95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Neurosci. , 09 June 2022

Sec. Motor Neuroscience

Volume 16 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.868074

This article is part of the Research Topic Using Technology to Advance Balance and Gait Rehabilitation for Individuals with Neurological Pathologies View all 6 articles

Emily Evans1,2

Emily Evans1,2 Megan Dass3

Megan Dass3 William M. Muter1

William M. Muter1 Christopher Tuthill1,2

Christopher Tuthill1,2 Andrew Q. Tan2,4

Andrew Q. Tan2,4 Randy D. Trumbower1,2*

Randy D. Trumbower1,2*Humans routinely modify their walking speed to adapt to functional goals and physical demands. However, damage to the central nervous system (CNS) often results in abnormal modulation of walking speed and increased risk of falls. There is considerable interest in treatment modalities that can provide safe and salient training opportunities, feedback about walking performance, and that may augment less reliable sensory feedback within the CNS after injury or disease. Fully immersive virtual reality technologies show benefits in boosting training-related gains in walking performance; however, they lack views of the real world that may limit functional carryover. Augmented reality and mixed reality head-mount displays (MR-HMD) provide partially immersive environments to extend the virtual reality benefits of interacting with virtual objects but within an unobstructed view of the real world. Despite this potential advantage, the feasibility of using MR-HMD visual feedback to promote goal-directed changes in overground walking speed remains unclear. Thus, we developed and evaluated a novel mixed reality application using the Microsoft HoloLens MR-HMD that provided real-time walking speed targets and augmented visual feedback during overground walking. We tested the application in a group of adults not living with disability and examined if they could use the targets and visual feedback to walk at 85%, 100%, and 115% of each individual’s self-selected speed. We examined whether individuals were able to meet each target gait speed and explored differences in accuracy across repeated trials and at the different speeds. Additionally, given the importance of task-specificity to therapeutic interventions, we examined if walking speed adjustment strategies were consistent with those observed during usual overground walking, and if walking with the MR-HMD resulted in increased variability in gait parameters. Overall, participants matched their overground walking speed to the target speed of the MR-HMD visual feedback conditions (all p-values > 0.05). The percent inaccuracy was approximately 5% across all speed matching conditions and remained consistent across walking trials after the first overall walking trial. Walking with the MR-HMD did not result in more variability in walking speed, however, we observed more variability in stride length and time when walking with feedback from the MR-HMD compared to walking without feedback. The findings offer support for mixed reality-based visual feedback as a method to provoke goal-specific changes in overground walking behavior. Further studies are necessary to determine the clinical safety and efficacy of this MR-HMD technology to provide extrinsic sensory feedback in combination with traditional treatments in rehabilitation.

Walking speed is a predictor of functional independence, health, and mortality risk (Schmid et al., 2007; Middleton et al., 2015). Humans modify their walking to negotiate different walking terrains and obstacles (Glaister et al., 2007; Orendurff et al., 2008). These adjustments occur through regulatory networks within the central nervous system (CNS) that transform afferent information (e.g., proprioception) to motor outputs based on the interactions between the limb and the physical demands of the task (i.e., functional walking). Deficits in the sensory feedback system are known to contribute to increased incidence of walking-related falls in older adults (Afilalo et al., 2010; Artaud et al., 2015) and persons with neuromuscular injury or disease (Perry et al., 1995; Hausdorff et al., 2001; Dodge et al., 2012). There is considerable interest in treatment modalities that can provide salient training opportunities, feedback about walking performance, and may augment less reliable or weak afferent signaling to help improve walking ability and decrease risk for fall in these at-risk groups.

Studies confirm that visual feedback provided through virtual environments enhances walking ability (Schliessmann et al., 2014; Gomez-Jordana et al., 2018). Technologies that provide visual information and feedback include head-mounted displays (HMD), monitors, or large screen projectors (e.g., cave automatic virtual environment, CAVE) to create partially or fully immersive environments (Bishop and Fuchs, 1992; Milgram et al., 1995). Some studies support the use of fully immersive virtual reality (VR) for walking rehabilitation (Borrego et al., 2016; Janeh and Steinicke, 2021). These virtual environments rely on “walking-in-place” or “redirected walking” strategies to emulate features of the real world. While these gaming-related strategies provide engagement and motivation (Lohse et al., 2013), they do not fully capture the dynamic challenges of overground walking in a person’s home or community. For instance, the “walking-in-place” training programs often involve a treadmill that introduces biomechanical differences to overground walking (Dingwell et al., 2001; Lee and Hidler, 2008; Hollman et al., 2016; Ochoa et al., 2017), and this discrepancy may dampen carryover of the treadmill training to overground walking tasks. Consideration for more ecologically favorable augmented reality environments is of high value in the rehabilitation community.

Mixed reality (MR) technology is emerging as a promising approach to accommodate the real-world challenges of relearning to walk in the home or community after injury or disease. Mixed reality incorporates computer-rendered objects within an unobstructed view of the real world and enables real-time interactions with these virtual elements (O’Connell, 2016). In 2016, Microsoft introduced the HoloLens (HoloLens 1st Generation, Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA), a head-mounted MR system that includes an inertial measurement unit, environment sensing cameras, and a holographic display. A pair of recent studies found the potential utility of the HoloLens as a gait assessment tool to track spatiotemporal gait parameters (Geerse et al., 2020; Guinet et al., 2021) reporting the system reliable at test-retest parameterization of walking speed (interclass correlation coefficient, ICC = 0.86), cadence (ICC = 0.88), and step length (ICC = 0.77). Additionally, Coolen and colleagues developed a training tool to facilitate virtual obstacle-avoidance training with the HoloLens (Coolen et al., 2020). They found the virtual obstacle avoidance task elicited lead and lag step height maneuvers similar to a physical obstacle-avoidance task during overground walking in adults living without disability. This prior work indicates that MR is achievable for assessing overground walking behavior and creating realistic environmental challenges; however, the potential of MR to induce modulation of overground walking behavior (i.e., speed) is not known.

The purpose of this study is to examine the feasibility of MR-based visual feedback to promote goal-directed changes in overground walking in preparation for future intervention studies aimed at identifying effective strategies for improving gait speed, stability, and ability to adjust walking to environmental demands. As a first step, we examine the use of a MR-HMD and a novel visual feedback platform in adults living without a known walking impairment. Specifically, we examine how accurately this group of individuals can match a target speed provided by the MR-HMD, if the accuracy changes with practice using the device or at different target speeds, if individuals use expected strategies to adjust gait speed, and if using the MR-HMD results in any additional variability in gait speed or parameters that should be considered when designing future trials. We predicted that participants would adjust their walking speed to match the visual guidance of a custom MR-HMD platform. We quantified the performance of participants interacting with the MR-HMD platform in terms of speed matching accuracy across trials and between walking speed conditions. We examined if individuals adjusted gait parameters as expected when adjusting gait speed. Finally, we compared changes and variability of walking speed parameters (i.e., stride length and time) during self-selected walking with and without the MR-based visual feedback.

We conducted a block-randomized, cross-over intervention study to test the hypothesis that a novel MR-based visual feedback platform is a feasible method to elicit modulation of overground walking speed in adults not living with disability. The study took place at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, USA.

We enrolled 12 adults, not living with disability, to participate in the single-day study (Table 1). Eligible participants included persons between the ages of 18 and 75 years with the ability to follow two-step commands and to walk overground without assistance. We excluded individuals with uncorrected moderate to severe visual impairments, movement deficits, or neuromuscular impairments. Eligible participants meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria provided informed consent prior to study participation. We obtained study approval from the Mass General Brigham institutional review board.

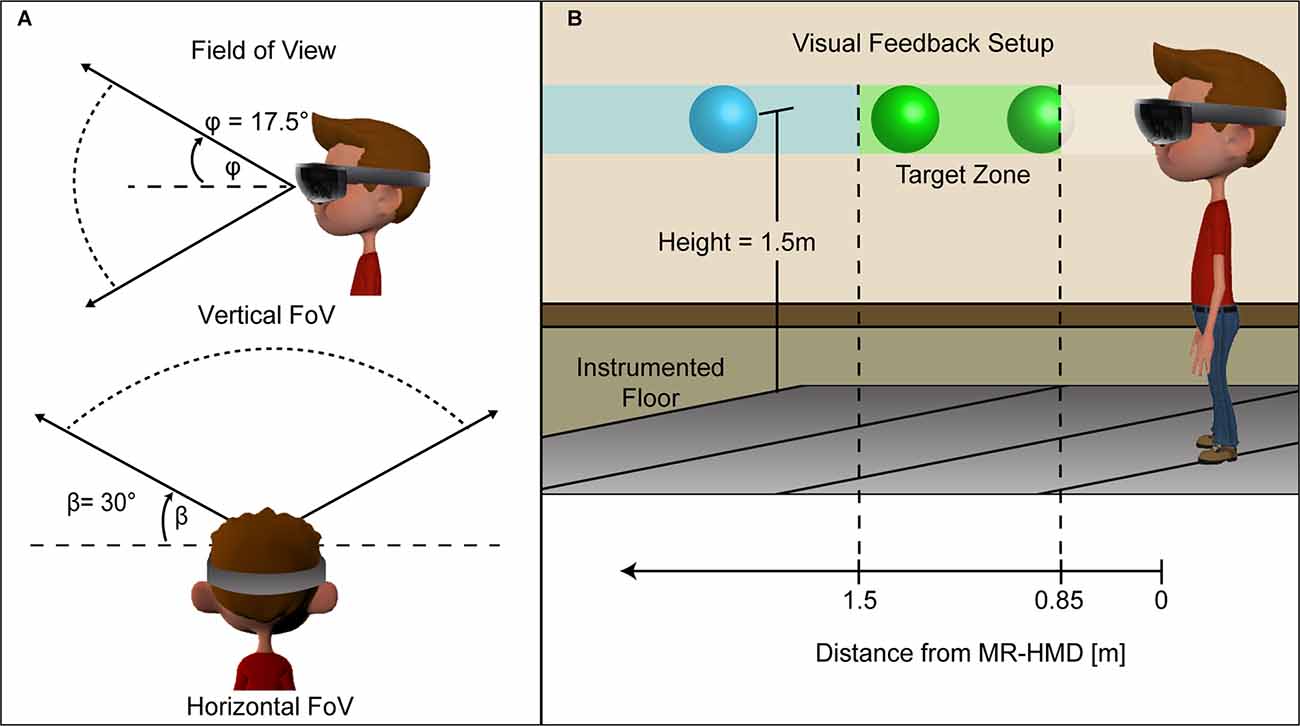

We implemented real-time visual feedback using the Microsoft HoloLens, a commercially available MR-HMD (HoloLens 1st Generation, Model 1688, Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA). The MR-HMD implemented the Windows Mixed Reality platform (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA) to allow viewing of virtual objects overlaid onto a real-world environment via a transparent visor having a fixed field of view (Figure 1A). The headband diameter and fore-aft location of the MR-HMD are both adjustable to ensure user comfort and visual quality. The technology included a time-of-flight depth-sensing camera, four tracking cameras, and an inertial measurement unit consisting of a multidimensional accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer. The sensors enabled the MR-HMD system to define the headset’s location relative to the three-dimensional physical environment (Hubner et al., 2020). Based on these inputs, the MR-HMD system updated the location, depth, and orientation of the holographic display (Kubben and Sinlae, 2019).

Figure 1. Visualization of the HoloLens MR-HMD. The image on the left (A) shows the vertical and horizontal field of view for rendered holographic objects. The visual feedback (B) consisted of a floating holographic ball in different sections based on distance from the HMD. When maintaining the target speed, the ball remains between 1.5 m and 0.85 m from the subject and is colored green. If the subject walked too slowly and the ball was beyond 1.5 m its color changed to blue providing additional feedback that the user should walk faster. The ball clipped when it was less than 0.85 m from the HMD indicating that the subject should walk more slowly.

A custom MR-HMD user interface provided personalized real-time visual feedback for modulating walking speed. The interface included a moving hologram that served as the speed-matching target and the real-time feedback of the participant’s speed-matching accuracy. The visual feedback consisted of a 10 cm translucent holographic ball that moved along a 10 m path at a fixed height of 1.5 m above the ground (Figure 1B). We developed this graphical interface using a cross-platform game engine (Unity version 5.5.0f3, Unity Technologies, San Francisco, CA) and C# (Visual Studio 2017, Microsoft Inc, Redmond, WA). As the HoloLens only rendered a single holographic object to provide the continuous visual feedback the frame rate was synced to the MR-HMD refresh rate of 60 Hz to prevent tearing artifacts (Lee et al., 2017).

We recorded the participants’ walking kinematics using a 14 m instrumented walkway (GAITRite CIRFace, CIR Systems Inc., Franklin, NJ). The walkway has high test-retest reliability, concurrent validity within and between systems, and used previously to assess overground walking in persons living with and without movement related disability (Thibaudier et al., 2020). We acquired the kinematic data in the sagittal plane at a sampling rate 100 Hz over a 10 m distance. Participants walked a total of 14 m that included 2 m before and after the 10 m collection area; this reduced potential confounding effects of initial and final accelerations on the walking kinematics. Using a secure desktop computer, we stored video and kinematic data for further data processing and statistical analyses.

We fitted each participant to the MR-HMD technology. The experiment team aided participants with donning the device and adjusting the head straps for their comfort. Participants wore their usual corrective eyewear. Once fitted, participants learned to interact with the MR interface using various simple hand gestures. This included a calibration procedure that ensured the holographic display aligned with the user’s visual field. The calibration protocol involved a Microsoft Windows Mixed Reality alignment routine to estimate the user’s interpupillary distance based on a series of finger target-matching tasks for each eye. The MR-HMD platform then incorporated the calibration transform to modify the holographic ball orientation within the real-world environment. Once calibrated, the 10 m walking course was defined over the instrumented walkway using the holographic interface. Completion of the MR-HMD fitting and calibration procedures took approximately 10 min.

The experimental protocol required participants to complete a baseline walking assessment. We instructed participants to walk at their self-selected (SS) walking speed across the instrumented walkway. During baseline trials, the MR-HMD was worn in the powered-down state such that individuals could see their environment but could not see any holographic elements. We did this to control for any passive effects of the device unrelated to visual feedback. Participants completed 10 baseline trials at their SS walking speed. This baseline assessment took approximately 10 min.

We programmed the visual feedback so that the holographic ball moved at speeds corresponding to three walking speed conditions: 85% (SS85), 100% (SS100), and 115% (SS115; Hayes et al., 2014) of the baseline SS without visual feedback. We chose to evaluate walking at SS speeds to understand the utility of MR-HMD during speed conditions that are relevant to community walking (Bowden et al., 2008; Talkowski et al., 2008; Stevens et al., 2013). Additionally, a variety of walking speeds were used to acquire a rich set of stepping patterns for exploring kinematic variability that represents a range of possible community walking speeds (van Hedel et al., 2006). We block-randomized the order of these walking conditions for each participant.

At the start of a walking condition, we informed participants that a holographic ball will move in the forward direction at a constant speed. To prepare participants for the ball’s movement, we implemented a visual countdown signal of the holographic ball blinking yellow four times before changing to solid green. Participants received instruction to maintain their initial distance (~1.0 m) behind the moving holographic ball. Participants remained blinded to the speed of the holographic ball during the protocol. We instructed the participants that the color of the moving ball indicated their performance. If the distance between the ball and participant stayed within the range of 0.85–1.5 m, the ball color remained green. If this distance exceeded 1.5 m, the ball color changed to blue indicating the participant needed to walk faster. If this distance did not reach 0.85 m, the ball disappeared indicating that the participant walked past the ball and needed to walk slower (Figure 1B). Participants completed ten trials at each walking condition and received rest breaks between blocks as needed to minimize fatigue. This evaluation took approximately 30 min.

We quantified three overground walking parameters: walking speed, stride length, and stride time. We recorded walking speed, as the distance walked per trial divided by the duration of time to complete the trial. The stride length corresponded to the distance between the first contact of two consecutive steps of the same foot and stride time corresponded to the duration of time to complete a stride (Perry and Burnfield, 2010). Since our estimates of stride parameters did not differ between legs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p-values > 0.20), we combined left and right strides for all analyses.

We assessed the participants’ speed-matching ability using two methods. First, we calculated the percent difference in walking speed across all walking trials for a condition and examined if it was as expected for each condition, i.e., 15% slower, equal to, or 15% faster than the baseline condition. Next, to determine if the speed of the holographic ball influenced how well participants walking speed matched the ball’s speed, we calculated the percent inaccuracy for each walking trial. The percent inaccuracy is equal to the absolute percent difference between target walking speed and actual walking speed for each walking condition (SS85, SS100, SS115). Lastly, to assess step-to-step consistency in walking, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CoV), a unitless measure of variability, within individual and across walking trials for each walking parameter. The CoV was calculated for each parameter (gait speed, stride length and stride time) using the following formula CoV = σ/μ where μ is the mean value by individual and walking speed condition σ is the standard deviation by individual and walking speed condition.

We used Stata 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for statistical analysis. To examine the effect of practice, we tested for time-dependent changes in trial inaccuracy over the 10 walking trials of each walking condition using a linear mixed model with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. We utilized a linear mixed model to account for the repeated effects of participant, walking condition, and to allow for flexibility in the number of walking trials per condition (Davis, 2002). The model included participant random effects and a distinct covariance structure for the repeated effect of experimental conditions. We also included fixed effects of trial number, a variable reflecting if the condition was the first, second, or third tested condition, and their interaction. We calculated the marginal means values based on the interaction of trial number and condition order and conducted pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections to compare the means. We hypothesized that participants may exhibit more inaccuracy during their first several trials as they learned to use the device. To avoid the potential confound of higher inaccuracy in the early trials, we planned to remove early trials, starting with the first trial until a consistent rate of accuracy was achieved. Second, to determine if our participants were able to match the target gait speed, we utilized a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine if the median percent difference between the target walking speed and the actual walking speed corresponded to the expected percent difference for each walking condition, i.e., −15% for SS85, 0% for SS100, and 15% for SS115.

Next, we utilized linear mixed models to examine percent inaccuracy and variability in gait speed, stride length, and stride time across multiple walking conditions using linear mixed models. We examined if participants ability to meet the target speed differed by walking speed by comparing the percent inaccuracy across the three tested speeds (SS85, SS100, SS115). Due to the importance of task-specificity in gait training interventions (Kleim and Jones, 2008), we examined if adjustments to stride length and stride time were consistent with the adjustment strategies used by healthy adults to achieve changes in overground gait speed. Specifically, healthy adults adjust stride length and stride time in opposite but equal amounts to achieve changes in gait speed (Murray et al., 1969, 1970). We examined the magnitude of the percent difference in stride length and stride time between the SS85 and SS100 conditions, and the SS100 and SS115 conditions. Because the adjustments to stride length and time are expected to be in opposite directions, we compared the additive inverse of stride length to stride time. Finally, to determine if receiving visual feedback from the MR-HMD induced additional variability in gait speed or the associated parameters, we compared the CoV of stride length, stride time, and gait speed between the baseline condition (Self-Selected Speed, MR-HMD turned off) and the SS100 (Self-Selected speed, visual feedback from the MR-HMD.).

Each model included participant random effects and a distinct covariance structure for the repeated effect of experimental condition. The design for modeling residuals and the between-subject covariance structure was determined by comparing Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) between models (Akaike, 1974). For each model, we calculated marginal means and utilized pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections to compare the marginal effects between experimental conditions. Specifically, to examine the effect of the MR-HMD feedback at the same speed, we compared marginal effects between the baseline and SS100 experimental conditions. We also examined the effect of walking speed changes by comparing the adjusted mean values between the experimental conditions (SS85, SS100, SS115). The significance of any interactions was examined using an omnibus Wald test. We reported significant results at the p < 0.05 level.

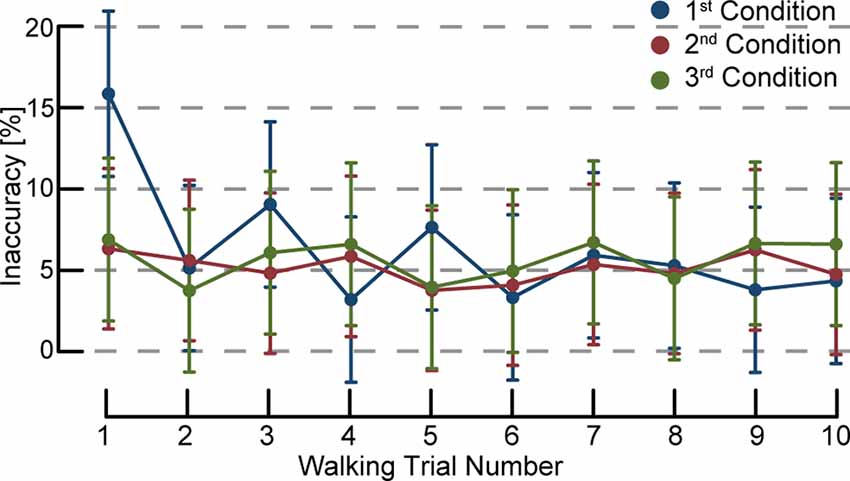

Participants adjusted their walking speed to meet the target walking speed during the MR-HMD walking conditions. As expected, inaccuracy in meeting the target gait speed decreased with additional repetitions using the MR-HMD. Specifically, we found a significant interaction between within-condition walking trial number (1–10) and the order in which the condition was tested (first, second, or third; χ2 = 39.3, p < 0.01). The first trial in any condition had a larger percent inaccuracy compared with nearly all subsequent walking trials, but only if the condition was the first tested condition overall. The exception was the third trial of the first tested condition which did not differ significantly from the first trial of the first test condition (difference: −6.8%, CI95: −15.1, 1.41). Figure 2 illustrates the percent inaccuracy across the 10 walking trials in the first, second, and third tested condition. trials. Overall, the within-trial inaccuracy was 10.5% higher (CI95: 7.4, 13.5) in first trial of the first speed condition compared to subsequent trials. We found no significant differences in walking speed inaccuracy between the 2nd and 10th trial of the first speed condition, or the 1st and 10th trial in the second and third tested condition. Due to the significantly higher percent inaccuracy in the first overall walking trial, we excluded the first trial with the MR-HMD of the 30 walking trials with the MR-HMD for the subsequent analyses. We included overall walking trial number 2 through 30 for a total of 29 total walking trials. In effect, the first overall walking trial became a “practice trial”, and for each participant we analyzed nine trials of their first tested condition, and 10 walking trials each of the second and third tested condition.

Figure 2. Walking speed inaccuracy percentage by trial number. The first condition using visual feedback is indicated in blue, the second tested condition in red, and third tested condition in green. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. The first overall trial regardless of speed condition had a larger percent inaccuracy compared with nearly all subsequent walking trials. The within-trial inaccuracy was 10.5% higher (CI95: 7.4, 13.5) in first trial of the first speed condition compared to subsequent trials. We found no significant differences in walking speed inaccuracy between the second and 10th trial of the first speed condition, or the 1st and 10th trial in the subsequent speed conditions. As the first trial overall appears to be an outlier due to a learning effect, we excluded that trial for the subsequent analyses.

Participants changed their overground walking speed, stride length, and stride time to adhere to the MR-HMD feedback conditions. Results of the one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test found that, overall, actual walking speeds of the participants did not differ from the expected speeds during the SS85 (median difference from baseline: −13.8%, z = 0.63, p = 0.53), SS100 (median difference from baseline 1.2%, z = 1.23, p = 0.21), and SS115 (median difference: 14.2%, z = 0.16, p = 0.88) conditions (Figure 3). Overall, the within trial inaccuracy was 5.3% (CI95: 4.3, 6.4) which was consistent across the experimental conditions (see Table 2). When using the MR-HMD, participants adjusted their stride length and stride time relatively equally when modulating gait speed. In the SS85 condition, stride length was shorter (−7.6%, CI95: −10.9, −4.3) and stride time was longer (7.5%, CI95: 4.2, 10.8) compared to the S100 condition indicating that individuals took shorter and slower steps to decrease walking speed. Applying the additive inverse of stride time, we found no difference in the magnitude of the percent change between the stride parameters (difference: 0.1%, CI95: −3.6, 3.4). Stride length was longer (7.9, CI95: 4.4, 11.4) and stride time was shorter (−5.0, CI95: −8.5, −1.5) during the SS115 condition as compared to the SS100 condition, indicating that individuals took longer and faster steps to increase walking speed. We found no significant difference in the magnitude of the change (difference: 2.8%, CI95: 0.86). However, stride length (−3.1%, CI95: −5.0, −1.2) and stride time (−3.5%, CI95: −5.3, −1.6) were both shorter when walking with feedback compared to walking without feedback at a self-selected speed.

Figure 3. Percent difference in walking speed: actual vs. target. A one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test found that actual walking speeds of the participants did not differ from the expected speeds during the SS85 (median difference from baseline: −13.8%, z = 0.63, p = 0.53), SS100 (median difference from 1.2%, z = 1.23, p = 0.23), and SS115 (median difference: 14.2%, z = 0.16, p = 0.88) conditions.

Variability of SS walking speed did not differ between overground walking with and without MR-HMD feedback (CoV difference: 1.44, CI95: −0.54, 3.42, p = 0.16; Figure 4A). However, we found more variability in stride length (CoV difference: 1.47, CI95: 0.16, 2.78, p = 0.03) and stride time (CoV difference: 1.00, CI95: 0.11, 1.88, p = 0.03) with MR-HMD feedback as compared to without MR-HMD feedback (Figures 4B,C). Our findings suggests that an individual’s walking speed was no more variable with MR-HMD feedback compared to HMD without feedback; however, individuals exhibited more variability in the parameters used to achieve the target speed. The variability of each gait parameter was consistent across speeds (Table 3). Our participants had no episodes of falls or tripping during the study and did not report any adverse symptoms during the walking trials.

Figure 4. Coefficient of variation in walking speed, stride length, and stride time with and without augmented feedback. (A) Comparison of the baseline SS with SS100 condition showed that variability of walking speed did not differ when walking overground with and without MR-HMD feedback (CoV difference: 1.44, CI95: −0.54, 3.42, p = 0.16). (B) There was more variability in stride length (CoV difference: 1.47, CI95: 0.16, 2.78, p = 0.03) and (C) stride time (CoV difference: 1.00, CI95: 0.10, 1.88, p = 0.03) with MR-HMD feedback suggesting that individuals adopted more variable control strategies to achieve the target speed.

This study examined the feasibility of using an MR-HMD platform to elicit goal-directed changes in overground walking. In particular, we assessed the utility of a commercially available MR-HMD technology, the Microsoft HoloLens, to promote real-time modulation of walking speed in a group of adults who are not living with disability. Participants matched overground walking speeds within approximately 5% of the MR-HMD visual feedback target speed conditions, equivalent to an average difference of 0.08 m/s. This difference is less than 0.1–0.2 m/s, a threshold considered to represent meaningful change in clinical populations (Bohannon and Glenney, 2014; Bohannon and Wang, 2019). The relatively low inaccuracy indicates that the MR-HMD is a viable tool to provoke real-time changes in overground walking behavior. We discuss these findings in the context of motor learning principles and clinical applications. Future research may extend our understanding of ways to incorporate MR platforms as adjuvants to gait rehabilitation.

Augmented feedback has been shown to improve the acquisition of motor skills during interactions with real and virtual objects (Schmidt and Wrisberg, 2004). The type and timing of augmented feedback can be varied to enhance motor learning. For example, feedback can be internally focused, e.g., specific joint kinematics, or externally focused on completion of the full task (Wulf and Dufek, 2009). The timing of feedback can also be varied, for example, provided concurrently (during task performance), or terminally (after task completion; Sigrist et al., 2013). Additionally, augmented feedback can be provided by visual, auditory, or haptic inputs or combination multisensory modalities. In this study, our participants appeared to successfully modulate their gait speed during a single-day session when provided concurrent visual feedback and an external focus by the MR-HMD. Our findings align with substantial evidence supporting an external focus to promote motor performance and learning (Wulf, 2013; Chua et al., 2021). Our results also align with previous research which reports the benefits of extrinsic visual cues on motor learning in healthy individuals (Todorov et al., 1997; Sigrist et al., 2013; Lewthwaite and Wulf, 2017) and persons with physical disability (Aung and Al-Jumaily, 2014). Additionally, our results align with prior studies that show continuous visual cues of a movement-related task enhances the immediate learning of that task (Winstein and Schmidt, 1990; Winstein et al., 1996; Todorov et al., 1997; Weeks and Kordus, 1998; van Vliet and Wulf, 2006).

However, excessive reliance on concurrent visual feedback to achieve these goals may not translate to long-term carryover (Schmidt and Wulf, 1997). High-frequency dosing of the MR feedback may impact the consolidation of other intrinsic feedback mechanisms important for modulating walking speed. For instance, reliance on visual cues may reduce reliance on vestibular and proprioceptive intrinsic signaling that also serve major roles in accurately and precisely regulating walking mechanics during speed adjustments. Additionally, whereas this study focused on visual feedback the synchronization between visual and other types of feedback may increase the sense of “presence” in virtual environments (Heeter, 1992; Slater, 2009; Borrego et al., 2016), enhance integration into the virtual word (Lenggenhager et al., 2007) and may further improve performance (Cameirão et al., 2012). Future research should consider the effects of more explicit goal-directed MR feedback that include visualizations that complement the person’s skill level, as well as kinesthetic information about the movement, and investigate longer-term impacts on MR-based training interventions.

Restoring the ability to walk remains a highly valued goal for humans with various neuromuscular pathologies such as stroke, cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury (SCI), and Parkinson’s disease and is a major focus of rehabilitation interventions. Even small boosts in walking that promote greater independence with standing, walking within the home, or negotiating spaces not accessible with walking aides often translate into significant gains in health and quality of life. Skilled training strategies that target walking improvement should promote motor learning and neuroplastic changes via salient and task-specific training and effective feedback. MR platforms have the potential to enhance clinical training focused on walking improvement via several mechanisms (Kleim and Jones, 2008; Levin et al., 2015).

First, MR platforms embed virtual objects within the real environment thereby reducing the patient’s dependency on the simulated physical environment or the boundaries of a research laboratory. This allows for training in any environment (e.g., home, clinic, or community) that has salience to the individual. Second, MR-based interventions can provide opportunities for task-specific training. Task-specificity can reflect both the actual environment and virtual obstacles, but also the strategies used by individuals to negotiate these environments. Our findings demonstrated that while using MR-HMD individuals changed their gait speed by adjusting parameters (stride length and stride time) in the same pattern that is observed in healthy individuals during overground walking (Murray et al., 1969, 1970). Additionally, we observed similar variability in gait speed when individuals were walking with active feedback from the MR-HMD compared to walking with the powered-off device. However, we did find additional variability in stride length and stride time which suggests that using the MR-HMD may induce some variability at the individual step level.

In addition to providing salient and task specific training, MR applications have the potential to promote motivation and training adherence, and options for gamification may increase enjoyment of motor learning tasks as has been observed in VR applications (Thornton et al., 2005; Sharar et al., 2007; Burke et al., 2009; Ibrahim et al., 2016; Dias et al., 2019). MR based interventions also have the potential to improve feedback mechanisms. The provision of extrinsic forms of visual feedback regarding a physical task may enhance the performance of that task (Tate and Milner, 2010) especially when intrinsic feedback may be less reliable or inaccessible due to injury or illness (e.g., loss of proprioception).

Our findings align with previous literature supporting augmented and virtual reality as viable methods to improve rehabilitation outcomes. The use of augmented reality as an adjuvant to traditional physical therapy has been shown to enhance both trunk balance (Maciaszek et al., 2014; Cho et al., 2015) and walking performance (Yang et al., 2008; Mirelman et al., 2009; Stanton et al., 2011; Pedreira da Fonseca et al., 2017) in persons with cortical stroke. Further, the use of virtual-based feedback during treadmill walking facilitates walking in older adults (Franz et al., 2014), persons with spinal cord injury (Yen et al., 2014), and Parkinson’s disease (Jellish et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022). These results emphasized the benefits of MR technology to enhance recovery of functional walking. The comparable effects suggest that virtual objects may be as effective as real objects at modifying stepping behaviors. Finally, a recently published clinical practice guidelines supports use of virtual reality interventions to improve locomotion for individuals with neurologic diagnoses (Hornby et al., 2020). However, many questions remain regarding dosing and timing of augmented reality experiences within the context of the traditional gait rehabilitation (Koroleva et al., 2021). This includes the management of the level of immersion (Bailenson et al., 2005; Crosbie et al., 2006) to optimize task performance while minimizing potential withdrawal effects resulting from the transition from virtual to the real world (Hughes et al., 2020).

There are several study limitations that preclude the generalization of our study findings. First, the MR-HMD hardware posed constraints on the field of view, hologram complexity, and display resolution. To accommodate the device’s limited field of view and processing power, we simplified the visual feedback experience for study participants. We programmed the holographic ball to travel along a linear 10 m path that remained at a fixed height parallel to the ground. However, functionally meaningful tasks require turns, inclines, and obstacles that require head rotations. Changes in head inertia due to the mass of the MR-HMD may result in deviations in walking task requiring head rotation, but we did not explicitly test this possibility. Differences in the variability of stride length and stride time during overground walking occurred between SS walking with the MR feedback as compared to without the feedback (HMD only), indicating that participants may have had difficulty in maintaining step-to-step kinematics during the prescribed walking speed. It should also be noted that our protocol was designed to examine immediate changes in gait speed and kinematics while individuals received feedback from the MR-HMD, but we did not examine changes to gait speed or kinematics after the device was removed or long-term adaptions to gait parameters. Future work is needed to examine the efficacy of MR feedback in individuals with and without gait impairments and may be able to leverage newer devices which could mitigate some of the limitations attributed to the technology in the 1st generation MR-HMD. The growing positive evidence of MR will inevitably lead to new challenges regarding the integration of these technologies into the traditional clinical setting (Cerritelli et al., 2021).

This study demonstrated the feasibility of a novel MR-HMD platform that provided real-time visual feedback to promote goal-directed changes in overground walking speed. Participants learned to adjust their walking speed based on a single session of visual feedback from a personalized MR environment. Further advances in MR-HMD technology will no doubt result in greater accessibility and broader applications in healthcare and home settings.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

EE led the analysis and manuscript writing. MD developed the mixed reality programs. WM contributed to the methods and figures. CT contributed to the methods and analysis. AT performed the experiments and contributed to the discussion. RT conceived the idea for the mixed reality programs and contributed to the introduction and discussion. All authors provided critical feedback to the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The National Institutes of Health NICHD (R01 HD081274) funded a portion of this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We sincerely thank the subjects who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge Emily Elandt, PT; Justin Montgomery, PT; and Lu Wan, PhD for their help with testing the experimental protocol and data collection.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2022.868074/full#supplementary-material.

Afilalo, J., Eisenberg, M. J., Morin, J. F., Bergman, H., Monette, J., Noiseux, N., et al. (2010). Gait speed as an incremental predictor of mortality and major morbidity in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 56, 1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.039

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automatic Control 19, 716–723. doi: 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

Artaud, F., Singh-Manoux, A., Dugravot, A., Tzourio, C., and Elbaz, A. (2015). Decline in fast gait speed as a predictor of disability in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 63, 1129–1136. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13442

Aung, Y. M., and Al-Jumaily, A. (2014). Augmented reality-based RehaBio system for shoulder rehabilitation. Int. J. Mechatronics Automation 4, 52–62. doi: 10.1504/IJMA.2014.059774

Bailenson, J. N., Swinth, K., Hoyt, C., Persky, S., Dimov, A., and Blascovich, J. (2005). The independent and interactive effects of embodied-agent appearance and behavior on self-report, cognitive and behavioral markers of copresence in immersive virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 14, 379–393. doi: 10.1162/105474605774785235

Bishop, G., and Fuchs, H. (1992). Research directions in virtual environments: report of an NSF Invitational Workshop, March 23–24, 1992, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Comput. Graph. 26, 153–177. doi: 10.1145/142413.142416

Bohannon, R. W., and Glenney, S. S. (2014). Minimal clinically important difference for change in comfortable gait speed of adults with pathology: a systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 20, 295–300. doi: 10.1111/jep.12158

Bohannon, R. W., and Wang, Y. C. (2019). Four-meter gait speed: normative values and reliability determined for adults participating in the NIH toolbox study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 100, 509–513. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.031

Borrego, A., Latorre, J., Llorens, R., Alcaniz, M., and Noe, E. (2016). Feasibility of a walking virtual reality system for rehabilitation: objective and subjective parameters. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 13:68. doi: 10.1186/s12984-016-0174-1

Bowden, M. G., Balasubramanian, C. K., Behrman, A. L., and Kautz, S. A. (2008). Validation of a speed-based classification system using quantitative measures of walking performance poststroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 22, 672–675. doi: 10.1177/1545968308318837

Burke, J. W., McNeill, M. D. J., Charles, D. K., Morrow, P. J., Crosbie, J. H., and McDonough, S. M. (2009). Optimising engagement for stroke rehabilitation using serious games. Vis. Comput. 25:1085. doi: 10.1007/s00371-009-0387-4

Cameirão, M. S., Badia, S. B., Duarte, E., Frisoli, A., and Verschure, P. F. (2012). The combined impact of virtual reality neurorehabilitation and its interfaces on upper extremity functional recovery in patients with chronic stroke. Stroke 43, 2720–2728. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.653196

Cerritelli, F., Chiera, M., Abbro, M., Megale, V., Esteves, J., Gallace, A., et al. (2021). The challenges and perspectives of the integration between virtual and augmented reality and manual therapies. Front. Neurol. 12:700211. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.700211

Cho, K. H., Kim, M. K., Lee, H. J., and Lee, W. H. (2015). Virtual reality training with cognitive load improves walking function in chronic stroke patients. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 236, 273–280. doi: 10.1620/tjem.236.273

Chua, L. K., Jimenez-Diaz, J., Lewthwaite, R., Kim, T., and Wulf, G. (2021). Superiority of external attentional focus for motor performance and learning: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 147, 618–645. doi: 10.1037/bul0000335

Coolen, B., Beek, P. J., Geerse, D. J., and Roerdink, M. (2020). Avoiding 3D obstacles in mixed reality: does it differ from negotiating real obstacles? Sensors (Basel) 20:1095. doi: 10.3390/s20041095

Crosbie, J. H., Lennon, S., McNeill, M. D. J., and McDonough, S. M. (2006). Virtual reality in the rehabilitation of the upper limb after stroke: the user’s perspective. CyberPsychol. Behav. 9, 137–141. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.137

Davis, C. S. (2002). Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements. New York: Springer.

Dias, P., Silva, R., Amorim, P., Lains, J., Roque, E., Pereira, I. S. F., et al. (2019). Using virtual reality to increase motivation in poststroke rehabilitation. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 39, 64–70. doi: 10.1109/MCG.2018.2875630

Dingwell, J. B., Cusumano, J. P., Cavanagh, P. R., and Sternad, D. (2001). Local dynamic stability versus kinematic variability of continuous overground and treadmill walking. J. Biomech. Eng. 123, 27–32. doi: 10.1115/1.1336798

Dodge, H. H., Mattek, N. C., Austin, D., Hayes, T. L., and Kaye, J. A. (2012). In-home walking speeds and variability trajectories associated with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 78, 1946–1952. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318259e1de

Franz, J. R., Maletis, M., and Kram, R. (2014). Real-time feedback enhances forward propulsion during walking in old adults. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 29, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.10.018

Geerse, D. J., Coolen, B., and Roerdink, M. (2020). Quantifying spatiotemporal gait parameters with hololens in healthy adults and people with Parkinson’s disease: test-retest reliability, concurrent validity and face validity. Sensors (Basel) 20:3216. doi: 10.3390/s20113216

Glaister, B. C., Bernatz, G. C., Klute, G. K., and Orendurff, M. S. (2007). Video task analysis of turning during activities of daily living. Gait Posture 25, 289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.04.003

Gomez-Jordana, L. I., Stafford, J., Peper, C. L. E., and Craig, C. M. (2018). Virtual footprints can improve walking performance in people with Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 9:681. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00681

Guinet, A. L., Bouyer, G., Otmane, S., and Desailly, E. (2021). Validity of hololens augmented reality head mounted display for measuring gait parameters in healthy adults and children with cerebral palsy. Sensors (Basel) 21:2697. doi: 10.3390/s21082697

Hausdorff, J. M., Rios, D. A., and Edelberg, H. K. (2001). Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 82, 1050–1056. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.24893

Hayes, H. B., Chvatal, S. A., French, M. A., Ting, L. H., and Trumbower, R. D. (2014). Neuromuscular constraints on muscle coordination during overground walking in persons with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury. Clin. Neurophysiol. 125, 2024–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.02.001

Heeter, C. (1992). Being there: the subjective experience of presence. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1, 262–271. doi: 10.1162/pres.1992.1.2.262

Hollman, J. H., Watkins, M. K., Imhoff, A. C., Braun, C. E., Akervik, K. A., and Ness, D. K. (2016). A comparison of variability in spatiotemporal gait parameters between treadmill and overground walking conditions. Gait Posture 43, 204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.09.024

Hornby, T. G., Reisman, D. S., Ward, I. G., Scheets, P. L., Miller, A., Haddad, D., et al. (2020). Clinical practice guideline to improve locomotor function following chronic stroke, incomplete spinal cord injury and brain injury. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 44, 49–100. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000303

Hubner, P., Clintworth, K., Liu, Q., Weinmann, M., and Wursthorn, S. (2020). Evaluation of hololens tracking and depth sensing for indoor mapping applications. Sensors (Basel) 20:1021. doi: 10.3390/s20041021

Hughes, C. L., Fidopiastis, C., Stanney, K. M., Bailey, P. S., and Ruiz, E. (2020). The psychometrics of cybersickness in augmented reality. Front. Virtual Real. 1:602954. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2020.602954

Ibrahim, M. S., Mattar, A. G., and Elhafez, S. M. (2016). Efficacy of virtual reality-based balance training versus the Biodex balance system training on the body balance of adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 28, 20–26. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.20

Janeh, O., and Steinicke, F. (2021). A review of the potential of virtual walking techniques for gait rehabilitation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15:717291. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.717291

Jellish, J., Abbas, J. J., Ingalls, T. M., Mahant, P., Samanta, J., Ospina, M. C., et al. (2015). A system for real-time feedback to improve gait and posture in Parkinson’s disease. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 19, 1809–1819. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2015.2472560

Kleim, J. A., and Jones, T. A. (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 51, S225–S239. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018)

Koroleva, E. S., Kazakov, S. D., Tolmachev, I. V., Loonen, A. J. M., Ivanova, S. A., and Alifirova, V. M. (2021). Clinical evaluation of different treatment strategies for motor recovery in poststroke rehabilitation during the first 90 days. J. Clin. Med. 10:3718. doi: 10.3390/jcm10163718

Kubben, P. L., and Sinlae, R. S. N. (2019). Feasibility of using a low-cost head-mounted augmented reality device in the operating room. Surg. Neurol. Int. 10:26. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_228_18

Lee, S. J., and Hidler, J. (2008). Biomechanics of overground vs. treadmill walking in healthy individuals. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 104, 747–755. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01380.2006

Lee, J., Kim, S., Kim, L., Kang, J., Lee, S., and Kwon, S. (2017). A study on virtual studio application using microsoft hololens. Int. J. Adv. Smart Convergence 6, 80–87. doi: 10.7236/IJASC.2017.6.4.12

Lenggenhager, B., Tadi, T., Metzinger, T., and Blanke, O. (2007). Video ergo sum: manipulating bodily self-consciousness. Science 317, 1096–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.1143439

Levin, M. F., Weiss, P. L., and Keshner, E. A. (2015). Emergence of virtual reality as a tool for upper limb rehabilitation: incorporation of motor control and motor learning principles. Phys. Ther. 95, 415–425. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130579

Lewthwaite, R., and Wulf, G. (2017). Optimizing motivation and attention for motor performance and learning. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 16, 38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.005

Lohse, K., Shirzad, N., Verster, A., Hodges, N., and Van der Loos, H. F. (2013). Video games and rehabilitation: using design principles to enhance engagement in physical therapy. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 37, 166–175. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000017

Maciaszek, J., Borawska, S., and Wojcikiewicz, J. (2014). Influence of posturographic platform biofeedback training on the dynamic balance of adult stroke patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 23, 1269–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.10.029

Middleton, A., Fritz, S. L., and Lusardi, M. (2015). Walking speed: the functional vital sign. J. Aging Phys. Act. 23, 314–322. doi: 10.1123/japa.2013-0236

Milgram, P., Takemura, H., Utsumi, A., and Kishino, F. (1995). “Augmented reality: a class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum,” in Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies, ed Hari Das (Bellingham, WA, USA: International Society for Optics and Photonics), 282–292.

Mirelman, A., Bonato, P., and Deutsch, J. E. (2009). Effects of training with a robot-virtual reality system compared with a robot alone on the gait of individuals after stroke. Stroke 40, 169–174. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516328

Murray, M. P., Kory, R. C., and Clarkson, B. H. (1969). Walking patterns in healthy old men. J. Gerontol. 24, 169–178. doi: 10.1093/geronj/24.2.169

Murray, M. P., Kory, R. C., and Sepic, S. B. (1970). Walking patterns of normal women. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 51, 637–650.

Ochoa, J., Sternad, D., and Hogan, N. (2017). Treadmill vs. overground walking: different response to physical interaction. J. Neurophysiol. 118, 2089–2102. doi: 10.1152/jn.00176.2017

O’Connell, K. (2016). Designing for Mixed Reality: Blending Data, AR and the Physical World. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

Orendurff, M. S., Schoen, J. A., Bernatz, G. C., Segal, A. D., and Klute, G. K. (2008). How humans walk: bout duration, steps per bout and rest duration. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 45, 1077–1089. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.11.0197

Pedreira da Fonseca, E., da Silva Ribeiro, N. M., and Pinto, E. B. (2017). Therapeutic effect of virtual reality on post-stroke patients: randomized clinical trial. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 26, 94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.08.035

Perry, J., and Burnfield, J. (2010). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated.

Perry, J., Garrett, M., Gronley, J. K., and Mulroy, S. J. (1995). Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke 26, 982–989. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.982

Schliessmann, D., Schuld, C., Schneiders, M., Derlien, S., Glockner, M., Gladow, T., et al. (2014). Feasibility of visual instrumented movement feedback therapy in individuals with motor incomplete spinal cord injury walking on a treadmill. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:416. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00416

Schmid, A., Duncan, P. W., Studenski, S., Lai, S. M., Richards, L., Perera, S., et al. (2007). Improvements in speed-based gait classifications are meaningful. Stroke 38, 2096–2100. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475921

Schmidt, R. A., and Wrisberg, C. A. (2004). Motor Learning and Performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Schmidt, R. A., and Wulf, G. (1997). Continuous concurrent feedback degrades skill learning: implications for training and simulation. Hum. Factors 39, 509–525. doi: 10.1518/001872097778667979

Sharar, S. R., Carrougher, G. J., Nakamura, D., Hoffman, H. G., Blough, D. K., and Patterson, D. R. (2007). Factors influencing the efficacy of virtual reality distraction analgesia during postburn physical therapy: preliminary results from 3 ongoing studies. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 88, S43–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.09.004

Sigrist, R., Rauter, G., Riener, R., and Wolf, P. (2013). Augmented visual, auditory, haptic and multimodal feedback in motor learning: a review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 20, 21–53. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0333-8

Slater, M. (2009). Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 3549–3557. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0138

Stanton, R., Ada, L., Dean, C. M., and Preston, E. (2011). Biofeedback improves activities of the lower limb after stroke: a systematic review. J. Physiother. 57, 145–155. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70035-2

Stevens, S. L., Fuller, D. K., and Morgan, D. W. (2013). Leg strength, preferred walking speed and daily step activity in adults with incomplete spinal cord injuries. Top Spinal Cord InJ. Rehabil. 19, 47–53. doi: 10.1310/sci1901-47

Talkowski, J. B., Brach, J. S., Studenski, S., and Newman, A. B. (2008). Impact of health perception, balance perception, fall history, balance performance and gait speed on walking activity in older adults. Phys. Ther. 88, 1474–1481. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080036

Tate, J. J., and Milner, C. E. (2010). Real-time kinematic, temporospatial and kinetic biofeedback during gait retraining in patients: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 90, 1123–1134. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080281

Thibaudier, Y., Tan, A. Q., Peters, D. M., and Trumbower, R. D. (2020). Differential deficits in spatial and temporal interlimb coordination during walking in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury. Gait Posture 75, 121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2019.10.023

Thornton, M., Marshall, S., McComas, J., Finestone, H., McCormick, A., and Sveistrup, H. (2005). Benefits of activity and virtual reality based balance exercise programmes for adults with traumatic brain injury: perceptions of participants and their caregivers. Brain Inj. 19, 989–1000. doi: 10.1080/02699050500109944

Todorov, E., Shadmehr, R., and Bizzi, E. (1997). Augmented feedback presented in a virtual environment accelerates learning of a difficult motor task. J. Mot. Behav. 29, 147–158. doi: 10.1080/00222899709600829

van Hedel, H. J., Tomatis, L., and Muller, R. (2006). Modulation of leg muscle activity and gait kinematics by walking speed and bodyweight unloading. Gait Posture 24, 35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.06.015

van Vliet, P. M., and Wulf, G. (2006). Extrinsic feedback for motor learning after stroke: what is the evidence? Disabil. Rehabil. 28, 831–840. doi: 10.1080/09638280500534937

Wang, Y., Gao, L., Yan, H., Jin, Z., Fang, J., Qi, L., et al. (2022). Efficacy of C-Mill gait training for improving walking adaptability in early and middle stages of Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 91, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.10.010

Weeks, D. L., and Kordus, R. N. (1998). Relative frequency of knowledge of performance and motor skill learning. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 69, 224–230. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1998.10607689

Winstein, C. J., Pohl, P. S., Cardinale, C., Green, A., Scholtz, L., and Waters, C. S. (1996). Learning a partial-weight-bearing skill: effectiveness of two forms of feedback. Phys. Ther. 76, 985–993. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.9.985

Winstein, C. J., and Schmidt, R. A. (1990). Reduced frequency of knowledge of results enhances motor skill learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 16, 677–691. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.16.4.677

Wulf, G. (2013). Attentional focus and motor learning: a review of 15 years. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 6, 77–104. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2012.723728

Wulf, G., and Dufek, J. S. (2009). Increased jump height with an external focus due to enhanced lower extremity joint kinetics. J. Mot. Behav. 41, 401–409. doi: 10.1080/00222890903228421

Yang, Y. R., Tsai, M. P., Chuang, T. Y., Sung, W. H., and Wang, R. Y. (2008). Virtual reality-based training improves community ambulation in individuals with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Gait Posture 28, 201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.11.007

Keywords: motor learning and control, walking, mixed reality, visual feedback, rehabilitation, kinematics

Citation: Evans E, Dass M, Muter WM, Tuthill C, Tan AQ and Trumbower RD (2022) A Wearable Mixed Reality Platform to Augment Overground Walking: A Feasibility Study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16:868074. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.868074

Received: 02 February 2022; Accepted: 03 May 2022;

Published: 09 June 2022.

Edited by:

Tara L. McIsaac, Creighton University Health Sciences Phoenix Campus, United StatesReviewed by:

Joon-Ho Shin, National Rehabilitation Center, South KoreaCopyright © 2022 Evans, Dass, Muter, Tuthill, Tan and Trumbower. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Randy D. Trumbower, cmFuZHkudHJ1bWJvd2VyQG1naC5oYXJ2YXJkLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.