94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Neurosci., 11 December 2018

Sec. Neurogenesis

Volume 12 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00874

This article is part of the Research TopicEpigenetic Mechanisms of Neurogenesis in the Developing NeocortexView all 10 articles

The regulation of genome architecture is a key determinant of gene transcription patterns and neural development. Advances in methodologies based on chromatin conformation capture (3C) have shed light on the genome-wide organization of chromatin in developmental processes. Here, we review recent discoveries regarding the regulation of three-dimensional (3D) chromatin conformation, including promoter–enhancer looping, and the dynamics of large chromatin domains such as topologically associated domains (TADs) and A/B compartments. We conclude with perspectives on how these conformational changes govern neural development and may go awry in disease states.

The human and mouse genomes consist of ∼6 and ∼5 billion base pairs, respectively, and are packaged in chromosomes that are contained within a nucleus with a diameter of only ∼5 μm. Chromosomes possess multilayered structures that can be broadly classified on the basis of classical cytological and biochemical analyses either as euchromatin, an open chromatin state characteristic of gene-rich regions, or as heterochromatin, a closed chromatin state characteristic of gene-poor regions. At a higher level of resolution, local associations between gene promoters and other regulatory elements, such as enhancers, define the structural relations within active transcriptional domains (Vernimmen and Bickmore, 2015).

High-throughput chromatin conformation capture (3C) techniques have recently allowed the categorization of chromosomal domains into two major classes (Figure 1; van de Werken et al., 2012; Bonev and Cavalli, 2016; Dekker and Mirny, 2016; Dixon et al., 2016; Hansen et al., 2018). In this review, we first briefly summarize advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that regulate the formation of TADs and A/B compartments. We then address recent studies that have examined changes in genomic interactions and three-dimensional (3D) genome organization including TADs and A/B compartments during mammalian neural development, and we discuss how these chromosomal changes regulate this process.

Recent studies have revealed some molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of TADs. The zinc-finger DNA-binding protein CTCF and the ring-shaped cohesin complex bind to many boundaries between TADs (Dixon et al., 2012; Nora et al., 2012; Rao et al., 2014), and some studies have proposed that “loop extrusion” mediated by the cohesin complex and the convergent orientation of CTCF binding play a role in TAD formation (Sanborn et al., 2015; Fudenberg et al., 2016). Real-time imaging revealed that the condensin complex, which belongs to the same Smc family as the cohesin complex, indeed induced DNA loop extrusion in vitro (Ganji et al., 2018). Importantly, forced degradation of CTCF or Rad21, an essential component of the cohesin complex, with the use of the auxin-induced rapid degradation system, resulted in the almost complete elimination of TADs (Nora et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2017). Conditional knockout of the cohesin-loading factor Nipbl or Scc4 also induced deformation of TADs (Haarhuis et al., 2017; Schwarzer et al., 2017). These observations have suggested that CTCF and the cohesin complex are essential for the establishment of TADs. However, even though TADs were essentially eliminated in cells depleted of CTCF or Rad21, A/B compartments were largely unaffected (Nora et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2017). This finding indicates that A/B compartmentalization of mammalian chromosomes emerges independently of proper insulation of TADs, even though TADs serve as units of A/B compartments. Interestingly, acute loss of cohesin had only limited effects on gene expression and the distribution of various histone modifications (Rao et al., 2017; Schwarzer et al., 2017), which may suggest that regulatory interactions are somewhat preserved after the loss of TADs.

With regard to A/B compartments, heterochromatin has been proposed to serve as a driver of compartmentalization. Lamina-associated domains (LADs), defined as genomic regions that contact the nuclear lamina, constitute heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery (van Steensel and Belmont, 2017). LADs revealed by a method known as DamID (DNA adenine methyltransferase identification) analysis showed cell-to-cell heterogeneity and a strong correlation with the B compartment (Rao et al., 2014; Kind et al., 2015). Given that the nuclear lamina provides a platform for chromatin reassembly during the M-to-G1 phase transition of the cell cycle (Güttinger et al., 2009), LAD formation may underlie compartmentalization of heterochromatin domains and the B compartment, although this is still under debate (Falk et al., 2018). Another emerging feature of heterochromatin domains is phase separation into liquid droplets mediated by heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) (Larson et al., 2017; Strom et al., 2017). Liquid phase separation is thought to provide a basis for the formation of membrane-less structures (Boeynaems et al., 2018). The B compartment can be considered as such a membrane-less structure given the enrichment of histone H3 methylated at lysine-9 (H3K9) in this compartment (Rao et al., 2014), which provides a platform for HP1 binding and oligomerization required for liquid phase separation, as supported by a recent modeling experiment (Falk et al., 2018).

Although these various studies have elucidated the framework for 3D organization of the genome, many questions regarding TAD formation – including the role of transcription, whether loop extrusion is asymmetric, and the relevance of DNA replication – remain unanswered. In addition, the mechanisms underlying A/B compartmentalization remain largely elusive. A key unanswered question regarding genome architecture is, how do local and global-scale associations, including those mediated by A/B compartments and TADs, govern changes in transcription and cell fate during development. In this review, we focus on studies on neural development in an attempt to tackle this question.

The 3D architecture of chromatin changes markedly during the neural development of pluripotent stem cells. Assays based on micrococcal nuclease (MNase) or DNase I accessibility or on histone extraction have revealed that the chromatin state is globally open in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and becomes condensed during differentiation into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) (Meshorer et al., 2006). Even among NPCs, the loss of neurogenic potential during neocortical development is associated with chromatin condensation on a large scale (Kishi et al., 2012a; Tyssowski et al., 2014). The “openness” of chromatin may be related to differentiation potential (“stemness”) in these cells, given that the factors responsible for global chromatin accessibility – Chd1 in ESCs and Hmga in NPCs – are also required for differentiation potential (Gaspar-Maia et al., 2009; Kishi et al., 2012a). Chromatin state also undergoes pronounced changes during neuronal differentiation of NPCs. For example, the number and shape of chromocenters – heterochromatin foci strongly stained with DNA-intercalating dyes – change during neuronal differentiation (Billia et al., 1992; Solovei et al., 2004, 2009; Clowney et al., 2012; Le Gros et al., 2016). Likewise, an increase in the deposition of the active histone mark H3K4me3 (trimethylated lysine-4 of histone H3) at chromocenters, accompanied by an increase in transcription of major satellites, is also observed during neuronal differentiation in the neocortex (Kishi et al., 2012b). Recent examinations of chromatin accessibility by the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq), DNase-seq, and formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE)-seq have revealed progressive changes in chromatin openness during neuronal differentiation processes (Frank et al., 2015; Thakurela et al., 2015; de la Torre-Ubieta et al., 2018; Preissl et al., 2018), which would link chromatin accessibility to the genome architecture associated with these processes.

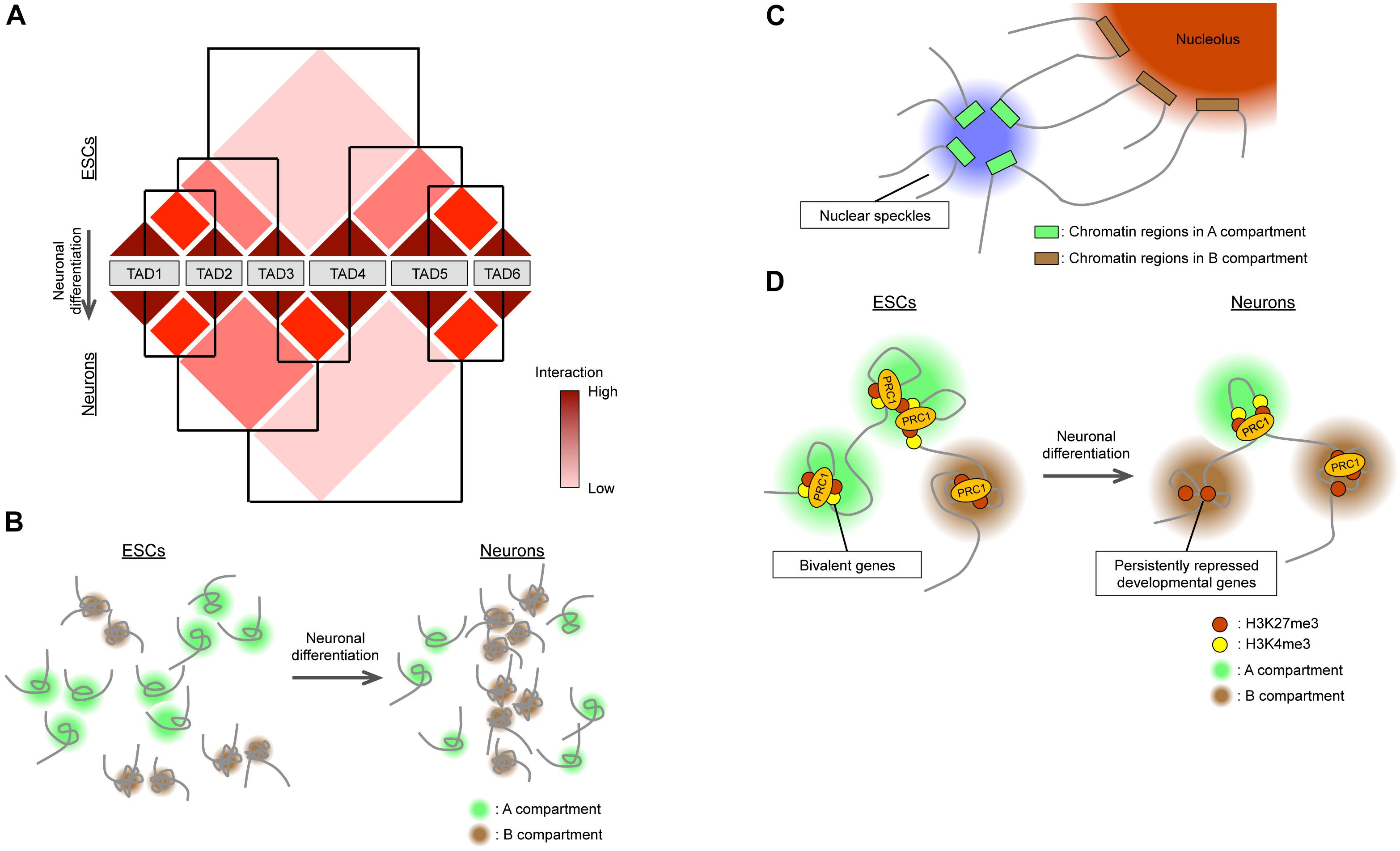

So, how are TADs and A/B compartments regulated during neural development? TADs are structurally dynamic overall (Hansen et al., 2018), but TAD boundaries, on the other hand, are stable for many cell divisions and invariant across diverse cell types or lineages (Nora et al., 2012; Rao et al., 2014; Dixon et al., 2015, 2016). Indeed, differentiation of ESCs into NPCs and then into neurons is not accompanied by changes in the boundaries of most TADs (Fraser et al., 2015). Rather, inter-TAD interactions as well as chromatin interactions within TADs (sub-TAD or intra-TAD level, including chromatin looping) change during differentiation (Fraser et al., 2015; Dixon et al., 2016, 2015). Fraser et al. (2015) proposed that TADs are organized into meta-TADs in a hierarchical manner, and that neural differentiation of ESCs is accompanied by the rearrangement of meta-TAD components (Figure 2A). A fraction of inter-TAD rearrangement is associated with changes in gene expression within TADs (Fraser et al., 2015), and TAD allocation to A/B compartments changes during differentiation (Dixon et al., 2015).

Figure 2. Global changes in 3D genome organization during neural differentiation. (A) TADs are organized in a hierarchical manner, and their reorganization accompanies neural differentiation. (B) During neural differentiation from ESCs, interactions within the A compartment decrease while those within the B compartment increase. The size of the A compartment also decreases during neural differentiation. (C) Nuclear speckles and nucleoli act as hubs for interactions within A and B compartments, respectively. (D) In ESCs, bivalent genes interact with each other via PRC1 in the A compartment. Neural differentiation is accompanied by the loss of PRC1-mediated interactions between bivalent genes, with the genes becoming persistently repressed and relocating to the B compartment.

In contrast to TADs, A/B compartments are differentially regulated during neural development. Recent studies have examined and compared genome-wide 3D chromatin organization during neural differentiation from ESCs (Dixon et al., 2015; Bonev et al., 2017) by Hi-C analysis, which allows the detection of complete “all versus all” long-distance chromatin interactions across the entire genome (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009). One study (Dixon et al., 2015) found that the total size of the A compartment in differentiated cells including NPCs was reduced by 5% compared with that in ESCs (Figure 2B). This finding appears to be consistent with the global condensation of the chromatin state observed when ESCs differentiate into neural cells mentioned above. Another study (Bonev et al., 2017) based on higher-resolution Hi-C analysis (maximum of 750 bp) found that interactions within the A compartment decreased during the ESC-to-NPC transition, interactions between A and B compartments transiently increased in NPCs, and interactions within the B compartment increased during the NPC-to-neuron transition, supporting the notion that chromatin undergoes global compaction in association with differentiation (Figure 2B). Also consistent with this idea, the positive correlation between active histone marks [H3K4me1, H3K27ac (acetylated lysine-27 of histone H3), and H3K36me3] and the A compartment became weaker, whereas that between the inactive mark H3K9me3 and the B compartment became stronger, during neural (ESC-NPC-neuron) differentiation (Bonev et al., 2017). Regarding the inactive (B) compartment, as extreme cases, rod photoreceptor cells manifest heterochromatin aggregation in the center of the nucleus (Solovei et al., 2009), and postmitotic olfactory sensory neurons show pronounced compaction of olfactory receptor gene loci (Clowney et al., 2012; Le Gros et al., 2016). However, Hi-C results suggest that the compaction of heterochromatin domains may be a general feature of differentiating neurons and contribute to the stable silencing of unnecessary genes for differentiated neurons (Solovei et al., 2009; Clowney et al., 2012; Bonev et al., 2017). Given the changes in LADs during neural development (Peric-Hupkes et al., 2010), the downregulation of a lamin B receptor apparent during neuronal differentiation provides a possible common mechanism for this heterochromatin reorganization (Clowney et al., 2012; Solovei et al., 2013).

How then are regions in the A compartment regulated? High-level interactions within the A compartment in ESCs can be explained in part by long-range (>30 Mb) associations between active promoters, enhancers, and actively transcribed genes both in cis and in trans (Li et al., 2012; Schoenfelder et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2015; Bonev et al., 2017). In addition to 3C-based methods, a technique known as genome architecture mapping (GAM) can determine the proximity of genomic loci without cross-linking by ultrathin cryosectioning of nuclei followed by laser microdissection and DNA sequencing (Beagrie et al., 2017). GAM confirmed an abundance of long-range interactions, especially between “super-enhancers” [which are marked by extremely high levels of H3K27ac (Hnisz et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013)] in ESCs. Super-enhancers are cell type specific and play key roles in cell fate determination (Hnisz et al., 2013). Given that they are enriched in binding elements for cell type-specific transcription factors (Hnisz et al., 2013), it is possible that homotypic interactions between these factors can induce the aggregation (high-density interaction) of super-enhancers. Moreover, whereas high-density contacts between active promoters were found to be independent of CTCF (Bonev et al., 2017), degradation of the cohesin component Rad21 resulted in an increase in the number of long-range interactions between super-enhancers (Rao et al., 2017), suggesting that the cohesin complex insulates long-range interactions between super-enhancers and thereby ensures the fidelity of cell type-specific gene expression patterns.

On the basis of classical immunocytochemical analyses, nuclear bodies, which are subcompartments within the nucleus, were hypothesized to serve as hubs for active or inactive gene loci (Rino et al., 2007; Sutherland and Bickmore, 2009; Padeken and Heun, 2014), although there was no genome-wide evidence to support this notion. A ligation-independent method known as split-pool recognition of interactions by tag extension (SPRITE) that relies on uniquely tagged cross-linked chromatin fragments to determine the proximity of genomic loci was recently introduced (Quinodoz et al., 2018). This method detects proximity between both DNA and RNA molecules and revealed that regions in the active (A) compartment preferentially interact with U1 spliceosomal RNA and Malat1 long noncoding RNA localized at nuclear speckles, whereas those in the inactive (B) compartment interact with rRNA localized at the nucleolus (Figure 2C). Consistent with these observations, the contact enrichment between gene bodies positively correlates with transcriptional level as well as with the numbers of exons and splicing events (Bonev et al., 2017). Given the contribution of nuclear bodies to neural development (Bernard et al., 2010; Hetman and Pietrzak, 2012), these results suggest that the dynamic rearrangements of A/B compartments during neural development may be dependent on or connected to changes in nuclear bodies.

In general, active and inactive histone modifications are associated with A and B compartments, respectively (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2014). Interestingly, although H3K27me3, a modification deposited by Polycomb repressor complex 2 (PRC2), is generally considered an inactive histone mark, it is highly associated with the A compartment in ESCs and becomes associated more with the B compartment in neurons (Bonev et al., 2017; Figure 2D). This finding can be explained in part by the role of Polycomb group (PcG) proteins in the maintenance of developmental genes in the “poised” state in stem cells for later activation in response to differentiation-inducing cues (Azuara et al., 2006; Bernstein et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2007). Such poised promoters tend to be “bivalent” in that they possess both active (H3K4me3) and inactive (H3K27me3) marks, and are thus included in the A compartment. Consistent with the notion that PcG proteins, including Ring1B – a major component of Polycomb repressor complex 1 (PRC1) – are associated with many poised developmental genes included in the A compartment in pluripotent stem cells and that such association is attenuated after differentiation, the genomic loci bound by Ring1B manifest strong interactions in ESCs but these interactions become progressively reduced during neural differentiation (Bonev et al., 2017). Furthermore, PcG protein-mediated chromatin interactions can take place beyond TAD boundaries and establish inter-TAD and inter-chromosomal associations in addition to those within TAD boundaries (Denholtz et al., 2013; Schoenfelder et al., 2015; Kundu et al., 2017). The global loss of PRC1-mediated, but H3K27me3-independent, long-range chromatin interactions during neural differentiation may therefore account in part for the global changes in chromatin architecture associated with this process. Conversely, a specific subset of Ring1B-mediated interactions becomes stronger during differentiation so as to allow for persistent repression of certain developmental genes associated with fate restriction (Bonev et al., 2017; Tsuboi et al., 2018). These inactive genes that are persistently silenced by PcG proteins are included in the B compartment. Mechanistically, PcG proteins can mediate high-density chromatin interactions via self-aggregation within and between PRC1 and PRC2 (Kim et al., 2002; Francis et al., 2004; Margueron et al., 2008; Eskeland et al., 2010; Grau et al., 2011; Isono et al., 2013). In particular, Phc protein components of PRC1 form nuclear nanoclusters in a manner dependent on polymerization activity of the SAM (sterile alpha motif) domain, with the formation of these clusters facilitating long-range chromatin interactions and persistent silencing (Isono et al., 2013; Wani et al., 2016; Tsuboi et al., 2018).

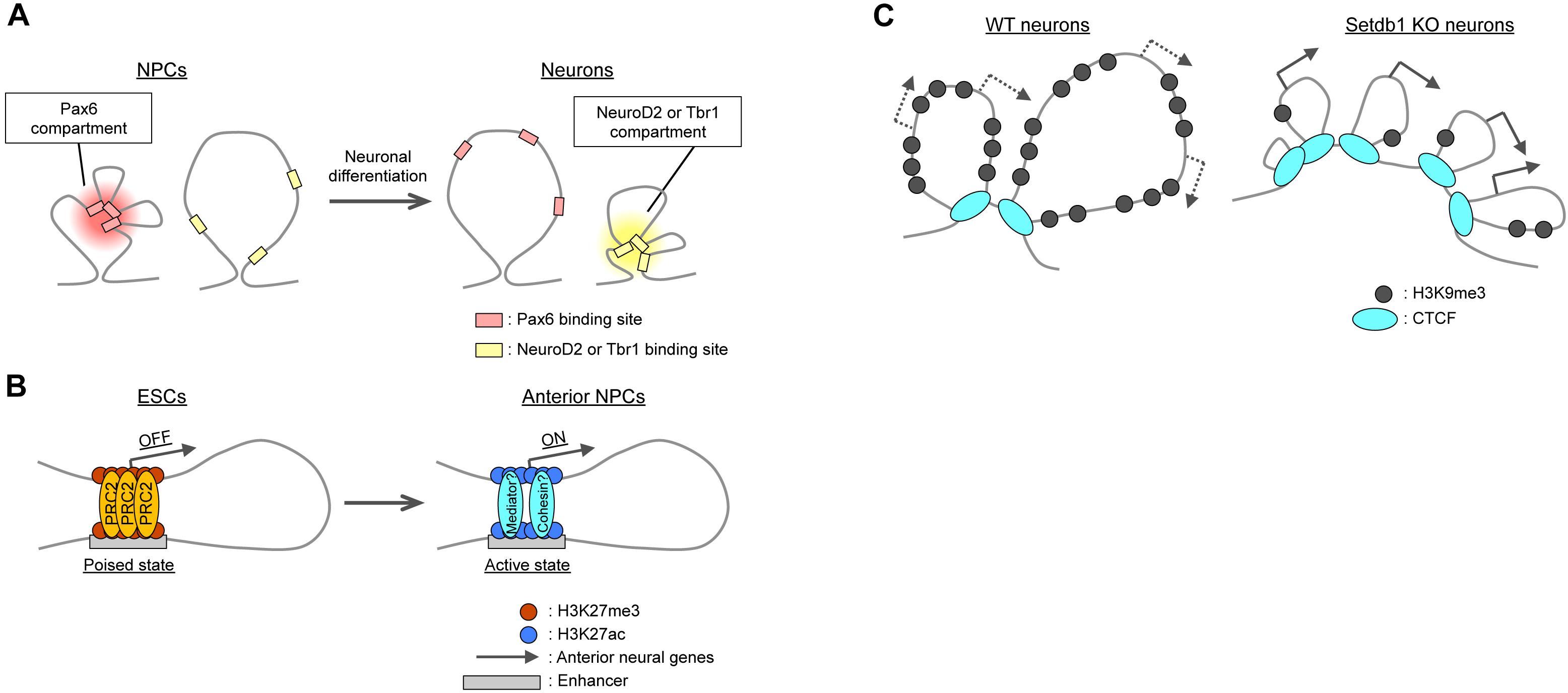

Topologically associated domains constitute units of gene regulation (Alexander and Lomvardas, 2014; Dixon et al., 2015; Lupiáñez et al., 2015; Narendra et al., 2016; Symmons et al., 2016; Zhan et al., 2017), with most enhancer–promoter interactions taking place within TADs. High-resolution Hi-C or promoter-capture Hi-C analyses have confirmed that such interactions are highly cell type specific (Rao et al., 2014; Javierre et al., 2016; Bonev et al., 2017; Freire-Pritchett et al., 2017). For example, neuronal enhancers interact with their promoters more strongly in neurons than in ESCs and NPCs (Mifsud et al., 2015; Bonev et al., 2017). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq analyses have revealed a link between intra-TAD interactions and cell type-specific transcription factors such as the NPC-specific Pax6 and the immature neuron- and mature neuron-specific NeuroD2 and Tbr1, respectively (Figure 3A). The interactions of Pax6-bound sites were thus stronger in NPCs than in neurons or ESCs, whereas those of NeuroD2- or Tbr1-bound sites were stronger in neurons than in NPCs or ESCs (Bonev et al., 2017). Transcription factors may also organize the co-regulation of target genes through homotypic interactions or association with partner molecules such as the BAF chromatin remodeling complex for Pax6 (Ninkovic et al., 2013; Manuel et al., 2015).

Figure 3. Local changes in 3D genome organization during neural differentiation. (A) Intra-TAD interactions between binding regions for cell type-specific transcription factors such as Pax6, NeuroD2, and Tbr1. (B) Polycomb (PRC2)-mediated interactions between promoters and poised enhancers lead to the activation of anterior neural genes during differentiation. (C) In cortical neurons, H3K9me3 deposition catalyzed by Setdb1 prevents aberrant CTCF binding at Pcdh gene clusters. Knockout (KO) of Setdb1 induces excessive insulation and upregulation of Pcdh gene expression.

Polycomb group proteins generally mediate repression of gene expression, as mentioned above. However, recent studies have revealed that these proteins may contribute to gene activation via the establishment of enhancer–promoter interactions. PRC1 (Ring1) can mediate the association of a midbrain-specific enhancer and the promoter of the Meis2 gene during midbrain development, with the subsequent dissociation of PcG proteins resulting in the activation of Meis2 expression in the midbrain (Kondo et al., 2014; Yakushiji-Kaminatsui et al., 2016). PcG proteins were found to play a similar role in the establishment of “poised” enhancers in ESCs. The poised enhancers were defined by the presence of the histone acetyltransferase p300 and H3K27me3 and the absence of H3K27ac and H3K4me3, and neural genes, especially anterior neural genes, were found to be enriched in poised enhancers in ESCs (Cruz-Molina et al., 2017). Importantly, poised enhancers physically contact their target genes in a PRC2-dependent manner, and the PRC2 components Suz12 and Eed are necessary for the induction of anterior neural genes in NPCs (Figure 3B). These findings point to the essential role of PcG proteins in the generation of permissive chromatin topology at such gene loci before their activation, although the molecular basis of their differential roles in gene activation and suppression remains to be clarified.

The preferential regulation of anterior neural genes by poised enhancers in ESCs (Cruz-Molina et al., 2017) per se is an intriguing finding. Classical developmental models propose that epiblast cells in vivo and ESCs in vitro are fated toward the neural lineage by “default” (that is, in the “absence” of extrinsic signals) (Levine and Brivanlou, 2007; Gaspard and Vanderhaeghen, 2010). Moreover, induced neural progenitors initially manifest anterior characteristics (that is, those of the forebrain), which must be overridden by extrinsic cues for the induction of more posterior neural fates (such as those of the spinal cord). The readiness of anterior neural genes to be expressed due to their association with poised enhancers in ESCs may explain in part the propensity for default differentiation to an anterior neural lineage.

As mentioned above, most TAD boundaries are conserved between ESCs and neural cells, but a fraction of TAD boundaries appears to emerge and disappear during neural differentiation (Bonev and Cavalli, 2016) – although the interpretation of TAD boundaries depends on the precise definition of TADs (Dixon et al., 2016). Of note, these developmentally regulated TAD boundaries correlate with H3K4me1-positive enhancers (Dixon et al., 2015) and active gene marks (Bonev et al., 2017) as well as with the presence of cohesin, but not that of CTCF (Bonev et al., 2017). Indeed, the emergence of new boundaries in NPCs was found to be associated with Zfp608- and Sox4-dependent transcription, although forced induction of such transcription with the use of the dCas9 system was not sufficient to induce a new TAD boundary (Bonev et al., 2017).

Topologically associated domain boundaries can play a role in the regulation of neural genes, most notably in Protocadherin (Pcdh) gene clusters. Pcdh proteins regulate axonal targeting, synapse formation, and dendritic arborization through their homophilic trans-interactions (Yagi, 2012; Chen and Maniatis, 2013). The vast diversity of neurons is generated in part by the stochastic and combinatorial expression of the clustered Pcdh genes, which include Pcdhα, Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ clusters aligned in cis. In situ Hi-C experiments with NeuN-positive mouse neocortical neurons revealed that the Pcdh gene clusters are organized as multiple small TADs (∼100 kb in length) nested into a larger TAD that encompasses at least 1.2 Mb. The 5′ end of the Pcdhα cluster is bound to the 3′ end of the Pcdhγ cluster (Jiang et al., 2017). This TAD structure appears to be important for proper regulation of Pcdh genes, given that knockout of CTCF disrupted TADs at this locus and resulted in the aberrant expression of Pcdh genes (Hirayama et al., 2012; Sams et al., 2016). The unique TAD structure of Pcdh gene clusters was also apparent in neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Interestingly, a risk haplotype for schizophrenia (according to the Psychiatric Genomic Consortium) has been found to be genetically linked to the 5′ end of the human Pcdhα gene cluster (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014). Forced dCas9-mediated localization of KRAB or VP64 transcriptional repressor or activator domains, respectively, at the risk gene locus in human iPSC-derived NPCs resulted in dysregulation of Pcdh gene transcription (Jiang et al., 2017). Given the neurodevelopmental functions of Pcdh proteins, an aberrant TAD structure of the Pcdh gene clusters could potentially contribute to the development of schizophrenia.

With regard to the mechanism responsible for the TAD structure of Pcdh gene clusters, deposition of H3K9me3 by the histone methyltransferase Setdb1 (also known as Kmt1e or ESET) (Schultz et al., 2002) appears to play an essential role. Ablation of Setdb1 in neocortical neurons reduced the level of H3K9me3 and increased the binding of CTCF at the Pcdh gene clusters, resulting in the formation of only small TADs without the large-scale interaction normally apparent between the borders of the clusters (Figure 3C; Jiang et al., 2017). Cytosine methylation (5mC) was shown to inhibit the binding of CTCF (Renda et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012), although this finding is still under debate (see Bonev and Cavalli, 2016). Setdb1 ablation reduced 5mC levels at several residues in the Pcdh gene clusters, which thus may account for the increased CTCF binding and aberrant insulation within these clusters.

Regulation of CTCF binding and TAD structure by Setdb1 is not restricted to Pcdh gene clusters. Loss of Setdb1 in neocortical neurons thus resulted in the emergence of more than 3000 ectopic CTCF-binding sites (Jiang et al., 2017). Setdb1 has also been shown to contribute to the development of several tissues including the mouse neocortex (Tan et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Eymery et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Takikita et al., 2016). Ablation of Setdb1 altered the differentiation potential of neocortical NPCs by reducing neurogenic potential and increasing astrogenic potential. Of interest, transcriptome analysis of Setdb1-deficient NPCs revealed ectopic expression of genes of nonneural lineages as well as of transposons (Tan et al., 2012), implicating Setdb1 in repression of these genes, possibly mediated by inhibition of unwanted CTCF binding and consequent promotion of proper formation of TAD structures in addition to its role in heterochromatin formation through H3K9me3. CTCF binding is also regulated by other factors including YY1, which may control enhancer–promoter interactions and transcription in NPCs (Beagan et al., 2017; Weintraub et al., 2017), although the ubiquitously expressed YY1 alone may not be able to account for cell type-specific CTCF regulation.

The regulation of 3D chromatin structure has been studied with regard to its role in determination of gene transcription patterns. New technologies such as high-resolution 3C-based methods have revealed that neural development is accompanied by changes in genome organization at the levels of both interactions between large compartments and local interactions such as those between enhancers and promoters. Such advances in basic knowledge concerning chromatin structure will facilitate our understanding of the mechanisms and relevance of chromatin regulation during neural development and the pathogenesis of related diseases. Given the heterogeneity of NPCs and neurons, analyses at the single-cell level will be especially important for studies of neural development, and the recent implementation of advanced single-cell RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, DamID, ATAC-seq, and Hi-C technologies should prove highly informative in this regard (Nagano et al., 2013; Shalek et al., 2014; Buenrostro et al., 2015; Kind et al., 2015; Macosko et al., 2015; Rotem et al., 2015; Corces et al., 2016; Stevens et al., 2017). The spatial and functional nature of the relation between chromatin domains and nuclear bodies, the nuclear lamina, and other aspects of nuclear architecture also await clarification in future studies (Sutherland and Bickmore, 2009; Quinodoz et al., 2018). Recent developments in advanced microscopic technology, including super-resolution and electron microscopies, as well as in live-cell imaging of specific genomic loci with the use of zinc-finger nuclease, transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN), or CRISPR (clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats)–Cas9 systems may uncover novel principles of 3D organization and genomic localization in the nucleus (Chen et al., 2016; Ricci et al., 2017). We focused in this review on the early developmental process of neural differentiation, but it will also be of interest to determine how chromatin architecture is regulated during neuronal maturation and in association with neural plasticity triggered by changes in neuronal activity (Wittmann et al., 2009; Frank et al., 2015; Thakurela et al., 2015; de la Torre-Ubieta et al., 2018; Gallegos et al., 2018; Preissl et al., 2018).

As suggested in the case of the Pcdh gene clusters, aberrant changes in 3D chromatin structure may give rise to neurodevelopmental disorders (Mitchell et al., 2014). Indeed, mutations in the genes for cohesin components are known to be responsible for Cornelia de Lange syndrome in humans, which is associated with mental retardation (Krantz et al., 2004; Tonkin et al., 2004; Deardorff et al., 2007, 2012; Fujita et al., 2017). Mutations in CTCF and Setdb1 genes also cause severe neural developmental defects in mice (Watson et al., 2014; Sams et al., 2016). Although access to human tissue is limited, the organization of the human genome in both the developing and adult human brain has recently been investigated by Hi-C analyses (Won et al., 2016). Such studies as well as those of neurons derived from iPSCs of patients with neurodevelopmental disorders should provide insight into the pathogenesis of these conditions as well as a basis for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

YK and YG wrote the manuscript.

The work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (JP16H01297 and JP18K14622 for YK; JP16H06479, JP16H06481, and JP15H05773 for YG), by JST AMED-CREST (JP18gm0610013), and by The Uehara Memorial Foundation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We apologize to all researchers whose work we were not able to cite owing to space limitations. We thank C. Yokoyama, A. West, B. Bonev, and T. Tuoc for critical reading of the manuscript.

Alexander, J. M., and Lomvardas, S. (2014). Nuclear architecture as an epigenetic regulator of neural development and function. Neuroscience 264, 39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.044

Azuara, V., Perry, P., Sauer, S., Spivakov, M., Jørgensen, H. F., John, R. M., et al. (2006). Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 532–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403

Beagan, J. A., Duong, M. T., Titus, K. R., Zhou, L., Cao, Z., Ma, J., et al. (2017). YY1 and CTCF orchestrate a 3D chromatin looping switch during early neural lineage commitment. Genome Res. 27, 1139–1152. doi: 10.1101/gr.215160.116

Beagrie, R. A., Scialdone, A., Schueler, M., Kraemer, D. C. A., Chotalia, M., Xie, S. Q., et al. (2017). Complex multi-enhancer contacts captured by genome architecture mapping. Nature 543, 519–524. doi: 10.1038/nature21411

Bernard, D., Prasanth, K. V., Tripathi, V., Colasse, S., Nakamura, T., Xuan, Z., et al. (2010). A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. EMBO J. 29, 3082–3093. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.199

Bernstein, B. E., Mikkelsen, T. S., Xie, X., Kamal, M., Huebert, D. J., Cuff, J., et al. (2006). A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 125, 315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041

Billia, F., Baskys, A., Carlen, P. L., and De Boni, U. (1992). Rearrangement of centromeric satellite DNA in hippocampal neurons exhibiting long-term potentiation. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 14, 101–108. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(92)90016-5

Boeynaems, S., Alberti, S., Fawzi, N. L., Mittag, T., Polymenidou, M., Rousseau, F., et al. (2018). Protein phase separation: a new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 420–435. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.004

Bonev, B., and Cavalli, G. (2016). Organization and function of the 3D genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 661–678. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.112

Bonev, B., Mendelson Cohen, N., Szabo, Q., Fritsch, L., Papadopoulos, G. L., Lubling, Y., et al. (2017). Multiscale 3D genome rewiring during mouse neural development. Cell 171, 557–572.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.043

Buenrostro, J. D., Wu, B., Litzenburger, U. M., Ruff, D., Gonzales, M. L., Snyder, M. P., et al. (2015). Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature 523, 486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature14590

Chen, B., Guan, J., and Huang, B. (2016). Imaging specific genomic DNA in living cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 45, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010830

Chen, W. V., and Maniatis, T. (2013). Clustered protocadherins. Development 140, 3297–3302. doi: 10.1242/dev.090621

Clowney, E. J., LeGros, M. A., Mosley, C. P., Clowney, F. G., Markenskoff-Papadimitriou, E. C., Myllys, M., et al. (2012). Nuclear aggregation of olfactory receptor genes governs their monogenic expression. Cell 151, 724–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.043

Corces, M. R., Buenrostro, J. D., Wu, B., Greenside, P. G., Chan, S. M., Koenig, J. L., et al. (2016). Lineage-specific and single-cell chromatin accessibility charts human hematopoiesis and leukemia evolution. Nat. Genet. 48, 1193–1203. doi: 10.1038/ng.3646

Cruz-Molina, S., Respuela, P., Tebartz, C., Kolovos, P., Nikolic, M., Fueyo, R., et al. (2017). PRC2 facilitates the regulatory topology required for poised enhancer function during pluripotent stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 20, 689–705.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.02.004

de la Torre-Ubieta, L., Stein, J. L., Won, H., Opland, C. K., Liang, D., Lu, D., et al. (2018). The dynamic landscape of open chromatin during human cortical neurogenesis. Cell 172, 289–304.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.014

Deardorff, M. A., Kaur, M., Yaeger, D., Rampuria, A., Korolev, S., Pie, J., et al. (2007). Mutations in cohesin complex members SMC3 and SMC1A cause a mild variant of cornelia de Lange syndrome with predominant mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 485–494. doi: 10.1086/511888

Deardorff, M. A., Wilde, J. J., Albrecht, M., Dickinson, E., Tennstedt, S., Braunholz, D., et al. (2012). RAD21 mutations cause a human cohesinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 1014–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.019

Dekker, J., and Mirny, L. (2016). The 3D genome as moderator of chromosomal communication. Cell 164, 1110–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.007

Denholtz, M., Bonora, G., Chronis, C., Splinter, E., de Laat, W., Ernst, J., et al. (2013). Long-range chromatin contacts in embryonic stem cells reveal a role for pluripotency factors and polycomb proteins in genome organization. Cell Stem Cell 13, 602–616. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.013

Dixon, J. R., Gorkin, D. U., and Ren, B. (2016). Chromatin domains: the unit of chromosome organization. Mol. Cell. 62, 668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.018

Dixon, J. R., Jung, I., Selvaraj, S., Shen, Y., Antosiewicz-Bourget, J. E., Lee, A. Y., et al. (2015). Chromatin architecture reorganization during stem cell differentiation. Nature 518, 331–336. doi: 10.1038/nature14222

Dixon, J. R., Selvaraj, S., Yue, F., Kim, A., Li, Y., Shen, Y., et al. (2012). Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082

Eskeland, R., Leeb, M., Grimes, G. R., Kress, C., Boyle, S., Sproul, D., et al. (2010). Ring1B compacts chromatin structure and represses gene expression independent of histone ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. 38, 452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.032

Eymery, A., Liu, Z., Ozonov, E. A., Stadler, M. B., and Peters, A. H. (2016). The methyltransferase Setdb1 is essential for meiosis and mitosis in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Development 143, 2767–2779. doi: 10.1242/dev.132746

Falk, M., Feodorova, Y., Naumova, N., Imakaev, M., Lajoie, B. R., Leonhardt, H., et al. (2018). Heterochromatin drives organization of conventional and inverted nuclei. BioRxiv Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/244038

Francis, N. J., Kingston, R. E., and Woodcock, C. L. (2004). Chromatin compaction by a polycomb group protein complex. Science 306, 1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1100576

Frank, C. L., Liu, F., Wijayatunge, R., Song, L., Biegler, M. T., Yang, M. G., et al. (2015). Regulation of chromatin accessibility and Zic binding at enhancers in the developing cerebellum. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 647–656. doi: 10.1038/nn.3995

Fraser, J., Ferrai, C., Chiariello, A. M., Schueler, M., Rito, T., Laudanno, G., et al. (2015). Hierarchical folding and reorganization of chromosomes are linked to transcriptional changes in cellular differentiation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11:852. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156492

Freire-Pritchett, P., Schoenfelder, S., Várnai, C., Wingett, S. W., Cairns, J., Collier, A. J., et al. (2017). Global reorganisation of cis-regulatory units upon lineage commitment of human embryonic stem cells. Elife 6:699. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21926

Fudenberg, G., Imakaev, M., Lu, C., Goloborodko, A., Abdennur, N., and Mirny, L. A. (2016). Formation of chromosomal domains by loop extrusion. Cell Rep. 15, 2038–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085

Fujita, Y., Masuda, K., Bando, M., Nakato, R., Katou, Y., Tanaka, T., et al. (2017). Decreased cohesin in the brain leads to defective synapse development and anxiety-related behavior. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1431–1452. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161517

Gallegos, D. A., Chan, U., Chen, L.-F., and West, A. E. (2018). Chromatin regulation of neuronal maturation and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 41, 311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.02.009

Ganji, M., Shaltiel, I. A., Bisht, S., Kim, E., Kalichava, A., Haering, C. H., et al. (2018). Real-time imaging of DNA loop extrusion by condensin. Science 360, 102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7831

Gaspard, N., and Vanderhaeghen, P. (2010). Mechanisms of neural specification from embryonic stem cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.001

Gaspar-Maia, A., Alajem, A., Polesso, F., Sridharan, R., Mason, M. J., Heidersbach, A., et al. (2009). Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 460, 863–868. doi: 10.1038/nature08212

Grau, D. J., Chapman, B. A., Garlick, J. D., Borowsky, M., Francis, N. J., and Kingston, R. E. (2011). Compaction of chromatin by diverse Polycomb group proteins requires localized regions of high charge. Genes Dev. 25, 2210–2221. doi: 10.1101/gad.17288211

Güttinger, S., Laurell, E., and Kutay, U. (2009). Orchestrating nuclear envelope disassembly and reassembly during mitosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 178–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm2641

Haarhuis, J. H. I., van der Weide, R. H., Blomen, V. A., Yáñez-Cuna, J. O., Amendola, M., van Ruiten, M. S., et al. (2017). The cohesin release factor WAPL restricts chromatin loop extension. Cell 169, 693–707.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.013

Hansen, A. S., Cattoglio, C., Darzacq, X., and Tjian, R. (2018). Recent evidence that TADs and chromatin loops are dynamic structures. Nucleus 9, 20–32. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2017.1389365

Hetman, M., and Pietrzak, M. (2012). Emerging roles of the neuronal nucleolus. Trends Neurosci. 35, 305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.002

Hirayama, T., Tarusawa, E., Yoshimura, Y., Galjart, N., and Yagi, T. (2012). CTCF is required for neural development and stochastic expression of clustered Pcdh genes in neurons. Cell Rep. 2, 345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.014

Hnisz, D., Abraham, B. J., Lee, T. I., Lau, A., Saint-André, V., Sigova, A. A., et al. (2013). Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155, 934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053

Isono, K., Endo, T. A., Ku, M., Yamada, D., Suzuki, R., Sharif, J., et al. (2013). SAM domain polymerization links subnuclear clustering of PRC1 to gene silencing. Dev. Cell 26, 565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.016

Javierre, B. M., Burren, O. S., Wilder, S. P., Kreuzhuber, R., Hill, S. M., Sewitz, S., et al. (2016). Lineage-specific genome architecture links enhancers and non-coding disease variants to target gene promoters. Cell 167, 1369–1384.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.037

Jiang, Y., Loh, Y.-H. E., Rajarajan, P., Hirayama, T., Liao, W., Kassim, B. S., et al. (2017). The methyltransferase SETDB1 regulates a large neuron- specific topological chromatin domain. Nat. Genet. 49, 1239–1250. doi: 10.1038/ng.3906

Kim, C. A., Gingery, M., Pilpa, R. M., and Bowie, J. U. (2002). The SAM domain of polyhomeotic forms a helical polymer. Nat. Struct Biol. 9, 453–457.

Kim, J., Zhao, H., Dan, J., Kim, S., Hardikar, S., Hollowell, D., et al. (2016). Maternal setdb1 is required for meiotic progression and preimplantation development in mouse. PLoS Genet. 12:e1005970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005970

Kind, J., Pagie, L., de Vries, S. S., Nahidiazar, L., Dey, S. S., Bienko, M., et al. (2015). Genome-wide maps of nuclear lamina interactions in single human cells. Cell 163, 134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.040

Kishi, Y., Fujii, Y., Hirabayashi, Y., and Gotoh, Y. (2012a). HMGA regulates the global chromatin state and neurogenic potential in neocortical precursor cells. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1127–1133.

Kishi, Y., Kondo, S., and Gotoh, Y. (2012b). Transcriptional activation of mouse major satellite regions during neuronal differentiation. Cell Struct. Funct. 37, 101–110.

Kondo, T., Isono, K., Kondo, K., Endo, T. A., Itohara, S., Vidal, M., et al. (2014). Polycomb potentiates meis2 activation in midbrain by mediating interaction of the promoter with a tissue-specific enhancer. Dev. Cell 28, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.021

Krantz, I. D., McCallum, J., DeScipio, C., Kaur, M., Gillis, L. A., Yaeger, D., et al. (2004). Cornelia de Lange syndrome is caused by mutations in NIPBL, the human homolog of Drosophila melanogaster Nipped-B. Nat. Genet. 36, 631–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1364

Kundu, S., Ji, F., Sunwoo, H., Jain, G., Lee, J. T., Sadreyev, R. I., et al. (2017). Polycomb Repressive complex 1 generates discrete compacted domains that change during differentiation. Mol. Cell 65, 432–446.e435. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.009

Larson, A. G., Elnatan, D., Keenen, M. M., Trnka, M. J., Johnston, J. B., Burlingame, A. L., et al. (2017). Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547, 236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature22822

Le Gros, M. A., Clowney, E. J., Magklara, A., Yen, A., Markenscoff-Papadimitriou, E., Colquitt, B., et al. (2016). Soft x-ray tomography reveals gradual chromatin compaction and reorganization during neurogenesis in vivo. Cell Rep. 17, 2125–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.060

Levine, A. J., and Brivanlou, A. H. (2007). Proposal of a model of mammalian neural induction. Dev. Biol. 308, 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.036

Li, G., Ruan, X., Auerbach, R. K., Sandhu, K. S., Zheng, M., Wang, P., et al. (2012). Extensive promoter-centered chromatin interactions provide a topological basis for transcription regulation. Cell 148, 84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.014

Lieberman-Aiden, E., van Berkum, N. L., Williams, L., Imakaev, M., Ragoczy, T., Telling, A., et al. (2009). Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369

Liu, S., Brind’Amour, J., Karimi, M. M., Shirane, K., Bogutz, A., Lefebvre, L., et al. (2014). Setdb1 is required for germline development and silencing of H3K9me3-marked endogenous retroviruses in primordial germ cells. Genes Dev. 28, 2041–2055. doi: 10.1101/gad.244848.114

Lupiáñez, D. G., Kraft, K., Heinrich, V., Krawitz, P., Brancati, F., Klopocki, E., et al. (2015). Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell 161, 1012–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004

Macosko, E. Z., Basu, A., Satija, R., Nemesh, J., Shekhar, K., Goldman, M., et al. (2015). Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002

Manuel, M. N., Mi, D., Mason, J. O., and Price, D. J. (2015). Regulation of cerebral cortical neurogenesis by the Pax6 transcription factor. Front. Cell Neurosci. 9:70. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00070

Margueron, R., Li, G., Sarma, K., Blais, A., Zavadil, J., Woodcock, C. L., et al. (2008). Ezh1 and Ezh2 maintain repressive chromatin through different mechanisms. Mol. Cell. 32, 503–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.004

Meshorer, E., Yellajoshula, D., George, E., Scambler, P. J., Brown, D. T., and Misteli, T. (2006). Hyperdynamic plasticity of chromatin proteins in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Dev. Cell 10, 105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.017

Mifsud, B., Tavares-Cadete, F., Young, A. N., Sugar, R., Schoenfelder, S., Ferreira, L., et al. (2015). Mapping long-range promoter contacts in human cells with high-resolution capture Hi-C. Nat. Genet. 47, 598–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.3286

Mitchell, A. C., Bharadwaj, R., Whittle, C., Krueger, W., Mirnics, K., Hurd, Y., et al. (2014). The genome in three dimensions: a new frontier in human brain research. Biol. Psychiatry 75, 961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.015

Nagano, T., Lubling, Y., Stevens, T. J., Schoenfelder, S., Yaffe, E., Dean, W., et al. (2013). Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature 502, 59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature12593

Narendra, V., Bulajić, M., Dekker, J., Mazzoni, E. O., and Reinberg, D. (2016). CTCF-mediated topological boundaries during development foster appropriate gene regulation. Genes Dev. 30, 2657–2662. doi: 10.1101/gad.288324.116

Ninkovic, J., Steiner-Mezzadri, A., Jawerka, M., Akinci, U., Masserdotti, G., Petricca, S., et al. (2013). The BAF complex interacts with pax6 in adult neural progenitors to establish a neurogenic cross-regulatory transcriptional network. Cell Stem Cell 13, 403–418. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.002

Nora, E. P., Goloborodko, A., Valton, A.-L., Gibcus, J. H., Uebersohn, A., Abdennur, N., et al. (2017). Targeted degradation of CTCF decouples local insulation of chromosome domains from genomic compartmentalization. Cell 169, 930–944.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.004

Nora, E. P., Lajoie, B. R., Schulz, E. G., Giorgetti, L., Okamoto, I., Servant, N., et al. (2012). Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature 485, 381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature11049

Padeken, J., and Heun, P. (2014). Nucleolus and nuclear periphery: velcro for heterochromatin. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 28, 54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.03.001

Parker, S. C. J., Stitzel, M. L., Taylor, D. L., Orozco, J. M., Erdos, M. R., Akiyama, J. A., et al. (2013). Chromatin stretch enhancer states drive cell-specific gene regulation and harbor human disease risk variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 17921–17926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317023110

Peric-Hupkes, D., Meuleman, W., Pagie, L., Bruggeman, S. W. M., Solovei, I., Brugman, W., et al. (2010). Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Mol. Cell. 38, 603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.016

Preissl, S., Fang, R., Huang, H., Zhao, Y., Raviram, R., Gorkin, D. U., et al. (2018). Single-nucleus analysis of accessible chromatin in developing mouse forebrain reveals cell-type-specific transcriptional regulation. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 432–439. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0079-3

Quinodoz, S. A., Ollikainen, N., Tabak, B., Palla, A., Schmidt, J. M., Detmar, E., et al. (2018). Higher-order inter-chromosomal hubs shape 3d genome organization in the nucleus. Cell 174, 744–757.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.024

Rao, S. S. P., Huang, S.-C., Glenn St Hilaire, B., Engreitz, J. M., Perez, E. M., Kieffer-Kwon, K.-R., et al. (2017). Cohesin loss eliminates all loop domains. Cell 171, 305–320.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.026

Rao, S. S. P., Huntley, M. H., Durand, N. C., Stamenova, E. K., Bochkov, I. D., Robinson, J. T., et al. (2014). A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021

Renda, M., Baglivo, I., Burgess-Beusse, B., Esposito, S., Fattorusso, R., Felsenfeld, G., et al. (2007). Critical DNA binding interactions of the insulator protein CTCF: a small number of zinc fingers mediate strong binding, and a single finger-DNA interaction controls binding at imprinted loci. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33336–33345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706213200

Ricci, M. A., Cosma, M. P., and Lakadamyali, M. (2017). Super resolution imaging of chromatin in pluripotency, differentiation, and reprogramming. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 46, 186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.07.010

Rino, J., Carvalho, T., Braga, J., Desterro, J. M. P., Lührmann, R., and Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2007). A stochastic view of spliceosome assembly and recycling in the nucleus. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, 2019–2031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030201

Rotem, A., Ram, O., Shoresh, N., Sperling, R. A., Goren, A., Weitz, D. A., et al. (2015). Single-cell ChIP-seq reveals cell subpopulations defined by chromatin state. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1165–1172. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3383

Sams, D. S., Nardone, S., Getselter, D., Raz, D., Tal, M., Rayi, P. R., et al. (2016). Neuronal CTCF is necessary for basal and experience-dependent gene regulation, memory formation, and genomic structure of BDNF and arc. Cell Rep. 17, 2418–2430. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.004

Sanborn, A. L., Rao, S. S. P., Huang, S.-C., Durand, N. C., Huntley, M. H., Jewett, A. I., et al. (2015). Chromatin extrusion explains key features of loop and domain formation in wild-type and engineered genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E6456–E6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518552112

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2014). Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595

Schoenfelder, S., Sugar, R., Dimond, A., Javierre, B.-M., Armstrong, H., Mifsud, B., et al. (2015). Polycomb repressive complex PRC1 spatially constrains the mouse embryonic stem cell genome. Nat. Genet. 47, 1179–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3393

Schultz, D. C., Ayyanathan, K., Negorev, D., Maul, G. G., and Rauscher, F. J. (2002). SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 16, 919–932. doi: 10.1101/gad.973302

Schwarzer, W., Abdennur, N., Goloborodko, A., Pekowska, A., Fudenberg, G., Loe-Mie, Y., et al. (2017). Two independent modes of chromatin organization revealed by cohesin removal. Nature 551, 51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature24281

Shalek, A. K., Satija, R., Shuga, J., Trombetta, J. J., Gennert, D., Lu, D., et al. (2014). Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic paracrine control of cellular variation. Nature 510, 363–369. doi: 10.1038/nature13437

Solovei, I., Grandi, N., Knoth, R., Volk, B., and Cremer, T. (2004). Positional changes of pericentromeric heterochromatin and nucleoli in postmitotic Purkinje cells during murine cerebellum. Cytogenet. Genome. Res. 105, 302–310. doi: 10.1159/000078202

Solovei, I., Kreysing, M., LanctOt, C., KOsem, S., Peichl, L., Cremer, T., et al. (2009). Nuclear architecture of rod photoreceptor cells adapts to vision in mammalian evolution. Cell 137, 356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.052

Solovei, I., Wang, A. S., Thanisch, K., Schmidt, C. S., Krebs, S., Zwerger, M., et al. (2013). LBR and Lamin A/C sequentially tether peripheral heterochromatin and inversely regulate differentiation. Cell 152, 584–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.009

Stevens, T. J., Lando, D., Basu, S., Atkinson, L. P., Cao, Y., Lee, S. F., et al. (2017). 3D structures of individual mammalian genomes studied by single-cell Hi-C. Nature 544, 59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature21429

Strom, A. R., Emelyanov, A. V., Mir, M., Fyodorov, D. V., Darzacq, X., and Karpen, G. H. (2017). Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547, 241–245. doi: 10.1038/nature22989

Sutherland, H., and Bickmore, W. A. (2009). Transcription factories: gene expression in unions? Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 457–466. doi: 10.1038/nrg2592

Symmons, O., Pan, L., Remeseiro, S., Aktas, T., Klein, F., Huber, W., et al. (2016). The Shh topological domain facilitates the action of remote enhancers by reducing the effects of genomic distances. Dev. Cell 39, 529–543. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.10.015

Takikita, S., Muro, R., Takai, T., Otsubo, T., Kawamura, Y. I., Dohi, T., et al. (2016). A Histone Methyltransferase ESET Is Critical for T Cell Development. J. Immunol. 197, 2269–2279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502486

Tan, S.-L., Nishi, M., Ohtsuka, T., Matsui, T., Takemoto, K., Kamio-Miura, A., et al. (2012). Essential roles of the histone methyltransferase ESET in the epigenetic control of neural progenitor cells during development. Development 139, 3806–3816. doi: 10.1242/dev.082198

Tang, Z., Luo, O. J., Li, X., Zheng, M., Zhu, J. J., Szalaj, P., et al. (2015). CTCF-mediated human 3d genome architecture reveals chromatin topology for transcription. Cell 163, 1611–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.024

Thakurela, S., Sahu, S. K., Garding, A., and Tiwari, V. K. (2015). Dynamics and function of distal regulatory elements during neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. Genome Res. 25, 1309–1324. doi: 10.1101/gr.190926.115

Tonkin, E. T., Wang, T.-J., Lisgo, S., Bamshad, M. J., and Strachan, T. (2004). NIPBL, encoding a homolog of fungal Scc2-type sister chromatid cohesion proteins and fly Nipped-B, is mutated in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Nat. Genet. 36, 636–641. doi: 10.1038/ng1363

Tsuboi, M., Kishi, Y., Yokozeki, W., Koseki, H., Hirabayashi, Y., and Gotoh, Y. (2018). Ubiquitination-independent repression of PRC1 targets during neuronal fate restriction in the developing mouse neocortex. Dev. Cell doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.11.018

Tyssowski, K., Kishi, Y., and Gotoh, Y. (2014). Chromatin regulators of neural development. Neuroscience 264, 4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.008

van de Werken, H. J. G., Landan, G., Holwerda, S. J. B., Hoichman, M., Klous, P., Chachik, R., et al. (2012). Robust 4C-seq data analysis to screen for regulatory DNA interactions. Nat. Methods 9, 969–972. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2173

van Steensel, B., and Belmont, A. S. (2017). Lamina-associated domains: links with chromosome architecture, heterochromatin, and gene repression. Cell 169, 780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.022

Vernimmen, D., and Bickmore, W. A. (2015). The hierarchy of transcriptional activation: from enhancer to promoter. Trends Genet. 31, 696–708. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.10.004

Wang, H., Maurano, M. T., Qu, H., Varley, K. E., Gertz, J., Pauli, F., et al. (2012). Widespread plasticity in CTCF occupancy linked to DNA methylation. Genome Res. 22, 1680–1688. doi: 10.1101/gr.136101.111

Wani, A. H., Boettiger, A. N., Schorderet, P., Ergun, A., Münger, C., Sadreyev, R. I., et al. (2016). Chromatin topology is coupled to Polycomb group protein subnuclear organization. Nat. Commun. 7:10291. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10291

Watson, L. A., Wang, X., Elbert, A., Kernohan, K. D., Galjart, N., and Bérubé, N. G. (2014). Dual effect of CTCF loss on neuroprogenitor differentiation and survival. J. Neurosci. 34, 2860–2870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3769-13.2014

Weintraub, A. S., Li, C. H., Zamudio, A. V., Sigova, A. A., Hannett, N. M., Day, D. S., et al. (2017). YY1 is a structural regulator of enhancer- promoter loops. Cell 171, 1573–1579.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.008

Wittmann, M., Queisser, G., Eder, A., Wiegert, J. S., Bengtson, C. P., Hellwig, A., et al. (2009). Synaptic activity induces dramatic changes in the geometry of the cell nucleus: interplay between nuclear structure, histone H3 phosphorylation, and nuclear calcium signaling. J. Neurosci. 29, 14687–14700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1160-09.2009

Won, H., de la Torre-Ubieta, L., Stein, J. L., Parikshak, N. N., Huang, J., Opland, C. K., et al. (2016). Chromosome conformation elucidates regulatory relationships in developing human brain. Nature 538, 523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature19847

Yagi, T. (2012). Molecular codes for neuronal individuality and cell assembly in the brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5:45. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00045

Yakushiji-Kaminatsui, N., Kondo, T., Endo, T. A., Koseki, Y., Kondo, K., Ohara, O., et al. (2016). RING1 proteins contribute to early proximal-distal specification of the forelimb bud by restricting Meis2 expression. Development 143, 276–285. doi: 10.1242/dev.127506

Zhan, Y., Mariani, L., Barozzi, I., Schulz, E. G., Blüthgen, N., Stadler, M., et al. (2017). Reciprocal insulation analysis of Hi-C data shows that TADs represent a functionally but not structurally privileged scale in the hierarchical folding of chromosomes. Genome Res. 27, 479–490. doi: 10.1101/gr.212803.116

Keywords: neural development, chromatin, chromatin conformation capture (3C), topologically associated domain (TAD), A/B compartments

Citation: Kishi Y and Gotoh Y (2018) Regulation of Chromatin Structure During Neural Development. Front. Neurosci. 12:874. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00874

Received: 06 September 2018; Accepted: 09 November 2018;

Published: 11 December 2018.

Edited by:

Mareike Albert, Max-Planck-Institut für Molekulare Zellbiologie und Genetik, GermanyReviewed by:

Boyan Bonev, German Research Center for Environmental Health (HZ), GermanyCopyright © 2018 Kishi and Gotoh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yusuke Kishi, eWtpc2lAbW9sLmYudS10b2t5by5hYy5qcA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.