- 1Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 3Department of Surgery, Royal Melbourne Hospital, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 4Department of Biochemistry and Medical Genetics, Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 5Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, St. Boniface Hospital Albrechtsen Research Centre, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 6Department of Medical Genetics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 7Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 8Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

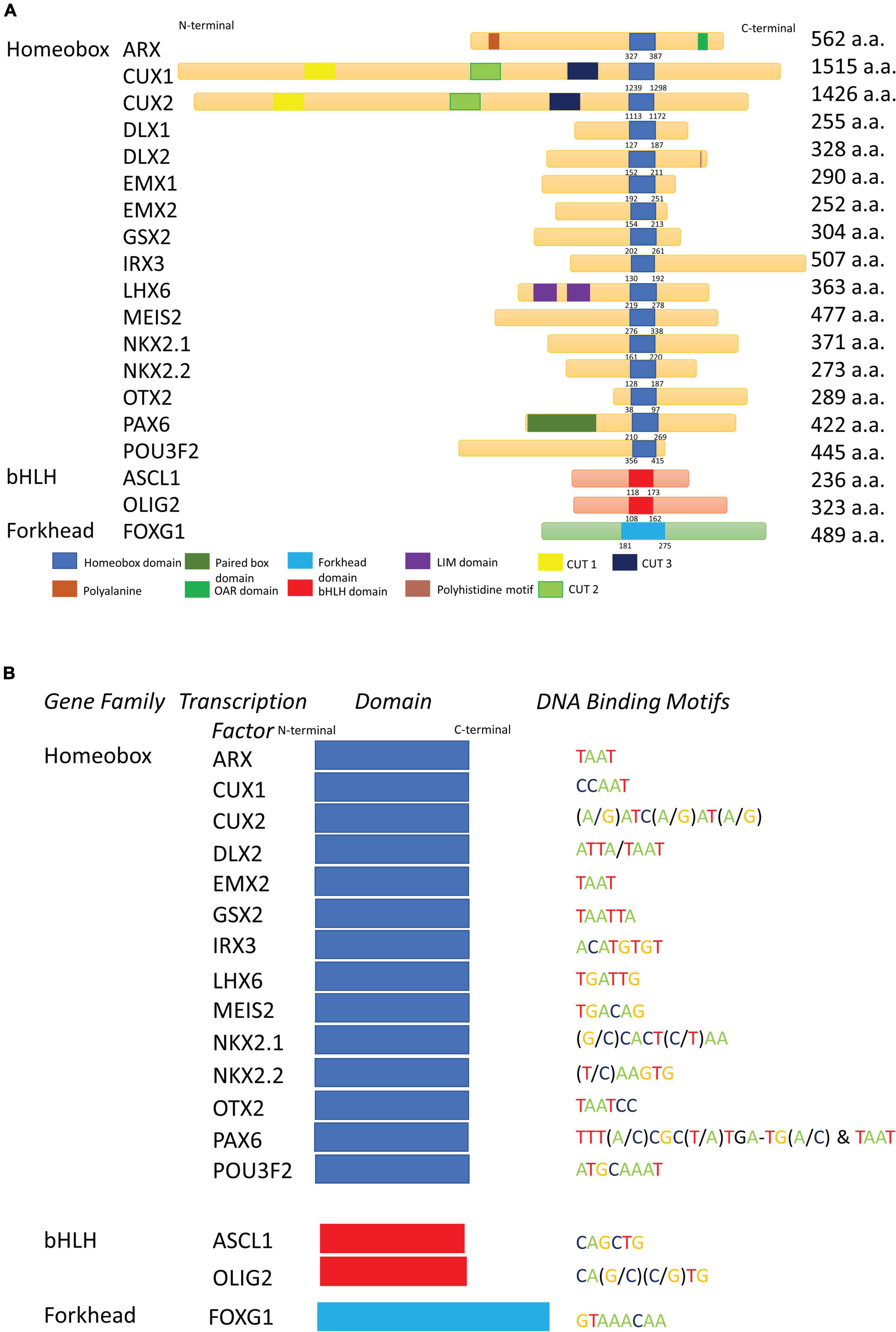

Forebrain development in vertebrates is regulated by transcription factors encoded by homeobox, bHLH and forkhead gene families throughout the progressive and overlapping stages of neural induction and patterning, regional specification and generation of neurons and glia from central nervous system (CNS) progenitor cells. Moreover, cell fate decisions, differentiation and migration of these committed CNS progenitors are controlled by the gene regulatory networks that are regulated by various homeodomain-containing transcription factors, including but not limited to those of the Pax (paired), Nkx, Otx (orthodenticle), Gsx/Gsh (genetic screened), and Dlx (distal-less) homeobox gene families. This comprehensive review outlines the integral role of key homeobox transcription factors and their target genes on forebrain development, focused primarily on the telencephalon. Furthermore, links of these transcription factors to human diseases, such as neurodevelopmental disorders and brain tumors are provided.

Introduction

Overview of Forebrain Development

Early brain development is marked by the formation of different compartments through the segmentation of the neural tube that is guided and defined by specific regional expression of transcription factors. The developing brain is sectioned into three contiguous parts, the prosencephalon in the most anterior area, which then matures into the forebrain; the mesencephalon following posteriorly, which give rises to the midbrain; and further posteriorly the rhombencephalon, the early form of the hindbrain. These areas further partition, where the prosencephalon separates into primary prosencephalon (diencephalon) and secondary prosencephalon (telencephalon) (Puelles, 2013, 2018), and the rhombencephalon divides into the metencephalon and myelencephalon. In contrast to the other two regions, the mesencephalon does not divide (Stiles, 2008). Within the forebrain, the prosomeric model depicts the division of this area into 7 segments called the prosomeres (Rubenstein et al., 1994; Puelles and Rubenstein, 2003). The diencephalon develops into 3 prosomeres (p1, p2, p3), which are then recognized as the pretectum, thalamus and pre-thalamus. The secondary prosencephalon develops into two hypothalamo-telencephalic prosomeres (hp1, hp2), later giving rise to the hypothalamus and telencephalon. The mesencephalon contributes to two prosomeres (m1, m2) (Puelles, 2018).

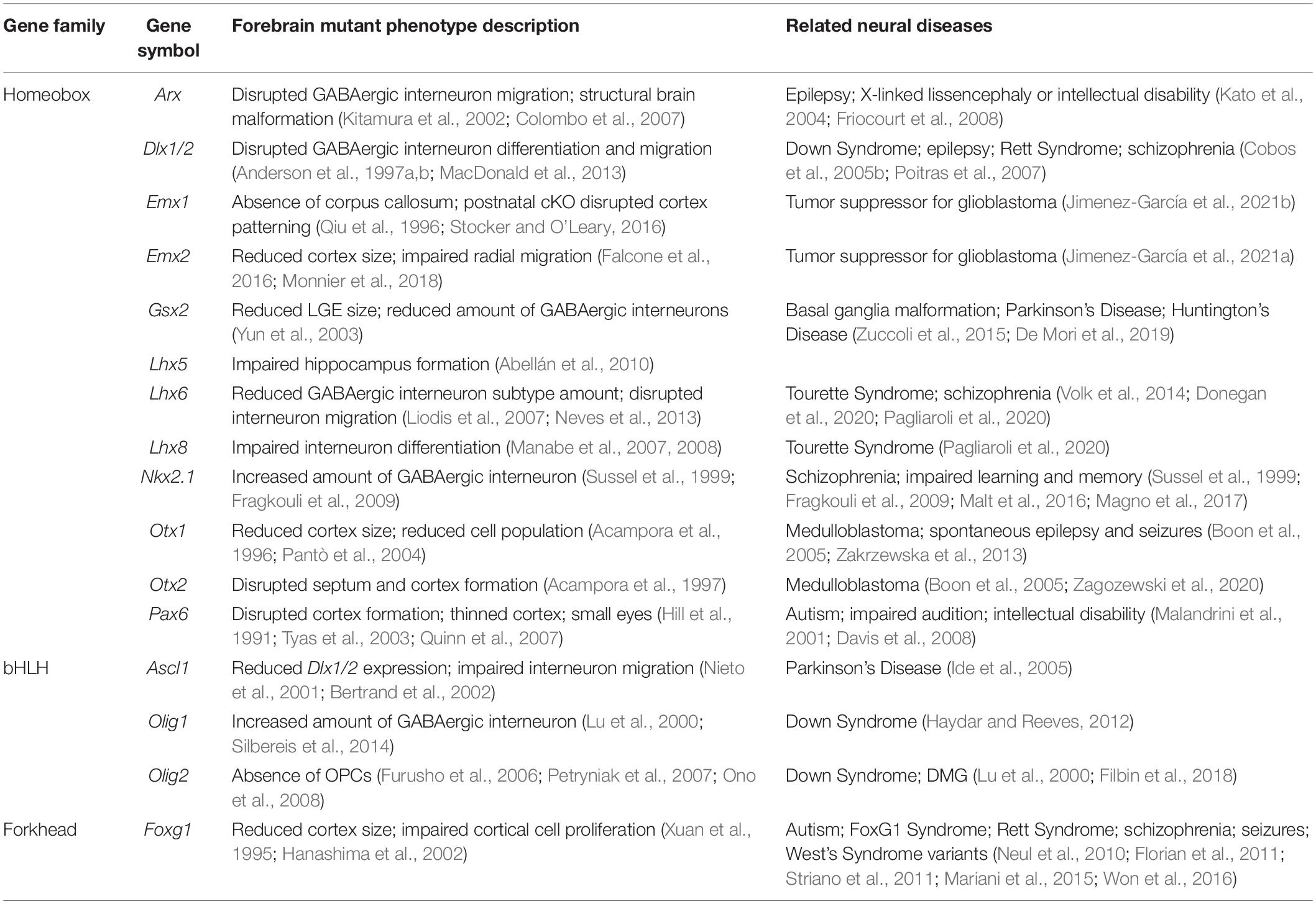

The regions adjacent to the ventricular surface in the brain are the ventricular zone (VZ), followed by the subventricular zone (SVZ), and the mantle zone (MZ) (Figure 1A). The VZ contains radial glia, which then differentiate into intermediate neural progenitors that populate the SVZ, where both of these cell types can give rise to neurons (Miyata et al., 2001; Noctor et al., 2001, 2004; Haubensak et al., 2004). The telencephalon can be divided into the dorsal (pallium) and ventral (subpallium) telencephalon, where the neocortex and the ganglionic eminences (GE) are located, respectively. The anatomic region separating the dorsal and ventral telencephalon is often referred to as the pallio-subpallial boundary (PSB). The GE is divided into lateral, medial, and caudal GE (LGE; MGE; CGE), and ventral to the MGE is the preoptic area (PoA) (Figure 1A). The LGE can be further separated in the ventral LGE (vLGE), where striatal projection neurons originate, and the dorsal LGE (dLGE) that gives rise to intercalated cells of the amygdala and neurons in the olfactory bulb along with the lateral LGE wall (Yun et al., 2001; Stenman et al., 2003; Waclaw et al., 2010). The LGE is a local source of retinoic acid, a morphogen that regulates cortical patterning and regionalization (see Shibata et al., 2021; Ziffra et al., 2021 for more details) (Toresson et al., 1999; Molotkova et al., 2007; Shibata et al., 2021; Ziffra et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Expression of homeobox genes in the developing embryonic mouse forebrain. (A) Schematic illustration of coronal section of E13.5 forebrain depicting ventricular zone (VZ), subventricular zone (SVZ), and mantle zone (MZ) on the left-hand side and neocortex (NCx), lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), and medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) on the right-hand side. The VZ and SVZ are the proliferative zones, comprised of progenitor cells. Depending on the identity of these differentiated cells, the cells migrate either tangentially (red arrows) or radially (purple arrows) into the MZ and proceed to mature (Left-hand side). Migration toward the olfactory bulb from the VZ of the LGE also occurs (Right-hand side). (B) 3-dimensional schematic of the developing forebrain. The LGE and MGE are contained within the cortex, above the olfactory bulbs (OB). The midbrain (MB) and hindbrain (HB) are also labeled. Insets show schematic representations of 4 coronal sections taken from the forebrain depicting the expression of key homeobox gene expression patterns from rostral to caudal at embryonic time point E13.5. Gene name colors correspond to the expression color shown in the section. Transcription factor expression can be overlapping or structurally distinct and is related to the function of the individual transcription factor (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2019). Arx and Meis2, to an extent, are expressed throughout the forebrain, whereas Lhx2, Emx1/2, Pax6, Otx1, and Pou3f2 are expressed in the neocortex and pallium. Dlx1/2, Gsx1, Otx2, and Cux1 are expressed in the GE, Gsx2 is expressed specifically in the LGE, and Nkx2.1, Cux2, Lhx6, and Lhx8 in the MGE. Irx3 is not depicted here as it is expressed in the thalamus (not shown). For detailed depictions of gene expression patterns, readers are encouraged to review the cited primary references or the Allen Brain Atlas: Developing Mouse Brain (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2019). NCx, neocortex; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; V, ventricle; VZ, ventricular zone; SVZ, subventricular zone; MZ, mantle zone.

Origin of Cortical and Striatal Neurons

Excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activities need to be balanced in order for the nervous system to maintain homeostasis and to optimally process information; these are governed by projection and inhibitory neurons in the brain, respectively. Neuronal progenitor cells (NPC) are produced in both dorsal and ventral telencephalon; NPCs from the dorsal telencephalon give rise to projection neurons (glutamatergic) and NPCs from the ventral telencephalon differentiate into inhibitory interneurons (γ-amino butyric (GABA)-ergic) (Anderson et al., 1997a, 2002b). These neuronal origin sites are conserved amongst mammals, as shown through studies in primates, rodents, and humans, in which some cortical interneurons could be generated locally in the dorsal telencephalon (Letinic et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2013). Glutamatergic neurons make up ∼ 70% of the neuronal population in the mouse, with the remaining ∼ 30% being GABAergic interneurons (Hendry et al., 1987). Within the ventral telencephalon, GABAergic interneurons are produced mainly from Nkx2.1 expressing progenitor cells in the MGE and PoA (Fogarty et al., 2007; Gelman et al., 2009), and migrate tangentially to reach the neocortex (Marín and Rubenstein, 2003). These ventral telencephalic interneurons mainly consist of parvalbumin (pva+), somatostatin (sst+), and 5ht3a+ interneurons subtypes (Rudy et al., 2011). Many sst+ interneurons arise and migrate from the CGE, while other interneuron subtypes arise from progenitor cells in the LGE and CGE, including the vasoactive intestinal peptide and cholecystokinin expressing interneurons which reside in the MZ (Anderson et al., 2001; Nery et al., 2002; Miyoshi et al., 2010). The main population of striatal projection neurons comprises the GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs) which arise from progenitors in the LGE, and account for ∼ 80% of the striatal neuron population in primates and rodents (Graveland and DiFiglia, 1985). Some key marker genes for MSN differentiation include Foxp1/2, Ascl1, Ebf1, and Meis2 (Garel et al., 1999; Toresson et al., 1999; Carri et al., 2013). The differentiation of MSNs is dependent on the temporal expression of a set of transcription factors, particularly the repressive function of Dlx1/2 on Ascl1 at specific timepoints, to promote differentiation and migration of striatal neurons (Anderson et al., 1997b; Yun et al., 2002). EBF1 then controls later differentiation and migration from the SVZ to the MZ (Garel et al., 1999).

Olfactory Bulb Neurogenesis

In mice, olfactory bulb neurogenesis occurs from embryonic until early postnatal stages, and is dependent on the neuronal types (Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004; Tucker et al., 2006; Figueres-Oñate and López-Mascaraque, 2016). Initially, projection neurons are generated by E12.5, followed by the development of inhibitory interneurons by E14.5 (Bayer, 1983; Tucker et al., 2006). The olfactory bulb projection neurons, mitral/tufted (M/T) cells, originate from progenitor cells in the pallium and are differentiated from Pax6+ radial glia (Whitman and Greer, 2009; Imamura and Greer, 2013). M/T cells can adopt both radial and tangential migration. Earlier born neurons predominantly migrate radially and populate the deeper cortical layers, while later born projection neurons are more likely to migrate tangentially to the superficial cortical layer (Imamura et al., 2011). Migration of these projection neurons is regulated by a number of transcription factors, such as PAX6 and LHX2, which are also crucial for cortical neuron migration (Nomura et al., 2007; Saha et al., 2007). Transcription factors specific for olfactory bulb projection neuron migration include Ap2-epsilon, Arx, and FezF1, which are all important for proper orientation of M/T cells, as well as the expression of Tbr1/2 (Yoshihara et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2009; Shimizu and Hibi, 2009; Imamura and Greer, 2013).

Olfactory bulb interneurons, in contrast to cortical interneurons, are derived from the dLGE, and postnatally in the SVZ, with the exception of Emx1+ pallial progenitors (Wichterle et al., 2001; Stenman et al., 2003). Subsequently, these interneurons tangentially migrate through to the olfactory bulb, postnatally through the rostral migratory stream (Kriegstein and Alvarez-Buylla, 2009). Although born in neuroanatomic regions distinct from cortical interneurons, olfactory bulb interneuron migration is regulated by a similar set of factors. Some of these include Dlx1/2, Ascl1, and Robo-Slit (Andrews et al., 2006; Long et al., 2007). Upon reaching the olfactory bulb, the interneurons differentiate into GABAergic interneurons and subsequently, subtype specification takes place (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994; Sequerra, 2014) which is itself dependent on the developmental stage, i.e., whether born at an embryonic or postnatal stage (De Marchis et al., 2007; Batista-Brito et al., 2008). Examples of transcription factors that regulate interneuron development are Sp8/Sp9 which are essential for olfactory bulb development (Li et al., 2017). For a more in-depth discussion about olfactory bulb development refer to a recent review from Tufo et al. (2022).

Radial and Tangential Migration of Neurons

There are two modes of neuronal migration, radial and tangential, classified by the axis of migration (Figure 1B). Cells move from the VZ toward the MZ generally by radial migration, and can descend within the VZ before migrating toward the MZ. Radial migration occurs during the development of the cerebral cortex, spinal cord, striatum and thalamus (Ayala et al., 2007). Morphological changes of interneurons mark the start of radial migration, whereas restriction of such changes also impairs the migration of these interneurons (LoTurco and Bai, 2006). Two different modes of movements are adopted during radial migration (Nadarajah et al., 2001). Interneurons migrate by somal translocation, by attaching to the outer surface of the developing brain (pial surface) and as microtubules shorten, the nucleus is pulled forward (Franco et al., 2011). Locomotion, on the other hand, allows interneurons to be guided by radial glial cells toward the destination during the radial migration through complex forebrain structures (Rakic, 1972).

Tangential migration is adopted by cortical interneurons born in the GE, as these cells need to migrate from the GE to the neocortex while avoiding movement toward the striatum (DeDiego et al., 1994). Despite being derived in different areas, interneurons arising from the MGE, CGE and preoptic area have a similar transcriptome (Mayer et al., 2018), which could contribute to the similar migration pattern these interneurons adopt. Transcription factors tightly regulate the migration fate of interneurons, such as the expression or repression of Nkx2.1 determines whether interneurons migrate into the striatum or neocortex, respectively (Nóbrega-Pereira et al., 2008). There are two major paths for interneurons to migrate from the GE to the developing neocortex, through a superficial route that bypasses the MZ or a deeper route that passes through the SVZ (Figure 1A; Wichterle et al., 2001). These migration paths are guided by signaling molecules such as the chemokine CXCL12, which attract interneurons, and its receptor CXCR4. Studies have shown that disruption of CXCL12 or its receptor CXCR4 led to interneuronal mislocalization (Stumm et al., 2003; López-Bendito et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011b). Furthermore, Tbr2+ cortical intermediate progenitor cells may actively attract interneuron migration into the cortex, which is concurrently modulated by CXCL12 signaling (Sessa et al., 2010). Another chemokine, Neuregulin 3 (Nrg3), mediated by ErbB4 attracts and regulates the final destination of GABAergic interneurons in the cortex (Rakić et al., 2015). Similarly, repulsive guidance cues Semaphorin 3A and 3F also play a role in guiding interneuron tangential migration, where their expression in the LGE prevents interneuron migration toward the basal area (Chen et al., 2008). This repulsion is achieved by the interactions between these molecules and their receptors neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) and neuropilin-2 (Nrp2), which are expressed in migrating interneurons (Marín et al., 2001). Some other extrinsic factors act as mitogens to provide motility and control the rate of migration for interneurons, such as the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (Powell et al., 2001). Furthermore, GABA itself can act as a motogen and accelerate tangential migration (Inada et al., 2011). These processes that direct neuron fate determination are ultimately regulated by members of the homeobox and basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor families (Table 1).

Homeobox Genes

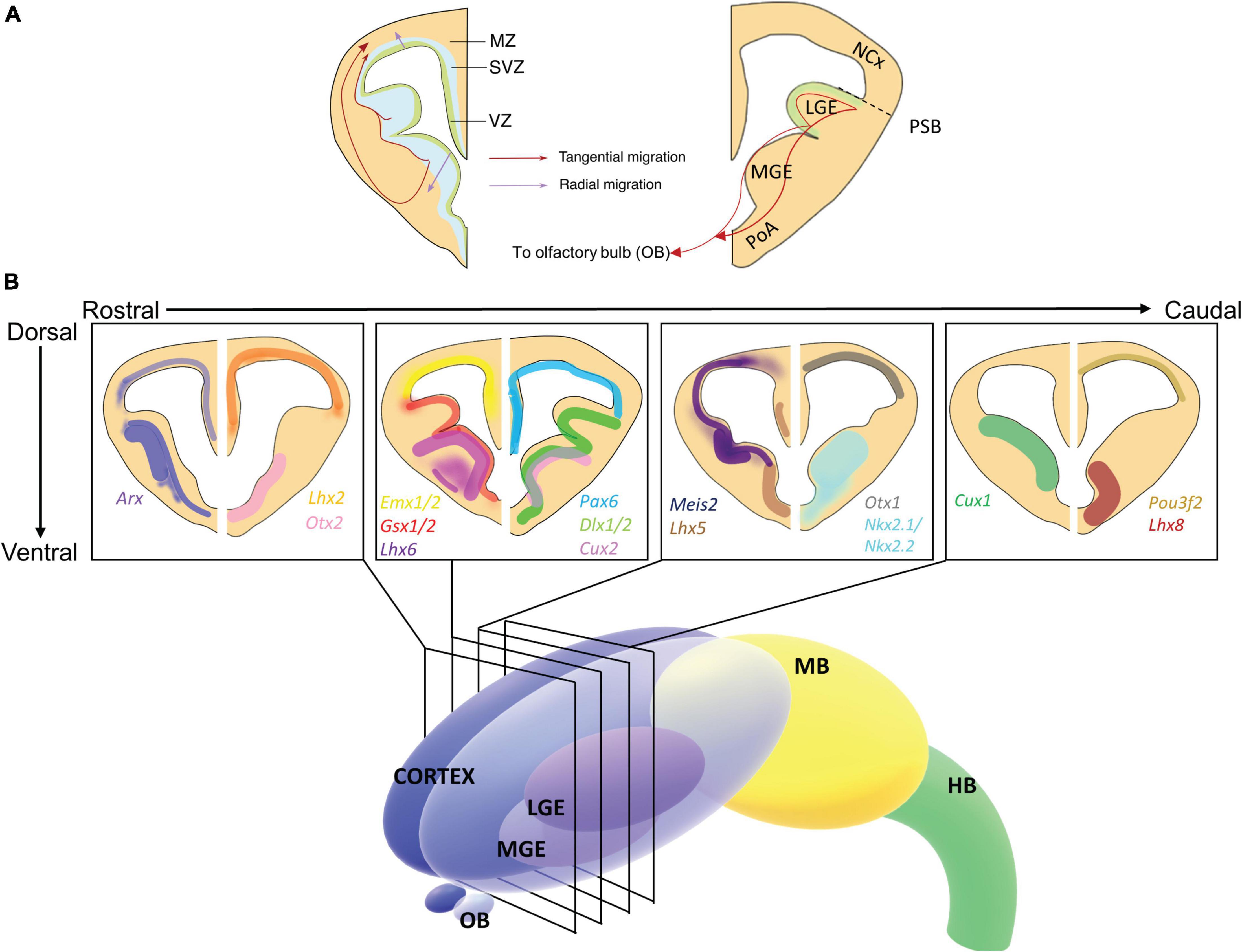

Homeobox genes are an important gene family for embryonic development, defined by a conserved homeodomain (HD) containing a helix-loop-helix-turn-helix structure (Gehring et al., 1994; Noyes et al., 2008). The 60 amino acid HD is commonly located at the carboxyl terminal end of the protein, and binds DNA primarily through the 50th residue, usually being a glutamine, allowing homeobox genes to function as transcription factors (Figure 2; Kappen, 2000). This DNA binding motif is located in the second and third helices, which recognizes and binds to the major groove of DNA at specified consensus sites (Table 2). Further, the N-terminal arm contributes to the binding strength through interactions with the DNA minor groove, typically through a basic residue such as arginine at the 5th residue in the HD (Rohs et al., 2009). Apart from the consensus binding sequence, other important factors for DNA binding specificity include cofactors and additional DNA binding domains, such as the paired domain (PRD) in PAX superfamily members. Water molecules have been shown to be crucial for the HD to bind DNA (Billeter et al., 1996). Protein-protein interactions driven by the flanking regions around HD also increase the specificity of DNA binding (Li et al., 1995; Amin et al., 2015; Merabet and Lohmann, 2015). Homeobox proteins often contain other domains apart from the HD, which provide additional DNA specificity for these proteins, and have allowed characterization of homeobox proteins into 11 different classes, such as the Antennapedia (ANTP), Paired (PRD), LIM and NK classes (Holland et al., 2007), and can be further divided into different families within these classes. Large functional and comparative genomics studies have enabled analyses of these proteins, and allowed accurate annotation, naming and classification of homeobox genes (Holland et al., 2007).

Figure 2. Homeobox transcription factors and their key functional domains. (A) Schematic depiction of the domain structure of selected homeobox, bHLH and forkhead transcription factors illustrating the highly conserved nature of the homeodomains and other DNA-binding domains of these transcription factors. Other significant functional domains are also shown. DLX2, but not DLX1, contains a polyhistidine motif in its C-terminus. PAX6 contains both a paired domain, as well as the HD. ARX, along with a HD, also contains a polyalanine repeat and an Aristaless domain. a.a., amino acid. (B) The DNA binding sites for Homeobox, bHLH and Forkhead transcription factors from (A). A consensus DNA binding motif for DLX1 and EMX1 is not available.

Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Genes

Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins are another superfamily of transcription factors present in most eukaryotes, with critical functions during embryonic development, such as neurogenesis and myogenesis. bHLH domains contains two alpha helices, helix 1 and helix 2. These helices are connected by a short loop, and at the amino-terminal end of helix 1 is a basic region (Murre et al., 1989). This basic region binds DNA by recognizing a core CANNTGG motif, known as an E-box motif, and is specific for different transcription factors (Table 2). Upon binding, the basic region is fitted into the major grove of the DNA. The HLH domain interacts with other proteins, forming different homo- or hetero-dimeric complexes that are required for DNA binding (Ellenberger et al., 1994). The unique combinations of these bindings give rise to the diverse transcriptional regulatory functions of bHLH proteins during development. bHLH proteins can be roughly divided into those that are either cell-type specific or widely expressed where the group of transcription factors governing neuron development are often referred to as proneural proteins (Lee, 1997; Srivastava et al., 1997).

Selected Transcription Factors Encoded by Homeobox Genes

In the following major section of this comprehensive review, detailed summaries of 21 homeobox genes (in alphabetical order) that encode homeodomain containing transcription factors are provided. These genes were selected due to their essential role in forebrain development. However, we acknowledge that this selection of genes excludes several other important homeobox genes as well as key bHLH (Ascl1, Olig1, Olig2, and Olig3) and forkhead (Foxg1) genes required for neurodevelopment. For this reason, we have included Ascl1, Olig1/2/3, and Foxg1 in Figure 2 and the Tables.

A brief note about gene and protein nomenclature is useful. By consensus: mouse gene, Dlx; zebrafish gene, dlx; human gene, DLX; mouse and human protein, DLX.

Aristaless Related Homeobox Gene

The Aristaless related homeobox (Arx) paired-like HD transcription factor is the vertebrate homolog of the Drosophila aristaless (al) gene, which is essential for appendage formation (Miura et al., 1997). The gene is located on human chromosome Xp22.13 and is reported to be involved in neurological disorders such as X-linked intellectual disabilities (Table 3; Bienvenu et al., 2002; Friocourt and Parnavelas, 2010). In vertebrate embryogenesis, Arx transcriptionally regulates interneuron specification and migration (Fulp et al., 2008; Friocourt and Parnavelas, 2010; Olivetti and Noebels, 2012). ARX contains multiple structural domains and motifs, including the HD, a PRD-like domain, an N-terminal octapeptide domain, a central acidic domain and the C-terminal aristaless domain as well as three nuclear localization sequences and four polyalanine (polyA) tracts (Miura et al., 1997; Figure 2). ARX binds the transcriptional co-repressor TLE1, through the TLE1 octapeptide domain, and recognizes DNA at TAAT sites (Jennings et al., 2006; McKenzie et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2012). In vitro assays show that although ARX can be phosphorylated at multiple sites, it is unclear whether ARX functions are regulated by its phosphorylation state (Mattiske et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2020).

Aristaless Related Homeobox is expressed in various parts of the developing forebrain, such as the SVZ in developing GE and the VZ in the neocortex (Figure 1B; Miura et al., 1997; Colombo et al., 2004). Arx expression in the neocortex is limited to the proliferating neural progenitor cells, and is suppressed in cells radially migrating from the VZ (Friocourt et al., 2006), whereas in the GE Arx is continually expressed after neuronal differentiation and migration. Embryonic mice with homozygous Arx mutations have small brains with a thin neocortex and die upon birth, which may be related to defective tangential migration of cortical interneurons (Kitamura et al., 2002; Colombo et al., 2007; Friocourt et al., 2008). Targeted conditional deletion of Arx in the neocortex results in intermediate progenitor cell proliferation, with a reduced population of cortical neural progenitors. ARX also directly regulates cortical progenitor cell expansion through transcriptional regulation of CDKN1C, a cell cycle progression inhibitor in cortical VZ and SVZ (Colasante et al., 2015). The expression pattern of Arx also reveals its contribution to establishing the dorsoventral identity of the developing brain, where Arx suppresses ventralization in the dorsal forebrain by repressing Olig2 expression. Olig2 is a ventral specific gene and its expression is induced through Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling. The expression of SHH downstream targets, Gli1 and Ptch3, are increased in Arx cKO mice dorsal telencephalon. Thus ARX represses these SHH downstream signals, and in turn represses Olig2 expression (Lim et al., 2019). Both inactivation, through shRNA, and overexpression of Arx impact GABAergic interneuron tangential migration to the neocortex from the MGE (Colombo et al., 2007). Furthermore, Arx is a direct regulatory target of DLX2, another homeobox transcription factor that regulates tangential migration, where overexpression of Dlx2 increases Arx levels and reduction of Dlx2 expression reduces Arx in the GE (Cobos et al., 2005a). By gain- and loss-of-function analysis, Arx was demonstrated to mediate the tangential interneuronal migration driven by DLX2, but not GABAergic neuron specification (Colasante et al., 2008). Conditional deletion of Arx in the ventral telencephalon further supports a role for Arx in tangential migration resulting in an overall reduction in the number of mature interneurons (Marsh et al., 2016). Additionally, ARX has been shown to transcriptionally regulate genes important for migration, such as Cxcr4, Cxcr7, Ebf3, and Lhx7 (Fulp et al., 2008; Colasante et al., 2009; Quille et al., 2011).

Aristaless Related Homeobox mutations can lead to severe neurological diseases, including X-linked intellectual disability, epilepsy, as well as structural brain malformations (Table 3; Friocourt and Parnavelas, 2010), and these mutations have been studied extensively using mouse models (Kitamura et al., 2002, 2009; Marsh et al., 2009; Price et al., 2009). The phenotypes related to ARX mutations can be grouped based on whether there is a corresponding malformation. Disorders in the malformation group include X-linked lissencephaly associated with abnormal genitalia (Kitamura et al., 2002) and Proud syndrome (Kato et al., 2004), whereas the non-malformation group includes epilepsy, non-syndromic X-linked intellectual disability, and X-linked Infantile Spasms Syndrome (Bienvenu et al., 2002; Kitamura et al., 2009; Price et al., 2009) and different epilepsy syndromes such as West syndrome (Strømme et al., 2002; Kato et al., 2003). Many mutations in ARX have been found in the first two polyA tracts, where the polyA tracts are expanded by insertion of either additional alanine or other residues (Kitamura et al., 2009). A common mutation consists of an in-frame 24bp duplication (Szczaluba et al., 2006), whilst longer mutations, 27bp, and 33bp have also be reported (Demos et al., 2009; Reish et al., 2009). The longest known mutation exhibits the addition of eleven alanine residues, resulting in Ohtahara syndrome (Kato et al., 2007). Other intellectual disability, seizures related disorders have also been observed (Turner et al., 2002). In summary, these ARX mutations disrupt DNA and protein binding ability, perturbing the transcriptional activity of ARX, thereby affecting cortical development (Nasrallah et al., 2012; Siehr et al., 2020).

Cut-Like Homeobox Genes

The Cut-like homeobox genes encode a transcription factor family [Cux homeobox 1/2 (Cux1/2)], previously called CCAAT-displacement protein (CDP) or Cut-like homeobox 1/2 (Cut1/2), that are the mammalian homologs of the Drosophila gene cut locus (ct) (Blochlinger et al., 1988). Ct is responsible for controlling the fate of neuronal progenitor cells in the peripheral nervous system and external sensory organs in Drosophila (Bodmer et al., 1987; Blochlinger et al., 1988) and plays a crucial role in dendritic arborization of specific sensory neurons (Grueber et al., 2003). CUX1 is located on human chromosome 7q22 and is frequently rearranged in cancers (Scherer et al., 1993), while CUX2 is on chromosome band 12q24.11-q24.12 (Craddock et al., 1993). CUX transcription factors contain up to four DNA binding regions, comprised of one HD, including a histidine residue at the 9th amino acid of the third helix (Blochlinger et al., 1988), and one, two, or three highly homologous Cut repeats of approximately 70 amino acids (CR1, CR2, CR3) (Figure 2A; Nepveu, 2001). However, individual Cut repeats are unable to bind to DNA on their own but interact with other Cut repeats or with the Cut HD to bind DNA (Moon et al., 2000). CR1/CR2 mediate transient binding to DNA (Moon et al., 2000) and the CR3 repeat and the HD have been reported to form bipartite high affinity DNA binding interactions (Harada et al., 1994, 1995). Cux1 and Cux2 splice variants encode for protein isoforms with different combinations of DNA binding domains (Weiss and Nieto, 2019). Proteolytic cleavage of the full length p200 CUX1 protein generates a p110 protein which contains CR2, CR3 and the HD (Goulet et al., 2004). While the full-length p200 protein acts as a transcriptional repressor, p110 can act as repressor or activator depending on the type of promoter it interacts with (Yoon and Chikaraishi, 1994; Truscott et al., 2004, 2007; Harada et al., 2007). CUX proteins can act as transcriptional repressors either indirectly by competing with transcriptional activators for binding to target sites, or actively suppressing transcription via a mechanism that involves recruiting histone deacetylases through the Ala, Pro-enriched carboxyl domain (Cowell and Hurst, 1994; Mailly et al., 1996; Nepveu, 2001). CUX transcriptional activity is regulated by post-translational modifications at the Cut repeats which include acetylation, proteolysis (Sansregret et al., 2010), and phosphorylation by PKC (Coqueret et al., 1996), CKII (Coqueret et al., 1998), cAMP-dependent protein kinase (Michl and Downward, 2006), and cyclin A/Cdk1 (Santaguida et al., 2001), which repress transcriptional activity.

Cux1 expression is detected widely in embryonic and adult tissues (Nieto et al., 2004), while Cux2 is more specifically expressed in the nervous system (Quaggin et al., 1996) as well as the limb buds and urogenital system (Iulianella et al., 2003). Cux1 and Cux2 are expressed early during brain development in neural progenitor cells in the ventral and dorsal telencephalon, as early as E14 for Cux1 and E10.5 for Cux2, specifically Cux1 is expressed in the VZ and SVZ of whole GE (Nieto et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 2004; Figure 1). In contrast, Cux2 is solely expressed in the SVZ of the MGE, and is enriched in tangentially migrating cortical interneurons (Nieto et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 2004). Indeed, Cux2 is mostly expressed in SVZ/IZ early during development while it is later expressed across most of the cortex (Zimmer et al., 2004). Furthermore, Cux2 expression distinguishes two cortical neuronal subpopulations with different origins, migration models, and phenotypic characteristics: a population of tangentially migrating GABAergic cortical interneurons and another DLX-negative neuronal population produced in the pallium, which migrates radially, divides in the SVZ and accumulates in the IZ (Zimmer et al., 2004).

In addition to controlling neural specification and differentiation in upper cortical layers, CUX proteins can act as repressors for developmental processes such as dendritic arborization (Grueber et al., 2003; Cubelos et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010). Overexpression of Cux1, but not Cux2, results in decreased dendritic arborization in cultured cortical pyramidal neurons, whereas dendritic complexity increases upon reduction of Cux1 (Li et al., 2010). A mechanism whereby Cux1 transcriptionally represses dendritic arborization is through suppression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip7 and further plays a role in proliferating cells by repressing the p21 cyclin kinase inhibitor (Coqueret et al., 1998).

Cux2 is regulated by PAX6 and contributes to determining the upper layers (II-IV) of the cortex (Zimmer et al., 2004). Deletion of either Cux1 or Cux2 in mice does not alter overall cortical and brain organization (Cubelos et al., 2008a), whereas most Cux1 and Cux2 double homozygous mutants die prior to birth (Cubelos et al., 2008b). Although, the few pups that survive P0 do not display defects in neuronal migration or in layer specific protein expression (Cubelos et al., 2008b), Cux1/Cux2 double knockout (DKO) mice display abnormal dendrites and synapses indicating a critical role for Cux genes in dendritogenesis (Cubelos et al., 2010). The formation of cortical interneurons in Cux single and double mutants is impaired while loss of Reelin expression is only observed in upper cortical layers II-IV in double mutants (Cubelos et al., 2008b).

Cux2 deficient mice display increased brain volume, cell density and thickness of the upper cortical layers (II-IV), caused by an increase in the number of neuronal progenitor cells (Cubelos et al., 2008a). CUX1 target genes include Nfib, Fezf2, Pou6f2 and Sox5 which are all transcriptional regulators highly expressed in lower layers of the cortex (Gray et al., 2017). In addition to regulating upper cortical layer formation, Cux2 has also been shown to control cell cycle exit (Cubelos et al., 2008a). Therefore, Cux1 and Cux2 regulate neuronal proliferation of intermediate neuron precursors in SVZ, as well as the proliferation rate of neuronal precursor cells fated to form pyramidal cortical neurons in the upper layers of the cortex (Cubelos et al., 2008a,b) and in the spinal cord (Iulianella et al., 2008).

Mutations in CUX1 have been associated with global developmental delay with or without impaired intellectual development (GDI) (Platzer et al., 2018) while CUX2 is associated with intellectual disorders, seizures, autism spectrum disorder and bipolar affective disorder (Glaser et al., 2005; Barington et al., 2018). CUX1 has also been shown to undergo inactivating mutations and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in a number of human cancers (Ramdzan and Nepveu, 2014; Wong et al., 2014). Loss of CUX1 activates the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway as a result of transcriptional downregulation of the PI3K inhibitor, PIK3Ip1 (Wong et al., 2014). This mutation in CUX1 results in increased tumor growth and increased susceptibility to PI3K-Akt inhibition (Wong et al., 2014). CUX1 has also been implicated in the regulation of proteosome-mediated degradation of the Src tyrosine kinase resulting in altered tumor cell migration and invasion (Aleksic et al., 2007).

Distalless Genes

Distalless (dll) was discovered in Drosophila for its essential role in limb development (Cohen et al., 1989). Dlx genes are the vertebrate orthologs of dll; six members of this gene family can be found in humans and mice, occurring as bigenic clusters (Dlx1/2, Dlx3/4, and Dlx5/6); however, only Dlx1, Dlx2, Dlx5, and Dlx6 are expressed in the forebrain (Figure 1B). Dlx1/2 and Dlx5/6 are located on mouse chromosomes 2 and 6, and on human chromosomes 2q31.1 and 7q21.3, respectively (Stock et al., 1996). These bigenic clusters are organized from tail-to-tail, with highly conserved intergenic enhancers located between the two genes. Dlx1/2 and Dlx5/6 each contain two intergenic enhancers: i12a and i12b for Dlx1/2, and i56a and i56b for Dlx5/6 (Ghanem et al., 2003; Ruest et al., 2003). These cis-regulatory elements, although dissimilar in sequence, have overlapping activity and are essential for the expression of these genes (Fazel Darbandi et al., 2016). Dlx5/6 expression is regulated by Dlx1/2, where the absence of Dlx1/2 reduces Dlx5/6 expression through the intergenic enhancer, revealed using gene reporter systems (Zerucha et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2004). Likewise, removing the intergenic enhancers with a targeted mutation attenuates Dlx5/6 expression in the forebrain, suggesting these intergenic enhancers are necessary for Dlx expression (Robledo et al., 2002; Ghanem et al., 2003). Dlx transcription factors are expressed in the developing GE and are essential for forebrain development (Pleasure et al., 2000). From embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5), expression is induced in the order of Dlx2, Dlx1, Dlx5, and Dlx6 (Eisenstat et al., 1999). In mice, Dlx1/2 are expressed in the VZ in the GE, and are clearly separated at the pallio-subpallial boundary (Figure 1B). Dlx5/6 are expressed in the MZ of the ventral telencephalon, and additionally, Dlx1, Dlx2, and Dlx5 are expressed in the SVZ in an overlapping manner, coinciding with regions where GABAergic interneurons are produced (Liu et al., 1997; Acampora et al., 1999; Depew et al., 1999; Robledo et al., 2002; Cobos et al., 2005b; Weinschutz Mendes et al., 2020).

Dlx1 and Dlx2 single gene homozygous knockout (KO) mice die prematurely at postnatal day 0 (P0) with minor abnormalities in GABAergic neuron formation, demonstrating DLX1 and DLX2 are somewhat functionally redundant (Qiu et al., 1997). Cortical neurons are reduced in postnatal Dlx1 KO mice which can lead to seizures (Cobos et al., 2005b). Dlx1/2 and Dlx5/6 double homozygous mutants also die at P0 with a more significant forebrain defect compared to the single KO mice. Tangential interneuron migration from the MGE to the neocortex is blocked in Dlx1/2 double homozygous mutants both in mice and zebrafish, hindering GABAergic interneuron development (Anderson et al., 1997a,b; MacDonald et al., 2013). Dlx1/2 double homozygous mutants also have reduced Dlx5/6 expression, which results in altered progenitor cell fate in the dorsal and ventral telencephalon (Pla et al., 2017). Dlx5/6 double homozygous mutant mice also exhibit tangential migration defects, with poor specification of parvalbumin GABAergic interneuron subtypes (Wang et al., 2010). Therefore, Dlx genes are essential for the differentiation of GABAergic neurons and their subsequent tangential migration (Anderson et al., 1997a,b; Marin et al., 2000).

Distalless genes transcription factors promote interneuron production by regulating transcription of various downstream targets in the ventral telencephalon, binding to the core HD DNA binding motif ATTA/TAAT (Zhou et al., 2004; Table 2). A recent report has found that DLX2 binds preferentially to transcription factors to mediate both its’ repression and activation functions (Lindtner et al., 2019). GABA is synthesized by glutamic acid decarboxylases 1 and 2 (GAD1; GAD2) which are co-expressed with Dlx1/2 in the VZ and SVZ of the GE in mouse, zebrafish, and humans (Erlander et al., 1991; Liu et al., 1997; Martin et al., 2000; MacDonald et al., 2010; Al-Jaberi et al., 2015). Gad1 and Gad2 expression is dependent on the DLX factors, where DLX1/2 bind directly to the promoters of Gad1/2 in vivo and induce Gad1/2 expression; Gad expression is reduced in Dlx1/2 double homozygous mutant mice (Stühmer et al., 2002; MacDonald et al., 2010; Li et al., 2012a; Le et al., 2017). However, Gad expression is not completely ablated in these mutants, which could be due to the compensatory function of residually expressed DLX5/6. Additionally, DLX proteins promote the differentiation of GABAergic and cholinergic interneuron subtypes through regulation of Lhx6 and Lhx8, where both Lhx genes have reduced expression in Dlx1/2 double homozygous mutants (Petryniak et al., 2007; Long et al., 2009). DLX2 also downregulates Olig2 expression to repress oligodendrocyte development in early neurogenesis, and hence may control the balance between oligodendrocyte and neuron production (Petryniak et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2020). ASCL1, in turn, represses Dlx2 expression in later developmental stages, to allow the expression of Olig2 and promote oligodendrocyte production (Petryniak et al., 2007; Poitras et al., 2007). The repression of Olig2 by DLX2 also represses the promotion of the progenitor cell states, and likewise DLX2 downregulates several other transcription factors with similar functions, such as Gsx2, Otx2, and Pax6 (Yun et al., 2001; Hoch et al., 2015; Lindtner et al., 2019). SMAD transcription factors, which are part of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling pathway, interact with DLX2 in binding to the promoter regions of DLX2 target genes in the telencephalon. Although expression of TGF-β signaling components is unaffected in the Dlx1/2 double mutants, the interaction between DLX2 and SMAD factors indicate TGF-β could play a role in GABAergic interneuron differentiation (Shi and Massagué, 2003; Maira et al., 2010).

In addition to cell differentiation, DLX transcription factors also regulate interneuron tangential migration. DLX1/2 regulates this process by repressing terminal differentiation of interneurons (Cobos et al., 2007). Interneurons develop axons and dendrites post migration, promoted by proteins that regulate cytoskeleton and cell motility such as MAP2 and PAK3 (Anderson et al., 1997b; Bokoch, 2003; Dehmelt and Halpain, 2004). In Dlx1/2 DKO mice, interneurons have significantly reduced migration, increased neurite length, and upregulated expression of genes which are normally expressed post-migration. Hence, DLX1/2 represses these genes to enable tangential migration of interneurons to the cortex (Cobos et al., 2007). Nrp2, encoding for a Semaphorin-3A and 3F receptor, is also repressed by DLX1/2, as evident in the marked increase of NRP2 expression in the forebrains of Dlx1/2 DKO mice (Le et al., 2017). In Dlx5/6 double homozygous mutant mice, a receptor for tangential migration Cxcr4 is downregulated in the SVZ, which likely contributes to the impaired tangential migration observed in these mutants (Wang et al., 2010, 2011b).

Although DLX transcription factors have not been directly linked to any neurological diseases, many associations have been made between DLX mutations and neurodevelopmental defects (Table 3). Epilepsy and Rett syndrome had been linked to Dlx mutations in mouse models. Furthermore, DLX1/2 and DLX5/6 are found on chromosomes 2q and 7q, which are autism susceptibility loci (Cobos et al., 2005b; Hamilton et al., 2005; Horike et al., 2005). By site-directed mutagenesis of the Dlx1/2 intergenic enhancer regions, transgenic mice with autism-like phenotypes were generated, showing the possible role of disrupted Dlx1/2 in autism development (Poitras et al., 2007). Several neurodevelopmental disorders have been related to Dlx genes due to the importance of this gene family in regulating GABAergic interneuron production and migration (Kato and Dobyns, 2004; Verret et al., 2012). A DLX2 direct target Grin2b is linked to schizophrenia, epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism, which provides evidence that DLX2 may contribute to neural diseases (Endele et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2019). DLX2 regulation of transcription factors such as Arx and Olig2 also support that DLX factors may potentially contribute to neurological disease (Lindtner et al., 2019).

Empty Spiracle Genes

Empty spiracles homeobox (Emx) genes are the mammalian homologues of the Drosophila gene empty spiracle (ems), which is responsible for head structure development (Younossi-Hartenstein et al., 1997). Emx1 and Emx2 are homeobox genes important for dorsal patterning in the forebrain. From mouse studies, Emx2 is shown to be expressed earlier, from E8.5, whereas Emx1 is expressed from E9.5 (Simeone et al., 1992; Gulisano et al., 1996; Medina and Abellán, 2009). The expression of Emx2 is regulated by two sets of enhancers, one at the 5′ region and the other at the 3′ region (Theil et al., 2002; Suda et al., 2010; García-Moreno and Molnár, 2015). Emx2 expression is directly promoted by DMRT5 and downregulated by the Emx2 antisense transcript Emx2OS (Spigoni et al., 2010; Saulnier et al., 2013). Both Emx genes are expressed in the dorsal telencephalon, with the highest level of expression rostrolaterally, and decreased expression in a gradient caudomedially (Mallamaci et al., 1998). Emx1 expression is nested within Emx2 expression, and only Emx2 is expressed in the caudomedial part of dorsal telencephalon (Simeone et al., 1992; Yoshida et al., 1997). While Emx2 expression is restricted to progenitor cells, Emx1 is expressed in both progenitor and differentiated cells (Gulisano et al., 1996).

Both Emx1 and Emx2 are necessary for the development of the archipallium in the dorsal telencephalon, and especially the development of the hippocampus and cortex in later stages (Simeone et al., 1993; Pellegrini et al., 1996; Yoshida et al., 1997; Hamasaki et al., 2004). Emx1 and Emx2 double homozygous mutants do not develop the dorsomedial telencephalon, whilst this phenotype is not observed in Emx1 or Emx2 single homozygous mutants (Bishop et al., 2003; Shinozaki et al., 2004). The impaired development of the neocortex could also be due to impaired tangential migration, as interneurons in Emx1/Emx2 double mutant cannot migrate out of the GE into the cortex (Shinozaki et al., 2002). Homozygous Emx1 mutants do not develop significant defects in the embryonic neocortex (Yoshida et al., 1997; Bishop et al., 2002). However, postnatal studies have shown that Emx1 could play a role in cortical patterning, as rostral areas were expanded and caudal areas were reduced in the Emx1 null mice (Stocker and O’Leary, 2016). Emx1 homozygous mutants also lack development of the corpus callosum, and heterozygous Emx1 mutants exhibit partial penetrance (Qiu et al., 1996). However, Emx2 homozygous mutants have reduced neocortex size by E11.5, with defective dorsal telencephalon development, including aberrant hippocampus formation and impaired radial migration of neurons (Pellegrini et al., 1996; Yoshida et al., 1997; Mallamaci et al., 2000). In these mutants, there is ventralization of the dorsal telencephalon with reduced dorsal gene marker expression (Ngn1, Ngn2, and Emx1) and increased ventral marker gene expression (Gsx2, Ascl1, and Dlx1/2). Emx2/Pax6 double homozygous mutants demonstrate a stronger phenotype with a lack of dorsal identity, showing these two homeobox factors function cooperatively to specify dorsal telencephalic identity (Muzio et al., 2002a,b). Furthermore, reciprocal inhibition is observed between Emx2 and Pax6, where the cKO of one factor results in the upregulation of the other (Muzio et al., 2002b).

EMX1 and EMX2 regulate a number of factors required to specify dorsal telencephalic identity (Table 2). An important aspect of EMX2 function is its’ regulation of the formation of the PSB, along with PAX6 and GSX2 (Yun et al., 2001; Muzio et al., 2002a,b). EMX2 cooperates with DMRT5 and DMRT3 to repress Gsx2 expression, with all three proteins binding directly to the ventral telencephalon specific Gsx2 enhancer, thereby contributing to the development of the PSB (Desmaris et al., 2018). A mutual repressive relationship between EMX2 and FGF8 also promotes the differentiation of neural progenitor identity, where EMX2 downregulates FGF8 to promote differentiation, whilst FGF8 represses EMX2 to promote anterior-posterior patterning (Fukuchi-Shimogori and Grove, 2001, 2003; Cholfin and Rubenstein, 2008). In addition, EMX2 represses Sox2 by inhibiting positive regulators from binding to Sox2 enhancers. Sox2 cKO mutants have a defective hippocampal phenotype, rescued when one Emx2 allele is lost (Mariani et al., 2012). This demonstrates that EMX2 regulates hippocampal development, consistent with the observed Emx2 homozygous phenotype (Pellegrini et al., 1996). Wnt signaling promotes Emx2 expression through activation of an Emx2 telencephalic enhancer, through the Wnt downstream factor GLI3 (Theil et al., 1999, 2002; Muzio et al., 2005). Additionally, EMX2 restricts Wnt-1 expression in the forebrain, which is essential for maintaining normal neuronal radial migration (Iler et al., 1995; Ligon et al., 2003). EMX1 regulates Nrp1, an axonal guidance receptor that regulates cortical connectivity (Wright et al., 2007; Lim et al., 2015). Furthermore, EMX2 regulates Teneurin-1, a transmembrane protein that also functions in axonal guidance, through binding to an alternative promoter (Table 3) and promoting the transcription of an alternative transcript (Drabikowski et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006; Beckmann et al., 2011).

While EMX2 functions in promoting cell differentiation in the developing brain, it is considered as a possible tumor suppressor in different cancers, such as sarcoma, colorectal cancer, gastric tumors, and glioblastoma (Table 3; Li et al., 2012b; Aykut et al., 2017; Jimenez-García et al., 2021a,b). In many tumors, EMX2 expression is downregulated due to methylation of the EMX2 promoter (Okamoto et al., 2010; Qiu et al., 2013). EMX2 over-expression blocks cell proliferation through inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway, and also leads to cell cycle arrest with increased cell death of glioblastoma cells (Falcone et al., 2016; Monnier et al., 2018; Jimenez-García et al., 2021a).

Genomic Screened Homeobox Genes

Genomic screened homeobox (Gsx, formerly Gsh) genes encode a family of transcription factors important for patterning of the ventral telencephalon. Gsx genes are the mammalian orthologues of the Drosophila intermediate neuroblasts defective (ind) genes; mutation in Drosophila induces a loss of intermediate neuroblasts (Weiss et al., 1998). GSX proteins bind to DNA via the homeobox domain (Figure 2), and GSX2 activity may depend on its dimerization state, where homodimers promote gene activation, and monomers enhance gene repression (Salomone et al., 2021).

Gsx1 and Gsx2 are widely expressed in the neural progenitors found in the VZ of the LGE (Toresson et al., 2000). Gsx2 is mostly expressed in the dLGE with lower levels in the vLGE with complementary patterns for Gsx1, localizing to the vLGE and MGE (Toresson and Campbell, 2001; Yun et al., 2001). Gsx1 and Gsx2 are partially functionally redundant, due to similarities in their consensus DNA binding sites (Hsieh-Li et al., 1995; Valerius et al., 1995; Toresson and Campbell, 2001; Pei et al., 2011). Gsx2 and Gsx1/Gsx2 DKO mice have a reduced LGE size, with decreased number of olfactory bulb neurons as well as GABAergic interneurons (Yun et al., 2003). Dorsal markers including Pax6 and Ngn2 also expanded ventrally in Gsx2 homozygous mutants (Szucsik et al., 1997; Corbin et al., 2000; Toresson et al., 2000; Yun et al., 2001). The expression patterns of Pax6 and Gsx2 are complementary, separated by the PSB, and these genes function cooperatively to define the dorsoventral identity of the developing forebrain (Figure 1B; Yun et al., 2001; Carney et al., 2009). Gsx2 expression is repressed by a number of genes in the dorsal telencephalon, including Pax6, Emx2, Dmrt3 and Dmrt5 (Muzio et al., 2002a,b; Desmaris et al., 2018).

Gsx2 regulates specification of neurons, oligodendrocytes and glial cells in the LGE (Kessaris et al., 2006; Fogarty et al., 2007; Chapman et al., 2018). Neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis take place in the dLGE and vLGE, respectively, and are tightly controlled by Gsx2 in a time-dependent manner. Conditional knockout (cKO) of Gsx2 upregulates the oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) marker Pdgfrα, and promotes premature oligodendrocyte differentiation (Corbin et al., 2003; Chapman et al., 2013, 2018). Ascl1, a bHLH transcription factor crucial for neurogenesis, has reduced expression levels in Gsx2 homozygous mutant mice (Chapman et al., 2013). Studies have shown that Gsx2 upregulates Ascl1 in earlier embryo stages, promoting neuronal differentiation in early embryonic stages (Méndez-Gómez and Vicario-Abejón, 2012; Chapman et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Since Ascl1 promotes the NPCs to differentiate into interneurons, GSX2 inhibits ASCL1 activity to regulate the balance between progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation (Roychoudhury et al., 2020). Whilst GSX2 upregulates Ascl1, it inhibits the homo- and heterodimer formation of ASCL1 essential for its DNA binding ability (Johnson et al., 1992; Nakada et al., 2004; Roychoudhury et al., 2020). In earlier embryonic stages (E9-11), Gsx2 promotes striatal projection neuron specification from the vLGE, and in later embryonic stages (E12.5–E15) olfactory bulb interneurons are specified in the dLGE (Waclaw et al., 2010).

Overexpression of Gsx2 from E13.5 promotes the specification of dLGE over vLGE, and subsequently favors neurogenesis over oligodendrogenesis (Waclaw et al., 2010; Pei et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2013). GSX1 in Ascl1 expressing progenitor cells represses Gsx2 and promotes the maturation of NPCs by transitioning these cells from the VZ to the SVZ and induces differentiation (Pei et al., 2011). Gsx1/Gsx2 DKO mice have expanded OPCs comparable to Gsx2 homozygous mutants (Chapman et al., 2018). However, the reduced proliferation of OPCs in the Gsx1/2 DKO compared to Gsx2 homozygous mutants suggests GSX1 functions in promoting OPC proliferation in the ventral telencephalon (Chapman et al., 2018). Hence, Gsx2 regulates neurogenesis through repressing Gsx1, and blocks oligodendrogenesis in early embryonic stages. Furthermore, downregulation of Gsx2 in late embryonic stages is essential for oligodendrogenesis to proceed, which could be a result of negative autoregulation (Salomone et al., 2021).

Along with promoting Ascl1 expression, GSX2 regulates neural differentiation via increasing Dlx1 and Dlx2 expression in the LGE (Table 2; Corbin et al., 2000; Toresson et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2013). Dlx1/Dlx2 are part of the gene regulatory network downstream of Ascl1 and in turn negatively regulate Gsx1 and Gsx2 expression (Yun et al., 2002; Long et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013). The activation of Gsx1 and Gsx2 regulates the patterning of LGE, and later silencing of these two genes by Dlx1/2 promotes subcortical neural differentiation (Anderson et al., 1997b; Cobos et al., 2005b). Furthermore, GSX2 also represses Dbx1, a homeobox transcription factor expressed in the hindbrain and spinal cord that regulates dorsoventral brain patterning and specification of Cajal-Retzius cells (Yun et al., 2001; Bielle et al., 2005; Winterbottom et al., 2010). DBX1 has also been suggested to repress Gsx1 in the ventral telencephalon; however, further studies are necessary to validate this relationship (Poiana et al., 2020).

Congenital brain malformations may result from mutations in the GSX2 gene (Table 3). Whole exome sequencing of patients with basal ganglia malformations reveals a homozygous missense mutation in GSX2 HD that impair its transcriptional activity (De Mori et al., 2019). These patients have similar phenotypes to homozygous mutant mice models, with malformations or defective structures derived from the LGE and MGE (putamen, globus pallidus, caudate nucleus and olfactory bulb), as well as maldevelopment of the forebrain midbrain junction (De Mori et al., 2019). These anatomical defects are also associated with a range of neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s Diseases (Zuccoli et al., 2015; Table 2).

Iroquois-Related Homeobox 3 Gene

The iroquois-related homeobox 3 (Irx3) is a TALE HD containing transcription factor (Figure 2), orthologous to the Iroquois-complex genes in Drosophila, which are responsible for the development of sensory organ, body-wall and wing identity (Gómez-Skarmeta et al., 1996; Bürglin, 1997; Diez del Corral et al., 1999). Irx genes in vertebrates are organized into two clusters, IrxA and IrxB, each containing 3 genes from the family. The IrxA cluster consists of Irx1, Irx2, and Irx4, whereas IrxB contains Irx3, Irx5, and Irx6, located on mouse chromosome 8 and human chromosome 16 (Peters et al., 2000).

Iroquois-related homeobox 3 is important for thalamic patterning in the diencephalon (Robertshaw et al., 2013). Irx3 is predominantly expressed in the midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord in early neurogenesis (E7.5–E9.5), and expression shifts rostrally to the diencephalon from E10.5 (Bosse et al., 1997). Notably, the expression patterns of Irx3 and Ascl1 during early neurogenesis are similar, which may suggest a regulatory relationship between the two transcription factors (Cohen et al., 2000). Similar to Dlx1/2/5 and Nkx2.1/2.2, Irx3 expression is posterior to the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI), a region in the diencephalon that releases SHH signaling molecules for the patterning of prethalamus and thalamus (Kitamura et al., 1997; Eisenstat et al., 1999; Robertshaw et al., 2013; Murcia-Ramón et al., 2020a). High levels of SHH signaling induces rostral thalamus, and subsequently the production of GABAergic interneurons, while a low level of SHH promotes caudal thalamus specification and glutamatergic interneurons production (Kiecker and Lumsden, 2005). Consistent with this, ectopic expression of Irx3 promotes the expression of thalamus differentiation markers Sox14 and Gbx2, both in the prethalamus and the dorsal telencephalon in response to SHH signaling (Kiecker and Lumsden, 2004; Robertshaw et al., 2013). However, such markers were not expressed upon Irx3 ectopic expression in the ventral telencephalon, which may be due to SIX3 repression of Irx3, which restricts its activity to specify thalamus identity (Kobayashi et al., 2002; Robertshaw et al., 2013). In Xenopus models, knockdown of Irx3 reduces midbrain size, and caudally shifts the forebrain-midbrain boundary, illustrating its function in ensuring the normal patterning of the diencephalon (Rodríguez-Seguel et al., 2009). A key co-regulator of thalamus patterning is PAX6, which is expressed anterior to the forebrain-midbrain boundary and specifies the caudal thalamus. The overlapping expression patterns of Irx3 and Pax6 (see Figure 2A) mark the region of thalamus patterning, while caudal and rostral thalamus identity is determined by levels of SHH signaling (Robertshaw et al., 2013).

Iroquois-related homeobox 3 is considered to be a determinant for obesity, in relation to the fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) genes, due to the role of Irx3 in neurogenesis at the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, developed from the anterior hypothalamus (Smemo et al., 2014). Single-minded 1 (Sim1), a bHLH transcription factor in the hypothalamus represses Irx3 expression, as Sim1 KO mice exhibit ectopic expression of Irx3 in the anterior hypothalamus (Caqueret et al., 2006; Son et al., 2021b). Sim1 homozygous mutant mice are perinatal lethal, whereas Sim1 heterozygous mutant mice exhibit neurodevelopmental defects and hyperphagia, as Sim1 is important for neurogenesis in the hypothalamus (Michaud et al., 1998; Holder et al., 2004). The neurogenesis defects in these mutant mice are due to the ectopic expression of Irx3 and Irx5 in the anterior hypothalamus (Son et al., 2021a,b). In Sim1/Irx3/Irx5 triple heterozygous KO mice, the neuronal population at the anterior hypothalamus is restored. Similarly, cKO of Irx3 at the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus partially rescues the neuronal disruption observed in Sim1 heterozygous mutant mice, with no observable differences in body weight or hyperphagic phenotype (Son et al., 2021b).

Lhx (LIM-HD Family) Genes

The Lhx transcription factors belong to the LIM-HD family of homeobox genes that have both a LIM zinc finger domains and a HD (Figure 2; Dawid et al., 1998; Bach, 2000). The LIM zinc finger domain is named after the first three genes discovered in the family, Lin-11, Isl1 and Mec-3, and participates in protein-protein binding (Way and Chalfie, 1988; Freyd et al., 1990; Karlsson et al., 1990). Of the various members of the Lhx gene family found in both mouse and humans, Lhx1, Lhx2, Lhx5, Lhx6, and Lhx8 (i.e., L3/Lhx7) are important for differentiation and migration of interneuron in the developing telencephalon (Alifragis et al., 2004; Abellán et al., 2010; Godbole et al., 2018). Mutant mice studies had provided insights into the importance of these Lhx genes for forebrain development (Wanaka et al., 1997).

Lhx1 homozygous mutant mice have an increased number of PoA-derived interneurons and glia cells, suggesting Lhx1 regulates the survival of these cells by regulating the balance between apoptosis and proliferation. Also the PoA-derived interneurons in Lhx1 null mice migrate through the ventral telencephalon, compared to a more controlled migration in the wild-type mice through the developing neocortex (Symmank et al., 2019). Lim5 is expressed in the forebrain of zebrafish and Xenopus, and Lhx5, the Lhx1 paralog, is the murine ortholog. Lhx5 is expressed predominantly in the hindbrain at E8, and the developing forebrain starting at E9.5. After E11.5, Lhx5 is exclusively expressed in the ventral telencephalon, hypothalamus and diencephalon, which is complementary to Dlx5 expression (Figure 1B; Sheng et al., 1997). Both Lhx1/5 are expressed in the rostral area of the ZLI in the diencephalon, but only Lhx1 is expressed in the caudal ZLI (Nakagawa and Leary, 2001). Lhx5 homozygous mutant mice are defective in hippocampus development, where progenitor cells can proliferate but fail to exit the cell cycle to migrate or differentiate (Zhao et al., 1999). Cajal-Retzius neurons are responsible for the organization of the neocortex through the secretion of reelin (Soriano and Del Río, 2005). In mice, Lhx5 regulates the development and migration of Cajal-Retzius cells, which could be critical to the malformation of the hippocampus in Lhx5 null mutants (Abellán et al., 2010). Lhx1 likewise is expressed in some Cajal-Retzius cells, but limited to the septal area, and lateral olfactory to caudomedial zones (Miquelajáuregui et al., 2010). Additionally, Lhx5 can regulate forebrain development by suppressing Wnt signaling in zebrafish embryos, via promoting the expression of Wnt inhibitors Sfrp1a and Sfrp5, supported by the increase of Wnt signaling in zebrafish embryos lacking Lhx5 expression (Peng and Westerfield, 2006). There is some evidence of Lhx5 inhibiting Wnt5a in murine hypothalamus, promoting the growth of the mamillary body; however, more studies are required to confirm this regulatory effect and mechanism. Another possible target of Lhx5 is Lmo1 (LIM-only1), where Lmo1 competes with Lhx5 to bind with the Lhx binding partner LDB, thereby inhibiting Lhx function (Bach, 2000; Heide et al., 2015).

Lhx2 is the mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila apterous gene, first described in 1913, as an essential gene for Drosophila wing development (Metz, 1914; Butterworth and King, 1965). Lhx2 homozygous mutants have reduced forebrain volume, but expanded neocortex and PSB composing the entire forebrain (Porter et al., 1997; Bulchand et al., 2001; Monuki et al., 2001). Lhx2 plays a role in suppressing hippocampus (hem) and PSB (antihem) development up to E9.5 and E10.5, respectively (Roy et al., 2014; Godbole et al., 2018). Suppression of hippocampal development is regulated by interactions between Lhx2 and other transcription factors, namely Foxg1 and Pax6. Foxg1 has been shown to directly regulate Lhx2 expression, where the loss of Foxg1 also results in a loss of Lhx2 at E9.5. cKO of Lhx2 after E9.5 did not alter hippocampus development unless Foxg1 was also knocked out (Godbole et al., 2018). Pax6 is expressed in a lateral medial gradient in the neocortex, which is opposite to that of Lhx2. In Pax6/Lhx2 DKO, the hippocampus expands more so in the forebrain compared to Lhx2 null mice, suggesting Pax6 also suppresses the formation of hippocampus (Godbole et al., 2017).

Lhx6 and Lhx8 are structurally related and have synergistic functions. Lhx6 shares 75% homology with Lhx8, which is also known as L3 or Lhx7 (Matsumoto et al., 1996; Grigoriou et al., 1998). Both these genes are expressed overlappingly in the MGE but are not expressed in the LGE (Figure 1B). Lhx6 is expressed predominantly in the SVZ and the MZ, whilst Lhx8 is expressed in the MZ (Matsumoto et al., 1996). The expression of both these genes is regulated by Nkx2.1, another homeobox transcription factor that specifies ventral telencephalon development (Sandberg et al., 2016).

Lhx6 has similar functions to Lhx1. Lhx6 promotes expression of receptors that regulate cortical interneuron migration and transcription factors that control interneuron production, thereby regulating these events (Alifragis et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2008; Neves et al., 2013). Tangential migration of GABAergic interneurons from the MGE into the neocortex are blocked in embryonic mice lacking Lhx6; normally these interneurons express Lhx6 in wildtype mice (Lavdas et al., 1999; Alifragis et al., 2004; Liodis et al., 2007). Such migration defects prevent the formation of functional connections between these neurons and their post-synaptic targets. Since Lhx6 has restricted expression in MGE progenitor cells, it does not regulate the migration of all cortical interneurons during development, especially at later stages where tangentially migrating neurons are born in the LGE (Marin et al., 2000; Nery et al., 2002). Production of GABAergic interneurons and their migration within the MGE are not affected in Lhx6 mutants, but interneuron subtype specification is dependent on the expression of Lhx6 (Neves et al., 2013). MGE-derived cortical interneurons are unable to differentiate into sst+ and pva+ subtypes, shown by a drastic reduction in the number of these neurons in Lhx6 null mutants. Lhx6 KOs had a greater effect on sst+ interneuron differentiation than pva+ interneuron differentiation, where pva+ interneuron differentiation was affected restrictively in the hippocampus (Liodis et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2018).

Lhx8, unlike Lhx6, is expressed in cholinergic neurons instead of GABAergic neurons (Lopes et al., 2012). Lhx8 is essential for the differentiation and specification of cholinergic interneurons, shown by the reduction of cholinergic neurons in Lhx8 homozygous mutant mice (Zhao et al., 2003; Fragkouli et al., 2005). Progenitor cells proliferate in Lhx8 homozygous mutant mice; however, they are unable to differentiate into cholinergic interneurons or glutamatergic neurons (Manabe et al., 2007, 2008). Cholinergic neurons are derived from progenitor cells in the MGE, where LHX8 promotes the expression of Isl1 upon cholinergic commitment, which in turn represses Lhx6 expression (Zhao et al., 2003). Lhx8 forms a hexamer with Isl1 and promotes cholinergic neuron expression by binding to specific motifs in the cholinergic enhancer sequence (Park et al., 2012). The formation of hexamers is necessary for DNA binding and subsequently cholinergic gene expression, whilst LHX8 or ISL1 alone does not bind to cholinergic enhancer sequences and are unable to promote cholinergic interneuron differentiation (Cho et al., 2014). NPCs in the striatum differentiate into GABAergic interneurons instead of cholinergic neurons in Lhx8 homozygous mutants. This is due to an upregulation of Lhx6 as a result of a lack of Isl1, suggesting the necessity of Lhx8 in cholinergic neuron specification (Manabe et al., 2005; Bachy and Rétaux, 2006). Additionally, Lhx6 acts cooperatively with Lhx8 to promote shh expression in the MGE, regulating the production of interneuron progenitors, as well as inhibiting Nkx2.1 expression in cortical neurons (Flandin et al., 2011). The Lhx6 and Lhx8/Isl1 regulatory network is therefore essential for regulating the differentiation of GABAergic and cholinergic neurons in the ventral telencephalon.

The LIM-domain transcription factor family is functionally important for the specification, differentiation and migration of neurons in the developing forebrain, and mutations in these genes can result in genetic diseases (Table 3). LHX2 mutations can result in pituitary hormone deficiency, although it is uncommon that a mutation in LHX2 alone can cause pituitary deficiency and developmental ocular abnormalities (Prez et al., 2012). The importance of Lhx6 on the differentiation of interneurons into sst+ and pva+ subtypes have a pathological link to schizophrenia (Volk et al., 2014; Donegan et al., 2020). There is reduced LHX6 expression in schizophrenic subjects who also have reduced expression of GAD1 (otherwise known as GAD67, a GABA synthesizing enzyme), sst, and pva expression. Reduction in GAD1 does not downregulate LHX6 and vice versa; hence, upstream factors likely contribute to the regulation of these genes (Volk et al., 2012). Moreover, a decrease in both GABAergic and cholinergic interneurons in the ventral telencephalon has been reported in Tourette Syndrome, suggesting LHX6 and LHX8 correlation with Tourette Syndrome due to their role in GABAergic and cholinergic interneuron specification in the striatum (Pagliaroli et al., 2020).

Myeloid Ectopic Viral Integration Site 2 Gene

The myeloid ectopic viral integration site (Meis) gene family belongs to the TALE class of homeobox proteins, a homolog of the Drosophila homothorax gene, which is essential for directing the localization of Pbx Drosophila homologue extradenticle (Rieckhof et al., 1997). There are three mammalian MEIS transcription factors (Meis1, Meis2, and Meis3), and all contain a conserved homothorax domain (Figure 2A), which promotes the interaction between MEIS and pre-B cell leukemia homeobox proteins (PBX), a transcription factor known for its regulatory role in organogenesis (Nakamura et al., 1996; Chang et al., 1997; Golonzhka et al., 2015). MEIS proteins are characterized by a three residue loop insertion between helices 1 and 2 of the HD, an important feature for protein-protein interactions (Bürglin, 1997). Out of the three Meis genes, only Meis1 and Mei2 are expressed in the developing telencephalon (Figure 1B). Meis2 in particular is an important player for striatal progenitors and neuron differentiation, as well as postnatal neuronal differentiation in the olfactory bulb (Toresson et al., 1999; Agoston et al., 2014).

Myeloid ectopic viral integration site 2 is expressed in the VZ of the entire telencephalon from E10.5, and is enriched in the LGE compared to the MGE from E12.5 to E18.5 (Figure 1B). From E14.5, MEIS2 is also expressed in the ventral thalamus and the anterior hypothalamus (Cecconi et al., 1997; Toresson et al., 1999, 2000). Additionally, the expression pattern of MEIS2 is similar in the human fetal forebrain, where MEIS2 is expressed in the proliferative zones (Larsen et al., 2010a). In the telencephalon, MEIS2 was initially considered as an LGE-specific marker due to its predominant expression in the LGE; however, MEIS2 is also widely expressed in the CGE progenitors (Toresson et al., 1999; Frazer et al., 2017). Postnatally, interneurons born and derived from the olfactory bulb express MEIS2, as it plays a crucial role, along with other transcription factors, in neuronal differentiation and specification in early postnatal stages (Allen et al., 2007; Agoston et al., 2014).

Myeloid ectopic viral integration site 2 forms complexes with various other transcription factors to cooperatively facilitate the expression of genes required for neurogenesis. As mentioned, MEIS2 interacts with PBX1 proteins and forms heteromeric complexes, which regulate the DNA binding ability of the two transcription factors (Liu et al., 2001; Longobardi et al., 2014). The MEIS2-PBX1 complex further recruits other transcription factors, such as the Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) to modulate MEIS2 transcriptional activities (Bjerke et al., 2011). Other than PBX1, MEIS2 also functions synergistically with HOX and PAX homeobox factors, regulating the gene expression of other targets in the midbrain and hindbrain (Agoston et al., 2012). Mechanisms for the interactions between MEIS2 and other factors have been extensively reviewed; notably, MEIS2 recognizes and binds to a specific DNA motif TGACAG (Table 2; Chang et al., 1997; Longobardi et al., 2014; Schulte, 2014).

Myeloid ectopic viral integration site 2 controls gene expression and promotes neuronal migration and differentiation during forebrain development. There are three types of serotonin receptor 3a expressing (Htr3a+) GABAergic interneurons, which populate different regions of the brain. Type I Htr3a+ are enriched in transcription factors expressed in the LGE, including MEIS2, and these interneurons populate the deep cortical layers (von Engelhardt et al., 2011; Frazer et al., 2017). These interneurons originate from the PSB and migrate through to the cortex, contrasting with other types of Htr3a+ interneurons which are born from the CGE and populate the superficial cortical layers. Ectopic expression of Meis2 in CGE born interneurons resulted in a shift of differentiated Htr3a+ interneurons to the deep cortical layers, indicating that MEIS2 induces the migration of the LGE-derived interneurons (Frazer et al., 2017). Alternatively, MEIS2 can regulate expression of the Dlx family, by interacting with the intergenic enhancers in the Dlx bigenic clusters (Ghanem et al., 2003). MEIS2 binds to the I12b intergenic enhancer of Dlx1/2 and the I56ii intergenic enhancer of Dlx5/6. MEIS2 can activate reporter gene transcription with a I56ii promoter sequence in vitro (Yang et al., 2000; Poitras et al., 2007; Ghanem et al., 2008). Subsequently, the removal of I56ii sequence reduced Meis2 and Dlx5/6 expression, suggesting that there may be a positive feedback loop between MEIS2 and DLX5/6, further regulating interneuron migration (Fazel Darbandi et al., 2016). Furthermore, dopamine receptor expressing (D1/D2) MSNs are promoted by MEIS2 in the LGE, where deletion of Meis2 blocked differentiation of neural progenitors and reduced the medium-spiny neuron population (Su et al., 2022). MEIS2 regulates specification of these striatal projection neurons through the promotion of Zfp503 and Six3 expression, while Meis2 expression itself is regulated by DLX1/2 (Su et al., 2022). Likewise, in the prethalamus, DLX2 drives GABAergic interneuron determination through promoting Meis2 expression, and SOX14 represses Meis2 expression to maintain rostral thalamus identity (Sellers et al., 2014). In postnatal stages, interneurons continue to arise from the olfactory bulb SVZ generated neuroblasts where these differentiation events are dependent on the activity of MEIS2 and its interaction with PAX6 and DLX2 (Ming and Song, 2011; Agoston et al., 2014). Indeed, cKO of Meis2 in the olfactory bulb blocks dopaminergic neuron differentiation, as MEIS2 promotes expression of Dcx and Th, both crucial genes for dopaminergic neuron subtype specification (Agoston et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2020).

Nkx2.1/2.2 Genes

Nkx2.1 and Nkx2.2, homeobox transcription factors of the vertebrate Nkx family, are important for the regulation of embryonic telencephalon and diencephalon patterning (Price et al., 1992; Sussel et al., 1999). Nkx2.1 is the mammalian homolog of the Drosophila scarecrow (scro), and is also known as the thyroid transcription factor 1 and thyroid specific enhancer binding protein, since it also plays a role in thyroid, lung and pituitary development (Guazzi et al., 1990; Mizuno et al., 1991; Kimura et al., 1996; Maurel-Zaffran and Treisman, 2000). Nkx2.2 is homologous to the Drosophila ventral nervous system defective (vnd) gene (Kim and Nirenberg, 1989; Price et al., 1992; Jimenez et al., 1995). Nkx2.1 and Nkx2.2 encode both a HD and a NK2 box domain (Figure 2). In embryonic forebrain, Nkx2.1 is expressed in progenitor and post-mitotic cells in the MGE and PoA, and is essential for the patterning of these areas (Xu et al., 2005). Nkx2.2 is localized to the MGE, the VZ of the thalamus and MZ of the diencephalon; however, Nkx2.2 expression can vary in different mammalian species (Ericson et al., 1997; Flames et al., 2007; Vue et al., 2007; Bardet et al., 2010; Domínguez et al., 2015). The dorsoventral expression pattern of Nkx2.1 (ventral) is complementary to that of Pax6 (dorsal) (Figure 1B). Within the thalamus, Nkx2.2 expression is induced by SHH signaling in the rostral thalamus along with Ascl1, resulting in the specification of GABAergic neurons that populate the thalamus; as a result, Nkx2.2 is often co-expressed with SHH (Briscoe et al., 1999; Vue et al., 2007; Robertshaw et al., 2013).

Nkx2.1 expressing progenitor cells give rise to GABAergic and cholinergic neurons, which populate the neocortex and striatum, respectively (Anderson et al., 2001; Magno et al., 2017). Nkx2.1 expression in the GABAergic interneurons then diminishes after they tangentially migrate toward the neocortex, but is sustained in the cholinergic neurons (Marin et al., 2000). In the MGE, Nkx2.1 silencing is necessary for interneurons to tangentially migrate. Nkx2.1 silencing promotes the expression of Nrp1 and Nrp2, which then initiates neural migration (Nóbrega-Pereira et al., 2008; Kanatani et al., 2015). Nkx2.1 expressing neurons in the hypothalamus tangentially migrate into the diencephalon, and develop into GABAergic interneurons (Murcia-Ramón et al., 2020b). Additionally, NKX2.1 regulates astrocyte differentiation in the MGE and PoA from E14.5 to E16.5 in mice, and oligodendrocyte differentiation from E12.5 (Kessaris et al., 2006; Minocha et al., 2015, 2017; Orduz et al., 2019). Transcriptional activity is dependent on epigenetic states (Attanasio et al., 2014; Sandberg et al., 2016).

Nkx2.1 homozygous mutant mice die at birth with lung, thyroid, pituitary and ventral telencephalon defects (Kimura et al., 1996; Takuma et al., 1998; Sussel et al., 1999). In these mutant mice, the MGE is respecified into LGE, and exhibits reduced numbers of GABAergic and cholinergic neurons (Sussel et al., 1999; Fragkouli et al., 2009). However, ∼50% of GABAergic interneurons remain, suggesting that NKX2.1 is not the sole factor required for GABAergic interneuron specification (Sussel et al., 1999). cKO of Nkx2.1 at E10.5 and E12.5 results in altered identity of the MGE-derived interneurons subtypes. The MGE progenitor cells of these mutants were respecified into calretinin and vasointestinal peptide (VIP) expressing interneuron subtypes, resembling interneuron populations derived from the caudal GE (Xu et al., 2004; Butt et al., 2005), as opposed to pva+ or sst+ subtypes (Butt et al., 2008). GABAergic interneuron differentiation, especially pva+ and sst+ subtypes, is tightly regulated by Lhx6 and Lhx8 in the MGE, and both genes are downstream targets of NKX2.1 (Du et al., 2008; Flandin et al., 2011; Sandberg et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2021). Lhx6 and Lhx8 are activated by NKX2.1 expression in the SVZ through the recognition of epigenetic markers, and are essential for the specification of pva+ and sst+ interneuron subtypes (Du et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2021). Furthermore, NKX2.1 regulates MGE identity through repression of genes in the SHH, Wnt, and BMP signaling pathways required for cell differentiation and patterning. This repression is likely achieved by recruitment of Gro/TLE, a complex that reduces epigenetic-mediated repression, and induces activation (Patel et al., 2012; Sandberg et al., 2016). Conversely, SHH can induce the expression of Nkx2.1 in the MGE to specify ventral identity (Ericson et al., 1995). To establish ventral identity in the telencephalon, NKX2.1 also represses Pax6 expression in the GE, as the Nkx2.1 cKO showed a dorsal to ventral expansion and ectopic expression of Pax6 ventrally (Manoli and Driever, 2014). Pax6, a dorsal telencephalon specifying gene, in turn represses the expression of Nkx2.1 in the neocortex. The existence of this mechanism of mutual repression is supported by the complementary expression patterns of these two transcription factors (Sussel et al., 1999; Stoykova et al., 2000).

As NKX2.1 is essential for formation of various organs, mutations in this gene are linked to multiple phenotypes and diseases, including neurological disease, lung defects and thyroid dysfunction (Table 3; Thorwarth et al., 2014). NKX2.1 may play a role in Hirschsprung disease, a disorder of the developing enteric nervous system, through its interaction with SOX10 and PAX3. Sex-determining factor SRY is reported to displace SOX10’s interaction with NKX2.1 and PAX3, thereby promoting a Hirschsprung disease phenotype (Li et al., 2015). Furthermore, hereditary chorea, also known as brain-lung-thyroid disease, is linked to mutations in NKX2.1 with symptoms such as impaired coordination or speech development (Krude et al., 2002; Monti et al., 2015). Subsequently, NKX2.1 has also been related to the development of schizophrenia, as Nkx2.1 regulates GABAergic and cholinergic neuron specification (Sussel et al., 1999; Fragkouli et al., 2009; Malt et al., 2016). The cholinergic specification function of Nkx2.1 correlates with learning and memory, where the absence of Nkx2.1 in the septal area results in cognitive impairments (Magno et al., 2017).

Orthodenticle Homeobox Genes