- 1Department of Psychiatry, The Coimbra Hospital and University Centre, Coimbra, Portugal

- 2Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Quetiapine in an atypical antipsychotic drug that is frequently used for delirium and behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. However, its potential anticholinergic effects, mediated primarily through its metabolite norquetiapine, could present as counterproductive adverse effects in these situations. There is little data published discussing this potential negative impact on quetiapine’s safety and tolerability, especially in the elderly. Here, we present what is, to our knowledge, the first published case report of delirium apparently induced by low-dose quetiapine, in a 95-year-old patient with no prior history of mental illness, and the potential role of its metabolite norquetiapine.

Introduction

Delirium is an acute disorder of attention and cognition, more frequent in elderly people (i.e., those aged 65 years or older) that is common, serious, costly, under-recognized, and often fatal. Cognitive assessment and history of acute onset of symptoms are necessary for diagnosis. Delirium offers opportunities to elucidate brain pathophysiology – it serves both as a marker of brain vulnerability with decreased reserve and as a potential mechanism for permanent cognitive damage (Inouye et al., 2014). The pathophysiology of delirium remains poorly understood as it involves multifactorial dynamic interactions between a diversity of risk factors, each one increasing the risk of delirium only marginally (Cerejeira et al., 2010). The exact mechanism of how direct brain insults and aberrant stress responses lead to the brain dysfunction is not yet fully understood (Maclullich et al., 2013). Nevertheless, many neurotransmitters are potentially implicated in the pathophysiology of delirium, but cholinergic dysfunction is one of the most frequently linked to delirium pathophysiology (Hshieh et al., 2008), correlates with the adverse effects of anticholinergic drugs (Lauretani et al., 2010), and has been proposed as a “final pathway” to delirium regardless of the initial insult (Trzepacs, 2000). Other hypothesis concerning delirium pathophysiology include oxidative metabolism, dysfunction of other neurotransmitters, abnormal signal transduction, changes in blood-brain barrier permeability, endocrine abnormalities and increased inflammatory response (Maldonado, 2008).

Quetiapine is a widely used atypical antipsychotic, a dibenzothiazepine derivative, available in two different pharmaceutical forms: immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (XR). It is extensively metabolized by the liver into various metabolites and only 1% is excreted in the unmetabolized form, in urine. N-desalkylquetiapine, also known as norquetiapine, is the major active metabolite of quetiapine and is produced by the action of isoenzyme CYP34A in cytochrome P450 (López-Muñoz and Álamo, 2013). As of April 2019, its use is approved by the Food and Drugs Administration and several European regulatory agencies for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (manic and depressive episodes, as well as maintenance treatment) and as add-on treatment in major depressive disorder (MDD). It is used off-label for conditions such as: generalized anxiety disorder, as monotherapy for MDD, as add-on treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder, for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, for psychosis and agitation in dementia, and in low-dose for insomnia (Maglione et al., 2011). It has also been proposed for managing the symptoms of delirium (Hawkins et al., 2013).

As anticholinergic drugs have been implicated in the etiology and pathophysiology of delirium as well as in serious adverse effects in dementia, Anticholinergic Risk Scales (ARS) have been developed from pharmacological and epidemiological studies to guide clinical practice, especially in elderly people. In this field, available studies disagree as to whether quetiapine poses low (Rudolph et al., 2008), (Ehrt et al., 2010), moderate (Han et al., 2008), or high (Boustani et al., 2008) anticholinergic risk.

Materials and Methods

We describe the case of a 95-year-old woman, with no prior cognitive complaints reported by her relatives, who developed delirium after starting quetiapine IR 100 mg at night, for treatment of chronic insomnia. A thorough literature search was performed using PubMed, Medline, Ovid, Embase, and Google Scholar about the existence of other possible cases of delirium induced by quetiapine in the circumstances we describe, without finding similar cases. A review of cases in different circumstances of delirium associated with quetiapine was made, as well as review of the pharmacological properties of quetiapine and norquetiapine.

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Case Presentation

Mrs. I, a 95-year-old woman with no prior history of mental illness, presented to the emergency room (ER) in the afternoon of the 12th March 2018 with a syndrome characterized by confusion and marked psychomotor agitation, with a fluctuating course and sudden onset 2 days before. She had previous, non-recent, diagnoses of hypertension, trigeminal neuralgia and anemia, and for that she was regularly on enalapril 5 mg/day, carbamazepine 200 mg/day, iron sulfate 329.7 mg/day and folate 5 mg/day. She had had a hip fracture in 2017 that was already fully consolidated and had been treated in January 2018 for heart failure – in these episodes, she seems to have developed some symptoms of delirium (fluctuating disorientation, for example), but there was no need for specialized psychiatric observation. She was also recently medicated (1 months before) with diazepam 10 mg at night and (3 days before) with quetiapine IR 100 mg at night, prescribed by her general practitioner due to complaints of chronic insomnia, reported by relatives after they started taking care of the patient after her hip fracture.

Physical and neurological examinations were unremarkable and there where no signs or symptoms of pain or respiratory distress. A complete blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, glucose, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were also unremarkable. An electrocardiogram and a urine test strip were also unremarkable. After that, she was observed by a psychiatrist, who recommended risperidone 0.5 mg/day and that she kept taking diazepam and quetiapine as before.

That night, and after administering risperidone 0.5 mg, quetiapine 100 mg, and diazepam 10 mg, her relatives brought her back to the ER for increased agitation and maintained confusion, with temporal disorientation. The physical examination was again unremarkable. Complete blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver functions tests, glucose and CRP were again asked for and unremarkable. Another urine test strip was also negative for nitrites, leucocytes or blood. As there was no signs of infection or pain, she was again observed by a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist noted temporal and spatial disorientation, incoherent speech and apparent visual hallucinations. A computed tomography (CT scan) of the head was then performed, which showed no signs of recent intracranial lesions. Of note, there were only bilateral inferior lenticular hypodensities, suggestive of enlarged perivascular spaces, but no signs of leucoencephalopathy or cortical atrophy. Meanwhile, in spite of going against standard clinical practice, a total of 20 mg of haloperidol (intramuscular) were administered throughout 2 days while under observation by several ER teams, due to severe behavioral disturbance, visual hallucinations and refusal to take medication.

In the absence of any neurological or systemic illness which could explain the sudden onset of the symptoms described, the psychiatrist reviewed the patient’s history with the patient’s relatives. A chronological sequence was made clear, with onset of symptoms the day after the patient started quetiapine 100 mg at night. A formal diagnosis of delirium induced by quetiapine was made (meeting criteria established in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) and due to the severity of behavioral disturbance, the patient was committed to the Psychiatry ward. Here, quetiapine, risperidone and diazepam were stopped, and she was medicated by the psychiatrist in charge of her case with haloperidol 3 mg/day and clonazepam 0.5 mg/day. After 6 days, she was discharged with no remarkable signs or symptoms at mental state examination and no apparent cognitive deficits.

Discussion

Previous Case Reports and Case Series of Delirium Associated With Quetiapine

Reports of quetiapine-induced delirium are rare, contrasting with the extensive data available on other antipsychotics and antidepressants with anticholinergic profiles. Here follows a review of the available case reports and case series on this issue.

Sim et al. (2000), reported the case of a 62-year-old man with schizophrenia who, 3 days after starting quetiapine at a dose of 600 mg/day, developed signs and symptoms of inattention, visual illusions and sleep-wake reversal. An EEG was performed and showed generalized slowing suggestive of metabolic encephalopathy. The symptoms resolved 48 h after stopping quetiapine.

In Balit et al. (2003) published a case series of 45 patients who had overdosed on quetiapine. 3 developed delirium after taking 4–12 g of quetiapine alone and, of these, 2 had to be placed in an intensive care unit (ICU). There was another case report of delirium induced by quetiapine overdose by Alexander (2009), describing the case of a 23-year-old woman who had taken 12 g of quetiapine. Finally, regarding reports of delirium linked to quetiapine overdose, Rhyee et al. (2010) reported the case of a 15-year-old adolescent girl who had overdosed on unknown amounts of quetiapine, clonidine, trazodone and risperidone and responded partially to administration of physostigmine after a tentative diagnosis of anticholinergic delirium attributable to quetiapine was made.

More recently, Miodownik et al. (2008) a case of delirium induced by combined treatment with lithium and quetiapine of a patient with schizoaffective disorder, but the hypothesis presented by the authors to explain this case is of a pharmacodynamic interaction between quetiapine and lithium that increases the brain concentration of the former. Later, in Huang and Wei (2010) present the hypothesis of anticholinergic delirium to explain two cases of delirium in patients with bipolar disorder who had started combinations of quetiapine (a single dose of 100 mg in the first case and 300 mg/day in the second) and sodium valproate (1000 mg/day in both cases). The patients were 53 and 63-year-old and both had mild renal insufficiency secondary to long-term lithium treatment. In this report, the proposed mechanism for delirium was a direct anticholinergic effect of quetiapine or a synergistic effect of quetiapine and sodium valproate in the presence of mild renal insufficiency, that could have increased serum concentrations of quetiapine.

From our review, there are no other reports of delirium linked to quetiapine. However, we found reports of clear anticholinergic side effects in patients taking quetiapine, such as urinary retention (Dharmarajan et al., 2017).

Norquetiapine as a Putative Mediator of Anticholinergic Side Effects

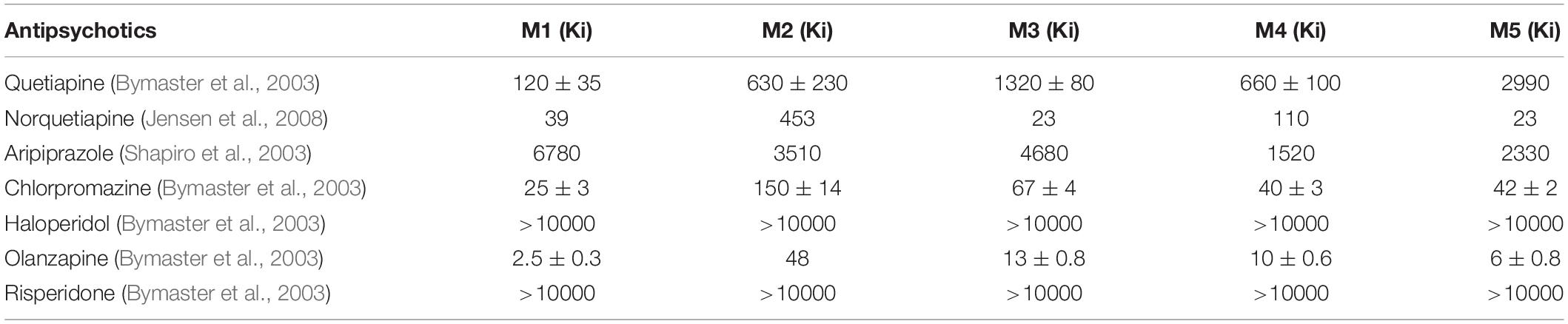

Receptor binding affinities studies (Bymaster et al., 2003; Shapiro et al., 2003; Jensen et al., 2008), shown on Table 1, are helpful when comparing the muscarinic antagonism potencies of several frequently used antipsychotics – although there are other important variables, such as ligand residence time. From these, unmetabolized quetiapine seems to have limited anticholinergic properties. Nevertheless, quetiapine is extensively metabolized in the liver and 20 metabolites have been identified. The major active metabolite is N-Desalkylquetiapine, or norquetiapine, which has been implicated in the clinical effects of quetiapine. Jensen et al. (2008), for example, proposed that its unique properties as a potent norepinephrine reuptake transporter and partial 5-HT1A might mediate quetiapine’s efficacy in depression, but also described medium- to high-affinity to muscarinic receptors as an antagonist, contrasting with quetiapine is this regard.

Table 1. Binding affinity of atypical and typical antipsychotic drugs for human muscarinic receptors in clonal cells (Ki – ligand binding affinity, expressed as maximal receptor occupancy according to ligand concentration, in nM).

Norquetiapine is produced by the CYP3A4 isoform metabolization of quetiapine but is, is turn, primarily metabolized by the CYP2D6 isoform (Bakken et al., 2012). It is interesting to note that carbamazepine, which was part of the patient’s regular medication described in this case report, is a strong inducer of CYP3A4 but not of CYP2D6 (Lynch and Price, 2007) and that its specific action promoting the metabolization of quetiapine to norquetiapine has been described (Grimm et al., 2006).

As we have seen, anticholinergic risk studies have been inconsistent as to whether quetiapine present a low-, moderate- or high-risk, in spite of having been linked to greater cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease by Ballard et al. (2005) The pharmacokinetic variability of quetiapine in patients has been established and also correlated with age and CYP3A4 inducers (Bakken et al., 2011), as well as tentatively linked to therapeutic effects (Rovera et al., 2017). We could not find studies associating this variability with the incidence of side effects as there are regarding therapeutic effects.

Our hypothesis for the case described in this paper is that delirium was made much more likely by a pre-existing vulnerability – due to the patient’s advanced age and comorbidities, recent episodes with symptoms of delirium and prescription of diazepam – but that a tipping point was reached after the introduction of quetiapine, whose metabolization to norquetiapine, a more potent muscarinic antagonist, is promoted by carbamazepine, with which the patient was also medicated.

Conclusion

With this report, we aim to draw attention to a cluster of potential side effects of quetiapine, which have been overlooked by available studies. We suggest that variability in quetiapine’s conversion to norquetiapine could be one of the factors involved in the inconsistency of reports regarding quetiapine’s side effects due to its anticholinergic action. Individual patient characteristics and drug interactions contribute to this variability and should be accounted for when assessing anticholinergic risk profiles.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Author Contributions

FA performed the review, wrote the manuscript, and incorporated feedback from all co-authors. EA and IM contributed substantially to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors had given the final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alexander, J. (2009). Delirium as a symptom of quetiapine poisoning. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 43, 781–781. doi: 10.1080/00048670903001950

Bakken, G. V., Molden, E., Knutsen, K., Lunder, N., and Hermann, M. (2012). Metabolism of the active metabolite of quetiapine, N-desalkylquetiapine in vitro. Drug Metab. Dispos. 40, 1778–1784. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.045237

Bakken, G. V., Rudberg, I., Molden, E., Refsum, H., and Hermann, M. (2011). Pharmacokinetic variability of quetiapine and the active metabolite N-desalkylquetiapine in psychiatric patients. Ther. Drug Monit. 33, 222–226. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31821160c4

Balit, C. R., Isbister, G. K., Hackett, L. P., and Whyte, I. M. (2003). Quetiapine poisoning: a case series. Ann. Emerg. Med. 42, 751–758.

Ballard, C., Margallo-Lana, M., Juszczak, E., Douglas, S., Swann, A., Thomas, A., et al. (2005). Quetiapine and rivastigmine and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 330:874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38369.459988.8f

Boustani, M., Campbell, N., Munger, S., Maidment, I., and Fox, C. (2008). Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. Aging Health 4, 311–320. doi: 10.2217/1745509x.4.3.311

Bymaster, F. P., Felder, C. C., Tzavara, E., Nomikos, G. G., Calligaro, D. O., Mckinzie, D. L., et al. (2003). Muscarinic mechanisms of antipsychotic atypicality. Prog. NeuroPsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 27, 1125–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.008

Cerejeira, J., Firmino, H., Vaz-Serra, A., and Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. B. (2010). The neuroinflammatory hypothesis of delirium. Acta Neuropathol. 19, 737–754. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0674-1

Dharmarajan, T. S., Kanagala, K., and Lebelt, A. (2017). Quetiapine induced urinary dysfunction: an adverse anticholinergic effect needing recognition. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18:B6.

Ehrt, U., Broich, K., Larsen, J. P., Ballard, C., and Aarsland, D. (2010). Use of drugs with anticholinergic effect and impact on cognition in Parkinson’s disease: a cohort study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 81, 160–165. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.186239

Grimm, S. W., Richtand, N. M., Winter, H. R., Stams, K. R., and Reele, S. B. (2006). Effects of cytochrome P450 3A modulators ketoconazole and carbamazepine on quetiapine pharmacokinetics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 61, 58–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02507.x

Han, L., Agostini, J. V., and Allore, H. G. (2008). Cumulative anticholinergic exposure is associated with poor memory and executive function in older men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 56, 2203–2210. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02009.x

Hawkins, S. B., Bucklin, M., and Muzyk, A. J. (2013). Quetiapine for the treatment of delirium. J. Hosp. Med. 8, 215–220. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2019

Hshieh, T. T., Fong, T. G., Marcantonio, E. R., and Inouye, S. K. (2008). Cholinergic deficiency hypothesis in delirium: a synthesis of current evidence. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63, 764–772. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.7.764

Huang, C.-C., and Wei, I. H. (2010). Unexpected interaction between quetiapine and valproate in patients with bipolar disorder. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 32, 446.e1–446.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.06.005

Inouye, S. K., Westendorp, R. G. J., and Saczynski, J. S. (2014). Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 383, 911–922. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60688-1

Jensen, N. H., Rodriguiz, R. M., Caron, M. G., Wetsel, W. C., Rothman, R. B., Roth, B. L., et al. (2008). N-desalkylquetiapine, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and partial 5-HT 1A agonist, as a putative mediator of quetiapine’s antidepressant activity. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 2303–2112.

Lauretani, F., Ceda, G. P., Maggio, M., Nardelli, A., Saccavini, M., and Ferrucci, L. (2010). Capturing side-effect of medication to identify persons at risk of delirium. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 22, 456–458. doi: 10.1007/bf03324944

López-Muñoz, F., and Álamo, C. (2013). Active metabolites as antidepressant drugs: the role of norquetiapine in the mechanism of action of quetiapine in the treatment of mood disorders. Front. psychiatry 4:102. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00102

Lynch, T., and Price, A. (2007). The effect of cytochrome P450 metabolism on drug response, interactions, and adverse effects. Am. Fam. Physician 76, 391–396.

Maclullich, A. M. J., Anand, A., Davis, D. H., Jackson, T., Barugh, A. J., Hall, R. J., et al. (2013). New horizons in the pathogenesis, assessment and management of delirium. Age Ageing 42, 667–674. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft148

Maglione, M., Ruelaz Maher, A., Hu, J., Wang, Z., Shanman, R., and Shekelle, P. G. (2011). “Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43,” in Prepared by the Southern California Evidence-based Practice Center Under Contract No. HHSA290-2007-10062-1, (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.).

Maldonado, J. R. (2008). Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit. Care Clin. 24, 789–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.06.004

Miodownik, C., Alkatnany, A., Frolova, K., and Lerner, V. (2008). Delirium associated with lithium-quetiapine combination. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 31, 176–179. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31814a619d

Rhyee, S. H., Pedapati, E. V., and Thompson, J. (2010). Prolonged delirium after quetiapine overdose. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 26, 754–756. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181f39d5b

Rovera, C., Mauri, M. C., Di Pace, C., Paletta, S., Reggiori, A., Ciappolino, V., et al. (2017). Effect of N-Desalkylquetiapine/quetiapine plasma level ratio on anxiety and depression in bipolar disoder: a prospective observational study. Ther. Drug Monit. 39, 441–445. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000413

Rudolph, J. L., Salow, M. J., Angelini, M. C., and McGlinchey, R. E. (2008). The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 168, 508–513. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106

Shapiro, D. A., Renock, S., Arrington, E., Chiodo, L. A., Liu, L. X., Sibley, D. R., et al. (2003). Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 1400. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203

Sim, F. H., Brunet, D. G., and Conacher, G. N. (2000). Quetiapine associated with acute mental status changes. Can. J. Psychiatry 45, 299–299.

Keywords: delirium, quetiapine, anticholinergic, antipsychotics, adverse effects

Citation: Almeida F, Albuquerque E and Murta I (2019) Delirium Induced by Quetiapine and the Potential Role of Norquetiapine. Front. Neurosci. 13:886. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00886

Received: 30 April 2019; Accepted: 07 August 2019;

Published: 20 August 2019.

Edited by:

Angel L. Montejo, University of Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Josef Jenewein, Psychiatric Clinic Zugersee, SwitzerlandSubho Chakrabarti, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), India

Soenke Boettger, University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland

Copyright © 2019 Almeida, Albuquerque and Murta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Filipe Almeida, Zi5mZWxpeC5hbG1laWRhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Filipe Almeida

Filipe Almeida Elisabete Albuquerque1

Elisabete Albuquerque1