantly lower PT, L1 has the biggest bandwidth for providing sensory feedback.

For SPLIR, no statistically significant difference between the different sites at the different frequencies was obtained, meaning each stimulation on each site can be located equally well. As reported previously in preliminary studies in Mayer et al. (2020c), SPLIR drops to at chance level above 1,500 Hz. Such a drop suggests that the site identification is superior for tactile perception, which is prevalent below 750 Hz (Mayer et al., 2019), and the stimulation location can not be perceived auditory perception. The stimulation in the case of auditory perception is conducted via the bones to the auditory pathway. Stimulating on three different independent sites on the elbow will ultimately still lead to stimulation of the same auditory pathway and hence not allow the subject to distinguish the stimulation site.

Only qualitative discussion is performed in the comparison of subject groups, due to the small number of ST subjects available for the study. For perception threshold, subjects with trans-radial amputation qualitative show a lower PT than able-bodied subjects and therefore are more sensitive to stimulation. This allows the use of a wider force range / larger bandwidth for the feedback information, and the use of smaller transducers for reduced energy consumption. Furthermore, the subjects with trans-radial amputation achieve similar performance for PT using non invasive bone conduction compared to the subjects with invasive bone conduction studied in Clemente et al. (2017). For JNDa, similar to PT a slightly better performance was obtained for ST compared to SA. A smaller JNDa means a higher resolution of the feedback interface is feasible and therefore more detailed sensory feedback can be provided.

For JNDf, a slightly worse performance was obtained for ST compared to SA. A higher JNDf means a coarser resolution of the feedback interface necessary and therefore less detailed sensory feedback can be provided.

For SPLIR, similar performance for ST compared to SA was obtained. Both subject groups SPLIR drops to at chance level above 1,500 Hz, suggesting that the site identification is superior for tactile perception for both subject groups.

The results obtained in this study suggest a usable bandwidth for bone conduction as a sensory feedback from 100 to 750 Hz when multiple transducers are used on multiple stimulation sites. The perception threshold is as low as 0.01 N at 100 Hz and increases to 0.2 N at 750 Hz. This range of force perception and frequency bandwidth suggest that commercially available transducers used in audiology could be used for bone conduction sensory feedback. Furthermore, the perception threshold for non-invasive bone conduction was found to be comparable to results obtained with invasive bone conduction techniques (Clemente et al., 2017). The study also revealed that frequency resolution was more distinguishable than amplitude. This finding could have implications for the design of future bone conduction feedback systems, as it suggests that greater attention may need to be paid to the frequency content of the feedback signals.

It should be mentioned that sensory feedback bone conduction is not applicable for subjects with diseases affecting the perception of such stimulation e.g., a potential subject in this study had to be excluded due to the inability to perceive stimulation likely caused by rheumatoid arthritis.

This study has evaluated the temporal and spatial parameters of the non-invasive vibrotactile feedback on the bony landmarks of the elbow. The parameters are investigated on three different physiological sites over two user groups (able bodies and subjects with transradial amputation). The paper reports the effective operating range of frequencies and amplitudes and the resolutions that can be perceived generally by the human users.

The perception threshold on the ulnar olecranon (L1) is most sensitive for able-bodied subjects compared to the medial and lateral epicondylus. The perception threshold is lower and therefore more sensitive for subjects with trans-radial amputation compared to able-bodied subjects. A qualitatively smaller, and therefore more sensitive, perception threshold has been obtained compared to invasive bone conduction.

Previous research (Clemente et al., 2017) showed that osseoperception, caused by mechanical vibrations through a bone-anchored (osseointegrated) prostheses, allows for a richer feedback and therefore was believed to play an important role in the sense of ownership of a prosthesis and the improvement of quality of live of people living with limb loss. The equivalent sensitivity achieved in non-invasive bone-conduction within this study highlights the potential of such an interface for conventional socket-based prostheses to not only provide richer feedback and functionality but also to enhance the sense of ownership of a prosthesis.

The resolution in amplitude and frequency of all three sites, as well as for able-bodied subject vs. subjects with trans-radial amputation, showed comparable performance. The detection of the stimulation site was not different between different sites as well as the two investigated user groups.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Engineering Human Ethics Advisory Group at the University of Melbourne. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RM, AM, YT, and DO: literature, experiment, data, analysis, and paper. GA and PC: paper design, experiment design, and paper review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The project was funded by the Valma Angliss Trust.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Antfolk, C., D'alonzo, M., Rosén, B., Lundborg, G., Sebelius, F., and Cipriani, C. (2013). Sensory feedback in upper limb prosthetics. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 10, 45–54. doi: 10.1586/erd.12.68

Augurelle, A. S., Smith, A. M., Lejeune, T., and Thonnard, J. L. (2003). Importance of cutaneous feedback in maintaining a secure grip during manipulation of hand-held objects. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 665–671. doi: 10.1152/jn.00249.2002

Canzoneri, E., Marzolla, M., Amoresano, A., Verni, G., and Serino, A. (2013). Amputation and prosthesis implantation shape body and peripersonal space representations. Sci. Rep. 3, 2844. doi: 10.1038/srep02844

Childress, D. S. (1980). Closed-loop control in prosthetic systems: historical perspective. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 8, 293–303. doi: 10.1007/BF02363433

Clemente, F., D'Alonzo, M., Controzzi, M., Edin, B. B., and Cipriani, C. (2016). Non-Invasive, temporally discrete feedback of object contact and release improves grasp control of closed-loop myoelectric transradial prostheses. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 24, 1314–1322. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2015.2500586

Clemente, F., Håkansson, B., Cipriani, C., Wessberg, J., Kulbacka-Ortiz, K., Brånemark, R., et al. (2017). Touch and hearing mediate osseoperception. Sci. Rep. 7, 45363. doi: 10.1038/srep45363

Cordella, F., Ciancio, A. L., Sacchetti, R., Davalli, A., Cutti, A. G., Guglielmelli, E., et al. (2016). Literature review on needs of upper limb prosthesis users. Front. Neurosci. 10, 209. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00209

Dahiya, R., Metta, G., Valle, M., and Sandini, G. (2010). Tactile sensing–from humans to humanoids. IEEE Trans. Rob. 26, 1–20. doi: 10.1109/TRO.2009.2033627

Dietrich, C., Walter-Walsh, K., Preißler, S., Hofmann, G. O., Witte, O. W., Miltner, W. H., et al. (2012). Sensory feedback prosthesis reduces phantom limb pain: proof of a principle. Neurosci. Lett. 507, 97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.10.068

Dosen, S., Ninu, A., Yakimovich, T., Dietl, H., and Farina, D. (2016). A novel method to generate amplitude-frequency modulated vibrotactile stimulation. IEEE Trans. Haptics 9, 3–12. doi: 10.1109/TOH.2015.2497229

Farina, D., and Amsüss, S. (2016). Reflections on the present and future of upper limb prostheses. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 13, 321–324. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2016.1159511

Farina, D., Vujaklija, I., Brånemark, R., Bull, A. M. J., Dietl, H., Graimann, B., et al. (2021). Toward higher-performance bionic limbs for wider clinical use. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00732-x

Goodrich, M. A., and Schultz, A. C. (2007). Human-robot interaction: a survey. Foundat. Trends Human Comput. Interact. 1, 203–275. doi: 10.1561/1100000005

Johansson, R., and Westling, G. (1987). Signals in tactile afferents from the fingers eliciting adaptive motor responses during precision grip. Exp. Brain Res. 66:141–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00236210

Kaernbach, C. (1990). A single-interval adjustment-matrix (SIAM) procedure for unbiased adaptive testing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 88, 2645–2655. doi: 10.1121/1.399985

Markovic, M., Schweisfurth, M. A., Engels, L. F., Farina, D., and Dosen, S. (2018). Myocontrol is closed-loop control: incidental feedback is sufficient for scaling the prosthesis force in routine grasping. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 15, 81. doi: 10.1186/s12984-018-0422-7

Mayer, R. M., Chen, S., Li, Z., Mohammadi, A., Tan, Y., Alici, G., et al. (2020a). “Investigation of vibrotactile transducers for a bone conduction sensory feedback system,” in 5th International Conference on NeuroRehabilitation (ICNR2020) (Virtual).

Mayer, R. M., Garcia-Rosas, R., Mohammadi, A., Tan, Y., Alici, G., Choong, P., et al. (2020b). Tactile feedback in closed-loop control of myoelectric hand grasping: conveying information of multiple sensors simultaneously via a single feedback channel. Front. Neurosci. 14, 348. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00348

Mayer, R. M., Mohammadi, A., Alici, G., Choong, P., and Oetomo, D. (2018). “Static force dependency of bone conduction transducer as sensory feedback for stump-socket based prosthesis,” in ACRA 2018 Proceedings (Dearborn, MI: Lincoln).

Mayer, R. M., Mohammadi, A., Alici, G., Choong, P., and Oetomo, D. (2019). “Bone conduction as sensory feedback interface: a preliminary study,” in 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (Berlin: IEEE), 5322–5325.

Mayer, R. M., Mohammadi, A., Tan, Y., Alici, G., Choong, P., and Oetomo, D. (2020c). “Psychometric evaluation of multi-point tactile stimulation via bone conduction,” in 8th International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BIOROB2020) (New York, NY).

Paterno, L., Ibrahimi, M., Gruppioni, E., Menciassi, A., and Ricotti, L. (2018). Sockets for limb prostheses: a review of existing technologies and open challenges. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 65, 1996–2010. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2017.2775100

Richard, G., Pietrzak, T., Argelaguet, F., Lécuyer, A., and Casiez, G. (2021). Studying the role of haptic feedback on virtual embodiment in a drawing task. Front. Virtual Reality 1, 573167. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2020.573167

Sanders, J. E., Allyn, K. J., Harrison, D. S., Myers, T. R., Ciol, M. A., and Tsai, E. C. (2012). Preliminary investigation of residual-limb fluid volume changes within one day. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 49, 10. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2011.12.0236

Saunders, I., and Vijayakumar, S. (2011). The role of feed-forward and feedback processes for closed-loop prosthesis control. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-8-60

Schofield, J. S., Evans, K. R., Carey, J. P., and Hebert, J. S. (2014). Applications of sensory feedback in motorized upper extremity prosthesis: a review. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 11, 499–511. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2014.929496

Sensinger, J. W., and Dosen, S. (2020). A review of sensory feedback in upper-limb prostheses from the perspective of human motor control. Front. Neurosci. 14, 345. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00345

Shehata, A. W., Rehani, M., Jassat, Z. E., and Hebert, J. S. (2020). Mechanotactile sensory feedback improves embodiment of a prosthetic hand during active use. Front. Neurosci. 14, 263. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00263

Stephens-Fripp, B., Alici, G., and Mutlu, R. (2018). A Review of Non-Invasive Sensory Feedback Methods for Transradial Prosthetic Hands. IEEE Access 6:6878–6899. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2791583

Svensson, P., Wijk, U., Björkman, A., and Antfolk, C. (2017). A review of invasive and non-invasive sensory feedback in upper limb prostheses. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 14, 439–447. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2017.1332989

Tahir, A. M., Iqbal, J., and Aized, T. (2018). Human machine interface: robotizing the instinctive living. Int. Rob. Automat. J. 4, 1–0. doi: 10.15406/iratj.2018.04.00142

Westling, G., and Johansson, R. (1984). Factors influencing the force control during precision grip. Exp. Brain Res. 53, 277–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00238156

Keywords: neuroprosthesis, sensory feedback restoration, human-robot interaction (HRI), tactile feedback, bone conduction (BC)

Citation: Mayer RM, Mohammadi A, Tan Y, Alici G, Choong P and Oetomo D (2023) Temporal and spatial characteristics of bone conduction as non-invasive haptic sensory feedback for upper-limb prosthesis. Front. Neurosci. 17:1113009. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1113009

Received: 30 November 2022; Accepted: 24 February 2023;

Published: 28 March 2023.

Edited by:

Min Li, Xi'an Jiaotong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Gemma Carolina Bettelani, Technical University of Munich, GermanyCopyright © 2023 Mayer, Mohammadi, Tan, Alici, Choong and Oetomo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raphael M. Mayer, cmFwaGFlbG1hcmlhbWF5ZXJAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.