- 1Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Neural processing of speech production has been traditionally attributed to the left hemisphere. However, it remains unclear if there are structural bases for speech functional lateralization and if these may be partially explained by sexual dimorphism of cortical morphology. We used a combination of high-resolution MRI and speech-production functional MRI to examine cortical thickness of brain regions involved in speech control in healthy males and females. We identified greater cortical thickness of the left Heschl’s gyrus in females compared to males. Additionally, rightward asymmetry of the supramarginal gyrus and leftward asymmetry of the precentral gyrus were found within both male and female groups. Sexual dimorphism of the Heschl’s gyrus may underlie known differences in auditory processing for speech production between males and females, whereas findings of asymmetries within cortical areas involved in speech motor execution and planning may contribute to the hemispheric localization of functional activity and connectivity of these regions within the speech production network. Our findings highlight the importance of consideration of sex as a biological variable in studies on neural correlates of speech control.

Introduction

Speech production is a complex motor behavior that requires the involvement of several brain regions and their respective networks, which collectively support different aspects of auditory and phonological processing, sensorimotor integration (SMG), executive function, motor planning and execution (Simonyan and Fuertinger, 2015). Contrary to the empirical notion of left-hemispheric lateralization of brain activity during speech production, several recent studies defined a bilateral functional and structural distribution of the large-scale speech network (Simonyan et al., 2009; Morillon et al., 2010; Gehrig et al., 2012; Silbert et al., 2014; Simonyan and Fuertinger, 2015; Kumar et al., 2016). Within this network, a hemispheric lateralization of functional activity and connectivity was found to be a feature of selected brain regions and their subnetworks. While these studies refined our understanding of the hemispheric lateralization of speech production, its potential physiological underpinnings remain poorly understood. A recent multimodal study combining functional MRI (fMRI), intracranial electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings and large-scale neural population simulations based on diffusion-weighted MRI has demonstrated a direct modulatory role of dopaminergic neurotransmission on a functional lateralization of nigro-striatal and nigro-motocortical pathways involved in speech production (Fuertinger et al., 2018). Given the previous reports of sex differences in perceptual aspects of speech and language neural representations (Binder et al., 1995; Frost et al., 1999; Kansaku and Kitazawa, 2001; Clements et al., 2006), it is plausible to assume that another factor contributing to cortical hemispheric lateralization during speech production may be rooted in sex-specific differences of structural brain organization. Along these lines, it has been suggested that females have a more bilateral language representation, while language processing is mostly left-lateralized in males (McGlone, 1980; Dorion et al., 2000; Gur et al., 2000). For example, males show left-hemispheric activation during phonological tasks, while females show largely bilateral activity (Shaywitz et al., 1995). Male stroke patients have been reported to exhibit verbal impairments more frequently after lesions of the left hemisphere than females (McGlone, 1980; Hier et al., 1994), although sex differences were not replicated in other stroke studies involving unilateral lesions (Basso, 1992; Pedersen et al., 1995, 2004). Several studies, including large meta-analyses, have also failed to identify sex-specific differences in brain lateralization (Binder et al., 1995; Frost et al., 1999; Kansaku and Kitazawa, 2001; Sommer et al., 2004; Kitazawa and Kansaku, 2005; Clements et al., 2006; Wallentin, 2009; Kong et al., 2018). However, it should be noted that these studies have primarily focused on perceptual and cognitive aspects of speech and language processing and have not specifically examined the motor aspects of speech control. Inconsistencies in findings might also stem from high functional heterogeneity that characterizes large atlas-based macroanatomic labels as used in previous studies. Therefore, to circumvent these limitations and to focus on the speech production system, we examined the presence of sex differences in cortical thickness (CT) in brain regions that are functionally active during real-life speech production in healthy males and females. We hypothesized that hemispheric lateralization of regional brain activity during speech production may, in part, be explained by sex-specific asymmetry in cortical morphology within the speech controlling network.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

A total of 109 subjects participated in the study, including 59 healthy females (mean age 50.4 ± 10.5 years) and 50 age-matched healthy males (mean age 51.9 ± 9.3 year). All subjects were monolingual native English speakers, right-handed as determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971), had normal cognitive performance and lexical verbal fluency as determined by the Mini-Mental State Examination (Cummings, 1993), and had no history of speaking, hearing, psychiatric or neurological problems. There were no differences in mean age and the education level between the male and female groups (p > 0.46). This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Internal Review Board of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Image Acquisition

All subjects underwent high-resolution MRI on 3.0 T Philips scanner with an 8-channel Sense head coil. An anatomical scan was acquired in all subjects using a T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence (flip angle = 8°, TR = 7.5 ms, TE = 2 ms, FOV = 210 × 210 mm2, 172 slices with an isotropic voxel size of 1 mm3). Among these, 16 females (mean age 50.9 ± 9.6 years) and 13 age-matched males (mean age 52.3 ± 9.0 years) participated in an additional whole-brain fMRI scan using a gradient-weighted echo planar imaging (EPI) pulse sequence and blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) contrast (TR = 10.6 s, including an 8.6 s delay for listening to and production of the task and 2 s for image acquisition, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, 36 contiguous slices, slice thickness = 4 mm, matrix size = 64 × 64 mm, FOV = 240 × 240 mm2). A sparse-sampling event-related fMRI design was used to minimize scanner noise, task-related acoustic interferences, and orofacial motion (Gracco et al., 2005; Blackman and Hall, 2011; Adank, 2012).

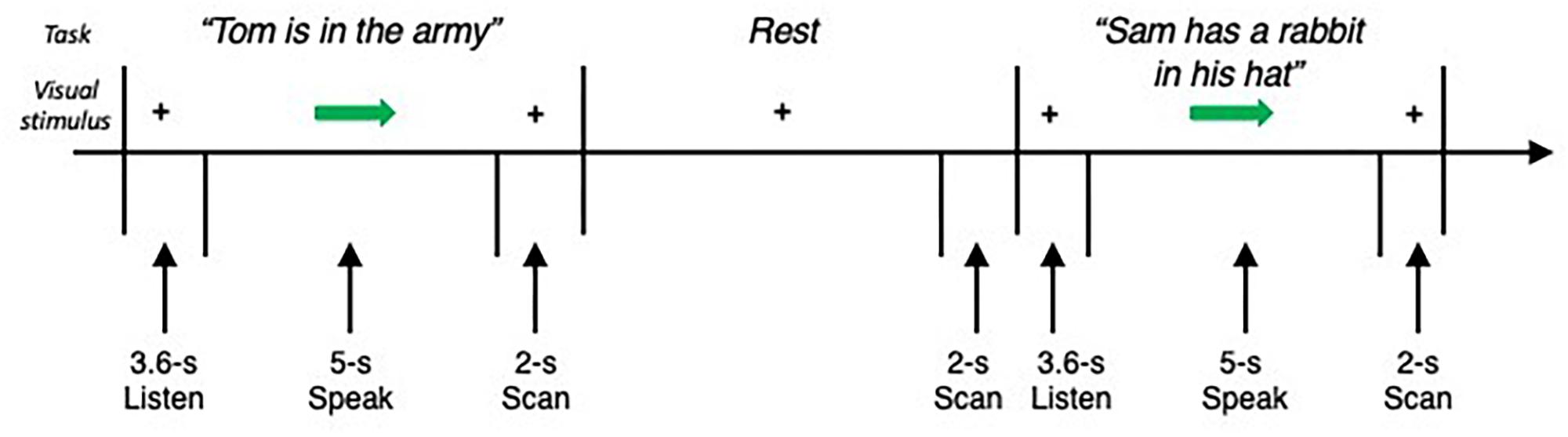

Subjects were instructed to listen to an auditory sample of eight different English sentences (e.g., “Jack ate eight apples,” “Tom is in the army”) delivered one at a time by the same female native English speaker through MR-compatible headphones within a 3.6 s period. When cued by an arrow, subjects produced the task (i.e., repeated the sentence once) within a 5 s period, which was followed by a 2 s whole-brain volume acquisition (Figure 1). Rest periods without any auditory input or task production were incorporated as a baseline condition. Each subject completed four functional runs, consisting of 24 task and 16 resting conditions.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the experimental fMRI design. The subject fixated on the cross and listened to the acoustically presented sentence for a 3.6-s period. Sentences were pseudorandomized and presented one at a time. No stimulus was presented for the baseline resting condition, during which the subject fixated on the cross. An arrow cued the subject to initiate the task production within a 5-s period, which was followed by a 2-s period of image acquisition.

Image Processing

Anatomical MRI

Whole-brain T1-weighted images were analyzed using the automated “recon-all” function implemented in FreeSurfer software. Briefly, the processing included motion correction, intensity normalization, skull-stripping, volumetric registration with labeling, tissue segmentation, and gray-white interface and pial surface delineation. Cortical parcellation was performed using the Destrieux atlas, which assigned neuroanatomical labels to each location on the cortical surface while incorporating geometric information derived from the subject’s cortical model (Fischl, 2012). All cortical parcellations were visually inspected for accuracy and, if necessary, corrected manually.

Functional MRI

Image analysis was performed using the standard afni_proc.py pre-processing pipeline in AFNI software, which included removal of spikes, registration, alignment of the EPI volume to the anatomical scan, spatial normalization to the AFNI standard Talairach-Tournoux space, spatially smoothed with a 4-mm Gaussian filter, scaling of each run mean to 100 for each voxel, and motion scrubbing. A task regressor was convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function and entered into a multiple regression model to predict the observed BOLD response during speech production. Group analysis was carried out using a two-sided one-sample t-test. The statistical threshold was set at a voxel-wise and cluster-wise corrected p ≤ 0.001, with minimal cluster size of 100 voxels using AFNI’s 3dClustSim.

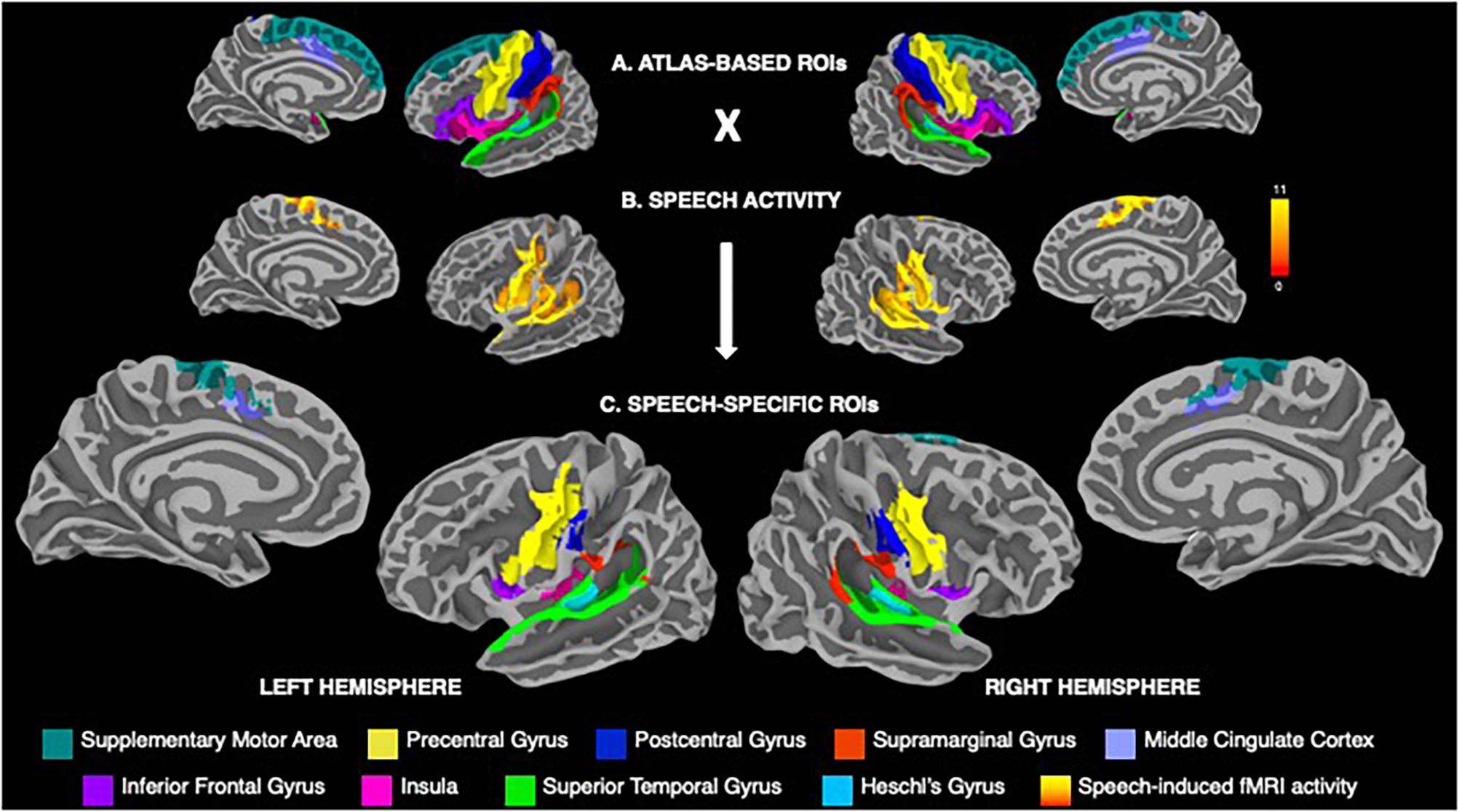

Cortical Regions-of-Interest

Consistent with the previous studies of neural activity during speech production (e.g., Tourville and Guenther, 2003; Simonyan and Fuertinger, 2015; Simonyan et al., 2016; Basilakos et al., 2018; Kearney and Guenther, 2019), the cortical regions-of-interest (ROIs) included the precentral, postcentral and inferior frontal gyri, supplementary motor area, middle cingulate cortex, supramarginal (SMG), superior temporal (STG) and Heschl’s gyri, and insula (Figure 2A). Following the extraction of parcellated Destrieux atlas-based ROIs, a further delineation of these regions included their restriction to areas activate during speech production (Figure 2B). For this, the group mean activity map during speech production was binarized, warped into MNI space using AFNI’s 3dWarp, transformed from the volumetric space to the surface space using AFNI’s 3dVol2Surf and conjoined with atlas-based ROIs, resulting in speech-specific cortical ROIs (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. (A) Visualization of atlas-based anatomical regions-of-interest (ROIs) within the speech production network based on the Destrieux atlas parcellation, including the precentral, postcentral and inferior frontal gyri, supplementary motor area, middle cingulate cortex, supramarginal, superior temporal and Heschl’s gyri, and the insula. (B) Group statistical map of whole-brain activation during speech production across males and females. Color bar represents the t-score at p ≤ 0.001. (C) Speech-specific cortical ROIs derived from conjoining the atlas-based anatomical ROIs with the binarized map of speech-related brain activity. The ROIs are color-coded based on their anatomical affiliation and displayed on the FreeSurfer average template.

In each subject, the mean CT measure was extracted from each speech-specific cortical ROI using Freesurfer’s mri_segstats. Multivariate analysis of covariance, accounting for age as a covariate, was used to examine between-group differences in CT measures within each right and left hemisphere. Separately, within-group differences in CT measures between hemispheres were examined using paired t-tests. Statistical significance was Bonferroni-corrected by the number of ROIs used in the analysis and set at p < 0.005.

Results

Both males and females exhibited a typical pattern of cortical activity during speech production, which involved primary sensorimotor, premotor, inferior frontal, middle cingulate, auditory, inferior parietal and insular regions (Figure 2A), in agreement with other studies investigating speech production (e.g., Tourville and Guenther, 2003; Fuertinger et al., 2015; Simonyan et al., 2016; Basilakos et al., 2018; Kearney and Guenther, 2019). For further analysis, this activity was restricted to the a priori delineated cortical structural ROIs, as outlined above and illustrated in Figure 2.

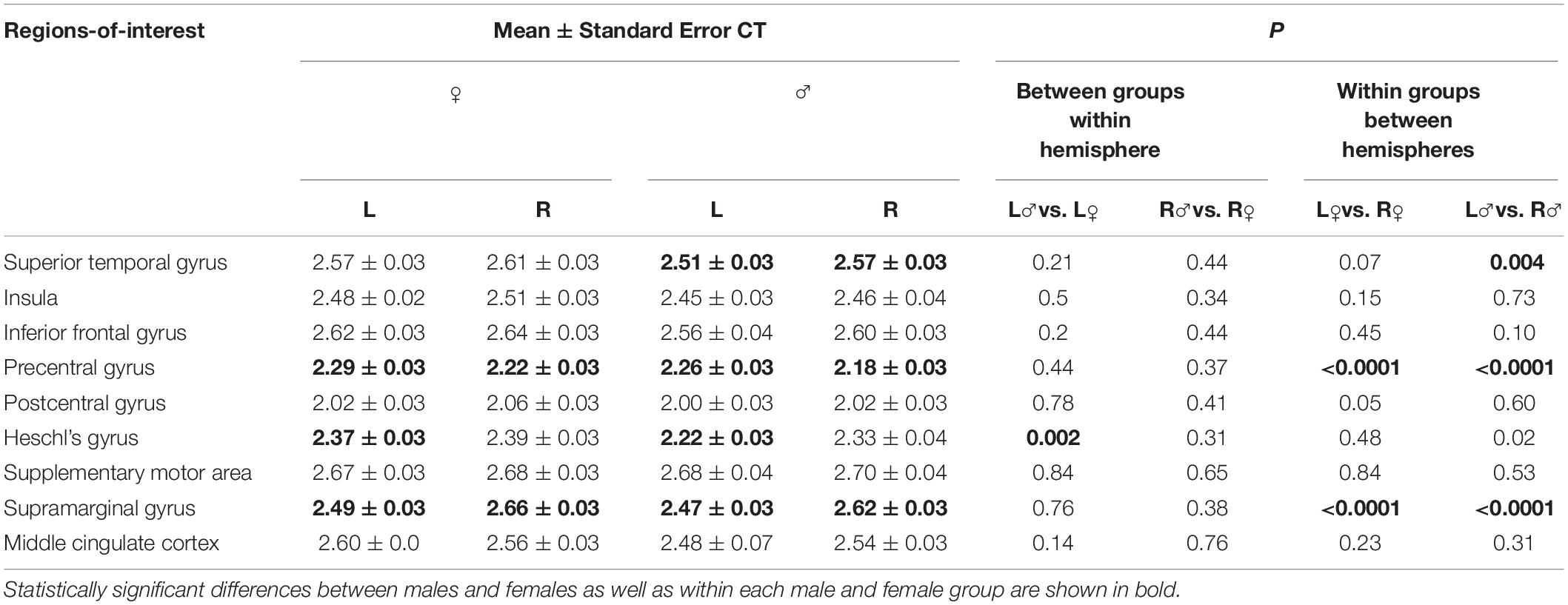

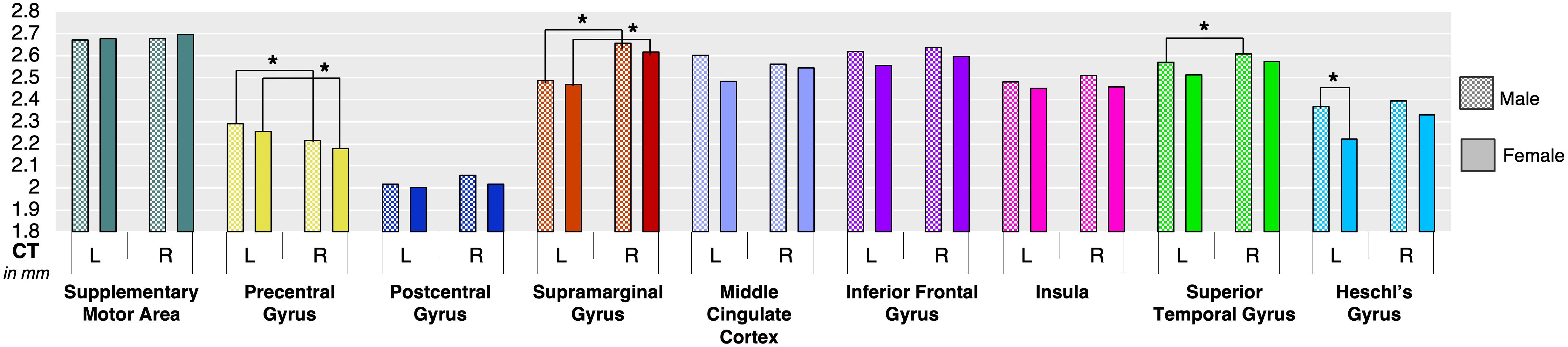

Analysis of regional CT showed that females had significantly greater left Heschl’s gyrus compared to males (p = 0.002) (Figure 3 and Table 1). None of other cortical regions showed significant differences in CT between the male and female groups (p ≥ 0.11).

Figure 3. Boxplot shows mean cortical thickness (in mm) and standard error in each speech-specific cortical region-of-interest in males and females. Asterisk (*) depicts statistically significant differences between males and females as well as within each male and female group.

However, within each group, both females and males exhibited left-hemispheric asymmetry of precentral gyrus (p ≤ 0.001) and right-hemispheric asymmetry of SMG (p ≤ 0.001). In addition, males showed right-hemispheric asymmetry of STG (p = 0.004) (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated the presence of speech-specific sexual dimorphism in CT of primary auditory cortex within the Heschl’s gyrus. In addition, structural hemispheric asymmetry both in males and females was identified in selected brain regions controlling speech motor execution (precentral gyrus), auditory processing (STG) and sensorimotor integration (SMG).

Auditory cortex within the Heschl’s gyrus is known to encode short-latency temporal features of auditory stimuli that have repetition rates within the range of the fundamental frequency of human voice (Belin et al., 1998; Price, 2000; Zatorre, 2001; Scott and Wise, 2004; Brugge et al., 2008, 2009; Warrier et al., 2009; Chevillet et al., 2011; Nourski and Brugge, 2011; Kusmierek et al., 2012). Distinct functional parcellations of core and non-core auditory areas within the Heschl’s gyrus process natural human vocalizations and pitch perturbations in the auditory feedback (Behroozmand et al., 2016). Earlier lesion studies have demonstrated that damage to the left auditory cortex often results in deficits of temporal processing, manifesting as a speech disorder (Damasio and Damasio, 1980; Phillips and Farmer, 1990). Along these lines, our finding of greater CT in the left Heschl’s gyrus in females than males suggests that structural enhancement of this region might be associated with sex-specific differences in processing of auditory cues during speech production as well as contribute to increased prevalence of speech and language developmental disorders in males (Shriberg and Kwiatkowski, 1994; Law et al., 1998; Keating et al., 2001).

We further found between-hemispheric rightward asymmetry of the STG in males but not females. This finding is in line with earlier studies that suggest the influence of genes involved in steroid hormone receptor activity in this region. Specifically, testosterone and progesterone may exert opposing effects on the STG structural organization by promoting its rightward asymmetry in males and forging its structural symmetry in females, respectively (Geschwind and Galaburda, 2003; Guadalupe et al., 2015). This is consistent with the hypothesis that region-specific sexual dimorphisms might be related to factors affecting in utero and early postnatal sexual differentiation of the neural system (Goldstein, 2001).

In both males and females, a characteristic feature of CT organization within the speech production network was its rightward asymmetry of the SMG and leftward asymmetry of the precentral gyrus, encompassing primary motor and premotor cortical areas. The SMG is involved in higher-order processing and plays an important role in the coordination of speech-motor learning, sensorimotor adaptation, phonological decisions, auditory error recognition, and speech onset monitoring (Price et al., 1997; McDermott et al., 2003; Shum et al., 2011; Sliwinska et al., 2012; Deschamps et al., 2014; Kort et al., 2014; Fuertinger et al., 2015). In line with a recent study showing involvement of the right SMG in the prosodic and paralinguistic aspects of speech production (Lindell, 2006), our results suggest that rightward asymmetry of this region may be important for higher-order integration of phonological processing in both males and females. Similarly, leftward CT asymmetry in the precentral gyrus, specifically encompassing its speech motor cortex, may be linked to the general left-hemispheric dominance of this region in the fulfillment of motor tasks in right-handed males and females. This finding also substantiates the left-hemispheric dominance of functional network originating from the laryngeal motor cortex (Lindell, 2006; Simonyan et al., 2009).

Putting the current findings in context with the previous literature, it is important to note that earlier investigations of CT asymmetry have used large atlas-based brain regions that were not confined to speech-related brain activity. This might have led to the mixed reports of both left- and right-hemispheric lateralization of the precentral gyrus and STG in both males and females (Luders et al., 2006; Guadalupe et al., 2015; Kong et al., 2018). Additionally, some studies have reported left-hemispheric asymmetry of CT and regional surface area in the SMG (Lyttelton et al., 2009; Koelkebeck et al., 2014; Plessen et al., 2014; Maingault et al., 2016), while others have found no such differences in this region (Luders et al., 2006; Koelkebeck et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2018). While these inconsistencies might indicate the absence of population-level CT asymmetries (Kong et al., 2018), they may also stem from a failure to account for sex differences in structural organization of the speech production network.

In summary, this study provides evidence for the existence of sex-specific structural dimorphisms within the cortical speech production circuitry. Our findings highlight the importance of the inclusion of sex as a biological variable in research on neural correlates of speech control. Furthermore, our data suggest that examination of speech-specific cortical morphology benefits from restricting analysis to anatomical areas that are functionally active during this complex behavior.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Internal Review Board of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Internal Review Board of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

Author Contributions

KS collected the data. KS, LdLX, and SH designed the study and statistical methods. KS critically reviewed the manuscript and obtained funding. LdLX and SH analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health (grants R01DC011805 and R01DC012545 to KS).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adank, P. (2012). Design choices in imaging speech comprehension: an activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis. Neuroimage 63, 1601–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.027

Basilakos, A., Smith, K. G., Fillmore, P., Fridriksson, J., and Fedorenko, E. (2018). Functional characterization of the human speech articulation network. Cereb. Cortex 28, 1816–1830. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx100

Basso, A. (1992). Prognostic factors in aphasia. Aphasiology 6, 337–348. doi: 10.1080/02687039208248605

Behroozmand, R., Oya, H., Nourski, K. V., Kawasaki, H., Larson, C. R., Brugge, J. F., et al. (2016). Neural correlates of vocal production and motor control in human heschl’s gyrus. J. Neurosci. 36, 2302–2315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3305-14.2016

Belin, P., Zilbovicius, M., Crozier, S., Thivard, L., Fontaine, A., Masure, M. C., et al. (1998). Lateralization of speech and auditory temporal processing. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 10, 536–540.

Binder, J. R., Rao, S. M., Hammeke, T. A., Frost, J. A., Bandettini, P. A., Jesmanowicz, A., et al. (1995). Lateralized human brain language systems demonstrated by task subtraction functional magnetic resonance imaging. Arch. Neurol. 52, 593–601. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540300067015

Blackman, G. A., and Hall, D. A. (2011). Reducing the effects of background noise during auditory functional magnetic resonance imaging of speech processing: qualitative and quantitative comparisons between two image acquisition schemes and noise cancellation. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, 693–704. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0143)

Brugge, J. F., Nourski, K. V., Oya, H., Reale, R. A., Kawasaki, H., Steinschneider, M., et al. (2009). Coding of repetitive transients by auditory cortex on heschl’s gyrus. J. Neurophysiol. 102, 2358–2374. doi: 10.1152/jn.91346.2008

Brugge, J. F., Volkov, I. O., Oya, H., Kawasaki, H., Reale, R. A., Fenoy, A., et al. (2008). Functional localization of auditory cortical fields of human: click-train stimulation. Hear. Res. 238, 12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.11.012

Chevillet, M., Riesenhuber, M., and Rauschecker, J. P. (2011). Functional correlates of the anterolateral processing hierarchy in human auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 31, 9345–9352. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1448-11.2011

Clements, A. M., Rimrodt, S. L., Abel, J. R., Blankner, J. G., Mostofsky, S. H., Pekar, J. J., et al. (2006). Sex differences in cerebral laterality of language and visuospatial processing. Brain Lang. 98, 150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.04.007

Damasio, H., and Damasio, A. R. (1980). The anatomical basis of conduction aphasia. Brain 103, 337–350. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.337

Deschamps, I., Baum, S. R., and Gracco, V. L. (2014). On the role of the supramarginal gyrus in phonological processing and verbal working memory: evidence from rTMS studies. Neuropsychologia 53, 39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.10.015

Dorion, A. A., Chantôme, M., Hasboun, D., Zouaoui, A., Marsault, C., Capron, C., et al. (2000). Hemispheric asymmetry and corpus callosum morphometry: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci. Res. 36, 9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00102-9

Frost, J. A., Binder, J. R., Springer, J. A., Hammeke, T. A., Bellgowan, P. S., Rao, S. M., et al. (1999). Language processing is strongly left lateralized in both sexes. Evidence from functional MRI. Brain 122(Pt 2), 199–208. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.2.199

Fuertinger, S., Horwitz, B., and Simonyan, K. (2015). The functional connectome of speech control. PLoS Biol. 13:e1002209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002209

Fuertinger, S., Zinn, J. C., Sharan, A. D., Hamzei-Sichani, F., and Simonyan, K. (2018). Dopamine drives left-hemispheric lateralization of neural networks during human speech. J. Comp. Neurol. 526, 920–931. doi: 10.1002/cne.24375

Gehrig, J., Wibral, M., Arnold, C., and Kell, C. A. (2012). Setting up the speech production network: how oscillations contribute to lateralized information routing. Front. Psychol. 3:169. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00169

Geschwind, N., and Galaburda, A. M. (2003). Cerebral Lateralization: Biological Mechanisms, Associations, and Pathology. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books.

Goldstein, J. M. (2001). Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb. Cortex 11, 490–497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.490

Gracco, V. L., Tremblay, P., and Pike, B. (2005). Imaging speech production using fMRI. Neuroimage 26, 294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.033

Guadalupe, T., Zwiers, M. P., Wittfeld, K., Teumer, A., Vasquez, A. A., Hoogman, M., et al. (2015). Asymmetry within and around the human planum temporale is sexually dimorphic and influenced by genes involved in steroid hormone receptor activity. Cortex 62, 41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.07.015

Gur, R. C., Alsop, D., Glahn, D., Petty, R., Swanson, C. L., Maldjian, J. A., et al. (2000). An fMRI study of sex differences in regional activation to a verbal and a spatial task. Brain Lang. 74, 157–170. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2325

Hier, D. B., Yoon, W. B., Mohr, J. P., Price, T. R., and Wolf, P. A. (1994). Gender and aphasia in the stroke data bank. Brain Lang. 47, 155–167. doi: 10.1006/brln.1994.1046

Kansaku, K., and Kitazawa, S. (2001). Imaging studies on sex differences in the lateralization of language. Neurosci. Res. 41, 333–337. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00292-9

Kearney, E., and Guenther, F. H. (2019). Articulating: the neural mechanisms of speech production. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2019.1589541

Keating, D., Turrell, G., and Ozanne, A. (2001). Childhood speech disorders: reported prevalence, comorbidity and socioeconomic profile. J. Paediatr. Child Health 37, 431–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00697.x

Kitazawa, S., and Kansaku, K. (2005). Sex difference in language lateralization may be task-dependent. Brain 128, E30–E30.

Koelkebeck, K., Miyata, J., Kubota, M., Kohl, W., Son, S., Fukuyama, H., et al. (2014). The contribution of cortical thickness and surface area to gray matter asymmetries in the healthy human brain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 6011–6022. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22601

Kong, X.-Z., Mathias, S. R., Guadalupe, T., Group, E. L. W., Glahn, D. C., Franke, B., et al. (2018). Mapping cortical brain asymmetry in 17,141 healthy individuals worldwide via the ENIGMA Consortium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E5154–E5163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718418115

Kort, N. S., Nagarajan, S. S., and Houde, J. F. (2014). A bilateral cortical network responds to pitch perturbations in speech feedback. Neuroimage 86, 525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.042

Kumar, V., Croxson, P. L., and Simonyan, K. (2016). Structural organization of the laryngeal motor cortical network and its implication for evolution of speech production. J. Neurosci. 36, 4170–4181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3914-15.2016

Kusmierek, P., Ortiz, M., and Rauschecker, J. P. (2012). Sound-identity processing in early areas of the auditory ventral stream in the macaque. J. Neurophysiol. 107, 1123–1141. doi: 10.1152/jn.00793.2011

Law, J., Boyle, J., Harris, F., Harkness, A., and Nye, C. (1998). Screening for primary speech and language delay: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 33(Suppl.), 21–23. doi: 10.3109/13682829809179388

Lindell, A. K. (2006). In your right mind: right hemisphere contributions to language processing and production. Neuropsychol. Rev. 16, 131–148. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9011-9

Luders, E., Narr, K. L., Thompson, P. M., Rex, D. E., Jancke, L., and Toga, A. W. (2006). Hemispheric asymmetries in cortical thickness. Cereb. Cortex 16, 1232–1238. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj064

Lyttelton, O. C., Karama, S., Ad-Dab’bagh, Y., Zatorre, R. J., Carbonell, F., Worsley, K., et al. (2009). Positional and surface area asymmetry of the human cerebral cortex. Neuroimage 46, 895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.063

Maingault, S., Tzourio-Mazoyer, N., Mazoyer, B., and Crivello, F. (2016). Regional correlations between cortical thickness and surface area asymmetries: a surface-based morphometry study of 250 adults. Neuropsychologia 93, 350–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.03.025

McDermott, K. B., Petersen, S. E., Watson, J. M., and Ojemann, J. G. (2003). A procedure for identifying regions preferentially activated by attention to semantic and phonological relations using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropsychologia 41, 293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00162-8

McGlone, J. (1980). Sex differences in human brain asymmetry: a critical survey. Behav. Brain Sci. 3, 215–227. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00004398

Morillon, B., Lehongre, K., Frackowiak, R. S. J., Ducorps, A., Kleinschmidt, A., Poeppel, D., et al. (2010). Neurophysiological origin of human brain asymmetry for speech and language. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 18688–18693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007189107

Nourski, K. V., and Brugge, J. F. (2011). Representation of temporal sound features in the human auditory cortex. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 187–203. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.016

Oldfield, R. C. (1971). The assessment and analysis of handedness: the edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4

Pedersen, P. M., Jørgensen, H. S., Nakayama, H., Raaschou, H. O., and Olsen, T. S. (1995). Aphasia in acute stroke: incidence, determinants, and recovery. Ann. Neurol. 38, 659–666. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380416

Pedersen, P. M., Vinter, K., and Olsen, T. S. (2004). Aphasia after stroke: type, severity and prognosis. the copenhagen aphasia study. Cereb. Dis. 17, 35–43. doi: 10.1159/000073896

Phillips, D. P., and Farmer, M. E. (1990). Acquired word deafness, and the temporal grain of sound representation in the primary auditory cortex. Behav. Brain Res. 40, 85–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90001-u

Plessen, K. J., Hugdahl, K., Bansal, R., Hao, X., and Peterson, B. S. (2014). Sex, age, and cognitive correlates of asymmetries in thickness of the cortical mantle across the life span. J. Neurosci. 34, 6294–6302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3692-13.2014

Price, C. J. (2000). The anatomy of language: contributions from functional neuroimaging. J. Anatom. 197, 335–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19730335.x

Price, C. J., Moore, C. J., Humphreys, G. W., and Wise, R. J. S. (1997). Segregating semantic from phonological processes during reading. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 9, 727–733. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.6.727

Scott, S. K., and Wise, R. J. S. (2004). The functional neuroanatomy of prelexical processing in speech perception. Cognition 92, 13–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2002.12.002

Shaywitz, B. A., Shaywitz, S. E., Pugh, K. R., Constable, R. T., Skudlarski, P., Fulbright, R. K., et al. (1995). Sex differences in the functional organization of the brain for language. Nature 373, 607–609.

Shriberg, L. D., and Kwiatkowski, J. (1994). Developmental phonological disorders. I: a clinical profile. J. Speech Hear. Res. 37, 1100–1126. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3705.1100

Shum, M., Shiller, D. M., Baum, S. R., and Gracco, V. L. (2011). Sensorimotor integration for speech motor learning involves the inferior parietal cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 1817–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07889.x

Silbert, L. J., Honey, C. J., Simony, E., Poeppel, D., and Hasson, U. (2014). Coupled neural systems underlie the production and comprehension of naturalistic narrative speech. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E4687–E4696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323812111

Simonyan, K., Ackermann, H., Chang, E. F., and Greenlee, J. D. (2016). New developments in understanding the complexity of human speech production. J. Neurosci. 36, 11440–11448. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2424-16.2016

Simonyan, K., and Fuertinger, S. (2015). Speech networks at rest and in action: interactions between functional brain networks controlling speech production. J. Neurophysiol. 113, 2967–2978. doi: 10.1152/jn.00964.2014

Simonyan, K., Ostuni, J., Ludlow, C. L., and Horwitz, B. (2009). Functional but not structural networks of the human laryngeal motor cortex show left hemispheric lateralization during syllable but not breathing production. J. Neurosci. 29, 14912–14923. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4897-09.2009

Sliwinska, M. W., Khadilkar, M., Campbell-Ratcliffe, J., Quevenco, F., and Devlin, J. T. (2012). Early and sustained supramarginal gyrus contributions to phonological processing. Front. Psychol. 3:161. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00161

Sommer, I. E. C., Aleman, A., Bouma, A., and Kahn, R. S. (2004). Do women really have more bilateral language representation than men? a meta-analysis of functional imaging studies. Brain 127, 1845–1852. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh207

Tourville, J. A., and Guenther, F. H. (2003). A Cortical and Cerebellar Parcellation System for Speech Studies. Boston, MA: Boston University center for Adaptive Systems.

Wallentin, M. (2009). Putative sex differences in verbal abilities and language cortex: a critical review. Brain Lang. 108, 175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.07.001

Warrier, C., Wong, P., Penhune, V., Zatorre, R., Parrish, T., Abrams, D., et al. (2009). Relating structure to function: heschl’s gyrus and acoustic processing. J. Neurosci. 29, 61–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3489-08.2009

Keywords: speech control, sensorimotor network, cortical thickness, fMRI, healthy subjects

Citation: de Lima Xavier L, Hanekamp S and Simonyan K (2019) Sexual Dimorphism Within Brain Regions Controlling Speech Production. Front. Neurosci. 13:795. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00795

Received: 05 May 2019; Accepted: 16 July 2019;

Published: 30 July 2019.

Edited by:

Lynne E. Bernstein, George Washington University, United StatesReviewed by:

Soo-Eun Chang, University of Michigan, United StatesIain DeWitt, Georgetown University Medical Center, United States

Copyright © 2019 de Lima Xavier, Hanekamp and Simonyan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristina Simonyan, a3Jpc3RpbmFfc2ltb255YW5AbWVlaS5oYXJ2YXJkLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Laura de Lima Xavier

Laura de Lima Xavier Sandra Hanekamp

Sandra Hanekamp Kristina Simonyan

Kristina Simonyan